quantity surveying Recently Published Documents

Total documents.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Sustainable construction and the versatility of the quantity surveying profession in Singapore

PurposeThe changing role of quantity surveyors in the new paradigm of sustainable construction requires studies into new competencies and skills for the profession. The impact of sustainable construction on quantity surveying services, engagement and how they manage challenges provided an indication of the success indicators of the quantity surveying profession in meeting the sustainable construction needs.Design/methodology/approachA five-point Likert scale was developed from the list of quantity surveying firms in Singapore. An 85% response rate from 60 quantity surveying firms contacted in this study provided 51 responses. Descriptive statistics and factor analysis were employed to evaluate the findings.FindingsThe factor analysis categorised the drivers derived from the literature into awareness of sustainable construction, adversarial role on green costing; carbon cost planning; valuing a sustainable property; common knowledge of sustainable construction; and lack of experience in sustainable construction.Social implicationsThe research findings supported the idea of increased sustainable construction skills in quantity surveying education, research and training.Originality/valueThe dearth of quantity surveyors with sustainable construction experience must focus on quantity surveying professional bodies and higher education. The quantity surveying profession needs reskilling in green costing and carbon cost planning to meet the needs of sustainable construction.

Quantity Surveying Practice

Quantity surveying profession and its prospects in nigeria.

The study assessed the prospects of the Quantity Surveying profession in Nigeria. The study identified and evaluated the level of performance of the identified functions performed by the quantity surveyors in the Nigerian Construction industry. The study reveals that there is a high level of performance of the basic functions of the quantity surveyors which include feasibility and viability studies, contract documentation, life cycle costing, preliminary cost advice, etc. The study also examined the factors militating against the effective performance of the quantity surveyor’s functions in the Nigerian Construction industry. The study identified and presented some possible factors militating against the performance of Quantity Surveying functions and some anticipated measures to enhance the quantity Surveying profession for evaluation by the respondents using structured questionnaires. The data collected were analyzed with SPSS version 23 using frequencies and mean item scores. The study revealed some major factors militating against the effective performance of the quantity surveying profession in the Nigerian Construction industry like widespread corruption in Nigeria with a mean score of 4.53, obsolete curriculum and inadequacy in modern equipment with a mean score of 4.41, professional rivalry from kindred profession with a mean score of 4.35, level of adoption of UT with mean a score of 4.32, and inadequacies in academic and professional training with a mean score of 4.18 among others. The study equally revealed some important measures requiring implementation to enhance the quantity of Surveying profession in Nigeria like a clear delineation in professional functions in the construction industry to curb professional rivalry with a mean score of 4.35, reviewing the curriculum of Tertiary Institutions with a mean score of 4.24, improving professional skills through continuing professional development with a mean score of 4.15, improving technological applications in the execution of Quantity Surveying functions with a mean score of 3.91 and professional certification in specialized areas with a mean score of 3.85.

Transdisciplinary service-learning for construction management and quantity surveying students

The transformation of higher education in South Africa has seen higher education institutions become more responsive to community matters by providing institutional support for service-learning projects. Despite service-learning being practised in many departments at the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT), there is a significant difference in the way service-learning is perceived by academics and the way in which it should be supported within the curriculum. This article reflects on a collaborative transdisciplinary service-learning project at CPUT that included the Department of Construction Management and Quantity Surveying and the Department of Urban and Regional Planning. The aim of the transdisciplinary service-learning project was for students to participate in an asset-mapping exercise in a rural communal settlement in the Bergrivier municipality in the Western Cape province of South Africa. In so doing students from the two departments were gradually inducted into the community. Once inducted, students were able to identify the community’s most urgent needs. During community engagement students from each department were paired together. This allowed transdisciplinary learning to happen with the exploration of ideas from the perspectives of both engineering and urban planning students. Students were able to construct meaning beyond their discipline. Cooperation and synergy between the departments allowed mutual, interchangeable, cooperative interaction with community members. Outcomes for the transdisciplinary service-learning project and the required commitment from students are discussed.

Admission Points Score to Predict Undergraduate Performance - Comparing Quantity Surveying vs. Real Estate

Quantity surveying and bim 5d. its implementation and analysis based on a case study approach in spain, factors influencing the adoption of building information modelling (bim) in the south african construction and built environment (cbe) from a quantity surveying perspective.

Abstract The construction industry has often been described as stagnant and out-of-date due to the lack of innovation and innovative work methods to improve the industry (WEF, 2016; Ostravik, 2015). The adoption of Building Information Modelling (BIM) within the construction industry has been relatively slow (Cao et al., 2017), particularly in the South African Construction and Built Environment (CBE) (Allen, Smallwood & Emuze, 2012). The purpose of this study was to determine the critical factors influencing the adoption of BIM in the South African CBE, specifically from a quantity surveyor’s perspective, including the practical implications. The study used a qualitative research approach grounded in a theoretical framework. A survey questionnaire was applied to correlate the interpretation of the theory with the data collected (Naoum, 2007). The study was limited to professionals within the South African CBE. The study highlighted that the slow adoption of BIM within the South African CBE was mainly due to a lack of incentives and subsequent lack of investment towards the BIM adoption. The study concluded that the South African CBE operated mainly in silos without centralised coordination. The BIM adoption was only organic. Project teams were mostly project orientated, seeking immediate solutions, and adopted the most appropriate technologies for the team’s composition. The study implies that the South African CBE, particularly the Quantity Surveying profession, still depends heavily on other role-players in producing information-rich 3D models. Without a centralised effort, the South African Quantity Surveying professionals will continue to adopt BIM technology linearly to the demand-risk ratio as BIM maturity is realised in the South African CBE.

The impact of environmental turbulence on the strategic decision-making process in Irish quantity surveying (QS) professional service firms (PSFs)

External marketing relationship practice of quantity surveying firms in the selected states in nigeria.

It has been established that marketing is very significant to the success of any organization, especially in a competitive environment. In the Quantity surveying profession, marketing might be more relevant than other professions because it is less known. The significance of marketing and competitive business environment calls for effective marketing practice by Quantity Surveying Firms (QSFs). One of the effective ways is to build a strong external marketing relationship, which exists between a firm and its client. Therefore, this paper investigated the external marketing relationship practice of QSFs with a view to enhancing firms’ productivity and client satisfaction. Forty-six (46) registered QSFs and fifty-nine (59) corporate clients in Lagos, Oyo, and Ondo States were assessed through questionnaire survey. Data were collected on the attributes of parties involved in external marketing. The collected data were analysed using Mean Item Scores (MIS) and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The results reveal important attributes of clients to include “pay on time (MS=4.59)”, “willingness and readiness to take advice from the firm (MS=4.59)”, and “make expectations known clearly to the firm (MS=4.54)”. From the findings, clients averagely displayed these attributes. The result of ANOVA shows that firms viewed the importance of these clients’ attributes in the same way at p>0.05 except for one of these attributes (making expectations known clearly to the firm), which firms viewed its importance differently at p<0.05. Furthermore, results show the important attributes of firms to include: “ability to give clients value for their money (MS=4.51)”, “knowing clients’ requirements (MS=4.51)”, and “being attentive (MS=4.47)’. Findings show that these attributes were adequately displayed by QSFs. The perceptions of clients on the importance of these firms’ attributes were the same at p>0.05. The study concluded by establishing attributes for strong external marketing relationship to include: “readiness of a client to take advice from the firm”, “ability of a client to pay on time”, “ability of a firm to satisfy the client”, and “knowing the client’s requirements”. The study recommended that QSFs and clients should endeavour to possess and display these attributes for the enhancement of service delivery in terms of firms’ productivity and clients’ satisfaction. Keywords: Attributes, Clients, External Marketing Relationship, Quantity Surveying Firms

Export Citation Format

Share document.

