The Legacy of Conquest

The unbroken past of the american west (book review).

by Jenni Ostwinkle Silva

Patricia Nelson Limerick isn’t setting out to discredit Frederick Jackson Turner as an historian and scholar. And it isn’t that she believes his influential “ Frontier Thesis ” was without merit. On the contrary, she describes Turner as a “scholar with intellectual courage, an innovative spirit, and a forceful writing style” whose thesis served a purpose in the late 19 th /early 20 th centuries. 1 In Limerick’s opinion, the problem lies in the “excessive deference” for Turner that led many historians to believe that Turner’s thesis was the first, final, and only word in Western history. Although his conception of the frontier seemed unifying and efficient, its dominance wedded Western historians to an idea that was static, rigid, and exclusionary. The Frontier Thesis may have “created” Western history but it also set up arbitrary divisions between “the West” and “the rest” – divisions Limerick was determined to break down in The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West.

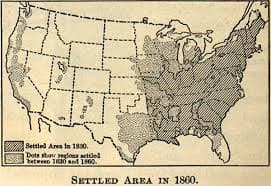

Much of Limerick’s work hinges on the debate of “process” (how events unfolded) versus “place” (the importance of location). In Turner’s view, the process of settling the frontier served as the basis of American exceptionalism, the belief that the United States are unique among world nations. Limerick and other “New Western” historians have challenged this theory by declaring that the West was always a place, with many different actors and events, not an empty land anxiously awaiting the arrival of white settlers. Turner’s thesis drew a line in time, carving out the arrival of white settlers as the beginning of the West and the closing of the frontier in 1890 (based on his interpretation of census records) as the end of this era. Limerick attempts to restore continuity to both time and space, and in doing so, opens up the field of Western history.

To accomplish this, Limerick addressed the history of the West thematically and divides her book into two tellingly-titled sections: “The Conquerors” and “The Conquerors Meet Their Match.” Turner believed that the frontier, shifting from savagery to civilization, served to “Americanize” the nation. Working under that pretext, scholars and citizens have conceptualized the frontier as a positive process. Using “place” instead of “process,” Limerick characterizes this period of Western history as “conquest.” By viewing the West as a place, she repositions the role of white settlers. These enterprising individuals did not discover a new place – they attempted to conquer a land that was already inhabited by Indians. Although this concept may seem jarring to the uninitiated, Limerick points out the contradiction of believing that “the legacy of slavery was serious business, while the legacy of conquest was not.” 2 The older framework only made sense was through the thick veil of denial. This denial, in turn, allowed for the proliferation of a number of myths in Western history, such as the idea of rugged individualism. Under this model, Westerners were fully removed from the rest of the country. When other actors appeared, they were viewed as imposing upon the Western (white) settlers. And if the settlers themselves happened to be imposing upon the Plains Indians, it was only because the forward march of history demanded it – and because the settlers had convinced themselves that Indians were a doomed race.

Unfortunately for this last myth, she states, the conquered refused to be or remain conquered, nor were they passive participants in the drama of the West. Attacking the notion that the history of the West is the history of the white man, Limerick turns her attention to Plains Indians, Hispanic, Chinese, Japanese, and blacks. Although she addresses these groups of people in a fairly general manner, she makes a strong case for the study of borderlands history. Viewed from a 21 st -century perspective, it can be easy to forget that the giant coast-to-coast landmass of the United States was never preordained. Battles were fought, treaties were drawn, and revenge was sought before state lines could be carved into the map of America. Introducing other ethnic and racial groups broadens the scope of Western history and highlights the centrality of conquest in the creation of the West. As Limerick makes clear, the history of the West is a nuanced and multi-faceted tale. While an historian annoyed “by the ethnocentricity of earlier frontier history” may be tempted by the desire to “take the Indian side,” doing so will not erase ethnocentricity. 3 The Indian (or Hispanic, or Chinese, or Japanese, or black) “side” is a difficult thing to locate. Instead, she recommends that historians view these groups – she is speaking of Indians in particular, but the same motivation carries throughout her other discussions – as “people steering their way through a difficult terrain of narrowing choices.” 4 The history books may not have treated these groups kindly (if they addressed them at all) but that does not mean they did not act, react, and affect the environment and the people around them.

In her final chapter, Limerick attempts to wrestle with the enduring power of the mythologized West and the problems that remain. The “frontier” still commands great respect and politicians from John Kennedy to Ronald Reagan have invoked its notion of progress. 5 Mexicans became “aliens” in their homeland when the United States conquered the Southwest and today, immigration remains a hot-button issue. Indians, still decidedly not-extinct , continue to maneuver through legal and political channels in an attempt to recoup their losses. But a restoration of rights does not, as Limerick points out, solve the larger problem of scarce resources. Although white settlers and the U.S. government were determined to “manage nature,” drought and limited access to water remain critical concerns.

Ironically, Limerick, considered one of the greatest scholars in the field of New Western history, is actually opposed to viewing Western history as an area of specialized study; her intention is to create connections. Reaching across the fields of economics, geography, anthropology and dipping into the current events, Limerick is trying to erase the lines Turner drew around the West. If the old ways of understanding Western history no longer work, new ways must be introduced. Here, environmental history and borderlands history take center stage.

A number of historians have followed in a similar vein. William Cronon and Elliot West address many of the same issues as Limerick – and then push them further. West affords Plains Indians an even more prominent position on the Western stage, portraying them as active participants in a history that is sometimes of their own making and sometimes out of their control. In examining the importance of 19 th -century Chicago, Cronon points out the problems with ideas of Western independence. In both of these works, as with Limerick, environmental history looms large. These Contested Plains and Nature’s Metropolis simply could not have been written in the framework provided by Turner even if they largely discredit its theories.

There are several minor missteps in The Legacy of Conquest , many of which Limerick admits to in the preface to the 2006 reprint. For one, she does not investigate the role of fur traders in the West, which would have given her an avenue to explore more fluid conceptions of identity. She also does not take into account the role of cities, reverting, against her best intentions, to the tired “idea that the real West meant the rural West!” 6 Although Limerick employed contemporary examples to illustrate her argument about continuity (and these topics are now 20-plus years old), the book has aged well – perhaps as more evidence of continuity of the West. Many of the issues she discussed remain unresolved: issues about resource conservation, immigration, and the management of nature seem as relevant today as they did in the 1980s – or even the 1880s.

Below, Patricia Limerick delivers her lecture, “The Winning of the West Revisited,” at the 2011 Theodore Roosevelt Symposium in Medora, North Dakota on October 29, 2011. Q&A session follows the lecture.

