- USF Research

- USF Libraries

Digital Commons @ USF > Office of Graduate Studies > USF Graduate Theses and Dissertations > USF Tampa Theses and Dissertations > 9396

USF Tampa Graduate Theses and Dissertations

The tesla brake failure protestor scandal: a case study of situational crisis communication theory on chinese media.

Jiajun Liu , University of South Florida

Graduation Year

Document type, degree name.

Master of Arts (M.A.)

Degree Granting Department

Communication

Major Professor

Kelli Burns, Ph.D.

Committee Member

Kelly Werder, Ph.D.

Kilmberly Walker, Ph.D.

Electric vehicle, Crisis communication strategy, Cultural difference, Situational crisis communication theory

The aim of this thesis is to test how Tesla handles a protestor in Tesla’s booth in Shanghai. This thesis evaluated the effectiveness and acceptance of Tesla’s public relations and crisis communication through analyzing domestic Chinese official news articles and consumers’ attitude on China’s most used social media platform, Weibo. The electric vehicle industry is relatively a newer industry than traditional automobile manufacturing industries. Therefore, the immaturity of the industry could bring different types of crises, and traditional vehicle problems could also be the problems of electric vehicles, such as engine failure, brake failure, safety concerns and security threats, and so on. A proper crisis communication strategy is an essential and significant part for these electric vehicle companies. This study utilized situational crisis communication theory as the theoretical framework, as it could provide a structure for analyzing the crisis facing the company. This paper provides insights for the electric vehicle industry or even the other same kinds of automobile field. As the consequence of the application of theory, this study aims to figure out what are the strategies that Tesla used in its crisis communication, according to situational crisis communication theory (SCCT), and what are not included in the SCCT. This study explored how domestic news media portrayed this case and Netizens’ attitudes on social media towards this case. This study used a content analysis method through analyzing news reports and consumers’ attitudes on social media to examine Tesla’s crisis communication during the crisis period. If the crisis communication strategies were thoughtfully utilized, Tesla could recover from the crisis as soon as possible rather than facing a period time of decline. After examination of the SCCT in Tesla’s crisis communication, the results learned from this case could be regarded as precious experience for the new energy automobile car industry in China. And, also the relationships between Tesla and the public in China could be considered as one of optional communication strategies when other automobile manufacturers are facing any kind of crisis in the future.

Scholar Commons Citation

Liu, Jiajun, "The Tesla Brake Failure Protestor Scandal: A Case Study of Situational Crisis Communication Theory on Chinese Media" (2022). USF Tampa Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/9396

Since September 20, 2022

Included in

Mass Communication Commons

Advanced Search

- Email Notifications and RSS

- All Collections

- USF Faculty Publications

- Open Access Journals

- Conferences and Events

- Theses and Dissertations

- Textbooks Collection

Useful Links

- USF Office of Graduate Studies

- Rights Information

- SelectedWorks

- Submit Research

Home | About | Help | My Account | Accessibility Statement | Language and Diversity Statements

Privacy Copyright

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

Ai generator.

Embark on a comprehensive journey through the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) in this definitive guide enriched with practical examples. Unveil the nuances of effective crisis communication and discover how SCCT transforms challenging scenarios. From communication examples to actionable insights, this guide equips you to navigate crises with confidence, making it an invaluable resource for honing your communication skills in the face of adversity. Explore the dynamic interplay of theory and real-world application for mastery in crisis communication.

What is Situational Crisis Communication Theory?

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) is a strategic framework designed to guide effective communication during times of crisis. In simple terms, SCCT helps organizations tailor their messages based on the nature and severity of a crisis. It emphasizes the importance of considering public perceptions and adjusting communication strategies accordingly. By understanding SCCT, one gains insights into crafting messages that not only address the crisis at hand but also maintain and restore trust in the eyes of the audience.

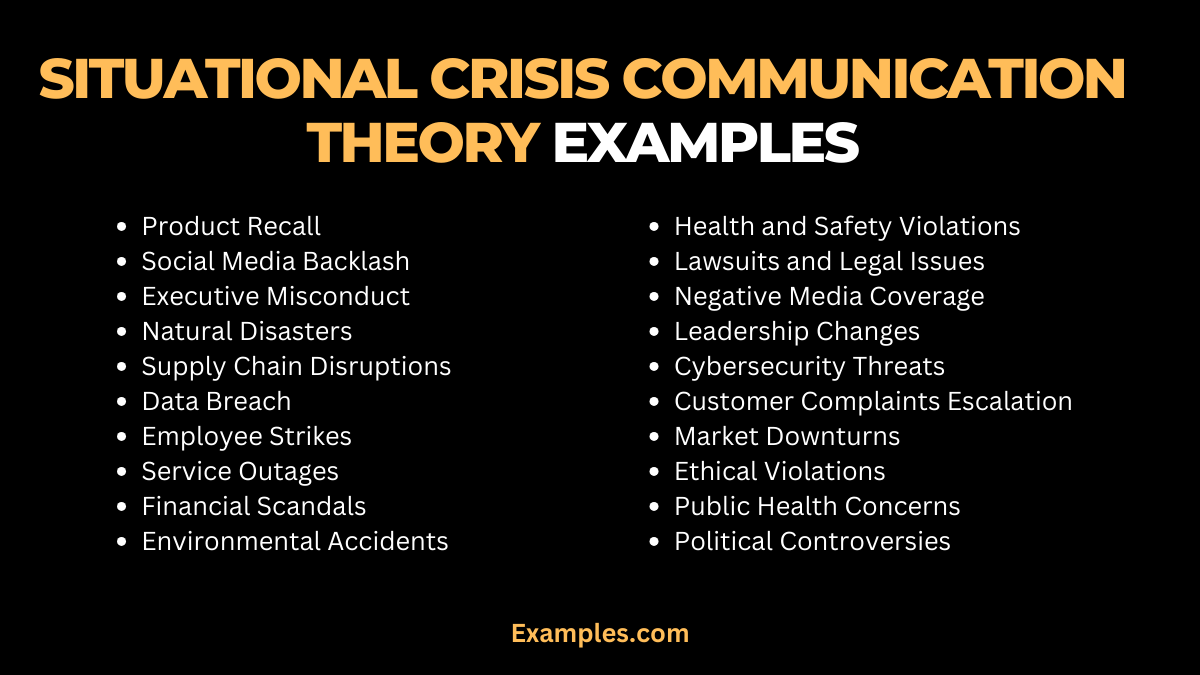

20 Situational Crisis Communication Theory Examples

- Product Recall: Swiftly address concerns, ensuring transparency and outlining safety measures.

- Social Media Backlash: Respond promptly, acknowledging concerns and providing reassurance.

- Executive Misconduct: Convey accountability, detailing corrective actions taken to rebuild trust.

- Natural Disasters: Offer immediate aid information, showcasing a proactive and caring stance.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Communicate alternative solutions, minimizing customer inconvenience.

- Data Breach: Apologize, assure data security improvements, and outline compensation measures.

- Employee Strikes: Engage in open dialogue, addressing concerns and demonstrating commitment.

- Service Outages: Keep customers informed, offering realistic resolution timelines.

- Financial Scandals: Publicly admit faults, outline corrective measures, and commit to transparency.

- Environmental Accidents: Assume responsibility, provide cleanup details, and promise preventive measures.

- Health and Safety Violations: Communicate immediate corrective actions and prevention strategies.

- Lawsuits and Legal Issues: Offer transparent statements, highlighting compliance with legal processes.

- Negative Media Coverage: Address inaccuracies, clarify facts, and present the organization’s perspective.

- Leadership Changes: Articulate the vision for the future, ensuring a smooth transition.

- Cybersecurity Threats: Assure data protection measures, detailing cybersecurity enhancements.

- Customer Complaints Escalation: Respond empathetically, offering personalized resolutions.

- Market Downturns: Communicate adaptive strategies, assuring stakeholders of recovery plans.

- Ethical Violations: Express remorse, share corrective actions, and recommit to ethical practices.

- Public Health Concerns: Disseminate accurate information promptly, showcasing preventive measures.

- Political Controversies: Remain neutral, focus on the organizational mission, and avoid taking sides.

Situational Crisis Communication Theory Examples for Student Organizations

Discover how Situational Crisis Communication Theory applies to student organizations, ensuring effective crisis management and preserving organizational reputation. Explore unique examples tailored to the challenges faced by student-led groups, providing valuable insights into crisis communication strategies in educational settings.

- Fund Mismanagement: Transparently address financial discrepancies, communicate corrective actions, and involve the student body in improved financial oversight.

- Leadership Controversy: Engage in open forums, address concerns, and ensure transparent communication to rebuild trust in the leadership.

- Event Cancellations: Apologize for any inconvenience, communicate alternative plans or compensations, and involve students in future decision-making.

- Social Media Backlash: Respond promptly to negative comments, acknowledge concerns, and showcase proactive measures to address any issues raised.

