- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Joe Biden Leads

- TIME100 Most Influential Companies 2024

- Javier Milei’s Radical Plan to Transform Argentina

- How Private Donors Shape Birth-Control Choices

- What Sealed Trump’s Fate : Column

- Are Walking Pads Worth It?

- 15 LGBTQ+ Books to Read for Pride

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

A new, streamlined version of Intervention Central is coming in December 2023. The new site will eliminate user login accounts. If you have a login account, be sure to download and save any documents of importance from that account, as they will be erased when the website is revised.

- Academic Interventions

- Behavior Interventions

- CBM/Downloads

How To: Choose the Right Amount of Daily Homework

|

| |||

|

| | | |

| 1 | 10 Minutes | -- | 10-45 Minutes |

| 2 | 20 Minutes | -- | 10-45 Minutes |

| 3 | 30 Minutes | -- | 10-45 Minutes |

| 4 | 40 Minutes | -- | 45-90 Minutes |

| 5 | 50 Minutes | -- | 45-90 Minutes |

| 6 | 1 Hour | -- | 45-90 Minutes |

| 7 | 1 Hour 10 Minutes | 1-2 Hours | 1-2 Hours |

| 8 | 1 Hour 20 Minutes | 1-2 Hours | 1-2 Hours |

| 9 | 1 Hour 30 Minutes | 1.5-2.5 Hours | 1-2 Hours |

| 10 | 1 Hour 40 Minutes | 1.5-2.5 Hours | 1.5-2.5 Hours |

| 11 | 1 Hour 50 Minutes | 1.5-2.5 Hours | 1.5-2.5 Hours |

| 12 | 2 Hours | 1.5-2.5 Hours | 1.5-2.5 Hours |

Despite the differences in the recommendations from these sources, the table shows broad agreement about how much homework to assign at each grade. At grades 1-3, homework should be limited to an hour or less per day, while in grades 4-6, homework should not exceed 90 minutes. The upper limit in grades 7-8 is 2 hours and the limit in high school should be 2.5 hours.

Teachers can use the homework time recommendations included here as a point of comparison: in particular, schools should note that assigning homework that exceeds the upper limit of these time estimates is not likely to result in additional learning gains--and may even be counter-productive (Cooper, Robinson, & Patall, 2006).

It should also be remembered that the amount of homework assigned each day is not in itself a sign of high academic standards. Homework becomes a powerful tool to promote learning only when students grasp the purpose of each homework assignment, clearly understand homework directions, perceive that homework tasks are instructionally relevant, and receive timely performance feedback (e.g., teacher comments; grades) on submitted homework (Jenson, Sheridan, Olympia, & Andrews, 1994).

Attachments

- Download This Blog Entry in PDF Format: How To: Choose the Right Amount of Daily Homework

- Barkley, R. A. (2008). 80+ classroom accommodations for children or teens with ADHD. The ADHD Report, 16 (4), 7-10.

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987-2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1-62.

- Jenson, W. R., Sheridan, S. M., Olympia, D., & Andrews, D. (1994). Homework and students with learning disabilities and behavior disorders: A practical, parent-based approach. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27 , 538-548.

How Much Homework Is Too Much?

Are schools assigning too much homework.

Posted October 19, 2011

Timothy, a fifth grader, spends up to thirteen hours a day hunched over a desk at school or at home, studying and doing homework. Should his parents feel proud? Now imagine, for comparison's sake, Timothy spending thirteen hours a day hunched over a sewing machine instead of a desk.

Parents have the right to complain when schools assign too much homework but they often don't know how to do so effectively.

Drowning in Homework ( an excerpt from Chapter 8 of The Squeaky Wheel )

I first met Timothy, a quiet, overweight eleven-year-old boy, when his mother brought him to therapy to discuss his slipping grades. A few minutes with Timothy were enough to confirm that his mood, self-esteem , and general happiness were slipping right along with them. Timothy attended one of the top private schools in Manhattan, an environment in which declining grades were no idle matter.

I asked about Timothy's typical day. He awoke every morning at six thirty so he could get to school by eight and arrived home around four thirty each afternoon. He then had a quick snack, followed by either a piano lesson or his math tutor, depending on the day. He had dinner at seven p.m., after which he sat down to do homework for two to three hours a night. Quickly doing the math in my head, I calculated that Timothy spent an average of thirteen hours a day hunched over a writing desk. His situation is not atypical. Spending that many hours studying is the only way Timothy can keep up and stay afloat academically.

But what if, for comparison's sake, we imagined Timothy spending thirteen hours a day hunched over a sewing machine instead of a desk. We would immediately be aghast at the inhumanity because children are horribly mistreated in such "sweatshops." Timothy is far from being mistreated, but the mountain of homework he faces daily results in a similar consequence- he too is being robbed of his childhood.

Timothy's academics leave him virtually no time to do anything he truly enjoys, such as playing video games, movies, or board games with his friends. During the week he never plays outside and never has indoor play dates or opportunities to socialize with friends. On weekends, Timothy's days are often devoted to studying for tests, working on special school projects, or arguing with his mother about studying for tests and working on special school projects.

