Friday Essay: an introduction to Confucius, his ideas and their lasting relevance

Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies, The University of Western Australia

Disclosure statement

Yu Tao does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Western Australia provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

The man widely known in the English language as Confucius was born around 551 BCE in today’s southern Shandong Province. Confucius is the phonic translation of the Chinese word Kong fuzi 孔夫子, in which Kong 孔 was his surname and fuzi is an honorific for learned men.

Widely credited for creating the system of thought we now call Confucianism, this learned man insisted he was “not a maker but a transmitter”, merely “believing in and loving the ancients”. In this, Confucius could be seen as acting modestly and humbly, virtues he thought of highly.

Or, as Kang Youwei — a leading reformer in modern China has argued — Confucius tactically framed his revolutionary ideas as lost ancient virtues so his arguments would be met with fewer criticisms and less hostility.

Confucius looked nothing like the great sage in his own time as he is widely known in ours. To his contemporaries, he was perhaps foremost an unemployed political adviser who wandered around different fiefdoms for some years, attempting to sell his political ideas to different rulers — but never able to strike a deal.

It seems Confucius would have preferred to live half a millennium earlier, when China — according to him — was united under benevolent, competent and virtuous rulers at the dawn of the Zhou dynasty. By his own time, China had become a divided land with hundreds of small fiefdoms, often ruled by greedy, cruel or mediocre lords frequently at war.

But this frustrated scholar’s ideas have profoundly shaped politics and ethics in and beyond China ever since his death in 479 BCE. The greatest and the most influential Chinese thinker, his concept of filial piety, remains highly valued among young people in China , despite rapid changes in the country’s demography.

Despite some doubts as to whether many Chinese people take his ideas seriously, the ideas of Confucius remain directly and closely relevant to contemporary China.

This situation perhaps is comparable to Christianity in Australia. Although institutional participation is in constant decline, Christian values and narratives remain influential on Australian politics and vital social matters .

The danger today is in Confucianism being considered the single reason behind China’s success or failure. The British author Martin Jacques, for example, recently asserted Confucianism was the “biggest single reason” for East Asia’s success in the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, without giving any explanation or justification.

If Confucius were alive, he would probably not hesitate to call out this solitary root of triumph or disaster as being lazy, incorrect and unwise.

Political structure and mutual responsibilities

Confucius wanted to restore good political order by persuading rulers to reestablish moral standards, exemplify appropriate social relations, perform time-honoured rituals and provide social welfare.

He worked hard to promote his ideas but won few supporters. Almost every ruler saw punishment and military force as shortcuts to greater power.

It was not until 350 years later during the reign of the Emperor Wu of Han that Confucianism was installed as China’s state ideology.

But this state-sanctioned version of Confucianism was not an honest revitalisation of Confucius’ ideas. Instead, it absorbed many elements from rival schools of thought, notably legalism , which emerged in the latter half of China’s Warring States period (453–221 BCE). Legalism argued efficient governance relies on impersonal laws and regulations — rather than moral principles and rites.

Like most great thinkers of the Axial Age between the 8th and 3rd century BCE, Confucius did not believe everyone was created equal.

Similar to Plato (born over 100 years later), Confucius believed the ideal society followed a hierarchy. When asked by Duke Jing of Qi about government, Confucius famously replied:

let the ruler be a ruler; the minister, a minister; the father, a father; the son, a son.

However it would be a superficial reading of Confucius to believe he called for unconditional obedience to rulers or superiors. Confucius advised a disciple “not to deceive the ruler but to stand up to them”.

Confucius believed the legitimacy of a regime fundamentally relies on the confidence of the people. A ruler should tirelessly work hard and “lead by example”.

Like in a family, a good son listens to his father, and a good father wins respect not by imposing force or seniority but by offering heartfelt love, support, guidance and care.

In other words, Confucius saw a mutual relationship between the ruler and the ruled.

Love and respect for social harmony

To Confucius, the appropriate relations between family members are not merely metaphors for ideal political orders, but the basic fabrics of a harmonious society.

An essential family value in Confucius’ ideas is xiao 孝, or filial piety, a concept explained in at least 15 different ways in the Analects, a collection of the words from Confucius and his followers.

Read more: Can Ne Zha, the Chinese superhero with $1b at the box office, teach us how to raise good kids?

Depending on the context, Confucius defined filial piety as respecting parents, as “never diverging” from parents, as not letting parents feel unnecessary anxiety, as serving parents with etiquette when they are alive, and as burying and commemorating parents with propriety after they pass away.

Confucius expected rulers to exemplify good family values. When Ji Kang Zi, the powerful prime minister of Confucius’ home state of Lu asked for advice on keeping people loyal to the realm, Confucius responded by asking the ruler to demonstrate filial piety and benignity ( ci 慈).

Confucius viewed moral and ethical principles not merely as personal matters, but as social assets. He profoundly believed social harmony ultimately relies on virtuous citizens rather than sophisticated institutions.

In the ideas of Confucius, the most important moral principle is ren 仁, a concept that can hardly be translated into English without losing some of its meaning.

Like filial piety, ren is manifested in the love and respect one has for others. But ren is not restricted among family members and does not rely on blood or kinship. Ren guides people to follow their conscience. People with ren have strong compassion and empathy towards others.

Translators arguing for a single English equivalent for ren have attempted to interpret the concept as “benevolence”, “humanity”, “humanness” and “goodness”, none of which quite capture the full significance of the term.

The challenge in translating ren is not a linguistic one. Although the concept appears more than 100 times in the Analects, Confucius did not give one neat definition. Instead, he explained the term in many different ways.

As summarised by China historian Daniel Gardner , Confucius defined ren as:

to love others, to subdue the self and return to ritual propriety, to be respectful, tolerant, trustworthy, diligent, and kind, to be possessed of courage, to be free from worry, or to be resolute and firm.

Instead of searching for an explicit definition of ren , it is perhaps wise to view the concept as an ideal type of the highest and ultimate virtue Confucius believed good people should pursue.

Relevance in contemporary China

Confucius’ thinking hs had a profound impact on almost every great Chinese thinker since. Based upon his ideas, Mencius (372–289 BCE) and Xunzi (c310–c235 BCE) developed different schools of thought within the system of Confucianism.

Arguing against these ideas, Mohism (4th century BCE), Daoism (4th century BCE), Legalism (3rd century BCE) and many other influential systems of thought emerged in the 400 years after Confucius’ time, going on to shape many aspects of the Chinese civilisation in the last two millennia.

Modern China has a complicated relationship with Confucius and his ideas.

Since the early 20th century, many intellectuals influenced by western thought started denouncing Confucianism as the reason for China’s national humiliations since the first Opium War (1839-42).

Confucius received fierce criticism from both liberals and Marxists .

Hu Shih , a leader of China’s New Culture Movement in the 1910s and 1920s and an alumnus of Columbia University , advocated overthrowing the “House of Confucius”.

Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic of China, also repeatedly denounced Confucius and Confucianism. Between 1973 and 1975, Mao devoted the last political campaign in his life against Confucianism.

Read more: To make sense of modern China, you simply can't ignore Marxism

Despite these fierce criticisms and harsh persecutions, Confucius’ ideas remain in the minds and hearts of many Chinese people, both in and outside China.

One prominent example is PC Chang , another Chinese alumnus of Columbia University, who was instrumental in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights , proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on December 10 1948. Thanks to Chang’s efforts , the spirit of some most essential Confucian ideas, such as ren , was deeply embedded in the Declaration.

Today, many Chinese parents, as well as the Chinese state, are keen children be provided a more Confucian education .

In 2004, the Chinese government named its initiative of promoting language and culture overseas after Confucius, and its leadership has been enthusiastically embracing Confucius’ lessons to consolidate their legitimacy and ruling in the 21st century.

Read more: Explainer: what are Confucius Institutes and do they teach Chinese propaganda?

- Chinese history

- Friday essay

- Chinese politics

Lecturer in Indigenous Health (Identified)

Social Media Producer

Lecturer in Physiotherapy

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Confucianism.

Confucianism is one of the most influential religious philosophies in the history of China, and it has existed for over 2,500 years. It is concerned with inner virtue, morality, and respect for the community and its values.

