Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

Published on August 21, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023.

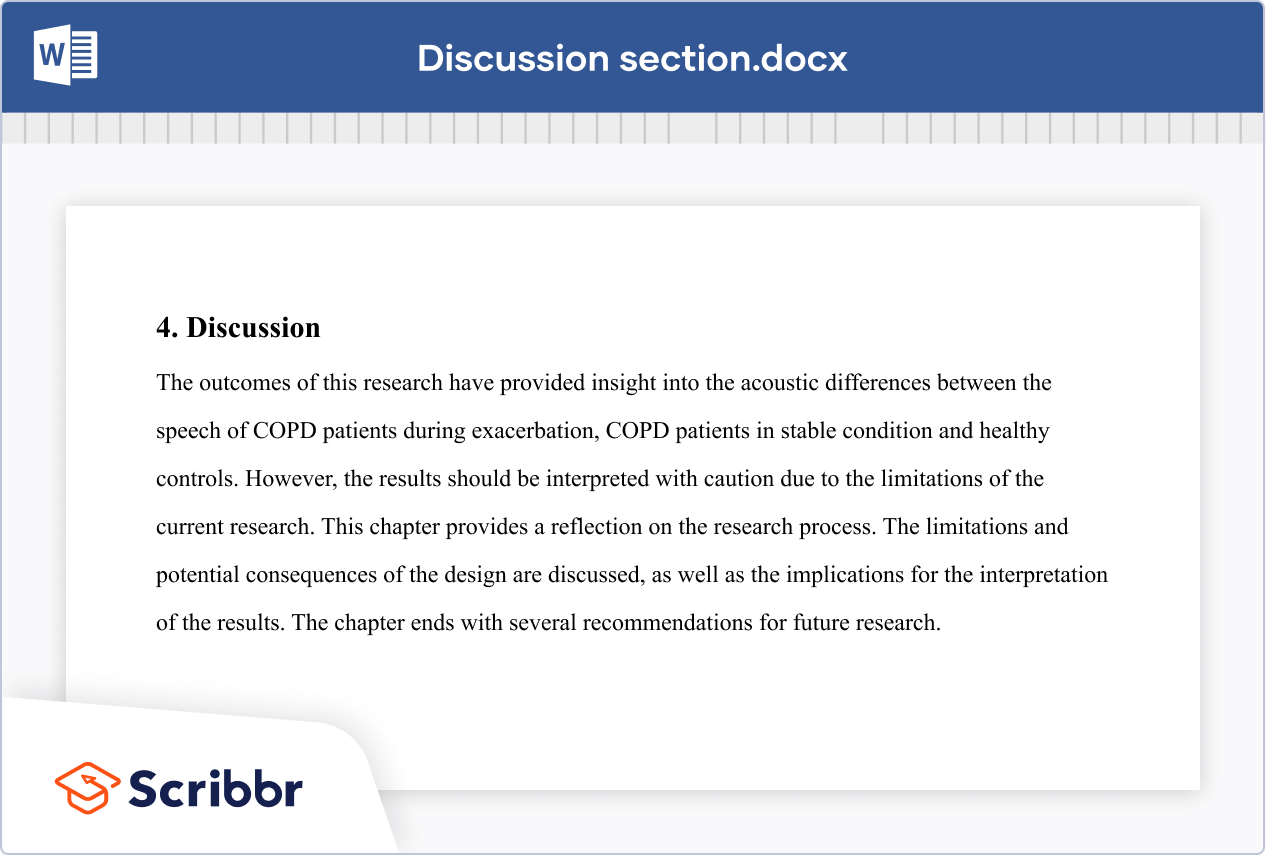

The discussion section is where you delve into the meaning, importance, and relevance of your results .

It should focus on explaining and evaluating what you found, showing how it relates to your literature review and paper or dissertation topic , and making an argument in support of your overall conclusion. It should not be a second results section.

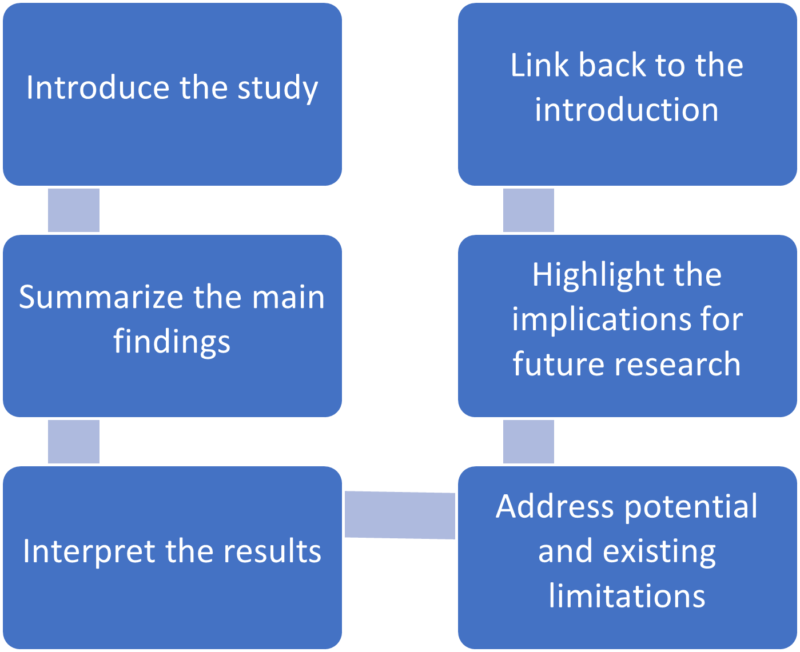

There are different ways to write this section, but you can focus your writing around these key elements:

- Summary : A brief recap of your key results

- Interpretations: What do your results mean?

- Implications: Why do your results matter?

- Limitations: What can’t your results tell us?

- Recommendations: Avenues for further studies or analyses

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What not to include in your discussion section, step 1: summarize your key findings, step 2: give your interpretations, step 3: discuss the implications, step 4: acknowledge the limitations, step 5: share your recommendations, discussion section example, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about discussion sections.

There are a few common mistakes to avoid when writing the discussion section of your paper.

- Don’t introduce new results: You should only discuss the data that you have already reported in your results section .

- Don’t make inflated claims: Avoid overinterpretation and speculation that isn’t directly supported by your data.

- Don’t undermine your research: The discussion of limitations should aim to strengthen your credibility, not emphasize weaknesses or failures.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Start this section by reiterating your research problem and concisely summarizing your major findings. To speed up the process you can use a summarizer to quickly get an overview of all important findings. Don’t just repeat all the data you have already reported—aim for a clear statement of the overall result that directly answers your main research question . This should be no more than one paragraph.

Many students struggle with the differences between a discussion section and a results section . The crux of the matter is that your results sections should present your results, and your discussion section should subjectively evaluate them. Try not to blend elements of these two sections, in order to keep your paper sharp.

- The results indicate that…

- The study demonstrates a correlation between…

- This analysis supports the theory that…

- The data suggest that…

The meaning of your results may seem obvious to you, but it’s important to spell out their significance for your reader, showing exactly how they answer your research question.

The form of your interpretations will depend on the type of research, but some typical approaches to interpreting the data include:

- Identifying correlations , patterns, and relationships among the data

- Discussing whether the results met your expectations or supported your hypotheses

- Contextualizing your findings within previous research and theory

- Explaining unexpected results and evaluating their significance

- Considering possible alternative explanations and making an argument for your position

You can organize your discussion around key themes, hypotheses, or research questions, following the same structure as your results section. Alternatively, you can also begin by highlighting the most significant or unexpected results.

