- Browse Topics

- Executive Committee

- Affiliated Faculty

- Harvard Negotiation Project

- Great Negotiator

- American Secretaries of State Project

- Awards, Grants, and Fellowships

- Negotiation Programs

- Mediation Programs

- One-Day Programs

- In-House Training and Custom Programs

- In-Person Programs

- Online Programs

- Advanced Materials Search

- Contact Information

- The Teaching Negotiation Resource Center Policies

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Negotiation Journal

- Harvard Negotiation Law Review

- Working Conference on AI, Technology, and Negotiation

- Free Reports and Program Guides

Free Videos

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Event Series

- Our Mission

- Keyword Index

PON – Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School - https://www.pon.harvard.edu

Team-Building Strategies: Building a Winning Team for Your Organization

Discover how to build a winning team and boost your business negotiation results in this free special report, Team Building Strategies for Your Organization, from Harvard Law School.

- The Contingency Theory of Leadership: A Focus on Fit

The contingency theory of leadership diverges from many other leadership theories in its assertion that leaders should fill roles that best suit their natural inclinations rather than trying to adapt their style to the situation. Here’s a closer look at this intriguing and enduring leadership theory.

By Katie Shonk — on March 21st, 2024 / Leadership Skills

When choosing our personal leadership style, we have many different models to choose from, including participative leadership , charismatic leadership , directive leadership , authoritarian leadership , paternalistic leadership , and servant leadership theory . Each leadership theory promotes a particular approach to running organizations, from involving employees fully in decisions to handing down directives. By contrast, the contingency theory of leadership argues that rather than adapting their style to the organization, leaders should fill roles based on how well they “match” the situation. Let’s take a closer look at the contingency theory of leadership .

What Is the Contingency Theory of Leadership ?

The contingency theory of leadership , which emerged from numerous scholars in the 1960s, is rooted in the belief that earlier management theories had neglected the influence of situational factors, or contingencies, on organizations. Examples of contingencies include the state of the economy, the availability of trained labor, the organization’s culture, government policies and laws, the effects of climate change, and other factors. In a 1995 paper , Roya Ayman, Martin M. Chemers, and Fred Fiedler write that two main factors contribute to effective leadership: (1) attributes of the leader and (2) the degree to which the situation gives the leader power, control, and influence.

Claim your FREE copy: Real Leaders Negotiate

If you aspire to be a great leader, not just a boss, start here: Download our FREE Special Report, Real Leaders Negotiate: Understanding the Difference between Leadership and Management , from Harvard Law School.

In particular, the contingency theory of leadership distinguishes between leaders who are task oriented vs. relationship oriented. Task-oriented leaders focus primarily on ensuring that the tasks needed to meet particular goals are completed well and on time. These leaders tend to have a more autocratic, authoritarian, or directive leadership style. They also tend to manage projects effectively, but they can stifle creativity and leave employees feeling uninspired. Relationship-oriented leaders, by contrast, focus on building strong, lasting relationships with their employees and prioritize a healthy work culture. These leaders tend to have highly motivated, engaged employees, but tasks may run late and over budget.

Rather than valuing one of these leadership styles over the other, the contingency theory of leadership asserts that leaders with different styles will succeed based on the level of control they have over the situation—known as situational control .

Situational control has three components, according to Ayman and colleagues:

- Leader-member relations: the amount of cohesiveness in the work team and the team’s support for the leader. “Leader-member relations is the most important aspect of the situation,” they write, “because if the leader lacks group support, energy is diverted to controlling the group rather than toward planning, problem-solving, and productivity.”

- Task structure: the clarity and certainty in tasks, goals, and procedures that allow leaders to confidently guide group activities. The more predictable and certain a task is, the greater the leader’s sense of situational control.

- Position power: the amount of administrative authority that an organization grants a leader. Like task structure, position power contributes to a leader’s perceived situational control.

Task-oriented leaders will be more successful in situations where they have high or low control, and leaders who are relationship oriented will be more successful in situations where they have moderate control, write Ayman and colleagues.

What Contingencies Matter?

In a chapter on the contingency theory of leadership in the Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice , Jay Lorsch posits that leaders’ personalities and style are shaped at a young age and difficult to change. As such, he argues, “the most important benefit of a modern contingency theory would be to enable individual leaders and those who select them to understand clearly what qualities leaders will need to succeed in different situations.” That is, leaders can be chosen to match the existing demands of the organization.

Lorsch notes several contingencies that affect the ideal type of leader for an organization:

- Followers’ expectations of their leaders , such as the degree to which leaders are expected to be involved in decisions and provide direction; their level of technical or professional competence; and the degree to which they bond with followers.

- Organizational complexity , including the size of the organization, which affects many factors, including the levers of power and influence available to leaders and the relative difficulty of conveying one’s message, competence, and charisma.

- International differences. Operating in a single location makes it easier for leaders to be known by their followers and to project their competence than operating in multiple, far-flung locations. Some leaders may excel at cross-cultural communication, while others will be challenged by it.

- The organization’s tasks. The work of organizations tends to range from routine and repetitive (such as manufacturing established products) to innovative and novel (such as launching untested products). When tasks are certain and straightforward, a more directive leadership style is more effective; when tasks are uncertain, a more participative leadership style would be more suitable.

In sum, the contingency theory of leadership emphasizes the value of ensuring the right “fit” among leaders, employees, and the organization as a whole, rather than assuming that leaders will be able to adapt their skills and tendencies to the demands of the situation.

What pros and cons do you see in the contingency theory of leadership when applied to the daily life of organizations?

Related Posts

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Leadership Styles: Uncovering Bias and Generating Mutual Gains

- Servant Leadership and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge

- How to Negotiate in Cross-Cultural Situations

- Counteracting Negotiation Biases Like Race and Gender in the Workplace

- The Trait Theory of Leadership

Click here to cancel reply.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Negotiation and Leadership

- Learn More about Negotiation and Leadership

NEGOTIATION MASTER CLASS

- Learn More about Harvard Negotiation Master Class

Negotiation Essentials Online

- Learn More about Negotiation Essentials Online

Beyond the Back Table: Working with People and Organizations to Get to Yes

- Download Program Guide: March 2024

- Register Online: March 2024

- Learn More about Beyond the Back Table

Select Your Free Special Report

- Negotiation and Leadership Fall 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Essentials Online (NEO) Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Beyond the Back Table Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation Master Class May 2024 Program Guide

- Negotiation and Leadership Spring 2024 Program Guide

- Make the Most of Online Negotiations

- Managing Multiparty Negotiations

- Getting the Deal Done

- Salary Negotiation: How to Negotiate Salary: Learn the Best Techniques to Help You Manage the Most Difficult Salary Negotiations and What You Need to Know When Asking for a Raise

- Overcoming Cultural Barriers in Negotiation: Cross Cultural Communication Techniques and Negotiation Skills From International Business and Diplomacy

Teaching Negotiation Resource Center

- Teaching Materials and Publications

Stay Connected to PON

Preparing for negotiation.

Understanding how to arrange the meeting space is a key aspect of preparing for negotiation. In this video, Professor Guhan Subramanian discusses a real world example of how seating arrangements can influence a negotiator’s success. This discussion was held at the 3 day executive education workshop for senior executives at the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School.

Guhan Subramanian is the Professor of Law and Business at the Harvard Law School and Professor of Business Law at the Harvard Business School.

Articles & Insights

- For Sellers, The Anchoring Effects of a Hidden Price Can Offer Advantages

- BATNA Examples—and What You Can Learn from Them

- Taylor Swift: Negotiation Mastermind?

