Our privacy statement has changed. Changes effective July 1, 2024.

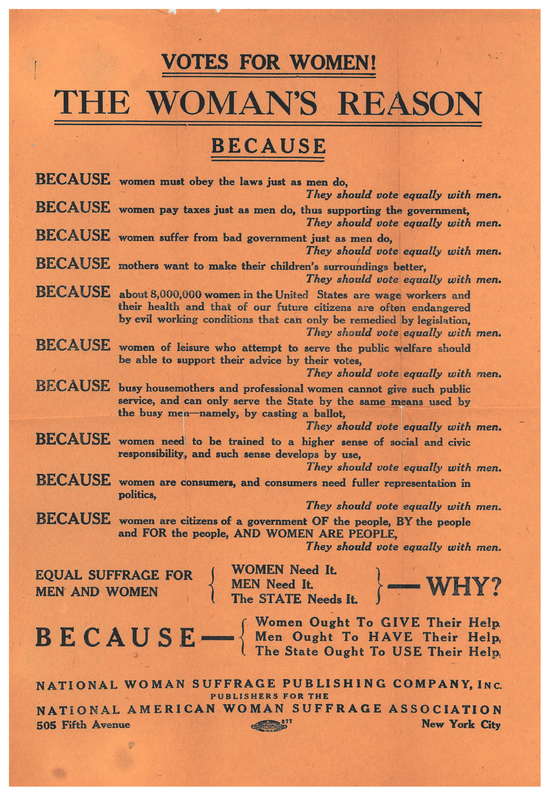

100 Years and Counting: The Fight for Women’s Suffrage Continues

One hundred years ago this month, the Nineteenth Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution, giving women the right to vote in the single largest voting rights expansion in our nation’s history. However, as we commemorate this historic centennial, we must remember that not all women got the right to vote in 1920.

To this day, women who are people of color, transgender, incarcerated or formerly incarcerated, or have disabilities continue to face barriers to voting, along with other marginalized groups. We have more work to do to ensure that all women — and all people, regardless of gender identity — are able to exercise their voting rights.

Women of color

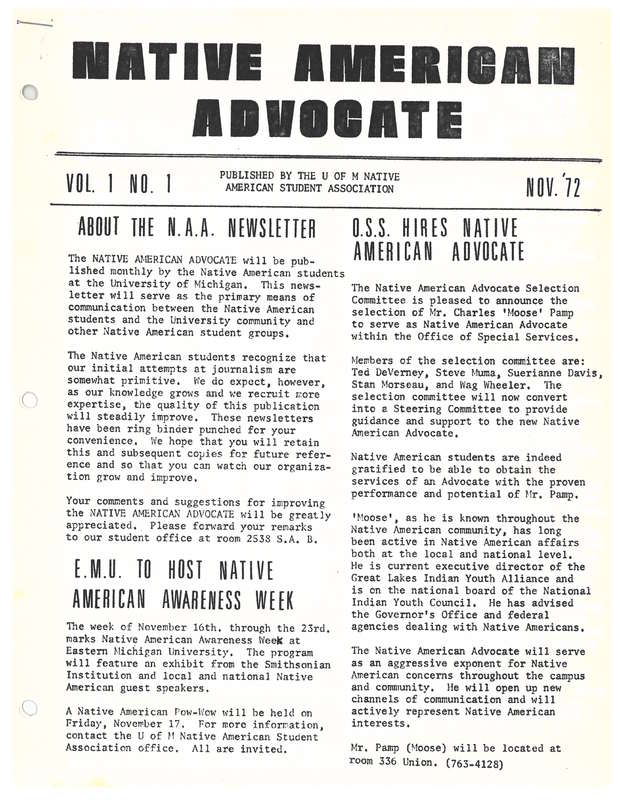

For many decades after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Black women continued to be blocked from accessing the ballot by Jim Crow-era restrictions aimed at segregating Black Americans, like poll taxes and literacy tests. Native Americans were unable to vote in all states until the 1960s, even after being federally recognized as U.S. citizens in 1924. Asian American immigrant women were unable to vote until immigration and naturalization restrictions were lifted in 1952.

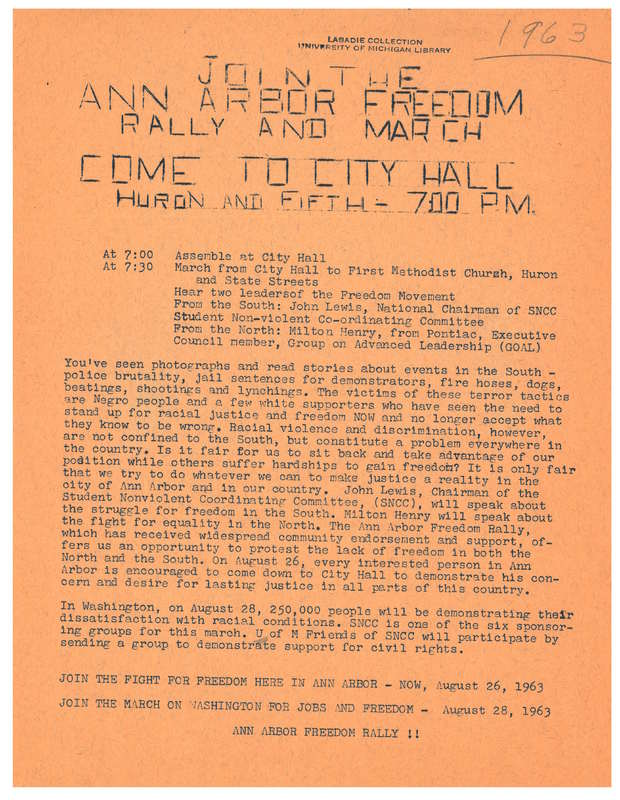

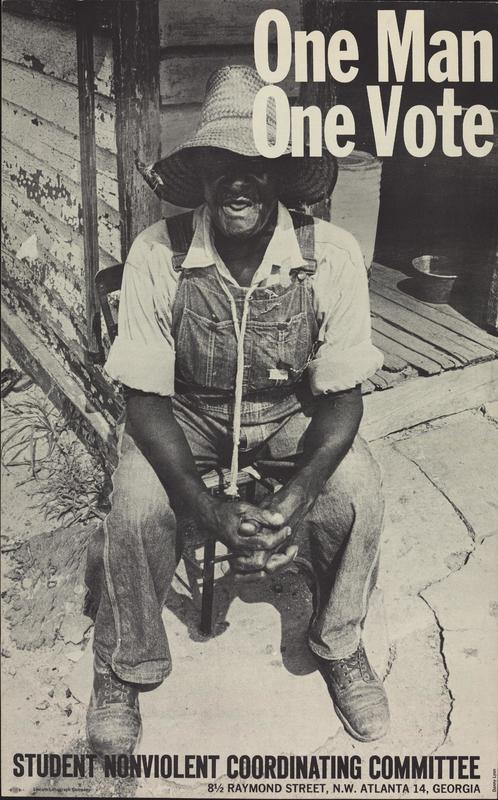

Through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Congress took action to ensure that communities of color were able to register to vote, cast their ballots, and elect representatives of their choice. However, relics of the Jim Crow era persist in our legal and electoral systems.

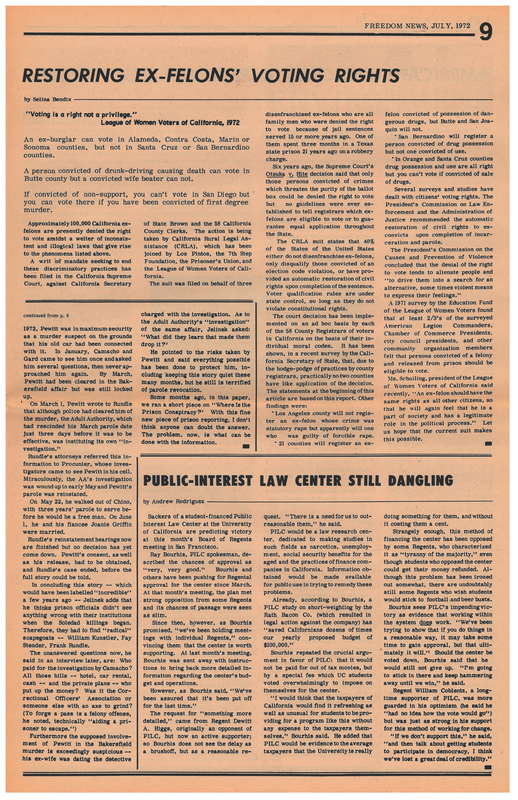

Incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women

Felony disenfranchisement laws strip voting rights from millions of people convicted of certain felonies—and can prohibit people who have felony convictions from voting while incarcerated, while on parole or on probation, or even after completing their sentence. These laws, enacted in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, were deliberately designed to target Black populations and enshrine white supremacy. Due to the racist roots of our nation’s mass incarceration crisis, the majority of those barred from voting under these laws continue to be people of color, especially Black men.

Women make up an increasing part of the population harmed by felony disenfranchisement, as their incarceration rates are growing at more than twice the rate of men. By 2017, over 1.3 million women and girls—disproportionately people of color, and from low-income communities—were incarcerated, on probation, or on parole.