- Academic Integrity Violation: Clearly communicate actions taken to address the violation, emphasize organizational commitment to academic integrity, and implement preventive measures.

Situational Crisis Communication Theory Examples in Case Study

Description: Delve into real-life case studies demonstrating the application of Situational Crisis Communication Theory. Explore how organizations navigate diverse crises, applying SCCT principles for effective communication and reputation management. Gain actionable insights from these dynamic examples to enhance your crisis communication skills.

- Product Recall Case: Swiftly communicate the recall, provide detailed information on replacement or compensation, and assure consumers of enhanced quality control measures.

- Environmental Disaster Case: Assume responsibility, communicate immediate response actions, and outline long-term sustainability initiatives to rebuild public trust.

- Employee Misconduct Case: Publicly acknowledge the misconduct, detail corrective actions taken, and emphasize organizational values to restore faith in the company.

- Market Competition Challenge: Communicate adaptive strategies, reassure stakeholders of competitive strengths, and outline plans for market resurgence.

- Public Relations Crisis Case: Address media inaccuracies, clarify facts through a press conference, and consistently maintain open communication to shape the narrative positively.

What are Situational Crisis Communication Theory Strategies?

Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) provides strategic approaches for effective crisis communication. Key strategies include:

- Develop proactive communication plans.

- Identify potential crises and formulate tailored responses.

- Adopt crisis response strategies based on the severity of the situation.

- Determine whether to deny, diminish, rebuild, bolster, or bolster with differentiation.

- Establish clear communication channels with internal and external stakeholders.

- Collaborate with key entities for a unified crisis response.

- Prioritize transparency in communication.

- Share information openly to maintain credibility.

- Tailor messages to the specific crisis and audience.

- Adjust communication style based on the evolving situation.

- Engage with media effectively.

- Provide accurate information promptly to shape public perception.

- Conduct post-crisis evaluations.

- Learn from experiences to enhance future crisis communication strategies.

What is the Importance of Situational Crisis Communication Theory?

Understanding the significance of SCCT is crucial for effective crisis management:

- SCCT helps organizations maintain a positive image during crises.

- Preserving reputation is vital for long-term success.

- SCCT enables customized messaging based on crisis severity.

- Tailored communication resonates better with stakeholders.

- Transparent communication fosters trust.

- Trust is pivotal for stakeholder loyalty and support.

- SCCT minimizes the negative impact of crises.

- Swift and well-crafted communication can mitigate fallout.

- SCCT guides strategic decision-making during crises.

- It provides a framework for choosing appropriate communication responses.

How Situational Crisis Communication Theory Helps Business?

- Adaptive Response: SCCT enables adaptable crisis communication tailored to each unique situation, ensuring alignment with organizational values.

- Maintaining Stakeholder Confidence: Through a systematic approach, SCCT fosters consistent communication, building and maintaining stakeholder trust.

- Mitigating Legal and Financial Risks: SCCT aids in navigating legal and financial challenges by promoting well-managed crisis communication.

- Strategic Brand Management: SCCT contributes to strategic brand management, safeguarding brand integrity during challenging times.

- Long-Term Resilience: Incorporating SCCT principles enhances long-term resilience, preparing businesses to navigate and overcome crises effectively.

In conclusion, navigating crises demands strategic communication, and Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) offers a vital framework. This complete guide has unraveled SCCT, providing insights into its strategies and showcasing real-world examples. Armed with this knowledge, communicators can adeptly steer through challenging situations, ensuring effective responses and safeguarding organizational reputation. Mastering SCCT is not just a choice; it’s a necessity for resilient and successful crisis communication.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Situational Crisis Communication Theory Examples in Case Study

10 Situational Crisis Communication Theory Examples for Student Organizations

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 02 October 2023

Mapping crisis communication in the communication research: what we know and what we don’t know

- Shalini Upadhyay 1 &

- Nitin Upadhyay 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 632 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5423 Accesses

1 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

This paper presents a comprehensive analysis of crisis communication research from 1968 to 2022, utilizing bibliometric methods to illuminate its trajectories, thematic shifts, and future possibilities. Additionally, it presents foundational themes such as crisis communication and social media, health communication, crisis and leadership, and reputation and advertising. This analysis offers not only historical insights but also serves as a roadmap for future research endeavors. Furthermore, this study critically evaluates over five decades of scholarship by unveiling the intellectual, social, and conceptual contours of the field while highlighting thematic evolutions. Employing diverse bibliometric indices, this research quantifies authors’ and nations’ productivity and impact. Through co-word analysis, four thematic clusters emerge, capturing the dynamic nature of crisis communication research. However, the study also reveals limited collaboration among authors, primarily localized, indicating room for enhanced cross-border cooperation and exploration of emerging themes. The study’s social network analysis sheds light on key actors and entities within the crisis communication realm, underscoring opportunities to fortify global networks for a robust crisis communication spectrum. Beyond academic curiosity, these insights hold practical implications for policymakers, scholars, and practitioners, offering a blueprint to enhance crisis communication’s effectiveness. This study’s findings can be considered as a reference point for future studies in crisis communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

The language of crisis: spatiotemporal effects of COVID-19 pandemic dynamics on health crisis communications by political leaders

Unveiling evolving nationalistic discourses on social media: a cross-year analysis in pandemic

Disinformation on the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War: Two sides of the same coin?

Introduction.

Although crisis communication as such is not a new phenomenon (Coombs, 2021 ), it’s role has become more prominent in recent times because of the events such as 9/11, SARS, COVID-19 pandemic (Avraham and Beirman, 2022 ; Watkins and Walker, 2021 ). Such events have posed unprecedented challenges to crisis management teams and necessitated effective communication and appropriate response strategies. At the same time, these events have revived scholarly interest in the topic (Coombs, 2021 ). As a result, it becomes essential for the scholars to perform timely review of the literature, to explore and understand the diversity of the specific field (Tranfield et al., 2003 ). Not only such reviews help to consolidate the research but also establish connections between disparate bodies of research and understand the diversity of the field (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010 ; Tranfield et al., 2003 ).

Coombs ( 1998 ) defines crisis as “an event that is an unpredictable, a major threat that can have a negative effect on the organization, industry, or stakeholders if handled improperly.” Since a crisis can cause financial and reputational damage to the company, a considerable attention has been given to the research on crisis, crisis management and crisis communication (Coombs and Holladay, 2002 ) and also on appropriate crisis response strategies so as to enable the organizations to manage crisis and reduce harm (Coombs, 2007a ). Our results depict that crisis communication received recognition during late 1960s, and the first studies on “crisis communication” were published only in 1968. The field had limited contribution until late 1990s. However, the double digit annual publication began in the early 2000s and in the recent years the contribution has grown with over 150 publications annually. Between 1991 and 2009, the image restoration theory (Benoit, 1995 ; Benoit, 1997 ) and the situational crisis communication theory (Avery et al., 2010 ; Coombs, 1995 ; Coombs 2007b ) dominated crisis communication research. The image restoration theory was applied to analyze and study several case-based situations while the situational crisis communication theory was extensively utilized for experimental research. Both the theories have been adopted for qualitative and quantitative analyses with an aim to prevent reputational harm and thus these theories became organization centric. The current trend is more towards understanding stakeholders’ perspectives with a multivocal approach (Frandsen and Johansen, 2017 ). Additionally the dominance of social media increases the complexity of crisis communication (Bukar et al., 2020 ; Eriksson, 2018 ).

In the extensive literature on crisis communication, scholars have approached the study of crisis communication from various perspectives and have examined it through multiple lenses. Several recent literature (For e.g., Seeger et al., 2016 ; Zhao, 2020 ) have shed light on these perspectives. The research encompasses different stakeholders involved in crisis communication, including the supply side (such as destinations, cruise lines, hotels, and airlines), the demand side (including tourists, prospective visitors, and general public), as well as other relevant stakeholders like government entities, local residents, and employees. Moreover, the research has explored crisis issues across a wide spectrum, ranging from natural disasters like hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes, and wildfires, to human-made crises such as terrorist attacks and service failures (Avraham and Beirman, 2022 ; Watkins and Walker, 2021 ). Furthermore, the literature has also addressed the unprecedented crisis brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had far-reaching implications for crisis communication. Importantly, the body of research takes a global perspective, encompassing various regions and countries. For instance, studies have examined crisis communication practices in diverse regions, including Asia, the Middle East, coastal destinations, as well as Western countries like Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. This global lens provides valuable insights into the different cultural, social, and contextual factors that shape crisis communication strategies and outcomes across different regions. However, the recent trends related to crisis communication scholarly research have gained traction, particularly in the past decade, especially in the US region (For e.g., Barbe and Pennington-Gray, 2018 ; Beck et al., 2016 ; Briones et al., 2011 ; Kwak et al., 2021 ; Liu et al., 2015a , 2015b ; Seeger et al., 2016 ; Sellnow and Seeger, 2013 ; Zhao, 2020 ).

