Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Concept Mapping

Creating a concept map is a way of organizing your brainstorming around key concepts.

This video from the University of Guelph offers a brief and helpful overview of concept mapping: [1]

Ready to get started with a concept map? This KPU learning aid can also help guide you through the process.

Let’s use our example where an instructor has given us the assignment: Write a 1,500 word persuasive essay that responds to the question: “Are transit services effective for Kwantlen University students?” Include your own perspective in your analysis and draw on two primary and two academic sources.

We’ll follow the seven steps of concept mapping outlined in the video above and I’ll include some examples.

- Identify the main topic

- Brainstorm everything you know about the topic

- Use relevant content from course, lectures, textbooks, and course material

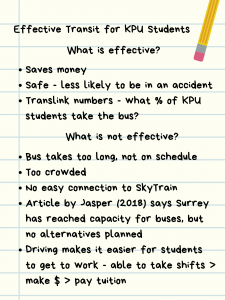

Sticky notes can be a great way of jotting down ideas – you can move the notes around as you begin to identify similarities and differences. You can also ask questions and include reminders of work that that you need to do. See the example below of some sticky notes I might use to start my assignment:

I’ll add more sticky notes with key questions that relate back to the assignment – I’ll need to find primary and academic sources:

I can use these questions as I begin my research process and identify the primary and academic sources I need to support the argument that I will make.

To find out more about the research process, ask a librarian , or check out the KPU Library’s Research Help guide.

This video, included in KPU Library’s Research Help page, provides a good overview of working with an assignment to make sure that you develop a response that is specific and well-supported:

- Organize information into main points

After noting down what I know about my topic and identifying key questions that I’ll need to research everything, I can focus on a few things that will be important to describe and analyze in my essay. I’ve made a list of some that I can use:

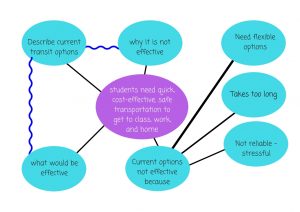

Based on what I’ve done so far, I’m setting up a descriptive comparison of transit options for KPU students, but will emphasize that current transit options are not effective. I want to look for further connections between ideas and see how I can shape my argument.

Step Three :

- Start creating map

- Begin with main points

- Branch out to supporting details

Give it a try! Based on your experience of public transit and the ideas that I’ve outlined so far, how might you start to create a concept map? You can use a piece of paper, or concept mapping software, to make note of ideas and start to connect them.

Step Four :

- Review map and look for more connections

- Use arrows, symbols, and colours, to show relationships between ideas

I start to build layers of connections and relationships in my map:

Step Five :

- Include details

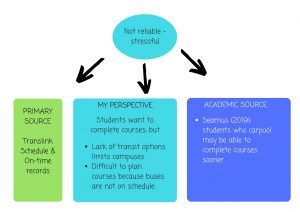

This is where I can provide more information about each point – below, I’ve taken one of the points and added to it:

- Analyze and improve map by asking questions

- How do ideas fit together?

- Have all necessary connections been made?

This is where I can step back and review my map and keep the purpose of my assignment in mind. This is also a good time to follow up on questions that I might have – I can talk through my ideas with a classmate or visit my instructor as I continue to develop and refine my ideas.

Step Seven :

- Update concept map as you learn more

- Ask key questions about connections between ideas

I’ll keep my map with me as I meet with my instructor to discuss my ideas and when I visit the library to locate any academic resources that I might need; this way, I can keep everything together.

- “ How to Create a Concept Map ” by University of Guelph Library CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

Academic Writing Basics Copyright © 2019 by Megan Robertson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Create a Mind Map for Essay Writing

Last Updated: December 1, 2023 Fact Checked

Generating Your Map

Organizing your map for writing, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 286,550 times.

If you’re a visual learner or just looking to switch up how you outline your essays, mind maps can be a game-changer. They make coming up with ideas for your essay and organizing them super easy. If you’ve never used a mind map for essay writing before, don’t worry—we break down everything you need to know to get started in the steps below.

Things You Should Know

- Get out a piece of paper and write your topic in the center. This can be a single word or sentence.

- Then, write down any words and ideas that relate to your topic. Circle them and then draw lines or arrows to connect them to the topic.

- Label each bubble idea according to where it fits into your paper. This can be a specific paragraph or a general section, like the introduction.

- Lay out the colored markers or pencils to which you have assigned meaning.

- Orient your paper so that it is in landscape position.

- If you don't have colored pencils or markers, don't worry. You can still make a mind map with just a pen or pencil!

- Circle your topic.

- Each thing you write down may give you another association. Write that down as well. For instance, writing "Impairment vs. disability" might remind you of "wheelchair ramps."

- Try to cluster related thoughts together ("wheelchair ramps"—"access to public life"), but don't worry if it doesn't always happen—you can draw a line between things you wish to connect.

- Look for connections between your unrelated thoughts and jot them into the picture.

- You might also label them "supporting argument," "evidence," "counterargument" etc.

- Include doodles if they occur to you, but again, don't get caught up in making them perfect.

- Depending on your age and essay topic, you might want to focus more on drawing pictures than writing out words.

- While there are plenty of programs available for purpose, you can also use free online mapping tools like Bubble.us, Mind42, or Coggle.

- Add details as you go. For instance, you may write some of the sources you are planning to use to the sections of your essay to which they apply.

- If you do this, you can start by drawing bubbles for the sections and continue by filling in the thoughts and associations.

- You can also organize your revised mind map into bubble for topic sentences that branch into smaller bubbles for supporting arguments and evidence.

- Once you've done this, you practically have a rough draft of your paper.

- Start each paragraph with a sentence that introduces the ideas of that paragraph, and write until you have incorporated all the information for that section.

- If you end up adding things that weren't on your map, look at your map to check that they fit, and consider penciling them in. One of the virtues of the map is that it keeps you on topic.

- Make sure you're not cramming too many points from your mind map into a single paragraph.

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.adelaide.edu.au/writingcentre/sites/default/files/docs/learningguide-mindmapping.pdf

- ↑ https://emedia.rmit.edu.au/learninglab/content/how-create-mind-map

- ↑ https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/using-concept-maps/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 20 May 2020.

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Mashudu Munzhedzi

Nov 21, 2016

Did this article help you?

Mar 8, 2017

Nov 8, 2023

Feb 19, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Introduction to Academic Reading and Writing: Concept Map

- Concept Map

- Select a Topic

- Develop a Research Question

- Identify Sources

- Thesis Statements

- Effective Paragraphs

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Quote, Paraphrase, Summarize

- Synthesize Sources

- MLA and APA

- Transitions

- Eliminate Wordiness

- Grammar and Style

- Resource Videos

Concept Maps

Create a concept map using your annotations and highlights of the text .

Define your map’s focus question and topic. Your focus question guides your map in a certain direction. What is the purpose of what you read? Your topic is what you are reading about.

Create a list of relevant concepts, thoughts and implications of your topic as you read. , think about the relationships between these concepts and begin to organize the list of concepts from broad to specific. you can set a topic at the center, with supporting points and details branching outwards, or you can create a hierarchy, with the topic at the top and its components below. , add links and cros s -links between related concepts and label these links with words or phrases to clarify the relationship between concepts., color code, add symbols, and personalize to your map so that is meaningful to you..

Check out these free online Concept Mapping tools:

- Lucid Chart

Video by McLaughlin Library, University of Guelph, 2017 .

Concept Map Example

Map by Penn State University , Concept Maps iStudy Tutorial

- << Previous: Annotate

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 12:23 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lbc.edu/Introtoacademicreadingandwriting

Concept Maps

What are concept maps.

