ANA Nursing Resources Hub

Search Resources Hub

Critical Thinking in Nursing: Tips to Develop the Skill

4 min read • February, 09 2024

Critical thinking in nursing helps caregivers make decisions that lead to optimal patient care. In school, educators and clinical instructors introduced you to critical-thinking examples in nursing. These educators encouraged using learning tools for assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Nurturing these invaluable skills continues once you begin practicing. Critical thinking is essential to providing quality patient care and should continue to grow throughout your nursing career until it becomes second nature.

What Is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing involves identifying a problem, determining the best solution, and implementing an effective method to resolve the issue using clinical decision-making skills.

Reflection comes next. Carefully consider whether your actions led to the right solution or if there may have been a better course of action.

Remember, there's no one-size-fits-all treatment method — you must determine what's best for each patient.

How Is Critical Thinking Important for Nurses?

As a patient's primary contact, a nurse is typically the first to notice changes in their status. One example of critical thinking in nursing is interpreting these changes with an open mind. Make impartial decisions based on evidence rather than opinions. By applying critical-thinking skills to anticipate and understand your patients' needs, you can positively impact their quality of care and outcomes.

Elements of Critical Thinking in Nursing

To assess situations and make informed decisions, nurses must integrate these specific elements into their practice:

- Clinical judgment. Prioritize a patient's care needs and make adjustments as changes occur. Gather the necessary information and determine what nursing intervention is needed. Keep in mind that there may be multiple options. Use your critical-thinking skills to interpret and understand the importance of test results and the patient’s clinical presentation, including their vital signs. Then prioritize interventions and anticipate potential complications.

- Patient safety. Recognize deviations from the norm and take action to prevent harm to the patient. Suppose you don't think a change in a patient's medication is appropriate for their treatment. Before giving the medication, question the physician's rationale for the modification to avoid a potential error.

- Communication and collaboration. Ask relevant questions and actively listen to others while avoiding judgment. Promoting a collaborative environment may lead to improved patient outcomes and interdisciplinary communication.

- Problem-solving skills. Practicing your problem-solving skills can improve your critical-thinking skills. Analyze the problem, consider alternate solutions, and implement the most appropriate one. Besides assessing patient conditions, you can apply these skills to other challenges, such as staffing issues .

How to Develop and Apply Critical-Thinking Skills in Nursing

Critical-thinking skills develop as you gain experience and advance in your career. The ability to predict and respond to nursing challenges increases as you expand your knowledge and encounter real-life patient care scenarios outside of what you learned from a textbook.

Here are five ways to nurture your critical-thinking skills:

- Be a lifelong learner. Continuous learning through educational courses and professional development lets you stay current with evidence-based practice . That knowledge helps you make informed decisions in stressful moments.

- Practice reflection. Allow time each day to reflect on successes and areas for improvement. This self-awareness can help identify your strengths, weaknesses, and personal biases to guide your decision-making.

- Open your mind. Don't assume you're right. Ask for opinions and consider the viewpoints of other nurses, mentors , and interdisciplinary team members.

- Use critical-thinking tools. Structure your thinking by incorporating nursing process steps or a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) to organize information, evaluate options, and identify underlying issues.

- Be curious. Challenge assumptions by asking questions to ensure current care methods are valid, relevant, and supported by evidence-based practice .

Critical thinking in nursing is invaluable for safe, effective, patient-centered care. You can successfully navigate challenges in the ever-changing health care environment by continually developing and applying these skills.

Images sourced from Getty Images

Related Resources

Item(s) added to cart

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (Explained W/ Examples)

Last updated on August 23rd, 2023

Critical thinking is a foundational skill applicable across various domains, including education, problem-solving, decision-making, and professional fields such as science, business, healthcare, and more.

It plays a crucial role in promoting logical and rational thinking, fostering informed decision-making, and enabling individuals to navigate complex and rapidly changing environments.

In this article, we will look at what is critical thinking in nursing practice, its importance, and how it enables nurses to excel in their roles while also positively impacting patient outcomes.

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is a cognitive process that involves analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

It’s a mental activity that goes beyond simple memorization or acceptance of information at face value.

Critical thinking involves careful, reflective, and logical thinking to understand complex problems, consider various perspectives, and arrive at well-reasoned conclusions or solutions.

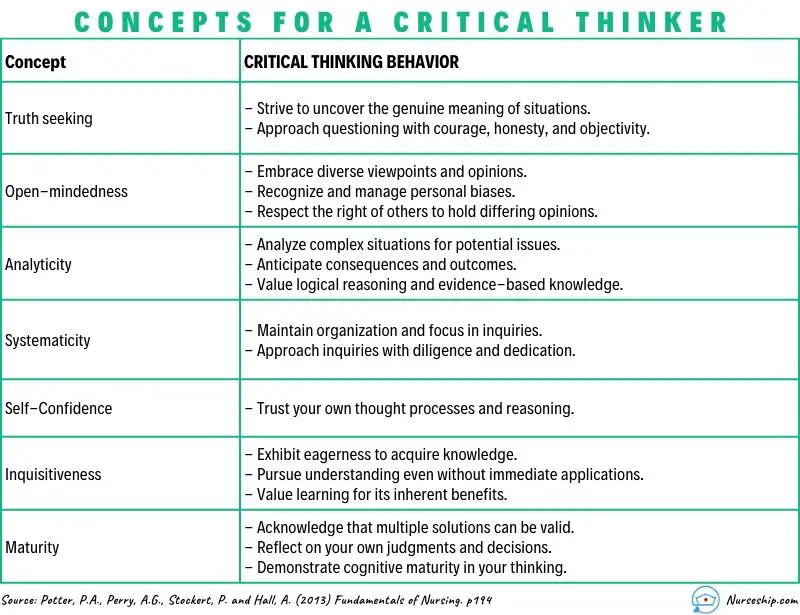

Key aspects of critical thinking include:

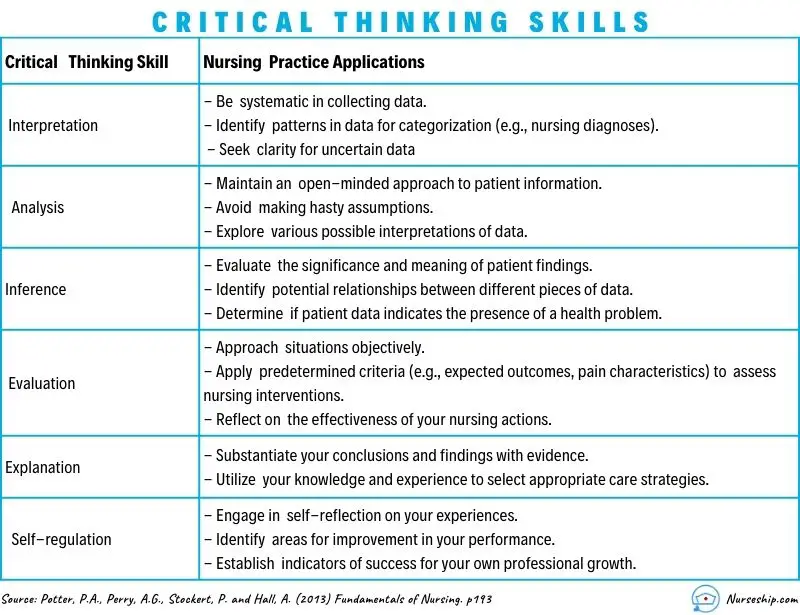

- Analysis: Critical thinking begins with the thorough examination of information, ideas, or situations. It involves breaking down complex concepts into smaller parts to better understand their components and relationships.

- Evaluation: Critical thinkers assess the quality and reliability of information or arguments. They weigh evidence, identify strengths and weaknesses, and determine the credibility of sources.

- Synthesis: Critical thinking involves combining different pieces of information or ideas to create a new understanding or perspective. This involves connecting the dots between various sources and integrating them into a coherent whole.

- Inference: Critical thinkers draw logical and well-supported conclusions based on the information and evidence available. They use reasoning to make educated guesses about situations where complete information might be lacking.

- Problem-Solving: Critical thinking is essential in solving complex problems. It allows individuals to identify and define problems, generate potential solutions, evaluate the pros and cons of each solution, and choose the most appropriate course of action.

- Creativity: Critical thinking involves thinking outside the box and considering alternative viewpoints or approaches. It encourages the exploration of new ideas and solutions beyond conventional thinking.

