- Nieman Foundation

- Fellowships

To promote and elevate the standards of journalism

Nieman News

Back to News

Strictly Q&A

February 24, 2023, auschwitz stories told by those who lived them, the director of the auschwitz-birkenau state museum in poland has collected hundreds of survivor testimonials, told with a rawness that no outsider could.

By Andrea Pitzer

Tagged with

The gate into the Auschwitz concentration camp in WWII Nazi-occupied Poland. Translated, the words say "Work sets you free." Frederick Wallace via Unsplash

Piotr Cywiński

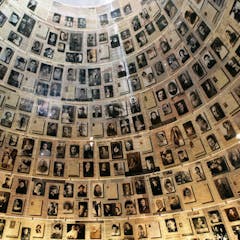

“ Auschwitz: A Monograph on the Human ,” a 2022 book by Piotr Cywiński, tries to address that abyss. He does so not by working his way along the boundaries around Auschwitz — the dates and architecture of genocide that swallowed more than a million people , the overwhelming majority of them Jewish — but instead dives into the emptiness itself, gathering details from hundreds of memoirs and official testimonies, along with trial minutes and questionnaires. Chronology doesn’t serve as the organizing principle; instead, the book is divided into themes of human emotion and experience, such as “Decency,” “Hierarchy,” and “Fear” that emerged from looking at the survivors’ accounts as a whole.

Cywiński is a historian and has been the director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Poland for more than 16 years. His polyphonic approach of bringing in hundreds of voices to tell one overarching story struck me as an answer to the question of how to write about something as vast as incomprehensible as Auschwitz.

This focus made me think of Pulitzer winner Katherine Boo who, in talking about her book “Behind the Beautiful Forevers,” balked at the idea of the journalistic impulse to make an individual a symbol of a place or an event. In a 2012 interview Poynter.org, she warned of the dangers of using one person’s story to represent a bigger concept:

“Nobody is representative. That’s just narrative nonsense. People may be part of a larger story or structure or institution, but they’re still people. Making them representative loses sight of that.”

Cywiński’s Auschwitz monograph illustrates this idea elegantly, gathering related observations with care then ceding nearly all his book to camp prisoners themselves, letting their archival testimonies converse with one another, with minimal interpretation and explanation.

Last December, more than 80 years after Nazis first sent prisoners to the small town of Oświęcim in Poland, Cywiński sat for a public interview with me at the Kosciuszko Foundation in New York. We spoke about why some stories went untold for decades, why understanding life at Auschwitz remains almost impossible and why it’s important to include a multitude of perspectives to even begin to glimpse the real story of Auschwitz.

Here are some excerpts from our conversation, which have been condensed and edited for clarity:

Train tracks that lead from the entry to the Birkenau concentration camp to the gas chambers. Birkenauwas an extension of the Auschwitz camp in WWII Nazi-occupied Poland. Andrea Pitzer

Y ou mention several times in the book the experience of prisoners entering a different world on arrival at Auschwitz. This is extremely important, and I think that this was maybe the main reason why so many survivors started to speak about Auschwitz so late. And still, 95 percent of survivors didn’t speak, didn’t give testimonials, didn’t write any memoirs. I think that they were afraid that using words from our normal world would never give the sense of the reality of the camp.

When I’m hungry, it doesn’t mean the same as when you are hungry in the camp. It’s completely different, and it’s like this with many other emotions, because they are at an extreme that we can’t imagine in our world. You’re put in a situation when the most important factors, like space and time, are completely different. You don’t know how long you will survive. When you’re speaking about hope, it means some plans for the future, but in the camp it means to survive for the next five or ten minutes. And at every moment, somebody is dying around you. That means you will also die, perhaps in a few minutes or in one hour. It’s a completely different kind of time than we experience in normal life.

At the beginning, I was thinking that I would speak about death at the end of the book. This was an error. In Auschwitz death did not happen at the end; it was present at all times and everywhere.

One of the essays in the collection is on death. There’s a quote from a survivor: “not only is life and human dignity violated here but human death counts for nothing.” For us, death is so tragic. It’s a big mystery. We will arrive all of us at one moment to face our death, but it’s something that we consider with a religious or para-religious approach, with a philosophical approach, even if we if we don’t want to organize our lives according to this destination.

In the camp death was everywhere and could arrive at every moment. Maybe the only thing that they were sure of was death. It’s also completely different when it’s an inverse point to our way of thinking about death. If I ask what you’re sure about in the immediate future, you would tell me about how you will go back home and get dinner or do something with your family. But nobody would be thinking about death as something that we can be sure of happening in the present moment.

One quote from another testimony says: “Among the Auschwitz prisoners who wrote their memoirs none of them claims the camp ennobled people.” Yet it’s woven into a lot of fabric of society before and after Auschwitz that suffering brings a kind of nobility, that there is something inherent in suffering that makes us pure or better. I think it’s important that is not what’s reflected in most of these testimonies. Yes, this perspective is present in very few testimonies. What we consider as a moral system in our society was completely different when it was recreated inside the camp. I think it was also a factor in the incapacity to speak about Auschwitz for many survivors because they begin to justify themselves, and they don’t want to justify themselves. They knew that their choices inside the camp — daily choices, I do not speak about dramatic choices — the daily choices were how to survive, to have one or two or three or days more to stay alive.

The position where you stand at the queue in order to have your soup: If you go at the starting point of the distribution of the soup, you will receive only water; if you go at the end, you’ll be beaten by some very well-positioned prisoners, some kapo or some people from the blocks, because they know that at the end, there will be some potatoes. So you have to find your own position, not too quickly and not too late. But that means you will take this place from some other prisoner. And with every choice you made, that means somebody else did not get this choice.

You also address the Sonderkommando — these people who were drafted into being active participants in the murder of other prisoners at Auschwitz. It’s perhaps the most tragic history in the camp, the story of the Sonderkommando . They were in general young men taken from different transports and put to work around the gas chambers and the crematoria. They had to burn corpses, to make all this machinery function. A clear majority were Jews, and many of them were coming from Jewish Orthodox families, and cremation of course was something they couldn’t have imagined. For decades after the war, they were considered maybe not as perpetrators but as collaborators of perpetrators, except two or three, like Shlomo Venezia or Filip Müller . Many of them stayed silent for years.

We are all very proud of our culture, our education and our sense of values. We feel really prepared to confront difficulties. Those people also, certainly they were thinking like this. But a few days were enough to change a person arriving from a normal world to a person completely acting according to the camp rules, thinking in a different way, approaching other humans in a different way, considering himself as a completely different person.

Another example of a theme that we in our world might think of quite differently than the voices we hear in the book is this idea of sacrifice. I want to speak specifically about Father Kolbe , because many people have heard about this story, and he was canonized later for switching places with a condemned person. Here’s what one of the survivors said about him: “I must stress that what impressed us was not that he gave up his life for someone else, for life wasn’t worth much in the camp. We were impressed that in front of so many SS men and prisoner functionaries, he had broken discipline and dared to step out of rank.” It’s quite different than what we might think. I heard many words like this. “If you give your life for another, that does not mean you give your life. You give your last few days or a few weeks, it’s not something exceptional. But breaking the rules, it is something, yes.”

And there were, of course, different levels of sacrifice. You can share, for example, your bread. So you have some bread. Your kid or your friend for some reason has no more bread, and maybe he’s in deeper need. You can give him the half of your bread; it seems nothing. But what was the remark of the prisoners? “Oh, look at him he’s starting to share his bread. He has no will to survive. He will be finished very quickly.” It’s not like a sacrifice, it’s like suicide. This is why I am speaking about an entire axiology that is completely different in the camp than in our perception.