Integrating quality into quantity: survey research in the era of mixed methods

- Published: 18 April 2015

- Volume 50 , pages 1213–1231, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Sergio Mauceri 1

1707 Accesses

7 Citations

Explore all metrics

As widely recognized during the golden age of survey research thanks to the work of the Columbia school, the use of mixed strategies allows survey research to overcome its limitations by incorporating the advantages of qualitative approaches rather than seeking alternative methods. The need to re-think survey research before embarking on this course impelled the author to undertake a critical analysis of one of the survey’s most important assumptions, proposing a shift from standardization of stimulus to standardization of meanings in order to anchor the requirement of answer comparability on a more solid basis. This proposal for rapprochement with qualitative research is followed by a more detailed section in which the author distinguishes four different types of mixed survey strategies, combining two criteria (time order and function of qualitative procedures). The most significant parts of the constructed typology are then brought together in a model called the multilevel integrated survey approach. This methodological model is concretely illustrated in an empirical study of homophobic prejudice among teenagers. The example shows how in research practice analytical mixed strategies can be creatively combined in the same survey research design, contributing to improvements in data quality and the relevance of research findings.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Mixed-Mode Surveys and Data Quality

Why Survey Methodology Needs Sociology and Why Sociology Needs Survey Methodology

Using Multi-Informant Designs to Address Key Informant and Common Method Bias

Among others, in alphabetical order: Paul Beatty, Norman M. Bradburn, Charles L. Briggs, Frederick Conrad, Hanneke Houtkoop-Seenstra, Brigitte Jordan, Douglas Maynard, Hugh Mehan, Elliot G. Mishler, Nora Cate Schaeffer, Michael F. Schober, Norbert Schwarz, Howard Schuman, Lucy Suchman, Seymour Sudman, Judith M. Tanur.

Strictly speaking, then, the term ‘methods’ (even in the expression ‘Mixed methods’) should be discarded because it conveys the idea that qualitative and quantitative methods are independent and in some ways mutually exclusive. As the pragmatist philosopher John Dewey pointed out ( 1938 ), the logic of social-scientific research (the method) is unique and always follows the same criteria of scientific validation and the same general procedural steps. For this reason, it would be preferable to speak of ‘mixed research’ (Onwuegbuzie 2007 ), ‘mixed methodology’ (Tashakkori and Teddlie 2003 ), or, as in this article, mixed strategies.

It is important not to confuse deviant cases with deviant findings, introduced in the integrative in-depth survey strategy. Deviant cases are residual exceptions to confirmed hypotheses and empirical regularities, while deviant findings are empirical regularities that contradict the researcher’s theoretical expectations and thus concern a preponderant number of cases.

Barton, A.H.: Bringing society back in: survey research and macro-methodology. Am. Behav. Soc. 12 (2), 1–9 (1968)

Article Google Scholar

Barton, A.H.: Paul Lazarsfeld and applied social research. Soc. Sci. Hist. 3 (3–4), 4–44 (1979)

Blaikie, N.W.H.: A critique of the use of triangulation in social research. Qual. Quant. 25 , 115–136 (1991)

Bourdieu, P.: Réponses. Pour une anthropologie réflexive. Editions de Seuil, Paris (1992)

Google Scholar

Campbell, D.T., Fiske, D.W.: Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. LVI 2 , 81–105 (1959)

Campelli, E.: Da un luogo comune. Introduzione alla metodologia delle scienze sociali (Nuova edizione). Carocci, Roma (2009)

Capecchi, V.: Il contributo di Lazarsfeld alla metodologia sociologica. In: Campelli, E., Fasanella, A., Lombardo, C., Paul Felix Lazarsfeld: un “classico” marginale, Milano: Angeli (Sociologia e ricerca sociale, XX, 58/59, pp. 35–82) (1999)

Creswell, J.W.: Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage, London (2008)

Denzin, N.K.: The Research Act. A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York (1978)

Dewey, J.: Logic, the Theory of Inquiry. Henry Holt and Co, New York (1938)

Fielding, N.G., Schreier, M.: Introduction: on the compatibility between qualitative and quantitative research methods. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 2 (1), 2204 (2001)

Fowler Jr, F.J., Mangione, T.W.: Standardized Survey Interviewing. Minimizing Interviewer-Related Error. Sage, London (1990)

Galtung, J.: Theory and Methods of Social Research. Universitet Forlaget, Oslo (1967)

Gobo, G., Mauceri, S.: Constructing Survey Data. An Interactional Approach. Sage, London (2014)

Goode, W., Hatt, P.K.: Methods in Social Research. McGraw Hill, New York (1952)

Hammersley, M.: Some notes on the terms ‘validity’ and ‘reliability’. Br. Educ. Res. J. 13 (1), 73–81 (1987)

Hughes, J.A.: The Philosophy of Social Research. Longman, New York (1980)

Hyman, H.H., Coob, W.J., Fedelman, J.F., Hart, C.W., Stember, C.H.: Interviewing in Social Research. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1954)

Jahoda, M., Lazarsfeld, P.F., Zeisel, H.: Die Arbeitslosen von Marienthal. Hitzel, Leipzig (1933)

Jahoda, M., Lazarsfeld, P.F., Zeisel, H.: Marienthal. Sociography of an Unemployed Community. Aldline p.c, Hawthorne (1971)

Johnson, R.B., Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Turner, L.A.: Toward a definition of mixed methods research. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1 (2), 112–133 (2007)

Lazarsfeld, P.F.: The art of asking why. Three principles underlying the formulation of questionnaires. Natl. Mark. Rev. 1 (1), 32–43 (1935)

Lazarsfeld, P.F.: The controversy over detailed interviews. An offer for negotiation. Public Opin. Q. 1 , 38–60 (1944)

Lazarsfeld, P.F., Barton, A.: Some functions of qualitative analysis in social research. Frankf. Bertrage zur Sociol. 1 , 321–361 (1955)

Lazarsfeld, P.F., Berelson, B., Gaudet, H.: The People’s Choice. How the Voter Makes Up his Mind in a Presidential Campaign. Columbia University Press, New York (1944)

Lazarsfeld, P.F., Menzel, H.: On the Relation Between Individual and Collective Properties. In: Etzioni, A., Sociological, A. (eds.) Reader on Complex Organizations, pp. 499–516. Rinehart & Winston, New York (1961)

Lazarsfeld, P.F., Rosenberg, M. (eds.): The Language of Social Research. A Reader in Methodology of Social Research. Free Press, New York (1955)

Leech, N.L., Onwuegbuzie, A.J.: A typology of mixed methods research designs. Qual. Quant. 43 , 265–275 (2009)

Maynard, D.W., Houtkoop-Steenstra, H., Schaeffer, N.C., van der Zouwen, J. (eds.): Standardization and Tacit Knowledge. Interaction and Practice in the Survey Interview. Wiley, New York (2002)

Mauceri, S.: Per la qualità del dato nella ricerca sociale. Strategie di progettazione e conduzione dell’intervista con questionario. Franco Angeli, Milano (2003)

Mauceri, S.: Ri-scoprire l’analisi dei casi devianti. Una strategia metodologica di supporto dei processi teorico-interpretativi nella ricerca sociale di tipo standard. Sociol. e Ricerca Soc. 87 , 109–157 (2008). XXVIII

Mauceri, S.: Per una survey integrata e multilivello. Le lezioni dimenticate della Columbia School. Sociol. e ricerca sociale 99 , 22–65 (2012). XXXIII

Mauceri, S.: Mixed strategies for improving data quality: the contribution of qualitative procedures to survey research. Qual. Quant. 5 , 2773–2790 (2014a). XLVIII

Mauceri, S.: Discontent in call centres: a national multilevel and integrated survey on quality of working life among call handlers. SAGE Res. Methods Cases (2013a). doi: 10.4135/9781446-27305013509181 . (2014b)

Mauceri, S.: Teenage homophobia: a multilevel and integrated survey approach to the social construction of prejudice in high school. SAGE Res. Methods Cases (2013b). doi: 10.4135/9781446-27305013503433 . (2014c)

