What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Research Paper in High School

What’s covered:, how to pick a compelling research paper topic, how to format your research paper, tips for writing a research paper, do research paper grades impact your college chances.

A research paper can refer to a broad range of expanded essays used to explain your interpretation of a topic. This task is highly likely to be a common assignment in high school , so it’s always better to get a grasp on this sooner than later. Getting comfortable writing research papers does not have to be difficult, and can actually be pretty interesting when you’re genuinely intrigued by what you’re researching.

Regardless of what kind of research paper you are writing, getting started with a topic is the first step, and sometimes the hardest step. Here are some tips to get you started with your paper and get the writing to begin!

Pick A Topic You’re Genuinely Interested In

Nothing comes across as half-baked as much as a topic that is evidently uninteresting, not to the reader, but the writer. You can only get so far with a topic that you yourself are not genuinely happy writing, and this lack of enthusiasm cannot easily be created artificially. Instead, read about things that excite you, such as some specific concepts about the structure of atoms in chemistry. Take what’s interesting to you and dive further with a research paper.

If you need some ideas, check out our post on 52 interesting research paper topics .

The Topic Must Be A Focal Point

Your topic can almost be considered as the skeletal structure of the research paper. But in order to better understand this we need to understand what makes a good topic. Here’s an example of a good topic:

How does the amount of pectin in a vegetable affect its taste and other qualities?

This topic is pretty specific in explaining the goals of the research paper. If I had instead written something more vague such as Factors that affect taste in vegetables , the scope of the research immediately increased to a more herculean task simply because there is more to write about, some of which is overtly unnecessary. This is avoided by specifications in the topic that help guide the writer into a focused path.

By creating this specific topic, we can route back to it during the writing process to check if we’re addressing it often, and if we are then our writing is going fine! Otherwise, we’d have to reevaluate the progression of our paper and what to change. A good topic serves as a blueprint for writing the actual essay because everything you need to find out is in the topic itself, it’s almost like a sort of plan/instruction.

Formatting a research paper is important to not only create a “cleaner” more readable end product, but it also helps streamline the writing process by making it easier to navigate. The following guidelines on formatting are considered a standard for research papers, and can be altered as per the requirements of your specific assignments, just check with your teacher/grader!

Start by using a standard font like Times New Roman or Arial, in 12 or 11 sized font. Also, add one inch margins for the pages, along with some double spacing between lines. These specifications alone get you started on a more professional and cleaner looking research paper.

Paper Citations

If you’re creating a research paper for some sort of publication, or submission, you must use citations to refer to the sources you’ve used for the research of your topic. The APA citation style, something you might be familiar with, is the most popular citation style and it works as follows:

Author Last Name, First Initial, Publication Year, Book/Movie/Source title, Publisher/Organization

This can be applied to any source of media/news such as a book, a video, or even a magazine! Just make sure to use citation as much as possible when using external data and sources for your research, as it could otherwise land you in trouble with unwanted plagiarism.

Structuring The Paper

Structuring your paper is also important, but not complex either. Start by creating an introductory paragraph that’s short and concise, and tells the reader what they’re going to be reading about. Then move onto more contextual information and actual presentation of research. In the case of a paper like this, you could start with stating your hypothesis in regard to what you’re researching, or even state your topic again with more clarification!

As the paper continues you should be bouncing between views that support and go against your claim/hypothesis to maintain a neutral tone. Eventually you will reach a conclusion on whether or not your hypothesis was valid, and from here you can begin to close the paper out with citations and reflections on the research process.

Talk To Your Teacher

Before the process of searching for a good topic, start by talking to your teachers first! You should form close relations with them so they can help guide you with better inspiration and ideas.

Along the process of writing, you’re going to find yourself needing help when you hit walls. Specifically there will be points at which the scope of your research could seem too shallow to create sizable writing off of it, therefore a third person point of view could be useful to help think of workarounds in such situations.

You might be writing a research paper as a part of a submission in your applications to colleges, which is a great way to showcase your skills! Therefore, to really have a good chance to showcase yourself as a quality student, aim for a topic that doesn’t sell yourself short. It would be easier to tackle a topic that is not as intense to research, but the end results would be less worthwhile and could come across as lazy. Focus on something genuinely interesting and challenging so admissions offices know you are a determined and hard-working student!

Don’t Worry About Conclusions

The issue many students have with writing research papers, is that they aren’t satisfied with arriving at conclusions that do not support their original hypothesis. It’s important to remember that not arriving at a specific conclusion that your hypothesis was planning on, is totally fine! The whole point of a research paper is not to be correct, but it’s to showcase the trial and error behind learning and understanding something new.

If your findings clash against your initial hypothesis, all that means is you’ve arrived at a new conclusion that can help form a new hypothesis or claim, with sound reasoning! Getting rid of this mindset that forces you to warp around your hypothesis and claims can actually improve your research writing by a lot!