If anything, Limerick seems to run the risk of overselling her case. In her fifth chapter, “The Meeting Ground of the Past and Present,” Limerick thoroughly grounds her discussion in the political and environmental problems of 1970s and 1980s. It is a somewhat distracting diversion from the technique that Limerick employs in her other chapters. Her argument about continuity is most effective when woven within the larger narrative, not considered separately. Instead of drawing connections, it can seem as though Limerick is only pushing her agenda – perhaps the danger of any historian venturing into the present. Additionally, perhaps because many of the themes she addresses have been long-adopted by the historical profession, the reader is often willing to accept her ideas before Limerick has concluded her argument.

These issues are minor. The Legacy of Conquest stands out as a cogent, well-written, and gloriously accessible examination of the major themes in Western history. While experts are unlikely to be surprised, Legacy of Conquest serves as an excellent starting point for Western historians and, she hopes, American historians in general (after all, as Limerick might ask, what’s the difference?) Limerick cheerfully admits that her book is a work of synthesis. Many of the stories and characters she highlights are purposefully familiar to illustrate their previous historical immobility. Cast in the new light of environmental history or borderlands history, what is old becomes new again. Limerick is arguing (beseeching, pleading) for a new focus on inclusivity and continuity in Western scholarship. It is a point well made, and, judging by the durability of Legacy of Conquest and endurance of the New Western history, a point still well-taken.

For more information: Visit the U.S. History Scene reading lists for Environmental History , History of the American West , and Native American History

Was Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis Myth or Reality?

Two scholars debate this question.

Written by: (Claim A) Andrew Fisher, William & Mary; (Claim B) Bradley J. Birzer, Hillsdale College

Suggested sequencing.

- Use this Point-Counterpoint with the Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” 1893 Primary Source to give students more background on individualism and western expansion.

Issue on the Table

Was Turner’s thesis a myth about the individualism of the American character and the influence of the West or was it essentially correct in explaining how the West and the advancing frontier contributed to the shaping of individualism in the American character?

Instructions

Read the two arguments in response to the question, paying close attention to the supporting evidence and reasoning used for each. Then, complete the comparison questions that follow. Note that the arguments in this essay are not the personal views of the scholars but are illustrative of larger historical debates.

Every nation has a creation myth, a simple yet satisfying story that inspires pride in its people. The United States is no exception, but our creation myth is all about exceptionalism. In his famous essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” Frederick Jackson Turner claimed that the process of westward expansion had transformed our European ancestors into a new breed of people endowed with distinctively American values and virtues. In particular, the frontier experience had supposedly fostered democracy and individualism, underpinned by the abundance of “free land” out West. “So long as free land exists,” Turner wrote, “the opportunity for a competency exists, and economic power secures political power.” It was a compelling articulation of the old Jeffersonian Dream. Like Jefferson’s vision, however, Turner’s thesis excluded much of the nation’s population and ignored certain historical realities concerning American society.

Very much a man of his times, Turner filtered his interpretation of history through the lens of racial nationalism. The people who counted in his thesis, literally and figuratively, were those with European ancestry—and especially those of Anglo-Saxon origins. His definition of the frontier, following that of the U.S. Census, was wherever population density fell below two people per square mile. That effectively meant “where white people were scarce,” in the words of historian Richard White; or, as Patricia Limerick puts it, “where white people got scared because they were scarce.” American Indians only mattered to Turner as symbols of the “savagery” that white pioneers had to beat back along the advancing frontier line. Most of the “free land” they acquired in the process came from the continent’s vast indigenous estate, which, by 1890, had been reduced to scattered reservations rapidly being eroded by the Dawes Act. Likewise, Mexican Americans in the Southwest saw their land base and economic status whittled away after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that nominally made them citizens of the United States. Chinese immigrants, defined as perpetual aliens under federal law, could not obtain free land through the Homestead Act. For all these groups, Euro-American expansion and opportunity meant the contraction or denial of their own ability to achieve individual advancement and communal stability.

Turner also exaggerated the degree of social mobility open to white contemporaries, not to mention their level of commitment to an ideology of rugged individualism. Although plenty of Euro-Americans used the homestead laws to get their piece of free land, they often struggled to make that land pay and to keep it in the family. During the late nineteenth century, the commoditization and industrialization of American agriculture caught southern and western farmers in a crushing cost-price squeeze that left many wrecked by debt. To combat this situation, they turned to cooperative associations such as the Grange and the National Farmers’ Alliance, which blossomed into the Populist Party at the very moment Turner was writing about the frontier as the engine of American democracy. Perhaps it was, but not in the sense he understood. Populists railed against the excess of individualism that bred corruption and inequality in Gilded Age America. Even cowboys, a pillar of the frontier myth, occasionally tried to organize unions to improve their wages and working conditions. Those seeking a small stake of their own—what Turner called a “competency”— in the form of their own land or herds sometimes ran afoul of concentrated capital, as during the Johnson County War of 1892. The big cattlemen of the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association had no intention of sharing the range with pesky sodbusters and former cowboys they accused of rustling. Their brand of individualism had no place for small producers who might become competitors.

Turner took such troubles as a sign that his prediction had come true. With the closing of the frontier, he said, the United States would begin to see greater class conflict in the form of strikes and radical politics. There was lots of free land left in 1890, though; in fact, approximately 1 million people filed homestead claims between 1901 and 1913, compared with 1.4 million between 1862 and 1900. That did not prevent the country from experiencing serious clashes between organized labor and the corporations that had come to dominate many industries. Out west, socialistic unions such as the Western Federation of Miners and the Industrial Workers of the World challenged not only the control that companies had over their employees but also their influence in the press and politics. For them, Turner’s dictum that “economic power secures political power” would have held a more sinister meaning. It was the rise of the modern corporation, not the supposed fading of the frontier, that narrowed the meanings of individualism and opportunity as Americans had previously understood them.

Young historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his academic paper, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago on July 12, 1893. He was the final presenter of that hot and humid day, but his essay ranks among the most influential arguments ever made regarding American history.

Turner was trained at the University of Wisconsin (his home state) and Johns Hopkins University, then the center of Germanic-type graduate studies—that is, it was scientific and objectivist rather than idealist or liberal. Turner rebelled against that purely scientific approach, but not by much. In 1890, the U.S. Census revealed that the frontier (defined as fewer than two people per square mile) was closed. There was no longer an unbroken frontier line in the United States, although frontier conditions lasted in certain parts of the American West until 1920. Turner lamented this, believing the most important phase of American history was over.

No one publicly commented on the essay at the time, but the American Historical Association reprinted it in its annual report the following year, and within a decade, it became known as the “Turner Thesis.”