A prisoners' room at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Auschwitz memorial, Poland.

You note that some of those people wo were most deeply tied into their communities actually were a tremendous disadvantage in the camp. Those who had the easiest time adapting to the camp were people coming from very low socioeconomic levels from big cities, people who had very hard childhoods with many problems in their lives. They’ve got ideas on how to adapt to those difficulties.

But at the opposite end, you get for example people from the countryside, normal people without any education, unable to understand or to speak German, unable to imagine a different world than their own, living all the time in cyclical time according to the seasons. They found themselves in the camp and were completely unable to adapt. In general they did not leave testimonies after the war, because if you finish two grades in the schools or even not two, you are unable to write your testimony.

But many other prisoners themselves tried to enter in contact with them and describe them, and this was something incredible. Many times you think it’s those people coming from very traditional settings with centuries of culture and systems of ethics who will be the strongest in a difficult time. Not really. Not really.

One of the things the general public forgets today about the enormity of the death camps and the Holocaust was that it took many years to frame even the basic understanding that we have today of what happened. It was not understood in the immediate postwar time, so survivors didn’t have that space to speak, because what they experienced was in some ways quite different than what was first said about what had happened in the camps. The situation of somebody captured in 1940 in Warsaw because he prepared some anti-Nazi, anti-German action, as a scout or something like this, was completely different than somebody who was taken from their house for nothing. The latter was unable to know why he was in this camp. It was difficult to create a definite narrative after the war if you were taken for no reason from your house or from the street and sent to the camp. If somebody was involved in some unusual actions, it was different. He was able afterward to say, “Yes I suffered a lot. It was inhuman, but I was fighting against something.”

This psychological difference was huge in the postwar narratives.

A question from the audience, from a woman whose father spent years in Auschwitz, asks about the difference between the reception of Christian and Jewish narratives. In Poland, especially after 1968, the camp narrative was more organized by Christian prisoners. In the Western world it was more organized by Jewish survivors. It was a very clear difference between the two narratives.

I remember in the ’90s when Communism ended, it became possible to travel to Poland to visit Auschwitz. The two communities of remembrance met in the same place and did not recognize each other. It was like they were speaking about some completely different history. There were different symbols, words, approaches. It created tensions, it created emotions.

It took time, even a whole generation — up until 2010 or later — for those different worlds not only to accept each other but to understand that, yes, they’re all attached to the same story, to the same place. It was very, very difficult.

And at the same time, in the late ’90s, some new history arrived. The genocide of the Roma and Sinti — so-called gypsies — was discovered by the larger public. Then Russia started to speak about the Soviet prisoners of war who were put in Auschwitz.

I think we are headed in a good direction. We are learning to understand each other and all these stories.

Andrea Pitzer is the author of three books of narrative nonfiction that explore untold histories. She was the editor of Nieman Storyboard from 2009-2012.

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Survivors, Victims, and Perpetrators: Essays on the Nazi Holocaust

University of Illinois Medical Center Chicago

This article is only available in the PDF format. Download the PDF to view the article, as well as its associated figures and tables.

This book delineates the social setting and the process of organizing the extermination of millions according to National Socialist philosophy. As Hamburg notes in his foreword, the "level of sophistication in modern organization and technology" that the Germans brought to this work was unique—railway schedules, euphemisms for murder, classifications of Gypsies, Jews, Poles, and political prisoners, the architectural design and chemistry of mass murder. Also detailed are the use of inmates as cards for political negotiation and the resistance of some Italian Fascists and German clergymen.

There is a section on the victims, telling how survivors coped in the camps and afterwards, and about the psychotherapy of survivors and what happens to their children. A general model of stress and coping under extreme conditions is developed by Benner, Roskies, and Lazarus.

A final section deals with the perpetrators. There are diaries and autobiographical material from guards and prominent Nazis, as

Bernstein NR. Survivors, Victims, and Perpetrators: Essays on the Nazi Holocaust. JAMA. 1982;247(22):3138. doi:10.1001/jama.1982.03320470078043

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Articles on Holocaust survivors

Displaying all articles.

Gabor Maté claims trauma contributes to everything: from cancer to ADHD. But what does the evidence say?

Nick Haslam , The University of Melbourne

For Australian Jews in the 1940s and 1950s, remembering the Holocaust meant fighting racism and colonialism

Max Kaiser , The University of Melbourne

By policing history, Poland’s government is distorting the Holocaust

Jan Grabowski , L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Holocaust survivor stories are reminders of why we need to educate against antisemitism

Carson Phillips , Gratz College

A brief history of Babi Yar, where Nazis massacred Jews, Soviets kept silence and now Ukraine says Russia fired a missile

Jeffrey Veidlinger , University of Michigan

LGBT+ history: The Amazing Life of Margot Heuman – how theatre gave voice to a queer Holocaust survivor

Erika Hughes , University of Portsmouth and Anna Hájková , University of Warwick

Canadian writing about the Holocaust is haunted by the grim past

Ruth Panofsky , Toronto Metropolitan University

5 websites to help educate about the horrors of the Holocaust

Jennifer Rich , Rowan University

How to fight Holocaust denial in social media – with the evidence of what really happened

Adam G. Klein , Pace University

Nazis murdered a quarter of Europe’s Roma, but history still overlooks this genocide

Barbara Warnock , University of Cambridge

How will generations that didn’t experience the Holocaust remember it?

Timothy Langille , Arizona State University

From the St Louis to the Aquarius: the history of refugee boats as archipelagos of misery

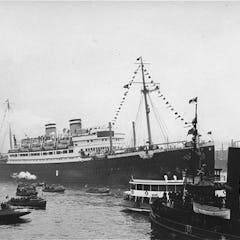

Simone Gigliotti , Royal Holloway University of London

Why we need to rethink how to teach the Holocaust

Alan Marcus , University of Connecticut

Why remembering matters for healing

Nancy Berns , Drake University

Poland is trying to rewrite history with this controversial new holocaust law

Svenja Bethke , University of Leicester

What Trump’s every-country - for-itself rhetoric gets wrong about Davos

Stephen D. Smith , USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Why we still need to teach young people about the Holocaust

Michael Richards , Edge Hill University ; Anna Bussu , Edge Hill University , and Peter Leadbetter , Edge Hill University

Could there be a link between genocide and suicide?

Colin Tatz , Australian National University

The story of an Englishman in Auschwitz

Andy Pearce , UCL and Ruth-Anne Lenga , UCL

Why it’s hard to ‘just get over it’ for people who have been traumatized

Joan M. Cook , Yale University

Related Topics

- Holocaust education

- Holocaust Memorial Day

- Holocaust museum

- International Holocaust Remembrance Day

Top contributors

ANU Visiting Professor, Politics and International Relations, Australian National University

Professor of Sociology, Drake University

Associate Professor of Modern Continental European History, University of Warwick

Professor, Yale University

Associate Professor of Communication Studies, Pace University

Senior Lecturer in Applied Health and Social Care, Edge Hill University

Associate Professor in Holocaust and History Education, UCL

Head of Academic Programmes, UCL

Senior Lecturer in Applied Health & Social Care, Edge Hill University

Lecturer in the Psychosocial Analysis of Offending Behaviour, Faculty of Health and Social Care, Edge Hill University

Director of Shoah Foundation, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Lecturer in Modern European History, University of Leicester

Professor of Curriculum & Instruction, University of Connecticut

Senior Lecturer / Reader in Holocaust Studies, Royal Holloway University of London

Associate Professor of Sociology, Rowan University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Holocaust

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 11, 2023 | Original: October 14, 2009

The Holocaust was the state-sponsored persecution and mass murder of millions of European Jews, Romani people, the intellectually disabled, political dissidents and homosexuals by the German Nazi regime between 1933 and 1945. The word “holocaust,” from the Greek words “holos” (whole) and “kaustos” (burned), was historically used to describe a sacrificial offering burned on an altar.