Mauceri, S.: Omofobia come costruzione sociale. Processi generativi del pregiudizio in età adolescenziale. FrancoAngeli, Milano (2015)

Merton, R.K.: Social Theory and Social Structure. The Free Press, Glencoe (1949)

Merton, R.K., Kendall, P.L.: The focused interview. Am. J. Sociol. 51 , 541–557 (1946)

Morgan, D.L.: Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qual. Health Res. 8 , 362–376 (1998)

Morgan, D.L.: Combining qualitative and quantitative methods paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. J. Mixed Methods Res. 1 , 48–76 (2007)

Newman, I., Ridenour, C.S., Newman, C., DeMarco, G.M.P., Jr.: A typology of research purposes and its relationship to mixed methods. In: Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C. (eds.) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, pp. 167–188. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (2003)

Onwuegbuzie, A.J.: Mixed methods research in sociology and beyond. In: Ritzer, G. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Sociology, vol. VI, pp. 2978–2981. Blackwell, Oxford (2007)

Pawson, R.: A Measure for Measures: A Manifesto for Empirical Sociology. Routledge, London (1989)

Book Google Scholar

Sieber, S.D.: The integration of fieldwork and survey methods. Am. J. Sociol. 6 , 1335–1359 (1973)

Suchman, L., Jordan, B.: Interactional troubles in face-to-face survey interviews. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 85 (409), 232–254 (1990)

Teddlie, C., Tashakkori, A.: Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C. (eds.) (pp. 3–50) (2003)

Tashakkori, A., Teddlie, C. (eds.): Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (2003)

Trow, M.: Comment on ‘participant observation and interviewing: a comparison’. Hum. Organ. 16 (Fall), 33–35 (1957)

Webb, E.J., Campbell, D.T., Schwartz, R.D., Sechrest, L.: Unobtrusive Measures: Nonreactive Research in the Social Sciences. Rand McNally, Chicago (1966)

Zelditch Jr, M.: Some methodological problems of field studies. Am. J. Sociol. 67 (March), 566–576 (1962)

Download references

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Communication and Social Research, Sapienza University of Rome, C.so d’Italia 38/a, 00198, Rome, Italy

Sergio Mauceri

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sergio Mauceri .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Mauceri, S. Integrating quality into quantity: survey research in the era of mixed methods. Qual Quant 50 , 1213–1231 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0199-8

Download citation

Published : 18 April 2015

Issue Date : May 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0199-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mixed methodology

- Survey research

- Multilevel approach

- Columbia school

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, a framework for assessing quantity surveyors’ competence.

Benchmarking: An International Journal

ISSN : 1463-5771

Article publication date: 1 October 2018

The purpose of this paper is to develop a conceptual framework for assessing quantity surveyors’ competence level.

Design/methodology/approach

Delphi survey research approach was adopted for the study. This involved a survey of panel of experts, constituted among registered quantity surveyors in Nigeria, and obtaining from them a consensus opinion on the issues relating to the assessment of quantity surveyors’ competence. In total, 27 out of the shortlisted 38 member panel provided valid results in the two rounds of Delphi survey conducted. A conceptual framework linking educational training, professional capability and professional development is developed.

The findings establish the ratings of the identified three competence criteria. On a scale of 0–100 percent rating, educational training was scored 34.04 percent, professional capability 45.22 percent and professional development 20.74 percent.

Originality/value

The proposed framework provide a conceptual approach in assessing quantity surveyor overall competence. Specifically, it demonstrates the significance of the identified three competence criteria groupings in the training, practice and development of quantity surveying profession. It could therefore serves as foundation of on how quantity surveyors are trained, developed and evaluated.

- Quantity surveyor

Dada, J.O. and Jagboro, G.O. (2018), "A framework for assessing quantity surveyors’ competence", Benchmarking: An International Journal , Vol. 25 No. 7, pp. 2390-2403. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-05-2017-0121

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Quantity Surveying

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Construction Management Follow Following

- Construction Project Management Follow Following

- Procurement Follow Following

- Project Risk Management Follow Following

- Tendering Follow Following

- Construction Economics Follow Following

- Construction Technology Follow Following

- QUANTITY SURVEYING AND CONSTRUCTION MANAGMENT Follow Following

- Value Management Follow Following

- Procurement Management Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- A/B Monadic Test

- A/B Pre-Roll Test

- Key Driver Analysis

- Multiple Implicit

- Penalty Reward

- Price Sensitivity

- Segmentation

- Single Implicit

- Category Exploration

- Competitive Landscape

- Consumer Segmentation

- Innovation & Renovation

- Product Portfolio

- Marketing Creatives

- Advertising

- Shelf Optimization

- Performance Monitoring

- Better Brand Health Tracking

- Ad Tracking

- Trend Tracking

- Satisfaction Tracking

- AI Insights

- Case Studies

quantilope is the Consumer Intelligence Platform for all end-to-end research needs

What Are Quantitative Survey Questions? Types and Examples

Table of contents:

- Types of quantitative survey questions - with examples

- Quantitative question formats

- How to write quantitative survey questions

- Examples of quantitative survey questions

Leveraging quantilope for your quantitative survey

In a quantitative research study brands will gather numeric data for most of their questions through formats like numerical scale questions or ranking questions. However, brands can also include some non-quantitative questions throughout their quantitative study - like open-ended questions, where respondents will type in their own feedback to a question prompt. Even so, open-ended answers can be numerically coded to sift through feedback easily (e.g. anyone who writes in 'Pepsi' in a soda study would be assigned the number '1', to look at Pepsi feedback as a whole). One of the biggest benefits of using a quantitative research approach is that insights around a research topic can undergo statistical analysis; the same can’t be said for qualitative data like focus group feedback or interviews. Another major difference between quantitative and qualitative research methods is that quantitative surveys require respondents to choose from a limited number of choices in a close-ended question - generating clear, actionable takeaways. However, these distinct quantitative takeaways often pair well with freeform qualitative responses - making quant and qual a great team to use together. The rest of this article focuses on quantitative research, taking a closer look at quantitative survey question types and question formats/layouts.

Back to table of contents

Types of dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139745">quantitative survey questions - with examples

Quantitative questions come in many forms, each with different benefits depending on dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139784">your dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139740">market research objectives. Below we’ll explore some of these dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139745">quantitative dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139785">survey question dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-menu-id-param="menu_term_281139785" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139785"> types, which are commonly used together in a single survey to keep things interesting for dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents . The style of questioning used during dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139739">quantitative dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139750">data dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-menu-id-param="menu_term_281139750" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139750"> collection is important, as a good mix of the right types of questions will deliver rich data, limit dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondent fatigue, and optimize the dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139757">response rate . dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139742">Questionnaires should be enjoyable - and varying the dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139755">types of dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-menu-id-param="menu_term_281139755" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139755">quantitative research dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139755"> questions used throughout your survey will help achieve that.

Descriptive survey questions

dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139763">Descriptive research questions (also known as usage and attitude, or, U&A questions) seek a general indication or prediction about how a dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139773">group of people behaves or will behave, how that group is characterized, or how a group thinks.

For example, a business might want to know what portion of adult men shave, and how often they do so. To find this out, they will survey men (the dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139743">target audience ) and ask descriptive questions about their frequency of shaving (e.g. daily, a few times a week, once per week, and so on.) Each of these frequencies get assigned a numerical ‘code’ so that it’s simple to chart and analyze the data later on; daily might be assigned ‘5’, a few times a week might be assigned ‘4’, and so on. That way, brands can create charts using the ‘top two’ and ‘bottom two’ values in a descriptive question to view these metrics side by side.

Another business might want to know how important local transit issues are to residents, so dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139745">quantitative survey questions will allow dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents to indicate the degrees of opinion attached to various transit issues. Perhaps the transit business running this survey would use a sliding numeric scale to see how important a particular issue is.

Comparative survey questions

dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139782">Comparative research questions are concerned with comparing individuals or groups of people based on one or more variables. These questions might be posed when a business wants to find out which segment of its dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139743">target audience might be more profitable, or which types of products might appeal to different sets of consumers.