Colleges won’t ever see the grades for individual assignments, but they do care a bit more about the grades you achieve in your courses. Research papers may play towards your overall course grade based on the kind of class you’re in. Therefore to keep those grades up, you should try your absolute best on your essays and make sure they get high-quality reviews to check them too!

Luckily, CollegeVine’s peer review for essays does exactly that! This great feature allows you to get your essay checked by other users, and hence make a higher-quality essay that boosts your chances of admission into a university.

Want more info on your chances for college admissions? Check out CollegeVine’s admissions calculator, an intuitive tool that takes numerous factors into account as inputs before generating your unique chance of admission into an institute of your selection!

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Guide to Writing a Scientific Paper: A Focus on High School Through Graduate Level Student Research

Renee a. hesselbach.

1 NIEHS Children's Environmental Health Sciences Core Center, University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

David H. Petering

2 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Craig A. Berg

3 Curriculum and Instruction, University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Henry Tomasiewicz

Daniel weber.

This article presents a detailed guide for high school through graduate level instructors that leads students to write effective and well-organized scientific papers. Interesting research emerges from the ability to ask questions, define problems, design experiments, analyze and interpret data, and make critical connections. This process is incomplete, unless new results are communicated to others because science fundamentally requires peer review and criticism to validate or discard proposed new knowledge. Thus, a concise and clearly written research paper is a critical step in the scientific process and is important for young researchers as they are mastering how to express scientific concepts and understanding. Moreover, learning to write a research paper provides a tool to improve science literacy as indicated in the National Research Council's National Science Education Standards (1996), and A Framework for K–12 Science Education (2011), the underlying foundation for the Next Generation Science Standards currently being developed. Background information explains the importance of peer review and communicating results, along with details of each critical component, the Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results , and Discussion . Specific steps essential to helping students write clear and coherent research papers that follow a logical format, use effective communication, and develop scientific inquiry are described.

Introduction

A key part of the scientific process is communication of original results to others so that one's discoveries are passed along to the scientific community and the public for awareness and scrutiny. 1 – 3 Communication to other scientists ensures that new findings become part of a growing body of publicly available knowledge that informs how we understand the world around us. 2 It is also what fuels further research as other scientists incorporate novel findings into their thinking and experiments.

Depending upon the researcher's position, intent, and needs, communication can take different forms. The gold standard is writing scientific papers that describe original research in such a way that other scientists will be able to repeat it or to use it as a basis for their studies. 1 For some, it is expected that such articles will be published in scientific journals after they have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication. Scientists must submit their articles for examination by other scientists familiar with the area of research, who decide whether the work was conducted properly and whether the results add to the knowledge base and are conveyed well enough to merit publication. 2 If a manuscript passes the scrutiny of peer-review, it has the potential to be published. 1 For others, such as for high school or undergraduate students, publishing a research paper may not be the ultimate goal. However, regardless of whether an article is to be submitted for publication, peer review is an important step in this process. For student researchers, writing a well-organized research paper is a key step in learning how to express understanding, make critical connections, summarize data, and effectively communicate results, which are important goals for improving science literacy of the National Research Council's National Science Education Standards, 4 and A Framework for K–12 Science Education, 5 and the Next Generation Science Standards 6 currently being developed and described in The NSTA Reader's Guide to A Framework for K–12 Science Education. 7 Table 1 depicts the key skills students should develop as part of the Science as Inquiry Content Standard. Table 2 illustrates the central goals of A Framework for K–12 Science Education Scientific and Engineering Practices Dimension.

Key Skills of the Science as Inquiry National Science Education Content Standard

National Research Council (1996).

Important Practices of A Framework for K–12 Science Education Scientific and Engineering Practices Dimension

National Research Council (2011).

