Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Trisha Prentice, MD, PhD (Neonatologist), Comments

Jessica wallace, rn (nicu nurse), and paul mann, md (neonatologist), comments, kate robson (mother of preterm infant and parent representative), comments, annie janvier, md, phd (neonatologist, clinical ethicist), comments, outcome of the case (annie janvier), john d. lantos, md, comments, does it matter if this baby is 22 or 23 weeks.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Annie Janvier , Trisha Prentice , Jessica Wallace , Kate Robson , Paul Mann , John D. Lantos; Does It Matter if This Baby Is 22 or 23 Weeks?. Pediatrics September 2019; 144 (3): e20190113. 10.1542/peds.2019-0113

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

A 530-g girl born at 22 weeks and 6 days’ gestation (determined by an ultrasound at 11 weeks) was admitted to the NICU. Her mother had received prenatal steroids. At 12 hours of age, she was stable on low ventilator settings. Her blood pressure was fine. Her urine output was good. After counseling, her parents voiced understanding of the risks and wanted all available life-supporting measures. Many nurses were distressed that doctors were trying to save a “22-weeker.” In the past, 4 infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation had been admitted to that NICU, and all had died. The attending physician on call had to deal with many sick infants and the nurses’ moral distress.

Recent studies reveal that, with active treatment, infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation can achieve survival rates of 25% to 50%. 1 Nevertheless, many hospitals do not offer life-sustaining interventions for such infants. For NICU clinicians, then, hospital policies and/or customary practices may conflict with clinical judgment and evidence-based outcome studies. Such conflicts can create moral distress. In this Ethics Rounds, we present a case that reveals these dilemmas and analyze possible solutions.

Domenica was 36 hours old when Dr Jane took over her care. Dr Jane was on nights, covering the delivery room and 72-bed NICU with only a junior resident to help her. Domenica was born at 22 weeks and 6 days’ gestation (determined by an ultrasound at 11 weeks.) Her birth weight was 530 g. She was in her “honeymoon”: stable on low ventilator settings at 30% oxygen. Her blood pressure was fine. Her urine output was good. The mother had received prenatal steroids.

When Dr Jane was charged with Domenica’s care, she could feel the tension in the voice of the attending day team. The nurses were distressed that doctors were trying to save a “22-weeker.” They thought that she could not survive and that treatment would just cause pain and prolong the inevitable dying process. In that unit, many infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation received interventions and often survived, but the 4 infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation that had been admitted to the NICU had died. Dr Jane spoke to Domenica’s parents. They were realistic and knew she would probably die but they still hoped to beat the odds.

Dr Jane admired the NICU nurses. She knew how devoted they were and how they had to do all the tough work: pricking, poking, prodding, and suctioning while supporting and comforting the parents.

As midnight approached, Dr Jane realized that a disproportionate amount of her call had been spent managing the nurses’ distress and validating their concerns. Her interventions seemed to work. She gradually felt less hostility from the nurses. Then, at midnight, the nurses changed shifts and it seemed a revolution was starting in the nurses’ staff room. She realized that she would need to start counseling the new nurses; this was taking time away from her caring for the other 71 infants in the NICU.

On the spur of the moment, she changed the identification tag on Domenica’s incubator, threw away the 1 that said “22 weeks,” and replaced it with 1 that said “23 weeks.” When a nurse asked, she said that the gestational age had been uncertain, and that Domenica was in fact probably born at 23 weeks’ gestation. The nurse taking care of Domenica let out a big sigh and said, “Well, there is some hope. We are working for something.” Moral distress disappeared for the rest of the night. Dr Jane told the resident, “Don’t do this at home, not the best thing to do. I know I will pay for this, but I don’t have any ideas for tonight, do you?”

Did Dr Jane do the right thing?

The presence of moral distress is sometimes palpable when you enter a NICU; its influence can be far reaching and at times underappreciated. Traditionally, moral distress has been described as an organizational or systems problem that constrains a clinician into providing care that they judge is not in a patient’s interests. 2 , 3 Professionals suffer when they believe that they are just causing pain with no hope of benefit. To respond to such distress, we must consider the appropriateness or accuracy of the judgment that there is no hope of benefit.

Much moral distress occurs within the context of medical uncertainty. A difference of 24 hours between the gestational ages of 22 weeks and 6 days and 23 weeks does not carry with it the significant change in prognosis worthy of the discrepant moral or emotional response that the altered bassinette tag brings. Although Domenica may indeed be in a “honeymoon phase” and difficult days may be ahead, there is no evidence-based reasoning to justify the belief that a trial of therapy is any more unethical for her than for an infant born at 23 weeks’ gestation. The arbitrary lines that institutions draw between impermissible and permissible (or between futility and hope) on the basis of estimates of gestational age may be well intentioned. They seek to limit expensive and burdensome treatments of limited benefit. Yet, we know that gestational age alone is inadequate for accurate prognostication. 4 We do not yet know if Domenica will have a good outcome. We do know that not offering intensive care will surely lead to her death.

Despite these facts, the moral distress felt by the nurses is real. They remain certain in their conviction that intensive care is not in Domenica’s interests because of their own fixed beliefs and values. The objective evidence is 1 thing. Their own experiences are another. They feel that they are being compelled to do the wrong thing and thus that their moral integrity is being compromised. This moral distress needs to be addressed and managed.

The physician has appropriately endeavored to hear and validate concerns and communicate clear goals of care. This has managed but not resolved the distress. The effects do not carry over from nursing shift to the next. Furthermore, the process is time consuming and likely emotionally draining for the physician.

This case highlights the hidden costs of moral distress. This case will have far-reaching ramifications. One could imagine that the care provided to Domenica may differ from that provided to a more mature infant who is “worth fighting for.” Should Domenica die, it would solidify the convictions of the nurses that treatment of “22-weekers” is futile. Her death would heighten the distress response should another infant with a similar gestation be admitted to the unit. 5 , 6 The moral residue of Domenica’s case may have a powerful effect on responses to future cases.

Meanwhile, the physician is struggling with the need to care for and support the morally distressed nurses while managing the needs of Domenica and many other patients in the unit. As the clinical leader whose tasks include managing the emotions of the NICU team, the physician is expected to deal with the moral distress. She is painfully aware that the nurses are hoping that Dominica’s life-sustaining interventions will be withdrawn. The physician, however, believes that this infant might survive. The parents want Dominica to receive life-sustaining interventions. Thus, Dr Jane takes a moral shortcut and deceives the nurses about Dominica’s gestational age.

By deceiving the nurses, the physician has killed her own moral integrity to protect the integrity of the distressed nurses, ensure ongoing intensive care, and allow her to do her job. This desperate strategy has also modeled deceptive conduct to an impressionable physician in training. The physician does not appear proud of her actions, but she struggles to find a more appropriate strategy to manage the interests of all involved. Given the situation, her actions were ethically appropriate. But they should be taken as a signal that there are deeper institutional problems in this NICU that need to be addressed.

Was there a better approach? It is unlikely that any single isolated intervention will be sufficient because there are both organizational and individual factors at play. Institutions need to work hard to create ethical environments in which clinicians are trained to critically appraise ethical issues before they are raised by emergent clinical situations and where their concerns are heard and validated. Individuals need support to grapple with the subjectivity and uncertainty surrounding clinical decisions and be open to having their moral judgments challenged.