For example, a business might want to know how the popularity of its chocolate bars is spread out across its entire customer base (i.e. do women prefer a certain flavor? Are children drawn to candy bars by certain packaging attributes? etc.). Questions in this case will be designed to profile and ‘compare’ segments of the market.

Other businesses might be looking to compare coffee consumption among older and younger consumers (i.e. dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139741">demographic segments), the difference in smartphone usage between younger men and women, or how women from different regions differ in their approach to skincare.

Relationship-based survey questions

As the name suggests, relationship-based survey questions are concerned with the relationship between two or more variables within one or more dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139741">demographic groups. This might be a dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139759">causal link between one thing and the other - for example, the consumption of caffeine and dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents ’ reported energy levels throughout the day. In this case, a coffee or energy drink brand might be interested in how energy levels differ between those who drink their caffeinated line of beverages and those who drink decaf/non-caffeinated beverages.

Alternatively, it might be a case of two or more factors co-existing, without there necessarily being a dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139759">causal link - for example, a particular type of air freshener being more popular amongst a certain dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139741">demographic (maybe one that is controlled wirelessly via Bluetooth is more popular among younger homeowners than one that’s plugged into the wall with no controls). Knowing that millennials favor air fresheners which have options for swapping out scents and setting up schedules would be valuable information for new product development.

Advanced method survey questions

Aside from descriptive, comparative, and relationship-based survey questions, brands can opt to include advanced methodologies in their quantitative dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139742">questionnaire for richer depth. Though advanced methods are more complex in terms of the insights output, quantilope’s Consumer Intelligence Platform automates the setup and analysis of these methods so that researchers of any background or skillset can leverage them with ease.

With quantilope’s pre-programmed suite of 12 advanced methodologies , including MaxDiff , TURF , Implicit , and more, users can drag and drop any of these into a dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139742">questionnaire and customize for their own dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139740">market research objectives.

For example, consider a beverage company that’s looking to expand its flavor profiles. This brand would benefit from a MaxDiff which forces dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents to make tradeoff decisions between a set of flavors. A dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondent might say that coconut is their most-preferred flavor, and lime their least (when in a consideration set with strawberry), yet later on in the MaxDiff that same dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondent may say Strawberry is their most-preferred flavor (over black cherry and kiwi). While this is just one example of an advanced method, instantly you can see how much richer and more actionable these quantitative metrics become compared to a standard usage and attitude question .

Advanced methods can be used alongside descriptive, comparison, or relationship questions to add a new layer of context wherever a business sees fit. Back to table of contents

Quantitative question formats

So we’ve covered the kinds of dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139736">quantitative research questions you might want to answer using dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139740">market research , but how do these translate into the actual format of questions that you might include on your dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139742">questionnaire ?

Thinking ahead to your reporting process during your dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139742">questionnaire setup is actually quite important, as the available chart types differ among the types of questions asked; some question data is compatible with bar chart displays, others pie charts, others in trended line graphs, etc. Also consider how well the questions you’re asking will translate onto different devices that your dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents might be using to complete the survey (mobile, PC, or tablet).

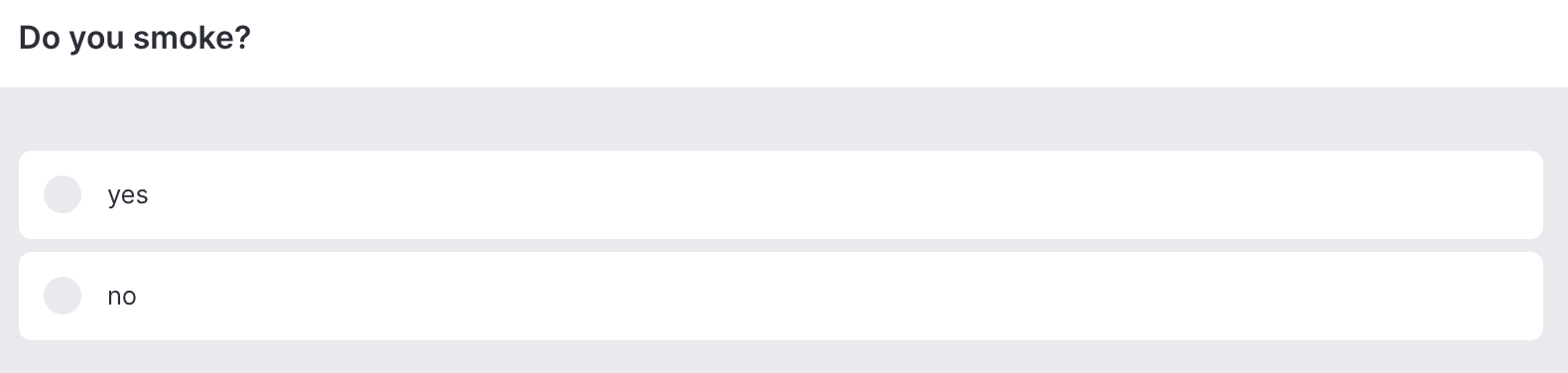

Single Select questions

Single select questions are the simplest form of quantitative questioning, as dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents are asked to choose just one answer from a list of items, which tend to be ‘either/or’, ‘yes/no’, or ‘true/false’ questions. These questions are useful when you need to get a clear answer without any qualifying nuances.