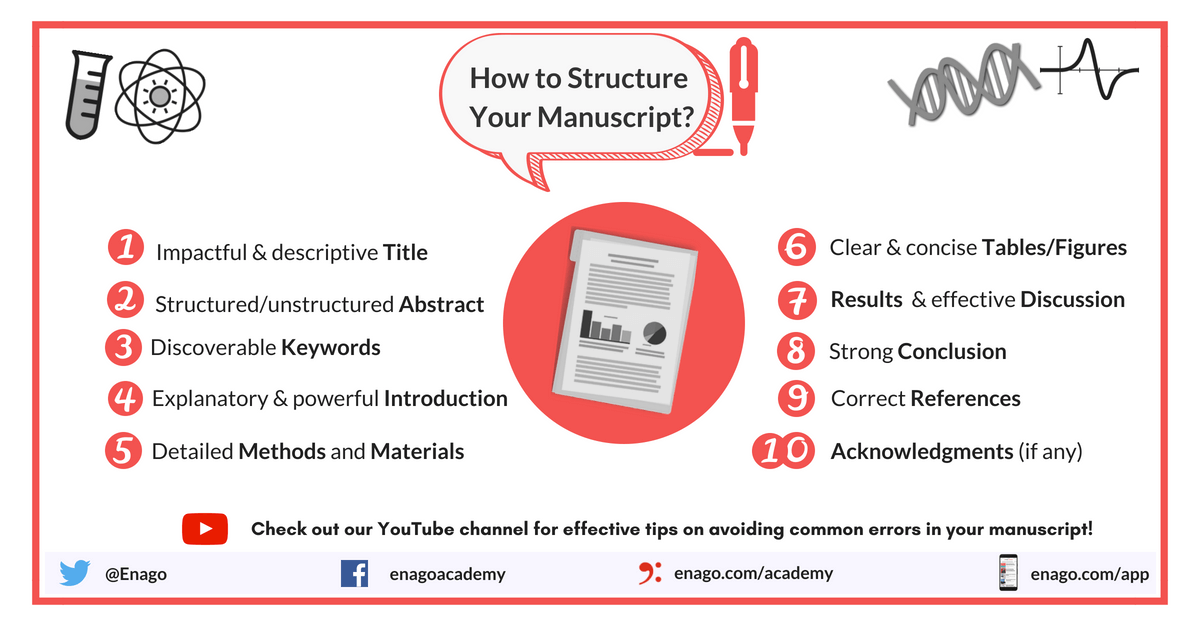

Scientific papers based on experimentation typically include five predominant sections: Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion . This structure is a widely accepted approach to writing a research paper, and has specific sections that parallel the scientific method. Following this structure allows the scientist to tell a clear, coherent story in a logical format, essential to effective communication. 1 , 2 In addition, using a standardized format allows the reader to find specific information quickly and easily. While readers may not have time to read the entire research paper, the predictable format allows them to focus on specific sections such as the Abstract , Introduction , and Discussion sections. Therefore, it is critical that information be placed in the appropriate and logical section of the report. 3

Guidelines for Writing a Primary Research Article

The Title sends an important message to the reader about the purpose of the paper. For example, Ethanol Effects on the Developing Zebrafish: Neurobehavior and Skeletal Morphogenesis 8 tells the reader key information about the content of the research paper. Also, an appropriate and descriptive title captures the attention of the reader. When composing the Title , students should include either the aim or conclusion of the research, the subject, and possibly the independent or dependent variables. Often, the title is created after the body of the article has been written, so that it accurately reflects the purpose and content of the article. 1 , 3

The Abstract provides a short, concise summary of the research described in the body of the article and should be able to stand alone. It provides readers with a quick overview that helps them decide whether the article may be interesting to read. Included in the Abstract are the purpose or primary objectives of the experiment and why they are important, a brief description of the methods and approach used, key findings and the significance of the results, and how this work is different from the work of others. It is important to note that the Abstract briefly explains the implications of the findings, but does not evaluate the conclusions. 1 , 3 Just as with the Title , this section needs to be written carefully and succinctly. Often this section is written last to ensure it accurately reflects the content of the paper. Generally, the optimal length of the Abstract is one paragraph between 200 and 300 words, and does not contain references or abbreviations.

All new research can be categorized by field (e.g., biology, chemistry, physics, geology) and by area within the field (e.g., biology: evolution, ecology, cell biology, anatomy, environmental health). Many areas already contain a large volume of published research. The role of the Introduction is to place the new research within the context of previous studies in the particular field and area, thereby introducing the audience to the research and motivating the audience to continue reading. 1

Usually, the writer begins by describing what is known in the area that directly relates to the subject of the article's research. Clearly, this must be done judiciously; usually there is not room to describe every bit of information that is known. Each statement needs one or more references from the scientific literature that supports its validity. Students must be reminded to cite all references to eliminate the risk of plagiarism. 2 Out of this context, the author then explains what is not known and, therefore, what the article's research seeks to find out. In doing so, the scientist provides the rationale for the research and further develops why this research is important. The final statement in the Introduction should be a clearly worded hypothesis or thesis statement, as well as a brief summary of the findings as they relate to the stated hypothesis. Keep in mind that the details of the experimental findings are presented in the Results section and are aimed at filling the void in our knowledge base that has been pointed out in the Introduction .

Materials and Methods

Research utilizes various accepted methods to obtain the results that are to be shared with others in the scientific community. The quality of the results, therefore, depends completely upon the quality of the methods that are employed and the care with which they are applied. The reader will refer to the Methods section: (a) to become confident that the experiments have been properly done, (b) as the guide for repeating the experiments, and (c) to learn how to do new methods.

