Cyber Bullying Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on cyber bullying.

Cyber Bullying Essay: In today’s world which has been made smaller by technology, new age problems have been born. No doubt technology has a lot of benefits; however, it also comes with a negative side. It has given birth to cyberbullying. To put it simply, cyberbullying refers to the misuse of information technology with the intention to harass others.

Subsequently, cyberbullying comes in various forms. It doesn’t necessarily mean hacking someone’s profiles or posing to be someone else. It also includes posting negative comments about somebody or spreading rumors to defame someone. As everyone is caught up on the social network, it makes it very easy for anyone to misuse this access.

In other words, cyberbullying has become very common nowadays. It includes actions to manipulate, harass and defame any person. These hostile actions are seriously damaging and can affect anyone easily and gravely. They take place on social media, public forums, and other online information websites. A cyberbully is not necessarily a stranger; it may also be someone you know.

Cyber Bullying is Dangerous

Cyberbullying is a multi-faced issue. However, the intention of this activity is one and the same. To hurt people and bring them harm. Cyberbullying is not a light matter. It needs to be taken seriously as it does have a lot of dangerous effects on the victim.

Moreover, it disturbs the peace of mind of a person. Many people are known to experience depression after they are cyberbullied. In addition, they indulge in self-harm. All the derogatory comments made about them makes them feel inferior.

It also results in a lot of insecurities and complexes. The victim which suffers cyberbullying in the form of harassing starts having self-doubt. When someone points at your insecurities, they only tend to enhance. Similarly, the victims worry and lose their inner peace.

Other than that, cyberbullying also tarnishes the image of a person. It hampers their reputation with the false rumors spread about them. Everything on social media spreads like wildfire. Moreover, people often question the credibility. Thus, one false rumor destroys people’s lives.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

How to Prevent Cyber Bullying?

Cyberbullying prevention is the need of the hour. It needs to be monitored and put an end to. There are various ways to tackle cyberbullying. We can implement them at individual levels as well as authoritative levels.

Firstly, always teach your children to never share personal information online. For instance, if you list your home address or phone number there, it will make you a potential target of cyberbullying easily.

Secondly, avoid posting explicit photos of yourself online. Also, never discuss personal matters on social media. In other words, keep the information limited within your group of friends and family. Most importantly, never ever share your internet password and account details with anyone. Keep all this information to yourself alone. Be alert and do not click on mysterious links, they may be scams. In addition, teach your kids about cyberbullying and make them aware of what’s wrong and right.

In conclusion, awareness is the key to prevent online harassment. We should make the children aware from an early age so they are always cautious. Moreover, parents must monitor their children’s online activities and limit their usage. Most importantly, cyberbullying must be reported instantly without delay. This can prevent further incidents from taking place.

FAQs on Cyber Bullying

Q.1 Why is Cyberbullying dangerous?

A.1 Cyberbullying affects the mental peace of a person. It takes a toll on their mental health. Moreover, it tarnishes the reputation of an individual.

Q.2 How to prevent cyberbullying?

A.2 We may prevent cyberbullying by limiting the information we share online. In addition, we must make children aware of the forms of cyberbullying and its consequences.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Teacher Tips: How to Discuss Cyberbullying in a Safe Environment

Heng Yan Lin

Within the past two years, we have seen sharp demand for virtual learning as the world grapples with the pandemic. The increase in screen time both during and after school hours has exacerbated a growing mental health crisis and cases of cyberbullying among teenagers.

Cyberspace is a convenient place for students to vent their feelings, release their stresses and get into debates as it provides them with anonymity and an accompanying false sense of security. Then there is the fact that policing cyberspace for hate speech, name-calling, harassment, doxing, impersonation, and more is virtually impossible on certain online platforms.

Under the direction of the Ministry of Education in Singapore, local schools are tasked to address this growing problem. Teachers who are the first line of contact for the students may be called upon to discuss cyberbullying issues with the class. Getting students to discuss mental health topics openly can be challenging, especially when valid concerns exist. For instance, students may be worried that they will attract unnecessary and negative attention from others or feel the class is not a safe environment to talk about such issues. In addition, mental health talks can be dry and boring for some.

Discussing Cyberbullying

In this blog, you will find 4 simple activities using ClassPoint that you can use in class to fully engage your students in conversation about cyberbullying.

Survey the Class

It is always helpful to survey the class to understand how much students know about cyberbullying. This will provide a good opening and help you determine the pace of the lesson. Use a Multiple Choice activity that allows them to choose one of the following answers. Do make sure to qualify what ‘good understanding’ means. For example, you could say that having a good understanding of the subject means that you know when cyberbullying is taking place and what you can do to stop it.

For these exercises, I used ClassPoint’s interactive PowerPoint quiz questions to conduct these in-class activities. With ClassPoint, you can add the questions into your already-made PowerPoint and have students answer the questions using their devices live, during class. If you don’t use Microsoft PowerPoint or ClassPoint, you can audibly ask your students these questions, use a different tool, or use a pen and paper.

Invite Participation

Begin with some neutral activities that would avoid making anyone feel vulnerable while participating. A neutral activity, for example, would be to ask the students the question above. Note that the question has been intentionally phrased as “that you know or heard of ” instead of “ that you have received ” as this depersonalizes the question and creates a sense of safety.

Using ClassPoint’s Short Answer tool actually allows you to hide students’ names. Answering with hidden identities can encourage participation and enables students to construct knowledge collectively. Deepen the discussion in class by leveraging on students’ responses; start a spontaneous discussion about why a certain statement is perceived as a cyberbullying message.

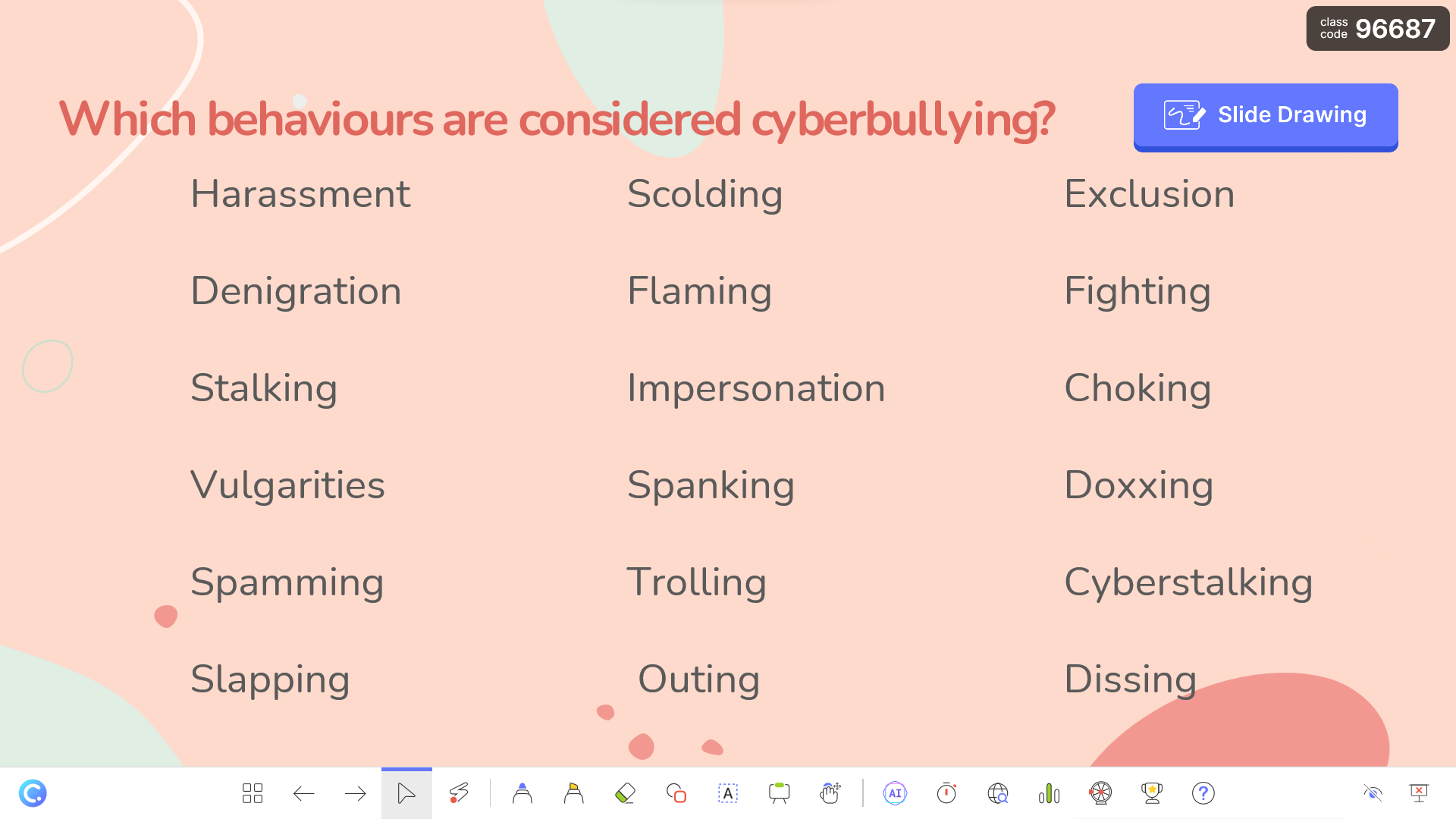

Many people are not always aware of what is considered cyberbullying or that there are five to eleven types of cyberbullying behaviors. Instead of simply telling them about it, why not make it fun and have a quiz? ClassPoint’s Slide Drawing feature allows them to circle or highlight their answers which can then be shared with the class.