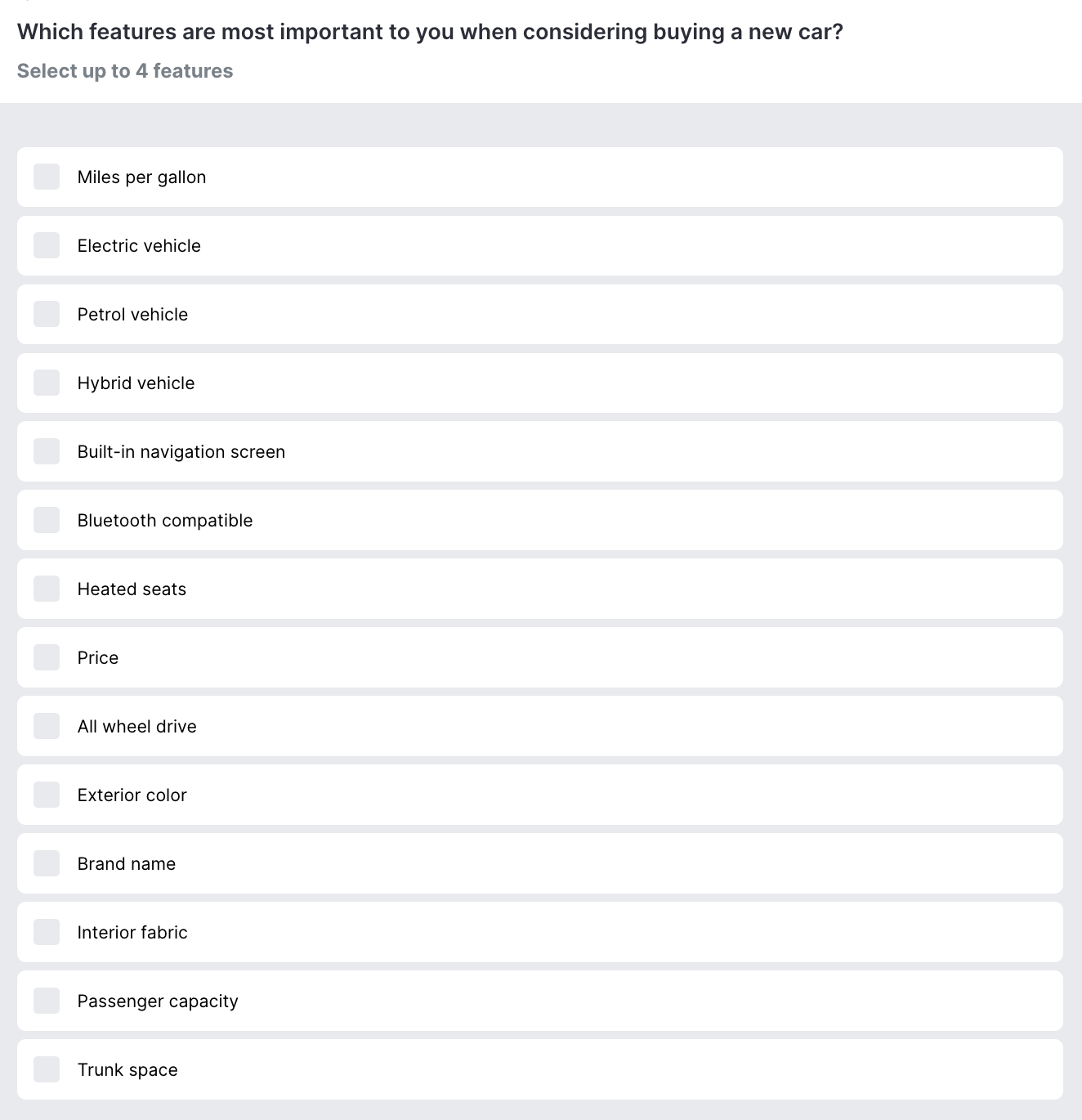

Multi-select questions

Multi-select questions (aka, dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139767">multiple choice ) offer more flexibility for responses, allowing for a number of responses on a single question. dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">Respondents can be asked to ‘check all that apply’ or a cap can be applied (e.g. ‘select up to 3 choices’).

For example:

Aside from asking text-based questions like the above examples, a brand could also use a single or multi-select question to ask respondents to select the image they prefer more (like different iterations of a logo design, packaging options, branding colors, etc.).

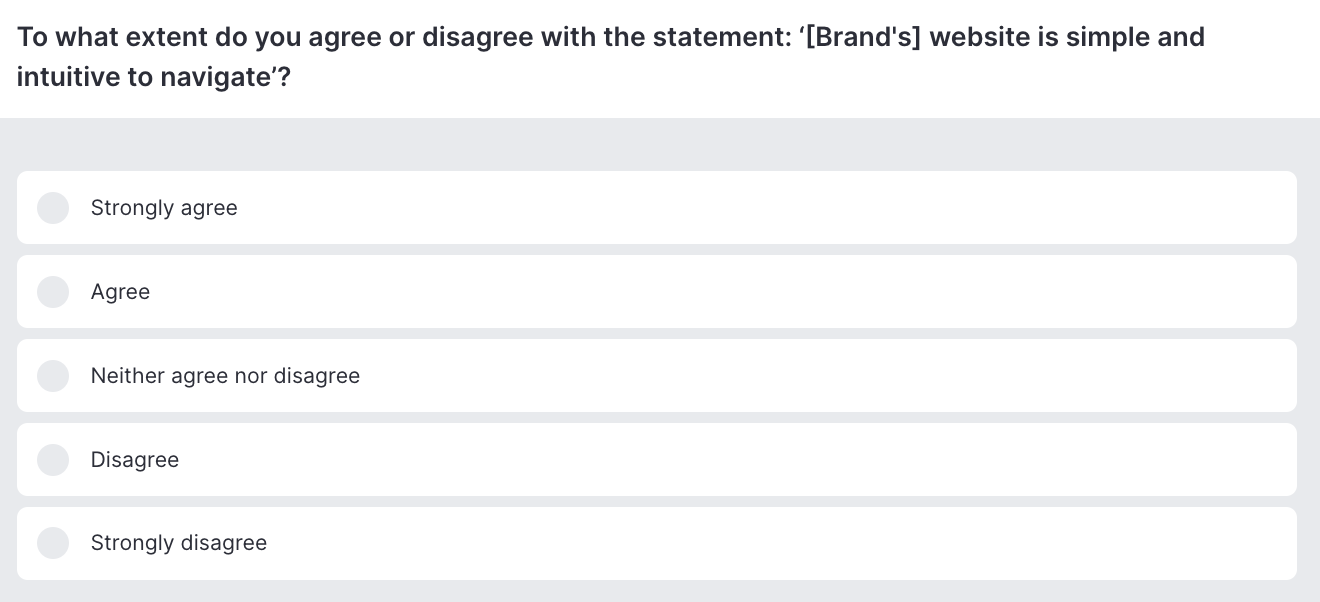

dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139749">Likert dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139766">scale dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-menu-id-param="menu_term_281139766" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139766"> questions

A dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139749">Likert scale is widely used as a convenient and easy-to-interpret rating method. dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">Respondents find it easy to indicate their degree of feelings by selecting the response they most identify with.

Slider scales

Slider scales are another good interactive way of formatting questions. They allow dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents to customize their level of feeling about a question, with a bit more variance and nuance allowed than a numeric scale:

One particularly common use of a slider scale in a dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139740">market dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139770">research dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-menu-id-param="menu_term_281139770" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139770"> study is known as a NPS (Net Promoter Score) - a way to measure dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139775">customer experience and loyalty . A 0-10 scale is used to ask customers how likely they are to recommend a brand’s product or services to others. The NPS score is calculated by subtracting the percentage of ‘detractors’ (those who respond with a 0-6) from the percentage of promoters (those who respond with a 9-10). dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">Respondents who select 7-8 are known as ‘passives’.

For example:

Drag and drop questions

Drag-and-drop question formats are a more ‘gamified’ approach to survey capture as they ask dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents to do more than simply check boxes or slide a scale. Drag-and-drop question formats are great for ranking exercises - asking dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents to place answer options in a certain order by dragging with their mouse. For example, you could ask survey takers to put pizza toppings in order of preference by dragging options from a list of possible answers to a box displaying their personal preferences:

Matrix questions

Matrix questions are a great way to consolidate a number of questions that ask for the same type of response (e.g. single select yes/no, true/false, or multi-select lists). They are mutually beneficial - making a survey look less daunting for the dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondent , and easier for a brand to set up than asking multiple separate questions.

Items in a matrix question are presented one by one, as respondents cycle through the pages selecting one answer for each coffee flavor shown.

-1.png?width=1500&height=800&name=Untitled%20design%20(5)-1.png)

While the above example shows a single-matrix question - meaning a respondent can only select one answer per element (in this case, coffee flavors), a matrix setup can also be used for multiple-choice questions - allowing respondents to choose multiple answers per element shown, or for rating questions - allowing respondents to assign a rating (e.g. 1-5) for a list of elements at once. Back to table of contents

How to write dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139745">quantitative survey questions

We’ve reviewed the types of questions you might ask in a quantitative survey, and how you might format those questions, but now for the actual crafting of the content.

When considering which questions to include in your survey, you’ll first want to establish what your research goals are and how these relate to your business goals. For example, thinking about the three types of dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139745">quantitative survey questions explained above - descriptive, comparative, and relationship-based - which type (or which combination) will best meet your research needs? The questions you ask dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents may be phrased in similar ways no matter what kind of layout you leverage, but you should have a good idea of how you’ll want to analyze the results as that will make it much easier to correctly set up your survey.

Quantitative questions tend to start with words like ‘how much,’ ‘how often,’ ‘to what degree,’ ‘what do you think of,’ ‘which of the following’ - anything that establishes what consumers do or think and that can be assigned a numerical code or value. Be sure to also include ‘other’ or ‘none of the above’ options in your quant questions, accommodating those who don’t feel the pre-set answers reflect their true opinion. As mentioned earlier, you can always include a small number of dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139748">open-ended questions in your quant survey to account for any ideas or expanded feedback that the pre-coded questions don’t (or can’t) cover. Back to table of contents

Examples of dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139745">quantitative survey questions

dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139745">Quantitative survey questions impose limits on the answers that dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents can choose from, and this is a good thing when it comes to measuring consumer opinions on a large scale and comparing across dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents . A large volume of freeform, open-ended answers is interesting when looking for themes from qualitative studies, but impractical to wade through when dealing with a large dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139756">sample size , and impossible to subject to dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139774">statistical analysis .