By the fourth and fifth grade and certainly in middle school, many of our children have hours of homework, test preparation, project writing, or research to do every night, all in addition to the eight hours or more they have to spend in school. Yet study after study has shown that homework has little to do with achievement in elementary school and is only marginally related to achievement in middle school .

Play, however, is a crucial component of healthy child development . It affects children's creativity , their social skills, and even their brain development. The absence of play, physical exercise, and free-form social interaction takes a serious toll on many children. It can also have significant health implications as is evidenced by our current epidemic of childhood obesity, sleep deprivation, low self- esteem, and depression .

A far stronger predictor than homework of academic achievement for kids aged three to twelve is having regular family meals. Family meals allow parents to check in, to demonstrate caring and involvement, to provide supervision, and to offer support. The more family meals can be worked into the schedule, the better, especially for preteens. The frequency of family meals has also been shown to help with disordered eating behaviors in adolescents.

Experts in the field recommend children have no more than ten minutes of homework per day per grade level. As a fifth- grader, Timothy should have no more than fifty minutes a day of homework (instead of three times that amount). Having an extra two hours an evening to play, relax, or see a friend would constitute a huge bump in any child's quality of life.

So what can we do if our child is getting too much homework?

1. Complain to the teachers and the school. Most parents are unaware that excessive homework contributes so little to their child's academic achievement.

2. Educate your child's teacher and principal about the homework research-they are often equally unaware of the facts and teachers of younger children (K-4) often make changes as a result.

3. Create allies within the system by speaking with other parents and banding together to address the issue with the school.

You might also like: Is Excessive Homework in Private Schools a Customer Service Issue?

View my short and quite personal TED talk about Psychological Health here:

Check out my new book, Emotional First Aid: Practical Strategies for Treating Failure, Rejection, Guilt and Other Evreyday Psychological Injuries (Hudson Street Press).

Click here to join my mailing list

Copyright 2011 Guy Winch

Follow me on Twitter @GuyWinch

Guy Winch, Ph.D. , is a licensed psychologist and author of Emotional First Aid: Healing Rejection, Guilt, Failure, and Other Everyday Hurts.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

You are here

- News Center

In the Media

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

Homework in High School: How Much Is Too Much?

Please try again

It’s not hard to find a high school student who is stressed about homework. Many are stressed to the max–juggling extracurricular activities, jobs, and family responsibilities. It can be hard for many students, particularly low-income students, to find the time to dedicate to homework. So students in the PBS NewsHour Student Reporting Labs program at YouthBeat in Oakland, California are asking what’s a fair amount of homework for high school students?

TEACHERS: Guide your students to practice civil discourse about current topics and get practice writing CER (claim, evidence, reasoning) responses. Explore lesson supports.

Is homework beneficial to students?

The homework debate has been going on for years. There’s a big body of research that shows that homework can have a positive impact on academic performance. It can also help students prepare for the academic rigors of college.

Does homework hurt students?

Some research suggests that homework is only beneficial up to a certain point. Too much homework can lead to compromised health and greater stress in students. Many students, particularly low-income students, can struggle to find the time to do homework, especially if they are working jobs after school or taking care of family members. Some students might not have access to technology, like computers or the internet, that are needed to complete assignments at home– which can make completing assignments even more challenging. Many argue that this contributes to inequity in education– particularly if completing homework is linked to better academic performance.

How much homework should students get?

Based on research, the National Education Association recommends the 10-minute rule stating students should receive 10 minutes of homework per grade per night. But opponents to homework point out that for seniors that’s still 2 hours of homework which can be a lot for students with conflicting obligations. And in reality, high school students say it can be tough for teachers to coordinate their homework assignments since students are taking a variety of different classes. Some people advocate for eliminating homework altogether.

Edweek: How Much Homework Is Enough? Depends Who You Ask

Business Insider: Here’s How Homework Differs Around the World

Review of Educational Research: Does Homework Improve Academic Achievement? A Synthesis of Research, 1987-2003

Phys.org: Study suggests more than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive

The Journal of Experimental Education: Nonacademic Effects of Homework in Privileged, High-Performing High Schools

National Education Association: Research Spotlight on Homework NEA Reviews of the Research on Best Practices in Education

The Atlantic: Who Does Homework Work For?

Center for Public Education: What research says about the value of homework: Research review

Time: Opinion: Why I think All Schools Should Abolish Homework

The Atlantic: A Teacher’s Defense of Homework

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.

The Cult of Homework

America’s devotion to the practice stems in part from the fact that it’s what today’s parents and teachers grew up with themselves.

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed , which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s . Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study , for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Read: My daughter’s homework is killing me

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s , and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing , considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork , while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”

“Exploratory” is one word Mike Simpson used when describing the types of homework he’d like his students to undertake. Simpson is the head of the Stone Independent School, a tiny private high school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that opened in 2017. “We were lucky to start a school a year and a half ago,” Simpson says, “so it’s been easy to say we aren’t going to assign worksheets, we aren’t going assign regurgitative problem sets.” For instance, a half-dozen students recently built a 25-foot trebuchet on campus.