Moreover, crisis communication research has been fragmented over the past two decades due to the emergence of several new sub-fields (Coombs, 2010 ; Coombs, 2021 ). This poses challenges to the researchers to cope up with the pace and volume of corpora (Yuan et al., 2015 ). Scholars (e.g., Lim et al., 2022 ; Mukherjee et al., 2022 ) recommend capturing scientific progress of a field by means of a systematic and comprehensive review. There are several review techniques that may be used to trace the scientific growth and potential research domains of a field. Various such review techniques have been employed in the crisis communication field to integrate and synthesize the existing knowledge. However, these studies have limited coverage and context of crisis communication. For example, previous studies have focused on organizational crisis communication (Fischer et al., 2016 ) and crisis communication in public relations (Avery et al., 2010 ). Few papers have intensively reviewed crisis communication during the pandemic and infectious disease outbreaks (MacKay et al., 2022 ; Malecki et al., 2021 ; Sadri et al., 2021 ) or captured risk and disaster communication (Bradley et al., 2014 ; Goerlandt et al., 2020 ). Lately, the focus has shifted toward using virtual channels and space (Eriksson, 2018 ; Liu-Lastres, 2022 ; Tornero et al., 2021 ; Wang and Dong, 2017 ; Yang, 2016 ).

However, these studies have dealt with the development of the field either through the qualitative approach in structured literature review (e.g., Valackiene and Virbickaite, 2011 ) or through the quantitative content analysis method (e.g., Li, 2017 ). Zupic and Čater ( 2015 ) claim that though structured literature review analysis deals with an in-depth examination, it insinuates subjective biases thereby constraining the scope of works. Additionally, despite its broader coverage in exploring key authors, topics, theories and methodologies, the content analysis is unable to capture the socio-cognitive structure. Suffice it to say that a comprehensive literature review which may capture intellectual, social and conceptual structures along with the thematic evolution of the crisis communication field has not been attempted (Ha and Boynton, 2014 ; Sarmiento and Poblete, 2021 ).

To overcome this gap bibliometric analysis is recommended which comprehensively captures the literature and traces its thematic evolution (An and Cheng, 2010 ; Moreno-Fernández and Fuentes-Lara, 2019 ; Zurro-Antón et al., 2021 ). Moreover, it facilitates the exploration of various performance metrics and mapping of the intellectual, social, and conceptual structures (Harker and Saffer, 2018 ; Lazzarotti et al., 2011 ). Wamba and Queiroz ( 2020 ) argue that bibliometric analysis examines large corpora of literature in an objective and evidence-based outcomes and it is more effective than the traditional methods (e.g., systematic literature review, meta-analysis, narrative analysis, etc.), which are labor-intensive and subjective. Additionally, bibliometric methods and visualization examinations are scalable and can be easily applied to a large corpora of literature covering authors and articles (Ki et al., 2019 ; Morgan and Wilk, 2021 ).

There are two approaches in bibliometric techniques—evaluative and relational. The evaluative review uses qualitative and quantitative methods covering aspects of the field’s ranking and contribution of different elements (e.g., sources, documents, institutions, and authors) (Benckendorff, 2009 ). The evaluative review focuses on productivity and impact (McKercher, 2012 ; Park et al., 2011 ). In contrast, relational review investigates relationships within the structures of the research field. It explores thematic evolution, co-authorship patterns, and co-citation (Benckendorff and Zehrer, 2013 ). Cobo et al. ( 2012 ) propose four different relational techniques for different contexts that answer who, when, where, what, and with whom questions by performing suitable analyses such as profiling, temporal, geospatial, topical, and network. It also facilitates a three-level analysis- micro (individual researchers), meso (regional-groups- journals), and macro (entire field). Overall, the relational analysis provides an in-depth coverage of the field, however, in the crisis communication area, it has not been utilized to explore and understand crisis communication research activity. Thus there is an inadequate synthetization of numerous aspects of the field in a single paper.

This paper utilizes relational analysis to explore and investigate the broad structure of crisis communication research. It aims at mapping crisis communication field by exploring its social, intellectual and conceptual structures over the past 50 years. Subsequently, the paper’s specific objectives are- determining the influential authors, countries and sources; and identifying major thematic areas affecting thematic evolution. Therefore, the process and outcomes of this paper are different from the studies that have either used or use traditional methods, as discussed above. However, the study’s outcomes complement those review articles that focus on specific contexts and aspects of crisis communication.

Methodology

In this study, we aim to map crisis communication in the communication research. The study also seeks to find the field’s social, intellectual and conceptual structures over the past 50 years. Additionally the future directions need to be explored.

Research questions

We defined the following research questions to map crisis communication in the following way:

RQ1: Who are the prominent contributors to the literature on crisis communication discipline?

RQ2: What is the social structure (or collaboration patterns) in crisis communication literature?

RQ3: What is the conceptual structure (or main research themes) in crisis communication literature?

RQ4: What is the intellectual structure in crisis communication literature?

RQ5: What are the future research directions in crisis communication scholarship?

The first research question was aimed at identifying the core contributors (author, document, source, institution and country) to the literature on crisis communication discipline, while the second question was designed to examine the collaboration pattern across levels—individual, institution, and country-level. The purpose of the third question was to gain more in-depth insights into the themes that have received attention in the literature. While the fourth research questions was aimed at identifying the intellectual patterns across levels—individual, document, and source. Finally, the fifth question was to identify the future directions in the crisis communication field.

We prepared the data considering two steps. First, we selected the source of data and then extracted the relevant articles based on the search query. We selected Scopus database to extract the relevant articles. The Scopus database includes all authors in cited references. This gives accuracy to the author-based citation and co-citation analysis. Further, we searched for the term “crisis communication” to extract relevant articles, and subsequently gathered 2487 documents. However, to explore the growth, contributions, and thematic areas we limited our search only to the journal articles in the English language. The search fields focus on covering abstracts, titles and keywords. Moreover, the search also had a criteria of limiting extraction of only articles (research and review) from peer-reviewed journals and excluding documents such as opinion pieces, book reviews, and commentaries. Finally, a sample of 1850 papers were included for further analyses.

Bibliometric methods for addressing RQs

We addressed RQ1 by performing descriptive analysis to identify core sources, authors, countries, publications, affiliations and prominent contributors to the literature on crisis communication. Measurements such as source impact (h-index and m-index), total citations (TC), and annual net publications (NP) were used to determine core sources and core authors. We used Bradford’s law to identify the core sources which are categorized into three zones. Zone 1 (the nuclear zone) is considered highly productive, while zones 2 and 3 represent moderate and low productions respectively (Zupic and Čater, 2015 ). Further, publication frequency and total citations were used to determine the top countries and affiliations.

We addressed RQ2 by using co-author analysis as it provides evidence of co-authorship when the authors jointly contribute to papers. Social structures are created when authors collaborate to develop and create articles. Moreover, when two authors co-publish a paper, they establish social ties or relationships (Lu and Wolfram, 2012 ). Co-authorship analysis can examine social structure at the level of the institute and the country. Co-authorship networks play a significant role in analyzing scientific collaboration and assessing the status of individual researchers. While they bear some resemblance to extensively studied citation networks, co-authorship networks signify a more robust social connection than mere citations. Unlike citations, which can occur between authors who are unfamiliar with each other and extend over time, co-authorship signifies a collegial and time-bound relationship, making it a focal point of Social Network Analysis (SNA) (Acedo et al., 2006 ; Fischbach and Schoder, 2011 ). To build the collaboration network, Louvain method was used as a clustering algorithm (Lu and Wolfram, 2012 ). The threshold of 50 as the number of nodes and 2 as the minimum edges were considered to avoid isolated and “one-time” collaboration. The nodes depicting isolation due to a lack of ties or relationships were removed.

Furthermore, in the field of social network analysis, centrality measures are crucial when examining the status of actors within a network. While various methods and measures are employed in SNA, centrality provides valuable insights into an actor’s position. One commonly used measure is degree centrality, which captures the basic essence of centrality by quantifying the number of connections an actor has with its immediate neighbors in the network. It reflects the total number of edges adjacent to a node and represents the incoming and outgoing links of an actor. Another significant measure is closeness centrality, which focuses on an actor’s proximity to all other actors in the network. While authors may be well-connected within their immediate neighborhood, they could still be part of partially isolated groups. Despite having strong local connections, their overall centrality might be limited. Closeness centrality extends the concept of degree centrality by emphasizing an author’s closeness to all other authors. Calculating closeness centrality requires determining the shortest distances between a node and all other authors, and then converting these values into a metric of closeness. A central author in the network is identified by having multiple short links to other authors. In addition, betweenness centrality offers a distinct perspective on centrality. It measures how often a particular node lies on the shortest path between pairs of nodes in the network. Nodes that frequently appear on these paths are considered highly central as they regulate the flow of information within the network. Although betweenness centrality can be applied to disconnected networks, it may result in numerous nodes with zero centrality since many nodes may not act as bridges within the network. This measure is based on the number of shortest routes passing through an actor. Actors with high betweenness centrality act as “middlemen,” linking different groups together.

