How to Write a Thesis Statement on Effective Communication

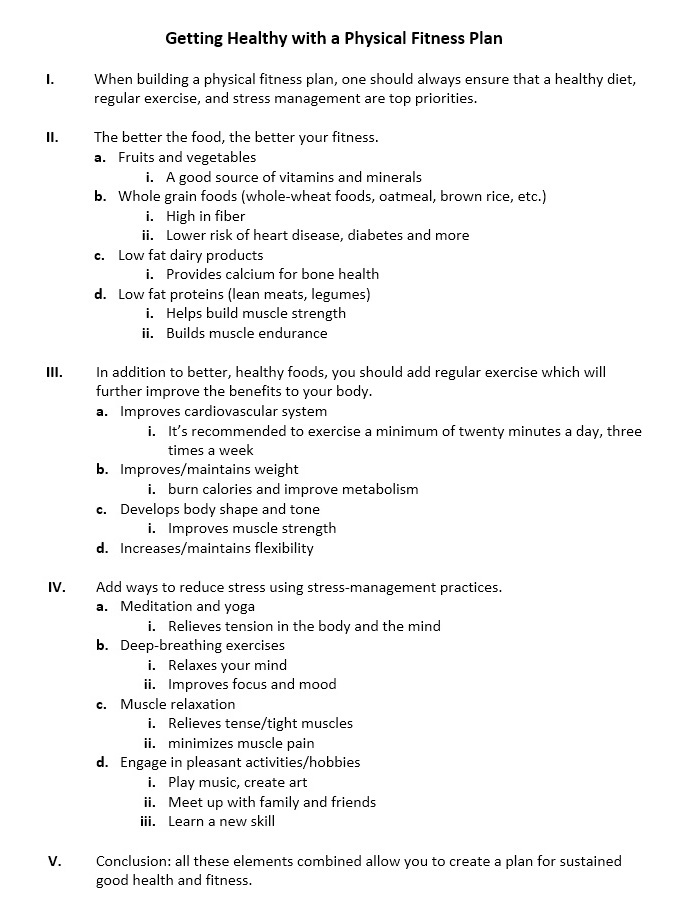

Writing a good thesis statement on effective communication involves communicating your motive in a statement of original and significant thought. The purpose you indicate in your thesis statement is the paper's main point – insight, argument or point of view – backed up by compelling research evidence. An effective communication thesis statement contains your proposed argument and support for your claim. It lets the reader know and understand the point of your paper in one or two sentences. Everything you write in your paper works toward building your thesis statement's strength. Remember that writing an effective communication thesis statement is different than writing one for most subjects; your educated readers will already know communication theory, application of techniques and personal experiences associated with effective communication.

Choose a topic for your thesis statement – if one is not assigned by your teacher – from a vast subject area with many diverse extended ideas. Examine how, what, when, where and whom in the process of gathering information for choosing the best topic. Narrow your focus if possible.

Explore a variety of research references on your topic that include journals, encyclopedias, books, newspapers and websites. Maintain notes that are detailed to help you conceptualize your thesis statement. Mark, underscore or highlight the most important data to back up your argument. Research acts as the basis for your specific, well-thought-out and defined thesis statement.

Decide whether the purpose of your composition is to inform or persuade. Formulate a thesis statement plan.

Review and analyze your notes to compose a thesis statement. An impressive thesis statement is made up of your argument proposal and claim support. Write down your thesis statement on a piece of paper. This allows you to see your thesis statement proposal in clear and logical terms.

Revise and adjust your thesis statement as you go along. Be sure it keeps the most fundamental and significant characteristics found in its original form. Pinpoint the two basics of your thesis: what your ideas relate to and what the angle of your ideas are. Make sure your thesis statement concentrates on these two basic points.

Establish individual insight in regard to your clear thesis statement. Your angle should reflect your own argument, ideas, analysis and interpretation of the effective communication topic.

Think about what might be argued against your thesis statement and refine your statement accordingly. Reflecting on possible counter-arguments allows you to consider differing opinions you will have to critique later in your essay.

- 1 Fastweb; Essay Tips: 7 Tips on Writing an Effective Essay; 2009

Related Articles

How to Write a Paper on Strengths & Weaknesses

What Is Theoretical Orientation in Research Articles?

How to Begin an Abstract

What Are the Differences Between Bias & Fallacy?

How to Write a Theme Paragraph

Communication Research Topic Ideas

How to Write a Report in High School

Key Ideas to Help Write an Argument & Persuasion Essay

Research Paper Thesis Topics

How to Write a Discursive Essay

Seven Key Features of Critical Thinking

How to Write a Textual Analysis

How to Write a Lens Essay

How to Write a Research Proposal for English Class

Tips on Writing a Subjective Paper

How to Transfer Outlook Notes to a Smartphone

How to Write a Debate Essay

How to Become a Good Debater

How to Know When You Are Exclusive & Monogamous in...

What Is Operational Framework in a Thesis?

Regardless of how old we are, we never stop learning. Classroom is the educational resource for people of all ages. Whether you’re studying times tables or applying to college, Classroom has the answers.

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Policy

- Manage Preferences

© 2020 Leaf Group Ltd. / Leaf Group Media, All Rights Reserved. Based on the Word Net lexical database for the English Language. See disclaimer .

Communication Thesis (14 Comprehensive Guide)

- 4 month(s) ago

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

Ii. choosing a relevant communication thesis topic, iii. formulating a strong thesis statement, iv. research methodologies in communication studies, v. literature review: building a solid foundation, vi. data collection and analysis, vii. interpreting findings, viii. writing the introduction and literature review, ix. methodology section: a step-by-step guide, x. results section: presenting your findings, xi. discussion: interpreting results in a theoretical context, xii. conclusion: summarizing your communication thesis, xiii. frequently asked questions (faqs), xiv. tips for a successful thesis defense, xv. resources for communication scholars, xvi. overcoming common challenges in thesis writing, xvii. celebrating your accomplishment.

A. Overview of Communication Thesis

In the realm of academic pursuits, a Communication Thesis serves as a comprehensive exploration and analysis of the multifaceted field of communication studies. This integral component of higher education is designed to delve into the intricate dynamics of human communication, covering diverse aspects such as interpersonal relationships, media influence, and organizational communication. The overview of a Communication Thesis involves navigating through the foundational theories that shape the discipline, understanding the evolving landscape of communication research, and recognizing the paramount importance of effective communication in various contexts.

This section of the thesis sets the stage for the reader by outlining the significance of the study, its relevance in contemporary society, and the overarching goals that the research aims to achieve. As scholars embark on this intellectual journey, they engage in a meticulous exploration that not only contributes to the existing body of knowledge but also cultivates a deeper understanding of the intricate tapestry of human interaction.

A. Identifying Personal Interest and Passion

Selecting a pertinent Communication Thesis topic is a pivotal step in the academic journey, and a crucial aspect of this process involves identifying personal interest and passion. This phase encourages students to delve into areas of communication studies that resonate with their intrinsic curiosity and enthusiasm. By aligning one’s research with personal interests, scholars not only ensure a more engaging and fulfilling research experience but also contribute to the authenticity and depth of their work.

Whether it’s exploring the impact of digital communication on interpersonal relationships or investigating the role of media in shaping public opinion, the connection between personal passion and the chosen thesis topic becomes a driving force behind the dedication and perseverance required for a successful academic endeavor. This alignment fosters a genuine commitment to the research process, elevating the overall quality and impact of the Communication Thesis.

B. Current Trends and Research Gaps in Communication

Choosing a relevant Communication Thesis topic involves not only personal interest but also a keen awareness of current trends and research gaps within the dynamic field of communication studies. Staying abreast of contemporary developments is essential for crafting a thesis that contributes meaningfully to the existing discourse. Scholars must identify the latest trends, be it the influence of social media on communication patterns or the evolving landscape of digital communication platforms.

Simultaneously, they should keenly observe research gaps—areas where the existing body of knowledge falls short or where new insights are needed. By addressing these gaps, a Communication Thesis not only becomes a scholarly contribution but also positions itself at the forefront of ongoing conversations in the field. This awareness ensures that the research is both timely and relevant, making a valuable impact on the broader understanding of communication dynamics.