Although the experience of moral distress is real, it does not necessarily follow that the clinical plan or situation that causes that distress is itself unethical or requires change. 7 When moral distress cannot be resolved because of moral subjectivity, individuals need to be mindful of the ways in which their own distress may affect others. These hidden costs of moral distress require further acknowledgment within the dialogue of moral distress.

Deception in health care is rarely justified. The physician felt that, in this case, deception was justified, but it could have a big cost. If the nurses found out the attending physician had been dishonest about the gestational age, trust among the entire health care team and unit morale could be jeopardized.

As health care professionals, we have a duty to interact honestly with our patients, their families, and interprofessionally. This obligation was successfully met in the first part of the shift, with the physician candidly engaging the nursing staff, discussing the goals of care for the patient, and trying to address the nurses’ clinical concerns. The importance of such deliberations to address moral distress and ethical dilemmas in the NICU cannot be overstated. 8 Both nurses and physicians report that lack of communication among team members is a common contributor to moral distress. 9 , 10 Deception could end up exacerbating moral distress rather than relieving it.

The basis for the nurses’ emotional distress in this scenario is likely multifactorial. Nurses frequently have a limited voice in decisions regarding resuscitative efforts and ongoing clinical care for extremely premature infants. They are expected, however, to unequally shoulder the burden of hands-on care for periviable infants and to meet the emotional needs of their parents even when they feel therapeutic interventions are not in the best interests of the patient. 1 , 11 , 12 Routine neonatal nursing care (eg, obtaining cuff blood pressures and changing a diaper) can cause life-threating skin breakdown in the friable, gelatinous skin of periviable infants. Standard nursing interventions such as intravnous insertions, laboratory draws, suctioning, securing endotracheal tubes, line placement, and the care of drains may cause significant pain and discomfort for infants. When infants are extremely fragile, even opening an isolette door can cause distress. 13

There are not many evidence-based guidelines to support best nursing practice for periviable infants, leaving many nurses to feel that they are experimenting on patients by trial and error. Nurses who participate in such care often feel like they are abandoning their oath to “do no harm” and that painful interventions are not in the infant’s best interest.

When the infants have a good chance of a good outcome, nurses feel that the pain is worth it. 1 A nurse in this case is quoted as saying, “Well, there is some hope. We are working for something.” But was there actually more hope for an infant born at 23 weeks’ gestation than for an infant born at 22 weeks and 6 days’ gestation? Neonatal nurses frequently overestimate poor outcomes for premature infants. Such outcome misconception is highest in nurses who infrequently care for periviable infants. 14 Nurses frequently hear about patients who have poor long-term outcomes. They have limited opportunities to see NICU survivors who are thriving. 15 It is always hard to know whether to base clinical judgments on peer-reviewed multicentre outcome studies that show improving outcomes for periviable infants 16 or, instead, to base judgments on local experiences in their own NICU.

Educating the nursing staff on the unique clinical features of Domenica’s case is therefore of the utmost importance. Some factors suggest a higher than average likelihood of a good outcome. Domenica is a girl of average birth weight who received prenatal steroids and was born at a center that provided active treatment at the time of delivery. These variables are all associated with an improved likelihood of survival. 17 Furthermore, given the margin of error on ultrasound dates, 18 Domenica could in fact truly have been born at 23 weeks’ gestation.

Given all these factors, the doctor’s deception in this case regarding Dominica’s presumed gestational age, although expedient for a shift, becomes a missed opportunity for a teachable moment. Even if Domenica does well, the nursing staff will remain reluctant to provide treatment to other neonates born at 22 weeks’ gestation. There is a clear disconnect between the physician’s beliefs about possible clinical outcomes for neonates born at 22 weeks’ gestation and the nurses who think that they “don’t survive.” 19

There are almost no meaningful distinctions to be made regarding treatment of an infant born at 22 weeks and 6 days’ gestation compared with an infant who has achieved 23 weeks’ gestation. The attending physician needs to continue to engage each shift of nurses with as much energy as she can spare; this is the only way to move the clinical care team away from gestational age–based thinking and toward a more holistic care approach that can accommodate the certainty of clinical uncertainty for all periviable infants.

This case fills me with feelings of profound sympathy for all involved: the frightened parents, the exhausted doctor, the nurses struggling with their complex feelings, and, most of all, for the infant. A NICU can feel like a war zone at times with so many competing priorities and life-or-death situations. The drama that is the everyday normal of the NICU can cloud our sense of what is ethical in the moment.

If the noise around the central issue is eliminated; that is to say, if one takes away the fatigue of the medical staff, the lateness of the hour, the doubts or questions 1 caregiver had about intentions or abilities of another, the vulnerability of the parents, and the confusion around discussions of gestational age and viability, a clearer question is left: is it ever ethical for a doctor to lie to nurses about a patient? In this case, Dr Jane’s lying is understandable but ultimately not justifiable. Honesty underpins the trust that is necessary for a team to work together in the NICU. Although it is sometimes difficult to figure out what the truth is, if we know something to be true, it must be acknowledged.

The intention of this lie was to protect the patient but the telling of the lie opened up numerous other channels of potential harm. Once the lie was uncovered, what would that do to the trust relationship between different members of the medical team? What would it mean to the next family with an infant born at 22 weeks’ gestation? Or the next family of an infant whom the doctor claims was born at 23 weeks’ gestation? We cannot confine the impact of our actions to 1 moment or 1 relationship. The impact can continue to spiral in directions we could not possibly anticipate.

It is especially hard to deal with institutional ethical issues at the bedside. Ideally, ethical disputes and discussions should happen up the line (in general theoretical discussions) or well down the line (during debriefs of critical incidents). They should never happen in the room with the patient and family, where the focus should only be on the human being who needs care. The question of whether we should resuscitate “22-weekers” does not belong in the patient’s room. If we create ample opportunities to discuss such questions in more appropriate environments, we will reduce the risk of them occurring in the moment when they are most likely to do harm. Creating these opportunities for exploring ethical issues far away from the bedside helps caregivers manage moral distress and be more present for their actual patient in the moment when their skills are needed.

I am the parent of an infant who spent time in a NICU. I am filled with appreciation for the actions of the doctor. Although I cannot find a way to ethically excuse Dr Jane, I see her as a doctor desperately trying to do the best for 1 small patient at a particularly significant and vulnerable moment. So, although it may seem like I am throwing this doctor under the bus, my emotional response is just the opposite. This is exactly the type of doctor I would wish for in this type of situation, one so dedicated that she or he is willing to entertain personal risk to help Domenica and her parents. My hope is that this 1 action did not lead to harm for this doctor, this infant, or this family and that it in fact advanced or improved care for infants at the edge of viability by helping caregivers gain a new understanding of both the perils and possibilities facing infants born so early.

We know gestational age is imprecise: approximately one-half of the “23-weekers” we take care of are in fact “22-weekers.” We have also known for a long time that gestational age is only 1 of several factors that predicts survival. 4 Despite our knowledge, many guidelines regarding intervention in the periviable period divide infants on the basis of completed 7-day periods of gestation. Such guidelines are neither rational nor ethically defensible. 20 – 22 Infants who are premature, like all other patients, should be assessed as individuals. The aim should be to establish individualized goals of care for each patient and with each family while recognizing uncertainty rather than acting on gestational age labels. 23

Dr Jane violated the nurses’ trust. Honesty is essential for trusting, collegial relationships. But it is easy to say that as an outsider looking in. It is easy for me to write it while sitting in my pink writing chair with my perfect cappuccino. But what were Dr Jane’s alternatives? None of them was much better.