Network analysis software enables the computation of centrality measures such as degree, betweenness, and closeness. These measures hold varying significance based on the specific network under examination. For instance, within a co-authorship network, an author’s degree centrality reflects the number of co-authored papers with other authors (Fischbach and Schoder, 2011 ). High betweenness centrality suggests that an author serves as a crucial link between distinct research streams. Furthermore, authors with high closeness centrality can establish connections with other authors in the network through shorter paths. UCINET (Borgatti et al., 2002 ) and Pajek (Batagelj and Mrvar, 1998 ) are the predominant software packages employed for network visualization purposes. For the present study, Pajek was employed to examine the social network and conduct centrality analyses.

We addressed RQ3 by using co-word analysis to gather concept space knowledge by utilizing the co-occurrence frequency of keywords. A co-word network is prepared based on the co-occurrence of words to examine specific areas of interest in crisis communication. We performed co-occurrence network analysis and hierarchical clustering to identify clusters that represent common concepts. The results were then described on the thematic map and theme evolution space. We considered 50 nodes as a threshold and a minimum of two edges for each node. Further, we chose the Louvain method for the clustering algorithm and the association as the normalization parameter for the analysis. Thematic mapping, built upon the keyword co-occurrence network and clusters, was performed to study the conceptual structure. We divided the evolution of thematic areas into four distinct periods (1968–1999, 2000–2007, 2008–2014, 2015–2022). These thematic areas represent a group of evolved themes across different subperiods. The evolution of key themes helps to understand variations in the research stream as well as provide necessary directions for future research., while interconnections link one theme with another thematic area. We also developed a thematic map representing four different themes based on their placement in the quadrant (Cobo et al., 2012 ), for example,

Themes placed in the upper-right quadrant are based on strong centrality and high density. These are the motor themes which are well developed and are important for shaping the research field.

Themes placed in the upper-left quadrant refer to the niche themes that are specialized and that depict peripheral characteristics.

Themes placed in the lower-left quadrant refer to the emerging or disappearing themes. They depict weak centrality and low density. Such themes are weakly developed.

Themes placed in the lower-right quadrant refer to the basic themes. These themes are important to the research field but are underdeveloped.

For addressing the RQ4, we performed co-citation analysis to develop clusters depicting the intellectual base of the field. Co-citation refers to the citation of two (or more than two) articles in the third article, which is the counterpart of bibliographic coupling. The Louvain method was used as a clustering algorithm to develop the co-citation network considering articles, authors, and sources. A threshold of 50 for a number of nodes, and 20 as the minimum edge strength (representing approximately 5% of the corpora in crisis communication) was considered. This as a whole aided in performing cluster level analysis.

Finally, the synthesis of the results of RQ1, RQ2, RQ3, and RQ4 helped to address the RQ5.

Scientific output (RQ1)

This section elaborates on the research landscape of crisis communication from 1968 to 2022. We gathered a total of 1850 articles by 3277 authors from 1222 institutions published in 646 journals as per the set criteria.

Publication output

The contribution to the field is highest through journal articles with over 95%, followed by review articles (4.7%). Moreover, around 28% of the articles are single-authored publications, while 72% are published in collaboration. The overall annual production of articles in crisis communication shows an exponential growth (Supplementary Fig. S1 ). The growth of the articles is stagnant between 1968 and 2000, with a few publications until 2000. However, growth is evident from the early 2000s, crossing double-digit publications annually. From 2015 onwards, annual publication growth improves by over 100 publications. Between 2020 and 2022, the annual publication count increases by over 200. Since 2015, the number of annual publications has been larger than the cumulative number of articles published before 2015. Overall, the annual growth rate of the research articles is 15% (the calculation does not include the period 1968–2000 and 2022 due to sensitivity).

Source output

A total of 1850 articles have appeared in 646 journals. The leading journals are the Public Relations Review which has hosted 249 publications, followed by the Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management with 65 publications. Subsequently, the Journal of Communication Management has hosted 51 publications, followed by Corporate Communications with 48 publications, and then the Journal of Public Relations Research with 37 publications, respectively (Supplementary Table S2 ). The subject of crisis communication also belongs to the broader area of public relations and communication, which matches with the aims and scope of these journals. Additionally, the most cited sources, showcasing that the Public Relations Review has fetched the highest citations of 8284, followed by Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management with 1539 citations. Subsequently, the Journal of Applied Communications Research has fetched 1522 citations, followed by the Journal of Public Relations Research with 1333 citations, and Corporate Reputation Review with 1158 citations, respectively. The Public Relations Review is identified as the top outlet for publication having the highest impact in the crisis communication field.

Most productive authors

Considering our dataset, 3277 authors from 1222 organizations have published articles on crisis communication. Sellnow has published the maximum number of articles with 35 publications on crisis communication, followed by Jin with 34 articles (Supplementary Table S3 ). Subsequently, Liu has published 33 articles followed by Spence with 28 articles, and then Lachlan has published 27 articles.

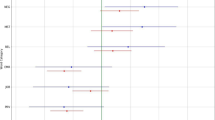

The author’s productivity and impact are measured considering the number of published articles and citations per year. It can be noted that Sellnow, Jin, Liu, Spence, and Lachlan are the most productive authors. While Coombs, Jin, Holladay, Liu, and Sellnow have received the highest citations (Supplementary Fig. S4 ). Scholars argue that the total citations received is not the only metric that determines the author’s production (Forliano et al., 2021 ; Huang and Hsu, 2005 ). Thus, we used three indicators—m-index, h-index, and the total citations (Supplementary Table S5 ). The most cited authors having more than 1000 citations in the database are Coombs (with 3418 citations), Jin (with 1914 citations), Holladay (1833 with citations), Liu (with 1655 citations), Sellnow (with 1299 citations), Spence (with 1200 citations), and Seeger (with 1095 citations). However, Coombs (TC = 3418 and h index = 18), Jin (TC = 1914 and h-index = 20) and Liu (TC = 1299 and h-index = 18) and Sellnow (TC = 1299 and h-index = 20) have the best combination of productivity and impact (Hirsch, 2005 ). For example, Coombs with h-index 18 has published 18 articles that have received at least 18 citations. Out of the top 20 contributors, 11 authors have h-index of at least 10. Hirsch ( 2007 ) suggests considering the contribution of young authors by the metric m-index, which determines the h-index weighted for the activity period of an author. Hence, young authors such as Claeys, Cauberghie, Kim, and Liu who started publishing from 2009 can be counted amongst the most influential authors.

Most productive institution

The most active organizations in this field are the University of Maryland (with 79 publications), the University of Kentucky (with 75 publications), the University of Florida (with 51 publications), the University of Georgia (with 50 publications), and Nanyang Technological University (with 49 publications) (Supplementary Table S6 ).

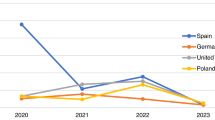

Most productive countries

Scholars argue that multi-authored publications might not represent the open collaborations dimensions of the most prolific countries publishing the articles. Thus, three different metrics are considered: SCP (single-country publication; intra-country publications), MCP (multiple-country publications; inter-country publications) and MCP ratio (ratio between MCPs and the total number of publications in the database TC; Supplementary Table S7 ). The MCP ratio determines the level of openness of the country to collaborate. It is noted that the intra-country publications are highest in the USA (SCP = 589), Germany (SCP = 51), China (SCP = 42), Sweden (SCP = 42), and the United Kingdom (SCP = 41) while inter-country publications are highest in the USA (MCP = 41), Korea (MCP = 23), the United Kingdom (MCP = 20), China (MCP = 17), and Hong Kong (MCP = 15). However, considering the MCP ratio, Hong Kong (MCP ratio = 0.555), Korea (MCP ratio = 0.54), Finland (MCP ratio = 0.33), the United Kingdom (MCP ratio = 0.32), and China (MCP ratio = 0.28) showcase openness in collaborations. It is surprising to note that the top 2 countries (USA and Germany) despite publishing the highest number of articles have limited openness in international collaborations as per the MCP ratio.

Additionally, considering total citations and production, the US emerges as the leader in production and impact; however, Korea, Netherlands, and Australia show a rising trend in terms of the impact, while China and Sweden, a declining trend (Supplementary Table S8 ).

Social structure (RQ2)

In this section, we performed analysis of collaborations patterns across three levels: author, institution, and country. Crisis communication has received contributions from 75 countries and 1222 different institutions publishing 1850 articles that depict global attention given to the field. In the database, multiple-authored articles (72% of the total published articles) are higher than single-authored articles.