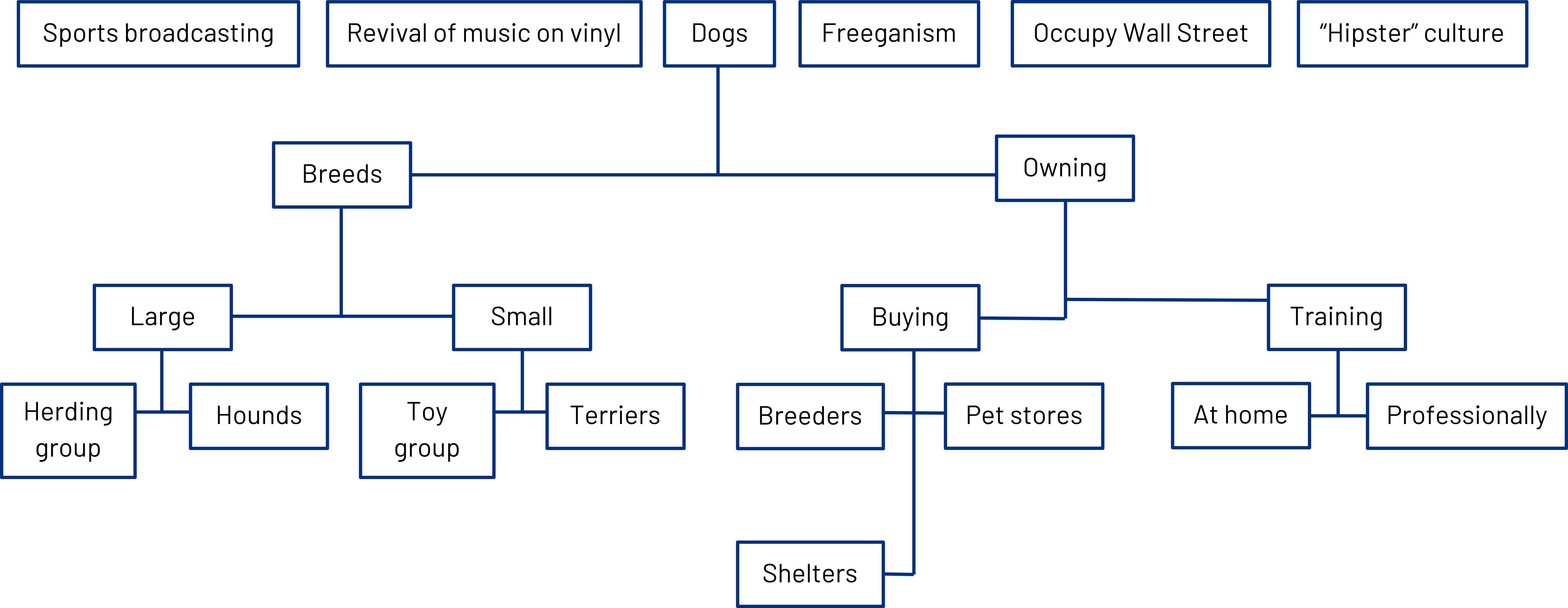

C. Tips for Narrowing Down Your Thesis Topic

Narrowing down a Communication Thesis topic is a nuanced process that requires careful consideration and strategic decision-making. To navigate this crucial step effectively, scholars can employ several tips to refine their focus. Firstly, it’s beneficial to conduct a preliminary literature review to identify existing research and potential gaps. Secondly, considering personal strengths and expertise can guide the selection process, ensuring a smoother and more confident research journey. Additionally, honing in on specific contexts, such as cultural or organizational communication, provides a clearer direction for exploration.

Collaborating with advisors and peers for feedback and insights is invaluable, offering diverse perspectives that can contribute to the topic refinement. Lastly, staying flexible and open to adjustments as the research progresses allows for adaptability and ensures the chosen topic remains relevant and aligned with the evolving landscape of communication studies. These tips collectively empower scholars to not only select a compelling Communication Thesis topic but also set the stage for a successful and impactful research endeavor.

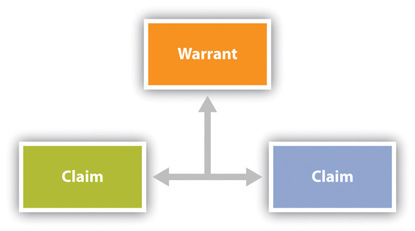

A. Crafting a Clear and Concise Thesis Statement

In formulating a strong Communication Thesis, crafting a clear and concise thesis statement is paramount. The thesis statement serves as the nucleus of the entire research, encapsulating the essence of the study in a succinct manner. It should communicate the main argument, the scope of the research, and its significance. Crafting clarity involves avoiding ambiguity and ensuring that the reader can readily grasp the central focus of the thesis.

A concise thesis statement is devoid of unnecessary details, presenting a streamlined preview of what the research endeavors to explore or prove. This precision not only aids the reader in understanding the purpose of the study but also provides a guiding beacon for the researcher throughout the entire thesis-writing process. As scholars embark on the journey of formulating their Communication Thesis, dedicating attention to the construction of a clear and concise thesis statement lays a solid foundation for a focused and impactful research endeavor.

B. Incorporating Research Questions

In formulating a robust Communication Thesis, the incorporation of well-defined research questions is a strategic element within the thesis statement. These questions serve as guiding beacons, providing a roadmap for the research endeavor. By explicitly stating the questions, the thesis gains clarity regarding the specific aspects of communication under investigation. These inquiries act as a framework, delineating the boundaries and objectives of the study.

The inclusion of research questions not only sharpens the focus of the thesis but also signals to the reader the precise areas the research aims to explore or answer. Crafting a strong thesis statement, enriched with relevant research questions, not only propels the research forward but also enhances the overall cohesion and coherence of the Communication Thesis. Scholars should ensure that these questions align seamlessly with the overarching objectives, reinforcing the purpose and significance of their academic inquiry.

C. Aligning Your Thesis with Academic Goals

In formulating a strong Communication Thesis statement, a crucial consideration is aligning the thesis with academic goals. This involves ensuring that the research objectives and the overarching theme of the thesis are in harmony with the broader academic context. By aligning the thesis with academic goals, scholars can demonstrate the relevance and contribution of their research to the field of communication studies.

Whether the aim is to address gaps in existing literature, challenge established theories, or offer practical insights, this alignment underscores the scholarly significance of the thesis. Moreover, it enables the researcher to contextualize their work within the larger academic discourse, enhancing its credibility and impact. Thus, a well-crafted thesis statement not only reflects the specific focus of the research but also positions it as a meaningful and purposeful contribution to the academic landscape. Read more

A. Qualitative Research Approaches

1. Case Studies

Utilizing case studies in qualitative research approaches is a powerful method within the realm of research methodologies for a Communication Thesis. Case studies offer an in-depth exploration of a specific phenomenon within its real-life context, allowing researchers to gain rich insights into complex communication dynamics. In the context of communication thesis research, case studies can delve into various aspects such as interpersonal communication challenges, media effects on certain populations, or organizational communication strategies.

By employing qualitative methods like case studies, scholars can capture the nuances of communication processes, behaviors, and outcomes, providing a holistic understanding that quantitative approaches may not fully capture. The detailed narratives derived from case studies not only contribute depth to the thesis but also offer valuable real-world applications, enhancing the overall robustness of the research.

2. Interviews and Focus Groups

In the realm of research methodologies for a Communication Thesis, qualitative research approaches often leverage interviews and focus groups as indispensable tools. Interviews provide a direct and personalized means of collecting data, allowing researchers to explore participants’ perspectives, experiences, and insights on specific communication phenomena. Focus groups, on the other hand, facilitate dynamic group discussions, offering a platform for participants to interact, share opinions, and generate collective insights.

Both methodologies contribute to the richness of qualitative research in communication studies, enabling scholars to capture the diversity of perspectives and nuances in interpersonal, organizational, or mediated communication. The interactive nature of interviews and focus groups allows for a deeper understanding of social dynamics, attitudes, and behavioral patterns, enhancing the comprehensiveness and depth of a Communication Thesis.

B. Quantitative Research Methods

Surveys play a pivotal role in quantitative research methods within the realm of research methodologies for a Communication Thesis. This method involves systematically gathering data from a large sample through standardized questionnaires, allowing researchers to quantify and analyze patterns, trends, and correlations in communication-related phenomena. Surveys are particularly valuable in exploring widespread attitudes, behaviors, and preferences within diverse populations, making them instrumental in communication studies.

By employing statistical analyses, scholars can derive quantitative insights, providing a quantitative foundation for understanding the prevalence and significance of specific communication trends or issues. Surveys offer a structured and efficient means of collecting data on a scale that is often challenging with qualitative approaches, contributing to the empirical rigor of a Communication Thesis. The careful design and execution of surveys ensure that researchers can draw meaningful conclusions and contribute valuable quantitative evidence to the broader field of communication studies.

2. Content Analysis

In the realm of quantitative research methods within the methodologies for a Communication Thesis, content analysis emerges as a potent tool for systematically examining and interpreting communication artifacts. This method involves the systematic coding and categorization of textual, visual, or audio content, allowing researchers to quantify and analyze patterns, themes, and trends within a vast array of communication materials.

Content analysis is particularly valuable in studying media messages, social media content, or textual representations, enabling scholars to uncover underlying patterns and draw statistical inferences. By applying objective coding schemes, researchers can measure the frequency and prominence of specific themes, sentiments, or communication strategies. Content analysis, as a quantitative research method, adds a layer of empirical rigor to communication studies, providing numerical insights that contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the communicative landscape addressed in a Communication Thesis.

A. Reviewing Key Studies in Communication

In the critical phase of crafting a Literature Review for a Communication Thesis, reviewing key studies in communication lays the groundwork for building a solid and informed foundation. This process involves a meticulous examination of seminal works, academic articles, and influential research findings within the field of communication studies. By delving into these key studies, scholars gain a comprehensive understanding of the historical evolution, theoretical frameworks, and methodological approaches that have shaped the discipline.

This review not only highlights the pivotal contributions of past scholars but also identifies gaps, contradictions, and areas for further exploration. By synthesizing and critically analyzing key studies, the Literature Review establishes the context for the current research, showcasing the continuity and evolution of knowledge within the field of communication. This comprehensive foundation not only validates the significance of the chosen thesis topic but also positions the research within the broader scholarly conversation, contributing to the academic discourse in communication studies.

