How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For qualitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Jenna Crossley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | August 2021

So, you’ve collected and analysed your qualitative data, and it’s time to write up your results chapter. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll guide you through the qualitative results chapter (also called the findings chapter), step by step.

Overview: Qualitative Results Chapter

- What (exactly) the qualitative results chapter is

- What to include in your results chapter

- How to write up your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks to help you along the way

- Free results chapter template

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods ). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and discuss its meaning), depending on your university’s preference. We’ll treat the two chapters as separate, as that’s the most common approach.

In contrast to a quantitative results chapter that presents numbers and statistics, a qualitative results chapter presents data primarily in the form of words . But this doesn’t mean that a qualitative study can’t have quantitative elements – you could, for example, present the number of times a theme or topic pops up in your data, depending on the analysis method(s) you adopt.

Adding a quantitative element to your study can add some rigour, which strengthens your results by providing more evidence for your claims. This is particularly common when using qualitative content analysis. Keep in mind though that qualitative research aims to achieve depth, richness and identify nuances , so don’t get tunnel vision by focusing on the numbers. They’re just cream on top in a qualitative analysis.

So, to recap, the results chapter is where you objectively present the findings of your analysis, without interpreting them (you’ll save that for the discussion chapter). With that out the way, let’s take a look at what you should include in your results chapter.

What should you include in the results chapter?

As we’ve mentioned, your qualitative results chapter should purely present and describe your results , not interpret them in relation to the existing literature or your research questions . Any speculations or discussion about the implications of your findings should be reserved for your discussion chapter.

In your results chapter, you’ll want to talk about your analysis findings and whether or not they support your hypotheses (if you have any). Naturally, the exact contents of your results chapter will depend on which qualitative analysis method (or methods) you use. For example, if you were to use thematic analysis, you’d detail the themes identified in your analysis, using extracts from the transcripts or text to support your claims.

While you do need to present your analysis findings in some detail, you should avoid dumping large amounts of raw data in this chapter. Instead, focus on presenting the key findings and using a handful of select quotes or text extracts to support each finding . The reams of data and analysis can be relegated to your appendices.

While it’s tempting to include every last detail you found in your qualitative analysis, it is important to make sure that you report only that which is relevant to your research aims, objectives and research questions . Always keep these three components, as well as your hypotheses (if you have any) front of mind when writing the chapter and use them as a filter to decide what’s relevant and what’s not.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

Now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to look at how to structure your chapter. Broadly speaking, the results chapter needs to contain three core components – the introduction, the body and the concluding summary. Let’s take a look at each of these.

Section 1: Introduction

The first step is to craft a brief introduction to the chapter. This intro is vital as it provides some context for your findings. In your introduction, you should begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions and highlight the purpose of your research . Make sure that you spell this out for the reader so that the rest of your chapter is well contextualised.

The next step is to briefly outline the structure of your results chapter. In other words, explain what’s included in the chapter and what the reader can expect. In the results chapter, you want to tell a story that is coherent, flows logically, and is easy to follow , so make sure that you plan your structure out well and convey that structure (at a high level), so that your reader is well oriented.

The introduction section shouldn’t be lengthy. Two or three short paragraphs should be more than adequate. It is merely an introduction and overview, not a summary of the chapter.

Pro Tip – To help you structure your chapter, it can be useful to set up an initial draft with (sub)section headings so that you’re able to easily (re)arrange parts of your chapter. This will also help your reader to follow your results and give your chapter some coherence. Be sure to use level-based heading styles (e.g. Heading 1, 2, 3 styles) to help the reader differentiate between levels visually. You can find these options in Word (example below).

Section 2: Body

Before we get started on what to include in the body of your chapter, it’s vital to remember that a results section should be completely objective and descriptive, not interpretive . So, be careful not to use words such as, “suggests” or “implies”, as these usually accompany some form of interpretation – that’s reserved for your discussion chapter.

The structure of your body section is very important , so make sure that you plan it out well. When planning out your qualitative results chapter, create sections and subsections so that you can maintain the flow of the story you’re trying to tell. Be sure to systematically and consistently describe each portion of results. Try to adopt a standardised structure for each portion so that you achieve a high level of consistency throughout the chapter.

For qualitative studies, results chapters tend to be structured according to themes , which makes it easier for readers to follow. However, keep in mind that not all results chapters have to be structured in this manner. For example, if you’re conducting a longitudinal study, you may want to structure your chapter chronologically. Similarly, you might structure this chapter based on your theoretical framework . The exact structure of your chapter will depend on the nature of your study , especially your research questions.

As you work through the body of your chapter, make sure that you use quotes to substantiate every one of your claims . You can present these quotes in italics to differentiate them from your own words. A general rule of thumb is to use at least two pieces of evidence per claim, and these should be linked directly to your data. Also, remember that you need to include all relevant results , not just the ones that support your assumptions or initial leanings.

In addition to including quotes, you can also link your claims to the data by using appendices , which you should reference throughout your text. When you reference, make sure that you include both the name/number of the appendix , as well as the line(s) from which you drew your data.

As referencing styles can vary greatly, be sure to look up the appendix referencing conventions of your university’s prescribed style (e.g. APA , Harvard, etc) and keep this consistent throughout your chapter.

Section 3: Concluding summary

The concluding summary is very important because it summarises your key findings and lays the foundation for the discussion chapter . Keep in mind that some readers may skip directly to this section (from the introduction section), so make sure that it can be read and understood well in isolation.

