Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, interpretation & debate, the preamble, matters of debate, common interpretation, giving meaning to the preamble, the preamble’s significance for constitutional interpretation.

by Erwin Chemerinsky

Dean of Berkeley Law School; Jesse H. Choper Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of California - Berkley Law School

by Michael Stokes Paulsen

Distinguished University Chair and Professor at University of St. Thomas School of Law

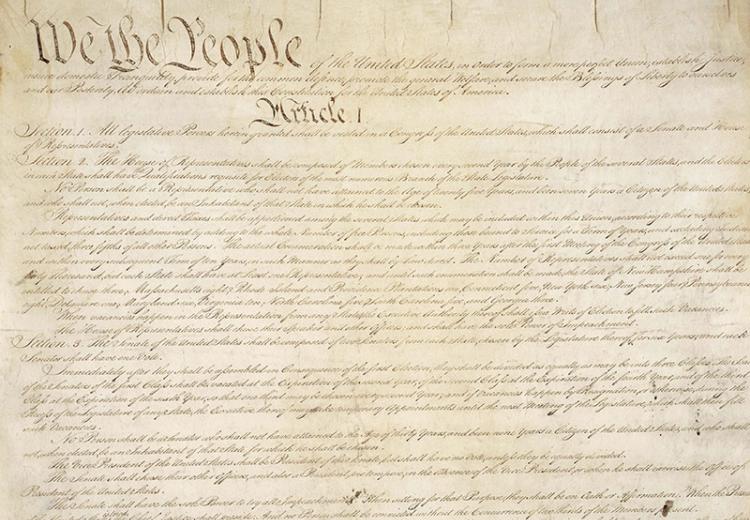

The Preamble of the U.S. Constitution—the document’s famous first fifty-two words— introduces everything that is to follow in the Constitution’s seven articles and twenty-seven amendments. It proclaims who is adopting this Constitution: “We the People of the United States.” It describes why it is being adopted—the purposes behind the enactment of America’s charter of government. And it describes what is being adopted: “ this Constitution ”—a single authoritative written text to serve as fundamental law of the land. Written constitutionalism was a distinctively American innovation, and one that the framing generation considered the new nation’s greatest contribution to the science of government.

The word “preamble,” while accurate, does not quite capture the full importance of this provision. “Preamble” might be taken—we think wrongly—to imply that these words are merely an opening rhetorical flourish or frill without meaningful effect. To be sure, “preamble” usefully conveys the idea that this provision does not itself confer or delineate powers of government or rights of citizens. Those are set forth in the substantive articles and amendments that follow in the main body of the Constitution’s text. It was well understood at the time of enactment that preambles in legal documents were not themselves substantive provisions and thus should not be read to contradict, expand, or contract the document’s substantive terms.

But that does not mean the Constitution’s Preamble lacks its own legal force. Quite the contrary, it is the provision of the document that declares the enactment of the provisions that follow. Indeed, the Preamble has sometimes been termed the “Enacting Clause” of the Constitution, in that it declares the fact of adoption of the Constitution (once sufficient states had ratified it): “We the People of the United States . . . do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Importantly, the Preamble declares who is enacting this Constitution—the people of “the United States.” The document is the collective enactment of all U.S. citizens. The Constitution is “owned” (so to speak) by the people, not by the government or any branch thereof. We the People are the stewards of the U.S. Constitution and remain ultimately responsible for its continued existence and its faithful interpretation.

It is sometimes observed that the language “We the People of the United States ” was inserted at the Constitutional Convention by the “Committee of Style,” which chose those words—rather than “We the People of the States of . . .”, followed by a listing of the thirteen states, for a simple practical reason: it was unclear how many states would actually ratify the proposed new constitution. (Article VII declared that the Constitution would come into effect once nine of thirteen states had ratified it; and as it happened two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, did not ratify until after George Washington had been inaugurated as the first President under the Constitution.) The Committee of Style thus could not safely choose to list all of the states in the Preamble. So they settled on the language of both “We the People of the United States.”

Nonetheless, the language was consciously chosen. Regardless of its origins in practical considerations or as a matter of “style,” the language actually chosen has important substantive consequences. “We the People of the United States” strongly supports the idea that the Constitution is one for a unified nation , rather than a treaty of separate sovereign states. (This, of course, had been the arrangement under the Articles of Confederation, the document the Constitution was designed to replace.) The idea of nationhood is then confirmed by the first reason recited in the Preamble for adopting the new Constitution—“to form a more perfect Union.” On the eve of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln invoked these words in support of the permanence of the Union under the Constitution and the unlawfulness of states attempting to secede from that union.

The other purposes for adopting the Constitution, recited by the Preamble— to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity”—embody the aspirations that We the People have for our Constitution, and that were expected to flow from the substantive provisions that follow. The stated goal is to create a government that will meet the needs of the people.

As noted, the Preamble’s statements of purpose do not themselves grant powers or confer rights; the substantive provisions in the main body of the Constitution do that. There is not, for example, a general government power to do whatever it judges will “promote the general Welfare.” The national government’s powers are specified in Article I and other provisions of the Constitution, not the Preamble. Congress has never relied on the Preamble alone as the basis for a claimed power to enact a law, and the Supreme Court has never relied on the Preamble as the sole basis for any constitutional decision. Still, the declared purposes for the Constitution can assist in understanding, interpreting, and applying the specific powers listed in the articles, for the simple reason that the Constitution should be interpreted in a manner that is faithful to its purposes.

Finally, the Preamble declares that what the people have ordained and established is “ this Constitution”—referring, obviously enough, to the written document that the Preamble introduces. That language is repeated in the Supremacy Clause of Article VI, which declares that “this Constitution” shall be the supreme law for the entire nation. The written nature of the Constitution as a single binding text matters and was important to the framing generation. The U.S. Constitution contrasts with the arrangement of nations like Great Britain, whose “constitution” is a looser collection of written and unwritten traditions constituting the established practice over time. America has a written constitution, not an unwritten one. The boundaries of what may be said and done in the name of the Constitution are marked by the words, phrases, and structure of the document itself. To be sure, there are disputes over what those words mean and how they are to be applied. But the enterprise of written constitutionalism is, at its core, the faithful interpretation and application of a written document adopted by the people as supreme law: “this Constitution for the United States of America.”

The Preamble to the Constitution has been largely ignored by lawyers and courts through American history. Rarely has a Supreme Court decision relied on it, even as a guide in interpreting the Constitution. But long ago, in Marbury v. Madison (1803), the Court declared “it cannot be presumed that any clause in the constitution is intended to be without effect; and therefore such construction is inadmissible, unless the words require it.” If the Preamble is read carefully and taken seriously, basic constitutional values can be found within it that should guide the interpretation of the Constitution.

The Court has rejected the relevance of the Preamble in constitutional decisions. In 1905, in Jacobson v. Massachusetts , the Supreme Court ruled that laws cannot be challenged or declared unconstitutional based on the Preamble. The Court declared: “Although that Preamble indicates the general purposes for which the people ordained and established the Constitution, it has never been regarded as the source of any substantive power conferred on the Government of the United States or on any of its Departments.” In the few occasions over the last century in which the Preamble has been mentioned, the Court has summarily denied its relevance to constitutional law.