What is most prominent in the Turner Thesis is the proposition that the United States is unique in its heritage; it is not a European clone, but a vital mixture of European and American Indian. Or, as he put it, the American character emerged through an intermixing of “savagery and civilization.” Turner attributed the American character to the expansion to the West, where, he said, American settlers set up farms to tame the frontier. “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” As people moved west in a “perennial rebirth,” they extended the American frontier, the boundary “between savagery and civilization.”

The frontier shaped the American character because the settlers who went there had to conquer a land difficult for farming and devoid of any of the comforts of life in urban parts of the East: “The frontier is the line of most rapid and effective Americanization. The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin. It puts him in the log cabin of the Cherokee and Iroquois and runs an Indian palisade around him. Before long he has gone to planting Indian corn and plowing with a sharp stick; he shouts the war cry and takes the scalp in orthodox Indian fashion. In short, at the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes, or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails.”

Politically and socially, according to Turner, the American character—including traits that prioritized equality, individualism, and democracy—was shaped by moving west and settling the frontier. “The tendency,” Turner wrote, “is anti-social. [The frontier] produces antipathy to control, and particularly to any direct control.” Those hardy pioneers on the frontier spread the ideas and practice of democracy as well as modern civilization. By conquering the wilderness, Turner stressed, they learned that resources and opportunity were seemingly boundless, meant to bring the ruggedness out of each individual. The farther west the process took them, the less European the Americans as a whole became. Turner saw the frontier as the progenitor of the American practical and innovative character: “That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and acquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom – these are trains of the frontier.”

Turner’s thesis, to be sure, viewed American Indians as uncivilized. In his vision, they cannot compete with European technology, and they fall by the wayside, serving as little more than a catalyst for the expansion of white Americans. This near-absence of Indians from Turner’s argument gave rise to a number of critiques of his thesis, most prominently from the New Western Historians beginning in the 1980s. These more recent historians sought to correct Turner’s “triumphal” myth of the American West by examining it as a region rather than as a process. For Turner, the American West is a progressive process, not a static place. There were many Wests, as the process of conquering the land, changing the European into the American, happened over and over again. What would happen to the American character, Turner wondered, now that its ability to expand and conquer was over?

Historical Reasoning Questions

Use Handout A: Point-Counterpoint Graphic Organizer to answer historical reasoning questions about this point-counterpoint.

Primary Sources (Claim A)

Cooper, James Fenimore. Last of the Mohicans (A Leatherstocking Tale) . New York: Penguin, 1986.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” http://sunnycv.com/steve/text/civ/turner.html

Primary Sources (Claim B)

Suggested resources (claim a).

Cronon, William, George Miles, and Jay Gitlin, eds. Under an Open Sky: Rethinking America’s Western Past . New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1992.

Faragher, John Mack. Women and Men on the Overland Trail . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

Grossman, Richard R, ed. The Frontier in American Culture: Essays by Richard White and Patricia Nelson Limerick . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

Limerick, Patricia Nelson. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West . New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1987.

Limerick, Patricia Nelson, Clyde A. Milner II, and Charles E. Rankin, eds. Trails: Toward a New Western History . Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1991.

Milner II, Clyde A. A New Significance: Re-envisioning the History of the American West . New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Nugent, Walter. Into the West: The Story of Its People . New York: Knopf, 1991.

Slotkin, Richard. The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization, 1800-1890 . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

Suggested Resources (Claim B)

Billington, Ray Allen, and Martin Ridge. Westward Expansion: A History of the American Frontier . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2001.

Etulain, Richard, ed. Does the Frontier Experience Make America Exceptional? New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 1999.

Mondi. Megan. “’Connected and Unified?’: A More Critical Look at Frederick Jackson Turner’s America.” Constructing the Past , 7 no. 1:Article 7. http://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol7/iss1/7

Nelson, Robert. “Public Lands and the Frontier Thesis.” Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States , Digital Scholarship Lab, University of Richmond, 2014. http://dsl.richmond.edu/fartherafield/public-lands-and-the-frontier-thesis/

More from this Category

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

Jessica M. DeWitt: Editing and Consulting

Comps Notes: The “Frontier” in the West

I decided to publish my write-ups from my comprehensive exam reading fields. I am publishing them *as is.* Thus they represent my thoughts as a new PhD student. They were written between September 2011 and July 2012. The full collection is accessible here .

The “Frontier” in the West

Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” in The Frontier in American History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1921).

Sandra L. Myres, Westering : Women and the Frontier Experience, 1800-1915 (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1982).

Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987).

Geoff Cunfer, On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005).

Turner was heavily influenced by the evolutionary discourse of his era. The governing theme in the Frontier Thesis is that of social evolution. Turner subscribes to a set understanding of civilization development that follows a systematic evolutionary sequence. Civilization starts in the savage state and then progresses to pastoralism and, finally, cities and industry. Europeans had been ensnared in the smothering constraints of the final stage for far too long, which had led to venality and decay both in Europe and in the eastern United States, where European institutions were still in practice. The availability of free, undeveloped land in the West had facilitated Americans to go through a rebirthing process. Rugged individualism, personified in the character of the mountain man, reigned supreme on the frontier. Men were able to start anew, almost at the savage stage, but what separated these men from the Native Americans was that they brought with them the prime characteristics of European social and political governance. Those European characteristics and institutions that were despoiled were swiftly thrown out for they had no place on the even playing field of the West, which enabled wholesome, untainted democracy to flourish.

Wilderness plays a role in Turner’s thesis only as a means to the furthering of man’s advancement. Wilderness only has value as a commodity to be conquered and ultimately civilized. It is the challenges that wilderness throws the frontiersman’s way that allow the frontiersman to shed the over-embellished skin of European civilization, and to step forward a new, improved, self-reliant individual ready to turn the western wilderness into the hub of democratic principles. Regardless of wilderness’ main position in this rebirthing process, man’s duty, according to Turner, is still to tame and develop wilderness into oblivion. Until 1890, there was always more wilderness available beyond the next ridge into which future generations could move in order to restart the rebirthing process and to guarantee that the United States would not begin to ferment in the poison of decayed, archaic civilization. The supposed “end” of the frontier threatened the core of American exceptionalism, and led to leaders, such as Theodore Roosevelt, to turn outward for a sense of frontier, fueling an American campaign of imperialism.

The core problem with Turner’s thesis and the greatest disservice that he rendered on future historians, according to Limerick, is that his entire argument was based on the idea that the frontier had ended. This kind of clean break in time does not take into account the continuities of human experience. Limerick’s argument is based on a strong belief that the problems that the west endured are still prevalent and have had a major effect on the west of today. She suggests that the entire concept of the “frontier” should be pushed aside or at least to the very back of the western historian’s consciousness. “Frontier,” is a process, not a place, she argues. When one deemphasizes the concept of the frontier, the supposed end of the West no longer makes sense. “Reorganized,” she writes, “the history of the West is a study of a place undergoing conquest and never fully escaping its consequences.” (26) Liberated from the confines of the frontier and its demise, the historian is able to capture the true essence of the West as a place.