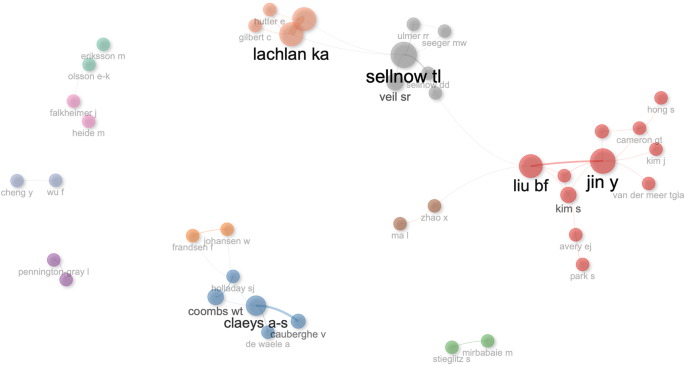

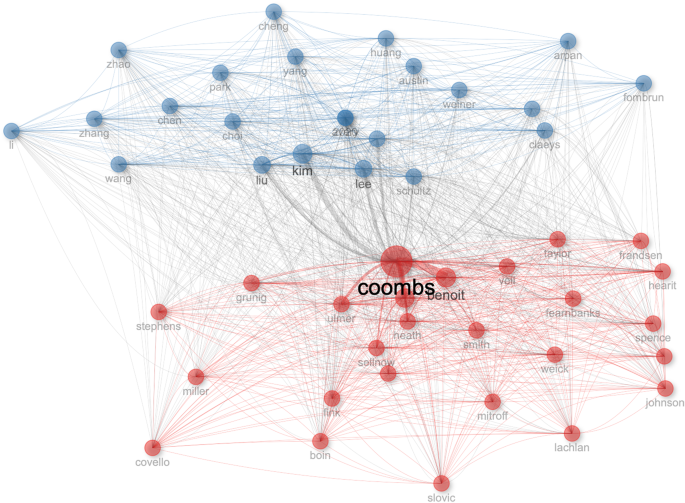

Authors’ social structure

Figure 1 shows 11 clusters (in different colors) of the 36 most influential authors. Out of these 11 clusters, 6 are dominated by double authors while rest have more than two authors. Among the double author collaborations clusters, the one including Coombs and Holladay leads in terms of contribution and impact.

The network depicts 11 clusters.

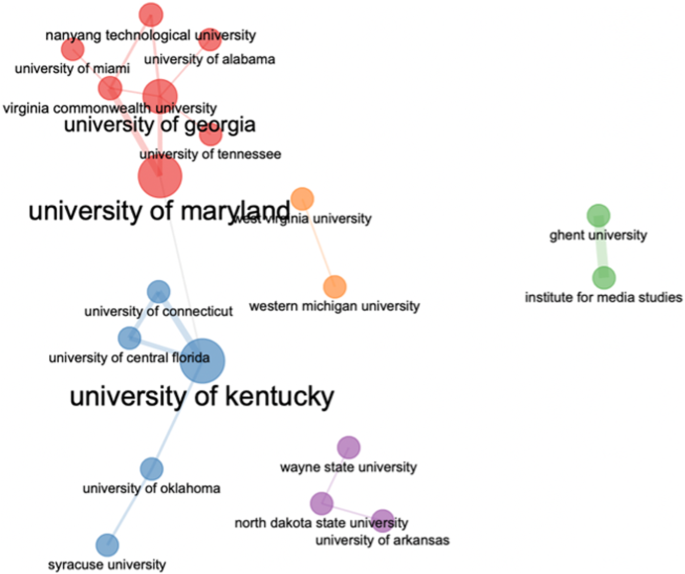

Institutions’ social structure

Figure 2 shows the collaborations among the institutions. The institutional social structure is dominated by two clusters—cluster 1 (red color) and cluster 2 (blue color)—are led by University of Maryland and University of Kentucky, respectively.

The network depicts five clusters.

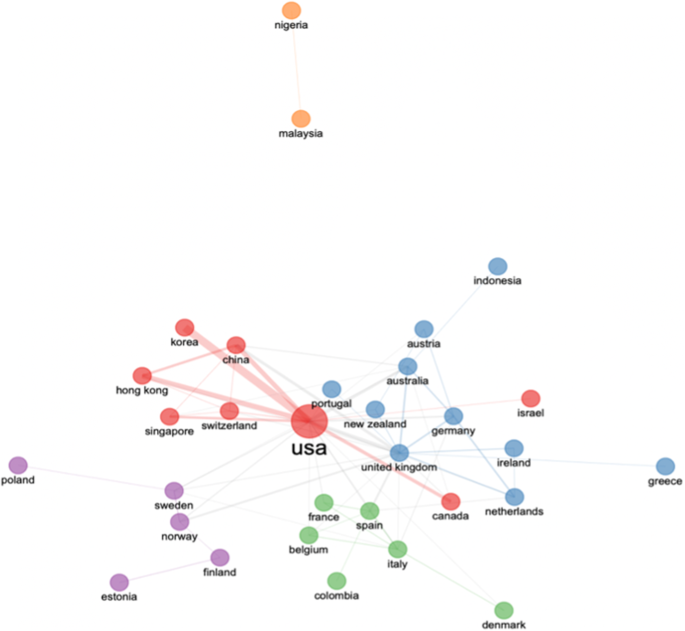

Countries’ social structure

Figure 3 depicts country-wise social collaborations. The USA leads in terms of contribution and collaboration while countries like Malaysia and Nigeria show minimal collaborations. This indicates that there is a dearth of contributions from developing economies. Thus, investigating crisis communication in this context may be considered for further research.

Social network perspective

We gathered a total of 1850 articles by 3277 authors from 1222 institutions published in 646 journals as per the set criteria. For a deeper insights, we examined the social network measures at two levels. Firstly, at the cluster level network for authors (Fig. 1 ), institutes (Fig. 2 ), and countries (Fig. 3 ). Secondly, for the complete social network for authors, institutes and countries, See Fig. S10 .

Betweenness centrality is a measure that quantifies the number of shortest routes passing through an actor in a network. Actors with high betweenness centrality play a crucial role in linking different groups together, acting as “middlemen”. In Table S9 , we observed that Liu for cluster 1, has the highest betweenness centrality (140), followed by Jin (89.7), Besides, Herovic for cluster 8, has the highest betweenness centrality (114), followed by Sellnow (104) in the studied network. This indicates that they serves as a central figure, connecting authors within the network in the field of crisis communication in Scopus from 1968 to 2022.

Furthermore, authors with a high closeness centrality are connected to all other authors through a small number of routes or paths, indicating their strong proximity to the entire network. A central author is distinguished by having numerous short connections to other authors within the network. According to the closeness centrality values presented in Table S9 where each clusters has more than 5 nodes, Liu in cluster 1, Claeys in cluster 2 and Herovic in cluster 8 exhibits the highest closeness centrality in their cluster network.

In Table S10 , we observed that University of Georgia for cluster 2, has the highest betweenness centrality (144.90), followed by University of Maryland (122.32). Besides, University of Tennessee takes the third place (112.32) in the studied network. This indicates that they serve as a central figure/point, connecting institutions within the network in the field of crisis communication in Scopus from 1968 to 2022. Furthermore, considering cluster nodes greater than 5, University of Maryland in cluster 2, and University of Kentucky in cluster 4 exhibit the highest closeness centrality in the their cluster network.

In Table S11 , we observed that USA for cluster 2, has the highest betweenness centrality (377.40), followed by United Kingdom (180.57), Besides, Italy takes the third place (68) in the studied network. This indicates that they act as a central figure, connecting country’s within the network in the field of crisis communication in Scopus from 1968 to 2022. Furthermore, considering cluster nodes greater than 5, USA in cluster 2, and “Italy” in cluster 1 exhibit the highest closeness centrality in the their cluster network.

Furthermore, when we examined the complete social network (Fig. S10 ) of authors, institutes and country based on the degree centrality, closeness and betweenness metrics, we identified significant insights and patterns. For example, as per Table S12 , among the authors listed, Lachlan has the highest author centrality score of 37, indicating a significant level of influence or importance within the field. Sellnow closely follows with a centrality score of 31, while Spence, Jin, and Claeys have scores of 34, 29, and 24, respectively. In terms of university centrality, the University of Kentucky has the highest score of 24, suggesting it holds a prominent position within the academic network. The University of Maryland and the University of Georgia share the second-highest centrality score of 20, followed by Virginia Commonwealth University with 15 and the University of Central Florida with 14. The country with the highest centrality score is the USA, with a score of 159. It is followed by the UK with a score of 91, China with 49, Australia with 41, and Spain with 37.