If students don’t have devices, again this can be done on the worksheet, or you can write a list of behaviors on your whiteboard before class and have students circle their answers as a class.

Teaching students to develop perspective-talking skills is important as it can help them to develop empathy for the victims. This is done by moving them from the cognitive domain to the emotional domain through open-ended questions about feelings.

In the cyberbullying lesson, you can use Word Cloud to ask them the following question:

Using their answers, you can easily transit into a lesson or discussion about how victims suffer from negative feelings that if left unchecked, will make them more vulnerable to developing certain unhealthy thoughts and behaviors. When prolonged, this puts them at a higher risk of developing mental health issues.

Research has found that cyberbullies sometimes lack the awareness that they are hurting someone by something they said. For example, some name-calling language might be something that the bully is accustomed to and grew up with and therefore does not see anything wrong in saying it to a stranger in an online game chat.

However, the person who receives this may be hurt by it because he/she may happen to be struggling with low self-image and low self-esteem. Through further dialogue, you would want to draw their attention to how certain messages and behaviors (cite examples from Activity 2) can be perceived as hurtful and offensive.

Finding Out More

Mental health lessons are good opportunities for you to identify students who may be in need of help. This can be done via a Multiple Choice Activity where carefully curated questions are posed to the class without a need to publish the answer. Below is a sample of one question that you can ask:

Discussing cyberbullying is important for students, teachers, and schools as education continues to adopt technology and as young students face the repercussions including their mental health and self-esteem when using the internet.

I hope you have seen how these interactive and engaging questions can uncomplicate the subject matter and allow you to navigate any mental health topic with ease. And by using ClassPoint, you can directly engage with every single student during your lesson and help ease into vulnerable discussions with anonymous Q&As. Learn more about using ClassPoint here.

Remember that the key is to create a safe and comfortable online environment by ensuring that students’ identities and stories are not exposed, whilst providing them with a space to seek help and ask questions.

About Heng Yan Lin

Supercharge your powerpoint. start today..

800,000+ people like you use ClassPoint to boost student engagement in PowerPoint presentations.

- Blog Home

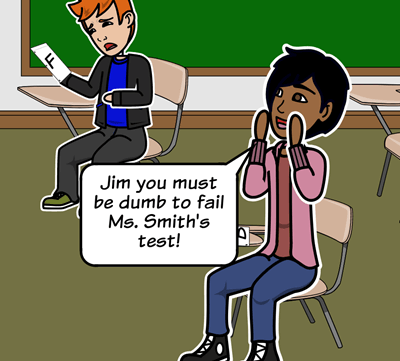

10 Bullying Scenarios to Get Kids Talking

Bullying is a pervasive problem that we want to help kids to be equipped to handle. Bullying can hurt kids physically, emotionally, and academically. This article proposes 10 bullying scenarios to help kids collaboratively and proactively prevent and navigate real-life situations. It also includes a resource for adults, who are often not present when bullying occurs. The 14 Warning Signs of Bullying Resource is designed to help adults, including teachers and caregivers, recognize and respond to the warning signs of bullying.

What is Bullying?

Bullying is the act of seeking to harm, intimidate, or coerce someone, who is often perceived as vulnerable. According to stopbullying.gov , bullying is “unwanted, aggressive behavior among school aged children that involves a real or perceived power imbalance. The behavior is repeated, or has the potential to be repeated, over time.” Bullying means that a person is intentionally causing pain to another person, whether physically, emotionally, or electronically.

Bullying may be verbal, physical, or social.

Bullying affects younger children but the problem can worsen for older children. As their social worlds become more complex and interconnected online and offline, kids will inevitably encounter bullying in the real world and in the virtual one. They will need to respond to situations in which they recognize or are affected by bullying.

The Dangers of Bullying

Bullying can threaten kids’ physical and emotional safety and can impede their ability to learn. The effects of bullying include stress, anxiety, depression, and humiliation. The result of bullying can be serious mental health problems. When kids are anxious, fearful, and depressed, they also suffer cognitively. This means that they cannot focus or achieve academically and socially at school.

Bullying has terrible effects on all those involved, including the target of bullying behavior, the person exhibiting bullying behaviors, and bystanders. It is critical that children and adults know ways to recognize bullying and strategies and skills to help stop it. It is helpful to have early conversations about bullying and to give children and adults tools to identify bullying before they encounter it.

Bullying Scenarios

Preparing to manage experiences before they occur will allow kids to better manage them in real time. Early conversations about bullying can help prepare students for when they encounter bullying situations.

Hypothetical bullying scenarios are an excellent tool for presenting real-life examples that students may not anticipate without the heightened emotions that students may experience in real social settings. Scenarios allow kids time to think clearly on the issues presented while they collaborate with peers. In group discussions, ask kids to imagine themselves in the following bullying situations and describe what they would do.

A new student started at your school this week, and he is having trouble fitting in. Some of your friends have been laughing behind his back. What would you do?

Turned Tables

You receive an email telling an embarrassing story about another student who has often been mean to you. You know your friends would think it’s funny. What would you do?

Fighting Chance

Someone shoves you and wants to fight you. You want to stick up for yourself, but you don’t want to get into a fight. What would you do?

Unwelcome Invitation

Everyone is afraid of three mean kids at your school. You’re afraid, too. One day they ask you to hang out with them. What would you do?

Forward Faux Pas

You sent a mean text about a kid who bullies to a friend, and your friend forwarded it to others. It eventually got back to the kid. What would you do?

On Your Own

You report bullying to your teacher, but the teacher doesn’t believe you. What would you do?

You hear that someone you thought was a friend has been spreading a cruel and untrue rumor about you. What would you do?

You’re invited to a party, but your friend isn’t. At the party, some of the kids make jokes about your friend and laugh at him. What would you do?

You’re shy, and sometimes you get teased for it. You have to admit, it would be nice to have more friends. What would you do?

Recognizing Bullying

Research shows that quick and consistent adult responses to bullying sends the message that it is not acceptable and can stop bullying behavior over time. Strategies involving adults, including caregivers, teachers, administrators, can help kids in several ways. Prevention strategies, efforts to create a safe environment, and leading transparent conversations about bullying are effective.

Because of the terrible effects of bullying, teachers must also be able to recognize and respond to signs of bullying involving students at school. Only 20 to 30 percent of students who are bullied notify adults (Ttofi et al, 2011) and most bullying occurs when adults are not present. It’s crucial to know the warning signs.

The effects of bullying are far-reaching and affect kids in schools everywhere. Bullying scenarios can help kids recognize and respond to bullying when they encounter it in the real world or the virtual world. And adults, including caregivers and teachers, can be aware of more subtle warning signs of bullying so that they can support kids and prevent bullying for everyone’s benefit.

Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: a systematic/meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Criminal behaviour and mental health : CBMH, 21(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.808

Categories:

Author bio:, free spirit team.

An imprint of Teacher Created Materials, Free Spirit is the leading publisher of learning tools that support young people's social, emotional, and educational needs. Free Spirit's mission is to help children and teens think for themselves, overcome challenges, and make a difference in the world.

Share this article:

Join the free spirit publishing blog community.

Subscribe by sharing your email address and we will share new posts, helpful resources and special offers on the issues and topics that matter to you and the children and teens you support.

You May Also Be Interested In:

5 ways to prevent bullying in school, 10 tips to help teachers de-stress, social-emotional learning starts with us.

Cyberbullying Lesson Plan: Digital Literacy

*Click to open and customize your own copy of the Cyberbullying Lesson Plan .

This lesson accompanies the BrainPOP topic Cyberbullying , and supports the standard of identifying and describing unsafe actions online. Students demonstrate understanding through a variety of projects.

Step 1: ACTIVATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

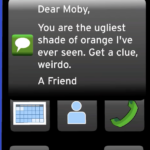

Display this image from the movie (time code: 0:53):

- How do you think this text makes Moby feel?

- Do you think this is cyberbullying? Why or why not?

Step 2: BUILD KNOWLEDGE

- Read aloud the description on the Cyberbullying topic page .

- Play the Movie , pausing to check for understanding.

- Assign Related Reading . Have students read one of the following articles: “Graphs, Stats, and Numbers” or “Laws and Customs”. Partner them with someone who read a different article to share what they learned with each other.