But the Preamble states basic values that should guide the understanding of the Constitution. First, it is created by “We the People.” It is the people who are sovereign. This makes clear that the United States is to be a democracy, not a monarchy or a theocracy or a totalitarian government that were the dominant forms of government throughout world history. Early in American history, in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), Chief Justice John Marshall stressed the importance of the government being created by the people. The State of Maryland claimed that it was the state governments who formed the United States and that therefore it is the states who are sovereign. The Court rejected this, quoting the Preamble and declaring: “The government proceeds directly from the people; is ‘ordained and established,’ in the name of the people.”

Second, the Constitution exists to create effective governance for the nation. The Preamble states that the Constitution exists “to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, [and] promote the general Welfare.” The emphasis on establishing a “Union” and a successful government for it is not surprising because the Constitution was created in response to the failures of the Articles of Confederation which was a compact among the states where there was a weak national government with little power. Throughout American history there have been battles over federalism and the authority of the federal government to take actions of unquestionable desirability: limiting slavery, banning child labor, prohibiting race discrimination, protecting the environment. The guidance of the Preamble has been overlooked: the Constitution exists to ensure that the national government has the authority to do all of these things which are part of a “more perfect Union” and “the general Welfare.”

Third, the Constitution exists to provide “Justice.” Long ago, the Magna Carta declared that justice requires both a fair process and fair results. In fact, even before that the Bible, in Deuteronomy 16:20, says, “Justice, justice shalt thou pursue.” Commentators have suggested that the word “justice” is repeated twice to convey the importance of both procedural and substantive fairness. In American constitutional law, this means a requirement for both procedural due process (the government must follow adequate procedures when depriving a person of life, liberty, or property) and substantive due process (the government must have adequate reasons when taking away a person’s life, liberty, or property).

Fourth, the Preamble states that the Constitution exists to “secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” The Constitution is founded to protect individual freedom. It is a society where personal liberty, not a duty to the state, is central. Interestingly, despite this commitment, the Framers of the Constitution saw no need to provide a detailed statement of rights in the Constitution they drafted. In part, this is because they thought the structure of government they were creating would ensure liberty. Also, they were afraid that enumerating some rights inherently would be taken to deny the existence of other rights that were not mentioned. They wanted liberty to be broadly protected and not confined to specific aspects of freedom mentioned in the text of the Constitution.

Equality is not mentioned in the Preamble. This is not surprising for a Constitution that explicitly protected the institution of slavery and gave women no rights. But as the Supreme Court has explained for over a half century, equality is an implicit and inherent part of liberty.

The Preamble thus does much more than tell us that the document is to be called the “Constitution” and establish a government. The Preamble describes the core values that the Constitution exists to achieve: democratic government, effective governance, justice, freedom, and equality.

The Preamble—or “Enacting Clause”—of the Constitution is more than just a pitcher’s long wind-up before delivering the pitch to home plate. It is the provision that declares the enactment of “this Constitution” by “We the People of the United States.” That declaration has important consequences for constitutional interpretation. While the Preamble does not itself confer powers and rights, it has significant implications both for how the Constitution is to be interpreted and applied and who has the power of constitutional interpretation—the two biggest overall questions of Constitutional Law.

Consider two big-picture ways that the Preamble affects how the Constitution is to be interpreted. First, the Preamble specifies that what is being enacted is “ this Constitution ”—a term that unmistakably refers to the written document itself. This is at once both obvious and hugely important. America has no “unwritten constitution.” Ours is a system of written constitutionalism —of adherence to a single, binding, authoritative, written legal text as supreme law.

This defines the territory and boundaries of legitimate constitutional argument: the enterprise of constitutional interpretation is to seek to faithfully understand, within the context of the document (including the times and places in which it was written and adopted), the words, phrases, and structural implications of the written text .

The words of the Constitution are not optional. Nor are they mere springboards or points of departure for individual (or judicial) speculation or one’s subjective preferences: where the provisions of the Constitution set forth a sufficiently clear rule for government, that rule constitutes the supreme law of the land and must be followed. By the same token, where the provisions of the Constitution do not set forth a rule—where they leave matters open—decision in such matters must remain open to the people, acting through the institutions of representative democracy. And finally, where the Constitution says nothing on a topic, it simply says nothing on the topic and cannot be used to strike down the decisions of representative government. It is not open for courts, legislatures, or any other government officials to “make up” new constitutional meanings that are not supported by the document itself.

Second, the Preamble, by stating the purposes for which the Constitution has been enacted, might well be thought to exert a very gentle interpretive “push” as to the direction in which a specific provision of the Constitution should be interpreted in a close case. The Preamble does not confer powers or rights, but the provisions that follow should be interpreted in a fashion consistent with the purposes for which they were enacted. As Justice Joseph Story put it in his treatise on the Constitution, published in 1833, using the example of the Preamble’s phrase to "provide for the common defence”:

No one can doubt, that this does not enlarge the powers of congress to pass any measures, which they may deem useful for the common defence. But suppose the terms of a given power admit of two constructions, the one more restrictive, the other more liberal, and each of them is consistent with the words . . . ; if one would promote, and the other defeat the common defence, ought not the former, upon the soundest principles of interpretation to be adopted? Are we at liberty, upon any principles of reason, or common sense, to adopt a restrictive meaning, which will defeat an avowed object of the constitution, when another equally natural and more appropriate to the object is before us? 2 Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States §462 at 445 (1833).

Finally, the Preamble has important implications for who has the ultimate power of constitutional interpretation. In modern times, it has become fashionable to identify the power of constitutional interpretation almost exclusively with the decisions of courts, and particularly the U.S. Supreme Court. And yet, while it is true that the courts legitimately possess the province of constitutional interpretation in cases that come before them, it is equally true that the other branches of the national government—and of state government, too—possess a like responsibility of faithful constitutional interpretation. None of these institutions of government, created or recognized by the Constitution, is superior to the Constitution itself. None is superior to the ultimate power of the people to adopt, amend, and interpret what is, after all, the Constitution ordained and established by “We the People of the United States.”

James Madison, one of the leading architects of the Constitution, put it best in The Federalist No. 49 :

[T]he people are the only legitimate fountain of power, and it is from them that the constitutional charter, under which the several branches of government hold their power, is derived . . . . The several departments being perfectly coordinate by the terms of their common commission, neither of them, it is evident, can pretend to an exclusive or superior right of settling the boundaries between their respective powers; and how are the encroachments of the stronger to be prevented, or the wrongs of the weaker to be redressed, without an appeal to the people themselves, who, as the grantors of the commission, can alone declare its true meaning, and enforce its observance?

The Preamble thus may have much to say—quietly—about how the Constitution is to be interpreted and who possesses the ultimate power of constitutional interpretation. It enacts a written constitution, with all that that implies. It describes the purposes for which that document was adopted, which has implications for interpreting specific provisions. And it boldly declares that the document is the enactment of, and remains the property of, the people —not the government and not any branch thereof— with the clear implication that We the People remain ultimately responsible for the proper interpretation and application of what is, in the end, our Constitution.

Further Reading:

Michael Stokes Paulsen & Luke Paulsen, The Constitution: An Introduction (2015) (Chapters 1 and 2).

Michael Stokes Paulsen, Does the Constitution Prescribe Rules for Its Own Interpretation? , 103 Nw. U. L. Rev. 857 (2009).

Michael Stokes Paulsen, The Irrepressible Myth of Marbury , 101 Mich. L. Rev. 2706 (2003).

Michael Stokes Paulsen, Captain James T. Kirk and the Enterprise of Constitutional Interpretation: Some Modest Proposals from the Twenty-Third Century, 59 Albany L. Rev. 671 (1995).