Based on the closeness centrality values presented in Table S13 , notable patterns emerged in the author, institutes, and country networks. In the author network, Jiu takes the lead with the highest closeness centrality score of 0.206531, closely followed by Herovic with 0.194615, Jin with 0.180714, and Sellnow and Kim with 0.171525. Shifting focus to the institutes network, the University of Maryland claims the top position with a score of 0.340000 in closeness centrality. Following closely behind is the University of Kentucky with 0.330000, the University of Tennessee with 0.325217, the University of Georgia with 0.320571, and the University of Central Florida with 0.295263. These institutions exhibit high closeness centrality, indicating their efficient access to information and strong connectivity within their respective networks. In the country network, the USA secures the highest closeness score of 0.660000, showcasing its exceptional accessibility and connectivity within the network. The United Kingdom follows closely with a score of 0.628571, demonstrating its strong network presence. Spain exhibits a score of 0.557746, Italy with 0.542466, and Australia and Sweden share a closeness score of 0.535135, all highlighting their significant connectivity and influence within the country network.

In Table S14 , a comprehensive view of betweenness centrality scores revealed significant insights into the network of authors and universities, along with their respective countries. Liu emerges as the most influential figure with the highest betweenness centrality score of 0.119048, followed closely by Sellnow with a score of 0.088435, and then Jin with 0.076288. These authors hold crucial positions, acting as central connectors within the field of crisis communication. Examining the betweenness centrality scores for universities, the University of Kentucky stands out with the highest score of 0.176513, occupying a prominent central position within the institution network. Following closely, the University of Georgia secures a score of 0.123216, and the University of Maryland follows suit with a score of 0.104022. Additionally, the University of Central Florida and the Nanyang Technological University both showcase their relevance, claiming positions in the top 5 among university betweenness centrality scores. Analyzing country betweenness centrality, the USA leads with the highest score of 0.320927, indicating its pivotal role in connecting various entities within the global network. The UK follows with a score of 0.153552, showcasing its significant influence as well. Australia, Italy, and Spain also demonstrate their bridging capacities, garnering respective scores of 0.082574, 0.058308, and 0.045895.

Conceptual structures (RQ3)

Scholars have argued the utility of keywords and co-occurrence analysis to develop prevalent themes in the underlying research field. The year wise cumulative occurrences of keywords depict dominance of “crisis communication” (Supplementary Fig. S9 ). The outcome of co-occurrence analysis is theme clusters. To explore the scientific knowledge structure of the field, in this study, a threshold of 500 author keywords was deployed. To explore the thematic evolution of crisis communication, four “time-slicing” periods were examined considering the publications growth, (Supplementary Fig. 1 ). These time periods are considered for the overall time distribution of publications: 1968–1999, 2000–2007, 2008–2014, 2015–2022. The time based thematic coverage analysis is based on four different quadrants (Cobo et al., 2012 ): motor themes, basic themes, niche themes, and emerging or disappearing themes.

First period (1968–1999)

During the period between 1968 and 1999, there is a limited development of the intellectual base depicting the emergence of only a few major themes. Crisis communication in the basic theme, plays a foundational role in defining the structure of the field during the first period. The basic theme indicates that “crisis communication” provided the foundation for exploring crisis management and issue management, which are important basic terms during this period. Advertising is identified as an emerging theme, with the focus on branding, e-communication, effective communication, image building, positioning, and reputation. The motor theme that emerges in this period is crisis focusing on crisis management and image restoration. However, this period does not identify niche themes.

During this period, several scholars have discussed the purpose and importance of reputation and advertising during crisis communication. Williams and Treadaway ( 1992 ) attribute the failure of Exxon’s crisis communication to the delay in the initial response and ineffective use of burden-sharing and scapegoating strategies. Argenti ( 1997 ), while exploring the “Dow Corning’s Breast Implant Controversy” case, identifies that the corporate (Dow Corning) failed to consider the reputation as a strategic tool during the crisis and poorly communicated with the stakeholders. Versailles ( 1999 ) argues the role of effective communication in shaping and building a reputation for Hydro-Québec’s crisis communication. Likewise, U.S. airlines gained public support and confidence after the 9/11 crisis by using timely and honest communication, and by utilizing appropriate crisis response strategies such as suffering (Coombs, 1995 ; Massey, 2005 ). Saliou ( 1994 ) advocates using an adaptive crisis communication strategy to defuse panic, avoid rumors and vulnerability, manage local and global stakeholders, and disseminate information to target groups. Advertising, on the other hand, plays a critical role in building reputation during crises (Versailles, 1999 ).

Second period (2000–2007)

The thematic focus during 2000 and 2007 indicates an expansion of the intellectual base with a diverse set of concepts.This suggests a slight paradigm shift toward recognizing crisis communication as a multi-dimensional theme. Motor themes in this period are: risk assessment, leadership, attribution, and public health. In the motor theme, public health and attribution dominate the theme. For the public health theme the focus is on the exploration of disaster communication, flu pandemic communication and terrorism management, while the attribution theme focuses on responsibility and accountability. Surprisingly, the basic themes have a large coverage focusing on corporate image, public relations, crisis communication and crisis. Crisis communication dominates the basic theme by having a larger coverage on risk communication, media relations, image repair, political communication, crisis management, and response strategies. The theme public relations focuses on crisis planning, conflict management, corporate image, and corporate communication. The presence of niche theme - attribution and emerging theme - communication strategies is also evident.

During this period, the focus is majorly on the developments of appropriate theoretical frameworks. Hearit’s ( 2001 ) theory of corporate apologia proposes the rhetorical concept of self-defense, wherein organizations are seen as possessing public characters, and this provides momentum to the term reputation. Kauffman ( 2001 ) argues that NASA’s timely, honest, and open communication regarding the Apollo 13 crisis with the public and stakeholders, bolstered its image and attracted public and congress support for further manned space explorations. Coombs ( 2007a , 2007b ) attribution theory and Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) suggest embracing the field’s evolution and the influx of empirical methods in the context of crisis communication (Arpan and Roskos-Ewoldsen, 2005 ). More emphasis is given to prescriptive, rather than descriptive methods of investigation and analysis. Attribution is directly linked to people’s need to search for causes of the event (Weiner, 1986 ), making it logical to connect crisis with attribution theory (Coombs, 2007a ). Cowden and Sellnow ( 2002 ) explores the role of attribution as part of the image restoration strategies for Northwest Airlines (NWA) in proactively reducing the culpability of the strike. Gallagher et al. ( 2007 ) argue that an organization’s decision to acknowledge its role in the crisis is vital for crisis communication and for establishing public relations. It is important to be in sync with health systems to share relevant and appropriate information. For example, Mebane et al. ( 2003 ) find that a deviation of media and information shared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) related to Anthrax caused panic. Various empirical studies have attempted a prescriptive approach to analyzing the crisis. Additionally, public segmentation in communicating (Rawlins and Bowen, 2005 ) enhances the organization’s public relations. By doing so, organizations become aware of customers’ perceptions of the crisis response, thereby offering appropriate public relations communication.

Third period (2008–2014)

In this period, the number of annually published articles increases remarkably. Seven major themes emerge and their spread is evident in the four quadrants. There is a presence of a niche theme in terms of risk and crisis communication, focusing on health communication, pandemic, flu, H1N1, influenza, and risk perception. However, strong linkages are witnessed between health communication, and response strategy. The theme risk and crisis communication focuses on organizational communication, political communication, internal communication, and corporate communication. In addition, response strategy is closely linked to organizational communication, and crisis response. The emerging theme identifies situational crisis communication as a collective theme that focuses on leadership, contingency, crisis response strategy, ethos, crisis responsibility, image repair, and threats. The basic theme is dominated by crisis communication and communication. The motor themes include corporate communication, corporate social responsibility, communications and emotions.

Avery et al. ( 2009 ) attribute crisis communication to multiple contexts (e.g., delay, use of scapegoating strategies). Crisis communication, built around the concept of corporate apologia, aims to develop rhetorical strategies to reduce reputational harm and help organizations build images and restore order (Coombs et al., 2010 ). Gallagher et al. ( 2007 ) argue that an organization’s decision to acknowledge its role in the crisis is vital for crisis communication and for establishing public relations. However, when an organization responds in a timely manner and follows transparency in communication, it attracts the trust and support of stakeholders. Identifying the type of response and understanding its consequences also plays a critical role in managing crisis communication. For example, an organization in crisis struggles to choose the correct answer as the choices vary— defensive vs. offensive, reactive vs. proactive, vague vs. transparent, etc. However, to effectively manage crisis communication, an organization must consider reputational, legal and financial outcomes (Avery et al., 2009 ). Internal communication in health organizations is critical for health practices. For example, Schmidt et al. ( 2013 ) identify a lack of correct perception of influenza by healthcare workers, thereby limiting the execution of timely vaccination. Kim and Atkinson ( 2014 ) identify critical factors such as brand ownership, exposure to media, and involvement with the crisis and consider advertising as a tool to communicate with consumers during the crisis to shape reputation.

Fourth period (2015–2022)

In this period, the field grows multidimensionally, including all the four themes. The motor theme includes COVID-19, and crisis management. The emerging theme focuses on crisis. The basic theme represents crisis communication and the emerging theme depicts the importance of public relations, and crisis. The niche theme focuses on risk communication. An interesting insight is the inclusion of the pandemic COVID-19 under the motor theme, which is strongly related to the niche theme in the earlier period. This shows that this period witnessed a dramatic shift in the themes and focal interest.