The end of the frontier is not the only part of Turner’s thesis that Limerick has a problem with, however. Firstly, Limerick tears apart Turner’s assertion that the western settlers were rugged, individualistic, and independent. Limerick asserts that those that moved west viewed their motives as innocent and commonplace. Thus, they could not comprehend why their efforts were continuously hindered, they did not view this as a miscalculation of the limits of reality on their part, but rather as an inexplicable and undeserved fate that was forced on them. One example of this kind of attitude that Limerick describes is when the farmers moved into the Great Plains, a naturally arid region, and then were surprised when adequate rainfall did not follow them. This kind of hardship caused westerners to view themselves as the “innocent victim,” a far cry from the hardened, independent individuals of Turner’s frontier. From the very beginning, the West was dependent upon the East for basics such as canned food. As their hardships worsened, the westerners placed blame on the wilderness, the Indians, and finally, the ultimate scapegoat, the federal government. And yet, the west readily accepted, and still accepts, government subsidies. The west has always failed to admit its dependence on outside forces. Thus, taking pioneer rhetoric at face value may lead, one may come to the same conclusions as Turner, however, if one looks under the surface, one finds layer upon layer of denial. Additionally, as Eric Foner describes the Reconstruction era as exemplifying the increase in federal government power, Limerick assigns the westward movement with much the same role. The Homestead Acts and other property laws are the quintessential example of the increased role of the federal government in the lives of the American people.

The passion for property, Limerick claims, not the thirst for adventure and equal opportunity, was the main drive in westward expansion. Much of western history is the story of individuals trying to affix the concept of property on things that are not easily categorized, such as minerals and wild animals. Turner’s story of the frontier may make sense if one only looks at the agrarian side of things, even then farming was linked to commerce in the West, but the western economy was far more diversified. One industry that Turner ignores, which Limerick thinks is the most important, is mining. Furthermore, Turner’s assertion that the taming of the wilderness was the goal and ultimate success of the settlers does not take into account the fact that nature does not cooperate and often times fights back. The most prevalent example of this battle between humans and nature is the uneven distribution of water and the challenges this imposes upon farmers and townspeople alike. Another example involves the national parks, and the fact that their borders are not natural, but politically and economically based, and thus, plants and animals often do not respect the border much to the annoyance of the people and often the detriment of the creatures.

Limerick also challenges the Turner’s claim that the west was a center of democracy and equality. The West was a meeting ground of diversity, she argues, a diversity that is completely ignored by Turner. Once women, Indians, Mexicans, and other minorities enter the picture, Turner’s egalitarian landscape is immediately shot to pieces. Examination of the role of the prostitute in western history easily dissolves the myth of equality, as it is an example of white people discriminating against other white people in an effort to lift up those women that were deemed respectable. Native Americans were also done a disservice by traditional western history as it “flattened” their history out, made them inconsequential, and homogenized disparate groups of people into one, all-encompassing category. Limerick states that while white Americans have their own history of the West, the Native Americans have a much different version. Limerick asserts that this is perfectly okay and that the modern historian must embrace relativism and its dismissal of the concept of a universal, authoritative history. However, no group was ignored more by the original frontier thesis and is more relevant to today’s situation in the area than the immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries. Willing to do labor for much lower wages than American workers, the Hispanic immigrant’s role in American society has always been and continues to be controversial and much contested.

Both men and women, before setting out for the frontier, had a preconceived notion of the frontier that involved the twin forces of wilderness and savagery. What drove them westward and fueled much of the atmosphere in the country at that time, as Limerick points out, was the desire for material progress. Both men and women dreamt of the potential of the wilderness to which they were moving. Although women tended to be more optimistic and romantic in their viewpoints than men, both sexes experienced mixed feelings of hope and anxiety. Both men and women were susceptible to the pits of racial prejudice. Popular accounts portray all women as hating both wilderness and Native Americans, however, when one reads their journals, one finds that they were initially fearful of the Indians, but soon were able to accept their presence. Women tended to be more peaceful in their relations with the Natives and based opinion, not on generalizations, but rather on an individual basis. Although women certainly had a great deal of work to do while on the trails and at their new homes, Myres says that there is no basis to assume that these women were “trail drudges.” Upon arriving in their new home, some women were pleased and some were disappointed. Some women were happy in their married life, some worried that their husbands were not happy, and some were so unhappy in their married life that they divorced. However, women were not only interested in married life and homemaking; upon arrival in their new communities most women became involved in the twin forces of civilization, education and religion. Because they were so involved in their communities, western women were the first contingent to make large strides in women’s suffrage, Myres asserts.

The stereotypes of the bad woman and the Madonna of the Prairies were stereotypes, but not myths, according to Myres. Women that fit into these roles did exist, but were not the majority. The reason that they are given so much attention is because their experiences stuck out of the crowd. However, after reading Myres’ account, one more fully appreciates why these stereotypes were focused on. Quite simply, they are interesting. Though based on a noble and potentially appealing concept, Myres’ account falls flat. In an effort to focus on the diverse experiences of the women of the prairies, Myres causes the women of her story to get lost in a sea of monotony and mediocrity. The endless use of phrases such as “just as” and “not only,” cause the narrative to become predictable. In almost every circumstance there are women that experience both ends of the emotional spectrum, and, inevitably, the men had much the same experience. In her introduction, she says that she wants to emphasize that these women were not isolated occurrences deserving a blurb at the end of a chapter, but rather they were integral parts of the frontier experience. However, in her narrative, Native American and African women are tacked on as simply another “just as” at the end of a section devoted to white women, severely underplaying the uniqueness of their experience. If Myres did not intend to give these women their due, then they should have been left out of the story.

While Limerick tries her hardest to dissolve the potency of the Frontier Thesis, Myres does much to reinforce its authority. This desire to continue Turner’s legacy probably has a great deal to do with Myres’ connection to Ray Allen Billington, who was a western historian who spent much of his career reshaping the Frontier Thesis to the changing perceptions of the present. Myres, not the accounts she is assessing, refers to these women as “hardy and self-sufficient” (270), descriptors that have obvious foundation in the Frontier Thesis. One gets the feeling that the problem that Myres has with the “new” histories of the West is that they completely tear apart Turner’s claims of western equality and egalitarianism. These histories concluded that women were not a part of the opportunities that arose in the West. Not only was there equality of opportunity, but women were a part of this opportunity, according to Myres. Despite the shortcomings of Myres’ narrative, she does show that women in the West were able to challenge the traditional gender roles that dominated Eastern social circles, and were able to take some of the earliest steps in the nation towards gender equality.