Dr Jane was aware of the empirical evidence about gestational age. She listened to and discussed these issues with the nurses working in the evening. But taking more hours for “debriefing and educating” the night shift would have caused a threat to patient safety. The difficult shift described in the case was not the time or the place to question interventions for fragile infants at risk of death and disability.

These questions need to be discussed in other forums. I wonder if in a large unit such as the one described, the “Time-out: not now/later” approach would have worked. This approach is easier in small open-bay units where all nurses can be reached at the same time and doctors know each nurse individually. In single-room large units, interactions are less efficient and personal. The organization of the provider shifts are also important: interactions between providers are often easier in units with 12-hour shifts and rotating schedules.

This “Time-out: not now/later” approach also requires that the moral distress be dealt with constructively. Taking care of ill patients is difficult. The nurse, resident, and physician taking care of Domenica need to know about goals of care. The other providers need to support them, not add fuel to the fire. Disorganized and excessive “group therapy” can be harmful. Too often, nurses will spend their well-deserved break speaking about “Domenica cases” instead of re-energizing themselves for the rest of their hard shifts. Doctors do the same. A frequent (and worse) situation is when doctors and nurses agree. This can result in unsolved frustration and resentment for those directly dealing with such difficult cases. But whose job is it (or should it be) to manage the nurses’ moral distress during evening and night shifts?

Perhaps Dr Jane felt the most distress that night? Many physicians would have just told the nurses to do their jobs, to face the music, and to stop complaining. Dr Jane took a more creative approach; one that was, admittedly, ethically questionable. By adding several hours to the gestational age, Dr Jane improved Domenica’s care but also created new problems that will have to be dealt with later.

I was biased in commenting on this case because I am Dr Jane.

After the end of the night shift, I disclosed to Domenica’s night nurse that I had changed the gestational age. I told her I was sorry, that I was exhausted, that I did not know what to do to help. I explained that Domenica was born at 22 weeks and 6 days’ gestation, ±5 days, so she may well have been born at 23 weeks’ gestation. Domenica’s nurse smiled. She told me “her 22-weeker” was still stable and this made her hope for the best.

I have reflected a lot about this case. Had Domenica’s parents not been present at bedside, I would not have changed the gestational age. I would have been able to discuss the case with the nurse privately. Because the parents were present, the nurse had limited opportunities to discuss her distress with other providers. She heard the resident and me speak with the parents. She understood what was going on and knew the parents were realistic.

We reflected about the fact that we felt like a team: Domenica was more than “a 22-weeker.” She was “our patient.”

Although I was Dr Jane in this case, I am not the only Dr Jane. Most neonatologists have dealt with similar cases. I have realized through the years that who Dr Jane is matters. It matters that she is a woman. Her age matters. Doctors’ views and styles are shaped by their own experiences with previous patients and perhaps with their own children.

I work with 300 nurses in a large unit. I did my residency where I now work. Some of the nurses I work with saw me grow personally and professionally over the years. They helped me become who I am. Over the years, I shared their moral distress. When I was a resident 22 years ago, like many of them, I was morally distressed about “24-weekers.” Neonatologists listened to us, told us about the outcomes, and gave us articles, but our distress did not decrease. Education, science, and rationality are not enough in these cases. We needed to personally see infants survive and do well. We did not need graphs, percentages, or to debrief or be listened to. Over the years, I have seen tiny infants who survive and do well. I have also seen infants survive and do badly. I also delivered preterm at 24 weeks’ gestation. Doing neonatal follow-up as a fellow gave me a lot of humility. Being in contact with families and on family social media groups helps me remain curious and humble. I see how often my prognostications turned out wrong.

Adding 1 day to Domenica’s gestational age made many providers have a different attitude about her care. It was an effective, if unprofessional, intervention. I have never repeated this; it could have had serious negative impacts in other circumstances. Since Domenica’s case, we now have dedicated support sessions for nurses that are organized by nurses. Sometimes, we do this on an emergency basis. There is still so much more to do.

Domenica had a difficult NICU course, but she survived. She is now 6 years old. Her parents are thrilled about how well she is doing. They are now family stakeholders who help us improve care, teaching, and research. With other parents, they wrote an article called “our child is not just a gestational age” 24 that is closely related to the case.

This case presents a straightforward conflict between bad policy and bad behavior. It is never good for professional morale for doctors to deceive nurses. It is never good for patients when clinicians make decisions that do not reflect the best scientific evidence and clinical judgment. In this case, a doctor was trying to do what she thought was best for her patient and her parents. She was inhibited by many nurses’ perception that such treatment was futile. These perceptions reflect a widely held but erroneous belief that treatment of babies born at 22 weeks is futile. As this case and many studies show, it is not. Decisions for babies born at 22 weeks should be made the way all good clinical decisions are made, by taking into account all the relevant clinical information and the parents’ preferences then making an individualized clinical judgment.

Dr Janvier conceptualized and drafted the introduction, case, and affiliated comment; Drs Prentice, Mann, and Lantos and Ms Wallace and Ms Robson conceptualized the ethical dilemma and drafted the affiliated comment; and all authors reviewed and revised the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: No external funding.

Competing Interests

Reply: does it matter if this baby is 22 or 23 weeks.

Dear Sir or Madam:

I read with great interest the article by Janvier et al. It elegantly discusses providers’ moral dilemma caring for infants born at 22 weeks. I was surprised a case where intervention was refused was not included for a contrasting viewpoint. As a pediatric subspecialty surgeon and mother of a deceased 22-weeker, I feel compelled to offer that perspective.

After 4 years and numerous medical interventions, at nearly 40 years old I was pregnant with my only child. When I began having cervical change while out of town, my husband and I were nervous but remained hopeful. After a cerclage and several days convalescence, we were ready to return home. At hours shy of 22 weeks, our son had a chance. Unfortunately, en route home my condition changed. My husband and I drove directly to our local hospital where I was likely in labor and possibly leaking amniotic fluid. A friend and I inquired about steroids and magnesium to improve my son’s outcome and tocolytics to slow his delivery, but were repeatedly told these interventions “don’t work until 23 weeks.” When my friends, family, and I continued to ask, refusal was portrayed as hospital policy. We were given numerous reasons: I “could get an infection,” steroids and magnesium “aren’t effective at 22 weeks,” my son “probably wouldn’t survive delivery;” and the real kicker because I should have known better, “they don’t make breathing tubes small enough” for my 500g child.

Nearly 24 hours later, my water broke. My son’s arm popped out, he got stuck, I struggled to deliver him, and he died in the process. In my subsequent weeks of maternity/bereavement leave I invested time exploring literature on periviable birth. Going into the hospital, I was aware of thriving 22-weekers and wondered who these super-human babies were if proactive treatment was not physiologically beneficial.

The authors discuss, “deception in healthcare,” in a case where gestational age was misrepresented to facilitate care. Where is discussion of “deception” as it pertains to patients? The information given to me was not rooted in current evidence and I have learned from other mothers this is a common experience. In a study from Germany, only 2 of 47 infants died during delivery demonstrating it is possible to safely deliver a 22-weeker (1). Moreover, their survival rate was 61% with complication rates no different than 23-weekers. In Sweden, another study demonstrated a 53% survival rate with similar morbidity (2). Within North America, the University of Iowa reports a 59% survival rate with 22-weekers (3) and recently demonstrated an amazingly low rate of morbidity with proactive treatment (4).

