Definition of Evidence

Examples of evidence in literature, example #1: the bluest eye (by tony morrison).

“I talk about how I did not plant the seeds too deeply, how it was the fault of the earth, our land, our town. I even think now that the land of the entire country was hostile to marigolds that year. This soil is bad for certain kinds of flowers. Certain seeds it will not nurture, certain fruit it will not bear, and when the land kills of its own volition, we acquiesce and say the victim had no right to live.”

Morrison evidently analyzes the environment, as it has powerful effects on people. She provides strong evidence that that the Earth itself is not fertile for the marigold seeds. Likewise, people also cannot survive in an unfriendly environment.

Example #2: The Color of Water Juliet (By James McBride)

” ‘…while she weebled and wobbled and leaned, she did not fall. She responded with speed and motion. She would not stop moving.’ As she biked, walked, rode the bus all over the city, ‘she kept moving as if her life depended on it, which in some ways it did. She ran, as she had done most of her life, but this time she was running for her own sanity.’ “

Example #3: Educational Paragraph (By Anonymous)

“Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don’t matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.”

This is a best example of evidence, since the evidence is effectively incorporated into the text, as the author makes the link between her claim (question) and the evidence (logic), which is powerful.

Function of Evidence

Post navigation.

What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?

- I’ve just said that something happens—so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is?

- Why is this information important? Why does it matter?

- How is this idea related to my thesis? What connections exist between them? Does it support my thesis? If so, how does it do that?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

Answering these questions may help you explain how your evidence is related to your overall argument.

How can I incorporate evidence into my paper?

There are many ways to present your evidence. Often, your evidence will be included as text in the body of your paper, as a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sometimes you might include graphs, charts, or tables; excerpts from an interview; or photographs or illustrations with accompanying captions.

When you quote, you are reproducing another writer’s words exactly as they appear on the page. Here are some tips to help you decide when to use quotations:

- Quote if you can’t say it any better and the author’s words are particularly brilliant, witty, edgy, distinctive, a good illustration of a point you’re making, or otherwise interesting.

- Quote if you are using a particularly authoritative source and you need the author’s expertise to back up your point.

- Quote if you are analyzing diction, tone, or a writer’s use of a specific word or phrase.

- Quote if you are taking a position that relies on the reader’s understanding exactly what another writer says about the topic.

Be sure to introduce each quotation you use, and always cite your sources. See our handout on quotations for more details on when to quote and how to format quotations.

Like all pieces of evidence, a quotation can’t speak for itself. If you end a paragraph with a quotation, that may be a sign that you have neglected to discuss the importance of the quotation in terms of your argument. It’s important to avoid “plop quotations,” that is, quotations that are just dropped into your paper without any introduction, discussion, or follow-up.

Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you take a specific section of a text and put it into your own words. Putting it into your own words doesn’t mean just changing or rearranging a few of the author’s words: to paraphrase well and avoid plagiarism, try setting your source aside and restating the sentence or paragraph you have just read, as though you were describing it to another person. Paraphrasing is different than summary because a paraphrase focuses on a particular, fairly short bit of text (like a phrase, sentence, or paragraph). You’ll need to indicate when you are paraphrasing someone else’s text by citing your source correctly, just as you would with a quotation.

When might you want to paraphrase?

- Paraphrase when you want to introduce a writer’s position, but their original words aren’t special enough to quote.

- Paraphrase when you are supporting a particular point and need to draw on a certain place in a text that supports your point—for example, when one paragraph in a source is especially relevant.

- Paraphrase when you want to present a writer’s view on a topic that differs from your position or that of another writer; you can then refute writer’s specific points in your own words after you paraphrase.

- Paraphrase when you want to comment on a particular example that another writer uses.

- Paraphrase when you need to present information that’s unlikely to be questioned.

When you summarize, you are offering an overview of an entire text, or at least a lengthy section of a text. Summary is useful when you are providing background information, grounding your own argument, or mentioning a source as a counter-argument. A summary is less nuanced than paraphrased material. It can be the most effective way to incorporate a large number of sources when you don’t have a lot of space. When you are summarizing someone else’s argument or ideas, be sure this is clear to the reader and cite your source appropriately.

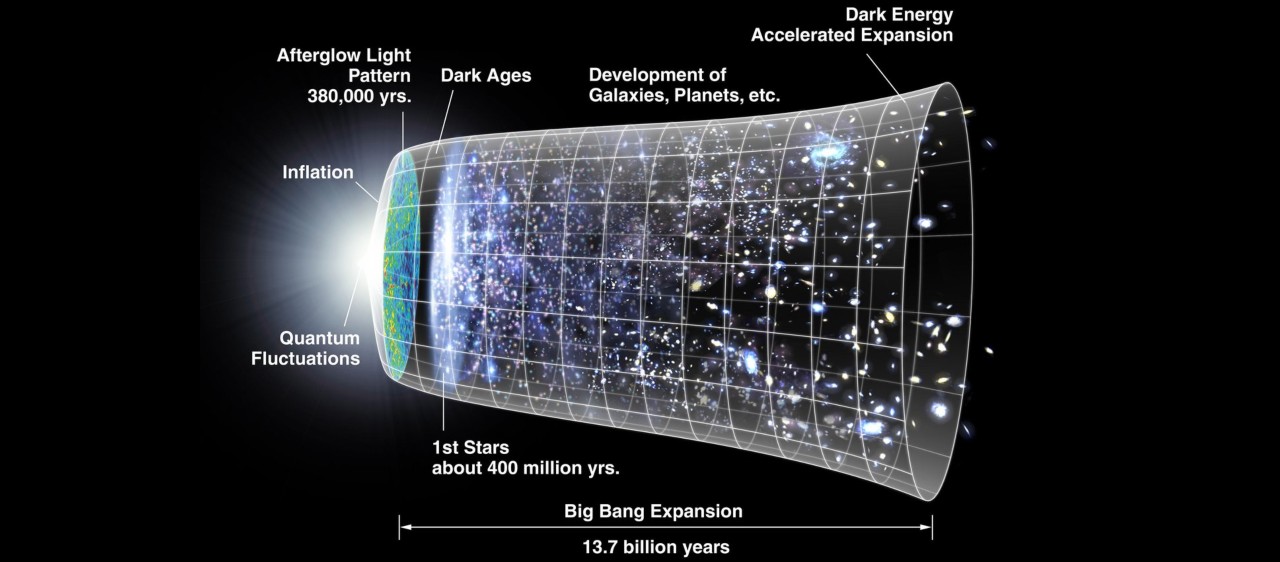

Statistics, data, charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations

Sometimes the best evidence for your argument is a hard fact or visual representation of a fact. This type of evidence can be a solid backbone for your argument, but you still need to create context for your reader and draw the connections you want them to make. Remember that statistics, data, charts, graph, photographs, and illustrations are all open to interpretation. Guide the reader through the interpretation process. Again, always, cite the origin of your evidence if you didn’t produce the material you are using yourself.