For example, a quantitative survey might aim to establish consumers' smartphone habits. This could include their frequency of buying a new smartphone, the considerations that drive purchase, which features they use their phone for, and how much they like their smartphone.

Some examples of quantitative survey questions relating to these habits would be:

Q. How often do you buy a new smartphone?

[single select question]

More than once per year

Every 1-2 years

Every 3-5 years

Every 6+ years

Q. Thinking about when you buy a smartphone, please rank the following factors in order of importance:

[drag and drop ranking question]

screen size

storage capacity

Q. How often do you use the following features on your smartphone?

[matrix question]

Q. How do you feel about your current smartphone?

[sliding scale]

I love it <-------> I hate it

Answers from these above questions, and others within the survey, would be analyzed to paint a picture of smartphone usage and attitude trends across a population and its sub-groups. dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139738">Qualitative research might then be carried out to explore those findings further - for example, people’s detailed attitudes towards their smartphones, how they feel about the amount of time they spend on it, and how features could be improved. Back to table of contents

quantilope’s Consumer Intelligence Platform specializes in automated, advanced survey insights so that researchers of any skill level can benefit from quick, high-quality consumer insights. With 12 advanced methods to choose from and a wide variety of quantitative question formats, quantilope is your one-stop-shop for all things dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139740">market research (including its dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139776">in-depth dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139738">qualitative research solution - inColor ).

When it comes to building your survey, you decide how you want to go about it. You can start with a blank slate and drop questions into your survey from a pre-programmed list, or you can get a head start with a survey dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139765">template for a particular business use case (like concept testing ) and customize from there. Once your survey is ready to launch, simply specify your dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139743">target audience , connect any panel (quantilope is panel agnostic), and watch as dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139737">respondents dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139783">answer questions in your survey in real-time by monitoring the fieldwork section of your project. AI-driven dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139764">data analysis takes the raw data and converts it into actionable findings so you never have to worry about manual calculations or statistical testing.

Whether you want to run your quantitative study entirely on your own or with the help of a classically trained research team member, the choice is yours on quantilope’s platform. For more information on how quantilope can help with your next dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139736">quantitative dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139768">research dropdown#toggle" data-dropdown-menu-id-param="menu_term_281139768" data-dropdown-placement-param="top" data-term-id="281139768"> project , get in touch below!

Get in touch to learn more about quantitative research with quantilope!

Related posts, survey results: how to analyze data and report on findings, how florida's natural leveraged better brand health tracking, quirk's virtual event: fab-brew-lous collaboration: product innovations from the melitta group, brand value: what it is, how to build it, and how to measure it.

Chapter 8 Survey Research: A Quantitative Technique

Why survey research.

In 2008, the voters of the United States elected our first African American president, Barack Obama. It may not surprise you to learn that when President Obama was coming of age in the 1970s, one-quarter of Americans reported that they would not vote for a qualified African American presidential nominee. Three decades later, when President Obama ran for the presidency, fewer than 8% of Americans still held that position, and President Obama won the election (Smith, 2009). Smith, T. W. (2009). Trends in willingness to vote for a black and woman for president, 1972–2008. GSS Social Change Report No. 55 . Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center. We know about these trends in voter opinion because the General Social Survey ( http://www.norc.uchicago.edu/GSS+Website ), a nationally representative survey of American adults, included questions about race and voting over the years described here. Without survey research, we may not know how Americans’ perspectives on race and the presidency shifted over these years.

8.1 Survey Research: What Is It and When Should It Be Used?

Learning objectives.

- Define survey research.

- Identify when it is appropriate to employ survey research as a data-collection strategy.

Most of you have probably taken a survey at one time or another, so you probably have a pretty good idea of what a survey is. Sometimes students in my research methods classes feel that understanding what a survey is and how to write one is so obvious, there’s no need to dedicate any class time to learning about it. This feeling is understandable—surveys are very much a part of our everyday lives—we’ve probably all taken one, we hear about their results in the news, and perhaps we’ve even administered one ourselves. What students quickly learn is that there is more to constructing a good survey than meets the eye. Survey design takes a great deal of thoughtful planning and often a great many rounds of revision. But it is worth the effort. As we’ll learn in this chapter, there are many benefits to choosing survey research as one’s method of data collection. We’ll take a look at what a survey is exactly, what some of the benefits and drawbacks of this method are, how to construct a survey, and what to do with survey data once one has it in hand.

Survey research A quantitative method for which a researcher poses the same set of questions, typically in a written format, to a sample of individuals. is a quantitative method whereby a researcher poses some set of predetermined questions to an entire group, or sample, of individuals. Survey research is an especially useful approach when a researcher aims to describe or explain features of a very large group or groups. This method may also be used as a way of quickly gaining some general details about one’s population of interest to help prepare for a more focused, in-depth study using time-intensive methods such as in-depth interviews or field research. In this case, a survey may help a researcher identify specific individuals or locations from which to collect additional data.

As is true of all methods of data collection, survey research is better suited to answering some kinds of research question more than others. In addition, as you’ll recall from Chapter 6 "Defining and Measuring Concepts" , operationalization works differently with different research methods. If your interest is in political activism, for example, you likely operationalize that concept differently in a survey than you would for a field research study of the same topic.

Key Takeaway

- Survey research is often used by researchers who wish to explain trends or features of large groups. It may also be used to assist those planning some more focused, in-depth study.

- Recall some of the possible research questions you came up with while reading previous chapters of this text. How might you frame those questions so that they could be answered using survey research?

8.2 Pros and Cons of Survey Research

- Identify and explain the strengths of survey research.

- Identify and explain the weaknesses of survey research.

Survey research, as with all methods of data collection, comes with both strengths and weaknesses. We’ll examine both in this section.

Strengths of Survey Method

Researchers employing survey methods to collect data enjoy a number of benefits. First, surveys are an excellent way to gather lots of information from many people. In my own study of older people’s experiences in the workplace, I was able to mail a written questionnaire to around 500 people who lived throughout the state of Maine at a cost of just over $1,000. This cost included printing copies of my seven-page survey, printing a cover letter, addressing and stuffing envelopes, mailing the survey, and buying return postage for the survey. I realize that $1,000 is nothing to sneeze at. But just imagine what it might have cost to visit each of those people individually to interview them in person. Consider the cost of gas to drive around the state, other travel costs, such as meals and lodging while on the road, and the cost of time to drive to and talk with each person individually. We could double, triple, or even quadruple our costs pretty quickly by opting for an in-person method of data collection over a mailed survey. Thus surveys are relatively cost effective .

Related to the benefit of cost effectiveness is a survey’s potential for generalizability . Because surveys allow researchers to collect data from very large samples for a relatively low cost, survey methods lend themselves to probability sampling techniques, which we discussed in Chapter 7 "Sampling" . Of all the data-collection methods described in this text, survey research is probably the best method to use when one hopes to gain a representative picture of the attitudes and characteristics of a large group.

Survey research also tends to be a reliable method of inquiry. This is because surveys are standardized The same questions, phrased in the same way, are posed to all participants, consistent. in that the same questions, phrased in exactly the same way, are posed to participants. Other methods, such as qualitative interviewing, which we’ll learn about in Chapter 9 "Interviews: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches" , do not offer the same consistency that a quantitative survey offers. This is not to say that all surveys are always reliable. A poorly phrased question can cause respondents to interpret its meaning differently, which can reduce that question’s reliability. Assuming well-constructed question and questionnaire design, one strength of survey methodology is its potential to produce reliable results.