- Power and Negotiation: Advice on First Offers

- The Good Cop, Bad Cop Negotiation Strategy

- The Importance of Negotiation in Business and Your Career

- Negotiation in Business: Starbucks and Kraft’s Coffee Conflict

- Negotiation Examples in Real Life: Buying a Home

- How to Negotiate a Business Deal

- Negotiations in the News: Lessons for Business Negotiators

- How to Maintain Your Power While Engaging in Conflict Resolution

- Conflict-Management Styles: Pitfalls and Best Practices

- Causes of Conflict: When Taboos Create Trouble

- Mediation and the Conflict Resolution Process

- Managing Expectations in Negotiations

- Negotiating Change During the Covid-19 Pandemic

- AI Negotiation in the News

- Crisis Communication Examples: What’s So Funny?

- Crisis Negotiation Skills: The Hostage Negotiator’s Drill

- Police Negotiation Techniques from the NYPD Crisis Negotiations Team

- Managing Difficult Employees, and Those Who Just Seem Difficult

- How to Deal with Difficult Customers

- Negotiating with Difficult Personalities and “Dark” Personality Traits

- Consensus-Building Techniques

- Ethics in Negotiations: How to Deal with Deception at the Bargaining Table

- Dealmaking and the Anchoring Effect in Negotiations

- Negotiating Skills: Learn How to Build Trust at the Negotiation Table

- How to Counter Offer Successfully With a Strong Rationale

- Negotiation Techniques: The First Offer Dilemma in Negotiations

- 5 Dealmaking Tips for Closing the Deal

- Alternative Dispute Resolution Examples: Restorative Justice

- Choose the Right Dispute Resolution Process

- Union Strikes and Dispute Resolution Strategies

- What Is an Umbrella Agreement?

- What is Dispute System Design?

- Top 10 International Business Negotiation Case Studies

- Hard Bargaining in Negotiation

- Prompting Peace Negotiations

- Political Negotiation: Negotiating with Bureaucrats

- Top International Negotiation Examples: The East China Sea Dispute

- What Makes a Good Mediator?

- Why is Negotiation Important: Mediation in Transactional Negotiations

- The Mediation Process and Dispute Resolution

- Negotiations and Logrolling: Discover Opportunities to Generate Mutual Gains

- How Mediation Can Help Resolve Pro Sports Disputes

- 5 Types of Negotiation Skills

- 5 Tips for Improving Your Negotiation Skills

- 10 Negotiation Failures

- When a Job Offer is “Nonnegotiable”

- In Negotiation, How Much Do Personality and Other Individual Differences Matter?

- Ethics and Negotiation: 5 Principles of Negotiation to Boost Your Bargaining Skills in Business Situations

- 10 Negotiation Training Skills Every Organization Needs

- Trust in Negotiation: Does Gender Matter?

- Use a Negotiation Preparation Worksheet for Continuous Improvement

- Collaborative Negotiation Examples: Tenants and Landlords

- Renegotiate Salary to Your Advantage

- How to Counter a Job Offer: Avoid Common Mistakes

- Salary Negotiation: How to Ask for a Higher Salary

- How to Ask for a Salary Increase

- Setting Standards in Negotiations

- Asynchronous Learning: Negotiation Exercises to Keep Students Engaged Outside the Classroom

- Planning for Cyber Defense of Critical Urban Infrastructure

- New Simulation: Negotiating a Management Crisis

- New Great Negotiator Case and Video: Christiana Figueres, former UNFCCC Executive Secretary

- Download Your Next Mediation Video

- How to Win at Win-Win Negotiation

- Labor Negotiation Strategies

- How to Create Win-Win Situations

- For NFL Players, a Win-Win Negotiation Contract Only in Retrospect?

- Win-Lose Negotiation Examples

PON Publications

- Negotiation Data Repository (NDR)

- New Frontiers, New Roleplays: Next Generation Teaching and Training

- Negotiating Transboundary Water Agreements

- Learning from Practice to Teach for Practice—Reflections From a Novel Training Series for International Climate Negotiators

- Insights From PON’s Great Negotiators and the American Secretaries of State Program

- Gender and Privilege in Negotiation

Remember Me This setting should only be used on your home or work computer.

Lost your password? Create a new password of your choice.

Copyright © 2024 Negotiation Daily. All rights reserved.

Advisory boards aren’t only for executives. Join the LogRocket Content Advisory Board today →

- Product Management

- Solve User-Reported Issues

- Find Issues Faster

- Optimize Conversion and Adoption

Fiedler’s contingency theory of leadership: Definition, examples

If you’re seeking the optimal way to guide your team and boost employee productivity, you might find yourself overwhelmed by the multitude of theories on the best leadership style. It can be challenging to discern which approach is truly the most effective. However, contingency theory proposes that there isn’t a single “best” leadership style — rather, the ideal approach depends on the specific situation.

Contingency theory prompts managers to consider various aspects of their employees and the current circumstances. Equipped with this understanding, you can modify your leadership style to elicit the most positive response from their team members.

Contingency theory definition

The core premise of contingency theory is that there’s no universally correct way to lead a team or make decisions. Instead, it advocates for a strategy that’s flexible and adaptable to the situation at hand.

Leaders who embrace contingency theory adjust their leadership style based on factors such as interpersonal relationships within the workplace or feedback from employees.

Origins of contingency theory

Contingency theory was first introduced by Fred Fiedler , a prominent researcher in organizational psychology during the 20th century. Rather than categorizing leaders as either bad or good, Fiedler’s contingency theory emphasized aligning necessary leadership traits with specific challenges.

Fiedler identified leaders as either relationship-oriented or task-oriented, asserting that success in leadership depended on how favorable the situation was. In essence, contingency theory suggests that numerous variables can alter the requirements of a scenario. Consequently, leaders need to adapt their style or delegate tasks to individuals with suitable skill sets to navigate these challenges effectively.

Advantages of adopting contingency theory

Contingency theory presents several advantages for managers. Given that product managers often collaborate with cross-functional teams , it’s crucial to understand how to effectively respond to a range of personalities and employee needs. Contingency theory can introduce the necessary level of adaptability for diverse situations.

Some other benefits include:

- Self-reflection — Contingency theory fosters self-reflection in leadership styles

- Situation focus — It tends to focus on the situation rather than the individual leader

- Leadership determination — It offers a straightforward way to determine who might be the best leader for a given situation

- Team awareness — It promotes awareness of team members and the situation

- Guidance — It provides clear guidance on what factors to consider when choosing a leadership style

4 types of contingency theory

Over time, four distinct contingency theories have been developed. While they all adhere to basic principles, each one exhibits slight variations.

Fiedler model

The Fiedler model is the original contingency theory. To apply it, a leader must possess situational awareness and understand their own leadership style.

The Fiedler model uses a scale known as the Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) as a guide to evaluate a coworker they find most challenging to work with:

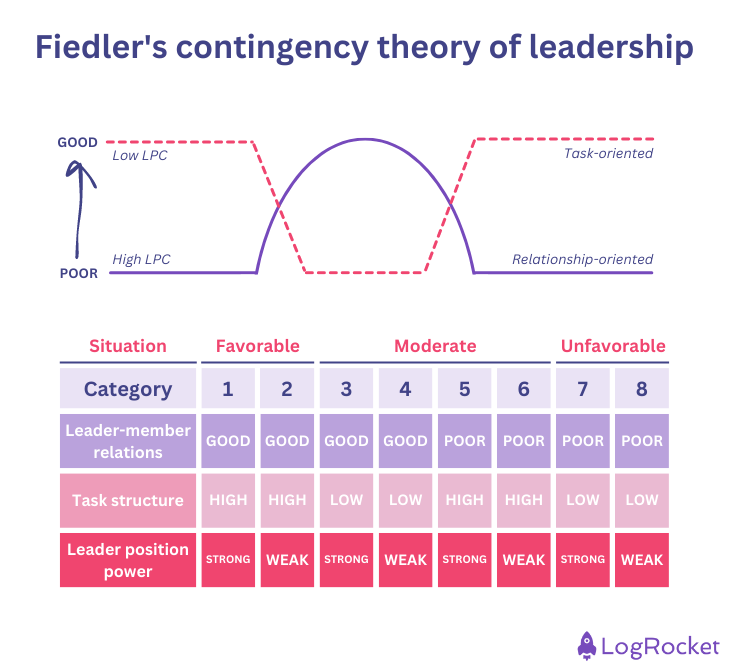

A high score indicates that the leader is an HPC leader with a strong tendency toward being relationship-oriented — ideal for situations like conflict management and morale building. Conversely, a low score suggests that the leader is an LPC leader who is more task-oriented. These leaders are better suited for project management and logistical tasks.