A large fraction of Cunfer’s analysis is based on statistical research and empirical analysis, which he believes helps him to avoid the ideological pitfalls that ensnare the cultural and social environmental historian. Using data, particularly acreage sums, from Agricultural Censuses, Cunfer plots the data on maps using a Geographic Information System or GIS. The GIS creates a map that is easily readable and makes patterns in the land and environment easily discernable. In an effort to soften the harshness of his empirical research, personal stories and case studies are interspersed amongst the numbers and maps. The story of Elam Bartholomew is used as an exemplification of the typical experience of a farmer during the plowing revolution in the Great Plains. By plotting percentages on a map of the Great Plains, Cunfer is able to dispel the conviction that much of the Great Plains has been altered by the plow. In fact, Cunfer is able to show that only seventy percent of the Great Plains as has ever felt the harsh clawing of the plow. However, Cunfer is quick to state that this is not due to any kind of preservationist agenda on the part of the farmers. If left to the will of capitalism and other economic and political incentives, it is likely that all of the land would have gone under. Human ideology and determination is often no match for environmental limitations, however. Similarly, by mapping the percentage of acreage used for cattle, Cunfer is able to note that water distribution determined where cattle grazing could occur and limited the number of cattle that could be sustained. Thus, cattle ranchers were forced largely to obey the rules of the ecological systems that were already in place. Charting the diversity in croplands, Cunfer is able to show that monoculture has never been the norm in the Great Plains, although it is threatening to become so in the present-day. He also tracks the growth of tractor usage in the Great Plains to illustrate the pattern of the shifting of labor intensity.

The most groundbreaking portion of Cunfer’s study is his work on the origins of the Dust Bowl. Directly challenging the claims of Donald Worster and other environmental historians, Cunfer does not believe that over-plowing, due to the pressures of evil capitalism, was the main impetus for the environmental catastrophe. Instead, using GIS technology, Cunfer is able to show that drought and high temperatures, which are natural disruptions, were the real cause of the Dust Bowl. Cunfer believes that environmental historians must start taking these natural disruptions and other natural forces into better consideration when analyzing the history of human interactions with the land. Environmental history has swayed too far to the cultural camp, causing it to lose sight of the very nature that it set out to study, and must swing back towards the inclusion of proportional amounts of environmental determinism. Cunfer’s analysis is based on a particular understanding of sustainability. Cunfer does not equate sustainability with economic patterns, but rather with the stableness of land-use. The people of the Great Plains are constantly involved in the dance of unstable equilibrium, constantly making adjustments to their system in order to keep stability. The fact that, despite economic upturns and downturns, the land use of the Great Plains has remained the same for nearly one hundred years denotes, according to Cunfer, that their agricultural practices are sustainable. This does not mean that environmental degradation has not occurred, as any system placed on the land changes it, but rather that the Great Plains agriculture has been able keep a level of diversity that is necessary for sustainability. Increased pressures from agro-corporations, such as Monsato, threaten to disrupt this balance. The moment the people of the Great Plains step out of their environmental limits their agricultural system will no longer be sustainable and either they will have to take a step backward or abandon their way of life for a new one.

In each account of the West, the area acts as a stage for the author’s chosen story. For Turner, the West was a place where American exceptionalism could take root and prosper, the perfect landscape for self-betterment and the spread of morality and equality. In Limerick’s tale the West serves largely as a meeting place of diversity and a fertile bed for the proliferation of the American obsession with property and material gain. For Myres it served as a place where women were able to break free from the confines of traditional gender roles and start the journey towards equality. And for Cunfer, the West serves as a stage for the uneasy tango between man and nature as each entity struggles to maintain control. These portrayals of the West demonstrate how diversely a place’s past can be interpreted, and the immensely complicated enterprise historians undertake when they set about to reconstruct the past.

Feature Photo: Title: A Digger Indian family Creator(s): Thunen, William, photographer

- Date Created/Published: c1906.

Share this:

Published by jessica m. dewitt.

Dr. Jessica M. DeWitt is an environmental historian of Canada and the United States. She is passionate about the use of digital technologies to bridge the gap between the public and researchers. In addition to her community and professional work, she offers various editing and social media consultancy services. View more posts

Join the Conversation

- Pingback: Canadian History Roundup – Week of August 6, 2017 | Unwritten Histories

Leave a comment

Cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Sign in to access Harper’s Magazine

We've recently updated our website to make signing in easier and more secure

Hi there . You have 1 free article this month. Connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access

You've reached your free article limit for this month. connect to your subscription or subscribe for full access, thanks for being a subscriber, the persistence of the frontier, this article is only available as a pdf to subscribers..

Download PDF

October 1994

“An unexpectedly excellent magazine that stands out amid a homogenized media landscape.” —the New York Times

- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

European Studies : Ask a Librarian

Have a question? Need assistance? Use our online form to ask a librarian for help.

- Matthew Young, Reference Specialist, Latin American, Caribbean & European Division

Note: This guide is adapted from an earlier version, which first appeared on the European Reading Room website in 2002.

Created: March 12, 2024

Last Updated: March 12, 2024

Meeting of Frontiers was a project, originally funded by the United States Congress, devoted to the theme of the exploration and settlement of the American West, the parallel exploration and settlement of Siberia and the Russian Far East, and the meeting of the Russian-American frontier in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. You can find more information about the project here as well as the related digital collection.

A conference dedicated to "Meeting of Frontiers" was held at the University of Alaska Fairbanks in 2001, taking place over three days from May 17th to May 19th. The event was sponsored by the Library of Congress, the Rasmuson Library at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Open Institute of Russia and the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Bringing together scholars and experts from the United States and Russia, the conference featured presentations related to the themes of "Meeting of Frontiers," such as Russian and American frontier history, the Russian-American company and Russian Orthodoxy in Siberia and Alaska.

This guide contains the presentations given at the "Meetings of Frontiers" conference. There are presentations in English and Russian. The presentations are organized according to the sessions of the conference. It should be noted that Session III of the conference consisted of a live demonstration of the "Meeting of Frontiers" website and, thus, is not represented in the guide.