- In line with the hypothesis…

- Contrary to the hypothesized association…

- The results contradict the claims of Smith (2022) that…

- The results might suggest that x . However, based on the findings of similar studies, a more plausible explanation is y .

As well as giving your own interpretations, make sure to relate your results back to the scholarly work that you surveyed in the literature review . The discussion should show how your findings fit with existing knowledge, what new insights they contribute, and what consequences they have for theory or practice.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Do your results support or challenge existing theories? If they support existing theories, what new information do they contribute? If they challenge existing theories, why do you think that is?

- Are there any practical implications?

Your overall aim is to show the reader exactly what your research has contributed, and why they should care.

- These results build on existing evidence of…

- The results do not fit with the theory that…

- The experiment provides a new insight into the relationship between…

- These results should be taken into account when considering how to…

- The data contribute a clearer understanding of…

- While previous research has focused on x , these results demonstrate that y .

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Even the best research has its limitations. Acknowledging these is important to demonstrate your credibility. Limitations aren’t about listing your errors, but about providing an accurate picture of what can and cannot be concluded from your study.

Limitations might be due to your overall research design, specific methodological choices , or unanticipated obstacles that emerged during your research process.

Here are a few common possibilities:

- If your sample size was small or limited to a specific group of people, explain how generalizability is limited.

- If you encountered problems when gathering or analyzing data, explain how these influenced the results.

- If there are potential confounding variables that you were unable to control, acknowledge the effect these may have had.

After noting the limitations, you can reiterate why the results are nonetheless valid for the purpose of answering your research question.

- The generalizability of the results is limited by…

- The reliability of these data is impacted by…

- Due to the lack of data on x , the results cannot confirm…

- The methodological choices were constrained by…

- It is beyond the scope of this study to…

Based on the discussion of your results, you can make recommendations for practical implementation or further research. Sometimes, the recommendations are saved for the conclusion .

Suggestions for further research can lead directly from the limitations. Don’t just state that more studies should be done—give concrete ideas for how future work can build on areas that your own research was unable to address.

- Further research is needed to establish…

- Future studies should take into account…

- Avenues for future research include…

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

In the discussion , you explore the meaning and relevance of your research results , explaining how they fit with existing research and theory. Discuss:

- Your interpretations : what do the results tell us?

- The implications : why do the results matter?

- The limitation s : what can’t the results tell us?

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

In a thesis or dissertation, the discussion is an in-depth exploration of the results, going into detail about the meaning of your findings and citing relevant sources to put them in context.

The conclusion is more shorter and more general: it concisely answers your main research question and makes recommendations based on your overall findings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/discussion/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a results section | tips & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 8. The Discussion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The purpose of the discussion section is to interpret and describe the significance of your findings in relation to what was already known about the research problem being investigated and to explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research. The discussion will always connect to the introduction by way of the research questions or hypotheses you posed and the literature you reviewed, but the discussion does not simply repeat or rearrange the first parts of your paper; the discussion clearly explains how your study advanced the reader's understanding of the research problem from where you left them at the end of your review of prior research.

Annesley, Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Peacock, Matthew. “Communicative Moves in the Discussion Section of Research Articles.” System 30 (December 2002): 479-497.

Importance of a Good Discussion

The discussion section is often considered the most important part of your research paper because it:

- Most effectively demonstrates your ability as a researcher to think critically about an issue, to develop creative solutions to problems based upon a logical synthesis of the findings, and to formulate a deeper, more profound understanding of the research problem under investigation;

- Presents the underlying meaning of your research, notes possible implications in other areas of study, and explores possible improvements that can be made in order to further develop the concerns of your research;

- Highlights the importance of your study and how it can contribute to understanding the research problem within the field of study;

- Presents how the findings from your study revealed and helped fill gaps in the literature that had not been previously exposed or adequately described; and,

- Engages the reader in thinking critically about issues based on an evidence-based interpretation of findings; it is not governed strictly by objective reporting of information.

Annesley Thomas M. “The Discussion Section: Your Closing Argument.” Clinical Chemistry 56 (November 2010): 1671-1674; Bitchener, John and Helen Basturkmen. “Perceptions of the Difficulties of Postgraduate L2 Thesis Students Writing the Discussion Section.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5 (January 2006): 4-18; Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

These are the general rules you should adopt when composing your discussion of the results :

- Do not be verbose or repetitive; be concise and make your points clearly

- Avoid the use of jargon or undefined technical language

- Follow a logical stream of thought; in general, interpret and discuss the significance of your findings in the same sequence you described them in your results section [a notable exception is to begin by highlighting an unexpected result or a finding that can grab the reader's attention]

- Use the present verb tense, especially for established facts; however, refer to specific works or prior studies in the past tense

- If needed, use subheadings to help organize your discussion or to categorize your interpretations into themes

II. The Content

The content of the discussion section of your paper most often includes :

- Explanation of results : Comment on whether or not the results were expected for each set of findings; go into greater depth to explain findings that were unexpected or especially profound. If appropriate, note any unusual or unanticipated patterns or trends that emerged from your results and explain their meaning in relation to the research problem.

- References to previous research : Either compare your results with the findings from other studies or use the studies to support a claim. This can include re-visiting key sources already cited in your literature review section, or, save them to cite later in the discussion section if they are more important to compare with your results instead of being a part of the general literature review of prior research used to provide context and background information. Note that you can make this decision to highlight specific studies after you have begun writing the discussion section.

- Deduction : A claim for how the results can be applied more generally. For example, describing lessons learned, proposing recommendations that can help improve a situation, or highlighting best practices.

- Hypothesis : A more general claim or possible conclusion arising from the results [which may be proved or disproved in subsequent research]. This can be framed as new research questions that emerged as a consequence of your analysis.

III. Organization and Structure

Keep the following sequential points in mind as you organize and write the discussion section of your paper:

- Think of your discussion as an inverted pyramid. Organize the discussion from the general to the specific, linking your findings to the literature, then to theory, then to practice [if appropriate].

- Use the same key terms, narrative style, and verb tense [present] that you used when describing the research problem in your introduction.

- Begin by briefly re-stating the research problem you were investigating and answer all of the research questions underpinning the problem that you posed in the introduction.

- Describe the patterns, principles, and relationships shown by each major findings and place them in proper perspective. The sequence of this information is important; first state the answer, then the relevant results, then cite the work of others. If appropriate, refer the reader to a figure or table to help enhance the interpretation of the data [either within the text or as an appendix].

- Regardless of where it's mentioned, a good discussion section includes analysis of any unexpected findings. This part of the discussion should begin with a description of the unanticipated finding, followed by a brief interpretation as to why you believe it appeared and, if necessary, its possible significance in relation to the overall study. If more than one unexpected finding emerged during the study, describe each of them in the order they appeared as you gathered or analyzed the data. As noted, the exception to discussing findings in the same order you described them in the results section would be to begin by highlighting the implications of a particularly unexpected or significant finding that emerged from the study, followed by a discussion of the remaining findings.

- Before concluding the discussion, identify potential limitations and weaknesses if you do not plan to do so in the conclusion of the paper. Comment on their relative importance in relation to your overall interpretation of the results and, if necessary, note how they may affect the validity of your findings. Avoid using an apologetic tone; however, be honest and self-critical [e.g., in retrospect, had you included a particular question in a survey instrument, additional data could have been revealed].

- The discussion section should end with a concise summary of the principal implications of the findings regardless of their significance. Give a brief explanation about why you believe the findings and conclusions of your study are important and how they support broader knowledge or understanding of the research problem. This can be followed by any recommendations for further research. However, do not offer recommendations which could have been easily addressed within the study. This would demonstrate to the reader that you have inadequately examined and interpreted the data.