It is particularly important to keep in mind item (b). Since science deals with the objective properties of the physical and biological world, it is a basic axiom that these properties are independent of the scientist who reported them. Everyone should be able to measure or observe the same properties within error, if they do the same experiment using the same materials and procedures. In science, one does the same experiment by exactly repeating the experiment that has been described in the Methods section. Therefore, someone can only repeat an experiment accurately if all the relevant details of the experimental methods are clearly described. 1 , 3

The following information is important to include under illustrative headings, and is generally presented in narrative form. A detailed list of all the materials used in the experiments and, if important, their source should be described. These include biological agents (e.g., zebrafish, brine shrimp), chemicals and their concentrations (e.g., 0.20 mg/mL nicotine), and physical equipment (e.g., four 10-gallon aquariums, one light timer, one 10-well falcon dish). The reader needs to know as much as necessary about each of the materials; however, it is important not to include extraneous information. For example, consider an experiment involving zebrafish. The type and characteristics of the zebrafish used must be clearly described so another scientist could accurately replicate the experiment, such as 4–6-month-old male and female zebrafish, the type of zebrafish used (e.g., Golden), and where they were obtained (e.g., the NIEHS Children's Environmental Health Sciences Core Center in the WATER Institute of the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee). In addition to describing the physical set-up of the experiment, it may be helpful to include photographs or diagrams in the report to further illustrate the experimental design.

A thorough description of each procedure done in the reported experiment, and justification as to why a particular method was chosen to most effectively answer the research question should also be included. For example, if the scientist was using zebrafish to study developmental effects of nicotine, the reader needs to know details about how and when the zebrafish were exposed to the nicotine (e.g., maternal exposure, embryo injection of nicotine, exposure of developing embryo to nicotine in the water for a particular length of time during development), duration of the exposure (e.g., a certain concentration for 10 minutes at the two-cell stage, then the embryos were washed), how many were exposed, and why that method was chosen. The reader would also need to know the concentrations to which the zebrafish were exposed, how the scientist observed the effects of the chemical exposure (e.g., microscopic changes in structure, changes in swimming behavior), relevant safety and toxicity concerns, how outcomes were measured, and how the scientist determined whether the data/results were significantly different in experimental and unexposed control animals (statistical methods).

Students must take great care and effort to write a good Methods section because it is an essential component of the effective communication of scientific findings.

The Results section describes in detail the actual experiments that were undertaken in a clear and well-organized narrative. The information found in the Methods section serves as background for understanding these descriptions and does not need to be repeated. For each different experiment, the author may wish to provide a subtitle and, in addition, one or more introductory sentences that explains the reason for doing the experiment. In a sense, this information is an extension of the Introduction in that it makes the argument to the reader why it is important to do the experiment. The Introduction is more general; this text is more specific.

Once the reader understands the focus of the experiment, the writer should restate the hypothesis to be tested or the information sought in the experiment. For example, “Atrazine is routinely used as a crop pesticide. It is important to understand whether it affects organisms that are normally found in soil. We decided to use worms as a test organism because they are important members of the soil community. Because atrazine damages nerve cells, we hypothesized that exposure to atrazine will inhibit the ability of worms to do locomotor activities. In the first experiment, we tested the effect of the chemical on burrowing action.”

Then, the experiments to be done are described and the results entered. In reporting on experimental design, it is important to identify the dependent and independent variables clearly, as well as the controls. The results must be shown in a way that can be reproduced by the reader, but do not include more details than needed for an effective analysis. Generally, meaningful and significant data are gathered together into tables and figures that summarize relevant information, and appropriate statistical analyses are completed based on the data gathered. Besides presenting each of these data sources, the author also provides a written narrative of the contents of the figures and tables, as well as an analysis of the statistical significance. In the narrative, the writer also connects the results to the aims of the experiment as described above. Did the results support the initial hypothesis? Do they provide the information that was sought? Were there problems in the experiment that compromised the results? Be careful not to include an interpretation of the results; that is reserved for the Discussion section.

The writer then moves on to the next experiment. Again, the first paragraph is developed as above, except this experiment is seen in the context of the first experiment. In other words, a story is being developed. So, one commonly refers to the results of the first experiment as part of the basis for undertaking the second experiment. “In the first experiment we observed that atrazine altered burrowing activity. In order to understand how that might occur, we decided to study its impact on the basic biology of locomotion. Our hypothesis was that atrazine affected neuromuscular junctions. So, we did the following experiment..”

The Results section includes a focused critical analysis of each experiment undertaken. A hallmark of the scientist is a deep skepticism about results and conclusions. “Convince me! And then convince me again with even better experiments.” That is the constant challenge. Without this basic attitude of doubt and willingness to criticize one's own work, scientists do not get to the level of concern about experimental methods and results that is needed to ensure that the best experiments are being done and the most reproducible results are being acquired. Thus, it is important for students to state any limitations or weaknesses in their research approach and explain assumptions made upfront in this section so the validity of the research can be assessed.

The Discussion section is the where the author takes an overall view of the work presented in the article. First, the main results from the various experiments are gathered in one place to highlight the significant results so the reader can see how they fit together and successfully test the original hypotheses of the experiment. Logical connections and trends in the data are presented, as are discussions of error and other possible explanations for the findings, including an analysis of whether the experimental design was adequate. Remember, results should not be restated in the Discussion section, except insofar as it is absolutely necessary to make a point.

