Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

Published on March 10, 2023 by Tegan George .

Participant observation is a research method where the researcher immerses themself in a particular social setting or group, observing the behaviors, interactions, and practices of the participants. This can be a valuable method for any research project that seeks to understand the experiences of individuals or groups in a particular social context.

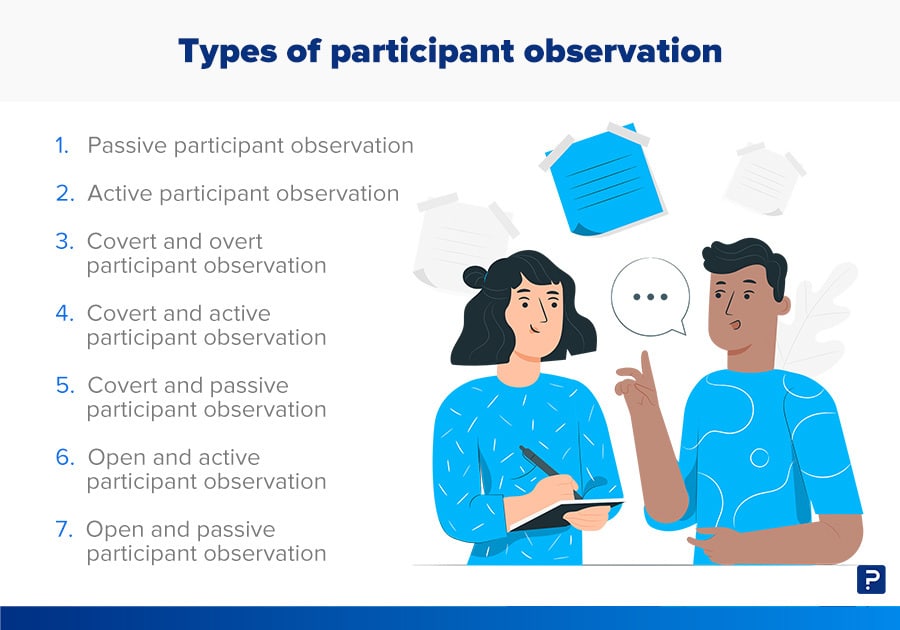

In participant observation, the researcher is called a participant-observer , meaning that they participate in the group’s activities while also observing the group’s behavior and interactions. There is flexibility in the level of participation, ranging from non-participatory (the weakest) to complete participation (the strongest but most intensive.) The goal here is to gain a deep understanding of the group’s culture, beliefs, and practices from an “insider” perspective.

You immerse yourself in this subculture by spending time at skateparks, attending skateboarding events, and engaging with skateboarders. Perhaps you may even learn to skateboard yourself, in order to better understand the experiences of your study participants.

As you observe, you take notes on the behavior, language, norms, and values you witness and also conduct informal unstructured interviews with individual skateboarders to gain further insight into their thoughts and lived experiences.

Typically used in fields like anthropology, sociology, and other social sciences, this method is often used to gather rich and detailed data about social groups or phenomena through ethnographies or other qualitative research .

Table of contents

When to use participant observation, examples of participant observation, how to analyze data from participant observation, advantages and disadvantages of participant observations, other types of research bias, frequently asked questions.

Participant observation is a type of observational study . Like most observational studies, these are primarily qualitative in nature, used to conduct both explanatory research and exploratory research . Participant observation is also often used in conjunction with other types of research, like interviews and surveys .

This type of study is especially well suited for studying social phenomena that are difficult to observe or measure through other methods. As the researcher observes, they typically take detailed notes about their observations and interactions with the group. These are then analyzed to identify patterns and themes using thematic analysis or a similar method.

A participant observation could be a good fit for your research if:

- You are studying subcultures or groups with unique practices or beliefs. Participant observation fosters a deep and intimate understanding of the beliefs, values, and practices of your group or subculture of interest from an insider’s perspective. This can be especially useful when studying marginalized groups or groups that are resistant to observation.

- You are studying complex social interactions . Participant observation can be a powerful tool for studying the complex social interactions that occur within a particular group or community. By immersing yourself in the group and observing these interactions firsthand, you can gain a much more nuanced understanding of how these interactions flow.

- You are studying behaviors or practices that may be difficult to self-report . In some cases, participants may be unwilling or unable to accurately report their own behaviors or practices. Participant observation allows researchers to observe these behaviors directly, allowing for more accuracy in the data collection phase.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Participant observation is a common research method in social sciences, with findings often published in research reports used to inform policymakers or other stakeholders.

Over the course of several months, you observe and take notes on the social interactions, customs, and beliefs of the community members, conducting informal interviews with individual residents to gain further insight into their experiences and perspectives. Through your observations, you gain a deep understanding of the community’s culture, including its values, traditions, and social hierarchy.

Participant observations are often also used in sociology to study social groups and related phenomena, like group formation, stratification, or conflict resolution.

Through this participant observation, you soon see that the group is highly stratified, with certain individuals occupying positions of social power and others being marginalized or even largely excluded. You also observe patterns of conformity within the group, alongside complex interpersonal dynamics.

Data analysis in participant observation typically involves a step-by-step process of immersion, categorization, and interpretation.

- After finishing up your observations, you read through your field notes or transcripts multiple times in the immersion phase. This helps you reflect on what you studied, and is well paired with conducting data cleansing to ensure everything is clear and correct prior to proceeding.

