Background Research

What is background research, tyes of background information.

- General Sources

- Subject Specific Sources

Background research (or pre-research) is the research that you do before you start writing your paper or working on your project. Sometimes background research happens before you've even chosen a topic. The purpose of background research is to make the research that goes into your paper or project easier and more successful.

Some reasons to do background research include:

- Determining an appropriate scope for your research: Successful research starts with a topic or question that is appropriate to the scope of the assignment. A topic that is too broad means too much relevant information to review and distill. If your topic is too narrow, there won't be enough information to do meaningful research.

- Understanding how your research fits in with the broader conversation surrounding the topic: What are the major points of view or areas of interest in discussions of your research topic and how does your research fit in with these? Answering this question can help you define the parts of your topic that you need to explore.

- Establishing the value of your research : What is the impact of your research and why does it matter? How might your research clarify or change our understanding of the topic?

- Identifying experts and other important perspectives: Are there scholars whose work you need to understand for your research to be complete? Are there points of view that you need to include or address?

Doing background research helps you choose a topic that you'll be happy with and develop a sense of what research you'll need to do in order to successfully complete your assignment. It will also help you plan your research and understand how much time you'll need to dedicate to understanding and exploring your topic.

Some types of information sources can be particularly helpful when you're doing background research. These are often primarily tertiary sources meaning that, rather than conducting original research they often summarize existing research on the topic.

Current Events Briefs Databases like CQ Researcher are focused on understanding controversial topics in current events. They provide information about the background of the issue as well as explanations of the positions of those on either side of a controversy.

Encyclopedias Encyclopedias are ideal sources for doing background research in order build your knowledge about a topic sufficiently to identify a topic and develop a research plan.

Dictionaries Dictionaries include both general dictionaries like the Oxford English Dictionary as well as more specialized dictionaries focused on a single area. Dictionary entries are usually shorter and less detailed than encyclopedia entries and generally do not include references. However, they can be helpful when your research introduces you to concepts with which you aren't familiar.

Textbooks Your textbook is a potential source of background information, providing an explanation of the topic that prepares you to focus and dig deeper. Textbooks give a general overview of lot of information.

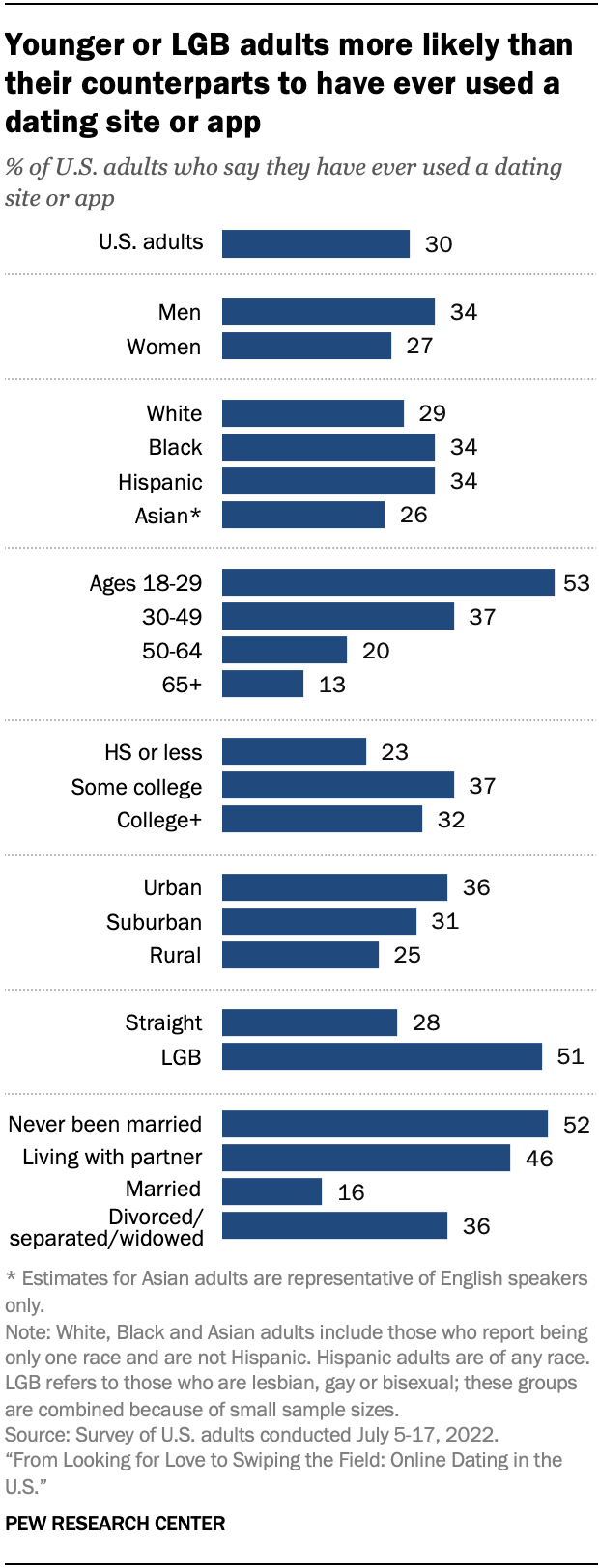

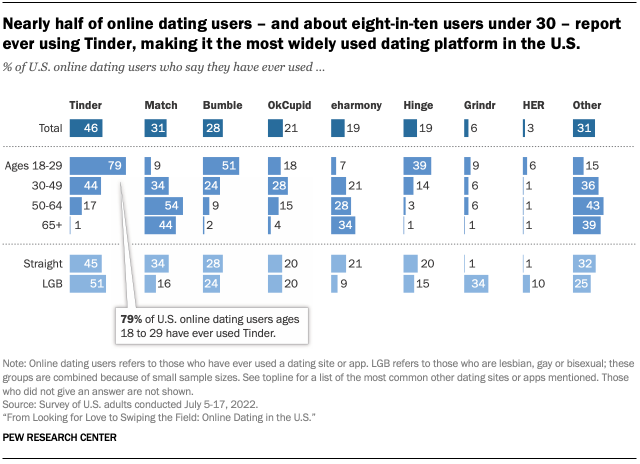

Statistics While you may find that it's difficult to make sense of statistics related to your topic while you're still exploring, statistics can be a powerful tool for establishing the context and importance of your research.

- Next: General Sources >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 1:15 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.odu.edu/background

- Privacy Policy

Home » Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Background of The Study

Definition:

Background of the study refers to the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being studied. It provides the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and the significance of the study.

The background of the study usually includes a discussion of the relevant literature, the gap in knowledge or understanding, and the research questions or hypotheses to be addressed. It also highlights the importance of the research topic and its potential contributions to the field. A well-written background of the study sets the stage for the research and helps the reader to appreciate the need for the study and its potential significance.