Religion, Social Studies, Ancient Civilizations

Confucian Philosopher Mencius

Confucianism is an ancient Chinese belief system, which focuses on the importance of personal ethics and morality. Whether it is only or a philosophy or also a religion is debated.

Photograph by Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images, taken from Myths and Legends of China

Confucianism is a philosophy and belief system from ancient China, which laid the foundation for much of Chinese culture. Confucius was a philosopher and teacher who lived from 551 to 479 B.C.E. His thoughts on ethics , good behavior, and moral character were written down by his disciples in several books, the most important being the Lunyu . Confucianism believes in ancestor worship and human-centered virtues for living a peaceful life. The golden rule of Confucianism is “Do not do unto others what you would not want others to do unto you.” There is debate over if Confucianism is a religion. Confucianism is best understood as an ethical guide to life and living with strong character. Yet, Confucianism also began as a revival of an earlier religious tradition. There are no Confucian gods, and Confucius himself is worshipped as a spirit rather than a god. However, there are temples of Confucianism , which are places where important community and civic rituals happen. This debate remains unresolved and many people refer to Confucianism as both a religion and a philosophy. The main idea of Confucianism is the importance of having a good moral character, which can then affect the world around that person through the idea of “cosmic harmony.” If the emperor has moral perfection, his rule will be peaceful and benevolent. Natural disasters and conflict are the result of straying from the ancient teachings. This moral character is achieved through the virtue of ren, or “humanity,” which leads to more virtuous behaviours, such as respect, altruism , and humility. Confucius believed in the importance of education in order to create this virtuous character. He thought that people are essentially good yet may have strayed from the appropriate forms of conduct. Rituals in Confucianism were designed to bring about this respectful attitude and create a sense of community within a group. The idea of “ filial piety ,” or devotion to family, is key to Confucius thought. This devotion can take the form of ancestor worship, submission to parental authority, or the use of family metaphors, such as “son of heaven,” to describe the emperor and his government. The family was the most important group for Confucian ethics , and devotion to family could only strengthen the society surrounding it. While Confucius gave his name to Confucianism , he was not the first person to discuss many of the important concepts in Confucianism . Rather, he can be understood as someone concerned with the preservation of traditional Chinese knowledge from earlier thinkers. After Confucius’ death, several of his disciples compiled his wisdom and carried on his work. The most famous of these disciples were Mencius and Xunzi, both of whom developed Confucian thought further. Confucianism remains one of the most influential philosophies in China. During the Han Dynasty, emperor Wu Di (reigned 141–87 B.C.E.) made Confucianism the official state ideology. During this time, Confucius schools were established to teach Confucian ethics . Confucianism existed alongside Buddhism and Taoism for several centuries as one of the most important Chinese religions. In the Song Dynasty (960–1279 C.E.) the influence from Buddhism and Taoism brought about “Neo- Confucianism ,” which combined ideas from all three religions. However, in the Qing dynasty (1644–1912 C.E.), many scholars looked for a return to the older ideas of Confucianism , prompting a Confucian revival.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

March 6, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

At different times in Chinese history, Confucius (trad. 551–479 BCE) has been portrayed as a teacher, advisor, editor, philosopher, reformer, and prophet. The name Confucius, a Latinized combination of the surname Kong 孔 with an honorific suffix “Master” ( fuzi 夫子), has also come to be used as a global metonym for different aspects of traditional East Asian society. This association of Confucius with many of the foundational concepts and cultural practices in East Asia, and his casting as a progenitor of “Eastern” thought in Early Modern Europe, make him arguably the most significant thinker in East Asian history. Yet while early sources preserve biographical details about Master Kong, dialogues and stories about him in early texts like the Analects ( Lunyu 論語) reflect a diversity of representations and concerns, strands of which were later differentially selected and woven together by interpreters intent on appropriating or condemning particular associated views and traditions. This means that the philosophy of Confucius is historically underdetermined, and it is possible to trace multiple sets of coherent doctrines back to the early period, each grounded in different sets of classical sources and schools of interpretation linked to his name. After introducing key texts and interpreters, then, this entry explores three principal interconnected areas of concern: a psychology of ritual that describes how ideal social forms regulate individuals, an ethics rooted in the cultivation of a set of personal virtues, and a theory of society and politics based on normative views of the family and the state.

Each of these areas has unique features that were developed by later thinkers, some of whom have been identified as “Confucians”, even though that term is not well-defined. The Chinese term Ru (儒) predates Confucius, and connoted specialists in ritual and music, and later experts in Classical Studies. Ru is routinely translated into English as “Confucian”. Yet “Confucian” is also sometimes used in English to refer to the sage kings of antiquity who were credited with key cultural innovations by the Ru , to sacrificial practices at temples dedicated to Confucius and related figures, and to traditional features of East Asian social organization like the “bureaucracy” or “meritocracy”. For this reason, the term Confucian will be avoided in this entry, which will focus on the philosophical aspects of the thought of Confucius (the Latinization used for “Master Kong” following the English-language convention) primarily, but not exclusively, through the lens of the Analects .

1. Confucius as Chinese Philosopher and Symbol of Traditional Culture

2. sources for confucius’s life and thought, 3. ritual psychology and social values, 4. virtues and character formation, 5. the family and the state, other internet resources, related entries.

Because of the wide range of texts and traditions identified with him, choices about which version of Confucius is authoritative have changed over time, reflecting particular political and social priorities. The portrait of Confucius as philosopher is, in part, the product of a series of modern cross-cultural interactions. In Imperial China, Confucius was identified with interpretations of the classics and moral guidelines for administrators, and therefore also with training the scholar-officials that populated the bureaucracy. At the same time, he was closely associated with the transmission of the ancient sacrificial system, and he himself received ritual offerings in temples found in all major cities. By the Han (202 BCE–220 CE), Confucius was already an authoritative figure in a number of different cultural domains, and the early commentaries show that reading texts associated with him about history, ritual, and proper behavior was important to rulers. The first commentaries to the Analects were written by tutors to the crown prince (e.g., Zhang Yu 張禹, d. 5 BCE), and select experts in the “Five Classics” ( Wujing 五經) were given scholastic positions in the government. The authority of Confucius was such that during the late Han and the following period of disunity, his imprimatur was used to validate commentaries to the classics, encoded political prophecies, and esoteric doctrines.

By the Song period (960–1279), the post-Buddhist revival known as “Neo-Confucianism” anchored readings of the dialogues of Confucius to a dualism between “cosmic pattern” ( li 理) and “ pneumas ” ( qi 氣), a distinctive moral cosmology that marked the tradition off from those of Buddhism and Daoism. The Neo-Confucian interpretation of the Analects by Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200) integrated the study of the Analects into a curriculum based on the “Four Books” ( Sishu 四書) that became widely influential in China, Korea, and Japan. The pre-modern Confucius was closely associated with good government, moral education, proper ritual performance, and the reciprocal obligations that people in different roles owed each other in such contexts.

When Confucius became a character in the intellectual debates of eighteenth century Europe, he became identified as China’s first philosopher. Jesuit missionaries in China sent back accounts of ancient China that portrayed Confucius as inspired by Natural Theology to pursue the good, which they considered a marked contrast with the “idolatries” of Buddhism and Daoism. Back in Europe, intellectuals read missionary descriptions and translations of Chinese literature, and writers like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) and Nicolas-Gabriel Clerc (1726–1798) praised Confucius for his discovery of universal natural laws through reason. Enlightenment writers celebrated the moral philosophy of Confucius for its independence from the dogmatic influence of the Church. While at times he was criticized as an atheist or an advocate of despotism, many Europeans viewed Confucius as a moral philosopher whose approach was in line with rationalism and humanism.

Today, many descriptions combine these several ways of positioning Confucius, but the modern interpretation of his views has been complicated by a tendency to look back on him as an emblem of the “traditional culture” of China. In the eyes of some late nineteenth and twentieth century reformers who sought to fortify China against foreign influence, the moral teachings of Confucius had the potential to play the same role that they perceived Christianity had done in the modernization of Europe and America, or serve as the basis of a more secular spiritual renewal that would transform the population into citizens of a modern nation-state. In the twentieth century, the pursuit of modernization also led to the rejection of Confucius by some reformers in the May Fourth and New Culture movements, as well as by many in the Communist Party, who identified the traditional hierarchies implicit in his social and political philosophy with the social and economic inequalities that they sought to eliminate. In these modern debates, it is not just the status of Confucius in traditional China that made him such a potent symbol. His specific association with the curriculum of the system of education of scholar-officials in the imperial government, and of traditional moral values more generally, connected him to the aspects of tradition worth preserving, or the things that held China back from modernization, depending on one’s point of view.