Michael Stokes Paulsen, The Most Dangerous Branch: Executive Power to Say What the Law Is, 83 Geo. L.J. 217 (1994).

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Preamble to the US Constitution

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Legal System

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- B.S., Texas A&M University

The Preamble to the U.S. Constitution summarizes the Founding Fathers’ intention to create a federal government dedicated to ensuring that “We the People” always live in a safe, peaceful, healthy, well-defended—and most of all—free nation. The preamble states:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

As the Founders intended, the Preamble has no force in law. It grants no powers to the federal or state governments, nor does it limit the scope of future government actions. As a result, the Preamble has never been cited by any federal court , including the U.S. Supreme Court , in deciding cases dealing with constitutional issues.

Also known as the “Enacting Clause,” the Preamble did not become a part of the Constitution until the final few days of the Constitutional Convention after Gouverneur Morris, who had also signed the Articles of Confederation , pressed for its inclusion. Before it was drafted, the Preamble had not been proposed or discussed on the floor of the convention.

The first version of the preamble did not refer to, “We the People of the United States…” Instead, it referred to the people of the individual states. The word “people” did not appear, and the phrase “the United States” was followed by a listing of the states as they appeared on the map from north to south. However, the Framers changed to the final version when they realized that the Constitution would go into effect as soon as nine states gave their approval, whether any of the remaining states had ratified it or not.

The Value of the Preamble

The Preamble explains why we have and need the Constitution. It also gives us the best summary we will ever have of what the Founders were considering as they hashed out the basics of the three branches of government .

In his highly acclaimed book, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States, Justice Joseph Story wrote of the Preamble, “its true office is to expound the nature and extent and application of the powers actually conferred by the Constitution.”

In addition, no less noted authority on the Constitution than Alexander Hamilton himself, in Federalist No. 84, stated that the Preamble gives us “a better recognition of popular rights than volumes of those aphorisms which make the principal figure in several of our State bills of rights, and which would sound much better in a treatise of ethics than in a constitution of government.”

James Madison , one of the leading architects of the Constitution, may have put it best when he wrote in The Federalist No. 49:

[T]he people are the only legitimate fountain of power, and it is from them that the constitutional charter, under which the several branches of government hold their power, is derived . . . .

While is common and understandable to think of the Preamble as merely a grand rhetorical “preview” of the Constitution, with no without meaningful effect, this is not entirely the case. The Preamble has been called the “Enacting Clause” or “Enabling Clause” of the Constitution, meaning that it confirms the American peoples’ freely agreed-to adoption of the Constitution—through the state ratification process—as the exclusive document conferring and defining the powers of government and the rights of citizens. However, the Framers of the Constitution clearly understood that in the legal context of 1787, preambles to legal documents were not binding provisions and thus should not be used to justify the expansion, contraction, or denial of any of the substantive terms in the remainder of the Constitution.

Most importantly, the Preamble confirmed that the Constitution was being created and enacted by the collective “People of the United States,” meaning that “We the People,” rather than the government, “own” the Constitution and are thus ultimately responsible for its continued existence and interpretation.

Understand the Preamble, Understand the Constitution

Each phrase in the Preamble helps explain the purpose of the Constitution as envisioned by the Framers.

‘We the People’

This well-known key phrase means that the Constitution incorporates the visions of all Americans and that the rights and freedoms bestowed by the document belong to all citizens of the United States of America.

‘In order to form a more perfect union’

The phrase recognizes that the old government based on the Articles of Confederation was extremely inflexible and limited in scope, making it hard for the government to respond to the changing needs of the people over time.

‘Establish justice’

The lack of a system of justice ensuring fair and equal treatment of the people had been the primary reason for the Declaration of Independence and the American Revolution against England. The Framers wanted to ensure a fair and equal system of justice for all Americans.

‘Insure domestic tranquility’

The Constitutional Convention was held shortly after Shays’ Rebellion , a bloody uprising of farmers in Massachusetts against the state caused by the monetary debt crisis at the end of the Revolutionary War. In this phrase, the Framers were responding to fears that the new government would be unable to keep peace within the nation’s borders.

‘Provide for the common defense’

The Framers were acutely aware that the new nation remained extremely vulnerable to attacks by foreign nations and that no individual state had the power to repel such attacks. Thus, the need for a unified, coordinated effort to defend the nation would always be a vital function of the U.S. federal government .

‘Promote the general welfare’

The Framers also recognized that the general well-being of the American citizens would be another key responsibility of the federal government.

‘Secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity’

The phrase confirms the Framer’s vision that the very purpose of the Constitution is to protect the nation’s blood-earned rights for liberty, justice, and freedom from a tyrannical government.

‘Ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America’

Simply stated, the Constitution and the government it embodies are created by the people, and that it is the people who give America its power.

The Preamble in Court

While the Preamble has no legal standing, the courts have used it in trying to interpret the meaning and intent of various sections of the Constitution as they apply to modern legal situations. In this way, courts have found the Preamble useful in determining the “spirit” of the Constitution.

Since the Constitution's enactment, the Supreme Court of the United States has cited the Preamble in several important decisions. However, the Court largely disclaimed the legal importance of the Preamble in making those decisions. As Justice Story noted in his Commentaries, “the Preamble never can be resorted to, to enlarge the powers confided to the general government or any of its departments.”

The Supreme Court subsequently endorsed Justice Story's view of the Preamble, holding in Jacobson v. Massachusetts that, "while the Constitution's introductory paragraph indicates the general purposes for which the people ordained and established the Constitution, it has never been regarded by the Court as the source of any substantive power conferred on the federal government.” While the Supreme Court has not viewed the Preamble as having any direct, substantive legal effect, the Court has referenced its broad general rules to confirm and reinforce its interpretation of other provisions within the Constitution. As such, while the Preamble does not have any specific legal status, Justice Story's observation that the true purpose of the Preamble is to enlarge on the nature, and extent, and application of the powers actually conferred by the Constitution.

More broadly, while the Preamble may have little significance in a court of law, the preface to the Constitution remains an important part of the nation's constitutional dialogue, inspiring and fostering broader understandings of the American system of government.

Whose Government is it and What is it For?

The Preamble contains what may be the most important three words in our nation’s history: “We the People.” Those three words, along with the brief balance of the Preamble, establish the very basis of our system of “ federalism ,” under which the states and central government are granted both shared and exclusive powers, but only with the approval of “We the people.”

Compare the Constitution’s Preamble to its counterpart in the Constitution’s predecessor, the Articles of Confederation. In that compact, the states alone formed “a firm league of friendship, for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare” and agreed to protect each other “against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretence whatever.”

Clearly, the Preamble sets the Constitution apart from the Articles of Confederation as being an agreement among the people, rather than the states, and placing an emphasis on rights and freedoms above the military protection of the individual states.

- Fast Facts About the U.S. Constitution

- Basic Structure of the US Government

- Who Were the Anti-Federalists?

- What Is Federalism? Definition and How It Works in the US

- The Implied Powers of Congress

- The 10th Amendment: Text, Origins, and Meaning

- The U.S. Constitution

- What Is the "Necessary and Proper" Clause in the US Constitution?

- Ninth Amendment Supreme Court Cases

- Overview of United States Government and Politics

- Federalism and the United States Constitution

- What Is Constitution Day in the United States?

- The Powers of Congress

- Due Process of Law in the US Constitution

- 14th Amendment Summary

- What Is Judicial Review?