The versatility A feature of survey research meaning that many different people use surveys for a variety of purposes and in a variety of settings. of survey research is also an asset. Surveys are used by all kinds of people in all kinds of professions. I repeat, surveys are used by all kinds of people in all kinds of professions. Is there a light bulb switching on in your head? I hope so. The versatility offered by survey research means that understanding how to construct and administer surveys is a useful skill to have for all kinds of jobs. Lawyers might use surveys in their efforts to select juries, social service and other organizations (e.g., churches, clubs, fundraising groups, activist groups) use them to evaluate the effectiveness of their efforts, businesses use them to learn how to market their products, governments use them to understand community opinions and needs, and politicians and media outlets use surveys to understand their constituencies.

In sum, the following are benefits of survey research:

- Cost-effective

- Generalizable

Weaknesses of Survey Method

As with all methods of data collection, survey research also comes with a few drawbacks. First, while one might argue that surveys are flexible in the sense that we can ask any number of questions on any number of topics in them, the fact that the survey researcher is generally stuck with a single instrument for collecting data (the questionnaire), surveys are in many ways rather inflexible . Let’s say you mail a survey out to 1,000 people and then discover, as responses start coming in, that your phrasing on a particular question seems to be confusing a number of respondents. At this stage, it’s too late for a do-over or to change the question for the respondents who haven’t yet returned their surveys. When conducting in-depth interviews, on the other hand, a researcher can provide respondents further explanation if they’re confused by a question and can tweak their questions as they learn more about how respondents seem to understand them.

Validity can also be a problem with surveys. Survey questions are standardized; thus it can be difficult to ask anything other than very general questions that a broad range of people will understand. Because of this, survey results may not be as valid as results obtained using methods of data collection that allow a researcher to more comprehensively examine whatever topic is being studied. Let’s say, for example, that you want to learn something about voters’ willingness to elect an African American president, as in our opening example in this chapter. General Social Survey respondents were asked, “If your party nominated an African American for president, would you vote for him if he were qualified for the job?” Respondents were then asked to respond either yes or no to the question. But what if someone’s opinion was more complex than could be answered with a simple yes or no? What if, for example, a person was willing to vote for an African American woman but not an African American man? I am not at all suggesting that such a perspective makes any sense, but it is conceivable that an individual might hold such a perspective.

In sum, potential drawbacks to survey research include the following:

- Inflexibility

Key Takeaways

- Strengths of survey research include its cost effectiveness, generalizability, reliability, and versatility.

- Weaknesses of survey research include inflexibility and issues with validity.

- What are some ways that survey researchers might overcome the weaknesses of this method?

- Find an article reporting results from survey research (remember how to use Sociological Abstracts?). How do the authors describe the strengths and weaknesses of their study? Are any of the strengths or weaknesses described here mentioned in the article?

8.3 Types of Surveys

- Define cross-sectional surveys, provide an example of a cross-sectional survey, and outline some of the drawbacks of cross-sectional research.

- Describe the various types of longitudinal surveys.

- Define retrospective surveys, and identify their strengths and weaknesses.

- Discuss some of the benefits and drawbacks of the various methods of delivering self-administered questionnaires.

There is much variety when it comes to surveys. This variety comes both in terms of time —when or with what frequency a survey is administered—and in terms of administration —how a survey is delivered to respondents. In this section we’ll take a look at what types of surveys exist when it comes to both time and administration.

In terms of time, there are two main types of surveys: cross-sectional and longitudinal. Cross-sectional surveys Surveys that are administered at one point in time. are those that are administered at just one point in time. These surveys offer researchers a sort of snapshot in time and give us an idea about how things are for our respondents at the particular point in time that the survey is administered. My own study of older workers mentioned previously is an example of a cross-sectional survey. I administered the survey at just one time.

Another example of a cross-sectional survey comes from Aniko Kezdy and colleagues’ study (Kezdy, Martos, Boland, & Horvath-Szabo, 2011) Kezdy, A., Martos, T., Boland, V., & Horvath-Szabo, K. (2011). Religious doubts and mental health in adolescence and young adulthood: The association with religious attitudes. Journal of Adolescence, 34 , 39–47. of the association between religious attitudes, religious beliefs, and mental health among students in Hungary. These researchers administered a single, one-time-only, cross-sectional survey to a convenience sample of 403 high school and college students. The survey focused on how religious attitudes impact various aspects of one’s life and health. The researchers found from analysis of their cross-sectional data that anxiety and depression were highest among those who had both strong religious beliefs and also some doubts about religion. Yet another recent example of cross-sectional survey research can be seen in Bateman and colleagues’ study (Bateman, Pike, & Butler, 2011) of how the perceived publicness of social networking sites influences users’ self-disclosures. Bateman, P. J., Pike, J. C., & Butler, B. S. (2011). To disclose or not: Publicness in social networking sites. Information Technology & People, 24 , 78–100. These researchers administered an online survey to undergraduate and graduate business students. They found that even though revealing information about oneself is viewed as key to realizing many of the benefits of social networking sites, respondents were less willing to disclose information about themselves as their perceptions of a social networking site’s publicness rose. That is, there was a negative relationship between perceived publicness of a social networking site and plans to self-disclose on the site.

One problem with cross-sectional surveys is that the events, opinions, behaviors, and other phenomena that such surveys are designed to assess don’t generally remain stagnant. Thus generalizing from a cross-sectional survey about the way things are can be tricky; perhaps you can say something about the way things were in the moment that you administered your survey, but it is difficult to know whether things remained that way for long after you administered your survey. Think, for example, about how Americans might have responded if administered a survey asking for their opinions on terrorism on September 10, 2001. Now imagine how responses to the same set of questions might differ were they administered on September 12, 2001. The point is not that cross-sectional surveys are useless; they have many important uses. But researchers must remember what they have captured by administering a cross-sectional survey; that is, as previously noted, a snapshot of life as it was at the time that the survey was administered.

One way to overcome this sometimes problematic aspect of cross-sectional surveys is to administer a longitudinal survey. Longitudinal surveys Surveys that enable a researcher to make observations over some extended period of time. are those that enable a researcher to make observations over some extended period of time. There are several types of longitudinal surveys, including trend, panel, and cohort surveys. We’ll discuss all three types here, along with another type of survey called retrospective. Retrospective surveys fall somewhere in between cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys.

The first type of longitudinal survey is called a trend survey A type of longitudinal survey where a researcher examines changes in trends over time; the same people do not necessarily participate in the survey more than once. . The main focus of a trend survey is, perhaps not surprisingly, trends. Researchers conducting trend surveys are interested in how people’s inclinations change over time. The Gallup opinion polls are an excellent example of trend surveys. You can read more about Gallup on their website: http://www.gallup.com/Home.aspx . To learn about how public opinion changes over time, Gallup administers the same questions to people at different points in time. For example, for several years Gallup has polled Americans to find out what they think about gas prices (something many of us happen to have opinions about). One thing we’ve learned from Gallup’s polling is that price increases in gasoline caused financial hardship for 67% of respondents in 2011, up from 40% in the year 2000. Gallup’s findings about trends in opinions about gas prices have also taught us that whereas just 34% of people in early 2000 thought the current rise in gas prices was permanent, 54% of people in 2011 believed the rise to be permanent. Thus through Gallup’s use of trend survey methodology, we’ve learned that Americans seem to feel generally less optimistic about the price of gas these days than they did 10 or so years ago. You can read about these and other findings on Gallup’s gasoline questions at http://www.gallup.com/poll/147632/Gas-Prices.aspx#1 . It should be noted that in a trend survey, the same people are probably not answering the researcher’s questions each year. Because the interest here is in trends, not specific people, as long as the researcher’s sample is representative of whatever population he or she wishes to describe trends for, it isn’t important that the same people participate each time.