- Reflection: Critical thinkers engage in self-assessment and reflection on their thought processes. They consider their own biases, assumptions, and potential errors in reasoning, aiming to improve their thinking skills over time.

- Open-Mindedness: Critical thinkers approach ideas and information with an open mind, willing to consider different viewpoints and perspectives even if they challenge their own beliefs.

- Effective Communication: Critical thinkers can articulate their thoughts and reasoning clearly and persuasively to others. They can express complex ideas in a coherent and understandable manner.

- Continuous Learning: Critical thinking encourages a commitment to ongoing learning and intellectual growth. It involves seeking out new knowledge, refining thinking skills, and staying receptive to new information.

Definition of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an intellectual process of analyzing, evaluating, and synthesizing information to make reasoned and informed decisions.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

Critical thinking in nursing is a vital cognitive skill that involves analyzing, evaluating, and making reasoned decisions about patient care.

It’s an essential aspect of a nurse’s professional practice as it enables them to provide safe and effective care to patients.

Critical thinking involves a careful and deliberate thought process to gather and assess information, consider alternative solutions, and make informed decisions based on evidence and sound judgment.

This skill helps nurses to:

- Assess Information: Critical thinking allows nurses to thoroughly assess patient information, including medical history, symptoms, and test results. By analyzing this data, nurses can identify patterns, discrepancies, and potential issues that may require further investigation.

- Diagnose: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data and collaboratively work with other healthcare professionals to formulate accurate nursing diagnoses. This is crucial for developing appropriate care plans that address the unique needs of each patient.

- Plan and Implement Care: Once a nursing diagnosis is established, critical thinking helps nurses develop effective care plans. They consider various interventions and treatment options, considering the patient’s preferences, medical history, and evidence-based practices.

- Evaluate Outcomes: After implementing interventions, critical thinking enables nurses to evaluate the outcomes of their actions. If the desired outcomes are not achieved, nurses can adapt their approach and make necessary changes to the care plan.

- Prioritize Care: In busy healthcare environments, nurses often face situations where they must prioritize patient care. Critical thinking helps them determine which patients require immediate attention and which interventions are most essential.

- Communicate Effectively: Critical thinking skills allow nurses to communicate clearly and confidently with patients, their families, and other members of the healthcare team. They can explain complex medical information and treatment plans in a way that is easily understood by all parties involved.

- Identify Problems: Nurses use critical thinking to identify potential complications or problems in a patient’s condition. This early recognition can lead to timely interventions and prevent further deterioration.

- Collaborate: Healthcare is a collaborative effort involving various professionals. Critical thinking enables nurses to actively participate in interdisciplinary discussions, share their insights, and contribute to holistic patient care.

- Ethical Decision-Making: Critical thinking helps nurses navigate ethical dilemmas that can arise in patient care. They can analyze different perspectives, consider ethical principles, and make morally sound decisions.

- Continual Learning: Critical thinking encourages nurses to seek out new knowledge, stay up-to-date with the latest research and medical advancements, and incorporate evidence-based practices into their care.

In summary, critical thinking is an integral skill for nurses, allowing them to provide high-quality, patient-centered care by analyzing information, making informed decisions, and adapting their approaches as needed.

It’s a dynamic process that enhances clinical reasoning , problem-solving, and overall patient outcomes.

What are the Levels of Critical Thinking in Nursing?

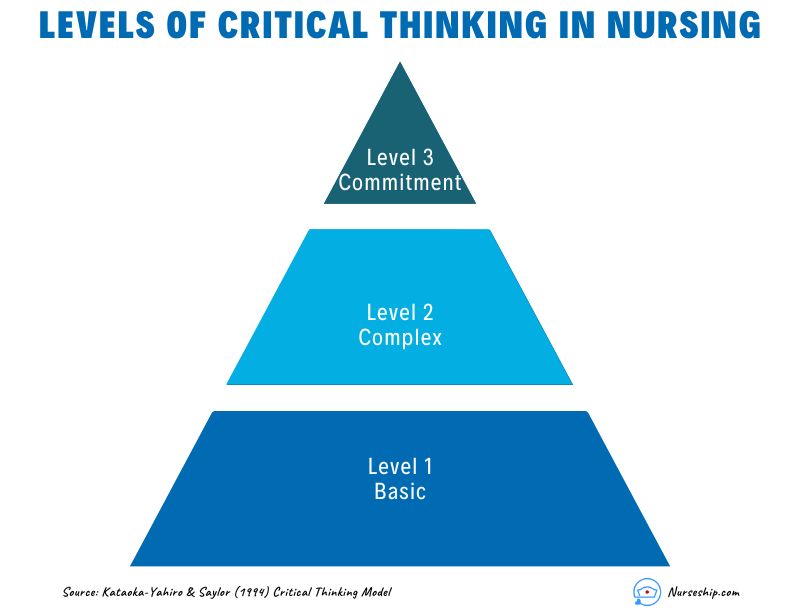

The development of critical thinking in nursing practice involves progressing through three levels: basic, complex, and commitment.

The Kataoka-Yahiro and Saylor model outlines this progression.

1. Basic Critical Thinking:

At this level, learners trust experts for solutions. Thinking is based on rules and principles. For instance, nursing students may strictly follow a procedure manual without personalization, as they lack experience. Answers are seen as right or wrong, and the opinions of experts are accepted.

2. Complex Critical Thinking:

Learners start to analyze choices independently and think creatively. They recognize conflicting solutions and weigh benefits and risks. Thinking becomes innovative, with a willingness to consider various approaches in complex situations.

3. Commitment:

At this level, individuals anticipate decision points without external help and take responsibility for their choices. They choose actions or beliefs based on available alternatives, considering consequences and accountability.

As nurses gain knowledge and experience, their critical thinking evolves from relying on experts to independent analysis and decision-making, ultimately leading to committed and accountable choices in patient care.

Why Critical Thinking is Important in Nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing for several crucial reasons:

Patient Safety:

Nursing decisions directly impact patient well-being. Critical thinking helps nurses identify potential risks, make informed choices, and prevent errors.

Clinical Judgment:

Nursing decisions often involve evaluating information from various sources, such as patient history, lab results, and medical literature.

Critical thinking assists nurses in critically appraising this information, distinguishing credible sources, and making rational judgments that align with evidence-based practices.

Enhances Decision-Making:

In nursing, critical thinking allows nurses to gather relevant patient information, assess it objectively, and weigh different options based on evidence and analysis.

This process empowers them to make informed decisions about patient care, treatment plans, and interventions, ultimately leading to better outcomes.

Promotes Problem-Solving:

Nurses encounter complex patient issues that require effective problem-solving.

Critical thinking equips them to break down problems into manageable parts, analyze root causes, and explore creative solutions that consider the unique needs of each patient.

Drives Creativity:

Nursing care is not always straightforward. Critical thinking encourages nurses to think creatively and explore innovative approaches to challenges, especially when standard protocols might not suffice for unique patient situations.

Fosters Effective Communication:

Communication is central to nursing. Critical thinking enables nurses to clearly express their thoughts, provide logical explanations for their decisions, and engage in meaningful dialogues with patients, families, and other healthcare professionals.

Aids Learning:

Nursing is a field of continuous learning. Critical thinking encourages nurses to engage in ongoing self-directed education, seeking out new knowledge, embracing new techniques, and staying current with the latest research and developments.

Improves Relationships:

Open-mindedness and empathy are essential in nursing relationships.

Critical thinking encourages nurses to consider diverse viewpoints, understand patients’ perspectives, and communicate compassionately, leading to stronger therapeutic relationships.

Empowers Independence:

Nursing often requires autonomous decision-making. Critical thinking empowers nurses to analyze situations independently, make judgments without undue influence, and take responsibility for their actions.

Facilitates Adaptability:

Healthcare environments are ever-changing. Critical thinking equips nurses with the ability to quickly assess new information, adjust care plans, and navigate unexpected situations while maintaining patient safety and well-being.

Strengthens Critical Analysis:

In the era of vast information, nurses must discern reliable data from misinformation.

Critical thinking helps them scrutinize sources, question assumptions, and make well-founded choices based on credible information.

How to Apply Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples)

Here are some examples of how nurses can apply critical thinking.

Assess Patient Data:

Critical Thinking Action: Carefully review patient history, symptoms, and test results.

Example: A nurse notices a change in a diabetic patient’s blood sugar levels. Instead of just administering insulin, the nurse considers recent dietary changes, activity levels, and possible medication interactions before adjusting the treatment plan.