Second, the task is to help the reader link the present work with the larger body of knowledge that was portrayed in the Introduction . How do the results advance the field, and what are the implications? What does the research results mean? What is the relevance? 1 , 3

Lastly, the author may suggest further work that needs to be done based on the new knowledge gained from the research.

Supporting Documentation and Writing Skills

Tables and figures are included to support the content of the research paper. These provide the reader with a graphic display of information presented. Tables and figures must have illustrative and descriptive titles, legends, interval markers, and axis labels, as appropriate; should be numbered in the order that they appear in the report; and include explanations of any unusual abbreviations.

The final section of the scientific article is the Reference section. When citing sources, it is important to follow an accepted standardized format, such as CSE (Council of Science Editors), APA (American Psychological Association), MLA (Modern Language Association), or CMS (Chicago Manual of Style). References should be listed in alphabetical order and original authors cited. All sources cited in the text must be included in the Reference section. 1

When writing a scientific paper, the importance of writing concisely and accurately to clearly communicate the message should be emphasized to students. 1 – 3 Students should avoid slang and repetition, as well as abbreviations that may not be well known. 1 If an abbreviation must be used, identify the word with the abbreviation in parentheses the first time the term is used. Using appropriate and correct grammar and spelling throughout are essential elements of a well-written report. 1 , 3 Finally, when the article has been organized and formatted properly, students are encouraged to peer review to obtain constructive criticism and then to revise the manuscript appropriately. Good scientific writing, like any kind of writing, is a process that requires careful editing and revision. 1

A key dimension of NRC's A Framework for K–12 Science Education , Scientific and Engineering Practices, and the developing Next Generation Science Standards emphasizes the importance of students being able to ask questions, define problems, design experiments, analyze and interpret data, draw conclusions, and communicate results. 5 , 6 In the Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) program at the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, we found the guidelines presented in this article useful for high school science students because this group of students (and probably most undergraduates) often lack in understanding of, and skills to develop and write, the various components of an effective scientific paper. Students routinely need to focus more on the data collected and analyze what the results indicated in relation to the research question/hypothesis, as well as develop a detailed discussion of what they learned. Consequently, teaching students how to effectively organize and write a research report is a critical component when engaging students in scientific inquiry.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by a Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) grant (Award Number R25RR026299) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The SEPA program at the University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee is part of the Children's Environmental Health Sciences Core Center, Community Outreach and Education Core, funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Award Number P30ES004184). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Scaffolding Methods for Research Paper Writing

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

Students will use scaffolding to research and organize information for writing a research paper. A research paper scaffold provides students with clear support for writing expository papers that include a question (problem), literature review, analysis, methodology for original research, results, conclusion, and references. Students examine informational text, use an inquiry-based approach, and practice genre-specific strategies for expository writing. Depending on the goals of the assignment, students may work collaboratively or as individuals. A student-written paper about color psychology provides an authentic model of a scaffold and the corresponding finished paper. The research paper scaffold is designed to be completed during seven or eight sessions over the course of four to six weeks.

Featured Resources

- Research Paper Scaffold : This handout guides students in researching and organizing the information they need for writing their research paper.

- Inquiry on the Internet: Evaluating Web Pages for a Class Collection : Students use Internet search engines and Web analysis checklists to evaluate online resources then write annotations that explain how and why the resources will be valuable to the class.

From Theory to Practice

- Research paper scaffolding provides a temporary linguistic tool to assist students as they organize their expository writing. Scaffolding assists students in moving to levels of language performance they might be unable to obtain without this support.

- An instructional scaffold essentially changes the role of the teacher from that of giver of knowledge to leader in inquiry. This relationship encourages creative intelligence on the part of both teacher and student, which in turn may broaden the notion of literacy so as to include more learning styles.

- An instructional scaffold is useful for expository writing because of its basis in problem solving, ownership, appropriateness, support, collaboration, and internalization. It allows students to start where they are comfortable, and provides a genre-based structure for organizing creative ideas.

- In order for students to take ownership of knowledge, they must learn to rework raw information, use details and facts, and write.

- Teaching writing should involve direct, explicit comprehension instruction, effective instructional principles embedded in content, motivation and self-directed learning, and text-based collaborative learning to improve middle school and high school literacy.

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 2. Students read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions (e.g., philosophical, ethical, aesthetic) of human experience.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

Computers with Internet access and printing capability

- Research Paper Scaffold

- Example Research Paper Scaffold

- Example Student Research Paper

- Internet Citation Checklist

- Research Paper Scoring Rubric

- Permission Form (optional)

Preparation

Student objectives.

Students will

- Formulate a clear thesis that conveys a perspective on the subject of their research

- Practice research skills, including evaluation of sources, paraphrasing and summarizing relevant information, and citation of sources used

- Logically group and sequence ideas in expository writing

- Organize and display information on charts, maps, and graphs

Session 1: Research Question

You should approve students’ final research questions before Session 2. You may also wish to send home the Permission Form with students, to make parents aware of their child’s research topic and the project due dates.