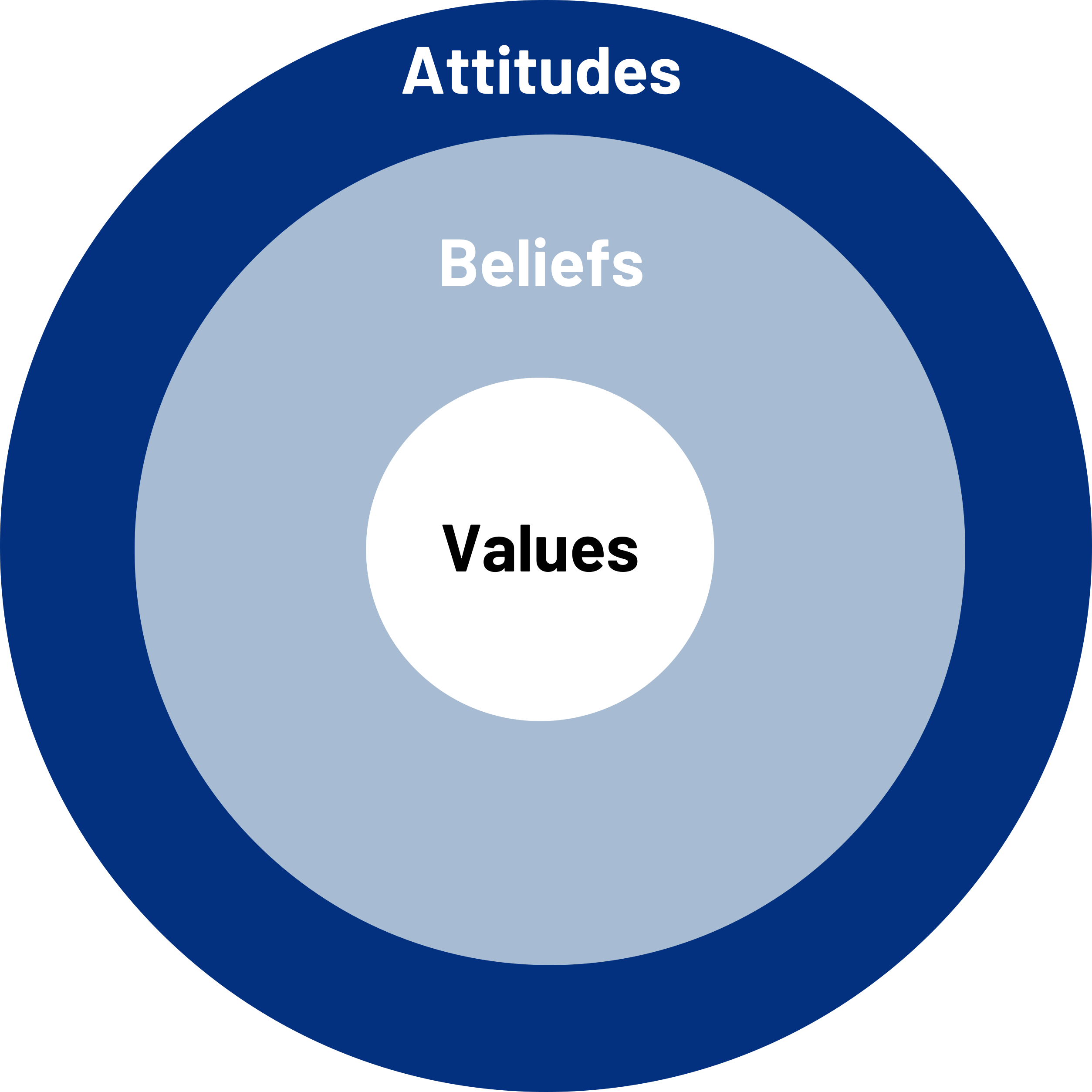

B. Identifying Theoretical Frameworks

In the foundational process of constructing a Literature Review for a Communication Thesis, identifying theoretical frameworks is paramount to establishing a solid intellectual foundation. This involves a meticulous exploration of the theoretical underpinnings that have shaped and defined the landscape of communication studies. By identifying and analyzing various theoretical frameworks—ranging from classic to contemporary—scholars gain insight into the diverse lenses through which communication phenomena are conceptualized.

The identification of theoretical frameworks not only provides a conceptual roadmap for understanding communication dynamics but also aids in situating the research within the broader theoretical landscape. This alignment helps scholars navigate the complexities of their chosen topic, offering a theoretical scaffold to frame research questions, guide methodological choices, and interpret findings. The integration of these theoretical perspectives enriches the Literature Review, contributing depth and theoretical coherence to the overall narrative of the Communication Thesis.

C. Analyzing Methodological Approaches

In the foundational process of constructing a Literature Review for a Communication Thesis, analyzing methodological approaches is instrumental in building a solid scholarly foundation. This phase involves a comprehensive examination of the various research methods employed in key studies within communication studies. By scrutinizing methodological approaches, scholars gain insights into the strengths, limitations, and nuances of different research methodologies such as surveys, interviews, content analysis, or experimental designs.

Understanding the methodological diversity within the field not only equips researchers with the tools to critically evaluate existing literature but also aids in shaping the research design for their own thesis. This analytical process contributes to the overall rigor of the Literature Review, allowing scholars to highlight the methodological trends, innovations, and gaps in the current body of communication research. Ultimately, a nuanced analysis of methodological approaches enhances the scholarly foundation, ensuring that the Communication Thesis is positioned at the forefront of methodological considerations within the field. For more information click here .

A. Gathering Primary and Secondary Data

In the crucial phase of Data Collection and Analysis for a Communication Thesis, gathering both primary and secondary data is a pivotal step toward constructing a comprehensive and well-informed research framework. Primary data, collected firsthand through methods like surveys, interviews, or observations, allows researchers to directly explore their research questions within the specific context of their study.

On the other hand, secondary data, comprising existing literature, articles, and other scholarly works, serves as a valuable foundation, providing context, insights, and comparative perspectives. The integration of both primary and secondary data enhances the depth and breadth of the research, fostering a more holistic understanding of the communication phenomena under investigation. This dual approach not only validates the research findings but also contributes to the richness and credibility of the overall analysis in the Communication Thesis. The careful synthesis of primary and secondary data ensures a well-rounded exploration, ultimately strengthening the scholarly contribution of the research to the field of communication studies.

B. Utilizing Software for Data Analysis

In the contemporary landscape of Communication Thesis research, the utilization of software for data analysis is a crucial element within the broader framework of Data Collection and Analysis. As datasets in communication studies grow in complexity and volume, employing specialized software tools becomes imperative for efficient and accurate analysis. Widely used statistical packages, such as SPSS or NVivo, facilitate the organization, coding, and interpretation of both quantitative and qualitative data.

These tools not only streamline the analytical process but also enable researchers to uncover patterns, trends, and correlations that may be challenging to discern manually. The integration of software for data analysis ensures rigor, precision, and reproducibility in the research findings, contributing to the overall credibility and validity of the Communication Thesis. As technology continues to evolve, leveraging advanced software tools becomes instrumental in extracting meaningful insights from the vast array of data encountered in communication research.

C. Ensuring Data Reliability and Validity

Ensuring data reliability and validity is paramount in the phase of Data Collection and Analysis within a Communication Thesis. Reliability speaks to the consistency and stability of the data, emphasizing the need for dependable and replicable results. Validity, on the other hand, underscores the accuracy and relevance of the data in measuring what it intends to measure. To guarantee data reliability, researchers employ consistent methods, minimize biases, and conduct pilot studies.

Validation, meanwhile, demands a thorough understanding of the chosen research instruments, be it surveys, interviews, or content analysis, to ensure they effectively capture the intended communication phenomena. Rigorous attention to data reliability and validity not only fortifies the robustness of the research findings but also bolsters the overall credibility and trustworthiness of the Communication Thesis. Researchers must be vigilant in addressing potential sources of error, implementing stringent quality control measures, and transparently reporting their methodology to enhance the reliability and validity of their data.

A. Connecting Data to Thesis Objectives

In the process of interpreting findings within a Communication Thesis, a critical step involves connecting the data to the overarching thesis objectives. This connection serves as the bridge that transforms raw data into meaningful insights, aligning the empirical evidence with the initial research goals. By systematically linking the obtained results to the predefined objectives, researchers can unravel the implications, patterns, and significance of their findings in the context of the broader communication landscape.

This step is crucial for deriving meaningful conclusions, making informed recommendations, and contributing substantively to the field. The alignment between data and thesis objectives not only ensures the coherence of the research but also provides a clear narrative that guides readers through the journey from data collection to the ultimate interpretation within the Communication Thesis.

B. Addressing Unexpected Results

In the intricate process of interpreting findings within a Communication Thesis, it is essential to address unexpected results with a thoughtful and analytical approach. Unforeseen outcomes can offer valuable insights into the complexity of communication phenomena. Researchers must resist the temptation to dismiss unexpected findings and instead delve into their potential causes. This may involve revisiting the research design, scrutinizing data collection methods, or considering alternative explanations.

The acknowledgment and exploration of unexpected results contribute to the intellectual honesty of the study, showcasing the researcher’s commitment to a thorough and unbiased investigation. Addressing unexpected outcomes in the interpretation phase not only refines the understanding of the communication dynamics under scrutiny but also strengthens the overall credibility and reliability of the Communication Thesis. It is through this nuanced exploration that researchers can uncover hidden patterns, refine their theories, and make significant contributions to the evolving field of communication studies.

C. Drawing Meaningful Conclusions

Drawing meaningful conclusions is the culmination of the intricate process of interpreting findings within a Communication Thesis. As researchers navigate through the wealth of data and analysis, synthesizing the results into insightful and coherent conclusions becomes paramount. This phase involves not only summarizing key findings but also extrapolating their broader implications for the field of communication studies. By connecting the dots between data, theoretical frameworks, and research objectives, scholars can distill overarching patterns, trends, or disparities.

Meaningful conclusions provide closure to the research narrative, offering a comprehensive understanding of the communication phenomena under investigation. It is through this synthesis that researchers contribute to the advancement of knowledge, offering fresh insights, suggesting avenues for future research, and ultimately enriching the academic discourse within the realm of communication studies through their thesis. For more details read here .