Next are panel surveys A type of longitudinal survey in which a researcher surveys the exact same sample several times over a period of time. . Unlike in a trend survey, in a panel survey the same people do participate in the survey each time it is administered. As you might imagine, panel studies can be difficult and costly. Imagine trying to administer a survey to the same 100 people every year for, say, 5 years in a row. Keeping track of where people live, when they move, and when they die takes resources that researchers often don’t have. When they do, however, the results can be quite powerful. The Youth Development Study (YDS), administered from the University of Minnesota, offers an excellent example of a panel study. You can read more about the Youth Development Study at its website: http://www.soc.umn.edu/research/yds . Since 1988, YDS researchers have administered an annual survey to the same 1,000 people. Study participants were in ninth grade when the study began, and they are now in their thirties. Several hundred papers, articles, and books have been written using data from the YDS. One of the major lessons learned from this panel study is that work has a largely positive impact on young people (Mortimer, 2003). Mortimer, J. T. (2003). Working and growing up in America . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Contrary to popular beliefs about the impact of work on adolescents’ performance in school and transition to adulthood, work in fact increases confidence, enhances academic success, and prepares students for success in their future careers. Without this panel study, we may not be aware of the positive impact that working can have on young people.

Another type of longitudinal survey is a cohort survey A type of longitudinal survey where a researcher’s interest is in a particular group of people who share some common experience or characteristic. . In a cohort survey, a researcher identifies some category of people that are of interest and then regularly surveys people who fall into that category. The same people don’t necessarily participate from year to year, but all participants must meet whatever categorical criteria fulfill the researcher’s primary interest. Common cohorts that may be of interest to researchers include people of particular generations or those who were born around the same time period, graduating classes, people who began work in a given industry at the same time, or perhaps people who have some specific life experience in common. An example of this sort of research can be seen in Christine Percheski’s work (2008) Percheski, C. (2008). Opting out? Cohort differences in professional women’s employment rates from 1960 to 2005. American Sociological Review, 73 , 497–517. on cohort differences in women’s employment. Percheski compared women’s employment rates across seven different generational cohorts, from Progressives born between 1906 and 1915 to Generation Xers born between 1966 and 1975. She found, among other patterns, that professional women’s labor force participation had increased across all cohorts. She also found that professional women with young children from Generation X had higher labor force participation rates than similar women from previous generations, concluding that mothers do not appear to be opting out of the workforce as some journalists have speculated (Belkin, 2003). Belkin, L. (2003, October 26). The opt-out revolution. New York Times , pp. 42–47, 58, 85–86.

All three types of longitudinal surveys share the strength that they permit a researcher to make observations over time. This means that if whatever behavior or other phenomenon the researcher is interested in changes, either because of some world event or because people age, the researcher will be able to capture those changes. Table 8.1 "Types of Longitudinal Surveys" summarizes each of the three types of longitudinal surveys.

Table 8.1 Types of Longitudinal Surveys

Finally, retrospective surveys A type of survey in which participants are asked to report events from the past. are similar to other longitudinal studies in that they deal with changes over time, but like a cross-sectional study, they are administered only once. In a retrospective survey, participants are asked to report events from the past. By having respondents report past behaviors, beliefs, or experiences, researchers are able to gather longitudinal-like data without actually incurring the time or expense of a longitudinal survey. Of course, this benefit must be weighed against the possibility that people’s recollections of their pasts may be faulty. Imagine, for example, that you’re asked in a survey to respond to questions about where, how, and with whom you spent last Valentine’s Day. As last Valentine’s Day can’t have been more than 12 months ago, chances are good that you might be able to respond accurately to any survey questions about it. But now let’s say the research wants to know how last Valentine’s Day compares to previous Valentine’s Days, so he asks you to report on where, how, and with whom you spent the preceding six Valentine’s Days. How likely is it that you will remember? Will your responses be as accurate as they might have been had you been asked the question each year over the past 6 years rather than asked to report on all years today?

In sum, when or with what frequency a survey is administered will determine whether your survey is cross-sectional or longitudinal. While longitudinal surveys are certainly preferable in terms of their ability to track changes over time, the time and cost required to administer a longitudinal survey can be prohibitive. As you may have guessed, the issues of time described here are not necessarily unique to survey research. Other methods of data collection can be cross-sectional or longitudinal—these are really matters of research design. But we’ve placed our discussion of these terms here because they are most commonly used by survey researchers to describe the type of survey administered. Another aspect of survey administration deals with how surveys are administered. We’ll examine that next.

Administration

Surveys vary not just in terms of when they are administered but also in terms of how they are administered. One common way to administer surveys is in the form of self-administered questionnaires A set of written questions that a research participant responds to by filling in answers on her or his own without the assistance of a researcher. . This means that a research participant is given a set of questions, in writing, to which he or she is asked to respond. Self-administered questionnaires can be delivered in hard copy format, typically via mail, or increasingly more commonly, online. We’ll consider both modes of delivery here.

Hard copy self-administered questionnaires may be delivered to participants in person or via snail mail. Perhaps you’ve take a survey that was given to you in person; on many college campuses it is not uncommon for researchers to administer surveys in large social science classes (as you might recall from the discussion in our chapter on sampling). In my own introduction to sociology courses, I’ve welcomed graduate students and professors doing research in areas that are relevant to my students, such as studies of campus life, to administer their surveys to the class. If you are ever asked to complete a survey in a similar setting, it might be interesting to note how your perspective on the survey and its questions could be shaped by the new knowledge you’re gaining about survey research in this chapter.

Researchers may also deliver surveys in person by going door-to-door and either asking people to fill them out right away or making arrangements for the researcher to return to pick up completed surveys. Though the advent of online survey tools has made door-to-door delivery of surveys less common, I still see an occasional survey researcher at my door, especially around election time. This mode of gathering data is apparently still used by political campaign workers, at least in some areas of the country.

If you are not able to visit each member of your sample personally to deliver a survey, you might consider sending your survey through the mail. While this mode of delivery may not be ideal (imagine how much less likely you’d probably be to return a survey that didn’t come with the researcher standing on your doorstep waiting to take it from you), sometimes it is the only available or the most practical option. As I’ve said, this may not be the most ideal way of administering a survey because it can be difficult to convince people to take the time to complete and return your survey.

Often survey researchers who deliver their surveys via snail mail may provide some advance notice to respondents about the survey to get people thinking about and preparing to complete it. They may also follow up with their sample a few weeks after their survey has been sent out. This can be done not only to remind those who have not yet completed the survey to please do so but also to thank those who have already returned the survey. Most survey researchers agree that this sort of follow-up is essential for improving mailed surveys’ return rates (Babbie, 2010). Babbie, E. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

In my own study of older workers’ harassment experiences, people in the sample were notified in advance of the survey mailing via an article describing the research in a newsletter they received from the agency with whom I had partnered to conduct the survey. When I mailed the survey, a $1 bill was included with each in order to provide some incentive and an advance token of thanks to participants for returning the surveys. Two months after the initial mailing went out, those who were sent a survey were contacted by phone. While returned surveys did not contain any identifying information about respondents, my research assistants contacted individuals to whom a survey had been mailed to remind them that it was not too late to return their survey and to say thank to those who may have already done so. Four months after the initial mailing went out, everyone on the original mailing list received a letter thanking those who had returned the survey and once again reminding those who had not that it was not too late to do so. The letter included a return postcard for respondents to complete should they wish to receive another copy of the survey. Respondents were also provided a telephone number to call and were provided the option of completing the survey by phone. As you can see, administering a survey by mail typically involves much more than simply arranging a single mailing; participants may be notified in advance of the mailing, they then receive the mailing, and then several follow-up contacts will likely be made after the survey has been mailed.

Earlier I mentioned online delivery as another way to administer a survey. This delivery mechanism is becoming increasingly common, no doubt because it is easy to use, relatively cheap, and may be quicker than knocking on doors or waiting for mailed surveys to be returned. To deliver a survey online, a researcher may subscribe to a service that offers online delivery or use some delivery mechanism that is available for free. SurveyMonkey offers both free and paid online survey services ( http://www.surveymonkey.com ). One advantage to using a service like SurveyMonkey, aside from the advantages of online delivery already mentioned, is that results can be provided to you in formats that are readable by data analysis programs such as SPSS, Systat, and Excel. This saves you, the researcher, the step of having to manually enter data into your analysis program, as you would if you administered your survey in hard copy format.