- You then create categories or themes to organize the data. This helps with identifying patterns, behaviors, and interactions relevant to your research question or study aims. In turn, these categories help you to form a coding system that labels or “tags” the aspects of the data that you want to focus on. These can be specific behaviors, emotions, or social interactions—whatever helps you to identify connections between different elements of your data.

- Next, your data can be analyzed using a variety of qualitative research methods, such as thematic analysis , grounded theory, or discourse analysis using the coded categories you created. This helps you interpret the data and develop further theories. You may also want to use triangulation , comparing data from multiple sources or methods, to bolster the reliability and validity of your findings.

- Lastly, it’s always a good research practice to seek feedback on your findings from other researchers in your field of study, as well as members of the group you studied. This helps to ensure the accuracy and reliability of your analysis and can mitigate some potential research biases .

Participant observations are a strong fit for some research projects, but with their advantages come their share of disadvantages as well.

Advantages of participant observations

- Participant observations allow you to generate rich and nuanced qualitative data —particularly useful when seeking to develop a deep understanding of a particular social context or experience. By immersing yourself in the group, you can gain an unrivaled insider perspective on the group’s beliefs, values, and practices.

- Participant observation is a flexible research method that can be adapted to fit a variety of research questions and contexts. Metrics like level of participation in the group, the length of the observation period, and the types of data collected all can be adjusted based on research goals and timeline.

- Participant observation is often used in combination with other research methods, such as interviews or surveys , to provide a more complete picture of the phenomenon being studied. This triangulation can help to improve the reliability and validity of the research findings, as participant observations are not particularly strong as a standalone method.

Disadvantages of participant observations

- Like many observational studies, participant observations are at high risk for many research biases , particularly on the side of the researcher. Because participant observation involves the researcher immersing themselves in the group being studied, there is a risk that their own biases could influence the data they collect, leading to observer bias . Likewise, the presence of a researcher in the group being studied can potentially influence the behavior of the participants. This can lead to inaccurate or biased data if participants alter their behavior in response to the researcher’s presence, leading to a Hawthorne effect or social desirability bias .

- Participant observations can be very expensive, time-consuming, and challenging to carry out. They often require a long period of time to build trust and gather sufficient data, with the data usually collected in an intensive, in-person manner. Some participant observations take generations to complete, which can make it difficult to conduct studies with limited time or resources.

- Participant observation can raise ethical concerns , requiring measured ethical consideration on the part of the researcher with regard to informed consent, privacy, and confidentiality. The researcher must take care to protect the privacy and autonomy of the participants and ensure that they are not placed at undue risk by the research.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

- Confirmation bias

- Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Hindsight bias

- Ingroup bias

- Outgroup bias

- Perception bias

- Framing effect

- Self-serving bias

- Affect heuristic

- Representativeness heuristic

- Anchoring heuristic

- Primacy bias

- Optimism bias

- Sampling bias

- Ascertainment bias

- Attrition bias

- Self-selection bias

- Survivorship bias

- Nonresponse bias

- Undercoverage bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Observer bias

- Omitted variable bias

- Publication bias

- Conformity bias

- Pygmalion effect

- Recall bias

- Social desirability bias

- Placebo effect

- Actor-observer bias

- Ceiling effect

- Ecological fallacy

- Affinity bias

Ethical considerations in participant observation involve:

- Obtaining informed consent from all participants

- Protecting their privacy and confidentiality

- Ensuring that they are not placed at undue risk by the research, and

- Respecting their autonomy and agency as participants

Researchers should also consider the potential impact of their research on the community being studied and take steps to minimize any negative after-effects.

Participant observation is a type of qualitative research method . It involves active participation on the part of the researcher in the group being studied, usually over a longer period of time.

Other qualitative research methods, such as interviews or focus groups , do not involve the same level of immersion in the research and can be conducted in a less intense manner.

In participant observation , the researcher plays an active role in the social phenomenon, group, or social context being studied. They may move into the community, attend events or activities, or even take on specific roles within the group— fully joining the community over the course of the study. However, the researcher also maintains an observer role here, taking notes on the behavior and interactions of the participants to draw conclusions and guide further research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, March 10). What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/participant-observation/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, what is an observational study | guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Participant Selection and Access in Case Study Research

- First Online: 05 January 2019

Cite this chapter

- Zhongyan Wan 4

1598 Accesses

2 Citations

Case study research requires researchers to purposefully select information-rich cases, as they will allow researchers an in-depth understanding of relevant and critical issues under investigation (Patton in Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage, Newbury Park, 1990 , Qual Soc Work 1(3):261–283, 2002 ). To gain such insights, purposive sampling is generally believed to contribute to the richness in the range of data collected and help increase the possibilities of uncovering multiple realities (Guba and Lincoln in Handb Qual Res 2(163–194):105, 1994 ). However, dealing with research participants in the case study approach also poses great challenges for novice researchers, as humans can be a difficult factor to control among the variables in research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Questionable Research Practices in Single-Case Experimental Designs: Examples and Possible Solutions

Case Study Research

Alinejad, D. (2011). Mapping homelands through virtual spaces: Transnational embodiment and Iranian diaspora bloggers. Global Networks, 11 (1), 43–62.

Google Scholar

Arcury, T., & Quandt, S. (1999). Participant recruitment for qualitative research: A site-based approach to community research in complex societies. Human Organization, 58 (2), 128–133.

Article Google Scholar

Barbour, R. (2014). Introducing qualitative research: A student’s guide . London: Sage.