IV. Overall Objectives

The objectives of your discussion section should include the following: I. Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings

Briefly reiterate the research problem or problems you are investigating and the methods you used to investigate them, then move quickly to describe the major findings of the study. You should write a direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results, usually in one paragraph.

II. Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important

No one has thought as long and hard about your study as you have. Systematically explain the underlying meaning of your findings and state why you believe they are significant. After reading the discussion section, you want the reader to think critically about the results and why they are important. You don’t want to force the reader to go through the paper multiple times to figure out what it all means. If applicable, begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most significant or unanticipated finding first, then systematically review each finding. Otherwise, follow the general order you reported the findings presented in the results section.

III. Relate the Findings to Similar Studies

No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for your research. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps to support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your study differs from other research about the topic. Note that any significant or unanticipated finding is often because there was no prior research to indicate the finding could occur. If there is prior research to indicate this, you need to explain why it was significant or unanticipated. IV. Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings

It is important to remember that the purpose of research in the social sciences is to discover and not to prove . When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations for the study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. This is especially important when describing the discovery of significant or unanticipated findings.

V. Acknowledge the Study’s Limitations

It is far better for you to identify and acknowledge your study’s limitations than to have them pointed out by your professor! Note any unanswered questions or issues your study could not address and describe the generalizability of your results to other situations. If a limitation is applicable to the method chosen to gather information, then describe in detail the problems you encountered and why. VI. Make Suggestions for Further Research

You may choose to conclude the discussion section by making suggestions for further research [as opposed to offering suggestions in the conclusion of your paper]. Although your study can offer important insights about the research problem, this is where you can address other questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or highlight hidden issues that were revealed as a result of conducting your research. You should frame your suggestions by linking the need for further research to the limitations of your study [e.g., in future studies, the survey instrument should include more questions that ask..."] or linking to critical issues revealed from the data that were not considered initially in your research.

NOTE: Besides the literature review section, the preponderance of references to sources is usually found in the discussion section . A few historical references may be helpful for perspective, but most of the references should be relatively recent and included to aid in the interpretation of your results, to support the significance of a finding, and/or to place a finding within a particular context. If a study that you cited does not support your findings, don't ignore it--clearly explain why your research findings differ from theirs.

V. Problems to Avoid

- Do not waste time restating your results . Should you need to remind the reader of a finding to be discussed, use "bridge sentences" that relate the result to the interpretation. An example would be: “In the case of determining available housing to single women with children in rural areas of Texas, the findings suggest that access to good schools is important...," then move on to further explaining this finding and its implications.

- As noted, recommendations for further research can be included in either the discussion or conclusion of your paper, but do not repeat your recommendations in the both sections. Think about the overall narrative flow of your paper to determine where best to locate this information. However, if your findings raise a lot of new questions or issues, consider including suggestions for further research in the discussion section.

- Do not introduce new results in the discussion section. Be wary of mistaking the reiteration of a specific finding for an interpretation because it may confuse the reader. The description of findings [results section] and the interpretation of their significance [discussion section] should be distinct parts of your paper. If you choose to combine the results section and the discussion section into a single narrative, you must be clear in how you report the information discovered and your own interpretation of each finding. This approach is not recommended if you lack experience writing college-level research papers.

- Use of the first person pronoun is generally acceptable. Using first person singular pronouns can help emphasize a point or illustrate a contrasting finding. However, keep in mind that too much use of the first person can actually distract the reader from the main points [i.e., I know you're telling me this--just tell me!].

Analyzing vs. Summarizing. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University; Discussion. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Hess, Dean R. "How to Write an Effective Discussion." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004); Kretchmer, Paul. Fourteen Steps to Writing to Writing an Effective Discussion Section. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sauaia, A. et al. "The Anatomy of an Article: The Discussion Section: "How Does the Article I Read Today Change What I Will Recommend to my Patients Tomorrow?” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 74 (June 2013): 1599-1602; Research Limitations & Future Research . Lund Research Ltd., 2012; Summary: Using it Wisely. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Discussion. Writing in Psychology course syllabus. University of Florida; Yellin, Linda L. A Sociology Writer's Guide . Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, 2009.

Writing Tip

Don’t Over-Interpret the Results!

Interpretation is a subjective exercise. As such, you should always approach the selection and interpretation of your findings introspectively and to think critically about the possibility of judgmental biases unintentionally entering into discussions about the significance of your work. With this in mind, be careful that you do not read more into the findings than can be supported by the evidence you have gathered. Remember that the data are the data: nothing more, nothing less.

MacCoun, Robert J. "Biases in the Interpretation and Use of Research Results." Annual Review of Psychology 49 (February 1998): 259-287; Ward, Paulet al, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Expertise . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Write Two Results Sections!

One of the most common mistakes that you can make when discussing the results of your study is to present a superficial interpretation of the findings that more or less re-states the results section of your paper. Obviously, you must refer to your results when discussing them, but focus on the interpretation of those results and their significance in relation to the research problem, not the data itself.

Azar, Beth. "Discussing Your Findings." American Psychological Association gradPSYCH Magazine (January 2006).

Yet Another Writing Tip

Avoid Unwarranted Speculation!

The discussion section should remain focused on the findings of your study. For example, if the purpose of your research was to measure the impact of foreign aid on increasing access to education among disadvantaged children in Bangladesh, it would not be appropriate to speculate about how your findings might apply to populations in other countries without drawing from existing studies to support your claim or if analysis of other countries was not a part of your original research design. If you feel compelled to speculate, do so in the form of describing possible implications or explaining possible impacts. Be certain that you clearly identify your comments as speculation or as a suggestion for where further research is needed. Sometimes your professor will encourage you to expand your discussion of the results in this way, while others don’t care what your opinion is beyond your effort to interpret the data in relation to the research problem.

- << Previous: Using Non-Textual Elements

- Next: Limitations of the Study >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

- 4 minute read

Table of Contents

The discussion section in scientific manuscripts might be the last few paragraphs, but its role goes far beyond wrapping up. It’s the part of an article where scientists talk about what they found and what it means, where raw data turns into meaningful insights. Therefore, discussion is a vital component of the article.

An excellent discussion is well-organized. We bring to you authors a classic 6-step method for writing discussion sections, with examples to illustrate the functions and specific writing logic of each step. Take a look at how you can impress journal reviewers with a concise and focused discussion section!

Discussion frame structure

Conventionally, a discussion section has three parts: an introductory paragraph, a few intermediate paragraphs, and a conclusion¹. Please follow the steps below:

1.Introduction—mention gaps in previous research¹⁻ ²

Here, you orient the reader to your study. In the first paragraph, it is advisable to mention the research gap your paper addresses.

Example: This study investigated the cognitive effects of a meat-only diet on adults. While earlier studies have explored the impact of a carnivorous diet on physical attributes and agility, they have not explicitly addressed its influence on cognitively intense tasks involving memory and reasoning.

2. Summarizing key findings—let your data speak ¹⁻ ²

After you have laid out the context for your study, recapitulate some of its key findings. Also, highlight key data and evidence supporting these findings.

Example: We found that risk-taking behavior among teenagers correlates with their tendency to invest in cryptocurrencies. Risk takers in this study, as measured by the Cambridge Gambling Task, tended to have an inordinately higher proportion of their savings invested as crypto coins.

3. Interpreting results—compare with other papers¹⁻²

Here, you must analyze and interpret any results concerning the research question or hypothesis. How do the key findings of your study help verify or disprove the hypothesis? What practical relevance does your discovery have?

Example: Our study suggests that higher daily caffeine intake is not associated with poor performance in major sporting events. Athletes may benefit from the cardiovascular benefits of daily caffeine intake without adversely impacting performance.