Once you’ve identified your leadership style, it’s time to assess situational favorableness. This is determined by three variables that significantly influence a product manager’s ability to lead effectively:

- Leader-member relations — The extent to which a manager is liked by their team

- Task structure — The degree of organization of a task or process and whether it’s understood by the team

- Leader-position power — The amount of formal authority a manager has over their work

These characteristics determine situational favorableness. More favorable situations require task-oriented leaders, while less favorable ones benefit from relationship-oriented leaders.

Situational leadership model

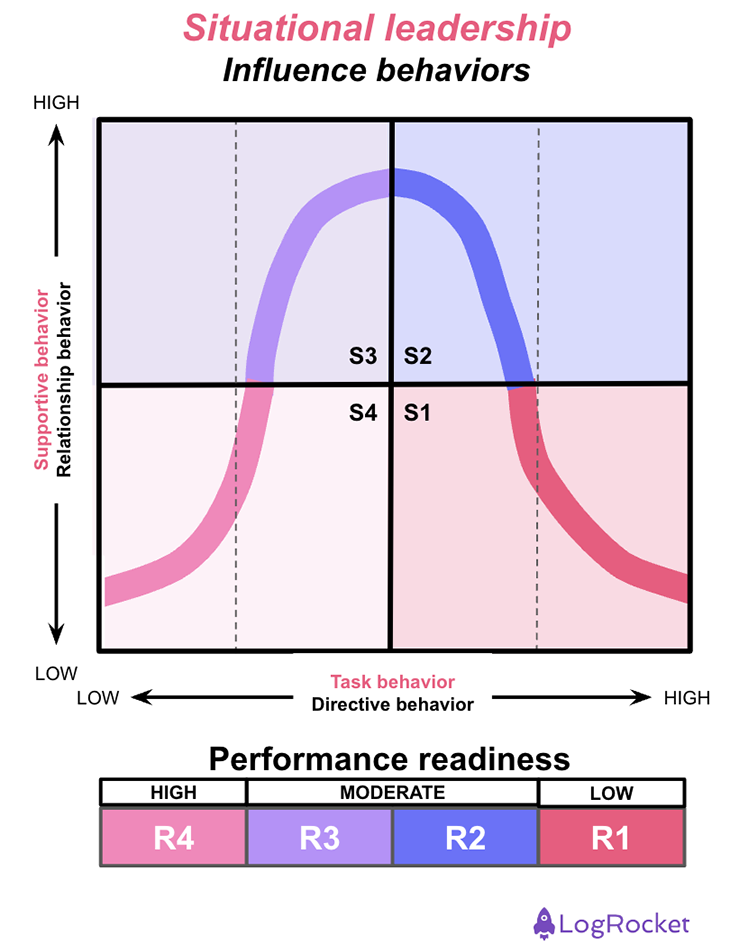

Unlike Fiedler’s model, the situational leadership model allows leaders greater flexibility in adapting their approach based on circumstances. It focuses on the team’s maturity before determining an appropriate leadership style:

Maturity often refers to aspects such as team members’ experience, autonomy, willingness to take responsibility, confidence, and capability. This model outlines four leadership styles:

- Delegating style — Ideal for experienced and capable team members; this style involves assigning tasks or leading projects

- Participating style — Used when building confidence in team members; this style often involves one-on-one mentoring sessions where ideas are shared and collaboration occurs

- Selling style — Designed for team members who lack motivation or initiative; this style aims at persuading team members to complete their tasks

- Telling style — Beneficial for inexperienced team members; this approach involves giving directions and closely supervising them until they mature

Path-goal model

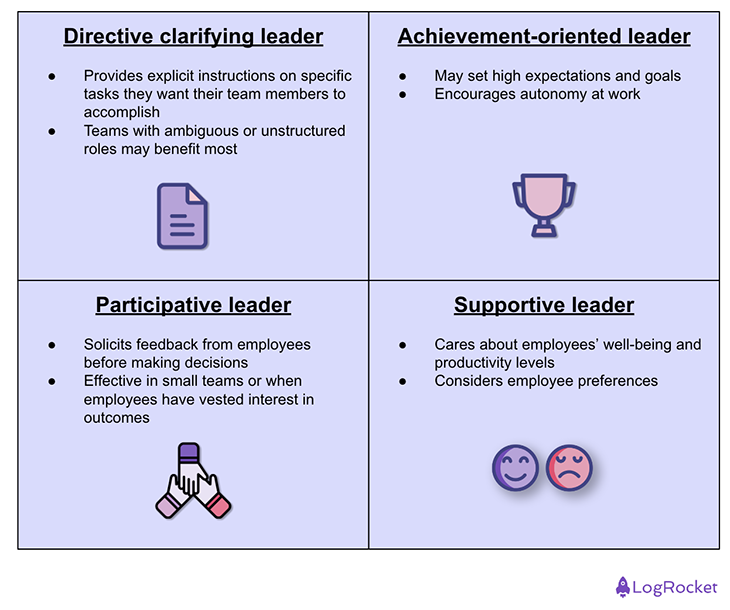

The Path-Goal model centers around employees and their individual goals. Leaders assist their team members in developing daily, weekly, or career goals and then collaborate with them to achieve those objectives. The aim of the Path-Goal model is to enhance employee motivation and productivity by fostering job satisfaction:

This approach requires leaders to be highly adaptable since they need to tailor their leadership style according to each individual’s needs. Leaders also need awareness of their employees’ skill sets and what areas may require coaching for success.

Over 200k developers and product managers use LogRocket to create better digital experiences

There are four different leadership styles within the Path-Goal model:

- Directive clarifying leader — This type of leader provides explicit instructions on specific tasks they want their team members to accomplish. Teams with ambiguous or unstructured roles may benefit most from this type of leadership

- Achievement-oriented leader — Leaders who manage confident high-achievers may set high expectations and goals while encouraging autonomy at work

- Participative leader — These leaders solicit feedback from employees before making decisions — typically effective in small teams or when employees have vested interest in outcomes

- Supportive leader — Alongside productivity concerns, supportive leaders care about employees’ well-being and mental health — taking into account individual employee preferences

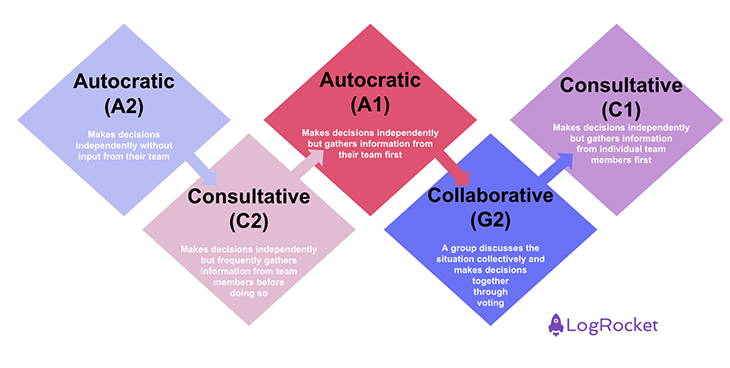

Decision-making model

The decision-making model focuses on how decisions are made, which ultimately determines the relationship between a leader and their team members:

This model outlines five leadership styles:

- Autocratic (A1) — The leader makes decisions independently without input from their team

- Autocratic (A2) — The leader makes decisions independently but gathers information from their team first

- Consultative (C1) — The leader makes decisions independently but gathers information from individual team members first

- Consultative (C2) — The leader makes decisions independently but frequently gathers information from team members before doing so

- Collaborative (G2) — A group discusses the situation collectively and makes decisions together through voting

How to apply the contingency theory of management

To implement the contingency theory effectively, a certain level of self-awareness and understanding of your team members is crucial. Here are some steps to follow when applying contingency theory as a product manager:

- Identify your leadership style — Use the Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) scale test to determine whether you’re more relationship-oriented or task-oriented. It’s also beneficial to observe how you naturally react in different work situations, especially how you adapt based on the task at hand, the team members involved, and other variables

- Seek feedback from your team — A potential drawback of contingency theory is that your perspective might be biased, leading you to overlook signs of an unfavorable situation. To counter this, ask your team members for their opinions on task clarity and their trust in management

- Improve situational favorableness — Enhance leader-member relations through open and transparent communication. Make tasks and processes clearer and more structured, and seek opportunities to increase your authority, such as pursuing higher-level positions

- Understand your employees — Knowing what your employees want to achieve in their careers is essential. As a product manager, being aware of individual employee goals and skill sets can help ensure their success

- Assess your situation regularly — Numerous factors can impact your workplace, including customer demand, changes in government policies, and other unpredictable challenges. Maintaining awareness of both external factors and the internal work environment can help you decide which leadership style will best promote productivity and boost morale among employees

What does contingency theory look like in practice?

Let’s consider a practical example of how contingency theory might be applied.

Suppose you’ve just been hired as a product manager at an established company. According to Fiedler’s model, leader-member relations would initially be poor because you’re new and haven’t yet built trust with the team. The task structure is high due to the company’s established nature, but your leader-position power is low as a junior manager.

In this case, adopting a relationship-oriented leadership style could help improve relations with your new colleagues while also paving the way for advancement within the company.

What are some limitations of contingency theory?

One critique of Fiedler’s model is that it suggests a leader who excels in one situation may struggle in another. This implies that changing leaders may be necessary — an option that isn’t always feasible or desirable. It doesn’t account for the possibility that managers can adapt their leadership style according to situational needs.

To address this issue, consider exploring other types of contingency theories to identify a leadership style that suits the specific circumstances you encounter at work.

While there are various types of contingency theories with differing approaches to team management, they all share common elements. Your leadership style will need to adapt based on the task at hand, employee behaviors, and the level of authority you hold in your position.

Being a great leader requires flexibility in your leadership style. Adapting to changing circumstances can help propel projects forward and keep employees motivated.

LogRocket generates product insights that lead to meaningful action

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- #career development

- #collaboration and communication

Stop guessing about your digital experience with LogRocket

Recent posts:.

Leader Spotlight: Making magic with the right SDLC model, with Trevor Riley

Trevor Riley talks about how adaptation is crucial to long-term success and how you need to adapt your software development life cycle.

Leader Spotlight: Enabling a cultural mind shift, with Nancy Wang

Nancy Wang shares how she’s spearheaded a “cultural mind shift” away from an IT plan-build-run organization to a product-centric one.

A guide to decentralized decision-making

Decentralized decision-making is the process where stakeholders distribute strategic decisions within an organization to lower-level teams.

Cumulative flow diagrams: Unraveling Kanban metrics

A cumulative flow diagram is an advanced analytic tool that represents the stability of your workflow over time.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

It depends. Understanding the contingency theory of leadership

Lead with confidence and authenticity

Develop your leadership and strategic management skills with the help of an expert Coach.

Jump to section

What is the contingency theory of leadership?

What does the contingency theory of leadership focus on, why is contingency theory important in leadership, 2 examples of contingency leadership theory in action, looking at the models of the contingency theory at work, how to apply the contingency theory of leadership at work.

When asked what it means to be a "good leader," what comes to mind? Do you think of certain skills or traits, or do you picture a specific person or a leader from your own life?

The truth is, the answer varies. Good leadership can’t be defined in a single person or a laundry list of personality traits. But we can, however, identify key skills and traits that great leaders share. We know that people simply aren’t born leaders. After all, skills, behaviors, and mindsets can grow and develop with the right support.

At BetterUp, we’ve studied leadership . We've studied how people have invested in developing much-needed leadership skills. Leadership skills are critical whether employees are in a managerial position or not. A person's ability to understand their own strengths, weaknesses, and style of leadership is critical to being a good leader.

We know that the contingency theory of leadership follows this school of thought. The contingency theory of leadership tells us that effective leadership depends on the situation. In simple terms, a leader could be highly effective in one situation and ineffective in another.

It might be true that leaders respond differently in certain situations. But this theory minimizes people’s ability to develop new skills and behaviors. People are capable of building new skills to adapt to new situations with the right support and resources. It might take some muscle in certain areas more than others. But human growth and transformation are more than possible.

Good leadership isn’t just about a leader’s skills. It’s about a leader’s awareness and adaptability in a specific situation. It’s more fruitful to understand our different leadership styles and build self-awareness . In other words, it’s critical that we build mental fitness to be able to recognize where we can improve.

And science tells us that when we invest in developing our leadership skills, our teams benefit, too. Our research shows that leaders who balance optimistic action with thoughtful pragmatism have higher-performing teams . The results? Teams show increased agility, team engagement, innovation, performance, and resilience.

If you’re looking for new ways to connect with your team members and grow in your career, keep reading. You'll learn more about the contingency theory of leadership and how it can help you approach leadership in a whole new light.

The contingency theory of leadership states that effective leadership is contingent upon the situation at hand. Essentially, it depends on whether an individual's leadership style befits the situation. According to this theory, someone can be an effective leader in one circumstance and an ineffective leader in another.

This theory ignores the false dichotomy that someone is either a "good" or "bad" leader. Instead, it focuses on matching the right leadership traits to the situation.

This theory of leadership accommodates the reality that success in an undertaking is often a combination of the attributes of the leader and the attributes of the challenge. "Good leadership" is contingent upon how one responds to the situation.

The very first contingency theory was developed by Austrian psychologist Fred E. Fiedler in the 1960s . Fiedler's model continues to be one of the leading contingency leadership theories.

From Fiedler's research, more modes of thinking were born:

- The Situational Leadership® model, developed by Paul Hersey and Kenneth Blanchard in 1982

- The Path-Goal model, developed by Martin Evans and Robert House in 1971

- The Decision-Making model, developed by Victor Vroom and Philip Yetton in 1973

All four models present different ways to approach and apply the contingency theory of leadership. We'll dig deeper into each later in this guide. First, let's unpack the approach as a whole.

Firstly, the contingency theory of leadership focuses on leadership styles . To apply this theory or any of its models, leaders must be aware of their own leadership style as well as their strengths and weaknesses. This requires honesty, self-reflection, and vulnerability for a person to identify how they’re showing up as a leader.

Acknowledging these things can be uncomfortable but can make someone a better leader in the long run.

