52 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best electoral college topic ideas & essay examples, 📃 good research topics about electoral college, ⭐ interesting topics to write about electoral college.

- The Electoral College in the United States Political analysts believe that the existence of the Electoral College has led to the development of the United States as a nation.

- Editorial on Electoral College Improvement As such, it is common to find cases where the person who is defeated by the majority votes wins the election because they have the right number of the Electoral College. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- US Constitution Changes Regarding Electoral College The first lens is the political lens, which is the understanding of the power relationship between those who possess the power and those who lack it.

- Electoral College and Congregational Reapportionment In the US, for instance, the electoral votes in each state are not distributed based on the popular votes cast to each candidate but the winner is taken to be the one with the popular […]

- Electoral College’s Advantages and Disadvantages Made up of 538 electors, the Electoral College votes decide the president and vice president of the United States of America.

- Electoral College: Prognosis for 2016 Clinton seems to be unlikely to win the 2016 elections, as the effects of the Democratic Party’s rule have been beyond deplorable in Obama’s office years.

- Electoral College Versus Direct Election Due to the problems the Electoral College system created during the 2000 presidential elections, people are clamoring to abolish or reform the said system.

- History of Electoral College According to this principle, the candidate who wins the majority of votes in a state takes the rest of the votes as well.

- Problems Facing the Electoral College in Presidential Elections The Electoral College is an electoral system in the United States that was established through the Constitution of the United States; this was subsequently amended through the establishment of the 12th Amendment of the year […]

- Abolishing the Electoral College: A Pathway to Democracy

- The Electoral College and Its Relation to the 2000 Presidential Election

- Alexander Hamilton’s Electoral College and the Modern Election

- Abolishing the Electoral College: Pros and Cons

- The Electoral College and Proposed Reform Policies

- The Necessity of Reforming the Electoral College for America

- The Strengths and Weakness of the Electoral College

- The Electoral College and the American Idea of Democracy

- Applying the Electoral College to the U.S. And Elsewhere

- Checks and Balances: Federalism and Electoral College

- Civics: The Electoral College and Primaries

- The Electoral College and the Influence of California

- Constitutional Amendment and Abolish the Electoral College

- Doubts and Concerns Floats on the Accuracy of Electoral College

- Electoral College and Why It Should Be Changed

- The Electoral College and the Problems That Come With It

- Federalism and the Electoral College: General Ticket Method for Selecting Presidential Electors

- The Electoral College Should Not Be Abolished

- The Electoral College and Voter Participation: Evidence on Two Hypotheses

- Many Argue the Flaws in the Electoral College of the United States

- Electoral College System and the Alleged Advantages

- Modern Election Arguments Against the Electoral College

- Electoral College Voting System for Choosing the President

- Nominations, Elections, and Campaigns: The Idea of Electoral College

- The Electoral College Issues From a Political Correctness Perspective

- Electoral Versus Popular Vote: Criticisms of the Electoral College

- Outdated Political System: Get Rid of the Electoral College

- The Electoral College: Dilemma of the United States

- POS Structure and Function of the Electoral College

- Predicting Electoral College Victory Probabilities From State Probability Data

- Sophisticated and Myopic? Citizen Preferences for Electoral College Reform

- The Electoral College and Its Impact on Voter Turnout

- Suffrage for the People: The Electoral College and Possible Alternatives

- The Electoral College: How It Has Shaped the Modern Presidential Election

- Swing States, the Winner-Take-All Electoral College, and Fiscal Federalism

- Advantages and Problems With the Electoral College System in America

- The American Voting System: Overview of Electoral College

- The Conflicts Concerning the Electoral College in America

- The Controversies Surrounding the Electoral College

- The Electoral College: Diversification and the Election Process

- The Corruption, Revolt, and Criticism Surrounding the American Electoral College System

- The Electoral College and How Popular Vote Doesn’t Matter

- The Electoral College, Battleground States, and Rule-Utilitarian Voting

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 27). 52 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/electoral-college-essay-topics/

"52 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 27 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/electoral-college-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '52 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 27 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "52 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/electoral-college-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "52 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/electoral-college-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "52 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 27, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/electoral-college-essay-topics/.

- Alexander Hamilton Ideas

- Demographics Topics

- Media Bias Questions

- Fake News Research Ideas

- Bureaucracy Paper Topics

- Civil Rights Movement Questions

- Freedom Topics

- Corruption Ideas

- Freedom of Speech Ideas

- Human Rights Essay Ideas

- Political Science Research Topics

- Social Democracy Essay Titles

- Political Parties Research Ideas

- Tea Party Ideas

- Women’s Rights Titles

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

102 Electoral College Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

The Electoral College is a unique system in the United States that determines the outcome of presidential elections. While some argue that it is an outdated and undemocratic method of electing a president, others believe it is a crucial part of our political system. If you're looking for essay topics on the Electoral College, look no further. Here are 102 ideas to get you started:

- The history of the Electoral College

- The purpose of the Electoral College

- The pros and cons of the Electoral College

- How does the Electoral College work?

- The impact of the Electoral College on presidential elections

- Should the Electoral College be abolished?

- How does the Electoral College affect third-party candidates?

- The role of swing states in the Electoral College

- The Electoral College and minority representation

- The Electoral College and voter turnout

- The impact of gerrymandering on the Electoral College

- The Electoral College and the two-party system

- The Electoral College and the popular vote

- The Electoral College and the Supreme Court

- The Electoral College and the 2000 presidential election

- The Electoral College and the 2016 presidential election

- The Electoral College and the 2020 presidential election

- The Electoral College and the Founding Fathers

- The Electoral College and the Constitution

- The Electoral College and the Civil War

- The Electoral College and the Voting Rights Act

- The Electoral College and the 12th Amendment

- The Electoral College and the 23rd Amendment

- The Electoral College and the 26th Amendment

- The Electoral College and the 27th Amendment

- The Electoral College and the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

- The Electoral College and state laws

- The Electoral College and faithless electors

- The Electoral College and the will of the people

- The Electoral College and the role of Congress

- The Electoral College and the role of the president

- The Electoral College and the role of the vice president

- The Electoral College and the role of the Supreme Court

- The Electoral College and the role of state legislatures

- The Electoral College and the role of political parties

- The Electoral College and the role of the media

- The Electoral College and the role of interest groups

- The Electoral College and the role of lobbyists

- The Electoral College and the role of corporations

- The Electoral College and the role of foreign governments

- The Electoral College and the role of social media

- The Electoral College and the role of technology

- The Electoral College and the role of data analytics

- The Electoral College and the role of polling

- The Electoral College and the role of campaign finance

- The Electoral College and the role of super PACs

- The Electoral College and the role of dark money

- The Electoral College and the role of PACs

- The Electoral College and the role of grassroots organizations

- The Electoral College and the role of political action committees

- The Electoral College and the role of think tanks

- The Electoral College and the role of advocacy groups

- The Electoral College

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Op-Ed: Ten questions, and answers, about the electoral college

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Every four years, we pick our president in an exceedingly odd way: through the electoral college. Below you’ll find 10 common questions about our system and its history, and the answers that best reflect modern scholarship rather than the myths that still dominate civics textbooks.

1. Was the electoral college designed to balance big and small states?

Not really. The Congress was indeed so designed, with the House favoring populous states and the Senate giving each state two votes regardless of population. But in the electoral college, big states have more sway, and they have since the beginning.

