Wartime Innovation and Learning

By Frank G. Hoffman Joint Force Quarterly 103

Download PDF

W ars are the ultimate test for any armed service. They reveal how well military institutions perceived the context of future conflict, how they prepared for war, and how their force design and development processes succeeded in anticipating threats and exploiting emerging technologies. The strategic environment characterized by the 2018 National Defense Strategy is one of significant technological change and diffusion, opening new opportunities for improving U.S. military effectiveness. But the same disruptive advances are also available to potential adversaries. 1 This reality led to then–Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s injunction in the National Defense Strategy “to create a culture of experimentation and calculated risk taking” to construct new sources of advantage by combining material, conceptual, and organizational change to generate innovative warfighting capabilities and sustain our competitive edge. 2

Pursuant to the strategic direction outlined by the Department of Defense, the Joint Staff evolved its Joint Force Design and Development activities to better enable the joint force to generate and maintain its competitive advantage, improve force posture, and increase the joint force’s responsiveness in this dynamic environment. 3

The Joint Chiefs have operationalized the strategic direction in the National Defense Strategy via the latest vision for joint professional military education (JPME). That vision defines a key learning objective for U.S. military officers, tasking them to “nticipate and lead rapid adaptation and innovation during a dynamic period of acceleration in the rate of change in warfare under the conditions of Great Power competition and disruptive technology.” 4 That vision is further reinforced in the latest version of the Officer PME Policy issued in 2020, which defined the requirement to prepare officers to recognize the need for change and to lead transitions as desired educational outcomes. 5 However, these are not just peacetime tasks distinct from warfighting. As recent scholarship demonstrates, the side that is open to self-assessment in wartime—and reacts faster—increases its chances of prevailing in peace and in war. 6

The following case study details how one leader effectively integrated new operational concepts with a novel technological device to generate a capability in a combat theater. A collection of adaptations produced a new military innovation that was developed and tested incrementally and then applied in wartime. It is a great example of the integration of the research and development community operating forward in time of war to improve a new technology. A few insights regarding leadership and JPME can be drawn from this example. There are no detailed blueprints that we can draw upon for how to best exploit new technologies in every case, but history remains our best source for generating the right questions in the future.

Learning in Action

There is a lot of scholarship that details the enormous value of the U.S. Navy’s pre–World War II learning system and how well the Service forecasted the contours of the tough Pacific campaigns. The Navy’s interwar development of a campaign strategy known as War Plan Orange, its longstanding plan for responding to Japanese aggression in the Pacific, is well chronicled. 7 More recently, Trent Hone extended this narrative, focusing on the achievements of the Service’s surface force before and during World War II. 8

An appreciation of the development and exploits of the U.S. submarine force in the Pacific campaigns is emerging, 9 and the learning within the “Silent Service” is the focus of this article. Operational leaders recognized that critical challenges limited our submarines against the Japanese empire, and they overcame these with creative plans and rigorous experimentation. 10 These developments culminated in not only a daring operation that could be the Navy’s greatest raid but also a model for combat leadership and adaptation in wartime.

The principal actor in this case study is Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood. He was considered among his peers as the chief advocate for the long-range fleet submarine during the interwar period and was called “Mr. Submarine.” 11 Postwar reports comment positively on Lockwood’s operational leadership. Known for an informal style and for being a gentle critic and dedicated mentor, he defended subordinates and reflected “loyalty down” rather than just demanding compliance. 12 He deferred to his commanders because he understood that they had the best insights, once noting, “I make my decisions based on reports from boat commanders sent through their superiors, not from intuitive estimates or guesses. I rely heavily on the judgments of those in command of the submarines on the spot, and wholeheartedly support their decisions because they are there.” 13

Lockwood was open to new ideas and actively sought out commanders such as the highly successful Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton for personal interviews. He read and commented on the reports written by the boats after each patrol. Lockwood attempted to ensure he had the best information from the fighting units of his command. He would personally meet each boat as it returned to port and would go over reports with the commanders. 14 He also repeatedly sought to get operating time inside the more modern boats being deployed with new technologies such as the Torpedo Data Computer and sonar radar. He collected insights and evidence from many sources and even sought contradictory information. In doing so, this hands-on approach ensured that new concepts for fighting the war came not just from the top down but also from the bottom up and middle out. 15

His subordinates described him as “not conformist and against rule book thinking.” 16 Lockwood was willing to experiment in theater with live ordnance under realistic conditions, whether to fix faulty torpedoes or to adapt new weapons and detection systems. He was also willing to press hard to get necessary changes and confronted Admiral Chester Nimitz and the naval bureaucracy to get the support he needed. 17 Lockwood was persistent in trying to enhance the effectiveness of his force and was open minded about new tactics and new technologies. As a model for wartime adaptation, one is hard pressed to find a better example than Lockwood.

While the contours of War Plan Orange and the Navy’s extensive wargaming played out in the early stages of the war, the submarine force had to adjust its doctrine and rectify several material deficiencies. 18 In particular, flaws in their torpedoes marred the forces’ performance. This led to a lot of frustration in the fleet, but solutions were found by the middle of 1943 to correct these shortcomings. By the end of 1943, the Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet (SUBFORPAC), was carrying out an aggressive campaign of attrition on Japan’s sea lines of communication. 19

Admiral Lockwood, commander of SUBFORPAC since February 1943, realized that the closer the campaign moved toward Japan’s home islands, the harder resistance would be. Operations would be conducted in shallow and possibly mined waters, and with far greater exposure to land-based air reconnaissance. Moreover, the Japanese were becoming more effective at antisubmarine warfare. He anticipated his force would need to seek out new methods and capabilities to improve its offensive and defensive tool kit.

The initiation of wolf packs by SUBFORPAC was one of these new methods. They were directed from Washington by Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Ernest King in April 1943. The submarine community had been skeptical of Collective Action Groups, as King called them, due to poor ship-to-ship communications and the potential for inadvertent “blue-on-blue” incidents. The community recognized that it had different operational conditions (longer ranges, less maneuver space, and fewer targets) than the German navy faced in the Atlantic. Its problem was not with large convoys; it needed to find small targets in a big ocean. Rather than embrace the German Kriegsmarine ’s melees at sea, SUBFORPAC staff members evolved their own approach. 20 These tactics overcame Lockwood’s skepticism, using improved radios and a training program crafted by combat veterans. These tactics were employed for the first time in October of 1943 and refined well into 1944.

Partly due to better torpedoes, as well as more boats and updated tactics, the results generated by Lockwood’s command were much improved in 1944. More submarines, with shorter transit distances from Guam and Saipan, produced intensive patrols in closer contact with Japan’s defense. SUBFORPAC reported 520 combat patrols, 50 percent more than 1943, using an increased number of submarines with shorter routes. With torpedoes now both plentiful and functioning, the Navy’s submarines surged against their targets. They fired more “fish” in 1944 than in all of 1942 and 1943 combined. They sunk more than 600 ships and put 3 million tons of shipping to the bottom of the Pacific. Japan’s imports were slashed by one-third, and its commercial fleet was reduced by half, from 4.1 to 2 million tons. Oil imports dropped sharply, which severely impeded Japan’s military operations and training. But the force’s aggressive attacks were met by new Japanese interest in antisubmarine capabilities, including patrol planes and better radars. In 1943, the fleet lost 16 boats and their crews—including the highly regarded Commander Morton and his boat, the famous USS Wahoo . 21 The following year, another 19 U.S. boats were lost. 22 Operational success was being achieved, but at a price.

New Opportunities

These losses troubled Lockwood, but they also made him redouble his efforts to enhance the capabilities of his force. For some time, Lockwood had worked to create an innovative plan to unlock the Sea of Japan, a triangle-shaped area covering nearly 400,000 square miles, bordered by Korea, Russia, and the Japanese islands. The seeds of that operation can be traced to a trip Lockwood made to San Diego in April 1943 to visit the shipyards and infrastructure supporting his force. The admiral paid a visit to the University of California’s Division of War Research, which was run by Dr. George P. Harnwell, a physicist. Harnwell gave an overview of the various technologies being explored to support the Navy. Lockwood recalled their briefing as a “Wonderland of Ideas,” but many were not yet mature or seaworthy. 23 One of these was a new detection sensor they called Frequency Modulated Sonar (FMS), which was still in its infancy. Lockwood admitted later that he did not anticipate how valuable FMS might become at the time.