Decrop, A. (1999). Qualitative research methods for the study of tourist behaviour. In A. Pizam & Y. Mansfeld. (Eds.), Consumer Behaviour in Travel and Tourism . New York: The Haworth Hospitality Press

Duff, P. (2008). Case study research in applied linguistics . New York: Taylor & Francis.

Feldman, M. S., Bell, J., & Berger, M. T. (2003). Gaining access: A practical and theoretical guide for qualitative researchers . Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. T. (2003). Educational research (7th ed.). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? American Political Science Review, 98 (02), 341–354.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2 (163–194), 105.

Gummesson, E. (2000). Qualitative methods in management research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hamilton, R. J., & Bowers, B. J. (2006). Internet recruitment and e-mail interviews in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research, 16 (6), 821–835.

Hancock, D. R., & Algozzine, B. (2015). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers . New York: Teachers College Press.

Hewson, C. (2014). Qualitative approaches in Internet-mediated research: Opportunities, issues, possibilities. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research , 423–452.

Johl, S. K., & Renganathan, S. (2010). Strategies for gaining access in doing fieldwork: Reflection of two researchers. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 8 (1), 42–50.

Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques . India: New Age International.

Lee, R. (1993). Doing research on sensitive topics . London: Sage.

Merriam, S. (2009). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mikecz, R. (2012). Interviewing elites addressing methodological issues. Qualitative Inquiry, 18 (6), 482–493.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Noy, C. (2008). Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 327–344.

Okumus, F., Altinay, L., & Roper, A. (2007). Gaining access for research: Reflections from experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 34 (1), 7–26.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry a personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1 (3), 261–283.

Punch, K. F. (1998). Introduction to social research . London: Sage.

Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61 (2), 294–308.

Silverman, D. (Ed.). (2016). Qualitative research . London: Sage.

Thomas, G. (2015). How to do your case study . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wan, Z. Y. (2016). College teacher beliefs and practices in computer-assisted language learning classrooms in China . Shanghai: Shanghai Jiaotong University Press.

Willis, J. W., Jost, M., & Nilakanta, R. (2007). Foundations of qualitative research: Interpretive and critical approaches . London: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Wilmot, A. (2005). Designing sampling strategies for qualitative social research: With particular reference to the Office for National Statistics’ Qualitative Respondent Register. Survey Methodology Bulletin-office for National Statistics, 56, 53.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). London: Sage publications.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Foreign Language Department, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, China

Zhongyan Wan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zhongyan Wan .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

Kwok Kuen Tsang

Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

School of Humanities, Southeast University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Wan, Z. (2019). Participant Selection and Access in Case Study Research. In: Tsang, K., Liu, D., Hong, Y. (eds) Challenges and Opportunities in Qualitative Research. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-5811-1_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-5811-1_5

Published : 05 January 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-5810-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-5811-1

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Transformative Design – Methods, Types, Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types...

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Case Studies

This guide examines case studies, a form of qualitative descriptive research that is used to look at individuals, a small group of participants, or a group as a whole. Researchers collect data about participants using participant and direct observations, interviews, protocols, tests, examinations of records, and collections of writing samples. Starting with a definition of the case study, the guide moves to a brief history of this research method. Using several well documented case studies, the guide then looks at applications and methods including data collection and analysis. A discussion of ways to handle validity, reliability, and generalizability follows, with special attention to case studies as they are applied to composition studies. Finally, this guide examines the strengths and weaknesses of case studies.

Definition and Overview

Case study refers to the collection and presentation of detailed information about a particular participant or small group, frequently including the accounts of subjects themselves. A form of qualitative descriptive research, the case study looks intensely at an individual or small participant pool, drawing conclusions only about that participant or group and only in that specific context. Researchers do not focus on the discovery of a universal, generalizable truth, nor do they typically look for cause-effect relationships; instead, emphasis is placed on exploration and description.

Case studies typically examine the interplay of all variables in order to provide as complete an understanding of an event or situation as possible. This type of comprehensive understanding is arrived at through a process known as thick description, which involves an in-depth description of the entity being evaluated, the circumstances under which it is used, the characteristics of the people involved in it, and the nature of the community in which it is located. Thick description also involves interpreting the meaning of demographic and descriptive data such as cultural norms and mores, community values, ingrained attitudes, and motives.

Unlike quantitative methods of research, like the survey, which focus on the questions of who, what, where, how much, and how many, and archival analysis, which often situates the participant in some form of historical context, case studies are the preferred strategy when how or why questions are asked. Likewise, they are the preferred method when the researcher has little control over the events, and when there is a contemporary focus within a real life context. In addition, unlike more specifically directed experiments, case studies require a problem that seeks a holistic understanding of the event or situation in question using inductive logic--reasoning from specific to more general terms.

In scholarly circles, case studies are frequently discussed within the context of qualitative research and naturalistic inquiry. Case studies are often referred to interchangeably with ethnography, field study, and participant observation. The underlying philosophical assumptions in the case are similar to these types of qualitative research because each takes place in a natural setting (such as a classroom, neighborhood, or private home), and strives for a more holistic interpretation of the event or situation under study.

Unlike more statistically-based studies which search for quantifiable data, the goal of a case study is to offer new variables and questions for further research. F.H. Giddings, a sociologist in the early part of the century, compares statistical methods to the case study on the basis that the former are concerned with the distribution of a particular trait, or a small number of traits, in a population, whereas the case study is concerned with the whole variety of traits to be found in a particular instance" (Hammersley 95).