2. What about the idea that the framers distrusted direct democracy?

It’s overstated. The framers put the Constitution itself to a popular vote of sorts, provided for direct election of House members (thus breaking with the Articles of Confederation) and favored direct election of governors.

3. Were electors ever expected to make up their own minds?

From 1789 to today, most electors have been undistinguished no-names doing as they were told by whomever picked them. Early on, state legislatures did much of the picking, but soon, popular elections prevailed in most states.

4. Doesn’t the electoral college vindicate American federalism, treating each state seriously?

Yes, but so would a direct national election. Currently, states have little incentive to encourage voting. A state gets the same number of electoral votes no matter what. But in a direct national election system, any state encouraging broad voter participation would have more clout in the final result. States might compete and experiment with different ways to promote voter participation — federalism at its best.

5. Besides federalism, what is the best explanation for why we have an electoral college?

Slavery. In a direct-election system, the South would have lost every time because a huge proportion of its population — slaves — could not vote. The electoral college enabled each slave state to count its slaves (albeit at a discount, under the Constitution’s three-fifths clause) in the electoral college apportionment. The big winner early on was Virginia — a large state with lots of slaves. Indeed, eight of the first nine presidential elections were won by Virginians. Pennsylvania in 1800 had more free persons, but Virginia got more electoral votes that year. Thomas Jefferson would have lost the race against John Adams in 1800 but for the fact that the Southern states that backed Jefferson, a Southerner, got a dozen extra electoral votes because of their enslaved population. After 1800, the South refused to make any change that might weaken its inside track.

6. Now that slavery is abolished, why should we keep the system?

Maybe we shouldn’t. We pick governors in every state by direct election — one person, one vote. If this system works well for governors, it should work for presidents. Almost all modern-day defenses of the electoral college — avoiding recounts, boosting rural areas, etc. — are make-weight. If these arguments are sound, then every state is dumb in its gubernatorial election system. And states, in general, are not dumb. Nor are the other major democracies across the planet, none of which has an electoral college.

7. Can states agree among themselves to give their electoral votes to the national popular vote winner?

Yes, and several states, including California, already have pledged to do so if enough other states join the reform bandwagon. This state-led reform movement — the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact — will not affect the 2016 race, but it might change the rules for 2020 and beyond.

8. What’s so great about direct election?

It counts all voters equally — just as each state counts all voters equally in a governor’s race.

9. How about encouraging states to move away from winner-take-all within the state?

Nebraska and Maine do this already. Whoever wins a congressional district gets one electoral vote for that district, and whoever wins the state as a whole gets two bonus electoral votes (corresponding to the state’s two senators). This system is OK for Nebraska and Maine, but it would be bad for other states. Nebraska has only three congressional districts; Maine has two. So whoever wins each state is mathematically guaranteed to win at least a majority of the state’s electoral votes. (Call it winner-take-most-and-maybe-all.) But in bigger states — Pennsylvania, for example — a candidate who wins a large statewide majority might actually fail to win a majority of the state’s electoral votes, which hardly seems fair — especially because congressional district shapes can be gerrymandered.

10. Is the current electoral college system skewed toward either party?

No, it’s pretty balanced at present. True, it favored George W. Bush in 2000, but it could just as easily have favored Al Gore had the election season unfolded differently. Today, Democrats tend to win more big states, which gives them a boost, thanks to winner-take-all. But Republicans tend to win more states overall, which gives them an offsetting boost because each state starts with a two-electoral-vote bonus.

Akhil Reed Amar teaches constitutional law at Yale and is the author of “The Constitution Today: Timeless Lessons for the Issues of our Era.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

Calmes: Donald Trump inspires yet another profile in cowardice

April 14, 2024

Abcarian: Never forget — Nicole Brown Simpson’s murder redefined our understanding of domestic violence

Opinion: Why it’s hard to muster even a ‘meh’ over Trump’s New York criminal trial

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Opinion: Can you beat this epic commute? Take the 10 to the 86 to the 111 to the 8 ...

Opinion: In Utah, the Capitol really is the people’s house

April 12, 2024

Opinion: My son was killed with a gun. Like too many California parents, I don’t know who did it

Opinion: How Rodney King helped O.J. Simpson win a not-guilty verdict

April 11, 2024

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Research & Reports

The Electoral College Explained

A national popular vote would help ensure that every vote counts equally, making American democracy more representative.

- Electoral College Reform

In the United States, the presidency is decided not by the national popular vote but by the Electoral College — an outdated and convoluted system that sometimes yields results contrary to the choice of the majority of American voters. On five occasions, including in two of the last six elections, candidates have won the Electoral College, and thus the presidency, despite losing the nationwide popular vote.

The Electoral College has racist origins — when established, it applied the three-fifths clause, which gave a long-term electoral advantage to slave states in the South — and continues to dilute the political power of voters of color. It incentivizes presidential campaigns to focus on a relatively small number of “swing states.” Together, these dynamics have spurred debate about the system’s democratic legitimacy.

To make the United States a more representative democracy, reformers are pushing for the presidency to be decided instead by the national popular vote, which would help ensure that every voter counts equally.

What is the Electoral College and how does it work?

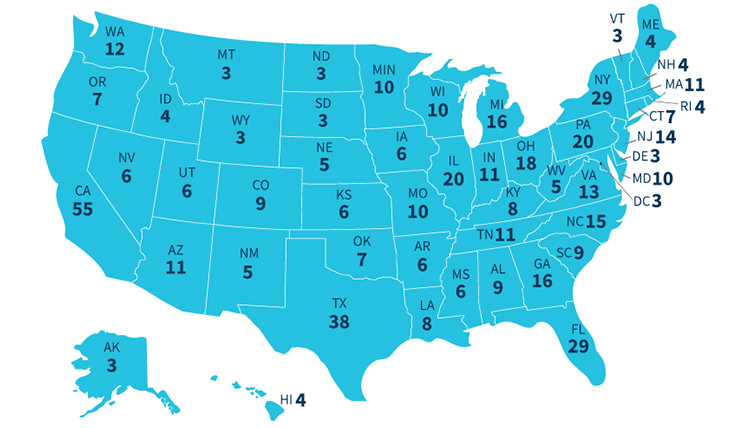

The Electoral College is a group of intermediaries designated by the Constitution to select the president and vice president of the United States. Each of the 50 states is allocated presidential electors equal to the number of its representatives and senators . The ratification of the 23rd Amendment in 1961 allowed citizens in the District of Columbia to participate in presidential elections as well; they have consistently had three electors.

In total, the Electoral College comprises 538 members . A presidential candidate must win a majority of the electoral votes cast to win — at least 270 if all 538 electors vote.

The Constitution grants state legislatures the power to decide how to appoint their electors. Initially, a number of state legislatures directly selected their electors , but during the 19th century they transitioned to the popular vote, which is now used by all 50 states . In other words, each awards its electoral votes to the presidential candidate chosen by the state’s voters.

Forty-eight states and the District of Columbia use a winner-take-all system, awarding all of their electoral votes to the popular vote winner in the state. Maine and Nebraska award one electoral vote to the popular vote winner in each of their congressional districts and their remaining two electoral votes to the statewide winner. Under this system, those two states sometimes split their electoral votes among candidates.

In the months leading up to the general election, the political parties in each state typically nominate their own slates of would-be electors. The state’s popular vote determines which party’s slates will be made electors. Members of the Electoral College meet and vote in their respective states on the Monday after the second Wednesday in December after Election Day. Then, on January 6, a joint session of Congress meets at the Capitol to count the electoral votes and declare the outcome of the election, paving the way for the presidential inauguration on January 20.