Simpson says he thinks it’s a shame that the things students have to do at home are often the least fulfilling parts of schooling: “When our students can’t make the connection between the work they’re doing at 11 o’clock at night on a Tuesday to the way they want their lives to be, I think we begin to lose the plot.”

When I talked with other teachers who did homework makeovers in their classrooms, I heard few regrets. Brandy Young, a second-grade teacher in Joshua, Texas, stopped assigning take-home packets of worksheets three years ago, and instead started asking her students to do 20 minutes of pleasure reading a night. She says she’s pleased with the results, but she’s noticed something funny. “Some kids,” she says, “really do like homework.” She’s started putting out a bucket of it for students to draw from voluntarily—whether because they want an additional challenge or something to pass the time at home.

Chris Bronke, a high-school English teacher in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove, told me something similar. This school year, he eliminated homework for his class of freshmen, and now mostly lets students study on their own or in small groups during class time. It’s usually up to them what they work on each day, and Bronke has been impressed by how they’ve managed their time.

In fact, some of them willingly spend time on assignments at home, whether because they’re particularly engaged, because they prefer to do some deeper thinking outside school, or because they needed to spend time in class that day preparing for, say, a biology test the following period. “They’re making meaningful decisions about their time that I don’t think education really ever gives students the experience, nor the practice, of doing,” Bronke said.

The typical prescription offered by those overwhelmed with homework is to assign less of it—to subtract. But perhaps a more useful approach, for many classrooms, would be to create homework only when teachers and students believe it’s actually needed to further the learning that takes place in class—to start with nothing, and add as necessary.

What’s the Right Amount of Homework? Many Students Get Too Little, Brief Argues

- Share article

Arguments against homework are well-documented, with some parents, teachers, and researchers saying these assignments put unnecessary stress on students and may not actually be helping them learn.

But a new article for the journal Education Next argues that many American students don’t have too much homework—they have too little.

Anxiety about overscheduled students with upwards of three or four hours of homework a night has overshadowed another problem, writes Janine Bempechat, a clinical professor of human development at the Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development: Low-income students aren’t getting enough homework, and they may be suffering academically as a result.

“Eliminating homework is probably not as big a problem for high-income kids, because they have parents who will expose them to what they may not be getting after school,” Bempechat said in an interview with Education Week . “It’s lower-income students who are hurt the most when people argue that homework should be entirely eliminated.”

A widely endorsed metric for how much homework to assign is the 10-minute rule. It dictates that children should receive 10 minutes of homework per grade level—so a 1st grader would be given 10 minutes a day, while a senior in high school would have 120 minutes.

It’s hard to say exactly how closely American teachers hew to those guidelines. A 2013 study conducted by the University of Phoenix found that high school students are assigned about 3.5 hours of homework a night . But results from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment found that 15-year-olds in the U.S. say they have much less than that—about six hours of homework a week .

But the averages obscure the range in assigned work between low-income and high-income students, Bempechat argues. According to the PISA results, disadvantaged students in the U.S. spend three hours less a week on homework than advantaged students (five hours versus eight hours).

Some students may be receiving even less than that. In interviews with low-income students at two low-performing high schools in northern California, Bempechat and her colleagues found that most students reported receiving what she called “minimal homework": “perhaps one or two worksheets or textbook pages, the occasional project, and 30 minutes of reading per night.”

This is a problem, she writes, because high-quality homework—the kind that allows students to problem solve and comes with clear instructions and strategies for working through difficult problems—helps students develop key academic skills. Some research supports this claim: In a 2004 study , researchers at Columbia University and Mississippi State University found that homework can prepare students with the perseverance they would need to hold jobs in the future.

The research on whether homework leads to increased academic achievement is mixed: a 2006 meta-analysis found that at-home assignments led to increased scores on some tests in some grades , but other studies show no relationship for elementary age students.

But goal-setting, self-regulation, and “resilience in the face of challenge” can all be learned through homework, said Bempechat. These skills only become more important as students progress into higher grades with greater expectations for learner autonomy, she said.

Some critics of homework raise concerns that assigning outside work puts low-income students at a disadvantage, because their parents may not be able to offer as much guidance as higher-income parents.

Bempechat writes that it’s more important that parents support homework completion rather than give hands-on help with assignments . She cites a 2014 study by researchers at the City University of New York that found that low-income parents providing structure around homework was a significant predictor of middle school students’ math grades .

But other barriers to home-based assignments persist for low-income students, including the “homework gap:" the inequality between students who have internet at home and those who don’t, and the difficulty that students without access face in completing assignments. About 40 percent of students didn’t have internet access at home as of 2015. But most teachers—70 percent—assign homework that requires connectivity, according to a 2016 survey from the Consortium for School Networking, a national association for school technology leaders.

Teachers should be mindful of the resources students have at home, said Bempechat, and not assign work that requires tools they don’t have—whether that be internet access or even crayons and markers.