Working in a center that treats some of the sickest children from around the world, I appreciate moral distress. I have felt it more than once. But as a patient I offer a perspective that hopefully shows the value of persevering in difficult situations. This experience shattered my faith in medicine and it is difficult to cope with aspects of my own pediatric career; prenatal counseling, consulting on children in the NICU, caring for healthy infants. The downstream ramifications impact the colleagues who cover for me and the patients I should have been caring for. I worry I will not last in pediatric medicine.

The next time you or your colleague encounters a 22-weeker feared futile, I’d ask you consider the parents’ perspective. What has shaken my trust most is not that my son died, because I recognize it was a grim situation, but that nobody would even try to help him. In my own professional life, I have had failures but have also been part of amazing “saves” and have learned to imagine the possibilities in our ever-advancing medical environment. I will always wonder, “what if someone had tried when it was my child?”

References:

1. Mehler K, Oberthuer A, Keller T, et al. Survival Among Infants Born at 22 or 23 Weeks’ Gestation Following Active Prenatal and Postnatal Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(7):671–677.

2. Backes, C.H., Söderström, F., Ågren, J. et al. Outcomes following a comprehensive versus a selective approach for infants born at 22 weeks of gestation. J Perinatol 39, 39–47 (2019)

3. University of Iowa Childrens Hospital. Accessed December 15, 2019. https://uichildrens.org/health-library/15-questions-you-should-ask-about...

4. Watkins PL, Dagle JM, Bell EF, and Colaizy TT. Outcomes at 18 to 22 Months of Corrected Age for Infants Born at 22 to 25 Weeks of Gestation in a Center Practicing Active Management. J Pediatr. 2019 Oct 9 [Epub ahead of print].

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Getting Pregnant

- Registry Builder

- Baby Products

- Birth Clubs

- See all in Community

- Ovulation Calculator

- How To Get Pregnant

- How To Get Pregnant Fast

- Ovulation Discharge

- Implantation Bleeding

- Ovulation Symptoms

- Pregnancy Symptoms

- Am I Pregnant?

- Pregnancy Tests

- See all in Getting Pregnant

- Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Week by Week

- Pregnant Sex

- Weight Gain Tracker

- Signs of Labor

- Morning Sickness

- COVID Vaccine and Pregnancy

- Fetal Weight Chart

- Fetal Development

- Pregnancy Discharge

- Find Out Baby Gender

- Chinese Gender Predictor

- See all in Pregnancy

- Baby Name Generator

- Top Baby Names 2023

- Top Baby Names 2024

- How to Pick a Baby Name

- Most Popular Baby Names

- Baby Names by Letter

- Gender Neutral Names

- Unique Boy Names

- Unique Girl Names

- Top baby names by year

- See all in Baby Names

- Baby Development

- Baby Feeding Guide

- Newborn Sleep

- When Babies Roll Over

- First-Year Baby Costs Calculator

- Postpartum Health

- Baby Poop Chart

- See all in Baby

- Average Weight & Height

- Autism Signs

- Child Growth Chart

- Night Terrors

- Moving from Crib to Bed

- Toddler Feeding Guide

- Potty Training

- Bathing and Grooming

- See all in Toddler

- Height Predictor

- Potty Training: Boys

- Potty training: Girls

- How Much Sleep? (Ages 3+)

- Ready for Preschool?

- Thumb-Sucking

- Gross Motor Skills

- Napping (Ages 2 to 3)

- See all in Child

- Photos: Rashes & Skin Conditions

- Symptom Checker

- Vaccine Scheduler

- Reducing a Fever

- Acetaminophen Dosage Chart

- Constipation in Babies

- Ear Infection Symptoms

- Head Lice 101

- See all in Health

- Second Pregnancy

- Daycare Costs

- Family Finance

- Stay-At-Home Parents

- Breastfeeding Positions

- See all in Family

- Baby Sleep Training

- Preparing For Baby

- My Custom Checklist

- My Registries

- Take the Quiz

- Best Baby Products

- Best Breast Pump

- Best Convertible Car Seat

- Best Infant Car Seat

- Best Baby Bottle

- Best Baby Monitor

- Best Stroller

- Best Diapers

- Best Baby Carrier

- Best Diaper Bag

- Best Highchair

- See all in Baby Products

- Why Pregnant Belly Feels Tight

- Early Signs of Twins

- Teas During Pregnancy

- Baby Head Circumference Chart

- How Many Months Pregnant Am I

- What is a Rainbow Baby

- Braxton Hicks Contractions

- HCG Levels By Week

- When to Take a Pregnancy Test

- Am I Pregnant

- Why is Poop Green

- Can Pregnant Women Eat Shrimp

- Insemination

- UTI During Pregnancy

- Vitamin D Drops

- Best Baby Forumla

- Postpartum Depression

- Low Progesterone During Pregnancy

- Baby Shower

- Baby Shower Games

Breech, posterior, transverse lie: What position is my baby in?

Fetal presentation, or how your baby is situated in your womb at birth, is determined by the body part that's positioned to come out first, and it can affect the way you deliver. At the time of delivery, 97 percent of babies are head-down (cephalic presentation). But there are several other possibilities, including feet or bottom first (breech) as well as sideways (transverse lie) and diagonal (oblique lie).

Fetal presentation and position

During the last trimester of your pregnancy, your provider will check your baby's presentation by feeling your belly to locate the head, bottom, and back. If it's unclear, your provider may do an ultrasound or an internal exam to feel what part of the baby is in your pelvis.

Fetal position refers to whether the baby is facing your spine (anterior position) or facing your belly (posterior position). Fetal position can change often: Your baby may be face up at the beginning of labor and face down at delivery.

Here are the many possibilities for fetal presentation and position in the womb.

Medical illustrations by Jonathan Dimes

Head down, facing down (anterior position)

A baby who is head down and facing your spine is in the anterior position. This is the most common fetal presentation and the easiest position for a vaginal delivery.

This position is also known as "occiput anterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the front (anterior) of your pelvis.

Head down, facing up (posterior position)

In the posterior position , your baby is head down and facing your belly. You may also hear it called "sunny-side up" because babies who stay in this position are born facing up. But many babies who are facing up during labor rotate to the easier face down (anterior) position before birth.

Posterior position is formally known as "occiput posterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the back (posterior) of your pelvis.

Frank breech

In the frank breech presentation, both the baby's legs are extended so that the feet are up near the face. This is the most common type of breech presentation. Breech babies are difficult to deliver vaginally, so most arrive by c-section .

Some providers will attempt to turn your baby manually to the head down position by applying pressure to your belly. This is called an external cephalic version , and it has a 58 percent success rate for turning breech babies. For more information, see our article on breech birth .

Complete breech

A complete breech is when your baby is bottom down with hips and knees bent in a tuck or cross-legged position. If your baby is in a complete breech, you may feel kicking in your lower abdomen.

Incomplete breech

In an incomplete breech, one of the baby's knees is bent so that the foot is tucked next to the bottom with the other leg extended, positioning that foot closer to the face.

Single footling breech

In the single footling breech presentation, one of the baby's feet is pointed toward your cervix.

Double footling breech

In the double footling breech presentation, both of the baby's feet are pointed toward your cervix.

Transverse lie

In a transverse lie, the baby is lying horizontally in your uterus and may be facing up toward your head or down toward your feet. Babies settle this way less than 1 percent of the time, but it happens more commonly if you're carrying multiples or deliver before your due date.