Do I need more evidence?

Let’s say that you’ve identified some appropriate sources, found some evidence, explained to the reader how it fits into your overall argument, incorporated it into your draft effectively, and cited your sources. How do you tell whether you’ve got enough evidence and whether it’s working well in the service of a strong argument or analysis? Here are some techniques you can use to review your draft and assess your use of evidence.

Make a reverse outline

A reverse outline is a great technique for helping you see how each paragraph contributes to proving your thesis. When you make a reverse outline, you record the main ideas in each paragraph in a shorter (outline-like) form so that you can see at a glance what is in your paper. The reverse outline is helpful in at least three ways. First, it lets you see where you have dealt with too many topics in one paragraph (in general, you should have one main idea per paragraph). Second, the reverse outline can help you see where you need more evidence to prove your point or more analysis of that evidence. Third, the reverse outline can help you write your topic sentences: once you have decided what you want each paragraph to be about, you can write topic sentences that explain the topics of the paragraphs and state the relationship of each topic to the overall thesis of the paper.

For tips on making a reverse outline, see our handout on organization .

Color code your paper

You will need three highlighters or colored pencils for this exercise. Use one color to highlight general assertions. These will typically be the topic sentences in your paper. Next, use another color to highlight the specific evidence you provide for each assertion (including quotations, paraphrased or summarized material, statistics, examples, and your own ideas). Lastly, use another color to highlight analysis of your evidence. Which assertions are key to your overall argument? Which ones are especially contestable? How much evidence do you have for each assertion? How much analysis? In general, you should have at least as much analysis as you do evidence, or your paper runs the risk of being more summary than argument. The more controversial an assertion is, the more evidence you may need to provide in order to persuade your reader.

Play devil’s advocate, act like a child, or doubt everything

This technique may be easiest to use with a partner. Ask your friend to take on one of the roles above, then read your paper aloud to them. After each section, pause and let your friend interrogate you. If your friend is playing devil’s advocate, they will always take the opposing viewpoint and force you to keep defending yourself. If your friend is acting like a child, they will question every sentence, even seemingly self-explanatory ones. If your friend is a doubter, they won’t believe anything you say. Justifying your position verbally or explaining yourself will force you to strengthen the evidence in your paper. If you already have enough evidence but haven’t connected it clearly enough to your main argument, explaining to your friend how the evidence is relevant or what it proves may help you to do so.

Common questions and additional resources

- I have a general topic in mind; how can I develop it so I’ll know what evidence I need? And how can I get ideas for more evidence? See our handout on brainstorming .

- Who can help me find evidence on my topic? Check out UNC Libraries .

- I’m writing for a specific purpose; how can I tell what kind of evidence my audience wants? See our handouts on audience , writing for specific disciplines , and particular writing assignments .

- How should I read materials to gather evidence? See our handout on reading to write .

- How can I make a good argument? Check out our handouts on argument and thesis statements .

- How do I tell if my paragraphs and my paper are well-organized? Review our handouts on paragraph development , transitions , and reorganizing drafts .

- How do I quote my sources and incorporate those quotes into my text? Our handouts on quotations and avoiding plagiarism offer useful tips.

- How do I cite my evidence? See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

- I think that I’m giving evidence, but my instructor says I’m using too much summary. How can I tell? Check out our handout on using summary wisely.

- I want to use personal experience as evidence, but can I say “I”? We have a handout on when to use “I.”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Miller, Richard E., and Kurt Spellmeyer. 2016. The New Humanities Reader , 5th ed. Boston: Cengage.

University of Maryland. 2019. “Research Using Primary Sources.” Research Guides. Last updated October 28, 2019. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/researchusingprimarysources .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Using Research and Evidence

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What type of evidence should I use?

There are two types of evidence.

First hand research is research you have conducted yourself such as interviews, experiments, surveys, or personal experience and anecdotes.

Second hand research is research you are getting from various texts that has been supplied and compiled by others such as books, periodicals, and Web sites.

Regardless of what type of sources you use, they must be credible. In other words, your sources must be reliable, accurate, and trustworthy.

How do I know if a source is credible?

You can ask the following questions to determine if a source is credible.

Who is the author? Credible sources are written by authors respected in their fields of study. Responsible, credible authors will cite their sources so that you can check the accuracy of and support for what they've written. (This is also a good way to find more sources for your own research.)

How recent is the source? The choice to seek recent sources depends on your topic. While sources on the American Civil War may be decades old and still contain accurate information, sources on information technologies, or other areas that are experiencing rapid changes, need to be much more current.

What is the author's purpose? When deciding which sources to use, you should take the purpose or point of view of the author into consideration. Is the author presenting a neutral, objective view of a topic? Or is the author advocating one specific view of a topic? Who is funding the research or writing of this source? A source written from a particular point of view may be credible; however, you need to be careful that your sources don't limit your coverage of a topic to one side of a debate.

What type of sources does your audience value? If you are writing for a professional or academic audience, they may value peer-reviewed journals as the most credible sources of information. If you are writing for a group of residents in your hometown, they might be more comfortable with mainstream sources, such as Time or Newsweek . A younger audience may be more accepting of information found on the Internet than an older audience might be.

Be especially careful when evaluating Internet sources! Never use Web sites where an author cannot be determined, unless the site is associated with a reputable institution such as a respected university, a credible media outlet, government program or department, or well-known non-governmental organizations. Beware of using sites like Wikipedia , which are collaboratively developed by users. Because anyone can add or change content, the validity of information on such sites may not meet the standards for academic research.