Case studies are not a new form of research; naturalistic inquiry was the primary research tool until the development of the scientific method. The fields of sociology and anthropology are credited with the primary shaping of the concept as we know it today. However, case study research has drawn from a number of other areas as well: the clinical methods of doctors; the casework technique being developed by social workers; the methods of historians and anthropologists, plus the qualitative descriptions provided by quantitative researchers like LePlay; and, in the case of Robert Park, the techniques of newspaper reporters and novelists.

Park was an ex-newspaper reporter and editor who became very influential in developing sociological case studies at the University of Chicago in the 1920s. As a newspaper professional he coined the term "scientific" or "depth" reporting: the description of local events in a way that pointed to major social trends. Park viewed the sociologist as "merely a more accurate, responsible, and scientific reporter." Park stressed the variety and value of human experience. He believed that sociology sought to arrive at natural, but fluid, laws and generalizations in regard to human nature and society. These laws weren't static laws of the kind sought by many positivists and natural law theorists, but rather, they were laws of becoming--with a constant possibility of change. Park encouraged students to get out of the library, to quit looking at papers and books, and to view the constant experiment of human experience. He writes, "Go and sit in the lounges of the luxury hotels and on the doorsteps of the flophouses; sit on the Gold Coast settees and on the slum shakedowns; sit in the Orchestra Hall and in the Star and Garter Burlesque. In short, gentlemen [sic], go get the seats of your pants dirty in real research."

But over the years, case studies have drawn their share of criticism. In fact, the method had its detractors from the start. In the 1920s, the debate between pro-qualitative and pro-quantitative became quite heated. Case studies, when compared to statistics, were considered by many to be unscientific. From the 1930's on, the rise of positivism had a growing influence on quantitative methods in sociology. People wanted static, generalizable laws in science. The sociological positivists were looking for stable laws of social phenomena. They criticized case study research because it failed to provide evidence of inter subjective agreement. Also, they condemned it because of the few number of cases studied and that the under-standardized character of their descriptions made generalization impossible. By the 1950s, quantitative methods, in the form of survey research, had become the dominant sociological approach and case study had become a minority practice.

Educational Applications

The 1950's marked the dawning of a new era in case study research, namely that of the utilization of the case study as a teaching method. "Instituted at Harvard Business School in the 1950s as a primary method of teaching, cases have since been used in classrooms and lecture halls alike, either as part of a course of study or as the main focus of the course to which other teaching material is added" (Armisted 1984). The basic purpose of instituting the case method as a teaching strategy was "to transfer much of the responsibility for learning from the teacher on to the student, whose role, as a result, shifts away from passive absorption toward active construction" (Boehrer 1990). Through careful examination and discussion of various cases, "students learn to identify actual problems, to recognize key players and their agendas, and to become aware of those aspects of the situation that contribute to the problem" (Merseth 1991). In addition, students are encouraged to "generate their own analysis of the problems under consideration, to develop their own solutions, and to practically apply their own knowledge of theory to these problems" (Boyce 1993). Along the way, students also develop "the power to analyze and to master a tangled circumstance by identifying and delineating important factors; the ability to utilize ideas, to test them against facts, and to throw them into fresh combinations" (Merseth 1991).

In addition to the practical application and testing of scholarly knowledge, case discussions can also help students prepare for real-world problems, situations and crises by providing an approximation of various professional environments (i.e. classroom, board room, courtroom, or hospital). Thus, through the examination of specific cases, students are given the opportunity to work out their own professional issues through the trials, tribulations, experiences, and research findings of others. An obvious advantage to this mode of instruction is that it allows students the exposure to settings and contexts that they might not otherwise experience. For example, a student interested in studying the effects of poverty on minority secondary student's grade point averages and S.A.T. scores could access and analyze information from schools as geographically diverse as Los Angeles, New York City, Miami, and New Mexico without ever having to leave the classroom.

The case study method also incorporates the idea that students can learn from one another "by engaging with each other and with each other's ideas, by asserting something and then having it questioned, challenged and thrown back at them so that they can reflect on what they hear, and then refine what they say" (Boehrer 1990). In summary, students can direct their own learning by formulating questions and taking responsibility for the study.

Types and Design Concerns

Researchers use multiple methods and approaches to conduct case studies.

Types of Case Studies

Under the more generalized category of case study exist several subdivisions, each of which is custom selected for use depending upon the goals and/or objectives of the investigator. These types of case study include the following:

Illustrative Case Studies These are primarily descriptive studies. They typically utilize one or two instances of an event to show what a situation is like. Illustrative case studies serve primarily to make the unfamiliar familiar and to give readers a common language about the topic in question.

Exploratory (or pilot) Case Studies These are condensed case studies performed before implementing a large scale investigation. Their basic function is to help identify questions and select types of measurement prior to the main investigation. The primary pitfall of this type of study is that initial findings may seem convincing enough to be released prematurely as conclusions.

Cumulative Case Studies These serve to aggregate information from several sites collected at different times. The idea behind these studies is the collection of past studies will allow for greater generalization without additional cost or time being expended on new, possibly repetitive studies.

Critical Instance Case Studies These examine one or more sites for either the purpose of examining a situation of unique interest with little to no interest in generalizability, or to call into question or challenge a highly generalized or universal assertion. This method is useful for answering cause and effect questions.