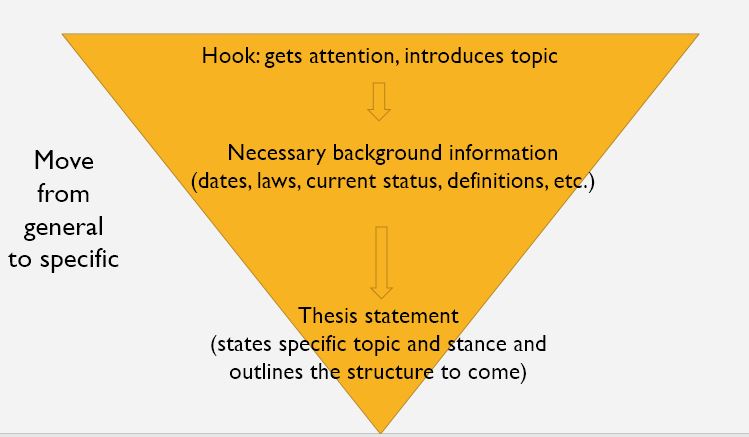

Crafting the introduction and literature review is a foundational aspect of developing a Communication Thesis. The introduction serves as the gateway to the research, providing a concise overview of the study’s purpose, significance, and objectives. It sets the stage for the reader, offering context for the communication phenomena under investigation and outlining the research’s broader implications.

Concurrently, the literature review delves into existing scholarly works, synthesizing key studies, theoretical frameworks, and methodological approaches within the field of communication studies. This section not only establishes the researcher’s familiarity with the existing body of knowledge but also identifies gaps and research questions that the current study seeks to address. By strategically combining the introduction and literature review, scholars construct a cohesive and compelling narrative, providing readers with a clear understanding of the research’s context, relevance, and the unique contributions it aims to make within the dynamic landscape of communication studies.

A. Detailing Research Design

In the Methodology section of a Communication Thesis, detailing the research design is a pivotal step, offering readers a step-by-step guide into the systematic framework guiding the study. This segment outlines the blueprint that shapes the entire research process, encompassing the overall structure, sampling techniques, and data collection methods. By meticulously detailing the research design, scholars elucidate the rationale behind their methodological choices, addressing questions of feasibility, relevance, and ethical considerations.

Whether employing qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-method approaches, this section provides a transparent roadmap for how the research questions will be addressed. A well-crafted methodology not only enhances the internal validity of the study but also equips readers with the insights needed to assess the rigor and reliability of the research findings. Through this methodical exposition, researchers ensure that their communication thesis stands on a robust and credible methodological foundation.

B. Describing Sampling Techniques

In the Methodology section of a Communication Thesis, describing sampling techniques is a crucial step that illuminates the systematic approach taken to select participants or sources for the study. Whether employing probability or non-probability sampling methods, this detailed exposition provides transparency into the researcher’s decisions, ensuring readers understand the rationale behind the chosen sampling strategy. The discussion typically includes considerations such as population characteristics, sample size, and the methods used to recruit or select participants.

A clear depiction of sampling techniques is essential not only for ensuring the representativeness of the study but also for allowing readers to assess the generalizability of the findings. Through this methodological guide, scholars navigate the intricacies of participant selection in communication studies, contributing to the overall reliability and validity of the research conducted within the framework of the communication thesis.

C. Explaining Data Collection Procedures

In the Methodology section of a Communication Thesis, explaining data collection procedures serves as a vital component, providing a comprehensive and transparent guide for readers. This segment delineates the systematic steps taken to gather the necessary information for the study. Whether employing surveys, interviews, content analysis, or other data collection methods, researchers elucidate the intricacies of their approach, detailing protocols, instruments used, and ethical considerations.

This step-by-step guide ensures that the research process is reproducible, enhancing the study’s credibility. By transparently describing data collection procedures, scholars not only empower readers to evaluate the validity and reliability of the study but also contribute to the broader methodological discourse within communication studies. This methodological clarity is pivotal for fellow researchers, academics, and practitioners seeking to understand, replicate, or build upon the insights derived from the communication thesis.