FMS operated like regular sonar, transmitting a signal that returned to its originating source where the echo produced a visual display on an indicator plot screen. What was unique about FMS is that its signals were silent and did not emit an audible ping that could be detected by the opponent. The system showed an ability to locate subsurface objects, including nets, whales, schools of fish, and rocks/shoals, all of which were displayed in bright green pear-shaped signals on the screen. The system included a speaker that would make a distinctive tone when it identified a hard object. The intensity of the tone and clarity of the green pear display alerted the operator to the presence of submerged objects such as mines. One veteran sonarman stated, “It sounded like a chamber of horrors, it howled something awful.” 24 The laboratory at San Diego named the bell tones “Hell’s Bells,” and the name stuck when FMS was introduced. 25 The initial range of the signal from FMS was limited to a few hundred yards, but the value was evident if all the kinks could be worked out.

Lockwood was impressed enough to begin the bureaucratic maneuvering to ensure that the first available FMS sets would be assigned to his command for testing. The first tests occurred about a year later, with SS-411, Spadefish , under the command of Commander Gordon “Coach” Underwood, with a deck-mounted FMS. Spadefish tested the device off San Diego against dummy minefields before reporting to Pearl Harbor in June 1944. Lockwood immediately interrogated Underwood on his impressions. He went aboard Spadefish and directly observed the new sonar, as Underwood’s crew put it through its paces. These trials convinced him that the doors into the Sea of Japan could be unlocked and that “FM Sonar was the magic key that could perform the marvel.” 26

Lockwood was satisfied enough to brief his boss, Admiral Chester Nimitz at Pacific Fleet, who approved efforts to gain additional FMS sets to accelerate their introduction into the Pacific theater. 27 At an arranged meeting during the CNO’s visit to Hawaii in July 1944, Lockwood gained King’s support for shifting FMS production of 12 sets from minesweepers to his command.

The gears of the Navy’s acquisition bureaus ground slowly but surely, and Lockwood got one dozen sonar sets for his force. He continued to invest his personal time and attention in the introduction of sonar and the development of tactics with a series of experiments out of Pearl Harbor. When he could, Lockwood himself observed the experiments. Ultimately, the testing evolved, with one submarine, Tinosa , taking FMS on a combat patrol. Tinosa , skippered by Commander Richard Latham, patrolled an area off Formosa and the East China Sea where mines were likely to be found. 28 Latham identified 200 mines at range and gave an enthusiastic report on FMS. Other boats testing the system, however, reported discouraging failure rates. Lockwood’s faith in sonar was strained by uneven quality largely due to faulty vacuum tubes. The admiral stated that sonar showed “streaks of mulish obstinacy.” 29

But as new boats came in with keel-mounted and increasingly effective FMS sets, Lockwood’s confidence grew. He sketched out an operation to penetrate the Sea of Japan to the CNO in December 1944. By striking into the heart of the last sinews of communications and logistics between the Asian mainland and Japan, Lockwood hoped to sever those lines of communication and make Tokyo realize that the war was irrevocably lost. Arguably, the Japanese would be forced to dilute their defenses on the Pacific Ocean side of their country, which was the major target for U.S. air and sea operations. Cutting off Japanese sources of rice, construction materials, ore, and reinforcements from Asia could also materially aid the U.S. war effort. The mission was approved the same month and kicked off the formal planning for a complex raid.

Operational Concept

The raid employed a novel approach. Rather than have a pack of attack boats concentrate on a single target set like a large convoy, the concept of operations had nine boats entering the Sea of Japan and then distributing themselves for simultaneous attacks at a set time. This is essentially the opposite of the German navy wolf pack tactics, which patrolled widely and then aggregated upon slow-moving convoys.

“I want to send all the boats we can muster in at the same time,” Lockwood summarized years later, “hit the [Japanese] like a ton of bricks, and pull out before they can properly organize their opposition.” 30 This concept would overwhelm the Japanese navy and dilute its counter-responses. Lockwood sought to maximize surprise and destruction with a sudden set of attacks, which would hopefully reduce the ability of the Japanese to quickly react effectively.

The plan was devised by Captain William “Barney” Sieglaff, a veteran submariner with 15 vessels sunk to his credit. Somewhat comically, the operational plan was titled Operation Barney in honor of its initial designer. The plan was framed around three major events:

- transit through the mine-strewn straits (Fox Day, June 4)

- initial attack time (Mike Day, June 9)

- exit (Sonar Day, June 24).

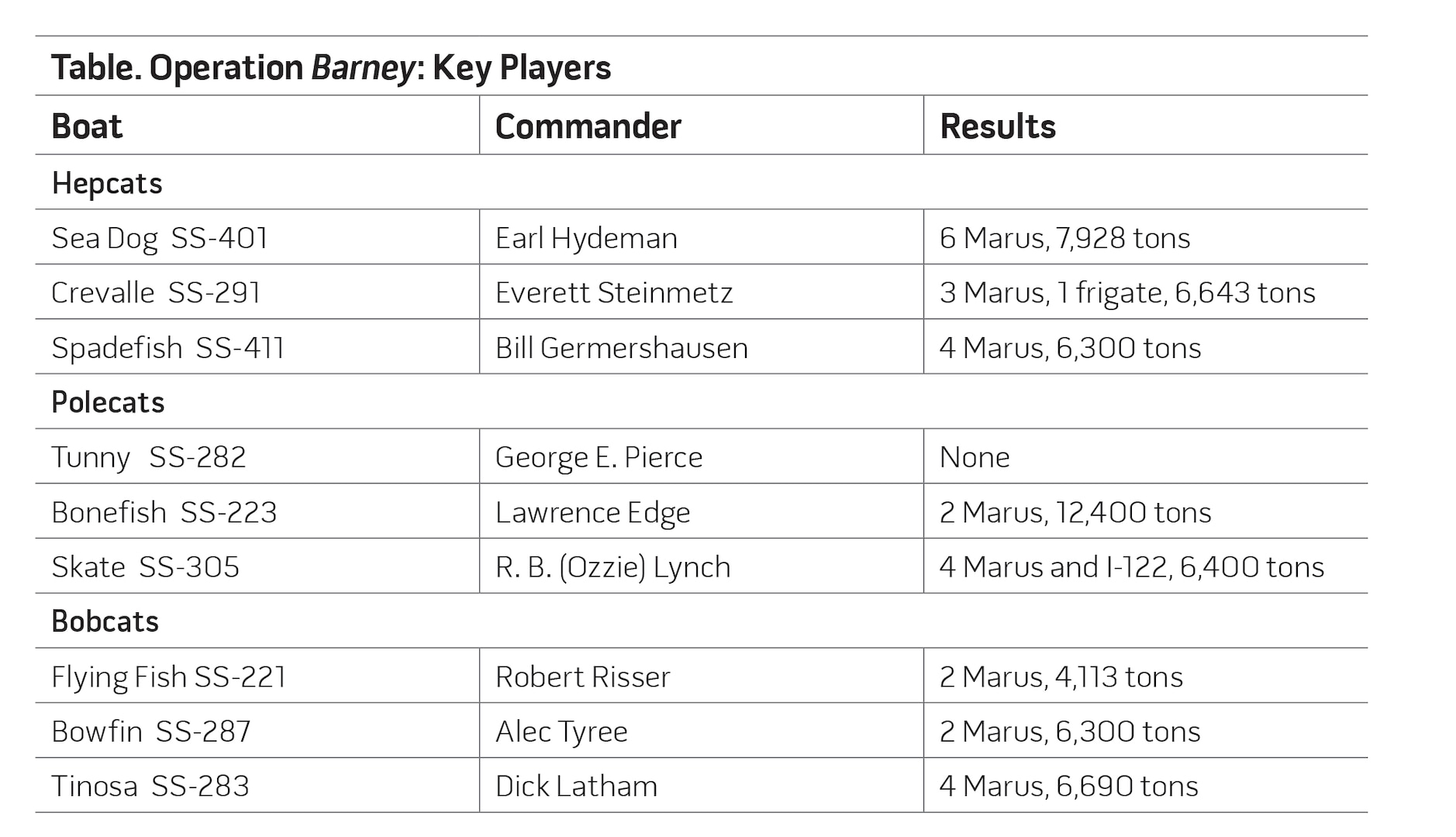

The entire task force of nine boats would sail from Guam. It was titled the “Hellcats” and divided into three smaller groups under the command of the most senior boat captain. The three groups were called the Hepcats, Polecats, and the Bobcats (see map).