Trans women and other trans and non-binary people

Trans women, and the trans and non-binary community at large, also face barriers to voting due to voter registration forms and voter ID laws that ask for gender and do not permit voters to update their names, gender markers, or photos. Currently, 36 states have voter ID laws, and 18 of those states specifically require a photo ID. Such laws pose a barrier to trans voters, for whom updating identification cards can be a significant financial and administrative burden. Even in states that do allow trans and non-binary people to correct their IDs, voters often have to jump through hoops to do so. For example, trans people in some states are required to prove that they have undergone gender confirmation surgery , even though many transgender people cannot afford it, and some do not want it as part of their gender-affirming care.

Not only do these laws block hundreds of thousands of trans people from exercising their right to vote, they also further marginalize the trans community, serving as a stark reminder that the government does not respect their identities. Furthermore, these impacts are most keenly felt by trans voters who belong to other politically-marginalized groups; data suggest that “transgender citizens are more likely to have no accurate IDs if they are young adults (age 18-24; 69 percent), people of color (48 percent), students (54 percent), those with low incomes (less than $10,000 annual household income; 60 percent), or have disabilities (55 percent).”

Even in places where there are minimal legal and policy barriers for transgender voters, voting in-person can lead to harassment or discrimination — including from poll workers.

Women with disabilities

Historically, people with certain types of disabilities have been disenfranchised by state laws that explicitly denied the right to vote to people who were assumed to lack the “mental capacity” to vote. These laws were also used to justify the continued disenfranchisement of women and the Black community. Across the country , such laws are largely still in effect. As a result, on an annual basis, tens of thousands of voters are blocked from the ballot box without any judicial determination that they lack the capacity to vote.

Voters with disabilities also continue to face architectural, attitudinal, and even digital barriers to the franchise. Recent federal studies have consistently revealed that the majority of polling places surveyed were not fully accessible. Additionally, voters with disabilities are severely underrepresented in our political system, even though they make up one-sixth of the American electorate. Voters with disabilities are also far less likely to participate in elections than their peers, partially because of feelings of political alienation that are reinforced by the barriers they face when attempting to vote. Most states have made voter registration and absentee ballot application forms or portals, in addition to critical information about voting procedures, available online. However, few state election websites have been made fully accessible to allow voters with disabilities to navigate them autonomously.

On top of these barriers, the present pandemic has created additional hurdles for voters with disabilities, many of whom have medical conditions that render them at high risk for severe illness or death if they contract COVID-19. Urban areas, precisely where people with disabilities are more likely to be women , are where the health risks of voting in-person are most acute. COVID-19 has highlighted the need for universal and accessible mail-in voting . Voters with disabilities are more likely to live alone than the general population, meaning they are less likely to be able to vote by mail in states that require a witness requirement for absentee voting. They are also far more likely to live in congregate care facilities—which have been ravaged by COVID-19 . Though residents of congregate care facilities account for only 1 percent of the U.S. population, 50 percent of all COVID-19-related deaths have occurred in those facilities.

Youth, caregivers, and immigrants

Young people, such as college students, may face difficulty meeting voter ID requirements if they go to school outside their home state. Several states prohibit students from using their student IDs to vote, and are increasing other obstacles for students, such as requiring them to prove their domicile or closing polling places on college campuses. Women are disproportionately affected by these restrictions, as the majority of students enrolled in higher education are women.

Most caregivers are also women, and specifically women of color . Roughly 85 percent of Black mothers and 60 percent of Latinx mothers are caregivers for their families as well as primary or co-breadwinners. Cutbacks to early in-person voting opportunities and lack of no-excuse absentee voting options for those seeking to vote by mail block many caregivers from accessing the ballot. Caregivers require more flexibility in voting hours and options to be able to cast their ballots.

More than 12 million immigrant women have become naturalized U.S. citizens. Naturalized citizens have lower than average electoral participation rates, partly due to lack of outreach from political campaigns, as well as widespread language access barriers. Unfortunately, because of disruptions caused by COVID-19, more than 300,000 immigrants may not complete the naturalization process in time to vote in the November election. These voters are disproportionately women, as women make up the majority of naturalized citizens from nine of the top 10 countries of origin.

The fight for suffrage continues

Since the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, several critical civil rights protections have solidified access to the ballot, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. In 2013, the Supreme Court gutted provisions of the Voting Rights Act which protected voters from discriminatory election practices. The decision cleared the path for states to pass a slew of new voter suppression laws, many of which rolled back access to the ballot for historically disenfranchised groups, including women. Meanwhile, the ADA has been woefully under-enforced in the elections context.

Today, the ACLU is actively litigating to safeguard voters’ rights. We have initiated lawsuits across the country (20 and counting) to expand access to voting by mail to ensure that voters can vote safely from their homes, protect themselves and the public at large, and minimize the risk COVID-19 transmission while exercising the fundamental right to vote. We are also going to trial next month with our partners at the Native American Rights Fund to challenge a law that severely inhibits Native Americans ’ access to the ballot.

The ACLU also went back to court this month to defend our victory protecting the voting rights of Floridians with past felony convictions. Before the historic passage of Amendment 4 in 2018, Florida was one of four states that banned voting for life for people convicted of a felony, disenfranchising more than a million people. Amendment 4 was one of the largest expansions of voting rights since the Nineteenth Amendment.

Throughout the country, activists are fighting voter suppression tactics and pushing to expand access to the ballot through the VRAA , the VoteSafe Act , and the HEROES Act . The ACLU is also advocating for the Accessible Voting Act , which would establish new protections for voters with disabilities, seniors, Indigenous voters, and language minority voters. Activists on the ground can also spread awareness with our Let People Vote educational resource on voting by mail, our Know Your Voting Rights pages, and by sharing our Let People with Disabilities Vote content.

On the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, we must remember that the law did not enfranchise all women equally and let that knowledge guide us as we march forward in our fight for voting rights.

Learn More About the Issues on This Page

- American Indian Voting

- Fighting Cuts to Voting Access

- Fighting Voter ID Requirements

- Fighting Voter Suppression

- Promoting Access to the Ballot

- The Voting Rights Act

- Voters with Disabilities

- Voting Rights

Related Content

Voting Rights Advocates Celebrate Legislative Change in Mississippi Following Voter Challenge Lawsuit

Unconstitutional Letters Sent to Naturalized Citizens Amount to Voter Intimidation

New Report: United States a Global Outlier in Denying Voting Rights Due to Criminal Convictions

Black Political Empowerment Project v. Schmidt

- News & Events

- Activities & Exhibits

- Anti-Slavery

- Biographies

- Related Websites

- Support WWHP

Enfranchisement of Women

[Editorial Note: When this essay first appeared in the Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review , one of England's premier journals of political opinion, virtually everyone attributed it to John Stuart Mill. Mill, widely recognized as one of the most eminent British economists and philosophers, later credited the essay to his wife, Harriet Taylor. (See his letter to Paulina Wright Davis included in her address to the 1870 Anniversary Convention.) Similarly, he wrote that the views expressed in his subsequent book, The Subjection of Women , also derived from Taylor. In his Autobiography he went even further, claiming that Taylor was responsible for the key ideas in most of his work. Biographers and historians have long sought to trace the parameters of Taylor's influence upon Mill, but all agree that it was both profound and exceedingly difficult to pin down. Most scholars, however, accept Mill's claim that Taylor wrote "Enfranchisement of Women."

The essay itself had a profound effect on both sides of the Atlantic, not least of all because of the (mistaken) attribution of its authorship to Mill. It gave the woman's rights movement an immediate claim to intellectual respectability at a time when most commentators, when they deigned notice the arguments of movement spokespeople, only scoffed. It also directly affected the debate over woman's rights within the fledgling movement. The resolutions adopted at the 1851 national woman's rights convention, according to Wendell Phillips who introduced them, sought to embody the essay's central contentions.

"Enfranchisement of Women" also anticipated some of the arguments that would continue to divide advocates of woman's rights down to the present such as that between so-called "difference" feminists and "equality" feminists as the following quotation demonstrates;

Like other popular movements . . . this may be seriously retarded by the blunders of its adherents. Tried by the ordinary standard of public meetings, the speeches at the [1850 Worcester] Convention are remarkable for the preponderance of the rational over the declamatory element; but there are some exceptions; and things to which it is impossible to attach any rational meaning, have found their way into the resolutions. Thus, the resolution which sets forth the claims made in behalf of women, after claiming equality in education, in industrial pursuits, and in political rights, enumerates as a fourth head of demand something under the name of "social and spiritual union," and "a medium of expressing the highest moral and spiritual views of justice," with other similar ver[P.23]biage, serving only to mar the simplicity and rationality of the other demands: resembling those who would weakly attempt to combine nominal equality between men and women with enforced distinctions in their privileges and functions. What is wanted for women is equal rights, equal admission to all social privileges; not a position apart, a sort of sentimental priesthood. . . .The strength of the cause lies in the support of those who are influenced by reason and principle; and to attempt to recommend it by sentimentalities, absurd in reason, and inconsistent with the principle on which the movement is founded, is to place a good cause on a level with a bad one.]

[Harriet Taylor], "Enfranchisement of Women," reprinted from the Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review for July 1851, Woman's Rights Tracts, . . . . No. 4 (Syracuse, 1852 or 1853) as excerpted.

P.1: Most of our readers will probably learn from these pages [ New-York Tribune, For Europe , October 29, 1850], for the first time, that there has arisen in the United States, and in the most enlightened and civilized portion of them, an organized agitation on a new question--new, not to thinkers, nor to any one by whom the principles of free and popular government are felt as well as acknowledged, but new, and even unheard of, as a subject for public meetings and practical political action. This question is, the enfranchisement of women; their admission, in law and in fact, to equality in all rights, political, civil and social, with the male citizens of the community.