Session 2: Literature Review—Search

Prior to this session, you may want to introduce or review Internet search techniques using the lesson Inquiry on the Internet: Evaluating Web Pages for a Class Collection . You may also wish to consult with the school librarian regarding subscription databases designed specifically for student research, which may be available through the school or public library. Using these types of resources will help to ensure that students find relevant and appropriate information. Using Internet search engines such as Google can be overwhelming to beginning researchers.

Session 3: Literature Review—Notes

Students need to bring their articles to this session. For large classes, have students highlight relevant information (as described below) and submit the articles for assessment before beginning the session.

Checking Literature Review entries on the same day is best practice, as it gives both you and the student time to plan and address any problems before proceeding. Note that in the finished product this literature review section will be about six paragraphs, so students need to gather enough facts to fit this format.

Session 4: Analysis

Session 5: original research.

Students should design some form of original research appropriate to their topics, but they do not necessarily have to conduct the experiments or surveys they propose. Depending on the appropriateness of the original research proposals, the time involved, and the resources available, you may prefer to omit the actual research or use it as an extension activity.

Session 6: Results (optional)

Session 7: conclusion, session 8: references and writing final draft, student assessment / reflections.

- Observe students’ participation in the initial stages of the Research Paper Scaffold and promptly address any errors or misconceptions about the research process.

- Observe students and provide feedback as they complete each section of the Research Paper Scaffold.

- Provide a safe environment where students will want to take risks in exploring ideas. During collaborative work, offer feedback and guidance to those who need encouragement or require assistance in learning cooperation and tolerance.

- Involve students in using the Research Paper Scoring Rubric for final evaluation of the research paper. Go over this rubric during Session 8, before they write their final drafts.

- Strategy Guides

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

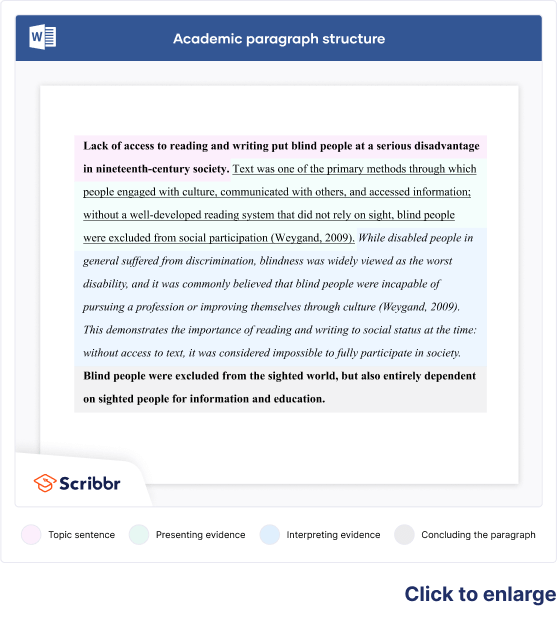

- Academic Paragraph Structure | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Academic Paragraph Structure | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on October 25, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on March 27, 2023.

Every piece of academic writing is structured by paragraphs and headings . The number, length and order of your paragraphs will depend on what you’re writing—but each paragraph must be:

- Unified : all the sentences relate to one central point or idea.

- Coherent : the sentences are logically organized and clearly connected.

- Relevant : the paragraph supports the overall theme and purpose of the paper.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: identify the paragraph’s purpose, step 2: show why the paragraph is relevant, step 3: give evidence, step 4: explain or interpret the evidence, step 5: conclude the paragraph, step 6: read through the whole paragraph, when to start a new paragraph.

First, you need to know the central idea that will organize this paragraph. If you have already made a plan or outline of your paper’s overall structure , you should already have a good idea of what each paragraph will aim to do.

You can start by drafting a sentence that sums up your main point and introduces the paragraph’s focus. This is often called a topic sentence . It should be specific enough to cover in a single paragraph, but general enough that you can develop it over several more sentences.

Although the Braille system gained immediate popularity with the blind students at the Institute in Paris, it had to gain acceptance among the sighted before its adoption throughout France.

This topic sentence:

- Transitions from the previous paragraph (which discussed the invention of Braille).

- Clearly identifies this paragraph’s focus (the acceptance of Braille by sighted people).

- Relates to the paper’s overall thesis.

- Leaves space for evidence and analysis.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

The topic sentence tells the reader what the paragraph is about—but why does this point matter for your overall argument? If this isn’t already clear from your first sentence, you can explain and expand on its meaning.

This support was necessary because sighted teachers and leaders had ultimate control over the propagation of Braille resources.

- This sentence expands on the topic and shows how it fits into the broader argument about the social acceptance of Braille.

Now you can support your point with evidence and examples. “Evidence” here doesn’t just mean empirical facts—the form it takes will depend on your discipline, topic and approach. Common types of evidence used in academic writing include:

- Quotations from literary texts , interviews , and other primary sources .