How was the Electoral College established?

The Constitutional Convention in 1787 settled on the Electoral College as a compromise between delegates who thought Congress should select the president and others who favored a direct nationwide popular vote. Instead, state legislatures were entrusted with appointing electors.

Article II of the Constitution, which established the executive branch of the federal government, outlined the framers’ plan for the electing the president and vice president. Under this plan, each elector cast two votes for president; the candidate who received the most votes became the president, with the second-place finisher becoming vice president — which led to administrations in which political opponents served in those roles. The process was overhauled in 1804 with the ratification of the 12th Amendment , which required electors to cast votes separately for president and vice president.

How did slavery shape the Electoral College?

At the time of the Constitutional Convention, the northern states and southern states had roughly equal populations . However, nonvoting enslaved people made up about one-third of the southern states’ population. As a result, delegates from the South objected to a direct popular vote in presidential elections, which would have given their states less electoral representation.

The debate contributed to the convention’s eventual decision to establish the Electoral College, which applied the three-fifths compromise that had already been devised for apportioning seats in the House of Representatives. Three out of five enslaved people were counted as part of a state’s total population, though they were nonetheless prohibited from voting.

Wilfred U. Codrington III, an assistant professor of law at Brooklyn Law School and a Brennan Center fellow, writes that the South’s electoral advantage contributed to an “almost uninterrupted trend” of presidential election wins by southern slaveholders and their northern sympathizers throughout the first half of the 19th century. After the Civil War, in 1876, a contested Electoral College outcome was settled by a compromise in which the House awarded Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency with the understanding that he would withdraw military forces from the Southern states. This led to the end of Reconstruction and paved the way for racial segregation under Jim Crow laws.

Today, Codrington argues, the Electoral College continues to dilute the political power of Black voters: “Because the concentration of black people is highest in the South, their preferred presidential candidate is virtually assured to lose their home states’ electoral votes. Despite black voting patterns to the contrary, five of the six states whose populations are 25 percent or more black have been reliably red in recent presidential elections. … Under the Electoral College, black votes are submerged.”

What are faithless electors?

Ever since the 19th century reforms, states have expected their electors to honor the will of the voters. In other words, electors are now pledged to vote for the winner of the popular vote in their state. However, the Constitution does not require them to do so, which allows for scenarios in which “faithless electors” have voted against the popular vote winner in their states. As of 2016, there have been 90 faithless electoral votes cast out of 23,507 in total across all presidential elections. The 2016 election saw a record-breaking seven faithless electors , including three who voted for former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who was not a presidential candidate at the time.

Currently, 33 states and the District of Columbia require their presidential electors to vote for the candidate to whom they are pledged. Only 5 states, however, impose a penalty on faithless electors, and only 14 states provide for faithless electors to be removed or for their votes to be canceled. In July 2020, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld existing state laws that punish or remove faithless electors.

What happens if no candidate wins a majority of Electoral College votes?

If no ticket wins a majority of Electoral College votes, the presidential election is sent to the House of Representatives for a runoff. Unlike typical House practice, however, each state only gets one vote, decided by the party that controls the state’s House delegation. Meanwhile, the vice-presidential race is decided in the Senate, where each member has one vote. This scenario has not transpired since 1836 , when the Senate was tasked with selecting the vice president after no candidate received a majority of electoral votes.

Are Electoral College votes distributed equally between states?

Each state is allocated a number of electoral votes based on the total size of its congressional delegation. This benefits smaller states, which have at least three electoral votes — including two electoral votes tied to their two Senate seats, which are guaranteed even if they have a small population and thus a small House delegation. Based on population trends, those disparities will likely increase as the most populous states are expected to account for an even greater share of the U.S. population in the decades ahead.

What did the 2020 election reveal about the Electoral College?

In the aftermath of the 2020 presidential race, Donald Trump and his allies fueled an effort to overturn the results of the election, spreading repeated lies about widespread voter fraud. This included attempts by a number of state legislatures to nullify some of their states’ votes, which often targeted jurisdictions with large numbers of Black voters. Additionally, during the certification process for the election, some members of Congress also objected to the Electoral College results, attempting to throw out electors from certain states. While these efforts ultimately failed, they revealed yet another vulnerability of the election system that stems from the Electoral College.