After years of Nazi rule in Germany, dictator Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution”—now known as the Holocaust—came to fruition during World War II, with mass killing centers in concentration camps. About six million Jews and some five million others, targeted for racial, political, ideological and behavioral reasons, died in the Holocaust—more than one million of those who perished were children.

Historical Anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism in Europe did not begin with Adolf Hitler . Though use of the term itself dates only to the 1870s, there is evidence of hostility toward Jews long before the Holocaust—even as far back as the ancient world, when Roman authorities destroyed the Jewish temple in Jerusalem and forced Jews to leave Palestine .

The Enlightenment , during the 17th and 18th centuries, emphasized religious tolerance, and in the 19th century Napoleon Bonaparte and other European rulers enacted legislation that ended long-standing restrictions on Jews. Anti-Semitic feeling endured, however, in many cases taking on a racial character rather than a religious one.

Did you know? Even in the early 21st century, the legacy of the Holocaust endures. Swiss government and banking institutions have in recent years acknowledged their complicity with the Nazis and established funds to aid Holocaust survivors and other victims of human rights abuses, genocide or other catastrophes.

Hitler's Rise to Power

The roots of Adolf Hitler’s particularly virulent brand of anti-Semitism are unclear. Born in Austria in 1889, he served in the German army during World War I . Like many anti-Semites in Germany, he blamed the Jews for the country’s defeat in 1918.

Soon after World War I ended, Hitler joined the National German Workers’ Party, which became the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), known to English speakers as the Nazis. While imprisoned for treason for his role in the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, Hitler wrote the memoir and propaganda tract “ Mein Kampf ” (or “my struggle”), in which he predicted a general European war that would result in “the extermination of the Jewish race in Germany.”

Hitler was obsessed with the idea of the superiority of the “pure” German race, which he called “Aryan,” and with the need for “Lebensraum,” or living space, for that race to expand. In the decade after he was released from prison, Hitler took advantage of the weakness of his rivals to enhance his party’s status and rise from obscurity to power.

On January 30, 1933, he was named chancellor of Germany. After the death of President Paul von Hindenburg in 1934, Hitler anointed himself Fuhrer , becoming Germany’s supreme ruler.

Concentration Camps

The twin goals of racial purity and territorial expansion were the core of Hitler’s worldview, and from 1933 onward they would combine to form the driving force behind his foreign and domestic policy.

At first, the Nazis reserved their harshest persecution for political opponents such as Communists or Social Democrats. The first official concentration camp opened at Dachau (near Munich) in March 1933, and many of the first prisoners sent there were Communists.

Like the network of concentration camps that followed, becoming the killing grounds of the Holocaust, Dachau was under the control of Heinrich Himmler , head of the elite Nazi guard, the Schutzstaffel (SS) and later chief of the German police.

By July 1933, German concentration camps ( Konzentrationslager in German, or KZ) held some 27,000 people in “protective custody.” Huge Nazi rallies and symbolic acts such as the public burning of books by Jews, Communists, liberals and foreigners helped drive home the desired message of party strength and unity.

In 1933, Jews in Germany numbered around 525,000—just one percent of the total German population. During the next six years, Nazis undertook an “Aryanization” of Germany, dismissing non-Aryans from civil service, liquidating Jewish-owned businesses and stripping Jewish lawyers and doctors of their clients.

Nuremberg Laws

Under the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was considered a Jew, while those with two Jewish grandparents were designated Mischlinge (half-breeds).

Under the Nuremberg Laws, Jews became routine targets for stigmatization and persecution. This culminated in Kristallnacht , or the “Night of Broken Glass” in November 1938, when German synagogues were burned and windows in Jewish home and shops were smashed; some 100 Jews were killed and thousands more arrested.

From 1933 to 1939, hundreds of thousands of Jews who were able to leave Germany did, while those who remained lived in a constant state of uncertainty and fear.

HISTORY Vault: Third Reich: The Rise

Rare and never-before-seen amateur films offer a unique perspective on the rise of Nazi Germany from Germans who experienced it. How were millions of people so vulnerable to fascism?

Euthanasia Program

In September 1939, Germany invaded the western half of Poland , starting World War II . German police soon forced tens of thousands of Polish Jews from their homes and into ghettoes, giving their confiscated properties to ethnic Germans (non-Jews outside Germany who identified as German), Germans from the Reich or Polish gentiles.

Surrounded by high walls and barbed wire, the Jewish ghettoes in Poland functioned like captive city-states, governed by Jewish Councils. In addition to widespread unemployment, poverty and hunger, overpopulation and poor sanitation made the ghettoes breeding grounds for disease such as typhus.

Meanwhile, beginning in the fall of 1939, Nazi officials selected around 70,000 Germans institutionalized for mental illness or physical disabilities to be gassed to death in the so-called Euthanasia Program.

After prominent German religious leaders protested, Hitler put an end to the program in August 1941, though killings of the disabled continued in secrecy, and by 1945 some 275,000 people deemed handicapped from all over Europe had been killed. In hindsight, it seems clear that the Euthanasia Program functioned as a pilot for the Holocaust.

'Final Solution'

Throughout the spring and summer of 1940, the German army expanded Hitler’s empire in Europe, conquering Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France. Beginning in 1941, Jews from all over the continent, as well as hundreds of thousands of European Romani people, were transported to Polish ghettoes.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 marked a new level of brutality in warfare. Mobile killing units of Himmler’s SS called Einsatzgruppen would murder more than 500,000 Soviet Jews and others (usually by shooting) over the course of the German occupation.

A memorandum dated July 31, 1941, from Hitler’s top commander Hermann Goering to Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the SD (the security service of the SS), referred to the need for an Endlösung ( Final Solution ) to “the Jewish question.”

Yellow Stars

Beginning in September 1941, every person designated as a Jew in German-held territory was marked with a yellow, six-pointed star, making them open targets. Tens of thousands were soon being deported to the Polish ghettoes and German-occupied cities in the USSR.

Since June 1941, experiments with mass killing methods had been ongoing at the concentration camp of Auschwitz , near Krakow, Poland. That August, 500 officials gassed 500 Soviet POWs to death with the pesticide Zyklon-B. The SS soon placed a huge order for the gas with a German pest-control firm, an ominous indicator of the coming Holocaust.

Holocaust Death Camps

Beginning in late 1941, the Germans began mass transports from the ghettoes in Poland to the concentration camps, starting with those people viewed as the least useful: the sick, old and weak and the very young.

The first mass gassings began at the camp of Belzec, near Lublin, on March 17, 1942. Five more mass killing centers were built at camps in occupied Poland, including Chelmno, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek and the largest of all, Auschwitz.

From 1942 to 1945, Jews were deported to the camps from all over Europe, including German-controlled territory as well as those countries allied with Germany. The heaviest deportations took place during the summer and fall of 1942, when more than 300,000 people were deported from the Warsaw ghetto alone.