Remember, unlike the results section, the discussion ideally focuses on locating your findings in the larger body of existing research. Hence, compare your results with those of other peer-reviewed papers.

Example: Although Miller et al. (2020) found evidence of such political bias in a multicultural population, our findings suggest that the bias is weak or virtually non-existent among politically active citizens.

4. Addressing limitations—their potential impact on the results¹⁻²

Discuss the potential impact of limitations on the results. Most studies have limitations, and it is crucial to acknowledge them in the intermediary paragraphs of the discussion section. Limitations may include low sample size, suspected interference or noise in data, low effect size, etc.

Example: This study explored a comprehensive list of adverse effects associated with the novel drug ‘X’. However, long-term studies may be needed to confirm its safety, especially regarding major cardiac events.

5. Implications for future research—how to explore further¹⁻²

Locate areas of your research where more investigation is needed. Concluding paragraphs of the discussion can explain what research will likely confirm your results or identify knowledge gaps your study left unaddressed.

Example: Our study demonstrates that roads paved with the plastic-infused compound ‘Y’ are more resilient than asphalt. Future studies may explore economically feasible ways of producing compound Y in bulk.

6. Conclusion—summarize content¹⁻²

A good way to wind up the discussion section is by revisiting the research question mentioned in your introduction. Sign off by expressing the main findings of your study.

Example: Recent observations suggest that the fish ‘Z’ is moving upriver in many parts of the Amazon basin. Our findings provide conclusive evidence that this phenomenon is associated with rising sea levels and climate change, not due to elevated numbers of invasive predators.

A rigorous and concise discussion section is one of the keys to achieving an excellent paper. It serves as a critical platform for researchers to interpret and connect their findings with the broader scientific context. By detailing the results, carefully comparing them with existing research, and explaining the limitations of this study, you can effectively help reviewers and readers understand the entire research article more comprehensively and deeply¹⁻² , thereby helping your manuscript to be successfully published and gain wider dissemination.

In addition to keeping this writing guide, you can also use Elsevier Language Services to improve the quality of your paper more deeply and comprehensively. We have a professional editing team covering multiple disciplines. With our profound disciplinary background and rich polishing experience, we can significantly optimize all paper modules including the discussion, effectively improve the fluency and rigor of your articles, and make your scientific research results consistent, with its value reflected more clearly. We are always committed to ensuring the quality of papers according to the standards of top journals, improving the publishing efficiency of scientific researchers, and helping you on the road to academic success. Check us out here !

Type in wordcount for Standard Total: USD EUR JPY Follow this link if your manuscript is longer than 12,000 words. Upload

References:

- Masic, I. (2018). How to write an efficient discussion? Medical Archives , 72(3), 306. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2018.72.306-307

- Şanlı, Ö., Erdem, S., & Tefik, T. (2014). How to write a discussion section? Urology Research & Practice , 39(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2013.049

Navigating “Chinglish” Errors in Academic English Writing

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

You may also like.

Submission 101: What format should be used for academic papers?

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Write the Discussion Section of a Research Paper

The discussion section of a research paper analyzes and interprets the findings, provides context, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future research directions.

Updated on September 15, 2023

Structure your discussion section right, and you’ll be cited more often while doing a greater service to the scientific community. So, what actually goes into the discussion section? And how do you write it?

The discussion section of your research paper is where you let the reader know how your study is positioned in the literature, what to take away from your paper, and how your work helps them. It can also include your conclusions and suggestions for future studies.

First, we’ll define all the parts of your discussion paper, and then look into how to write a strong, effective discussion section for your paper or manuscript.

Discussion section: what is it, what it does

The discussion section comes later in your paper, following the introduction, methods, and results. The discussion sets up your study’s conclusions. Its main goals are to present, interpret, and provide a context for your results.

What is it?

The discussion section provides an analysis and interpretation of the findings, compares them with previous studies, identifies limitations, and suggests future directions for research.

This section combines information from the preceding parts of your paper into a coherent story. By this point, the reader already knows why you did your study (introduction), how you did it (methods), and what happened (results). In the discussion, you’ll help the reader connect the ideas from these sections.

Why is it necessary?

The discussion provides context and interpretations for the results. It also answers the questions posed in the introduction. While the results section describes your findings, the discussion explains what they say. This is also where you can describe the impact or implications of your research.

Adds context for your results

Most research studies aim to answer a question, replicate a finding, or address limitations in the literature. These goals are first described in the introduction. However, in the discussion section, the author can refer back to them to explain how the study's objective was achieved.

Shows what your results actually mean and real-world implications

The discussion can also describe the effect of your findings on research or practice. How are your results significant for readers, other researchers, or policymakers?

What to include in your discussion (in the correct order)

A complete and effective discussion section should at least touch on the points described below.

Summary of key findings

The discussion should begin with a brief factual summary of the results. Concisely overview the main results you obtained.

Begin with key findings with supporting evidence

Your results section described a list of findings, but what message do they send when you look at them all together?

Your findings were detailed in the results section, so there’s no need to repeat them here, but do provide at least a few highlights. This will help refresh the reader’s memory and help them focus on the big picture.

Read the first paragraph of the discussion section in this article (PDF) for an example of how to start this part of your paper. Notice how the authors break down their results and follow each description sentence with an explanation of why each finding is relevant.

State clearly and concisely

Following a clear and direct writing style is especially important in the discussion section. After all, this is where you will make some of the most impactful points in your paper. While the results section often contains technical vocabulary, such as statistical terms, the discussion section lets you describe your findings more clearly.

Interpretation of results

Once you’ve given your reader an overview of your results, you need to interpret those results. In other words, what do your results mean? Discuss the findings’ implications and significance in relation to your research question or hypothesis.

Analyze and interpret your findings

Look into your findings and explore what’s behind them or what may have caused them. If your introduction cited theories or studies that could explain your findings, use these sources as a basis to discuss your results.

For example, look at the second paragraph in the discussion section of this article on waggling honey bees. Here, the authors explore their results based on information from the literature.

Unexpected or contradictory results

Sometimes, your findings are not what you expect. Here’s where you describe this and try to find a reason for it. Could it be because of the method you used? Does it have something to do with the variables analyzed? Comparing your methods with those of other similar studies can help with this task.

Context and comparison with previous work

Refer to related studies to place your research in a larger context and the literature. Compare and contrast your findings with existing literature, highlighting similarities, differences, and/or contradictions.

How your work compares or contrasts with previous work

Studies with similar findings to yours can be cited to show the strength of your findings. Information from these studies can also be used to help explain your results. Differences between your findings and others in the literature can also be discussed here.

How to divide this section into subsections

If you have more than one objective in your study or many key findings, you can dedicate a separate section to each of these. Here’s an example of this approach. You can see that the discussion section is divided into topics and even has a separate heading for each of them.

Limitations

Many journals require you to include the limitations of your study in the discussion. Even if they don’t, there are good reasons to mention these in your paper.

Why limitations don’t have a negative connotation

A study’s limitations are points to be improved upon in future research. While some of these may be flaws in your method, many may be due to factors you couldn’t predict.

Examples include time constraints or small sample sizes. Pointing this out will help future researchers avoid or address these issues. This part of the discussion can also include any attempts you have made to reduce the impact of these limitations, as in this study .

How limitations add to a researcher's credibility

Pointing out the limitations of your study demonstrates transparency. It also shows that you know your methods well and can conduct a critical assessment of them.

Implications and significance

The final paragraph of the discussion section should contain the take-home messages for your study. It can also cite the “strong points” of your study, to contrast with the limitations section.