Encyclopedia

Writing with artificial intelligence.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - Professor of English - USF , Jennifer Janechek - IBM Quantum

Evidence is necessary to substantiate claims in workplace & academic writing. Learn to reason with evidence in workplace & academic writing. Review research and scholarship on the uses of evidence. Explore how evidence can help you communicate more clearly and persuasively.

Table of Contents

Evidence is

- information that a writer, speaker, knowledge maker . . . weaves into discourse in order to substantiate claims When writers make claims , critical readers expect them to substantiate those claims with evidence (see Argumentation )

- (see reader-based prose vs writer-based prose ).

Related Concepts: Argument ; Concrete, Sensory Language ; Claim ; Information, Data ;

How Do I know What Form of Evidence to Use?

When you think of the term evidence , what comes to mind? CSI ? Law and Order ? NCIS ?

Certainly, detectives and law enforcement officers use evidence to prove that a criminal is guilty. What’s more, they use different types of evidence to find and convict the offending person(s), such as eyewitness accounts, DNA, fingerprints, and material evidence.

Just as detectives use various types of evidence to study crime scenes, writers, speakers, and knowledge workers . . . use different types of evidence to help their audiences better understand their claims , interpretations , point of view , and conclusions .

In order to identify the types of evidence you’ll need for any given occasion , you need to engage in rhetorical analysis of your communication situation .

You want to focus on audience because different readers, different discourse communities , have unique and sometimes conflicting ideas about what constitutes reliable evidence. You’ll want to consider how emotionally charged the situation is.

What archive exists regarding the topic you are investigating?

What is the status of the current scholarly conversation on the topic ?

Regardless of the type used, all evidence serves the same general function: proof/confirmation bolsters a writer’s claims . The trick is to determine, during composing , what type of evidence will most help substantiate your claims .

Evidence as a Social, Cultural, Historical Artifact

Evidence is rooted in the epistemological assumptions that inform the interpretation and meaning-making processes of discourse communities .

Evidence vs Research

Students sometimes confuse evidence with research ; the two do not mean the same thing.

Whereas evidence refers to a something that supports a claim, research is something much broader: it’s an effort to have a scholarly conversation about a topic .

Research begets proof. Yet performing research should not just point you as a writer, speaker, knowledge maker . . . to useful quotes that you can use as support for claims in your writing.

Research should tell you about a conversation , one that began before you decided upon your project topic . When you incorporate research into a paper, you are integrating and responding to previous claims about your topic made by other writers. As such, it’s important to try to understand the main argument each source in a particular conversation is making, and these main arguments (and ensuing subclaims) can then be used as evidence—as support for your claims—in your paper. Let’s say for a bibliographic essay you decide to write about the Indian Mutiny. Well, as the Indian Mutiny began around 1857, people have been writing about the Mutiny since that time. Thus, it’s important to realize that by writing about the Indian Mutiny now, you’re contributing to an ongoing conversation. By doing research, you can see what’s already been said about this topic, decide what specific approach to the topic might be original and insightful, and determine what ideas from other writers provide an opening for you to assert your own claims.

Recommended Readings

Ho, H. L. (2021, October 8). The legal concept of evidence , In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2015/entries/evidence-legal/.

Related Articles:

Anecdote - anecdotal evidence, hypothetical evidence.

Types of Evidence

Recommended.

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Structured Revision – How to Revise Your Work

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

Page Design – How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Jennifer Janechek , Joseph M. Moxley

- Jennifer Janechek

- Joseph M. Moxley

Featured Articles

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

Using evidence.

Like a lawyer in a jury trial, a writer must convince her audience of the validity of her argument by using evidence effectively. As a writer, you must also use evidence to persuade your readers to accept your claims. But how do you use evidence to your advantage? By leading your reader through your reasoning.

The types of evidence you use change from discipline to discipline--you might use quotations from a poem or a literary critic, for example, in a literature paper; you might use data from an experiment in a lab report.

The process of putting together your argument is called analysis --it interprets evidence in order to support, test, and/or refine a claim . The chief claim in an analytical essay is called the thesis . A thesis provides the controlling idea for a paper and should be original (that is, not completely obvious), assertive, and arguable. A strong thesis also requires solid evidence to support and develop it because without evidence, a claim is merely an unsubstantiated idea or opinion.

This Web page will cover these basic issues (you can click or scroll down to a particular topic):

- Incorporating evidence effectively.

- Integrating quotations smoothly.

- Citing your sources.

Incorporating Evidence Into Your Essay

When should you incorporate evidence.

Once you have formulated your claim, your thesis (see the WTS pamphlet, " How to Write a Thesis Statement ," for ideas and tips), you should use evidence to help strengthen your thesis and any assertion you make that relates to your thesis. Here are some ways to work evidence into your writing:

- Offer evidence that agrees with your stance up to a point, then add to it with ideas of your own.

- Present evidence that contradicts your stance, and then argue against (refute) that evidence and therefore strengthen your position.

- Use sources against each other, as if they were experts on a panel discussing your proposition.

- Use quotations to support your assertion, not merely to state or restate your claim.

Weak and Strong Uses of Evidence

In order to use evidence effectively, you need to integrate it smoothly into your essay by following this pattern:

- State your claim.

- Give your evidence, remembering to relate it to the claim.

- Comment on the evidence to show how it supports the claim.

To see the differences between strong and weak uses of evidence, here are two paragraphs.

Weak use of evidence

Today, we are too self-centered. Most families no longer sit down to eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This is a weak example of evidence because the evidence is not related to the claim. What does the claim about self-centeredness have to do with families eating together? The writer doesn't explain the connection.

The same evidence can be used to support the same claim, but only with the addition of a clear connection between claim and evidence, and some analysis of the evidence cited.

Stronger use of evidence

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

This is a far better example, as the evidence is more smoothly integrated into the text, the link between the claim and the evidence is strengthened, and the evidence itself is analyzed to provide support for the claim.

Using Quotations: A Special Type of Evidence

One effective way to support your claim is to use quotations. However, because quotations involve someone else's words, you need to take special care to integrate this kind of evidence into your essay. Here are two examples using quotations, one less effective and one more so.