Image: Getty

A version of this news article first appeared in the Teaching Now blog.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

- May 28 Engi-near the finish line

- May 17 Love is in the air

- May 11 Art Car Club showcases its rolling artwork on wheels at the Orange Show parade

- May 3 Cultures collide at the Bellaire International Student Association Fest

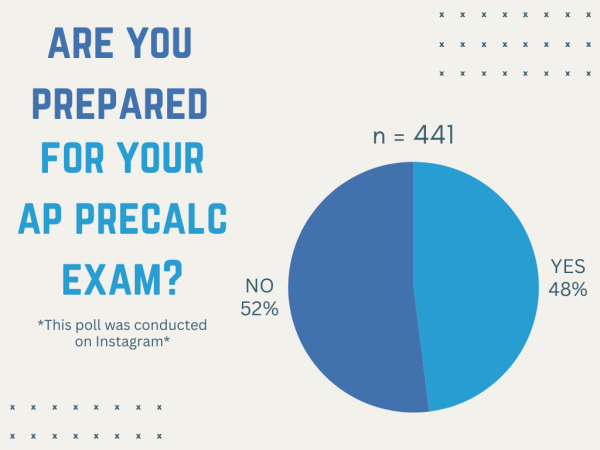

- May 2 Uncalculated uncertainties

Three Penny Press

Students spend three times longer on homework than average, survey reveals

Sonya Kulkarni and Pallavi Gorantla | Jan 9, 2022

Graphic by Sonya Kulkarni

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association have suggested that a healthy number of hours that students should be spending can be determined by the “10-minute rule.” This means that each grade level should have a maximum homework time incrementing by 10 minutes depending on their grade level (for instance, ninth-graders would have 90 minutes of homework, 10th-graders should have 100 minutes, and so on).

As ‘finals week’ rapidly approaches, students not only devote effort to attaining their desired exam scores but make a last attempt to keep or change the grade they have for semester one by making up homework assignments.

High schoolers reported doing an average of 2.7 hours of homework per weeknight, according to a study by the Washington Post from 2018 to 2020 of over 50,000 individuals. A survey of approximately 200 Bellaire High School students revealed that some students spend over three times this number.

The demographics of this survey included 34 freshmen, 43 sophomores, 54 juniors and 54 seniors on average.

When asked how many hours students spent on homework in a day on average, answers ranged from zero to more than nine with an average of about four hours. In contrast, polled students said that about one hour of homework would constitute a healthy number of hours.

Junior Claire Zhang said she feels academically pressured in her AP schedule, but not necessarily by the classes.

“The class environment in AP classes can feel pressuring because everyone is always working hard and it makes it difficult to keep up sometimes.” Zhang said.

A total of 93 students reported that the minimum grade they would be satisfied with receiving in a class would be an A. This was followed by 81 students, who responded that a B would be the minimum acceptable grade. 19 students responded with a C and four responded with a D.

“I am happy with the classes I take, but sometimes it can be very stressful to try to keep up,” freshman Allyson Nguyen said. “I feel academically pressured to keep an A in my classes.”

Up to 152 students said that grades are extremely important to them, while 32 said they generally are more apathetic about their academic performance.

Last year, nine valedictorians graduated from Bellaire. They each achieved a grade point average of 5.0. HISD has never seen this amount of valedictorians in one school, and as of now there are 14 valedictorians.

“I feel that it does degrade the title of valedictorian because as long as a student knows how to plan their schedule accordingly and make good grades in the classes, then anyone can be valedictorian,” Zhang said.

Bellaire offers classes like physical education and health in the summer. These summer classes allow students to skip the 4.0 class and not put it on their transcript. Some electives also have a 5.0 grade point average like debate.

Close to 200 students were polled about Bellaire having multiple valedictorians. They primarily answered that they were in favor of Bellaire having multiple valedictorians, which has recently attracted significant acclaim .

Senior Katherine Chen is one of the 14 valedictorians graduating this year and said that she views the class of 2022 as having an extraordinary amount of extremely hardworking individuals.

“I think it was expected since freshman year since most of us knew about the others and were just focused on doing our personal best,” Chen said.

Chen said that each valedictorian achieved the honor on their own and deserves it.

“I’m honestly very happy for the other valedictorians and happy that Bellaire is such a good school,” Chen said. “I don’t feel any less special with 13 other valedictorians.”

Nguyen said that having multiple valedictorians shows just how competitive the school is.

“It’s impressive, yet scary to think about competing against my classmates,” Nguyen said.

Offering 30 AP classes and boasting a significant number of merit-based scholars Bellaire can be considered a competitive school.

“I feel academically challenged but not pressured,” Chen said. “Every class I take helps push me beyond my comfort zone but is not too much to handle.”

Students have the opportunity to have off-periods if they’ve met all their credits and are able to maintain a high level of academic performance. But for freshmen like Nguyen, off periods are considered a privilege. Nguyen said she usually has an hour to five hours worth of work everyday.

“Depending on the day, there can be a lot of work, especially with extra curriculars,” Nguyen said. “Although, I am a freshman, so I feel like it’s not as bad in comparison to higher grades.”