Restate your hypothesis

Remind the reader what your hypothesis was before you conducted the study.

How was it proven or disproven?

Identify your main findings and describe how they relate to your hypothesis.

How your results contribute to the literature

Were you able to answer your research question? Or address a gap in the literature?

Future implications of your research

Describe the impact that your results may have on the topic of study. Your results may show, for instance, that there are still limitations in the literature for future studies to address. There may be a need for studies that extend your findings in a specific way. You also may need additional research to corroborate your findings.

Sample discussion section

This fictitious example covers all the aspects discussed above. Your actual discussion section will probably be much longer, but you can read this to get an idea of everything your discussion should cover.

Our results showed that the presence of cats in a household is associated with higher levels of perceived happiness by its human occupants. These findings support our hypothesis and demonstrate the association between pet ownership and well-being.

The present findings align with those of Bao and Schreer (2016) and Hardie et al. (2023), who observed greater life satisfaction in pet owners relative to non-owners. Although the present study did not directly evaluate life satisfaction, this factor may explain the association between happiness and cat ownership observed in our sample.

Our findings must be interpreted in light of some limitations, such as the focus on cat ownership only rather than pets as a whole. This may limit the generalizability of our results.

Nevertheless, this study had several strengths. These include its strict exclusion criteria and use of a standardized assessment instrument to investigate the relationships between pets and owners. These attributes bolster the accuracy of our results and reduce the influence of confounding factors, increasing the strength of our conclusions. Future studies may examine the factors that mediate the association between pet ownership and happiness to better comprehend this phenomenon.

This brief discussion begins with a quick summary of the results and hypothesis. The next paragraph cites previous research and compares its findings to those of this study. Information from previous studies is also used to help interpret the findings. After discussing the results of the study, some limitations are pointed out. The paper also explains why these limitations may influence the interpretation of results. Then, final conclusions are drawn based on the study, and directions for future research are suggested.

How to make your discussion flow naturally

If you find writing in scientific English challenging, the discussion and conclusions are often the hardest parts of the paper to write. That’s because you’re not just listing up studies, methods, and outcomes. You’re actually expressing your thoughts and interpretations in words.

- How formal should it be?

- What words should you use, or not use?

- How do you meet strict word limits, or make it longer and more informative?

Always give it your best, but sometimes a helping hand can, well, help. Getting a professional edit can help clarify your work’s importance while improving the English used to explain it. When readers know the value of your work, they’ll cite it. We’ll assign your study to an expert editor knowledgeable in your area of research. Their work will clarify your discussion, helping it to tell your story. Find out more about AJE Editing.

Adam Goulston, PsyD, MS, MBA, MISD, ELS

Science Marketing Consultant

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Discussion Section for a Research Paper

We’ve talked about several useful writing tips that authors should consider while drafting or editing their research papers. In particular, we’ve focused on figures and legends , as well as the Introduction , Methods , and Results . Now that we’ve addressed the more technical portions of your journal manuscript, let’s turn to the analytical segments of your research article. In this article, we’ll provide tips on how to write a strong Discussion section that best portrays the significance of your research contributions.

What is the Discussion section of a research paper?

In a nutshell, your Discussion fulfills the promise you made to readers in your Introduction . At the beginning of your paper, you tell us why we should care about your research. You then guide us through a series of intricate images and graphs that capture all the relevant data you collected during your research. We may be dazzled and impressed at first, but none of that matters if you deliver an anti-climactic conclusion in the Discussion section!

Are you feeling pressured? Don’t worry. To be honest, you will edit the Discussion section of your manuscript numerous times. After all, in as little as one to two paragraphs ( Nature ‘s suggestion based on their 3,000-word main body text limit), you have to explain how your research moves us from point A (issues you raise in the Introduction) to point B (our new understanding of these matters). You must also recommend how we might get to point C (i.e., identify what you think is the next direction for research in this field). That’s a lot to say in two paragraphs!

So, how do you do that? Let’s take a closer look.

What should I include in the Discussion section?

As we stated above, the goal of your Discussion section is to answer the questions you raise in your Introduction by using the results you collected during your research . The content you include in the Discussions segment should include the following information:

- Remind us why we should be interested in this research project.

- Describe the nature of the knowledge gap you were trying to fill using the results of your study.

- Don’t repeat your Introduction. Instead, focus on why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place.

- Mainly, you want to remind us of how your research will increase our knowledge base and inspire others to conduct further research.

- Clearly tell us what that piece of missing knowledge was.

- Answer each of the questions you asked in your Introduction and explain how your results support those conclusions.

- Make sure to factor in all results relevant to the questions (even if those results were not statistically significant).

- Focus on the significance of the most noteworthy results.

- If conflicting inferences can be drawn from your results, evaluate the merits of all of them.

- Don’t rehash what you said earlier in the Results section. Rather, discuss your findings in the context of answering your hypothesis. Instead of making statements like “[The first result] was this…,” say, “[The first result] suggests [conclusion].”

- Do your conclusions line up with existing literature?

- Discuss whether your findings agree with current knowledge and expectations.

- Keep in mind good persuasive argument skills, such as explaining the strengths of your arguments and highlighting the weaknesses of contrary opinions.

- If you discovered something unexpected, offer reasons. If your conclusions aren’t aligned with current literature, explain.

- Address any limitations of your study and how relevant they are to interpreting your results and validating your findings.

- Make sure to acknowledge any weaknesses in your conclusions and suggest room for further research concerning that aspect of your analysis.

- Make sure your suggestions aren’t ones that should have been conducted during your research! Doing so might raise questions about your initial research design and protocols.

- Similarly, maintain a critical but unapologetic tone. You want to instill confidence in your readers that you have thoroughly examined your results and have objectively assessed them in a way that would benefit the scientific community’s desire to expand our knowledge base.

- Recommend next steps.

- Your suggestions should inspire other researchers to conduct follow-up studies to build upon the knowledge you have shared with them.

- Keep the list short (no more than two).

How to Write the Discussion Section

The above list of what to include in the Discussion section gives an overall idea of what you need to focus on throughout the section. Below are some tips and general suggestions about the technical aspects of writing and organization that you might find useful as you draft or revise the contents we’ve outlined above.

Technical writing elements

- Embrace active voice because it eliminates the awkward phrasing and wordiness that accompanies passive voice.

- Use the present tense, which should also be employed in the Introduction.

- Sprinkle with first person pronouns if needed, but generally, avoid it. We want to focus on your findings.

- Maintain an objective and analytical tone.

Discussion section organization

- Keep the same flow across the Results, Methods, and Discussion sections.

- We develop a rhythm as we read and parallel structures facilitate our comprehension. When you organize information the same way in each of these related parts of your journal manuscript, we can quickly see how a certain result was interpreted and quickly verify the particular methods used to produce that result.

- Notice how using parallel structure will eliminate extra narration in the Discussion part since we can anticipate the flow of your ideas based on what we read in the Results segment. Reducing wordiness is important when you only have a few paragraphs to devote to the Discussion section!

- Within each subpart of a Discussion, the information should flow as follows: (A) conclusion first, (B) relevant results and how they relate to that conclusion and (C) relevant literature.

- End with a concise summary explaining the big-picture impact of your study on our understanding of the subject matter. At the beginning of your Discussion section, you stated why this particular study was needed to fill the gap you noticed and why that gap needed filling in the first place. Now, it is time to end with “how your research filled that gap.”

Discussion Part 1: Summarizing Key Findings

Begin the Discussion section by restating your statement of the problem and briefly summarizing the major results. Do not simply repeat your findings. Rather, try to create a concise statement of the main results that directly answer the central research question that you stated in the Introduction section . This content should not be longer than one paragraph in length.