Identifying a Theoretical Perspective

Much of the case study's design is inherently determined for researchers, depending on the field from which they are working. In composition studies, researchers are typically working from a qualitative, descriptive standpoint. In contrast, physicists will approach their research from a more quantitative perspective. Still, in designing the study, researchers need to make explicit the questions to be explored and the theoretical perspective from which they will approach the case. The three most commonly adopted theories are listed below:

Individual Theories These focus primarily on the individual development, cognitive behavior, personality, learning and disability, and interpersonal interactions of a particular subject.

Organizational Theories These focus on bureaucracies, institutions, organizational structure and functions, or excellence in organizational performance.

Social Theories These focus on urban development, group behavior, cultural institutions, or marketplace functions.

Two examples of case studies are used consistently throughout this chapter. The first, a study produced by Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988), looks at a first year graduate student's initiation into an academic writing program. The study uses participant-observer and linguistic data collecting techniques to assess the student's knowledge of appropriate discourse conventions. Using the pseudonym Nate to refer to the subject, the study sought to illuminate the particular experience rather than to generalize about the experience of fledgling academic writers collectively.

For example, in Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman's (1988) study we are told that the researchers are interested in disciplinary communities. In the first paragraph, they ask what constitutes membership in a disciplinary community and how achieving membership might affect a writer's understanding and production of texts. In the third paragraph they state that researchers must negotiate their claims "within the context of his sub specialty's accepted knowledge and methodology." In the next paragraph they ask, "How is literacy acquired? What is the process through which novices gain community membership? And what factors either aid or hinder students learning the requisite linguistic behaviors?" This introductory section ends with a paragraph in which the study's authors claim that during the course of the study, the subject, Nate, successfully makes the transition from "skilled novice" to become an initiated member of the academic discourse community and that his texts exhibit linguistic changes which indicate this transition. In the next section the authors make explicit the sociolinguistic theoretical and methodological assumptions on which the study is based (1988). Thus the reader has a good understanding of the authors' theoretical background and purpose in conducting the study even before it is explicitly stated on the fourth page of the study. "Our purpose was to examine the effects of the educational context on one graduate student's production of texts as he wrote in different courses and for different faculty members over the academic year 1984-85." The goal of the study then, was to explore the idea that writers must be initiated into a writing community, and that this initiation will change the way one writes.

The second example is Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composing process of a group of twelfth graders. In this study, Emig seeks to answer the question of what happens to the self as a result educational stimuli in terms of academic writing. The case study used methods such as protocol analysis, tape-recorded interviews, and discourse analysis.

In the case of Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composing process of eight twelfth graders, four specific hypotheses were made:

- Twelfth grade writers engage in two modes of composing: reflexive and extensive.

- These differences can be ascertained and characterized through having the writers compose aloud their composition process.

- A set of implied stylistic principles governs the writing process.

- For twelfth grade writers, extensive writing occurs chiefly as a school-sponsored activity, or reflexive, as a self-sponsored activity.

In this study, the chief distinction is between the two dominant modes of composing among older, secondary school students. The distinctions are:

- The reflexive mode, which focuses on the writer's thoughts and feelings.

- The extensive mode, which focuses on conveying a message.

Emig also outlines the specific questions which guided the research in the opening pages of her Review of Literature , preceding the report.

Designing a Case Study

After considering the different sub categories of case study and identifying a theoretical perspective, researchers can begin to design their study. Research design is the string of logic that ultimately links the data to be collected and the conclusions to be drawn to the initial questions of the study. Typically, research designs deal with at least four problems:

- What questions to study

- What data are relevant

- What data to collect

- How to analyze that data

In other words, a research design is basically a blueprint for getting from the beginning to the end of a study. The beginning is an initial set of questions to be answered, and the end is some set of conclusions about those questions.

Because case studies are conducted on topics as diverse as Anglo-Saxon Literature (Thrane 1986) and AIDS prevention (Van Vugt 1994), it is virtually impossible to outline any strict or universal method or design for conducting the case study. However, Robert K. Yin (1993) does offer five basic components of a research design:

- A study's questions.

- A study's propositions (if any).

- A study's units of analysis.

- The logic that links the data to the propositions.

- The criteria for interpreting the findings.

In addition to these five basic components, Yin also stresses the importance of clearly articulating one's theoretical perspective, determining the goals of the study, selecting one's subject(s), selecting the appropriate method(s) of collecting data, and providing some considerations to the composition of the final report.

Conducting Case Studies

To obtain as complete a picture of the participant as possible, case study researchers can employ a variety of approaches and methods. These approaches, methods, and related issues are discussed in depth in this section.

Method: Single or Multi-modal?

To obtain as complete a picture of the participant as possible, case study researchers can employ a variety of methods. Some common methods include interviews , protocol analyses, field studies, and participant-observations. Emig (1971) chose to use several methods of data collection. Her sources included conversations with the students, protocol analysis, discrete observations of actual composition, writing samples from each student, and school records (Lauer and Asher 1988).

Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) collected data by observing classrooms, conducting faculty and student interviews, collecting self reports from the subject, and by looking at the subject's written work.

A study that was criticized for using a single method model was done by Flower and Hayes (1984). In this study that explores the ways in which writers use different forms of knowing to create space, the authors used only protocol analysis to gather data. The study came under heavy fire because of their decision to use only one method.

Participant Selection

Case studies can use one participant, or a small group of participants. However, it is important that the participant pool remain relatively small. The participants can represent a diverse cross section of society, but this isn't necessary.