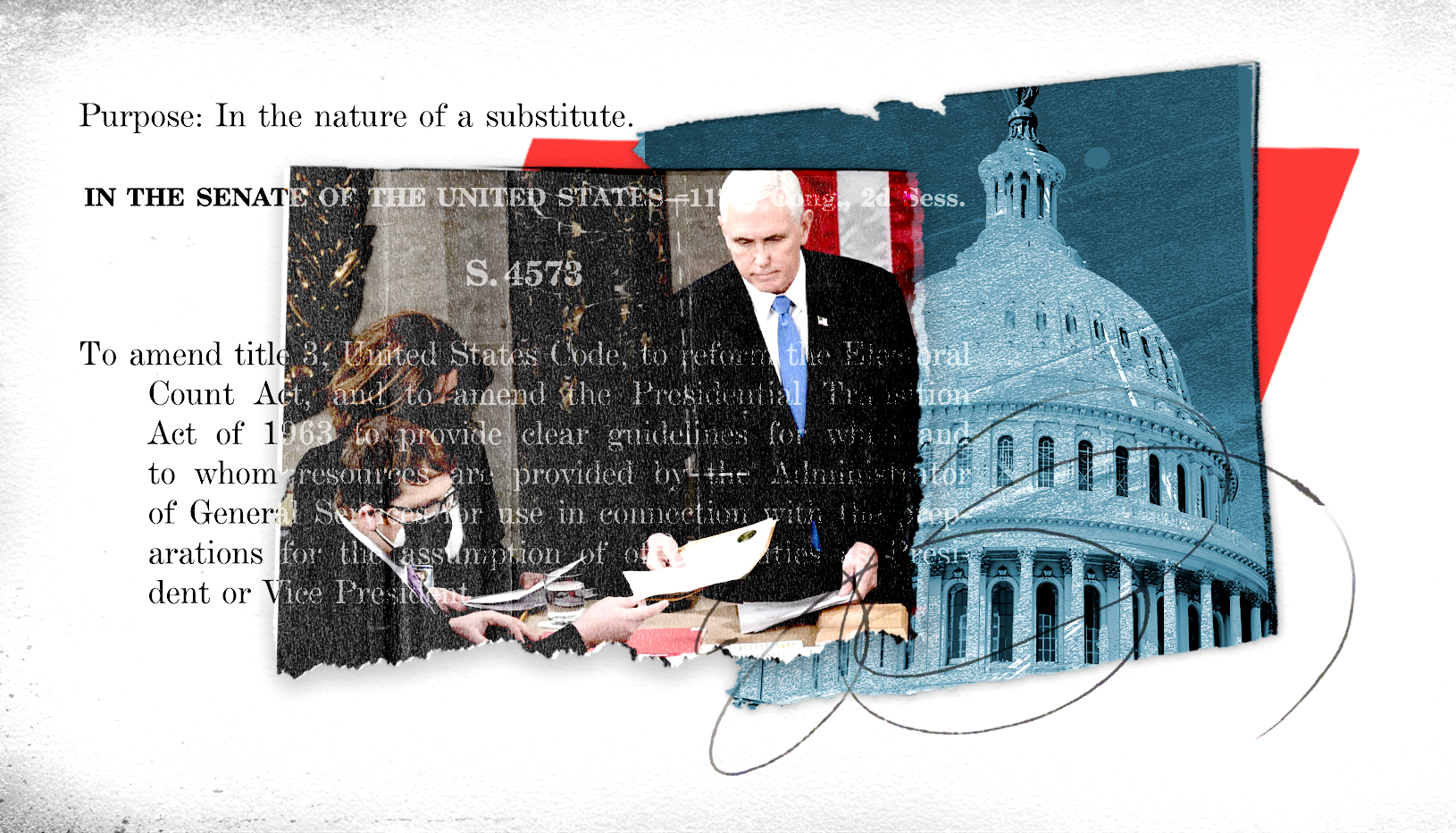

The Electoral Count Reform Act , enacted in 2023, addresses these problems. Among other things, it clarifies which state officials have the power to appoint electors, and it bars any changes to that process after Election Day, preventing state legislatures from setting aside results they do not like. The new law also raises the threshold for consideration of objections to electoral votes. It is now one-fifth of each chamber instead of one senator and one representative. Click here for more on the changes made by the Electoral Count Reform Act.

What are ways to reform the Electoral College to make presidential elections more democratic?

Abolishing the Electoral College outright would require a constitutional amendment. As a workaround, scholars and activist groups have rallied behind the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPV), an effort that started after the 2000 election. Under it, participating states would commit to awarding their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote.

In other words, the NPV would formally retain the Electoral College but render it moot, ensuring that the winner of the national popular vote also wins the presidency. If enacted, the NPV would incentivize presidential candidates to expand their campaign efforts nationwide, rather than focus only on a small number of swing states.

For the NPV to take effect, it must first be adopted by states that control at least 270 electoral votes. In 2007, Maryland became the first state to enact the compact. As of 2019, a total of 19 states and Washington, DC, which collectively account for 196 electoral votes, have joined.

The public has consistently supported a nationwide popular vote. A 2020 poll by Pew Research Center, for example, found that 58 percent of adults prefer a system in which the presidential candidate who receives the most votes nationwide wins the presidency.

Related Resources

How Electoral Votes Are Counted for the Presidential Election

The Electoral Count Reform Act addresses vulnerabilities exposed by the efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

NATO’s Article 5 Collective Defense Obligations, Explained

Here’s how a conflict in Europe would implicate U.S. defense obligations.

The Supreme Court ‘Shadow Docket’

The conservative justices are increasingly using a secretive process to issue consequential decisions.

Preclearance Under the Voting Rights Act

For decades, the law blocked racially discriminatory election rules and voting districts — and it could do so again, if Congress acts.

Informed citizens are democracy’s best defense

Electoral College

What is the Electoral College?

The Electoral College is a process, not a place. The Founding Fathers established it in the Constitution, in part, as a compromise between the election of the President by a vote in Congress and election of the President by a popular vote of qualified citizens.

What is the process?

The Electoral College process consists of the selection of the electors , the meeting of the electors where they vote for President and Vice President, and the counting of the electoral votes by Congress.

How many electors are there? How are they distributed among the States?

The Electoral College consists of 538 electors. A majority of 270 electoral votes is required to elect the President. Your State has the same number of electors as it does Members in its Congressional delegation: one for each Member in the House of Representatives plus two Senators. Read more about the allocation of electoral votes.

The District of Columbia is allocated 3 electors and treated like a State for purposes of the Electoral College under the 23rd Amendment of the Constitution. For this reason, in the following discussion, the word “State” also refers to the District of Columbia and “Executive” to the State Governors and the Mayor of the District of Columbia.

How are my electors chosen? What are their qualifications? How do they decide who to vote for?

Each candidate running for President in your State has their own group of electors (known as a slate). The slates are generally chosen by the candidate’s political party in your State, but State laws vary on how the electors are selected and what their responsibilities are. Read more about the qualifications of the electors and restrictions on who the electors may vote for .

What happens in the general election? Why should I vote?

The general election is held every four years on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. When you vote for a Presidential candidate you are actually voting for your candidate's preferred electors. Learn more about voting for the electors.

Most States have a “winner-take-all” system that awards all electors to the Presidential candidate who wins the State's popular vote. However, Maine and Nebraska each have a variation of “proportional representation.” Read more about the allocation of electors among the States.

What happens after the general election?

After the general election, your State's Executive prepares a Certificate of Ascertainment listing the names of all the individuals on the slates for each candidate. The Certificate of Ascertainment also lists the number of votes each individual received and shows which individuals were appointed as your State's electors. Your State’s Certificate of Ascertainment is sent to NARA as part of the official records of the Presidential election.

The meeting of the electors takes place on the first Tuesday after the second Wednesday in December after the general election. The electors meet in their respective States, where they cast their votes for President and Vice President on separate ballots. Your State’s electors’ votes are recorded on a Certificate of Vote, which is prepared at the meeting by the electors. Your State’s Certificate of Vote is sent to Congress, where the votes are counted, and to NARA, as part of the official records of the Presidential election.

Each State’s electoral votes are counted in a joint session of Congress on the 6th of January in the year following the meeting of the electors. Members of the House and Senate meet in the House Chamber to conduct the official count of electoral votes. The Vice President of the United States, as President of the Senate, presides over the count in a strictly ministerial manner and announces the results of the vote. The President of the Senate then declares which persons, if any, have been elected President and Vice President of the United States.

The President-elect takes the oath of office and is sworn in as President of the United States on January 20th in the year following the general election.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Electoral College

By: History.com Editors

Updated: November 4, 2020 | Original: January 12, 2010

When Americans vote for President and Vice President of the United States, they are actually voting for presidential electors, known collectively as the Electoral College. It is these electors, chosen by the people, who elect the chief executive. The Constitution assigns each state a number of electors equal to the combined total of the state’s Senate and House of Representatives delegations; at present, the number of electors per state ranges from three (District of Columbia) to 55 (California), for a total of 538. To be elected President of the United States, a candidate needs a majority of 270 electoral votes.

How the Electoral College Works

Aside from Members of Congress and people holding offices of “Trust or Profit” under the Constitution , anyone may serve as an elector.

In each presidential election year, a group of candidates for elector is nominated by political parties and other groupings in each state, usually at a state party convention or by the party-state committee. It is these elector-candidates, rather than the presidential and vice-presidential nominees, for whom the people vote in the November election, which is held on Tuesday after the first Monday in November. In most states, voters cast a single vote for the slate of electors pledged to the party presidential and vice-presidential candidates of their choice. The slate winning the most popular votes is elected. This is known as the winner take all system, or general ticket system.

Electors assemble in their respective states on Monday after the second Wednesday in December. They are pledged and expected, but not required, to vote for the candidates they represent. Separate ballots are cast for President and Vice President, after which the Electoral College ceases to exist for another four years. The electoral vote results are counted and certified by a joint session of Congress, held on January 6 of the year succeeding the election. A majority of electoral votes (currently 270 of 538) is required to win. If no candidate receives a majority, then the President is elected by the House of Representatives and the Vice President is elected by the Senate , a process known as contingent election.

The Electoral College in the U.S. Constitution

The original purpose of the Electoral College was to reconcile differing state and federal interests, provide a degree of popular participation in the election, give the less populous states some additional leverage in the process by providing “senatorial” electors, preserve the presidency as independent of Congress and generally insulate the election process from political manipulation.