In this section, you need to remind the reader of the key findings. That is, the results that directly relate to your research questions and that you will build upon in your discussion chapter. Remember, your reader has digested a lot of information in this chapter, so you need to use this section to remind them of the most important takeaways.

Importantly, the concluding summary should not present any new information and should only describe what you’ve already presented in your chapter. Keep it concise – you’re not summarising the whole chapter, just the essentials.

Tips for writing an A-grade results chapter

Now that you’ve got a clear picture of what the qualitative results chapter is all about, here are some quick tips and reminders to help you craft a high-quality chapter:

- Your results chapter should be written in the past tense . You’ve done the work already, so you want to tell the reader what you found , not what you are currently finding .

- Make sure that you review your work multiple times and check that every claim is adequately backed up by evidence . Aim for at least two examples per claim, and make use of an appendix to reference these.

- When writing up your results, make sure that you stick to only what is relevant . Don’t waste time on data that are not relevant to your research objectives and research questions.

- Use headings and subheadings to create an intuitive, easy to follow piece of writing. Make use of Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” and be sure to use them consistently.

- When referring to numerical data, tables and figures can provide a useful visual aid. When using these, make sure that they can be read and understood independent of your body text (i.e. that they can stand-alone). To this end, use clear, concise labels for each of your tables or figures and make use of colours to code indicate differences or hierarchy.

- Similarly, when you’re writing up your chapter, it can be useful to highlight topics and themes in different colours . This can help you to differentiate between your data if you get a bit overwhelmed and will also help you to ensure that your results flow logically and coherently.

If you have any questions, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your results chapter (or any chapter of your dissertation or thesis), check out our private dissertation coaching service here or book a free initial consultation to discuss how we can help you.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

22 Comments

This was extremely helpful. Thanks a lot guys

Hi, thanks for the great research support platform created by the gradcoach team!

I wanted to ask- While “suggests” or “implies” are interpretive terms, what terms could we use for the results chapter? Could you share some examples of descriptive terms?

I think that instead of saying, ‘The data suggested, or The data implied,’ you can say, ‘The Data showed or revealed, or illustrated or outlined’…If interview data, you may say Jane Doe illuminated or elaborated, or Jane Doe described… or Jane Doe expressed or stated.

I found this article very useful. Thank you very much for the outstanding work you are doing.

What if i have 3 different interviewees answering the same interview questions? Should i then present the results in form of the table with the division on the 3 perspectives or rather give a results in form of the text and highlight who said what?

I think this tabular representation of results is a great idea. I am doing it too along with the text. Thanks

That was helpful was struggling to separate the discussion from the findings

this was very useful, Thank you.

Very helpful, I am confident to write my results chapter now.

It is so helpful! It is a good job. Thank you very much!

Very useful, well explained. Many thanks.

Hello, I appreciate the way you provided a supportive comments about qualitative results presenting tips

I loved this! It explains everything needed, and it has helped me better organize my thoughts. What words should I not use while writing my results section, other than subjective ones.

Thanks a lot, it is really helpful

Thank you so much dear, i really appropriate your nice explanations about this.

Thank you so much for this! I was wondering if anyone could help with how to prproperly integrate quotations (Excerpts) from interviews in the finding chapter in a qualitative research. Please GradCoach, address this issue and provide examples.

what if I’m not doing any interviews myself and all the information is coming from case studies that have already done the research.

Very helpful thank you.

This was very helpful as I was wondering how to structure this part of my dissertation, to include the quotes… Thanks for this explanation

This is very helpful, thanks! I am required to write up my results chapters with the discussion in each of them – any tips and tricks for this strategy?

For qualitative studies, can the findings be structured according to the Research questions? Thank you.

Do I need to include literature/references in my findings chapter?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Qualitative Data Analysis

23 Presenting the Results of Qualitative Analysis

Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur

Qualitative research is not finished just because you have determined the main findings or conclusions of your study. Indeed, disseminating the results is an essential part of the research process. By sharing your results with others, whether in written form as scholarly paper or an applied report or in some alternative format like an oral presentation, an infographic, or a video, you ensure that your findings become part of the ongoing conversation of scholarship in your field, forming part of the foundation for future researchers. This chapter provides an introduction to writing about qualitative research findings. It will outline how writing continues to contribute to the analysis process, what concerns researchers should keep in mind as they draft their presentations of findings, and how best to organize qualitative research writing

As you move through the research process, it is essential to keep yourself organized. Organizing your data, memos, and notes aids both the analytical and the writing processes. Whether you use electronic or physical, real-world filing and organizational systems, these systems help make sense of the mountains of data you have and assure you focus your attention on the themes and ideas you have determined are important (Warren and Karner 2015). Be sure that you have kept detailed notes on all of the decisions you have made and procedures you have followed in carrying out research design, data collection, and analysis, as these will guide your ultimate write-up.

First and foremost, researchers should keep in mind that writing is in fact a form of thinking. Writing is an excellent way to discover ideas and arguments and to further develop an analysis. As you write, more ideas will occur to you, things that were previously confusing will start to make sense, and arguments will take a clear shape rather than being amorphous and poorly-organized. However, writing-as-thinking cannot be the final version that you share with others. Good-quality writing does not display the workings of your thought process. It is reorganized and revised (more on that later) to present the data and arguments important in a particular piece. And revision is totally normal! No one expects the first draft of a piece of writing to be ready for prime time. So write rough drafts and memos and notes to yourself and use them to think, and then revise them until the piece is the way you want it to be for sharing.