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

The Preamble’s origins predate the Constitutional Convention—preambles to legal documents were relatively commonplace at the time of the Nation’s Founding. In several English laws that undergird American understandings of constitutional rights, including the Petition of Rights of 1628, 1 Footnote 3 Car. 1, c. 1 . the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, 2 Footnote 31 Car. 2, c. 2 . the Bill of Rights of 1689, 3 Footnote 1 W. & M. c. 2 . and the Act of Settlement of 1701, 4 Footnote 12 & 13 Will. 3, c. 2 . the British Parliament included prefatory text that explained the law’s objects and historical impetus. The tradition of a legal preamble continued in the New World. The Declarations and Resolves of the First Continental Congress in 1774 included a preamble noting the many grievances the thirteen colonies held against British rule. 5 Footnote The Declarations and Resolves of the First Continental Congress (Oct. 14, 1774) , reprinted in 1 Sources and Documents of the U.S. Constitutions: National Documents 1492–1800 , at 291 (William F. Swindler ed., 1982) [hereinafter Sources & Documents ]. Building on this document, in perhaps the only preamble that rivals the fame of the Constitution’s opening lines, the Declaration of Independence of 1776 announced: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The Declaration then listed a series of complaints against King George III, before culminating in a formal declaration of the colonies’ independence from the British crown. 6 Footnote See The Declaration of Independence para. 1 (U.S. 1776) , reprinted in Sources & Documents , supra note 5, at 321 . Moreover, several state constitutions at the time of the founding contained introductory text that echoed many of the themes of the 1776 Declaration. 7 Footnote See, e.g. , Mass. Const. of 1780 , pmbl. (stating the “objects” of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 were “to secure the existence of the body-politic, to protect it, and to furnish the individuals who compose it, with the power of enjoying in safety and tranquillity their natural rights, and blessings of life” and, to this end, a government was created “for Ourselves and Posterity” ); N.H. Const. of 1776 , pmbl. (creating a government “for the preservation of peace and good order, and for the security of the lives and properties of the inhabitants of this colony” ); N.Y. Const. of 1777 , pmbl. (creating a government “best calculated to secure the rights and liberties of the good people of this State” ); Pa. Const. of 1776 , pmbl. (stating the government was created for the “protection of the community as such, and to enable the individuals who compose it to enjoy their natural rights” ); Vt. Const. of 1786 , pmbl. (establishing a constitution to “best promote the general happiness of the people of this State, and their posterity” ); Va. Const. of 1776 , Bill of Rights, pmbl. (stating “the representatives of the good people of Virginia” created their bill of rights, which “pertain to them and their posterity” ). The Articles of Confederation that preceded the Constitution had their own preamble—authored by “we the undersigned Delegates of the States” —declaring the “Confederation and perpetual Union” of the thirteen former colonies. 8 Footnote See Articles of Confederation of 1781 , pmbl. , reprinted in Sources & Documents , supra note 5, at 335 .

While the concept of a preamble was well-known to the Constitution’s Framers, little debate occurred at the Philadelphia Convention with respect to whether the Constitution required prefatory text or as to the particular text agreed upon by the delegates. For the first two months of the Convention, no proposal was made to include a preamble in the Constitution’s text. 9 Footnote See Morris D. Forkosch , Who Are the “People” in the Preamble to the Constitution? , 19 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 644 , 688–89 & n.187 (1968) (examining various records of the first two months of the Philadelphia Convention and concluding that “the Preamble was completely ignored” in the early debates). In late July 1787, the Convention’s Committee of Detail was formed to prepare a draft of a constitution, and during those deliberations, Committee member Edmund Randolph of Virginia suggested for the first time that “[a] preamble seems proper.” 10 Footnote See 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 , at 137 (Max Farrand ed., 1966) [hereinafter Farrand’s Records ]. Importantly, however, Randolph considered the Constitution to be a legal, as opposed to a philosophical document, and rejected the idea of having a lengthy “display of theory” to explain “the ends of government and human politics” akin to the Declaration of Independence’s preamble or those of several state constitutions. 11 Footnote Id. Articulating what would ultimately become the Preamble’s underlying rationale, Randolph instead argued that any prefatory text to the Constitution should be limited to explaining why the government under the Articles of Confederation was insufficient and why the “establishment of a supreme legislative[,] executive[,] and judiciary” was necessary. 12 Footnote Id.

The initial draft of the Constitution’s Preamble was, however, fairly brief and did not specify the Constitution’s objectives. As released by the Committee of Detail on August 6, 1787, this draft stated: “We the People of the States of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia, do ordain, declare and establish the following Constitution for the Government of Ourselves and our Posterity.” 13 Footnote Id. at 177 . While this draft was passed unanimously by the delegates, 14 Footnote Id. at 193 . the Preamble underwent significant changes after the draft Constitution was referred to the Committee of Style on September 8, 1787. Perhaps with the understanding that the inclusion of all thirteen of the states in the Preamble was more precatory than realistic, 15 Footnote See Charles Warren , The Making of the Constitution 394 (1928) (arguing it was “necessary to eliminate from the preamble the names of the specific States; for it could not be known, at the date of the signing of the Preamble and the rest of the Constitution by the delegates, just which of the thirteen States would ratify” ). the Committee of Style, led by Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania, 16 Footnote It is generally acknowledged that the Preamble’s author was Gouverneur Morris, as the language from the federal preamble echoes that of Morris’s home state’s Constitution. See Carl Van Doren , The Great Rehearsal: The Story of the Making and Ratifying of the Constitution of the United States 160 (1948) ; see also Richard Brookhiser , Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris, the Rake Who Wrote the Constitution 90 (2003) (claiming the “Preamble was the one part of the Constitution that Morris wrote from scratch” ). replaced the opening phrase of the Constitution with the now-familiar introduction “We, the People of the United States.” 17 Footnote Farrand’s Records , supra note 10, at 590 . Moreover, the Preamble, as altered by Morris, listed six broad goals for the Constitution: “to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty.” 18 Footnote Id. The record from the Philadelphia Convention is silent, however, as to why the Committee of Style altered the Preamble, and there is no evidence of any objection to the changes the Committee made to the final version of the Preamble. 19 Footnote See Dennis J. Mahoney , Preamble , in 3 Encyclopedia of the American Constitution 1435 (Leonard W. Levy et al. eds., 1986) (noting “there is no record of any objection to the Preamble as it was reported by the committee” ).

While the Preamble did not provoke any further discussion in the Philadelphia Convention, the first words of the Constitution factored prominently in the ratifying debates that followed. 20 Footnote See Akhil Reed Amar , America’s Constitution: A Biography 7 (2005) ( “In the extraordinary extended and inclusive ratification process . . . Americans regularly found themselves discussing the Preamble itself.” ). For instance, Anti-Federalists, led by Patrick Henry of Virginia, criticized the opening lines of the Constitution at the Virginia ratifying convention:

Who authorized them to speak the language of We, the people, instead of We, the States? States are the characteristics and the soul of a confederation. If the states be not the agents of this compact, it must be one great, consolidated, national government, of the people of all the states. 21 Footnote See Jonathan Elliot , 3 Elliot’s Debates on the Federal Constitution 22 (2d. ed. 1996) .