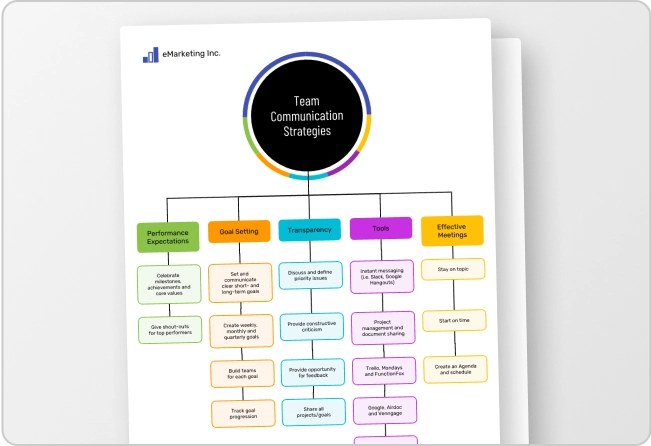

Concept maps are visual representations of information. They can take the form of charts, graphic organizers, tables, flowcharts, Venn Diagrams, timelines, or T-charts. Concept maps are especially useful for students who learn better visually, although they can benefit any type of learner. They are a powerful study strategy because they help you see the big picture: by starting with higher-level concepts, concept maps help you chunk information based on meaningful connections. In other words, knowing the big picture makes details more significant and easier to remember.

Concept maps work very well for classes or content that have visual elements or in times when it is important to see and understand relationships between different things. They can also be used to analyze information and compare and contrast.

Making and using concept maps

Making one is simple. There is no right or wrong way to make a concept map. The one key step is to focus on the ways ideas are linked to each other. For a few ideas on how to get started, take out a sheet of paper and try following the steps below:

- Identify a concept.

- From memory, try creating a graphic organizer related to this concept. Starting from memory is an excellent way to assess what you already understand and what you need to review.

- Go through lecture notes, readings and any other resources you have to fill in any gaps.

- Focus on how concepts are related to each other.

Your completed concept map is a great study tool. Try the following steps when studying:

- Elaborate (out loud or in writing) each part of the map.

- List related examples, where applicable, for sections of the map.

- Re-create your concept map without looking at the original, talking through each section as you do.

Examples of concept maps

Example 1 : This example illustrates the similarities and differences between two ideas, such as Series and Parallel Circuits. Notice the similarities are in the intersection of the 2 circles.

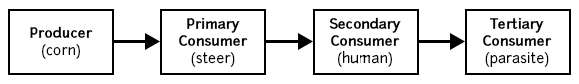

Example 2 : This example illustrates the relationship between ideas that are part of a process, such as a Food Chain.

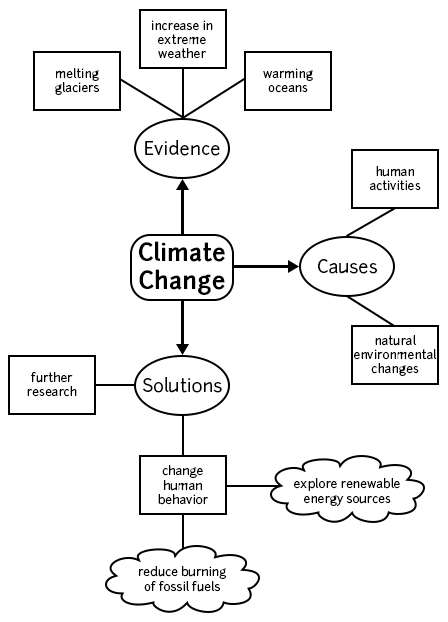

Example 3 : This example illustrates the relationship between a main idea, such as climate change, and supporting details.

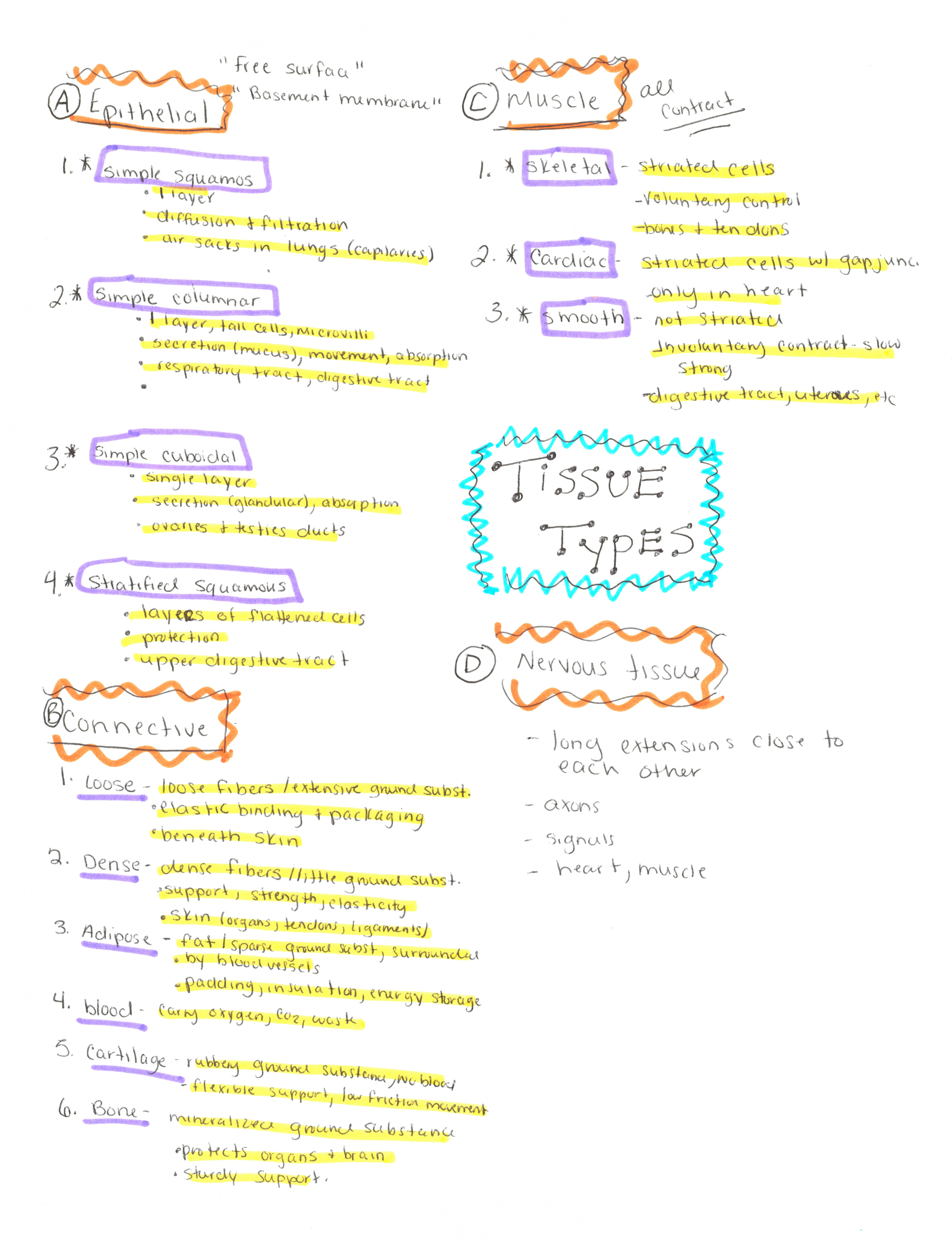

Example 4 : Outlining is a less visual form of concept mapping, but it might be the one you’re most familiar with. Outlining by starting with high-level course concepts and then drilling down to fill in details is a great way to determine what you know (and what you don’t know) when you’re studying. Creating an outline to start your studying will allow you to assess your knowledge base and figure out what gaps you need to fill in. You can type your outline or create a handwritten, color-coded one as seen in Example 5.

Additional study strategies

A concept map is one tool that you can use to study effectively, but there are many other effective study strategies. Check out these resources and experiment with a few other strategies to pair with concept mapping.

- Study Smarter, Not Harder

- Higher Order Thinking

- Metacognitive Study Strategies

- Studying with Classmates

- Reading Comprehension Tips

Make an appointment with an academic coach to practice using concept maps, make a study plan, or discuss any academic issue.

Attend a workshop on study strategies to learn about more options, get some practice, and talk with a coach.

How can technology help?