During this period, both scholars and practitioners consider the use of social media as a new-age communication tool, as it helps to offer direct and personalized communication to social media consumers. Such communication helps to shape and build reputation during a crisis. For example, Wang ( 2016 ) argues that social media is an effective crisis communication tool for turning crises into opportunities. Ho et al. ( 2017 ) propose a corporate crisis advertising framework and validate its applicability in managing and restoring an organization’s reputation. The authors also focus on the role of omni-channel (e.g., social media, print media, TV, radio) and short-, medium-, and long-term crisis communication plans to manage and shape their reputations. Additionally, Claeys and Opgenhaffen ( 2021 ) argue that to manage crisis communication effectively impact of reputational consequences and legal and financial outcomes needs to be considered. Hyland-Wood et al. ( 2021 ) argue on deploying crisis communication responses by including clear messages shared through appropriate channels and trusted sources. Such messages are customized to attract diverse audience members. Additionally, public segmentation in communicating (Rawlins and Bowen, 2005 ) enhances the organization’s public relations (Wen et al., 2021 ). By doing so, organizations become aware of customers’ perceptions of the crisis response and thereby offer appropriate public relations communication. Santosa et al. ( 2021 ) argue using varied public relations professionals’ communication strategies based on gender. Moreover, Malik et al. ( 2021 ) highlight the role of health organizations in countering misinformation on social media. They suggest that few elements such as timely and accurate information, and inclusion of credible sources help to streamline the facts.

Overall themes

Figure 4 shows the development of the four major clusters. The number of times the term is used is proportional to the size of the node. The nodes that are closely linked are the proximate nodes, while the thickness of the links connecting the nodes is proportional to the strength of the connection.

The network depicts four clusters.

Cluster 1: crisis communication and social media

The largest cluster (in red) includes 23 items and is mainly related to crisis response strategies, strategic communication, situational crisis communication, and communication on social media. The linkages to terms such as image repair, internal communication, and corporate communication may indicate that crisis communication concerns related to organizations can provide multiple co-benefits and strengthen public relations (Coombs, 2021 ; Tornero et al., 2021 ).

Cluster 2: health communication

Cluster 2 (in blue) consists of ten items and mainly covers issues related to public health and health communication. This cluster has strong links to infectious disease outbreaks, pandemics, and associated risk communication. Moreover, the inclusion of political communication to deal with the level of severity of the threat or risk is found to be critical.

Cluster 3: crisis and leadership

Cluster 3 (in green) includes ten items and focuses on two major areas: crisis and leadership. Other terms, such as disaster, risk, apology, resilience, and reputation are closely related to crisis and leadership.

Cluster 4: reputation and advertising

Cluster 4 (in purple) includes seven items and focuses on two major aspects: reputation and advertising for brand building. This cluster has strong links to corporate reputation, media, trust, advertising, and leadership. Related terms are closely linked to reputation that may indicate strategic alignment of leadership to communicate effectively (Coombs and Holladay, 2002 ).

Intellectual structure (RQ4)

In this section, we examined the intellectual collaborations patterns across three levels: author, sources, and documents. We performed the co-citation network analyses to explore the intellectual structure. Figure 5 presents two clusters that dominate the intellectual structure based on the authors. Cluster 1 (in blue color) is driven by Kim, Jin, Liu, Lee, Veil Smith, and Schultz, while cluster 2 (in red color) is driven by the contributions of Coombs, Benoit, Seeger, Heath, and Ullmer. Cluster segmentation depicts diverse dominant areas of research interests among the authors.

The network depicts two clusters.

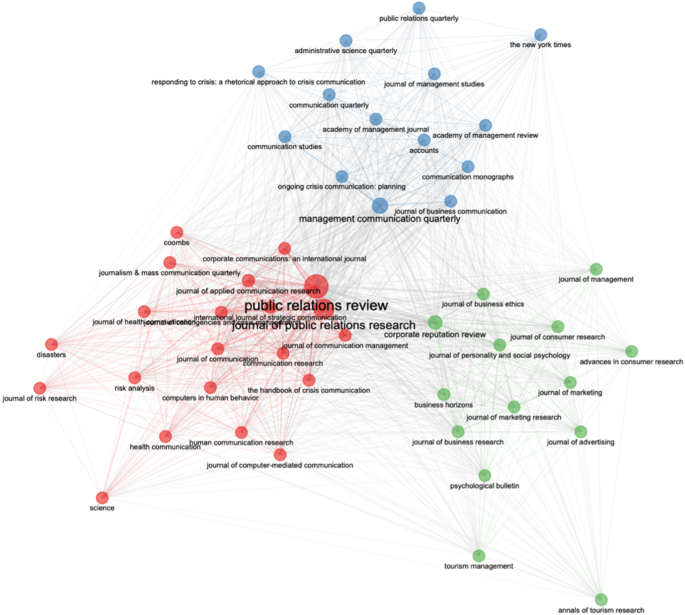

Figure 6 presents the development of three major clusters showcasing the intellectual structure of the research in crisis communication based on sources. Cluster 1 (in red color) is dominated by Public Relations Review, Journal of Public Relations Research , and Journal of Applied Communication Research . Cluster 2 (in green) is driven by Corporate Reputation review, Journal of Personality and Psychology, Journal of Business Research and Business Horizons . However, Cluster 3 (in blue), is driven by Management Communication Quarterly, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, and Journal of Business Communication .

The network depicts three clusters.

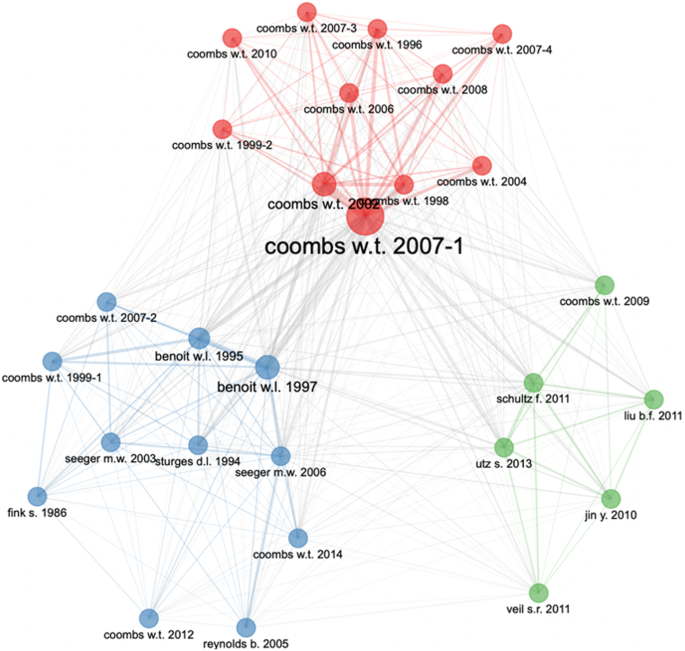

Figure 7 presents the development of three major clusters showcasing the intellectual structure of the research in crisis communication based on contributed papers. Cluster 1 (in red color) is dominated by Coombs ( 2007b ), Coombs and Holladay ( 2002 ), and Coombs ( 1998 ). Cluster 2 (in blue color) is driven by Benoit ( 1995 ), Benoit ( 1997 ), Seeger ( 2006 ) and Schultz et al. ( 2011 ). Cluster 3 (in green color) is driven by Schultz et al. ( 2011 ), Coombs ( 2009 ), and Jin ( 2010 ). The cluster segmentation depicts the diverse dominant areas of research interests among the authors.

Crisis communication is one of the most important critical elements of the communication research. The availability of large corpora of literature on crisis communication necessitated a bibliometric approach to study its evolution and growth in the communication field. We adopted bibliometric visualization techniques to understand the trajectory of crisis communication scholarship. First, we used descriptive analysis to study the prominent contributors to the field with respect to the authors, sources, institutions, and countries. We portrayed the growth trajectory and presented the trend analysis including the most productive and impactful authors, sources, countries and institutions. Second, the co-authorship analysis was done to project the social structures of the crisis communication research. This enabled us to present the social collaboration relationship of different, authors institutions and countries. Besides, we performed the analysis of social network measures to explore valuable insights into the dynamics of collaboration within the crisis communication domain. To delve deeper into the networks, we examined the cluster-level networks for authors, institutes, and countries, as well as the complete social network. The network measures (degree centrality, closeness and betweenness) shed light on the pivotal actors, institutes, and countries within the crisis communication domain, illustrating their roles as central connectors and influential figures. The findings have provided valuable insights into the collaborative landscape, facilitating a deeper understanding of the dynamics and relationships that shape the field of crisis communication in Scopus from 1968 to 2022.