- Summaries , paraphrases , or quotations of secondary sources that provide information or interpretation in support of your point.

- Qualitative or quantitative data that you have gathered or found in existing research.

- Descriptive examples of artistic or musical works, events, or first-hand experiences.

Make sure to properly cite your sources .

Many of the teachers at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth resisted Braille’s system because they found the tactile method of reading difficult to learn (Bullock & Galst, 2009).

- This sentence cites specific evidence from a secondary source , demonstrating sighted people’s reluctance to accept Braille.

Now you have to show the reader how this evidence adds to your point. How you do so will depend on what type of evidence you have used.

- If you quoted a passage, give your interpretation of the quotation.

- If you cited a statistic, tell the reader what it implies for your argument.

- If you referred to information from a secondary source, show how it develops the idea of the paragraph.

This resistance was symptomatic of the prevalent attitude that the blind population had to adapt to the sighted world rather than develop their own tools and methods.

- This sentence adds detail and interpretation to the evidence, arguing that this specific fact reveals something more general about social attitudes at the time.

Steps 3 and 4 can be repeated several times until your point is fully developed. Use transition words and phrases to show the connections between different sentences in the paragraph.

Over time, however, with the increasing impetus to make social contribution possible for all, teachers began to appreciate the usefulness of Braille’s system (Bullock & Galst, 2009). Access to reading could help improve the productivity and integration of people with vision loss.

- The evidence tells us about the changing attitude to Braille among the sighted.

- The interpretation argues for why this change occurred as part of broader social shifts.

Finally, wrap up the paragraph by returning to your main point and showing the overall consequences of the evidence you have explored.

This particular paragraph takes the form of a historical story—giving evidence and analysis of each step towards Braille’s widespread acceptance.

It took approximately 30 years, but the French government eventually approved the Braille system, and it was established throughout the country (Bullock & Galst, 2009).

- The final sentence ends the story with the consequences of these events.

When you think you’ve fully developed your point, read through the final result to make sure each sentence follows smoothly and logically from the last and adds up to a coherent whole.

Although the Braille system gained immediate popularity with the blind students at the Institute in Paris, it had to gain acceptance among the sighted before its adoption throughout France. This support was necessary because sighted teachers and leaders had ultimate control over the propagation of Braille resources. Many of the teachers at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth resisted learning Braille’s system because they found the tactile method of reading difficult to learn (Bullock & Galst, 2009). This resistance was symptomatic of the prevalent attitude that the blind population had to adapt to the sighted world rather than develop their own tools and methods. Over time, however, with the increasing impetus to make social contribution possible for all, teachers began to appreciate the usefulness of Braille’s system (Bullock & Galst, 2009). Access to reading could help improve the productivity and integration of people with vision loss. It took approximately 30 years, but the French government eventually approved the Braille system, and it was established throughout the country (Bullock & Galst, 2009).

Not all paragraphs will look exactly like this. Depending on what your paper aims to do, you might:

- Bring together examples that seem very different from each other, but have one key point in common.

- Include just one key piece of evidence (such as a quotation or statistic) and analyze it in depth over several sentences.

- Break down a concept or category into various parts to help the reader understand it.

The introduction and conclusion paragraphs will also look different. The only universal rule is that your paragraphs must be unified , coherent and relevant . If you struggle with structuring your paragraphs, you could consider using a paper editing service for personal, in-depth feedback.

As soon as you address a new idea, argument or issue, you should start a new paragraph. To determine if your paragraph is complete, ask yourself:

- Do all your sentences relate to the topic sentence?

- Does each sentence make logical sense in relation to the one before it?

- Have you included enough evidence or examples to demonstrate your point?

- Is it clear what each piece of evidence means and why you have included it?

- Does all the evidence fit together and tell a coherent story?

Don’t think of paragraphs as isolated units—they are part of a larger argument that should flow organically from one point to the next. Before you start a new paragraph, consider how you will transition between ideas.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 27). Academic Paragraph Structure | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/paragraph-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, example of a great essay | explanations, tips & tricks, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, transition words & phrases | list & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Just another WordPress site

How to Write a High School Research Paper in 6 Easy Steps

What is a research paper? It is a piece of writing where its author conducts a study on a certain topic, interprets new facts, based on experiments, or new opinions, based on comparing existing scientific concepts, and makes important conclusions or proves a thesis.

Your writing assignments, such as essays, are very important for your future career. Excellent mastering the language is very important for you if you decide to enter a university or a college. It shows that you read a lot of books and your cultural level is high.

For an excellent paper writing you need to operate facts and concepts, know the subject well enough to see what has not been studied yet, what new sides of the scientific question have to be highlighted. So, the first important condition for writing a remarkable research paper is to have enough knowledge on the topic.

A well-written research paper should be properly structured. The process of writing can be subdivided into six steps:

- Conducting preliminary research and choosing a topic;

- Writing a thesis;

- Writing an outline;

- Writing the introduction, the body, the conclusion;

- Creating a reference page;

- Editing and proofreading the paper.