You can create virtual concept maps using applications like Mindomo , TheBrain , and Miro . You may be interested in features that allow you to:

- Connect links, embed documents and media, and integrate notes into your concept maps

- Search across maps for keywords

- See your concept maps from multiple perspectives

- Convert maps into checklists and outlines

- Incorporate photos of your hand-written mapping

Testimonials

Learn more about how a Writing Center coach uses TheBrain to create concept maps in our blog post, TheBrain and Zotero: Tech for Research Efficiency .

Works consulted

Holschuh, J. and Nist, S. (2000). Active learning: Strategies for college success. Massachusetts: Allyn & Bacon.

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

- Research Guides

Literature Review: A Self-Guided Tutorial

Using concept maps.

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Peer Review

- Reading the Literature

- Developing Research Questions

- Considering Strong Opinions

- 2. Review discipline styles

- Super Searching

- Finding the Full Text

- Citation Searching This link opens in a new window

- When to stop searching

- Citation Management

- Annotating Articles Tip

- 5. Critically analyze and evaluate

- How to Review the Literature

- Using a Synthesis Matrix

- 7. Write literature review

Concept maps or mind maps visually represent relationships of different concepts. In research, they can help you make connections between ideas. You can use them as you are formulating your research question, as you are reading a complex text, and when you are creating a literature review. See the video and examples below.

How to Create a Concept Map

Credit: Penn State Libraries ( CC-BY ) Run Time: 3:13

- Bubbl.us Free version allows 3 mind maps, image export, and sharing.

- MindMeister Free version allows 3 mind maps, sharing, collaborating, and importing. No image-based exporting.

Mind Map of a Text Example

Credit: Austin Kleon. A map I drew of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing in 2008. Tumblr post. April 14, 2016. http://tumblr.austinkleon.com/post/142802684061#notes

Literature Review Mind Map Example

This example shows the different aspects of the author's literature review with citations to scholars who have written about those aspects.

Credit: Clancy Ratliff, Dissertation: Literature Review. Culturecat: Rhetoric and Feminism [blog]. 2 October 2005. http://culturecat.net/node/955 .

- << Previous: Reading the Literature

- Next: 1. Identify the question >>

- Last Updated: Feb 22, 2024 10:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.williams.edu/literature-review

Accessibility links

- Skip to main content

- Skip to main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Improve Your Writing by Using Concept Maps

No media source currently available

- 128 kbps | MP3

- 64 kbps | MP3

English learners face a common problem: their writing often lacks clarity and cohesion .

That is according to Babi Kruchin and Alan Kennedy who teach at the American Language Program at Columbia University.

They recommend that English learners use concept maps – images that show how ideas are connected.

What is important is how you put it together

Let’s consider a comparison. In some ways, the writing process is like cooking.

Gathering the ingredients for a meal requires effort. But, understanding how to put all the ingredients together is far more difficult.

Similarly, learning nouns, adjectives, and verbs can be hard to do. But, putting them together into a meaningful story, email, or essay is what is difficult.

Doing these things becomes even more difficult when you are writing in a second language.

So, writing clear, cohesive paragraphs or essays, can be hard for English learners.

To overcome this problem, Kruchin and Kennedy recommend that students make concept maps before writing.

Kennedy says concept maps show a writer when his or her writing lacks clarity.

Kruchin adds that concept maps help visual learners – people who learn better by seeing ideas.

What are concept maps?

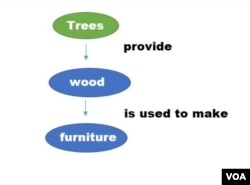

Concept maps are tools for organizing ideas. They usually have three parts: concepts, arrows, and linking phrases .

The concepts, which are the main ideas, are in circles or boxes. They are often nouns or noun phrases.

Arrows show how concepts are connected.

Linking words or phrases go above the arrows and explain how the concepts relate to one another.

Linking phrases are especially important. They are the groups of words that show relationships between concepts.

Joseph Novak, the creator of concept mapping, says such linking phrases give meaning to statements:

"If you say dog and food, those two concepts by themselves don't mean anything. They don't make a statement about the world. But if you say "dogs need food", then you begin to express an idea that's significant."

Novak adds that the linking words or phrases should be short. "You do not want a story between two concepts," he says, "just the expression that is needed to say, 'this concept is significantly related to another concept.'"

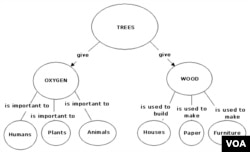

Generally, the generic ideas are at the top of the concept map and the specific ideas are at the bottom.

Kennedy explains what this looks like:

"So, for example, if you wanted to explain that trees provide wood, and wood is used to make furniture, you could have a circle around the word trees… and then you could have an arrow between the word wood and the word furniture, which would also be in a circle, and on top of that arrow it would say "is used to make""

From this starting point, writers can expand concept maps to include many concepts, arrows, and linking phrases.

Regardless of how simple or complex the map is, the most important point is that every concept has at least one arrow attached to it, and that every arrow has a linking word or linking phrase.

Building a concept map before writing an essay or email will make you think about how your ideas relate to one another.

You will realize when you are not explaining the relationships between ideas if you make a concept map that does not have arrows or linking phrases.

What can you do?

So, what can you do to start practicing concept maps?

You can start by reading and learning common linking words.

#1 Start by building a concept map of a paragraph

Kruchin recommends that English learners begin to use concept maps by studying the writing of others.

Learning how good writers have connected and developed ideas is an important starting point for learners who want to improve their own writing.

Kruchin adds that English learners should begin with a small amount of writing, such as a paragraph.

Kruchin suggests that English learners study the paragraph, or essay, by looking for the following information:

"The author's main idea is this, because of A, B, and C and here is one example to support A, one example to support B, one example to support C."

Doing this exercise, Kruchin adds, will give English learners information about how they can show relationships between ideas in their own writing.

#2 Learn common words and phrases that connect ideas

Kennedy recommends that English learners master words and phrases that show relationships between ideas. These linking phrases often show cause and effect or tell about the order of events.

English learners, Kennedy explains, should practice using a few of these phrases before moving to phrases that are more complex.

In particular, he recommends that English learners first use phrases such as "leads to", "causes", "is a type of" and "requires", before moving on to other phrases.

Read the article that goes with this story

Whether your goal is to write novels, poetry, or a message to a co-worker or friend, being able to show a relationship between ideas is an important skill.

Concept mapping might seem complicated, but Kennedy and Kruchin wrote an article that can help clarify their ideas. You can find the article on this page in PDF format. Download the article, read it, then try practicing with concept maps.

Let us know how concept maps work for you!

I'm John Russell.

John Russell wrote this story for Learning English. Mario Ritter was the editor.

We want to hear from you. Write to us in the Comments Section.

________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

cohesion – n. a condition in which people or things are closely united

concept – n. an idea of what something is or how it works

ingredient – n. one of the things that are used to make a food, product, etc.

overcome – v. to successfully deal with or gain control of (something difficult)

phrase – n. a group of two or more words that express a single idea but do not usually form a complete sentence

Using Concept Maps to Enhance Cohesion and Coherence in Academic Writing

Studying Sentence Patterns to Improve Your Writing: Part Two

Studying Sentence Patterns to Improve Your Writing: Part One

Improve Your Writing by Studying Critical Thinking

Center for Teaching

Beyond the essay, ii.

Print Version

Formative Activities: Snapshots of Learning in Process

Concept Maps & Word Webs || Word Clouds

As Bass noted in his Visible Knowledge Project work with faculty, what “most interested—or eluded—them about their students’ learning” involved the “’intermediate processes’” that occur before students write a paper or take an exam. They were particularly eager to “gather information not available from finished products such as papers or ephemeral evidence such as class discussion, which they could not study reflectively” (Bernstein & Bass, 2005, p. 39). These earlier stages in learning are often hidden, kept private in the students’ minds, leaving faculty to assume or guess what students think and know—or don’t.

This capturing of the learning-in-process is the goal of formative assessments, or low-stakes activities used to identify learning, gaps, and confusion well before the higher-stakes, summative assignments of essays, exams, and the like . This guide from the CFT offers a variety of such assessments (commonly called “CATs,” classroom assessment techniques), but one is particularly effective at making visible these rich, elusive, telling moments: concept maps.