Third, we performed the co-word analysis to gather concept space knowledge by utilizing the co-occurrence frequency of keywords. Subsequently, co-occurrence network analysis and clustering were used to identify clusters that represent common concepts. The keywords co-occurrence network and clusters developed the thematic mapping and thus presented the conceptual structure. Fourth, we performed the co-citation analysis of author, reference and sources to develop the intellectual structure of the field. This projected the network relationship among the authors.

Theoretical implications and roadmap for future research

This paper is one of its own kind, in which co-occurrence, co-authorship and co-citation analyses were performed to understand the growth and development of crisis communication research in the communication field. This paper presents the advantages of bibliometric analysis over the traditional methods in the study of crisis communication literature. For example, bibliometric analysis not only covers the full spectrum of the available literature, but it also objectively navigates the development of the field by exploring the social, conceptual and intellectual structures of the crisis communication research, while, traditional methods are unable to capture and synthesize large datasets of authors and articles (García-Lillo et al., 2016 ).

By utilizing bibliometric visualization, this study examines the patterns of interactions among key authors and articles; and develops clusters of research themes. The interaction patterns and relationships provide insights into the knowledge domain (Hu and Racherla, 2008 ), while clustering technique depicts key papers with similarities in topics (Chen, 2006 ). Bibliometric visualizations facilitate a display of temporal data in different colors. Additionally, a longitudinal view in the form of four quadrants provides the thematic evolution of crisis communication research and presents the evolution and growth of major themes. These projections aid researchers in identifying research boundaries and display recent themes (Chen, 2006 ).

This paper presents insights into the intellectual, social and conceptual structures of the crisis communication field. The other major contribution of the study is the formulation of the research questions which are mentioned in the methodology section. RQ1 findings identified core sources, authors, countries, publications, and affiliations to examine prominent contributors to the literature on crisis communication. We observed that 3277 authors from 1222 institutions published 1850 articles in 646 journals addressing crisis communication within more than 50 years (with the first publication being released in 1968). Though Sellnow appeared to be contributing the highest number of articles with the most extended unbroken series of publications from 1993 to 2022, Coombs received the best combination of productivity and impact (TC = 3418 and h-index = 18). Our results also corroborate with other bibliometric studies where the author’s production and impact are measured considering the number of articles published, total citations, and h-index (for example, Forliano et al., 2021 ). Moreover, among the young and influential authors the works of Claeys, Cauberghie, Kim and Lin are noteworthy. Further the annual scientific publication growth was stagnant in Period 1 and increased in Period 2. However, rapid growth was evident after 2015, in Period 4. This may be attributed to the wide availability of information channels and global events (Maal and Wilson-North, 2019 ). Public Relations Review outranks all other journals by publishing the highest number of articles (249) on crisis communication. This journal published thrice more than the number of articles published by the Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management which stood second in the list. These results are in concurrence with the earlier studies that found Public Relations Review published the highest number of articles (e.g., An and Cheng, 2010 ; Avery et al., 2010 ).

RQ2 examined the social structure of the crisis communication research domain. Borgatti et al. ( 2013 ) and Grace et al. ( 2020 ) suggest that social collaborations are majorly driven by geographic and institutional proximity. This is corroborated in the current study as well. Country collaboration depicts network of authors and we observed that the concentration of the publication corpora was within a few countries, out of which the USA depicted a huge presence. We also observed that the most productive countries do not always have high openness in collaborations. This observation should encourage more scholars to consider contributing to the present debate and enhance cross country collaborations (Massaro et al., 2016 ). We noticed that the contributions in crisis communication were fragmented despite receiving increased attention in the recent years. Hence a proper synthesis and systemization of work is potent to expand the crisis communication production and impact. We identified 11 co-author clusters depicting the most influential scholars with confined collaborations. Out of these, 6 clusters had collaborations of only two influential scholars. We observed that 28% of contributions were from single-authored publications. We suggest that more scholars should contribute to the crisis communication space. The results from the co-authorship network present the current state of collaboration and the most influential authors on crisis communication. Our evidence suggests that there is relatively little collaboration among authors, and much of this is localized. We noticed that the social structure at the level of institutions is dominated by the universities in the USA (e.g., University of Maryland and University of Kentucky). According to the social collaboration structure, the contribution of developing countries is minimal in the crisis communication space. Thus, more collaborations and empirical evidence may be solicited from the developing countries.

RQ3 explored popular themes in the crisis communication literature with the help of keywords and co-occurrence (or co-word) analysis. Overall, four major themes emerged: (a) crisis communication and social media (b) health communication, (c) crisis and leadership, and (d) reputation and advertising. The keywords related to the themes were a part of the crisis communication evolution during the study period (1968–2022). The results of our citation analysis suggest that a limited number of articles have shaped the field. We observed a clear shift in crisis communication and response strategies with the onset of omni-channels, such as social media platforms.

RQ4 examined the emergence of two main groups in the intellectual structure (co-citation analysis). Despite having a relatively low number of relational ties, they act as knowledge brokers among the groups. This may be due to closed group collaborations, and thus, better collaborative efforts among scholars are needed. Coombs ( 2007b , 2002 , 1998 ) dominate the intellectual space in terms of the document-based intellectual structure. The thematic development and its evolution are helpful for scholars, sources (journals), institutions and countries to acquire knowledge on specialized and highly relevant topics. More specifically, niche and emerging themes may address the immediate call for research and collaborations. Journals are encouraged to announce special issues on these themes. Additionally, journals may increase the number of publications as they are ranked among the most impactful ones but have relatively low number of publications.

The findings of the paper has implications for crisis communication research in terms of examining the social, conceptual and intellectual structures of the field. Given the large corpora and growth of crisis communication research over the last 50 years, Biblioshiny, serves as a useful tool to objectively capture the social and intellectual collaborations, growth and evolution of concept and knowledge space of this field (Denyer and Tranfield, 2006 ). These insights, therefore, may be extremely useful to the early scholars or researchers from outside the field (Benckendorff and Zehrer, 2013 ).

The overall findings and analysis of this paper present several opportunities for future research in the field of crisis communication. A list of potential research questions is prepared as the outcome of RQ5 which was accomplished by collating the results of RQ1, RQ2, RQ3, and RQ4.

While research opportunities are immense in crisis communication, the following research questions can be considered for further understanding, see Table 1 :

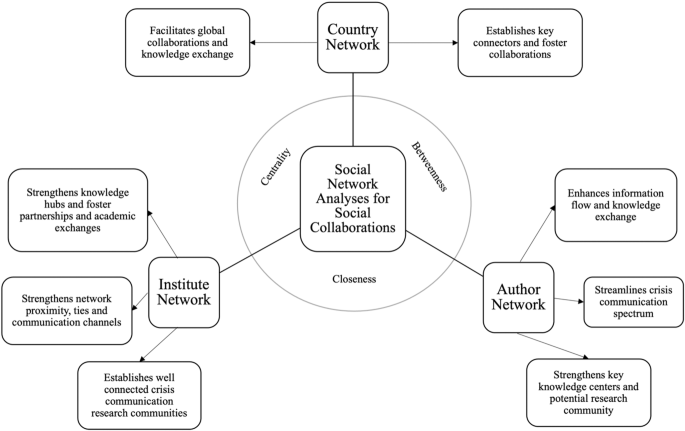

The findings from our study on social network measures at two levels, namely, cluster-level networks for authors, institutes, and countries, as well as the complete social network for authors, institutes, and countries, have provided valuable insights into the field of crisis communication from 1968 to 2022. The application of network metrics, such as degree centrality, betweenness centrality and closeness centrality, has enabled us to identify key actors, institutions, and countries that play pivotal roles in linking different entities within the crisis communication domain. Figure 8 represents the framework enhancing social collaboration based on the social network analyses.

Identifying Key Connectors: The analysis of betweenness centrality in Tables S9 , S10 , and S11 has revealed central figures, such as Liu and Herovic in the author network, University of Georgia and University of Maryland in the institute network, and USA in the country network. These individuals and entities act as “middlemen,” connecting various clusters and facilitating efficient information flow between different groups. Researchers and policymakers can leverage this insight to foster collaboration and knowledge exchange among the identified central figures, thereby enhancing crisis communication efforts globally.

Enhancing Network Proximity: Authors with high closeness centrality scores, like Liu in cluster 1, Claeys in cluster 2, and Herovic in cluster 8, have strong proximity to the entire network. Similarly, institutes with high closeness centrality scores, such as University of Maryland, University of Kentucky, and University of Tennessee, exhibit efficient access to information within their respective clusters. Policymakers and practitioners can focus on strengthening ties and communication channels among these authors and institutions to foster a more cohesive and well-connected crisis communication community.

Promoting Global Collaboration: The country network analysis based on betweenness centrality in Table S11 has highlighted the significant role of countries like the USA, United Kingdom, and Italy in connecting various nations in the crisis communication research domain. This implies that these countries have the potential to facilitate global collaboration and knowledge dissemination. Encouraging international conferences, joint research initiatives, and exchange programs can further strengthen ties between these influential countries and foster a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to crisis communication worldwide.