Step 3: APPLY and ASSESS

Assign the Cyberbullying Challenge and Quiz , prompting students to apply essential literacy skills while demonstrating what they learned about this topic.

Step 4: DEEPEN and EXTEND

Students express what they learned about cyberbullying while practicing essential literacy skills with one or more of the following activities. Differentiate by assigning ones that meet individual student needs.

- Make-a-Movie : Produce a PSA about the issue of cyberbullying that answers this question: What are different strategies to deal with cyberbullies safely?

- Make-a-Map : Make a concept map identifying different strategies to solve the problem of cyberbullying.

- Creative Coding : Code a conversation where a character explains how to respond to a cyberbullying situation.

- Primary Source Activity : Read the article and cite details to answer the questions.

More to Explore

Digital Citizenship Resources: Continue to build understanding around digital citizenship with more BrainPOP BrainPOP’s topics, games, and teacher resources.

Social-Emotional Learning Collection : Continue to build understanding around empathy and respect with BrainPOP’s six-week SEL curriculum that addresses the five CASEL competencies.

Teacher Support Resources:

- Pause Point Overview : Video tutorial showing how Pause Points actively engage students to stop, think, and express ideas.

- Learning Activities Modifications : Strategies to meet ELL and other instructional and student needs.

- Learning Activities Support : Resources for best practices using BrainPOP.

Lesson Plan Common Core State Standards Alignments

- BrainPOP Jr. (K-3)

- BrainPOP ELL

- BrainPOP Science

- BrainPOP Español

- BrainPOP Français

- Set Up Accounts

- Single Sign-on

- Manage Subscription

- Quick Tours

- About BrainPOP

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Trademarks & Copyrights

Unit 2: Creating a Bully Free Environment Within Your School

Unit 2: The Role of Others

What are some of the emotions experienced by victims of cyberbullying? What are some commonalities they have and warning signs they show (if any)?

Unit 2 Objectives:

1. Students will be able to relate to the experiences endured by victims of cyberbullying.

2. Students will be able to recognize the chain reaction of events caused by cyberbullying.

3. Students will be able to analyze the experiences of various individuals in real life cyberbullying cases and hypothetical scenarios.

What Needs to be Completed by the End of Unit 2:

1. Read the introductory text and watch the PBS video about victims and their families.

2. Read the NY Times Article about parents struggling with the issue. Click here

3. Research two newspaper articles about two additional victims of cyberbullying and complete the corresponding questions.

4. Work within groups to read various scenarios related to cyberbullying and and answer a set of questions pertaining to each scenario.

Victims of Cyberbullying

Risk factors.

Cyberbullying is everywhere, and it really hurts. It makes you want to crawl in a hole and just stay there. It makes you feel like you are the only one and no one is out there to help you; no one can help you. - Shelby Anderson, Student, Springbank Middle School

To those people who say that it is nothing, that it is not a big deal and that it is teenagers being dramatic, that is completely wrong. It affects our lives enormously. The outcome of this harassment can lead to poor performance at school, low self-esteem and serious emotional consequences, including depression and suicide, so it is much more than just teenagers being dramatic. - Mariel Calvo, Student, Springback Middle School

Every day all across the nation, people are being cyberbullied in the comfort of their own homes. Often students who are being bullied at school go home with hopes of escaping, only to find that when they get on the Internet, the bullying continues. Like traditional bullying, much of cyberbullying is grounded in discrimination, ignorance and a lack of respect for the rights of others. People who belong to minority groups or who are perceived as different are especially vulnerable, such as those who have a disability, are overweight, are members of ethnic minority groups, or, in particular, those who identify as – or are perceived to be – lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgendered. It is important to remember that cyberbullying is not limited to just those who are perceived as different. Because of the anonymity associated with it, cyberbullies also tend to victimize those that they have had previous confrontations with or peers that they simply dislike.

Generally, children who are bullied have one or more of the following risk factors:

- Are perceived as different from their peers, such as being overweight or underweight, wearing different clothing, being new to a school, or being unable to afford what kids consider “cool”

- Are perceived as weak or unable to defend themselves

- Are depressed, anxious, or have low self esteem

- Are less popular than others and have few friends

- Do not get along well with others, seen as annoying or provoking, or antagonize others for attention

Warning Signs

There are many warning signs that may indicate that someone is affected by bullying—either being bullied or bullying others. Recognizing the warning signs is an important first step in taking action against bullying. Not all children who are bullied or are bullying others ask for help.

There isn’t much difference between cyberbullying and the effects of traditional bullying. Both cause significant emotional and psychological distress. In fact, just like any other victim of bullying, cyberbullied kids experience anxiety, fear, depression and low self-esteem. It is important to remember that cyberbullying has a CHAIN REACTION. Not only does the victim feel distress but the families of those bullied do as well!

But targets of cyberbullying also suffer from some unique consequences and negative feelings. Here are some of the common feelings cyberbullied teens and tweens often experience:

Feel overwhelmed.

Being targeted by cyberbullies can feel crushing especially if a lot of kids are participating in the bullying. Sometimes the stress of dealing with cyberbullying can cause kids to feel like the situation is more than they can handle.

Feel vulnerable and powerless.

Victims of cyberbullying often find it difficult to feel safe. Typically, this is because the bullying can invade their home through a computer or cell phone at any time of day. No longer do they have a place where they can escape. To a victim, it feels like the bullying is everywhere. Additionally, because the bullies can remain anonymous, this can escalate feelings of fear. Kids who are targeted have no idea who is inflicting the pain.

Feel exposed and humiliated.

Because cyberbullying occurs in cyberspace, the bullying often feels permanent. Kids know that once something is out there, it will always be out there. Additionally, when cyberbullying occurs the nasty messages or texts can be shared with multitudes of people. The sheer volume of people that know about the bullying can lead to intense feelings of humiliation.

Feel dissatisfied with who they are.

Cyberbullying often attacks victims where they are most vulnerable. As a result, targets of cyberbullying often begin to doubt their worth and value and no longer feel worthy. They may respond to these feelings by harming themselves in some way. For instance, if a girl is called fat, she may begin a crash diet with the belief that if she alters how she looks then the bullying will stop.

Feel angry and vengeful.

Sometimes victims of cyberbullying will get angry about what is happening to them. As a result, they will try to take revenge on the bully or bullies and engage in retaliation.

Feel disinterested in life.

When cyberbullying is ongoing, the victims often begin to relate to the world around them differently than others. For many, life can feel hopeless and meaningless. They begin to lose interest in things they once enjoyed and spend less and less time interacting with family and friends. And in some cases depression can set in.

Feel alone and isolated.

Cyberbullying often leads to teens being excluded and ostracized at school, which is particularly painful for teens because friends are crucial at this age. When kids don’t have friends, this can lead to more bullying.

Additionally, when cyberbullying occurs, most people recommend shutting off the computer or turning off the cell phone. But, for teens this often means cutting off communication with their world. Their phones and their computers are one of the most important ways they communicate with others. If that option for communication is removed they can feel secluded and cut off from their world.

Feel disinterested in school.

Cyberbullying victims often have much higher rates of absenteeism at school than non-bullied kids. They often skip school to avoid facing the kids bullying them or because they are embarrassed and humiliated by the messages that were shared. Their grades suffer too because they find it difficult to concentrate or study because of the anxiety and stress that the bullying causes. And in some cases, kids will either drop out of school or lose interest in continuing their education after high school.

Feel anxious and depressed.

Victims of cyberbullying often succumb to anxiety, depression and other stress-related conditions. This occurs primarily because cyberbullying erodes their self-confidence and self-esteem.

When kids are cyberbullied they often experience headaches, stomachaches or other physical ailments. The stress of bullying can also cause stress-related conditions like stomach ulcers and skin conditions. Also, kids who are cyberbullied may experience changes in eating habits like skipping meals or binge eating. And their sleep patterns may be impacted. They may suffer from insomnia, sleep more than usual or experience nightmares.

Feel suicidal.

Cyberbullying increases the risk of suicide. Kids that are constantly tormented by peers through text messages, instant messaging, social media and other outlets, often begin to feel hopeless. They may even begin to feel like the only way to escape the pain is through suicide. As a result, they may begin to fantasize about ending their life in order to escape their tormentors.

PBS Frontline: Digital Nation Video

Now please watch the following video clip from Frontline: Digital Nation about one boy's tragedy. PBS Frontline: Digital Nation

Newspaper Article Assignment

First read the NY Times Article about parents struggling to deal with cyberbullying. You can access the article here: NY Times Article

After reading the article, please search for two additional articles about victims of cyberbullying.Once you have read two articles, please answer the following questions in a Microsoft Word document. Save your Microsoft Word document and attach it next to your name here for others to view. Please answer the following questions about EACH article.

Article 1 Title:

Article Title:

Source (Online or print)ie: NY Times Online:

Website URL:

1) How was this victim bullied? Tell the story behind the bullying.

2) What warning signs (if any) did the victim show?

3) What were some of the effects of the harassment on the victim?