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

Amid the deportations, disease and constant hunger, incarcerated people in the Warsaw Ghetto rose up in armed revolt.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from April 19-May 16, 1943, ended in the death of 7,000 Jews, with 50,000 survivors sent to extermination camps. But the resistance fighters had held off the Nazis for almost a month, and their revolt inspired revolts at camps and ghettos across German-occupied Europe.

Though the Nazis tried to keep operation of the camps secret, the scale of the killing made this virtually impossible. Eyewitnesses brought reports of Nazi atrocities in Poland to the Allied governments, who were harshly criticized after the war for their failure to respond, or to publicize news of the mass slaughter.

This lack of action was likely mostly due to the Allied focus on winning the war at hand, but was also partly a result of the general incomprehension with which news of the Holocaust was met and the denial and disbelief that such atrocities could be occurring on such a scale.

'Angel of Death'

At Auschwitz alone, more than 2 million people were murdered in a process resembling a large-scale industrial operation. A large population of Jewish and non-Jewish inmates worked in the labor camp there; though only Jews were gassed, thousands of others died of starvation or disease.

In 1943, eugenics advocate Josef Mengele arrived in Auschwitz to begin his infamous experiments on Jewish prisoners. His special area of focus was conducting medical experiments on twins , injecting them with everything from petrol to chloroform under the guise of giving them medical treatment. His actions earned him the nickname “the Angel of Death.”

Nazi Rule Ends

By the spring of 1945, German leadership was dissolving amid internal dissent, with Goering and Himmler both seeking to distance themselves from Hitler and take power.

In his last will and political testament, dictated in a German bunker that April 29, Hitler blamed the war on “International Jewry and its helpers” and urged the German leaders and people to follow “the strict observance of the racial laws and with merciless resistance against the universal poisoners of all peoples”—the Jews.

The following day, Hitler died by suicide . Germany’s formal surrender in World War II came barely a week later, on May 8, 1945.

German forces had begun evacuating many of the death camps in the fall of 1944, sending inmates under guard to march further from the advancing enemy’s front line. These so-called “death marches” continued all the way up to the German surrender, resulting in the deaths of some 250,000 to 375,000 people.

In his classic book Survival in Auschwitz , the Italian-Jewish author Primo Levi described his own state of mind, as well as that of his fellow inmates in Auschwitz on the day before Soviet troops liberated the camp in January 1945: “We lay in a world of death and phantoms. The last trace of civilization had vanished around and inside us. The work of bestial degradation, begun by the victorious Germans, had been carried to conclusion by the Germans in defeat.”

Legacy of the Holocaust

The wounds of the Holocaust—known in Hebrew as “Shoah,” or catastrophe—were slow to heal. Survivors of the camps found it nearly impossible to return home, as in many cases they had lost their entire family and been denounced by their non-Jewish neighbors. As a result, the late 1940s saw an unprecedented number of refugees, POWs and other displaced populations moving across Europe.

In an effort to punish the villains of the Holocaust, the Allies held the Nuremberg Trials of 1945-46, which brought Nazi atrocities to horrifying light. Increasing pressure on the Allied powers to create a homeland for Jewish survivors of the Holocaust would lead to a mandate for the creation of Israel in 1948.

Over the decades that followed, ordinary Germans struggled with the Holocaust’s bitter legacy, as survivors and the families of victims sought restitution of wealth and property confiscated during the Nazi years.

Beginning in 1953, the German government made payments to individual Jews and to the Jewish people as a way of acknowledging the German people’s responsibility for the crimes committed in their name.

The Holocaust. The National WWII Museum . What Was The Holocaust? Imperial War Museums . Introduction to the Holocaust. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum . Holocaust Remembrance. Council of Europe . Outreach Programme on the Holocaust. United Nations .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Auschwitz Photos

- Birkenau Photos

- Mauthausen Photos

- Then and Now

- Paintings by Jan Komski – Survivor

- Geoffrey Laurence Paintings

- Paintings by Tamara Deuel – Survivor

- David Aronson Images

- Haunting Memory

- Holocaust Picture Book – The Story of Granny Girl as a Child

- Birkenau and Mauthausen Photos

- Student Art

- Photos – Late 1930s

- Holocaust Photos

- Lest We Forget

- Carapati – a Film

- Warsaw Ghetto Photos

- Nordhausen Liberation

- Dachau Liberation

- Ohrdruf Liberation

- Gunskirchen Lager Pamphlet

- Buchenwald Liberation

- Chuck Ferree

- Lt. Col. Felix Sparks

- Debate the Holocaust?

- Books by Survivors

- Children of Survivors

- Adolf Eichmann – PBS

- Adolf Hitler’s Plan

- Himmler Speech

- Goebbels Diaries

- Letter on Sterilization

- Letters on Euthanasia

- Nazi Letters on Executions

- Page of Glory

- Homosexuals

- Gypsies in Auschwitz I

- Gypsies in Auschwitz 2

- Babi Yar Poem

- Polish Citizens and Jews

- Harold Gordon

- Sidney Iwens

- I Cannot Forget

- Keep Yelling! A Survivor’s Testimony

- A Survivor’s Prayer

- In August of 1942

- Jacque Lipetz

- Walter Frank

- Helen Lazar

- Lucille Eichengreen

- Judith Jagermann

- Filip Muller

- Holocaust Study Guide

- Holocaust Books A-Z

- Anne Frank Biography | 1998 Holocaust Book

- Help Finding People Lost in the Holocaust Search and Unite

- Holocaust history and stories from Holocaust Photos, Survivors, Liberators, Books and Art

- Remember.org Origins

Return to Women Writing the Holocaust

Joan Miriam Ringelheim asks, “Did anyone really survive the Holocaust?” It is a question more difficult to answer than it might at first appear. The Holocaust breaks down the definitions of words such as “survival.” Memoirist Charlotte Delbo wrote after the war’s end, “I died in Auschwitz, but no one knows it.” And as idealistic as it may sound, there is some truth to the notion that Anne Frank and Charlotte Salomon manage, despite their brutal and meaningless murders, to live on after death. They wrote, after all, with that possibility in mind.

If to survive means to come through unscathed, the answer to Ringelheim’s question must be no. But if to survive means to live through an experience of such horror still be able to desire connection with the world–to create, narrate, innovate, to invoke the voices of the dead and of the living–then the answer is yes. To survive: “sur”–over, “vive”–live; the verb implies both to surmount an event, to live through it, and to relive it, live it over. Perhaps the simplest and somewhat tragic truth is that the one necessarily involves the other.

I find some sense of closure in Felstiner’s loving exploration of Charlotte Salomon because it is one which treats both the creator and the creation with equal care. What distinguishes Lucille E. from Anne Frank and Charlotte Salomon, of course, is that only the first survived the Holocaust. Yet all three have created voices which seek to bear witness to the Shoah, if only the world will let them. The skill which it would benefit the world to develop is that of simultaneously recognizing the fundamental point that memoirs of female Holocaust witnesses are authored by women, and that they each nevertheless are not utterly circumscribed by that fact. To neglect the first point contributes to an artificial universalization of men’s experience and a silencing of painful but important questions. To neglect the second points to essentialism and dogmatic discourse. These women have taken a great step in creating a stand-in, a memorial protagonist, which can continue to tell their story after their own ends. They have invested the memoir with a certain autonomy; that autonomy needs to be acknowledged by the rest of us.