Bergin (2018) lays out a set of key concerns for appropriate writing about research. First, present your results accurately, without exaggerating or misrepresenting. It is very easy to overstate your findings by accident if you are enthusiastic about what you have found, so it is important to take care and use appropriate cautions about the limitations of the research. You also need to work to ensure that you communicate your findings in a way people can understand, using clear and appropriate language that is adjusted to the level of those you are communicating with. And you must be clear and transparent about the methodological strategies employed in the research. Remember, the goal is, as much as possible, to describe your research in a way that would permit others to replicate the study. There are a variety of other concerns and decision points that qualitative researchers must keep in mind, including the extent to which to include quantification in their presentation of results, ethics, considerations of audience and voice, and how to bring the richness of qualitative data to life.

Quantification, as you have learned, refers to the process of turning data into numbers. It can indeed be very useful to count and tabulate quantitative data drawn from qualitative research. For instance, if you were doing a study of dual-earner households and wanted to know how many had an equal division of household labor and how many did not, you might want to count those numbers up and include them as part of the final write-up. However, researchers need to take care when they are writing about quantified qualitative data. Qualitative data is not as generalizable as quantitative data, so quantification can be very misleading. Thus, qualitative researchers should strive to use raw numbers instead of the percentages that are more appropriate for quantitative research. Writing, for instance, “15 of the 20 people I interviewed prefer pancakes to waffles” is a simple description of the data; writing “75% of people prefer pancakes” suggests a generalizable claim that is not likely supported by the data. Note that mixing numbers with qualitative data is really a type of mixed-methods approach. Mixed-methods approaches are good, but sometimes they seduce researchers into focusing on the persuasive power of numbers and tables rather than capitalizing on the inherent richness of their qualitative data.

A variety of issues of scholarly ethics and research integrity are raised by the writing process. Some of these are unique to qualitative research, while others are more universal concerns for all academic and professional writing. For example, it is essential to avoid plagiarism and misuse of sources. All quotations that appear in a text must be properly cited, whether with in-text and bibliographic citations to the source or with an attribution to the research participant (or the participant’s pseudonym or description in order to protect confidentiality) who said those words. Where writers will paraphrase a text or a participant’s words, they need to make sure that the paraphrase they develop accurately reflects the meaning of the original words. Thus, some scholars suggest that participants should have the opportunity to read (or to have read to them, if they cannot read the text themselves) all sections of the text in which they, their words, or their ideas are presented to ensure accuracy and enable participants to maintain control over their lives.

Audience and Voice

When writing, researchers must consider their audience(s) and the effects they want their writing to have on these audiences. The designated audience will dictate the voice used in the writing, or the individual style and personality of a piece of text. Keep in mind that the potential audience for qualitative research is often much more diverse than that for quantitative research because of the accessibility of the data and the extent to which the writing can be accessible and interesting. Yet individual pieces of writing are typically pitched to a more specific subset of the audience.

Let us consider one potential research study, an ethnography involving participant-observation of the same children both when they are at daycare facility and when they are at home with their families to try to understand how daycare might impact behavior and social development. The findings of this study might be of interest to a wide variety of potential audiences: academic peers, whether at your own academic institution, in your broader discipline, or multidisciplinary; people responsible for creating laws and policies; practitioners who run or teach at day care centers; and the general public, including both people who are interested in child development more generally and those who are themselves parents making decisions about child care for their own children. And the way you write for each of these audiences will be somewhat different. Take a moment and think through what some of these differences might look like.

If you are writing to academic audiences, using specialized academic language and working within the typical constraints of scholarly genres, as will be discussed below, can be an important part of convincing others that your work is legitimate and should be taken seriously. Your writing will be formal. Even if you are writing for students and faculty you already know—your classmates, for instance—you are often asked to imitate the style of academic writing that is used in publications, as this is part of learning to become part of the scholarly conversation. When speaking to academic audiences outside your discipline, you may need to be more careful about jargon and specialized language, as disciplines do not always share the same key terms. For instance, in sociology, scholars use the term diffusion to refer to the way new ideas or practices spread from organization to organization. In the field of international relations, scholars often used the term cascade to refer to the way ideas or practices spread from nation to nation. These terms are describing what is fundamentally the same concept, but they are different terms—and a scholar from one field might have no idea what a scholar from a different field is talking about! Therefore, while the formality and academic structure of the text would stay the same, a writer with a multidisciplinary audience might need to pay more attention to defining their terms in the body of the text.

It is not only other academic scholars who expect to see formal writing. Policymakers tend to expect formality when ideas are presented to them, as well. However, the content and style of the writing will be different. Much less academic jargon should be used, and the most important findings and policy implications should be emphasized right from the start rather than initially focusing on prior literature and theoretical models as you might for an academic audience. Long discussions of research methods should also be minimized. Similarly, when you write for practitioners, the findings and implications for practice should be highlighted. The reading level of the text will vary depending on the typical background of the practitioners to whom you are writing—you can make very different assumptions about the general knowledge and reading abilities of a group of hospital medical directors with MDs than you can about a group of case workers who have a post-high-school certificate. Consider the primary language of your audience as well. The fact that someone can get by in spoken English does not mean they have the vocabulary or English reading skills to digest a complex report. But the fact that someone’s vocabulary is limited says little about their intellectual abilities, so try your best to convey the important complexity of the ideas and findings from your research without dumbing them down—even if you must limit your vocabulary usage.