As part of the plan, the Hepcats would sail on May 27, followed by the other groups over the next 2 days. This plan allowed 3 days for the treacherous penetration of the straits, a precarious 16-hour event for each pack. The passage through the mined straits was further complicated by the steady Kuroshio current that would push them along. The intelligence gained from prior patrols identified four belts of mines, 50 to 75 yards apart. Once that barrier was pierced, the task force would maneuver to its attack positions. The task force was given 2 weeks to attack military and commercial shipping before regrouping and exiting via La P é rouse Strait on Sonar Day.

The three packs carefully made their way through the minefields, with only a few daunting incidents. Without FMS, Fox Day could have been a finale for any of the Hellcats. The Hepcats steamed north into the northeastern part of the Sea of Japan with assigned target areas off Hokkaido. Crevalle hunted off Suneko Saki, and Spadefish stalked near Otaru, at Ishikari Bay. Sea Dog struck first on June 9 against three cargo ships, but a hurried attack failed, and in escaping Commander Earl Hydeman dived too fast and too deep. Sea Dog ran aground in a soft seabed and had to slowly back off minus a few sensors. Despite numerous mechanical casualties, Hydeman sunk six small merchants in shallow water. Spadefish was almost as successful, eliminating four ships and 6,000 tons. Crevalle took on three targets the first 3 days and put them to the bottom of the sea with only five torpedoes. Over the next week, 5 different attacks and 11 “fish” produced no hits. Torpedo failures still plagued the crews. Then on June 22, Commander Everett Steinmetz’s firing team successfully attacked the frigate Kasado. It was later recovered from the bay but was never operational again. 31

The east coast of the Korean Peninsula was assigned to the Bobcats. They had a more difficult passage through the treacherous minefields. At one point, the crew described hearing “the squeal of steel on steel” working down port side of Tinosa ; a mine cable was passing alongside the length of the boat, sounding like fingernails across a blackboard for what seemed like several minutes. 32 Fortunately, they did not activate any mines . After successfully navigating the narrow Tsushima Strait, Commander Richard Latham, commanding Tinosa , moved to his sector off the port of Bukuko Ko. With numerous visible targets, he could not contain himself. He launched an attack at exactly 1503 hours, well before sunset on Mike Day, and sunk an unsuspecting freighter. 33 Latham’s crew successfully bagged three more during the operation. Flying Fish and Bowfin proceeded to stand off Seishin and Rahshin harbors until they could begin their attacks.

The Polecats were assigned to cover the west coast of the major island of Honshu. Tunny staked out Kyoga Misaki outside the bay of Wakasa Wan. The skipper, Commander George Pierce, found few targets off the coastline, despite his efforts to lean into shallow water. Skate fared better. On June 10, it ambushed a submarine, I-122 , running on the surface and sent it to the bottom. Later, R.B. Lynch’s team on Skate attacked and claimed four cargo ships. Three were sunk with a spread of six torpedoes Lynch fired from long distance at several cargo vessels hiding in a cove on the west coast of Honshu.

Bonefish was initially ordered to Toyama Bay but found no targets. Subsequently, the captain, Commander Lawrence Edge, requested to move to a more productive area. Edge successfully attacked and sunk the 6,892-ton cargo vessel Ojikasan Maru on June 13, 1945. On June 16, 1945, he kept a rendezvous with his Polecat leader, Commander Pierce, and informed him of this sinking. He also asked for permission to conduct a submerged daylight patrol back in Toyoma Wan, which had a depth of 600 fathoms in the mid-part of western Honshu. Bonefish successfully attacked and sank a ship, the 5,488-ton cargo vessel Konzan Maru , in Toyama Wan on June 18. However, Japanese records show that the next day a Japanese frigate and several corvettes depth-charged a submarine in Toyama Wan, and extensive debris and an oil slick were recorded by the Japanese. There were no more reports from Commander Edge, and Bonefish did not join the rest of the task force at their rendezvous.

After sunset on June 24, Hydeman led the remaining eight boats out of La P é rouse Strait with a high-speed, night-surface dash. They passed through the strait and its strong current into safety. Tunny stayed for a few days, hoping that Bonefish had been forced to delay its exit due to an engineering problem. The rest of the task force sped home. They arrived July 4 to a hero’s welcome at Pearl Harbor. The celebrations were restrained once Bonefish was declared as lost.

Overall, two Japanese naval craft, 28 modest-sized cargo ships, and numerous small craft were sent to the deep bottom of the sea—for a total of 65,000 tons. The operational results of each boat in the operation are detailed in the table.

Assessing this mission’s results is difficult at the operational and strategic levels. The raid did overwhelm Japan’s defense. Regrettably, there were few major targets, and even fewer once the Japanese knew their sanctuary had been compromised. The loss of Bonefish and her gallant crew was a calculated risk that offset the gains from the attack. This loss was a gut punch to the small submarine force, but the pending invasion of Japan in Operation Downfall posed far more horrific costs. 34 Lockwood hoped to further isolate Japan, materially and psychologically, with this daring raid. Ultimately, the indirect impact on Japanese strategic calculations and morale are unknown, but Lockwood concluded the operation was worth the risk. 35

Professor I.B. Holley warns that “it is folly to expect the record of the past to deliver us neat little packages called ‘lessons of history’ with exacting prescriptive detail. Instead of tidy answers that alleviate inquiry, we explore history to stimulate our thinking and to get better questions to probe the present with.” 36 With this caution in mind, some insights can be drawn from Operation Barney . These insights include the value of the enduring necessity of rapid wartime learning, the role of leaders and culture that embrace openness, and the importance of technological literacy.

Operational Learning and Adaptation. The Navy’s learning system before and during World War II is worthy of study and emulation. The ultimate weapon throughout the Pacific campaign was the Navy’s learning culture and mechanisms. The velocity of learning across the Pacific force contributed to a growing overmatch between the respective navies. 37 The Navy systemically gathered operational experience or lessons learned from the fleet in patrol reports and from tests and trials that Lockwood conducted out of Perth, Pearl Harbor, and Guam. 38 As one recent historical account of the early stages of naval warfare in the Pacific notes:

If the navy did one thing right after the debacle of December 7, it was to become collectively obsessed with learning, and improving. Each new encounter with the enemy was mined for all the wisdom and insights it had to offer. Every after-action report included a section of analysis and recommendations, and those nuggets of hard-won knowledge were absorbed into future command decisions, doctrine, planning, and training throughout the Service. 39

This meant that the Navy’s tactical development was thorough and grounded in a realistic understanding of the battlespace, and it was generated from the middle out by operators. 40 In an excellent example of double-loop learning, where operator input makes it all the way to headquarters and is recycled out to the fleet, the SUBFORPAC commander identified key operational challenges and used a campaign of deliberate experimentation by operational commanders to determine the best combination of organizational, tactical, and technological change to resolve its challenges. 41 The concurrent development of both “American wolf pack” tactics and sonar reflects this approach. Such an approach reinforces key insights of wartime and interwar innovation. 42 Lockwood also promoted “horizontal learning” between boats in order to accelerate learning and increase operational effectiveness. 43 The Navy fostered this technique by distributing war patrol reports across the fleet and by having formal endorsements of the conduct of attacks and proposed tactical fixes after each patrol. Historians find both formal and informal mechanisms are necessary to distribute new ways of fighting.