As legacies of Confucius tied to traditional ritual roles and the pre-modern social structure were criticized by modernizers, a view of Confucius as a moral philosopher, already common in European readings, gained ascendancy in East Asia. The American-educated historian Hu Shi 胡適 (1891–1962) wrote an early influential history of Chinese philosophy, beginning with Laozi 老子 and Confucius, explicitly on the model of existing histories of Western philosophy. In it, Hu compared what he called the conservative aspect of the philosophy of Confucius to Socrates and Plato. Since at least that time, Confucius has been central to most histories of Chinese philosophy.

Biographical treatments of Confucius, beginning with the “Hereditary House of Confucius” ( Kongzi shijia 孔子世家), a chapter of Sima Qian’s 司馬遷 (c.145–c.86 BCE) Records of the Grand Historian ( Shiji 史記), were initially based on information from compilations of independently circulating dialogues and prose accounts. Tying particular elements of his philosophy to the life experiences of Confucius is a risky and potentially circular exercise, since many of the details of his biography were first recorded in instructive anecdotes linked to the expression of didactic messages. Nevertheless, since Sima Qian’s time, the biography of Confucius has been intimately linked with the interpretation of his philosophy, and so this section begins with a brief treatment of traditional tropes about his family background, official career, and teaching of 72 disciples, before turning to the dialogue and prose accounts upon which early biographers like Sima Qian drew.

Confucius was born in the domain of Zou, in modern Shandong Province, south of the larger kingdom of Lu. A date of 551 BCE is given for his birth in the Gongyang Commentary ( Gongyang zhuan 公羊傳) to the classic Spring and Autumn Annals ( Chunqiu 春秋), which places him in the period when the influence of the Zhou polity was declining, and regional domains were becoming independent states. His father, who came from Lu, was descended from a noble clan that included, in Sima Qian’s telling, several people known for their modesty and ritual mastery. His father died when Confucius was a small child, leaving the family poor but with some social status, and as a young man Confucius became known for expertise in the classical ritual and ceremonial forms of the Zhou. In adulthood, Confucius travelled to Lu and began a career as an official in the employ of aristocratic families.

Different sources identify Confucius as having held a large number of different offices in Lu. Entries in the Zuo Commentary ( Zuozhuan 左傳) to the Spring and Autumn Annals for 509 and 500 BCE identify him as Director of Corrections ( Sikou 司寇), and say he was charged with assisting the ruler with the rituals surrounding a visiting dignitary from the state of Qi, respectively. The Mencius ( Mengzi 孟子), a text centered on a figure generally regarded as the most important early developer of the thought of Confucius, Mencius (trad. 372–289 BCE), says Confucius was Foodstuffs Scribe ( Weili 委吏) and Scribe in the Field ( Chengtian 乘田), involved with managing the accounting at the granary and keeping the books on the pasturing of different animals (11.14). [ 1 ] In the first biography, Sima Qian mentions these offices, but then adds a second set of more powerful positions in Lu including Steward ( Zai 宰) managing an estate in the district of Zhongdu, Minister of Works ( Sikong 司空), and even acting Chancellor ( Xiang 相). Following his departure from Lu, different stories place Confucius in the kingdoms of Wei, Song, Chen, Cai, and Chu. Sima Qian crafted these stories into a serial narrative of rulers failing to appreciate the moral worth of Confucius, whose high standards forced him to continue to travel in search of an incorrupt ruler.

Late in life, Confucius left service and turned to teaching. In Sima Qian’s time, the sheer number of independently circulating texts centering on dialogues that Confucius had with his disciples led the biographer to include a separate chapter on “The arranged traditions of the disciples of Confucius” ( Zhong Ni dizi liezhuan 仲尼弟子列傳). His account identifies 77 direct disciples, whom Sima Qian says Confucius trained in ritual practice and the Classic of Odes ( Shijing 詩經), Classic of Documents ( Shujing 書經, also called Documents of the Predecessors or Shangshu 尚書), Records of Ritual ( Liji 禮記) and Classic of Music ( Yuejing 樂經). Altogether, some 3000 students received some form of this training regimen. Sima Qian’s editorial practice in systematizing dialogues was inclusive, and the fact that he was able to collect so much information some three centuries after the death of Confucius testifies to the latter’s importance in the Han period. Looked at in a different way, the prodigious numbers of direct disciples and students of Confucius, and the inconsistent accounts of the offices in which he served, may also be due to a proliferation of texts associating the increasingly authoritative figure of Confucius with divergent regional or interpretive traditions during those intervening centuries.

The many sources of quotations and dialogues of Confucius, both transmitted and recently excavated, provide a wealth of materials about the philosophy of Confucius, but an incomplete sense of which materials are authoritative. The last millennium has seen the development of a conventional view that materials preserved in the twenty chapters of the transmitted Analects most accurately represent Confucius’s original teachings. This derives in part from a second century CE account by Ban Gu 班固 (39–92 CE) of the composition of the Analects that describes the work as having been compiled by first and second generation disciples of Confucius and then transmitted privately for centuries, making it arguably the oldest stratum of extant Confucius sources. In the centuries since, some scholars have come up with variations on this basic account, such as Liu Baonan’s 劉寳楠 (1791–1855) view in Corrected Meanings of the Analects ( Lunyu zhengyi 論語正義) that each chapter was written by a different disciple. Recently, several centuries of doubts about internal inconsistencies in the text and a lack of references to the title in early sources were marshaled by classicist Zhu Weizheng 朱維錚 in an influential 1986 article which argued that the lack of attributed quotations from the Analects , and of explicit references to it, prior to the second century BCE, meant that its traditional status as the oldest stratum of the teachings of Confucius was undeserved. Since then a number of historians, including Michael J. Hunter, have systematically shown that writers started to demonstrate an acute interest in the Analects only in the late second and first centuries BCE, suggesting that other Confucius-related records from those centuries should also be considered as potentially authoritative sources. Some have suggested this critical approach to sources is an attack on the historicity of Confucius, but a more reasonable description is that it is an attack on the authoritativeness of the Analects that broadens and diversifies the sources that may be used to reconstruct the historical Confucius.

Expanding the corpus of Confucius quotations and dialogues beyond the Analects , then, requires attention to three additional types of sources. First, dialogues preserved in transmitted sources like the Records of Ritual, the Elder Dai’s Records of Ritual ( DaDai Liji 大戴禮記), and Han collections like the Family Discussions of Confucius ( Kongzi jiayu 孔子家語) contain a large number of diverse teachings. Second, quotations attached to the interpretation of passages in the classics preserved in works like the Zuo Commentary to the Spring and Autumn Annals , or Han’s Intertextual Commentary on the Odes ( Han Shi waizhuan 韓詩外傳) are particularly rich sources for readings of history and poetry. Finally, a number of recently archaeologically recovered texts from the Han period and before have also expanded the corpus.

Newly discovered sources include three recently excavated versions of texts with parallel to the transmitted Analects . These are the 1973 excavation at the Dingzhou site in Hebei Province dating to 55 BCE; the 1990’s excavation of a partial parallel version at Jongbaekdong in Pyongyang, North Korea, dating to between 62 and 45 BCE; and most recently the 2011–2015 excavation of the tomb of the Marquis of Haihun in Jiangxi Province dating to 59 BCE. The Haihun excavation is particularly important because it is thought to contain the two lost chapters of what Han period sources identify as a 22-chapter version of the Analects that circulated in the state of Qi, the titles of which appear to be “Understanding the Way” ( Zhi dao 智道) and “Questions about Jade” ( Wen yu 問玉). While the Haihun Analects has yet to be published, the content of the lost chapters overlaps with a handful of fragments dating to the late first century BCE that were found at the Jianshui Jinguan site in Jinta county in Gansu Province in 1973. All in all, these finds confirm the sudden wide circulation of the Analects in the middle of the first century BCE.