Many researchers struggle with understanding the precise differences between a Discussion section and a Results section . The most important thing to remember here is that your Discussion section should subjectively evaluate the findings presented in the Results section, and in relatively the same order. Keep these sections distinct by making sure that you do not repeat the findings without providing an interpretation.

Phrase examples: Summarizing the results

- The findings indicate that …

- These results suggest a correlation between A and B …

- The data present here suggest that …

- An interpretation of the findings reveals a connection between…

Discussion Part 2: Interpreting the Findings

What do the results mean? It may seem obvious to you, but simply looking at the figures in the Results section will not necessarily convey to readers the importance of the findings in answering your research questions.

The exact structure of interpretations depends on the type of research being conducted. Here are some common approaches to interpreting data:

- Identifying correlations and relationships in the findings

- Explaining whether the results confirm or undermine your research hypothesis

- Giving the findings context within the history of similar research studies

- Discussing unexpected results and analyzing their significance to your study or general research

- Offering alternative explanations and arguing for your position

Organize the Discussion section around key arguments, themes, hypotheses, or research questions or problems. Again, make sure to follow the same order as you did in the Results section.

Discussion Part 3: Discussing the Implications

In addition to providing your own interpretations, show how your results fit into the wider scholarly literature you surveyed in the literature review section. This section is called the implications of the study . Show where and how these results fit into existing knowledge, what additional insights they contribute, and any possible consequences that might arise from this knowledge, both in the specific research topic and in the wider scientific domain.

Questions to ask yourself when dealing with potential implications:

- Do your findings fall in line with existing theories, or do they challenge these theories or findings? What new information do they contribute to the literature, if any? How exactly do these findings impact or conflict with existing theories or models?

- What are the practical implications on actual subjects or demographics?

- What are the methodological implications for similar studies conducted either in the past or future?

Your purpose in giving the implications is to spell out exactly what your study has contributed and why researchers and other readers should be interested.

Phrase examples: Discussing the implications of the research

- These results confirm the existing evidence in X studies…

- The results are not in line with the foregoing theory that…

- This experiment provides new insights into the connection between…

- These findings present a more nuanced understanding of…

- While previous studies have focused on X, these results demonstrate that Y.

Step 4: Acknowledging the limitations

All research has study limitations of one sort or another. Acknowledging limitations in methodology or approach helps strengthen your credibility as a researcher. Study limitations are not simply a list of mistakes made in the study. Rather, limitations help provide a more detailed picture of what can or cannot be concluded from your findings. In essence, they help temper and qualify the study implications you listed previously.

Study limitations can relate to research design, specific methodological or material choices, or unexpected issues that emerged while you conducted the research. Mention only those limitations directly relate to your research questions, and explain what impact these limitations had on how your study was conducted and the validity of any interpretations.

Possible types of study limitations:

- Insufficient sample size for statistical measurements

- Lack of previous research studies on the topic

- Methods/instruments/techniques used to collect the data

- Limited access to data

- Time constraints in properly preparing and executing the study

After discussing the study limitations, you can also stress that your results are still valid. Give some specific reasons why the limitations do not necessarily handicap your study or narrow its scope.

Phrase examples: Limitations sentence beginners

- “There may be some possible limitations in this study.”

- “The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations.”

- “The first limitation is the…The second limitation concerns the…”

- “The empirical results reported herein should be considered in the light of some limitations.”

- “This research, however, is subject to several limitations.”

- “The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is…”

- “Nonetheless, these results must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be borne in mind.”

Discussion Part 5: Giving Recommendations for Further Research

Based on your interpretation and discussion of the findings, your recommendations can include practical changes to the study or specific further research to be conducted to clarify the research questions. Recommendations are often listed in a separate Conclusion section , but often this is just the final paragraph of the Discussion section.

Suggestions for further research often stem directly from the limitations outlined. Rather than simply stating that “further research should be conducted,” provide concrete specifics for how future can help answer questions that your research could not.

Phrase examples: Recommendation sentence beginners

- Further research is needed to establish …

- There is abundant space for further progress in analyzing…

- A further study with more focus on X should be done to investigate…

- Further studies of X that account for these variables must be undertaken.

Consider Receiving Professional Language Editing

As you edit or draft your research manuscript, we hope that you implement these guidelines to produce a more effective Discussion section. And after completing your draft, don’t forget to submit your work to a professional proofreading and English editing service like Wordvice, including our manuscript editing service for paper editing , cover letter editing , SOP editing , and personal statement proofreading services. Language editors not only proofread and correct errors in grammar, punctuation, mechanics, and formatting but also improve terms and revise phrases so they read more naturally. Wordvice is an industry leader in providing high-quality revision for all types of academic documents.

For additional information about how to write a strong research paper, make sure to check out our full research writing series !

Wordvice Writing Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

Additional Academic Resources

- Guide for Authors. (Elsevier)

- How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper. (Bates College)

- Structure of a Research Paper. (University of Minnesota Biomedical Library)

- How to Choose a Target Journal (Springer)

- How to Write Figures and Tables (UNC Writing Center)

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

Writing a "good" discussion section

"discussion and conclusions checklist" from: how to write a good scientific paper. chris a. mack. spie. 2018., peer review.

- LITERATURE CITED

- Bibliography of guides to scientific writing and presenting

- Presentations

- Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web

This is is usually the hardest section to write. You are trying to bring out the true meaning of your data without being too long. Do not use words to conceal your facts or reasoning. Also do not repeat your results, this is a discussion.

- Present principles, relationships and generalizations shown by the results

- Point out exceptions or lack of correlations. Define why you think this is so.

- Show how your results agree or disagree with previously published works

- Discuss the theoretical implications of your work as well as practical applications

- State your conclusions clearly. Summarize your evidence for each conclusion.

- Discuss the significance of the results

- Evidence does not explain itself; the results must be presented and then explained.

- Typical stages in the discussion: summarizing the results, discussing whether results are expected or unexpected, comparing these results to previous work, interpreting and explaining the results (often by comparison to a theory or model), and hypothesizing about their generality.

- Discuss any problems or shortcomings encountered during the course of the work.

- Discuss possible alternate explanations for the results.

- Avoid: presenting results that are never discussed; presenting discussion that does not relate to any of the results; presenting results and discussion in chronological order rather than logical order; ignoring results that do not support the conclusions; drawing conclusions from results without logical arguments to back them up.

CONCLUSIONS

- Provide a very brief summary of the Results and Discussion.

- Emphasize the implications of the findings, explaining how the work is significant and providing the key message(s) the author wishes to convey.

- Provide the most general claims that can be supported by the evidence.

- Provide a future perspective on the work.

- Avoid: repeating the abstract; repeating background information from the Introduction; introducing new evidence or new arguments not found in the Results and Discussion; repeating the arguments made in the Results and Discussion; failing to address all of the research questions set out in the Introduction.

WHAT HAPPENS AFTER I COMPLETE MY PAPER?

The peer review process is the quality control step in the publication of ideas. Papers that are submitted to a journal for publication are sent out to several scientists (peers) who look carefully at the paper to see if it is "good science". These reviewers then recommend to the editor of a journal whether or not a paper should be published. Most journals have publication guidelines. Ask for them and follow them exactly. Peer reviewers examine the soundness of the materials and methods section. Are the materials and methods used written clearly enough for another scientist to reproduce the experiment? Other areas they look at are: originality of research, significance of research question studied, soundness of the discussion and interpretation, correct spelling and use of technical terms, and length of the article.