It will add to the surprise with which many will receive this intelligence, that the agitation which has commenced is not a pleading by male writers and orators for women, those who are professedly to be benefitted remaining either indifferent or ostensibly hostile; it is a political movement, practical in its objects, carried on in a form which denotes an intention to preserve. And it is a movement not merely for women , but by them. Its first public manifestation appears to have been a Convention of Women, held in the State of Ohio, in the Spring of 1850. Of this meeting we have seen no report. On the 23rd and 24th of October last, a succession of public meetings was held at Worcester, in Massachusetts, under the name of a "Women's [sic] Rights Convention, of which the President was a woman [Paulina Wright Davis], and nearly all the chief speakers women; numerously reinforced, however, by men among whom were some of the most distinguished leaders in the kindred cause of negro emancipation. A general, and four special committees were nominated, for the purpose of carrying on the undertaking until the next annual meeting.

. . . . . . . . .

P.2: . . . In regard to the quality of the speaking, the proceedings bear an advantageous comparison with those of any popular movement with which we are acquainted, either in this country or in America. Very rarely, in the oratory of public meetings, is the part of verbiage and declamation so small, that of calm good sense and season so considerable. The result of the Convention was, in every respect, encouraging to those by whom it was summoned; and it is probably destined to inaugurate one of the most important of the movements towards political and social reform, which are the best characteristics of the present age.

That the promoters of this new agitation take their stand on principles, and do not fear to declare these in their widest extent, without time serving or compromise, will be seen from the resolutions adopted by the Convention . . . .[here follows a partial transcription of the resolutions. For the full text, see the Proceedings .]

It would be difficult to put so much true, just, and reasonable meaning into a style so little calculated to recommend it as that of some [P.3] of the resolutions. But whatever objection may be made to some of the expressions, none, in our opinion, can be made to the demands themselves. As a question of justice, the case seems to us too clear for dispute. As one of expediency, the more thoroughly it is examined the stronger it will appear.

. . . . . . . .

P.3: . . . After a struggle which, by many of its incidents, deserves the name heroic, the abolitionists are now so strong in numbers and influence, that they hold the balance of parties in the United States. It was fitting that the men whose names will remain associated with the extirpation, from the democratic soil of America, of the aristocracy of color, should be among the originators, for America and for the rest of the world, of the first collective protest against the aristocracy of sex; a distinction as accidental as that of color, and fully as irrelevant to all questions of government.

. . . . . . .

P. 5: . . While, far from being expedient, we are firmly convinced that the division of mankind into two castes, one born to rule over the other, is in this case, as in all cases, an unqualified mischief; a source of perversion and demoralization, both to the favored class, and to those at whose expense they are favored; producing none of the good which it is the custom to ascribe to it, and forming a bar, almost insuperable while it lasts, to any really vital improvement, either in the character or in the social condition of the human race.

P. 6: . . . Throughout history, the nations, races, classes, which found themselves the strongest, either in muscles, in riches, or in military discipline, have conquered and held in subjection the rest. If, even in the most improved nations, the law of the sword is at last discountenanced as unworthy, it is only since the calumniated eighteenth century. 1 Wars of conquest have only ceased since democratic revolutions began. The world is very young, and has only just begun to cast off injustice. It is only now getting rid of negro slavery. It is only now getting rid of monarchial despotism. It is only now getting rid of hereditary feudal nobility. It is only now getting rid of disabilities on the grounds of religion. 2 It is only beginning to treat any men as citizens, except the rich and a favored portion of the middle class. 3 Can we wonder that it has not yet done as much for women? As society was constituted until the last few generations, inequality was its very basis; association grounded on equal rights scarcely existed; to be equals was to be enemies; two persons could hardly cooperate in anything, or meet in any amicable relation, without the law's appointing that one of them should be the superior of the other. Mankind have outgrown this state, and all things now tend to substitute, as the general principle of human relations, a just equality, instead of the dominion of the strongest. But of all relations, that be[P. 7]tween men and women being the nearest and most intimate, and connected with the greatest number of strong emotions, was sure to be the last to throw off the old rule and receive the new; for in proportion to the strength of a feeling, is the tenacity with which it clings to the forms and circumstances with which it has even accidentally become associated.

When a prejudice, which has any hold on the feelings, finds itself reduced to the unpleasant necessity of assigning reasons, it thinks it has done enough when it has re-asserted the very point in dispute, in phrases with appeal to the pre-existing feeling. Thus, many persons think they have sufficiently justified the restrictions on women's field of action, when they have said that the pursuits from which women are excluded are unfeminine , and that the proper sphere of women is not politics or publicity, but private and domestic life.

P. 9: Concerning the fitness, then, of women for politics, there can be no question: but the dispute is more likely to turn upon the fitness of politics for women. When the reasons alleged for excluding women from active life in all its higher departments, are stripped of their garb of declamatory phrases, and reduced to the simple expression of meaning, they seem to be mainly three: the incompatibility of active life with maternity, and the cares of a household; secondly, its alleged hardening effect on the character; and thirdly, the inexpediency of making an addition to the already excessive pressure of competition in every kind of professional or lucrative employment.

The first, the maternity argument, is usually laid most stress upon: although (it needs hardly be said) this reason, if it be one, can apply only to mothers. It is neither necessary nor just to make imperative on women that they shall be either mothers or nothing; or that if they have been mothers once, they shall be nothing else during the whole remainder of their lives.

P. 10: . . . There is no inherent reason or necessity that all women should voluntarily choose to devote their lives to one animal function and its consequences. Numbers of women are wives and mothers only because there is no other career open to them, no other occupation for their feelings or their activities. Every improvement in their education and enlargement of their faculties--everything which renders them more qualified for any other mode of life, increases the number of those to whom it is an injury and an oppression to be denied the choice.

But secondly, it is urged, that to give the same freedom of occupation to women as to men, would be an injurious addition to the crowd of competitors, by whom the avenues to almost all kinds of employment are choked up, and its remuneration depressed. This argument, it is to be observed, does not reach the political question. It gives no excuse for withholding from women the rights of citizenship. . . . Even if every woman, as matters now stand, had a claim on some man for support, how infinitely preferable is it that part of the income should be of the woman's earning, even if the aggregate sum were but little increased by it, rather than that she should be compelled to stand aside in order that men may be the sole earners, and the sole dispensers of what is earned.

P. 11: the third objection to the admission of women to political or professional life, its alleged hardening tendency, belongs to an age now past, and is scarcely to be comprehended by people of the present time. There are still, however, persons who say that the world and its avocations render men selfish and unfeeling; that the struggles, rivalries and collisions of business and of politics make them harsh and unamiable; that if half the species must unavoidably be given up to these things, it is the more necessary that the other half should be kept free from them; that to preserve women from the bad influences of the world, is the only chance of preventing men from being wholly given up to them.

P. 12: . . . in the present condition of human life, we do not know where those hardening influences are to be found, to which men are subject, and from which women are at present exempt. Individuals now-a-days are seldom called upon to fight hand to hand, even with peaceful weapons; personal enmities and rivalries count for little in worldly transactions; the general pressure of circumstances, not the adverse will of individuals, is the obstacle men now have to make head against. That pressure, when excessive, breaks the spirit, and cramps and sours the feelings, but not less of women than of men, since they suffer certainly not less from its evils.

P. 12: But, in truth, none of these arguments and considerations touch the foundations of the subject. The real question is, whether it is right and expedient that one-half of the human race should pass through life in a state of forced subordination to the other half. . . .

When, however, we ask why the existence of one-half the species should be merely ancillary to that of the other--why each woman should be a mere appendage to a man, allowed to have no interests of her own, that there may be nothing to compete in her mind with his [P. 13] interests and his pleasure; the only reason which can be given is, that men like it. It is agreeable to them that men should live for their own sake, women for the sake of men; and the qualities and conduct in subjects which are agreeable to rulers, they succeed for a long time in making the subjects themselves consider as their appropriate virtues.

P. 16: . . . Our argument here brings us into collision with what may be termed the moderate reformers of the education of women; a sort of persons who cross the path of improvement on all great questions; those who would maintain the old bad principles, mitigating their consequences. These say, that women should be, not slaves, nor servants, but companions; and educated for that office; (they do not say that men should be educated to be the companions of women). But since uncultivated women are not suitable companions for cultivated men, and a man who feels interest in things above and beyond the family circle, wishes that his companion should sympathize with him in that interest; they therefore say, let women improve their understanding and taste, acquire general knowledge, cultivate poetry, art, even coquet with science, and some stretch their liberality so far as to say, inform themselves on politics; not as pursuits, but sufficiently to feel an interest in the subjects, and to be capable of holding a conversation on them with the husband, or at least of understanding and imbibing his wisdom. Very agreeable to him, no doubt, but unfortunately the reverse of improving. . . . The modern, and what are regarded as the improved and enlightened modes of education of women, abjure, as far as words go, an education of mere show, and profess to aim at solid instruction, but mean by that expression, superficial information on solid subjects. Except accomplishments, 4 which are now generally regarded as to be taught well, if taught at all, nothing is taught to women thoroughly. Small portions only of what is attempted to teach thoroughly to boys, are the whole of what it is intended or desired to teach to women. What makes intelligent beings is the power of thought; the stimuli which call forth that power are the interest and dignity of thought itself, and a field for its practical application. Both motives are cut off from those who are told from infancy that thought, [P. 17] and all its greater applications, are other people's business, while theirs is to make themselves agreeable to other people. High mental powers in women will be but an exceptional accident, until every career is open to them, and until they, as well as men, are educated for themselves and for the world -not one sex for the other.