If your baby stays in a transverse lie until the end of your pregnancy, it can be dangerous for delivery. Your provider will likely schedule a c-section or attempt an external cephalic version , which is highly successful for turning babies in this position.

Oblique lie

In rare cases, your baby may lie diagonally in your uterus, with his rump facing the side of your body at an angle.

Like the transverse lie, this position is more common earlier in pregnancy, and it's likely your provider will intervene if your baby is still in the oblique lie at the end of your third trimester.

Was this article helpful?

What to know if your baby is breech

What's a sunny-side up baby?

What happens to your baby right after birth

Perineal massage

BabyCenter's editorial team is committed to providing the most helpful and trustworthy pregnancy and parenting information in the world. When creating and updating content, we rely on credible sources: respected health organizations, professional groups of doctors and other experts, and published studies in peer-reviewed journals. We believe you should always know the source of the information you're seeing. Learn more about our editorial and medical review policies .

Ahmad A et al. 2014. Association of fetal position at onset of labor and mode of delivery: A prospective cohort study. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 43(2):176-182. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23929533 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Gray CJ and Shanahan MM. 2019. Breech presentation. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448063/ Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Hankins GD. 1990. Transverse lie. American Journal of Perinatology 7(1):66-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2131781 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Medline Plus. 2020. Your baby in the birth canal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002060.htm Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Where to go next

- Delivery Room Management

- Ethics, Decision making, and Quality of Life

- Hematology; blood and platelet transfusions

- Hypoxic Ischemic Encephalopathy

- Oxygen Therapy

- Pulmonary hypertension, ECMO and inhaled nitric oxide

- Retinopathy

- Sepsis and Necrotising Enterocolitis

- Argentinian Birds

- Australian Birds Part 1

- Australian Birds Part 2

- Australian Wildlife, non-avian

- Birds of Quebec

- California Birds

- English Birds

- Florida Birds

- New Zealand Birds

- Wildlife of the Canadian Rockies

- Wildlife of the West coast, Vancouver Island

- Birds of Hawai’i

- AAP, Scottsdale AZ 2014

- Atlanta 2013

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital September 2016

- Buenos Aires 2017

- Helsinki 2013

- Melbourne 2012

- Neonatologie aan de Maas 2014

- New Brunswick 2013

- PAS 2016- Prognosis Symposium

- Pediatric Academic Societies meeting, Boston 2012

- Saudi Arabia 2012

- Nitric Oxide in the Preterm

- Présentations françaises

- Publications

Active intensive care at 22 weeks gestation

Even the New England Journal are getting in on the act ( Lee CD, et al. Neonatal Resuscitation in 22-Week Pregnancies. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):391-3 ), I guess that someone talked to the editors about the practice variation in resuscitation of profoundly immature babies, and in response they have published this short vignette with 2 somewhat opposing views, Leif Nelin who promotes the idea that we should recommend universal active intervention, and Elizabeth Foglia who is in favour of recommending selective resuscitation.

I find it very interesting that there is not a 3rd author promoting an approach which still happens in many centres, i.e. recommending universal comfort care.

It is also interesting that there is no real disagreement on the facts, that without active intensive care mortality is 100%; that with intensive care some babies survive, and the majority of the survivors have good lives. The actual proportion of survivors is, of course, very variable, and it requires a commitment of both obstetrics and neonatology to work together to achieve the best results.

Dr Foglia says 2 things that require some reflection, she notes that “almost all extremely preterm infants require resuscitative interventions after birth to survive” which is sort of true, but depends on what you mean by “resuscitative interventions”, in most centres all such babies have endotracheal intubation shortly after birth, but further “resuscitative interventions” are uncommon. The second thing is “The current limit of viability is 22 weeks’ gestation.” That is stated as a verity, but it ignores 3 things, 1. we never know exactly what the GA is, except after IVF, so if you actively intervene for all 22 week GA babies, you will have intervened for some at 21 weeks. 2. If survival at 23 weeks can be as high as 60%, surely at 21 weeks and 6 days it would not suddenly drop to zero! 3. There are reported survivors who were thought to be <22 weeks.