We’ll get into leadership styles — and how they align to each of the four models — later in this article. But some of the leadership styles include:

- Delegating style . Leaders who easily delegate goals, projects, and tasks to team members

- Participating style . Leaders who share ideas to motivate their team members, gain buy-in, and help them build confidence and autonomy

- Selling style . Leaders who "sell" their instructions and tasks to team members who may need extra motivation

- Telling style . Leaders who delegate and supervise their team members who may lack experience or confidence in their roles

- Supportive style . Leaders who consider their team members' personal preferences and treat well-being as important as productivity

- Participative style . Leaders who work alongside their team and ask for input or feedback before making decisions

- Directive-clarifying style . Leaders who give explicit tasks and instructions

- Achievement-oriented style. Leaders who set high expectations and goals for their team and encourage autonomy and independence

- Autocratic style . Leaders who make decisions independently

- Consultative style . Leaders who consult their team members but ultimately make decisions independently

- Collaborative style . Leaders who make decisions democratically

This theory focuses on the circumstances surrounding a situation or a challenge. Different models use different factors to predict what kind of leadership style would be most effective.

If anything, this approach to leadership surfaces how many variables are at play in any given situation in the workplace. Only by being aware of and understanding these factors can someone be an effective leader.

Those include (but aren't limited to):

- Work schedules

- Work styles and paces

- Task structures

- Team structures

- Professional and personal goals

- Feedback preferences (for both giving and receiving)

- Leaders' and employees' maturity levels and personality types

- Relationships between and among employees and leaders

- Employee morale

- Company hierarchy and power levels

- Company performance

- Company policies and behavioral standards

(Note that you'll see some of these factors pop up in the models we discuss below.)

Consider how a football quarterback 'reads the field' before he calls a route for his offensive line. He likely has to change the play from down to down, especially as the opposing team changes their defensive line.

So, too, do factors vary within and between every employee and their employers. With so many moving parts within an organization, it's clear why a "one size fits all" approach to leadership simply can't work.

Let’s say you manage a team of four people. You’ve tasked your project management expert to take the lead on an upcoming cross-functional campaign. However, as the campaign progresses, you realize the work requires a different skill set. Many of the deliverables are focused on creating copy, design, and other sorts of creative work. Your project management person has been going back to the content marketing manager for certain asks. Yet the content marketing manager wasn’t originally a part of the project. You decide that your content marketing manager would be better equipped to help the team reach success. So, you swap out your project management expert with your content marketing lead.

Contingency theory isn't one that we at BetterUp necessarily believe in. We know that people are capable of learning, growing, and developing leadership skills .

So, it's important to understand that this theory is one that some leaders may believe in. But in reality, it's even more important to understand that people can grow and change.

Essentially, it’s critical that your leaders understand they can build skills to succeed in situations where they might feel especially challenged. We all have a sense of our strengths and weaknesses .

The contingency theory of leadership can help bring awareness to those areas of opportunity for your leaders. However, it’s important your leaders understand that just because they’re not seeing the desired outcome in certain situations doesn’t mean they can’t build the skills to succeed.

Approaching leadership with this lens allows more individuals to explore leadership in their careers and better understand themselves as well as in what situations they may be effective leaders.

Most believe that leadership exists on a spectrum, with poor leaders and great leaders. Contingency theory debunks this thought process and instead presents the idea that for every situation or challenge, there is a best-fit leadership style.

For those employees and individuals who desire to improve their leadership skills, the contingency leadership theory argues that they must look within, work to understand themselves and develop their strengths, and then approach challenges objectively to determine what (and who) can lead.

At BetterUp, we use the practice of Inner Work® . And according to our research, looking inward makes you a better leader. When leaders practice Inner Work® , teams are more engaged, more productive, and gain more clarity. We also see better work-life balance and reduced burnout, which helps support overall employee well-being.

Let's review a couple of examples that illustrate the contingency theory of leadership and its models.

Example #1: Adapting to feedback preferences

Jason manages a team of writers for his company's publication. Every Friday, he holds a meeting for his writers to share their current assignments and receive feedback from their colleagues. Jason has found that this helps his team hone their writing, editing, and feedback-giving skills. He also employs the Supportive Leader style of the Path-Goal model.

A new writer joins Jason's team and immediately expresses discomfort about these Friday feedback sessions. They don't enjoy public speaking and dislike the public nature of the feedback. They prefer to receive edits via Google Docs.

Does this make Jason a bad manager? No. Yet, the contingency theory of leadership states that to remain a good and effective leader, he must adapt to his new employee's preferred feedback method. Jason can still ask his new team member to join the meeting but not feel pressured to share their work.

Example #2: Delegating a leadership responsibility to another

Four years ago, Abby founded her software company alongside two former colleagues, both of whom enjoy sales, networking, and attending and speaking at events.

In other words, her two partners are the "face of the company," while Abby enjoys staying out of the spotlight and working with her team of developers to build and improve the company's product. Abby has a Delegating Style of leadership according to the situational leadership model.

One day, Abby's cofounder surfaces an opportunity to lead a keynote presentation at a top conference for their company's industry. Unfortunately, even thinking about presenting in front of many people gives Abby anxiety.

Does Abby become a lousy leader if she turns down the speaking opportunity? No. Leaders aren't required to be natural extroverts or enjoy public speaking to lead.

Because she's cultivated a culture of delegation and trust among her team, Abby could work with one of her lead developers—someone who is also experienced in the topic but more comfortable with public speaking —to present the keynote speech instead.

There are many ways to put the contingency leadership theory into action. This section covers four distinct perspectives on contingent leadership. Each model has its defined leadership styles, but there's plenty of overlap between the styles.

Note: These models aren't designed to "diagnose" leadership styles; they're intended to identify where leaders should work with their coaches to identify how (and where) to work on certain capabilities.

Using these leadership styles as references, leaders can identify and be aware of the behaviors and mindsets they're using with their teams and where they can improve.

1. Fiedler’s contingency model

The first of the contingency leadership models were developed in the 1960s by Austrian psychologist and professor Fred Fiedler. Through years of research into the personalities and characteristics of leaders, Fiedler’s theory was that life experiences shape leadership styles .

As a result, according to this model, leadership styles tend to be fixed and near-impossible to change.

Fiedler’s contingency theory is quite simple: By comparing their natural (and fixed) leadership style to three situational factors, leaders can determine if they can be effective leaders.

First, to determine their leadership style, individuals can use the Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) scale to describe a coworker with whom they least enjoy working.

Individuals with high scores (typically ~70 or higher) are considered high LPC leaders and tend to be relationship-oriented leaders. Those with lower scores (typically ~50 or below) are considered low LPC leaders and are more likely to be task-oriented leaders.

If leaders score between 50 and 70, they can be considered both relationship- and task-oriented and need to approach situations with more subjectivity and self-reflection . (The other three models can help with this.)

As you can imagine, high LPC leaders can combat interpersonal conflict , boost team synergy and morale, and build relationships among their teams. Low LPC leaders excel at project management, organizational skills, and logistical team management .

This isn't to say that high LPC and low LPC leaders don't share some skills, but Fiedler's LPC score presents a helpful baseline for individuals wanting to better understand their different leadership styles and combat unfavorable situations.

To implement Fiedler’s model, leaders must then evaluate the situation at hand to determine how well their leadership style befits the challenge:

- Leader-member relations refer to the strength of a leader’s relationship with their team and employees. Relationship strength can be determined by the level of trust and respect shared between a team and its leader. The stronger the leader-member relations, the more favorable the situation

- Task structure refers to how clearly defined and organized a project's tasks are. Well-structured tasks have high task structure and vice versa. The higher the task structure, the more favorable the situation

- Leader position power refers to the level of authority a leader has over their team. The higher up on a company's hierarchy or organizational structure , the more power a leader has. The higher the position of power, the more favorable the situation

The following chart developed by CEO Carl Lindberg helps compare leadership styles with these three situational variables:

"The novelty with [this model] was that Fiedler stated that a leader could be effective in one situation and not in another," Lindberg shared. "A good leader is not necessarily successful when heading all types of organizations in all situations."