Go to the Top of the Page || Return to Women Writing the Holocaust

Remember. Zachor. Sich erinnern.

Remember.org helps people find the best digital resources, connecting them through a collaborative learning structure since 1994. If you'd like to share your story on Remember.org, all we ask is that you give permission to students and teachers to use the materials in a non-commercial setting. Founded April 25, 1995 as a "Cybrary of the Holocaust". Content created by Community. THANKS FOR THE SUPPORT . History Channel ABC PBS CNET One World Live New York Times Apple Adobe Copyright 1995-2024 Remember.org. All Rights Reserved. Publisher: Dunn Simply

APA Citation

Dunn, M. D. (Ed.). (95, April 25). Remember.org - The Holocaust History - A People's and Survivors' History. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from remember.org

MLA Citation

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Neurobiol Stress

- v.14; 2021 May

Lifelong impact of extreme stress on the human brain: Holocaust survivors study

Monika fňašková.

a Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC), Brain and Mind Research Program, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

c First Department of Neurology, St. Anne's Hospital and School of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

Pavel Říha

Marek preiss.

d University of New York in Prague, Czech Republic

Markéta Nečasová

Eva koriťáková.

b Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses, Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

Ivan Rektor

Associated data.

All data are available upon request at the Repository CEITEC Masaryk University, MAFIL CF.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

We aimed to assess the lifelong impact of extreme stress on people who survived the Holocaust. We hypothesised that the impact of extreme trauma is detectable even after more than 70 years of an often complicated and stressful post-war life.

Psychological testing was performed on 44 Holocaust survivors (HS; median age 81.5 years; 29 women; 26 HS were under the age of 12 years in 1945) and 31 control participants without a personal or family history of the Holocaust (control group (CG); median 80 years; 17 women). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using the 3T Siemens Prisma scanner was performed on 29 HS (median 79 years; 18 women) and 21 CG participants (median 80 years; 11 women). The MRI-tested subgroup that had been younger than 12 years old in 1945 was composed of 20 HS (median 79 years; 17 women) and 21 CG (median 80 years; 11 women).

HS experienced significantly higher frequency of depression symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and posttraumatic growth, and lower levels of well-being. The MRI shows a lifelong neurobiological effect of extreme stress. The areas with reduced grey matter correspond to the map of the impact of stress on the brain structure: insula, anterior cingulate, ventromedial cortex including the subgenual cingulate/orbitofrontal cortex, temporal pole, prefrontal cortex, and angular gyrus. HS showed good adjustment to post-war life conditions.

Psychological growth may contribute to compensation for the psychological and neurobiological consequences of extreme stress.

The reduction of GM was significantly expressed also in the subgroup of participants who survived the Holocaust during their childhood.

The lifelong psychological and neurobiological changes in people who survived extreme stress were identified more than 70 years after the Holocaust. Extreme stress in childhood and young adulthood has an irreversible lifelong impact on the brain.

1. Introduction

The Holocaust was the most traumatic man-made event in European history. In the former Czechoslovakia, the entire Jewish population suffered from this large-scale genocide, which lasted from 1938 to 1945. It started with social and professional exclusion, humiliation, and suppression of basic rights, followed by deportation to concentration camps, forced labour, and exposure to horrific atrocities, or by illegally hiding or joining partisan groups under constant threat of discovery and execution. All of the holocaust survivors (HS), independently of their age, experienced massive trauma and the post-war shock of having lost family members, including parents, children, and siblings, and the necessity of adjusting to new and difficult life circumstances.

The first studies of the effect of this extreme stress on the health of the HS noted the mental impact but focused on physical health ( Helweg-Larsen et al., 1952 ). The term ‘concentration camp syndrome’ for symptoms including emotional instability, poor concentration, and fatigue was introduced in the 1960s ( Eitinger, 1962 ).

Levav and Abramson ( Levav and Abramson, 1984 ) showed that 30 years after the war emotional distress had a higher prevalence in the former concentration camp inmates than in other European-born members of the community. Barel et al. performed a meta-analysis of 71 studies with 12,746 participants elucidating the long-term psychiatric, psychosocial, and physical consequences of the Holocaust. They found higher-level posttraumatic stress symptoms in HS but also adaptation (cognitive function, physical health, etc.) combining psychological growth with defense mechanisms ( Barel et al., 2010 ). They marked this combination of chronic stress symptoms and resilience as ‘characteristics of the symptoms of Holocaust survivors’.

Traumatic stress is manifested by changes in brain structure. The hippocampus, amygdala, cingulate, prefrontal cortex ( Arnsten et al., 2015 ; Bremner, 2003 ), and insular cortex ( Paulus and Stein, 2006 ) are often mentioned as structures that are vulnerable to the effects of stress ( Ansell et al., 2012 ; Bruce et al., 2013 ; Cohen et al., 2006 ; Kasai et al., 2008 ; Kuo et al., 2012 ; Lupien and Lepage, 2001 ; McEwen et al., 2016 ; McEwen and Morrison, 2013 ; Paulus and Stein, 2006 ; Roozendaal et al., 2009 ; Yaribeygi et al., 2017 ). Neurobiological modifications caused by stress can be linked with the development of diseases like depression ( Bremner et al., 2000 ) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ( Bremner et al., 1995 ; Logue et al., 2018 ; Villarreal et al., 2002 ). Increased vulnerability to PTSD was observed in Holocaust survivors ( Yehuda et al., 1998 ). In this study, we explored the lifelong impact of stress on brain structure using structural MRI.

The timing of stress exposure is a critical factor for the impacts of stress on brain structure and functions. A younger age during the traumatic period is linked to greater damage to personality development ( Keilson and Sarphatie, 1992 ). During development (prenatal period, childhood, adolescence) and age-dependent changes (ageing), the brain is more vulnerable to the effects of stress hormones ( Lupien et al., 2009 ). Childhood adversities are typically associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and early childhood trauma can cause long lasting neurobiological and psychological deficiencies ( Dye, 2018 ).

To explore the impact of stress during development, we investigated a subgroup of HS who were under 12 years old at the end of the war in 1945. Dividing the research set at the age of 12 makes sense from a developmental point of view; according to Erikson and Erikson, the fourth stage of human life ends at the age of 12. This is the last stage before adolescence ( Erikson and Erikson, 1998 ).

The goal of this study is to assess the lifelong psychological and neurobiological impact of long-lasting extreme stress. The combination of psychological testing with brain MRI more than 70 years after the war provides unique data about the impact of extreme trauma.

Given the ages of survivors, this data probably reflects the last chance to explore the lifelong impact of this extreme trauma and directly learn from the survivors about their evaluations of a life marked by extreme stress. Data from the genetic part of this study have been partially published, including results about telomere length and mitochondrial DNA ( Cai et al., 2020 ; Konečná et al., 2019 ).

The study is based on two hypotheses: 1. We hypothesised that Holocaust survivors have had a lifelong impact on stress-related brain areas combined with psychological consequences of stress as well as signs of posttraumatic growth, identifiable despite the complicated and often stressful life in Central Europe after the war.

2. We hypothesised that the lifelong consequences of extreme stress trauma would also be expressed in people who survived the Holocaust as children, despite the fact that children have a limited ability to cognitively process life-threatening situations ( Sigal and Weinfeld, 2001 ) and the children were not exposed to direct threats of being killed, as most of them survived the Holocaust hidden in other families or institutions.

2.1. Participants and recruitment

2.1.1. research and recruitment.