4) Did the victim report the bullying to anyone? If so, what did they do? If they didn’t report it, why didn’t they?

5) What ended up happening to the victim and the bully?

6) Please list anything else you feel to be important or pertinent to share about this individuals story.

Article 2 Title:

Source (Online or print) ie: NY Times Online:

- Once you have answered these questions, keep in mind what lessons can be learned from these stories! This will be useful to you later on in the mini course!!***

Within groups you will be assigned one or more of the following cyberbullying scenarios. Please read through your assigned scenario and then answer the following questions:

1) Who are the key players in this bullying scenario? What might have motivated this bully/these bullies to do what they did?

2) What role does technology play in this bullying scenario?

3) What other participants helped to facilitate this bullying? How?

4) What would you do if you heard this was happening to someone at your school?

5) How do you think this bullying may have affected the life of the student being bullied?

6) Do you think that the school could do anything to punish the bullies in this case? Why or why not?

Scenario #1:

In response to a dare, Cynthia secretly uses her phone to record video of Angela changing in the girls’ locker room after gym class.She posts the video to YouTube, adds a nasty comment about Angela, and sends the link to all of her friends, encouraging them to post similar anonymous comments.

Scenario #2:

Anthony’s girlfriend Melanie breaks up with him and begins dating his friend, John. Anthony begins sending daily text messages to both John and Melanie, calling Melanie nasty names and John a “traitor.” He also updates his own Facebook status everyday to reflect these same comments.

Scenario #3:

Brianna and her friend Jasmine are gossiping about another friend, Alicia, while instant messaging one night. Jasmine is angry with Alicia because of an argument they had earlier in the day, and airs her anger to Brianna, ranting about Alicia and calling her a variety of names. The next morning, Brianna has spread printouts of the instant message conversation all over the school and everyone including Alicia is reading the comments that Jasmine made in her private online conversation with Brianna.

Scenario #4:

William goes to the principal to turn in another boy, Allan, who has been dealing drugs in the school’s parking lot. Allan finds out that William has turned him in and sends him an email from his computer at home that night, threatening to physically harm him if he doesn’t go back to the principal and tell him that it was just a joke.

Scenario #5:

Christopher and Brian are a couple who decides to come out by attending the junior prom together. Over the weekend, a group of students create a “hate page” on Facebook with pictures of the two boys dancing at prom and a series of anti gay comments. By Monday morning, about 50 students have become “fans” of the page and have posted derogatory comments about the Christopher and Brian.

Scenario #6:

Ashley and Zach have been friends for a long time, but when Ashley tries to pursue a romantic relationship with Zach, he turns her down. As revenge, Ashley creates an online persona named “Christy” who frequents the forums and chatrooms that Zach enjoys. “Christy” makes a connection with Zach by claiming to share his interest in fantasy and science fiction literature and when it’s clear that Zach develops a crush on “Christy,” she then proceeds to insult Zach and make fun of him, using the personal information that Ashley knows about him to taunt him and make him feel bad about himself.

- AGAIN BE THINKING ABOUT COMMONALITIES YOU SEE THROUGHOUT, LESSONS YOU CAN TAKE AWAY, THIS WILL GUIDE YOUR LEARNING FOR THE REST OF THE COURSE!!** :) :) :)

ETAP 623 Fall 2013 - Wilde

Portfolio Page

Course Home: Creating a Bully Free Environment Within Your School

Unit 1: Introduction to Cyberbullying

Unit 3: The Role of Others

Unit 4: Creating a Bully Free Environment Within Your School

References and Resources

StopBullying.org

Cyberbullying Research Center

National Crime Prevention Council

Common Sense Media: Cyberbullying

Do Something-Cyberbullying

PBS Frontline: Digital Nation

NY Times Article

- Toggle limited content width

- Digital Education Strategies

Cyberbullying Lesson Plans: Teaching Your Students About Cyberbullying

- April 2, 2019

- No Comments

Just because it’s not happening in your classroom, that doesn’t mean bullying isn’t happening right under your nose. With technology making retail, information, and other conveniences easily accessible through a smartphone or any access to the internet, the same applies to communication with others. Unfortunately, some students and other children, teens, and even adults abuse this communication tool to bully others online, sometimes with the advantage of anonymity on their side.

As a teacher, you may have your own lesson plans or measures against bullying in the classrooms. Unfortunately, most teachers that teach against bullying have outdated ideas on the subject that what they tell their students may not apply to the way bullying is practiced today. While emotional, verbal, and physical bullying still exists in the classroom, the effects of cyberbullying are just as bad and degrading on students’ physical well-being, mental health, and overall self-esteem.

Lesson Summary

This lesson plan on cyberbullying focuses on two aspects: the bullied and the bully. For the first part, we talk about cyberbullying in general, how to spot if you’re being bullied, what to do, and measures your students can take against cyberbullying.

In the second part, we discuss what accounts as cyberbullying, when to know when your student is stepping over the line, and how to avoid cyberbullying others. This lesson plan is applicable to students of all ages, though some changes may be needed to adjust to your students’ level of maturity and your own teaching style.

Learning Objectives

This is a cyberbullying resource meant to help teachers learn about cyberbullying and how to effectively teach their students about avoiding being a bully as well as knowing what to do should they face a cyberbully of their own. After educating your students in cyberbullying, your students should be able to:

- Understand the characteristics of cyberbullying.

- Recognize when they are being cyberbullied by their classmates.

- Perform the appropriate action against cyberbullies.

- Avoid cyberbullying their classmates.

Background on Cyberbullying

Before the internet became a ubiquitous part of students’ lives, bullies from both male and female students have existed for a long time. From the stereotypical jocks who bully the less physically fit students, to the mean girls who look down on everyone outside their clique, bullies exist for a number of reasons, both having to do with internal and external factors of the bullies themselves.

For bullying to occur, there has to be habitual and repeated actions against the victim. For example, let’s take two students, Alex and Billy. If Alex bumps into Billy along a crowded hallway and Billy angrily pushes Alex so hard that Alex falls to the floor, then this isn’t bullying. Billy may have difficulty controlling his temper and reacting to negative situations and may get into trouble for this if Alex is physically injured or if Billy refuses to apologize, but the fact that Billy wouldn’t actively seek out Alex to hurt him another time makes this an example of non-bullying.

But if Billy decides to tease, shove, and threaten Alex with physical violence if Alex doesn’t give him money, then this is a form of bullying. Based on US legislation, regardless of which state the two live in, if Alex reports Billy to school authorities and Billy is found guilty of bullying, the school can use state legislation to punish Billy – often this leads to suspending kids like him. In worst cases, a bully may even be forced to leave the school permanently.

Legislation on Bullying

As of 2019, all 50 states have anti-bullying legislation. Georgia was the first state to create laws against school and workplace bullying in 1999, while Montana was the last state to implement laws in 2015. While all the laws generally ban bullying from schools, some legislations are stricter than others.

New Jersey currently has the strictest bullying legislation in the country, as every case of bullying (from simple teasing to severe physical and emotional bullying) must be reported to the state authorities. These authorities grades every school in the state based on their anti-bullying policies, the number of bullying incidents that have occurred in the school, and how the school plans to effectively deal with each bullying case. All school faculty are required to treat every reported bullying case seriously, and bullies may be suspended or even expelled for cases ranging from minor to major.

Cyberbullying

Also known as online bullying and cyber harassment, cyberbullying takes the verbal and emotional bullying and makes it easier for the bully to reach out to their victim because of the ease of communication provided by the internet. As such, it is arguably more dangerous as cyberbullying has the effects of traditional bullying but sometimes without the witnesses or jurisdiction provided by a student’s home or school.

If Alex were bullied in school, someone would be bound to see it or news would eventually make its way to a faculty member or school administrator. If someone were to bully Alex outside his home or inside by one of his siblings, all Alex would have to do is call for a parent who will diffuse the situation and protect Alex from the trauma of bullying.

In cyberbullying, however, the forms of communication make it difficult for Alex to seek help. If someone sends him a hateful message, he may feel like his parents are powerless to stop it as they can’t do anything about it. Since this is outside of school hours, he may also believe that the school has no power to do anything said to him online. It’s even possible that Alex’s bullies use anonymous accounts.

Effects of Cyberbullying

Just because it’s happening online doesn’t mean it won’t have any effect on a student. In fact, it can have long-term consequences on the victim, including a lower self-esteem, depression, suicidal tendencies, and emotional damage.

If Alex faces frequent cyberbullying, you may find that his demeanor at home and school can change drastically. He becomes more scared, frustrated, angry, and depressed, and because this is happening online, he might think he has no outlet to deal with his bully. Unlike a bully at school who can be reported and who Alex doesn’t have to see outside of school hours, Alex can see the taunts of a cyberbully each time he opens his social media accounts.