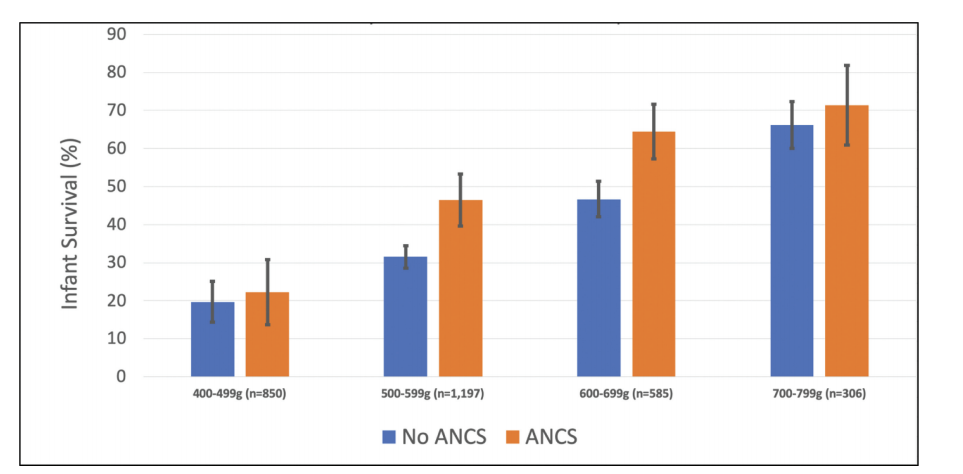

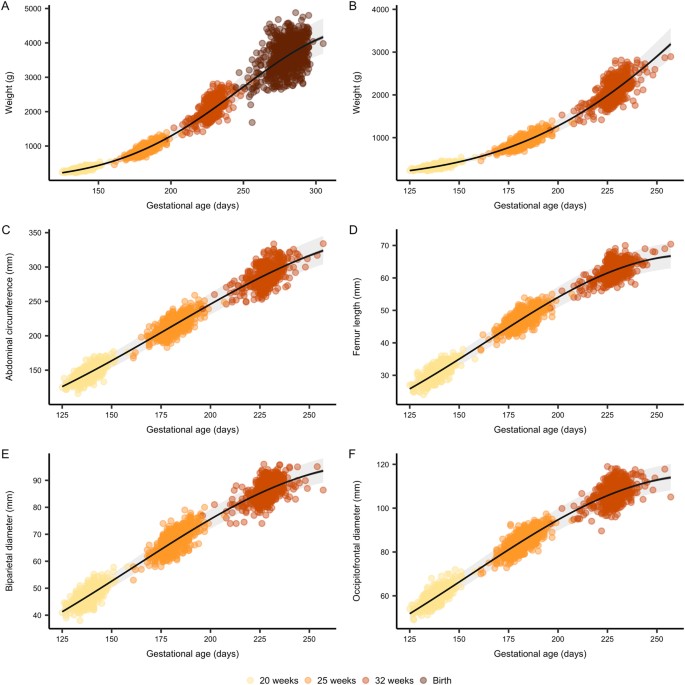

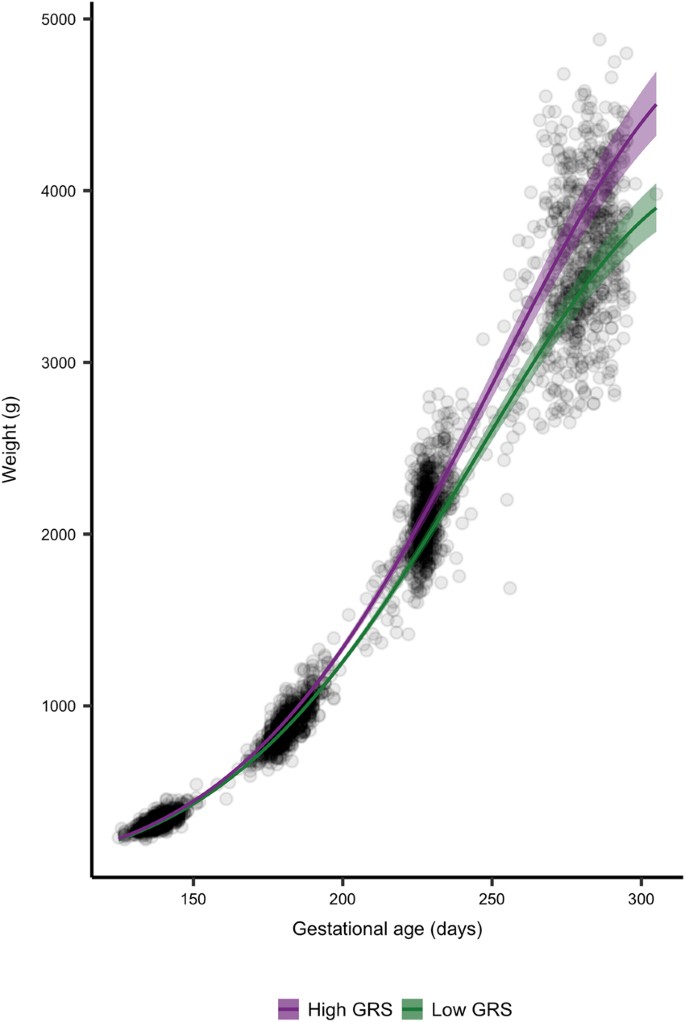

Current guidelines do not often recommend antenatal steroids at 22 and 23 weeks, which is partly because of a lack of such infants in randomized controlled trials, but we are unlikely to have substantial numbers of mother in trials at those gestations for a while, if ever, so observational data are all we are likely to have. Rossi RM, et al. Association of Antenatal Corticosteroid Exposure and Infant Survival at 22 and 23 Weeks. Am J Perinatol. 2021(EFirst) . This article, as one example, calculated the probability of survival at 22 and 23 weeks of GA, according to whether steroids were given prior to delivery. The data source they used had no information of timing of steroids, it was just a checkbox, yes or no. It probably includes, therefore, many babies with brief steroid exposure. Survival is only presented for babies who received active neonatal intensive care. The overall survival at 22 weeks, to one year of age, is shown below, divided by birth weight categories.

They don’t have the same sort of birth weight breakdown for the 23 week babies, but overall 1 year survival was 58% after antenatal steroids, and 48% without steroids. Relative risk 1.5 (95% compatibility intervals, 1.3-1.6). 62% of the 22 week deaths of babies who had antenatal steroids were before 7 days of age, as were 53% of the 23 weeks infants.

Currently all the data about such deliveries is consistent, ANS administration is associated with a major improvement in survival, the NNT is actually smaller than at any later GA. All the studies, unfortunately, suffer also from the same biases, which are sort of self-evident.

What is also consistent, is that centres with the best results , have a co-ordinated approach with obstetrics, and routinely give steroids as soon as the mothers are admitted.

As for my response to the NEJM article? I would perhaps phrase it a little differently, I think that active neonatal intensive care should be offered as an option to all mothers presenting with an increased risk of delivering at 22 to 24 weeks gestation, and that option should be presented as a reasonable choice which will be supported by the whole team, who will then do whatever they can to have the best possible outcome. When additional risk factors are present, such as growth restriction, imminent delivery without benefit of significant ANS exposure, then the discussion of the options must recognize those facts. When increased risk is very great, such as estimated weight <400g or florid chorioamnionitis, then it is vitally important to be realistic. It is also important to recognize that the decision to give steroids, as soon as possible, does not mandate active neonatal care, but will give the best chance for the baby if the later decision is indeed to proceed with intensive care. And that a decision for such care does not mandate a cesarean delivery, which should be considered a separate (obviously related) decision, which takes into account additional factors, including maternal age, risk factors etc.

Share this:

About Keith Barrington

2 responses to active intensive care at 22 weeks gestation.

Hi Keith, You might be interested in our new publication reporting rates of active care and infant survival rates in Victoria in 2009-2017 in a whole-of -state population of babies born at 22-24 weeks’ gestation. We found lower rates of ANC exposure in babies not offered active care (as you would expect) and higher rates in those for whom active care had been provided. That was seen in babies born at 22, 23 and 24 weeks’ gestation. Boland, RA., et al. (2021). Temporal changes in rates of active management and infant survival following live birth at 22–24 weeks’ gestation in Victoria. ANZJOG, doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13309 . But we also found that many clinicians providing care and parent counselling did not have accurate perceptions of outcome of the babies born at 22-25 weeks- underestimating survival and overestimating rates of major disability. And, that clinicians were less accurate in their estimations of outcome in 2020 than they were a decade ago in 2010. Boland, RA., et al. (2021). Disparities between perceived and true outcomes of infants born at 23–25 weeks’ gestation. ANZJOG Online First), 1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajo.13443 So the questions we pose are: What are we telling the parents about their infant’s potential for a good outcome? And how do misconceptions about outcome affect parent counselling and decision-making in babies born at 22 and 23 weeks? More research needed to explore this! Dr Rose Boland Melbourne, Victoria

Thank you Keith. I think we have to remind ourselves that it is not our baby or the hospital’s baby. We must inform the parent’s of what might happen and then their desires and opinions should be followed. If they want the baby to have “a fair go” as the Aussies would say that should be respected. Even if the baby only survives a few hours, or days, they can feel they have tried and done their best. As obstetricians and neonatologists we should be prepared to give the baby the best treatment we know and not be half hearted about it. After all, it is the parents who will have the responsibility and hard work of caring for the child. The era of paternalistic doctors making all the decisions should now be behind us.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Search for:

Recent Posts

- 22 to 23 weeks gestation, what is so special?

- Oxygen is toxic in older kids too!

- Donor human milk, not toxic after all!

- Is there any indication to close the PDA?

- Time to open the DOOR

breathe, baby, breathe

Follow Neonatal Research via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Follow Neonatal Research

- Follow @NeonatalResearc

- antenatal steroids

- antibiotics

- anticonvulsants

- Assisted ventilation

- Breast-feeding

- breast milk

- Congenital Heart Disease

- Convulsions

- Delayed Cord Clamping

- diaphragmatic hernia

- End-of-life decisions

- endotracheal intubation

- enteral feeding

- erythropoietin

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Global Neonatal Health

- Head Ultrasound

- Health Care Organization

- Heart Surgery

- Hemodynamics

- High-Flow cannula

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypotension

- Hypothermia

- hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy

- infection control

- intracranial hemorrhage

- Lactoferrin

- long term outcomes

- lung compliance

- Necrotising Enterocolitis

- Nitric Oxide

- oxygen therapy

- oxygen toxicity

- Preventing Prematurity

- pulmonary physiology

- Randomized Controlled Trials

- Research Design

- respiratory support

- Resuscitation

- Retinopathy of Prematurity

- surfactant treatment

- Systematic Reviews

- transfusion

Respire, bébé, respire!