When writing for the general public, you will want to move even further towards emphasizing key findings and policy implications, but you also want to draw on the most interesting aspects of your data. General readers will read sociological texts that are rich with ethnographic or other kinds of detail—it is almost like reality television on a page! And this is a contrast to busy policymakers and practitioners, who probably want to learn the main findings as quickly as possible so they can go about their busy lives. But also keep in mind that there is a wide variation in reading levels. Journalists at publications pegged to the general public are often advised to write at about a tenth-grade reading level, which would leave most of the specialized terminology we develop in our research fields out of reach. If you want to be accessible to even more people, your vocabulary must be even more limited. The excellent exercise of trying to write using the 1,000 most common English words, available at the Up-Goer Five website ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ) does a good job of illustrating this challenge (Sanderson n.d.).

Another element of voice is whether to write in the first person. While many students are instructed to avoid the use of the first person in academic writing, this advice needs to be taken with a grain of salt. There are indeed many contexts in which the first person is best avoided, at least as long as writers can find ways to build strong, comprehensible sentences without its use, including most quantitative research writing. However, if the alternative to using the first person is crafting a sentence like “it is proposed that the researcher will conduct interviews,” it is preferable to write “I propose to conduct interviews.” In qualitative research, in fact, the use of the first person is far more common. This is because the researcher is central to the research project. Qualitative researchers can themselves be understood as research instruments, and thus eliminating the use of the first person in writing is in a sense eliminating information about the conduct of the researchers themselves.

But the question really extends beyond the issue of first-person or third-person. Qualitative researchers have choices about how and whether to foreground themselves in their writing, not just in terms of using the first person, but also in terms of whether to emphasize their own subjectivity and reflexivity, their impressions and ideas, and their role in the setting. In contrast, conventional quantitative research in the positivist tradition really tries to eliminate the author from the study—which indeed is exactly why typical quantitative research avoids the use of the first person. Keep in mind that emphasizing researchers’ roles and reflexivity and using the first person does not mean crafting articles that provide overwhelming detail about the author’s thoughts and practices. Readers do not need to hear, and should not be told, which database you used to search for journal articles, how many hours you spent transcribing, or whether the research process was stressful—save these things for the memos you write to yourself. Rather, readers need to hear how you interacted with research participants, how your standpoint may have shaped the findings, and what analytical procedures you carried out.

Making Data Come Alive

One of the most important parts of writing about qualitative research is presenting the data in a way that makes its richness and value accessible to readers. As the discussion of analysis in the prior chapter suggests, there are a variety of ways to do this. Researchers may select key quotes or images to illustrate points, write up specific case studies that exemplify their argument, or develop vignettes (little stories) that illustrate ideas and themes, all drawing directly on the research data. Researchers can also write more lengthy summaries, narratives, and thick descriptions.

Nearly all qualitative work includes quotes from research participants or documents to some extent, though ethnographic work may focus more on thick description than on relaying participants’ own words. When quotes are presented, they must be explained and interpreted—they cannot stand on their own. This is one of the ways in which qualitative research can be distinguished from journalism. Journalism presents what happened, but social science needs to present the “why,” and the why is best explained by the researcher.

So how do authors go about integrating quotes into their written work? Julie Posselt (2017), a sociologist who studies graduate education, provides a set of instructions. First of all, authors need to remain focused on the core questions of their research, and avoid getting distracted by quotes that are interesting or attention-grabbing but not so relevant to the research question. Selecting the right quotes, those that illustrate the ideas and arguments of the paper, is an important part of the writing process. Second, not all quotes should be the same length (just like not all sentences or paragraphs in a paper should be the same length). Include some quotes that are just phrases, others that are a sentence or so, and others that are longer. We call longer quotes, generally those more than about three lines long, block quotes , and they are typically indented on both sides to set them off from the surrounding text. For all quotes, be sure to summarize what the quote should be telling or showing the reader, connect this quote to other quotes that are similar or different, and provide transitions in the discussion to move from quote to quote and from topic to topic. Especially for longer quotes, it is helpful to do some of this writing before the quote to preview what is coming and other writing after the quote to make clear what readers should have come to understand. Remember, it is always the author’s job to interpret the data. Presenting excerpts of the data, like quotes, in a form the reader can access does not minimize the importance of this job. Be sure that you are explaining the meaning of the data you present.

A few more notes about writing with quotes: avoid patchwriting, whether in your literature review or the section of your paper in which quotes from respondents are presented. Patchwriting is a writing practice wherein the author lightly paraphrases original texts but stays so close to those texts that there is little the author has added. Sometimes, this even takes the form of presenting a series of quotes, properly documented, with nothing much in the way of text generated by the author. A patchwriting approach does not build the scholarly conversation forward, as it does not represent any kind of new contribution on the part of the author. It is of course fine to paraphrase quotes, as long as the meaning is not changed. But if you use direct quotes, do not edit the text of the quotes unless how you edit them does not change the meaning and you have made clear through the use of ellipses (…) and brackets ([])what kinds of edits have been made. For example, consider this exchange from Matthew Desmond’s (2012:1317) research on evictions:

The thing was, I wasn’t never gonna let Crystal come and stay with me from the get go. I just told her that to throw her off. And she wasn’t fittin’ to come stay with me with no money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

A paraphrase of this exchange might read “She said that she was going to let Crystal stay with her if Crystal did not have any money.” Paraphrases like that are fine. What is not fine is rewording the statement but treating it like a quote, for instance writing:

The thing was, I was not going to let Crystal come and stay with me from beginning. I just told her that to throw her off. And it was not proper for her to come stay with me without any money…No. Nope. You might as well stay in that shelter.

But as you can see, the change in language and style removes some of the distinct meaning of the original quote. Instead, writers should leave as much of the original language as possible. If some text in the middle of the quote needs to be removed, as in this example, ellipses are used to show that this has occurred. And if a word needs to be added to clarify, it is placed in square brackets to show that it was not part of the original quote.