Diagnose Patient Needs:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze patient data to identify potential nursing diagnoses.

Example: After reviewing a patient’s lab results, vital signs, and observations, a nurse identifies “ Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity ” due to the patient’s limited mobility.

Plan and Implement Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Develop a care plan based on patient needs and evidence-based practices.

Example: For a patient at risk of falls, the nurse plans interventions such as hourly rounding, non-slip footwear, and bed alarms to ensure patient safety.

Evaluate Interventions:

Critical Thinking Action: Assess the effectiveness of interventions and modify the care plan as needed.

Example: After administering pain medication, the nurse evaluates its impact on the patient’s comfort level and considers adjusting the dosage or trying an alternative pain management approach.

Prioritize Care:

Critical Thinking Action: Determine the order of interventions based on patient acuity and needs.

Example: In a busy emergency department, the nurse triages patients by considering the severity of their conditions, ensuring that critical cases receive immediate attention.

Collaborate with the Healthcare Team:

Critical Thinking Action: Participate in interdisciplinary discussions and share insights.

Example: During rounds, a nurse provides input on a patient’s response to treatment, which prompts the team to adjust the care plan for better outcomes.

Ethical Decision-Making:

Critical Thinking Action: Analyze ethical dilemmas and make morally sound choices.

Example: When a terminally ill patient expresses a desire to stop treatment, the nurse engages in ethical discussions, respecting the patient’s autonomy and ensuring proper end-of-life care.

Patient Education:

Critical Thinking Action: Tailor patient education to individual needs and comprehension levels.

Example: A nurse uses visual aids and simplified language to explain medication administration to a patient with limited literacy skills.

Adapt to Changes:

Critical Thinking Action: Quickly adjust care plans when patient conditions change.

Example: During post-operative recovery, a nurse notices signs of infection and promptly informs the healthcare team to initiate appropriate treatment adjustments.

Critical Analysis of Information:

Critical Thinking Action: Evaluate information sources for reliability and relevance.

Example: When presented with conflicting research studies, a nurse critically examines the methodologies and sample sizes to determine which study is more credible.

Making Sense of Critical Thinking Skills

What is the purpose of critical thinking in nursing.

The purpose of critical thinking in nursing is to enable nurses to effectively analyze, interpret, and evaluate patient information, make informed clinical judgments, develop appropriate care plans, prioritize interventions, and adapt their approaches as needed, thereby ensuring safe, evidence-based, and patient-centered care.

Why critical thinking is important in nursing?

Critical thinking is important in nursing because it promotes safe decision-making, accurate clinical judgment, problem-solving, evidence-based practice, holistic patient care, ethical reasoning, collaboration, and adapting to dynamic healthcare environments.

Critical thinking skill also enhances patient safety, improves outcomes, and supports nurses’ professional growth.

How is critical thinking used in the nursing process?

Critical thinking is integral to the nursing process as it guides nurses through the systematic approach of assessing, diagnosing, planning, implementing, and evaluating patient care. It involves:

- Assessment: Critical thinking enables nurses to gather and interpret patient data accurately, recognizing relevant patterns and cues.

- Diagnosis: Nurses use critical thinking to analyze patient data, identify nursing diagnoses, and differentiate actual issues from potential complications.

- Planning: Critical thinking helps nurses develop tailored care plans, selecting appropriate interventions based on patient needs and evidence.

- Implementation: Nurses make informed decisions during interventions, considering patient responses and adjusting plans as needed.

- Evaluation: Critical thinking supports the assessment of patient outcomes, determining the effectiveness of intervention, and adapting care accordingly.

Throughout the nursing process , critical thinking ensures comprehensive, patient-centered care and fosters continuous improvement in clinical judgment and decision-making.

What is an example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice?

An example of the critical thinking attitude of independent thinking in nursing practice could be:

A nurse is caring for a patient with a complex medical history who is experiencing a new set of symptoms. The nurse carefully reviews the patient’s history, recent test results, and medication list.

While discussing the case with the healthcare team, the nurse realizes that the current treatment plan might not be addressing all aspects of the patient’s condition.

Instead of simply following the established protocol, the nurse independently considers alternative approaches based on their assessment.

The nurse proposes a modification to the treatment plan, citing the rationale and evidence supporting the change.

This demonstrates independent thinking by critically evaluating the situation, challenging assumptions, and advocating for a more personalized and effective patient care approach.

How to use Costa’s level of questioning for critical thinking in nursing?

Costa’s levels of questioning can be applied in nursing to facilitate critical thinking and stimulate a deeper understanding of patient situations. The levels of questioning are as follows:

| Level 1: Gathering | 1. What are the common side effects of the prescribed medication? 2. When was the patient’s last bowel movement? 3. Who is the patient’s emergency contact person? 4. Describe the patient’s current level of pain. 5. What information is in the patient’s medical record? |

| 1. What would happen if the patient’s blood pressure falls further? 2. Compare the patient’s oxygen saturation levels before and after administering oxygen. 3. What other nursing interventions could be considered for wound care? 4. Infer the potential reasons behind the patient’s increased heart rate. 5. Analyze the relationship between the patient’s diet and blood glucose levels. | |

| 1. What do you think will be the patient’s response to the new pain management strategy? 2. Could the patient’s current symptoms be indicative of an underlying complication? 3. How would you prioritize care for patients with varying acuity levels in the emergency department? 4. What evidence supports your choice of administering the medication at this time? 5. Create a care plan for a patient with complex needs requiring multiple interventions. |

- 15 Attitudes of Critical Thinking in Nursing (Explained W/ Examples)

- Nursing Concept Map (FREE Template)

- Clinical Reasoning In Nursing (Explained W/ Example)

- 8 Stages Of The Clinical Reasoning Cycle

- How To Improve Critical Thinking Skills In Nursing? 24 Strategies With Examples

- What is the “5 Whys” Technique?

- What Are Socratic Questions?

Critical thinking in nursing is the foundation that underpins safe, effective, and patient-centered care.

Critical thinking skills empower nurses to navigate the complexities of their profession while consistently providing high-quality care to diverse patient populations.

Reading Recommendation

Potter, P.A., Perry, A.G., Stockert, P. and Hall, A. (2013) Fundamentals of Nursing

Comments are closed.

Medical & Legal Disclaimer

All the contents on this site are for entertainment, informational, educational, and example purposes ONLY. These contents are not intended to be used as a substitute for professional medical advice or practice guidelines. However, we aim to publish precise and current information. By using any content on this website, you agree never to hold us legally liable for damages, harm, loss, or misinformation. Read the privacy policy and terms and conditions.

Privacy Policy

Terms & Conditions

© 2024 nurseship.com. All rights reserved.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing? (With Examples, Importance, & How to Improve)

Successful nursing requires learning several skills used to communicate with patients, families, and healthcare teams. One of the most essential skills nurses must develop is the ability to demonstrate critical thinking. If you are a nurse, perhaps you have asked if there is a way to know how to improve critical thinking in nursing? As you read this article, you will learn what critical thinking in nursing is and why it is important. You will also find 18 simple tips to improve critical thinking in nursing and sample scenarios about how to apply critical thinking in your nursing career.

What is Critical Thinking in Nursing?

4 reasons why critical thinking is so important in nursing, 1. critical thinking skills will help you anticipate and understand changes in your patient’s condition., 2. with strong critical thinking skills, you can make decisions about patient care that is most favorable for the patient and intended outcomes., 3. strong critical thinking skills in nursing can contribute to innovative improvements and professional development., 4. critical thinking skills in nursing contribute to rational decision-making, which improves patient outcomes., what are the 8 important attributes of excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. the ability to interpret information:, 2. independent thought:, 3. impartiality:, 4. intuition:, 5. problem solving:, 6. flexibility:, 7. perseverance:, 8. integrity:, examples of poor critical thinking vs excellent critical thinking in nursing, 1. scenario: patient/caregiver interactions, poor critical thinking:, excellent critical thinking:, 2. scenario: improving patient care quality, 3. scenario: interdisciplinary collaboration, 4. scenario: precepting nursing students and other nurses, how to improve critical thinking in nursing, 1. demonstrate open-mindedness., 2. practice self-awareness., 3. avoid judgment., 4. eliminate personal biases., 5. do not be afraid to ask questions., 6. find an experienced mentor., 7. join professional nursing organizations., 8. establish a routine of self-reflection., 9. utilize the chain of command., 10. determine the significance of data and decide if it is sufficient for decision-making., 11. volunteer for leadership positions or opportunities., 12. use previous facts and experiences to help develop stronger critical thinking skills in nursing., 13. establish priorities., 14. trust your knowledge and be confident in your abilities., 15. be curious about everything., 16. practice fair-mindedness., 17. learn the value of intellectual humility., 18. never stop learning., 4 consequences of poor critical thinking in nursing, 1. the most significant risk associated with poor critical thinking in nursing is inadequate patient care., 2. failure to recognize changes in patient status:, 3. lack of effective critical thinking in nursing can impact the cost of healthcare., 4. lack of critical thinking skills in nursing can cause a breakdown in communication within the interdisciplinary team., useful resources to improve critical thinking in nursing, youtube videos, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered by our expert, 1. will lack of critical thinking impact my nursing career, 2. usually, how long does it take for a nurse to improve their critical thinking skills, 3. do all types of nurses require excellent critical thinking skills, 4. how can i assess my critical thinking skills in nursing.