- Next: Opening Remarks >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 1:39 PM

- URL: https://guides.loc.gov/meetings-of-frontiers-conference

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

Patricia Nelson Limerick’s “The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West”

- Word count: 1612

- Category: History

A limited time offer! Get a custom sample essay written according to your requirements urgent 3h delivery guaranteed

In her definition of the New Western History, Patricia Nelson Limerick views the West as a region, rejecting the term “frontier” as the best demarcation for the processes playing out in that region. Instead, Limerick proposes such terms as “conquest”, “invasion”, “exploitation”, “colonization”, “development”, and “expansion of the world market”. In all her works, the author highlights the convergence in the West of diverse peoples; rejects the notion of the end of the frontier with its implied divide between old West and new West; and questions the traditional model of progress and improvement. Limerick had first outlined these points a in the very influential book: The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West .[1]

Limerick clearly states the book’s thesis in the introduction. The author is bothered by propensity of historians to peg the history of the American West onto dates, for example, 1607, 1620, 1865, and, of course, 1890. Completely aware that Westerners, when they heard of the Census Bureau announcement of he frontier’s end, did not drop what they were doing, pause for a few moments, and then go back to business in a different mode, Limerick has written a book that stresses “the unbroken past of the American West.” For her, rejecting the frontier as the overriding thematic framework for structuring the story of the West would lead to a fuller recognition of the region’s tremendous cultural diversity and to an emphasis on its twentieth-century history and the continuities between the 19th century western past and the present.

In this book, the author proposes that the “history of the West is a study of a place undergoing conquest and never fully escaping its consequences”.[2] In these terms, Western history has distinctive features as well as features it shares with the histories of other parts of the nation and the planet. Under the Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis”, Western history stood alone. In addition, Limerick also proposes in the book that, an “ongoing competition for legitimacy-for the right to claim for oneself and sometimes for one’s group the status of legitimate beneficiary of Western resources. This intersection of ethnic diversity with property allocation unifies Western history”[3] was associated with conquest.

According to Limerick, the frontier did not end in 1890 and that the history of the West is unbroken since it first began. According to the author, “Deemphasize the frontier and its supposed end, conceive of the West as a place and not a process, and Western American history has a new look.”[4] In The Legacy of Conquest , Limerick utilizes select examples from the 19th and 20th centuries in supporting her thesis. The book rests on a selective but broad foundation of published scholarship, primary sources, and newspapers and periodicals.

After stating the thesis, the author devotes most of The Legacy of Conquest to aspects of conquest. Western history spans from before European arrival to the mid-1980s and from the High Plains to the Pacific: the western region, not the processual frontier. The chapter topics include several continuous themes, including the need for self-justification and a sense of moral innocence in order to undertake efficient conquest.

Another major subject is the passion for property, especially real estate. Dependence on the federal government, and on other people, made conquest possible, but so did the insistence that the West means independence. Conquest meant hard work, much of it wage labor in mines or agribusiness, with rewards well below the Jeffersonian ideal. Further continuities include water disputes, the key role of federal money, the boom-and-bust character of mining and oil searches, the West always promising more than it delivered, the unintended consequences of western development, the persistence of outlaws.

The last half of the book discusses problems and groups demonstrative of conquest: Indians, the clash of cultures in the borderlands, the complexity of race relations, and the conservation-preservation struggle. The final and summary chapter is scattershot, but still stimulating. Limerick juxtaposes the present with often long-past events to illustrate the themes of conquest and continuity.

A large part of The Legacy of Conquest directly tackles the economic dimension of western history. It seems that Limerick was influenced by cultural anthropology when she wrote the book. In her work, the author questions the perspectives historians have used to write about and interpret the West, particularly its economic life. Limerick writes:

White Americans saw the acquisition of property as a cultural imperative….There was one appropriate way to treat land–divide it, distribute it, register it. This relation to physical matter seems so commonplace that we must struggle to avoid taking it for granted…[5]

The above perspective permeates the approach of many culture-bound historians. Limerick notes that the fight to obtain water and mineral rights for profit and property has been similarly misinterpreted as a product of rational behavior. As an alternative, the author argues that, it was born of a passion, a passion for profit. She writes:

…[T]he dominance of the profit motive supported the notion that the pursuit of property and profit was rationality in action, and not emotion at all. In fact, the passion for profit was and is a passion like most others.[6]

While Americans have enshrined the area in myth, the author suggests that there is nothing mythic about the American West, since it has a history deeply rooted in primary economic reality. Even though economic realities have shaped the West, Americans as well as professional historians have not perceived them as such. Limerick’s survey embraces a wide range of cultural, ethnic, social, and political influences which she feels have shaped the contours of the West.

For Limerick, the study of the West is of great importance for American history in general; this is largely because the West as a place remains an important meeting ground for Blacks, Spaniards, Indians, Asians, and Anglos. Additionally, The West’s diversity of religions, languages, and cultures surpasses that of the East or the South.

The machinery of conquest have drawn the different Western ethnic groups together in the same story. The farm crises, the struggle over water rights, the controversies over immigration and bilingualism, America’s relations with Mexico, the boom and bust cycles in the oil, copper, and timber industries, the conflicts over Indian resources and tribal autonomy, and many other matters still hold the attention of Westerners. According to Limerick: “Reconceived as a running story, a fragmented and discontinuous past becomes whole again.”[7] Turner’s frontier thesis may be outdated, but the West is still alive and vibrant.

Limerick’s The Legacy of Conquest is an arresting new synthesis of the history of the West. He author highlights perceptions and interpretations of familiar topics and bases her research largely on secondary works, and newspapers for the more recent period. Its major strength is that it offers a good synthesis of secondary works and of articles – especially about the environment, Mexicans, and Indians – appearing in existing newspapers and magazines. She writes in a smooth and entertaining style. Historians who are interested in economics, and who wish to reconsider frameworks and approaches to studying the history of the West may want to pay attention to this book.

The Legacy of Conquest can be considered more as an extended essay instead of a traditional monograph. This gives the reader the distinct impression that the author is surest of herself when dealing with twentieth-century topics. In this book, Limerick’s prose is sharper and her reasoning is more convincing compared to other traditional monograph. In addition, the reader feels that the author is revealing more confidence in this work as a result of her extensive research. Overall, the author is a very engaging writer and, mostly, argues her case very well.

On the minus side, other chapters of the book leave one flat. This flaw may be because of Limerick’s limitation of the American West to Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa, and west to the Pacific. This is obvious in the author’s discussion of the “unbroken past” brings the reader back to the East Coast and to colonial times and again and again. Moreover, it is surprising that the book pays little attention to the fur trade. A more extensive discussion of the fur trade could have added more strength to her main thesis. It would broaden the author’s argument back to the 16th century, and it involved ruthless business practices, an out of control search for profits and resources, and geopolitical games for empire.