In worst cases, a victim of bullying may be driven to commit suicide. In 2012, a 15-year old girl named Amanda Todd was driven to kill herself due to the cyberbullying. Her bully followed her for years, sending compromising photos of her to everyone in her school and blackmailing her. Eventually, Todd was driven to kill herself by hanging after suffering anxiety, depression, and panic disorders. Prior to her suicide, she practiced self-mutilation and tried to commit suicide once by drinking bleach, but was rescued.

At this point, you’ll want your students to understand the severity of cyberbullying. Those who are experiencing cyberbullying need to understand that this isn’t just something they can continue to tolerate. On the other hand, those that are aware that they bully others need to understand how far the effects of their bullying can go.

For the Bullied Students

Why Do Cyberbullies Bully?

Your lesson plan must start by answering with the “why?” portion, especially if you’re teaching younger students. Often, we’re told that people are supposed to be nice to each other, so you have to explain why some students in their school (or even in your very classroom) are being excessively mean.

You have the free reigns of providing students with an answer you see fit. However, you must never answer in such a way that bullying is justified. If the victim is a girl and the bully is a boy, you can’t just dismiss the boy’s action and say “boys will be boys.” It’s time to end the mindset that a boy’s actions towards a girl should be accepted because “they secretly like her” or because he’s much rowdier than girls are.

In general, bullies exist because of an imbalance of social or physical power, among other factors. A “jock” may have more physical strength, and his act of physically harming a weaker student asserts his dominance over students who relate more with the victim that the jock’s own peers.

One way of explaining bullies is using animal analogies. If you look at other animals like monkeys, you can see that there is a social hierarchy there. Monkeys fight for power or position, and for a monkey to assert their dominance, they have to appear more physically and verbally more intimidating than others around him.

Some people seem to portray this behavior as well, even though it’s not necessary in a civilized community. By asserting their dominance through their actions, they’re getting the message that they’re someone you shouldn’t mess with. However, there are some people they cannot bully to assert their dominance – such as faculty, staff, and people within their circles – so to assert their dominance and avoid looking insecure, they find someone significantly weaker in terms of physical or social status.

Cyberbullying is just a byproduct of bullying throughout the years. Why stop in the playground when the internet now provides easy communication to anyone? Because of this, bullies can now bully even more efficiently any time of the day. They may even bully a victim anonymously, thus avoiding the consequences of getting caught all the while degrading their victim’s will.

Recognizing Cyberbullying Tactics

Your students can find cyberbullying through texting, social media, gaming, or any virtual place where communication is possible. It’s not always limited to the messages sent to your students, but also other people who send or write about nasty comments online about your student.

There are times when your student may have a friend or acquaintance with just mean-spirited humor, but there’s a fine line between joking around and cyberbullying. Make sure your student watches out for the following tactics and some examples:

- When the bully post comments or rumors that are hurtful or embarrassing (e.g. Billy tells everyone that Alex can’t afford to study because he’s too poor)

- Telling someone to kill themselves (Billy tells Alex he is a waste of space and should just die)

- Posting mean pictures or videos (Billy uploads a photoshopped photo of Alex on a fat naked man’s body)

- Posting hateful names or content discriminating a person’s identity (Billy making fun of Alex for being ugly)

- Creating a webpage dedicated to mocking someone

- Leaking a person’s private information available to the public (Billy gives away Alex’s phone number, credit card numbers, etc.)

- Sharing compromising photos of any person (Billy sends a nude photo of his ex-girlfriend)

These are not the only ways cyberbullying happens; you’d be surprised how creative bullies can get when they want to bully their targets.

What Happens When You’re Cyberbullied?

Show your students the effects of keeping silent. If you’re exposed to cyberbullying for a long time and nothing is done to stop the bully, you may not realize it, but your mind reacts to the bullying accordingly, slowly changing your personality.

- A student may be emotionally distraught after accessing the internet. They then project their negative emotions towards the people around them.

- They suddenly become more secretive with their friends and families about what they do online. They may also start withdrawing from social gatherings in school or within the family.

- Their distraction may cause them to perform poorly in school.

- When they get texts or messages, they tend to get nervous (Is it Billy? Is it my mom?)

What Children Need to Know

While social media is neither a part of the school or the home, a child’s well-being is the responsibility of both parents and the school. A child needs to understand that their parents and school authorities have the power to stop the bullying even if it is virtual.

We’re in an age where we’ve become so dependent on technology that you can’t tell your students to just avoid social media to stay away from the bullies. Don’t make your student believe they have to adjust and the bully gets away scot-free and continues to stay on social media.

The first thing your students have to understand is that bullying is not their fault. The fact that they have a bully says more about the bully than the student. Let them know that talking to a teacher or parent is the first and most responsible thing they can do.

While lesson plans on cyberbullying may be a bit outdated, the legislation I mentioned means that schools have provisions on cyberbullying and handling it. Some stricter schools may even get the help of local authorities to track down anonymous bullies.

A bullied student must also learn how to handle the bully or bullies. It may seem like a good idea to fight back, but what your child should do is keep a record of these messages or posts which can be used as evidence against the bully.

For the Bullies

On the other side of the bullying resource is for students who are bullies, whether they know it or not. For some, teasing and mean jokes may be harmless fun. But what is fun for them may already be distressing for the person who becomes the victim.

Peer Pressure

It’s actually possible that your student has become the bully, whether they know it or not. Herd mentality is very prevalent in schools, which is people, even if they know they are doing something wrong, may continue to act that way because they’re influenced by the way others thing and are pressured to act the same way.

Let’s say that Billy continues to bully Alex. He makes snide jokes about Alex in class, some of which make the rest of the students laugh. Billy continues to bully Alex online, publicly and for everyone to see. Chuckie is a classmate who begins to see that people are partaking in ridiculing Alex. So, he thinks there’s no harm in being in the joke and joins in. Chuckie thinks this is all just fun and games, when really, he’s actually become a bully himself.

Recognizing You Are the Bully

We all think we’re the heroes of our own stories, so it’s difficult for some people to accept that they are the bully. Encourage your students that it’s never too late to do the right thing, and if a student realizes that they’ve committed cyberbullying, the best thing they can do is apologize and actively make sure they never do it again.

This is the best case scenario. However, in more severe cases, there are some bullies who are actively aware that what they are doing is wrong but they continue to bully their classmate. In some cases, these children are actually a product of their own problems at home and at school. Because they cannot project their anger at the root cause, they’ve decided to take it out on their weaker classmates. Talking to a counselor can help them understand whether or not that have unresolved anger issues or need an outlet to divert their strong negative emotions.

In other cases, a child may bully others as a result of entitlement. In such case, you may need the help of their parents to enforce rules. Restricting their social media use or internet use only for academic purposes can help them understand how they need to be responsible when communicating with others online.

In all cases, though, never let a bully’s actions go unpunished. Your student may be a genius, a gifted athlete, or one of the best students you know, but never let that be the reason that they get away scot-free. Otherwise, it will be hard for them to understand the consequences of their actions as they’re given a pass for their negative traits.

Tips for Teachers

- Teaching these lessons to your students is pointless if they think you are unwelcoming or unwilling to help them should they ever come to you for help. Make a habit to stress that you are always willing to lend an ear and will act appropriately when they report cyberbullying.

- Sometimes, you may need to be the one who approaches your student and ask what is wrong. Often, they may not tell you what is bothering them. Do not force them to tell you, but at the same time, don’t give up when you know something is wrong. Allow them to feel safe in your presence; chances are, they’ll eventually admit what is really bothering them.

- In serious cases, be ready to contact your student’s parents or guardians. If you feel like they’re likely to do something drastic to stop the bullying inform school authorities immediately.

Cyberbullying is a serious form of bullying that makes your students feel unsafe, whether at home or in school. Teach your students the right way to deal with cyberbullying, and remind those guilty of cyberbullying that their actions can drastically harm their classmates and schoolmates in the long run.

Like this article?