• Ask relevant questions • Justify opinions • Address and evaluate multiple points of view • Explain assumptions and reasons related to your choice of patient care options

5. Can I Be a Nurse If I Cannot Think Critically?

The Value of Critical Thinking in Nursing

- How Nurses Use Critical Thinking

- How to Improve Critical Thinking

- Common Mistakes

Some experts describe a person’s ability to question belief systems, test previously held assumptions, and recognize ambiguity as evidence of critical thinking. Others identify specific skills that demonstrate critical thinking, such as the ability to identify problems and biases, infer and draw conclusions, and determine the relevance of information to a situation.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN, has been a critical care nurse for 10 years in neurological trauma nursing and cardiovascular and surgical intensive care. He defines critical thinking as “necessary for problem-solving and decision-making by healthcare providers. It is a process where people use a logical process to gather information and take purposeful action based on their evaluation.”

“This cognitive process is vital for excellent patient outcomes because it requires that nurses make clinical decisions utilizing a variety of different lenses, such as fairness, ethics, and evidence-based practice,” he says.

How Do Nurses Use Critical Thinking?

Successful nurses think beyond their assigned tasks to deliver excellent care for their patients. For example, a nurse might be tasked with changing a wound dressing, delivering medications, and monitoring vital signs during a shift. However, it requires critical thinking skills to understand how a difference in the wound may affect blood pressure and temperature and when those changes may require immediate medical intervention.

Nurses care for many patients during their shifts. Strong critical thinking skills are crucial when juggling various tasks so patient safety and care are not compromised.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN, is a nurse educator with a clinical background in surgical-trauma adult critical care, where critical thinking and action were essential to the safety of her patients. She talks about examples of critical thinking in a healthcare environment, saying:

“Nurses must also critically think to determine which patient to see first, which medications to pass first, and the order in which to organize their day caring for patients. Patient conditions and environments are continually in flux, therefore nurses must constantly be evaluating and re-evaluating information they gather (assess) to keep their patients safe.”

The COVID-19 pandemic created hospital care situations where critical thinking was essential. It was expected of the nurses on the general floor and in intensive care units. Crystal Slaughter is an advanced practice nurse in the intensive care unit (ICU) and a nurse educator. She observed critical thinking throughout the pandemic as she watched intensive care nurses test the boundaries of previously held beliefs and master providing excellent care while preserving resources.

“Nurses are at the patient’s bedside and are often the first ones to detect issues. Then, the nurse needs to gather the appropriate subjective and objective data from the patient in order to frame a concise problem statement or question for the physician or advanced practice provider,” she explains.

Top 5 Ways Nurses Can Improve Critical Thinking Skills

We asked our experts for the top five strategies nurses can use to purposefully improve their critical thinking skills.

Case-Based Approach

Slaughter is a fan of the case-based approach to learning critical thinking skills.

In much the same way a detective would approach a mystery, she mentors her students to ask questions about the situation that help determine the information they have and the information they need. “What is going on? What information am I missing? Can I get that information? What does that information mean for the patient? How quickly do I need to act?”

Consider forming a group and working with a mentor who can guide you through case studies. This provides you with a learner-centered environment in which you can analyze data to reach conclusions and develop communication, analytical, and collaborative skills with your colleagues.

Practice Self-Reflection

Rhoads is an advocate for self-reflection. “Nurses should reflect upon what went well or did not go well in their workday and identify areas of improvement or situations in which they should have reached out for help.” Self-reflection is a form of personal analysis to observe and evaluate situations and how you responded.

This gives you the opportunity to discover mistakes you may have made and to establish new behavior patterns that may help you make better decisions. You likely already do this. For example, after a disagreement or contentious meeting, you may go over the conversation in your head and think about ways you could have responded.

It’s important to go through the decisions you made during your day and determine if you should have gotten more information before acting or if you could have asked better questions.

During self-reflection, you may try thinking about the problem in reverse. This may not give you an immediate answer, but can help you see the situation with fresh eyes and a new perspective. How would the outcome of the day be different if you planned the dressing change in reverse with the assumption you would find a wound infection? How does this information change your plan for the next dressing change?

Develop a Questioning Mind

McGowan has learned that “critical thinking is a self-driven process. It isn’t something that can simply be taught. Rather, it is something that you practice and cultivate with experience. To develop critical thinking skills, you have to be curious and inquisitive.”

To gain critical thinking skills, you must undergo a purposeful process of learning strategies and using them consistently so they become a habit. One of those strategies is developing a questioning mind. Meaningful questions lead to useful answers and are at the core of critical thinking .

However, learning to ask insightful questions is a skill you must develop. Faced with staff and nursing shortages , declining patient conditions, and a rising number of tasks to be completed, it may be difficult to do more than finish the task in front of you. Yet, questions drive active learning and train your brain to see the world differently and take nothing for granted.

It is easier to practice questioning in a non-stressful, quiet environment until it becomes a habit. Then, in the moment when your patient’s care depends on your ability to ask the right questions, you can be ready to rise to the occasion.

Practice Self-Awareness in the Moment

Critical thinking in nursing requires self-awareness and being present in the moment. During a hectic shift, it is easy to lose focus as you struggle to finish every task needed for your patients. Passing medication, changing dressings, and hanging intravenous lines all while trying to assess your patient’s mental and emotional status can affect your focus and how you manage stress as a nurse .

Staying present helps you to be proactive in your thinking and anticipate what might happen, such as bringing extra lubricant for a catheterization or extra gloves for a dressing change.

By staying present, you are also better able to practice active listening. This raises your assessment skills and gives you more information as a basis for your interventions and decisions.

Use a Process

As you are developing critical thinking skills, it can be helpful to use a process. For example:

- Ask questions.

- Gather information.

- Implement a strategy.

- Evaluate the results.

- Consider another point of view.

These are the fundamental steps of the nursing process (assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate). The last step will help you overcome one of the common problems of critical thinking in nursing — personal bias.

Common Critical Thinking Pitfalls in Nursing

Your brain uses a set of processes to make inferences about what’s happening around you. In some cases, your unreliable biases can lead you down the wrong path. McGowan places personal biases at the top of his list of common pitfalls to critical thinking in nursing.

“We all form biases based on our own experiences. However, nurses have to learn to separate their own biases from each patient encounter to avoid making false assumptions that may interfere with their care,” he says. Successful critical thinkers accept they have personal biases and learn to look out for them. Awareness of your biases is the first step to understanding if your personal bias is contributing to the wrong decision.

New nurses may be overwhelmed by the transition from academics to clinical practice, leading to a task-oriented mindset and a common new nurse mistake ; this conflicts with critical thinking skills.

“Consider a patient whose blood pressure is low but who also needs to take a blood pressure medication at a scheduled time. A task-oriented nurse may provide the medication without regard for the patient’s blood pressure because medication administration is a task that must be completed,” Slaughter says. “A nurse employing critical thinking skills would address the low blood pressure, review the patient’s blood pressure history and trends, and potentially call the physician to discuss whether medication should be withheld.”

