An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Taylor & Francis Open Select

The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research

Joanna brooks.

a University of Huddersfield, Centre for Applied Psychological and Health Research , Institute for Research in Citizenship and Applied Human Sciences , Huddersfield, UK

Serena McCluskey

Emma turley.

b Manchester Metropolitan University , Department of Health Professions , Manchester, UK

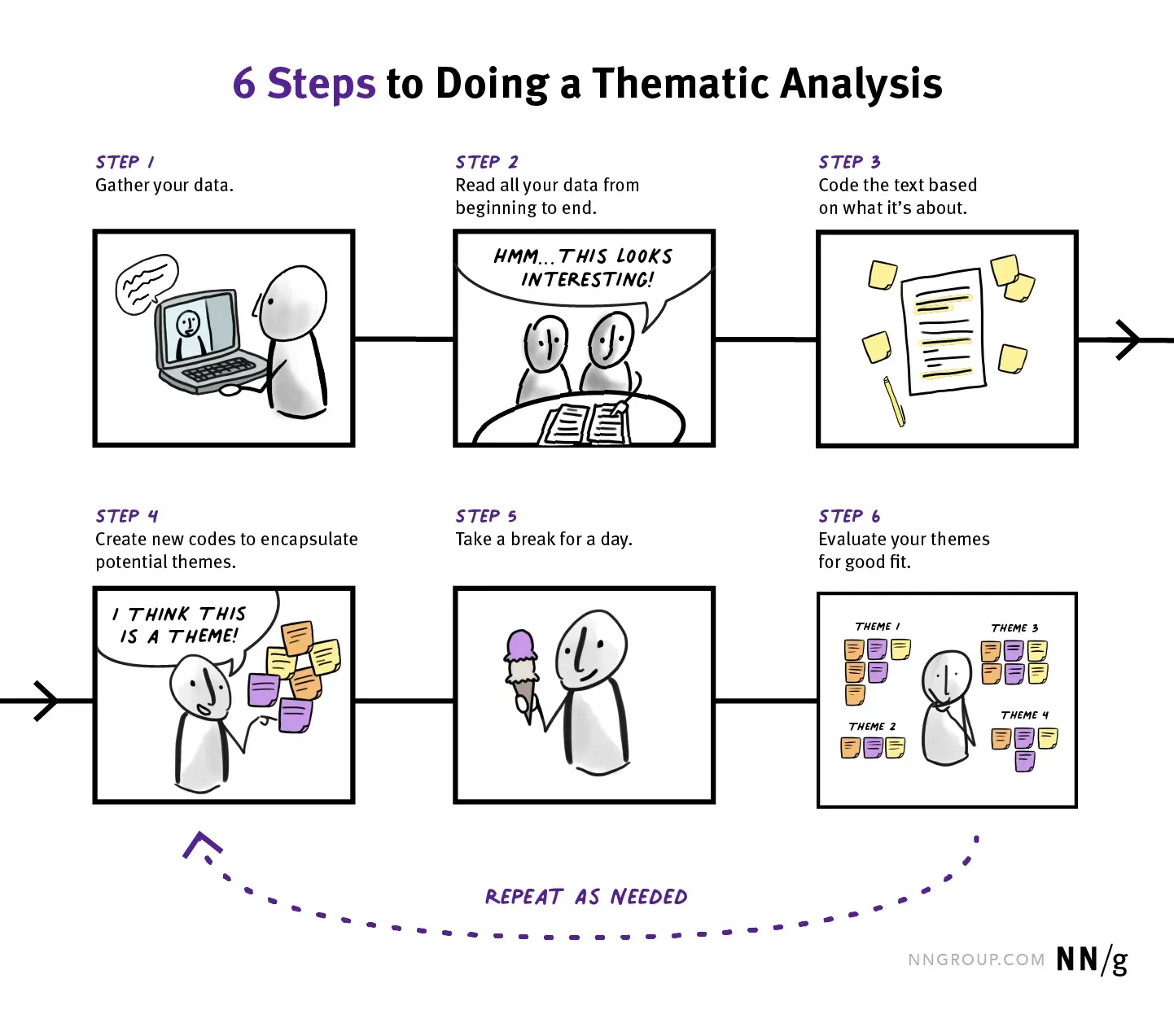

Thematic analysis is widely used in qualitative psychology research, and in this article, we present a particular style of thematic analysis known as Template Analysis. We outline the technique and consider its epistemological position, then describe three case studies of research projects which employed Template Analysis to illustrate the diverse ways it can be used. Our first case study illustrates how the technique was employed in data analysis undertaken by a team of researchers in a large-scale qualitative research project. Our second example demonstrates how a qualitative study that set out to build on mainstream theory made use of the a priori themes (themes determined in advance of coding) permitted in Template Analysis. Our final case study shows how Template Analysis can be used from an interpretative phenomenological stance. We highlight the distinctive features of this style of thematic analysis, discuss the kind of research where it may be particularly appropriate, and consider possible limitations of the technique. We conclude that Template Analysis is a flexible form of thematic analysis with real utility in qualitative psychology research.

Introduction

Thematic analysis has for a long time held a rather uncertain place in qualitative psychology. On the one hand, it has often been treated rather dismissively as an approach that is rather simplistic and rather shallow. On the other, it is used extensively, both as an integral part of popular methodologies such as Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and Grounded Theory, and as a method in its own right. Braun and Clarke’s 2006 article in this journal played an important role in advocating the latter position, and provided guidelines for one particular style of analysis. However, as they acknowledge and as others have argued (e.g., King & Horrocks 2010 ), there exist multiple ways of doing thematic analysis. These alternatives tend not to be well-known to qualitative psychologists, as in many cases they have developed in other disciplines; examples include Matrix Analysis (Miles & Huberman 1994 ; Nadin & Cassell 2004 ) and Framework Analysis (Ritchie & Spencer 1994 ). It is our contention that broadening awareness of different ways to analyze data thematically can only be helpful to qualitative psychologists. In this article we present a style of thematic analysis known as Template Analysis, which has been widely used in organizational and management research, as well as across other disciplines, but is not prominent in qualitative psychology. We outline the technique and consider its epistemological position, before presenting three case studies of projects to illustrate the diverse ways in which it may usefully be employed. In the conclusion we highlight what we feel are the distinctive features of this style of thematic analysis, discuss the kind of research where it may be particularly appropriate, and consider possible limitations of the technique. This article is primarily intended for psychologists who may not be very familiar with this particular form of thematic analysis. Nonetheless, by demonstrating its use in different settings and from different methodological approaches, it offers potential new insights for those who already have some experience with Template Analysis.

What Is Template Analysis?

Template Analysis is a form of thematic analysis which emphasises the use of hierarchical coding but balances a relatively high degree of structure in the process of analysing textual data with the flexibility to adapt it to the needs of a particular study. Central to the technique is the development of a coding template, usually on the basis of a subset of data, which is then applied to further data, revised and refined. The approach is flexible regarding the style and the format of the template that is produced. Unlike some other thematic approaches to data coding, it does not suggest in advance a set sequence of coding levels. Rather, it encourages the analyst to develop themes more extensively where the richest data (in relation to the research question) are found. Equally, Template Analysis does not insist on an explicit distinction between descriptive and interpretive themes, nor on a particular position for each type of theme in the coding structure. The data involved in Template Analysis studies are usually interview transcripts (e.g., Goldschmidt et al. 2006 ; Lockett et al. 2012 ; Slade, Haywood & King 2009 ; Thompson et al. 2010 ) but may be any kind of textual data, including focus groups (e.g., Kirkby-Geddes, King & Bravington 2013 ; Brooks 2014 ), diary entries (e.g., Waddington & Fletcher 2005 ), and open-ended question responses on a written questionnaire (e.g., Dornan, Carroll & Parboosingh 2002 ; Kent 2000 ). The main procedural steps in carrying out Template Analysis are outlined below (these are described in more detail in King 2012 ).