According to the survey of Bellaire students, when asked to evaluate their agreement with the statement “students who get better grades tend to be smarter overall than students who get worse grades,” responders largely disagreed.

Zhang said that for students on the cusp of applying to college, it can sometimes be hard to ignore the mental pressure to attain good grades.

“As a junior, it’s really easy to get extremely anxious about your GPA,” Zhang said. “It’s also a very common but toxic practice to determine your self-worth through your grades but I think that we just need to remember that our mental health should also come first. Sometimes, it’s just not the right day for everyone and one test doesn’t determine our smartness.”

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Raymond Han

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Mia Lopez

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Cordavian Adams

Senior strategies

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Sara Shen

Engi-near the finish line

Love is in the air

Art Car Club showcases its rolling artwork on wheels at the Orange Show parade

Cultures collide at the Bellaire International Student Association Fest

Uncalculated uncertainties

Humans of Bellaire

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Shaun Israni

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Sean Olivar

‘Nerds playing air guitar’

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Charlotte Clague

Combining communities

The student news site of Bellaire High School

- Letter to the Editor

- Submit a Story Idea

- Advertising/Sponsorships

Comments (7)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Anonymous • Nov 21, 2023 at 10:32 am

It’s not really helping me understand how much.

josh • May 9, 2023 at 9:58 am

Kassie • May 6, 2022 at 12:29 pm

Im using this for an English report. This is great because on of my sources needed to be from another student. Homework drives me insane. Im glad this is very updated too!!

Kaylee Swaim • Jan 25, 2023 at 9:21 pm

I am also using this for an English report. I have to do an argumentative essay about banning homework in schools and this helps sooo much!

Izzy McAvaney • Mar 15, 2023 at 6:43 pm

I am ALSO using this for an English report on cutting down school days, homework drives me insane!!

E. Elliott • Apr 25, 2022 at 6:42 pm

I’m from Louisiana and am actually using this for an English Essay thanks for the information it was very informative.

Nabila Wilson • Jan 10, 2022 at 6:56 pm

Interesting with the polls! I didn’t realize about 14 valedictorians, that’s crazy.

What’s the right amount of homework for my students?

Sara Austin May 25, 2022

Whether in their K-12 experience or in college, most teachers can remember a time when they felt overwhelmed by the amount of homework they were asked to do. Homework has been a staple of the school experience since the early days of formal education. Over the years, however, research has shown that more is not always better when it comes to homework. Some students, such as primary students, see no benefit from homework, while high school students see only limited benefits.

The truth is that homework is a controversial subject, even among school teachers. Every student is different — some are self-motivated and independent, while others need constant supervision in order to succeed. These differences can lead to disagreement regarding the optimal amount of homework that should be assigned. As a result, the question of how much homework to assign can be difficult to answer.

Too much homework can negatively impact students in ways you might not expect. Understanding these impacts will make you a better, more effective, and more empathetic teacher to your students. Let’s begin by looking at some of the ways that homework can negatively impact students. Then, we’ll look at recommendations for how much homework is appropriate at different grade levels.

School work can worsen the impacts of lack of access for vulnerable students

One of the lessons learned during the pandemic is that access to resources among students varied widely. The underlying inequities facing students meant that some students could continue their education remotely while others fell behind.

According to a study from Pew Research , one in five teens struggle to complete their homework because they don’t have access to the internet or a home computer. Even with the best intentions, homework poses an unequal burden on students, depending on their socioeconomic status. Students of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to have the resources that help them do homework, such as a computer or a quiet place to work. They’re more likely than their wealthier peers to live in noisy neighborhoods and work after a school day.

While some students may have access to computers, they may not have free access to the internet at home. These factors make it harder for disadvantaged students to complete assignments at home effectively — and this means it’s harder for them to get the same kind of education that their advantaged peers are getting.

The pandemic revealed at least two areas where inequity impacted student success.

The resource accessibility gap

Some students simply don’t have access to resources that make it possible to do their school work. Kids from middle- to high-income families often have computers, access to the internet, and a quiet place to study with no distractions. In contrast, low-income kids may live in a noisy home shared by many people or are sent to an unsafe neighborhood library where they can be at risk of being approached by strangers. Some students may live in places where there is no internet at all.

The pandemic also revealed inequities in the amount of assistance students would receive from their parents or guardians. Many low-income students were home alone all day as their parents worked in essential jobs such as the service industry. Without anyone at home to help with their schoolwork or to help kids stay on track, these kids suffered massive learning losses that will take years to recover from.

The learning accessibility gap

Some students learn more effectively from an interactive teacher than from a textbook or online video, and they need help understanding the material gained through homework assignments. Having additional time with a teacher (in class, after school, or over the phone) can be helpful for these students. Wealthy parents can pay for tutors and extra classes — low-income parents cannot afford such luxuries.

These disparities, which are not always obvious to teachers, can have long-lasting effects on the academic success of low-income and minority students.