In response, Edmund Pendleton replied: “[W]ho but the people can delegate powers? Who but the people have a right to form government?” 22 Footnote See id. at 37 . Similarly, John Marshall declared that both state and federal “governments derive [their] powers from the people, and each was to act according to the powers given it.” 23 Footnote Id. at 419 . Echoing these themes at the Pennsylvania Ratification Convention, James Wilson defended the “We the People” language, arguing that “all authority is derived from the people” and that the Preamble merely announces the inoffensive principle that “people have a right to do what they please with regard to the government.” 24 Footnote Id. at 434–35 .

The Preamble also figured into the written debates over whether to ratify the Constitution. For instance, countering criticisms that the Constitution lacked a bill of rights, Alexander Hamilton in the Federalist No. 84 quoted the Preamble, arguing it obviated any need for an enumeration of rights. 25 Footnote See The Federalist No. 84 (Alexander Hamilton) ( “Here is a better recognition of popular rights, than volumes of those aphorisms which make the principal figure in several of our State bills of rights, and which would sound much better in a treatise of ethics than in a constitution of government.” ). An Anti-Federalist pamphlet authored under the pseudonym Brutus, noting the Preamble’s references to a “more perfect union” and “establish[ment] [of] justice,” argued that the Constitution would result in the invalidation of state laws that interfered with these objectives, resulting in the abolition of “all inferior governments” and giving “the general one complete legislative, executive, and judicial powers to every purpose.” 26 Footnote See Brutus No. XII (Feb. 7 & 14, 1788) , reprinted in The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-Federalist Speeches, Articles and Letters During the Struggle Over Ratification, Part Two: January to August 1788 , at 174 (Bernard Bailyn ed., 1993) . While not disputing the need for national union in the wake of their experience under the Articles of Confederation, 27 Footnote See The Federalist No. 5 (John Jay) ( “[W]eakness and divisions at home would invite dangers from abroad; and that nothing would tend more to secure us from them than union, strength, and good government within ourselves.” ). supporters of the Constitution rejected the notion that their proposed government was truly a “ national one” because “its jurisdiction extends to certain enumerated objects only, and leaves to the several States a residuary and inviolable sovereignty over all other objects.” 28 Footnote See The Federalist No. 39 (James Madison) .

In particular, those writing in support of the Constitution’s ratification cited the Preamble’s language. The Constitution’s goals of “establish[ing] justice” and “secur[ing] the blessings of liberty” —prompted by the perception that state governments at the time of the framing were violating individual liberties, including property rights, through the tyranny of popular majorities 29 Footnote See Gordon S. Wood , The Creation of the American Republic 1776–1787 , at 409–13 (1969) (noting that the Framer’s experience of government under the Articles of Confederation, including the famous debtors’ uprising called Shay’s Rebellion, led to fear that, unless checks were imposed on majority rule, the debtor-majority might infringe the rights of the creditor-minority). —was a central theme of the Federalist Papers . For instance, in the Federalist No. 51 James Madison described justice as “the end of government . . . [and] civil society” that “has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” 30 Footnote See The Federalist No. 51 (James Madison) . Similarly, the Constitution’s goals of “ensur[ing] domestic tranquility” and “provid[ing] for the common defence” were noted in the Federalist Papers later attributed to John Jay and Alexander Hamilton, who described both the foreign threats and interstate conflicts that faced a disunited America as an argument for ratification. 31 Footnote See The Federalist Nos. 2–5 (John Jay) (describing foreign dangers posed to America); see id. Nos. 6–8 , at 21–39 (Alexander Hamilton) (describing concerns over domestic factions and insurrection in America). Finally, the Preamble’s references to the “common defence” and the “general welfare,” which mirrored the language of the Articles of Confederation, 32 Footnote See Articles of Confederation of 1781 , art. III , reprinted in Sources & Documents , supra note 5, at 335 ( “The said States hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretense whatever.” ); id. art. VIII , reprinted in Sources & Documents , supra note 5, at 338 ( “All charges of war, and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defense or general welfare, and allowed by the United States in Congress assembled, shall be defrayed out of a common treasury, which shall be supplied by the several States in proportion to the value of all land within each State, granted or surveyed for any person, as such land and the buildings and improvements thereon shall be estimated according to such mode as the United States in Congress assembled, shall from time to time direct and appoint.” ). were understood by Framers like James Madison to underscore that the new federal government under the Constitution would generally provide for the national good better than the government it was replacing. 33 Footnote See Letter from James Madison to Andrew Stevenson (Nov. 17, 1830) , reprinted in 2 The Founders’ Constitution 453, 456 (Philip B. Kurland & Ralph Lerner eds., 1987) (contending that the terms “common defence” and “general welfare,” “copied from the Articles of Confederation, were regarded in the new as in the old instrument, . . . as general terms, explained and limited by the subjoined specifications” ). For example, calling the Confederation’s efforts to provide for the “common defense and general welfare” an “ill-founded and illusory” experiment, Alexander Hamilton in the Federalist No. 23 argued for a central government with the “full power to levy troops; to build and equip fleets; . . . to raise revenues” for an army and navy; and to otherwise manage the “national interest.” 34 Footnote See The Federalist No. 23 (Alexander Hamilton) .

Nonetheless, there is no historical evidence suggesting the Constitution’s Framers conceived of a Preamble with any substantive legal effect, such as granting power to the new government or conferring rights to those subject to the federal government. 35 Footnote See I Joseph Story , Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States § 462 (1833) . Instead, the founding generation appeared to view the Constitution’s prefatory text as generally providing the foundation for the text that followed. 36 Footnote See id. (concluding the Preamble’s “true office is to expound the nature, and extent, and application of the powers actually conferred by the constitution” ); see also 1 Annals of Cong. 717 –19 (1789) (noting several Members of the First Congress described the Preamble as comprising “no part of the Constitution” ); Letter from James Madison to Robert S. Garnett (Feb. 11, 1824) , in 9 The Writings of James Madison 176–77 (Gaillard Hunt ed., 1910) ( “The general terms or phrases used in the introductory propositions . . . were never meant to be inserted in their loose form in the text of the Constitution. Like resolutions preliminary to legal enactments it was understood by all, that they were to be reduced by proper limitations and specifications . . . .” ). In so doing, the Preamble ultimately reflects three critical understandings that the Framers had about the Constitution. First, the Preamble specified the source of the federal government’s sovereignty as being “the People.” 37 Footnote See Story , supra note 35, § 463 ( “We have the strongest assurances, that this preamble was not adopted as a mere formulary; but as a solemn promulgation of a fundamental fact, vital to the character and operations of the government. The obvious object was to substitute a government of the people, for a confederacy of states; a constitution for a compact.” ). Second, the Constitution’s introduction articulated six broad purposes, all grounded in the historical experiences of being governed under the Articles of Confederation. 38 Footnote Farrand’s Records , supra note 10, at 137 ( “[T]he object of our preamble ought to be to briefly declare, that the present federal government is insufficient to the general happiness [and] that the conviction of this fact gave birth to this convention.” ). Finally, and perhaps most critically, the Preamble, with its conclusion that “this Constitution” was established for “ourselves and our Posterity,” underscored that, unlike the constitutions in Great Britain and elsewhere at the time of the founding, the American Constitution was a written and permanent document that would serve as a stable guide for the new nation. 39 Footnote See Erwin Chemerinsky & Michael Stokes Paulsen , Common Interpretation: The Preamble, Interactive Constitution , Const. Ctr. (last visited Nov. 1, 2018), https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution/interpretation/preamble-ic/interps/37 ( “[T]he Preamble declares that what the people have ordained and established is ‘this Constitution'—referring, obviously enough, to the written document that the Preamble introduces. . . . The U.S. Constitution contrasts with the arrangement of nations like Great Britain, whose ‘constitution’ is a looser collection of written and unwritten traditions constituting the established practice over time. America has a written constitution, not an unwritten one.” ); see also Michael Stokes Paulsen , Does the Constitution Prescribe Rules for Its Own Interpretation? , 103 Nw. U. L. Rev. 857 , 869 (2009) ( “'[T]his Constitution’ means, each time it is invoked, the written document.” ).