Previously unknown Confucius dialogues and quotations have also been unearthed. The Dingzhou site also yielded texts given the titles “Sayings of the Ru” ( Rujiazhe yan 儒家者言) and “Duke Ai asked about the five kinds of righteousness” ( Aigong wen wuyi 哀公問五義). A significantly different text also given the name “Sayings of the Ru” was found in 1977 in a Han tomb at Fuyang in Anhui Province. Several texts dating to 168 BCE recording statements by Confucius about the Classic of Changes ( Yijing 易經) were excavated from the Mawangdui site in Hunan Province in 1973. Additionally, a number of Warring States period dialogical texts centered on particular disciples, and a text with interpretative comments by Confucius on the Classic of Poetry given the name “Confucius discusses the Odes ” ( Kongzi shilun 孔子詩論), were looted from tombs in the 1990s, sold on the black market, and made their way to the Shanghai Museum. The 59 BCE tomb of the Marquis of Haihun also contains a number of previously unknown Confucius dialogues and quotations on ritual and filial piety, along with materials that overlap with sections of transmitted texts including the Analects , Records of Ritual and the Elder Dai’s Records of Ritual . Another unprovenanced manuscript, now curated by Anhui University, “Zhong Ni said” ( Zhong Ni yue 仲尼曰) has around two dozen sayings, seven of which overlap with the modern Analects . Most recently, initial reports about a 2021 excavation at Wangjiazui 王家嘴 in Hubei province of an unknown number of sayings entitled “Kongzi said,” ( Kongzi yue 孔子曰) indicate it only partially overlaps with the Analects . These new finds suggest that a larger number of sayings attributed to Kongzi once circulated together, with certain ones being selected out for inclusion in works like the Records of Ritual and the Analects .

Some excavated texts, like the pre-Han period “Thicket of Sayings” ( Yucong 語叢) apothegms excavated at the Guodian site in Hubei Province in 1993, contain fragments of the Analects in circulation without attribution to Confucius. Transmitted materials also show some of the quotations attributed to Confucius in the Analects in the mouths of other historical figures. The fluidity and diversity of Confucius-related materials in circulation prior to the fixing of the Analects text in the second century BCE, suggest that the Analects itself, with its keen interest in ritual, personal ethics, and politics, may well have been in part a topical selection from a larger and more diverse set of available Confucius-related materials. In other words, there were already multiple topical foci prior to any horizon by which we can definitively deem any single focus to be authoritative. It is for this reason that the essential core of the teachings of Confucius is historically underdetermined, and the correct identification of the core teachings is still avidly debated. The following sections treat three key aspects of the philosophy of Confucius, each different but all interrelated, found throughout many of these diverse sets of sources: a theory of how ritual and musical performance functioned to promote unselfishness and train emotions, advice on how to inculcate a set of personal virtues to prepare people to behave morally in different domains of their lives, and a social and political philosophy that abstracted classical ideals of proper conduct in family and official contexts to apply to more general contexts.

The Records of Ritual , the Analects , and numerous Han collections portray Confucius as being deeply concerned with the proper performance of ritual and music. In such works, the description of the attitudes and affect of the performer became the foundation of a ritual psychology in which proper performance was key to reforming desires and beginning to develop moral dispositions. Confucius sought to preserve the Zhou ritual system, and theorized about how ritual and music inculcated social roles, limited desires and transformed character.

Many biographies begin their description of his life with a story of Confucius at an early age performing rituals, reflecting accounts and statements that demonstrate his prodigious mastery of ritual and music. The archaeological record shows that one legacy of the Zhou period into which Confucius was born was a system of sumptuary regulations that encoded social status. Another of these legacies was ancestral sacrifice, a means to demonstrate people’s reverence for their ancestors while also providing a way to ask the spirits to assist them or to guarantee them protection from harm. The Analects describes the ritual mastery of Confucius in receiving guests at a noble’s home (10.3), and in carrying out sacrifices (10.8, 15.1). He plays the stone chimes (14.39), distinguishes between proper and improper music (15.11, 17.18), and extols and explains the Classic of Odes to his disciples (1.15, 2.2, 8.3, 16.13, 17.9). This mastery of classical ritual and musical forms is an important reason Confucius said he “followed Zhou” (3.14). While he might alter a detail of a ritual out of frugality (9.3), Confucius insists on adherence to the letter of the rites, as when his disciple Zi Gong 子貢 sought to substitute another animal for a sheep in a seasonal sacrifice, saying “though you care about the sheep, I care about the ritual” (3.17). It was in large part this adherence to Zhou period cultural forms, or to what Confucius reconstructed them to be, that has led many in the modern period to label him a traditionalist.

Where Confucius clearly innovated was in his rationale for performing the rites and music. Historian Yan Buke 閻步克 has argued that the early Confucian ( Ru ) tradition began from the office of the “Music master” ( Yueshi 樂師) described in the Ritual of Zhou ( Zhou Li 周禮). Yan’s view is that since these officials were responsible for teaching the rites, music, and the Classic of Odes , it was their combined expertise that developed into the particular vocation that shaped the outlook of Confucius. Early discussions of ritual in the Zhou classics often explained ritual in terms of a do ut des view of making offerings to receive benefits. By contrast, early discussions between Confucius and his disciples described benefits of ritual performance that went beyond the propitiation of spirits, rewards from the ancestors, or the maintenance of the social or cosmic order. Instead of emphasizing goods that were external to the performer, these works stressed the value of the associated interior psychological states of the practitioner. In Analects 3.26, Confucius condemns the performance of ritual without reverence ( jing 敬). He also condemns views of ritual that focus only on the offerings, or views of music that focus only on the instruments (17.11). Passages from the Records of Ritual explain that Confucius would rather have an excess of reverence than an excess of ritual (“ Tangong, shang ” 檀弓上), and that reverence is the most important aspect of mourning rites (“ Zaji, xia ” 雜記下). This emphasis on the importance of an attitude of reverence became the salient distinction between performing ritual in a rote manner, and performing it in the proper affective state. Another passage from the Records of Ritual says the difference between how an ideal gentleman and a lesser person cares for a parent is that the gentleman is reverent when he does it (“ Fangji ” 坊記, cf. Analects 2.7). In contexts concerning both ritual and filial piety ( xiao 孝), the affective state behind the action is arguably more important than the action’s consequences. As Philip J. Ivanhoe has written, ritual and music are not just an indicator of values in the sense that these examples show, but also an inculcator of them.

In this ritual psychology, the performance of ritual and music restricts desires because it alters the performer’s affective states, and place limits on appetitive desires. The Records of Ritual illustrates desirable affective states, describing how the Zhou founder King Wen 文 was moved to joy when making offerings to his deceased parents, but then to grief once the ritual ended (“ Jiyi ” 祭義). A collection associated with the third century BCE philosopher Xunzi 荀子 contains a Confucius quotation that associates different parts of a ruler’s day with particular emotions. Entering the ancestral temple to make offerings and maintain a connection to those who are no longer living leads the ruler to reflect on sorrow, while wearing a cap to hear legal cases leads him to reflect on worry (“ Aigong ” 哀公). These are examples of the way that ritual fosters the development of particular emotional responses, part of a sophisticated understanding of affective states and the ways that performance channels them in particular directions. More generally, the social conventions implicit in ritual hierarchies restrict people’s latitude to pursue their desires, as the master explains in the Records of Ritual:

The way of the gentleman may be compared to an embankment dam, bolstering those areas where ordinary people are deficient (“ Fangji ”).

Blocking the overflow of desires by adhering to these social norms preserves psychological space to reflect and reform one’s reactions.