Homework can lead to greater stress and conflict in the home

Homework can have negative impacts on students’ home lives since it can be a catalyst for family conflicts. For example, a child with hours of homework may come home from school and have to spend hours completing it, leaving little time to eat dinner before going to bed. With too much homework, family time is replaced by homework time, especially when parents have to help their children with their work. In this scenario, parents spend their time in the afternoons and evenings policing schoolwork rather than nurturing family bonds in important ways.

The education level of parents also plays a role. Parents with a college degree tend to have more confidence in helping their children with homework, but many parents do not have a college degree. In these households, homework is a significant stressor. These parents do not feel comfortable helping with school work and expect their children to have learned everything they need to know in order to complete their homework. Without parental support or assistance, these children can fall even further behind.

School work can also take time away from their hobbies and other interests, leading to poor mental health. In addition, the pressure of homework takes away children’s freedom, as they cannot spend time exploring other interests or building relationships with family and friends.

Homework can even have negative impacts on students’ academic performance

Many studies have shown that homework offers no benefit in elementary school and, due to the impacts of academic stress and inequity, can even be detrimental. Feelings of stress and fear can lead to resentment and a generally negative outlook on the entire educational experience, for both students and their parents. These feelings then color the child’s perception of school, leading some to hate it.

It’s also worth asking if homework is really necessary. Research has found little evidence of a correlation between how much time kids spend on math and reading homework and how well they perform in these subjects once they’re back in class.

Assigning the right amount of homework

So how can we be sure to assign the right amount of homework? While there is some debate on this, the answer is actually quite simple: it depends. Fortunately, research has been done in this area that provides some clarity. The right amount of homework depends on the age and ability of students and the subject matter.

Homework by grade level

The National Education Association offers a simple guideline to help you determine how much homework is appropriate at each grade level. This framework is also endorsed by the National Parent Teacher Association National Parent Teachers Association .

According to this rule, time spent on homework each night should not exceed:

- 30 minutes in 3 rd grade

- 40 minutes in 4 th grade

- 50 minutes in 5 th grade

- 60 minutes in 6 th grade

- 70 minutes in 7 th grade

- 80 minutes in 8 th grade

Worried that you might be assigning too much? Talk to your students about how long they spend on homework and adjust accordingly. Remember that the point of homework is to support learning and not to cause undue stress. Students need to be able to complete their assignments in order to learn, but they also shouldn’t be overwhelmed with too many tasks.

Homework by subject matter

The homework you assign should also differ based on the subject. For example, while your fifth grader may benefit from nightly math worksheets, your third grader’s homework should include more reading exercises than daily arithmetic assignments.

Remember that the amount of help that students get from parents at home can vary a great deal. For this reason, the homework you assign should be work students can complete on their own, without the need for parental help.

The Homework Debate

Many schools are doing away with homework all together. This is because, after decades of research, there is still no evidence of any academic benefit of take-home work in grades K-8 and very little to support it in high school either.

The main thing to remember is this: simply increasing the amount of homework that a child has will not make them more successful. On the contrary, assigning too much homework — or the wrong kind — could actually harm their development.

Keep in mind what you are trying to accomplish with homework. Is the homework intended to give the student practice in completing a task? Is it to improve test scores? Research has actually shown that students who do more than 90 minutes of homework tend to have lower test scores than those who do less . As you consider homework for your students, remember that many of the factors influencing homework performance are not visible to you, and that you should always prioritize quality over quantity.

Photo Credit: Google Education

Classroom Management

The Griffon

Want to stay in the loop about Classcraft? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter for updates on new features and fixes, pedagogical content, and much more!

The truth about homework in America

by: Carol Lloyd | Updated: May 6, 2024

Print article

Not excited about homework? We can hardly blame you. But how families handle homework in America can have a huge impact on their child’s short-term and long-term academic success. Here’s a glimpse at how American families approach homework, and some tips that may help you decide how to handle homework in your home.

Model how much you value your child’s education

Think of your child’s nightly homework as a time to model how much you value your child’s learning and education. Get in the habit of asking your child what homework they have each evening, looking over their homework when they’re done each night, praising their hard work, and marveling at all that they are learning. Your admiration and love is the best magic learning potion available.

Set up a homework routine American parents who want their children to graduate from high school and go to college take learning at home seriously. They turn off the TV and radio at homework time. They take away access to video games and smartphones. They make sure the child gets some exercise and has a healthy snack before starting homework because both are shown to help kids focus. When it’s time for homework, they (try to) ensure their child has a quiet place where they can focus and have access to the grade-appropriate homework basics, like paper, pencils, erasers, crayons, and tape for kids in younger grades and calculators and writing materials for kids in older grades.

Helping with homework when you don’t read/speak English

So how can you help with homework if you can’t read your child’s homework because it’s in English — or because the math is being presented in a way you’ve never seen? If you can’t understand your child’s homework, you can still do a lot to help them. Your physical presence (and your authority to turn off the TV) can help them take homework time seriously. Your encouragement that they take their time and not rush through the work also will help. Finally, your ability to ask questions can do two important things: you can show your interest in their work (and thus reinforce the importance you place on learning and education) and you can help your child slow down and figure things out when they’re lost or frustrated. A lot of learning happens when children have a chance to talk through problems and ideas. Sometimes, just describing the assignment or problem to you can help the solution click for your child.