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

The Preamble to the Constitution: A Close Reading Lesson

The first page of the United States Constitution, opening with the Preamble.

National Archives

"[T]he preamble of a statute is a key to open the mind of the makers, as to the mischiefs, which are to be remedied, and the objects, which are to be accomplished by the provisions of the statute." — Justice Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution

The Preamble is the introduction to the United States Constitution, and it serves two central purposes. First, it states the source from which the Constitution derives its authority: the sovereign people of the United States. Second, it sets forth the ends that the Constitution and the government that it establishes are meant to serve.

Gouverneur Morris, the man the Constitutional Convention entrusted with drafting the final version of the document, put into memorable language the principles of government negotiated and formulated at the Convention.

As Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story points out in the passage quoted above, the Preamble captures some of the hopes and fears of the framers for the American republic. By reading their words closely and comparing them with those of the Articles of Confederation, students can in turn access “the mind of the makers” as to “mischiefs” to be “remedied” and “objects” to be accomplished.

In this lesson, students will practice close reading of the Preamble and of related historic documents, illuminating the ideas that the framers of the Constitution set forth about the foundation and the aims of government.

Guiding Questions

How does the language of the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution reflect historical circumstances and ideas about government?

To what extent is the U.S. Constitution a finished document?

Learning Objectives

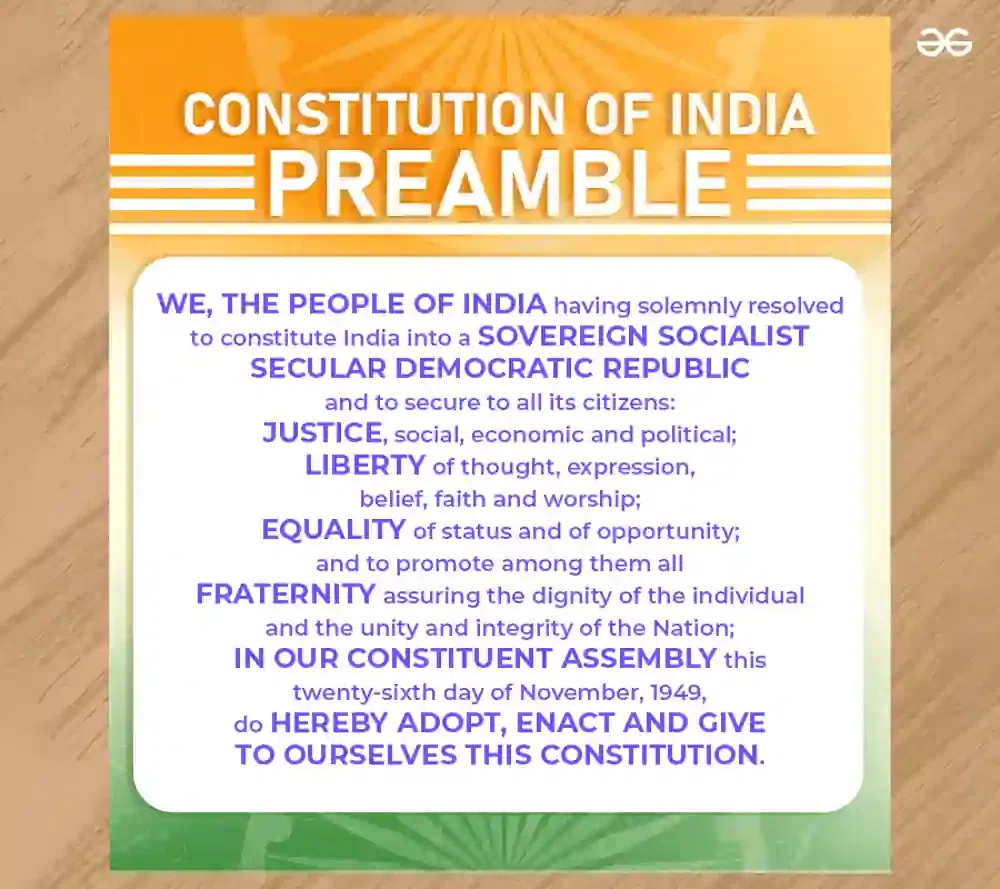

Compare the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution with the statement of purposes included in the Articles of Confederation.

Explain the source of authority and the goals of the U.S. Constitution as identified in the Preamble.

Evaluate the fundamental values and principles expressed in the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution.

Lesson Plan Details

The Articles of Confederation was established in 1781 as the nation’s “first constitution.” Each state governed itself through elected representatives, and the state representatives in turn elected a central government. But the national government was so feeble and its powers so limited that this system proved unworkable. Congress could not impose taxes to cover national expenses, which meant the Confederation was ineffectual. And because all 13 colonies had to ratify amendments, one state’s refusal prevented any reform. By 1786 many far-sighted American leaders saw the need for a more powerful central authority; a convention was called to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787.

The Constitutional Convention met for four months. Among the chief points at issue were how much power to allow the central government and then, how to balance and check that power to prevent government abuse.

As debate at the Philadelphia Convention drew to a close, Gouverneur Morris was assigned to the Committee of Style and given the task of wording the Constitution by the committee’s members. Through thoughtful word choice, Morris attempted to put the fundamental principles agreed on by the framers into memorable language.

By looking carefully at the words of the Preamble, comparing it with the similar passages in the opening of the Articles of Confederation, and relating them to historical circumstances as well as widely shared political principles such as those found in the Declaration of Independence, students can see how the Preamble reflects the hope and fears of the Framers.

For background information about the history and interpretation of the Constitution, see the following resources:

- A basic and conveniently organized introduction to the historical context is “ To Form a More Perfect Union ,” available in Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774–1789 from the Library of Congress .

- Another historical summary is " Constitution of the United States—A History ," available in America's Founding Documents from the National Archives .

- The Interactive Constitution , a digital resource that incorporates commentary from constitutional scholars, is available from the National Constitution Center .

- The American Constitution: A Documentary Record , available via The Avalon Project at the Yale Law School , offers an extensive archive of documents critical to the development of the Constitution.

This lesson is one of a series of complementary EDSITEment lesson plans for intermediate-level students about the foundations of our government. Consider adapting them for your class in the following order:

- The Argument of the Declaration of Independence

- (Present lesson plan)

- Balancing Three Branches at Once: Our System of Checks and Balances:

- The First Amendment: What's Fair in a Free Country

NCSS. D2.Civ.3.9-12. Analyze the impact of constitutions, laws, treaties, and international agreements on the maintenance of national and international order.

NCSS.D2.Civ.4.9-12. Explain how the U.S. Constitution establishes a system of government that has powers, responsibilities, and limits that have changed over time and that are still contested.

NCSS. D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS. D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS. D2.His.5.9-12. Analyze how historical contexts shaped and continue to shape people’s perspectives.