Who does Fiedler's model of contingency leadership theory benefit most?

While the Fiedler model is the flagship model of the contingency theory of leadership, it isn't a fit for every leader. Let's look at a few pros and cons of the theory:

2. Situational Leadership® model

Also called the "Hersey-Blanchard model," the Situational Leadership model states that individuals should adapt their leadership style to the situation at hand and the employees involved.

The model focuses on one workplace factor: the maturity level of leaders and their employees.

Experienced, autonomous employees who can make decisions independently are high maturity. Capable employees that struggle with confidence or following through are moderate maturity. Enthusiastic, receptive employees that lack basic leadership or experience are low maturity.

The Situational Leadership model presents four different leadership types for all maturity levels:

- The Delegating Style of leadership is best suited for leaders who delegate goals, projects, and tasks to high-maturity employees. This leadership style also requires a healthy amount of trust between leaders and their teams . (Consider the low LPC leader in the Fiedler model.)

- The Participating Style of leadership involves a give-and-take between leaders and their teams. Leaders share ideas to motivate their moderate-maturity team members and help them build the confidence to move into a high-maturity mindset.

- The Selling Style of leadership refers to when leaders must "sell" their instructions to moderate-maturity employees. This type of leader often surfaces when employees lack motivation or aren't self-starters.

- The Telling Style of leadership works best for teams of low-maturity employees who lack experience or foresight to determine their projects and tasks. Leaders in this style must delegate and supervise their team members, at least until they move up in maturity level.

3. Path-Goal model

The Path-Goal model says that effective leaders help their employees reach their goals. Simple enough, right?

By working with employees to determine their daily, weekly, or career goals, leaders can map the path to completing those goals and adapt their coaching leadership style to coach each employee to achieve them.

The contingency leadership theory comes into play as individuals' leadership styles will vary based on each goal path. This requires flexibility and self-awareness on the part of the leader. In other words, the leader must be aware of their employees’ goals. They must also be aware of the skills employees have — and what they must coach their employees on to reach their goals.

The Path-Goal theory emphasizes employee morale, employee engagement , satisfaction, and productivity as factors to help leaders determine what style is best for their team. This model has four primary leadership styles:

- The Supportive Leader takes into account their employees' personal preferences and treats their well-being as important as their productivity. Leaders in stressful work environments may implement this approach.

- The Participative Leader works alongside their team and often asks for input or feedback before making decisions. Leaders at startups, in small teams, or whose team members are personally invested in the outcome may implement this approach.

- The Directive Clarifying Leader gives explicit tasks and explains how tasks should be done. Leaders of teams with ambiguous roles or unstructured tasks may implement this approach.

- The Achievement - Oriented Leader sets high expectations and goals for their team and often encourages autonomy and independence at work. Leaders who manage distributed leaders or high-achieving teams may implement this approach.

4. Decision-Making model

Also known as the " Vroom-Yetton contingency model ," the Decision-Making model uses decision-making and leader-member relations to determine effective leadership.

This model presents five leadership styles:

- The Autocratic (A1) leader makes decisions independently and doesn't consult others before doing so.

- The Autocratic (A2) leader makes decisions independently but passively consults with team members to gather information before doing so.

- The Consultative (C1) leader makes decisions independently but consults with team members individually to understand everyone’s opinions before doing so.

- The Consultative (C2) leader makes decisions independently but consults with team members often, perhaps through a group discussion to gather suggestions, before doing so.

- The Collaborative (G2) leader makes decisions through a democratic leadership process, often organizing a group discussion to discuss suggestions before voting for the final decision.

The contingency theory of leadership can help bring levels of awareness and education to how leadership styles manifest in the workplace. However, it's not necessarily a model that will unlock the full potential of your workforce.

At BetterUp, we've studied how leaders can grow and develop their skills (especially after they've reflected on their own areas of opportunity). Here are five ways you can help develop inclusive leaders and future-minded leaders who will have an impact.

1. Identify where you see the contingency theory of leadership showing up in your own behaviors and mindset

Pay attention to how you react to specific challenges or situations at work. Take stock of your reactions—internally and externally—and how you adapt based on whom you're working with, what you're working on, and other variables in the situation.

2. Figure out what leadership style you're leveraging for specific situations

Using the models above, determine your leadership style—or styles, as different situations may surface different responses.

Consider doing this early in your leadership role instead of waiting until a situation or challenge arises, and reevaluate your style regularly as you gain more experience, change your team or employer, or even invest in coaching.

3. Identify your ideal outcome. What skills do you need to achieve that outcome?

What kind of leader do you aspire to be? What outcomes do you hope to achieve or even expect from your team? If your team is struggling to achieve those outcomes, it may be a reflection of how effective you are as a leader.

Thankfully, leadership is all about adapting and growing into the skills you may be lacking to lead effectively. A coach can help you do this.

4. Work with your coach to develop and grow

Learning the skills needed to adapt and improve your leadership style can be tough, and you don't have to do it alone. Coaching is a surefire way to shape your leadership skills and work towards the ideal outcomes you identified above.

A leadership coach can help you become more self-aware and acknowledge the inherent complexity of leadership.

5. Commit to growing and learning

As we've discussed in this article, there's no single right approach or right set of leadership characteristics for every workplace circumstance. Instead, adopt a growth mindset and allow yourself to learn from and thrive in difficult situations.

Commit to developing skills that make you an adaptable, open-minded leader—the best kind of leader there is.

Start to develop great leaders in your organization

So, what does it mean to be a good leader?

In today's fast-paced world, being flexible and open to change is a prerequisite for success—especially for those in leadership positions. Good leadership isn't a one-size-fits-all approach—it's about taking the time to understand yourself, your team, and your workplace to determine how to be the best leader.

With BetterUp, you can invest in developing leaders that will help unlock your workforce's full potential. Help your people build the skills they need to become the leaders they can be.

Madeline Miles

Madeline is a writer, communicator, and storyteller who is passionate about using words to help drive positive change. She holds a bachelor's in English Creative Writing and Communication Studies and lives in Denver, Colorado. In her spare time, she's usually somewhere outside (preferably in the mountains) — and enjoys poetry and fiction.

Are people born leaders? Debunking the trait theory of leadership

Refine your approach with these 7 leadership theories, how to be an empathetic leader in a time of uncertainty, how leadership coaching helps leaders get (and keep) an edge, the most critical skills for leaders are fundamentally human, types of leadership styles to maximize your team's potential, 7 key leadership behaviors you must have, what is a leader, what do they do, and how do you become one, 5 top companies share their best leadership development practices, similar articles, what is a disc assessment and how can it help your team, situational leadership®: what it is and how to build it, need to move faster and smarter level up with distributed leadership, democratic leadership style: how to make it work as a team, social learning theory: bandura’s hypothesis (+ examples), how to help leaders play up their unique superpowers, learn what participative leadership is and how to practice it, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice

A Contingency Theory of Leadership

- Format: Print

About The Author

Jay W. Lorsch

More from the author.

- Faculty Research

How the Harvard Business School Changed the Way We View Organizations

A nonprofit board in transition at farrington nature linc.