P. 17: The common opinion is, that whatever may be the case with the intellectual, the moral influence of women over men is almost always salutary. It is, we are often told, the great counteractive of selfishness. However the case may be as to personal influence, the influence of the position tends eminently to selfishness. The most insignificant of men, the man who can obtain influence or consideration nowhere else, finds one place where he is chief and head. There is one person, often greatly his superior in understanding, who is obliged to consult him, and whom he is not obliged to consult. He is judge, magistrate, ruler, over their joint concerns; arbiter of all differences between them. . . . The generous mind, in such a situation, makes the balance incline against his own side . . . . But how is it when average men are invested with this power, without [P. 18] reciprocity and without responsibility? Give such a man the idea that he is first in law and in opinion--that to will is his part, and hers to submit; it is absurd to suppose that this idea merely glides over his mind, without sinking in, or having any effect on his feelings and practice. . . .If there is any self-will in the man, he becomes either the conscious or unconscious despot of his household. The wife, indeed, often succeeds in gaining her objects, but it is by some of the many various forms of indirectness and management.

Thus the position is corrupting equally to both; in the one it produces the vices of power, in the other those of artifice. Women, in their present physical and moral state, having stronger impulses, would naturally be franker and more direct than men; yet all the old saws and traditions represent them as artful and dissembling. Why? Because their only way to their objects is by indirect paths. In all countries where women have strong wishes and active minds, this consequence is inevitable; and if it is less conspicuous in England than in some other places, it is because English women, saving occasional exceptions, have ceased to have either strong wishes or active minds.

P. 22: . . .In the United States at least, there are women, seemingly numerous, and now organized for action on the public mind, who demand equality in the fullest acceptation [sic] of that word, and demand it by a straight-forward appeal to men's sense of justice, not plead for it with a timid deprecation of their displeasure.

Like other popular movements, however, this may be seriously retarded by the blunders of its adherents. Tried by the ordinary standard of public meetings, the speeches at the Convention are remarkable for the preponderance of the rational over the declamatory element; but there are some exceptions; and things to which it is impossible to attach any rational meaning, have found their way into the resolutions. Thus, the resolution which sets forth the claims made in behalf of women, after claiming equality in education, in industrial pursuits, and in political rights, enumerates as a fourth head of demand something under the name of "social and spiritual union," and "a medium of expressing the highest moral and spiritual views of justice," with other similar ver[P.23]biage, serving only to mar the simplicity and rationality of the other demands: resembling those who would weakly attempt to combine nominal equality between men and women with enforced distinctions in their privileges and functions. What is wanted for women is equal rights, equal admission to all social privileges; not a position apart, a sort of sentimental priesthood. . . .The strength of the cause lies in the support of those who are influenced by reason and principle; and to attempt to recommend it by sentimentalities, absurd in reason, and inconsistent with the principle on which the movement is founded, is to place a good cause on a level with a bad one.

There are indications that the example of America will be followed on this side of the Atlantic; and the first step has been taken in that part of England where every serious movement in the direction of political progress has its commencement--the manufacturing districts of the North. On the 13 of February, 1851, a petition of women, agreed to by a public meeting at Sheffield, and claiming the elective franchise, was presented to the House of Lords by the Earl of Carlisle.

1 The reference is to the American and French Revolutions.

2 A reference to the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1832 by which Parliament extended limited freedom of religion to Catholics and repealed the provisions barring them from holding public office.

3 In 1833 Parliament passed a Reform Bill which extended the franchise to males who met a specified property qualification.

4 A reference to the teaching of subjects such as drawing and music in schools for women.

30 Elm Street - Worcester, MA 01609 - [email protected]

Copyright ©2023, Worcester Women's History Project

Access and Info for Institutional Subscribers

Harriet taylor mill's " the enfranchisement of women".

The Enfranchisement of Women was written by Harriet Taylor Mill and published by the Westminster Review in July 1851. This essay was considered one of the most significant texts in feminine history as it came out during the early English feminist movement where concerns over women’s employment, education and legal status in society were brought up (Hackleman 274). Through this published work, Mill advocated for the “enfranchisement of women; their admission, in law and in fact, to equality in all rights, political, civil, and social, with the male citizens of the community”(Mill 3). Mill made several important points throughout her work and one of the issues she brought up was that the present conditions did not allow women the opportunity to live according to their “nature” or desires since they were deprived of rights such as legal rights. She brought up the issue of women being excluded from common rights of citizenship, bringing up an example of British law that claims, “all persons should be tried by their peers; yet women whenever tried, are tried by male judges and a male jury” (Mill 6). The lack of freedom for women also forced them to become wives and mothers because these were the only options that they had. Mill brought up the argument that women were largely oppressed because of the maternal and care-taking responsibilities placed upon them, which was another way that women were deprived of being able to live according to their “nature”. Mill also advocated for women to have the ability to participate in the work force and public life, stating how women would prefer that that part of the income would be from their own doing (Miller). Mill believed that women deserved the same educational rights as men. Women were expected to take care of their families and also encourage their husbands’ moral and intellectual developments. If women did not go to school, they would not be able to support their husbands and families in general.

Mill also brought up the situation of the lower class and claimed that, “nothing will refine and elevate the lower classes but the elevation of women to perfect equality” (Mill 24). Mill claimed that the working-class women suffered the most as the law denied them property and control over earnings and at the same time, she brought up the idea of violence. She argued that lower-class women were the biggest victims of domestic violence and the unjust law (Deutscher 139). In The Enfranchisement of Women , Mill made it clear that the freedom of women was part of the general progress of England during the 19 th century in general. She pointed out that, “for the interest, therefore, not only of women but of men, and of human improvement in the widest sense, the emancipation of women...cannot stop where it is (Mill 19 ). Mill’s work represented a beginning in the improvement of women’s rights condition in 19 th century England and this issue was only further escalated by future feminists and supporters for better women’s rights. There was debate over whether Harriet Taylor Mill was the main author of this work because she had collaborated with her husband, John Stuart Mill on several works and many of the ideas in this essay were similar to her husband’s essay, The Subjection of Women , but despite conflicting evidence, there was a general consensus that Harriet was the article’s main author since many of the views in the essay corresponded to her radical view of gender roles (Miller). Although Mill was not given the full credit at first and her work was relatively unknown, she was still able to make a big contribution to women’s rights. Her radical views shown through The Enfranchisement of Women and she gave a very clear and rational analysis of the oppression and coercion that women faced in a time when they were considered nothing compared to men and were only defined by their reproductive and care-taking responsibilities (Deutscher 278). Harriet Taylor Mill was able to use this essay to help encourage women to fight for their rights and place in society.

Works Cited:

Deutscher, Penelope. “When Feminism Is ‘High’ and Ignorance Is ‘Low’: Harriet Taylor Mill

on the Progress of the Species.” Hypatia, vol. 21, no. 3, 2006, pp. 136–150. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/3810955. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020 .

Hackleman, Leah D. “Suppressed Speech: The Language of Emotion in Harriet Taylor’s The

Enfranchisement of Women.” Women’s Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal , vol. 20, no. 3–

4, 1992, pp. 273–286. EBSCOhost , doi:10.1080/00497878.1992.9978913.

Mill, Harriet Hardy Taylor. Enfranchisement of Women . 1868. JSTOR ,

jstor.org/stable/10.2307/60203575. Accessed 20 Sept. 2020.

Miller, Dale E., "Harriet Taylor Mill", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018

Edition) , Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL =

< https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/harriet-mill/ >.

“Portait of Harriet Taylor Mill” Wikimedia Commons, London’s National Portrait Gallery,

https://www.college.columbia.edu/core/content/harriet-taylor-mill . Accessed 21 Sept. 2020.

Associated Place(s)

Event date:.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

19th Amendment

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 9, 2022 | Original: March 5, 2010

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted American women the right to vote, a right known as women’s suffrage , and was ratified on August 18, 1920, ending almost a century of protest. In 1848, the movement for women’s rights launched on a national level with the Seneca Falls Convention , organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott .

Following the convention, the demand for the vote became a centerpiece of the women’s rights movement. Stanton and Mott, along with Susan B. Anthony and other activists, raised public awareness and lobbied the government to grant voting rights to women. After a lengthy battle, these groups finally emerged victorious with the passage of the 19th Amendment .

Despite the passage of the amendment and the decades-long contributions of Black women to achieve suffrage , poll taxes, local laws and other restrictions continued to block women of color from voting . Black men and women also faced intimidation and often violent opposition at the polls or when attempting to register to vote. It would take more than 40 years for all women to achieve voting equality.

Women’s Suffrage

During America’s early history, women were denied some of the basic rights enjoyed by male citizens.

For example, married women couldn’t own property and had no legal claim to any money they might earn, and no female had the right to vote. Women were expected to focus on housework and motherhood, not politics.

The campaign for women’s suffrage was a small but growing movement in the decades before the Civil War . Starting in the 1820s, various reform groups proliferated across the U.S. including temperance leagues , the abolitionist movement and religious groups. Women played a prominent role in a number of them.