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 considered several methods of electing the President, including selection by Congress, by the governors of the states, by the state legislatures, by a special group of Members of Congress chosen by lot and by direct popular election. Late in the convention, the matter was referred to the Committee of Eleven on Postponed Matters, which devised the Electoral College system in its original form. This plan, which met with widespread approval by the delegates, was incorporated into the final document with only minor changes.

The Constitution gave each state a number of electors equal to the combined total of its membership in the Senate (two to each state, the “senatorial” electors) and its delegation in the House of Representatives (currently ranging from one to 52 Members). The electors are chosen by the states “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct” (U.S. Constitution, Article II, section 1).

Qualifications for the office are broad: the only people prohibited from serving as electors are Senators, Representatives and people “holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States.”

In order to forestall partisan intrigue and manipulation, the electors assemble in their respective states and cast their ballots as state units, rather than meet at a central location. At least one of the candidates for whom the electors vote must be an inhabitant of another state. A majority of electoral votes is necessary to elect, a requirement intended to insure broad acceptance of a winning candidate, while election by the House was provided as a default method in the event of Electoral College deadlock. Finally, Congress was empowered to set nationwide dates for choice and meeting of electors.

All the foregoing structural elements of the Electoral College system remain in effect currently. The original method of electing the President and Vice President, however, proved unworkable and was replaced by the 12th Amendment, ratified in 1804. Under the original system, each elector cast two votes for President (for different candidates), and no vote for Vice President. The votes were counted and the candidate receiving the most votes, provided it was a majority of the number of electors, was elected President, and the runner-up became Vice President. The 12th Amendment replaced this system with separate ballots for President and Vice President, with electors casting a single vote for each office.

The Electoral College Today

Notwithstanding the founders’ efforts, the Electoral College system almost never functioned as they intended, but, as with so many constitutional provisions, the document prescribed only the system’s basic elements, leaving ample room for development. As the republic evolved, so did the Electoral College system, and, by the late 19th century, the following range of constitutional, legal and political elements were in place on both a state and federal level:

Allocation of Electors and Electoral Votes

The Constitution gives each state a number of electors equal to the combined total of its Senate membership (two for each state) and House of Representatives delegation (currently ranging from one to 55, depending on population). The 23rd Amendment provides an additional three electors to the District of Columbia. The number of electoral votes per state thus currently ranges from three (for seven states and D.C.) to 55 for California , the most populous state.

The total number of electors each state gets are adjusted following each decennial census in a process called reapportionment, which reallocates the number of Members of the House of Representatives to reflect changing rates of population growth (or decline) among the states. Thus, a state may gain or lose electors following reapportionment, but it always retains its two “senatorial” electors, and at least one more reflecting its House delegation. Popular Election of Electors

Popular Election of Electors

Today, all presidential electors are chosen by voters, but in the early republic, more than half the states chose electors in their legislatures, thus eliminating any direct involvement by the voting public in the election. This practice changed rapidly after the turn of the nineteenth century, however, as the right to vote was extended to an ever-wider segment of the population. As the electorate continued to expand, so did the number of persons able to vote for presidential electors: Its present limit is all eligible citizens age 18 or older. The tradition that the voters choose the presidential electors thus became an early and permanent feature of the Electoral College system, and, while it should be noted that states still theoretically retain the constitutional right to choose some other method, this is extremely unlikely.

The existence of the presidential electors and the duties of the Electoral College are so little noted in contemporary society that most American voters believe that they are voting directly for a President and Vice President on Election Day. Although candidates for elector may be well-known persons, such as governors, state legislators or other state and local officials, they generally do not receive public recognition as electors. In fact, in most states, the names of individual electors do not appear anywhere on the ballot; instead, only those of the various candidates for President and Vice President appear, usually prefaced by the words “electors for.” Moreover, electoral votes are commonly referred to as having “been awarded” to the winning candidate, as if no human beings were involved in the process.

The Electors: Ratifying the Voter’s Choice

Presidential electors in contemporary elections are expected, and in many cases pledged, to vote for the candidates of the party that nominated them. While there is evidence that the founders assumed the electors would be independent actors, weighing the merits of competing presidential candidates, they have been regarded as agents of the public will since the first decade under the Constitution. They are expected to vote for the presidential and vice-presidential candidates of the party that nominated them.

Notwithstanding this expectation, individual electors have sometimes not honored their commitment, voting for a different candidate or candidates than the ones to whom they were pledged. They are known as “faithless” or “unfaithful” electors. In fact, the balance of opinion by constitutional scholars is that, once electors have been chosen, they remain constitutionally free agents, able to vote for any candidate who meets the requirements for President and Vice President. Faithless electors have, however, been few in number (in the 20th century, there was one each in 1948, 1956, 1960, 1968, 1972, 1976, 1988, and 2000), and have never influenced the outcome of a presidential election.

How the Electoral College Works in Each State

Nomination of elector-candidates is another of the many aspects of this system left to state and political party preferences. Most states prescribe one of two methods: 34 states require that candidates for the office of presidential elector be nominated by state party conventions, while a further ten mandate nomination by the state party’s central committee. The remaining states use a variety of methods, including nomination by the governor (on the recommendation of party committees), by primary election, and by the party’s presidential nominee.

Joint Tickets: One Vote for President and Vice President

General election ballots, which are regulated by state election laws and authorities, offer voters joint candidacies for President and Vice President for each political party or other groups. Thus, voters cast a single vote for electors pledged to the joint ticket of the party they represent. They cannot effectively vote for a president from one party and a vice president from another unless their state provides for write-in votes.

General Election Day

Elections for all federal elected officials are held on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November in even-numbered years and presidential elections are held in every year divisible by four. Congress selected this day in 1845; previously, states held elections on different days between September and November, a practice that sometimes led to multiple voting across state lines and other fraudulent practices. By tradition, November was chosen because the harvest was in and farmers were able to take the time needed to vote. Tuesday was selected because it gave a full day’s travel between Sunday, which was widely observed as a strict day of rest, and Election Day. Travel was also easier throughout the north during November, before winter had set in.

The Electors Convene

The 12th Amendment requires electors to meet “in their respective states…” This provision was intended to deter manipulation of the election by having the state electoral colleges meet simultaneously, but keeping them separate. Congress sets the date on which the electors meet, currently the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December. The electors almost always meet in the state capital, usually in the capitol building or state house itself. They vote “by ballot” separately for President and Vice President (at least one of the candidates must be from another state). The results are then endorsed, and copies are sent to the Vice President (in his capacity as President of the Senate); the secretary of state of their state; the Archivist of the United States; and the judge of the federal district court of the district in which the electors met. Having performed their constitutional duty, the electors adjourn, and the Electoral College ceases to exist until the next presidential election.

Congress Counts and Certifies the Vote

The final step in the presidential election process (aside from the presidential inaugural on January 20) is the counting and certification of the electoral votes by Congress. The House of Representatives and Senate meet in joint session in the House chamber on January 6 of the year following the presidential election at 1:00 pm. The Vice President, who presides in his capacity as President of the Senate, opens the electoral vote certificates from each state in alphabetical order. He then passes the certificates to four tellers (vote counters), two appointed by each house, who announce the results. The votes are then counted and the results are announced by the Vice President. The candidate who receives a majority of electoral votes (currently 270 of 538) is declared the winner by the Vice President, an action that constitutes “a sufficient declaration of the persons, if any, elected President and Vice President of the States.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

AP® US Government

Electoral college: ap® us government crash course.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

What is the Electoral College?