- Become familiar with the accounts to be analyzed. In a relatively small study, for example, ten or fewer hour-long interviews, it would be sensible to read through the data set in full at least once. In a larger study, the researcher may select a subset of the accounts (e.g., transcripts, diary entries, daily field notes) to start.

- Carry out preliminary coding of the data. This is essentially the same process as used in most thematic approaches, where the researcher starts by highlighting anything in the text that might contribute toward his or her understanding. However, in Template Analysis, it is permissible (though not obligatory) to start with some a priori themes, identified in advance as likely to be helpful and relevant to the analysis. These are always tentative, and may be redefined or removed if they do not prove to be useful for the analysis at hand.

- Organize the emerging themes into meaningful clusters, and begin to define how they relate to each other within and between these groupings. This will include hierarchical relationships, with narrower themes nested within broader ones. It may also include lateral relationships across clusters. Themes which permeate several distinct clusters are sometimes referred to as “integrative themes.” For example, in a study of the experience of diabetic renal disease, King et al. ( 2002 ) identified “stoicism” and “uncertainty” as integrative themes because these aspects of experience tended to infuse much of the discussion whatever the foreground issue.

- Define an initial coding template. It is normal in Template Analysis to develop an initial version of the coding template on the basis of a subset of the data rather than carrying out preliminary coding and clustering on all accounts before defining the thematic structure. For example, in a study consisting of 20 face-to-face interviews, the researcher might carry out the steps described above on five of the interviews, and at that point draw together the initial template. The exact point at which it is appropriate to construct the initial template will vary from study to study and cannot be prescribed in advance—the researcher needs to be convinced that the subset selected captures a good cross-section of the issues and experiences covered in the data as a whole. This is usually facilitated by selecting initial accounts to analyse that are as varied as possible.

- Apply the initial template to further data and modify as necessary. The researcher examines fresh data and where material of potential relevance to the study is identified, he or she considers whether any of the themes defined on the initial template can be used to represent it. Where existing themes do not readily “fit” the new data, modification of the template may be necessary. New themes may be inserted and existing themes redefined or even deleted if they seem redundant. Rather than reorganising the template after every new account examined, it is common to work through several accounts noting possible revisions and then construct a new version of the template. Thus in our hypothetical example at the previous stage, the researcher might take the initial template constructed from analysis of the first five interviews and apply it to another three transcripts, after which he or she would produce a revised version. This iterative process of trying out successive versions of the template, modifying and trying again can continue for as long as seems necessary to allow a rich and comprehensive representation of the researcher’s interpretation of the data. Of course, very often practical constraints of time and resource may limit the number of iterations possible, but the analysis should not leave any data of clear relevance to the study’s research question uncoded.

- Finalize the template and apply it to the full data set. In some respects it should be said that there is never a “final” version of the template, in that continued engagement with the data can always suggest further refinements to coding. On a pragmatic basis, though, the researcher needs to decide when the template meets his or her needs for the project at hand, and considering the resources available. A good rule of thumb is that development of a template cannot be seen as sufficient if there remain substantial sections of data clearly relevant to the research question(s) that cannot been coded to it. It is always possible to revisit the template if further analysis is required; for example, a template that may work well to help the interpretation of data for an evaluation report might require considerable refinement to produce an analysis that informs an academic journal article (see Kirkby-Geddes, King & Bravington 2013 for an example).

Epistemological Position of Template Analysis

The epistemological position of thematic analysis can be problematic. It is not uncommon to see research articles at the review stage (and sometime in print) that claim to have used a specific methodology such as IPA or Grounded Theory, but where even a cursory examination shows that the basic theoretical underpinnings of such approaches have not been adhered to. Instead, the researchers have taken the thematic analysis procedures associated with a methodology and used them in a way that is not in keeping with the methodology as a whole. An example would be studies “using” IPA, where theoretical ideas from mainstream psychology (or elsewhere) have been used quite prominently in shaping the analysis. While the use of existing theory in, for example, the design of an IPA study need not conflict with the basic tenets of the approach (e.g., Brooks, King & Wearden 2013 ), IPA is principally focused on individual’s experience (Smith, Flowers & Larkin 2009 ) and codes are generated from the data using a “bottom up” approach. Approaching analysis with the intention of imposing existing theory or concepts on the data would thus be out of keeping with an IPA approach. Using methods such as IPA or grounded theory in a manner not in keeping with the approach often reflects a confusion between methodology and data analytical method, but may also be due to discomfort with a “mere” thematic analysis, devoid of inherent philosophical position. We would concur with Braun and Clarke’s ( 2006 ) position that thematic analysis methods can be applied across a range of theoretical and epistemological approaches: what is important is that researchers using thematic analysis methods are explicit and upfront about their particular epistemological assumptions.

Similarly, Template Analysis is not inextricably bound to any one epistemology; rather, it can be used in qualitative psychology research from a range of epistemological positions. The flexibility of the technique allows it to be adapted to the needs of a particular study and that study’s philosophical underpinning. Template Analysis can thus be used in research taking a similar realist position to mainstream quantitative psychology, concerned with “discovering” underlying causes of human action and particular human phenomena. When used in this way, one could expect to see the use of strong, well-defined a priori themes in analysis, and concerns with reliability and validity prioritised and addressed. In contrast, Template Analysis can also be used within what Madill, Jordan and Shirley ( 2000 ) have termed a “contextual constructivist” position (p. 9), a stance which assumes that there are always multiple interpretations to be made of any phenomenon, and that these depend upon the position of the researcher and the specific social context of the research. A researcher using Template Analysis from this position would be likely to take a bottom-up approach to template development, using a priori themes far more tentatively, if at all, in the development of their template. Additionally, and somewhere between these two approaches, Template Analysis can also be used in research adopting a “subtle realist” approach (e.g., Hammersley 1992 ), a position which acknowledges that a researcher’s perspective is inevitably influenced by his or her inability to truly stand outside one’s own position in the social world, but nonetheless retains a belief in phenomena that are independent of the researcher and knowable through the research process. Such an approach can thus make claims as to the validity of a representation arising from research while recognizing that other perspectives on the phenomenon are possible. The applicability of Template Analysis taking a social constructionist approach, with its radical relativist epistemology, is more questionable. Certainly, it is not suited to those social constructionist methodologies that are concerned with the fine detail of how language constructs social reality in interaction, such as discursive psychology and conversation analysis. However, some social constructionist work does seek to look at text in a broader manner and may use thematic types of analysis (e.g., Taylor & Ussher 2001 ; Budds, Locke & Burr 2013 ); there is no reason why Template Analysis should not be considered for this kind of analysis, though it would be crucial to be clear that themes were defined in terms of aspects of discourse rather than representations of personal experience.

How Template Analysis Relates to Other Forms of Thematic Analysis

We are sometimes asked how Template Analysis differs from, or is similar to, “thematic analysis.” This is not really a meaningful question because thematic analysis is not a particular approach in and of itself; rather, it is a broad category of approaches to qualitative analysis that seek to define themes within the data and organise those themes into some type of structure to aid interpretation. A more sensible question is therefore how Template Analysis relates to other forms of thematic analysis. One main distinction is between those thematic approaches that are incorporated within a specific methodology and its philosophical assumptions, such as Grounded Theory or IPA, and those that do not have such a commitment. Template Analysis clearly falls into the latter category, alongside such techniques as Braun and Clarke’s ( 2006 ) version of thematic analysis, Framework Analysis (Ritchie & Spencer 1994 ), and many others. We will summarize here some of the key similarities and differences between Template Analysis and these two approaches in particular.