Ineffective Use of Quotation

Today, we are too self-centered. "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This example is ineffective because the quotation is not integrated with the writer's ideas. Notice how the writer has dropped the quotation into the paragraph without making any connection between it and the claim. Furthermore, she has not discussed the quotation's significance, which makes it difficult for the reader to see the relationship between the evidence and the writer's point.

A More Effective Use of Quotation

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much any more as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence, as James Gleick says in his book, Faster . "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

The second example is more effective because it follows the guidelines for incorporating evidence into an essay. Notice, too, that it uses a lead-in phrase (". . . as James Gleick says in his book, Faster ") to introduce the direct quotation. This lead-in phrase helps to integrate the quotation with the writer's ideas. Also notice that the writer discusses and comments upon the quotation immediately afterwards, which allows the reader to see the quotation's connection to the writer's point.

REMEMBER: Discussing the significance of your evidence develops and expands your paper!

Citing Your Sources

Evidence appears in essays in the form of quotations and paraphrasing. Both forms of evidence must be cited in your text. Citing evidence means distinguishing other writers' information from your own ideas and giving credit to your sources. There are plenty of general ways to do citations. Note both the lead-in phrases and the punctuation (except the brackets) in the following examples:

Quoting: According to Source X, "[direct quotation]" ([date or page #]).

Paraphrasing: Although Source Z argues that [his/her point in your own words], a better way to view the issue is [your own point] ([citation]).

Summarizing: In her book, Source P's main points are Q, R, and S [citation].

Your job during the course of your essay is to persuade your readers that your claims are feasible and are the most effective way of interpreting the evidence.

Questions to Ask Yourself When Revising Your Paper

- Have I offered my reader evidence to substantiate each assertion I make in my paper?

- Do I thoroughly explain why/how my evidence backs up my ideas?

- Do I avoid generalizing in my paper by specifically explaining how my evidence is representative?

- Do I provide evidence that not only confirms but also qualifies my paper's main claims?

- Do I use evidence to test and evolve my ideas, rather than to just confirm them?

- Do I cite my sources thoroughly and correctly?

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

Definition Essay

Definition Essay - Writing Guide, Examples and Tips

14 min read

Published on: Oct 9, 2020

Last updated on: Jan 31, 2024

People also read

Interesting Definition Essay Topics for Students

Definition Essay Outline - Format & Guide

Share this article

Many students struggle with writing definition essays due to a lack of clarity and precision in their explanations.

This obstructs them from effectively conveying the essence of the terms or concepts they are tasked with defining. Consequently, the essays may lack coherence, leaving readers confused and preventing them from grasping the intended meaning.

But don’t worry!

In this guide, we will delve into effective techniques and step-by-step approaches to help students craft an engaging definition essay.

Continue reading to learn the correct formation of a definition essay.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

On This Page On This Page -->

What is a Definition Essay?

Just as the name suggests, a definition essay defines and explains a term or a concept. Unlike a narrative essay, the purpose of writing this essay is only to inform the readers.

Writing this essay type can be deceivingly tricky. Some terms, concepts, and objects have concrete definitions when explained. In contrast others are solely based on the writerâs understanding and point of view.

A definition essay requires a writer to use different approaches when discussing a term. These approaches are the following:

- Denotation - It is when you provide a literal or academic definition of the term.

- Connotation - It is when the writer provides an implied meaning or definition of the term.

- Enumeration - For this approach, a list is employed to define a term or a concept.

- Analogy - It is a technique in which something is defined by implementing a comparison.

- Negation - It is when you define a term by stating what it is not.

A single or combination of approaches can be used in the essay.

Definition Essay Types

There are several types of definition essays that you may be asked to write, depending on the purpose and scope of the assignment.

In this section, we will discuss some of the most common types of definition essays.

Descriptive Definition Essay

This type of essay provides a detailed description of a term or concept, emphasizing its key features and characteristics.

The goal of a descriptive definition essay is to help readers understand the term or concept in a more profound way.

Stipulative Definition Essay

In a stipulative definition essay, the writer provides a unique definition of a term or concept. This type of essay is often used in academic settings to define a term in a particular field of study.

The goal of a stipulative definition essay is to provide a precise and clear definition that is specific to the context of the essay.

Analytical Definition Essay

This compare and contrast essay type involves analyzing a term or concept in-depth. Breaking it down into its component parts, and examining how they relate to each other.

The goal of an analytical definition essay is to provide a more nuanced and detailed understanding of the term or concept being discussed.

Persuasive Definition Essay

A persuasive definition essay is an argumentative essay that aims to persuade readers to accept a particular definition of a term or concept.

The writer presents their argument for the definition and uses evidence and examples to support their position.

Explanatory Definition Essay

An explanatory definition essay is a type of expository essay . It aims to explain a complex term or concept in a way that is easy to understand for the reader.

The writer breaks down the term or concept into simpler parts and provides examples and analogies to help readers understand it better.

Extended Definition Essay

An extended definition essay goes beyond the definition of a word or concept and provides a more in-depth analysis and explanation.

The goal of an extended definition essay is to provide a comprehensive understanding of a term, concept, or idea. This includes its history, origins, and cultural significance.

How to Write a Definition Essay?

Writing a definition essay is simple if you know the correct procedure. This essay, like all the other formal pieces of documents, requires substantial planning and effective execution.

The following are the steps involved in writing a definition essay effectively:

Instead of choosing a term that has a concrete definition available, choose a word that is complicated . Complex expressions have abstract concepts that require a writer to explore deeper. Moreover, make sure that different people perceive the term selected differently.

Once you have a word to draft your definition essay for, read the dictionary. These academic definitions are important as you can use them to compare your understanding with the official concept.

Drafting a definition essay is about stating the dictionary meaning and your explanation of the concept. So the writer needs to have some information about the term.

In addition to this, when exploring the term, make sure to check the termâs origin. The history of the word can make you discuss it in a better way.

Coming up with an exciting title for your essay is important. The essay topic will be the first thing that your readers will witness, so it should be catchy.