- << Previous: RESULTS

- Next: LITERATURE CITED >>

- Last Updated: Aug 4, 2023 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/scientificwriting

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

Guide to Writing the Results and Discussion Sections of a Scientific Article

A quality research paper has both the qualities of in-depth research and good writing ( Bordage, 2001 ). In addition, a research paper must be clear, concise, and effective when presenting the information in an organized structure with a logical manner ( Sandercock, 2013 ).

In this article, we will take a closer look at the results and discussion section. Composing each of these carefully with sufficient data and well-constructed arguments can help improve your paper overall.

The results section of your research paper contains a description about the main findings of your research, whereas the discussion section interprets the results for readers and provides the significance of the findings. The discussion should not repeat the results.

Let’s dive in a little deeper about how to properly, and clearly organize each part.

How to Organize the Results Section

Since your results follow your methods, you’ll want to provide information about what you discovered from the methods you used, such as your research data. In other words, what were the outcomes of the methods you used?

You may also include information about the measurement of your data, variables, treatments, and statistical analyses.

To start, organize your research data based on how important those are in relation to your research questions. This section should focus on showing major results that support or reject your research hypothesis. Include your least important data as supplemental materials when submitting to the journal.

The next step is to prioritize your research data based on importance – focusing heavily on the information that directly relates to your research questions using the subheadings.

The organization of the subheadings for the results section usually mirrors the methods section. It should follow a logical and chronological order.

Subheading organization

Subheadings within your results section are primarily going to detail major findings within each important experiment. And the first paragraph of your results section should be dedicated to your main findings (findings that answer your overall research question and lead to your conclusion) (Hofmann, 2013).

In the book “Writing in the Biological Sciences,” author Angelika Hofmann recommends you structure your results subsection paragraphs as follows:

- Experimental purpose

- Interpretation

Each subheading may contain a combination of ( Bahadoran, 2019 ; Hofmann, 2013, pg. 62-63):

- Text: to explain about the research data

- Figures: to display the research data and to show trends or relationships, for examples using graphs or gel pictures.

- Tables: to represent a large data and exact value

Decide on the best way to present your data — in the form of text, figures or tables (Hofmann, 2013).

Data or Results?

Sometimes we get confused about how to differentiate between data and results . Data are information (facts or numbers) that you collected from your research ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

Whereas, results are the texts presenting the meaning of your research data ( Bahadoran, 2019 ).

One mistake that some authors often make is to use text to direct the reader to find a specific table or figure without further explanation. This can confuse readers when they interpret data completely different from what the authors had in mind. So, you should briefly explain your data to make your information clear for the readers.

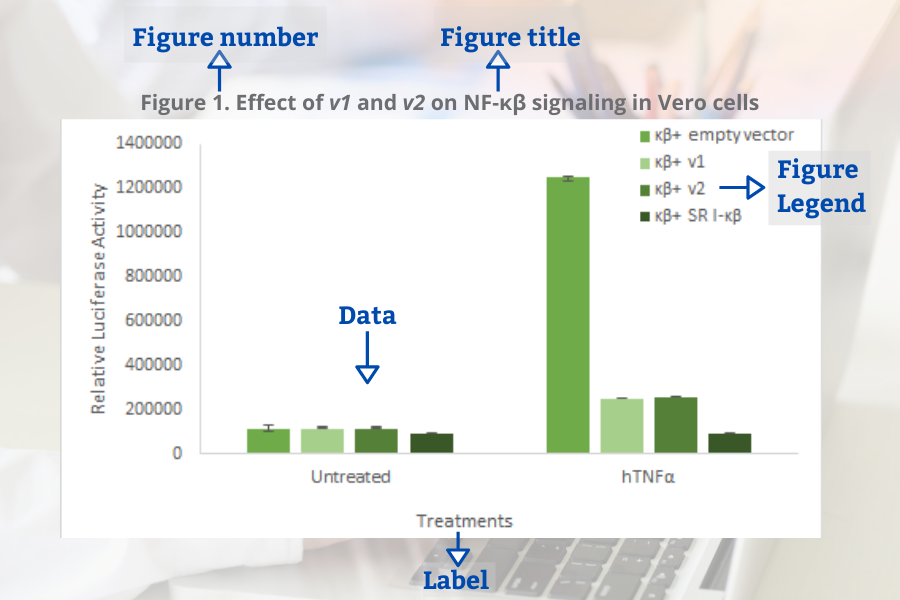

Common Elements in Figures and Tables

Figures and tables present information about your research data visually. The use of these visual elements is necessary so readers can summarize, compare, and interpret large data at a glance. You can use graphs or figures to compare groups or patterns. Whereas, tables are ideal to present large quantities of data and exact values.

Several components are needed to create your figures and tables. These elements are important to sort your data based on groups (or treatments). It will be easier for the readers to see the similarities and differences among the groups.

When presenting your research data in the form of figures and tables, organize your data based on the steps of the research leading you into a conclusion.

Common elements of the figures (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Figure number

- Figure title

- Figure legend (for example a brief title, experimental/statistical information, or definition of symbols).

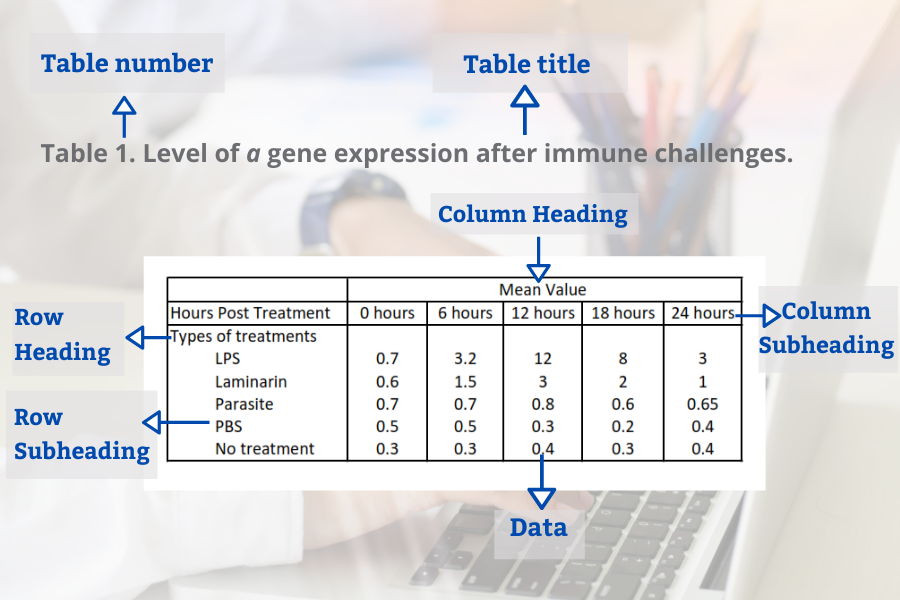

Tables in the result section may contain several elements (Bahadoran, 2019):

- Table number

- Table title

- Row headings (for example groups)

- Column headings

- Row subheadings (for example categories or groups)

- Column subheadings (for example categories or variables)

- Footnotes (for example statistical analyses)

Tips to Write the Results Section

- Direct the reader to the research data and explain the meaning of the data.

- Avoid using a repetitive sentence structure to explain a new set of data.

- Write and highlight important findings in your results.

- Use the same order as the subheadings of the methods section.

- Match the results with the research questions from the introduction. Your results should answer your research questions.

- Be sure to mention the figures and tables in the body of your text.

- Make sure there is no mismatch between the table number or the figure number in text and in figure/tables.

- Only present data that support the significance of your study. You can provide additional data in tables and figures as supplementary material.

How to Organize the Discussion Section

It’s not enough to use figures and tables in your results section to convince your readers about the importance of your findings. You need to support your results section by providing more explanation in the discussion section about what you found.