For example, the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study looked at just one participant, Nate. By contrast, in Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composition process of twelfth graders, eight participants were selected representing a diverse cross section of the community, with volunteers from an all-white upper-middle-class suburban school, an all-black inner-city school, a racially mixed lower-middle-class school, an economically and racially mixed school, and a university school.

Often, a brief "case history" is done on the participants of the study in order to provide researchers with a clearer understanding of their participants, as well as some insight as to how their own personal histories might affect the outcome of the study. For instance, in Emig's study, the investigator had access to the school records of five of the participants, and to standardized test scores for the remaining three. Also made available to the researcher was the information that three of the eight students were selected as NCTE Achievement Award winners. These personal histories can be useful in later stages of the study when data are being analyzed and conclusions drawn.

Data Collection

There are six types of data collected in case studies:

- Archival records.

- Interviews.

- Direct observation.

- Participant observation.

In the field of composition research, these six sources might be:

- A writer's drafts.

- School records of student writers.

- Transcripts of interviews with a writer.

- Transcripts of conversations between writers (and protocols).

- Videotapes and notes from direct field observations.

- Hard copies of a writer's work on computer.

Depending on whether researchers have chosen to use a single or multi-modal approach for the case study, they may choose to collect data from one or any combination of these sources.

Protocols, that is, transcriptions of participants talking aloud about what they are doing as they do it, have been particularly common in composition case studies. For example, in Emig's (1971) study, the students were asked, in four different sessions, to give oral autobiographies of their writing experiences and to compose aloud three themes in the presence of a tape recorder and the investigator.

In some studies, only one method of data collection is conducted. For example, the Flower and Hayes (1981) report on the cognitive process theory of writing depends on protocol analysis alone. However, using multiple sources of evidence to increase the reliability and validity of the data can be advantageous.

Case studies are likely to be much more convincing and accurate if they are based on several different sources of information, following a corroborating mode. This conclusion is echoed among many composition researchers. For example, in her study of predrafting processes of high and low-apprehensive writers, Cynthia Selfe (1985) argues that because "methods of indirect observation provide only an incomplete reflection of the complex set of processes involved in composing, a combination of several such methods should be used to gather data in any one study." Thus, in this study, Selfe collected her data from protocols, observations of students role playing their writing processes, audio taped interviews with the students, and videotaped observations of the students in the process of composing.

It can be said then, that cross checking data from multiple sources can help provide a multidimensional profile of composing activities in a particular setting. Sharan Merriam (1985) suggests "checking, verifying, testing, probing, and confirming collected data as you go, arguing that this process will follow in a funnel-like design resulting in less data gathering in later phases of the study along with a congruent increase in analysis checking, verifying, and confirming."

It is important to note that in case studies, as in any qualitative descriptive research, while researchers begin their studies with one or several questions driving the inquiry (which influence the key factors the researcher will be looking for during data collection), a researcher may find new key factors emerging during data collection. These might be unexpected patterns or linguistic features which become evident only during the course of the research. While not bearing directly on the researcher's guiding questions, these variables may become the basis for new questions asked at the end of the report, thus linking to the possibility of further research.

Data Analysis

As the information is collected, researchers strive to make sense of their data. Generally, researchers interpret their data in one of two ways: holistically or through coding. Holistic analysis does not attempt to break the evidence into parts, but rather to draw conclusions based on the text as a whole. Flower and Hayes (1981), for example, make inferences from entire sections of their students' protocols, rather than searching through the transcripts to look for isolatable characteristics.

However, composition researchers commonly interpret their data by coding, that is by systematically searching data to identify and/or categorize specific observable actions or characteristics. These observable actions then become the key variables in the study. Sharan Merriam (1988) suggests seven analytic frameworks for the organization and presentation of data:

- The role of participants.

- The network analysis of formal and informal exchanges among groups.

- Historical.

- Thematical.

- Ritual and symbolism.

- Critical incidents that challenge or reinforce fundamental beliefs, practices, and values.

There are two purposes of these frameworks: to look for patterns among the data and to look for patterns that give meaning to the case study.

As stated above, while most researchers begin their case studies expecting to look for particular observable characteristics, it is not unusual for key variables to emerge during data collection. Typical variables coded in case studies of writers include pauses writers make in the production of a text, the use of specific linguistic units (such as nouns or verbs), and writing processes (planning, drafting, revising, and editing). In the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study, for example, researchers coded the participant's texts for use of connectives, discourse demonstratives, average sentence length, off-register words, use of the first person pronoun, and the ratio of definite articles to indefinite articles.

Since coding is inherently subjective, more than one coder is usually employed. In the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study, for example, three rhetoricians were employed to code the participant's texts for off-register phrases. The researchers established the agreement among the coders before concluding that the participant used fewer off-register words as the graduate program progressed.

Composing the Case Study Report

In the many forms it can take, "a case study is generically a story; it presents the concrete narrative detail of actual, or at least realistic events, it has a plot, exposition, characters, and sometimes even dialogue" (Boehrer 1990). Generally, case study reports are extensively descriptive, with "the most problematic issue often referred to as being the determination of the right combination of description and analysis" (1990). Typically, authors address each step of the research process, and attempt to give the reader as much context as possible for the decisions made in the research design and for the conclusions drawn.