Leadership and Technological Literacy . We operate today in a period often described as an era of disruptive change. Lasers, rail guns, artificial intelligence, and hypervelocity missiles generate new opportunities and threats to the fleet. In World War II, our submarine force operated in a similar era, with radar, tactical data computers, electric homing torpedoes, and various sonar options emerging in a compressed time. Fortunately, our leaders were well trained; they not only knew their seamanship, but they were also well educated in naval engineering. As Wayne Hughes notes, the Navy’s best tacticians, from admirals William Sims to Bradley Fiske to Arleigh Burke, knew the benefits and limits of current and prospective technology. 44 Current Navy doctrine notes that “tactics and technology are two sides of the same coin” and enjoins leaders to “inculcate a culture of lifelong learning to foster innovative thinking, adaptability, [and] technical expertise.” 45 Like Lockwood, today’s leaders must be tech-savvy and understand the potential of emerging technology to be able to adapt it in new ways to solve future problems, even problems for which that technology may not have been originally designed.

With his open learning approach, Lockwood is an outstanding example of a leader of innovation. Current research suggests that openness is invaluable as a leadership attribute. This is manifested in a strong intellectual curiosity, creativity, and a degree of comfort with novelty and variety. Leaders high in openness search for a range of relevant and conflicting perspectives and often spot opportunity earlier than others. 46 Military historians also find this style of leadership as a key variable to promote the requisite critical thinking and open debate needed to assess and implement innovation. 47

Changes in the character of war demand literacy in the implications of ongoing technologies. This is a new objective for our PME institutions, one that should be reflected across the entire system. As noted by Australian Major General Mick Ryan in the pages of this journal, “Over the coming years, at almost every rank level, military personnel will require basic literacy in a spectrum of new and disruptive technologies.” 48 Providing this degree of basic literacy to mid-career officers is needed but poses challenges to the Services with near-term readiness demands. Yet the study of innovation and adaptation should be a core component of senior leader education, in addition to introductions to military-relevant emerging technologies. 49 Graduates of top-level schools are going to be leaders in innovation in this era of disruptive change, and their education must reflect that.

The key leaders in this case were also barrier busters and champions for change, willing to overcome slow-moving bureaucrats when needed. Most relevant to today’s strategic competition, Lockwood recognized the opportunity presented by the technology as it matured and fought aggressively to get this technology to his operators to exploit it. Not content with isolated development by technicians, he got the San Diego scientists to bring their expertise to Hawaii and other forward bases to merge development and tactics to maximize learning, while also training his people to maintain the new equipment.

Joint Warfighting Culture . This case study does not indicate much appreciation for joint operations. The operation was planned solely as a Navy submarine operation from beginning to end. It could have been a much larger joint operation applying a more integrated approach that would have enhanced the effectiveness of the offensive mission and reduced some of the operational risk. Today, such a mission would be designed as a joint operation, with special operations forces helping distract the adversary, perhaps by attacking a land-based radar site, with U.S. Cyber Command disorienting the Japanese command and control systems, and with the Air Force conducting strikes on Japanese airfields to negate maritime reconnaissance flights over the area being launched. This was a high-risk operation that could have benefited from a joint combined arms approach. 50

But 75 years ago, the Services were not always ready to operate as a joint team. Nor was America prepared to operate jointly later in Korea or Vietnam. 51 In the future, globally integrated operations across domains and geographical boundaries are expected to be the norm, mandating increased attention to joint and combined opportunities. Fortunately, we have a much stronger degree of jointness today at the operational level. Yet joint acculturation and education are perishable competitive advantages today and should not be taken for granted. 52

Admiral Lockwood’s vision about Frequency Modulated Sonar and his careful nurturing of the technology offer a valuable case study for today’s joint warfighting community in a looming era of potentially disruptive change. The concurrent adaptation of new technology, operational concepts, and organizational change was evident in the submarine force. Operation Barney offers a periscope view into the Navy’s learning system, from which we can draw some probing insights. Our current conception of operational competence must extend to learning how to innovate in contact with the enemy and deal with new technologies. “Learning under fire” can be a force multiplier if commanders are well educated in historically informed patterns of innovation and adaptation and develop a modest degree of technical literacy.

Overall, this operation exemplifies adapting to the always evolving character of warfare and highlights the application of innovation in combat leadership by senior leaders. It exemplifies how creative solutions to tough operational challenges in the Pacific were pursued and continuous adaptation obtained in a contested environment. We can all learn much from Vice Admiral Lockwood’s leadership and the adaptive learning and valor of the Hellcats. JFQ

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge extended assistance from Dr. Bryon Greenwald, Colonel Pat Garrett, USMC (Ret.), and an anonymous peer reviewer in preparing th is article.

1 On emerging technologies and their likely implications, see T.X. Hammes, Deglobalization and International Security (Amherst, NY: Cambria, 2019).

2 Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, January 18, 2018), 7.

3 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction (CJCSI) 3030.01, Implementing Joint Force Development and Design (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, December 3, 2019).

4 Developing Today’s Joint Officers for Tomorrow’s Ways of War: The Joint Chiefs of Staff Vision and Guidance for Professional Military Education and Talent Management (Washington, DC: Joint Staff, May 1, 2020), available at < https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/education/jcs_pme_tm_vision.pdf?ver=2020-05-15-103733-103 >.

5 CJCSI 1800.01F, Officer Professional Military Education Policy (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, May 15, 2020). The Officer Professional Military Education Policy defines a desired leadership attribute for officers as being prepared to “respond to surprise and uncertainty” and “recognize change and lead transitions.”

6 David Barno and Nora Bensahel, Adaptation Under Fire: How Militaries Change in Wartime (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).

7 On War Plan Orange, see Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange : The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991). On aviation capability developments, see Geoffrey Till, “Adopting the Carrier,” in Military Innovation in the Interwar Period , ed. Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett (New York : Cambridge University Press, 1996), 191–225.

8 Trent Hone, Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018).

9 See Joel Holwitt, “Unrestricted Submarine Victory: The U.S. Submarine Campaign Against Japan,” in Commerce Raiding: Historical Case Studies, 1755–2009 , Newport Papers 40, ed. Bruce A. Elleman and S.C.M. Paine (Newport, RI: Naval War College, October 2013).

10 For a more detailed overview of submarine adaptation, see Mick Ryan, “The U.S. Submarine Campaign in the Pacific, 1941–45,” Australian Defence Journal , no. 90 (March/April 2013), 62–75; Francis G. Hoffman, “Adapt, Innovate, and Adapt Some More,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 140, no. 3 (March 2014), 30–35.

11 I.J. Galantin, Take Her Deep! A Submarine Against Japan in World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2007), 29.

13 John G. Mansfield, Jr., Cruisers for Breakfast: War Patrols of the U.S.S. Darter and U.S.S. Dace (Tacoma, WA: Media Center, 1997), 221.

14 Charles A. Lockwood, Sink ’Em All: Submarine Warfare in the Pacific (New York: Dutton, 1951), 33.

15 Paul Kennedy, The Engineers of Victory: The Problem Solvers Who Turned the Tide in the Second World War (New York: Random House, 2013).

16 Theodore Roscoe, United States Submarine Operations in World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1949), 225.

17 Brayton Harris, Admiral Nimitz: The Commander of the Pacific Ocean Theater (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2012).

18 On prewar planning, see Joel Ira Holwitt, “Execute Against Japan”: Freedom-of-the-Seas, the U.S. Navy, Fleet Submarines, and the U.S. Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Warfare (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008).

19 On the early stages, see Clay Blair, Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan , vol. 1 (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975).

20 The boats out of Brisbane also developed cooperative methods. See Blair, Silent Victory , 453–456. Also see Frank G. Hoffman, “The American Wolf Packs: A Case Study in Wartime Adaptation,” Joint Force Quarterly 82 (2 nd Quarter 2016), 34–38.

21 Wahoo was lost in an early attempt at penetrating the Sea of Japan. For more on Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton and the intrepid crew of Wahoo , see Richard Kane, Wahoo: The Patrols of America’s Most Famous World War II Submarine (Novato, CA: Presidio, 1996) .