The length of the paper may be different. You should keep focused on the essence of your arguments. Your style of writing depends on the topic, but you should remember that it is an academic paper and it requires to be specially formatted. Sounds difficult? Not at all! In this article, we’ll teach you how to write an A+ paper the easy way. Each of the steps will be explained in detail so that you could start your work and write your paper with enthusiasm even if you are not a born prolific writer. After all, it is the result that matters. But if you understand your purpose and have a perfect plan of action, top-notch quality is guaranteed! In this article, you will find tips on how to write a research paper in an easy way.

Preparatory Stage – Understand Your Assignment and Research Your Topic

They say a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. It may be true for writing a research paper as well. It may be difficult to start writing a research paper in high school. The first thing you will have to do is to read and understand your assignment. That may be a real problem if you don’t understand it. Anyway, you should know the length of the paper, what types of sources are allowed to be used when you will have to hand in your paper, how will you have to format the paper.

Sometimes a topic for your paper is provided and sometimes you have to choose a topic yourself. Your topic should be interesting for you and the reader. You will have to spend a lot of time researching, looking through different sources in the library, browsing through websites to find good research paper topics. That is why your enthusiasm matters. The paper should answer a certain question, it should point out new information in the given scientific area.

If you choose a topic yourself, you have to find out if there is enough material on the topic. There have to be a lot of different sources to write a research topic, pay attention to trusted sources (books, cited articles, scientific journals). You should have enough information to study the topic from different angles. If there is not enough information you might want to choose a different topic. Choosing an interesting paper topic with a lot of resources is vital for your success. You can use brainstorming to choose a better topic. The more interesting the topic is for you the more interesting the results you may attain. Maybe, you will make a discovery, and we wish you success!

Write Your Research Paper

#1. define your thesis statement.

To write a thesis statement is very important for your high school research paper. It may consist of one or two sentences and express the main idea of the paper or essay, defining your point on the topic. It briefly tells the reader what the paper is about. The thesis statement outlines the contents of the paper you create and conveys important and significant results of your study, it explains why your research paper is valuable and worth reading. A good research paper should always contain a strong and clear thesis statement. Explain your point of view and what position you will support and why. Your thesis will serve as a transition to the body of your paper.

#2. Construct Your Outline

After browsing through resources you find out how much information on the topic is available. Now you can start constructing your outline. The outline is not always required, though. But sometimes your paper structure overview is needed to point out the most important aspects of your writing assignment. An outline is your plan for the research paper and it can be a short one (up to 5 sentences) or a detailed one.

Writing an outline can seem difficult, but if you have enough information, it will be easy to sort your ideas and facts for writing your research papers. It will be helpful if you write an outline for your research paper. It might be helpful for your essay writing.

#3. Write the Body Paragraphs

The body is the central and the longest part of your research paper being of the most important informational value. It may include new arguments supported by experimental facts. You write about new concepts and support them with your practical results. Or it this part you analyze the resources, compare the opinions of different authors and make your conclusions.

Writing your research paper you should pay attention to more credible sources, for example, more cited articles. Scientific journals are a good source of such trusted resources. When you write the body, try to use newer and trusted contemporary materials that will contain more recent scientific data and results of contemporary research. More cited sources are more preferable, because that means they have more value in this field of research and they are more trusted and credible. In the body, the main concepts of your research paper are explained. You express your point of view on the subject and give a detailed and logically proved explanation to that.

As the body is the longest and the most informative part of your work, it will helpful to divide it into body paragraphs. Each paragraph should express a certain idea. The use of headings and subheadings to logically structure this part is a good idea. Each paragraph should express and develop a new idea.

#4. Create Your Introduction and Conclusion

The introduction is the first part of your high school research paper. When you write this part, consider using a compelling first sentence that will grab the reader’s attention. Even if it is research it doesn’t matter what your writing should be dull. You should explain the purpose of your research paper and what scientific methods you used to obtain the desired result. Analysis of existing scientific concepts and comparing facts and opinions don’t require conducting any experiments. Some topics require an experimental part, though. Briefly outline what methods you used. The introductory part may be concluded with a thesis statement, though it is not obligatory in all research papers.

You may start your introductory part writing about the main idea of your paper so that the reader can make ahead or tail of it. Then you should persuasively prove that your idea is scientifically important, that it is new and why the reader should go on reading your paper. A valuable and clear message should be conveyed in the introduction, to stimulate the reader to read further.

The conclusion is the final part of your research paper. How do you write it? It is one of the most important parts of your scientific paper. It contains an overview of the whole paper and also some suppositions about the future of the scientific question.

Some students writing a research paper underestimate the meaning of the conclusion but it should not be the case. A good beginning makes a good ending, as they say. A poorly written conclusion may spoil the impression of the reader even from a very well written research paper, while an impressive one may stimulate further research of the subject.