The study was conducted at the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC) Neuroscience Centre, at Masaryk University in Brno between 2015 and 2020. Part of the data was obtained at the National Institute of Mental Health (NÚDZ) in Klecany. The data were obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The research was approved by the ethics committee at Masaryk University; informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All of the participants were of Czech or Slovak origin, i.e. people with a similar geopolitical background. The two countries formed one state – Czechoslovakia – until 1993, and the close connections between the citizens continue; the Czech and Slovak languages are mutually comprehensible.

The participants were recruited through the cooperation of local Jewish communities (the Holocaust survivors group), announcements in the media, and postings on the university website. For HS and CG recruitment, we also used personal invitations from members of the research team and the snowball sampling method. The CG was completed when the composition of HS was already clear and the CG could be matched with HS.

2.1.2. Participants characteristics

Exclusion criteria: a history of treatment for severe psychiatric disorders (such as psychosis), any kind of severe brain impairment (brain injury, tumours, neurodegenerative diseases), and significant cognitive decline (all participants scored over 26 points in the Mini-Mental State Examination) ( Solomon et al., 1998 ). Contraindications for MRI were metal implants, pacemakers, and claustrophobia.

The HS and CG groups were not significantly different in age, sex, and education; this was verified using Mann-Whitney U test. The groups were 44 HS with median age 82 (71–95) years, 29 women (66%) and 31 Czech and Slovak non-Jewish control participants not exposed to war-related trauma with median age 80 (73–90) years, 17 women (55%). Higher education had been attained by 46% of HS and 36% of CG.

The subgroup under 12 years old in 1945 was composed of 26 HS with median age 78.5 (71–84) years, 17 women (65%) and 24 control participants with median age 78 (73–84), 12 women (50%). Table with demographic group characteristics is in the supplementary material.

Participants who could not participate in MR scanning because of contraindications or who underwent MR scanning with insufficiently quality scans were excluded from the final brain images analysis.

The neuroimaging cohort was composed of 29 HS with median age 79 (72–95), 18 women (62%), and 21 control participants median age 80 (73–86), 11 women (52%). Their psychological profile resembled the profile of the whole cohort ( Table 2 ).

Psychological questionnaires: differences between Holocaust survivors (HS) and the control group (CG).

TSC: Trauma Symptom Checklist; PCLC – C: PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version; PTGI: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory; SOS – Schwartz Outcome Scale.

The neuroimaging subgroup under 12 years old in 1945 was composed of 20 HS with median age 78 (72–84), 12 women (60%), and 21 control participants median age 80 (73–86), 11 women (52%).

No gender-associated effects were found using a two-sample t -test comparing male and female data.

2.1.3. Background of examined groups

2.1.3.1. holocaust survivors group characteristics.

During the Holocaust, 24 HS were in hiding, e.g. living with a non-Jewish family in a small village, in a farmhouse, in an evangelist orphanage, or in a secret room, in their childhood or adolescence. Five HS lived under a false identity or were hiding in the mountains; some of them joined the partisan army.

Fifteen HS were imprisoned in a ghetto (most often Terezín - Theresienstadt) and/or in concentration camps (Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, or Mauthausen). Several participants had survived a death march. The persecution increased over six years; the immediate danger of execution, whether after being discovered for people who were hiding or after being imprisoned in a concentration camp, lasted from six months to four years.

Most of them experienced trauma at critical developmental phases; 26 HS were aged under 12 years by the end of the war in 1945. Nineteen of them were in hiding (nine with their parents and ten without them). Seven were imprisoned in the ghetto Theresienstadt.

2.1.3.2. Control group characteristics

The Czech Republic was occupied by Nazi Germany as the Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren. There was a strong oppression of the Czech population, but its majority was not directly exposed to the war events. Participants in CG were civilians and did not participate in military action or resistance; during the war, they were not under direct life-threatening danger.

Post-war life conditions under the communist regime from 1948 to 1989 were difficult and differed from the conditions in Western democracies. The regime was oppressive and often anti-Semitic, in particular in the 1950s, with a series of political processes followed by executions and long-term imprisonments. Jews experienced direct oppression, as did other groups, e.g. private farmers and entrepreneurs, Christians, intellectuals, etc. After a liberalisation period in the 1960s, ended by the Soviet army intervention in 1968, a general suppression of human rights followed for 20 years. Based on individual interviews, we can state that none of our study participants advanced their career based on membership in the Communist Party. In principle, the HS and CG suffered from the communist oppression in a more or less similar way.

2.2. Initial screening

For the initial screening, all participants were tested with the 7-min screen test ( Solomon et al., 1998 ).

The protocol consisted of interviews, psychological questionnaires, and MR scanning. In addition, participants completed the Geriatric Depression Scale test as a part of the initial screening (participants with major depression were not included in the study).

2.3. Interview

All participants, HS and CG, were asked about their life before, during, and after the war. HS were also asked how they survived the Holocaust and how long they were persecuted. In the self-report part, the HS answered a short questionnaire focused on the self-evaluation of their personal life and professional career as affected by the Holocaust.

2.4. Psychological measures

Four questionnaires testing the hypothesis of the lifelong impact of extreme stress were chosen for this study. Two tests explored the negative impact of stress, specifically posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and actual stress symptoms (PCL-C and TSC-40 respectively); one test explored the positive impact of stress (PTGI); and one test explored the subjective appreciation of actual quality of life (SOS-10).

All psychological questionnaires are summarised in detail in Table 1 .

Psychological tests.

2.4.1. Statistical analysis

The results of the psychological questionnaires were summarised using median, minimum, and maximum. For statistical testing of differences between HS and GC, a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used. The significance level for all statistical tests was set to p < 0.05. The statistical analyses were performed using STATISTICA 12. The effect of age was tested by multiple regression.

2.5. MR imaging

2.5.1. data acquisition.

MR examinations were performed on a 3T scanner Siemens Prisma using a 64-channel head coil. The MRI protocol for voxel-based morphometry included 3D T1-weighted magnetisation prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence with TR = 2.3 s, TE = 2.33 ms, TI = 0.9 s, FA = 8°, isometric voxel size 1 mm in FOV 224 × 224 mm and 240 slices.

Part of the data was obtained at a partner workplace, NÚDZ Klecany, with the same type of 3T Prisma scanner, multichannel coil, and protocol sequence.

Data from all participants were manually checked for artifacts and pathology was checked by an experienced radiologist. Participants who did not meet our quality criteria (scans without technical artifacts or lower SNR; scans without significant movement artifacts; participants with brain pathology; and scans without successfully finished segmentation and normalization into MNI space) were excluded from the study.

2.5.2. Data processing

Anatomical MRI data were analysed using SPM12 ( www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk ) and CAT12 toolbox ( www.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat ) running in Matlab R2017b.

Individual data were adjusted for spatial inhomogeneity with an intensity normalization filter and then denoised with the Non-Local Means (SANLM) denoising filter. High resolution data were then segmented into grey matter using the SPM Tissue Probability Map (TPM) and registered into common MNI space using shooting template IXI555_MNI152_GS. Finally, spatially normalised and modulated GM maps were smoothed with 6 mm FWHM isotropic Gaussian kernel.

2.5.3. Statistical analysis

Group statistics for stress effects were calculated with a second-level model using SPM12. The modulated GM images were multiplicatively corrected with total intracranial volume and then analysed. A two-sample t -test comparison of GMV files between stress group (respectively stress subgroup under 12 years of age) and the control group was performed; sex, age, and MRI machine were included as nuisance variables.