Creatively draft an essay topic that reflects meaning. In addition to this, the usage of the term in the title should be correctly done. The readers should get an idea of what the essay is about and what to expect from the document.

Now that you have a topic in hand, it is time to gather some relevant information. A definition essay is more than a mere explanation of the term. It represents the writerâs perception of the chosen term and the topic.

So having only personal opinions will not be enough to defend your point. Deeply research and gather information by consulting credible sources.

The gathered information needs to be organized to be understandable. The raw data needs to be arranged to give a structure to the content.

Here's a generic outline for a definition essay:

Provide an that grabs the reader's attention and introduces the term or concept you will be defining. that clearly defines the term or concept and previews the main points of the essay. , , or that will help the reader better understand the term or concept. to clarify the scope of your definition. or of the term or concept you are defining in detail. to illustrate your points. by differentiating your term or concept from similar terms or concepts. to illustrate the differences. of the term or concept. between the types, using examples and anecdotes to illustrate your points. , or to support your points. VII. Conclusion you have defined. that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. |

Are you searching for an in-depth guide on crafting a well-structured definition essay?Check out this definition essay outline blog!

6. Write the First Draft

Drafting each section correctly is a daunting task. Understanding what or what not to include in these sections requires a writer to choose wisely.

The start of your essay matters a lot. If it is on point and attractive, the readers will want to read the text. As the first part of the essay is the introduction , it is considered the first impression of your essay.

To write your definition essay introduction effectively, include the following information:

- Start your essay with a catchy hook statement that is related to the topic and the term chosen.

- State the generally known definition of the term. If the word chosen has multiple interpretations, select the most common one.

- Provide background information precisely. Determine the origin of the term and other relevant information.

- Shed light on the other unconventional concepts and definitions related to the term.

- Decide on the side or stance you want to pick in your essay and develop a thesis statement .

After briefly introducing the topic, fully explain the concept in the body section . Provide all the details and evidence that will support the thesis statement. To draft this section professionally, add the following information:

- A detailed explanation of the history of the term.

- Analysis of the dictionary meaning and usage of the term.

- A comparison and reflection of personal understanding and the researched data on the concept.

Once all the details are shared, give closure to your discussion. The last paragraph of the definition essay is the conclusion . The writer provides insight into the topic as a conclusion.

The concluding paragraphs include the following material:

- Summary of the important points.

- Restated thesis statement.

- A final verdict on the topic.

7. Proofread and Edit

Although the writing process ends with the concluding paragraph, there is an additional step. It is important to proofread the essay once you are done writing. Proofread and revise your document a couple of times to make sure everything is perfect.

Before submitting your assignment, make edits, and fix all mistakes and errors.

If you want to learn more about how to write a definition essay, here is a video guide for you!

Definition Essay Structure

The structure of a definition essay is similar to that of any other academic essay. It should consist of an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

However, the focus of a definition essay is on defining and explaining a particular term or concept.

In this section, we will discuss the structure of a definition essay in detail.

Introduction

Get the idea of writing an introduction for a definition essay with this example:

"Have you ever wondered what it truly means to be a hero?" |

Body Paragraphs

Here is an example of how to craft your definition essay body paragraph:

Heroes are individuals who demonstrate courage, selflessness, and a commitment to helping others. They often risk their own safety to protect others or achieve a noble goal. |

Types of the Term/Concept

If applicable, the writer may want to include a section that discusses the different types or categories of the term or concept being defined.

This section should explain the similarities and differences between the types, using examples and anecdotes to illustrate the points.

This section could explore the different categories of heroes, such as those who are recognized for their bravery in the face of danger, those who inspire others through their deeds, or those who make a difference in their communities through volunteering. |

Examples of the Term/Concept in Action

The writer should also include real-life examples of the term or concept being defined in action.

This will help the reader better understand the term or concept in context and how it is used in everyday life.

This could include stories of individuals who risked their lives to save others, such as firefighters who rushed into the Twin Towers on 9/11 or civilians who pulled people from a burning car. |

Conclusion

This example will help you writing a conclusion fo you essay:

Heroes are defined by their courage, selflessness, and commitment to helping others. There are many different types of heroes, but they all share these key features. |

Definition Essay Examples

It is important to go through some examples and samples before writing an essay. This is to understand the writing process and structure of the assigned task well.

Following are some examples of definition essays to give our students a better idea of the concept.

Understanding the Definition Essay

Definition Essay Example

Definition Essay About Friendship

Definition Essay About Love

Family Definition Essay

Success Definition Essay

Beauty Definition Essay

Definition Essay Topics

Selecting the right topic is challenging for other essay types. However, picking a suitable theme for a definition essay is equally tricky yet important. Pick an interesting subject to ensure maximum readership.

If you are facing writerâs block, here is a list of some great definition essay topics for your help. Choose from the list below and draft a compelling essay.

- Authenticity

- Sustainability

- Mindfulness

Here are some more extended definition essay topics:

- Social media addiction

- Ethical implications of gene editing

- Personalized learning in the digital age

- Ecosystem services

- Cultural assimilation versus cultural preservation

- Sustainable fashion

- Gender equality in the workplace

- Financial literacy and its impact on personal finance

- Ethical considerations in artificial intelligence

- Welfare state and social safety nets

Need more topics? Check out this definition essay topics blog!

Definition Essay Writing Tips

Knowing the correct writing procedure is not enough if you are not aware of the essayâs small technicalities. To help students write a definition essay effortlessly, expert writers of CollegeEssay.org have gathered some simple tips.

These easy tips will make your assignment writing phase easy.

- Choose an exciting yet informative topic for your essay.

- When selecting the word, concept, or term for your essay, make sure you have the knowledge.

- When consulting a dictionary for the definition, provide proper referencing as there are many choices available.

- To make the essay informative and credible, always provide the origin and history of the term.

- Highlight different meanings and interpretations of the term.

- Discuss the transitions and evolution in the meaning of the term in any.

- Provide your perspective and point of view on the chosen term.

Following these tips will guarantee you better grades in your academics.

By following the step-by-step approach explained in this guide, you will acquire the skills to craft an outstanding essay.

Struggling with the thought, " write my college essay for m e"? Look no further.