Overall, Limerick’s The Legacy of Conquest is an important and influential refutation of the old myths and theories, providing readers with a deeper and broader understanding of the real West and its history. The author provides more than a valuable contribution to examining the American West; it can be considered as a classic in the field of American Western history. While western studies scholars may find few new insights in this book, in terms of facts, they should find The Legacy of Conquest intriguing because of Limerick’s arguments, which are very much supported by evidence and reasonable interpretations. This book is also useful for specialists outside of western studies, for starting courses both at the undergraduate and graduate levels, and for lay readers concerned with the West and its role in national history.

[1] Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The unbroken Past of the American West , New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987.

[2] Limerick, 26.

[3] Limerick, 27.

[4] Limerick, 26-27.

[5] Limerick, 55.

[6] Limerick, 77.

[7] Limerick, 27.

Related Topics

We can write a custom essay

According to Your Specific Requirements

Sorry, but copying text is forbidden on this website. If you need this or any other sample, we can send it to you via email.

Copying is only available for logged-in users

If you need this sample for free, we can send it to you via email

By clicking "SEND", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

We have received your request for getting a sample. Please choose the access option you need:

With a 24-hour delay (you will have to wait for 24 hours) due to heavy workload and high demand - for free

Choose an optimal rate and be sure to get the unlimited number of samples immediately without having to wait in the waiting list

3 Hours Waiting For Unregistered user

Using our plagiarism checker for free you will receive the requested result within 3 hours directly to your email

Jump the queue with a membership plan, get unlimited samples and plagiarism results – immediately!

We have received your request for getting a sample

Only the users having paid subscription get the unlimited number of samples immediately.

How about getting this access immediately?

Or if you need this sample for free, we can send it to you via email.

Your membership has been canceled.

Your Answer Is Very Helpful For Us Thank You A Lot!

Emma Taylor

Hi there! Would you like to get such a paper? How about getting a customized one?

Get access to our huge, continuously updated knowledge base

- Quick Facts

- Sights & Attractions

- Tsarskoe Selo

- Oranienbaum

- Foreign St. Petersburg

- Restaurants & Bars

- Accommodation Guide

- St. Petersburg Hotels

- Serviced Apartments

- Bed and Breakfasts

- Private & Group Transfers

- Airport Transfers

- Concierge Service

- Russian Visa Guide

- Request Visa Support

- Walking Tours

- River Entertainment

- Public Transportation

- Travel Cards

- Essential Shopping Selection

- Business Directory

- Photo Gallery

- Video Gallery

- 360° Panoramas

- Moscow Hotels

- Moscow.Info

- History of St. Petersburg

- St. Petersburg (Petrograd) under Lenin: The Civil War and its aftermath

St. Petersburg (Petrograd) under Lenin: The Civil War and its aftermath (1918-1924)

Lenin may have become the ruler of Russia and Petrograd the first socialist capital, but a successful revolution here did not mean that the rest of the country had obediently followed suit. There were still vast territories that did not recognize Bolshevik rule. Although Lenin quickly negotiated a devastating separate peace with Germany which resulted in the loss of enormous tracts of land, the country itself erupted into brutal Civil War as Tsarist forces clashed with Red Guards. In this perilous situation, Russia's capital was, after a two hundred year interlude on the Neva, returned to Moscow, a greater distance from the insecure border, in March 1918.

Petrograd experienced mass exodus. The government bureaucracy with its attendant hordes of ministers, clerks, and military personnel relocated to Moscow, able-bodied men were embroiled in the Civil War, and civilians absconded to the countryside where food was easier to procure. Likewise, the wealthy and aristocratic, a targeted class under the new regime of workers and peasants, fled to safer grounds. Vladimir Nabokov, who had spent his childhood in a luxurious mansion within the shadow of St. Isaac's Cathedral, escaped on the last ship out of Sebastopol. Rasputin's aristocratic murderer Felix Yusupov - jewels and two Rembrandts in hand - was part of the royal entourage that crammed onto a warship in Yalta, kindly provided by the British for the Tsar's mother. Those who remained often ended up corpses: four Grand Dukes, including the Tsar's uncle, were shot in the Peter and Paul Fortress in 1918. As a result of this turmoil, in four years the population of the city was reduced by more than two-thirds, sinking from 2,400,000 in 1916 to 740,000 in 1920.

Meanwhile, the battle for political education was also under way. Geographical signposts were used to educate the populace in the ideas and ideals of the new regime and to eliminate associations with St. Petersburg's imperial and religious past. As it was clearly impossible for a self-respecting socialist city to have one of its main waterways named in honour of Catherine the Great, the Ekaterinsky Canal was renamed Canal Griboedova in 1923, after the nineteenth century aristocratic author and diplomat who Soviet historians rather improbably deemed an honorary Marxist.

Street names with religious overtones were likewise deemed inappropriate by the atheistic government. Thus, the square in front of the Moscow Railway Station, previously called Znamenskaya Ploshchad after the nearby Church of Our Lady of the Sign ( Znamenskaya Tserkov ), was renamed Ploshchad Vosstaniya ("Uprising Square") to commemorate the numerous revolutionary protests that had occurred here (the church itself was torn down in 1940, a fate which befell many churches throughout the land). In 1918, the city's grand central avenue, Nevsky Prospekt, was rechristened Ulitsa Proletkulta after the Organization of Proletarian Culture and Enlightenment, a short-lived experimental artistic institution (the Soviet passion for snappy portmanteau abbreviations quickly came to dominate not only the official language of the era, but also the toponymy of Russia's cities). In the same year, the Winter Palace, former residence of the Tsars, was renamed Palace of the Arts, and Palace Square became Ploshchad Uritskogo ("Uritsky Square").

But who was Uritsky? The story of this man is telling for the times. A Bolshevik revolutionary, Moisey Uritsky became head of the Petrograd Commune Commissariat for Internal Affairs and the Extra-Ordinary Commission - in other words, the infamous Cheka. This organization, which aimed at eliminating even the weakest or even non-existent opposition to the new social order through brutal terror, was founded in Petrograd within weeks of the revolution, with headquarters at 6, Palace Square in the former Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Here Uritsky coordinated the pursuit, prosecution, and execution of monarchists, military personnel, clerics, and others who opposed the Bolshevik regime. And here, on 30 August 1918, he was assassinated by a young military cadet in retaliation for the execution of several officers.

This event, along with an attempted assassination on Lenin, served as the pretext for the Red Terror, a wave of mass killings, torture, and repression that targeted anyone who dared to criticize the new regime, in particular the bourgeois and the nobility. By 15 October, when the Red Terror officially ended, 800 alleged enemies had been shot in Petrograd alone and more than 6,000 imprisoned. But the unofficial Terror continued on until the end of the bloody, tumultuous Civil War in 1921 when the Bolsheviks finally emerged victorious over those forces loyal to the ancien regime .

We can help you make the right choice from hundreds of St. Petersburg hotels and hostels.