- My Storyboards

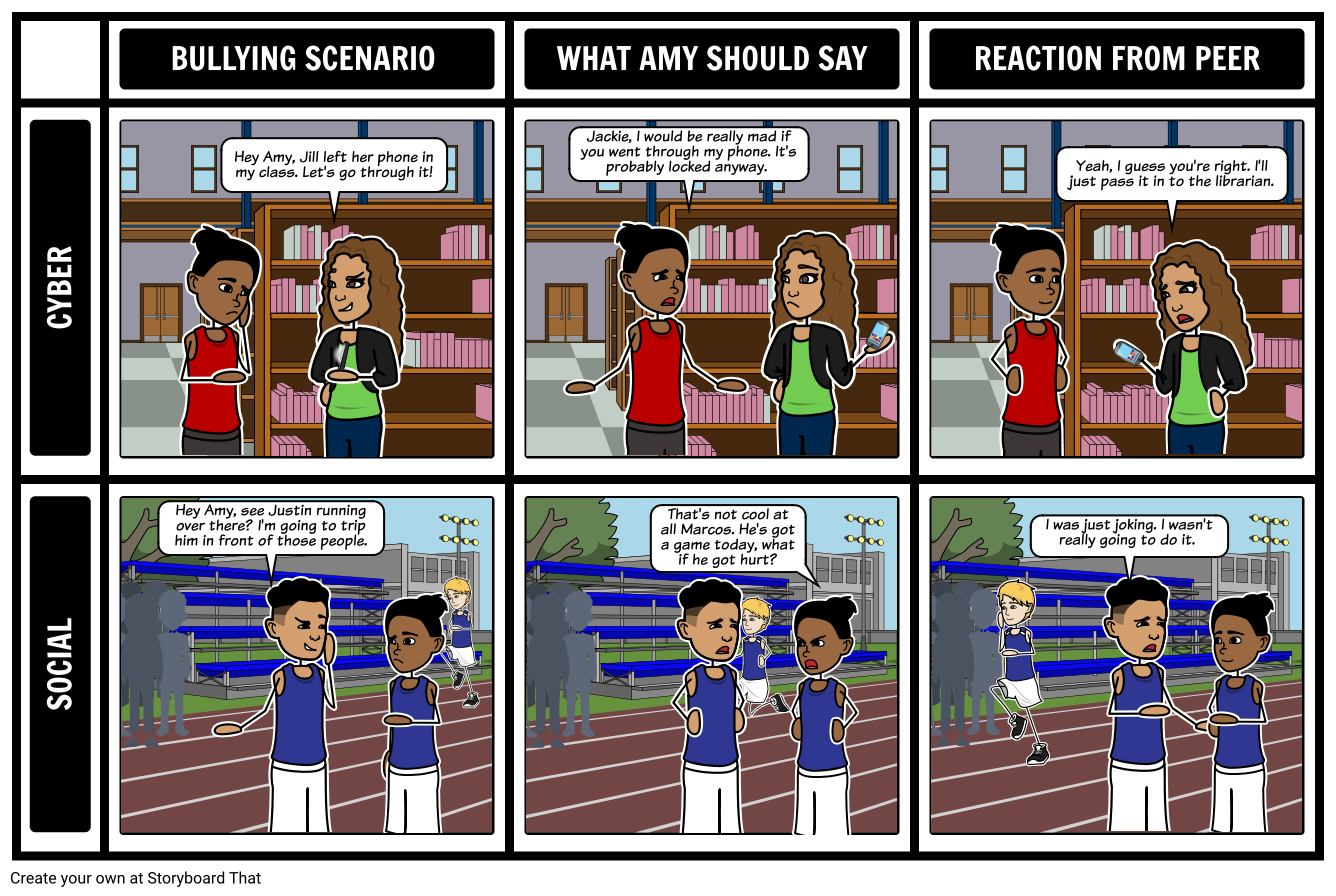

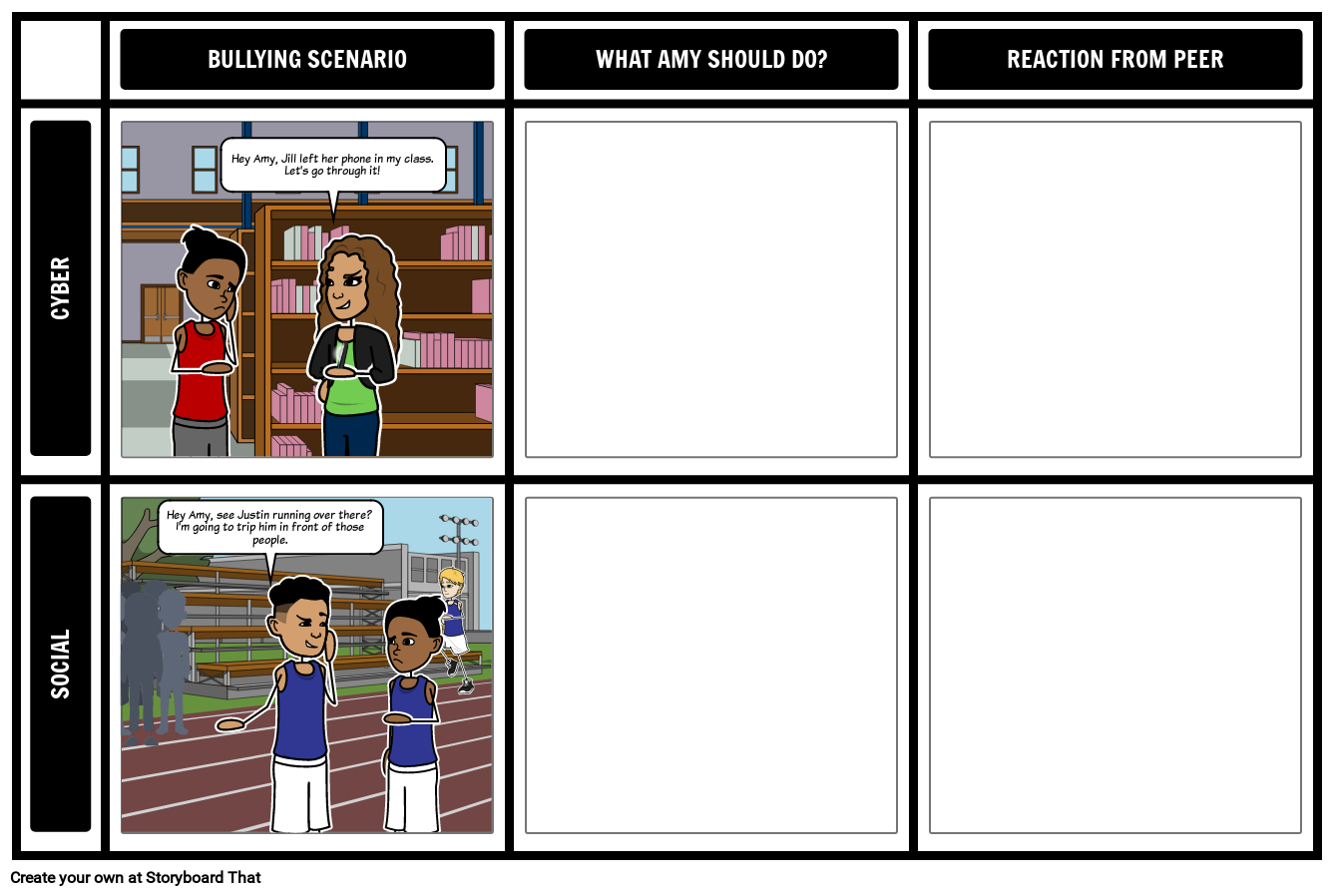

Practicing Scenarios: What Should Amy Say?

In this activity, activity overview, template and class instructions, more storyboard that activities.

- This Activity is Part of Many Teacher Guides

Use this lesson plan with your class!

At times, students will be a bystander to someone being bullied. They will be faced with the decision to either stand by and watch or step up and stop it. We do not want our students to accept that bullying is a norm, none of their business, or think, "At least it’s not me." We want them to step up to bullying and help their peers.

In this activity, students will practice stepping up to bullying. The provided example will show two types of bullying, cyberbullying and social bullying. The students will show how they can step up as Amy, our main character, in the scenarios . Please feel free to adjust the examples to fit your needs. The goal of this activity is to give students the confidence to stand up in tough situations and help them practice possible responses.

(These instructions are completely customizable. After clicking "Copy Activity", update the instructions on the Edit Tab of the assignment.)

Student Instructions

You’ll be stepping up to bullying with Amy while creating storyboards!

- Click "Start Assignment".

- Read the bullying scenarios that have been done for you.

- Have Amy step up and stop the bullying in the next cells.

- In the third column, create what the reaction should be from Amy’s peer.

Lesson Plan Reference

Grade Level 6-12

Difficulty Level 2 (Reinforcing / Developing)

Type of Assignment Individual

Type of Activity: School Bullying

(You can also create your own on Quick Rubric .)

| Proficient | Emerging | Beginning | |

|---|---|---|---|

Anti Bullying Activities

Pricing for Schools & Districts

Limited Time

- 5 Teachers for One Year

- 1 Hour of Virtual PD

30 Day Money Back Guarantee • New Customers Only • Full Price After Introductory Offer • Access is for 1 Calendar Year

- Thousands of images

- Custom layouts, scenes, characters

- And so much more!!

Create a Storyboard

Introductory School Offer

30 Day Money Back Guarantee. New Customers Only. Full Price After Introductory Offer. Access is for 1 Calendar Year

Generating a Quote

This is usually pretty quick :)

Quote Sent!

Email Sent to

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Cyberbullying: Everything You Need to Know

- Cyberbullying

- How to Respond

Cyberbullying is the act of intentionally and consistently mistreating or harassing someone through the use of electronic devices or other forms of electronic communication (like social media platforms).

Because cyberbullying mainly affects children and adolescents, many brush it off as a part of growing up. However, cyberbullying can have dire mental and emotional consequences if left unaddressed.

This article discusses cyberbullying, its adverse effects, and what can be done about it.