22 Roscoe, United States Submarine Operations in World War II , 432–433; Clay Blair, Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan , vol. 2 (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975), 791–799.

23 Charles A. Lockwood and Hans C. Adamson, Hellcats of the Sea: Operation Barney and the Mission to the Sea of Japan (Los Angeles: Bowsprit, 2018), 20.

24 Cited in Steven Trent Smith, “Payback: Nine American Subs Avenge a Legend’s Death,” History.net , available at < https://www.historynet.com/uss-wahoo-vengeance.htm >.

25 Peter Sasgen, Hellcats: The Epic Story of World War II’s Most Daring Submarine Raid (New York: Caliber, 2010), 74–75.

26 Lockwood and Adamson, Hellcats of the Sea , 22.

27 Western Electric was under contract to produce these initial sets for the Navy’s minesweepers.

28 Commander, USS Tinosa , 8 th War Patrol Report, dated September 14, 1944. The patrol reports are available at < https://www.hnsa.org/manuals-documents/submarine-war-patrol-reports/ >.

29 Lockwood and Adamson, Hellcats of the Sea , 41. These frustrations were based on the commander, USS Spadefish , Fourth War Patrol Report, April 14, 1945, which included a special mission report on its efforts to identify mines in the Tsushima Strait with poor performance from Frequency Modulated Sonar.

30 Lockwood and Adamson, Hellcats of the Sea , 53.

31 Commander, USS Crevalle , War Patrol Report #7, July 5, 1945.

32 Sasgen, Hellcats , 185.

33 Lockwood and Adamson make note of this in Hellcats of the Sea , 165.

34 Operation Downfall was the U.S. plan for invading Japan’s main islands, and it was projected to be costly in terms of casualties for both sides. See Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (New York: Penguin, 2001).

35 See National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Box 358, “Operation Barney,” in Submarine Bulletin 2, no. 3 (September 1945), 10–16.

36 I.B. Holley, Jr., Technology and Military Doctrine: Essays on a Challenging Relationship (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press, 2004), 113.

37 Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully, Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2007), 407.

38 Ian Toll, Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942 (New York: Norton, 2011), 375.

39 Ibid., 375.

40 Scott H. Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 3 (March 2018), 22–26.

41 Single- and double-loop learning cycles are central to my research in military adaption. See Frank G. Hoffman, Mars Adapting: Military Change During War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2021).

42 Williamson Murray, Military Adaptation in War: With Fear of Change (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011); see also Stephen Peter Rosen, Winning the Next War: Innovation and the Modern Military (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996), 22–38.

43 Robert Thomas Foley, “A Case Study in Horizontal Military Innovation: The German Army, 1916–1918,” Journal of Strategic Studies 35, no. 6 (2012), 1–29; Sergio Catignani, “Coping with Knowledge: Organizational Learning in the British Army,” Journal of Strategic Studies 37, no. 1 (2013), 30–64.

44 Wayne Hughes and Robert Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations , 3 rd ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 33–34. On Burke, see David Alan Rosenberg, “Admiral Arleigh A. Burke,” in The U.S. Navy: A Complete History , ed. M. Hill Goodspeed (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Foundation, 2003).

45 Naval Doctrine Publication 1, Naval Warfare (Washington, DC: Headquarters Department of the Navy, April 2020), 55.

46 Stephen J. Gerras and Leonard Wong, Changing Minds in the Army: Why It Is So Difficult and What to Do About It (Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, October 2013), 8.

47 Williamson Murray, “Innovation, Past and Future,” in Innovation in the Interwar Period , 311.

48 Mick Ryan, “The Intellectual Edge: A Competitive Advantage for Future Warfighting and Strategic Competition,” Joint Force Quarterly 96 (1 st Quarter 2020), 9.

49 A key insight from the Joint Chiefs professional military education vision and echoed in Barno and Bensahel, Adaptation Under Fire.

50 Description of the National Military Strategy 2018 (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, 2019), 2, available at < https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Publications/UNCLASS_2018_National_Military_Strategy_Description.pdf >.

51 This is particularly true for the Pacific theater in World War II given the divided command structures and strategies of Douglas MacArthur and Chester Nimitz. On Korea, see Conrad C. Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 1950–1953 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 23–55; Price Bingham, “The U.S. Air Force and Army in Korea: How Army Decisions Limited Airpower Effectiveness,” Joint Force Quarterly 91 (4 th Quarter 2018), 47–59. However, one of the largest operations in warfare, Operation Overlord into Normandy, reveals good inter-Service relations, as did the air-ground coordination between the U.S. Third Army and Major General Elwood R. “Pete” Quesada’s XIX Tactical Air Command during the drive into Germany. See David N. Spires, Air Power for Patton’s Army: The XIX Tactical Air Command in the Second World War (Washington, DC: U.S. Air Force History and Museum Program, 2002).

52 Charles Davis and Kristian E. Smith, “The Psychology of Jointness,” Joint Force Quarterly 98 (3 rd Quarter 2020), 68–73.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Catalysts of Military Innovation: A Case Study of Defense Biometrics

Military technology innovation has always been a central component of U.S. strategic advantage; however, the precise conditions that enable successful innovation remain a matter of some debate. The recent introduction of biometrics onto the battlefield offers a useful case study for examining military innovation and identifying specific factors that enabled DoD to rapidly develop and field a new technology in response to urgent operational requirements. This paper considers how doctrinal design and war-fighting strategies became important catalysts for this process, but also how bureaucratic shortfalls and weak acquisition strategies ultimately limited U.S. forces from realizing the full potential of these technologies. This case study proposes that effective military innovation can only occur by means of an integrated approach that takes into account the interdependent elements of technology, acquisition planning, doctrinal design and war-fighting strategies. It offers some general conclusions on the conditions that foster a fertile environment for military innovation and identifies lessons learned for future efforts at introducing new technologies into the field.

Related Papers

Glenn Voelz

The attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11) and two extended counterinsurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan presented the United States with unconventional adversaries for which it was largely unprepared. These opponents did not fight as doctrinal formations or within clearly defined operational boundaries. Rather, they were organized as loose networks, comprised of individuals often indistinguishable from surrounding populations. Without uniforms and flags, the task of identifying and target- ing these entities presented an unprecedented operational challenge for which traditional warfighting approaches were largely unsuited. In response, the U.S. military and the broader national security apparatus embarked upon a decade of doctrinal, technical, and organizational innovations premised on the idea that individual combatants had become a salient national security concern and a legitimate object of military targeting. Within this new operational paradigm, the identification, screening, and targeting of individual combatants and their associated networks became the central focus for a new mode of state warfare—iWar. Over the last decade, this approach to warfighting has emphasized the operational tasks of identifying key actors on the battlefield, penetrating their networks, and isolating them from larger populations, and, when necessary, conducting kill/capture operations against high-value insurgent and terrorist targets. This strategy required the adoption of new doctrinal concepts deeply influenced by network analysis theory and the use of identity-base targeting. These methods emphasized analytical approaches based upon the disaggregation of battlefield threats down to the lowest possible component—often the individual combatant—and introduced identity as a critical signature of military targeting. Along with new doctrinal concepts, the conflicts of the last decade also generated a range of technology innovations specifically designed for the informational demands of identity-based operations. These included biometrics, expeditionary forensics, and DNA analysis, to name a few. However, the tools and methods of iWar were by no means limited to use on foreign battlefields. On the domestic front, similar technologies have been used to construct an expansive identity-based screening program that has kept borders, transportation networks, and American cities remarkably safe since 9/11. This achievement depended upon the accumulation of a dense informational base layer designed to support identity management, net- work analysis, and data sharing across the entire U.S. national security apparatus. The challenges presented by post-9/11 adversaries were also the catalyst for a major bureaucratic transformation that has gradually eroded many of the traditional lines separating military operations, foreign intelligence activities, and domestic security functions. These changes reflect a new strategic calculus that has placed the threat from non-state actors and individual combatants on equal footing with adversarial states in the crafting of U.S. national security policy and as a driver of military innovation. This monograph examines the course of this doctrinal and technical transformation over the last decade and con- siders the implications for the future of U.S. national security strategy and military conflict in the age of iWar.