NCSS. D2.His.6.9-12. Analyze the ways in which the perspectives of those writing history shaped the history that they produced.

NCSS. D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1. Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.2. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.6. Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts).

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.6-8.10. By the end of grade 8, read and comprehend history/social studies texts in the grades 6-8 text complexity band independently and proficiently.

The following resources are included with this lesson plan to be used in conjunction with the student activities and for teacher preparation.

- Activity 1. Student Worksheet

- Activity 2. Teachers Guide to the Preamble

- Activity 2. Graphic Organizer

Review the Graphic Organizer for Activity 2, which contains the Preamble to the Constitution along with the opening passages of the Articles of Confederation and the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence (both from OurDocuments.gov ), and make copies for the class.

Activity 1. Why Government?

To help students understand the enormous task facing the Americans, pose a hypothetical situation to the class:

Imagine that on a field trip to a wilderness area or sailing trip to a small, remote island, you all became stranded without any communication with parents, the school, or other adults and had little hope of being rescued in the foreseeable future. The area where you’re marooned can provide the basic necessities of food, shelter, and water, but you will have to work together to survive.

Encourage students to think about the next steps they need to take with a general discussion about such matters as:

- Are you better working together or alone? (Be open to their ideas, but point out reasons why they have a better chance at survival if they work together.)

- How will you work together?

- How will you create rules?

- Who will be responsible for leading the group to help all survive?

- How will they be chosen?

- How will you deal with people in the group who may not be following the rules?

Distribute the Student Worksheet handout , which contains the seven questions below. [ Note: These questions are related to the seven phrases from the Preamble but this relationship in not given on the handout. ]

Divide students into small groups and have each group brainstorm a list of things they would have to consider in developing its own government. [ Note: You can have all groups answer all seven questions or assign one question for each group.] Ask students to be detailed in their answers and be able to support their recommendations.

- How will you make sure everyone sticks together and works towards the common goal of getting rescued? (form a more perfect union)

- How will you make sure that anyone who feels unfairly treated will have a place to air complaints? (establishing justice)

- How will you make sure that people can have peace and quiet? (ensuring domestic tranquility)

- How will you make sure that group members will help if outsiders arrive who threaten your group? (providing for the common defense)

- How will you make sure that the improvements you make on the island (such as shelters, fireplaces and the like) will be used fairly? (promoting the general welfare)

- How will you make sure that group members will be free to do what they want as long as it doesn't hurt anyone else? (securing the blessing of liberty to ourselves)

- How will you make sure that the rules and organizations you develop protect future generations? (securing the blessing of liberty to our posterity)

While students are working in their groups, write or project the following seven headers on the front board in this order:

- Secure the Blessings of Liberty for our Posterity,

- Promote the General Welfare,

- Establish Justice,

- Form a more perfect Union,

- Insure Domestic Tranquility,

- Secure the Blessings of Liberty to Ourselves, and

- Provide for the Common Defense

After the groups have finished discussing their questions, have them meet as a class. First ask them to identify which question (by number) from their handout goes with which section of the Preamble of the U.S. Constitution you’ve listed on the front board. Next, have students share their recommendations to the questions and allow other groups to comment, add, or disagree with the recommendations made.

Exit Ticket:

Encourage class discussion of the following questions:

- Having just released themselves from Britain's monarchy, what would the colonists fear most?

- Judging from some of the complaints the colonists had against Britain, what might be some of their concerns for any future government?

As in the hypothetical situation described above, what decisions would the colonists have to make about forming a new government out of 13 colonies which, until 1776, had basically been running themselves independently?

Activity 2. What the Preamble Says

Review the Teachers' Guide to the Preamble , which parses each of the phrases of the Preamble and contrasts them with the equivalent passages in the Articles and the Declaration. Teachers can use this guide as a source for a short lecture before the activity and as a kind of answer sheet for the activity.

In this activity, students investigate the Preamble to the Constitution by comparing and contrasting it with the opening language of the Articles of Confederation. They will:

- understand how the Preamble of the Constitution (in outlining the goals of the new government under the Constitution) was written with the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation in mind, aiming to create “a more perfect union,” and

- understand how the Preamble drew its justification from the principles outlined in the Declaration of Independence.

The aim of this activity is to show students, through a close reading of the Preamble, how its style and content reflect some of the aspirations of the framers for the future of republican government in America.

[ Note: teachers should define “diction,” “connotation,” and “denotation” to the students before beginning to ask students to differentiate between language in the two documents. ]

Distribute copies of the Graphic Organizer and questions to all students and have them complete it in their small groups (or individually as a homework assignment).

Have one or two students or groups of students summarize their conclusions concerning the critical differences between the Articles and the Preamble, citing the sources of these documents as referents.

Have students answer the following in a brief, well-constructed essay:

Using the ideas and information presented in this lesson, explain how the wording and structure of the Preamble demonstrate that the Constitution is different from the Articles of Confederation.

Note: For an excellent example of what can be inferred from the language and structure of the Preamble, teachers should review and model this passage by Professor Garret Epps from “ The Poetry of the Preamble ” on the Oxford University Press blog (2013):

“Form, establish, insure, provide, promote, secure”: these are strong verbs that signify governmental power, not restraint. “We the people” are to be bound—into a stronger union. We will be protected against internal disorder—that is, against ourselves—and against foreign enemies. The “defence” to be provided is “common,” general, spread across the country. The Constitution will establish justice; it will promote the “general” welfare; it will secure our liberties. The new government, it would appear, is not the enemy of liberty but its chief agent and protector.

Students could be asked whether they agree or disagree with the above interpretation. They should be expected to provide evidence-based arguments for their position.

The aspirational rhetoric of the Preamble has inspired various social movements throughout our nation’s history. In particular, two 19th-century developments come to mind: the struggles for abolitionism and women's suffrage. Examples of oratory from each movement are provided below. In response to one of these excerpts, students can write a short essay about how the words of the Preamble affected the relevant movement.

- Students should ascertain what the Preamble meant to the movement and how it was used to make an appeal to the nation. The essay might address the question of how and why those such as Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony, who at their time were excluded from the full range of rights and liberties ensured by the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, responded to the principles expressed in the Preamble.

- Students should then argue either for or against the interpretation of the Preamble advanced in the excerpt, drawing from the knowledge gained in this lesson.

Be sure that the essay has a strong thesis (a non-obvious, debatable proposition about the Preamble) that students support with evidence from the texts used in this lesson.

Example 1. Frederick Douglass, “ What to the Slave is the Fourth of July ?” (1852)

Fellow-citizens! there is no matter in respect to which, the people of the North have allowed themselves to be so ruinously imposed upon, as that of the pro-slavery character of the Constitution. In that instrument I hold there is neither warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT. Read its preamble, consider its purposes. Is slavery among them? Is it at the gateway? or is it in the temple? It is neither.

Example 2. Susan B. Anthony, “ Is It a Crime for a U.S. Citizen to Vote? ” ( 1873)

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people—women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government—the ballot.

Materials & Media

Preamble close reading: activity 1 student worksheet, preamble close reading: activity 2 graphic organizer, preamble close reading: activity 2 teachers guide, related on edsitement, a day for the constitution, commemorating constitution day, the constitutional convention of 1787.

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal of Constitutional Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. how to talk about preambles, 3. the american preamble, 4. the legal status of preambles, 5. integrative and disintegrative power of preambles, 6. conclusion.