Data can also be presented through the use of data displays like tables, charts, graphs, diagrams, and infographics created for publication or presentation, as well as through the use of visual material collected during the research process. Note that if visuals are used, the author must have the legal right to use them. Photographs or diagrams created by the author themselves—or by research participants who have signed consent forms for their work to be used, are fine. But photographs, and sometimes even excerpts from archival documents, may be owned by others from whom researchers must get permission in order to use them.

A large percentage of qualitative research does not include any data displays or visualizations. Therefore, researchers should carefully consider whether the use of data displays will help the reader understand the data. One of the most common types of data displays used by qualitative researchers are simple tables. These might include tables summarizing key data about cases included in the study; tables laying out the characteristics of different taxonomic elements or types developed as part of the analysis; tables counting the incidence of various elements; and 2×2 tables (two columns and two rows) illuminating a theory. Basic network or process diagrams are also commonly included. If data displays are used, it is essential that researchers include context and analysis alongside data displays rather than letting them stand by themselves, and it is preferable to continue to present excerpts and examples from the data rather than just relying on summaries in the tables.

If you will be using graphs, infographics, or other data visualizations, it is important that you attend to making them useful and accurate (Bergin 2018). Think about the viewer or user as your audience and ensure the data visualizations will be comprehensible. You may need to include more detail or labels than you might think. Ensure that data visualizations are laid out and labeled clearly and that you make visual choices that enhance viewers’ ability to understand the points you intend to communicate using the visual in question. Finally, given the ease with which it is possible to design visuals that are deceptive or misleading, it is essential to make ethical and responsible choices in the construction of visualization so that viewers will interpret them in accurate ways.

The Genre of Research Writing

As discussed above, the style and format in which results are presented depends on the audience they are intended for. These differences in styles and format are part of the genre of writing. Genre is a term referring to the rules of a specific form of creative or productive work. Thus, the academic journal article—and student papers based on this form—is one genre. A report or policy paper is another. The discussion below will focus on the academic journal article, but note that reports and policy papers follow somewhat different formats. They might begin with an executive summary of one or a few pages, include minimal background, focus on key findings, and conclude with policy implications, shifting methods and details about the data to an appendix. But both academic journal articles and policy papers share some things in common, for instance the necessity for clear writing, a well-organized structure, and the use of headings.

So what factors make up the genre of the academic journal article in sociology? While there is some flexibility, particularly for ethnographic work, academic journal articles tend to follow a fairly standard format. They begin with a “title page” that includes the article title (often witty and involving scholarly inside jokes, but more importantly clearly describing the content of the article); the authors’ names and institutional affiliations, an abstract , and sometimes keywords designed to help others find the article in databases. An abstract is a short summary of the article that appears both at the very beginning of the article and in search databases. Abstracts are designed to aid readers by giving them the opportunity to learn enough about an article that they can determine whether it is worth their time to read the complete text. They are written about the article, and thus not in the first person, and clearly summarize the research question, methodological approach, main findings, and often the implications of the research.

After the abstract comes an “introduction” of a page or two that details the research question, why it matters, and what approach the paper will take. This is followed by a literature review of about a quarter to a third the length of the entire paper. The literature review is often divided, with headings, into topical subsections, and is designed to provide a clear, thorough overview of the prior research literature on which a paper has built—including prior literature the new paper contradicts. At the end of the literature review it should be made clear what researchers know about the research topic and question, what they do not know, and what this new paper aims to do to address what is not known.

The next major section of the paper is the section that describes research design, data collection, and data analysis, often referred to as “research methods” or “methodology.” This section is an essential part of any written or oral presentation of your research. Here, you tell your readers or listeners “how you collected and interpreted your data” (Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault 2016:215). Taylor, Bogdan, and DeVault suggest that the discussion of your research methods include the following:

- The particular approach to data collection used in the study;

- Any theoretical perspective(s) that shaped your data collection and analytical approach;

- When the study occurred, over how long, and where (concealing identifiable details as needed);

- A description of the setting and participants, including sampling and selection criteria (if an interview-based study, the number of participants should be clearly stated);

- The researcher’s perspective in carrying out the study, including relevant elements of their identity and standpoint, as well as their role (if any) in research settings; and

- The approach to analyzing the data.

After the methods section comes a section, variously titled but often called “data,” that takes readers through the analysis. This section is where the thick description narrative; the quotes, broken up by theme or topic, with their interpretation; the discussions of case studies; most data displays (other than perhaps those outlining a theoretical model or summarizing descriptive data about cases); and other similar material appears. The idea of the data section is to give readers the ability to see the data for themselves and to understand how this data supports the ultimate conclusions. Note that all tables and figures included in formal publications should be titled and numbered.

At the end of the paper come one or two summary sections, often called “discussion” and/or “conclusion.” If there is a separate discussion section, it will focus on exploring the overall themes and findings of the paper. The conclusion clearly and succinctly summarizes the findings and conclusions of the paper, the limitations of the research and analysis, any suggestions for future research building on the paper or addressing these limitations, and implications, be they for scholarship and theory or policy and practice.

After the end of the textual material in the paper comes the bibliography, typically called “works cited” or “references.” The references should appear in a consistent citation style—in sociology, we often use the American Sociological Association format (American Sociological Association 2019), but other formats may be used depending on where the piece will eventually be published. Care should be taken to ensure that in-text citations also reflect the chosen citation style. In some papers, there may be an appendix containing supplemental information such as a list of interview questions or an additional data visualization.