Since 9-11, the United States has embarked on a decade of doctrinal and technical innovations focused on defeating net- works and individual combatants rather than formations. This article examines this evolving model of individualized warfare within the context of current debates over the appropriate role of military landpower in an age dominated by persistent threats from non-state actors and unconventional adversaries.

TECHNICAL EXPLOITATION IN THE GRAY ZONE: EMPOWERING NATO SOF FOR STRATEGIC EFFECT

chace falgout

Russian hybrid warfare has become the principle threat to NATO over the last decade. From the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, Russia has exercised its will across Europe; inciting tensions while limiting its activities to below the Article 5 threshold, an armed attack on one is an attack on all. The balance of power favors those who embrace inevitable technological advancement while enduring the discomfort presented by its evolution. Hybrid warfare creates complex problems requiring an unconventional mindset and while NATO Special Operations (NSOF) inherently possess this trait and are rightly-suited to contribute to NATO’s counter-hybrid strategy, little research examines how NSOF tactical activities can deliver strategic effects through the exploitation of technology. This capstone collates expansive research on Russian gray zone activities of hybrid warfare, NATO’s cyber deterrence and counter hybrid threat strategy, and NSOF’s doctrine and capabilities, to present a focused area for capability enhancement of Special Operations Forces (SOF). NSOF’s embrace of Technical Exploitation Operations (TEO) facilitated evidence-based operations in Afghanistan with great success and subsequently led to the establishment of TEO programs in Alliance nations. However, sub-disciplines like biometrics have received preference over data-rich sources like digital media, cellular phones, and other more complex exploitation forms. An appreciation of the value of digital artifacts and their ability to illuminate hybrid warfare and gray zone activities, intent, and attribution is necessary to accurately position NSOF in NATO’s cybersecurity and hybrid warfare framework. Keywords: Cybersecurity, Dr. Christopher Riddell, hybrid warfare, gray zone activities, drone forensics.

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space

John Morrissey

This paper examines the recent broadening of the US military’s overseas mission into what it calls ‘full spectrum operations’ and critiques how it is being enabled by what I term ‘full spectrum law’. The paper explores the important doctrinal shifts that took place in the US military from 2005, when it declared for the first time a commitment to ‘stability operations’ as a military responsibility equal in status to offense and deterrence. This, I argue, has reinforced an already dominant US national security discourse in which military and economic security interests are firmly bound. In particular, it has given the US military a broader role in the ‘correction’ of underdevelopment and the securitization of the legal and economic modalities necessary for a functioning neoliberal global economy. The paper reflects on the US military’s blending of security and development concerns and reveals how its legal framing of stability operations draws upon a ‘notional legal spectrum’ that allows for the securitization of the most broadly understood ‘instability’ and sanctions the interminable use of the US military in global interventions in an era ubiquitously cited as one of ‘persistent conflict’.

Routledge Handbook of Defence Studies, Ed., David Galbreath & John Deni

Manabrata Guha

This chapter highlights some of the problems and prospects of dealing with the prediction of future war. It summarizes a number of strategic-military trends that can be said to be co-constituting the contours of emergent forms of warfare (and of the global strategic commons) and maps them over and across selected areas of interest within the Information and Communication sciences and technologies domain. In closing, a few observations regarding the importance and implications of considering the question regarding future war in the field of Defense and War Studies are presented.

Nathaniel L. Moir, Ph.D.

Dennis Gormley

Sarah Soliman , Glenn Voelz

The cyber domain has become “key terrain” of irregular warfare with state and non-state actors leveraging social media and other digital tools for command and control, intelligence gathering, training, recruiting and propaganda. DoD’s cyber strategy highlighted the urgent need for improved cyber situational awareness to reduce anonymity in cyberspace. This requires new technologies, doctrine and analytical approaches for identifying and targeting adversaries operating in a digital landscape. This paper examines identity-based targeting approaches developed during recent conflicts as a possible stating point for this effort.

Whitney Grespin

Book review of "Sudden Justice: America's Secret Drone Wars" published by the U.S. Army War College's Strategic Studies Institute in the journal Parameters Spring 2017

RELATED PAPERS

william flavin

Finding the Balance

William Flavin

Christopher Kinsey , Mark Erbel

Mohamed Ali

Donald Travis

tanveer nizamani

AMERICA'S

Joint Force Quarterly, Vol. 71 (2013), 79-83.

Eric Jardine

Michael Davies

Frank Hoffman

International Affairs

Theo Farrell

Nina Kollars

Christopher Sims

Fallacy of 4GW

Tony Piscitelli

Jennifer Rachels

Jonathan M Acuff

Alfred connable

Emico Eruwa

Defense & Security Analysis

James Johnson

Christine A MacNulty, FRSA

Adam Taggett

Warren Lerner

Armor Magazine

Matthew Snow

Cultural Heritage in the Crosshairs: Protecting Cultural Property during Conflict

Cheryl White

Sicherheit und Frieden (S+F) / Security and Peace

David H Ucko

Stano Matějka

Tommaso De Zan

Lydia Wilson , Hammad Sheikh , Randy Kluver , J C , Gina Ligon

Lukas Milevski

Charles Hiter

Michael Vlahos

Kobi Michael , Eyal Ben-Ari

PsycEXTRA Dataset

Richard Darilek

Mark Tempestilli

Leticia Colimil

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Innovation and the Promise of Military Power

Military innovation and its risks, a theory of harmful innovation, the puzzle of british performance in the desert war, 1941–1942, british innovation in armored warfare, 1919–1939, variation in british army effectiveness in the desert war, 1941–1942, evaluating alternative explanations of harmful innovation, dangerous changes: when military innovation harms combat effectiveness.

Assistant Professor at the Strategic and Operational Research Department at the U.S. Naval War College.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Kendrick Kuo; Dangerous Changes: When Military Innovation Harms Combat Effectiveness. International Security 2022; 47 (2): 48–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00446

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Prevailing wisdom suggests that innovation dramatically enhances the effectiveness of a state's armed forces. But self-defeating innovation is more likely to occur when a military service's growing security commitments outstrip shrinking resources. This wide commitment-resource gap pressures the service to make desperate gambles on new capabilities to meet overly ambitious goals while cannibalizing traditional capabilities before beliefs about the effectiveness of new ones are justified. Doing so increases the chances that when wartime comes, the service will discover that the new capability cannot alone accomplish assigned missions, and that neglecting traditional capabilities produces vulnerabilities that the enemy can exploit. To probe this argument's causal logic, a case study examines British armor innovation in the interwar period and its impact on the British Army's poor performance in the North African campaign during World War II. The findings suggest that placing big bets on new capabilities comes with significant risks because what is lost in an innovation process may be as important as what is created. The perils of innovation deserve attention, not just its promises.

Conventional wisdom suggests that innovation consistently improves military power. Militaries that oppose it invite defeat, but those that innovate secure victory. Innovation is considered a sign of organizational health because the ever-changing character of war constantly threatens to render existing capabilities obsolete. Conversely, misfortune comes to those who allow the march of historical change to overtake them. The notion that innovation and better military performance go hand in hand is thus intuitive. It is also wrong.

In popular imagination, for example, the German blitzkrieg was a revolutionary innovation in World War II that restored the possibility of decisive victory, which had eluded European armies since the Franco-Prussian War. What is less known is that the British also innovated in armored warfare yet performed poorly on the battlefield. While the German Army mechanized its combined-arms tactics developed at the end of World War I, the British deployed armored brigades comprised almost entirely of tanks and expected them to fight with virtually no help from supporting arms.

What is puzzling about this example is not the presence or absence of innovation—both armies innovated new forms of armored warfare—but instead why some innovations enhance combat effectiveness while other innovations do not. The idea that innovation is a gamble is not novel, but too often analysts focus on only beneficial changes. They overlook harmful innovation in military organizations, implying that the gamble is always worth making. This article seeks to restore the atmosphere of risk inherent to innovation and explain why its perils deserve as much attention as its promises. To do so, I develop a theoretical framework that relates patterns of peacetime innovation to its impact on wartime effectiveness—the ability of a military service to accomplish its assigned missions at acceptable cost. 1

My central claim is that innovation is more likely to weaken a service's effectiveness when growing security commitments outstrip shrinking resources. This wide commitment-resource gap exerts pressures to innovate in ways that cannibalize traditional capabilities before beliefs about the effectiveness of new ones are justified. When wartime comes, not only has the service lost proficiency in those older capabilities, but the new capability underdelivers, thereby creating vulnerabilities for the enemy to exploit.