Template Analysis shares with Braun and Clark’s approach flexibility and a focus on developing a hierarchical coding structure. They differ in three main ways. Firstly, in Braun and Clark development of themes and creation of a coding structure take place after initial coding of all the data. In Template Analysis it is normal to produce an initial version of the template on the basis of a sub-set of the data. Secondly, in Braun and Clark’s methods, defining themes is a late phase of the process. In Template Analysis the researchers often produce theme definitions at the initial template stage, to guide further coding and template development. Thirdly, while Braun and Clark do not specify limits to the number of levels of coding, studies using their approach typically have only one or two levels of sub-themes. Template Analysis commonly uses four or more levels to capture the richest and most detailed aspects of the data.

Template Analysis has much in common with Framework Analysis; they can be seen as having evolved in parallel to address many of the same needs. Both are examples of what Crabtree and Miller (1992) refer to as “codebook” approaches, where a coding structure is developed from a mixture of a priori interests and initial engagement with the data and then applied to the full data set. The most notable difference between them is that Template Analysis is more concerned with providing detailed guidance on the development of the coding structure than Framework Analysis, and less concerned with delineating techniques to aid in the interpretation of the data once fully coded. Studies using Framework Analysis do not typically show the depth of coding we see in Template Analysis, and while the need to modify the framework in the course of analysis is recognized (e.g., Gale et al. 2013 ), in general the iterative (re-) development of the coding structure is a much more central aspect in Template Analysis. Conversely, the emphasis in Framework Analysis on reducing the data through “charting” and identifying patterns by “mapping” is not an essential part of Template Analysis. These differences in emphasis to a large extent represent the different disciplinary backgrounds of the techniques and those involved in their evolution. Framework Analysis was developed by health services researchers specifically for use in health policy research contexts. Template Analysis has strong roots in organisational research and is probably used in a wider variety of research settings than Framework Analysis. It also tends to be employed rather more in experientially focused studies than is Framework Analysis, reflecting the input of experientially orientated psychologists in its development.

We feel that it is crucial that researchers are not precious about “their” ways of working with thematic analysis. For novice researchers, the detailed guidance provided by the likes of Braun and Clarke ( 2006 ), Richie and Spencer ( 1994 ), and the current authors can be very helpful in steering them through the rocks and shoals of qualitative analysis. For those with more experience, it is entirely appropriate that they should draw selectively on such sources to define an approach that suits the needs of their own study. This is one of the reasons we refer to Template Analysis as a “style” of thematic analysis; in the next section we offer examples to illustrate different ways in which this style can be put into practice.

Examples of Research Using Template Analysis

To illustrate how Template Analysis can be used in qualitative psychology research, we will now describe three rather different examples of research undertaken by the authors, all of which successfully used the technique. We focus on the analysis stage of each project to illustrate how Template Analysis may be used and adapted to meet the particular needs of a specific research project. At the end of each example, we have included a text box highlighting the main challenge in using Template Analysis in the particular case and how we addressed it. Beyond these examples, Template Analysis has been used in a wide range of other settings including education, clinical psychology and sports science (King 2012 provides more detail and references).

Case Study 1. Collaborative working in cancer care: An example of a large-scale project using a team analysis approach

Our first example is taken from a large scale three year research project, undertaken by the first and last author and colleagues (King, Melvin, Brooks, Wilde & Bravington 2013 ). The focus of this research, which was funded by Macmillan Cancer Support, was an exploration of how different health care professionals in the United Kingdom work together to provide supportive and palliative care to patients with cancer and other long-term chronic health conditions. The main research aims were: (i) to examine how specialist and generalist nurses work with each other and with other professionals, carers, and patients in providing supportive and palliative care to cancer patients; and (ii) to explore how these professional practices and relationships might differ in the care of long-term condition patients. The theoretical position of this research drew on symbolic interactionist views of the professions (e.g., Macdonald 1995 ) and constructivist psychological approaches to the person (e.g., Butt 1996 ). These traditions emphasize that professional roles and identities are not fixed aspects of social structures, but are defined through the ways in which individual professionals interact with the social world they inhabit. This does not mean that nurses (in the case of the present study) are free to construe roles and identities in whatever way they please; they are inevitably influenced by the views of professional bodies, their interactions with nursing and other professional colleagues, and of course the expectations of patients.

There were a number of implications for the research arising from this theoretical orientation. First, it suggested the need to examine the social context of particular groups of nurses in order to understand the circumstances that shape the way they understand their roles and identities. Second, it placed relationships and interactions at work at the center of our research agenda. Third, given the complexity of the ways in which people understand their roles and relationships, it necessitated a methodological approach that was flexible and able to examine nurses’ experiences in depth. Our methodology was therefore one that was centrally concerned with the way different groups of nurses involved in the supportive care of cancer and long-term condition patients worked with and understood each other’s—and their own—roles and professional identities.

The research utilized a novel interview tool, the Pictor technique (King Bravington, Brooks et al. 2013 ), to explore networks of care and support in health and social care. The technique requires the research participant to choose a case of collaborative working in which they are, or have been, involved (in interviews with lay people this means their own case as patient, or that of the person they care for). Participants are provided with a set of arrow-shaped Post It notes, and asked to label these to represent all those involved in a particular case, then lay the notes out on a large sheet of paper in a manner that helps them tell the story of their case. The Pictor chart produced by the participant serves as the basis for the researcher to explore and reflect upon the case with the participant. Figure 1 shows an example of a Pictor chart from this study. Our primary focus in this study was on nursing staff, in both the acute (secondary care) and community (primary care) sectors, but we also interviewed a wide range of other health and social care professionals, and some patients and carers.

Example of a ‘Pictor’ chart.

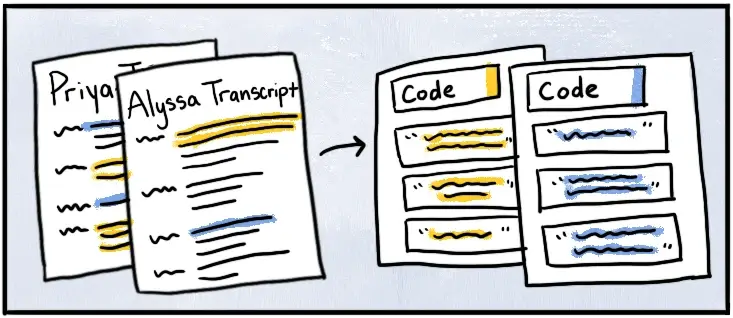

Our total sample size numbered 79 participants, with most interviews lasting between 45 minutes and an hour and a quarter, making this a large scale project in qualitative research terms. Our research team comprised four academic psychologists and a nurse professional, and we adopted a team approach to data analysis and template development. A priori codes were defined through discussion, in the light of the stated aims of the project and through drawing on key issues emerging from previous research and policy literature in this area (including several of our own previous studies). For example, our a priori codes included broad themes identified as a priority by the research funder (e.g., issues around the concept of “survivorship”); themes determined by our research aims (e.g., comparisons between cancer and long-term conditions); and themes derived from our previous research findings (e.g., perceptions of a particular community nursing role, that of Community Matron; see King et al. 2010 ). An initial template ( Figure 2 ) was developed through group analysis of early interviews undertaken with participants from different professional groups. Over the next eight months, and in parallel with on-going data collection, the research team met at regular intervals to analyze further interviews, again using interview data from different participant groups. We have found this kind of collaborative working strategy valuable, as the process necessitates clear agreement and justification for the inclusion of each code, and a clear definition of its use.

Case study 1 - initial template.

Decisions about when a template is “good enough” are unique to each particular project and will inevitably face pragmatic external constraints. In this project, at version 8 of our template, and after group analysis of 25 interviews, all research team members were in agreement that the template covered all sections of text thus far encountered adequately and was likely to require no more than minimal modifications. The remaining interview transcripts were analysed individually by team members. Our group sessions of data analysis meant that all members of the research team had a good understanding of the template, which was, given the size and complexity of the final version, a great advantage when coding at these later stages. Coding was undertaken using the qualitative research software NVivo, which allowed for the coding of any data which appeared to be important but which was not accounted for in the template to be coded under a “free node.” Any such additions were reviewed at our on-going regular research team meetings, and agreements reached as to whether and where to make revisions to the template.