Canadian Premature Babies Foundation

Sainte Justine Hospital

Canadian Neonatal Network

Préma-Québec

- Advocating for impaired children (23)

- Clinical Practice Guidelines (7)

- Neonatal Research (1,010)

- Not neonatology (28)

- The CPS antenatal counselling statement (14)

Transport Néonatal

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.com

Posts with most views, last 48 hours

- 22 to 23 weeks gestation, what is so special?

- They really are CRAP! C-ReActive Protein: "Hazardous Waste".

- Oxygen is toxic in older kids too!

- Not futile any more; survival and long term outcomes at 22 weeks.

- Breast milk fortifiers, a new systematic review

- Early routine surfactant, method and outcomes

- Is there any indication to close the PDA?

- To bolus or not to bolus? Not really a question...

- What is hypoglycemia? part 2

- Does tactile stimulation in the delivery room actually do anything?

- 1,507,863 hits

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Association between mode of delivery and infant survival at 22 and 23 weeks of gestation

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH (Drs Czarny, Forde, Rossi, and DeFranco);. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH (Drs Czarny, Forde, Rossi, and DeFranco).

- 3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH (Drs Czarny, Forde, Rossi, and DeFranco);; Perinatal Institute, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH (Drs DeFranco and Hall).

- 4 Perinatal Institute, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH (Drs DeFranco and Hall); Translational Data Science and Informatics, Geisinger, Danville, PA, USA (Dr Hall).

- PMID: 33652159

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100340

Background: Cesarean delivery is currently not recommended before 23 weeks' gestation unless for maternal indications, even in the setting of malpresentation. These recommendations are based on a lack of evidence of improved neonatal outcomes and survival following cesarean delivery and the maternal risks associated with cesarean delivery at this early gestational age. However, as neonatal resuscitative measures and obstetrical interventions improve, studies evaluating the potential neonatal benefit of periviable cesarean delivery have reported inconsistent findings.

Objective: This study aimed to compare the survival rates at 1 year of life among resuscitated infants delivered by cesarean delivery with those delivered vaginally at 22 and 23 weeks of gestation.

Study design: We conducted a population-based cohort study of all resuscitated livebirths delivered between 22 0/7 and 23 6/7 weeks of gestational age in the United States between 2007 and 2013. The primary outcome was the rate of infant survival at 1 year of life for different routes of delivery (cesarean vs vaginal delivery) at both 22 and 23 weeks of gestation. The secondary outcome variables included infant survival rates for neonates who survived beyond 24 hours of life, neonatal survival, and the length of survival. A secondary analysis also included a comparison of the infant survival rates between the different routes of delivery cohorts stratified by fetal presentation, steroid exposure, and ventilation. Information about composite adverse maternal outcomes were limited to infants who were delivered between 2011 and 2013 (when these items were first reported) and were defined as a requirement for blood transfusion, an unplanned operating room procedure following delivery, unplanned hysterectomy, and intensive care unit admission; the composite adverse maternal outcomes were also compared between the different delivery route cohorts for deliveries occurring between 22 and 23 weeks of gestation. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association between cesarean delivery and infant survival and other neonatal and maternal outcomes.

Results: Resuscitated infants delivered by cesarean delivery had higher rates of survival at 22 weeks (44.9 vs 23.0%; P<.001) and at 23 weeks (53.3 vs 43.4%; P<.001) of gestation regardless of fetal presentation. Multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated that infants who were delivered by cesarean delivery at 22 weeks (adjusted relative risk, 2.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-2.8) and 23 weeks (adjusted relative risk, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-1.5) of gestation were more likely to survive than those delivered vaginally. When the cohort was limited to neonates who survived beyond the first 24 hours of life, vertex neonates born by cesarean delivery were not more likely to survive at 22 weeks (adjusted relative risk, 1.2; 95% confidence interval, 0.9-1.7) or 23 weeks (adjusted relative risk, 1.1; 95% confidence interval, 0.9-1.3) of gestation. An increased risk for composite adverse maternal outcomes (adjusted relative risk, 1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.7) was associated with cesarean delivery at 22 to 23 weeks of gestation.

Conclusion: Cesarean delivery is associated with increased survival at 1 year of life among resuscitated, periviable infants born between 22 0/7 and 23 6/7 weeks of gestation, especially in the setting of nonvertex presentation. However, cesarean delivery is associated with increased maternal morbidity.

Keywords: antenatal corticosteroids; infant survival; neonatal survival; periviable.

Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

- Cesarean Section*

- Cohort Studies

- Delivery, Obstetric*

- Gestational Age

- Infant, Newborn

- Retrospective Studies

- United States

Variation in fetal presentation

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created The Radswiki had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Yuranga Weerakkody had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- Delivery presentations

- Variation in delivary presentation

- Abnormal fetal presentations

There can be many variations in the fetal presentation which is determined by which part of the fetus is projecting towards the internal cervical os . This includes:

cephalic presentation : fetal head presenting towards the internal cervical os, considered normal and occurs in the vast majority of births (~97%); this can have many variations which include

left occipito-anterior (LOA)

left occipito-posterior (LOP)

left occipito-transverse (LOT)

right occipito-anterior (ROA)

right occipito-posterior (ROP)

right occipito-transverse (ROT)

straight occipito-anterior

straight occipito-posterior

breech presentation : fetal rump presenting towards the internal cervical os, this has three main types

frank breech presentation (50-70% of all breech presentation): hips flexed, knees extended (pike position)

complete breech presentation (5-10%): hips flexed, knees flexed (cannonball position)

footling presentation or incomplete (10-30%): one or both hips extended, foot presenting

other, e.g one leg flexed and one leg extended

shoulder presentation

cord presentation : umbilical cord presenting towards the internal cervical os

- 1. Fox AJ, Chapman MG. Longitudinal ultrasound assessment of fetal presentation: a review of 1010 consecutive cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46 (4): 341-4. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00603.x - Pubmed citation

- 2. Merz E, Bahlmann F. Ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology. Thieme Medical Publishers. (2005) ISBN:1588901475. Read it at Google Books - Find it at Amazon

Incoming Links

- Obstetric curriculum

- Cord presentation

- Polyhydramnios

- Footling presentation

- Normal obstetrics scan (third trimester singleton)

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

, MD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Variations in Fetal Position and Presentation

- 3D Models (0)

- Calculators (0)

- Lab Test (0)

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus’s body that leads the way out through the birth canal (called the presenting part). Usually, the head leads the way, but sometimes the buttocks (breech presentation), shoulder, or face leads the way.

Position refers to whether the fetus is facing backward (occiput anterior) or forward (occiput posterior). The occiput is a bone at the back of the baby's head. Therefore, facing backward is called occiput anterior (facing the mother’s back and facing down when the mother lies on her back). Facing forward is called occiput posterior (facing toward the mother's pubic bone and facing up when the mother lies on her back).

Lie refers to the angle of the fetus in relation to the mother and the uterus. Up-and-down (with the baby's spine parallel to mother's spine, called longitudinal) is normal, but sometimes the lie is sideways (transverse) or at an angle (oblique).

For these aspects of fetal positioning, the combination that is the most common, safest, and easiest for the mother to deliver is the following:

Head first (called vertex or cephalic presentation)

Facing backward (occiput anterior position)

Spine parallel to mother's spine (longitudinal lie)

Neck bent forward with chin tucked

Arms folded across the chest

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible.

Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when

The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion).

The fetus has a birth defect Overview of Birth Defects Birth defects, also called congenital anomalies, are physical abnormalities that occur before a baby is born. They are usually obvious within the first year of life. The cause of many birth... read more .

There is more than one fetus (multiple gestation).

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

Some variations in position and presentation that make delivery difficult occur frequently.

Occiput posterior position

In occiput posterior position (sometimes called sunny-side up), the fetus is head first (vertex presentation) but is facing forward (toward the mother's pubic bone—that is, facing up when the mother lies on her back). This is a very common position that is not abnormal, but it makes delivery more difficult than when the fetus is in the occiput anterior position (facing toward the mother's spine—that is facing down when the mother lies on her back).

Breech presentation

In breech presentation, the baby's buttocks or sometimes the feet are positioned to deliver first (before the head).

When delivered vaginally, babies that present buttocks first are more at risk of injury or even death than those that present head first.

The reason for the risks to babies in breech presentation is that the baby's hips and buttocks are not as wide as the head. Therefore, when the hips and buttocks pass through the cervix first, the passageway may not be wide enough for the head to pass through. In addition, when the head follows the buttocks, the neck may be bent slightly backwards. The neck being bent backward increases the width required for delivery as compared to when the head is angled forward with the chin tucked, which is the position that is easiest for delivery. Thus, the baby’s body may be delivered and then the head may get caught and not be able to pass through the birth canal. When the baby’s head is caught, this puts pressure on the umbilical cord in the birth canal, so that very little oxygen can reach the baby. Brain damage due to lack of oxygen is more common among breech babies than among those presenting head first.

Breech presentation is more likely to occur in the following circumstances:

Labor starts too soon (preterm labor).

Sometimes the doctor can turn the fetus to be head first before labor begins by doing a procedure that involves pressing on the pregnant woman’s abdomen and trying to turn the baby around. Trying to turn the baby is called an external cephalic version and is usually done at 37 or 38 weeks of pregnancy. Sometimes women are given a medication (such as terbutaline ) during the procedure to prevent contractions.

Other presentations

In face presentation, the baby's neck arches back so that the face presents first rather than the top of the head.

In brow presentation, the neck is moderately arched so that the brow presents first.

Usually, fetuses do not stay in a face or brow presentation. These presentations often change to a vertex (top of the head) presentation before or during labor. If they do not, a cesarean delivery is usually recommended.

In transverse lie, the fetus lies horizontally across the birth canal and presents shoulder first. A cesarean delivery is done, unless the fetus is the second in a set of twins. In such a case, the fetus may be turned to be delivered through the vagina.

Was This Page Helpful?

Test your knowledge

Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada)—dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the MSD Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge .

- Permissions

- Cookie Settings

- Terms of use

- Veterinary Edition

- IN THIS TOPIC

Enter search terms to find related medical topics, multimedia and more.

Advanced Search:

- Use “ “ for exact phrases.

- For example: “pediatric abdominal pain”

- Use – to remove results with certain keywords.

- For example: abdominal pain -pediatric

- Use OR to account for alternate keywords.

- For example: teenager OR adolescent

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

, MD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

- 3D Models (0)

- Calculators (0)

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery Operative Vaginal Delivery Operative vaginal delivery involves application of forceps or a vacuum extractor to the fetal head to assist during the second stage of labor and facilitate delivery. Indications for forceps... read more , or cesarean delivery Cesarean Delivery Cesarean delivery is surgical delivery by incision into the uterus. The rate of cesarean delivery was 32% in the United States in 2021 (see March of Dimes: Delivery Method). The rate has fluctuated... read more .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor Preterm Labor Labor (regular uterine contractions resulting in cervical change) that begins before 37 weeks gestation is considered preterm. Risk factors include prelabor rupture of membranes, uterine abnormalities... read more

Multiple gestation Multifetal Pregnancy Multifetal pregnancy is presence of > 1 fetus in the uterus. Multifetal (multiple) pregnancy occurs in up to 1 of 30 deliveries. Risk factors for multiple pregnancy include Ovarian stimulation... read more

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Perinatal death

It is best to detect abnormal fetal lie or presentation before delivery. During routine prenatal care, clinicians assess fetal lie and presentation with physical examination in the late third trimester. Ultrasonography can also be done. If breech presentation is detected, external cephalic version can sometimes move the fetus to vertex presentation before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks. This technique involves gently pressing on the maternal abdomen to reposition the fetus. A dose of a short-acting tocolytic ( terbutaline 0.25 mg subcutaneously) may help. The success rate is about 50 to 75%. For persistent abnormal lie or presentation, cesarean delivery is usually done at 39 weeks or when the woman presents in labor.

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery Operative Vaginal Delivery Operative vaginal delivery involves application of forceps or a vacuum extractor to the fetal head to assist during the second stage of labor and facilitate delivery. Indications for forceps... read more or cesarean delivery Cesarean Delivery Cesarean delivery is surgical delivery by incision into the uterus. The rate of cesarean delivery was 32% in the United States in 2021 (see March of Dimes: Delivery Method). The rate has fluctuated... read more is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

Drugs Mentioned In This Article

Was This Page Helpful?

Test your knowledge

Brought to you by Merck & Co, Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA (known as MSD outside the US and Canada) — dedicated to using leading-edge science to save and improve lives around the world. Learn more about the Merck Manuals and our commitment to Global Medical Knowledge.

- Permissions

- Cookie Settings

- Terms of use

- Veterinary Manual

- IN THIS TOPIC

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Glob J Health Sci

- v.8(2); 2016 Feb

A Triplet Pregnancy with Spontaneous Delivery of a Fetus at Gestational Age of 20 Weeks and Pregnancy Continuation of Two Other Fetuses until Week 33

Maryam ghorbani.

1 Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, IR Iran

Somayeh Moghadam

2 Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Alborz, IR Iran

Introduction:

The prevalence of pregnancies with triplet or more has been increased due to using assisted reproductive treatments. Meanwhile, multiple pregnancies have higher risks and long-term maternal-fetal complications compared to twin and singleton pregnancies. Delayed interval delivery (DID) is a new approach in the management of multiple pregnancies following delivery or abortion. The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the benefits of DID and presents a case that used this method.

This paper covers a report on a case of triplet pregnancy resulting from assisted reproductive techniques with spontaneous delivery of a fetus at gestational age of 20 weeks and the use of conservative DID for two other fetuses until the 33 rd week.

In our case, the delivery of two other fetuses occurred spontaneously at gestational age of 33 weeks after the delivery of the first fetus at week 20.

Conclusions:

Using DID is a useful and reliable method, but requires careful monitoring, especially in patients with a history of infertility.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of pregnancies with triplet or more has been increased due to using assisted reproductive treatments and is directly correlated to the number of embryos transferred into the uterus after IVF. In the United States, the incidence of pregnancies with triplet or more reached 184 per 100,000 from 37 between 1980 and 2002. Although a slight decrease was observed in the incidence in 1998 ( Papageorghiou, Avgidou, Bakoulas, Sebire, & Nicolaides 2006 ), the rate of pregnancies with triplet or more began to fall in 1990, but the rate of twin pregnancies generally increased to 25 percent during this period ( Hasson, Shapira, Many, Jaffa, & Har-Toov, 2011 ).