Studying harmful innovation is crucial for both scholarship and contemporary policy challenges. Scholars study military innovation primarily because of its promise to improve effectiveness. But whether peacetime innovation increases military power is usually an assumed relationship rather than a studied one. There is a bias in case selection: scholars almost exclusively study power-enhancing innovation and ask why it occurred. Explaining the adoption of new ways of war, however, says little about whether the change is beneficial or harmful.

For defense policy, this article cautions against overly relying on military innovation to bridge wide commitment-resource gaps. The United States is in an era of military modernization in which military and civilian leaders must make important decisions about future platforms and systems that will shape U.S. military power for a long time. At the same time, the armed services operate with relatively constrained resources compared with their expansive commitments. The confluence of these trends creates pressure to make big bets on new capabilities and take risks in shedding traditional ones. My theory and findings suggest, however, that it is precisely this type of environment that encourages miscalculation.

This article proceeds in eight sections. First, I review the existing literature on military innovation, highlighting the curious absence of studies that systematically examine the downside risks of innovation. Next, I define military innovation as used in this article. The third section proposes a theory of harmful military innovation. In the fourth section, I introduce the puzzling case of British armor innovation after World War I and the British Army's subsequent combat ineffectiveness, and I discuss the research design. Sections five and six illustrate the theory, tracing British armor innovation in the interwar period and performance in the Desert War during World War II. I then evaluate alternative explanations in section seven, before concluding with avenues for future research and implications for scholarship and defense policy.

In popular discourse, the word “innovation” connotes desirable progress. The same is true in research on international relations and military innovation. Theories of international relations assume that innovation enhances a state's power in the international system by changing the unit cost of military power such that a given supply of resources is converted more effi- ciently into wartime effectiveness. Robert Gilpin argues that military innovation gives a “particular society a monopoly of superior armament or technique and dramatically decreases the cost of extending the area of domination.” 2 John Mearsheimer similarly observes that great powers “prize innovation” because it offers “new ways to gain advantage over opponents.” 3 Assuming then that innovation bestows a competitive edge, “contending states imitate the military innovations contrived by the country of greatest capability and ingenuity.” 4

Theories of military innovation reflect this optimistic view. In his influential review of the literature, Adam Grissom identifies a “tacit definition of military innovation that is, approximately, ‘a change in operational praxis that produces a significant increase in military effectiveness’ as measured by battlefield results.” He finds that “only reforms that produce greater military effectiveness are studied as innovations, and few would consider studying counterproductive policies as innovations.” 5 Some researchers have made Grissom's tacit definition a formal one, treating effectiveness as a defining feature of military innovation. 6

Equating peacetime innovation with greater military effectiveness is puzzling, however, because scholars recognize that the two are not synonyms. Barry Posen categorizes military doctrine as either innovative or stagnant, but he recognizes that “neither … should be valued a priori.” He suggests that instead of stagnation, “ stability might be a better choice of terms, as it is less loaded [italics in the original].” 7 Historians Allan Millett and Williamson Murray caution that during peacetime innovation “wrong choices and irrelevant investments will occur and will be hard to correct.” 8 Others warn that “it is entirely possible that a military innovation may make a military less effective,” and that “not all innovations should be welcomed.” 9

Nonetheless, virtually all theories of military innovation are built and tested on cases of performance-enhancing innovations. Posen's influential study of the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain finds that it was the military services that innovated before the war that achieved political-military integration. 10 In Winning the Next War , another agenda-setting work, Stephen Rosen ignores “innovations that were put into practice but were clearly mistaken” because “despite an extensive and intensive search,” he finds that mistakes made by the U.S. military “all appear to have been the result of failures to innovate, rather than inappropriate innovations.” 11

When innovation improves performance, it is appropriate to merely explain its presence or absence, as existing theories aim to do. But this approach cannot fully explain whether, when, and how innovation affects military power. Moreover, equating innovation and effectiveness wrongly implies that resistance to innovation is always an undesirable military pathology. Military organizations are conservative for a reason: there are countless solutions to complex problems, but many of them could produce catastrophic results. Therefore, assuming improved performance strips the concept of innovation of its most interesting and dangerous attribute—it is a gamble that costly changes are worth making.

I define military innovation in this article as the process of creating a new capability—a new institutionalized technique of organized violence intended to convert a service's resources into success in future missions. 12 For instance, an air wing designed for strategic bombing will be organized, equipped, and trained to operate in a way that is distinct from close air support. Capabilities are embedded in the service's organization and equipment (i.e., force structure) and a relatively ordered and consistent way of using these components in combat (i.e., doctrine). Capabilities reflect the service's preferred methods of using military force in response to particular historical modes of warfare.

Following common practice, I limit the concept of military innovation's scope to major changes in peacetime at the service level. Most studies distinguish between peacetime innovation and wartime adaptation because their learning environments are different: performance feedback from combat is unavailable in the fog of peace. 13 I also focus on “major” military innovations, which Michael Horowitz defines as “a major change in the conduct of warfare” that involves “shifts in the core competencies of military organizations, or shifts in the tasks that the average soldiers perform.” 14 The unit of analysis is therefore an innovating service.

The ostensible purpose of innovation is to enhance military effectiveness. For the economist Joseph Schumpeter, innovation is a new production function that changes the rate of converting a fixed quantity of factors into products. 15 In a similar fashion, military innovation tries to improve the efficiency of converting allocated resources—money and personnel—into mission success by creating a new capability. Ideally, armed forces field capabilities that maximize their chances of accomplishing assigned missions at a minimal cost in resources.

But innovation's promise of resource efficiency and mission effectiveness comes with risks. The first risk is that creating a new capability is a step into the unknown without the benefit of experience, hindsight, or relevant skills. 16 The second risk relates to the destruction of old capabilities in the process of creating new ones, or what Schumpeter calls “creative destruction.” 17 As military organizations innovate, they are “down-grading or abandoning older concepts of operation and possibly of a formerly dominant weapon.” 18 In other words, “a military service destroys or thoroughly redirects an important part of itself.” 19 When a traditional capability is destroyed, it may be recoverable, but creative destruction inevitably involves opportunity costs. Destroying traditional capabilities is risky because they often are battle-tested methods of generating military power. After all, effective organizations survive and succeed in part by maintaining their existing “infrastructure”—those unglamorous and old investments. 20

For innovation to improve military effectiveness, it must create more combat power than it destroys. A military service ideally calibrates its balance of capabilities such that a new capability's marginal benefit equals or exceeds the marginal cost of losing traditional ones. But the optimal balance between creation and destruction is unknown. If the organization invests too heavily in the new capability, the costs to long-established capabilities can weaken the service's overall combat performance. Destructive changes are not adequately compensated by the creative developments allegedly taking their place. But if the organization invests too little, it forgoes potential gains in wartime effectiveness. Innovation is therefore an exercise in risk management, a balancing act between the promises of a new capability and the perils of losing older ones.