Concept Maps & Word Webs

Students diagram their emerging frameworks, arguments, or narratives of personal understanding

Concept maps are diagrams of how students connect ideas, particularly effective at “externalizing and making visible the cognitive events of learning” (Kandiko, Hay, & Weller, 2012, p. 73). Word webs is an alternative term, most commonly used for concept maps made in collaborative groups (Barkley, Cross, & Major, 2005, p. 226-231). These “cognitive events” include making and defining connections, demonstrating hierarchies or chronologies, developing ideas through support and examples—and, when juxtaposing earlier and later concept maps, working out individualized frameworks of understanding, building an argument, forming more complex syntheses of ideas, and showing changes in thinking.

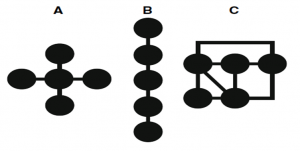

Developed for biology classes, concept maps are often scored quantitatively: thinking of each map as a spoke or a chain (outlined as A and B to the right), its quality is measured in the accuracy and comprehensiveness of its hierarchy of ideas and number of links (Kandiko, Hay, & Weller, 2012, p. 74). They can also be assessed qualitatively by thinking of them as networks (C, right), evaluated by the accuracy, quality, and complexity of their connections and interconnections (Hay, Wells, & Kinchin, 2008, p. 224). This latter purpose is perhaps one reason for the alternative term, “word webs.”

Even further, comparing two or more maps or webs by the same student can make visible changes in thinking—additive or “assimilative” thinking in which students incrementally map new ideas onto old ones, or conceptual thinking in which students eventually revise and build their own their structures for understanding a concept. Kandiko, Hay, and Weller’s “Concept Mapping in the Humanities to Facilitate Reflection: Externalizing the Relationship between Public and Personal Learning” (2012) focuses on this latter, conceptual approach, which they note is closer to the ways of constructing knowledge in the humanities. Progressive maps or webs can document “continual processes of rehearsal, revision and reflection among theory, argument and debate,” or “recreating meaning and personal understanding” (p. 77-78). The authors illustrate with a case study from a Classics course in which students were simply asked to make three concept maps—in the beginning, middle, and end of the semester—of the overarching course topic, “’The impact of Greek literature and culture on the Roman world’” (p. 74).

Unlike the original use of concept maps to assess comprehension and additive knowledge in biology classrooms, this approach uncovers the shift from a student’s public reproduction of others’ ideas and patterns to the process of creating the student’s own conceptual frameworks, arguments, and stories of the discipline.

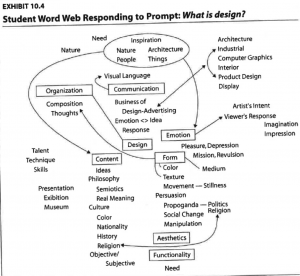

To the right is an example of a word web–similar to a concept map but with more emphasis on words and networks.

- “ Concept Mapping in the Humanities to Facilitate Reflection: Externalizing the Relationship between Public and Personal Learning ” (2012) by Kandiko, Hay, and Weller is a solid analysis of how concept maps are useful in the humanities and the source of the examples above.

Word Clouds

Students visualize and analyze shifts in their own understanding

Word clouds are visual representations of words emphasized by frequency. Like concept maps, individual word clouds document hierarchical thinking, in the sense of the words that are the most frequent (and thus largest) are presumably the most important–a very simple quantitative assessment. Also like concept maps, progressive examples can illustrate shifts in thinking. For example, a student could create a word cloud of earlier thinking (a written brainstorm, a blog post, an essay) and another of later thinking, and then reflect on the differences between the two. This analysis of the student’s own movement measured simply by word frequency initiates an act of more sophisticated metacognitive self-reflection: “How has my thinking about this concept changed?”

The same activity can be used for the entire class to demonstrate changes in thinking over the course of the semester. For instance, below are word clouds from a literary and film course on monsters from the first and last days of class is in response to the question, “What is a monster?” Students were then asked to analyze the two word clouds and articulate how the class’s understanding of monsters had changed during the course.

- Create word clouds with the Textal iPhone app.

Barkley, Elizabeth F., Cross, K. Patricia, & Major, Clair Howell. (2005). Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty . Jossey-Bass: San Francisco.

Bernstein, Dan, & Bass, Randy. (July/August 2005). The Scholarship of teaching and learning . Academe , 91( 4). 37-43.

Hay, David B., Wells, Harvey, & Kinchin, Ian M. (2008). Quantitative and qualitative measures of student learning at university level . Higher Education, 56 . 221-239.

Kandiko, Camille, Hay, David, & Weller, Saranne. (2012). Concept mapping in the humanities to facilitate reflection: externalizing the relationship between public and personal learning . Arts & Humanities in Higher Education , 12 .1. 70-87.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Essay Papers Writing Online

Master the art of crafting a concept essay and perfect your writing skills.

Every great work of literature begins with a spark of inspiration, a kernel of an idea that germinates within the writer’s mind. It is this concept, this central theme, that serves as the foundation of the entire writing process, guiding the writer along the creative journey. In the realm of academic writing, the concept essay holds a special place, as it requires the writer to explore abstract ideas, dissect complex theories, and present their understanding of a particular concept.

Unlike traditional essays where arguments are made, and evidence is provided, concept essays delve into the intangible realm of ideas, taking the reader on a captivating exploration of abstract concepts. These essays challenge the writer to convey their understanding of a concept without relying on concrete evidence or facts. Instead, they rely on the writer’s ability to provide clear definitions, logical explanations, and compelling examples that elucidate the intricacies of the concept at hand.

Effectively crafting a concept essay requires skillful mastery of language and an astute understanding of how ideas interconnect. It is a delicate dance between the power of words and the depth of thought, where metaphors and analogies can breathe life into otherwise elusive notions. The successful concept essay requires more than merely stating definitions or describing the concept; it necessitates the writer’s ability to engage and captivate the reader, transporting them into the realm of ideas where the abstract becomes clear and tangible.

Mastering the Art of Crafting a Conceptual Essay: Indispensable Suggestions and Instructions

Embarking on the journey of composing a conceptual essay necessitates an astute understanding of the complexities involved. This particular form of written expression empowers individuals to delve deeply into abstract concepts, unravel their intricacies, and articulate their findings in a clear and coherent manner. To accomplish this task with finesse, it is imperative to familiarize oneself with indispensable suggestions and instructions that pave the way to success.

1. Explore Profusely:

- Investigate, scrutinize, and immerse yourself in the vast realm of ideas, allowing your mind to explore a myriad of perspectives.

- Delve into diverse disciplines and subjects, sourcing inspiration and insight from a wide array of sources such as literature, art, philosophy, science, and history.

- Be cognizant of the fact that the more extensive your exploration, the richer your conceptual essay will be.

2. Define Your Focus:

- Once you have gathered an abundant collection of ideas, narrow down your focus to a specific concept that captivates your interest.

- Choose a concept that is both intriguing and stimulating, as this will fuel your motivation throughout the writing process.

- Strive to select a concept that possesses a level of complexity, rendering it ripe for analysis and interpretation.

3. Establish a Clear Structure:

- Prior to commencing the writing process, create a well-structured outline that delineates the key sections and points you wish to convey in your essay.

- Ensure that your essay possesses a clear introduction, body paragraphs that expound upon your chosen concept, and a comprehensive conclusion that ties together your arguments.

- Organize your thoughts in a logical manner, employing effective transitions that allow your essay to flow seamlessly.

4. Support your Claims:

- Avoid presenting mere conjecture or personal opinions; instead, bolster your arguments with credible evidence and examples.

- Cite reputable sources, such as scholarly articles, books, or studies, to lend credibility and authority to your assertions.

- Engage critically with the works of other esteemed thinkers, analyzing their viewpoints and incorporating them into your own exploration of the concept.

5. Polish and Perfect:

- Once you have crafted the initial draft of your conceptual essay, allocate ample time for revision and refinement.