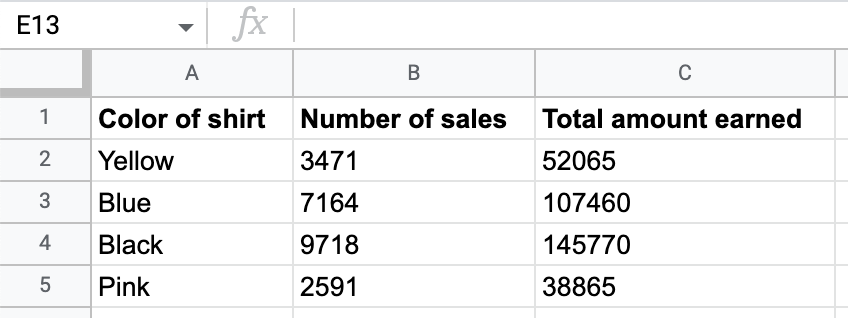

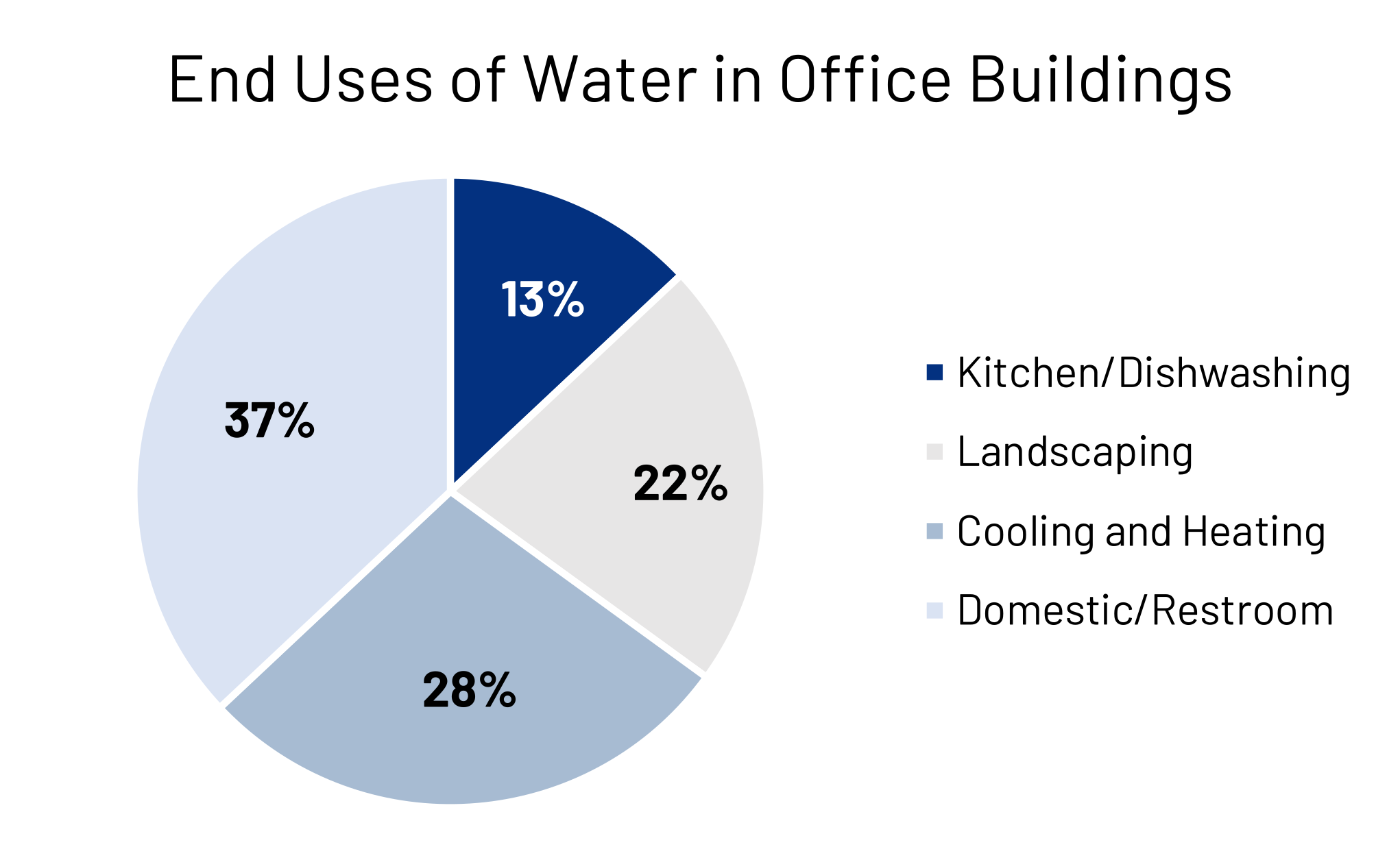

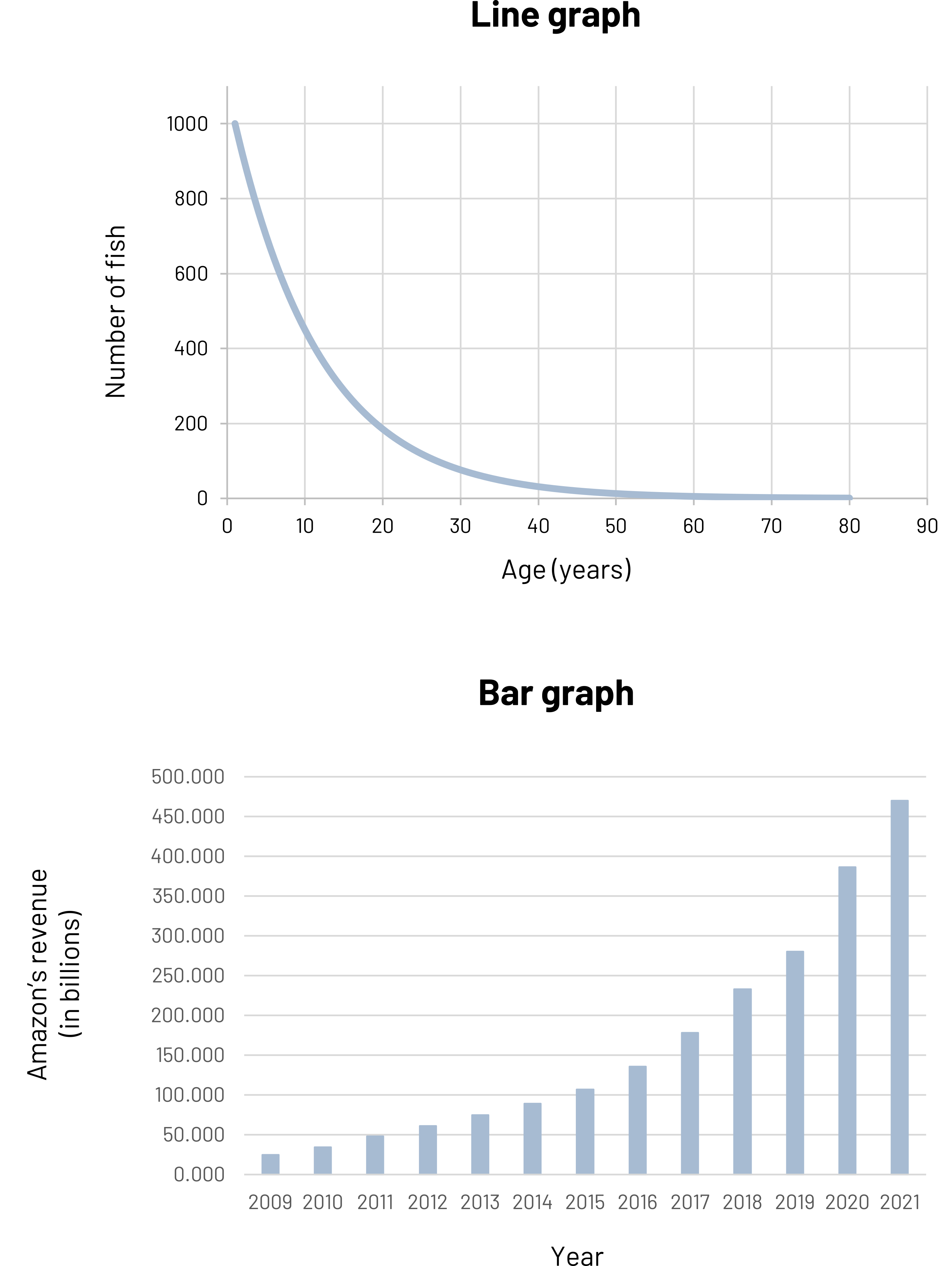

A. Visual Representation of Data

In the Results Section of a Communication Thesis, the visual representation of data is a powerful and integral component for presenting findings in a clear and accessible manner. Visual elements such as charts, graphs, and tables serve as visual aids that succinctly convey complex information, making it more comprehensible for the reader. Through visual representation, researchers can effectively illustrate patterns, trends, and relationships identified in the data, enhancing the overall impact and interpretability of their findings.

Well-crafted visuals not only facilitate a more engaging presentation but also enable readers to quickly grasp key insights, fostering a deeper understanding of the communication dynamics under investigation. This strategic use of visual representation in the Results Section contributes to the overall effectiveness of the Communication Thesis by offering a visually compelling narrative that complements the textual presentation of research outcomes.

B. Comparative Analysis

In the Results Section of a Communication Thesis, a comparative analysis is a crucial method for presenting findings and extracting meaningful insights. This approach involves systematically comparing different sets of data, variables, or groups to discern patterns, differences, or similarities. Through comparative analysis, researchers can provide a nuanced understanding of how various factors may influence communication phenomena.

Whether contrasting different communication strategies, audience responses, or media effects, this method offers a structured means of highlighting key distinctions and drawing connections within the data. The careful application of comparative analysis not only contributes to the depth of the presented findings but also supports the development of well-grounded interpretations. By employing this method in the Results Section, scholars enhance the overall clarity and richness of their communication thesis, enabling readers to discern the nuances inherent in the research outcomes.

C. Incorporating Tables and Figures

In the Results Section of a Communication Thesis, the strategic incorporation of tables and figures plays a pivotal role in presenting findings with clarity and precision. These visual elements serve as invaluable tools for organizing complex data, providing a concise and accessible representation of key results. Tables are effective for presenting numerical data, allowing for easy comparison and reference, while figures, such as charts or graphs, enhance the visualization of trends and relationships within the data.

By thoughtfully integrating tables and figures, researchers not only streamline the communication of intricate information but also offer readers an enhanced understanding of the patterns and insights derived from the study. This visual supplementation in the Results Section of the communication thesis facilitates a more engaging and comprehensible presentation of research outcomes, fostering a deeper appreciation of the empirical contributions made within the study.

A. Relating Findings to Literature

In the Discussion section of a Communication Thesis, relating findings to the existing literature is a critical step that places the empirical results within a broader theoretical context. This process involves examining how the research outcomes align with, challenge, or contribute to the theories and concepts discussed in the literature review. By establishing these connections, researchers provide a theoretical framework for interpreting their findings, offering insights into the implications of the study within the established body of knowledge.

This integration of empirical evidence and theoretical constructs not only validates the study’s relevance but also enhances the scholarly discourse within the field of communication studies. Through the artful synthesis of findings and literature, scholars pave the way for a more profound understanding of the communication phenomena under investigation, contributing to the ongoing evolution of theoretical perspectives within the communication thesis.

B. Addressing Limitations

Within the Discussion section of a Communication Thesis, addressing limitations is a crucial element of transparent and scholarly interpretation of results within a theoretical context. It involves a candid acknowledgment and exploration of the constraints, challenges, or potential biases inherent in the research design or execution. By openly discussing these limitations, researchers demonstrate a commitment to intellectual rigor and honesty, allowing readers to contextualize the findings appropriately.

Addressing limitations also provides an opportunity for scholars to suggest avenues for future research or propose refinements to existing methodologies. This reflective approach within the Discussion section not only underscores the researcher’s awareness of the study’s constraints but also enriches the scholarly dialogue within the field of communication studies, encouraging a more nuanced and self-aware interpretation of the empirical results presented in the thesis.

C. Proposing Future Research Avenues

In the Discussion section of a Communication Thesis, proposing future research avenues is a crucial step that extends the scholarly discourse beyond the current study. This forward-looking aspect involves identifying gaps in the existing literature, considering unexplored dimensions of the research topic, or suggesting novel methodologies for future investigations. By outlining these potential research directions, scholars not only contribute to the ongoing development of knowledge within the field of communication studies but also inspire and guide future researchers.

This proactive engagement with the future not only showcases the depth of the researcher’s understanding of the subject matter but also positions the study within a broader context of academic inquiry. Proposing future research avenues within the theoretical context of the Communication Thesis enhances the study’s impact and invites a continual and dynamic exploration of the complex and evolving landscape of communication phenomena. Read more

In the concluding section of a Communication Thesis, the task is to synthesize the key insights, contributions, and implications derived from the study. The conclusion serves as a succinct summary, providing closure to the research narrative while highlighting the significance of the findings within the broader context of communication studies. This section often revisits the research questions, emphasizing how they have been addressed through the empirical investigation.

Scholars use this opportunity to underscore the theoretical and practical implications of their work, reinforcing the importance of the study in advancing understanding within the field. The conclusion is not merely a recapitulation but a strategic encapsulation of the research journey, offering a final perspective that resonates with the overarching goals of the Communication Thesis and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

A. What makes a compelling communication thesis topic?

B. How do I choose the right research methodology for my thesis?

C. What are common challenges in data analysis for communication studies?

D. How can I ensure ethical considerations in my communication research?

E. Tips for effectively structuring the literature review in a thesis.

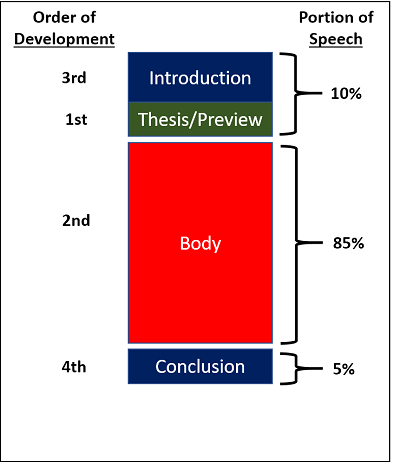

A. Preparing a Strong Presentation

Preparing a strong presentation is a crucial component of ensuring a successful thesis defense in the realm of Communication Studies. As scholars approach this pivotal moment, the ability to distill complex research into a clear, engaging, and well-organized presentation is paramount. Tips for a successful defense include a strategic structuring of the presentation to cover key components such as introduction, research objectives, methodology, results, and conclusion.

It’s essential to articulate the significance of the study within the broader field of communication and effectively communicate findings with clarity. Utilizing visual aids, such as slides or graphics, can enhance comprehension and engagement. Additionally, anticipating potential questions and preparing thoughtful responses demonstrates a deep understanding of the research. A successful presentation not only showcases the researcher’s expertise but also allows for a dynamic and confident defense, fostering a meaningful exchange between the scholar and the thesis committee.