Because it is unique to our political system, the AP® US Government & Politics exam is almost certain to test you on your knowledge of the Electoral College. What is the Electoral College, again? No—it’s not somewhere you get accepted to if you get a lot of 5’s on your AP® exams.

You’re probably too young to remember the 2000 presidential election, but you’ve certainly heard about it, and probably talked about it in class. George W. Bush, was elected despite losing the national popular vote (popular meaning, the most votes) because he was awarded Florida’s electoral votes.

Electoral College Origins

The Founding Fathers didn’t have much faith in the voters to pick the president without some help from their leaders. They felt that the public had a limited grasp of the issues. So the Electoral College was designed to balance the popular will with political leaders’ wisdom. The voters’ choices would be filtered through state legislatures.

In a presidential election, each state legislature sends a slate of electors—the number of electors based on a state’s number of congressional districts plus two (for its senators) to go to Washington and elect a president.

Most state legislatures selected electors who would vote for the candidate the voters chose—but the Constitution (Article II, Section 1) does not require this.

Then, the candidate who received the majority of the electoral vote became president. Usually—but not always—this candidate also happened to have won the popular vote.

There have been three presidential candidates who won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College vote:

1. Samuel Tilden losing to Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876

2. Grover Cleveland losing to Benjamin Harrison in 1888

3. Al Gore losing to George W. Bush in 2000

There have been a number of elections that came close to having the same mixed result. For example, in 2004, John Kerry lost to George W. Bush by over three million popular votes, but the flip of one state—Ohio—would have made Kerry president. (Surely, the irony would not have been lost on Bush.)

Effects of the Electoral College

The AP® US Government & Politics exam will want you to know what the effects of the Electoral College are.

One effect is that which is mentioned above—sometimes the Electoral College flouts the will of the public. Today, all of the state legislatures (with the exceptions of Maine and Nebraska, which award by congressional district) award all of their state’s electoral votes to the popular vote winner in that state.This is referred to as the “winner-take-all” system.

This means that, even if a Republican candidate get millions of votes in California, or a Democrat gets millions in Texas, they still lose all of that state’s electoral votes.

This dynamic has the additional effect of leading candidates to only spend money and campaign in swing states—states where either party’s candidate has a chance of winning the state’s popular vote.

This is why states like Ohio, Virginia and Florida, which are fairly evenly split between Democrats and Republicans, get so much attention from candidates.

How are Electoral College Votes Apportioned?

As mentioned, each state receives a number of electoral votes equivalent to its number of senators and representatives, for a total of 538 electoral votes. The votes are apportioned the same way congressional districts are—every ten years by the Census. A candidate needs 270 electoral votes to become president.

The most populous states have the most electoral votes. In 2016, for example, California will have 55 electoral votes, Texas will have 38, Florida and New York will have 29, and Illinois and Pennsylvania will have 20. It is possible for a candidate to win the presidency with the electoral votes of only the ten most populous states.

On the other hand, sparsely populated states like Montana and Vermont only have three electoral votes. Still—the electoral vote gives these states more influence than a popular vote-based system would. Three electoral votes can change the result in a close electoral vote.

Criticisms of the Electoral College

There are lots of criticisms of the Electoral College.

The most common complaint is that whoever represents the popular will—the winner of the popular vote—should be president. Half a million more voters voted for Al Gore in 2000 than voted for George W. Bush.

The other criticism is that by focusing the presidential contest on the swing states, the Electoral College deprives voters in solidly partisan states (like Republican Texas or Democratic California) from being heard.

It is also said that minority party voters in these states (e.g., Democrats in Texas or Republicans in California) have little incentive to vote, since their votes won’t affect the outcome of the election at all.

There have been many efforts to amend the Constitution and do away with the Electoral College over the years, but none of them have picked up much steam.

The Electoral College in Action

The electors meet at state capitols in December to cast their ballots. The ballots are then sealed and sent to Congress, where the president of the Senate—the vice president—opens and counts the ballots in January.

The media is allowed to ask electors how they voted in December, and they typically answer. Most states require electors to cast their ballot for the candidate they were chosen to represent—but some don’t.

In 2000, for example, since New Hampshire doesn’t require electors to vote for the candidate the voters chose, some pundits thought the state’s electors, pledged to Bush, might defect and vote for Gore. They didn’t.

If no candidate wins a majority of Electoral College votes—possible in an election with three or more major candidates—the House selects from the top three presidential candidates, and each state gets one vote. D.C. does not get a vote. The winner must get 26 or more state votes, with the House re-voting until this happens.

The Senate selects from the top two vice presidential candidates, and each senator gets one vote. The majority vote winner (51 votes) is sworn in as vice president.

Now let’s take a look at a free-response question about the Electoral College.

A Sample Free Response Question

1. Describe the winner-take-all feature of the Electoral College.

2. Explain one way in which the winner-take-all feature of the Electoral College affects how presidential candidates from the two major political parties run their campaigns.

3. Explain one way in which the winner-take-all feature of the Electoral College hinders third party candidates.

4. Explain two reasons the Electoral College has not been abolished.

It’s easy to answer (a) – discuss how, for all states except Maine and Nebraska, the winner of the popular vote in a state gets all of its electoral votes.

For (b), you want to discuss the concept of ‘swing states’ – parties closely divided between the states whose electoral votes are up for grabs. Candidates spend time and money here at the expense of solidly partisan states.

Part (c) will require you to discuss the dominance of the two parties, Democratic and Republican, and how third parties are unlikely to get any electoral votes at all—and thus no voice in the Electoral College—unless they outperform the two larger parties.

Part (d) will require you to discuss the amendment process—the only way the Electoral College can be abolished—and how the swing states are unlikely to support decreasing their voice in presidential elections. You will also want to discuss fears that a popular vote-based election would favor big cities and major population centers at the expense of rural and sparsely populated areas. (The argument here is that candidates would only spend time in money in places with lots of votes to be had.)

The Wrap Up

Remember, you are likely to encounter questions about the Electoral College on the AP® US Government exam.

The Electoral College is unique to our democracy. The most important points to remember about it are:

1. The Electoral College was created by the Founding Fathers because they believed voters weren’t well-informed enough to choose the president on their own

2. The Electoral College uses a winner-take all system

3. The Electoral College encourages candidates to campaign in ‘swing’ states where the parties are closely matched

4. Occasionally, the winner of the Electoral College (and thus, the presidency) actually loses the popular vote.

Remember, the Electoral College is not as complex as it might seem at first blush. Americans technically vote for electors who support their favored candidate. These 538 electors then convene the month after the election to vote for the president. If you can grasp this idea and the bullet points above, you will be well prepared for Electoral College questions on the US Government & Politics exam.

Looking for AP® US Government practice?

Kickstart your AP® US Government prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Interested in a school license?

Bring Albert to your school and empower all teachers with the world's best question bank for: ➜ SAT® & ACT® ➜ AP® ➜ ELA, Math, Science, & Social Studies aligned to state standards ➜ State assessments Options for teachers, schools, and districts.

It’s time to abolish the Electoral College

- Download the full report

Darrell M. West Darrell M. West Senior Fellow - Center for Technology Innovation , Douglas Dillon Chair in Governmental Studies

October 15, 2019

- 14 min read

For years when I taught campaigns and elections at Brown University, I defended the Electoral College as an important part of American democracy. I said the founders created the institution to make sure that large states did not dominate small ones in presidential elections, that power between Congress and state legislatures was balanced, and that there would be checks and balances in the constitutional system.