Meanwhile, many American women were resisting the notion that the ideal woman was a pious, submissive wife and mother concerned exclusively with home and family. Combined, these factors contributed to a new way of thinking about what it meant to be a woman and a citizen in the United States.

Seneca Falls Convention

It was not until 1848 that the movement for women’s rights began to organize at the national level.

In July of that year, reformers Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, New York (where Stanton lived). More than 300 people—mostly women, but also some men—attended, including former African-American slave and activist Frederick Douglass .

In addition to their belief that women should be afforded better opportunities for education and employment, most of the delegates at the Seneca Falls Convention agreed that American women were autonomous individuals who deserved their own political identities.

Declaration of Sentiments

A group of delegates led by Stanton produced a “Declaration of Sentiments” document, modeled after the Declaration of Independence , which stated: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

What this meant, among other things, was that the delegates believed women should have the right to vote.

Following the convention, the idea of voting rights for women was mocked in the press and some delegates withdrew their support for the Declaration of Sentiments. Nonetheless, Stanton and Mott persisted—they went on to spearhead additional women’s rights conferences and they were eventually joined in their advocacy work by Susan B. Anthony and other activists.

National Suffrage Groups Established

With the onset of the Civil War, the suffrage movement lost some momentum, as many women turned their attention to assisting in efforts related to the conflict between the states.

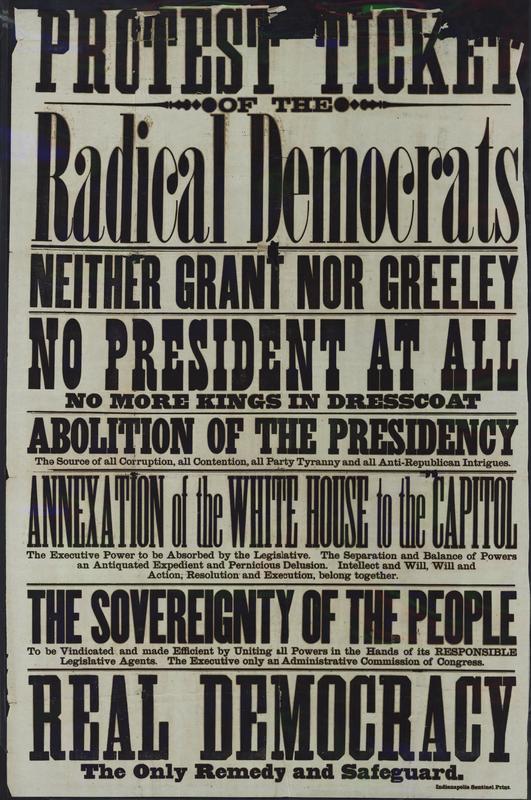

After the war, women’s suffrage endured another setback, when the women’s rights movement found itself divided over the issue of voting rights for Black men. Stanton and some other suffrage leaders objected to the proposed 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution , which would give Black men the right to vote, but failed to extend the same privilege to American women of any skin color.

In 1869, Stanton and Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) with their eyes on a federal constitutional amendment that would grant women the right to vote.

That same year, abolitionists Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA); the group’s leaders supported the 15th Amendment and feared it would not pass if it included voting rights for women. ( The 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870. )

The AWSA believed women’s enfranchisement could best be gained through amendments to individual state constitutions. Despite the divisions between the two organizations, there was a victory for voting rights in 1869 when the Wyoming Territory granted all-female residents age 21 and older the right to vote. (When Wyoming was admitted to the Union in 1890, women’s suffrage remained part of the state constitution.)

By 1878, the NWSA and the collective suffrage movement had gathered enough influence to lobby the U.S. Congress for a constitutional amendment. Congress responded by forming committees in the House of Representatives and the Senate to study and debate the issue. However, when the proposal finally reached the Senate floor in 1886, it was defeated.

In 1890, the NWSA and the AWSA merged to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The new organization’s strategy was to lobby for women’s voting rights on a state-by-state basis. Within six years, Colorado, Utah and Idaho adopted amendments to their state constitutions granting women the right to vote. In 1900, with Stanton and Anthony advancing in age, Carrie Chapman Catt stepped up to lead NAWSA.

Black Women in the Suffrage Movement

During debate over the 15th Amendment, white suffragist leaders like Stanton and Anthony had argued fiercely against Black men getting the vote before white women. Such a stance led to a break with their abolitionist allies, like Douglass, and ignored the distinct viewpoints and goals of Black women, led by prominent activists like Sojourner Truth and Frances E.W. Harper , fighting alongside them for the right to vote.

As the fight for voting rights continued, Black women in the suffrage movement continued to experience discrimination from white suffragists who wanted to distance their fight for voting rights from the question of race.

Pushed out of national suffrage organizations, Black suffragists founded their own groups, including the National Association of Colored Women Clubs (NACWC), founded in 1896 by a group of women including Harper, Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells-Barnett . They fought hard for the passage of the 19th Amendment, seeing the women’s right to vote as a crucial tool to winning legal protections for Black women (as well as Black men) against continued repression and violence.

State-level Successes for Voting Rights

The turn of the 20th century brought renewed momentum to the women's suffrage cause. Although the deaths of Stanton in 1902 and Anthony in 1906 appeared to be setbacks, the NASWA under the leadership of Catt achieved rolling successes for women’s enfranchisement at state levels.

Between 1910 and 1918, the Alaska Territory, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota and Washington extended voting rights to women.

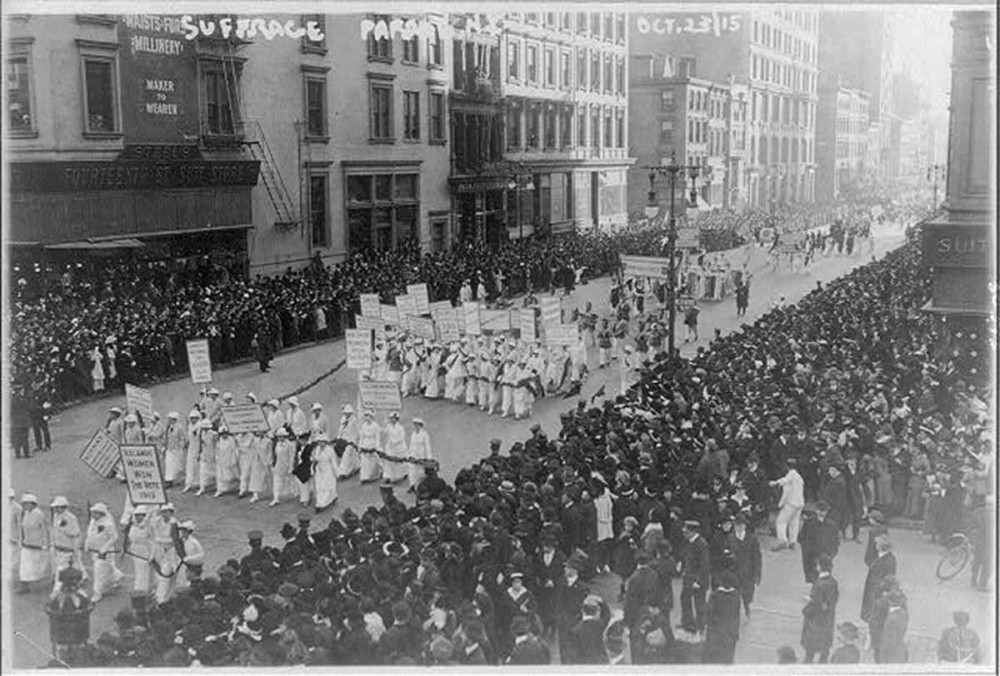

Also during this time, through the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women (later, the Women’s Political Union), Stanton’s daughter Harriot Stanton Blatch introduced parades, pickets and marches as means of calling attention to the cause. These tactics succeeded in raising awareness and led to unrest in Washington, D.C.

Did you know? Wyoming, the first state to grant voting rights to women, was also the first state to elect a female governor. Nellie Tayloe Ross (1876-1977) was elected governor of the Equality State—Wyoming's official nickname—in 1924. And from 1933 to 1953, she served as the first woman director of the U.S. Mint.

Protest and Progress

On the eve of the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson in 1913, protesters thronged a massive suffrage parade in the nation’s capital, and hundreds of women were injured. That same year, Alice Paul founded the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, which later became the National Woman’s Party.

The organization staged numerous demonstrations and regularly picketed the White House , among other militant tactics. As a result of these actions, some group members were arrested and served jail time.

In 1918, President Wilson switched his stand on women’s voting rights from objection to support through the influence of Catt, who had a less-combative style than Paul. Wilson also tied the proposed suffrage amendment to America’s involvement in World War I and the increased role women had played in the war efforts.

When the amendment came up for vote, Wilson addressed the Senate in favor of suffrage. As reported in The New York Times on October 1, 1918, Wilson said, “I regard the extension of suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged.”

However, despite Wilson’s newfound support, the amendment proposal failed in the Senate by two votes. Another year passed before Congress took up the measure again.

The Final Struggle For Passage

On May 21, 1919, U.S. Representative James R. Mann, a Republican from Illinois and chairman of the Suffrage Committee, proposed the House resolution to approve the Susan Anthony Amendment granting women the right to vote. The measure passed the House 304 to 89—a full 42 votes above the required two-thirds majority.

Two weeks later, on June 4, 1919, the U.S. Senate passed the 19th Amendment by two votes over its two-thirds required majority, 56-25. The amendment was then sent to the states for ratification.