How to Write Background of The Study

Here are some steps to help you write the background of the study:

Identify the Research Problem

Start by identifying the research problem you are trying to address. This problem should be significant and relevant to your field of study.

Provide Context

Once you have identified the research problem, provide some context. This could include the historical, social, or political context of the problem.

Review Literature

Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature on the topic. This will help you understand what has been studied and what gaps exist in the current research.

Identify Research Gap

Based on your literature review, identify the gap in knowledge or understanding that your research aims to address. This gap will be the focus of your research question or hypothesis.

State Objectives

Clearly state the objectives of your research . These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Discuss Significance

Explain the significance of your research. This could include its potential impact on theory , practice, policy, or society.

Finally, summarize the key points of the background of the study. This will help the reader understand the research problem, its context, and its significance.

How to Write Background of The Study in Proposal

The background of the study is an essential part of any proposal as it sets the stage for the research project and provides the context and justification for why the research is needed. Here are the steps to write a compelling background of the study in your proposal:

- Identify the problem: Clearly state the research problem or gap in the current knowledge that you intend to address through your research.

- Provide context: Provide a brief overview of the research area and highlight its significance in the field.

- Review literature: Summarize the relevant literature related to the research problem and provide a critical evaluation of the current state of knowledge.

- Identify gaps : Identify the gaps or limitations in the existing literature and explain how your research will contribute to filling these gaps.

- Justify the study : Explain why your research is important and what practical or theoretical contributions it can make to the field.

- Highlight objectives: Clearly state the objectives of the study and how they relate to the research problem.

- Discuss methodology: Provide an overview of the methodology you will use to collect and analyze data, and explain why it is appropriate for the research problem.

- Conclude : Summarize the key points of the background of the study and explain how they support your research proposal.

How to Write Background of The Study In Thesis

The background of the study is a critical component of a thesis as it provides context for the research problem, rationale for conducting the study, and the significance of the research. Here are some steps to help you write a strong background of the study:

- Identify the research problem : Start by identifying the research problem that your thesis is addressing. What is the issue that you are trying to solve or explore? Be specific and concise in your problem statement.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the relevant literature on the topic. This should include scholarly articles, books, and other sources that are directly related to your research question.

- I dentify gaps in the literature: After reviewing the literature, identify any gaps in the existing research. What questions remain unanswered? What areas have not been explored? This will help you to establish the need for your research.

- Establish the significance of the research: Clearly state the significance of your research. Why is it important to address this research problem? What are the potential implications of your research? How will it contribute to the field?

- Provide an overview of the research design: Provide an overview of the research design and methodology that you will be using in your study. This should include a brief explanation of the research approach, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

- State the research objectives and research questions: Clearly state the research objectives and research questions that your study aims to answer. These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

- Summarize the chapter: Summarize the chapter by highlighting the key points and linking them back to the research problem, significance of the study, and research questions.

How to Write Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are the steps to write the background of the study in a research paper:

- Identify the research problem: Start by identifying the research problem that your study aims to address. This can be a particular issue, a gap in the literature, or a need for further investigation.

- Conduct a literature review: Conduct a thorough literature review to gather information on the topic, identify existing studies, and understand the current state of research. This will help you identify the gap in the literature that your study aims to fill.

- Explain the significance of the study: Explain why your study is important and why it is necessary. This can include the potential impact on the field, the importance to society, or the need to address a particular issue.

- Provide context: Provide context for the research problem by discussing the broader social, economic, or political context that the study is situated in. This can help the reader understand the relevance of the study and its potential implications.

- State the research questions and objectives: State the research questions and objectives that your study aims to address. This will help the reader understand the scope of the study and its purpose.

- Summarize the methodology : Briefly summarize the methodology you used to conduct the study, including the data collection and analysis methods. This can help the reader understand how the study was conducted and its reliability.

Examples of Background of The Study

Here are some examples of the background of the study:

Problem : The prevalence of obesity among children in the United States has reached alarming levels, with nearly one in five children classified as obese.

Significance : Obesity in childhood is associated with numerous negative health outcomes, including increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and certain cancers.

Gap in knowledge : Despite efforts to address the obesity epidemic, rates continue to rise. There is a need for effective interventions that target the unique needs of children and their families.

Problem : The use of antibiotics in agriculture has contributed to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which poses a significant threat to human health.

Significance : Antibiotic-resistant infections are responsible for thousands of deaths each year and are a major public health concern.

Gap in knowledge: While there is a growing body of research on the use of antibiotics in agriculture, there is still much to be learned about the mechanisms of resistance and the most effective strategies for reducing antibiotic use.

Edxample 3:

Problem : Many low-income communities lack access to healthy food options, leading to high rates of food insecurity and diet-related diseases.

Significance : Poor nutrition is a major contributor to chronic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Gap in knowledge : While there have been efforts to address food insecurity, there is a need for more research on the barriers to accessing healthy food in low-income communities and effective strategies for increasing access.

Examples of Background of The Study In Research

Here are some real-life examples of how the background of the study can be written in different fields of study:

Example 1 : “There has been a significant increase in the incidence of diabetes in recent years. This has led to an increased demand for effective diabetes management strategies. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of a new diabetes management program in improving patient outcomes.”

Example 2 : “The use of social media has become increasingly prevalent in modern society. Despite its popularity, little is known about the effects of social media use on mental health. This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health in young adults.”

Example 3: “Despite significant advancements in cancer treatment, the survival rate for patients with pancreatic cancer remains low. The purpose of this study is to identify potential biomarkers that can be used to improve early detection and treatment of pancreatic cancer.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Proposal

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in a proposal:

Example 1 : The prevalence of mental health issues among university students has been increasing over the past decade. This study aims to investigate the causes and impacts of mental health issues on academic performance and wellbeing.

Example 2 : Climate change is a global issue that has significant implications for agriculture in developing countries. This study aims to examine the adaptive capacity of smallholder farmers to climate change and identify effective strategies to enhance their resilience.

Example 3 : The use of social media in political campaigns has become increasingly common in recent years. This study aims to analyze the effectiveness of social media campaigns in mobilizing young voters and influencing their voting behavior.

Example 4 : Employee turnover is a major challenge for organizations, especially in the service sector. This study aims to identify the key factors that influence employee turnover in the hospitality industry and explore effective strategies for reducing turnover rates.

Examples of Background of The Study in Thesis

Here are some real-time examples of the background of the study in the thesis:

Example 1 : “Women’s participation in the workforce has increased significantly over the past few decades. However, women continue to be underrepresented in leadership positions, particularly in male-dominated industries such as technology. This study aims to examine the factors that contribute to the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles in the technology industry, with a focus on organizational culture and gender bias.”

Example 2 : “Mental health is a critical component of overall health and well-being. Despite increased awareness of the importance of mental health, there are still significant gaps in access to mental health services, particularly in low-income and rural communities. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a community-based mental health intervention in improving mental health outcomes in underserved populations.”