In the discussion section, based on your findings, you defend the answers to your research questions and create arguments to support your conclusions.

Below is a list of questions to guide you when organizing the structure of your discussion section ( Viera et al ., 2018 ):

- What experiments did you conduct and what were the results?

- What do the results mean?

- What were the important results from your study?

- How did the results answer your research questions?

- Did your results support your hypothesis or reject your hypothesis?

- What are the variables or factors that might affect your results?

- What were the strengths and limitations of your study?

- What other published works support your findings?

- What other published works contradict your findings?

- What possible factors might cause your findings different from other findings?

- What is the significance of your research?

- What are new research questions to explore based on your findings?

Organizing the Discussion Section

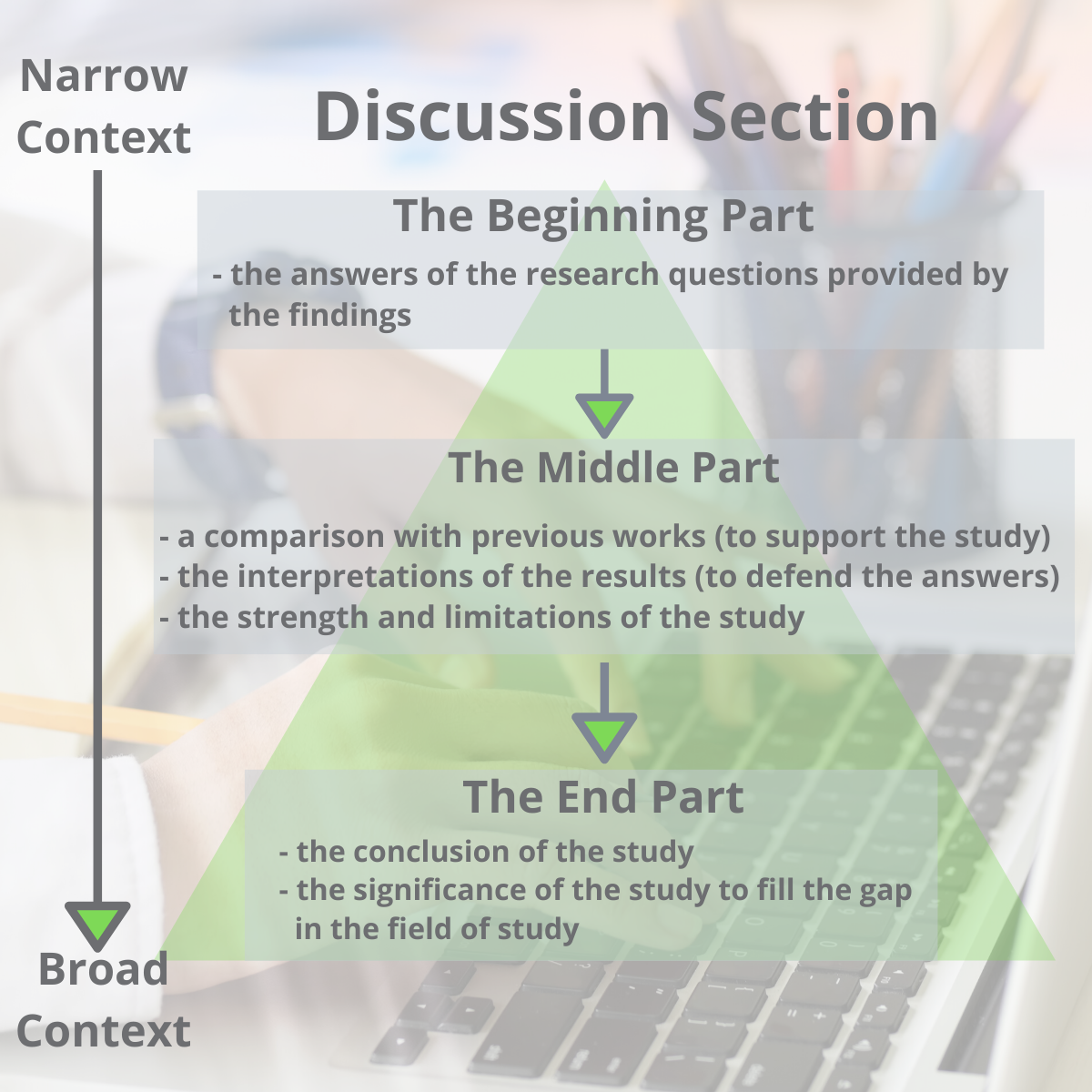

The structure of the discussion section may be different from one paper to another, but it commonly has a beginning, middle-, and end- to the section.

One way to organize the structure of the discussion section is by dividing it into three parts (Ghasemi, 2019):

- The beginning: The first sentence of the first paragraph should state the importance and the new findings of your research. The first paragraph may also include answers to your research questions mentioned in your introduction section.

- The middle: The middle should contain the interpretations of the results to defend your answers, the strength of the study, the limitations of the study, and an update literature review that validates your findings.

- The end: The end concludes the study and the significance of your research.

Another possible way to organize the discussion section was proposed by Michael Docherty in British Medical Journal: is by using this structure ( Docherty, 1999 ):

- Discussion of important findings

- Comparison of your results with other published works

- Include the strengths and limitations of the study

- Conclusion and possible implications of your study, including the significance of your study – address why and how is it meaningful

- Future research questions based on your findings

Finally, a last option is structuring your discussion this way (Hofmann, 2013, pg. 104):

- First Paragraph: Provide an interpretation based on your key findings. Then support your interpretation with evidence.

- Secondary results

- Limitations

- Unexpected findings

- Comparisons to previous publications

- Last Paragraph: The last paragraph should provide a summarization (conclusion) along with detailing the significance, implications and potential next steps.

Remember, at the heart of the discussion section is presenting an interpretation of your major findings.

Tips to Write the Discussion Section

- Highlight the significance of your findings

- Mention how the study will fill a gap in knowledge.

- Indicate the implication of your research.

- Avoid generalizing, misinterpreting your results, drawing a conclusion with no supportive findings from your results.

Aggarwal, R., & Sahni, P. (2018). The Results Section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 21-38): Springer.

Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Zadeh-Vakili, A., Hosseinpanah, F., & Ghasemi, A. (2019). The principles of biomedical scientific writing: Results. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(2).

Bordage, G. (2001). Reasons reviewers reject and accept manuscripts: the strengths and weaknesses in medical education reports. Academic medicine, 76(9), 889-896.

Cals, J. W., & Kotz, D. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part VI: discussion. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(10), 1064.

Docherty, M., & Smith, R. (1999). The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers: Much the same as that for structuring abstracts. In: British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

Faber, J. (2017). Writing scientific manuscripts: most common mistakes. Dental press journal of orthodontics, 22(5), 113-117.

Fletcher, R. H., & Fletcher, S. W. (2018). The discussion section. In Reporting and Publishing Research in the Biomedical Sciences (pp. 39-48): Springer.

Ghasemi, A., Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., Hosseinpanah, F., Shiva, N., & Zadeh-Vakili, A. (2019). The Principles of Biomedical Scientific Writing: Discussion. International journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 17(3).

Hofmann, A. H. (2013). Writing in the biological sciences: a comprehensive resource for scientific communication . New York: Oxford University Press.

Kotz, D., & Cals, J. W. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part V: results. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 66(9), 945.

Mack, C. (2014). How to Write a Good Scientific Paper: Structure and Organization. Journal of Micro/ Nanolithography, MEMS, and MOEMS, 13. doi:10.1117/1.JMM.13.4.040101