What’s the right amount of homework?

It’s often in first grade that kids start receiving regular homework and feel stressed and lost if they don’t complete it. If your child is having trouble adjusting to their new routines, know that it’s not just your child. Families all across America are having the same issues in terms of figuring out how to create quiet, focussed time for a young child to read, write, and do math inside a bustling home. In first grade, your child will likely be asked to do somewhere between 10 and 30 minutes of homework a night, sometimes in addition to 20 minutes of bedtime reading. ( The National PTA’s research-based recommendation is 10 to 20 minutes of homework a night in first grade and an additional 10 minutes per grade level thereafter.) If your child is getting a lot more than that, talk to your child’s teacher about how long your child should be spending on homework and what you can do to help.

Comparing U.S. homework time to other countries

If you’ve come from another country and recall your childhood homework taking less time, you may think it’s because you’re foreign. The truth is, most parents who grew up in the U.S. are feeling the same way. In the past few decades homework for younger grades has intensified in many schools. “The amount of homework that younger kids — ages 6 to 9 — have to do has gone up astronomically since the late ’80s,” says Alfie Kohn, author of the 2006 book The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing. So if you feel surprised about the quantity of homework your child is bringing home, you’re not alone.

According to an international study of homework, 15-year-olds in Shanghai do 13.8 hours of homework per week compared to 6.1 hours in the U.S. and 5.3 hours in Mexico and 3.4 hours in Costa Rica. But here’s the thing: academic expectations in the U.S. vary widely from school to school. Some American elementary schools have banned homework. Others pile on hours a night — even in the younger grades. By high school, though, most American students who are seriously preparing for four-year college are doing multiple hours of homework most nights.

Not into homework? Try this.

Homework detractors point to research that shows homework has no demonstrated benefits for students in the early elementary grades. “The research clearly shows that there is no correlation between academic achievement and homework, especially in the lower grades,” says Denise Pope, senior lecturer at the Stanford University Graduate School of Education and the author of the 2015 book, Overloaded and Underprepared: Strategies for Stronger Schools and Healthy Successful Kids .

On the other hand, nightly reading is hugely important.

“One thing we know does have a correlation with academic achievement is free reading time,” says Pope. “We know that that is something we want schools to encourage.” Since the scientific evidence shows the most impact comes from reading for pleasure, don’t skip bedtime reading. If your child is not being given any homework, make sure to spend some of that extra time reading books in either English or Spanish.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How our schools are (and aren't) addressing race

What should I write my college essay about?

What the #%@!& should I write about in my college essay?

Should your teen take the PSAT — and if so, when?

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

Homework Guidelines for Elementary and Middle School Teachers

- Homework Tips

- Learning Styles & Skills

- Study Methods

- Time Management

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- M.Ed., Educational Administration, Northeastern State University

- B.Ed., Elementary Education, Oklahoma State University

Homework; the term elicits a myriad of responses. Students are naturally opposed to the idea of homework. No student ever says, “I wish my teacher would assign me more homework.” Most students begrudge homework and find any opportunity or possible excuse to avoid doing it.

Educators themselves are split on the issue. Many teachers assign daily homework seeing it as a way to further develop and reinforce core academic skills, while also teaching students responsibility. Other educators refrain from assigning daily homework. They view it as unnecessary overkill that often leads to frustration and causes students to resent school and learning altogether.

Parents are also divided on whether or not they welcome homework. Those who welcome it see it as an opportunity for their children to reinforce critical learning skills. Those who loathe it see it as an infringement of their child’s time. They say it takes away from extra-curricular activities, play time, family time, and also adds unnecessary stress.

Research on the topic is also inconclusive. You can find research that strongly supports the benefits of assigning regular homework, some that denounce it as having zero benefits, with most reporting that assigning homework offers some positive benefits, but also can be detrimental in some areas.

The Effects of Homework

Since opinions vary so drastically, coming to a consensus on homework is nearly impossible. We sent a survey out to parents of a school regarding the topic, asking parents these two basic questions:

- How much time is your child spending working on homework each night?

- Is this amount of time too much, too little, or just right?

The responses varied significantly. In one 3 rd grade class with 22 students, the responses regarding how much time their child spends on homework each night had an alarming disparity. The lowest amount of time spent was 15 minutes, while the largest amount of time spent was 4 hours. Everyone else fell somewhere in between. When discussing this with the teacher, she told me that she sent home the same homework for every child and was blown away by the vastly different ranges in time spent completing it. The answers to the second question aligned with the first. Almost every class had similar, varying results making it really difficult to gauge where we should go as a school regarding homework.

While reviewing and studying my school’s homework policy and the results of the aforementioned survey, I discovered a few important revelations about homework that I think anyone looking at the topic would benefit from:

1. Homework should be clearly defined. Homework is not unfinished classwork that the student is required to take home and complete. Homework is “extra practice” given to take home to reinforce concepts that they have been learning in class. It is important to note that teachers should always give students time in class under their supervision to complete class work. Failing to give them an appropriate amount of class time increases their workload at home. More importantly, it does not allow the teacher to give immediate feedback to the student as to whether or not they are doing the assignment correctly. What good does it do if a student completes an assignment if they are doing it all incorrectly? Teachers must find a way to let parents know what assignments are homework and which ones are classwork that they did not complete.