Example 3: “The use of technology in education has become increasingly widespread, with many schools adopting online learning platforms and digital resources. However, there is limited research on the impact of technology on student learning outcomes and engagement. This study aims to explore the relationship between technology use and academic achievement among middle school students, as well as the factors that mediate this relationship.”

Examples of Background of The Study in Research Paper

Here are some examples of how the background of the study can be written in various fields:

Example 1: The prevalence of obesity has been on the rise globally, with the World Health Organization reporting that approximately 650 million adults were obese in 2016. Obesity is a major risk factor for several chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. In recent years, several interventions have been proposed to address this issue, including lifestyle changes, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery. However, there is a lack of consensus on the most effective intervention for obesity management. This study aims to investigate the efficacy of different interventions for obesity management and identify the most effective one.

Example 2: Antibiotic resistance has become a major public health threat worldwide. Infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria are associated with longer hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and increased mortality. The inappropriate use of antibiotics is one of the main factors contributing to the development of antibiotic resistance. Despite numerous efforts to promote the rational use of antibiotics, studies have shown that many healthcare providers continue to prescribe antibiotics inappropriately. This study aims to explore the factors influencing healthcare providers’ prescribing behavior and identify strategies to improve antibiotic prescribing practices.

Example 3: Social media has become an integral part of modern communication, with millions of people worldwide using platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Social media has several advantages, including facilitating communication, connecting people, and disseminating information. However, social media use has also been associated with several negative outcomes, including cyberbullying, addiction, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on mental health and identify the factors that mediate this relationship.

Purpose of Background of The Study

The primary purpose of the background of the study is to help the reader understand the rationale for the research by presenting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem.

More specifically, the background of the study aims to:

- Provide a clear understanding of the research problem and its context.

- Identify the gap in knowledge that the study intends to fill.

- Establish the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field.

- Highlight the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

- Provide a rationale for the research questions or hypotheses and the research design.

- Identify the limitations and scope of the study.

When to Write Background of The Study

The background of the study should be written early on in the research process, ideally before the research design is finalized and data collection begins. This allows the researcher to clearly articulate the rationale for the study and establish a strong foundation for the research.

The background of the study typically comes after the introduction but before the literature review section. It should provide an overview of the research problem and its context, and also introduce the key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem.

Writing the background of the study early on in the research process also helps to identify potential gaps in knowledge and areas for further investigation, which can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design. By establishing the significance of the research problem and its potential contribution to the field, the background of the study can also help to justify the research and secure funding or support from stakeholders.

Advantage of Background of The Study

The background of the study has several advantages, including:

- Provides context: The background of the study provides context for the research problem by highlighting the historical, theoretical, and empirical background of the problem. This allows the reader to understand the research problem in its broader context and appreciate its significance.

- Identifies gaps in knowledge: By reviewing the existing literature related to the research problem, the background of the study can identify gaps in knowledge that the study intends to fill. This helps to establish the novelty and originality of the research and its potential contribution to the field.

- Justifies the research : The background of the study helps to justify the research by demonstrating its significance and potential impact. This can be useful in securing funding or support for the research.

- Guides the research design: The background of the study can guide the development of the research questions or hypotheses and the research design by identifying key concepts, theories, and research findings related to the problem. This ensures that the research is grounded in existing knowledge and is designed to address the research problem effectively.

- Establishes credibility: By demonstrating the researcher’s knowledge of the field and the research problem, the background of the study can establish the researcher’s credibility and expertise, which can enhance the trustworthiness and validity of the research.

Disadvantages of Background of The Study

Some Disadvantages of Background of The Study are as follows:

- Time-consuming : Writing a comprehensive background of the study can be time-consuming, especially if the research problem is complex and multifaceted. This can delay the research process and impact the timeline for completing the study.

- Repetitive: The background of the study can sometimes be repetitive, as it often involves summarizing existing research and theories related to the research problem. This can be tedious for the reader and may make the section less engaging.

- Limitations of existing research: The background of the study can reveal the limitations of existing research related to the problem. This can create challenges for the researcher in developing research questions or hypotheses that address the gaps in knowledge identified in the background of the study.

- Bias : The researcher’s biases and perspectives can influence the content and tone of the background of the study. This can impact the reader’s perception of the research problem and may influence the validity of the research.

- Accessibility: Accessing and reviewing the literature related to the research problem can be challenging, especially if the researcher does not have access to a comprehensive database or if the literature is not available in the researcher’s language. This can limit the depth and scope of the background of the study.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Verification – Process, Types and Examples

Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing...

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Assignment – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Appendix in Research Paper – Examples and...

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Background Information

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Background information identifies and describes the history and nature of a well-defined research problem with reference to contextualizing existing literature. The background information should indicate the root of the problem being studied, appropriate context of the problem in relation to theory, research, and/or practice , its scope, and the extent to which previous studies have successfully investigated the problem, noting, in particular, where gaps exist that your study attempts to address. Background information does not replace the literature review section of a research paper; it is intended to place the research problem within a specific context and an established plan for its solution.

Fitterling, Lori. Researching and Writing an Effective Background Section of a Research Paper. Kansas City University of Medicine & Biosciences; Creating a Research Paper: How to Write the Background to a Study. DurousseauElectricalInstitute.com; Background Information: Definition of Background Information. Literary Devices Definition and Examples of Literary Terms.

Importance of Having Enough Background Information

Background information expands upon the key points stated in the beginning of your introduction but is not intended to be the main focus of the paper. It generally supports the question, what is the most important information the reader needs to understand before continuing to read the paper? Sufficient background information helps the reader determine if you have a basic understanding of the research problem being investigated and promotes confidence in the overall quality of your analysis and findings. This information provides the reader with the essential context needed to conceptualize the research problem and its significance before moving on to a more thorough analysis of prior research.

Forms of contextualization included in background information can include describing one or more of the following:

- Cultural -- placed within the learned behavior of a specific group or groups of people.

- Economic -- of or relating to systems of production and management of material wealth and/or business activities.

- Gender -- located within the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with being self-identified as male, female, or other form of gender expression.

- Historical -- the time in which something takes place or was created and how the condition of time influences how you interpret it.

- Interdisciplinary -- explanation of theories, concepts, ideas, or methodologies borrowed from other disciplines applied to the research problem rooted in a discipline other than the discipline where your paper resides.

- Philosophical -- clarification of the essential nature of being or of phenomena as it relates to the research problem.

- Physical/Spatial -- reflects the meaning of space around something and how that influences how it is understood.

- Political -- concerns the environment in which something is produced indicating it's public purpose or agenda.

- Social -- the environment of people that surrounds something's creation or intended audience, reflecting how the people associated with something use and interpret it.

- Temporal -- reflects issues or events of, relating to, or limited by time. Concerns past, present, or future contextualization and not just a historical past.

Background information can also include summaries of important research studies . This can be a particularly important element of providing background information if an innovative or groundbreaking study about the research problem laid a foundation for further research or there was a key study that is essential to understanding your arguments. The priority is to summarize for the reader what is known about the research problem before you conduct the analysis of prior research. This is accomplished with a general summary of the foundational research literature [with citations] that document findings that inform your study's overall aims and objectives.

NOTE: Research studies cited as part of the background information of your introduction should not include very specific, lengthy explanations. This should be discussed in greater detail in your literature review section. If you find a study requiring lengthy explanation, consider moving it to the literature review section.

ANOTHER NOTE: In some cases, your paper's introduction only needs to introduce the research problem, explain its significance, and then describe a road map for how you are going to address the problem; the background information basically forms the introduction part of your literature review. That said, while providing background information is not required, including it in the introduction is a way to highlight important contextual information that could otherwise be hidden or overlooked by the reader if placed in the literature review section.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: In some research studies, the background information is described in a separate section after the introduction and before the literature review. This is most often done if the topic is especially complex or requires a lot of context in order to fully grasp the significance of the research problem. Most college-level research papers do not require this unless required by your professor. However, if you find yourself needing to write more than a couple of pages [double-spaced lines] to provide the background information, it can be written as a separate section to ensure the introduction is not too lengthy.

Background of the Problem Section: What do you Need to Consider? Anonymous. Harvard University; Hopkins, Will G. How to Write a Research Paper. SPORTSCIENCE, Perspectives/Research Resources. Department of Physiology and School of Physical Education, University of Otago, 1999; Green, L. H. How to Write the Background/Introduction Section. Physics 499 Powerpoint slides. University of Illinois; Pyrczak, Fred. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 8th edition. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2014; Stevens, Kathleen C. “Can We Improve Reading by Teaching Background Information?.” Journal of Reading 25 (January 1982): 326-329; Woodall, W. Gill. Writing the Background and Significance Section. Senior Research Scientist and Professor of Communication. Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions. University of New Mexico.

Structure and Writing Style

Providing background information in the introduction of a research paper serves as a bridge that links the reader to the research problem . Precisely how long and in-depth this bridge should be is largely dependent upon how much information you think the reader will need to know in order to fully understand the problem being discussed and to appreciate why the issues you are investigating are important.

From another perspective, the length and detail of background information also depends on the degree to which you need to demonstrate to your professor how much you understand the research problem. Keep this in mind because providing pertinent background information can be an effective way to demonstrate that you have a clear grasp of key issues, debates, and concepts related to your overall study.

The structure and writing style of your background information can vary depending upon the complexity of your research and/or the nature of the assignment. However, in most cases it should be limited to only one to two paragraphs in your introduction.

Given this, here are some questions to consider while writing this part of your introduction :

- Are there concepts, terms, theories, or ideas that may be unfamiliar to the reader and, thus, require additional explanation?

- Are there historical elements that need to be explored in order to provide needed context, to highlight specific people, issues, or events, or to lay a foundation for understanding the emergence of a current issue or event?

- Are there theories, concepts, or ideas borrowed from other disciplines or academic traditions that may be unfamiliar to the reader and therefore require further explanation?

- Is there a key study or small set of studies that set the stage for understanding the topic and frames why it is important to conduct further research on the topic?

- Y our study uses a method of analysis never applied before;

- Your study investigates a very esoteric or complex research problem;

- Your study introduces new or unique variables that need to be taken into account ; or,

- Your study relies upon analyzing unique texts or documents, such as, archival materials or primary documents like diaries or personal letters that do not represent the established body of source literature on the topic?

Almost all introductions to a research problem require some contextualizing, but the scope and breadth of background information varies depending on your assumption about the reader's level of prior knowledge . However, despite this assessment, background information should be brief and succinct and sets the stage for the elaboration of critical points or in-depth discussion of key issues in the literature review section of your paper.

Writing Tip

Background Information vs. the Literature Review

Incorporating background information into the introduction is intended to provide the reader with critical information about the topic being studied, such as, highlighting and expanding upon foundational studies conducted in the past, describing important historical events that inform why and in what ways the research problem exists, defining key components of your study [concepts, people, places, phenomena] and/or placing the research problem within a particular context. Although introductory background information can often blend into the literature review portion of the paper, essential background information should not be considered a substitute for a comprehensive review and synthesis of relevant research literature.

Hart, Cris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998; Pyrczak, Fred. Writing Empirical Research Reports: A Basic Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences . 8th edition. Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Publishing, 2014.

- << Previous: The C.A.R.S. Model

- Next: The Research Problem/Question >>

- Last Updated: May 30, 2024 9:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Research Strategies: Background research

- Selecting a topic

Background research

- Initial Searching

- Form a research question

- Information Cycle

- Primary | Secondary

- Peer Review

- Finding Books

- Search for articles

- Using Google Scholar

- Revising Sources

- More sources

- Evaluation Toolkit

- Assess Information

- Integrating Sources into your Paper

- Reading Citation

- Citation Management

- Plagiarism Tutorial

- Reference Sources

- Annotated Bibliography

What's Happening When You Do Background Research?

When you do background research, you're exploring your general area of interest so that you can form a more focused topic. You will be making an entry into an ongoing conversation, and you have the opportunity to ask new questions and create new knowledge.

Why is this important?

Have you ever done a project that just never seemed to come together?

"I had a general idea but not a specific focus. As I was writing, I didn't know what my focus was. When I was finished, I didn't know what my focus was. My teacher says she doesn't know what my focus was. I don't think I ever acquired a focus. It was an impossible paper to write. I would just sit there and say, "I'm stuck." If I learned anything from that paper it is, you have to have a focus. You have to have something to center on. You can't just have a topic. You should have an idea when you start. I had a topic but I didn't know what I wanted to do with it. I figured that when I did my research it would focus in. But I didn't let it. I kept saying, 'this is interesting and this is interesting and I'll just smush it all together.' It didn't work out." -(Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century)

Can you relate?

Doing background research to explore your initial topic can help you to find create a focused research question . Another benefit to background searching - it's very hard to write about something if you don't know anything about it! At this point, collecting ideas to help you construct your focused topic will be very helpful. Not every idea you encounter will find its way into your final project, so don't worry about collecting very, very detailed information just yet. Wait until your project has found a focus.

While you're doing you're background research, don't be surprised if your topic changes in unexpected ways - you're discovering more about your topic, and you're making choices based on on the new information you find. If your topic changes, that's OK!

A tool to help you throughout your project: the research log! Logging your research, and making a general record of the sources you find will be very useful for you at this point.

Research Log

What Interests You?

Identifying what interests you in the context of your assignment can help you get started on your research project.

Some questions to consider:

Why is your project interesting/important to you? To your community? To the world?

What about your project sparks your curiosity and creativity?

Some ideas from the Reference Librarians at Gustavus Adolphus

- Make a list of possible issues to research. Use class discussions, texts, personal interests, conversations with friends, and discussions with your teacher for ideas. Start writing them down - you'd be surprised how much faster they come once you start writing.

- Map out the topic by finding out what others have had to say about it. This is not the time for in-depth reading, but rather for a quick scan. Many students start with a Google search, but you can also browse the shelves where books on the topic are kept and see what controversies or issues have been receiving attention. Search a database for articles on your topic area and sort out the various approaches writers have taken. Look for overviews and surveys of the topic that put the various schools of thought or approaches in context. You may start out knowing virtually nothing about your topic, but after scanning what's out there you should have several ideas worth following up.

- Invent questions. Do two things you come across seem to offer interesting contrasts? Does one thing seem intriguingly connected to something else? Is there something about the topic that surprises you? Do you encounter anything that makes you wonder why? Do you run into something that makes you think, "no way! That can't be right." Chances are you've just uncovered a good research focus.

- Draft a proposal for research. Sometimes a teacher will ask you for a formal written proposal. Even if it isn’t required, it can be a useful exercise. Write down what you want to do, how you plan to do it, and why it's important. You may well change your topic entirely by the time its finished, but writing down where you plan to take your research at this stage can help you clarify your thoughts and plan your next steps.

-Source: The Reference Librarians at Gustavus Adolphus College

What am I looking for?

It can be very helpful to write out your thoughts as you work through the answers to these questions.

Think about what you need to know:

- What do you already know about your topic?

- What don't you know about your topic? What do you feel like you might need to know?

- What are the fundamental facts and background on your topic? What do you need to know to write knowledgeably about your topic?

- What are the different viewpoints on your topic? You should expect to encounter diverse views on a topic.

And of course...

- What is your assignment asking of you?

When you are doing your research, you are not looking for one perfect source with one right answer. You're collecting and thinking critically about ideas to form a focus for your own research.

If you're having trouble answering these questions, you might find the six journalist's questions helpful in focusing your thinking:

Don't feel like you need to get bogged down in the minutiae of every source at this point!

At this point in your research, you are browsing for ideas and information to help you fill in the gaps. You're looking to develop a more focused topic. When you focus your topic you'll be able to really engage with the sources that will help you with your sources.

Not quite sure how to get started? The KWHL Tool will help you visualize your thinking, and start organizing the information you find. It will help you sort out

- What you already know

- What you don’t yet know about your topic

- Where you’re looking ( how will you find it)

- What you’ve learned

All of which will help you focus your project! (and maybe save a little time & stress, too!)

Use this chart to help organize your project

PDF version of the KWHL Chart to help organize your project

Take Notes while You're Searching!

As you're doing your research, take some brief notes about the sources you've found. Noting interesting ideas and items will help you remember what you've read as you put your ideas together to form a research question. It will also help you to make note of parts of your sources that you want to quote later (and find it easily while you're putting your research project together!)

This tool will help you keep track of good ideas and questions as you do your preliminary research.

Example of Brainstorming 1: Global Warming

Here's an example of a mindmap. The student used colors to organize her ideas: red is the idea she started with, green are broader concepts, black are subtopics. She put a red star on the topic she decided to focus on.

Example of Brainstorming

This shows a more formal example of brainstorming to go from a broad topic (global warming) to more narrower topics (like environment and political), to even more narrow topics (like rising sea levels and roles of government).

| Topic | Narrower Topic | Even Narrower |

|---|---|---|

| Global Warming | Environment | - rising sea levels - destruction of rain forests - air pollution |

| Political | - Kyoto Protocol - roles of government | |

| Human Element | - impact on world health - reducing use of fossil fuel | |

| Economic | - agriculture - role of corporations | |

| Geographical | - developing countries - Antarctic region |

Apps for Brainstorming

- << Previous: Selecting a topic

- Next: Initial Searching >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2024 1:47 PM

- URL: https://libguides.salemstate.edu/rsearchstrategies

Get Your Research Started: Background Research

- Your Research Question

- Find Background Info

- Find Sources

- Find Primary Sources This link opens in a new window

- Read and Evaluate

- Write and Cite

Why background research helps

Getting background and some basic facts about your topic is a good way to start. This helps not only get some initial information but helps you formulate the boundaries of your research and key terms for your thesis statement. It can be a helpful guide to begin to narrow down your topic into a coherent and specific area.

Credo Reference

Search

Helpful Business Guide from Credo

Encyclopedia notes

Generally you don't cite encyclopedias in research papers, but they can:

- provide great background information

- lead you to books and articles that you can cite

- help you narrow and focus your topic

Don't be afraid of the actual print, non-web, reference encyclopedias!

Oxford Reference

- Last Updated: Jan 23, 2024 1:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.library.cofc.edu/libraryresearch

College Quick Links

Research Process

- What is Research?

- Choose a Topic

Background Research

- Refine Topic

- Create Research Question

- Develop Search Strategy

- Evaluate Results & Sources

- Adjust (and Repeat) Search

- Write, Review, Cite, Edit

- Using AI like Chat GPT for Research

- What is Background Research?

- Generating Keyword Lists

- Developing Keywords - Video

- Where to Look

- Helpful Tools

- Literature Review

Background Research is the KEY to giving you a better understanding of your topic.

This is the initial stage of research and is VITAL to gain fuller understanding of the different directions your initial idea could take you in.

It will help you discover what is generally known about your topic and help you refine the ideas you have to help make your perspective more unique.

Why is this Important?

The key words will help find relevant information faster. Key words can be searched using indexes in books or online search engines and databases.

Once you have your general topic:

Write a sentence or two about your topic

Underline the key words in your sentence(s)

Create a list for these key words

Add more by writing down synonyms

Example: Video Games

Sentence: I want to investigate the idea that video games makes children and young people more violent

Keywords, Synonyms & Related Terms :

Further Example:

Research Question: What impact does public healthcare have on low income households in the United States compared to those in Canada ?

| universal, widespread | |

| health protection, preventive medicine, primary care | |

"Developing Keywords (Univ. of Houston Libraries)." YouTube , uploaded by VUstew, U of Houston, 28 June 2016, youtu.be/BdPFdFvGRvI. Accessed 29 Mar. 2023.

Encyclopedia - Skim encyclopedia articles on the key words.

Google - Use key words to search online for general information.

Books - Skim over the introduction and table of contents of a book pertaining to the topic.

As you get an overview of the general topic, start to ask questions that you want to get answers for. This will help to further narrow your topic and help with the research process.

- Carrot2 Carrot² is an open source search results clustering engine. It can automatically cluster small collections of documents, e.g. search results or document abstracts, into thematic categories.

Screenshot of Search Results:

Definition:

A literature review is a summative evaluation of what has already been written (or said) about a given topic

Purpose:

To better understand the topic, make links between your ideas/methods and those of others, consider whether your ideas challenge or support existing consensus, situate your views within context of existing viewpoints, track any major trends/patterns in terms of interpretation, allow you to identify value & limitations of source material

Why:

To successfully tackle your EE your need a link to pre-existing literature, so a literature review forms a foundation & supports the development of your own voice

How:

You are trying to find out the following

Interpretations:

Identify what interpretations exist and if there are any patterns emerging among them

Identify alternatives justifications or judgements

Methodology:

Identify what approaches are best suited or recommended for your chosen topic/area of study

Identify alternative methodological approaches to your topic/area of study

Results:

Determine which approach or sources are more reliable

Identify any biases that may have affected the end results

Use the following questions to help conduct your literature review:

Arguments What are the main arguments or interpretations to emerge from the literature?

Themes What are the main themes or areas covered by the literature reviewed?

Sections What sections (or headings) can I sub-divide my topic into?

Problems What are the key problems relating to my topic that emerge out of the review that I need to address?

Consensus What consensus of opinion or comparisons between sources exists?

Contrast What contrasting opinions exist within the literature reviewed?

Method How can the chosen theory or model be applied to your investigation?

Limitations What limitations can be identified in the method chosen or sources selected?

Adapted from: Lekanides , Kosta. Oxford IB Diploma Programme : Extended Essay Course Companion . Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 58-60.

- << Previous: Choose a Topic

- Next: Refine Topic >>

- Last Updated: May 6, 2023 8:04 PM

- URL: https://uwcchina.libguides.com/research

Literature - Research Guide

- Library Policies and FAQs

- Background Research

- Find Articles

- Find Books/eBooks

- Cite Sources This link opens in a new window

- Internet Resources

- Ask a Librarian This link opens in a new window

Reference Databases

Reference materials.

Starting Your Research

Academic research is a process, not a result. Successful research a little planning and patience as you adapt to different research topics in different areas of study. Generally, the process outlined below is a good one to follow for most unfamiliar with academic research. 1). Pick a Topic

Sometimes you get to choose your topic, sometimes it's a general topic is chosen for you and you need to select a sub-topic within it. Regardless, if you're able try to focus on something that interests you. This could be because you've had some experience with it, or something new you want to learn more about. 2). Ask Questions

Questions are a useful way to narrow down from a general topic/sub-topic to a specific area of research. If your topic is a broad category (ex. Healthcare), try using who , what , where , when , why , and how as prompts to determine what aspects of your topic you'd like to explore.

3). Find Keywords

After you've narrowed your topic, conduct some background research on the narrowed area. Usually background research is done in tertiary or reference sources and databases. See the Reference Database menu on this page for several background research options. 4). Determine Where To Search Once some initial keywords have been determined you will need to use them somewhere to search. The library has both specific databases to search in, as well as our Discovery service that unifies many databases and book catalogs in one place. Discovery is better for a general search, but if you already know your topic area specific databases may help as well. 5). Build and Adjust Your Search Most successful searches aren't the first ones you try. As you go through your search process pay attention to the keywords and alternative synonyms of your current keywords that can be added to your search. Ex. Instead of just using the keyword "teenager", use "adolescent" as well.

6). Cite Your Sources Academic scholarship is a conversation. Depending on the discipline this can stretch back decades or centuries between various academics, scholars, researchers, and primary sources. Citing where you obtained the information in your research is both a way of carrying that conversation forward, as well as

Types of Sources

Primary, Secondary, Tertiary Sources Primary - Sources that are typically information or knowledge that come from a direct observation or personal experience. Because different disciplines rely on different sources and kinds of information what counts as a primary source will also differ by discipline.

Secondary - Sources that are usually commentary (scholarly or otherwise) on primary source information. Like primary sources, what can count as a secondary source may differ by discipline. Generally though, if the author does not have first hand knowledge of their topic it is probably a secondary source. Examples include biographies, literature reviews,

Tertiary - Sources that reference general or common information. Tertiary sources are wonderful tools for your initial background research on a topic. Some examples include encyclopedias, atlases, and fact books.

Grey Literature - Commonly refers to any information not formally published in a traditional academic or commercial publishing model. Grey literature has typically not gone through a peer reviewed process but, depending on the source, may still be useful for background research. Examples include government documents, white papers, and evaluations, Peer Reviewed vs. Scholarly

Peer reviewed sources are typically articles or reports published in academic journals which undergo a review process by academics whose background is similar to the journal's (and author's) expertise. Essentially this is the quality check on the work's methodology, bibliography, and technical details. To find out if an article is peer reviewed or not, check what journal it was published in via a database or online search and see if the journal is listed as a peer reviewed source.

Scholarly sources are pieces of information written by one or more authors who are knowledgeable in the subject area they are writing about, but the information has not been published through a peer-reviewed process. Examples include an online blog, a newspaper opinion piece, a dissertation, or student academic research.

In summary, peer reviewed sources are usually scholarly, but scholarly sources are not always peer reviewed.

- << Previous: Library Policies and FAQs

- Next: Find Articles >>

- Last Updated: Oct 17, 2022 10:11 AM

- URL: https://jewell.libguides.com/literature-research

- Spartanburg Community College Library

- SCC Research Guides

- Choosing a Research Topic

- 2. Background Research

Background Research

Chances are the topic you chose for your research assignment isn't a topic that you know a lot about. That is okay and what makes research exciting! Before you dive into doing your research, especially if you are looking for academic sources in some of the library databases, you are going to want to do some background research on your topic.

Background research helps you learn more about a topic and gets you comfortable with key terms and ideas in your topic. Oftentimes, you will find that if you jump right into the academic sources, the academic sources will make the assumption that you already have some background knowledge about a topic, making the academic sources difficult to understand.

When doing background research, you want to answer six basic questions (5Ws + How) that will form your common knowledge about a subject.

Sticking with our example about the costs of college tuition:

- Who: "Who is impacted by the costs of college tuition?"

- What: "What is college tuition?"

- Where: "Where is college tuition used?"

- When: "When was did college tuition get so expensive?"

- How: "How does the cost of college tuition influence the college?"

- Why: "Why is college tuition so expensive?"

What sources are best for background research?

Reference sources are best for background research. Examples of reference sources include encyclopedias and dictionaries. Reference sources give an overview of an entire topic. They are usually written in a way that is understandable for someone without background knowledge on a topic.

The Library has several databases that are great places to search for background research. Keep in mind that depending on your research topic, some of these databases may be better to use than others. If you have any questions about which database is right for you, please Ask a Librarian !

- << Previous: 1. Concept Mapping

- Next: 3. Narrow Your Topic / Thesis Statements >>

- What Makes a Good Research Topic?

- 1. Concept Mapping

- 3. Narrow Your Topic / Thesis Statements

Questions? Ask a Librarian

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 9:31 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sccsc.edu/chooseatopic

Giles Campus | 864.592.4764 | Toll Free 866.542.2779 | Contact Us

Copyright © 2024 Spartanburg Community College. All rights reserved.

Info for Library Staff | Guide Search

Return to SCC Website

- Develop a Topic

- Find Sources

- Search Effectively

- Evaluate Sources

Need an Idea?

A great idea can come from many places. Here are some suggested places to start:

- Class discussions

- Assigned readings

- Topics in the news

- Browse journals in the field

- Personal interests

Develop Your Topic

- Explore Your Topic

- Refine Your Topic

Before you develop your research topic or question, you'll need to do some background research first.

Some good places to find background information:

- Your textbook or class readings

- Encyclopedias and reference books

- Credible websites

- Library databases

Try the library databases below to explore your topic. When you're ready, move on to refining your topic.

Find Background Information:

- GALE EBOOKS This link opens in a new window Gale Virtual Reference Library's powerful delivery platform puts your reference content into circulation. Researchers will have the power to Search and share results, Create mark lists, Track research through search history, Share articles using InfoTrac InfoMarks and more.

- GALE IN CONTEXT, Opposing Viewpoints This link opens in a new window A full-text resource covering today's hottest social issues, from Terrorism to Endangered Species, Stem Cell Research to Gun Control. Drawing on the series published by Greenhaven Press and other Gale imprints, Opposing Viewpoints Resource Center brings together information that's needed to understand an issue: pro & con viewpoint articles, reference articles that provide context, full-text magazines, academic journals, and newspapers, primary source documents, organizational statistics, & more.

Now that you've done some background research, it's time to narrow your topic. Remember: the shorter your final paper, the narrower your topic needs to be. Here are some suggestions for narrowing and defining your topic:

- Is there a specific subset of the topic you can focus on?

- Is there a cause and effect relationship you can explore?

- Is there an unanswered question on the subject?

- Can you focus on a specific time period or group of people?

Describe and develop your topic in some detail. Try filling in the blanks in the following sentence, as much as you can:

I want to research ____ (what/who) ____

and ____ (what/who) ____

in ____ (where) ____

during ____ (when) ____

because ____ (why) ____.

- << Previous: Welcome

- Next: Find Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 7, 2024 3:50 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uni.edu/nursing

- UNC Libraries

- Subject Research

- Research Methods for History

- Getting Started with Library Research

Research Methods for History: Getting Started with Library Research

Starting your search, searching library resources, finding background information.

- Library Research Skills / Concepts

- Reference Resources

- Articles and Books

- Digital Collections (Primary Sources)

- Archival Collections at UNC

- Database Guide

- Using Zotero

Using some of the keywords you have come up with, try searching the library’s website for suitable resources.

You can search Articles + AND the library’s catalog through our website here: https://library.unc.edu/

You can find links to individual databases that may be helpful on the E-Research by Discipline page of our website

Questions to consider as you search:

- What material are you finding?

- Did you need to refine keywords?

- Did you adjust any facets/toggles to refine your search results?

- Can you click through and explore an item?

- Can you download the item or find a stable link to it?

- Can you search within the item?

- Does it lead to other items you may find useful?

If you find anything interesting or relevant,make a note and we will share with the group.

Questions to consider:

- What made this item worth paying attention to?

- How is it relevant to your research topic?

At the beginning of the research process, you may need to find foundational readings to give an overview of your topic. Your readings from class will provide much of this foundational knowledge, but library resources can help supplement that.

These resources combine features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia. You can use them to identify key readings on and theoretical approaches to a variety of topics. Searching the library's online catalog and browsing by subject can similarly give you an idea of what types of materials are out there. The aim here is not to read every item, but to browse and get a sense of the conversation surrounding your topic. If a particular document seems overwhelming, you can always use Ctrl+F (or Command+F on a Mac) to "Find" keywords on a page.

Credo Reference

CQ Researcher

- Oxford Bibliographies Online Provides sophisticated online recommendations to the core scholarship on a subject as determined by experts in the field. Each module constitutes a convenient and comprehensive introduction to the essential body of literature that has shaped research on a topic. At the click of a mouse, you therefore have 24/7 access to expert recommendations that have been rigorously peer-reviewed and vetted to ensure scholarly accuracy and objectivity. Each OBO subject database allows you to identify the core authors, works, ideas, and debates that have shaped the scholarly conversation so you can find the key literature. All the bibliographic essays have been peer-reviewed, and the specific entries are linked to full-text content available through the web or the UNC Library. The "My OBO" feature also allows you to create a personalized list of citations. more... less... Access: Off Campus Access is available for: UNC-Chapel Hill student, faculty, and staff; UNC Hospitals employees; UNC-Chapel Hill affiliated AHEC users

Your Research Style

There are a lot of resources listed here and even more within the library's webpages. Don't get overwhelmed! You do not need to search them all. The resources in this guide are here to help you find a starting place for a wide range of topics. They may or may not be a perfect fit for your unique research needs. Try searching in a few new spots for each research project you do, stretch out of your comfort zone a little at a time, and always ask for help from a librarian if you have questions.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Library Research Skills / Concepts >>

- Last Updated: Jun 7, 2024 2:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/HistoryGrad

Research Lab Specialist Assoc

Why work at michigan.

Being part of something greater, of serving a larger mission of discovery and care — that's the heart of what drives people to work at Michigan. In some way, great or small, every person here helps to advance this world-class institution. It's adding a purpose to your profession. Work at Michigan and become a victor for the greater good.

Responsibilities*

- Carry out molecular biology laboratory experiments related to CRISPR/cas9 and cell line cultures. This may include but is not limmited to culturing cells, isolating DNA and proteins from them, RTPCR, western analysis, high throughput high content microscopy and analysis, whole genome crispr screeing and FACS analysis, cell assay development.

- Carry out human genetic analyses including guide enrichment analyses, genome wide assocaition analysis, transcription genome wide associaition analysis, gene expression analyses, gene annotation, and integrative omic analyses.

- Present at group meetings and at local and national meetings, write up papers and work, help write grants

- Support others in the lab with computational or molecular work needed.

Required Qualifications*

- Bachelor's degree

- 1-3 years of experience in a related field

Desired Qualifications*

- Master's degree in biostatistics, bioinformatics, and a molecular based discipline preferred.

Background Screening

Michigan Medicine conducts background screening and pre-employment drug testing on job candidates upon acceptance of a contingent job offer and may use a third party administrator to conduct background screenings. Background screenings are performed in compliance with the Fair Credit Report Act. Pre-employment drug testing applies to all selected candidates, including new or additional faculty and staff appointments, as well as transfers from other U-M campuses.

Application Deadline

Job openings are posted for a minimum of seven calendar days. The review and selection process may begin as early as the eighth day after posting. This opening may be removed from posting boards and filled anytime after the minimum posting period has ended.

U-M EEO/AA Statement

The University of Michigan is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer.

What Is Background in a Research Paper?

So you have carefully written your research paper and probably ran it through your colleagues ten to fifteen times. While there are many elements to a good research article, one of the most important elements for your readers is the background of your study.

What is Background of the Study in Research

The background of your study will provide context to the information discussed throughout the research paper . Background information may include both important and relevant studies. This is particularly important if a study either supports or refutes your thesis.

Why is Background of the Study Necessary in Research?

The background of the study discusses your problem statement, rationale, and research questions. It links introduction to your research topic and ensures a logical flow of ideas. Thus, it helps readers understand your reasons for conducting the study.

Providing Background Information

The reader should be able to understand your topic and its importance. The length and detail of your background also depend on the degree to which you need to demonstrate your understanding of the topic. Paying close attention to the following questions will help you in writing background information:

- Are there any theories, concepts, terms, and ideas that may be unfamiliar to the target audience and will require you to provide any additional explanation?

- Any historical data that need to be shared in order to provide context on why the current issue emerged?

- Are there any concepts that may have been borrowed from other disciplines that may be unfamiliar to the reader and need an explanation?

Related: Ready with the background and searching for more information on journal ranking? Check this infographic on the SCImago Journal Rank today!

Is the research study unique for which additional explanation is needed? For instance, you may have used a completely new method

How to Write a Background of the Study

The structure of a background study in a research paper generally follows a logical sequence to provide context, justification, and an understanding of the research problem. It includes an introduction, general background, literature review , rationale , objectives, scope and limitations , significance of the study and the research hypothesis . Following the structure can provide a comprehensive and well-organized background for your research.

Here are the steps to effectively write a background of the study.

1. Identify Your Audience:

Determine the level of expertise of your target audience. Tailor the depth and complexity of your background information accordingly.

2. Understand the Research Problem:

Define the research problem or question your study aims to address. Identify the significance of the problem within the broader context of the field.

3. Review Existing Literature:

Conduct a thorough literature review to understand what is already known in the area. Summarize key findings, theories, and concepts relevant to your research.

4. Include Historical Data:

Integrate historical data if relevant to the research, as current issues often trace back to historical events.

5. Identify Controversies and Gaps:

Note any controversies or debates within the existing literature. Identify gaps , limitations, or unanswered questions that your research can address.

6. Select Key Components:

Choose the most critical elements to include in the background based on their relevance to your research problem. Prioritize information that helps build a strong foundation for your study.

7. Craft a Logical Flow:

Organize the background information in a logical sequence. Start with general context, move to specific theories and concepts, and then focus on the specific problem.

8. Highlight the Novelty of Your Research:

Clearly explain the unique aspects or contributions of your study. Emphasize why your research is different from or builds upon existing work.

Here are some extra tips to increase the quality of your research background:

Example of a Research Background

Here is an example of a research background to help you understand better.

The above hypothetical example provides a research background, addresses the gap and highlights the potential outcome of the study; thereby aiding a better understanding of the proposed research.

What Makes the Introduction Different from the Background?

Your introduction is different from your background in a number of ways.

- The introduction contains preliminary data about your topic that the reader will most likely read , whereas the background clarifies the importance of the paper.

- The background of your study discusses in depth about the topic, whereas the introduction only gives an overview.

- The introduction should end with your research questions, aims, and objectives, whereas your background should not (except in some cases where your background is integrated into your introduction). For instance, the C.A.R.S. ( Creating a Research Space ) model, created by John Swales is based on his analysis of journal articles. This model attempts to explain and describe the organizational pattern of writing the introduction in social sciences.

Points to Note

Your background should begin with defining a topic and audience. It is important that you identify which topic you need to review and what your audience already knows about the topic. You should proceed by searching and researching the relevant literature. In this case, it is advisable to keep track of the search terms you used and the articles that you downloaded. It is helpful to use one of the research paper management systems such as Papers, Mendeley, Evernote, or Sente. Next, it is helpful to take notes while reading. Be careful when copying quotes verbatim and make sure to put them in quotation marks and cite the sources. In addition, you should keep your background focused but balanced enough so that it is relevant to a broader audience. Aside from these, your background should be critical, consistent, and logically structured.

Writing the background of your study should not be an overly daunting task. Many guides that can help you organize your thoughts as you write the background. The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to your research topic and should be done with strong knowledge and thoughtful writing.

The background of a research paper typically ranges from one to two paragraphs, summarizing the relevant literature and context of the study. It should be concise, providing enough information to contextualize the research problem and justify the need for the study. Journal instructions about any word count limits should be kept in mind while deciding on the length of the final content.

The background of a research paper provides the context and relevant literature to understand the research problem, while the introduction also introduces the specific research topic, states the research objectives, and outlines the scope of the study. The background focuses on the broader context, whereas the introduction focuses on the specific research project and its objectives.

When writing the background for a study, start by providing a brief overview of the research topic and its significance in the field. Then, highlight the gaps in existing knowledge or unresolved issues that the study aims to address. Finally, summarize the key findings from relevant literature to establish the context and rationale for conducting the research, emphasizing the need and importance of the study within the broader academic landscape.

The background in a research paper is crucial as it sets the stage for the study by providing essential context and rationale. It helps readers understand the significance of the research problem and its relevance in the broader field. By presenting relevant literature and highlighting gaps, the background justifies the need for the study, building a strong foundation for the research and enhancing its credibility.

The presentation very informative

It is really educative. I love the workshop. It really motivated me into writing my first paper for publication.

an interesting clue here, thanks.

thanks for the answers.

Good and interesting explanation. Thanks

Thank you for good presentation.

Hi Adam, we are glad to know that you found our article beneficial

The background of the study is the key to introduce your audience to YOUR research topic.

Awesome. Exactly what i was looking forwards to 😉

Hi Maryam, we are glad to know that you found our resource useful.

my understanding of ‘Background of study’ has been elevated.

Hi Peter, we are glad to know that our article has helped you get a better understanding of the background in a research paper.

thanks to give advanced information

Hi Shimelis, we are glad to know that you found the information in our article beneficial.

When i was studying it is very much hard for me to conduct a research study and know the background because my teacher in practical research is having a research so i make it now so that i will done my research

Very informative……….Thank you.

The confusion i had before, regarding an introduction and background to a research work is now a thing of the past. Thank you so much.

Thanks for your help…

Thanks for your kind information about the background of a research paper.

Thanks for the answer

Very informative. I liked even more when the difference between background and introduction was given. I am looking forward to learning more from this site. I am in Botswana

Hello, I am Benoît from Central African Republic. Right now I am writing down my research paper in order to get my master degree in British Literature. Thank you very much for posting all this information about the background of the study. I really appreciate. Thanks!

The write up is quite good, detailed and informative. Thanks a lot. The article has certainly enhanced my understanding of the topic.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- Background Note

- HBS Case Collection

The Big Five, Performance, & Hiring

- Format: Print

- | Language: English

About The Author