B. Confidence and Professionalism in Defense

Confidence and professionalism are indispensable elements for a successful thesis defense in the field of Communication Studies. As researchers present their work to the thesis committee, exuding confidence in both the content and delivery of the presentation instills trust in the validity and rigor of the research. Maintaining professionalism involves engaging with committee members respectfully, being receptive to feedback, and navigating questions with poise.

Confidence is not just about delivering a well-prepared presentation but also about demonstrating a thorough understanding of the subject matter. Presenting oneself as a knowledgeable and composed scholar contributes significantly to the overall success of the defense, creating an atmosphere of credibility and assurance. Researchers who convey confidence and professionalism not only showcase their preparedness but also leave a lasting positive impression on the committee, elevating the overall quality of the Communication Thesis defense.

For communication scholars engaged in the development of a thesis, a diverse array of resources serves as indispensable aids throughout the research journey. Academic databases such as PubMed, JSTOR, and ProQuest offer access to a wealth of scholarly articles, journals, and publications relevant to various communication topics. Libraries, both physical and digital, provide access to an extensive collection of books and reference materials, enriching the theoretical foundations of the thesis.

Additionally, online forums and academic communities offer opportunities for networking, sharing insights, and seeking guidance from fellow scholars. Methodological guides and handbooks on research design, data analysis, and writing are invaluable resources to enhance the rigor and quality of the thesis. Utilizing citation management tools like EndNote or Zotero aids in organizing references efficiently. Overall, the availability of these resources empowers communication scholars to navigate the complexities of thesis development, fostering a robust and well-informed academic exploration.

Communication thesis writing, like any scholarly endeavor, comes with its share of challenges. One common hurdle is the potential for information overload, as the expansive nature of communication studies may lead to an overwhelming amount of literature to sift through. Additionally, maintaining a clear and focused research question amidst the complexity of the field can be challenging. Another common challenge lies in balancing theoretical frameworks with empirical findings, ensuring a cohesive narrative that bridges the theoretical and practical aspects of the research.

Time management is often a universal struggle, given the meticulous nature of research and the need for extensive literature review. Lastly, maintaining consistency in writing style, adhering to academic standards, and navigating the intricacies of proper citation can pose challenges. Overcoming these hurdles requires strategic planning, effective organization, and perhaps most importantly, seeking guidance from mentors and peers throughout the communication thesis writing process.

Celebrating the accomplishment of completing a communication thesis is a moment of well-deserved recognition and pride. This academic journey is a culmination of dedication, rigorous research, and intellectual growth. It signifies the mastery of complex communication theories, research methodologies, and the ability to contribute meaningfully to the academic discourse. Taking a moment to acknowledge the effort, resilience, and intellectual curiosity that went into the thesis writing process is crucial.

Whether through personal reflection, sharing achievements with mentors and peers, or even a small personal celebration, recognizing the accomplishment serves not only as a form of self-validation but also as a testament to the scholarly commitment and expertise developed throughout the research journey. It marks not only the end of a rigorous academic endeavor but also the beginning of a new chapter as a seasoned and accomplished communication scholar.

Place a Quick Order

We have qualified Experts in all fields

Latest Articles

Criminal Law Essays (6 Insightful Points) 1 days ago

Corporate Law Reports (7 Top Writing Tips) 2 days ago

Capital Market Assignments (8 Best Tips) 3 days ago

Ratio Analysis Reports (7 Best Hints) 4 days ago

Portfolio Management Summaries (9 Top Tips) 5 days ago

Legal Analysis Essays (8 Effective Tips) 6 days ago

Financial Accounting Dissertations (7 Top Tips) 6 days ago

Capital Budgeting Reports( 7 Great Hints) 7 days ago

Management Thesis (7 Top Writing Tips) 8 days ago

Research Methodology ( Student's Guide) 9 days ago

Radio Active Tutors is a freelance academic writing assistance company. We provide our assistance to the numerous clients looking for a professional writing service.

Need academic writing assistance ? Order Now

Thesis Statements

This guide offers essential tips on thesis statements, but it’s important to note that thesis statement content, structure, and placement can vary widely depending on the discipline, level, and genre. One good way to get a sense of how thesis statements might be constructed in your field is to read some related scholarly articles.

A thesis statement articulates a writer’s main argument, point, or message in a piece of writing. Strong thesis statements will tell your audience what your topic is and what your position on that topic is. Also, they will often provide an overview of key supporting arguments that you will explore throughout your paper. A well-written thesis statement demonstrates that you have explored the topic thoroughly and can defend your claims.

For short, undergraduate-level papers, a thesis statement will usually be one to three sentences in length, often occurring at the end of the first paragraph. Its main function is to tie all of your ideas and arguments together. As you continue to present your evidence and argue your stance, your thesis will connect throughout your essay like a puzzle.

e.g., Closing the border between Greece and Macedonia has led to unnecessary suffering among refugees by preventing humanitarian aid from getting to those camps that need it most 1. Resolving this human rights problem will ultimately require cooperative effort from local, regional, and international agencies 2.

Statement of topic and main argument

Further details about topic that give your reader a sense of how the paper will be structured

Building Effective Thesis Statements

A strong thesis statement should be clear, concise, focused, and supportable. Unless your essay is simply explanatory, it should also be debatable (i.e., if your position on a topic is one that almost nobody would dispute, it may not be the best choice for an argumentative paper).

The following steps will help you throughout the process of developing your thesis statement::

Read the assignment thoroughly. Make sure you are clear about the expectations.

Do preliminary, general research: collect and organize information about your topic.

Form a tentative thesis. The following questions may help you focus your research into a tentative thesis:

What’s new about this topic?

What important about this topic?

What’s interesting about this topic?

What have others missed in their discussions about this topic?

What about this topic is worth writing about?

Do additional research. Once you have narrowed your focus, you can perform targeted research to find evidence to support your thesis. As you research, your understanding of the topic will change. This is normal and even desirable.

Refine your thesis statement. After doing extensive research and evaluating many sources, rewrite your thesis so it expresses your angle or position on your topic more clearly.

Sample Thesis Statements

This guide offers essential tips on the thesis statements, but it's important to note that thesis statement content, structure, and placement can vary widely depending on the discipline, level, and genre. One good way to get a sense of how thesis statements might be constructed in your field is to read some related scholarly articles.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Crafting a Thesis Statement and Preview

Crafting a thesis statement.

A thesis statement is a short, declarative sentence that states the purpose, intent, or main idea of a speech. A strong, clear thesis statement is very valuable within an introduction because it lays out the basic goal of the entire speech. We strongly believe that it is worthwhile to invest some time in framing and writing a good thesis statement. You may even want to write your thesis statement before you even begin conducting research for your speech. While you may end up rewriting your thesis statement later, having a clear idea of your purpose, intent, or main idea before you start searching for research will help you focus on the most appropriate material. To help us understand thesis statements, we will first explore their basic functions and then discuss how to write a thesis statement.

Basic Functions of a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement helps your audience by letting them know, clearly and concisely, what you are going to talk about. A strong thesis statement will allow your reader to understand the central message of your speech. You will want to be as specific as possible. A thesis statement for informative speaking should be a declarative statement that is clear and concise; it will tell the audience what to expect in your speech. For persuasive speaking, a thesis statement should have a narrow focus and should be arguable, there must be an argument to explore within the speech. The exploration piece will come with research, but we will discuss that in the main points. For now, you will need to consider your specific purpose and how this relates directly to what you want to tell this audience. Remember, no matter if your general purpose is to inform or persuade, your thesis will be a declarative statement that reflects your purpose.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

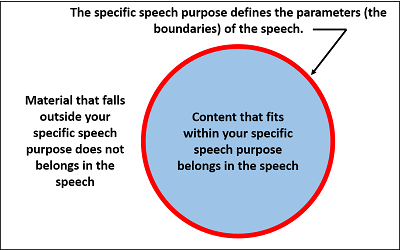

Now that we’ve looked at why a thesis statement is crucial in a speech, let’s switch gears and talk about how we go about writing a solid thesis statement. A thesis statement is related to the general and specific purposes of a speech.

Once you have chosen your topic and determined your purpose, you will need to make sure your topic is narrow. One of the hardest parts of writing a thesis statement is narrowing a speech from a broad topic to one that can be easily covered during a five- to seven-minute speech. While five to seven minutes may sound like a long time for new public speakers, the time flies by very quickly when you are speaking. You can easily run out of time if your topic is too broad. To ascertain if your topic is narrow enough for a specific time frame, ask yourself three questions.

Is your speech topic a broad overgeneralization of a topic?

Overgeneralization occurs when we classify everyone in a specific group as having a specific characteristic. For example, a speaker’s thesis statement that “all members of the National Council of La Raza are militant” is an overgeneralization of all members of the organization. Furthermore, a speaker would have to correctly demonstrate that all members of the organization are militant for the thesis statement to be proven, which is a very difficult task since the National Council of La Raza consists of millions of Hispanic Americans. A more appropriate thesis related to this topic could be, “Since the creation of the National Council of La Raza [NCLR] in 1968, the NCLR has become increasingly militant in addressing the causes of Hispanics in the United States.”

Is your speech’s topic one clear topic or multiple topics?

A strong thesis statement consists of only a single topic. The following is an example of a thesis statement that contains too many topics: “Medical marijuana, prostitution, and Women’s Equal Rights Amendment should all be legalized in the United States.” Not only are all three fairly broad, but you also have three completely unrelated topics thrown into a single thesis statement. Instead of a thesis statement that has multiple topics, limit yourself to only one topic. Here’s an example of a thesis statement examining only one topic: Ratifying the Women’s Equal Rights Amendment as equal citizens under the United States law would protect women by requiring state and federal law to engage in equitable freedoms among the sexes.