Fear and pride may also stand in the way of developing critical thinking skills. Your belief system and worldview provide comfort and guidance, but this can impede your judgment when you are faced with an individual whose belief system or cultural practices are not the same as yours. Fear or pride may prevent you from pursuing a line of questioning that would benefit the patient. Nurses with strong critical thinking skills exhibit:

- Learn from their mistakes and the mistakes of other nurses

- Look forward to integrating changes that improve patient care

- Treat each patient interaction as a part of a whole

- Evaluate new events based on past knowledge and adjust decision-making as needed

- Solve problems with their colleagues

- Are self-confident

- Acknowledge biases and seek to ensure these do not impact patient care

An Essential Skill for All Nurses

Critical thinking in nursing protects patient health and contributes to professional development and career advancement. Administrative and clinical nursing leaders are required to have strong critical thinking skills to be successful in their positions.

By using the strategies in this guide during your daily life and in your nursing role, you can intentionally improve your critical thinking abilities and be rewarded with better patient outcomes and potential career advancement.

Frequently Asked Questions About Critical Thinking in Nursing

How are critical thinking skills utilized in nursing practice.

Nursing practice utilizes critical thinking skills to provide the best care for patients. Often, the patient’s cause of pain or health issue is not immediately clear. Nursing professionals need to use their knowledge to determine what might be causing distress, collect vital information, and make quick decisions on how best to handle the situation.

How does nursing school develop critical thinking skills?

Nursing school gives students the knowledge professional nurses use to make important healthcare decisions for their patients. Students learn about diseases, anatomy, and physiology, and how to improve the patient’s overall well-being. Learners also participate in supervised clinical experiences, where they practice using their critical thinking skills to make decisions in professional settings.

Do only nurse managers use critical thinking?

Nurse managers certainly use critical thinking skills in their daily duties. But when working in a health setting, anyone giving care to patients uses their critical thinking skills. Everyone — including licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced nurse practitioners —needs to flex their critical thinking skills to make potentially life-saving decisions.

Meet Our Contributors

Crystal Slaughter, DNP, APRN, ACNS-BC, CNE

Crystal Slaughter is a core faculty member in Walden University’s RN-to-BSN program. She has worked as an advanced practice registered nurse with an intensivist/pulmonary service to provide care to hospitalized ICU patients and in inpatient palliative care. Slaughter’s clinical interests lie in nursing education and evidence-based practice initiatives to promote improving patient care.

Jenna Liphart Rhoads, Ph.D., RN

Jenna Liphart Rhoads is a nurse educator and freelance author and editor. She earned a BSN from Saint Francis Medical Center College of Nursing and an MS in nursing education from Northern Illinois University. Rhoads earned a Ph.D. in education with a concentration in nursing education from Capella University where she researched the moderation effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship of stress and GPA in military veteran nursing students. Her clinical background includes surgical-trauma adult critical care, interventional radiology procedures, and conscious sedation in adult and pediatric populations.

Nicholas McGowan, BSN, RN, CCRN

Nicholas McGowan is a critical care nurse with 10 years of experience in cardiovascular, surgical intensive care, and neurological trauma nursing. McGowan also has a background in education, leadership, and public speaking. He is an online learner who builds on his foundation of critical care nursing, which he uses directly at the bedside where he still practices. In addition, McGowan hosts an online course at Critical Care Academy where he helps nurses achieve critical care (CCRN) certification.

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

Cultivating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

Published: 06 January 2019

Critical thinking skills have been linked to improved patient outcomes, better quality patient care and improved safety outcomes in healthcare (Jacob et al. 2017).

Given this, it's necessary for educators in healthcare to stimulate and lead further dialogue about how these skills are taught , assessed and integrated into the design and development of staff and nurse education and training programs (Papp et al. 2014).

So, what exactly is critical thinking and how can healthcare educators cultivate it amongst their staff?

What is Critical Thinking?

In general terms, ‘ critical thinking ’ is often used, and perhaps confused, with problem-solving and clinical decision-making skills .

In practice, however, problem-solving tends to focus on the identification and resolution of a problem, whilst critical thinking goes beyond this to incorporate asking skilled questions and critiquing solutions .

Several formal definitions of critical thinking can be found in literature, but in the view of Kahlke and Eva (2018), most of these definitions have limitations. That said, Papp et al. (2014) offer a useful starting point, suggesting that critical thinking is:

‘The ability to apply higher order cognitive skills and the disposition to be deliberate about thinking that leads to action that is logical and appropriate.’

The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) expands on this and suggests that:

‘Critical thinking is that mode of thinking, about any subject, content, or problem, in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully analysing, assessing, and reconstructing it.’

They go on to suggest that critical thinking is:

- Self-directed

- Self-disciplined

- Self-monitored

- Self-corrective.

Key Qualities and Characteristics of a Critical Thinker

Given that critical thinking is a process that encompasses conceptualisation , application , analysis , synthesis , evaluation and reflection , what qualities should be expected from a critical thinker?

In answering this question, Fortepiani (2018) suggests that critical thinkers should be able to:

- Formulate clear and precise questions

- Gather, assess and interpret relevant information

- Reach relevant well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

- Think open-mindedly, recognising their own assumptions

- Communicate effectively with others on solutions to complex problems.

All of these qualities are important, however, good communication skills are generally considered to be the bedrock of critical thinking. Why? Because they help to create a dialogue that invites questions, reflections and an open-minded approach, as well as generating a positive learning environment needed to support all forms of communication.

Lippincott Solutions (2018) outlines a broad spectrum of characteristics attributed to strong critical thinkers. They include:

- Inquisitiveness with regard to a wide range of issues

- A concern to become and remain well-informed

- Alertness to opportunities to use critical thinking

- Self-confidence in one’s own abilities to reason

- Open mindedness regarding divergent world views

- Flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions

- Understanding the opinions of other people

- Fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning

- Honesty in facing one’s own biases, prejudices, stereotypes or egocentric tendencies

- A willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted.

Papp et al. (2014) also helpfully suggest that the following five milestones can be used as a guide to help develop competency in critical thinking:

Stage 1: Unreflective Thinker

At this stage, the unreflective thinker can’t examine their own actions and cognitive processes and is unaware of different approaches to thinking.

Stage 2: Beginning Critical Thinker

Here, the learner begins to think critically and starts to recognise cognitive differences in other people. However, external motivation is needed to sustain reflection on the learners’ own thought processes.

Stage 3: Practicing Critical Thinker

By now, the learner is familiar with their own thinking processes and makes a conscious effort to practice critical thinking.

Stage 4: Advanced Critical Thinker

As an advanced critical thinker, the learner is able to identify different cognitive processes and consciously uses critical thinking skills.

Stage 5: Accomplished Critical Thinker

At this stage, the skilled critical thinker can take charge of their thinking and habitually monitors, revises and rethinks approaches for continual improvement of their cognitive strategies.

Facilitating Critical Thinking in Healthcare

A common challenge for many educators and facilitators in healthcare is encouraging students to move away from passive learning towards active learning situations that require critical thinking skills.

Just as there are similarities among the definitions of critical thinking across subject areas and levels, there are also several generally recognised hallmarks of teaching for critical thinking . These include:

- Promoting interaction among students as they learn

- Asking open ended questions that do not assume one right answer

- Allowing sufficient time to reflect on the questions asked or problems posed

- Teaching for transfer - helping learners to see how a newly acquired skill can apply to other situations and experiences.

(Lippincott Solutions 2018)

Snyder and Snyder (2008) also make the point that it’s helpful for educators and facilitators to be aware of any initial resistance that learners may have and try to guide them through the process. They should aim to create a learning environment where learners can feel comfortable thinking through an answer rather than simply having an answer given to them.

Examples include using peer coaching techniques , mentoring or preceptorship to engage students in active learning and critical thinking skills, or integrating project-based learning activities that require students to apply their knowledge in a realistic healthcare environment.

Carvalhoa et al. (2017) also advocate problem-based learning as a widely used and successful way of stimulating critical thinking skills in the learner. This view is echoed by Tsui-Mei (2015), who notes that critical thinking, systematic analysis and curiosity significantly improve after practice-based learning .

Integrating Critical Thinking Skills Into Curriculum Design

Most educators agree that critical thinking can’t easily be developed if the program curriculum is not designed to support it. This means that a deep understanding of the nature and value of critical thinking skills needs to be present from the outset of the curriculum design process , and not just bolted on as an afterthought.

In the view of Fortepiani (2018), critical thinking skills can be summarised by the statement that 'thinking is driven by questions', which means that teaching materials need to be designed in such a way as to encourage students to expand their learning by asking questions that generate further questions and stimulate the thinking process. Ideal questions are those that:

- Embrace complexity

- Challenge assumptions and points of view

- Question the source of information

- Explore variable interpretations and potential implications of information.