Resultant t-statistic maps were initially thresholded at a P value of <0.005 uncorrected and then only significant clusters at P < 0.05 FWE cluster level were picked.

2.5.4. Grey matter volume and PTSD checklist scale correlation

Based on the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas ( Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002 ), we selected the mean GM volume in an area consisting of the ACC, OFC, and insula, which are constantly repeated stress areas in the literature ( Ansell et al., 2012 ; Bolsinger et al., 2018 ; Kasai et al., 2008 ). These GM volumes and PCL-C values were correlated using Pearson correlation in HS to examine the relationship between brain morphology and posttraumatic stress manifestation.

3.1. Interview

In the interviews with the Holocaust survivors, respondents from the focal group typically cited war events (e.g. death of parents, war as a whole, hiding during the war, transport to and stay in a concentration camp, loss of a loved one), as well as topics related to communism (e.g. secret police interrogations, anti-Semitism) and health problems (e.g. ventricular fibrillation, partial disability, accident, illness) as dominant life events. The control group was typically dominated by lifetime losses (e.g. parents, spouse) and health problems (e.g. heart attack, broken arm).

3.1.1. Self-report

All HS participants were asked how they evaluate their current life in relation to the Holocaust. The questions were as follows: 1. Was the Holocaust the worst experience of your life? (84.1% answered yes or rather yes); 2. Did the Holocaust have a lifelong negative influence on your life? (70.5% answered yes or rather yes); 3. Are you satisfied with your personal life (lifelong view)? (79.6% answered yes or rather yes); 4. Are you satisfied with your career (lifelong view)? (86.4% answered yes or rather yes).

3.2. Psychological measures

3.2.1. depression symptoms.

Depression symptoms were screened using the GDS. The prevalence of depression symptoms was significantly higher in HS (p < 0.001): depression symptoms were experienced by 15 HS (34.1%) and by 3 participants of CG (9.7%).

3.2.2. Psychological testing

The results of the psychological testing ( Table 2 ) significantly differed between HS and CG in all questionnaires. PCL-C showed higher rates of lasting symptoms of chronic stress in HS (in 21; 47.7%) than in CG (2; 6.5%). PTGI presents a higher rate of posttraumatic growth in HS, in 31 (70.5%), than in CG, in 11 (35.5%). SOS-10 displays a lower rate of well-being in HS, who could be classified as ‘maladjusted’ (9; 20.5%) than in CG (3; 9.7%). The effect of age was not statistically significant when used as covariate.

The results of the psychological testing in a subgroup of participants who were under the age of 12 in 1945 ( Table 3 ) significantly differed between HS and CG in all questionnaires. PCL-C showed higher rates of lasting symptoms of chronic stress in HS (in 13; 50%) than in CG (1; 4.2%). There is a higher rate of posttraumatic growth in HS, in 18 (69.2%) than in CG, in 9 (37.5%). SOS-10 displays a lower rate of well-being in HS (6; 23.1%) than in CG (1; 4.2%).

Psychological questionnaires: differences between HS under age of 12 in 1945 and age-matched CG.

3.3.1. Neuroimaging group characteristics

The neuroimaging cohort psychological profile resembled the profile of the whole cohort ( Table 4 ). No gender-associated effects were found using a two-sample t -test comparing male and female data.

Psychological questionnaire results of participants participating in the neuroimaging part of this study.

Psychological test results are similar to those in the entire HS group: a greater rate of chronic stress symptoms (significantly in PCL-C) and a lower rate of well-being in HS. Posttraumatic growth is stronger in the HS group but with a borderline p-value of 0.0504.

3.3.2. GMV reduction in holocaust survivors

VBM showed a significant GM volume reduction in HS in regions described in Table 5 and Fig. 1 .

Holocaust survivors vs control group: Structural MRI, clusters with significant GM reduction compared control group. Initial threshold 0.005 uncorrected, 0.05 FWE cluster level significance.

Structural MRI. Holocaust survivors vs control participants thresholded at 0.005; axial slices.

Significant results up to p = 0.05 FWE cluster level. Larger clusters overlap several structures and can be divided into substructures for interpretation purposes. R – right, L – left, R and L – cluster covering bilateral medial cortices. Coordinates indicate the location with the maximum cluster value.

3.3.3. GMV reduction in holocaust survivors under 12 years in 1945

VBM showed a significant GM volume reduction in HS under 12 years in regions described in Table 6 and Fig. 2 .

Holocaust survivors, age under 12 years in 1945. Structural MRI, clusters with significant GM reduction compared to control group. Initial threshold 0.005 uncorrected, 0.05 FWE cluster level significance.

Significant results up to p = 0.05 FWE cluster level. Larger clusters overlap several structures and can be divided into substructures for interpretation purposes. R – right, L – left, R and L – cluster covering bilateral medial cortices. Coordinates indicate the location with the maximum cluster.

Structural MRI. Holocaust survivors younger than 12 years in 1945 vs control participants, thresholded at 0.005; axial slices.

Structural MRI map of Holocaust survivors younger than 12 years in 1945 vs control participants with a liberal initial threshold of p = 0.01 is presented in Supplementary Material. The comparison of the subgroups of HS under 12 years did not yield a qualitatively different pattern from the comparison of the entire groups of participants when lowering the threshold to compensate for the small group sizes.

3.3.4. Correlation between GMV and PTSD symptoms

We found a significant correlation r = 0.395, p-value = 0.034, between grey matter volume in the stress-related network comprising ACC, OFC, and the insula and PCL-C test score.

4. Discussion

Extreme stress in childhood and young adulthood has an irreversible lifelong impact on the brain. More than 70 years after World War II, it is possible to identify lifelong psychological and neurobiological changes in people who survived the Holocaust as compared to a control group without a similar trauma history. There are apparent persistent differences in the frequency of depression symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and posttraumatic growth, in levels of well-being, and in GM volume in the brain.

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) displayed a significant GM volume reduction in the HS as compared to CG. The areas of reduced grey matter correspond to the map of the impact of stress on the brain structure: insula, anterior cingulate, ventromedial cortex including the subgenual cingulate/orbitofrontal cortex, temporal pole, prefrontal cortex, and angular gyrus. The reduced structures were reported in connection with stress, emotions, affective disorders, autobiographical memory cognition, and behaviour.

The massive reduction of insular volume is of particular note. The insula is functionally linked with other structures that showed volume reduction in HS, in particular with anterior cingulate (ACC), ventromedial prefrontal, and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) ( Perez et al., 2017 ; Phillips et al., 2003 ). The anterior insula may be critical for processing emotions, self-awareness ( Stevens and Jovanovic, 2019 ), and in disorders of mood and anxiety ( Rolls et al., 2018 ).

The ACC is a limbic region associated with a multitude of cognitive and affective processes ( Perez et al., 2017 ) including fear regulation Diekhof et al. (2011) ( Drevets et al., 2008 ); and social behaviour ( Devinsky et al., 1995 ). The medial prefrontal cortex includes the pregenual/subcallosal ACC, subgenual cingulate, and OFC and is associated with the processing of emotions, emotional behaviour, and memory ( Noriuchi et al., 2019 ). The subgenual cingulate (BA 25) is being used as a target for deep brain stimulation therapy for major depression ( Rolls et al., 2018 ).