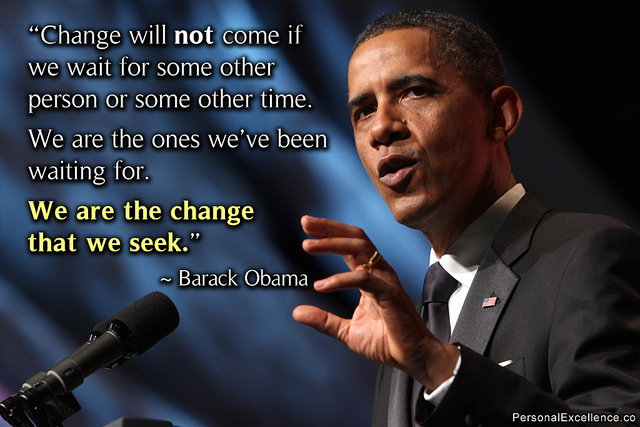

Does the topic have direction?

If your basic topic is too broad, you will never have a solid thesis statement or a coherent speech. For example, if you start off with the topic “Barack Obama is a role model for everyone,” what do you mean by this statement? Do you think President Obama is a role model because of his dedication to civic service? Do you think he’s a role model because he’s a good basketball player? Do you think he’s a good role model because he’s an excellent public speaker? When your topic is too broad, almost anything can become part of the topic. This ultimately leads to a lack of direction and coherence within the speech itself. To make a cleaner topic, a speaker needs to narrow her or his topic to one specific area. For example, you may want to examine why President Obama is a good public speaker.

Put Your Topic into a Declarative Sentence

You wrote your general and specific purpose. Use this information to guide your thesis statement. If you wrote a clear purpose, it will be easy to turn this into a declarative statement.

General purpose: To inform

Specific purpose: To inform my audience about the lyricism of former President Barack Obama’s presentation skills.

Your thesis statement needs to be a declarative statement. This means it needs to actually state something. If a speaker says, “I am going to talk to you about the effects of social media,” this tells you nothing about the speech content. Are the effects positive? Are they negative? Are they both? We don’t know. This sentence is an announcement, not a thesis statement. A declarative statement clearly states the message of your speech.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Or you could state, “Socal media has both positive and negative effects on users.”

Adding your Argument, Viewpoint, or Opinion

If your topic is informative, your job is to make sure that the thesis statement is nonargumentative and focuses on facts. For example, in the preceding thesis statement, we have a couple of opinion-oriented terms that should be avoided for informative speeches: “unique sense,” “well-developed,” and “power.” All three of these terms are laced with an individual’s opinion, which is fine for a persuasive speech but not for an informative speech. For informative speeches, the goal of a thesis statement is to explain what the speech will be informing the audience about, not attempting to add the speaker’s opinion about the speech’s topic. For an informative speech, you could rewrite the thesis statement to read, “Barack Obama’s use of lyricism in his speech, ‘A World That Stands as One,’ delivered July 2008 in Berlin demonstrates exceptional use of rhetorical strategies.

On the other hand, if your topic is persuasive, you want to make sure that your argument, viewpoint, or opinion is clearly indicated within the thesis statement. If you are going to argue that Barack Obama is a great speaker, then you should set up this argument within your thesis statement.

For example, you could turn the topic of President Obama’s public speaking skills into the following sentence: “Because of his unique sense of lyricism and his well-developed presentational skills, President Barack Obama is a modern symbol of the power of public speaking.” Once you have a clear topic sentence, you can start tweaking the thesis statement to help set up the purpose of your speech.

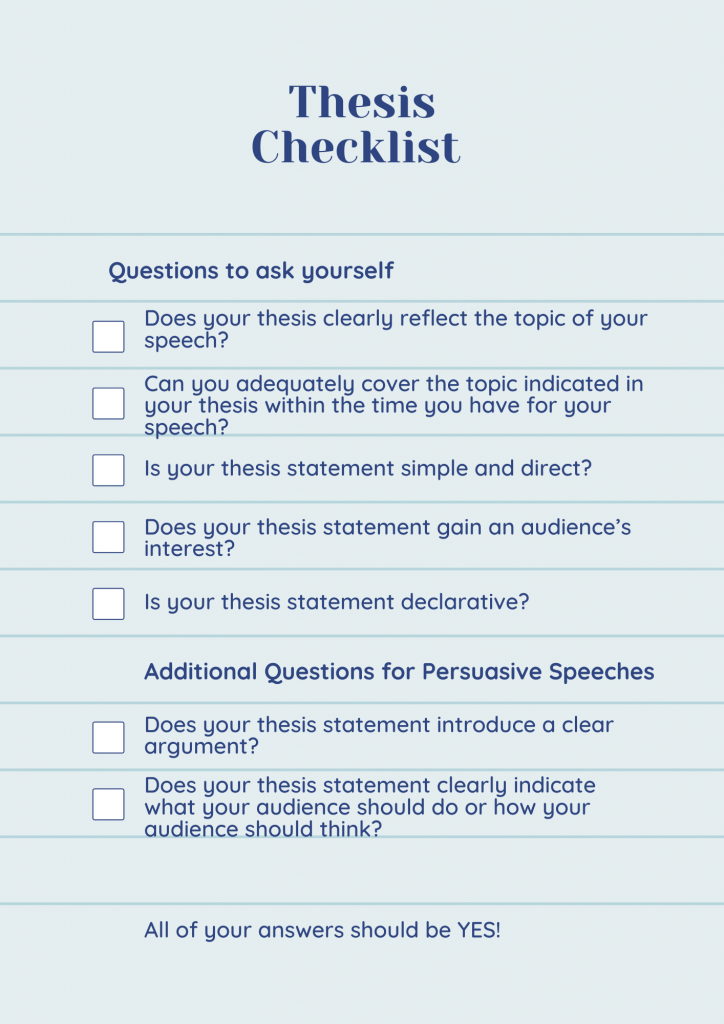

Thesis Checklist

Once you have written a first draft of your thesis statement, you’re probably going to end up revising your thesis statement a number of times prior to delivering your actual speech. A thesis statement is something that is constantly tweaked until the speech is given. As your speech develops, often your thesis will need to be rewritten to whatever direction the speech itself has taken. We often start with a speech going in one direction, and find out through our research that we should have gone in a different direction. When you think you finally have a thesis statement that is good to go for your speech, take a second and make sure it adheres to the criteria shown below.

Preview of Speech

The preview, as stated in the introduction portion of our readings, reminds us that we will need to let the audience know what the main points in our speech will be. You will want to follow the thesis with the preview of your speech. Your preview will allow the audience to follow your main points in a sequential manner. Spoiler alert: The preview when stated out loud will remind you of main point 1, main point 2, and main point 3 (etc. if you have more or less main points). It is a built in memory card!

For Future Reference | How to organize this in an outline |

Introduction

Attention Getter: Credibility: Thesis: Preview:

Key Takeaways

Introductions are foundational to an effective public speech.

- A thesis statement is instrumental to a speech that is well-developed and supported.

- Be sure that you are spending enough time brainstorming strong attention getters and considering your audience’s goal(s) for the introduction.

- A strong thesis will allow you to follow a roadmap throughout the rest of your speech: it is worth spending the extra time to ensure you have a strong thesis statement

Communication Competence: Developing Skills for Your Personal and Professional Life Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Communication Studies

The #1 resource for the communication field, how to write a thesis statement.

Academic writing can be intimidating, especially for an individual who is new to this type of composition. One important aspect of many academic papers is a solid thesis statement.

What is a Thesis Statement?

A thesis statement consists of one or two sentences that provide the reader with a brief summary of the direction of the paper. Rather than simply stating the topic, a thesis statement should indicate what argument is being made about that topic. A thesis is intended to answer a question, so a good thesis statement should briefly explain the basic premise of the argument.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement

When it is time to write a thesis statement, the author should already be deeply familiar with the material and the question being answered. One of the first steps in creating a thesis statement is isolating the primary question being answered by the paper. The rest of the thesis statement should be a concise answer to that question.

It is important to be specific because a vague answer does not give the reader a reasonable idea of what to expect. Additionally, the argument presented should be a claim that readers or experts could reasonably dispute. A statement that cannot be proven false is not a good thesis. Finally, the thesis statement and the paper should be fully connected. A paper that strays greatly or frequently from the thesis will lose readers.

Qualities of a Good Thesis Statement

- The thesis should answer the question

- It should be specific and avoid cramming too many ideas into one or two sentences. Vague statements should also be avoided

- The thesis statement should describe a disputable argument. If the statement cannot be proven false, it is not a good thesis statement

- A good thesis statement should use reader-friendly and accessible language. The potential audience should be considered

Example Thesis Statements

Male participants outperform females in spatial navigation tasks. This relatively short statement answers a question of male versus female performance on a particular task. The statement is a specific answer to that question. A fellow researcher could easily attempt to dispute those findings.

The downward shift in the economy promotes the election of polarizing political extremists. This statement should precede a paper that discusses how a troubled economy could contribute to the election of extreme politicians. Readers and researchers can dispute such a claim.

The convenience and accessibility of social media marketing makes traditional advertisement methods obsolete. This specific and disputable statement narrows the focus to how more modern technologies are making older methods of advertisement outdated.

Practice will eventually make generating thesis statements an automatic step in the writing process. By following the appropriate steps and examining the aspects of a good thesis statement, this step of academic writing can be mastered.

Thank you for this information.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Copyright Communicationstudies.com 2022

Communication Studies

What this handout is about.

This handout describes some steps for planning and writing papers in communication studies courses.