Our dedicated definition essay writing service is here to craft the perfect essay that meets your academic needs.

For an extra edge, explore our AI essay writer , a tool designed to refine your essays to perfection.

Barbara P (Literature, Marketing)

Barbara is a highly educated and qualified author with a Ph.D. in public health from an Ivy League university. She has spent a significant amount of time working in the medical field, conducting a thorough study on a variety of health issues. Her work has been published in several major publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

Home ➔ Essay Structure ➔ Body Paragraphs ➔ Evidence in Essays

Guide to Evidence in an Essay

In essays, evidence can be presented in a number of ways. It might be data from a relevant study, quotes from a literary work or historical event, or even an anecdote that helps to illustrate your point. No matter what form it takes, evidence supports your thesis statement and major arguments.

Why is using evidence important? In academic writing, it is important to make a clear and well-supported argument. In order to do this, you need to use evidence to back up your claims. Provide evidence to show that you have done your research and that your arguments are based on facts, not just opinions.

What is evidence in academic writing?

In academic writing, evidence is often presented in the form of data from research studies or quotes from literary works. It can be used to support your argument or to illustrate a point you are making. Good evidence must be relevant, persuasive, and trustworthy.

Types of evidence

There are many different types of evidence that can be used in essays. Some common examples include:

Analogical: An analogy or comparison that supports your argument.

Example: “Like the human body, a car needs regular maintenance to function properly.”

This type is considered to be one of the weakest, as it is often based on opinion rather than fact. To use it well, you need to be sure that the analogy is relevant and that there are enough similarities between the two things you are comparing.

Anecdotal: A personal experience or story, your own research, or example that illustrates your point.

Example: “I know a woman who was fired from her job after she became pregnant.”

Anecdotal evidence is used to support a point or argument, but it should be used sparingly, as it is often considered to be less reliable than other types of evidence. It can also be used as a hook to engage the reader’s attention.

Hypothetical : A hypothetical situation or thought experiment that supports your argument.

Example: “If we do not take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the Earth’s average temperature will continue to rise.”

This type of evidence can be useful in persuading readers to see your point of view. It is important to make sure that the hypothetical situation is realistic, as otherwise, it will undermine your argument. It is also not a strong form of evidence, and to make it work well, you will need to make the reader feel invested in the outcome.

Logical: A reasoning or argument that uses logic to support your claim.

Example: “The death penalty is a deterrent to crime because it removes the possibility of rehabilitation.”

This type is based on the idea that if something is true, then it must be the case that something else is also true. It is not the strongest type of evidence, as there are often other factors that can impact the validity of the argument.

Statistical: Data from research studies or surveys that support your argument.

Example: “According to a study by the American Medical Association, gun violence is the third leading cause of death in the United States.”

This type of evidence is often considered to be the most persuasive, as it is based on factual data. However, it is important to make sure that the data is from a reliable source and that it is interpreted correctly.

Testimonial: A quote from an expert or someone with first-hand experience that supports your argument.

Example: According to Dr. John Smith, a leading expert on the health effects of smoking, “Smoking is a major contributor to heart disease and lung cancer.”

This type of evidence can be very persuasive, as it uses the authority of an expert to support your argument. However, it is important to make sure that the expert is credible and that their opinion is relevant to your argument.

Textual: A quote from a literary work or historical document that supports your argument.

Example: “In the book ‘ To Kill a Mockingbird ,’ Atticus Finch says, ‘You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view.'”

This type of evidence can be used to support your argument, but it is important to make sure that the quote is relevant and that it is interpreted correctly.

Visual: A graph, chart, or image that supports your argument.

This evidence type might not be the most common in essays, but it can be very effective in persuading the reader to see your point of view. It is important to make sure that the visual is clear and easy to understand, as otherwise, it will not be as effective.

Types of evidence sources

When you want to find evidence to support your argument, it is important to consider the source. There are two major types of sources:

- Primary sources: These are first-hand accounts or data that has been collected by the author. Examples of such sources include research studies, surveys, and interviews.

- Secondary sources: These are second-hand accounts or data that has been collected by someone other than the author. Examples of such sources include books, articles, and websites.

For example, if you are writing an essay about George Orwell’s “1984,” a primary source would be the novel itself, while a secondary source would be an article about the author’s life.

As for which one is better or worse, it all depends on the context. In general, primary sources are more reliable, but they can be difficult to find or interpret. Secondary sources are easier to find, but they might not be as accurate.

But in general, these two types complement each other. In other words, you will likely need to use both primary and secondary sources to support your argument.

Incorporating evidence

There are different ways to introduce evidence effectively in your essay. The most common methods are:

- Direct Quotation: A direct quotation is when you reproduce the exact words of a source. This can be done by using quotation marks and citing the source in your paper .

- Paraphrasing: Paraphrasing is when you explain something in your own words. It’s a way of conveying the main idea of a text without simply repeating what the author has already said. When you paraphrase, you can use your own voice and style to communicate someone else’s words in a way that better suits your audience.

- Summarizing: Summarizing is when you provide a brief overview of a text. This can be done by identifying the main points and ideas in the text and conveying them in your own words.

- Factual data: Factual data is information that can be verified through research. This could include statistics, numbers, or other types of data that support your main argument.

How to use evidence in essays

Besides knowing what type of evidence to use, it is also important to know how to use it in the most effective way. Here are some steps that you can take to incorporate evidence in your paper.

1. Present your argument first

Before you start introducing evidence into your essay, it is important to first make a claim or thesis statement . This will give your paper direction and let your reader know what to expect.

On a paragraph level, your topic sentences are the arguments you are making. The rest of the paragraph should be used to support this claim with evidence.

Let’s say the topic of the essay is “The Impact of Social Media on Young People.”

Then, your thesis statement could be something like, “Social media has had a negative impact on the mental health of young people.”

And your first body paragraph might start with the following topic sentence: “The first way social media has had a negative impact on young people is by causing them to compare themselves to others.”

2. Introduce your evidence

Once you have presented your argument, you will need to introduce your evidence. This can be done by using a signal phrase or lead-in .

A signal phrase is a phrase that introduces the evidence you are about to provide. It can be used to introduce a direct quotation or paraphrase. For example:

- According to Dr. Smith,…

- Dr. Smith argues that…

- As Dr. Smith points out,…

- There is evidence to suggest that..