In our final version of the template we had four top level themes: (1) what affects collaborative working, (2) condition-specific involvement, (3) survivorship, and (4) current National Health Service (NHS) re-organization. Given that there are fewer top level themes than in our initial version ( Figure 2 ), it might appear that the template has been shortened and simplified. Not so: in fact, with closer examination of the data, and continual discussion amongst the team, the coding has significantly increased in depth, representing increased discrimination and clarity in our thinking about the data. Figure 3 shows the first top level theme (What affects collaborative working?) for the final version of our template. Depth, rather than breadth, of coding allows fine distinctions to be made in key areas: having too many top level themes may make it hard for a researcher to draw together the analysis as a whole. Figure 2 shows the entire initial template, including top level themes and all lower level coding. In contrast, Figure 3 shows just the first top level theme and the lower level coding associated with this one theme from our final template. Our final version template was a nine A4 page document, in comparison to our version 1 template, which, in contrast, covered just one and a half sides of A4.

Case study 1 - version 8 template (top theme 1 only shown).

Findings from this research particularly highlighted the role of relational issues in collaborative working both between generalist and specialist nurses, and between different professionals from health and social care sectors. Rather than seeing relational issues as one among a number of important factors, our work suggests that relationships and relating are the core of collaborative working, and that as such, all those concerned with this phenomenon—researchers, practitioners, and policy makers—should view collaborative working through a relational lens and think carefully about the impact on relational aspects of collaborative working in the design and implementation of any change in services. We also drew attention in our findings to the striking difference between nursing services available to patients in the community depending on their particular illness condition, suggesting that there was seemingly a gap in support for cancer survivors within community-based services. Full findings are reported in King, Melvin, et al. ( 2013 ). The key challenge for using Template Analysis in this study, and our solutions to it, are shown in Figure 4 .

Case Study 2. Patient and significant other beliefs about back pain and work participation: An example of a study using existing theory in template development

Our second example used Template Analysis in a rather different way to meet the needs of the particular research project. The focus of this study (undertaken by the first, second, and last authors and colleagues) (McCluskey et al. 2011 ) was an exploration of work participation outcomes in patients with chronic low back pain, a leading cause of work disability in the United Kingdom (Health and Safety Executive 2007 ).

An emerging body of research has suggested that beliefs about illness (illness perceptions) are important influences on clinical and work outcomes for those with back pain (e.g., Foster et al. 2008 ; Main, Foster & Buchbinder 2010 ; Hoving et al. 2010 ; Giri et al. 2009 ). One theoretical model which has been widely established as a useful framework through which to explore illness perceptions is the Common- Sense model of self-regulation of health and illness (the CSM; e.g., Leventhal, Nerenz & Steele 1984 ). According to the CSM, illness perceptions (also known as illness beliefs, illness cognitions or illness representations) are patients’ own implicit, common-sense beliefs about their illness, and guide the way an individual responds to and manages their condition. Illness perceptions are categorised by the CSM into five core dimensions: illness identity (including symptoms and label), perceived cause, expectations about timeline (how long the illness is expected to last), consequences of the illness and beliefs about curability and control (Leventhal, Meyer & Nerenz 1980 ; Leventhal et al. 1984 ). The CSM holds that cognitive and emotional representations of illness exist in parallel. The two types of representations are proposed to result in differing behaviors and coping procedures with cognitive representations leading to problem-based coping and emotional representations to emotion-focused coping procedures (Moss-Morris et al. 2002). Illness perceptions have been acknowledged to determine coping style, treatment compliance, and emotional impact in a wide range of physical and mental health conditions (for a review see Hagger & Orbell 2003 ).

Most of the research which has undertaken using the CSM in the context of back pain has used quantitative measures to elicit individuals’ illness beliefs (e.g., Foster et al. 2008 ). In response to calls in the literature for more qualitative research to provide better insight into psychosocial obstacles to recovery and work participation for those with back pain (Nicholas 2010 ; Wynn & Money 2009 ), we undertook an exploratory interview study using the CSM to ask patients about their back pain in relation to work participation outcomes (see McCluskey et al. 2011 ). A novel aspect to this research was our inclusion of those close to patients—their “significant others”—to allow for an exploration of the wider social influences on work participation for those with back pain. Despite the body of empirical evidence documenting the role that significant others have on individual pain outcomes (e.g., Boothby et al. 2004 ; Leonard, Cano & Johansen 2006 ; Stroud et al. 2006 ), they are rarely included in work participation research. We interviewed five dyads (five patients and their significant others) about the patients’ back pain. A well validated quantitative measure of illness perceptions (the revised Illness Perceptions Questionnaire [IPQ-R]; Moss-Morris et al. 2002) was used as a guide to construct a semi-structured interview schedule, and we also used the scales which make up the IPQ-R as a priori themes to organise our initial template.

The IPQ-R provides a quantitative self-report assessment of the components delineated in the CSM, and additionally includes an assessment of emotional responses to illness (“emotional representations”) and an assessment of the extent to which individuals believe they have a clear understanding of their condition (“illness coherence”). The timeline dimension is divided into two subscales: acute/ chronic and cyclical (assessing whether or not patients believe their condition to be of a cyclical nature). The cure/ control dimension is also divided into two subscales: personal control (measuring the degree to which respondents believe they have the ability to control their condition themselves) and treatment control (measuring the degree to which respondents believe treatment is effective in controlling their condition). Our aim in this study was to build on existing mainstream theory, and we used the IPQ-R subscales as clear, strong a priori themes with which to design our initial coding template. We thus began our analysis using nine a priori themes (illness identity; beliefs about causality; beliefs about timeline (acute/chronic); beliefs about timeline (cyclical); beliefs about consequences of back pain; beliefs about personal control of back pain; beliefs about treatment control of back pain; emotional responses to condition; illness coherence). Our final coding template was comprised of six themes derived from the IPQ-R constructs (illness identity; beliefs about causality; expectations about timeline; perceived consequences of back pain; control, management and treatment of back pain; emotional responses to illness). Two additional higher level themes also emerged in our final template: (1) Patient identity—“claimant as genuine” and (2) role of significant others—“influence of/ impact on significant others.” The final template is shown in Figure 5 .

Case study 2 - final version template.

Patient identity emerged as an important aspect for both patient and significant other respondents. Findings from this research suggest that there is a danger that patients who feel unable to stay in or return to their previous employment may adopt a very limiting “disabled” identity as a protection from socio-cultural scepticism about their condition, and derogatory rhetoric about “benefits scroungers.” Such a strategy for defending the self may lead to a vicious circle whereby the patient focuses on what s/he cannot do, restricts activity further, and exacerbates the condition making it even less likely they will be able to return to work (McCluskey et al. 2011 ; Brooks et al. 2013 ). In the CSM framework, “illness identity” pertains to the specific symptoms associated by a patient with an illness, ideas about the label given to an illness, and beliefs about its nature. Our “patient identity” theme highlighted the ways in which an individual’s self-perception may additionally play an important role in their formulation of a model for symptoms, and their subsequent behavioural responses. Equally as important, such beliefs were shared and sometimes further reinforced by significant others. Our analysis supported the CSM as a useful framework to explore beliefs about illness, but was additionally able to incorporate some of the ways in which other factors and wider social circumstances, may impact on work outcomes for patients with chronic back pain. The key challenge for using Template Analysis in this study, and our solutions to it, are shown in Figure 6 .