In recent years, though, I have changed my view and concluded it is time to get rid of the Electoral College. In this paper, I explain the history of the Electoral College, why it no longer is a constructive force in American politics, and why it is time to move to the direct popular election of presidents. Several developments have led me to alter my opinion on this institution: income inequality, geographic disparities, and how discrepancies between the popular vote and Electoral College are likely to become more commonplace given economic and geographic inequities. The remainder of this essay outlines why it is crucial to abolish the Electoral College.

The original rationale for the Electoral College

The framers of the Constitution set up the Electoral College for a number of different reasons. According to Alexander Hamilton in Federalist Paper Number 68, the body was a compromise at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia between large and small states. Many of the latter worried that states such as Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia would dominate the presidency so they devised an institution where each state had Electoral College votes in proportion to the number of its senators and House members. The former advantaged small states since each state had two senators regardless of its size, while the latter aided large states because the number of House members was based on the state’s population.

In addition, there was considerable discussion regarding whether Congress or state legislatures should choose the chief executive. Those wanting a stronger national government tended to favor Congress, while states’ rights adherents preferred state legislatures. In the end, there was a compromise establishing an independent group chosen by the states with the power to choose the president.

But delegates also had an anti-majoritarian concern in mind. At a time when many people were not well-educated, they wanted a body of wise men (women lacked the franchise) who would deliberate over leading contenders and choose the best man for the presidency. They explicitly rejected a popular vote for president because they did not trust voters to make a wise choice.

How it has functioned in practice

In most elections, the Electoral College has operated smoothly. State voters have cast their ballots and the presidential candidate with the most votes in a particular state has received all the Electoral College votes of that state, except for Maine and Nebraska which allocate votes at the congressional district level within their states.

But there have been several contested elections. The 1800 election deadlocked because presidential candidate Thomas Jefferson received the same number of Electoral College votes as his vice presidential candidate Aaron Burr. At that time, the ballot did not distinguish between Electoral College votes for president and vice president. On the 36th ballot, the House chose Jefferson as the new president. Congress later amended the Constitution to prevent that ballot confusion from happening again.

Just over two decades later, Congress had an opportunity to test the newly established 12th Amendment . All four 1824 presidential aspirants belonged to the same party, the Democratic-Republicans, and although each had local and regional popularity, none of them attained the majority of their party’s Electoral College votes. Andrew Jackson came the closest, with 99 Electoral College votes, followed by John Quincy Adams with 84 votes, William Crawford with 41, and Henry Clay with 37.

Because no candidate received the necessary 131 votes to attain the Electoral College majority, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives. As dictated by the 12th Amendment , each state delegation cast one vote among the top three candidates. Since Clay no longer was in the running, he made a deal with Adams to become his secretary of state in return for encouraging congressional support for Adams’ candidacy. Even though Jackson had received the largest number of popular votes, he lost the presidency through what he called a “corrupt bargain” between Clay and Adams.

America was still recovering from the Civil War when Republican Rutherford Hayes ran against Democrat Samuel Tilden in the 1876 presidential election. The race was so close that the electoral votes of just four states would determine the presidency. On Election Day, Tilden picked up the popular vote plurality and 184 electoral votes, but fell one vote short of an Electoral College majority. However, Hayes claimed that his party would have won Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina if not for voter intimidation against African American voters; and in Oregon, one of Hayes’ three electoral votes was in dispute.

Instead of allowing the House to decide the presidential winner, as prescribed by the 12th Amendment, Congress passed a new law to create a bipartisan Electoral Commission . Through this commission, five members each from the House, Senate, and Supreme Court would assign the 20 contested electoral votes from Louisiana, Florida, South Carolina, and Oregon to either Hayes or Tilden. Hayes became president when this Electoral Commission ultimately gave the votes of the four contested states to him. The decision would have far-reaching consequences because in return for securing the votes of the Southern states, Hayes agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, thereby paving the way for vigilante violence against African Americans and the denial of their civil rights.

Allegations of election unfairness also clouded the 2000 race. The contest between Republican George Bush and Democrat Al Gore was extremely close, ultimately resting on the fate of Florida’s 25 electoral votes. Ballot controversies in Palm Beach County complicated vote tabulation. It used the “butterfly ballot” design , which some decried as visually confusing. Additionally, other Florida counties that required voters to punch perforated paper ballots had difficulty discerning the voters’ choices if they did not fully detach the appropriate section of the perforated paper.

Accordingly, on December 8, 2000, the Florida Supreme Court ordered manual recounts in counties that reported statistically significant numbers of undervotes. The Bush campaign immediately filed suit, and in response, the U.S. Supreme Court paused manual recounts to hear oral arguments from candidates. On December 10, in a landmark 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the Florida Supreme Court’s recount decision, ruling that a manual recount would violate the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Bush won Florida’s Electoral College votes and thus the presidency even though Gore had won the popular vote by almost half a million votes.

The latest controversy arose when Donald Trump lost the popular vote by almost three million ballots yet won the Electoral College by 74 votes. That made him the fifth U.S. chief executive to become president without winning the popular vote. This discrepancy between the Electoral College and the popular vote created considerable contentiousness about the electoral system. It set the Trump presidency off on a rough start and generated a critical tone regarding his administration.

The faithless elector problem

In addition to the problems noted above, the Electoral College suffers from another difficulty known as the “faithless elector” issue in which that body’s electors cast their ballot in opposition to the dictates of their state’s popular vote. Samuel Miles, a Federalist from Pennsylvania, was the first of this genre as for unknown reasons, he cast his vote in 1796 for the Democratic-Republican candidate, Thomas Jefferson, even though his own Federalist party candidate John Adams had won Pennsylvania’s popular vote.

Miles turned out to be the first of many. Throughout American history, 157 electors have voted contrary to their state’s chosen winner. Some of these individuals dissented for idiosyncratic reasons, but others did so because they preferred the losing party’s candidate. The precedent set by these people creates uncertainty about how future Electoral College votes could proceed.

This possibility became even more likely after a recent court decision. In the 2016 election, seven electors defected from the dictates of their state’s popular vote. This was the highest number in any modern election. A Colorado lawsuit challenged the legality of state requirements that electors follow the vote of their states, something which is on the books in 29 states plus the District of Columbia. In the Baca v. Hickenlooper case, a federal court ruled that states cannot penalize faithless electors, no matter the intent of the elector or the outcome of the state vote.

Bret Chiafalo and plaintiff Michael Baca were state electors who began the self-named “Hamilton Electors” movement in which they announced their desire to stop Trump from winning the presidency. Deriving their name from Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, they convinced a few members of the Electoral College to cast their votes for other Republican candidates, such as John Kasich or Mitt Romney. When Colorado decided to nullify Baca’s vote, he sued. A three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit ruled that Colorado’s decision to remove Baca’s vote was unconstitutional since the founders were explicit about the constitutional rights of electors to vote independently. Based on this legal ruling and in a highly polarized political environment where people have strong feelings about various candidates, it is possible that future faithless electors could tip the presidency one way or another, thereby nullifying the popular vote.