- Engage in meticulous proofreading to eliminate any errors in grammar, punctuation, or syntax that may detract from the overall impact of your work.

- Solicit feedback from trusted peers or mentors, incorporating their suggestions into your final version.

In conclusion, mastering the art of crafting a conceptual essay demands diligent exploration, focused attention, and a commitment to delivering a well-structured and thought-provoking piece of writing. By following these essential tips and guidelines, you can navigate the intricacies of this unique form of expression and develop an essay that both captivates and informs its readers.

Understanding the Purpose of a Concept Essay

Having a clear understanding of the purpose behind writing a concept essay is crucial for creating a successful piece of writing. Concept essays aim to explore and explain abstract ideas, theories, or concepts in a way that is accessible and engaging to readers.

Although concept essays may vary in subject matter, their main objective is to break down complex ideas and make them understandable to a wider audience. These essays often require deep analysis and critical thinking to present the chosen concept in a comprehensive and enlightening manner.

A concept essay goes beyond simply defining a concept but delves deeper into the underlying principles and implications. It requires the writer to provide insight, examples, and evidence to support their claims and demonstrate a thorough understanding of the concept being discussed.

Concept essays also provide an opportunity for writers to explore new and innovative ideas and present them in a thought-provoking way. They allow for personal interpretation and creativity, encouraging writers to examine a concept from different angles and offer unique perspectives.

Furthermore, concept essays can be used as a tool for education and learning, helping readers expand their knowledge and gain a deeper understanding of various concepts. By breaking down complex ideas into more digestible forms, these essays enable readers to grasp abstract concepts and apply them to real-world situations.

In conclusion, the purpose of a concept essay is to convey abstract ideas or concepts in a clear and engaging manner, utilizing critical thinking and analysis. By presenting complex ideas in a comprehensive way, concept essays facilitate understanding and encourage readers to explore and expand their knowledge in the chosen subject area.

Choosing a Strong and Specific Concept

When it comes to crafting a well-written piece of work, selecting a compelling and precise concept is crucial. The concept you choose will serve as the foundation for your essay, shaping the content, tone, and direction of your writing.

Before diving into the process of choosing a concept, it’s important to understand what exactly a concept is. In this context, a concept can be defined as a broad idea or theme that encapsulates a particular subject or topic. It is the main point or central idea that you want to convey to your readers through your essay.

An effective concept should be strong, meaning it should be able to capture the attention and interest of your readers. It should be something that has depth and substance, allowing for exploration and analysis. A strong concept will engage your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

In addition to being strong, your concept should also be specific. It should be focused and clearly defined, narrowing down your topic to a specific aspect or angle. A specific concept will help you maintain a clear direction in your writing and prevent your essay from becoming too broad or unfocused.

To choose a strong and specific concept, start by brainstorming ideas related to your topic. Think about the main themes or issues you want to address in your essay. Consider what aspects of the topic interest you the most and which ones you feel are worth exploring further.

Once you have a list of potential concepts, evaluate each one based on its strength and specificity. Ask yourself whether the concept captures your interest and whether it has the potential to captivate your audience. Consider whether it is specific enough to guide your writing and provide a clear focus for your essay.

By choosing a strong and specific concept, you will set yourself up for success in writing your concept essay. Remember to select a concept that is compelling, focused, and meaningful to you and your readers. With a well-chosen concept, you will be able to create a thought-provoking and engaging essay that effectively conveys your ideas.

Developing a Clear and Coherent Thesis Statement

When crafting an effective essay, one of the most important elements to consider is the development of a clear and coherent thesis statement. The thesis statement acts as the central theme or main argument of your essay, providing a roadmap for your readers to understand the purpose and direction of your writing.

A well-developed thesis statement not only states your main argument but also provides a clear focus for your essay. It helps you organize your thoughts and ensures that your essay remains cohesive and logical. A strong thesis statement sets the tone for your entire essay and guides the reader through your main ideas.

To develop a clear and coherent thesis statement, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the topic you are writing about. Conducting research and gathering relevant information will help you form a solid foundation for your thesis statement. Make sure to analyze different perspectives on the topic and consider any counterarguments that may arise.

Once you have a good understanding of the topic, you can begin brainstorming and drafting your thesis statement. Start by considering the main idea or argument you want to communicate to your readers. Your thesis statement should be concise and specific, clearly conveying your main point. Avoid vague or general statements that lack focus.

In addition to being clear and concise, your thesis statement should also be arguable. It should present a debatable claim that can be supported with evidence and logical reasoning. This allows you to engage your readers and encourages them to consider different perspectives on the topic.

After drafting your thesis statement, it is important to review and revise it as needed. Make sure it accurately reflects the content and direction of your essay. Consider seeking feedback from peers or instructors to ensure that your thesis statement is clear, coherent, and effectively conveys your main argument.

In conclusion, developing a clear and coherent thesis statement is essential for writing an effective essay. It sets the tone for your entire essay, provides a clear focus, and guides the reader through your main ideas. By thoroughly understanding the topic, brainstorming and drafting a concise and arguable thesis statement, and revising as needed, you can ensure that your essay is well-structured and persuasive.

Structuring Your Concept Essay Effectively

Creating a well-organized structure is vital when it comes to conveying your ideas effectively in a concept essay. By carefully structuring your essay, you can ensure that your audience understands your concept and its various aspects clearly. In this section, we will explore some essential guidelines for structuring your concept essay.

1. Introduction: Begin your essay with an engaging introduction that captures the reader’s attention. This section should provide a brief overview of the concept you will be discussing and its significance. You can use an anecdote, a rhetorical question, or a thought-provoking statement to make your introduction compelling.

2. Definition: After the introduction, it is crucial to provide a clear definition of the concept you will be exploring in your essay. Define the concept in your own words and highlight its key characteristics. You may also include any relevant background information or historical context to enhance the reader’s understanding.

3. Explanation: In this section, you will delve deeper into the concept and explain its various elements, components, or features. Use examples, analogies, or real-life situations to illustrate your points and make them more relatable to the reader. Break down complex ideas into simpler terms and highlight the connections between different aspects of the concept.

4. Analysis: Once you have provided a thorough explanation of the concept, it is time to analyze it critically. Discuss different perspectives or interpretations of the concept and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses. Consider any controversies or debates surrounding the concept and present a balanced view by weighing different arguments.

5. Examples and Case Studies: To further support your arguments and enhance the reader’s understanding, include relevant examples and case studies. These examples can be from real-life situations, historical events, or fictional scenarios. Analyze how the concept has been applied or manifested in these examples and discuss their implications.

6. Conclusion: Conclude your concept essay by summarizing your main points and restating the significance of the concept. Reflect on the insights gained from your analysis and offer any recommendations or suggestions for further exploration. End your essay on a thought-provoking note that leaves the reader with a lasting impression.

By structuring your concept essay effectively, you can ensure that your ideas are presented coherently and persuasively. Remember to use clear and concise language, provide logical transitions between sections, and support your arguments with evidence. With a well-structured essay, you can effectively communicate your understanding of the concept to your audience.

Using Concrete Examples to Illustrate Your Concept

One effective way to clarify and reinforce your concept in a concept essay is by using concrete examples. By providing specific and tangible instances, you can help your readers grasp the abstract and theoretical nature of your concept. Concrete examples bring your concept to life, making it easier for your audience to understand and relate to.

Instead of relying solely on abstract theories, you can support your concept with real-life scenarios, research studies, or personal anecdotes. These examples add depth and relevance to your essay, making it more engaging and meaningful.

When choosing examples to illustrate your concept, it is important to select ones that accurately represent the core elements of your concept. Look for examples that exhibit the underlying principles, attributes, or behaviors that are associated with your concept.

For instance, if your concept is “leadership,” you can provide examples of influential leaders from history or modern-day society. These examples can demonstrate the qualities that define effective leadership, such as integrity, communication skills, and the ability to inspire and motivate others.

Additionally, when presenting concrete examples, ensure that they are relevant and relatable to your target audience. Consider the background and interests of your readers and choose examples that they can easily comprehend and connect with. This will enhance the effectiveness of your essay and create a stronger impact.