Case Study 3. The erotic experience of BDSM participation: An example of a study using Template Analysis from an interpretive phenomenological stance

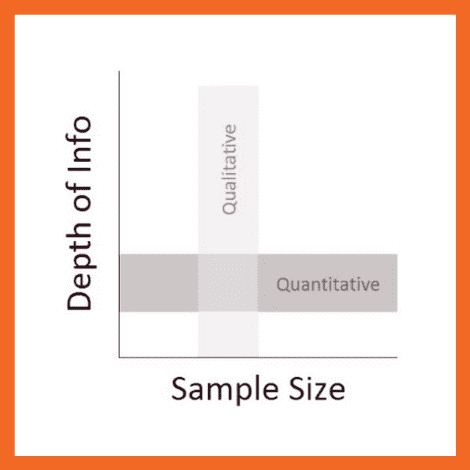

Our final example is taken from the third author’s research (Turley 2012 ). Broadly, this study aimed to investigate the lived experience of practitioners of consensual bondage, discipline, dominance & submission, and sadism & masochism (BDSM). Using a variety of innovative techniques to explore these experiences, the project successfully combined mixed phenomenological methods across two stages of empirical work. Template Analysis, when used within a broadly phenomenological perspective, has some clear similarities with IPA (e.g., Smith et al. 2009 ), another methodology widely used in qualitative research in psychology. There are two key features which differentiate between the approaches. Firstly, the idiographic focus of IPA and its detailed case-by-case analysis of individual transcripts maintaining the individual as a unit of analysis in their own right, mean that IPA studies are usually based on small samples. Template Analysis studies often (though not always) have rather more participants, and focus more on across case rather than within case analysis. Secondly, in IPA, codes are generated from the data rather than using pre-existing knowledge or theory that might be applied to the data set. In Template Analysis, the use of a priori codes allows the researcher to define some themes in advance of the analysis process.

In the first stage of this work, a descriptive phenomenological approach was used to explore the experiences of a sample of practitioners of consensual BDSM about their experiences (Turley, King & Butt 2011 ). A description of what was specifically erotic about BDSM participation was found to be noticeably absent from participants’ accounts. The second stage of this work, which employed Template Analysis to elucidate the specific constituents of BDSM that held erotic significance for participants, will be the focus of discussion in the present article. In this stage of the empirical work, semi-structured interviews were conducted with nine participants, four of whom had taken part in the first stage of the project while five were new recruitments to the research. The detail and depth of data collected produced a rich and complex final template, reflecting the experiences of practitioners of consensual BDSM.

Procedurally, this research differs from the other examples presented in this article in a number of ways. As is often the case when using Template Analysis, a set of a priori themes were selected as a focus for the initial template. However, rather than drawing on current theory or existing literature, salient findings from the first stage of this work were used to inform the selection of pertinent a priori themes. This was in part due to the paucity of previous research literature addressing eroticism and BDSM. Importantly, it was also a reflection of the phenomenological stance underpinning this work, and ensured analysis was grounded firmly in participants’ own accounts rather than presuppositions about the topic. Recognising that a phenomenological analysis requires an open attitude towards data, the researcher opted for a few broad a priori themes so as to avoid overlooking new and important aspects of the data that did not explicitly relate to those themes elicited from earlier work. This allowed for iterative redefinition of the themes, which were composed of the following: (1) the relationships between those involved in the BDSM scenes, (2) anticipation, (3) fantasy, and (4) authenticity. The author’s intention was to remain sensitive to these thematic areas, whilst simultaneously maintaining an open phenomenological stance. The interpretive phenomenological approach used in this research does not subscribe to the epochē, the philosophical notion that one can completely suspend presuppositions and judgements of a topic under study, viewing the phenomenon as if for the first time (Husserl 1931 ). The author used the technique of bracketing and self-reflection, endeavoring to remain open to participants’ accounts and making a determined effort to step outside of any personal and taken-for-granted views about the participants, their experiences and BDSM more generally. Through a process of critical self-reflection, enabling the author to identify, clarify, and reflect on her own perceptions of the research participants and the details of their experiences, the author was also able to critically examine how these perceptions might influence the analysis.

A further procedural difference between this study and other examples of work using Template Analysis relates to the development of the initial template (shown in Figure 7 ). It is common practice in studies utilizing Template Analysis to code a subset of data and to use this coding in the development of an initial template. At first, the intention was to use the original four participants’ transcripts to develop the template. However, the author became increasingly concerned that using only this data would make it more difficult to approach the remaining transcripts with a truly open phenomenological attitude. She therefore carried out preliminary coding of the entire data set, resulting in an initial template which is rather more comprehensive than might usually be expected (see Figure 7 ).

Case study 3 - initial template.

The initial template was used to code each interview transcript. The template was developed through the coding process to represent new emergent themes to segments of text, and modified so that existing themes were edited to include new material. A system using different colored self-adhesive notes was useful here, making it easier to move and reorganize themes in order to modify and develop the template. As reflected on above, the initial template in this study was more comprehensive than is often the case in Template Analysis. One potential danger in producing a very detailed initial template is that researchers may, further on in the analysis process, be unwilling to modify or alter the template structure. The ability to easily add, remove and alter the position of the adhesive notes representing themes in this analysis helped overcome any potential reluctance to make any significant modifications and made it easy to reorganise or reclassify themes when required. Each time a change was made to the template, the previous coding was adjusted to incorporate this. The final template is illustrated in Figure 8 , and demonstrates the extent of the modifications made through this process. Some themes from the initial template ( Figure 7 ) have been deleted completely, whilst others have been modified by broadening or narrowing a theme, or through re-classification of the theme’s hierarchical level. For example, the initial template contains the higher-order theme “temporality”; through development and modification of the template, this theme eventually became a lower order theme encapsulated within the higher order theme of “the qualities of BDSM participation,” which had itself been modified from its initial incarnation of “participants” understanding of their BDSM experience. The theme of “fantasy and reality” was reclassified from a higher order theme and became subsumed into the higher-order theme of “co-creation of fantasy world” as a lower order theme. Modifications to the templates were made on the basis of how best to capture and encompass all of the important elements of participants’ experiences of BDSM, and there were five versions of the developing template between the initial and final template. Through the various modifications of the template, and in line with her phenomenological approach to this work, the author endeavored to maintain an open attitude of discovery toward emerging themes in the data, ensuring that the structure of the template did not become fixed too early in the process of coding and analysis.

Case study 3 – final template.

Findings from both this and the first stage of this research reveal the complexity of BDSM, illustrated by subtle variations in the erotic scripts of participants. The co-creation of fantasy and the notion of authenticity were fundamental to the experience, which along with a sense of care, trust, and partnership, were vital in order to achieve the erotic atmosphere—the latter concepts appearing contrary to the kinds of sexual activity involved. While traditionally conceptualized as pathological by researchers taking an external perspective, this work successfully employed a phenomenological approach to contribute to an increasing body of work researching BDSM from a nonpathologizing perspective. The key challenge for using Template Analysis in this study, and our solutions to it, are shown in Figure 9 .

Conclusions

In this concluding section, we highlight what we feel are the main distinctive features of Template Analysis, and discuss how these may be advantageous in qualitative psychological research. We also reflect on possible limitations of the technique.

As exemplified by the three very different case studies presented in this article, Template Analysis is a highly flexible approach that can be readily modified for the needs of a particular study. The method can be adapted to fit different research topics and the available resources of a particular study. Additionally, Template Analysis can be used from a range of different epistemological and methodological positions. Compared with some other methods of qualitative data analysis, Template Analysis may offer a more flexible technique with fewer specified procedures, allowing researchers to tailor the approach to the requirements of their own project. Template Analysis may offer a suitable alternative to qualitative psychology researchers who find that other methods of analysis come with prescriptions and procedures which are difficult to reconcile with features of their own study.