My central claim is that harmful innovation is more likely to occur when military services, faced with growing security commitments that outstrip shrinking resources, make desperate gambles on new capabilities to meet overly ambitious goals while cannibalizing older capabilities. The military service treats innovation as a silver bullet and endorses destroying traditional capabilities before innovation advocates can justify their beliefs about the new one's effectiveness. The service later discovers that the new capability alone may not accomplish assigned missions, that the enemy can exploit vulnerabilities produced by the loss of traditional capabilities, and that the service likely must restore traditional capabilities as a backstop to shore up its combat power. Figure 1 summarizes the causal logic.

commitment-resource gaps and the “wicked mismatch”

Achieving an economically solvent alignment between commitments and resources is a perennial concern of statecraft. The journalist Walter Lippmann popularized the idea that “foreign policy consists in bringing into balance, with a comfortable surplus of power in reserve, the nation's commitments and the nation's power.” 21 But when available means are insufficient to achieve desired political ends, there is overstretch or overcommitment. My theory emphasizes how the confluence of expanding commitments and shrinking resources—what I call a “wicked mismatch”—can shape innovation processes in harmful ways. The term is drawn from “wicked problems,” of which a key characteristic is that “proposed ‘solutions’ often turn out to be worse than the symptoms.” 22

Security commitments refer to the mission burdens assigned to a military service. Some commitments are written down in treaties or domestic legislation, whereas others are declared in speeches announcing a vital interest or policy doctrine. 23 The service uses these commitments to set appropriate benchmarks for the size, shape, and types of its forces, to which the state allocates money and personnel. These resources maintain or expand force structures, training regimens, military bases, administration, and operations. A military service also worries about whether it has enough personnel with the requisite skill and training to accomplish assigned missions. The service invests these resources into capabilities. 24

A commitment-resource gap develops when a service's mission burdens grow, its allocation of money and personnel shrink, or both. Mission burdens can grow in scope, intensity, or time. Mission scope widens when the state acquires new territories and bases to defend, makes or expands security guarantees to allies and partners, or adds entirely new tasks to a service's mission set. The mission burden intensity deepens when a mission becomes more difficult to accomplish because of threats such as a competitor's relative military strength, changes in an adversary's military strategy, or shifts in the technological landscape. Finally, a service's mission set demands higher levels of military readiness as war appears likelier and more imminent because of diplomatic crises, militarized disputes, or alarming intelligence assessments. 25

A gap can also open when the state reduces the service's allocated money or personnel. It might redirect money to other investments, social spending, or private consumption through tax cuts. Or civilian leaders might manipulate budget levels, provoking greater interservice competition over budget allocations. 26 Innovation scholars have also highlighted historical episodes in which civilian leaders shortened conscription time. 27 Moreover, the quantity and quality of personnel eligible for military service varies with a population's age distribution and the national system of military recruitment. 28

If the state reduces resources or expands commitments, all else being equal, it can weaken or exceed the service's capabilities and, by implication, its military effectiveness. One solution is retrenchment, which can take the form of territorial withdrawal, diplomatic accommodation, appeasement, arms control, or increasing reliance on allies. 29 Retrenchment, however, may weaken the state's security posture, embolden rivals, and afford domestic political opponents the opportunity to criticize incumbent leaders for reducing the credibility of the country's commitments, betraying allies, or being soft toward a security threat. Another remedy is a military buildup—allocating a larger portion of national resources to the service. 30 But constituents might prefer more spending on butter and less on guns, or policymakers might believe that a military buildup would destabilize the economy.

In contrast to these alternatives, innovation promises to restore the service's effectiveness by increasing efficiency without reducing commitments or expanding resources. 31 If political leaders reject both retrenchment and a military buildup, the affected service has an incentive to innovate. Whether it does so is outside the scope of this theory, but the size of a commitment-resource gap has important implications for whether innovation, if it occurs, is likely to succeed.

I expect that harmful innovation is more likely in a wicked mismatch, when a service's commitments are increasing and its resources are decreasing. In a wicked mismatch, a service's traditional capabilities not only are threatened by severe resource scarcity for the foreseeable future but also are rendered ineffective by the ambition of future missions. Expectations about the future are bleak. The service is therefore, I argue, in a professional and bureaucratic crisis. Officers doubt the service can perform assigned missions successfully, fear that the security of the state is at risk, and worry about the service's status and continuing relevance to national security. The service also wants to rectify this situation because it is overstretching its operational capacity by offering a semblance of meeting commitments, and business as usual offers little prospect of enhancing its political standing, contribution to national defense, and associated budget justifications.

Military innovation becomes a desperate, high-payoff, low-probability gamble to resolve the wicked mismatch by placing large bets on a new capability and cannibalizing traditional ones to do so. This strategy expands the range of possible outcomes: the new capability may significantly increase mission effectiveness and resource efficiency, but the service could perform even worse by neglecting traditional capabilities. 32 Such innovative gambles are surprising because the standard intuition in military innovation studies is that bureaucratic organizations in general, and military hierarchies in particular, are prone to stasis and resist dramatic changes that disrupt their standard operating procedures. 33 But a wicked mismatch generates pressures to adopt risk-seeking preferences. 34

Factors widely considered to be conducive to military innovation can, when taken to extremes, cause harm. Innovation scholars argue that shrinking resources or expanding commitments can align bureaucracy behind innovation, but I propose that extremely wide commitment-resource gaps significantly increase the probability that innovation will be too radical and ultimately self-defeating. Although similar behavior might result from either severe resource scarcity or ambitious commitments, the gap's size, not its drivers, ultimately trigger harmful innovation. The size of a commitment-resource gap, however, is in large part a matter of political and professional judgment and thus hard to measure objectively. 35 After all, armed services perennially complain about resource scarcity. A wicked mismatch therefore serves an analytical purpose because an extremely wide gap is especially obvious when resources shrink and commitments grow at the same time.

flawed innovation process

A wicked mismatch can produce flaws in the innovation process, with three particularly dangerous and potentially interrelated characteristics: radicalism, wishful thinking, and rushed development.

First, a wicked mismatch can elicit radical proposals to substitute a new capability for traditional ones. In professional military organizations, officers regularly search for new solutions that could increase effectiveness and improve efficiency. 36 What makes these proposals different is their radicalism—the degree of creative destruction—and their ready audience. The new capability promises to do much more with much less if it heavily cannibalizes traditional ones. Proponents of the new capability suggest that older capabilities are obsolete and cannot meet future mission requirements, and they further suggest that the military service should divest from old capabilities and transfer resources to create new ones. Such proposals should fare poorly in hierarchical and conservative military bureaucracies because of their organizational predilection for current operating procedures, but the crisis produced by a wicked mismatch opens an opportunity for radicalism to gain a wider audience. For example, the U.S. Army in the 1950s—facing global commitments in Europe and Asia amid shrinking personnel and money—adopted the pentomic division proposal, specializing in strategic mobility and limited nuclear warfare to the detriment of its conventional capabilities. 37

A second flaw in the innovation process is that a wicked mismatch incentivizes wishful thinking that exaggerates the rewards of innovation and downplays its risks. As the service experiments with the new capability, concerns almost inevitably arise. Political constraints might preclude its future use, the underlying technology might be premature, enemy countermeasures might negate its intended effects, or the loss of traditional capabilities might significantly weaken the service. But there is an organizational imperative to justify the service's continued relevance. 38 The service may therefore disregard plausible criticisms and ignore contemporary evidence that innovation's promises may be oversold. 39 Desperation motivates generous interpretations of the limited data about the new capability based on deductive logic that arrives at favorable conclusions, rather than prolonged empirical testing.

Wishful thinking can overemphasize the promises of innovation. For example, in the late 1940s, the U.S. Air Force innovated an air-atomic blitz capability in which an unescorted fleet of intercontinental bombers could rapidly drop most of if not the entire U.S. nuclear stockpile and destroy the Soviets' capacity and will to fight. But the air force dismissed several plausible criticisms of the new capability. First, it assumed that political and moral constraints would not preclude nuclear use in the next war. Second, it overlooked shortcomings in several key elements needed to ensure the success of the new capability: the intelligence to identify, the bombing accuracy to destroy, and the fighter escorts to reach critical targets deep within the Soviet Union. Consequently, the air force disproportionately invested in Strategic Air Command and cannibalized important capabilities in air superiority and close air support. 40

Wishful thinking can also de-emphasize the perils of creative destruction. The new capability will allegedly cover vulnerabilities opened by the loss of traditional methods. Officers may interpret experimental data using a one-size-fits-all approach to problem solving. For instance, if a capability allows the army to win a major war, then it should also be effective at fighting small wars. Another example of wishful thinking occurred before World War II, when it was thought that strategic bombers could operate effectively in independent flying formations without support from escort fighters.