This contextualization usually includes a detailed explanation of the researchers' theoretical positions, of how those theories drove the inquiry or led to the guiding research questions, of the participants' backgrounds, of the processes of data collection, of the training and limitations of the coders, along with a strong attempt to make connections between the data and the conclusions evident.

Although the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study does not, case study reports often include the reactions of the participants to the study or to the researchers' conclusions. Because case studies tend to be exploratory, most end with implications for further study. Here researchers may identify significant variables that emerged during the research and suggest studies related to these, or the authors may suggest further general questions that their case study generated.

For example, Emig's (1971) study concludes with a section dedicated solely to the topic of implications for further research, in which she suggests several means by which this particular study could have been improved, as well as questions and ideas raised by this study which other researchers might like to address, such as: is there a correlation between a certain personality and a certain composing process profile (e.g. is there a positive correlation between ego strength and persistence in revising)?

Also included in Emig's study is a section dedicated to implications for teaching, which outlines the pedagogical ramifications of the study's findings for teachers currently involved in high school writing programs.

Sharan Merriam (1985) also offers several suggestions for alternative presentations of data:

- Prepare specialized condensations for appropriate groups.

- Replace narrative sections with a series of answers to open-ended questions.

- Present "skimmer's" summaries at beginning of each section.

- Incorporate headlines that encapsulate information from text.

- Prepare analytic summaries with supporting data appendixes.

- Present data in colorful and/or unique graphic representations.

Issues of Validity and Reliability

Once key variables have been identified, they can be analyzed. Reliability becomes a key concern at this stage, and many case study researchers go to great lengths to ensure that their interpretations of the data will be both reliable and valid. Because issues of validity and reliability are an important part of any study in the social sciences, it is important to identify some ways of dealing with results.

Multi-modal case study researchers often balance the results of their coding with data from interviews or writer's reflections upon their own work. Consequently, the researchers' conclusions become highly contextualized. For example, in a case study which looked at the time spent in different stages of the writing process, Berkenkotter concluded that her participant, Donald Murray, spent more time planning his essays than in other writing stages. The report of this case study is followed by Murray's reply, wherein he agrees with some of Berkenkotter's conclusions and disagrees with others.

As is the case with other research methodologies, issues of external validity, construct validity, and reliability need to be carefully considered.

Commentary on Case Studies

Researchers often debate the relative merits of particular methods, among them case study. In this section, we comment on two key issues. To read the commentaries, choose any of the items below:

Strengths and Weaknesses of Case Studies

Most case study advocates point out that case studies produce much more detailed information than what is available through a statistical analysis. Advocates will also hold that while statistical methods might be able to deal with situations where behavior is homogeneous and routine, case studies are needed to deal with creativity, innovation, and context. Detractors argue that case studies are difficult to generalize because of inherent subjectivity and because they are based on qualitative subjective data, generalizable only to a particular context.

Flexibility

The case study approach is a comparatively flexible method of scientific research. Because its project designs seem to emphasize exploration rather than prescription or prediction, researchers are comparatively freer to discover and address issues as they arise in their experiments. In addition, the looser format of case studies allows researchers to begin with broad questions and narrow their focus as their experiment progresses rather than attempt to predict every possible outcome before the experiment is conducted.

Emphasis on Context

By seeking to understand as much as possible about a single subject or small group of subjects, case studies specialize in "deep data," or "thick description"--information based on particular contexts that can give research results a more human face. This emphasis can help bridge the gap between abstract research and concrete practice by allowing researchers to compare their firsthand observations with the quantitative results obtained through other methods of research.

Inherent Subjectivity

"The case study has long been stereotyped as the weak sibling among social science methods," and is often criticized as being too subjective and even pseudo-scientific. Likewise, "investigators who do case studies are often regarded as having deviated from their academic disciplines, and their investigations as having insufficient precision (that is, quantification), objectivity and rigor" (Yin 1989). Opponents cite opportunities for subjectivity in the implementation, presentation, and evaluation of case study research. The approach relies on personal interpretation of data and inferences. Results may not be generalizable, are difficult to test for validity, and rarely offer a problem-solving prescription. Simply put, relying on one or a few subjects as a basis for cognitive extrapolations runs the risk of inferring too much from what might be circumstance.

High Investment

Case studies can involve learning more about the subjects being tested than most researchers would care to know--their educational background, emotional background, perceptions of themselves and their surroundings, their likes, dislikes, and so on. Because of its emphasis on "deep data," the case study is out of reach for many large-scale research projects which look at a subject pool in the tens of thousands. A budget request of $10,000 to examine 200 subjects sounds more efficient than a similar request to examine four subjects.

Ethical Considerations

Researchers conducting case studies should consider certain ethical issues. For example, many educational case studies are often financed by people who have, either directly or indirectly, power over both those being studied and those conducting the investigation (1985). This conflict of interests can hinder the credibility of the study.

The personal integrity, sensitivity, and possible prejudices and/or biases of the investigators need to be taken into consideration as well. Personal biases can creep into how the research is conducted, alternative research methods used, and the preparation of surveys and questionnaires.

A common complaint in case study research is that investigators change direction during the course of the study unaware that their original research design was inadequate for the revised investigation. Thus, the researchers leave unknown gaps and biases in the study. To avoid this, researchers should report preliminary findings so that the likelihood of bias will be reduced.

Concerns about Reliability, Validity, and Generalizability

Merriam (1985) offers several suggestions for how case study researchers might actively combat the popular attacks on the validity, reliability, and generalizability of case studies:

- Prolong the Processes of Data Gathering on Site: This will help to insure the accuracy of the findings by providing the researcher with more concrete information upon which to formulate interpretations.