- June 2017 (Revised October 2017)

Uber in 2017: One Bumpy Ride

- How the Harvard Business School Changed the Way We View Organizations By: Jay W. Lorsch

- A Nonprofit Board in Transition at Farrington Nature Linc By: Jay Lorsch and Emily Irving

- Uber in 2017: One Bumpy Ride By: Suraj Srinivasan, Jay W. Lorsch and Quinn Pitcher

Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance pp 2463–2469 Cite as

Contingency Theory of Leadership

- Manuel Villoria 2

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2023

20 Accesses

Contextual; Democratic and authoritarian leadership; Potestas and auctoritas in leadership; Situational

Introduction: Contingency Theory

The main purpose of this article is to summarize the main ideas and contributions of the contingency theory of leadership (CTL) and to show its usefulness for the public sector. To do that, we are going to adapt it to the special characteristics and traits of public management considered as a design science (Barzelay and Thompson 2010 ).

The most important theoretical backgrounds of the CTL are the behavioral school and McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y. According to McGregor’s thesis ( 1960 ), leadership strategies are influenced by a leader’s assumptions about human nature. A leader holding Theory X assumptions would prefer an autocratic style, whereas one holding Theory Y assumptions would prefer a more participative style. Anyway, the best style of leadership was the participatory. Later on, Blake and Mouton ( 1964 ) created the “managerial...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Adair J (1973) Action-centred leadership. McGraw-Hill, New York

Google Scholar

Barzelay M, Thompson F (2010) Back to the future: making public administration a design science. Public Adm Rev 70(1):295–297

Article Google Scholar

Benn SI, Gaus GF (1983) Public and private in social life. Sts Martin’s, New York

Blake R, Mouton J (1964) The managerial grid: the key to leadership excellence. Gulf, Houston

Cook BJ (1998) Politics, political leadership and public management. Public Adm Rev 58(3):225–231

Dahl R, Lindblom C (1976) Politics economics and welfare. University of Chicago Press, Chicago/London

Fiedler FE (1967) A theory of leadership effectiveness. Mc Graw Hill, New York

Heifetz RA (1994) Leadership without easy answers. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Book Google Scholar

Hersey P, Blanchard K (1977) Management of organizational behavior: utilizing human resources. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Lindell M, Rosenqvist G (1992) Is there a third management style? Finn J Bus Econ 3:171–198

McGregor D (1960) The human side of enterprise. McGrawHill, New York

Perry JL (1993) “Public management theory”: what is it? What should it be? In: Bozeman B (ed) Public management. Jossey Bass, San Francisco

Rainey H (1997) Understanding and managing public organizations. Jossey Bass, San Francisco

Selznick P (1949) TVA and the grass roots. University of California Press, Berkeley

Tannenbaum R, Schmidt W (1958) How to choose a leadership pattern. Har Bus Rev 36(2):95–101

Terry LD (1995) Leadership of public bureaucracies. Sage, London

Van Wart M (2003) Public sector leadership theory: an assessment. Public Adm Rev 63(2):214–228

Vroom V, Yetton PW (1967) Leadership and decision making. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh

Weber M (1984) Economía y sociedad. Fondo de Cultura Económica, México

Wilson JQ (1989) Bureaucracy: what government agencies do and why they do it. Basic Books, New York

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University King Juan Carlos, Móstoles, Madrid, Spain

Manuel Villoria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Manuel Villoria .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL, USA

Ali Farazmand

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Villoria, M. (2022). Contingency Theory of Leadership. In: Farazmand, A. (eds) Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66252-3_2227

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66252-3_2227

Published : 06 April 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-66251-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-66252-3

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Leadership Styles Portal

- Leadership Styles Articles

- Charismatic Leadership

- Democratic Leadership

- Laissez-Faire Leadership

- Transactional Leadership

- Leadership Theories

- Leadership Advice

- Communication

- About the author

Learn about Resonant Leadership, Emotional Intelligence the six leadership styles and how to practically switch between the styles to become a more effective , flexible and impactful leader!

Contingency Theory of Leadership explained by a CEO

In my leadership role as a CEO, I must use a contingency theory of leadership due to the fast-changing, complex environment of today. Contingency leadership theories allow for different leadership tools for various contingencies or situations, ranging from working with a new inexperienced team, handling change, coaching when appropriate, and being more commanding when required. To be a successful leader today, you simply must use a contingency leadership theory, as previous theories are inadequate for the job.

What is the contingency theory of leadership?

The contingency theory of leadership stipulates that leaders should maximize their impact using situationally appropriate leadership styles and behaviors, depending on circumstances, people, environment, etc.

This article explains the contingency theory of leadership, its history, examples of contingency theories, and why you should start using a contingency approach in your leadership. I also provide a few examples of how I use a contingency leadership approach in my job as a CEO in real life. You can read about this and many other leadership theories in our Leadership Origins E-book .

Contingency Theory of Leadership: Background, History, Evolution

The different models of contingency theory of leadership, how is contingency theory used in leadership, contingency theory of leadership advantages and disadvantages, contingency theory of leadership example situations, contingency theory example: commanding leadership, contingency theory example: affiliative and democratic leadership, contingency theory example: visionary leadership, summary on the contingency theory of leadership.

The phenomenon of leadership has been studied in different scientific directions and by many researchers. In the 1960s, some researchers realized that the earlier trait theory of leadership and the ensuing behavioral leadership theory were insufficient. Leadership models simply had to consider the situational aspects, including the team members involved and the organization’s state. Adding situational and contingency elements increased the complexity substantially, and previous approaches to leadership could not completely keep up. This new approach to leadership, which is the contingency theory of leadership, or situational leadership theories, opened up for several new and more advanced leadership models. Bear in mind that all these theories, including trait theory and behavioral leadership theory , bring something new to the table and enable you to understand leadership better or from another perspective.

The advocates of the contingency theory of leadership believe that a person can be a good leader in one situation and fail in another. The best type of leadership depends on the environmental situation that arises in the context of a particular action or behavior [1]. In other words, the contingency leadership theory includes the situational prerequisites and effects when studying leadership success or failure. To be a good leader, you should be self-aware, objective, and adaptable and use the leadership style each situation requires. After all, a leader’s personality, behaviors, and skills should be used differently depending on the situation, the involved people, and many other factors. An obvious example is how a police officer leads the apprehension of an armed criminal differently than when comforting a lost child found in the subway. Of course you act differently depending on the situation you are experiencing. Everybody does that to a degree. One way of achieving this effect as a leader is to use different leadership styles that are meant for different situations , i.e., a leadership styles toolbox. You can find styles, trait theory, beavioral theory and many others in Leadership Origins . Here is some additional inspiration as well: 12 common leadership styles and how to select yours .

LEADERSHIP ORIGINS A 116 page E-book with articles on Great Man Theory, Trait Theory, Behavioral Theories (Lewin, Ohio, Michigan, Blake & Mouton), Contingency Theories (Fiedler, Path-Goal, Situational)

Which are the contingency leadership theories?

The contingency theories of leadership are Fiedler’s Contingency Model, Situational Leadership Model, Path-Goal theory, Vroom-Yetton Contingency Model, multiple-linkage model, the six leadership styles by Goleman, to name some of the most famous ones.

Fiedler’s Contingency Model

Fred Fiedler introduced what now is referred to as Fiedler’s Contingency Theory in the mid-sixties, and this was one of the first situational leadership models[2]. Fred Fiedler was an Austrian-born American psychologist that headed organizational research at the University of Washington for more than two decades before leaving in 1992. Fiedler combined several previous studies’ results and came up with a formula known as Fiedler’s Situation Leadership Model or Fiedler’s Contingency Theory of Leadership.

According to Fiedler, a leader’s contribution to performance depends on leadership behavior and the level of compliance with each situation’s circumstances. The novelty with this was that Fiedler stated that a leader could be effective in one situation and not in another. A good leader is not necessarily successful when heading all types of organizations in all situations. To cover this aspect, Fiedler included numerous leader-situation combinations that can guide leaders on how to act. (This paragraph is an extract from our Fiedler’s Contingency Theory of Leadership Article.) This new approach attracted scholars who wanted to explore leadership from this new and different angle.