To put it another way, asking questions with limiting, thought-stopping answers inhibits the development of critical thinking. This means that educators must ideally be critical thinkers themselves .

Drawing these threads together, The Foundation for Critical Thinking (2017) offers us a simple reminder that even though it’s human nature to be ‘thinking’ most of the time, most thoughts, if not guided and structured, tend to be biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or even prejudiced.

They also note that the quality of work depends precisely on the quality of the practitioners’ thought processes. Given that practitioners are being asked to meet the challenge of ever more complex care, the importance of cultivating critical thinking skills, alongside advanced problem-solving skills , seems to be taking on new importance.

Additional Resources

- The Emotionally Intelligent Nurse | Ausmed Article

- Refining Competency-Based Assessment | Ausmed Article

- Socratic Questioning in Healthcare | Ausmed Article

- Carvalhoa, D P S R P et al. 2017, 'Strategies Used for the Promotion of Critical Thinking in Nursing Undergraduate Education: A Systematic Review', Nurse Education Today , vol. 57, pp. 103-10, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0260691717301715

- Fortepiani, L A 2017, 'Critical Thinking or Traditional Teaching For Health Professionals', PECOP Blog , 16 January, viewed 7 December 2018, https://blog.lifescitrc.org/pecop/2017/01/16/critical-thinking-or-traditional-teaching-for-health-professions/

- Jacob, E, Duffield, C & Jacob, D 2017, 'A Protocol For the Development of a Critical Thinking Assessment Tool for Nurses Using a Delphi Technique', Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 73, no. 8, pp. 1982-1988, viewed 7 December 2018, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.13306

- Kahlke, R & Eva, K 2018, 'Constructing Critical Thinking in Health Professional Education', Perspectives on Medical Education , vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 156-165, viewed 7 December 2018, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40037-018-0415-z

- Lippincott Solutions 2018, 'Turning New Nurses Into Critical Thinkers', Lippincott Solutions , viewed 10 December 2018, https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/expert-insights/turning-new-nurses-into-critical-thinkers

- Papp, K K 2014, 'Milestones of Critical Thinking: A Developmental Model for Medicine and Nursing', Academic Medicine , vol. 89, no. 5, pp. 715-720, https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2014/05000/Milestones_of_Critical_Thinking___A_Developmental.14.aspx

- Snyder, L G & Snyder, M J 2008, 'Teaching Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills', The Delta Pi Epsilon Journal , vol. L, no. 2, pp. 90-99, viewed 7 December 2018, https://dme.childrenshospital.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Optional-_Teaching-Critical-Thinking-and-Problem-Solving-Skills.pdf

- The Foundation for Critical Thinking 2017, Defining Critical Thinking , The Foundation for Critical Thinking, viewed 7 December 2018, https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/our-conception-of-critical-thinking/411

- Tsui-Mei, H, Lee-Chun, H & Chen-Ju MSN, K 2015, 'How Mental Health Nurses Improve Their Critical Thinking Through Problem-Based Learning', Journal for Nurses in Professional Development , vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 170-175, viewed 7 December 2018, https://journals.lww.com/jnsdonline/Abstract/2015/05000/How_Mental_Health_Nurses_Improve_Their_Critical.8.aspx

Anne Watkins View profile

Help and feedback, publications.

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

An official website of the Department of Health & Human Services

- Search All AHRQ Sites

- Email Updates

1. Use quotes to search for an exact match of a phrase.

2. Put a minus sign just before words you don't want.

3. Enter any important keywords in any order to find entries where all these terms appear.

- The PSNet Collection

- All Content

- Perspectives

- Current Weekly Issue

- Past Weekly Issues

- Curated Libraries

- Clinical Areas

- Patient Safety 101

- The Fundamentals

- Training and Education

- Continuing Education

- WebM&M: Case Studies

- Training Catalog

- Submit a Case

- Improvement Resources

- Innovations

- Submit an Innovation

- About PSNet

- Editorial Team

- Technical Expert Panel

Developing critical thinking skills for delivering optimal care

Scott IA, Hubbard RE, Crock C, et al. Developing critical thinking skills for delivering optimal care. Intern Med J. 2021;51(4):488-493. doi: 10.1111/imj.15272

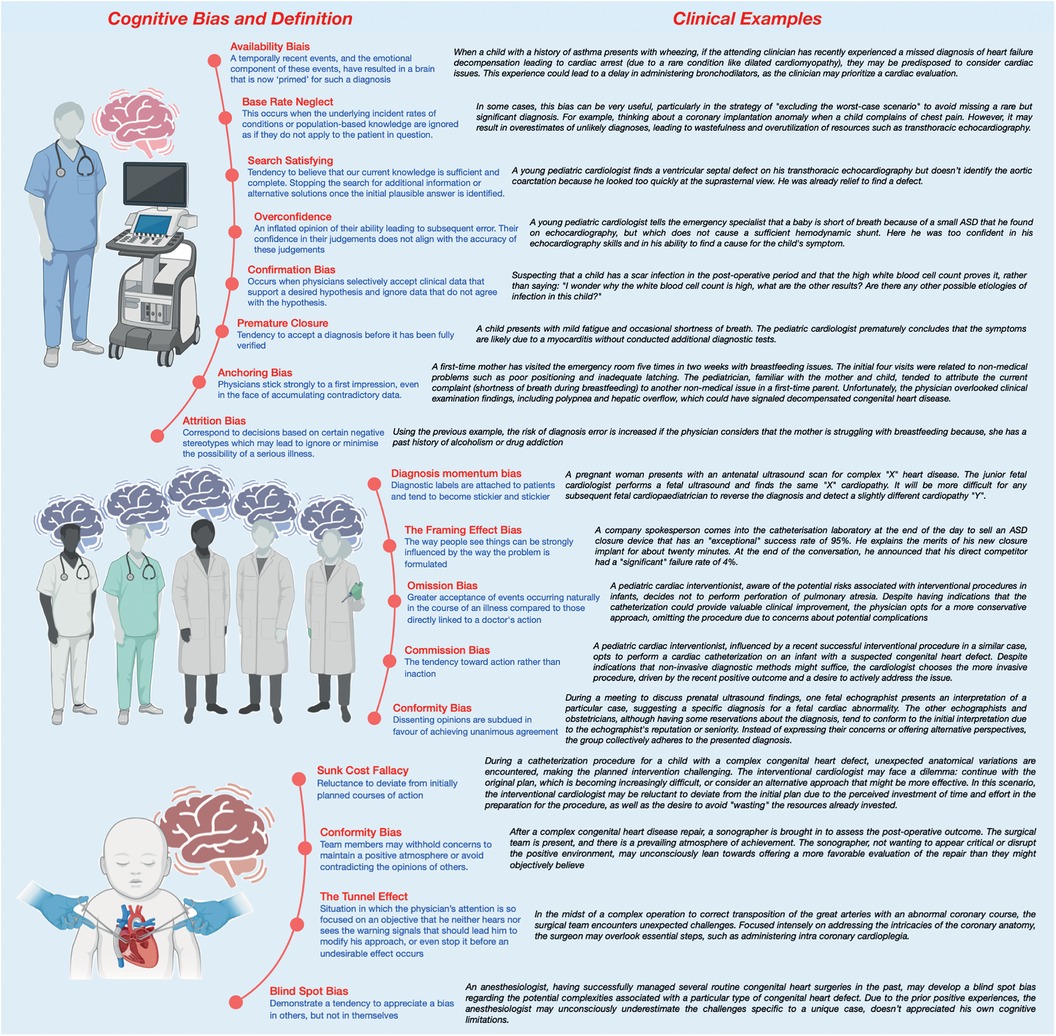

Sound critical thinking skills can help clinicians avoid cognitive biases and diagnostic errors. This article describes three critical thinking skills essential to effective clinical care – clinical reasoning, evidence-informed decision-making, and systems thinking – and approaches to develop these skills during clinician training.