2. The amount of time required to complete the same homework assignment varies significantly from student to student. This speaks to personalization. I have always been a big fan of customizing homework to fit each individual student. Blanket homework is more challenging for some students than it is for others. Some fly through it, while others spend excessive amounts of time completing it. Differentiating homework will take some additional time for teachers in regards to preparation, but it will ultimately be more beneficial for students.

The National Education Association recommends that students be given 10-20 minutes of homework each night and an additional 10 minutes per advancing grade level. The following chart adapted from the National Education Associations recommendations can be used as a resource for teachers in Kindergarten through the 8 th grade.

|

|

Kindergarten | 5 – 15 minutes |

1 Grade | 10 – 20 minutes |

2 Grade | 20 – 30 minutes |

3 Grade | 30 – 40 minutes |

4 Grade | 40 – 50 minutes |

5 Grade | 50 – 60 minutes |

6 Grade | 60 – 70 minutes |

7 Grade | 70 – 80 minutes |

8 Grade | 80 – 90 minutes |

It can be difficult for teachers to gauge how much time students need to complete an assignment. The following charts serve to streamline this process as it breaks down the average time it takes for students to complete a single problem in a variety of subject matter for common assignment types. Teachers should consider this information when assigning homework. While it may not be accurate for every student or assignment, it can serve as a starting point when calculating how much time students need to complete an assignment. It is important to note that in grades where classes are departmentalized it is important that all teachers are on the same page as the totals in the chart above is the recommended amount of total homework per night and not just for a single class.

Kindergarten – 4th Grade (Elementary Recommendations)

|

|

Single Math Problem | 2 minutes |

English Problem | 2 minutes |

Research Style Questions (i.e. Science) | 4 minutes |

Spelling Words – 3x each | 2 minutes per word |

Writing a Story | 45 minutes for 1-page |

Reading a Story | 3 minutes per page |

Answering Story Questions | 2 minutes per question |

Vocabulary Definitions | 3 minutes per definition |

*If students are required to write the questions, then you will need to add 2 additional minutes per problem. (i.e. 1-English problem requires 4 minutes if students are required to write the sentence/question.)

5th – 8th Grade (Middle School Recommendations)

|

|

Single-Step Math Problem | 2 minutes |

Multi-Step Math Problem | 4 minutes |

English Problem | 3 minutes |

Research Style Questions (i.e. Science) | 5 minutes |

Spelling Words – 3x each | 1 minutes per word |

1 Page Essay | 45 minutes for 1-page |

Reading a Story | 5 minutes per page |

Answering Story Questions | 2 minutes per question |

Vocabulary Definitions | 3 minutes per definition |

*If students are required to write the questions, then you will need to add 2 additional minutes per problem. (i.e. 1-English problem requires 5 minutes if students are required to write the sentence/question.)

Assigning Homework Example

It is recommended that 5 th graders have 50-60 minutes of homework per night. In a self-contained class, a teacher assigns 5 multi-step math problems, 5 English problems, 10 spelling words to be written 3x each, and 10 science definitions on a particular night.

|

|

|

|

Multi-Step Math | 4 minutes | 5 | 20 minutes |

English Problems | 3 minutes | 5 | 15 minutes |

Spelling Words – 3x | 1 minute | 10 | 10 minutes |

Science Definitions | 3 minutes | 5 | 15 minutes |

|

|

3. There are a few critical academic skill builders that students should be expected to do every night or as needed. Teachers should also consider these things. However, they may or may not, be factored into the total time to complete homework. Teachers should use their best judgment to make that determination:

- Independent Reading – 20-30 minutes per day

- Study for Test/Quiz - varies

- Multiplication Math Fact Practice (3-4) – varies - until facts are mastered

- Sight Word Practice (K-2) – varies - until all lists are mastered

4. Coming to a general consensus regarding homework is almost impossible. School leaders must bring everyone to the table, solicit feedback, and come up with a plan that works best for the majority. This plan should be reevaluated and adjusted continuously. What works well for one school may not necessarily be the best solution for another.

- How Much Homework Should Students Have?

- Creating a Homework Policy With Meaning and Purpose

- How to Deal With Late Work and Makeup Work

- Collecting Homework in the Classroom

- Effective Classroom Policies and Procedures

- Innovative Ways to Teach Math

- Essential Strategies to Help You Become an Outstanding Student

- Tips for Teachers to Make Classroom Discipline Decisions

- The 10 Things That Worry Math Teachers the Most

- 4 Tips for Completing Your Homework On Time

- Classroom Assessment Best Practices and Applications

- Appropriate Consequences for Student Misbehavior

- How Teachers Must Handle a "Lazy" Student

- Topics for a Lesson Plan Template

- Tips for Remembering Homework Assignments

- An Overview of Renaissance Learning Programs