- The survey reveals that…

- As suggested by the study,…

Word Choice in Essays – read more about various words that you can use in your essay in different cases.

3. Present evidence

After you have introduced your evidence, you will need to state it clearly. This can be done by using a direct quotation, paraphrasing, or summarizing.

When using a direct quotation , you will need to use quotation marks and cite the source in your paper. For example:

As Dr. Smith points out, “Teenagers spend a lot of time on social media platforms observing the lives of others and comparing themselves to what they see, which can lead to damaged self-esteem and depression.”

When paraphrasing or summarizing , you will need to make sure that you are conveying the main points of the source using different words. For example:

Dr. Smith argues that social media can have a negative impact on young people’s mental health because it makes them compare themselves to others.

4. Comment on your evidence

After you have stated your supporting evidence, you will need to explain how it supports your argument. This can be done by providing your own analysis or interpretation.

For example:

By constantly comparing themselves to others, young people are more likely to develop a negative view of themselves. This can lead to mental health problems such as depression and low self-esteem.

5. Repeat for additional evidence

If you have more than one piece of evidence that supports your own argument, you will need to repeat steps 2-4 for each additional piece.

6. Link back to your key points

Once you have finished discussing your evidence, it is important to link back to your initial argument in the last sentence of your body paragraph and transition to the next paragraph .

Example of a full body paragraph with all the steps applied:

One way social media has had a negative impact on young people is by causing them to compare themselves to others. According to Dr. Smith, “Teenagers spend a lot of time on social media platforms observing the lives of others and comparing themselves to what they see, which can lead to depression and damaged self-esteem” (qtd. in Jones). By constantly comparing themselves to others, young people are more likely to develop a negative view of themselves. This can lead to mental health problems such as depression and low self-esteem. But this is not the only way social media can negatively affect young people’s mental health.

7. Wrap it up in a conclusion

Once you have finished all your body paragraphs, you will need to write a conclusion . This is where you will wrap up your argument and emphasize the main points that you have proven.

Remember, using evidence is just one part of the essay-writing process . You also need to make sure that your paper is well organized, has a clear structure , and is free of grammar and spelling errors. But if you can master the use of evidence, you will be well on your way to writing a strong essay.

Was this article helpful?

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

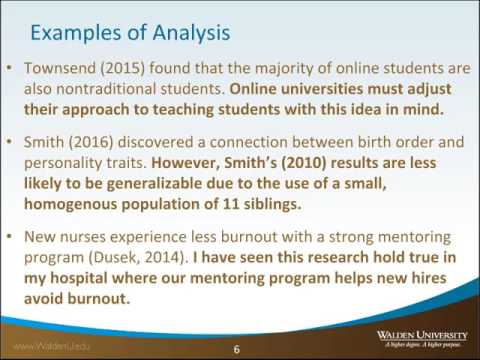

Using Evidence: Analysis

Beyond introducing and integrating your paraphrases and quotations, you also need to analyze the evidence in your paragraphs. Analysis is your opportunity to contextualize and explain the evidence for your reader. Your analysis might tell the reader why the evidence is important, what it means, or how it connects to other ideas in your writing.

Note that analysis often leads to synthesis , an extension and more complicated form of analysis. See our synthesis page for more information.

Example 1 of Analysis

Without analysis.

Embryonic stem cell research uses the stem cells from an embryo, causing much ethical debate in the scientific and political communities (Robinson, 2011). "Politicians don't know science" (James, 2010, p. 24). Academic discussion of both should continue (Robinson, 2011).

With Analysis (Added in Bold)

Embryonic stem cell research uses the stem cells from an embryo, causing much ethical debate in the scientific and political communities (Robinson, 2011). However, many politicians use the issue to stir up unnecessary emotion on both sides of the issues. James (2010) explained that "politicians don't know science," (p. 24) so scientists should not be listening to politics. Instead, Robinson (2011) suggested that academic discussion of both embryonic and adult stem cell research should continue in order for scientists to best utilize their resources while being mindful of ethical challenges.

Note that in the first example, the reader cannot know how the quotation fits into the paragraph. Also, note that the word both was unclear. In the revision, however, that the writer clearly (a) explained the quotations as well as the source material, (b) introduced the information sufficiently, and (c) integrated the ideas into the paragraph.

Example 2 of Analysis

Trow (1939) measured the effects of emotional responses on learning and found that student memorization dropped greatly with the introduction of a clock. Errors increased even more when intellectual inferiority regarding grades became a factor (Trow, 1939). The group that was allowed to learn free of restrictions from grades and time limits performed better on all tasks (Trow, 1939).

In this example, the author has successfully paraphrased the key findings from a study. However, there is no conclusion being drawn about those findings. Readers have a difficult time processing the evidence without some sort of ending explanation, an answer to the question so what? So what about this study? Why does it even matter?

Trow (1939) measured the effects of emotional responses on learning and found that student memorization dropped greatly with the introduction of a clock. Errors increased even more when intellectual inferiority regarding grades became a factor (Trow, 1939). The group that was allowed to learn free of restrictions from grades and time limits performed better on all tasks (Trow, 1939). Therefore, negative learning environments and students' emotional reactions can indeed hinder achievement.

Here the meaning becomes clear. The study’s findings support the claim the reader is making: that school environment affects achievement.

Analysis Video Playlist

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Quotation

- Next Page: Synthesis

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

Gen ed writes, writing across the disciplines at harvard college.

- Evidence and Analysis

Why It Matters

An assignment prompt’s guidance on evidence and analysis sets parameters for the content and form of a writing assignment: What kinds of sources should you be working with? Where should you find those sources? How should you be working with them?

More on "Evidence and Analysis"

The evidence and analysis you're asked to use (or not use) for a writing assignment often reflect the genre and size of the assignment at hand. With any writing assignment prompt, it’s important to step back and make sure you’re clear about the scope of evidence and analysis you’ll be working with. For example:

In terms of evidence,

- what kinds of evidence should be used (peer-reviewed articles versus op-ed pieces),

- which evidence in particular and how much (3–5 readings from class versus independent research), and

- why (because op-ed pieces capture a kind of public discourse better than peer-reviewed articles, or because 3–5 readings from class is manageable for a 4-page essay and also reinforces the readings assigned for the course, etc.).