Medication use and cognitive impairment among residents of aged care facilities. June 23, 2021

COVID-19 pandemic and the tension between the need to act and the need to know. October 14, 2020

Choosing wisely in clinical practice: embracing critical thinking, striving for safer care. April 6, 2022

Scoping review of studies evaluating frailty and its association with medication harm. June 22, 2022

Countering cognitive biases in minimising low value care. June 7, 2017

'More than words' - interpersonal communication, cognitive bias and diagnostic errors. August 11, 2021

A partially structured postoperative handoff protocol improves communication in 2 mixed surgical intensive care units: findings from the Handoffs and Transitions in Critical Care (HATRICC) prospective cohort study. February 6, 2019

Enabling a learning healthcare system with automated computer protocols that produce replicable and personalized clinician actions. August 4, 2021

Analysis of lawsuits related to diagnostic errors from point-of-care ultrasound in internal medicine, paediatrics, family medicine and critical care in the USA. June 24, 2020

Developing and aligning a safety event taxonomy for inpatient psychiatry. July 13, 2022

Changes in unprofessional behaviour, teamwork, and co-operation among hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. September 28, 2022

Pharmacists reducing medication risk in medical outpatient clinics: a retrospective study of 18 clinics. March 8, 2023

Prevalence and causes of diagnostic errors in hospitalized patients under investigation for COVID-19. April 12, 2023

Barriers to accessing nighttime supervisors: a national survey of internal medicine residents. March 17, 2021

Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016 March 3, 2017

Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among frontline health care personnel in a multistate hospital network--13 academic medical centers, April-June 2020. September 23, 2020

Transforming the medication regimen review process using telemedicine to prevent adverse events. December 16, 2020

The MedSafer study-electronic decision support for deprescribing in hospitalized older adults: a cluster randomized clinical trial. February 2, 2022

Perceived patient safety culture in a critical care transport program. July 31, 2013

Video-based communication assessment of physician error disclosure skills by crowdsourced laypeople and patient advocates who experienced medical harm: reliability assessment with generalizability theory. May 18, 2022

Implementation of the I-PASS handoff program in diverse clinical environments: a multicenter prospective effectiveness implementation study. November 16, 2022

Patient harm from cardiovascular medications. August 25, 2021

Delays in diagnosis, treatment, and surgery: root causes, actions taken, and recommendations for healthcare improvement. June 1, 2022

Influence of opioid prescription policy on overdoses and related adverse effects in a primary care population. May 19, 2021

Evaluation of a second victim peer support program on perceptions of second victim experiences and supportive resources in pediatric clinical specialties using the second victim experience and support tool (SVEST). November 3, 2021

Diagnostic errors in hospitalized adults who died or were transferred to intensive care. January 17, 2024

Estimation of breast cancer overdiagnosis in a U.S. breast screening cohort. March 16, 2022

Multiple meanings of resilience: health professionals' experiences of a dual element training intervention designed to help them prepare for coping with error. March 31, 2021

Care coordination strategies and barriers during medication safety incidents: a qualitative, cognitive task analysis. March 10, 2021

TRIAD IX: can a patient testimonial safely help ensure prehospital appropriate critical versus end-of-life care? September 15, 2021

An act of performance: exploring residents' decision-making processes to seek help. April 14, 2021

Preventing home medication administration errors. March 14, 2022

A randomized trial of a multifactorial strategy to prevent serious fall injuries. July 29, 2020

Clinical predictors for unsafe direct discharge home patients from intensive care units. October 21, 2020

Association between limiting the number of open records in a tele-critical care setting and retract-reorder errors. July 21, 2021

Standardized assessment of medication reconciliation in post-acute care. April 27, 2022

Estimating the economic cost of nurse sensitive adverse events amongst patients in medical and surgical settings. June 16, 2021

Survey of nurses' experiences applying The Joint Commission's medication management titration standards. November 3, 2021

Effectiveness of acute care remote triage systems: a systematic review. February 5, 2020

Hospital ward adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey of academic medical centers. September 23, 2020

Physician task load and the risk of burnout among US physicians in a national survey. December 2, 2020

Patient and physician perspectives of deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications in older adults with a history of falls: a qualitative study. May 5, 2021

We asked the experts: the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist and the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations for content and implementation adaptations. March 17, 2021

Association between surgeon technical skills and patient outcomes. September 9, 2020

Influence of psychological safety and organizational support on the impact of humiliation on trainee well-being. June 8, 2022

Developing the Safer Dx Checklist of Ten Safety Recommendations for Health Care Organizations to address diagnostic errors. October 12, 2022

Comparison of health care worker satisfaction before vs after implementation of a communication and optimal resolution program in acute care hospitals. April 5, 2023

Not overstepping professional boundaries: the challenging role of nurses in simulated error disclosures. September 21, 2011

Temporal associations between EHR-derived workload, burnout, and errors: a prospective cohort study. July 20, 2022

Adherence to national guidelines for timeliness of test results communication to patients in the Veterans Affairs health care system. May 4, 2022

Deferral of care for serious non-COVID-19 conditions: a hidden harm of COVID-19. November 18, 2020

An observational study of postoperative handoff standardization failures. June 23, 2021

Content analysis of patient safety incident reports for older adult patient transfers, handovers, and discharges: do they serve organizations, staff, or patients? January 8, 2020

Exploring the impact of employee engagement and patient safety. September 14, 2022

Deprescribing for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. September 16, 2020

The abrupt expansion of ambulatory telemedicine: implications for patient safety. February 9, 2022

Nurse's Achilles Heel: using big data to determine workload factors that impact near misses. April 14, 2021

A diagnostic time-out to improve differential diagnosis in pediatric abdominal pain. July 14, 2021

What safety events are reported for ambulatory care? Analysis of incident reports from a patient safety organization. October 21, 2020

Expert consensus on currently accepted measures of harm. September 9, 2020

The July Effect in podiatric medicine and surgery residency. July 14, 2021

Missed nursing care in the critical care unit, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative cross-sectional study. June 22, 2022

The calm before the storm: utilizing in situ simulation to evaluate for preparedness of an alternative care hospital during COVID-19 pandemic. June 2, 2021

The association between nurse staffing and omissions in nursing care: a systematic review. July 11, 2018

Creating a learning health system for improving diagnostic safety: pragmatic insights from US health care organizations. June 22, 2022

Effect of pharmacist counseling intervention on health care utilization following hospital discharge: a randomized control trial. June 8, 2016

Impact of the initial response to COVID-19 on long-term care for people with intellectual disability: an interrupted time series analysis of incident reports. October 14, 2020

Pediatric surgical errors: a systematic scoping review. July 20, 2022

Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. December 20, 2020

Accuracy of practitioner estimates of probability of diagnosis before and after testing. May 5, 2021

Recommendations for the safe, effective use of adaptive CDS in the US healthcare system: an AMIA position paper. April 21, 2021

Impact of interoperability of smart infusion pumps and an electronic medical record in critical care. September 23, 2020

Decreased incidence of cesarean surgical site infection rate with hospital-wide perioperative bundle. September 29, 2021

Association of diagnostic stewardship for blood cultures in critically ill children with culture rates, antibiotic use, and patient outcomes: results of the Bright STAR Collaborative. May 18, 2022

Second victim experiences of nurses in obstetrics and gynaecology: a Second Victim Experience and Support Tool Survey December 23, 2020

Understanding the second victim experience among multidisciplinary providers in obstetrics and gynecology. May 19, 2021

eSIMPLER: a dynamic, electronic health record-integrated checklist for clinical decision support during PICU daily rounds. June 16, 2021

Treatment patterns and clinical outcomes after the introduction of the Medicare Sepsis Performance Measure (SEP-1). May 5, 2021

Organizational safety climate and job enjoyment in hospital surgical teams with and without crew resource management training, January 26, 2022

Evaluation of effectiveness and safety of pharmacist independent prescribers in care homes: cluster randomised controlled trial. March 1, 2023

The Critical Care Safety Study: the incidence and nature of adverse events and serious medical errors in intensive care. August 24, 2005

Safety II behavior in a pediatric intensive care unit. August 1, 2018

Diagnosis of physical and mental health conditions in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. October 21, 2020

The working hours of hospital staff nurses and patient safety. January 9, 2005

Effects of tall man lettering on the visual behaviour of critical care nurses while identifying syringe drug labels: a randomised in situ simulation. April 20, 2022

Family Input for Quality and Safety (FIQS): using mobile technology for in-hospital reporting from families and patients. March 2, 2022

Improving self-reported empathy and communication skills through harm in healthcare response training. January 26, 2022

Bundle interventions including nontechnical skills for surgeons can reduce operative time and improve patient safety. December 9, 2020

COVID-19: an emerging threat to antibiotic stewardship in the emergency department. October 21, 2020

Predicting avoidable hospital events in Maryland. December 1, 2021

Association between in-clinic opioid administration and discharge opioid prescription in urgent care: a retrospective cohort study. February 17, 2021