A particular feature of Template Analysis is its use of a priori themes, allowing researchers to define some themes in advance of the analysis process. The case studies presented in this article demonstrate how a priori themes can be usefully employed in different ways in diverse areas of research: ensuring focus on key areas potentially relevant to a study, building on existing theory, and developing ideas in linked pieces of research. Although not a requirement of the method, the use of a priori themes can be particularly advantageous in qualitative psychology research with particular applied concerns which need to be incorporated into the analysis. A priori themes are equally subject to redefinition or removal as any other theme should they prove ineffective at characterising the data. However, the selective and judicious use of a priori themes can allow researchers to capture important theoretical concepts or perspectives that have informed the design and aims of a study, or to address practical concerns such as evaluation criteria that a research project has been designed to address.

There are potential limitations to the approach which should be acknowledged. The focus in Template Analysis is typically on across case rather than within case analysis, the result of which is unavoidably some loss of holistic understanding in relation to individual accounts. This is a limitation of any thematic approach to qualitative data analysis, and a problem which manifests more evidently in studies employing larger sample sizes. While recognizing this as a principally inescapable limitation, our response to this in our own work has often been to combine cross-case analysis with the more idiographic—the sagacious use of individual case summaries to illustrate a line of reasoning can successfully achieve this.

While the flexibility of Template Analysis is one of the method’s acknowledged strengths, the tractable process of developing an initial template and of the template structure itself may feel less secure for relatively inexperienced qualitative researchers than the kind of clear progression described in other forms of thematic analysis which explicitly advocate moving from the descriptive to the interpretive and finally toward overarching themes. Without such explicit instruction to keep initial coding purely descriptive, there is a danger that researchers can rush too far in the direction of abstraction in interpretation. However, in our extensive experience of teaching Template Analysis to novice researchers, we have not encountered many who have found the method’s flexible approach to coding structure problematic. A more prevalent difficulty we have observed in novice researchers using Template Analysis is the danger of losing sight of the original research project aims, and focusing on the constructed template as an end product, rather than a means to an end. It is essential to remember that template development is intended as a way of making sense of data, and not the purpose of the analysis in and of itself.

Overall though, we would suggest that Template Analysis offers a clear, systematic, and yet flexible approach to data analysis in qualitative psychology research. The flexibility of the coding structure in Template Analysis allows researchers to explore the richest aspects of data in real depth. The principles of the method are easily grasped, and the discipline of producing a template forces the researcher to take a systematic and well-structured approach to data handling. The use of an initial template followed by the iterative process of coding means that the method is often less time-consuming than other approaches to qualitative data analysis. Iterative use of the template encourages careful consideration of how themes are defined and how they relate to one another. This approach lends itself well to group or team analysis, and working in this way ensures a careful focus on elaborate coding structures as the team collaboratively define meanings and structure. Template analysis can additionally handle larger data sets rather more comfortably than some other methods of qualitative data analysis although it can also be used with small sample sizes and has been used in the analysis of a single autobiographical case (King 2008 ).

A common feature of qualitative psychological research is the extensive and often complex data it produces. How a researcher or research team move from this mass of data to produce an understanding of their research participants’ experiences depends upon their choice of data analysis technique. There is no one “best” method of data analysis in qualitative psychology research, with choices regarding analysis determined by broader theoretical assumptions underpinning the work and the research question itself. Nonetheless, we hope that in this article we have demonstrated that Template Analysis is, in our experience, one method which can have real utility in diverse areas of qualitative psychology research settings.

Biographies

Joanna Brooks is a Senior Research Fellow in the Centre for Applied Psychological and Health Research at the University of Huddersfield, and a committee member and honorary treasurer of the Qualitative Methods in Psychology section of the British Psychological Society. Her primary research interests focus on applied research topics in health and education settings, usually around chronic health conditions. Jo has a special interest in issues relating to significant others such as family members and close peers, and in using qualitative research methodologies.

Serena McCluskey is a Senior Research Fellow in the Centre for Applied Psychological & Health Research at the University of Huddersfield. She has considerable experience researching the psychosocial influences on health and illness, and her primary interests are focused around work, health and wellbeing. Serena is currently developing an area of research exploring the role of the family in sickness absence and work disability.

Emma Turley is a senior lecturer in psychology at Manchester Metropolitan University. Emma is interested in gender, sexualities and erotic minorities, particularly BDSM, and the ways that these are understood and experienced from a non-pathologising perspective. Other specialist areas of interest include qualitative research methods, especially phenomenological psychology and experiential research, and the use of innovative data collection techniques.

Nigel King is Professor in Applied Psychology, Director of the Centre for Applied Psychological and Health Research and Co-Director of the Institute for Research in Citizenship and Applied Human Sciences at the University of Huddersfield. He is a committee member of the Qualitative Methods in Psychology section of the British Psychological Society. He has a long standing interest in the use of qualitative methods in “real world” research, especially in community health and social care settings, and he is well-known for his publications in this field and his development of innovative research methods. His research interests include professional identities and interprofessional relations in health and social care, psychological aspects of contact with nature, and ethics in qualitative research.

Funding Statement

The “Unpicking the Threads” study presented in Case Study 1 was funded by a grant from Macmillan Cancer Support. The research presented in Case Study 2 was supported by grants from BackCare, NHS Blackburn with Darwen, and the Bupa Foundation.

- Boothby JL, Thorn BE, Overduin LY. Ward LC. Catastrophizing and perceived partner responses to pain. Pain . 2004; 109 :500–6. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Braun V. Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology . 2006; 3 :77–101. ‘. ’. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks J. Young people with diabetes and their peers - an exploratory study of peer attitudes, beliefs, responses and influences . Project report to Diabetes UK, University of Huddersfield; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks J, McCluskey S, King N. Burton K. Illness perceptions in the context of differing work participation outcomes: exploring the influence of significant others in persistent back pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders . 2013; 14 :48. ‘. ’. p. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks J, King N. Wearden A. ‘Couples’ experiences of interacting with outside others in chronic fatigue syndrome: a qualitative study’ Chronic Illness . 2014; 10 :5–17. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Budds K, Locke A. Burr V. Risky business: constructing the “choice” to “delay” motherhood in the British press. Feminist Media Studies . 2013; 13 :132–47. ‘. ’. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butt T. PCP: cognitive or social psychology? In: Scheer JW, editor; Catina A, editor. Empirical constructivism in Europe, the personal construct approach . Psychosozial-Verlag; Giessen: 1996. pp. 58–64. ‘. ’, in. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dornan T, Carroll C. Parboosingh J. An electronic learning portfolio for reflective continuing professional development. Medical Education . 2002; 36 :767–9. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Foster N, Bishop A, Thomas E, Main C, Horne R, Weinman J. Hay E. ‘Illness perceptions of low back pian patients: what are they, do they change, and are they associated with outcome?’ Pain . 2008; 136 :177–87. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S. Redwood S. ‘Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research’ BMC Medical Research Methodology . 2013; 13 :117. p. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Giri, P, Poole, J, Nightingale P. Robertson A. Perceptions of illness and their impact on sickness absence. Occupational Medicine . 2009; 59 :550–5. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldschmidt D, Schmidt L, Krasnik A, Christensen U. Groenvold M. Expectations to and evaluation of a palliative home-care team as seen by patients and carers. Supportive Care in Cancer . 2006; 14 :1232–40. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagger MS. Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychology and Health . 2003; 18 :141–84. ‘. ’. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hammersley M. What’s wrong with ethnography? Routledge; London: 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Self-reported work-related illness and workplace injuries in 2005/6: results from the labour force survey. National Statistics . Health and Safety Executive; United Kingdom: 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoving J, van der Meer M, Volkova A. Frings-Dresen M. Illness perceptions and work participation: a systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health . 2010; 83 :595–605. ‘. ’. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Husserl E. Ideas: general introduction to pure phenomenology . George Allen & Unwin Ltd; London: 1931. (WR Boyce Gibson, trans.) [ Google Scholar ]