Path-Goal Theory of Leadership

After Fiedler’s theory, Path-Goal Theory by House, based on path-goal ideas proposed by Vroom and Gerogropolous, emerged. House submitted his Path-Goal Theory in 1971 but revised it 25 years later in 1996. This theory takes a big step further from the Fiedler model and assumes that leaders can and should adapt to different situations. There are two major assumptions in the Path-Goal theory:

- Leadership behaviors are acceptable as long as they contribute to the satisfaction of the followers, either short-term or long-term

- Leadership behaviors are motivated if they provide support, guidance, coaching, and other aspects to the followers as needed to drive performance and create the right atmosphere

Path-Goal focuses on leadership styles depending on the situation and the leader’s behavior while the above assumptions reaming accurate. You will start to recognize some more well-known leadership styles at this point since the four styles or behaviors that House used in his theory are directive, supportive, participative, and achievement-oriented, which you might recognize.

- The Situational Leadership Model

In 1982, Dr. Paul Hersey and Dr. Ken Blanchard published their book “Management of Organizational Behaviour: Utilizing Human Resources”. They probably didn’t realize that this book would help them become world-renowned leadership experts. The central theme of their message was a new approach to leadership, one based on relationship-building and leadership adjustment. This new approach was dubbed the Situational Leadership Model and is often thought to be the leadership model that is perfect for every situation. A Situational leader works assiduously to create meaningful connections with team members. Ultimately, the team receives leadership with the necessary leadership style to fit the organization’s current situation. The Situational Leadership Model is a contingency theory approach to leadership where a leader uses one out of four leadership styles depending on group readiness, competency, experience, and commitment. A situational leader can use telling, selling, participating, and delegating leadership styles. You can read more about this interesting contingency theory in our Situational Leadership Model article.

The contingency theory of leadership kept developing through the 1970s and 1980s, but gradually lost some of its popularity after the 1990s, when researchers began developing interest in other types of leadership theories, slightly gravitating away from the contingency approach. In the early 2000s, this shift resulted in leadership theories such as Ethical Leadership / Moral Leadership and Servant leadership theory . The 2000s also saw Daniel Goleman’s six leadership styles based on Emotional Intelligence , which also has a strong situational approach, although not as concretely and clearly defined with examples situations as earlier contingency theories of leadership.

Situational leadership and contingency theory of leadership are very much in use today, especially regarding the radical and sudden change we have seen during the last couple of years with a global pandemic, supply chain imbalances, work from home, etc. These events underline the need for situational awareness, adaptive leadership, and flexible use of leadership styles [3].

These are the contingency models of leadership [4].

- Fiedler’s model says there are three important factors for “situational favorableness”: leader-member relations, task structure, and leader’s position power.

- The situational leadership model (aka Hersey-Blanchard model) thinks leaders should determine which leadership style would be more effective for a particular team and situation. For this, leaders ought to choose from four leadership styles – Delegating style, Participating style, Selling style, and Telling style.

- The Path-Goal Theory of Leadership states that leaders should be extremely flexible in selecting a concrete style to help team members reach their individually set goals. When saying leadership styles, the model mentions The Directive Clarifying Leader, The Achievement-Oriented Leader, The Participative Leader, and The Supportive Leader.

- The Decision-Making model (aka the Vroom-Yetton contingency model) proves that decision-making is the most important factor affecting the relationship between the leader and the team members. So the formers should build and maintain the relationship. In this model, there are five leadership styles, including Autocratic (A1), Autocratic (A2), Consultative (C1), Consultative (C2), and Collaborative (G2).

- The Multiple-Linkage Model (developed by Gary Yukl in 1981) says that it is impossible to assess factors of a leader’s behavior on group performance separately. It is complex, consisting of Managerial behaviors, Intervening, Criterion, and Situational variables. Leaders will influence these factors in several ways, and it is related to the situation.

- Cognitive Resource Theory is considered to be the reevaluation of the Fred Fiedler contingency model. It considers three main factors, such as personality, the degree of situational stress, and group-leader relations.

All these models might seem substantially different, but they are all leadership contingency theorie and most of them can be found in Leadership Origins , our e-book on leadership theories. So there is a noticeable red line seen in all models – effective leadership is contingent on the situation, task, and people involved. The leader should adopt the leadership style that results in maximum effectiveness.

Leadership effectiveness and outcomes correlate with various factors such as the scope of a project, organization, or endeavor, type and structure of the team, deadlines, tasks specifications, etc. All leaders will organize the management of these factors with some sort of personal judgment and touch. Hopefully, every leader purposely selects one or a few leadership styles based on these factors and switches when the circumstances have changed enough to justify another leadership style. In this sense, contingency theorists believe that every situation is challenging. No matter how many times a leader succeeds, no personal skill or experience would guarantee success every time, unless the leader can act differently and appropriately. Proper analysis and situational assessment, resulting in a selected leadership style approach, combined with personal skills and behaviors, simply increase the likelihood of success, making contingency theory crucial to any modern leader.

There could be situations that no leadership style a leader is familiar and skilled at will fit situations. In those situations, the leader should consider using other talented people more suitable for the situation. I will give you a personal example. As a CEO, I have a VP in my team that possesses excellent presentation skills and industry knowledge. Although I am a decent presenter, certain topics suit this VP better, rendering a stronger impact if he holds the presentation. Hence, I try to inject him on such occasions to maximize the impact of our scheduled presentations. A more complex situation is when I switched places on two VPs with different leadership approaches depending on the situational readiness in two other parts of the company. One area had been led by a very relationship-oriented VP for some time and needed more systems and structure, which the replacement could put in place. The other area had a very new team and needed strong people skills to build team commitment and recruit new members, a perfect fit for the relationship-oriented VP.

Generally, a myriad of factors affects the effectiveness of leadership and impact on the team and organization. When talking about the team, those factors might be the maturity level of the employees, relationships between coworkers, various working styles of employees, team morale, etc. ( The Situational Leadership Model does a great job at providing structure on team readiness.) Another group of factors might include the work pace, deadlines, clearly set goals or outcomes, etc. Lastly, a company’s management style and policy might play a crucial role in leadership effectiveness.

Perhaps it sounds like selecting which leadership style to use is a time-consuming and challenging task, but that is hardly the case. Once you have gotten used to various leadership styles for different types of situations and gained enough experience, the shift can become natural and fluid. I have done this for years, and you can do it too. You might not always use the most optimum leadership style , but you will for sure do a better job by adapting than by using the same constant behaviors regardless of what is going on around you.

All theories have limitations, and these are some of the advantages and disadvantages of the contingency theory of leadership.

Pros of Leadership Contingency Theory

The Contingency theory of leadership has the following advantages:

- Contingency theory shifted leadership research from traits and behaviors to also include situational and team aspects.

- Lots of empirical research supports the contingency theory of leadership. The situation truly matters, and a behavior-only model is inadequate.

- Contingency theory underlines that there is no single ideal leadership style. This pushes leaders to be more adaptive and flexible by using multiple leadership styles , taking the situation and team members, etc., into account.

- The adaptive mindset of contingency theory helps underline the importance of leaders keeping up with changes in operational and strategic environments and requirements, such as market shifts, trade flows, technological disruption, competition, etc.

Cons of Leadership Contingency Theory

The Contingency theory of leadership has the following disadvantages:

- Contingency theory does not provide detailed guidance for every possible situation – but again, no leadership theory does, and contingency theory probably comes the closest.