FangXiaNuo / Getty Images

Cyberbullying Statistics and State Laws

The rise of digital communication methods has paved the way for a new type of bullying to form, one that takes place outside of the schoolyard. Cyberbullying follows kids home, making it much more difficult to ignore or cope.

Statistics

As many as 15% of young people between 12 and 18 have been cyberbullied at some point. However, over 25% of children between 13 and 15 were cyberbullied in one year alone.

About 6.2% of people admitted that they’ve engaged in cyberbullying at some point in the last year. The age at which a person is most likely to cyberbully one of their peers is 13.

Those subject to online bullying are twice as likely to self-harm or attempt suicide . The percentage is much higher in young people who identify as LGBTQ, at 56%.

Cyberbullying by Sex and Sexual Orientation

Cyberbullying statistics differ among various groups, including:

- Girls and boys reported similar numbers when asked if they have been cyberbullied, at 23.7% and 21.9%, respectively.

- LGBTQ adolescents report cyberbullying at higher rates, at 31.7%. Up to 56% of young people who identify as LGBTQ have experienced cyberbullying.

- Transgender teens were the most likely to be cyberbullied, at a significantly high rate of 35.4%.

State Laws

The laws surrounding cyberbullying vary from state to state. However, all 50 states have developed and implemented specific policies or laws to protect children from being cyberbullied in and out of the classroom.

The laws were put into place so that students who are being cyberbullied at school can have access to support systems, and those who are being cyberbullied at home have a way to report the incidents.

Legal policies or programs developed to help stop cyberbullying include:

- Bullying prevention programs

- Cyberbullying education courses for teachers

- Procedures designed to investigate instances of cyberbullying

- Support systems for children who have been subject to cyberbullying

Are There Federal Laws Against Cyberbullying?

There are no federal laws or policies that protect people from cyberbullying. However, federal involvement may occur if the bullying overlaps with harassment. Federal law will get involved if the bullying concerns a person’s race, ethnicity, national origin, sex, disability, or religion.

Examples of Cyberbullying

There are several types of bullying that can occur online, and they all look different.

Harassment can include comments, text messages, or threatening emails designed to make the cyberbullied person feel scared, embarrassed, or ashamed of themselves.

Other forms of harassment include:

- Using group chats as a way to gang up on one person

- Making derogatory comments about a person based on their race, gender, sexual orientation, economic status, or other characteristics

- Posting mean or untrue things on social media sites, such as Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram, as a way to publicly hurt the person experiencing the cyberbullying

Impersonation

A person may try to pretend to be the person they are cyberbullying to attempt to embarrass, shame, or hurt them publicly. Some examples of this include:

- Hacking into someone’s online profile and changing any part of it, whether it be a photo or their "About Me" portion, to something that is either harmful or inappropriate

- Catfishing, which is when a person creates a fake persona to trick someone into a relationship with them as a joke or for their own personal gain

- Making a fake profile using the screen name of their target to post inappropriate or rude remarks on other people’s pages

Other Examples

Not all forms of cyberbullying are the same, and cyberbullies use other tactics to ensure that their target feels as bad as possible. Some tactics include:

- Taking nude or otherwise degrading photos of a person without their consent

- Sharing or posting nude pictures with a wide audience to embarrass the person they are cyberbullying

- Sharing personal information about a person on a public website that could cause them to feel unsafe

- Physically bullying someone in school and getting someone else to record it so that it can be watched and passed around later

- Circulating rumors about a person

How to Know When a Joke Turns Into Cyberbullying

People may often try to downplay cyberbullying by saying it was just a joke. However, any incident that continues to make a person feel shame, hurt, or blatantly disrespected is not a joke and should be addressed. People who engage in cyberbullying tactics know that they’ve crossed these boundaries, from being playful to being harmful.

Effects and Consequences of Cyberbullying

Research shows many negative effects of cyberbullying, some of which can lead to severe mental health issues. Cyberbullied people are twice as likely to experience suicidal thoughts, actions, or behaviors and engage in self-harm as those who are not.

Other negative health consequences of cyberbullying are:

- Stomach pain and digestive issues

- Sleep disturbances

- Difficulties with academics

- Violent behaviors

- High levels of stress

- Inability to feel safe

- Feelings of loneliness and isolation

- Feelings of powerlessness and hopelessness

If You’ve Been Cyberbullied

Being on the receiving end of cyberbullying is hard to cope with. It can feel like you have nowhere to turn and no escape. However, some things can be done to help overcome cyberbullying experiences.

Advice for Preteens and Teenagers

The best thing you can do if you’re being cyberbullied is tell an adult you trust. It may be challenging to start the conversation because you may feel ashamed or embarrassed. However, if it is not addressed, it can get worse.

Other ways you can cope with cyberbullying include:

- Walk away : Walking away online involves ignoring the bullies, stepping back from your computer or phone, and finding something you enjoy doing to distract yourself from the bullying.

- Don’t retaliate : You may want to defend yourself at the time. But engaging with the bullies can make matters worse.

- Keep evidence : Save all copies of the cyberbullying, whether it be posts, texts, or emails, and keep them if the bullying escalates and you need to report them.

- Report : Social media sites take harassment seriously, and reporting them to site administrators may block the bully from using the site.

- Block : You can block your bully from contacting you on social media platforms and through text messages.

In some cases, therapy may be a good option to help cope with the aftermath of cyberbullying.

Advice for Parents

As a parent, watching your child experience cyberbullying can be difficult. To help in the right ways, you can:

- Offer support and comfort : Listening to your child explain what's happening can be helpful. If you've experienced bullying as a child, sharing that experience may provide some perspective on how it can be overcome and that the feelings don't last forever.

- Make sure they know they are not at fault : Whatever the bully uses to target your child can make them feel like something is wrong with them. Offer praise to your child for speaking up and reassure them that it's not their fault.

- Contact the school : Schools have policies to protect children from bullying, but to help, you have to inform school officials.

- Keep records : Ask your child for all the records of the bullying and keep a copy for yourself. This evidence will be helpful to have if the bullying escalates and further action needs to be taken.

- Try to get them help : In many cases, cyberbullying can lead to mental stress and sometimes mental health disorders. Getting your child a therapist gives them a safe place to work through their experience.

In the Workplace

Although cyberbullying more often affects children and adolescents, it can also happen to adults in the workplace. If you are dealing with cyberbullying at your workplace, you can:

- Let your bully know how what they said affected you and that you expect it to stop.

- Keep copies of any harassment that goes on in the workplace.

- Report your cyberbully to your human resources (HR) department.

- Report your cyberbully to law enforcement if you are being threatened.

- Close off all personal communication pathways with your cyberbully.

- Maintain a professional attitude at work regardless of what is being said or done.

- Seek out support through friends, family, or professional help.

Effective Action Against Cyberbullying

If cyberbullying continues, actions will have to be taken to get it to stop, such as:

- Talking to a school official : Talking to someone at school may be difficult, but once you do, you may be grateful that you have some support. Schools have policies to address cyberbullying.

- Confide in parents or trusted friends : Discuss your experience with your parents or others you trust. Having support on your side will make you feel less alone.

- Report it on social media : Social media sites have strict rules on the types of interactions and content sharing allowed. Report your aggressor to the site to get them banned and eliminate their ability to contact you.

- Block the bully : Phones, computers, and social media platforms contain options to block correspondence from others. Use these blocking tools to help free yourself from cyberbullying.

Help Is Available

If you or someone you know are having suicidal thoughts, dial 988 to contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect with a trained counselor. To find mental health resources in your area, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 800-662-4357 for information.

Cyberbullying occurs over electronic communication methods like cell phones, computers, social media, and other online platforms. While anyone can be subject to cyberbullying, it is most likely to occur between the ages of 12 and 18.

Cyberbullying can be severe and lead to serious health issues, such as new or worsened mental health disorders, sleep issues, or thoughts of suicide or self-harm. There are laws to prevent cyberbullying, so it's essential to report it when it happens. Coping strategies include stepping away from electronics, blocking bullies, and getting.

Alhajji M, Bass S, Dai T. Cyberbullying, mental health, and violence in adolescents and associations with sex and race: data from the 2015 youth risk behavior survey . Glob Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X19868887. doi:10.1177/2333794X19868887

Cyberbullying Research Center. Cyberbullying in 2021 by age, gender, sexual orientation, and race .

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: StopBullying.gov. Facts about bullying .

John A, Glendenning AC, Marchant A, et al. Self-harm, suicidal behaviours, and cyberbullying in children and young people: systematic review . J Med Internet Res . 2018;20(4):e129. doi:10.2196/jmir.9044

Cyberbullying Research Center. Bullying, cyberbullying, and LGBTQ students .

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: StopBullying.gov. Laws, policies, and regulations .

Wolke D, Lee K, Guy A. Cyberbullying: a storm in a teacup? . Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(8):899-908. doi:10.1007/s00787-017-0954-6

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: StopBullying.gov. Cyberbullying tactics .