Live like a local in self-catering apartments at convenient locations in St. Petersburg.

Comprehensive solutions for those who relocate to St. Petersburg to live, work or study.

Maximize your time in St. Petersburg with tours expertly tailored to your interests.

Get around in comfort with a chauffeured car or van to suit your budget and requirements.

Book a comfortable, well-maintained bus or a van with professional driver for your group.

Navigate St. Petersburg’s dining scene and find restaurants to remember.

Need tickets for the Mariinsky, the Hermitage, a football game or any event? We can help.

Get our help and advice choosing services and options to plan a prefect train journey.

Let our meeting and events experts help you organize a superb event in St. Petersburg.

We can find you a suitable interpreter for your negotiations, research or other needs.

Get translations for all purposes from recommended professional translators.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Frontier Thesis, also known as Turner's Thesis or American frontierism, is the argument advanced by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893 that the settlement and colonization of the rugged American frontier was decisive in forming the culture of American democracy and distinguishing it from European nations. He stressed the process of "winning a wilderness" to extend the frontier line ...

Patricia Nelson Limerick isn't setting out to discredit Frederick Jackson Turner as an historian and scholar. And it isn't that she believes his influential "Frontier Thesis" was without merit. On the contrary, she describes Turner as a "scholar with intellectual courage, an innovative spirit, and a forceful writing style" whose thesis served a purpose in the late 19 th /early 20 ...

Limerick pushes for a continuation of study within the historical and social atmosphere of the American West, which she believes did not end in 1890, but rather continues on to this very day. Urban historian Richard C. Wade challenged the Frontier Thesis in his first asset, The Urban Frontier (1959), ...

Patricia Nelson Limerick's book The Legacy of Conquest is a likely candidate, it seems to me, for such a role. It appeared in 1987 from W. W. Norton and has been widely reviewed, both by the discerning and enthusiastic and by the puzzled and unimpressed. Our intention in this panel is to continue that reviewing process: to understand as clearly ...

Patricia Nelson Limerick is a professor of history at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Her work, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West is considered to be one of the seminal works in the field of New Western History. Turner's Frontier Thesis, Limerick comments, became the rendition of western history in the ...

Colorado and still in her thirties, Limerick has authored the book under re-view here. Turner, of course, has been dead since 1932. Yet even before his demise, the frontier thesis came under scholarly attack. Perhaps no single theory of American history has undergone such extensive explication and evisceration.

In his Frontier Thesis, ... In these changes Limerick reorients the way historians think of Western history, as she writes, "Reorganized, the history of the West is a study of a place undergoing conquest and never fully escaping its consequences. In these terms, it has distinctive features as well as features it shares with histories of other ...

In the book's introduction, titled "Closing the Frontier. Western History," Limerick insisted that rejecting the frontier thematic framework for structuring the story of the West would recognition of the region's tremendous cultural diversity and. David M. Wrobel is a professor of history at the University of Nevada,

The Legacy of Conquest. Limerick takes issue with the commonly accepted notion that the year 1890 marked the closing of the American frontier and the end of an era made unique by Indian wars ...

The "frontier thesis" essentially is that the United States is unique because it has always had a frontier with "free land" available. For this reason, people have always been able to move westward.

Claim B. Young historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his academic paper, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago on July 12, 1893. He was the final presenter of that hot and humid day, but his essay ranks among the most influential arguments ever made regarding American ...

The end of the frontier is not the only part of Turner's thesis that Limerick has a problem with, however. Firstly, Limerick tears apart Turner's assertion that the western settlers were rugged, individualistic, and independent. Limerick asserts that those that moved west viewed their motives as innocent and commonplace.

New western historian Patricia Nelson Limerick challenges many elements of the Turner thesis in her 1987 book The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West; for example, Limerick highlights the cultural diversity of the West and the competition for resources among various ethnic groups as critical to the historical development ...

In short, where Turner viewed the frontier as a process where American democracy was renewed and revitalized, Limerick regards it as a place conquered by the United States, a colonial power.

Stanford via Stanford University Press. Figure 17.9.1 17.9. 1: American anthropologist and ethnographer Frances Densmore records the Blackfoot chief Mountain Chief in 1916 for the Bureau of American Ethnology. Library of Congress. In 1893, the American Historical Association met during that year's World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

Frontier in American CuIltutre (Berkeley, Calif., 1994), 66-102. For attempts to reconstruct (and rescue) ... 3The rejection of openings and closings in favor of an emphasis on continuity is the thesis of Limerick, Legacy of Conquest. For a literary turn in the same vein, see Jos6 David Saldivar, The ...

The persistence of the frontier. ... Adjust. Share. by Patricia Nelson Limerick, This article is only available as a PDF to subscribers. ... Download PDF. Tags. Frontier (The word) Frontier thesis. From the. October 1994 issue Download PDF From the Archive. Timeless stories from our 174-year archive handpicked to speak to the news of the day.

The Alaska Line. 1934. Library of Congress Geography & Map Reading Room. Meeting of Frontiers was a project, originally funded by the United States Congress, devoted to the theme of the exploration and settlement of the American West, the parallel exploration and settlement of Siberia and the Russian Far East, and the meeting of the Russian-American frontier in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest.

According to Limerick: "Reconceived as a running story, a fragmented and discontinuous past becomes whole again."[7] Turner's frontier thesis may be outdated, but the West is still alive and vibrant. Limerick's The Legacy of Conquest is an arresting new synthesis of the history of the West. He author highlights perceptions and ...

From Moskovskaya metro station walk one block South, then enter the monument via the underpass, which is located near the two tall buildings. Where? Ploschad Pobedy (Victory Square) Metro: Moskovskaya. Telephone: +7 (812) 371-2951. Open: Thursday to Monday, 11 am to 6 pm, Tuesday, 11 am to 5 pm.

One of two fascinating gothic churches designed by the German-Russian court architect Yury Felton, the Chesme Church was consecrated in 1780, on the tenth anniversary of Russia's naval victory over the Turkish fleet at Chesme Bay, which occurred on the birthday of John the Baptist, hence the church's name. A wedding-cake structure with striped ...

St. Petersburg (Petrograd) under Lenin: The Civil War and its aftermath (1918-1924) Lenin may have become the ruler of Russia and Petrograd the first socialist capital, but a successful revolution here did not mean that the rest of the country had obediently followed suit. There were still vast territories that did not recognize Bolshevik rule.

Problems detected. Users are reporting problems related to: internet, phone and wi-fi. The latest reports from users having issues in St. Petersburg come from postal codes 33703 and 33707. Frontier Communications Corporation is a telecommunications company in the US and the fourth largest provider of digital subscriber line.