Descriptions of the early community depict Confucius creating a subculture in which ritual provided an alternate source of value, effectively training his disciples to opt out of conventional modes of exchange. In the Analects , when Confucius says he would instruct any person who presented him with “a bundle of dried meat” (7.7), he is highlighting how his standards of value derive from the sacrificial system, eschewing currency or luxury items. Gifts valuable in ordinary situations might be worth little by such standards: “Even if a friend gave him a gift of a carriage and horses, if it was not dried meat, he did not bow” (10.15). The Han period biographical materials in Records of the Historian describe how a high official of the state of Lu did not come to court for three days after the state of Qi made him a gift of female entertainers. When, additionally, the high official failed to properly offer gifts of sacrificial meats, Confucius departed Lu for the state of Wei (47, cf. Analects 18.4). Confucius repeatedly rejected conventional values of wealth and position, choosing instead to rely on ritual standards of value. In some ways, these stories are similar to ones in the late Warring States and Han period compilation Master Zhuang ( Zhuangzi 莊子) that explore the way that things that are conventionally belittled for their lack of utility are useful by an unconventional standard. However, here the standard that gives such objects currency is ritual importance rather than longevity, divorcing Confucius from conventional materialistic or hedonistic pursuits. This is a second way that ritual allows one to direct more effort into character formation.

Once, when speaking of cultivating benevolence, Confucius explained how ritual value was connected to the ideal way of the gentleman, which should always take precedence over the pursuit of conventional values:

Wealth and high social status are what others covet. If I cannot prosper by following the way, I will not dwell in them. Poverty and low social status are what others shun. If I cannot prosper by following the way, I will not avoid them. (4.5)

The argument that ritual performance has internal benefits underlies the ritual psychology laid out by Confucius, one that explains how performing ritual and music controls desires and sets the stage for further moral development.

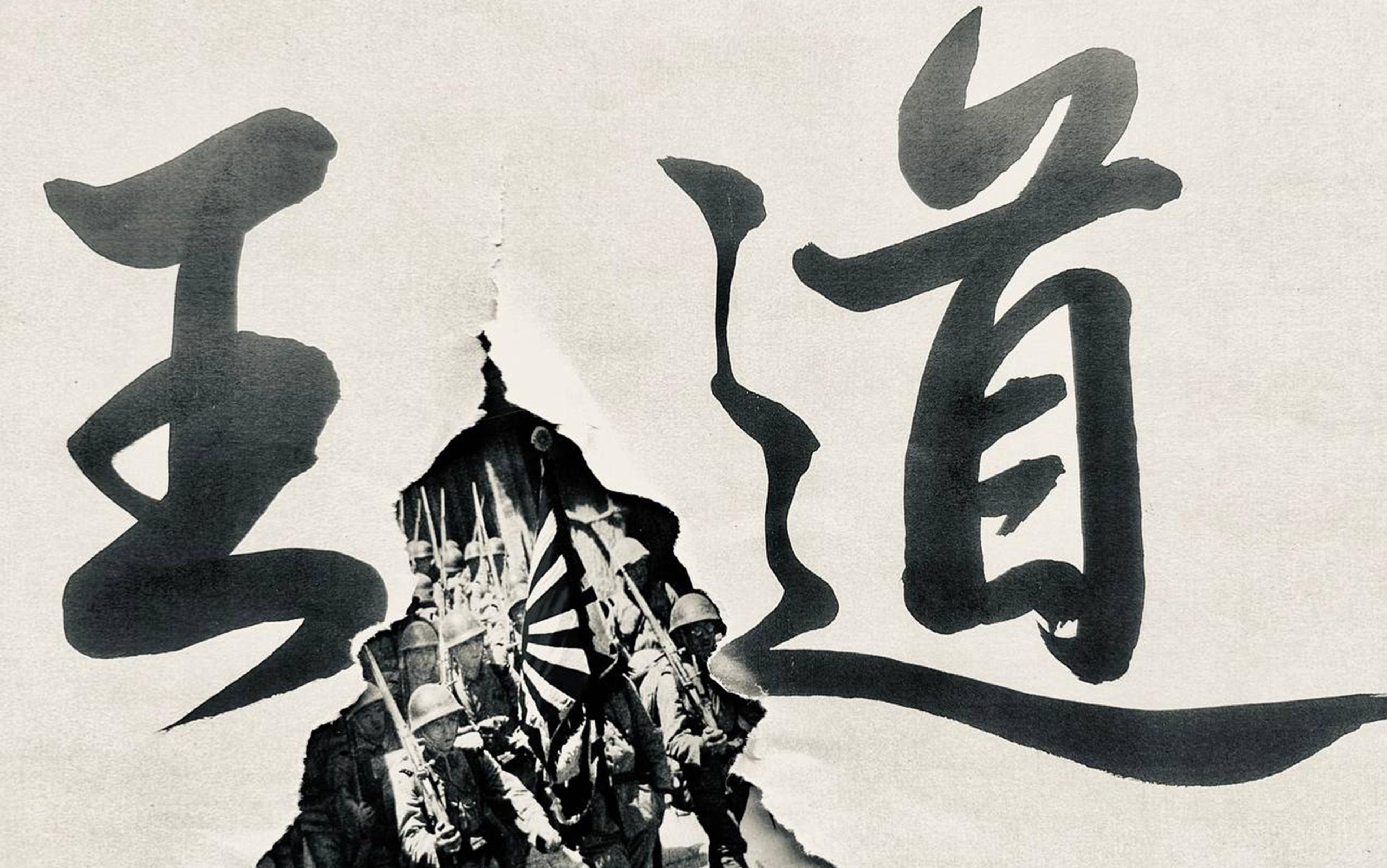

Many of the short passages from the Analects , and the “Thicket of Sayings” passages excavated at Guodian, describe the development of set of ideal behaviors associated with the moral ideal of the “way” ( dao 道) of the “gentleman” ( junzi 君子). Based on the analogy between the way of Confucius and character ethics systems deriving from Aristotle, these patterns of behavior are today often described using the Latinate term “virtue”. In the second passage in the Analects , the disciple You Ruo 有若 says a person who behaves with filial piety to parents and siblings ( xiao and di 弟), and who avoids going against superiors, will rarely disorder society. It relates this correlation to a more general picture of how patterns of good behavior effectively open up the possibility of following the way of the gentleman: “The gentleman works at the roots. Once the roots are established, the way comes to life” (1.2). The way of the gentleman is a distillation of the exemplary behaviors of the selfless culture heroes of the past, and is available to all who are willing to “work at the roots”. In this way, the virtues that Confucius taught were not original to him, but represented his adaptations of existing cultural ideals, to which he continually returned in order to clarify their proper expressions in different situations. Five behaviors of the gentleman most central to the Analects are benevolence ( ren 仁), righteousness ( yi 義), ritual propriety ( li 禮), wisdom ( zhi 智), and trustworthiness ( xin 信).

The virtue of benevolence entails interacting with others guided by a sense of what is good from their perspectives. Sometimes the Analects defines benevolence generally as “caring for others” (12.22), but in certain contexts it is associated with more specific behaviors. Examples of contextual definitions of benevolence include treating people on the street as important guests and common people as if they were attendants at a sacrifice (12.2), being reticent in speaking (12.3) and rejecting the use of clever speech (1.3), and being respectful where one dwells, reverent where one works, and loyal where one deals with others (13.19). It is the broadest of the virtues, yet a gentleman would rather die than compromise it (15.9). Benevolence entails a kind of unselfishness, or, as David Hall and Roger Ames suggest, it involves forming moral judgments from a combined perspective of self and others.

Later writers developed accounts of the sources of benevolent behavior, most famously in the context of the discussion of human nature ( xing 性) in the centuries after Confucius. Mencius (fourth century BCE) argued that benevolence grows out of the cultivation of an affective disposition to compassion ( ceyin 惻隱) in the face of another’s distress. The anonymous author of the late Warring States period excavated text “Five Kinds of Action” ( Wu xing 五行) describes it as building from the affection one feels for close family members, through successive stages to finally develop into a more universal, fully-fledged virtue. In the Analects , however, one comment on human nature emphasizes the importance of nurture: “By nature people are close, by habituation they are miles apart” (17.2), a sentiment that suggests the importance of training one’s dispositions through ritual and the classics in a manner closer to the program of Xunzi (third century BCE). The Analects , however, discusses the incubation of benevolent behavior in family and ritual contexts. You Ruo winds up his discussion of the roots of the way of the gentleman with the rhetorical question: “Is not behaving with filial piety to one’s parents and siblings the root of benevolence?” (1.2). Confucius tells his disciple Yan Yuan 顏淵 that benevolence is a matter of “overcoming oneself and returning to ritual propriety” (12.1). These connections between benevolence and other virtues underscore the way in which benevolent behavior does not entail creating novel social forms or relationships, but is grounded in traditional familial and ritual networks.