Why the Electoral College is poorly suited for an era of high income inequality and widespread geographic disparities

The problems outlined above illustrate the serious issues facing the Electoral College. Having a president who loses the popular vote undermines electoral legitimacy. Putting an election into the House of Representatives where each state delegation has one vote increases the odds of insider dealings and corrupt decisions. Allegations of balloting irregularities that require an Electoral Commission to decide the votes of contested states do not make the general public feel very confident about the integrity of the process. And faithless electors could render the popular vote moot in particular states.

Yet there is a far more fundamental threat facing the Electoral College. At a time of high income inequality and substantial geographical disparities across states, there is a risk that the Electoral College will systematically overrepresent the views of relatively small numbers of people due to the structure of the Electoral College. As currently constituted, each state has two Electoral College votes regardless of population size, plus additional votes to match its number of House members. That format overrepresents small- and medium-sized states at the expense of large states.

That formula is problematic at a time when a Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program study found that 15 percent of American counties generate 64 percent of America’s gross domestic product. Most of the country’s economic activity is on the East Coast, West Coast, and a few metropolitan areas in between. The prosperous parts of America include about 15 states having 30 senators while the less prosperous areas encapsulate 35 states having 70 senators.

Those numbers demonstrate the fundamental mismatch between economic vitality and political power. Through the Electoral College (and the U.S. Senate), the 35 states with smaller economic activity have disproportionate power to choose presidents and dictate public policy. This institutional relic from two centuries ago likely will fuel continued populism and regular discrepancies between the popular and Electoral College votes. Rather than being a historic aberration, presidents who lose the popular vote could become the norm and thereby usher in an anti-majoritarian era where small numbers of voters in a few states use their institutional clout in “left-behind” states to block legislation desired by large numbers of people.

Support for direct popular election

For years, a majority of Americans have opposed the Electoral College . For example, in 1967, 58 percent favored its abolition, while in 1981, 75 percent of Americans did so. More recent polling, however, has highlighted a dangerous development in public opinion. Americans by and large still want to do away with the Electoral College, but there now is a partisan divide in views, with Republicans favoring it while Democrats oppose it.

For instance, POLITICO and Morning Consult conducted a poll in March 2019 that found that 50 percent of respondents wanted a direct popular vote, 34 percent did not, and 16 percent did not demonstrate a preference. Two months later, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal reported polling that 53 percent of Americans wanted a direct popular vote, while 43 percent wanted to keep the status quo. These sentiments undoubtably have been reinforced by the fact that in two of the last five presidential elections, the candidate winning the popular vote lost the Electoral College.

Yet there are clear partisan divisions in these sentiments. In 2000, while the presidential election outcome was still being litigated, a Gallup survey reported that 73 percent of Democratic respondents supported a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College and move to direct popular voting, but only 46 percent of Republican respondents supported that view. This gap has since widened as after the 2016 election, 81 percent of Democrats and 19 percent of Republicans affirmatively answered the same question .

The March POLITICO and Morning Consult poll also found that 72 percent of Democratic respondents and 30 percent of Republican respondents endorsed a direct popular vote. Likewise, the NBC News and Wall Street Journal poll found that 78 percent of Hillary Clinton voters supported a national popular vote, while 74 percent of Trump voters preferred the Electoral College.

Ways to abolish the Electoral College

The U.S. Constitution created the Electoral College but did not spell out how the votes get awarded to presidential candidates. That vagueness has allowed some states such as Maine and Nebraska to reject “winner-take-all” at the state level and instead allocate votes at the congressional district level. However, the Constitution’s lack of specificity also presents the opportunity that states could allocate their Electoral College votes through some other means.

One such mechanism that a number of states already support is an interstate pact that honors the national popular vote. Since 2008, 15 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws to adopt the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), which is an multi-state agreement to commit electors to vote for candidates who win the nationwide popular vote, even if that candidate loses the popular vote within their state. The NPVIC would become effective only if states ratify it to reach an electoral majority of 270 votes.

Right now, the NPVIC is well short of that goal and would require an additional 74 electoral votes to take effect. It also faces some particular challenges. First, it is unclear how voters would respond if their state electors collectively vote against the popular vote of their state. Second, there are no binding legal repercussions if a state elector decides to defect from the national popular vote. Third, given the Tenth Circuit decision in the Baca v. Hickenlooper case described above, the NPVIC is almost certain to face constitutional challenges should it ever gain enough electoral votes to go into effect.

A more permanent solution would be to amend the Constitution itself. That is a laborious process and a constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College would require significant consensus—at least two-thirds affirmation from both the House and Senate, and approval from at least 38 out of 50 states. But Congress has nearly reached this threshold in the past. Congress nearly eradicated the Electoral College in 1934, falling just two Senate votes short of passage.

However, the conversation did not end after the unsuccessful vote, legislators have continued to debate ending or reforming the Electoral College since. In 1979, another Senate vote to establish a direct popular vote failed, this time by just three votes. Nonetheless, conversation continued: the 95th Congress proposed a total of 41 relevant amendments in 1977 and 1978, and the 116th Congress has already introduced three amendments to end the Electoral College. In total, over the last two centuries, there have been over 700 proposals to either eradicate or seriously modify the Electoral College. It is time to move ahead with abolishing the Electoral College before its clear failures undermine public confidence in American democracy, distort the popular will, and create a genuine constitutional crisis.

Related Content

Richard Lempert

November 29, 2016

Elaine Kamarck, John Hudak

December 9, 2020

Russell Wheeler

October 21, 2020

Related Books

Robert Kagan

April 30, 2024

Daniel S. Hamilton, Joe Renouard

April 1, 2024

Michael E. O’Hanlon

February 15, 2024

Campaigns & Elections

Katharine Meyer, Rachel M. Perera, Michael Hansen

April 9, 2024

Dominique J. Baker

Katharine Meyer

July 28, 2023

- University Navigation University Navigation

- Search Search Button

Gonzaga Home

- Student Life

College & Schools

- College of Arts & Sciences

- Center for Lifelong Learning

- Online Graduate Programs

- School of Business Administration

- School of Education

- School of Engineering & Applied Science

- School of Law

- School of Leadership Studies

- School of Health Sciences

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Military & Veterans

- Parents & Families

- Faculty & Staff

- Our Community

- Basketball Fans

- Search Button

- Toggle Menu

Collections

Publications, the electoral college: questions & answers.

Understanding the Electoral College as the 2020 Presidential Election approaches

What was the original purpose of the electoral college.

According to Joe Gardner , associate professor of political science at Gonzaga, the Electoral College was a political compromise between the Founders. They hoped this system would allow for “better” presidents by giving “more virtuous” men controlling authority in choosing a president. Ultimately, it was a result of lack of trust in the people. The College also intended to give greater independence to the executive branch. In slave states, this system was supported because it gave them an advantage in selecting presidents due to the 3/5 ths compromise. Otherwise, a large portion of their population wouldn’t be accounted for in a popular vote election.

How is the Electoral College designed to work?

Each state has as many “electors” in the Electoral College as it has representatives and senators in the U.S. Congress. When citizens vote for the presidential election, they are telling their states’ electors how to cast their ballots. After the popular vote of each state is certified, the winning slate of electors, chosen by each state’s political parties, meet to cast two ballots – one for vice president and one for president.

Why is there so much confusion around it?

People are confused about it, because, “It is confusing,” said Gardner.

He admits that even political scientists have trouble explaining it. The College never operated as an independent body, as the Founders intended, and was quickly encompassed by the states’ political party that passed legislation giving each states’ dominant party greater control over the selection of electors.

“There is a disconnect between how it might work on paper (in the Constitution) and how it operates in practice,” said Gardner.