Garett R, Lord LR, Young SD. Associations between social media and cyberbullying: a review of the literature . mHealth . 2016;2:46-46. doi:10.21037/mhealth.2016.12.01

Nemours Teens Health. Cyberbullying .

Nixon CL. Current perspectives: the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health . Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2014;5:143-58. doi:10.2147/AHMT.S36456

Nemours Kids Health. Cyberbullying (for parents) .

By Angelica Bottaro Bottaro has a Bachelor of Science in Psychology and an Advanced Diploma in Journalism. She is based in Canada.

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

- About Digital Citizenship

- Digital Citizenship Curriculum

- Digital Citizenship (U.K.)

- Lesson Collections

- All Lesson Plans

- Digital Life Dilemmas

- SEL in Digital Life Resource Center

- Implementation Guide

- Toolkits by Topic

- Digital Citizenship Week

- Digital Connections (Grades 6–8)

- Digital Compass™ (Grades 6–8)

- Digital Passport™ (Grades 3–5)

- Social Media TestDrive (Grades 6–8)

AI Literacy for Grades 6–12

- All Apps and Websites

- Curated Lists

- Best in Class

- Common Sense Selections

- About the Privacy Program

- Privacy Evaluations

- Privacy Articles

- Privacy Direct (Free download)

- Free Back-to-School Templates

- 21 Activities to Start School

- AI Movies, Podcasts, & Books

- Learning Podcasts

- Books for Digital Citizenship

- ChatGPT and Beyond

- Should Your School Have Cell Phone Ban?

- Digital Well-Being Discussions

- Supporting LGBTQ+ Students

- Offline Digital Citizenship

- Teaching with Tech

- Movies in the Classroom

- Social & Emotional Learning

- Digital Citizenship

- Tech & Learning

- News and Media Literacy

- Common Sense Recognized Educators

- Common Sense Education Ambassadors

- Browse Events and Training

- AI Foundations for Educators

- Digital Citizenship Teacher Training

- Modeling Digital Habits Teacher Training

- Student Privacy Teacher Training

Training Course: AI Foundations for Educators

Earn your Common Sense Education badge today!

- Family Engagement Toolkit

- Digital Citizenship Resources for Families

Family Tech Planners

Family and community engagement program.

- Workshops for Families with Kids Age 0–8

- Workshops for Middle and High School Families

- Kids and Tech Video Series

- Get Our Newsletter

Follow our Instagram account for educators!

Keep up with the latest media and tech trends, and all of our free resources for teachers!

Teachers' Essential Guide to Cyberbullying Prevention

Topics: Social & Emotional Learning Cyberbullying, Digital Drama & Hate Speech Digital Citizenship

What is cyberbullying? How common is it? And what can teachers do about it? Get advice and resources to support your students.

What is cyberbullying.

- What forms can cyberbullying take?

How common is cyberbullying?

How can i tell if a student is being cyberbullied, when and how should i intervene in a cyberbullying situation, what's my responsibility as a teacher in preventing cyberbullying, what lesson plans and classroom resources are available to address cyberbullying.

- How can teachers work with families to prevent and identify cyberbullying?

Cyberbullying is the use of digital media (such as apps, text messages, and websites) to intimidate, upset, or harm someone. It includes repeatedly sending, posting, or sharing negative, harmful, or mean content about someone else on purpose.

Usually, with cyberbullying, there are other people who see cyberbullying happen. In these situations, people can be bystanders, allies , or upstanders .

- A bystander observes the conflict or unacceptable behavior but does not take part in it.

- An ally is someone who responds to the bullying situation by supporting the person being bullied (checking in with them, being a friend to them, etc.).

- An upstander tries to stop the bullying by directly confronting the person who is doing the bullying or by telling a trusted adult.

Cyberbullying differs from face-to-face bullying in several key ways. For one, it can feel harder to escape because it can happen anywhere, anytime. It's also harder to detect because so much of kids' digital media use is not monitored by adults. At the same time, cyberbullying can also be very public: Large numbers of people online can see what's happening and even gang up on the target. Though the target is usually exposed publicly, the people doing the cyberbullying can hide who they are by posting anonymously or using pseudonyms. And since cyberbullying isn't face-to-face, the one doing the bullying may not see or even understand the implications of their actions.

What Forms Can Cyberbullying Take?

Unfortunately, cyberbullying can take many forms . As popular social media apps for young people shift and proliferate, so have the ways kids can harass each other—or become victims themselves. Spreading rumors, sending hateful messages, or sharing embarrassing materials can occur across platforms and devices, but there are some other specific forms of cyberbullying to be aware of:

- Catfishing : Someone sets up a fictional persona online to compromise a victim in various ways, often exploiting a victim's emotions. The perpetrator's goals may be to lure them into a relationship or to intentionally upset a victim, among other reasons.

- Cyberflashing : When someone receives an unsolicited sexually graphic image, they've been cyberflashed. This can occur on peer-to-peer Wi-Fi networks or Bluetooth Airdrop , in or outside of school.

- Ghosting : When people cut off online contact and stop responding, they might be ghosting. Refusing to answer someone's messages can actually be a way of communicating a shift or upheaval among a group of friends. Often, instead of ever addressing the issue head-on, people will just ignore the targeted person.

- Griefing : There are people who harass or irritate you in multiplayer video games. They kill your character on purpose, steal your game loot, or harass you in chat. Repeated behavior like that is called "griefing."

- Hate pages : On platforms like Instagram , teens may create fake accounts to harass victims, posting unflattering photos of their target, exposing secrets, or sharing screenshots of texts from people saying mean things. It's hard to trace who created the account, and the people doing the bullying can simply create a new "hate" page if one is shut down or removed. Sometimes, these anonymous accounts may be collections focused on rumors or other malicious materials targeting students schoolwide.

- Outing : This occurs when someone reveals someone's gender identity or sexual orientation without their consent. What makes this particularly malicious is the risk this may pose for teens who report higher levels of mental health struggles and are at greater risk for self-harm.

Note that kids and teens probably use all kinds of terminology to describe the digital drama or harassment that's happening, so it's best to just ask questions than to use specific terms.

Reported data on how many kids experience cyberbullying can vary depending on the age of kids surveyed and how cyberbullying is defined. According to a 2022 Pew Research report on teens and cyberbullying, nearly half (46%) of teens reported experiencing at least one type of cyberbullying , and 28% have experienced multiple types, which represents a steady uptick over the last 15 years.

A summary of research by the Cyberbullying Research Center on cyberbullying in middle and high school from 2007 to 2021 indicated that, on average, 29% of students had been targets of cyberbullying. Nearly 16% of students admitted to cyberbullying others.

Yet not all groups of teens are experiencing cyberbullying equally, as some kids are more vulnerable than others . The Common Sense study " Social Media, Social Life " also found that girls are more likely than boys to experience it. A separate study showed that kids with a disability, with obesity, or who are LGBTQ are more likely to be cyberbullied than other kids.

Even if kids aren't the target of cyberbullying (and the majority aren't), chances are high they've witnessed it, since it often happens online and publicly. Common Sense reports that 23% of teens have tried to help someone who has been cyberbullied, such as by talking with the person who was cyberbullied, reporting it to adults, or posting positive stuff about the person being cyberbullied.

Be aware of your students' emotional state. Do they seem depressed? Fearful? Distracted? Pay attention to what's happening for students socially at lunchtime, in the hallways, or in other areas of your school campus. Has their friend group changed? Do you sense a conflict between students? Are you overhearing talk about "drama" or "haters" (two words kids might use to describe cyberbullying situations)? Don't be afraid to check in with students directly about what's going on. And reach out to their support networks, including parents or caregivers, the school counselor, a coach, or other teachers.

Obviously, cyberbullying is something to take seriously. At the same time, it's important to remember that, depending on their ages, kids are still developing skills like empathy, self-regulation, and how to communicate respectfully online. These situations can be learning opportunities for everyone involved.

School, district, and/or state policies might determine what actions you take once you've verified that cyberbullying has in fact occurred. Sometimes the recommended response is different depending on whether the bullying occurred on a school-issued device, and whether it happened outside of school hours or during the school day. Be sure to involve the students' families, school administrators, and counselor as appropriate, to ensure the intervention is effective and follows policy.

Here are a few resources to support teachers and schools in responding to cyberbullying:

- Helping Students Deal with Cyberbullying (NEA)

- Cyberbullying Fact Sheet: Identification, Prevention, and Response (Cyberbullying Research Center)

- Bullying: What Educators Can Do About It (PennState Extension)

- Responding to Cyberbullying: Guidelines for Administrators ( The No Bully School Partnership )

As educators, it's our responsibility to teach students how to use digital media in respectful and safe ways. This includes helping kids learn how to identify, respond to, and avoid cyberbullying. Given the demands on teachers to meet school, district, and state goals, it can be a challenge to figure out where these lessons fit into the school day. Fortunately, as technology becomes part of every aspect of our lives, including how we teach and learn, more schools and districts are giving teachers the time and resources to prioritize these skills. Here are a few ways to approach cyberbullying prevention in the classroom: