Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

1. INTRODUCTION

2. background, 5. discussion, 6. conclusions, author contributions, competing interests, funding information, data availability, how common are explicit research questions in journal articles.

Handling Editor: Ludo Waltman

- Cite Icon Cite

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Mike Thelwall , Amalia Mas-Bleda; How common are explicit research questions in journal articles?. Quantitative Science Studies 2020; 1 (2): 730–748. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00041

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Although explicitly labeled research questions seem to be central to some fields, others do not need them. This may confuse authors, editors, readers, and reviewers of multidisciplinary research. This article assesses the extent to which research questions are explicitly mentioned in 17 out of 22 areas of scholarship from 2000 to 2018 by searching over a million full-text open access journal articles. Research questions were almost never explicitly mentioned (under 2%) by articles in engineering and physical, life, and medical sciences, and were the exception (always under 20%) for the broad fields in which they were least rare: computing, philosophy, theology, and social sciences. Nevertheless, research questions were increasingly mentioned explicitly in all fields investigated, despite a rate of 1.8% overall (1.1% after correcting for irrelevant matches). Other terminology for an article’s purpose may be more widely used instead, including aims, objectives, goals, hypotheses, and purposes, although no terminology occurs in a majority of articles in any broad field tested. Authors, editors, readers, and reviewers should therefore be aware that the use of explicitly labeled research questions or other explicit research purpose terminology is nonstandard in most or all broad fields, although it is becoming less rare.

Academic research is increasingly multidisciplinary, partly due to team research addressing practical problems. There are also now large multidisciplinary journals, such as PLOS ONE and Nature Scientific Reports , with editorial teams that manage papers written by people from diverse disciplinary backgrounds. There is therefore an increasing need for researchers to understand disciplinary norms in writing styles and paradigms. The authors of a research paper need to know how to frame its central contribution so that it is understood by multidisciplinary audiences. One strategy for this is to base an article around a set of explicitly named research questions that address gaps in prior research. Employing the standard phrase “research question” gives an unambiguous signpost for the purpose of an article and may therefore aid clarity. Other strategies include stating hypotheses, goals, or aims, or describing an objective without calling it an objective (e.g., “this paper investigates X”). Similarly, structured abstracts are believed to help readers understand a paper ( Hartley, 2004 ), perhaps partly by having an explicit aim, objective, or goal section. A paper that does not recognize or value the way in which the central contribution is conveyed may be rejected by a reviewer or editor if they are unfamiliar with the norms of the submitting field. It would therefore be helpful for authors, reviewers, and editors to know which research fields employ explicitly labeled research questions or alternative standard terminology.

Purpose statements and research questions or hypotheses are interrelated elements of the research process. Research questions are interrogative statements that reflect the problem to be addressed, usually shaped by the goal or objectives of the study ( Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2006 ). For example, a healthcare article argued that “a good research paper addresses a specific research question. The research question—or study objective or main research hypothesis—is the central organizing principle of the paper” and “the key attributes are: (i) specificity; (ii) originality or novelty; and (iii) general relevance to a broad scientific community” ( Perneger & Hudelson, 2004 ).

The choice of terminology to describe an article’s purpose seems to be conceptually arbitrary, with the final decision based on community norms, journal guidelines, and author style. For example, a research paper investigating issue X could phrase its purpose in the following ways: “research question 1: is X true?,” “this paper aims to investigate X,” “the aim/objective/purpose/goal is to investigate X,” or “X?” (as in the current paper). Implicit purpose statements might include “this paper investigates X” or just “X,” where the context makes clear that this is the purpose. Alternatively, the reader might deduce the purpose of a paper after reading it, with all these options achieving the same result with different linguistic strategies. Some research purposes might not be easily expressible as a research question, however. For example, a humanities paper might primarily discuss an issue (e.g., “Aspects of the monastery and monastic life in Adomnán’s Life of Columba ”) but even these could perhaps be expressed as research questions, if necessary (e.g., “Which are the most noteworthy aspects of the monastery and monastic life in Adomnán’s Life of Columba ?”).

In which fields are explicitly named research questions commonly used?

Has the use of explicitly named research questions increased over time?

Are research purposes addressed using alternative language in different fields?

Do large journals guide authors to use explicitly named research questions or other terminology for purpose statements in different fields?

2.1. Advice for Authors

There are some influential guidelines for reporting academic research. In the social sciences, Swales’ (1990 , 2004) Create A Research Space (CARS) model structures research article introductions in three moves (establishing a territory, establishing a niche, and occupying a niche), which are subdivided into steps. Within the 1990 model, move 3 includes the steps “outlining purposes” and “announcing present research,” but research questions are not explicitly included, being similar the “question raising” step in move 2. In the updated 2004 model, move 3 includes an obligatory step named “announcing present research descriptively and/or purposively” (that joins the steps “outlining purposes” and “announcing present research” from the 1990 model), whereas “listing research questions or hypotheses” is a new optional step.

In medicine, the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative is a checklist of items that should be included to improve reporting quality. One of these is a statement of objectives that “may be formulated as specific hypotheses or as questions that the study was designed to address” or may be less precise in early studies ( Vandenbroucke, von Elm, et al., 2014 ). This description therefore includes stating research questions as one of a range of ways of specifying objectives. An informal advice article in medicine instead starts by arguing that the paper’s aim should be clearly defined ( McIntyrei, Nisbet, et al., 2007 ).

Researchers may also be guided about the language to use in papers by any ethical or other procedures that they need to follow before conducting their work. For example, clinical trials often need to be registered and declared in a standard format, which may include explicit descriptions of objectives (e.g., see “E.2.1: Main objective of the trial” at: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2015-002555-10/GB ).

2.2. Empirical Evidence

Journal article research questions and other purpose statements, such as aims, objectives, goals, and hypotheses ( Shehzad, 2011 ), are usually included within Introduction sections or introductory phases, sometimes appearing as separate sections ( Kwan, 2017 ; Yang & Allison, 2004 ). Some studies have analyzed research article introductions in different disciplines and languages based on the Swales’ (1990 , 2004) CARS model. Although these studies analyze small sets of articles, they seem to agree that the research article introduction structure varies across disciplines (e.g., Joseph, Lim & Nor, 2014 ) and subdisciplines within a discipline, including for engineering ( Kanoksilapatham, 2012 ; Maswana, Kanamaru, & Tajino, 2015 ), applied linguistics ( Jalilifar, 2010 ; Ozturk, 2007 ) and environmental sciences ( Samraj, 2002 ). Introductions in English seem to follow this pattern more closely than introductions in other languages ( Ahamad & Yusof, 2012 ; Hirano, 2009 ; Loi & Evans, 2010 ; Rahimi & Farnia, 2017 ; Sheldon, 2011 ), reflecting cultural differences. Research questions and other purpose terminology, such as aims, objectives, goals, or hypotheses, might also reappear within the Results or Discussion sections ( Amunai & Wannaruk, 2013 ; Brett, 1994 ; Hopkins & Dudley-Evans, 1988 ; Kanoksilapatham, 2005 ).

Previous research has shown that research questions and hypotheses are more common among English-language papers than non-English papers ( Loi & Evans, 2010 ; Mur Dueñas, 2010 ; Omidi & Farnia, 2016 ; Rahimi & Farnia, 2017 ; Sheldon, 2011 ), especially those written by English native speakers ( Sheldon, 2011 ). However, a study analyzing 119 English research article introductions from Iranian and international journals in three subdisciplines within applied linguistics found that “announcing present research” was more used in international journals whereas research questions were proclaimed explicitly more often in local journals ( Jalilifar, 2010 ).

In some fields the verbs examine , determine , evaluate , assess , and investigate are associated with the research purpose ( Cortés, 2013 ; Jalali & Moini, 2014 ; Kanoksilapatham, 2005 ) and the verbs expect , anticipate , and estimate are associated with hypotheses ( Williams, 1999 ). Some computer scientists seem to prefer to write the details of the method(s) used rather than stating the purpose or describing the nature of their research and use assumptions or research questions rather than hypotheses ( Shehzad, 2011 ). Moreover, scholars might state the hypotheses in other ways, such as “it was hypothesized that” ( Jalali & Moini, 2014 ).

A study analyzing lexical bundles (usually phrases) in medical research article introductions showed that the most frequent four-word phrases are related to the research objective, such as “the aim of the,” “aim of the present,” and “study was to evaluate” ( Jalali & Moini, 2014 ). Another study examined lexical bundles in a million-word corpus of research article introductions from several disciplines, showing that the main bundle used to announce the research descriptively and/or purposefully included the terms aim , objective , and purpose (e.g., “the aim of this paper,” “the objective of this study,” “the purpose of this paper”), but no bundles related to research questions or hypotheses were identified ( Cortés, 2013 ).

These findings are in line with other previous studies investigating the structure of research articles, especially the introduction section, which report a much higher percentage of journal papers specifying the research purpose than the research questions or hypotheses across disciplines, regardless of the language in which they are published, with the exception of law articles (see Table 1 ). These studies also show that research questions and hypotheses are much more frequent among social sciences articles (see Table 1 ), which has also been found in other genres, such as PhD theses and Master’s theses (see Table 2 ).

Reference to a wide research purposes, without specifying if they are objectives or RQs/hypotheses.

Restating RQs in the result section.

Note: Studies that have based their analysis on the Swales’s (1990) CARS model ( Anthony, 1999 ; Posteguillo, 1999 ; Mahzari & Maftoon, 2007 ) report the percentage related to “outlining purposes” and “announcing present research.” For these studies, the column “Present the research purpose” reports the higher value. Moreover, for these studies, the value reported in the RQs/hypotheses column refers to the “Question raising” information.

A few studies have focused exclusively on research purposes, research questions, and hypotheses. Some have discussed the development of research questions in qualitative ( Agee, 2009 ) or mixed method ( Onwuegbuzie & Leech, 2006 ) studies, whereas others have examined the ways of constructing research questions or hypotheses within some fields, such as organization studies ( Sandberg & Alvesson, 2011 ) or applied linguistics doctoral dissertations ( Lim, 2014 ; Lim, Loi, & Hashim, 2014 ). Shehzad (2011) examined the strategies and styles employed by computer scientists outlining purposes and listing research questions. She found an increase in the use of research nature or purpose statements and suggested that the “listing research questions or hypotheses” step of Swales’s model was obligatory in computing. No study seems to have examined how often journal guidelines give authors explicit advice about research questions or other purpose statements, however.

The PMC (Pub Med Central) Open Access subset ( www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/tools/openftlist/ ) was downloaded in XML format in November 2018. This is a collection of documents from open access journals or open access articles within hybrid journals. The collection has a biomedical focus, but includes at least a few articles from all broad disciplinary areas. Although a biased subset is not ideal, this is apparently the largest open access collection. Only documents declared in their XML to be of type “research article” were retained for analysis. This excludes many short contributions, such as editorials, that would not need research goals.

The XML of the body section of each article was searched for the test strings “research question,” “RESEARCH QUESTION,” “Research Question,” or “Research question,” recording whether each article contained at least one. This would miss papers exclusively using abbreviations, such as RQ1.

Full body text searches are problematic because terms could be mentioned in other contexts, depending on the part of an article. For example, the phrase “research question” in a literature review section may refer to an article reviewed. For a science-wide analysis it is not possible to be prescriptive about the sections in which a term must occur, however, because there is little uniformity in section names or orders ( Thelwall, 2019 ). Making simplifying assumptions about the position in a text in which a term should appear, such as that a research question should be stated in the first part of an article, would also not be defensible. This is because the structure of articles varies widely between journals and fields. For example, methods can appear at the end rather than the middle, and some papers start with results, with little introduction. There are also international cultural differences in the order in which sections are presented in some fields ( Teufel, 1999 ). The current paper therefore uses full-text searches without any heuristics to restrict the results for transparency and to give an almost certain upper bound to the prevalence of terms, given the lack of a high-quality alternative.

Articles were separated into broad fields using the Science-Metrics public journal classification scheme ( Archambault, Beauchesne, & Caruso, 2011 ), which allocates each journal into exactly one category. This seems to be more precise than the Scopus or Web of Science schemes ( Klavans & Boyack, 2017 ). The Science-Metrics classification was extended by adding the largest 100 journals in the PMC collection that had not been included in the original Science-Metrics classification scheme. These were classified into a Science-Metrics category by first author based on their similarity to other journals in the Science-Metrics scheme.

Five of the broad fields had too little data to be useful (Economics & Business; Visual & Performing Arts; Communication & Text Studies; General Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences; Built Environment & Design) and were removed. Years before 2000 were not included because of their age and small amount of data. Individual field/year combinations were also removed when there were fewer than 30 articles, since they might give a misleading percentage. Each of the 17 remaining categories contained at least 630 articles ( Table 3 ), with exact numbers for each field and year available in the online supplementary material (columns AE to AW: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10274012 ). For all broad fields, most articles have been published in the last 5 years (2014–2018), with the exception of Historical Studies, Chemistry, and Enabling & Strategic Technology.

For the third research question, alternative terms for research goals were searched for in the full text of articles. These terms might all be used in different contexts, so a match is not necessarily related to the main goal of the paper (e.g., the term “question” could be part of a discussion of a questionnaire), but the rank order between disciplines may be informative and the results serve as an upper bound for valid uses. The terms searched for were “research questions,” “questions,” “hypotheses,” “aims,” “objectives,” “goals,” and “purposes” in both singular and plural forms. These have been identified above as performing similar functions in research. For this exploration, the term “question” is used in addition to “research question” to capture more general uses.

Any of the queried terms could be included in an article out of context. For example, “research question” could be mentioned in a literature review rather than to describe the purpose of the new article. To check the context in which each term was used, a random sample of 100 articles (using a random number generator) matching each term (200 for each concept, counting both singular and plural, totaling 1,400 checks) was manually examined to ascertain whether any use of the term in the article stated the purpose of the paper directly (e.g., “Our research questions were…”) or indirectly (e.g., “This answered our research questions”), unless mentioned peripherally as information to others (e.g., “The study research questions were explained to interviewees”). There did not seem to be stock phrases that could be used to eliminate a substantial proportion of the irrelevant matches (e.g., “objective function” or “microscope objective”). There also was not a set of standard phrases that collectively could unambiguously identify the vast majority of research questions (e.g., “Our research questions were” or “This article’s research question is”).

Journal guidelines given to authors were manually analyzed to check whether they give advice about research questions and other purpose statements. Three journals with the most articles in each of the 17 academic fields were selected for this (see online supplement doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10274012 ). This information is useful background context to help interpret the results.

4.1. RQ1 and RQ2: Articles Mentioning Research Questions

Altogether, 23,282 out of 1,314,412 articles explicitly mentioned the phrases “research question” or “research questions” (1.8%), although no field included them in more than a fifth of articles in recent years and there are substantial differences between broad fields ( Figure 1 ). When the terms are used in an article they usually (63%, from the 1,400 manual checks) refer to the article’s main research question(s). Other uses of these terms include referring to questions raised by the findings, and a discussion of other articles’ research questions in literature review sections or as part of the selection criteria of meta-analyses. Thus, overall, only 1.1% of PMC full-text research articles mention their research questions explicitly using the singular or plural form. There has been a general trend for the increasing use of these terms, however ( Figure 2 ).

The percentage of full-text research articles containing the phrases “research question” or “research questions” in the body of the text, 2014–2018, for articles in the PMC Open Access collection from 17 out of 22 Science-Metrics broad fields; 63% of occurrences of these terms described the hosting article’s research question(s) ( n = 801,895 research articles).

As for Figure 1 but covering 2000–2018 ( n = 1,314,412 research articles). (All fields can be identified in the Excel versions of the graph within the online supplement 10.6084/m9.figshare.10274012).

If the terms “question” or “questions” are searched for instead, there are many more matches, although for a minority of articles in most fields ( Figures 3 and 4 ). When these terms are mentioned, they rarely (17%) refer to the hosting article’s research questions (excluding matches with the exact phrases “research question” or “research questions” to avoid overlaps with the previous figure). Common other contexts for these terms include questions in questionnaires and questions raised by the findings. Sometimes the term “question” occurred within an idiomatic phrase or issue rather than a query (e.g., “considerable temperature gradients occur within the materials in question” and “these effects may vary for different medications. Future studies are needed to address this important question”). In Philosophy & Theology, the matches could be for discussions of various questions within an article, rather than a research question that is an article’s focus. Similarly for Social Sciences and Public Health & Health Services, the question mentioned might be in questionnaires rather than being a research question. After correcting for the global irrelevant matches, which is a rough approximation, in all broad fields fewer than 14% of research articles use these terms to refer to research questions. Nevertheless, this implies that the terms “question” or “questions” are used much more often than the phrases “research question” or “research questions” (1.8%) to refer to an article’s research purposes.

The percentage of full-text research articles containing the terms “question” or “questions” in the body of the text, 2014–2018, for articles in the PMC Open Access collection from 17 out of 22 Science-Metrics broad fields; 17% of occurrences of these terms described the hosting article’s main research question(s) without using the exact phrases “research question” or “research questions,” not overlapping with Figure 1(a) ( n = 801,895 research articles).

As for Figure 3 , but covering 2000–2018 ( n = 1,314,412 research articles).

4.2. RQ3: Other Article Purpose Terms

The terms “hypothesis” and “hypotheses” are common in Psychology and Cognitive Science as well as in Biology ( Figure 5 ). They are used in a minority of articles in all other fields, but, by 2018 were used in at least 15% of all (or 4% after correcting for irrelevant matches). The terms can be used to discuss statistical results from other papers and in philosophy and mathematics they can be used to frame arguments, so not all matches relate to an article’s main purpose, and only 28% of the random sample checked used the terms to refer to the articles’ main hypothesis or hypotheses.

The percentage of full-text research articles containing the terms “hypothesis” or “hypotheses” in the body of the text, 2014–2018, for articles in the PMC Open Access collection from 17 out of 22 Science-Metrics broad fields; 28% of occurrences of these terms described the hosting article’s main hypothesis or hypotheses. A corresponding time series graph showing little change is in the online supplement ( n = 801,895 research articles).

The use of the terms “aim” and “aims” is increasing overall, possibly in all academic fields ( Figures 6 and 7 ). Fields frequently using the term include Philosophy & Theology, Information & Communication Technologies (ICTs) and Public Health & Health Services, whereas it is used in only about 20% of Chemistry and Biomedical Research papers. Articles using the terms mostly use them (especially the singular “aim”) to describe their main aim (70%), so these are the terms most commonly used to describe the purpose of a PMC full-text article. The terms are also sometimes used to refer to wider project aims or relevant aims outside of the project (e.g., “The EU’s biodiversity protection strategy aims to preserve…”).

The percentage of full-text research articles containing the terms “aim” or “aims” in the body of the text, 2014–2018, for articles in the PMC Open Access collection from 17 out of 22 Science-Metrics broad fields; 70% of occurrences of these terms described the hosting article’s main aim(s) ( n = 801,895 research articles).

As for Figure 6 , but covering 2000–2018 ( n = 1,314,412 research articles).

The terms “objective” and “objectives” are reasonably common in most academic fields ( Figure 8 ) and are used half of the time (52%) for the hosting article’s objectives. Other common uses include lenses and as an antonym of subjective (e.g., “high-frequency ultrasound allows an objective assessment…”). It is again popular within ICTs, Philosophy & Theology, and Public Health & Health Services, whereas it is used in only about 12% of Physics & Astronomy articles.

The percentage of full-text research articles containing the terms “objective” or “objectives” in the body of the text, 2014–2018, for articles in the PMC Open Access collection from 17 out of 22 Science-Metrics broad fields; 52% of occurrences of these terms described the hosting article’s objective(s). A corresponding time series graph showing little change is in the online supplement ( n = 801,895 research articles).

The terms “goal” and “goals” follow a similar pattern to “aim” and “objective” ( Figure 9 ), but refer to the hosting paper’s goals in only 28% of cases. Common other uses include methods goals (“the overall goal of this protocol is…”) and field-wide goals (e.g., “over the last decades, attempts to integrate ecological and evolutionary dynamics have been the goal of many studies”).

The percentage of full-text research articles containing the terms “goal” or “goals” in the body of the text, 2014–2018, for articles in the PMC Open Access collection from 17 out of 22 Science-Metrics broad fields; 28% of occurrences of these terms described the hosting article’s research question(s). A corresponding time series graph showing little change is in the online supplement ( n = 801,895 research articles).

Some articles may also use the terms “purpose” or “purposes” rather than the arguably more specific terms investigated above, and there are disciplinary differences in the extent to which they are used ( Figure 10 ). These terms may also be employed to explain or justify aspects of an article’s methods. When used, they referred to main purposes in fewer than a third of articles (29%), and were often instead used to discuss methods details (e.g., “it was decided a priori that physical examination measures would not be collected for the purpose of this audit”), background information (e.g., “species are harvested through fishing or hunting, mainly for alimentary purposes”) or ethics (e.g., “Animal care was carried out in compliance with Korean regulations regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes.”).

The percentage of full-text research articles containing the terms “purpose” or “purposes” in the body of the text, 2014–2018, for articles in the PMC Open Access collection from 17 out of 22 Science-Metrics broad fields; 29% of occurrences of these terms described the hosting article’s purpose(s). A corresponding time series graph showing little change is in the online supplement ( n = 801,895 research articles).

4.3. RQ4: Journal Guidelines

“The motivation or purpose of your research should appear in the Introduction, where you state the questions you sought to answer” ( zookeys.pensoft.net/about )

“Define the purpose of the work and its significance, including specific hypotheses being tested” ( www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients/instructions )

“The introduction briefly justifies the research and specifies the hypotheses to be tested” ( www.ajas.info/authors/authors.php )

“A brief outline of the question the study attempts to address” ( onlinelibrary.wiley.com/page/journal/20457758/homepage/registeredreports.html )

“Acquaint the reader with the findings of others in the field and with the problem or question that the investigation addresses.” ( www.oncotarget.com )

“State the research objective of the study, or hypothesis tested” ( www.springer.com/biomed/human+physiology/journal/11517 )

In the first quote above, for example, “state the questions” could be addressed literally by listing (research) questions or less literally by stating the research objectives. Thus, journal guidelines seem to leave authors the flexibility to choose how to state their research purpose, even if suggesting that research questions or hypotheses are used. This also applies to the influential American Psychological Society guidelines, such as, “In empirical studies, [explaining your approach to solving the problem] usually involves stating your hypotheses or specific question” ( APA, 2009 , p. 28).

An important limitation of the methods is that the sample contains a small and biased subset of all open access research articles. For example, the open access publishers BMC, Hindawi, and MDPI have large journals in the data set. The small fields ( Table 3 ) can have unstable lines in the graphs because of a lack of data. Sharp changes between years for the same field are likely due to either small amounts of data or changes in the journals submitted to PubMed in those years, rather than changes in field norms. It is possible that the proportions discovered would be different for other collections. Another limitation is that although articles were searched with the text string “research question,” this may not always have signified research questions in the articles processed (e.g., if mentioned in a literature review or in a phrase such as “this research questions whether”). Although the corrections reported address this, they provide global correction figures rather than field-specific corrections. Conversely, a research question may just be described as a question (e.g., “the query of this research”) or phrased as a question without describing it as such (e.g., “To discover whether PGA implants are immunologically inert…”). Thus, the field-level results are only indicative.

RQ1: Only 23,282 (1.8%, 1.1% after correcting for irrelevant matches) out of 1,314,412 articles assessed in the current paper explicitly mentioned “research question(s),” with significant differences between fields. Although there has been a general trend for the increasing use of explicitly named research questions, they were employed in fewer than a quarter of articles in all fields. Research questions were mostly used by articles in Social Sciences, Philosophy & Theology, and ICTs, whereas they have been mentioned by under 2% of articles in engineering, physical, life, and medical sciences. Previous studies have shown that 73.3% of English articles in Physical Education ( Omidi & Farnia, 2016 ), 33% of Applied Linguistics articles ( Sheldon, 2011 ) and 32% of Computer Science articles ( Shehzad, 2011 ) included research questions or hypotheses. Studies focused on doctoral dissertations show that 97% of U.S. Applied Linguistics ( Lim, 2014 ), 90% of English Language Teaching ( Geçíklí, 2013 ), 70% of Education Management ( Cheung, 2012 ), and 50% of computing doctoral dissertations ( Soler-Monreal, Carbonell-Olivares, & Gil-Salom, 2011 ) listed research questions, a large difference.

The results also show that about 13% of Public Health and Health Services articles and 12% of Psychology and Cognitive Science articles use the term “research questions.” However, a study focused on Educational Psychology found that 35% of English-language papers listed research questions and 75% listed hypotheses ( Loi & Evans, 2010 ). Thus, the current results reveal a substantially lower overall prevalence than suggested by previous research.

RQ2: There has been a substantial increase in the use of the term “research questions” in some subjects, including ICTs, Social Sciences, and Public Health and Health Services ( Figure 2 ), as well as a general trend for increasing use of this term, but with most fields still rarely using it. This suggests that some disciplines are standardizing their terminology, either through author guidelines in journals (RQ4), formal training aided by frameworks such as Swales’ CARS model, or informal training or imitation. For example, the analysis of the “instructions for authors” given by 51 journals (online supplement doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10274012 ) showed that the three biology journals, the three psychology journals, and two biomedical journals included in the analysis referred to both research questions and hypotheses in their author guidelines.

RQ3: Terminology for the purpose of an article seems to be quite widely used, including aims, objectives, and goals ( Figures 5 – 9 ). This is in line with a study examining the lexical bundles identified in research article introductions from several disciplines, which reported the terms “aim,” “objective,” and “purpose” as the main terms used to announce the research descriptively and/or purposefully, although no phrase related to research questions or hypotheses was identified ( Cortés, 2013 ), and with another study reporting similar terminology in medical articles ( Jalali & Moini, 2014 ). Related to this (RQ4), the analysis of the “instructions for authors” given by 51 journals (online supplement 10.6084/m9.figshare.10274012) showed that “purpose” is the term mostly mentioned in the Abstract guidelines and “aims” is the term mainly used in the body of the text (Introduction or Background) guidelines. The term “objective” also appears in some article body guidelines, whereas the term “goal” is not mentioned in them. After correcting for irrelevant matches (e.g., articles using the term “hypothesis” but not for their main research hypotheses) using the percentages reported with the figures above, no terminology was found in a majority of articles in any field. Thus, at least from the perspective of PMC Open Access publications, there is no standardization of research terminology in any broad field.

There are substantial disciplinary differences in the terminology used. Whereas the term “research question” is relevant in Social Sciences, Philosophy & Theology, and ICTs, the term “hypothesis” is important in Psychology and Cognitive Science, used in over 60% of articles. This is in line with a study focused on Educational Psychology, which found that the 75% out of 20 English papers introduced the hypotheses, whereas 35% of them introduced the research questions ( Loi & Evans, 2010 ). The three psychology journals with the highest frequency in the data set used for this study referred to hypotheses in their author guidelines (see online supplement 10.6084/m9.figshare.10274012).

The terms “aim,” “objective,” and “goal” are mainly used in Philosophy, Theology, ICTs, and Health. The term “aim” is also quite often used in health, mathematics, and psychological articles, whereas the term “objective” is also used in engineering and mathematics articles. The term “goal” is also used in psychology and biomedical articles. Although most articles in all fields include a term that could be used to specify the purpose of an article (question or questions, hypothesis, aim, objective, goal), they are relatively scarce in Chemistry and Physics & Astronomy. The use of purpose-related terms has also increased over time in most academic fields. This agrees with a study about Computer Science research articles that found an increasing use of outlining purpose or stating the nature of the research ( Shehzad, 2011 ).

An example article from Chemistry illustrates how a research purpose can be implicit. The paper, “Fluid catalytic cracking in a rotating fluidized bed in a static geometry: a CFD analysis accounting for the distribution of the catalyst coke content” has a purpose that is clear from its title but that is not described explicitly in the text. Its abstract starts by describing what the paper offers, but not why, “Computational Fluid Dynamics is used to evaluate the use of a rotating fluidized bed in a static geometry for the catalytic cracking of gas oil.” The first sentence of the last paragraph of the introduction performs a similar role, “The current paper presents CFD simulations of FCC in a RFB-SG using a model that accounts for a possible nonuniform temperature and catalyst coke content distribution in the reactor.” Both sentences could easily be rephrased to start with, “The purpose of this paper is to,” but it is apparently a stylistic feature of chemical research not to do this. Presumably purposes are clear enough in typical chemistry research that they do not need to be flagged linguistically, but this is untrue for much social science and health research, for example, partly due to nonstandard goals (i.e., task uncertainty: Whitley, 2000 ).

5.1. Possible Origins of the Differences Found

Broad epistemological: Fields work with knowledge in different ways and naturally use different terminology as a result. Arts and humanities research may have the goal to critique or analyze, or may be practice-based research rather than having a more specific knowledge purpose. For this, research questions would be inappropriate. Thus, terminology variation may partly reflect the extent to which a broad field typically attempts to create knowledge.

Narrow epistemological: Narrow fields that address similar problems may feel that they do not need to use research problem terminology to describe their work because the purpose of a paper is usually transparent from the description of the methods or outcome. For example, it would be unnecessary to formulate, “This paper investigates whether treatment x reduces death rates from disease y” as a named research question or even explain that it is the goal of a paper. This may also be relevant for fields that write short papers. It may be most relevant for papers that use statistical methods and have high standards of evidence requirement (e.g., medicine) and clearly defined problems. In contrast, many social sciences research projects are not intrinsically clearly demarcated and need an explanation to define the problem (as for the current article). Thus, describing what the problem is can be an important and nontrivial part of the research. This relates to “task uncertainty,” which varies substantially between fields ( Whitley, 2000 ) and affects scholarly communication ( Fry, 2006 ).

Field or audience homogeneity: Fields with homogeneous levels and types of expertise may avoid terminology that field members would be able to deduce from the context. For example, a mixed audience paper might need to specify statistical hypotheses, whereas a narrow audience paper might only need to specify the result, because the audience would understand the implicit null and alternative hypotheses.

Field cultures for term choice: Academic publishing relies to some extent on imitation and reaching a consensus about the ways in which research is presented (e.g., Becher & Trowler, 2001 ). It might therefore become a field norm to use one term in preference to a range of synonyms, such as “aims” instead of “objectives.”

Field cultures for term meaning: Following from the above, a field culture may evolve an informal convention that two synonyms have different specific uses. For example, “aims” could be used for wider goals and “objectives” for the narrower goals of a paper.

Guidelines: Fields or their core journals may adopt guidelines that specify terminology, presumably because they believe that this standardization will improve overall communication clarity.

The results suggest that the explicit use of research questions, in the sense that they are named as such, is almost completely absent in some research fields, and they are at best a substantial minority (under 20%) in most others (ignoring the fields that did not meet the inclusion threshold). Although the word search approach does not give conclusive findings, the results suggest that alternative terminologies for describing the purpose of a paper are more widespread in some fields, but no single terminology is used to describe research purposes in a majority of articles in any of the broad fields examined.

The lack of standardization for purpose terminology in most or all fields may cause problems for reviewers and readers expecting to see explicit statements. It is not clear whether guidelines to standardize terminology for journals or fields would be practical or helpful, however, but this should be explored in the future. Presumably any guidelines should allow exceptions for articles that make nonstandard contributions, although there are already successful journals with prescriptive guidelines, and the advantage of standardization through structured abstracts seems to be accepted ( Hartley, 2004 ).

The disciplinary differences found may cause problems for referees, authors, editors, and readers of interdisciplinary research or research from outside of their natural field if they fail to find an article’s purpose expressed in the terminology that they expect. This issue could not reasonably be resolved by standardizing across science because of the differing nature of research. Instead, evidence in the current article of the existence of valid disciplinary differences in style may help reviewers and editors of large interdisciplinary journals to accept stylistic differences in research problem formulations.

Mike Thelwall: Conceptualization, Investigation, Software, Writing—original draft. Amalia Mas-Bleda: Investigation, Writing—original draft.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

This research received no funding.

The data behind the results are available at FigShare ( https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10274012 ).

Author notes

Email alerts, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 2641-3337

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Open Access

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Examples of Good and Bad Research Questions

#scribendiinc

Written by Scribendi

So, you've got a research grant in your sights or you've been admitted to your school of choice, and you now have to write up a proposal for the work you want to perform. You know your topic, have done some reading, and you've got a nice quiet place where nobody will bother you while you try to decide where you'll go from here. The question looms:

What Is a Research Question?

Your research question will be your focus, the sentence you refer to when you need to remember why you're researching. It will encapsulate what drives you and be something your field needs an answer for but doesn't have yet.

Whether it seeks to describe a phenomenon, compare things, or show how one variable influences another, a research question always does the same thing: it guides research that will be judged based on how well it addresses the question.

So, what makes a research question good or bad? This article will provide examples of good and bad research questions and use them to illustrate both of their common characteristics so that you can evaluate your research question and improve it to suit your needs.

How to Choose a Research Question

At the start of your research paper, you might be wondering, "What is a good research question?"

A good research question focuses on one researchable problem relevant to your subject area.

To write a research paper , first make sure you have a strong, relevant topic. Then, conduct some preliminary research around that topic. It's important to complete these two initial steps because your research question will be formulated based on this research.

With this in mind, let's review the steps that help us write good research questions.

1. Select a Relevant Topic

When selecting a topic to form a good research question, it helps to start broad. What topics interest you most? It helps when you care about the topic you're researching!

Have you seen a movie recently that you enjoyed? How about a news story? If you can't think of anything, research different topics on Google to see which ones intrigue you the most and can apply to your assignment.

Also, before settling on a research topic, make sure it's relevant to your subject area or to society as a whole. This is an important aspect of developing your research question, because, in general, your research should add value to existing knowledge .

2. Thoroughly Research the Topic

Now that you've chosen a broad but relevant topic for your paper, research it thoroughly to see which avenues you might want to explore further.

For example, let's say you decide on the broad topic of search engines. During this research phase, try skimming through sources that are unbiased, current, and relevant, such as academic journals or sources in your university library.

Check out: 21 Legit Research Databases for Free Articles in 2022

Pay close attention to the subtopics that come up during research, such as the following: Which search engines are the most commonly used? Why do some search engines dominate specific regions? How do they really work or affect the research of scientists and scholars?

Be on the lookout for any gaps or limitations in the research. Identifying the groups or demographics that are most affected by your topic is also helpful, in case that's relevant to your work.

3. Narrow Your Topic to a Single Point

Now that you've spent some time researching your broad topic, it's time to narrow it down to one specific subject. A topic like search engines is much too broad to develop a research paper around. What specifically about search engines could you explore?

When refining your topic, be careful not to be either too narrow or too broad. You can ask yourself the following questions during this phase:

Can I cover this topic within the scope of my paper, or would it require longer, heavier research? (In this case, you'd need to be more specific.)

Conversely, is there not enough research about my topic to write a paper? (In this case, you'd need to be broader.)

Keep these things in mind as you narrow down your topic. You can always expand your topic later if you have the time and research materials.

4. Identify a Problem Related to Your Topic

When narrowing down your topic, it helps to identify a single issue or problem on which to base your research. Ask open-ended questions, such as why is this topic important to you or others? Essentially, have you identified the answer to "so what"?

For example, after asking these questions about our search engine topic, we might focus only on the issue of how search engines affect research in a specific field. Or, more specifically, how search engine algorithms manipulate search results and prevent us from finding the critical research we need.

Asking these "so what" questions will help us brainstorm examples of research questions we can ask in our field of study.

5. Turn Your Problem into a Question

Now that you have your main issue or problem, it's time to write your research question. Do this by reviewing your topic's big problem and formulating a question that your research will answer.

For example, ask, "so what?" about your search engine topic. You might realize that the bigger issue is that you, as a researcher, aren't getting the relevant information you need from search engines.

How can we use this information to develop a research question? We might phrase the research question as follows:

"What effect does the Google search engine algorithm have on online research conducted in the field of neuroscience?"

Note how specific we were with the type of search engine, the field of study, and the research method. It's also important to remember that your research question should not have an easy yes or no answer. It should be a question with a complex answer that can be discovered through research and analysis.

Perfect Your Paper

Hire an expert academic editor , or get a free sample, how to find good research topics for your research.

It can be fun to browse a myriad of research topics for your paper, but there are a few important things to keep in mind.

First, make sure you've understood your assignment. You don't want to pick a topic that's not relevant to the assignment goal. Your instructor can offer good topic suggestions as well, so if you get stuck, ask them!

Next, try to search for a broad topic that interests you. Starting broad gives you more options to work with. Some research topic examples include infectious diseases, European history, and smartphones .

Then, after some research, narrow your topic to something specific by extracting a single element from that subject. This could be a current issue on that topic, a major question circulating around that topic, or a specific region or group of people affected by that topic.

It's important that your research topic is focused. Focus lets you clearly demonstrate your understanding of the topic with enough details and examples to fit the scope of your project.

For example, if Jane Austen is your research topic, that might be too broad for a five-page paper! However, you could narrow it down to a single book by Austen or a specific perspective.

To keep your research topic focused, try creating a mind map. This is where you put your broad topic in a circle and create a few circles around it with similar ideas that you uncovered during your research.

Mind maps can help you visualize the connections between topics and subtopics. This could help you simplify the process of eliminating broad or uninteresting topics or help you identify new relationships between topics that you didn't previously notice.

Keeping your research topic focused will help you when it comes to writing your research question!

2. Researchable

A researchable question should have enough available sources to fill the scope of your project without being overwhelming. If you find that the research is never-ending, you're going to be very disappointed at the end of your paper—because you won't be able to fit everything in! If you are in this fix, your research question is still too broad.

Search for your research topic's keywords in trusted sources such as journals, research databases , or dissertations in your university library. Then, assess whether the research you're finding is feasible and realistic to use.

If there's too much material out there, narrow down your topic by industry, region, or demographic. Conversely, if you don't find enough research on your topic, you'll need to go broader. Try choosing two works by two different authors instead of one, or try choosing three poems by a single author instead of one.

3. Reasonable

Make sure that the topic for your research question is a reasonable one to pursue. This means it's something that can be completed within your timeframe and offers a new perspective on the research.

Research topics often end up being summaries of a topic, but that's not the goal. You're looking for a way to add something relevant and new to the topic you're exploring. To do so, here are two ways to uncover strong, reasonable research topics as you conduct your preliminary research:

Check the ends of journal articles for sections with questions for further discussion. These make great research topics because they haven't been explored!

Check the sources of articles in your research. What points are they bringing up? Is there anything new worth exploring? Sometimes, you can use sources to expand your research and more effectively narrow your topic.

4. Specific

For your research topic to stand on its own, it should be specific. This means that it shouldn't be easily mistaken for another topic that's already been written about.

If you are writing about a topic that has been written about, such as consumer trust, it should be distinct from everything that's been written about consumer trust so far.

There is already a lot of research done on consumer trust in specific products or services in the US. Your research topic could focus on consumer trust in products and services in a different region, such as a developing country.

If your research feels similar to existing articles, make sure to drive home the differences.

Whether it's developed for a thesis or another assignment, a good research topic question should be complex enough to let you expand on it within the scope of your paper.

For example, let's say you took our advice on researching a topic you were interested in, and that topic was a new Bridezilla reality show. But when you began to research it, you couldn't find enough information on it, or worse, you couldn't find anything scholarly.

In short, Bridezilla reality shows aren't complex enough to build your paper on. Instead of broadening the topic to all reality TV shows, which might be too overwhelming, you might consider choosing a topic about wedding reality TV shows specifically.

This would open you up to more research that could be complex enough to write a paper on without being too overwhelming or narrow.

6. Relevant

Because research papers aim to contribute to existing research that's already been explored, the relevance of your topic within your subject area can't be understated.

Your research topic should be relevant enough to advance understanding in a specific area of study and build on what's already been researched. It shouldn't duplicate research or try to add to it in an irrelevant way.

For example, you wouldn't choose a research topic like malaria transmission in Northern Siberia if the mosquito that transmits malaria lives in Africa. This research topic simply isn't relevant to the typical location where malaria is transmitted, and the research could be considered a waste of resources.

Do Research Questions Differ between the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Hard Sciences?

The art and science of asking questions is the source of all knowledge.

–Thomas Berger

First, a bit of clarification: While there are constants among research questions, no matter what you're writing about, you will use different standards for the humanities and social sciences than for hard sciences, such as chemistry. The former depends on subjectivity and the perspective of the researcher, while the latter requires answers that must be empirically tested and replicable.

For instance, if you research Charles Dickens' writing influences, you will have to explain your stance and observations to the reader before supporting them with evidence. If you research improvements in superconductivity in room-temperature material, the reader will not only need to understand and believe you but also duplicate your work to confirm that you are correct.

Do Research Questions Differ between the Different Types of Research?

Research questions help you clarify the path your research will take. They are answered in your research paper and usually stated in the introduction.

There are two main types of research—qualitative and quantitative.

If you're conducting quantitative research, it means you're collecting numerical, quantifiable data that can be measured, such as statistical information.

Qualitative research aims to understand experiences or phenomena, so you're collecting and analyzing non-numerical data, such as case studies or surveys.

The structure and content of your research question will change depending on the type of research you're doing. However, the definition and goal of a research question remains the same: a specific, relevant, and focused inquiry that your research answers.

Below, we'll explore research question examples for different types of research.

Comparative Research

Comparative research questions are designed to determine whether two or more groups differ based on a dependent variable. These questions allow researchers to uncover similarities and differences between the groups tested.

Because they compare two groups with a dependent variable, comparative research questions usually start with "What is the difference in…"

A strong comparative research question example might be the following:

"What is the difference in the daily caloric intake of American men and women?" ( Source .)

In the above example, the dependent variable is daily caloric intake and the two groups are American men and women.

A poor comparative research example might not aim to explore the differences between two groups or it could be too easily answered, as in the following example:

"Does daily caloric intake affect American men and women?"

Always ensure that your comparative research question is focused on a comparison between two groups based on a dependent variable.

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research questions help you gather data about measurable variables. Typically, researchers asking descriptive research questions aim to explain how, why, or what.

These research questions tend to start with the following:

What percentage?

How likely?

What proportion?

For example, a good descriptive research question might be as follows:

"What percentage of college students have felt depressed in the last year?" ( Source .)

A poor descriptive research question wouldn't be as precise. This might be something similar to the following:

"What percentage of teenagers felt sad in the last year?"

The above question is too vague, and the data would be overwhelming, given the number of teenagers in the world. Keep in mind that specificity is key when it comes to research questions!

Correlational Research

Correlational research measures the statistical relationship between two variables, with no influence from any other variable. The idea is to observe the way these variables interact with one another. If one changes, how is the other affected?

When it comes to writing a correlational research question, remember that it's all about relationships. Your research would encompass the relational effects of one variable on the other.

For example, having an education (variable one) might positively or negatively correlate with the rate of crime (variable two) in a specific city. An example research question for this might be written as follows:

"Is there a significant negative correlation between education level and crime rate in Los Angeles?"

A bad correlational research question might not use relationships at all. In fact, correlational research questions are often confused with causal research questions, which imply cause and effect. For example:

"How does the education level in Los Angeles influence the crime rate?"

The above question wouldn't be a good correlational research question because the relationship between Los Angeles and the crime rate is already inherent in the question—we are already assuming the education level in Los Angeles affects the crime rate in some way.

Be sure to use the right format if you're writing a correlational research question.

How to Avoid a Bad Question

Ask the right questions, and the answers will always reveal themselves.

–Oprah Winfrey

If finding the right research question was easy, doing research would be much simpler. However, research does not provide useful information if the questions have easy answers (because the questions are too simple, narrow, or general) or answers that cannot be reached at all (because the questions have no possible answer, are too costly to answer, or are too broad in scope).

For a research question to meet scientific standards, its answer cannot consist solely of opinion (even if the opinion is popular or logically reasoned) and cannot simply be a description of known information.

However, an analysis of what currently exists can be valuable, provided that there is enough information to produce a useful analysis. If a scientific research question offers results that cannot be tested, measured, or duplicated, it is ineffective.

Bad Research Question Examples

Here are examples of bad research questions with brief explanations of what makes them ineffective for the purpose of research.

"What's red and bad for your teeth?"

This question has an easy, definitive answer (a brick), is too vague (What shade of red? How bad?), and isn't productive.

"Do violent video games cause players to act violently?"

This question also requires a definitive answer (yes or no), does not invite critical analysis, and allows opinion to influence or provide the answer.

"How many people were playing balalaikas while living in Moscow on July 8, 2019?"

This question cannot be answered without expending excessive amounts of time, money, and resources. It is also far too specific. Finally, it doesn't seek new insight or information, only a number that has no conceivable purpose.

How to Write a Research Question

The quality of a question is not judged by its complexity but by the complexity of thinking it provokes.

–Joseph O'Connor

What makes a good research question? A good research question topic is clear and focused. If the reader has to waste time wondering what you mean, you haven't phrased it effectively.

It also needs to be interesting and relevant, encouraging the reader to come along with you as you explain how you reached an answer.

Finally, once you explain your answer, there should be room for astute or interested readers to use your question as a basis to conduct their own research. If there is nothing for you to say in your conclusion beyond "that's the truth," then you're setting up your research to be challenged.

Good Research Question Examples

Here are some examples of good research questions. Take a look at the reasoning behind their effectiveness.

"What are the long-term effects of using activated charcoal in place of generic toothpaste for routine dental care?"

This question is specific enough to prevent digressions, invites measurable results, and concerns information that is both useful and interesting. Testing could be conducted in a reasonable time frame, without excessive cost, and would allow other researchers to follow up, regardless of the outcome.

"Why do North American parents feel that violent video game content has a negative influence on their children?"

While this does carry an assumption, backing up that assumption with observable proof will allow for analysis of the question, provide insight on a significant subject, and give readers something to build on in future research.

It also discusses a topic that is recognizably relevant. (In 2022, at least. If you are reading this article in the future, there might already be an answer to this question that requires further analysis or testing!)

"To what extent has Alexey Arkhipovsky's 2013 album, Insomnia , influenced gender identification in Russian culture?"

While it's tightly focused, this question also presents an assumption (that the music influenced gender identification) and seeks to prove or disprove it. This allows for the possibilities that the music had no influence at all or had a demonstrable impact.

Answering the question will involve explaining the context and using many sources so that the reader can follow the logic and be convinced of the author's findings. The results (be they positive or negative) will also open the door to countless other studies.

How to Turn a Bad Research Question into a Good One

If something is wrong, fix it if you can. But train yourself not to worry. Worry never fixes anything.

–Ernest Hemingway

How do you turn something that won't help your research into something that will? Start by taking a step back and asking what you are expected to produce. While there are any number of fascinating subjects out there, a grant paying you to examine income disparity in Japan is not going to warrant an in-depth discussion of South American farming pollution.

Use these expectations to frame your initial topic and the subject that your research should be about, and then conduct preliminary research into that subject. If you spot a knowledge gap while researching, make a note of it, and add it to your list of possible questions.

If you already have a question that is relevant to your topic but has flaws, identify the issues and see if they can be addressed. In addition, if your question is too broad, try to narrow it down enough to make your research feasible.

Especially in the sciences, if your research question will not produce results that can be replicated, determine how you can change it so a reader can look at what you've done and go about repeating your actions so they can see that you are right.

Moreover, if you would need 20 years to produce results, consider whether there is a way to tighten things up to produce more immediate results. This could justify future research that will eventually reach that lofty goal.

If all else fails, you can use the flawed question as a subtopic and try to find a better question that fits your goals and expectations.

Parting Advice

When you have your early work edited, don't be surprised if you are told that your research question requires revision. Quite often, results or the lack thereof can force a researcher to shift their focus and examine a less significant topic—or a different facet of a known issue—because testing did not produce the expected result.

If that happens, take heart. You now have the tools to assess your question, find its flaws, and repair them so that you can complete your research with confidence and publish something you know your audience will read with fascination.

Of course, if you receive affirmation that your research question is strong or are polishing your work before submitting it to a publisher, you might just need a final proofread to ensure that your confidence is well placed. Then, you can start pursuing something new that the world does not yet know (but will know) once you have your research question down.

Master Your Research with Professional Editing

About the author.

Scribendi's in-house editors work with writers from all over the globe to perfect their writing. They know that no piece of writing is complete without a professional edit, and they love to see a good piece of writing transformed into a great one. Scribendi's in-house editors are unrivaled in both experience and education, having collectively edited millions of words and obtained nearly 20 degrees. They love consuming caffeinated beverages, reading books of various genres, and relaxing in quiet, dimly lit spaces.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

21 Legit Research Databases for Free Journal Articles in 2024

How to Research a Term Paper

How to Write a Research Proposal

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Question: Types and Examples

The first step in any research project is framing the research question. It can be considered the core of any systematic investigation as the research outcomes are tied to asking the right questions. Thus, this primary interrogation point sets the pace for your research as it helps collect relevant and insightful information that ultimately influences your work.

Typically, the research question guides the stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting. Depending on the use of quantifiable or quantitative data, research questions are broadly categorized into quantitative or qualitative research questions. Both types of research questions can be used independently or together, considering the overall focus and objectives of your research.

What is a research question?

A research question is a clear, focused, concise, and arguable question on which your research and writing are centered. 1 It states various aspects of the study, including the population and variables to be studied and the problem the study addresses. These questions also set the boundaries of the study, ensuring cohesion.

Designing the research question is a dynamic process where the researcher can change or refine the research question as they review related literature and develop a framework for the study. Depending on the scale of your research, the study can include single or multiple research questions.

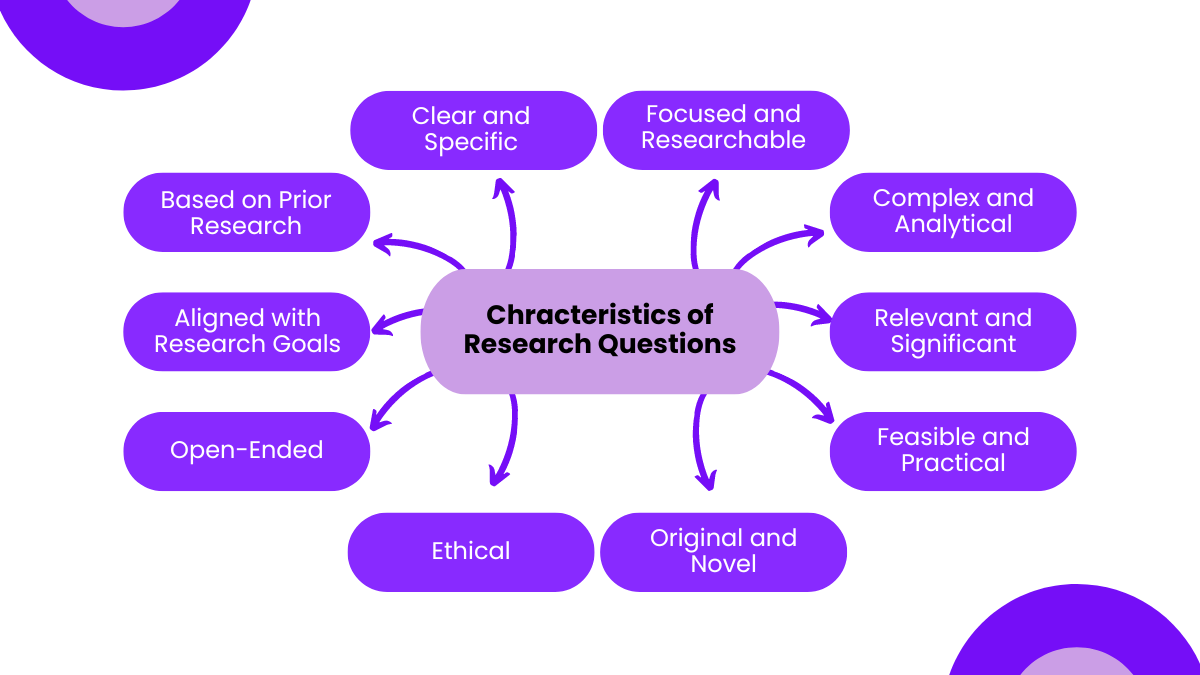

A good research question has the following features:

- It is relevant to the chosen field of study.

- The question posed is arguable and open for debate, requiring synthesizing and analysis of ideas.

- It is focused and concisely framed.

- A feasible solution is possible within the given practical constraint and timeframe.

A poorly formulated research question poses several risks. 1

- Researchers can adopt an erroneous design.

- It can create confusion and hinder the thought process, including developing a clear protocol.

- It can jeopardize publication efforts.

- It causes difficulty in determining the relevance of the study findings.

- It causes difficulty in whether the study fulfils the inclusion criteria for systematic review and meta-analysis. This creates challenges in determining whether additional studies or data collection is needed to answer the question.

- Readers may fail to understand the objective of the study. This reduces the likelihood of the study being cited by others.

Now that you know “What is a research question?”, let’s look at the different types of research questions.

Types of research questions

Depending on the type of research to be done, research questions can be classified broadly into quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies. Knowing the type of research helps determine the best type of research question that reflects the direction and epistemological underpinnings of your research.

The structure and wording of quantitative 2 and qualitative research 3 questions differ significantly. The quantitative study looks at causal relationships, whereas the qualitative study aims at exploring a phenomenon.

- Quantitative research questions:

- Seeks to investigate social, familial, or educational experiences or processes in a particular context and/or location.

- Answers ‘how,’ ‘what,’ or ‘why’ questions.

- Investigates connections, relations, or comparisons between independent and dependent variables.

Quantitative research questions can be further categorized into descriptive, comparative, and relationship, as explained in the Table below.

- Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional, and more flexible. It concerns broad areas of research or more specific areas of study to discover, explain, or explore a phenomenon. These are further classified as follows:

- Mixed-methods studies

Mixed-methods studies use both quantitative and qualitative research questions to answer your research question. Mixed methods provide a complete picture than standalone quantitative or qualitative research, as it integrates the benefits of both methods. Mixed methods research is often used in multidisciplinary settings and complex situational or societal research, especially in the behavioral, health, and social science fields.

What makes a good research question

A good research question should be clear and focused to guide your research. It should synthesize multiple sources to present your unique argument, and should ideally be something that you are interested in. But avoid questions that can be answered in a few factual statements. The following are the main attributes of a good research question.

- Specific: The research question should not be a fishing expedition performed in the hopes that some new information will be found that will benefit the researcher. The central research question should work with your research problem to keep your work focused. If using multiple questions, they should all tie back to the central aim.

- Measurable: The research question must be answerable using quantitative and/or qualitative data or from scholarly sources to develop your research question. If such data is impossible to access, it is better to rethink your question.

- Attainable: Ensure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific.

- You have the expertise

- You have the equipment and resources

- Realistic: Developing your research question should be based on initial reading about your topic. It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline.

- Based on some sort of rational physics

- Can be done in a reasonable time frame

- Timely: The research question should contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on.

- Novel

- Based on current technologies.

- Important to answer current problems or concerns.

- Lead to new directions.

- Important: Your question should have some aspect of originality. Incremental research is as important as exploring disruptive technologies. For example, you can focus on a specific location or explore a new angle.

- Meaningful whether the answer is “Yes” or “No.” Closed-ended, yes/no questions are too simple to work as good research questions. Such questions do not provide enough scope for robust investigation and discussion. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation before providing an answer.

Steps for developing a good research question

The importance of research questions cannot be understated. When drafting a research question, use the following frameworks to guide the components of your question to ease the process. 4

- Determine the requirements: Before constructing a good research question, set your research requirements. What is the purpose? Is it descriptive, comparative, or explorative research? Determining the research aim will help you choose the most appropriate topic and word your question appropriately.

- Select a broad research topic: Identify a broader subject area of interest that requires investigation. Techniques such as brainstorming or concept mapping can help identify relevant connections and themes within a broad research topic. For example, how to learn and help students learn.

- Perform preliminary investigation: Preliminary research is needed to obtain up-to-date and relevant knowledge on your topic. It also helps identify issues currently being discussed from which information gaps can be identified.

- Narrow your focus: Narrow the scope and focus of your research to a specific niche. This involves focusing on gaps in existing knowledge or recent literature or extending or complementing the findings of existing literature. Another approach involves constructing strong research questions that challenge your views or knowledge of the area of study (Example: Is learning consistent with the existing learning theory and research).

- Identify the research problem: Once the research question has been framed, one should evaluate it. This is to realize the importance of the research questions and if there is a need for more revising (Example: How do your beliefs on learning theory and research impact your instructional practices).

How to write a research question

Those struggling to understand how to write a research question, these simple steps can help you simplify the process of writing a research question.

Sample Research Questions

The following are some bad and good research question examples

- Example 1

- Example 2

References:

- Thabane, L., Thomas, T., Ye, C., & Paul, J. (2009). Posing the research question: not so simple. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie , 56 (1), 71-79.