Note that when researchers give presentations to scholarly audiences, the presentations typically follow a format similar to that of scholarly papers, though given time limitations they are compressed. Abstracts and works cited are often not part of the presentation, though in-text citations are still used. The literature review presented will be shortened to only focus on the most important aspects of the prior literature, and only key examples from the discussion of data will be included. For long or complex papers, sometimes only one of several findings is the focus of the presentation. Of course, presentations for other audiences may be constructed differently, with greater attention to interesting elements of the data and findings as well as implications and less to the literature review and methods.

Concluding Your Work

After you have written a complete draft of the paper, be sure you take the time to revise and edit your work. There are several important strategies for revision. First, put your work away for a little while. Even waiting a day to revise is better than nothing, but it is best, if possible, to take much more time away from the text. This helps you forget what your writing looks like and makes it easier to find errors, mistakes, and omissions. Second, show your work to others. Ask them to read your work and critique it, pointing out places where the argument is weak, where you may have overlooked alternative explanations, where the writing could be improved, and what else you need to work on. Finally, read your work out loud to yourself (or, if you really need an audience, try reading to some stuffed animals). Reading out loud helps you catch wrong words, tricky sentences, and many other issues. But as important as revision is, try to avoid perfectionism in writing (Warren and Karner 2015). Writing can always be improved, no matter how much time you spend on it. Those improvements, however, have diminishing returns, and at some point the writing process needs to conclude so the writing can be shared with the world.

Of course, the main goal of writing up the results of a research project is to share with others. Thus, researchers should be considering how they intend to disseminate their results. What conferences might be appropriate? Where can the paper be submitted? Note that if you are an undergraduate student, there are a wide variety of journals that accept and publish research conducted by undergraduates. Some publish across disciplines, while others are specific to disciplines. Other work, such as reports, may be best disseminated by publication online on relevant organizational websites.

After a project is completed, be sure to take some time to organize your research materials and archive them for longer-term storage. Some Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols require that original data, such as interview recordings, transcripts, and field notes, be preserved for a specific number of years in a protected (locked for paper or password-protected for digital) form and then destroyed, so be sure that your plans adhere to the IRB requirements. Be sure you keep any materials that might be relevant for future related research or for answering questions people may ask later about your project.

And then what? Well, then it is time to move on to your next research project. Research is a long-term endeavor, not a one-time-only activity. We build our skills and our expertise as we continue to pursue research. So keep at it.

- Find a short article that uses qualitative methods. The sociological magazine Contexts is a good place to find such pieces. Write an abstract of the article.

- Choose a sociological journal article on a topic you are interested in that uses some form of qualitative methods and is at least 20 pages long. Rewrite the article as a five-page research summary accessible to non-scholarly audiences.

- Choose a concept or idea you have learned in this course and write an explanation of it using the Up-Goer Five Text Editor ( https://www.splasho.com/upgoer5/ ), a website that restricts your writing to the 1,000 most common English words. What was this experience like? What did it teach you about communicating with people who have a more limited English-language vocabulary—and what did it teach you about the utility of having access to complex academic language?

- Select five or more sociological journal articles that all use the same basic type of qualitative methods (interviewing, ethnography, documents, or visual sociology). Using what you have learned about coding, code the methods sections of each article, and use your coding to figure out what is common in how such articles discuss their research design, data collection, and analysis methods.

- Return to an exercise you completed earlier in this course and revise your work. What did you change? How did revising impact the final product?

- Find a quote from the transcript of an interview, a social media post, or elsewhere that has not yet been interpreted or explained. Write a paragraph that includes the quote along with an explanation of its sociological meaning or significance.

The style or personality of a piece of writing, including such elements as tone, word choice, syntax, and rhythm.

A quotation, usually one of some length, which is set off from the main text by being indented on both sides rather than being placed in quotation marks.

A classification of written or artistic work based on form, content, and style.

A short summary of a text written from the perspective of a reader rather than from the perspective of an author.

Social Data Analysis Copyright © 2021 by Mikaila Mariel Lemonik Arthur is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Dissertation Coaching

- Qualitative Data Analysis

- Statistical Consulting

- Dissertation Editing

- On-Demand Courses

How To Write the Findings Chapter for Qualitative Studies

Writing the findings chapter for qualitative studies is a critical step in the research process. This chapter allows researchers to present their findings, analyze the data collected, and draw conclusions based on the study’s objectives. In this blog post, I’lll explore the purpose, key elements, preparation, writing, and presentation of the findings chapter in qualitative studies.

Introduction: Contextualizing Your Findings

The introductory section serves as the gateway to your qualitative findings chapter. Begin by reiterating your problem statement and research questions, setting the stage for the data that will be presented. Highlighting the purpose of your research is crucial at this point to give context to the reader.

Example: The primary aim of this case study is to explore how educators perceive the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) tools in K-12 education settings. This research seeks to understand the perceptions and experiences of educators who have implemented AI technologies in their classrooms, framed within the context of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK). In this chapter, data are systematically organized into three overarching themes, each comprising sub-themes that provide a nuanced understanding of the participants’ perspectives. The research questions guiding this investigation were: (1) What are educators’ perceptions of the role of AI tools in K-12 classrooms? (2) How do educators navigate the challenges of integrating AI tools into their teaching practices? The answers to these questions are integral to understanding the complex dynamics of AI implementation in educational contexts.

Overview of Findings

Following this, offer a brief overview of your main findings. While you should not delve into the details here, giving the reader an idea of what to expect can be helpful. Explain the overall structure of your results chapter and how you’ve organized it to maintain coherence and logical flow.