Within six days of the ratification cycle, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin each ratified the amendment. Kansas, New York and Ohio followed on June 16, 1919. By March of the following year, a total of 35 states had approved the amendment, just shy of the three-fourths required for ratification.

Southern states were adamantly opposed to the amendment, however, and seven of them—Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, South Carolina and Virginia—had already rejected it before Tennessee’s vote on August 18, 1920. It was up to Tennessee to tip the scale for woman suffrage.

The outlook appeared bleak, given the outcomes in other Southern states and given the position of Tennessee’s state legislators in their 48-48 tie. The state’s decision came down to 23-year-old Representative Harry T. Burn, a Republican from McMinn County, to cast the deciding vote.

Although Burn opposed the amendment, his mother convinced him to approve it. Mrs. Burn reportedly wrote to her son: “Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt put the ‘rat’ in ratification.”

With Burn’s vote, the 19th Amendment was fully ratified.

When Did Women Get the Right to Vote?

On August 26, 1920, the 19th Amendment was certified by U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby, and women finally achieved the long-sought right to vote throughout the United States.

On November 2 of that same year, more than 8 million women across the U.S. voted in elections for the first time.

It took over 60 years for the remaining 12 states to ratify the 19th Amendment. Mississippi was the last to do so, on March 22, 1984.

What Is the 19 Amendment?

The 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote, and reads:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

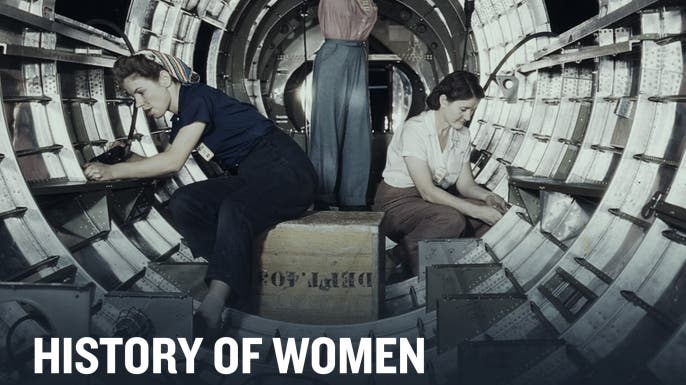

HISTORY Vault: Women's History

Stream acclaimed women's history documentaries in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

THE AMERICAN YAWP

20. the progressive era.

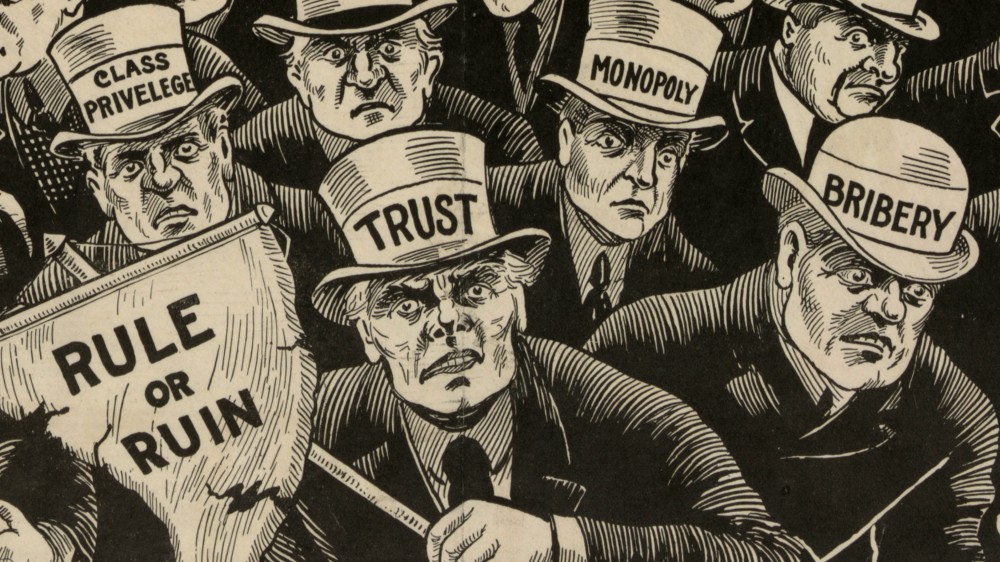

From an undated William Jennings Bryan campaign print, “Shall the People Rule?” Library of Congress .

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

Ii. mobilizing for reform, iii. women’s movements, iv. targeting the trusts, v. progressive environmentalism, vi. jim crow and african american life, vii. conclusion, viii. primary sources, ix. reference material.

“Never in the history of the world was society in so terrific flux as it is right now,” Jack London wrote in The Iron Heel , his 1908 dystopian novel in which a corporate oligarchy comes to rule the United States. He wrote, “The swift changes in our industrial system are causing equally swift changes in our religious, political, and social structures. An unseen and fearful revolution is taking place in the fiber and structure of society. One can only dimly feel these things, but they are in the air, now, today.” 1

The many problems associated with the Gilded Age—the rise of unprecedented fortunes and unprecedented poverty, controversies over imperialism, urban squalor, a near-war between capital and labor, loosening social mores, unsanitary food production, the onrush of foreign immigration, environmental destruction, and the outbreak of political radicalism—confronted Americans. Terrible forces seemed out of control and the nation seemed imperiled. Farmers and workers had been waging political war against capitalists and political conservatives for decades, but then, slowly, toward the end of the nineteenth century a new generation of middle-class Americans interjected themselves into public life and advocated new reforms to tame the runaway world of the Gilded Age.

Widespread dissatisfaction with new trends in American society spurred the Progressive Era, named for the various progressive movements that attracted various constituencies around various reforms. Americans had many different ideas about how the country’s development should be managed and whose interests required the greatest protection. Reformers sought to clean up politics; Black Americans continued their long struggle for civil rights; women demanded the vote with greater intensity while also demanding a more equal role in society at large; and workers demanded higher wages, safer workplaces, and the union recognition that would guarantee these rights. Whatever their goals, reform became the word of the age, and the sum of their efforts, whatever their ultimate impact or original intentions, gave the era its name.

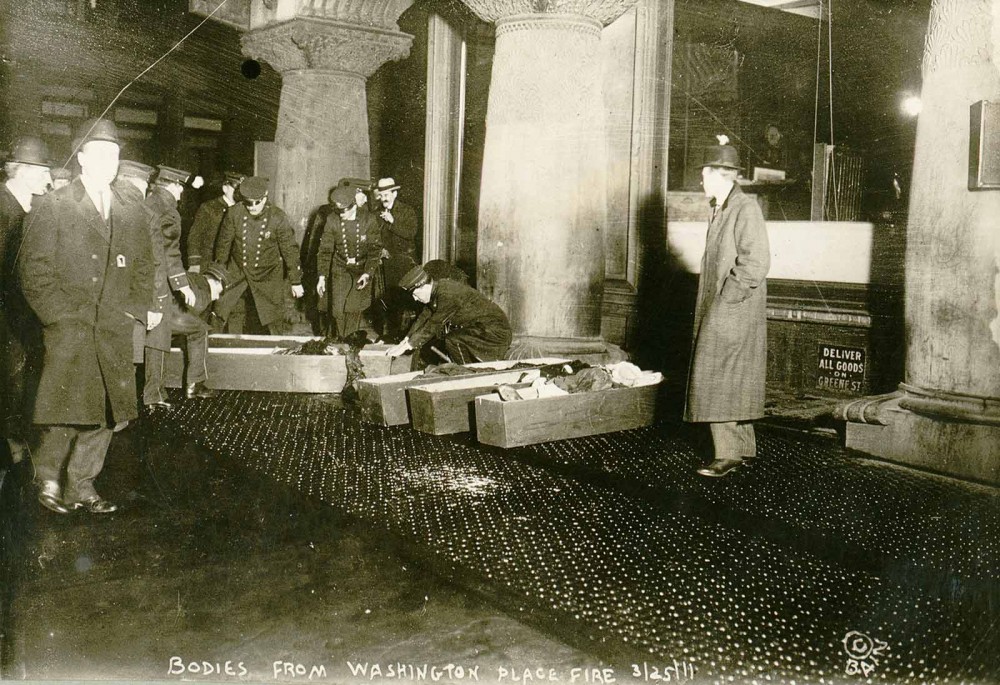

In 1911 the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Manhattan caught fire. The doors of the factory had been chained shut to prevent employees from taking unauthorized breaks (the managers who held the keys saved themselves, but left over two hundred women behind). A rickety fire ladder on the side of the building collapsed immediately. Women lined the rooftop and windows of the ten-story building and jumped, landing in a “mangled, bloody pulp.” Life nets held by firemen tore at the impact of the falling bodies. Among the onlookers, “women were hysterical, scores fainted; men wept as, in paroxysms of frenzy, they hurled themselves against the police lines.” By the time the fire burned itself out, 71 workers were injured and 146 had died. 2

Policemen place the bodies of workers who were burned alive in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist fire into coffins. Photographs like this made real the atrocities that could result from unsafe working conditions. March 25, 1911. Library of Congress .