In conclusion, using concrete examples is a powerful technique for illustrating your concept in a concept essay. By incorporating specific instances, you can bring clarity, relevance, and authenticity to your writing. This approach allows your readers to grasp your concept more easily and appreciate its practical application in real-life scenarios.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, tips and techniques for crafting compelling narrative essays.

Get Started

Jan 27, 2016 | BRIEF

During the course of many years, I developed a methodology to organize and deliver corporate narratives. Earlier in my career, I used basic visual mind maps that helped clients outline and gain consensus on their core message. Eventually, I saw there was an opportunity for mind maps to help with more than messaging, which is how narrative maps were born.

While the narrative map began with General William Caldwell of the 82nd Airborne in the U.S. Army , we eventually evolved it to work for large multinationals and start-ups.

Today I’ll share with you what a narrative map looks like and how you can use it to deliver your message in a brief manner.

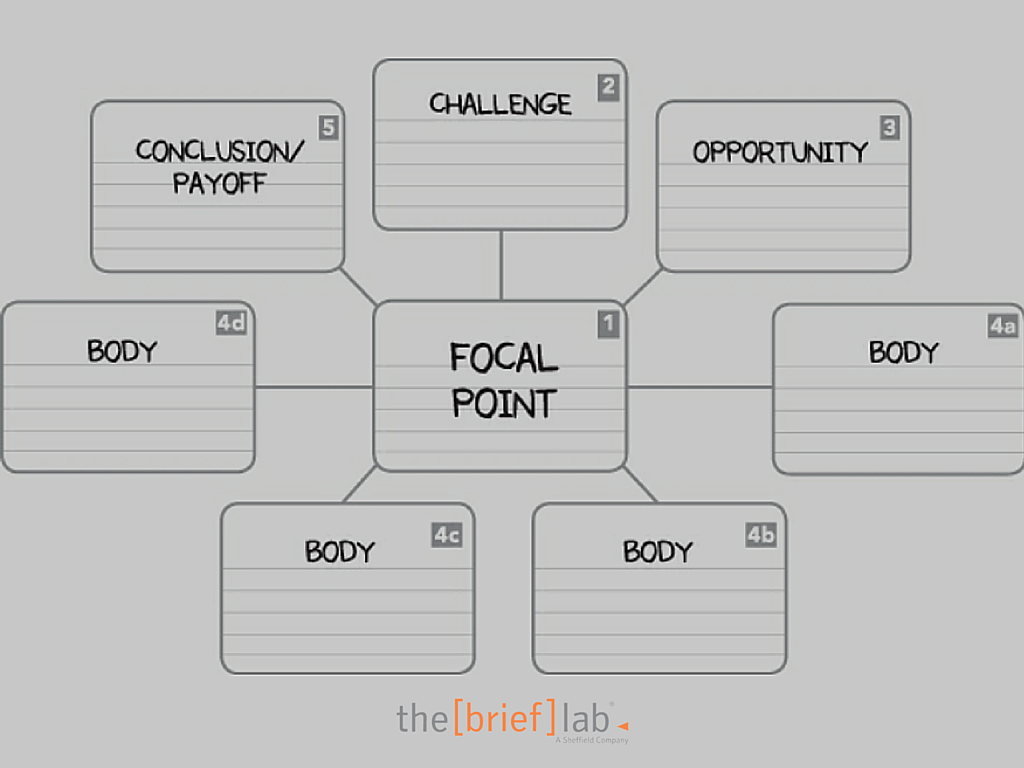

Narrative Map (De)constructed

Narrative maps consist of several important elements that make it easier to explain messages and give them clarity and context. They have a clockwise build; you begin with the center bubble and add bubbles around it clockwise.

There are five elements in a narrative map. We’ll take them one-by-one.

- Focal point (or center bubble) . This is the central part of a narrative. It’s akin to a headline , which explains and isolates the point of the story. Is the focal point about innovation, change, competition, or something else.

- Setup or challenge . What challenge, conflict, or issue exists in the marketplace your organization is addressing? Why does this problem exist? Who contributes to it? This begins to isolate the major issue within the story.

- Opportunity . What is the implication or the opportunity for your organization? This is what some people call an unmet need or an aha moment. This is something you could use to effect change or to address and resolve an issue.

- Approach . How does your story unfold? What are the three or four characters or key elements? What is the how, where, and when?

- Payoff . All good stories have a conclusion or payoff. How do you resolve the setup from the beginning? Let’s say your story is about innovation, and there are four ways the company is going to create something new. How is that going to benefit a customer, an employee, the industry, or the community? Where does that story conclude? Who sees the benefits?

When you translate boring business speak into a narrative map, you apply a filter that makes it interesting because it synthesizes volumes of information into a visual outline that produces a logical, strategic, contextual, and relevant story. It is a credible story because your organization firmly believes the story is true and will influence people. And it is concise because it’s on one page.

Use your narrative map to tell your story to a client, share it with key audiences such as investors, partners, and employees, or build morale with employees.

You will have people nodding their heads in real understanding in less than five minutes.

How will you use a narrative map?

Recent Posts

Focus on what matters most.

May 17, 2024

Focus on What Matters Most As the founder of The BRIEF Lab and the author of Noise: Living and Leading When Nobody Can Focus and BRIEF: Make a Bigger Impression by Saying Less I specialize in helping people become deliberate, clear, concise communicators. This blog is...

The 3 C’s of Communication: Clear, Concise, Consistent

Apr 11, 2024

The 3 C's of Communication: Clear, Concise, Consistent When it comes to effective communication, the 3 C's - Clear, Concise, and Consistent are essential. In this blog, we will discuss what these 3 C's of communication are and why they matter so much in our daily...

Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace

Apr 7, 2024

Emotional Intelligence in the Workplace In a workplace where teamwork and collaboration are essential for success, emotional intelligence is a critical skill. It is important for team building and also promotes healthy relationships with colleagues and clients. Here,...

[email protected]

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.3: Writing a Narrative Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6256

- Amber Kinonen, Jennifer McCann, Todd McCann, & Erica Mead

- Bay College Library

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

When writing a narrative essay, you may want to start by freewriting about topics that are of general interest to you.

Once you have a general idea of what you will be writing about, you should sketch out the major events of the story that will compose your plot. Often, these events will be revealed chronologically and climax at a central conflict that must be resolved by the end of the story. The use of strong details is crucial as you describe the events and characters in your narrative. You want the reader to emotionally engage with the world that you create in writing.

To create strong details, keep the five senses in mind. You want your reader to be immersed in the world that you create, so focus on details related to sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch as you describe people, places, and events in your narrative.

key takeaways

- Narration is the art of storytelling.

- Narratives can be either factual or fictional. In either case, narratives should emotionally engage the reader.

- Most narratives are composed of major events sequenced in chronological order.

- Time transition words and phrases are used to orient the reader in the sequence of a narrative.

- The four basic components to all narratives are plot, character, conflict, and theme.

- The use of sensory details is crucial to emotionally engaging the reader.

- A strong introduction is important to hook the reader. A strong conclusion should discuss the conflict and evoke the narrative theme.

Examples of Narrative Essays

- “Indian Education,” by Sherman Alexie

- “Us and Them,” by David Sedaris

- “Sixty-Nine Cents,” by Gary Shteyngart

- “Only Daughter,” by Sandra Cisneros

an Excelsior University site

- Online Reading Comprehension Lab

Using Concept Maps when Previewing before Reading

by Guest Contributor · Published June 17, 2019 · Updated December 8, 2021

This piece is republished from Dr. David C. Caverly’s Website with the author’s permission.