The second virtue, righteousness, is often described in the Analects relative to situations involving public responsibility. In contexts where standards of fairness and integrity are valuable, such as acting as the steward of an estate as some of the disciples of Confucius did, righteousness is what keeps a person uncorrupted. Confucius wrote that a gentleman “thinks of righteousness when faced with gain” (16.10, 19.10), or “when faced with profit” (14.12). Confucius says that one should ignore the wealth and rank one might attain by acting against righteousness, even if it means eating coarse rice, drinking water, and sleeping using one’s bent arm as a pillow (7.16). Later writers like Xunzi celebrated Confucius for his righteousness in office, which he stressed was all the more impressive because Confucius was extremely poor (“ Wangba ” 王霸). This behavior is particularly relevant in official interactions with ordinary people, such as when “employing common people” (5.16), and if a social superior has mastered it, “the common people will all comply” (13.4). Like benevolence, righteousness also entails unselfishness, but instead of coming out of consideration for the needs of others, it is rooted in steadfastness in the face of temptation.

The perspective needed to act in a righteous way is sometimes related to an attitude to personal profit that recalls the previous section’s discussion of how Confucius taught his disciples to recalibrate their sense of value based on their immersion in the sacrificial system. More specifically, evaluating things based on their ritual significance can put one at odds with conventional hierarchies of value. This is defined as the root of righteous behavior in a story from the late Warring States period text Master Fei of Han ( Han Feizi 韓非子). The tale relates how at court, Confucius was given a plate with a peach and a pile of millet grains with which to scrub the fruit clean. After the attendants laughed at Confucius for proceeding to eat the millet first, Confucius explained to them that in sacrifices to the Former Kings, millet itself is the most valued offering. Therefore, cleaning a ritually base peach with millet:

would be obstructing righteousness, and so I dared not put [the peach] above what fills the vessels in the ancestral shrine. (“ Waichu shuo, zuo shang ” 外儲說左上)

While such stories may have been told to mock his fastidiousness, for Confucius the essence of righteousness was internalizing a system of value that he would breach for neither convenience nor profit.

At times, the phrase “benevolence and righteousness” is used metonymically for all the virtues, but in some later texts, a benevolent impulse to compassion and a righteous steadfastness are seen as potentially contradictory. In the Analects , portrayals of Confucius do not recognize a tension between benevolence and righteousness, perhaps because each is usually described as salient in a different set of contexts. In ritual contexts like courts or shrines, one ideally acts like one might act out of familial affection in a personal context, the paradigm that is key to benevolence. In the performance of official duties, one ideally acts out of the responsibilities felt to inferiors and superiors, with a resistance to temptation by corrupt gain that is key to righteousness. The Records of Ritual distinguishes between the domains of these two virtues:

In regulating one’s household, kindness overrules righteousness. Outside of one’s house, righteousness cuts off kindness. What one undertakes in serving one’s father, one also does in serving one’s lord, because one’s reverence for both is the same. Treating nobility in a noble way and the honorable in an honorable way, is the height of righteousness. (“ Sangfu sizhi ” 喪服四制)

While it is not the case that righteousness is benevolence by other means, this passage underlines how in different contexts, different virtues may push people toward participation in particular shared cultural practices constitutive of the good life.

While the virtues of benevolence and righteousness might impel a gentleman to adhere to ritual norms in particular situations or areas of life, a third virtue of “ritual propriety” expresses a sensitivity to one’s social place, and willingness to play all of one’s multiple ritual roles. The term li translated here as “ritual propriety” has a particularly wide range of connotations, and additionally connotes both the conventions of ritual and etiquette. In the Analects, Confucius is depicted both teaching and conducting the rites in the manner that he believed they were conducted in antiquity. Detailed restrictions such as “the gentleman avoids wearing garments with red-black trim” (10.6), which the poet Ezra Pound disparaged as “verses re: length of the night-gown and the predilection for ginger” (Pound 1951: 191), were by no means trivial to Confucius. His imperative, “Do not look or listen, speak or move, unless it is in accordance with the rites” (12.1), in answer to a question about benevolence, illustrates how the symbolic conventions of the ritual system played a role in the cultivation of the virtues. We have seen how ritual shapes values by restricting desires, thereby allowing reflection and the cultivation of moral dispositions. Yet without the proper affective state, a person is not properly performing ritual. In the Analects , Confucius says he cannot tolerate “ritual without reverence, or mourning without grief,” (3.26). When asked about the root of ritual propriety, he says that in funerals, the mourners’ distress is more important than the formalities (3.4). Knowing the details of ritual protocols is important, but is not a substitute for sincere affect in performing them. Together, they are necessary conditions for the gentleman’s training, and are also essential to understanding the social context in which Confucius taught his disciples.

The mastery that “ritual propriety” signaled was part of a curriculum associated with the training of rulers and officials, and proper ritual performance at court could also serve as a kind of political legitimation. Confucius summarized the different prongs of the education in ritual and music involved in the training of his followers:

Raise yourself up with the Classic of Odes . Establish yourself with ritual. Complete yourself with music. (8.8)

On one occasion, Boyu 伯魚, the son of Confucius, explained that when he asked his father to teach him, his father told him to study the Classic of Odes in order to have a means to speak with others, and to study ritual to establish himself (16.13). That Confucius insists that his son master classical literature and practices underscores the values of these cultural products as a means of transmitting the way from one generation to the next. He tells his disciples that the study of the Classic of Odes prepares them for different aspects of life, providing them with a capacity to:

at home serve one’s father, away from it serve one’s lord, as well as increase one’s knowledge of the names of birds, animals, plants and trees. (17.9)

This valuation of knowledge of both the cultural and natural worlds is one reason why the figure of Confucius has traditionally been identified with schooling, and why today his birthday is celebrated as “Teacher’s Day” in some parts of Asia. In the ancient world, this kind of education also qualified Confucius and his disciples for employment on estates and at courts.

The fourth virtue, wisdom, is related to appraising people and situations. In the Analects, wisdom allows a gentleman to discern crooked and straight behavior in others (12.22), and discriminate between those who may be reformed and those who may not (15.8). In the former dialogue, Confucius explains the virtue of wisdom as “knowing others”. The “Thicket of Sayings” excavated at Guodian indicates that this knowledge is the basis for properly “selecting” others, defining wisdom as the virtue that is the basis for selection. But it is also about appraising situations correctly, as suggested by the master’s rhetorical question: “How can a person be considered wise if that person does not dwell in benevolence?” (4.1). One well-known passage often cited to imply Confucius is agnostic about the world of the spirits is more literally about how wisdom allows an outsider to present himself in a way appropriate to the people on whose behalf he is working:

When working for what is right for the common people, to show reverence for the ghosts and spirits while maintaining one’s distance may be deemed wisdom. (6.22)

The context for this sort of appraisal is usually official service, and wisdom is often attributed to valued ministers or advisors to sage rulers.

In certain dialogues, wisdom also connotes a moral discernment that allows the gentleman to be confident of the appropriateness of good actions. In the Analects , Confucius tells his disciple Zi Lu 子路 that wisdom recognizes knowing a thing as knowing it, and ignorance of a thing as ignorance of it (2.17). In soliloquies about several virtues, Confucius describes a wise person as never confused (9.28, 14.28). While comparative philosophers have noted that Chinese thought has nothing clearly analogous to the role of the will in pre-modern European philosophy, the moral discernment that is part of wisdom does provide actors with confidence that the moral actions they have taken are correct.

The virtue of trustworthiness qualifies a gentleman to give advice to a ruler, and a ruler or official to manage others. In the Analects , Confucius explains it succinctly: “if one is trustworthy, others will give one responsibilities” (17.6, cf. 20.1). While trustworthiness may be rooted in the proper expression of friendship between those of the same status (1.4, 5.26), it is also valuable in interactions with those of different status. The disciple Zi Xia 子夏 explains its effect on superiors and subordinates: when advising a ruler, without trustworthiness, the ruler will think a gentleman is engaged in slander, and when administering a state, without trustworthiness, people will think a gentleman is exploiting them (19.10). The implication is that a sincerely public-minded official would be ineffective without the trust that this quality inspires. In a dialogue with a ruler from chapter four of Han’s Intertextual Commentary the Odes , Confucius explains that in employing someone, trustworthiness is superior to strength, ability to flatter, or eloquence. Being able to rely on someone is so important to Confucius that, when asked about good government, he explained that trustworthiness was superior to either food or weapons, concluding: “If the people do not find the ruler trustworthy, the state will not stand” (12.7).