A year before, the Triangle workers had gone on strike demanding union recognition, higher wages, and better safety conditions. Remembering their workers’ “chief value,” the owners of the factory decided that a viable fire escape and unlocked doors were too expensive and called in the city police to break up the strike. After the 1911 fire, reporter Bill Shepherd reflected, “I looked upon the heap of dead bodies and I remembered these girls were shirtwaist makers. I remembered their great strike last year in which the same girls had demanded more sanitary conditions and more safety precautions in the shops. These dead bodies were the answer.” 3 Former Triangle worker and labor organizer Rose Schneiderman said, “This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in this city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers . . . the life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred! There are so many of us for one job, it matters little if 140-odd are burned to death.” 4 After the fire, Triangle owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris were brought up on manslaughter charges. They were acquitted after less than two hours of deliberation. The outcome continued a trend in the industrializing economy that saw workers’ deaths answered with little punishment of the business owners responsible for such dangerous conditions. But as such tragedies mounted and working and living conditions worsened and inequality grew, it became increasingly difficult to develop justifications for this new modern order.

Events such as the Triangle Shirtwaist fire convinced many Americans of the need for reform, but the energies of activists were needed to spread a new commitment to political activism and government interference in the economy. Politicians, journalists, novelists, religious leaders, and activists all raised their voices to push Americans toward reform.

Reformers turned to books and mass-circulation magazines to publicize the plight of the nation’s poor and the many corruptions endemic to the new industrial order. Journalists who exposed business practices, poverty, and corruption—labeled by Theodore Roosevelt as “muckrakers”—aroused public demands for reform. Magazines such as McClure’s detailed political corruption and economic malfeasance. The muckrakers confirmed Americans’ suspicions about runaway wealth and political corruption. Ray Stannard Baker, a journalist whose reports on U.S. Steel exposed the underbelly of the new corporate capitalism, wrote, “I think I can understand now why these exposure articles took such a hold upon the American people. It was because the country, for years, had been swept by the agitation of soap-box orators, prophets crying in the wilderness, and political campaigns based upon charges of corruption and privilege which everyone believed or suspected had some basis of truth, but which were largely unsubstantiated.” 5

Journalists shaped popular perceptions of Gilded Age injustice. In 1890, New York City journalist Jacob Riis published How the Other Half Lives , a scathing indictment of living and working conditions in the city’s slums. Riis not only vividly described the squalor he saw, he documented it with photography, giving readers an unflinching view of urban poverty. Riis’s book led to housing reform in New York and other cities and helped instill the idea that society bore at least some responsibility for alleviating poverty. 6 In 1906, Upton Sinclair published The Jungle , a novel dramatizing the experiences of a Lithuanian immigrant family who moved to Chicago to work in the stockyards. Although Sinclair intended the novel to reveal the brutal exploitation of labor in the meatpacking industry, and thus to build support for the socialist movement, its major impact was to lay bare the entire process of industrialized food production. The growing invisibility of slaughterhouses and livestock production for urban consumers had enabled unsanitary and unsafe conditions. “The slaughtering machine ran on, visitors or no visitors,” wrote Sinclair, “like some horrible crime committed in a dungeon, all unseen and unheeded, buried out of sight and of memory.” 7 Sinclair’s exposé led to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906.

Jacob Riis, “Home of an Italian Ragpicker.” ca. 1888-1889. Wikimedia.

Of course, it was not only journalists who raised questions about American society. One of the most popular novels of the nineteenth century, Edward Bellamy’s 1888 Looking Backward, was a national sensation. In it, a man falls asleep in Boston in 1887 and awakens in 2000 to find society radically altered. Poverty and disease and competition gave way as new industrial armies cooperated to build a utopia of social harmony and economic prosperity. Bellamy’s vision of a reformed society enthralled readers, inspired hundreds of Bellamy clubs, and pushed many young readers onto the road to reform. 8 It led countless Americans to question the realities of American life in the nineteenth century:

“I am aware that you called yourselves free in the nineteenth century. The meaning of the word could not then, however, have been at all what it is at present, or you certainly would not have applied it to a society of which nearly every member was in a position of galling personal dependence upon others as to the very means of life, the poor upon the rich, or employed upon employer, women upon men, children upon parents.” 9

But Americans were urged to action not only by books and magazines but by preachers and theologians, too. Confronted by both the benefits and the ravages of industrialization, many Americans asked themselves, “What Would Jesus Do?” In 1896, Charles Sheldon, a Congregational minister in Topeka, Kansas, published In His Steps: What Would Jesus Do? The novel told the story of Henry Maxwell, a pastor in a small Midwestern town one day confronted by an unemployed migrant who criticized his congregation’s lack of concern for the poor and downtrodden. Moved by the man’s plight, Maxwell preached a series of sermons in which he asked his congregation: “Would it not be true, think you, that if every Christian in America did as Jesus would do, society itself, the business world, yes, the very political system under which our commercial and government activity is carried on, would be so changed that human suffering would be reduced to a minimum?” 10 Sheldon’s novel became a best seller, not only because of its story but because the book’s plot connected with a new movement transforming American religion: the social gospel.

The social gospel emerged within Protestant Christianity at the end of the nineteenth century. It emphasized the need for Christians to be concerned for the salvation of society, and not simply individual souls. Instead of just caring for family or fellow church members, social gospel advocates encouraged Christians to engage society; challenge social, political, and economic structures; and help those less fortunate than themselves. Responding to the developments of the industrial revolution in America and the increasing concentration of people in urban spaces, with its attendant social and economic problems, some social gospelers went so far as to advocate a form of Christian socialism, but all urged Americans to confront the sins of their society.

One of the most notable advocates of the social gospel was Walter Rauschenbusch. After graduating from Rochester Theological Seminary, in 1886 Rauschenbusch accepted the pastorate of a German Baptist church in the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York City, where he confronted rampant crime and stark poverty, problems not adequately addressed by the political leaders of the city. Rauschenbusch joined with fellow reformers to elect a new mayoral candidate, but he also realized that a new theological framework had to reflect his interest in society and its problems. He revived Jesus’s phrase, “the Kingdom of God,” claiming that it encompassed every aspect of life and made every part of society a purview of the proper Christian. Like Charles Sheldon’s fictional Rev. Maxwell, Rauschenbusch believed that every Christian, whether they were a businessperson, a politician, or a stay-at-home parent, should ask themselves what they could do to enact the kingdom of God on Earth. 11

“The social gospel is the old message of salvation, but enlarged and intensified. The individualistic gospel has taught us to see the sinfulness of every human heart and has inspired us with faith in the willingness and power of God to save every soul that comes to him. But it has not given us an adequate understanding of the sinfulness of the social order and its share in the sins of all individuals within it. It has not evoked faith in the will and power of God to redeem the permanent institutions of human society from their inherited guilt of oppression and extortion. Both our sense of sin and our faith in salvation have fallen short of the realities under its teaching. The social gospel seeks to bring men under repentance for their collective sins and to create a more sensitive and more modern conscience. It calls on us for the faith of the old prophets who believed in the salvation of nations.” 12

Glaring blind spots persisted within the proposals of most social gospel advocates. As men, they often ignored the plight of women, and thus most refused to support women’s suffrage. Many were also silent on the plight of African Americans, Native Americans, and other oppressed minority groups. However, the writings of Rauschenbusch and other social gospel proponents had a profound influence on twentieth-century American life. Most immediately, they fueled progressive reform. But they also inspired future activists, including Martin Luther King Jr., who envisioned a “beloved community” that resembled Rauschenbusch’s “Kingdom of God.”

Suffragists campaigned tirelessly for the vote in the first two decades of the twentieth century, taking to the streets in public displays like this 1915 pre-election parade in New York City. During this one event, 20,000 women defied the gender norms that tried to relegate them to the private sphere and deny them the vote. 1915. Wikimedia .

Reform opened new possibilities for women’s activism in American public life and gave new impetus to the long campaign for women’s suffrage. Much energy for women’s work came from female “clubs,” social organizations devoted to various purposes. Some focused on intellectual development; others emphasized philanthropic activities. Increasingly, these organizations looked outward, to their communities and to the place of women in the larger political sphere.

Women’s clubs flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the 1890s women formed national women’s club federations. Particularly significant in campaigns for suffrage and women’s rights were the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (formed in New York City in 1890) and the National Association of Colored Women (organized in Washington, D.C., in 1896), both of which were dominated by upper-middle-class, educated, northern women. Few of these organizations were biracial, a legacy of the sometimes uneasy midnineteenth-century relationship between socially active African Americans and white women. Rising American prejudice led many white female activists to ban inclusion of their African American sisters.

Black women produced vibrant organizations that could promise racial uplift and civil rights for all Black Americans as well as equal rights for all women. Black abolitionist Mary Jane Richardson Jones organized Black women in Chicago around settlement work, moral uplift, and suffrage. Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, who had also worked for abolition and suffrage, worked with club women in Boston and organized, in 1895, the First National Conference of the Colored Women of America. The following year, Mary Church Terrell and other black activists formed the National Association of Colored Women, later known as the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. These leagues of service-oriented women’s organizations provided powerful networks to organize and amplify Black women’s efforts not only to secure suffrage but to challenge discrimination and uplift Black communities across the United States. 13

Other women worked through churches and moral reform organizations to clean up American life. And still others worked as moral vigilantes. The fearsome Carrie A. Nation, an imposing woman who believed she worked God’s will, won headlines for destroying saloons. In Wichita, Kansas, on December 27, 1900, Nation took a hatchet and broke bottles and bars at the luxurious Carey Hotel. Arrested and charged with causing $3,000 in damages, Nation spent a month in jail before the county dismissed the charges on account of “a delusion to such an extent as to be practically irresponsible.” But Nation’s “hatchetation” drew national attention. Describing herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like,” she continued her assaults, and days later she smashed two more Wichita bars. 14

Few women followed in Nation’s footsteps, and many more worked within more reputable organizations. Nation, for instance, had founded a chapter of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), but the organization’s leaders described her as “unwomanly and unchristian.” The WCTU was founded in 1874 as a modest temperance organization devoted to combating the evils of drunkenness. But then, from 1879 to 1898, Frances Willard invigorated the organization by transforming it into a national political organization, embracing a “do everything” policy that adopted any and all reasonable reforms that would improve social welfare and advance women’s rights. WCTU women worked to alleviate urban poverty, pursued prison reform, championed the eight-hour workday, pushed for child labor laws, advocated “h ome protection,” and fought for numerous other progressive causes. Temperance, and then the full prohibition of alcohol, however, always loomed large.