In terms of analysis,

- is the assignment asking you to make an argument? If so, what kind of argument? (e.g., a rhetorical analysis weighing the pros and cons of a think piece, or a policy memo making normative claims about recommended courses of action, or a test a theory essay assessing the applicability of a framework to real-world cases?)

- if not, what is it asking you to do with evidence? (e.g., summarize a source’s argument, or draft a research question based on an annotated bibliography or data set)

- why? (because it’s important to establish other thinkers’ positions accurately before taking your own position, or because asking questions before moving on to a thesis or conclusion will make the research process more compelling).

What It Looks Like

- Science & Technology in Society

- Ethics & Civics

- Histories, Societies, Individuals

- Aesthetics & Culture

STEP 1: PROPOSAL WITH ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Length: 250–500 words, not including annotated bibliography. The annotated bibliography must have at least 5 different references from outside the course and 5 different references from the syllabus.

Source requirements:

- Minimum 5 different references from outside the course (at least 3 must be peer-reviewed scholarly sources) [1]

- Minimum 5 different references from Gen Ed 1093 reading assignments listed on the syllabus; lectures do not count toward the reference requirement, and Reimagining Global Health will only count as one reference [2]

- Citation format either AAA or APA [3] , consistent throughout the paper

- Careful attention to academic integrity and appropriate citation practices

- The annotated bibliography does not count toward your word count, but in-text citations do. [4]

__________ [1] Explicit guidance about what kinds of sources and how many sources to include [2] Clarification about what does / doesn't count toward the required number of sources [3] Clear guidance about citation format [4] Clarification about what does / doesn't count toward the required word count

Adapted from Gen Ed 1093 : Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Cares? Reimagining Global Health | Fall 2020

On p 13 of Why not Socialism?, G. A. Cohen states that the principle of “socialist equality of opportunity” is a principle of justice. What is the principle of “socialist equality of opportunity,” why does Cohen think it is a principle of justice, why does he think it is a desirable principle, and why does he think it is feasible? Which part of his argument do you think is most vulnerable to objections? Formulate some objections and explore how Cohen could respond. Do you think the objections succeed, or is Cohen’s view correct?

Proceed as follows: [1] State what socialist equality of opportunity is, by way of contrast with the two other kinds of equality of opportunity identified by Cohen. Explain why Cohen thinks, as a matter of justice, socialist equality of opportunity is preferable to the other two, and explain why an additional principle of community is needed to supplement that principle of justice. Then assess whether Cohen offers additional reasons (beyond the superiority of his principle over the alternatives) as to why equality and community are desirable, both for the camping trip and society at large. In a next step briefly summarize what he says about the feasibility of the principle. Devote about two thirds of your discussion to the tasks sketched so far, and then devote the remaining third to your exploration of the objections to parts of Cohen’s argument and an exploration of their success.

General Guidance

In section, your TF will discuss general guidelines to writing a philosophy paper. [2] Please also consult the “Advice on Written Assignments” posted on Canvas before writing the paper. Recall that you will write three papers in this course. The assignments get progressively more demanding. In the first paper, the emphasis is on reconstructing arguments, allowing you to develop the skill of logical reconstruction rather than narrative summary of a text. …The second paper goes beyond reconstruction, putting more emphasis on the critically evaluating arguments. The third paper gives you an opportunity to develop a well-reasoned defense in support of your own view regarding one of the central issues of the class. [3]

__________ [1] Students are given clear advice about how to use evidence differently at different points in their assignment. [2] Students are assured that they will learn guidelines for working with evidence and analysis in a more disciplinary kind of writing (with which many of them will likely be unfamiliar). [3] The move from “reconstruction” to “critically evaluating” to “well-reasoned defense” signals a scaffolded development of ways to work with evidence, along with reasons why students are being are being asked to work with evidence in a certain way for this first essay, viz., “ to develop the skill of logical reconstruction."

Adapted from Gen Ed 1121 : Economic Justice | Spring 2020 Professor Mathias Risse

Research Requirements

All projects, regardless of which modality you adopt, will need to include [1]

- an annotated bibliography that includes at least 5 scholarly sources. These sources can include scholarly articles, books, or websites. For a website, please check with the TFs to confirm the viability of it as a source. [2] There are legitimately scholarly websites, but many content-related sites are not scholarly.

- a 1-page artist statement.

See “How tos_Annotated Bibliography_your Artist Statement” for specific instructions for both the annotated bibliography and the artist statement. [3]

__________ [1] Explicit guidance about what kinds of sources and how many to include [2] Advice on how to get help evaluating whether a source counts as viable evidence [3] Additional resources (tied to guidelines and process) that help explain the roles of evidence and analysis in the assignment

Adapted from Gen Ed 1099 : Pyramid Schemes: What Can Ancient Egyptian Civilization Teach Us? Professor Peter der Manuelian

Introduce yourself to another student in the class by making a virtual mixtape for them. ⋮ Your tape should contain the following (in any order): [1]

- The greeting on the Golden Record that best describes you (or record your own)

- One piece of music included on the Golden Record

- Your personal summer hit of 2020

- A “found sound” (recorded in your environment that seems characteristic or interesting)

- A piece of music that best describes you

- Your favorite piece/song by a musician outside the US/Canada

Use these guidelines as a starting point for your mixtape. Feel free to get creative. The mixtape should say something important about YOU. (There will be no written text accompanying your file. The sounds have to say it all.) [2]

__________ [1] Students are given a clear checklist of what to include in their assignment. [2] In this assignment, the evidence makes its argument through curation, rather than additional written analysis. Making sure students understand that particular relationship of evidence to analysis ahead of time frames the assignment’s purpose and genre.

Adapted from Gen Ed 1006 : Music from Earth | Fall 2020 Professor Alex Rehding

- DIY Guides for Analytical Writing Assignments

- Types of Assignments

- Style and Conventions

- Specific Guidelines

- Advice on Process

- Receiving Feedback

Assignment Decoder

- Departments and Units