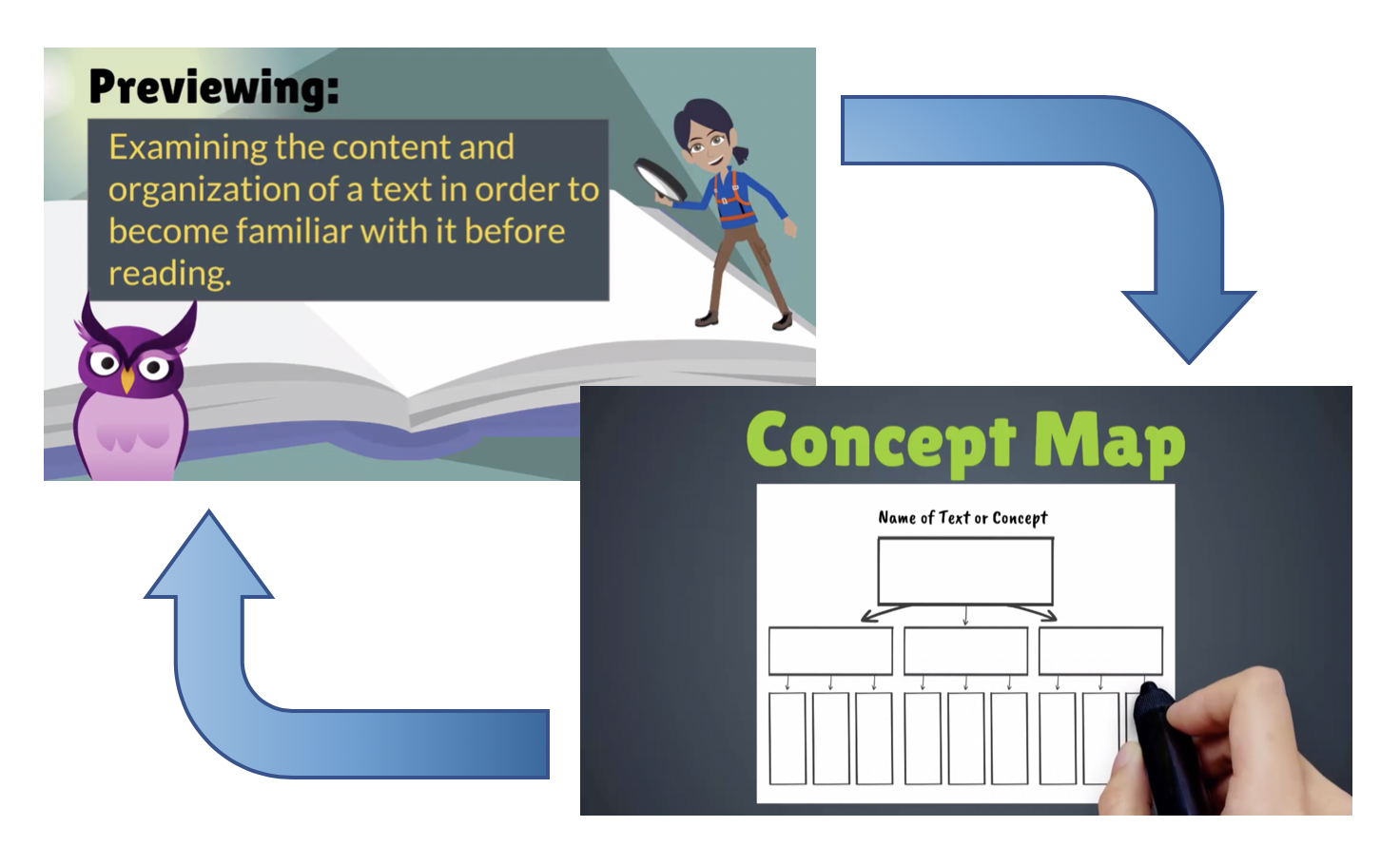

An important lesson I have learned over 40 years of teaching strategic reading to college developmental students has been they often come to me having been told what strategies to use, such as Previewing a text before reading. Consequently, many have learned the declarative knowledge of what Preview strategies are and encouraged to use them before reading. Seldom, however, have students been taught how to use the steps of a Previewing strategy (through procedural knowledge; Paris, Lipson, & Wixson, 1983); to monitor when the Previewing strategy is most effective and when it is not (through meta-cognitive knowledge); and to realize where a Previewing strategy is useful, such as in certain genres of text, or where the Previewing strategy might need to be adapted for other genres (through conditional knowledge).

Rarely have students been taught why a Previewing strategy will be more effective when they choose (through volitional knowledge) to combine an understanding-based strategy with a remembering-based strategy. That is, combining multiple strategies into a self-regulated strategic approach to Previewing develops multiple benefits for students. It helps them understand what they will be reading with Previewing, but it also helps them remember what was read, as well as how it is organized when creating a Concept Map as they Preview (Schroeder, Nesbit, Anguiano, and Adesope, 2018).

This blog will suggest 1 additional lesson with 3 additional activities you can use to help your students understand this how and why process when teaching a strategic approach by adding concept maps to Previewing before reading expository texts.

Lesson 1: Start with the resources present in the Preview module as they are very useful. For example, the Previewing lesson presents 8 excellent steps about what students should preview prior to reading a text and explains 3 benefits from using them.

Activity 1 : Follow up with the questions available in the Preview Activity module to confirm students understand the 8 strategies and the 3 benefits.

Lesson 2: Additionally, I have found it useful to guide students through how to learn to use Preview Concept Mapping by modeling for them how to create a handwritten, or digital concept map (similar to what is proposed in the Hoot’s Intern’s Corner: Concept Mapping blog). Evidence has suggested using previewing with concept maps will solidify their new procedural knowledge greater than previewing without a concept map (Khajavi & Abbasian, 2013). Modeling for students how to use Preview Concept Mapping creates two additional benefits before reading as it provides a visual source to organize the information gathered through previewing as well as it provides a place to determine what information is known and what information is unknown.

To model how to use Preview Concept Mapping for strategic reading, I have found it useful to teach explicitly using a Gradual Release of Responsibility instructional process (Pearson & Gallagher, 1973, 2011). Here, responsibility for learning is placed on the teacher as he/she models for student(s) how a given strategy is used through explicitly demonstrating the steps in the strategy within an authentic text. Next, the responsibility for learning is shifted to the student(s) through a guided practice experience where they apply the steps in a second authentic text and are monitored individually by the teacher (or in a classroom by their peers). Finally, the learning is evaluated by the student as he/she uses the strategy through independent practice using a different genre and without the support of the teacher. To foster this process, I have found using a considerate text (i.e., well structured, guided text) in this teaching process fosters the learning for the student as they are not hindered by less-than considerate, or inconsiderate text where some of the 8 elements are not present.

Activity 2 – Modeling Previewing with Concept Maps: To begin this activity, download Section 2.2 Religious upheavals in the developing Atlantic world which is a free, open-source, online section of a chapter within a college History text. This is an excellent example of a considerate text. If you would rather use a “hard copy” as a pdf, go to this same site and download the entire book by clicking on Get This Book. This will allow you to down the entire free, open-source U.S. History book. Navigate to page 34 in the pdf to Section 2.2.

Next, have your students navigate to Activity 2 by clicking on this link. Here, I strategically model how to create a Preview Concept Map.

When your student(s) finish Activity 2, you as instructor should lead the students to the Guided Practice.

Activity 3: Orchestrate a Guided Practice opportunity where the student applies what he/she learned in a less-than considerate expository text (includes some but not all of the 8 components, so students can adapt how they map). Through this activity, students are able to practice what they have learned by applying this learning to a similar section of the chapter, and have you (and/or their peers through a group activity) available to provide support as they create their map. Remember to make available just-in-time support to insure the responsibility for success is shared between instructor and the student (or perhaps even other students in a classroom setting).

Begin by asking the students to download the first section of the chapter for this Guided Practice by clicking on Activity 3:

- Chapter 2.1 – Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest

If they need additional practice, have them nagivate to the third section of this chapter:

- Chapter 2.3 – Challenges to Spain’s Supremacy

If you are teaching students individually, require the student to send you an e-mail of their Preview Concept Map for this first section of the chapter. Also, make sure you are available through your e-mail for questions or feedback as they work through creating a new Preview Concept Map in this guided practice.

If you are requiring this activity in a class, provide a blog space in your Learning Management System for students to ask questions, share their evolving Preview Concept Map, and get guidance from you or their peers.