The Heart of the Matter: The Body of Your Chapter

Presentation.

The body of the chapter is where you lay out your data for the reader. In qualitative research, this usually means dividing your data into themes or categories, which should be clearly described and substantiated with quotes and examples from your dataset. These themes provide the skeletal framework upon which your narrative is built.

Structure and Flow

When planning your qualitative findings chapter, carefully outline the sections and subsections to maintain the flow of the writing and improve readability. You can structure your chapter based on themes, which is often the case in qualitative research, but other formats like chronological or framework-based structures may be more appropriate depending on your specific research design.

✅ Consistency is Key: Make sure each portion of findings adheres to a standardized structure. This enhances consistency and enables the reader to follow your line of reasoning.

Objective and Descriptive Language

While your narrative might touch upon individual experiences and perspectives, remember to maintain an objective tone. Your task is to describe, not interpret—that comes later, in the Discussion chapter. Thus, avoid phrases that suggest interpretation, such as “suggests” or “implies.”

Visual Aids

Tables, figures, and other visual aids can add another layer of comprehension and break up the text, but make sure they can be understood independently of your body text. Label them clearly and use color coding judiciously to indicate differences or hierarchy.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

As you delve into the data, aim to narrate a coherent story. Interpret your findings in light of the literature in the field and your theoretical framework, but remember to clearly differentiate between your descriptions and your interpretations.

✅ References and Appendices: When using quotes or data excerpts, reference them appropriately. Use appendices to present additional data and ensure that you cite them according to the referencing style prescribed by your institution (e.g., APA, Harvard).

Bringing It All Together: The Concluding Summary

This is the section where you summarize your key findings in a concise manner, reiterating points that directly relate to your research questions. It serves as a stepping stone to the Discussion chapter, providing the reader with the essential takeaways. As a rule of thumb, this section should contain no new information.

Additional Tips and Tricks

– Write in the past tense, as you present findings that have already been gathered.

– Review your work multiple times, ensuring each theme or finding is backed by sufficient data.

– Use Microsoft Word’s “heading styles” for consistency.

Final Thoughts

With the right approach, writing the Findings chapter can be an enriching experience that showcases your research and prepares you for discussions and conclusions that follow. The tips and guidelines presented here are meant to make this crucial chapter as clear and impactful as possible, helping you make a valuable contribution to your field of study.

Need Further Assistance?

Dissertation by Design is here to support you every step of the way. Our team of experienced academic coaches and methodologists are dedicated to helping you confidently navigate through each stage of your dissertation journey. Book a free, 30-minute consult today.

Happy writing!

Author: Jessica Parker, EdD

Related posts.

Download our free guide on how to overcome the top 10 challenges common to doctoral candidates and graduate sooner.

Thank You 🙌

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

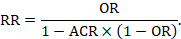

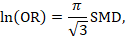

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

| Quantitative research questions | Quantitative research hypotheses |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research questions | Simple hypothesis |

| Comparative research questions | Complex hypothesis |

| Relationship research questions | Directional hypothesis |

| Non-directional hypothesis | |

| Associative hypothesis | |

| Causal hypothesis | |

| Null hypothesis | |

| Alternative hypothesis | |

| Working hypothesis | |

| Statistical hypothesis | |

| Logical hypothesis | |

| Hypothesis-testing | |

| Qualitative research questions | Qualitative research hypotheses |

| Contextual research questions | Hypothesis-generating |

| Descriptive research questions | |

| Evaluation research questions | |

| Explanatory research questions | |

| Exploratory research questions | |

| Generative research questions | |

| Ideological research questions | |

| Ethnographic research questions | |

| Phenomenological research questions | |

| Grounded theory questions | |

| Qualitative case study questions |

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

| Quantitative research questions | |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research question | |

| - Measures responses of subjects to variables | |

| - Presents variables to measure, analyze, or assess | |

| What is the proportion of resident doctors in the hospital who have mastered ultrasonography (response of subjects to a variable) as a diagnostic technique in their clinical training? | |

| Comparative research question | |

| - Clarifies difference between one group with outcome variable and another group without outcome variable | |

| Is there a difference in the reduction of lung metastasis in osteosarcoma patients who received the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group with outcome variable) compared with osteosarcoma patients who did not receive the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group without outcome variable)? | |

| - Compares the effects of variables | |

| How does the vitamin D analogue 22-Oxacalcitriol (variable 1) mimic the antiproliferative activity of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D (variable 2) in osteosarcoma cells? | |

| Relationship research question | |

| - Defines trends, association, relationships, or interactions between dependent variable and independent variable | |

| Is there a relationship between the number of medical student suicide (dependent variable) and the level of medical student stress (independent variable) in Japan during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic? | |