Many American reformers associated alcohol with nearly every social ill. Alcohol was blamed for domestic abuse, poverty, crime, and disease. The 1912 Anti-Saloon League Yearbook , for instance, presented charts indicating comparable increases in alcohol consumption alongside rising divorce rates. The WCTU called alcohol a “home wrecker.” More insidiously, perhaps, reformers also associated alcohol with cities and immigrants, necessarily maligning America’s immigrants, Catholics, and working classes in their crusade against liquor. Still, reformers believed that the abolition of “strong drink” would bring about social progress, obviate the need for prisons and insane asylums, save women and children from domestic abuse, and usher in a more just, progressive society.

Powerful female activists emerged out of the club movement and temperance campaigns. Perhaps no American reformer matched Jane Addams in fame, energy, and innovation. Born in Cedarville, Illinois, in 1860, Addams lost her mother by age two and lived under the attentive care of her father. At seventeen, she left home to attend Rockford Female Seminary. An idealist, Addams sought the means to make the world a better place. She believed that well-educated women of means, such as herself, lacked practical strategies for engaging everyday reform. After four years at Rockford, Addams embarked on a multiyear “grand tour” of Europe. She found herself drawn to English settlement houses, a kind of prototype for social work in which philanthropists embedded themselves among communities and offered services to disadvantaged populations. After visiting London’s Toynbee Hall in 1887, Addams returned to the United States and in 1889 founded Hull House in Chicago with her longtime confidant and companion Ellen Gates Starr. 15

The Settlement … is an experimental effort to aid in the solution of the social and industrial problems which are engendered by the modern conditions of life in a great city. It insists that these problems are not confined to any one portion of the city. It is an attempt to relieve, at the same time, the overaccumulation at one end of society and the destitution at the other … It must be grounded in a philosophy whose foundation is on the solidarity of the human race, a philosophy which will not waver when the race happens to be represented by a drunken woman or an idiot boy. 16

Hull House workers provided for their neighbors by running a nursery and a kindergarten, administering classes for parents and clubs for children, and organizing social and cultural events for the community. Reformer Florence Kelley, who stayed at Hull House from 1891 to 1899, convinced Addams to move into the realm of social reform. 17 Hull House began exposing conditions in local sweatshops and advocated for the organization of workers. She called the conditions caused by urban poverty and industrialization a “social crime.” Hull House workers surveyed their community and produced statistics on poverty, disease, and living conditions. Addams began pressuring politicians. Together Kelley and Addams petitioned legislators to pass antisweatshop legislation that limited the hours of work for women and children to eight per day. Yet Addams was an upper-class white Protestant woman who, like many reformers, refused to embrace more radical policies. While Addams called labor organizing a “social obligation,” she also warned the labor movement against the “constant temptation towards class warfare.” Addams, like many reformers, favored cooperation between rich and poor and bosses and workers, whether cooperation was a realistic possibility or not. 18

Addams became a kind of celebrity. In 1912, she became the first woman to give a nominating speech at a major party convention when she seconded the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt as the Progressive Party’s candidate for president. Her campaigns for social reform and women’s rights won headlines and her voice became ubiquitous in progressive politics. 19

Addams’s advocacy grew beyond domestic concerns. Beginning with her work in the Anti-Imperialist League during the Spanish-American War, Addams increasingly began to see militarism as a drain on resources better spent on social reform. In 1907 she wrote Newer Ideals of Peace , a book that would become for many a philosophical foundation of pacifism. Addams emerged as a prominent opponent of America’s entry into World War I. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. 20

It would be suffrage, ultimately, that would mark the full emergence of women in American public life. Generations of women—and, occasionally, men—had pushed for women’s suffrage. Suffragists’ hard work resulted in slow but encouraging steps forward during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Notable victories were won in the West, where suffragists mobilized large numbers of women and male politicians were open to experimental forms of governance. By 1911, six western states had passed suffrage amendments to their constitutions.

Women protested silently in front of the White House for over two years before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Here, women represent their colleges as they picket the White House in support of women’s suffrage. 1917. Library of Congress (LC-USZ62-31799).

Women’s suffrage was typically entwined with a wide range of reform efforts. Many suffragists argued that women’s votes were necessary to clean up politics and combat social evils. By the 1890s, for example, the WCTU, then the largest women’s organization in America, endorsed suffrage. An alliance of working-class and middle- and upper-class women organized the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) in 1903 and campaigned for the vote alongside the National American Woman Suffrage Association, a leading suffrage organization composed largely of middle- and upper-class women. WTUL members viewed the vote as a way to further their economic interests and to foster a new sense of respect for working-class women. “What the woman who labors wants is the right to live, not simply exist,” said Rose Schneiderman, a WTUL leader, during a 1912 speech. “The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too.” 21

Many suffragists adopted a much crueler message. Some, even outside the South, argued that white women’s votes were necessary to maintain white supremacy. Many white American women argued that enfranchising white upper- and middle-class women would counteract Black voters. These arguments even stretched into international politics. But whether the message advocated gender equality, class politics, or white supremacy, the suffrage campaign was winning.

The final push for women’s suffrage came on the eve of World War I. Determined to win the vote, the National American Woman Suffrage Association developed a dual strategy that focused on the passage of state voting rights laws and on the ratification of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Meanwhile, a new, more militant, suffrage organization emerged on the scene. Led by Alice Paul, the National Woman’s Party took to the streets to demand voting rights, organizing marches and protests that mobilized thousands of women. Beginning in January 1917, National Woman’s Party members also began to picket the White House, an action that led to the arrest and imprisonment of over 150 women. 22

In January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson declared his support for the women’s suffrage amendment, and two years later women’s suffrage became a reality. After the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, women from all walks of life mobilized to vote. They were driven by the promise of change but also in some cases by their anxieties about the future. Much had changed since their campaign began; the United States was now more industrial than not, increasingly more urban than rural. The activism and activities of these new urban denizens also gave rise to a new American culture.

In one of the defining books of the Progressive Era, The Promise of American Life , Herbert Croly argued that because “the corrupt politician has usurped too much of the power which should be exercised by the people,” the “millionaire and the trust have appropriated too many of the economic opportunities formerly enjoyed by the people.” Croly and other reformers believed that wealth inequality eroded democracy and reformers had to win back for the people the power usurped by the moneyed trusts. But what exactly were these “trusts,” and why did it suddenly seem so important to reform them? 23

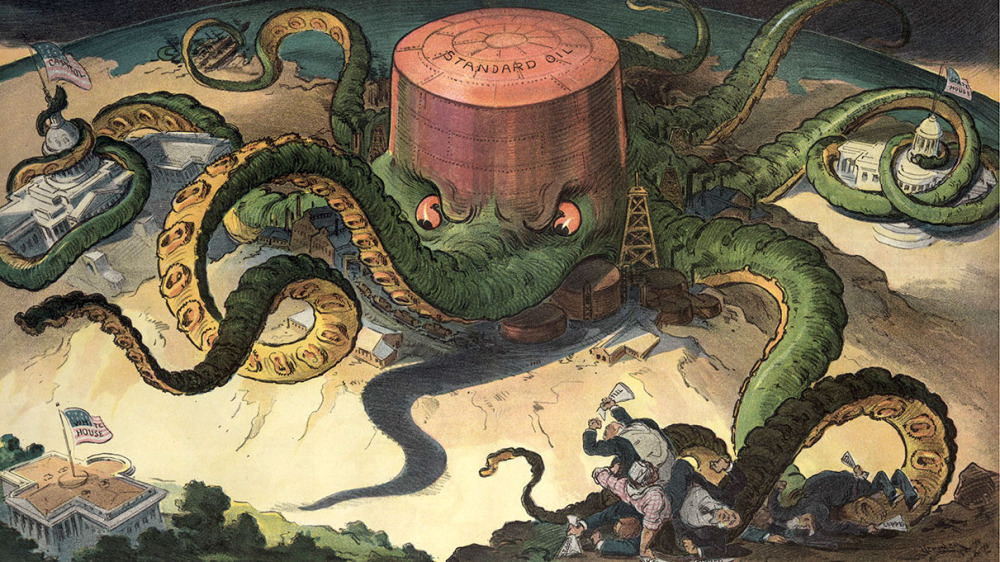

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a trust was a monopoly or cartel associated with the large corporations of the Gilded and Progressive Eras who entered into agreements—legal or otherwise—or consolidations to exercise exclusive control over a specific product or industry under the control of a single entity. Certain types of monopolies, specifically for intellectual property like copyrights, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets, are protected under the Constitution “to promote the progress of science and useful arts,” but for powerful entities to control entire national markets was something wholly new, and, for many Americans, wholly unsettling.