Courses in communication studies combine material from the humanities, fine arts, and social sciences in order to explain how and why people interact in the ways that they do. Within communication studies, there are four different approaches to understanding these interactions. Your course probably falls into one of these four areas of emphasis:

- Interpersonal and organizational communication: Interpersonal communication concerns one-on-one conversations as well as small group behaviors. Organizational communication focuses on large group dynamics.

- Rhetoric: Rhetoric examines persuasion and argumentation in political settings and within social movements.

- Performance studies: Performance studies analyze the relationships among literature, theater, and everyday life.

- Media/film studies: Media and film studies explore the cultural influences and practical techniques of television and film, as well as new technologies.

Understanding your assignment

The content and purpose of your assignments will vary according to what kind of course you are in, so pay close attention to the course description, syllabus, and assignment sheet when you begin to write. If you’d like to learn more about deciphering writing assignments or developing your academic writing, see our Writing Center handouts on these topics. For now, let’s see how a general topic, same-sex friendships, might be treated in each of the different areas. These illustrations are only examples, but you can use them as springboards to help you identify how your course might approach discussing a broad topic.

Interpersonal communication

An interpersonal communication perspective could focus on the verbal and nonverbal differences and similarities between how women communicate with other women and how men communicate with other men. This topic would allow you to explore the ways in which gender affects our behaviors in close relationships.

Organizational communication

Organizational communication would take a less personal approach, perhaps by addressing same-sex friendships in the form of workplace mentoring programs that pair employees of the same sex. This would require you to discuss and analyze group dynamics and effectiveness in the work environment.

A rhetorical analysis could involve comparing and contrasting references to friendship in the speeches of two well-known figures. For instance, you could compare Aristotle’s comments about Plato to Plato’s comments about Aristotle in order to discover more about the relationship between these two men and how each defined their friendship and/or same-sex friendship in general.

Performance studies

A performance approach might involve describing how a literary work uses dramatic conventions to portray same-sex friendships, as well as critiquing how believable those portrayals are. An analysis of the play Waiting for Godot could unpack the lifelong friendship between the two main characters by identifying what binds the men together, how these ties are effectively or ineffectively conveyed to the audience, and what the play teaches us about same-sex friendships in our own lives.

Media and film studies

Finally, a media and film studies analysis might explain the evolution of a same-sex friendship by examining a cinematic text. For example, you could trace the development of the main friendship in the movie Thelma and Louise to discover how certain events or gender stereotypes affect the relationship between the two female characters.

General writing tips

Writing papers in communication studies often requires you to do three tasks common to academic writing: analyze material, read and critique others’ analyses of material, and develop your own argument around that material. You will need to build an original argument (sometimes called a “theory” or “plausible explanation”) about how a communication phenomenon can be better understood. The word phenomenon can refer to a particular communication event, text, act, or conversation. To develop an argument for this kind of paper, you need to follow several steps and include several kinds of information in your paper. (For more information about developing an argument, see our handout on arguments ). First, you must demonstrate your knowledge of the phenomenon and what others have said about it. This usually involves synthesizing previous research or ideas. Second, you must develop your own original perspective, reading, or “take” on the phenomenon and give evidence to support your way of thinking about it. Your “take” on the topic will constitute your “argument,” “theory,” or “explanation.” You will need to write a thesis statement that encapsulates your argument and guides you and the reader to the main point of your paper. Third, you should critically analyze the arguments of others in order to show how your argument contributes to our general understanding of the phenomenon. In other words, you should identify the shortcomings of previous research or ideas and explain how your paper corrects some or all of those deficits. Assume that your audience for your paper includes your classmates as well as your instructor, unless otherwise indicated in the assignment.

Choosing a topic to write about

Your topic might be as specific as the effects of a single word in conversation (such as how the use of the word “well” creates tentativeness in dialogue) or as broad as how the notion of individuality affects our relationships in public and private spheres of human activity. In deciding the scope of your topic, look again at the purpose of the course and the aim of the assignment. Check with your instructor to gauge the appropriateness of your topic before you go too far in the writing process.

Try to choose a topic in which you have some interest or investment. Your writing for communications will not only be about the topic, but also about yourself—why you care about the topic, how it affects you, etc. It is common in the field of communication studies not only to consider why the topic intrigues you, but also to write about the experiences and/or cognitive processes you went through before choosing your topic. Including this kind of introspection helps readers understand your position and how that position affects both your selection of the topic and your analysis within the paper. You can make your argument more persuasive by knowing what is at stake, including both objective research and personal knowledge in what you write.

Using evidence to support your ideas

Your argument should be supported with evidence, which may include, but is not limited to, related studies or articles, films or television programs, interview materials, statistics, and critical analysis of your own making. Relevant studies or articles can be found in such journals as Journal of Communication , Quarterly Journal of Speech , Communication Education , and Communication Monographs . Databases, such as Infotrac and ERIC, may also be helpful for finding articles and books on your topic (connecting to these databases via NC Live requires a UNC IP address or UNC PID). As always, be careful when using Internet materials—check your sources to make sure they are reputable.

Refrain from using evidence, especially quotations, without explicitly and concretely explaining what the evidence shows in your own words. Jumping from quote to quote does not demonstrate your knowledge of the material or help the reader recognize the development of your thesis statement. A good paper will link the evidence to the overall argument by explaining how the two correspond to one another and how that relationship extends our understanding of the communication phenomenon. In other words, each example and quote should be explained, and each paragraph should relate to the topic.

As mentioned above, your evidence and analysis should not only support the thesis statement but should also develop it in ways that complement your paper’s argument. Do not just repeat the thesis statement after each section of your paper; instead, try to tell what that section adds to the argument and what is special about that section when the thesis statement is taken into consideration. You may also include a discussion of the paper’s limitations. Describing what cannot be known or discussed at this time—perhaps because of the limited scope of your project, lack of new research, etc.—keeps you honest and realistic about what you have accomplished and shows your awareness of the topic’s complexity.

Communication studies idiosyncrasies

- Using the first person (I/me) is welcomed in nearly all areas of communication studies. It is probably best to ask your professor to be sure, but do not be surprised if you are required to talk about yourself within the paper as a researcher, writer, and/or subject. Some assignments may require you to write from a personal perspective and expect you to use “I” to express your ideas.

- Always include a Works Cited (MLA) or References list (APA) unless you are told not to. Not giving appropriate credit to those whom you quote or whose ideas inform your argument is plagiarism. More and more communication studies courses are requiring bibliographies and in-text citations with each writing assignment. Ask your professor which citation format (MLA/APA) to use and see the corresponding handbook for citation rules.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1. Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

- An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

- An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text that does not fall under these three categories (e.g., a narrative), a thesis statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

The paper that follows should:

- Explain the analysis of the college admission process

- Explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

- Explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with peers

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

- Present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue community projects before entering college

Informative Speaking

The topic, purpose, and thesis.

Before any work can be done on crafting the body of your speech or presentation, you must first do some prep work—selecting a topic, formulating a purpose statement, and crafting a thesis statement. In doing so, you lay the foundation for your speech by making important decisions about what you will speak about and for what purpose you will speak. These decisions will influence and guide the entire speechwriting process, so it is wise to think carefully and critically during these beginning stages.

I think reading is important in any form. I think a person who’s trying to learn to like reading should start off reading about a topic they are interested in, or a person they are interested in. – Ice Cube

Questions for Selecting a Topic

- What important events are occurring locally, nationally and internationally?

- What do I care about most?

- Is there someone or something I can advocate for?

- What makes me angry/happy?

- What beliefs/attitudes do I want to share?

- Is there some information the audience needs to know?

Selecting a Topic

“The Reader” by Shakespearesmonkey. CC-BY-NC .

Generally, speakers focus on one or more interrelated topics—relatively broad concepts, ideas, or problems that are relevant for particular audiences. The most common way that speakers discover topics is by simply observing what is happening around them—at their school, in their local government, or around the world. This is because all speeches are brought into existence as a result of circumstances, the multiplicity of activities going on at any one given moment in a particular place. For instance, presidential candidates craft short policy speeches that can be employed during debates, interviews, or town hall meetings during campaign seasons. When one of the candidates realizes he or she will not be successful, the particular circumstances change and the person must craft different kinds of speeches—a concession speech, for example. In other words, their campaign for presidency, and its many related events, necessitates the creation of various speeches. Rhetorical theorist Lloyd Bitzer [1] describes this as the rhetorical situation. Put simply, the rhetorical situation is the combination of factors that make speeches and other discourse meaningful and a useful way to change the way something is. Student government leaders, for example, speak or write to other students when their campus is facing tuition or fee increases, or when students have achieved something spectacular, like lobbying campus administrators for lower student fees and succeeding. In either case, it is the situation that makes their speeches appropriate and useful for their audience of students and university employees. More importantly, they speak when there is an opportunity to change a university policy or to alter the way students think or behave in relation to a particular event on campus.

But you need not run for president or student government in order to give a meaningful speech. On the contrary, opportunities abound for those interested in engaging speech as a tool for change. Perhaps the simplest way to find a topic is to ask yourself a few questions. See the textbox entitled “Questions for Selecting a Topic” for a few questions that will help you choose a topic.

There are other questions you might ask yourself, too, but these should lead you to at least a few topical choices. The most important work that these questions do is to locate topics within your pre-existing sphere of knowledge and interest. David Zarefsky [2] also identifies brainstorming as a way to develop speech topics, a strategy that can be helpful if the questions listed in the textbox did not yield an appropriate or interesting topic.

Starting with a topic you are already interested in will likely make writing and presenting your speech a more enjoyable and meaningful experience. It means that your entire speechwriting process will focus on something you find important and that you can present this information to people who stand to benefit from your speech.