- Employ the Process of "Triangulation": Use a variety of data sources as opposed to relying solely upon one avenue of observation. One example of such a data check would be what McClintock, Brannon, and Maynard (1985) refer to as a "case cluster method," that is, when a single unit within a larger case is randomly sampled, and that data treated quantitatively." For instance, in Emig's (1971) study, the case cluster method was employed, singling out the productivity of a single student named Lynn. This cluster profile included an advanced case history of the subject, specific examination and analysis of individual compositions and protocols, and extensive interview sessions. The seven remaining students were then compared with the case of Lynn, to ascertain if there are any shared, or unique dimensions to the composing process engaged in by these eight students.

- Conduct Member Checks: Initiate and maintain an active corroboration on the interpretation of data between the researcher and those who provided the data. In other words, talk to your subjects.

- Collect Referential Materials: Complement the file of materials from the actual site with additional document support. For example, Emig (1971) supports her initial propositions with historical accounts by writers such as T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and D.H. Lawrence. Emig also cites examples of theoretical research done with regards to the creative process, as well as examples of empirical research dealing with the writing of adolescents. Specific attention is then given to the four stages description of the composing process delineated by Helmoltz, Wallas, and Cowley, as it serves as the focal point in this study.

- Engage in Peer Consultation: Prior to composing the final draft of the report, researchers should consult with colleagues in order to establish validity through pooled judgment.

Although little can be done to combat challenges concerning the generalizability of case studies, "most writers suggest that qualitative research should be judged as credible and confirmable as opposed to valid and reliable" (Merriam 1985). Likewise, it has been argued that "rather than transplanting statistical, quantitative notions of generalizability and thus finding qualitative research inadequate, it makes more sense to develop an understanding of generalization that is congruent with the basic characteristics of qualitative inquiry" (1985). After all, criticizing the case study method for being ungeneralizable is comparable to criticizing a washing machine for not being able to tell the correct time. In other words, it is unjust to criticize a method for not being able to do something which it was never originally designed to do in the first place.

Annotated Bibliography

Armisted, C. (1984). How Useful are Case Studies. Training and Development Journal, 38 (2), 75-77.

This article looks at eight types of case studies, offers pros and cons of using case studies in the classroom, and gives suggestions for successfully writing and using case studies.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1997). Beyond Methods: Components of Second Language Teacher Education . New York: McGraw-Hill.

A compilation of various research essays which address issues of language teacher education. Essays included are: "Non-native reading research and theory" by Lee, "The case for Psycholinguistics" by VanPatten, and "Assessment and Second Language Teaching" by Gradman and Reed.

Bartlett, L. (1989). A Question of Good Judgment; Interpretation Theory and Qualitative Enquiry Address. 70th Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Francisco.

Bartlett selected "quasi-historical" methodology, which focuses on the "truth" found in case records, as one that will provide "good judgments" in educational inquiry. He argues that although the method is not comprehensive, it can try to connect theory with practice.

Baydere, S. et. al. (1993). Multimedia conferencing as a tool for collaborative writing: a case study in Computer Supported Collaborative Writing. New York: Springer-Verlag.

The case study by Baydere et. al. is just one of the many essays in this book found in the series "Computer Supported Cooperative Work." Denley, Witefield and May explore similar issues in their essay, "A case study in task analysis for the design of a collaborative document production system."

Berkenkotter, C., Huckin, T., N., & Ackerman J. (1988). Conventions, Conversations, and the Writer: Case Study of a Student in a Rhetoric Ph.D. Program. Research in the Teaching of English, 22, 9-44.

The authors focused on how the writing of their subject, Nate or Ackerman, changed as he became more acquainted or familiar with his field's discourse community.

Berninger, V., W., and Gans, B., M. (1986). Language Profiles in Nonspeaking Individuals of Normal Intelligence with Severe Cerebral Palsy. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 2, 45-50.

Argues that generalizations about language abilities in patients with severe cerebral palsy (CP) should be avoided. Standardized tests of different levels of processing oral language, of processing written language, and of producing written language were administered to 3 male participants (aged 9, 16, and 40 yrs).

Bockman, J., R., and Couture, B. (1984). The Case Method in Technical Communication: Theory and Models. Texas: Association of Teachers of Technical Writing.

Examines the study and teaching of technical writing, communication of technical information, and the case method in terms of those applications.

Boehrer, J. (1990). Teaching With Cases: Learning to Question. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 42 41-57.

This article discusses the origins of the case method, looks at the question of what is a case, gives ideas about learning in case teaching, the purposes it can serve in the classroom, the ground rules for the case discussion, including the role of the question, and new directions for case teaching.

Bowman, W. R. (1993). Evaluating JTPA Programs for Economically Disadvantaged Adults: A Case Study of Utah and General Findings . Washington: National Commission for Employment Policy.

"To encourage state-level evaluations of JTPA, the Commission and the State of Utah co-sponsored this report on the effectiveness of JTPA Title II programs for adults in Utah. The technique used is non-experimental and the comparison group was selected from registrants with Utah's Employment Security. In a step-by-step approach, the report documents how non-experimental techniques can be applied and several specific technical issues can be addressed."

Boyce, A. (1993) The Case Study Approach for Pedagogists. Annual Meeting of the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. (Address). Washington DC.