Why do hospital prescribers continue antibiotics when it is safe to stop? Results of a choice experiment survey. September 2, 2020

Specificity of computerized physician order entry has a significant effect on the efficiency of workflow for critically ill patients. April 21, 2005

COVID-19: patient safety and quality improvement skills to deploy during the surge. June 24, 2020

Patient safety skills in primary care: a national survey of GP educators. February 4, 2015

Implementing human factors in anaesthesia: guidance for clinicians, departments and hospitals: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society and the Association of Anaesthetists. March 1, 2023

Can an electronic prescribing system detect doctors who are more likely to make a serious prescribing error? June 8, 2011

Training in safe opioid prescribing and treatment of opioid use disorder in internal medicine residencies: a national survey of program directors. October 12, 2022

Diagnostic discordance, health information exchange, and inter-hospital transfer outcomes: a population study. June 20, 2018

What has been the impact of Covid-19 on safety culture? A case study from a large metropolitan healthcare trust. September 2, 2020

Racial and ethnic harm in patient care is a patient safety issue. May 15, 2024

All in Her Head. The Truth and Lies Early Medicine Taught Us About Women's Bodies and Why It Matters Today. March 20, 2024

The racial disparities in maternal mortality and impact of structural racism and implicit racial bias on pregnant Black women: a review of the literature. December 6, 2023

A scoping review exploring the confidence of healthcare professionals in assessing all skin tones. October 4, 2023

Patient safety in palliative care at the end of life from the perspective of complex thinking. August 16, 2023

Only 1 in 5 people with opioid addiction get the medications to treat it, study finds. August 16, 2023

Factors influencing in-hospital prescribing errors: a systematic review. July 19, 2023

Introducing second-year medical students to diagnostic reasoning concepts and skills via a virtual curriculum. June 28, 2023

Context matters: toward a multilevel perspective on context in clinical reasoning and error. June 21, 2023

The good, the bad, and the ugly: operative staff perspectives of surgeon coping with intraoperative errors. June 14, 2023

Explicitly addressing implicit bias on inpatient rounds: student and faculty reflections. June 7, 2023

The time is now: addressing implicit bias in obstetrics and gynecology education. May 17, 2023

Listen to the whispers before they become screams: addressing Black maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. May 3, 2023

Annual Perspective

Formalizing the hidden curriculum of performance enhancing errors. March 22, 2023

Implicit racial bias, health care provider attitudes, and perceptions of health care quality among African American college students in Georgia, USA. January 18, 2023

Structural racism and impact on sickle cell disease: sickle cell lives matter. January 11, 2023

The REPAIR Project: a prospectus for change toward racial justice in medical education and health sciences research: REPAIR project steering committee. January 11, 2023

Using the Assessment of Reasoning Tool to facilitate feedback about diagnostic reasoning. January 11, 2023

Exploring the intersection of structural racism and ageism in healthcare. December 7, 2022

Calibrate Dx: A Resource to Improve Diagnostic Decisions. October 19, 2022

Improved Diagnostic Accuracy Through Probability-Based Diagnosis. September 28, 2022

Medical malpractice lawsuits involving trainees in obstetrics and gynecology in the USA. September 21, 2022

A state-of-the-art review of speaking up in healthcare. August 24, 2022

Skin cancer is a risk no matter the skin tone. But it may be overlooked in people with dark skin. August 17, 2022

Oxford Professional Practice: Handbook of Patient Safety. July 27, 2022

Narrowing the mindware gap in medicine. July 20, 2022

From principles to practice: embedding clinical reasoning as a longitudinal curriculum theme in a medical school programme. June 15, 2022

A call to action: next steps to advance diagnosis education in the health professions. June 8, 2022

Does a suggested diagnosis in a general practitioners' referral question impact diagnostic reasoning: an experimental study. April 27, 2022

Connect With Us

Sign up for Email Updates

To sign up for updates or to access your subscriber preferences, please enter your email address below.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 Telephone: (301) 427-1364

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Electronic Policies

- HHS Digital Strategy

- HHS Nondiscrimination Notice

- Inspector General

- Plain Writing Act

- Privacy Policy

- Viewers & Players

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- The White House

- Don't have an account? Sign up to PSNet

Submit Your Innovations

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation.

Continue as a Guest

Track and save your innovation

in My Innovations

Edit your innovation as a draft

Continue Logged In

Please select your preferred way to submit an innovation. Note that even if you have an account, you can still choose to submit an innovation as a guest.

Continue logged in

New users to the psnet site.

Access to quizzes and start earning

CME, CEU, or Trainee Certification.

Get email alerts when new content

matching your topics of interest

in My Innovations.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Critical Thinking in Critical Care: Five Strategies to Improve Teaching and Learning in the Intensive Care Unit

Affiliations.

- 1 1 Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

- 2 2 Shapiro Institute for Education and Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; and.

- 3 3 Critical Care Medicine Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Massachusetts.

- PMID: 28157389

- PMCID: PMC5461985

- DOI: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-1009AS

Critical thinking, the capacity to be deliberate about thinking, is increasingly the focus of undergraduate medical education, but is not commonly addressed in graduate medical education. Without critical thinking, physicians, and particularly residents, are prone to cognitive errors, which can lead to diagnostic errors, especially in a high-stakes environment such as the intensive care unit. Although challenging, critical thinking skills can be taught. At this time, there is a paucity of data to support an educational gold standard for teaching critical thinking, but we believe that five strategies, routed in cognitive theory and our personal teaching experiences, provide an effective framework to teach critical thinking in the intensive care unit. The five strategies are: make the thinking process explicit by helping learners understand that the brain uses two cognitive processes: type 1, an intuitive pattern-recognizing process, and type 2, an analytic process; discuss cognitive biases, such as premature closure, and teach residents to minimize biases by expressing uncertainty and keeping differentials broad; model and teach inductive reasoning by utilizing concept and mechanism maps and explicitly teach how this reasoning differs from the more commonly used hypothetico-deductive reasoning; use questions to stimulate critical thinking: "how" or "why" questions can be used to coach trainees and to uncover their thought processes; and assess and provide feedback on learner's critical thinking. We believe these five strategies provide practical approaches for teaching critical thinking in the intensive care unit.

Keywords: cognitive errors; critical care; critical thinking; medical education.

PubMed Disclaimer

Five strategies to teach critical…

Five strategies to teach critical thinking skills in a critical care environment.

The revised Bloom’s taxonomy. This…

The revised Bloom’s taxonomy. This schematic, first created in 1956, depicts six levels…

Schematic representations of deductive (…

Schematic representations of deductive ( 1 ) and inductive ( 2 ) reasoning…

( A ) A mechanism…

( A ) A mechanism map of a 45-year-old man presenting with cough,…

- Teaching: A Newer Face. Dries DJ. Dries DJ. Air Med J. 2017 Nov-Dec;36(6):282-286. doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2017.09.006. Air Med J. 2017. PMID: 29132587 Review. No abstract available.

Similar articles

- Promoting Critical Thinking in Your Intensive Care Unit Team. Richards JB, Schwartzstein RM. Richards JB, et al. Crit Care Clin. 2022 Jan;38(1):113-127. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2021.08.002. Crit Care Clin. 2022. PMID: 34794626 Review.

- Teaching Clinical Reasoning and Critical Thinking: From Cognitive Theory to Practical Application. Richards JB, Hayes MM, Schwartzstein RM. Richards JB, et al. Chest. 2020 Oct;158(4):1617-1628. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.525. Epub 2020 May 22. Chest. 2020. PMID: 32450242 Review.

- Reclaiming magical incantation in graduate medical education. Katz JD, George DT. Katz JD, et al. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Mar;39(3):703-707. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04812-x. Epub 2019 Nov 14. Clin Rheumatol. 2020. PMID: 31724095 Review.

- Intensive Care Unit Educators: A Multicenter Evaluation of Behaviors Residents Value in Attending Physicians. Santhosh L, Jain S, Brady A, Sharp M, Carlos WG. Santhosh L, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017 Apr;14(4):513-516. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-996BC. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017. PMID: 28287827

- Current teaching and evaluation methods in critical care medicine: has the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education affected how we practice and teach in the intensive care unit? Chudgar SM, Cox CE, Que LG, Andolsek K, Knudsen NW, Clay AS. Chudgar SM, et al. Crit Care Med. 2009 Jan;37(1):49-60. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819265c8. Crit Care Med. 2009. PMID: 19050627