By the Han period, benevolence, righteousness, ritual propriety, wisdom and trustworthiness began to be considered as a complete set of human virtues, corresponding with other quintets of phenomena used to describe the natural world. Some texts described a level of moral perfection, as with the sages of antiquity, as unifying all these virtues. Prior to this, it is unclear whether the possession of a particular virtue entailed having all the others, although benevolence was sometimes used as a more general term for a combination of one or more of the other virtues (e.g., Analects 17.6). At other times, Confucius presented individual virtues as expressions of goodness in particular domains of life. Early Confucius dialogues are embedded in concrete situations, and so resist attempts to distill them into more abstract principles of morality. As a result, descriptions of the virtues are embedded in anecdotes about the exemplary individuals whose character traits the dialogues encourage their audience to develop. Confucius taught that the measure of a good action was whether it was an expression of the actor’s virtue, something his lessons share with those of philosophies like Aristotle’s that are generally described as “virtue ethics”. A modern evaluation of the teachings of Confucius as a “virtue ethics” is articulated in Bryan W. Van Norden’s Virtue Ethics and Consequentialism in Early Chinese Philosophy , which pays particular attention to analogies between the way of Confucius and Aristotle’s “good life”. The nature of the available source materials about Confucius, however, means that the diverse texts from early China lack the systematization of a work like Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics .

The five virtues described above are not the only ones of which Confucius spoke. He discussed loyalty ( zhong 忠), which at one point is described as the minister’s behavior toward a ritually proper ruler (3.19). He said that courage ( yong 勇) is what compels one to act once one has seen where righteousness lies (2.24). Another term sometimes translated as “virtue” ( de 德), is usually used to describe the authority of a ruler that grows out of goodness or favor to others, and is a key term in many of the social and political works discussed in the following section. Yet going through a list of all the virtues in the early sources is not sufficient to describe the entirety of the moral universe associated with Confucius.

The presence of themes in the Analects like the ruler’s exceptional influence as a moral exemplar, the importance of judging people by their deeds rather than their words (1.3, 2.10, 5.10), or even the protection of the culture of Zhou by higher powers (9.5), all highlight the unsystematic nature of the text and underscore that teaching others how to cultivate the virtues is a key aspect, but only a part, of the ethical ideal of Confucius. Yet there is also a conundrum inherent in any attempt to derive abstract moral rules from the mostly dialogical form of the Analects , that is, the problem of whether the situational context and conversation partner is integral to evaluating the statements of Confucius. A historically notable example of an attempt to find a generalized moral rule in the Analects is the reading of a pair of passages that use a formulation similar to that of the “Golden Rule” of the Christian Bible (Matthew 7:12 and Luke 6:31) to describe benevolence: “Do not impose upon others those things that you yourself do not desire” (12.2, cf. 5.12, 15.24). Read as axiomatic moral imperatives, these passages differ from the kind of exemplar-based and situational conversations about morality usually found in the Analects . For this reason, some scholars, including E. Bruce Brooks, believe these passages to be interpolations. While they are not wholly inconsistent with the way that benevolence is described in early texts, their interpretation as abstract principles has been influenced by their perceived similarity to the Biblical examples. In the Records of Ritual , a slightly different formulation of a rule about self and others is presented as not universal in its scope, but rather as descriptive of how the exemplary ruler influences the people. In common with other early texts, the Analects describes how the moral transformation of society relies on the positive example of the ruler, comparing the influence of the gentleman on the people to the way the wind blows on the grass, forcing it to bend (12.19). In a similar vein, after discussing how the personal qualities of rulers of the past determined whether or not their subjects could morally transform, the Records of Ritual expresses its principle of reflexivity:

That is why the gentleman only seeks things in others that he or she personally possesses. [The gentleman] only condemns things in others that he or she personally lacks. (“ Daxue ” 大學)

This is a point about the efficacy of moral suasion, saying that a ruler cannot expect to reform society solely by command since it is only the ruler’s personal example that can transform others. For this reason, the ruler should not compel behaviors from his subjects to which he or she would not personally assent, something rather different from the “Golden Rule”. Historically, however, views that Confucius was inspired by the same Natural Theology as Christians, or that philosophers are naturally concerned with the generalization of moral imperatives, have argued in favor of a closer identification with the “Golden Rule,” a fact that illustrates the interpretative conundrum arising from the formal aspects of the Analects .

Early Zhou political philosophy as represented in the Classic of Odes and the Classic of Documents centered on moral justification for political authority based on the doctrine of the “Mandate of Heaven” ( tianming 天命). This view was that the sage’s virtue ( de ) attracted the attention of the anthropomorphized cosmic power usually translated as “Heaven” ( tian 天), which supported the sage’s rise to political authority. These canonical texts argued that political success or failure is a function of moral quality, evidenced by actions such as proper ritual performance, on the part of the ruler. Confucius drew on these classics and adapted the classical view of moral authority in important ways, connecting it to a normative picture of society. Positing a parallel between the nature of reciprocal responsibilities of individuals in different roles in two domains of social organization, in the Analects Confucius linked filial piety in the family to loyalty in the political realm:

It is rare for a person who is filially pious to his parents and older siblings to be inclined to rebel against his superiors… Filial piety to parents and elder siblings may be considered the root of a person. (1.2)

This section examines Confucius’s social and political philosophy, beginning with the central role of his analysis of the traditional norm of filial piety.

Just as Confucius analyzed the psychology of ritual performance and related it to individual moral development, his discussion of filial piety was another example of the development and adaptation of a particular classical cultural pattern to a wider philosophical context and set of concerns. Originally limited to descriptions of sacrifice to ancestors in the context of hereditary kinship groups, a more extended meaning of “filial piety” was used to describe the sage king Shun’s 舜 (trad. r. 2256–2205 BCE) treatment of his living father in the Classic of Documents . Despite humble origins, Shun’s filial piety was recognized as a quality that signaled he would be a suitable successor for the sage king Yao 堯 (trad. r. 2357–2256 BCE). Confucius in the Analects praised the ancient sage kings at great length, and the sage king Yu 禹 for his filial piety in the context of sacrifice (8.21). However, he used the term filial piety to mean both sacrificial mastery and behaving appropriately to one’s parents. In a conversation with one of his disciples he explains that filial piety meant “not contesting”, and that it entailed:

while one’s parents were alive, serving them in a ritually proper way, and after one’s parents died, burying them and sacrificing to them in a ritually proper way. (2.5)

In rationalizing the moral content of legacies of the past like the three-year mourning period after the death of a parent, Confucius reasoned that for three years a filially pious child should not alter a parent’s way (4.20, cf. 19.18), and explains the origin of length of the three-year mourning period to be the length of time that the parents had given their infant child support (17.21). This adaptation of filial piety to connote the proper way for a gentleman to behave both inside and outside the home was a generalization of a pattern of behavior that had once been specific to the family.

Intellectual historian Chen Lai 陈来 has identified two sets of ideal traits that became hybridized in the late Warring States period. The first set of qualities describes the virtue of the ruler coming out of politically-oriented descriptions of figures like King Wen of Zhou, including uprightness ( zhi 直) and fortitude ( gang 剛). The second set of qualities is based on bonds specific to kinship groups, including filial piety and kindness ( ci 慈). As kinship groups were subordinated to larger political units, texts began to exhibit hybrid lists of ideal qualities that drew from both sets. Consequently, Confucius had to effectively integrate clan priorities and state priorities, a conciliation illustrated in Han’s Intertextual Commentary the Odes by his insistence that filial piety is not simply deference to elders. When his disciple Zengzi 曾子 submitted to a severe beating from his father’s staff in punishment for an offense, Confucius chastises Zengzi, saying that even the sage king Shun would not have submitted to a beating so severe. He goes on to explain that a child has a dual set of duties, to both a father and ruler, the former filial piety and the other loyalty. Therefore, protecting one’s body is a duty to the ruler and a counterweight to a duty to submit to one’s parent (8). In the Classic of Filial Piety ( Xiaojing 孝經), similar reasoning is applied to a redefinition of filial piety that rejects behaviors like such extreme submission because protecting one’s body is a duty to one’s parents. This sort of qualification suggests that as filial piety moved further outside its original family context, it had to be qualified to be integrated into a view that valorized multiple character traits.