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

| Quantitative research hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| Simple hypothesis | |

| - Predicts relationship between single dependent variable and single independent variable | |

| If the dose of the new medication (single independent variable) is high, blood pressure (single dependent variable) is lowered. | |

| Complex hypothesis | |

| - Foretells relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables | |

| The higher the use of anticancer drugs, radiation therapy, and adjunctive agents (3 independent variables), the higher would be the survival rate (1 dependent variable). | |

| Directional hypothesis | |

| - Identifies study direction based on theory towards particular outcome to clarify relationship between variables | |

| Privately funded research projects will have a larger international scope (study direction) than publicly funded research projects. | |

| Non-directional hypothesis | |

| - Nature of relationship between two variables or exact study direction is not identified | |

| - Does not involve a theory | |

| Women and men are different in terms of helpfulness. (Exact study direction is not identified) | |

| Associative hypothesis | |

| - Describes variable interdependency | |

| - Change in one variable causes change in another variable | |

| A larger number of people vaccinated against COVID-19 in the region (change in independent variable) will reduce the region’s incidence of COVID-19 infection (change in dependent variable). | |

| Causal hypothesis | |

| - An effect on dependent variable is predicted from manipulation of independent variable | |

| A change into a high-fiber diet (independent variable) will reduce the blood sugar level (dependent variable) of the patient. | |

| Null hypothesis | |

| - A negative statement indicating no relationship or difference between 2 variables | |

| There is no significant difference in the severity of pulmonary metastases between the new drug (variable 1) and the current drug (variable 2). | |

| Alternative hypothesis | |

| - Following a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis predicts a relationship between 2 study variables | |

| The new drug (variable 1) is better on average in reducing the level of pain from pulmonary metastasis than the current drug (variable 2). | |

| Working hypothesis | |

| - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory | |

| Dairy cows fed with concentrates of different formulations will produce different amounts of milk. | |

| Statistical hypothesis | |

| - Assumption about the value of population parameter or relationship among several population characteristics | |

| - Validity tested by a statistical experiment or analysis | |

| The mean recovery rate from COVID-19 infection (value of population parameter) is not significantly different between population 1 and population 2. | |

| There is a positive correlation between the level of stress at the workplace and the number of suicides (population characteristics) among working people in Japan. | |

| Logical hypothesis | |

| - Offers or proposes an explanation with limited or no extensive evidence | |

| If healthcare workers provide more educational programs about contraception methods, the number of adolescent pregnancies will be less. | |

| Hypothesis-testing (Quantitative hypothesis-testing research) | |

| - Quantitative research uses deductive reasoning. | |

| - This involves the formation of a hypothesis, collection of data in the investigation of the problem, analysis and use of the data from the investigation, and drawing of conclusions to validate or nullify the hypotheses. | |

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

| Qualitative research questions | |

|---|---|

| Contextual research question | |

| - Ask the nature of what already exists | |

| - Individuals or groups function to further clarify and understand the natural context of real-world problems | |

| What are the experiences of nurses working night shifts in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic? (natural context of real-world problems) | |

| Descriptive research question | |

| - Aims to describe a phenomenon | |

| What are the different forms of disrespect and abuse (phenomenon) experienced by Tanzanian women when giving birth in healthcare facilities? | |

| Evaluation research question | |

| - Examines the effectiveness of existing practice or accepted frameworks | |

| How effective are decision aids (effectiveness of existing practice) in helping decide whether to give birth at home or in a healthcare facility? | |

| Explanatory research question | |

| - Clarifies a previously studied phenomenon and explains why it occurs | |

| Why is there an increase in teenage pregnancy (phenomenon) in Tanzania? | |

| Exploratory research question | |

| - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated to have a deeper understanding of the research problem | |

| What factors affect the mental health of medical students (areas that have not yet been fully investigated) during the COVID-19 pandemic? | |

| Generative research question | |

| - Develops an in-depth understanding of people’s behavior by asking ‘how would’ or ‘what if’ to identify problems and find solutions | |

| How would the extensive research experience of the behavior of new staff impact the success of the novel drug initiative? | |

| Ideological research question | |

| - Aims to advance specific ideas or ideologies of a position | |

| Are Japanese nurses who volunteer in remote African hospitals able to promote humanized care of patients (specific ideas or ideologies) in the areas of safe patient environment, respect of patient privacy, and provision of accurate information related to health and care? | |

| Ethnographic research question | |

| - Clarifies peoples’ nature, activities, their interactions, and the outcomes of their actions in specific settings | |

| What are the demographic characteristics, rehabilitative treatments, community interactions, and disease outcomes (nature, activities, their interactions, and the outcomes) of people in China who are suffering from pneumoconiosis? | |

| Phenomenological research question | |

| - Knows more about the phenomena that have impacted an individual | |

| What are the lived experiences of parents who have been living with and caring for children with a diagnosis of autism? (phenomena that have impacted an individual) | |

| Grounded theory question | |

| - Focuses on social processes asking about what happens and how people interact, or uncovering social relationships and behaviors of groups | |

| What are the problems that pregnant adolescents face in terms of social and cultural norms (social processes), and how can these be addressed? | |

| Qualitative case study question | |

| - Assesses a phenomenon using different sources of data to answer “why” and “how” questions | |

| - Considers how the phenomenon is influenced by its contextual situation. | |

| How does quitting work and assuming the role of a full-time mother (phenomenon assessed) change the lives of women in Japan? | |

| Qualitative research hypotheses | |

|---|---|

| Hypothesis-generating (Qualitative hypothesis-generating research) | |

| - Qualitative research uses inductive reasoning. | |

| - This involves data collection from study participants or the literature regarding a phenomenon of interest, using the collected data to develop a formal hypothesis, and using the formal hypothesis as a framework for testing the hypothesis. | |

| - Qualitative exploratory studies explore areas deeper, clarifying subjective experience and allowing formulation of a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach. | |

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

| Variables | Unclear and weak statement (Statement 1) | Clear and good statement (Statement 2) | Points to avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research question | Which is more effective between smoke moxibustion and smokeless moxibustion? | “Moreover, regarding smoke moxibustion versus smokeless moxibustion, it remains unclear which is more effective, safe, and acceptable to pregnant women, and whether there is any difference in the amount of heat generated.” | 1) Vague and unfocused questions |