The temporal pole (TP) is a paralimbic region involved in the regulation of emotion ( Holland et al., 2011 ). A GM reduction in the left medial temporal gyrus and right superior frontal gyrus, possibly associated with autobiographical memory retrieval, was described in PTSD ( Li et al., 2014 ). The angular gyrus is linked to several cognitive functions including self-referential processing ( Stevens and Jovanovic, 2019 ). In a combat veteran PTSD study, the burden of psychological trauma across the lifespan correlated with reduced cortical thickness in limbic/paralimbic areas and in the medial precentral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices ( Lindemer et al., 2013 ).

It can be summarised that the regions with reduced GM volume are associated with functions that could have been influenced by extreme stress. Sustained stress exposure leads to persistent changes in brain circuits regulating behaviour and emotion ( Arnsten et al., 2015 ). This appears even more evident when looking at these regions from the network perspective. The insula is a core region of the salience network that is involved in dynamic prioritising of internal and external stimuli and is implicated in mood/anxiety disorders ( Perez et al., 2017 ). The reduced volume of the insula, ACC, and OFC is considered a sign of increased vulnerability to stress ( Bolsinger et al., 2018 ). Cumulative lifetime adverse events were associated with reduced insular, subgenual ACC, and medial prefrontal volumes ( Ansell et al., 2012 ). The regulation of emotions and of self-awareness are processed in a network composed of the insula and perigenual ACC/ventromedial prefrontal cortex ( Perez et al., 2015 ). The map of reduced GM volume in HS is nearly identical with the set of regions involved in social cognition ( Stevens and Jovanovic, 2019 ).

The affected regions belong to the three core neurocognitive systems crucial for cognitive and affective processing: the salience network, the default mode network, and the central executive network. Deficits in the three networks are associated with a wide range of stress-related psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder ( Menon, 2011 ).

Extreme trauma experienced in childhood has demonstrably lifelong consequences. The reduction of GM was significantly expressed in the young HS, who were under the age of 12 years in 1945. The brains of children are vulnerable despite the fact that children have a limited ability to cognitively process life-threatening situations ( Sigal and Weinfeld, 2001 ). The GM volume reduction in children is probably a consequence of maladaptive experience-dependent neuroplastic changes that are more expressed in a developing brain ( Thomason and Marusak, 2017 ). A lower GM volume in the ACC was found in individuals with prenatal stress ( Marečková et al., 2019 ). Early-life adverse events have been associated with smaller insula, ACC, and OFC ( Dannlowski et al., 2012 ; Rolls et al., 2018 ).

There were no observable changes in the hippocampus and amygdala. The volume reduction of the two structures has been reported in PTSD and affective disorders ( Bremner, 2006 , 2007 ; Teicher et al., 2003 ) but findings are not consistent. Earlier studies also did not find a reduction of the two structures in HS with PTSD ( Cohen et al., 2006 ; Golier et al., 2005 ).

Several hypotheses explain the mechanisms of the alterations in brain structure induced by stress. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis leads the increased release of corticosteroids which can exert a negative effect on neurogenesis and an increase in apoptosis ( Li et al., 2014 ). However, a decrease in GM volume associated with a reduction in glia, with no loss of neurons, was described in ACC ( Drevets et al., 2008 ). In a stress model in mice, the GM reduction was explained by the loss of dendrites ( Blais et al., 1999 ; Kassem et al., 2013 ).

The GM reduction in our study is very probably the consequence of major psychological trauma. It is not explained by the effects of malnutrition on the brains of the survivors, as the majority of surviving children (with significant GM reduction) were hidden in non-Jewish families and did not experience extreme malnutrition. We found a significant correlation between grey matter volume in structures forming the stress network (insula, ACC, OFC) and PCL-C test score. This means that there is a clear link in our data between the grey matter volume and the psychological manifestations of posttraumatic stress symptoms.

To summarise the MRI part of our study: it shows an enduring lifelong effect of extremely stressful trauma on brain structure. The GM reduced areas correspond to the map of the impact of stress on the brain. The published studies mostly report the impact of stress on the human brain after a limited time period and do not address the question of whether the structural changes are reversible. Our data showing the lifelong consequences more than 70 years after extreme stress indicate that the GM reduction is irreversible. On the other hand, it is evident that the consequences of extreme stress can be compensated on a psychological level.

The psychological testing and HS interviews confirmed the profile corresponding to this structural map; however, the life course and other psychological signs display a more complicated and more positive pattern. After World War II, the psychopathology that characterised Holocaust survivors were described as a combination of chronic anxiety, depression, feelings of guilt, emotional instability, memory disturbances, and personality problems, alongside unresolved mourning and sadness ( Barel et al., 2010 ; Chodoff, 1963 ; Graaf, 1975 ; Helweg-Larsen et al., 1952 ; Prager and Solomon, 1995 ; Sagi-Schwartz et al., 2003 ).

In our study, the HS, when compared to CG, presented a more frequent occurrence of symptoms of chronic stress and depression and lower levels of well-being scores. On the other hand, the HS presented signs of resilience that probably considerably influenced their post-war life ( Heitlinger, 2011 ). They presented higher posttraumatic growth than the CG, and their self-estimation of their lives over the more than 70 years since the Holocaust showed a surprisingly positive pattern. The HS declared that they were satisfied with their lifelong personal life (in 79.6%) and with their professional careers (86.4%). That means that most of HS had productive and successful lives despite the atrocities they endured.

Surviving the Holocaust led to different reactions, including frequent suicides after the war. Those who were available for investigations for several decades after the Holocaust showed successful adaption capacities, similar to our study. The meta-analysis by Barel et al. elucidating the long-term consequences of the Holocaust for survivors suggested that alongside profound sadness there is room for growth ( Barel et al., 2010 ). Several studies have provided support for resilience in survivors of other genocides and persecutions, such as in Bosnia and Cambodia ( Ferren, 1999 ; Rousseau et al., 2003 ).

Holocaust survivors are not a homogeneous group and they vary in their post-trauma adjustment. Our study surpasses other published studies in the time that elapsed since the Holocaust – 70 to 75 years. The HS were up to 95 years old. We can speculate that surviving the Holocaust and living to a very advanced age could reflect a personality profile. It has been shown that Polish Holocaust survivors who immigrated to the British Mandate for Palestine after 1945 lived longer than the Polish Jews who immigrated before 1939, i.e. before the Holocaust ( Sagi-Schwartz et al., 2013 ). The results of a study of Holocaust survivors aged 75 and older revealed almost no differences regarding the sociodemographic and interpersonal variables when compared to a control group. Nevertheless, survivors were found to be more vulnerable ( Landau and Litwin, 2000 ).

Based on our data, we suggest that the combination of depression and chronic stress symptoms with GM reduction in critical areas and posttraumatic growth with good adaptation to life present characteristics of Holocaust survivors. It appears that the strong motivation of Holocaust survivors to rebuild their lives manifested itself primarily in raising families, becoming involved in social activities, and showing achievements on a wide spectrum of social functioning ( Joffe et al., 2003 ; Krell, 1993 ). The neurobiological consequence of extreme stress, i.e. reduction of GM in areas related to stress symptoms, may be compensated by resilience and psychological growth. The lifelong consequences of the Holocaust on survivors may help to understand the adaptational challenges for survivors of more recent wars and catastrophic events.

A brief conclusion of our study is that Holocaust survivors continue to show neurobiological and psychological signs of having been traumatised even more than 70 years after the extreme stress. Extreme stress in childhood and young adulthood has an irreversible lifelong impact on the brain.

5. Limitations