Since filial piety was based on a fundamental relationship defined within the family, one’s family role and state role could conflict. A Classic of Documents text spells out the possible conflict between loyalty to a ruler and filial piety toward a father (“ Cai Zhong zhi ming ” 蔡仲之命), a trade-off similar to a story in the Analects about a man named Zhi Gong 直躬 (Upright Gong) who testified that his father stole a sheep. Although Confucius acknowledged that theft injures social order, he judged Upright Gong to have failed to be truly “upright” in a sense that balances the imperative to testify with special consideration for members of his kinship group:

In my circle, being upright differs from this. A father would conceal such a thing on behalf of his son, and a son would conceal it on behalf of his father. Uprightness is found in this. (13.18)

In this way, too, Confucius was adapting filial piety to a wider manifold of moral behaviors, honing his answer to the question of how a child balances responsibility to family and loyalty to the state. While these two traits may conflict with one and other, Sociologist Robert Bellah, in his study of Tokugawa and modern Japan, noted how the structural similarity between loyalty and filial piety led to their both being promoted by the state as interlinked ideals that located each person in dual networks of responsibility. Confucius was making this claim when he connected filial piety to the propensity to be loyal to superiors (1.2). Statements like “filial piety is the root of virtuous action” from the Classic of Filial Piety connect loyalty and the kind of action that signals the personal virtue that justifies political authority, as in the historical precedent of the sage king Shun.

Of the classical sources from which Confucius drew, two were particularly influential in discussions of political legitimation. The Classic of Odes consists of 305 Zhou period regulated lyrics (hence the several translations “songs”, “odes”, or “poems”) and became numbered as one of the Five Classics ( Wujing ) in the Han dynasty. Critical to a number of these lyrics is the celebration of King Wen of Zhou’s overthrow of the Shang, which is an example of a virtuous person seizing the “Mandate of Heaven”:

This King Wen of ours, his prudent heart was well-ordered. He shone in serving the High God, and thus enjoyed much good fortune. Unswerving in his virtue, he came to hold the domains all around. (“ Daming ” 大明)

The Zhou political theory expressed in this passage is based on the idea of a limited moral universe that may not reward a virtuous person in isolation, but in which the High God ( Shangdi 上帝, Di 帝) or Heaven will intercede to replace a bad ruler with a person of exceptional virtue. The Classic of Documents is a collection that includes orations attributed to the sage rulers of the past and their ministers, and its arguments often concern moral authority with a focus on the methods and character of exemplary rulers of the past. The chapter “Announcement of Kang” (“ Kanggao ” 康誥) is addressed to one of the sons of King Wen, and provides him with a guide for behaving as sage ruler as well as with methods that had been empirically proven successful by those rulers. When it comes to the mandate inherited from King Wen, the chapter insists that the mandate is not unchanging, and so as ruler the son must always be mindful of it when deciding how to act. Further, it is not always possible to understand Heaven, but the “feelings of the people are visible”, and so the ruler must care for his subjects. The Zhou political view that Confucius inherited was based on supernatural intercession to place a person with personal virtue in charge of the state, but over time the emphasis shifted to the way that the effects of good government could be viewed as proof of a continuing moral justification for that placement.

Confucius himself arguably served as a historical counterexample to the classical “Mandate of Heaven” theory, calling into question the direct nature of the support given by Heaven to the person with virtue. The Han period Records of the Historian biography of Confucius described him as possessing all the personal qualities needed to govern well, but wandering from state to state because those qualities had not been recognized. When his favorite disciple died, the Analects records Confucius saying that “Heaven has forsaken me!” (11.9). Wang Chong’s 王充 (27–c.97 CE) Balanced Discussions ( Lunheng 論衡) uses the phrase “uncrowned king” ( suwang 素王) to describe the tragic situation: “Confucius did not rule as king, but his work as uncrowned king may be seen in the Spring and Autumn Annals ” (80). The view that through his writings Confucius could prepare the world for the government of a future sage king became a central part of Confucius lore that has colored the reception of his writings since, especially in works related to the Spring and Autumn Annals and its Gongyang Commentary . The biography of Confucius reinforced the tragic cosmological picture that personal virtue did not always guarantee success. Even when Heaven’s support is cited in the Analects , it is not a matter of direct intercession, but expressed through personal virtue or cultural patterns: “Heaven gave birth to the virtue in me, so what can Huan Tui 桓魋 do to me?” (7.23, cf. 9.5). As Robert Eno has pointed out, the concept of Heaven also came to be increasingly naturalized in passages like “what need does Heaven have to speak?” (17.19). Changing views of the scope of Heaven’s activity and the ways human beings may have knowledge of that activity fostered a change in the role of Heaven in political theory.

Most often, in dialogues with the rulers of his time, references to Heaven were occasions for Confucius to encourage rulers to remain attentive to their personal moral development and treat their subjects fairly. In integrating the classical legacy of the “Mandate of Heaven” that applied specifically to the ruler or “Son of Heaven” ( tianzi 天子), with moral teachings that were directed to a wider audience, the nature of Heaven’s intercession came to be understood differently. In the Analects and writings like those attributed to Mencius, descriptions of virtue were often adapted to contexts such as the conduct of lesser officials and the navigation of everyday life. Kwong-Loi Shun notes that in such contexts, the influence of Heaven remained as an explanation of both what happened outside of human control, like political success or lifespan, and of the source of the ethical ideal. In the Analects , the gentleman’s awe of Heaven is combined with an awe of the words of the sages (16.8), and when Confucius explains the Zhou theory of the “mandate of Heaven” in the Elder Dai’s Records of Ritual, he does so in order to explain how the signs of a well-ordered society demonstrate that the ruler’s “virtue matches Heaven” (“ Shaojian ” 少閒). Heaven is still ubiquitous in the responses of Confucius to questions from rulers, but the focus of the responses was not on Heaven’s direct intercession but rather the ruler’s demonstration of his personal moral qualities.

In this way, personal qualities of modesty, filial piety or respect for the elders were seen as proof of fitness to serve in an official capacity. Qualification to rule was demonstrated by proper behavior in the social roles defined by the “five relationships” ( wulun 五倫), a formulation seen in the writings of Mencius that became a key feature of the interpretation of works associated with Confucius in the Han dynasty. The Western Han emperors were members of the Liu clan, and works like the Guliang Commentary ( Guliang zhuan 穀梁傳) to the Spring and Autumn Annals emphasized normative family behavior grounded in the five relationships, which were (here, adapted to include mothers and sisters): ruler and subject, parent and child, husband and wife, siblings, and friends. Writing with particular reference to the Classic of Filial Piety , Henry Rosemont and Roger Ames argue that prescribed social roles are a defining characteristic of the “Confucian tradition”, and that such roles were normative guides to appropriate conduct. They contrast this with the “virtue ethics” approach they say requires rational calculation to determine moral conduct, while filial piety is simply a matter of meeting one’s family obligations. Just as the five virtues were placed at the center of later theories of moral development, once social roles became systematized in this way, selected situational teachings of Confucius consistent with them could become the basis of more abstract, systematic moral theories. Yet this could not have happened without the adaptation of the abstract classical political theory of “Heaven’s mandate”, a doctrine that originally supported the ruling clan, to argue that Heaven’s influence was expressed through particular concrete expressions of individual virtue. As a result of this adaptation in writings associated with Confucius, the ruler’s conduct of imperial rituals, performance of filial piety, or other demonstrations of personal virtue provided proof of moral fitness that legitimated his political authority. As with the rituals and the virtues, filial piety and the mandate of Heaven were transformed as they were integrated with the classics through the voices of Confucius and the rulers and disciples of his era.