- Kent G. Understanding the experiences of people with disfigurements: an integration of four models of social and psychological functioning. Psychology, Health and Medicine . 2000; 5 :117–29. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King N. Doing template analysis. In: Symon G, editor; Cassell C, editor. Qualitative organizational research . Sage; London: 2012. pp. 426–50. ‘. ’, in. [ Google Scholar ]

- King N. What will hatch? A constructivist autobiographical account of writing poetry. Journal of Constructivist Psychology . 2008; 21 :274–87. ‘. ’. [ Google Scholar ]

- King N, Bravington A, Brooks J, Hardy B, Melvin J. Wilde D. ‘ The Pictor technique: a method for exploring the experience of collaborative working’ Qualitative Health Research . 2013; 23 :1138–52. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King N, Carroll C, Newton P. Dornan T. ‘“You can’t cure it so you have to endure it”: the experience of adaptation to diabetic renal disease’ Qualitative Health Research . 2002; 12 :329–46. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King N, Melvin J, Ashby J. Firth J. Community palliative care: role perception. British Journal of Community Nursing . 2010; 15 :91–8. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King N, Melvin J, Brooks J, Wilde D. Bravington A. Unpicking the threads: how specialist and generalist nurses work with patients, carers, other professionals and each other to support cancer and long-term condition patients in the community . Project Report, University of Huddersfield; 2013a. [ Google Scholar ]

- King N. Horrocks C. Interviews in qualitative research . Sage; London: 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kirkby-Geddes E, King N. Bravington A. ‘Social capital and community group participation: examining ‘bridging’ and ‘bonding’ in the context of a healthy living centre in the UK’ Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology . 2013; 23 :271–85. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leonard MT, Cano A. Johansen AB. ‘Chronic pain in a couple’s context: a review and integration of theoretical models and empirical evidence’ The Journal of Pain . 2006; 7 :377–90. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leventhal H, Nerenz D. Steele D. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor S, editors; Singer J, editor. Handbook of psychology and health: social psychological aspects of health . Erlbaum; Hillside, NJ: 1984. pp. 219–52. ‘. ’, in. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leventhal H, Meyer D. Nerenz D. The common-sense representations of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Medical psychology volume 2 . Pergamon; New York: 1980. pp. 7–30. ‘. ’, in. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lockett SH, Hatton J, Turner R, Stubbins C, Hodgekins J. Fowler D. Using a semi-structured interview to explore imagery experienced during social anxiety for clients with a diagnosis of psychosis: an exploratory study conducted within an early intervention for psychosis service. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy . 2012; 40 :55–68. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Madill A, Jordan A. Shirley C. Objectivity and reliability in qualitative research: realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology . 2000; 91 :1–20. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Macdonald KM. The sociology of the professions . Sage; London: 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- Main CJ, Foster N. Buchbinder R. How important are back pain beliefs and expectations for satisfactory recovery from back pain? Best Practice and Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2010; 24 :205–217. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McCluskey S, Brooks J, King N. Burton A. K. ‘ The influence of “significant others” on persistent back pain and work participation: a qualitative exploration of illness perceptions’ BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders . 2011; 12 :236. p. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miles MB. Huberman M. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook . Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R. Buick D. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychology and Health . 2005; 17 :1–16. ‘. ’. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nadin S. Cassell C. Using data matrices. In: Cassell C, editor; Symon G, editor. Essential guide to qualitative research methods in organizational research . Sage; London: 2004. pp. 271–87. ‘. ’, in. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicholas MK. ‘Obstacles to recovery after an episode of low back pain: the “usual suspects” are not always guilty’ Pain . 2010; 148 :363–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ritchie J. Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, editor; Burgess RG, editor. Analyzing qualitative data . Routledge; London: 1994. pp. 173–94. ‘. ’, in. [ Google Scholar ]

- Slade P, Haywood A. King H. ‘A qualitative investigation of women’s experiences of the self and others in relation to their menstrual cycle’ British Journal of Health Psychology . 2009; 14 :127–41. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith JA, Flowers P. Larkin M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research . Sage; London: 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stroud MW, Turner JA, Jensen MP. Cardenas DD. Partner responses to pain behaviours are associated with depression and activity interference among persons with chronic pain and spinal cord injury. The Journal of Pain . 2006; 7 :91–9. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Taylor GW. Ussher JM. Making sense of S&M: a discourse analytic account. Sexualities . 2001; 4 :293–314. ‘. ’. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson AR, Clarke SA, Newell RJ, Gawkrodger DJ. Vitiligo linked to stigmatization in British South Asian women: a qualitative study of the experiences of living with vitiligo. British Journal of Dermatology . 2010; 163 :481–6. and the Appearance Research Collaboration (ARC) ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Turley EL. ‘It started when I barked once when I was licking his boots!’: A phenomenological study of the experience of bondage, discipline, dominance & submission, and sadism & masochism (BDSM) Doctoral Thesis, University of Huddersfield; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Turley EL, King N. Butt T. “It started when I barked once when I was licking his boots!”: a descriptive phenomenological study of the everyday experience of BDSM. Psychology and Sexuality . 2011; 2 :123–36. ‘. ’. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waddington K. Fletcher C. Gossip and emotion in nursing and health-care organizations. Journal of Health Organization and Management . 2005; 19 :378–94. ‘. ’. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wynn P. Money A. ‘Qualitative research and occupational medicine’ Occupational Medicine . 2009; 59 :138–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- {{item.title}} {{item.title}} 0" aria-label="Find options under this page" @click="mobchildshow(true, item.title)" class="more-menu">

- {{subitem.title}}

Template Analysis

Welcome to the template analysis website.

This website, designed by Professor Nigel King , provides a resource for those using an approach to qualitative data analysis known as ‘template analysis’ (TA). Whether you are new to this kind of analysis or a veteran qualitative researcher, it is hoped the website will be of use to you. This resource has been designed to be of relevance to researchers from any social scientific discipline. Much of the content uses examples from organizational and health psychology, but by contributing to the resource's Facebook page you can explore template analysis in relation to your own discipline.

Professor Nigel King

Applied Psychology, Department of Behavioural Sciences

'I am a Professor in Applied Psychology in the Department of Behavioural Sciences at the University of Huddersfield. Having written widely on innovation and change in organisations, my recent empirical work has focused on primary healthcare settings. However, my interests and publications also explore the experience of chronic illness, professional identities in health and social care, and paranormal beliefs and experiences. I am particularly interested in phenomenology and its implications for psychology. My long-standing interest in qualitative approaches in psychology draws together these diverse strands.'

Introduction

Professor Nigel King has taught and written about qualitative methods in psychology and allied disciplines for over 10 years, and has used them extensively in his own research. Whilst there is a large quantity of literature on thematic approaches in general, there is relatively little specifically on the use of the template style, the main sources being literature by Crabtree and Miller and Nigel.

This website has been developed to help answer queries on template analysis and to create a space for researchers to discuss and explore the use of template analysis in relation to their work. This material shows how template analysis can not only be used to introduce people to qualitative data analysis, but also to carry out more sophisticated and complex research.

Visit the FAQs section for further information.

What is template analysis?

A concise description of the approach and how it relates to other types of qualitative data analysis

The technique in detail

A step-by-step practical guide to using the approach.

Real examples of how the approach has been used.

Methodological literature on template analysis and similar approaches, examples of papers and reports and some general references to qualitative methods in psychology and other disciplines.

Other sites of potential interest.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Huddersfield, Centre for Applied Psychological and Health Research, Institute for Research in Citizenship and Applied Human Sciences , Huddersfield , UK.

- 2 Manchester Metropolitan University, Department of Health Professions , Manchester , UK.