- < Previous

The preamble in constitutional interpretation

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Liav Orgad, The preamble in constitutional interpretation, International Journal of Constitutional Law , Volume 8, Issue 4, October 2010, Pages 714–738, https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mor010

- Permissions Icon Permissions

From Plato's Laws through common law and until modern legal systems, preambles to constitutions have played an important role in law and policy making. Through a qualitative analysis of the legal status of preambles in different common law and civil law countries, the article highlights a recent trend in comparative constitutional law: the growing use of preambles in constitutional adjudication and constitutional design. The article also explores the theory of preambles and their functions. It examines the legal status of the U.S. preamble and shows how the U.S. preamble remains the most neglected section in American constitutional theory. The article then presents a typology for determining the legal status of preambles: a symbolic preamble, an interpretive preamble, and a substantive preamble. While focusing on Macedonia, Israel, Australia, and the Treaty of Lisbon, the article discusses the sociological function of preambles in top-down and bottom-up constitutional designs.

The preamble to the United States Constitution has become a legend. The phrase “We the people of the United States” and the remaining forty-five words of the preamble are the most well-known part of the Constitution, and the section that has had the greatest effect on the constitutions of other countries. And yet, the preamble remains a neglected subject in the study of American constitutional theory and receives scant attention in the literature. Questions such as: what is a preamble to a constitution?; what role does it play in constitutional adjudication and constitutional design?; and why do states add a preamble to the constitution? have been seldom asked or answered.

This article highlights the legal and social functions of preambles. First, it discusses the growing use of preambles in constitutional interpretation. In many countries, the preamble has been used, increasingly, to constitutionalize unenumerated rights. A global survey of the function of preambles shows a growing trend toward its having greater binding force—either independently, as a substantive source of rights, or combined with other constitutional provisions, or as a guide for constitutional interpretation. The courts rely, more and more, on preambles as sources of law. While in some countries this development is not new and dates back several decades, in others it is a recent development. From a global perspective, the U.S. preamble, which generally does not enjoy binding legal status, remains the exception rather than the rule.

Second, the article discusses one of the interesting merits of a preamble: its integrative power. A preamble is the part of the constitution that best reflects the constitutional understandings of the framers, what Carl Schmitt calls the “fundamental political decisions.” Its terms, thus, have far-reaching social effects. Consequently, preambles recently have been added or amended in some countries either due to a popular demand (a bottom-up change) or because of a government-led constitutional design (a top-down change). The article illustrates the potential of a consensual preamble to unite, or a disputable preamble to divide, a people. It emphasizes the sociological reason why it is necessary to carefully consider what is written in the text of the preamble, in particular, in those cases in which the preamble is granted binding legal force.

Section 1 explains the concept of preamble based on qualitative research of the preambles in fifty common law and civil law countries. Section 2 traces the origins of the U.S. preamble and its legal status. Section 3 presents a typology of three legal functions of preambles: the ceremonial-symbolic, in which the preamble serves to consolidate national identity but lacks binding legal force; the interpretive, in which the preamble is granted a guiding role in statutory and constitutional interpretation; and the substantive, in which the preamble serves as an independent source for constitutional rights. Section 4 demonstrates the importance of consensual preambles, sketches the risks inherent in nonconsensual preambles, and describes the benefits and disadvantages in the process of designing a preamble. Focusing on Macedonia, Israel, Australia, and the Treaty of Lisbon, the article examines the social function of preambles in top-down and bottom-up designs and suggests some lessons for a future design of a preamble.

What is a preamble to a constitution and how can it be classified? In formal terms , a preamble constitutes the introduction to the constitution and usually bears the formal heading “Preamble” or some alternative, equivalent title, 1 while in other cases it appears without a heading. The formal classification provides a simple and technical identification of a preamble. Alongside a formal classification, it is possible to identify a preamble through its content. In substantive terms , a preamble does not require a specific location in the constitution but, rather, specific content. 2 It presents the history behind the constitution's enactment, as well as the nation's core principles and values. 3

Analysis of a nonrepresentative sample of fifty democratic countries revealed that most have included a formal preamble in their constitutions: 4 thirty-seven countries have a preamble (74 percent) 5 while thirteen countries do not (26 percent). 6 Countries that do not have a formal preamble often include introductory articles that may be regarded, in substantive terms, as a preamble. 7 A preamble is, thus, a common constitutional feature. Moreover, most of the countries that have adopted a constitution in recent years, particularly in Eastern and Central Europe, have included a preamble.

The content of preambles can be classified into five categories.

The Sovereign. Most preambles specify the source of sovereignty. In some cases, sovereign power rests with the people (“we the people of …”). 8 This is a relatively neutral term with which most of the population can usually identify. Another phrase relates to the source of sovereignty as stemming from a particular nation (the “Lithuanian Nation,” the “Spanish Nation,” and the like). This terminology emphasizes a specific national group and is less neutral. 9 Some preambles combine a reference to the people with a reference to representative bodies; others refer only to representative bodies; while others make no reference to a sovereign authority. In federations and unions, the preamble often identifies the constituent states—and their peoples—as the source of sovereignty. 10

Historical Narratives . Preambles include, typically, historical narratives of a state, a nation, or a people, telling specific stories that are rooted in language, heritage, and tradition. These stories shape the common identity (“we”). The reference is often to past events that influenced the establishment of the state. The South African preamble, for example, declares that the people of South Africa “recognise the injustices of our past,” and “honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land.” The preamble to the Chinese Constitution notes that “China is one of the countries with the longest histories in the world” and details, at great length, Chinese history and the nation's achievements. The Turkish preamble mentions that the Turkish Constitution is established “in line with the concept of nationalism outlined and the reforms and principles” introduced by the republic's founder Atatürk. In Eastern and Central Europe—in countries such as Croatia, Estonia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine—the preambles celebrate the nations’ struggles for independence and self-determination.

Supreme Goals. Preambles often outline a society's fundamental goals. These may be universal objectives, such as the advancement of justice, fraternity, and human rights; economic goals, such as nurturing a socialist agenda or advancing a free market economy; or others, such as maintaining the union. 11 These goals tend to be abstract ideas, such as happiness or well-being. The preamble to the Constitution of Japan, for instance, is peace-loving (“never again shall we be visited with the horrors of war … desire peace for all time”), while the preambles to the Constitutions of the Philippines and of Turkey stress love.

National Identity . Preambles usually contain statements about the national creed. Understanding the constitutional faith of each country, and its constitutional philosophy, cannot be complete without reading its preamble. Frequently, preambles include an additional element about future aspirations and may include a commitment to resolve disputes by peaceful means, to abide by the principles of the UN Charter, or to further national aspirations as stated in a declaration of independence. 12 These statements often refer to inalienable rights, such as liberty or human dignity.

God or Religion. A preamble may include references to God. Some preambles emphasize God's supremacy, such as the preambles to the Canadian Charter (“the supremacy of God”) or the Swiss Constitution (“in the Name of Almighty God”). 13 Other preambles refer to a religion: the Greek preamble refers to the Holy Trinity; 14 in the Irish preamble, the Holy Trinity is mentioned as “our final end” and a source of authority toward which all actions of “men and states must be referred.” 15 Conversely, the preamble may emphasize the separation of state and religion or the state's secular character. 16

While common characteristics can be identified, each preamble has its own distinguishing features. Preambles come in various lengths, 17 harmonize with or contradict the body of the constitution, and may be enacted together with the body of the constitution as well as in a later constitutional moment.