- PMID: 27499705

- PMCID: PMC4960514

- DOI: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Thematic analysis is widely used in qualitative psychology research, and in this article, we present a particular style of thematic analysis known as Template Analysis. We outline the technique and consider its epistemological position, then describe three case studies of research projects which employed Template Analysis to illustrate the diverse ways it can be used. Our first case study illustrates how the technique was employed in data analysis undertaken by a team of researchers in a large-scale qualitative research project. Our second example demonstrates how a qualitative study that set out to build on mainstream theory made use of the a priori themes (themes determined in advance of coding) permitted in Template Analysis. Our final case study shows how Template Analysis can be used from an interpretative phenomenological stance. We highlight the distinctive features of this style of thematic analysis, discuss the kind of research where it may be particularly appropriate, and consider possible limitations of the technique. We conclude that Template Analysis is a flexible form of thematic analysis with real utility in qualitative psychology research.

Keywords: Pictor technique; Template Analysis; a priori themes; applied research; group data analysis; qualitative research; thematic analysis.

PubMed Disclaimer

Example of a ‘Pictor’ chart.

Case study 1 - initial…

Case study 1 - initial template.

Case study 1 - version…

Case study 1 - version 8 template (top theme 1 only shown).

Case study 2 - final…

Case study 2 - final version template.

Case study 3 - initial…

Case study 3 - initial template.

Case study 3 – final…

Case study 3 – final template.

Similar articles

- Scientific models for qualitative research: a textual thematic analysis coding system - part 2. Gildberg FA, Wilson R. Gildberg FA, et al. Nurse Res. 2023 Jul 13. doi: 10.7748/nr.2023.e1893. Online ahead of print. Nurse Res. 2023. PMID: 37440301

- Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Kiger ME, Varpio L. Kiger ME, et al. Med Teach. 2020 Aug;42(8):846-854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030. Epub 2020 May 1. Med Teach. 2020. PMID: 32356468

- Meta-Synthesis on Migraine Management. Minen MT, Anglin C, Boubour A, Squires A, Herrmann L. Minen MT, et al. Headache. 2018 Jan;58(1):22-44. doi: 10.1111/head.13212. Epub 2017 Nov 21. Headache. 2018. PMID: 29159874 Review.

- Finding common ground in team-based qualitative research using the convergent interviewing method. Driedger SM, Gallois C, Sanders CB, Santesso N. Driedger SM, et al. Qual Health Res. 2006 Oct;16(8):1145-57. doi: 10.1177/1049732306289705. Qual Health Res. 2006. PMID: 16954531

- The role of computer software in the analysis of qualitative data: efficient clerk, research assistant or Trojan horse? Morison M, Moir J. Morison M, et al. J Adv Nurs. 1998 Jul;28(1):106-16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00768.x. J Adv Nurs. 1998. PMID: 9687137 Review.

- Towards Sustainable Solid Waste Management Systems: Empirical Evidence From Northern Malawi. Kamanga TW, Chitete MM, Kamanga BC, Damazio C, Yafeti Y, Sibande M. Kamanga TW, et al. Environ Health Insights. 2024 May 31;18:11786302241255800. doi: 10.1177/11786302241255800. eCollection 2024. Environ Health Insights. 2024. PMID: 38828045 Free PMC article.

- Acceptability of the Venting Wisely pathway for use in critically ill adults with hypoxaemic respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a qualitative study protocol. Krewulak KD, Knight G, Irwin A, Morrissey J, Stelfox HT, Bagshaw SM, Zuege D, Roze des Ordons A, Fiest K, Parhar KKS. Krewulak KD, et al. BMJ Open. 2024 May 28;14(5):e075086. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075086. BMJ Open. 2024. PMID: 38806421 Free PMC article.

- Towards Integrated Care for the Elderly: Exploring the Acceptability of Telemonitoring for Hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes Management. Mihevc M, Lukančič MM, Črt Z, Potočnik TV, Šter MP, Klemenc-Ketiš Z, Susič AP. Mihevc M, et al. Int J Integr Care. 2024 May 15;24(2):16. doi: 10.5334/ijic.7621. eCollection 2024 Apr-Jun. Int J Integr Care. 2024. PMID: 38765055 Free PMC article.

- A protocol for a critical realist systematic synthesis of interventions to promote pupils' wellbeing by improving the school climate in low- and middle-income countries. Abbott P, Shanks R, Stanley I, D'Ambruoso L. Abbott P, et al. PLoS One. 2024 May 15;19(5):e0286489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286489. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 38748720 Free PMC article.

- The TELEhealth Shared decision-making Coaching and Navigation in Primary carE (TELESCOPE) intervention: a study protocol for delivering shared decision-making for lung cancer screening by patient navigators. Tan NQP, Lowenstein LM, Douglas EE, Silva J, Bershad JM, An J, Shete SS, Steinberg MB, Ferrante JM, Clark EC, Natale-Pereira A, Sahu NN, Hastings SE, Hoffman RM, Volk RJ, Kinney AY. Tan NQP, et al. Res Sq [Preprint]. 2024 Apr 22:rs.3.rs-4254047. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4254047/v1. Res Sq. 2024. PMID: 38746205 Free PMC article. Preprint.

- Boothby JL, Thorn BE, Overduin LY. Ward LC. Catastrophizing and perceived partner responses to pain. Pain. 2004;109:500–6. ‘. ’. - PubMed

- Braun V. Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. ‘. ’.

- Brooks J. Young people with diabetes and their peers - an exploratory study of peer attitudes, beliefs, responses and influences. Project report to Diabetes UK, University of Huddersfield; 2014.

- Brooks J, McCluskey S, King N. Burton K. Illness perceptions in the context of differing work participation outcomes: exploring the influence of significant others in persistent back pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2013;14:48. ‘. ’. p. - PMC - PubMed

- Brooks J, King N. Wearden A. ‘Couples’ experiences of interacting with outside others in chronic fatigue syndrome: a qualitative study’. Chronic Illness. 2014;10:5–17. - PubMed

Related information

- Cited in Books

Grants and funding

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- DOI: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

- Corpus ID: 6249522

The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research

- J. Brooks , S. McCluskey , +1 author N. King

- Published in Qualitative Research in… 2 September 2014

1,027 Citations

Celebrations amongst challenges: considering the past, present and future of the qualitative methods in psychology section of the british psychology society, template analysis in business and management research, qualitative research methodology: a neo-empiricist perspective, criteria for qualitative methods in human reliability analysis, lived experiences of a community: merging interpretive phenomenology and community-based participatory research, what are interviews for a qualitative study of employment interview goals and design, using template and matrix analysis, explaining “explaining” : a phenomenological study of meaning making, analyzing the effects of incivility beyond workplaces, one size fits all what counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis, 58 references, objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies., interpretative phenomenological analysis: theory, method and research, using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research, gossip and emotion in nursing and health-care organizations., 'it started when i barked once when i was licking his boots' : a phenomenological study of the experience of bondage, discipline, dominance & submission, and sadism & masochism (bdsm), making sense of s&m: a discourse analytic account, what will hatch a constructivist autobiographical account of writing poetry, a meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations, using a semi-structured interview to explore imagery experienced during social anxiety for clients with a diagnosis of psychosis: an exploratory study conducted within an early intervention for psychosis service., the influence of 'significant others' on persistent back pain and work participation: a qualitative exploration of illness perceptions.

- Highly Influential

Related Papers

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Practical thematic...

Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis

- Related content

- Peer review

- on behalf of the Coproduction Laboratory

- 1 Dartmouth Health, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 2 Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, Lebanon, NH, USA

- 3 Center for Primary Care and Public Health (Unisanté), Lausanne, Switzerland

- 4 Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare, School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

- 5 Highland Park, NJ, USA

- 6 Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA

- Correspondence to: C H Saunders catherine.hylas.saunders{at}dartmouth.edu

- Accepted 26 April 2023