Have them submit their Preview Concept Maps for this section of the chapter also to you or to their peers for group comparison and evaluation. Guided Practice can continue until the student feels competent with their ability to create a Preview Concept Map.

GO TO ACTIVITY 4

RETURN TO ACTIVITY 2

Once successful with the Guided practice, it is vital that the student(s) has (have) the opportunity to apply what they have learned about Previewing with Concept Mapping by transferring it (i.e., testing it out) on a chapter from another class in which you are enrolled which is not History.

This opportunity for transfer builds confidence in the student, and leads them to chapters that are not so considerate, where the strategies must be adapted. Adapting to new learning situations is vital to succeed in college.

Here is an Activity 4 where they are guided to Independent Practice.

Activity 4 – Independence Practice : Orchestrate an independent practice opportunity where students apply what they have learned to another class on a chapter they have to read in an attempt to transfer what they have learned.

Feel free to e-mail me as to whether these additional 3 activities were useful for your students.

Corbett, P. S., Janssen, V., Lund, J. M., Pfannestiel, T., & Vickery, P. (2018a). 2.1 Portuguese exploration and Spanish conquest. U.S. History (pp. 33 – 42). Houston, TX: Rice University Openstax. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:0lLioyXu@8/2-1-Portuguese-Exploration-and-Spanish-Conquest

Corbett, P. S., Janssen, V., Lund, J. M., Pfannestiel, T., & Vickery, P. (2018b). 2.2 Religious upheavals in the developing Atlantic world. U.S. History (pp. 42-46). Houston, TX: Rice University Openstax. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:R7-UnQRB@7/2-2-Religious-Upheavals-in-the-Developing-Atlantic-World

Corbett, P. S., Janssen, V., Lund, J. M., Pfannestiel, T., & Vickery, P. (2018c). 2.3 Challanges to Spain’s supremacy. U.S. History (pp. 46-51). Houston, TX: Rice University Openstax. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:2v4PHpcf@8/2-3-Challenges-to-Spain-s-Supremacy

Corbett, P. S., Janssen, V., Lund, J. M., Pfannestiel, T., & Vickery, P. (2018d). 2.4 New worlds in the Americas: Labor, commerce, and the Columbian exchange. U.S. History (pp. 52-58). Houston, TX: Rice University Openstax. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:YYfUmm0Y@4/New-Worlds-in-the-Americas-Labor-Commerce-and-the-Columbian-Exchange

Fowler, S., Roush, R., & Wise, J. (2017). 1.2 The process of science. In Concepts of Biology (pp. 16-26). Houston, TX: Rice University Openstax. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:RD6ERYiU@10/1-2-The-Process-of-Science

Hambline, G. (2019, March 14). Intern’s Corner: Concept Mapping [web log comment]. Retrieved from https://hoot.excelsior.edu/

Khajavi, Y., & Abbasian, R. (2013). Improving EFL Students’ Self-regulation in Reading English Using a Cognitive Tool. Journal of Language & Linguistics Studies, 9 (1), 206-222.

Paris, S. G., Lipson, M. Y., & Wixson, K. K. (1983). Becoming a strategic reader. Contemporary Education Psychology, 8 (3), 293-316.

Pearson, P. D. (2011). Toward the next generation of comprehension instruction: A coda. In H. Daniels (Ed.), Comprehension going forward (pp. 243-253). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Pearson, P. D., & Gallagher, M. (1983). The instruction of reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 8 , 317-344.

Previewing. (n.d.). Excelsior Online Reading Lab . [Online Multimedia] Retrieved from https://owl.excelsior.edu/orc/what-to-do-before-reading/previewing/

Previewing: Activity. (n.d.). Excelsior Online Reading Lab . [Online Multimedia] Retrieved from https://owl.excelsior.edu/orc/what-to-do-before-reading/previewing/previewing-activity/

Schroeder, N. L., Nesbit, J. C., Anguiano, C. J., & Adesope, O. O. (2018). Studying and Constructing Concept Maps: a Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30 (2), 431-455. doi: 10.1007/s10648-017-9403-9

Tags: Comprehension Concept Mapping Conditional Knowledge Gradual Release of Responsibility model hoot Previewing Procedural Knowledge

- Next story The Professor’s Perch: Don’t Be Fooled by Logical Fallacies

- Previous story The Professor’s Perch: Summer’s Here and It’s Time for a Writing Refresher

Write | Read | Educators

- Hoot! The OWL Blog

- About Hoot!

- Contact the Editor

- Anti-Plagiarism

- Argument and Critical Thinking

- Excelsior Edition

- Format & Documentation

- Grammar & Style

- OWL for Educators

- The Rhetorical Effect

- The Writing Process

- Writing Across Disciplines

Recent Posts

- Navigating Your Nursing Journey: Pursuing a Degree Online at Excelsior University

- Less Is More When Grading Papers

- Creating Effective Class Presentations Using the Excelsior OWL Presentation Resources

- Just Like a Conversation

- Embedding APA Refresher Content in an Online Orientation Course

- The Professor’s Perch: Questioning – As American as Apple Pie

- The Professor’s Perch: Quit Facebook and Start Writing Again with Prewriting Strategies

- Using Concept Maps when Previewing before Reading »

Transform teamwork with Confluence. See why Confluence is the content collaboration hub for all teams. Get it free

- The Workstream

- Project management

- Concept mapping

What is a concept map and how do you make one

Browse topics.

Concept maps are visual tools for organizing and representing knowledge and ideas in a graphical format. They consist of concepts (or nodes) with connected lines to illustrate their relationships and hierarchy. Concept maps are useful for organizing information, solving problems, and making decisions. They also help with information sharing and collaboration by allowing contributors to convey ideas in an easily understandable format. This format provides a deeper understanding of complex topics. This guide will discuss concept maps, their key features, and how to use one to benefit your team's decision-making process .

What is a concept map?

A concept map is a visual representation that illustrates the relationships between different concepts, ideas, or information. Concept maps typically portray ideas as boxes or circles, known as nodes, and organize them hierarchically with interconnected lines or arrows, known as arcs. These lines have annotated words and phrases that describe the relationships to help understand how concepts connect.

Concept map key features

While concept maps share similarities with other visual tools, they possess distinct features that set them apart. These characteristics contribute to their effectiveness in organizing information and visually representing relationships within a particular knowledge domain. Below are the essential components of a concept map and how they work together.

Concepts are the fundamental thoughts, ideas, or topics within the concept map. They serve as the building blocks for organizing information. For example, if a concept map represents a business plan, it could include concepts such as marketing strategies, financial planning, supply chain management, and other key components of the business strategy.

Linking words or phrases

Linking words or phrases describe the relationship between connected concepts. They allow the viewer to understand the flow of information and how the nodes interconnect. Examples of linking words or phrases are “is a part of,” “leads to,” “requires,” “is dependent on,” etc.

Propositional structure

Propositions are statements that combine two or more concepts using linking words. Also known as semantic units or units of meaning, they form the basis for generating new knowledge within a specific domain. Visually depicting interconnected propositions contributes to a greater understanding of the subject matter. In a business plan example, a propositional structure to connect two concepts could look like “marketing strategies increase brand awareness.”

Hierarchical structure

The hierarchical structure positions the most general and inclusive concepts at the top and arranges more specific concepts underneath.

Reading the concept map from top to bottom provides an understanding of concepts from broader categories to more detailed and specific ones.

In a business plan example, the overall business strategy would be at the top level, followed by sub-levels such as marketing strategy, finance, and human resources.

Parking lot

The parking lot is an area for unrelated ideas. It’s a ranked list, starting with the most general concepts and moving to the most specific. It serves as a holding space for ideas until you can determine their appropriate places in the concept map.

Cross-links

Cross-links represent connections between concepts in distinct areas of the map. They enable the visualization of relationships between ideas from diverse domains.

For example, in a concept map for a business plan, you may cross-link market research (part of marketing strategy) and financial forecasting (under financial planning), as insights gained from market research can inform your forecasting and budgeting decisions.

Types of concept maps

The implementation and arrangement of concept maps can vary. Here are four primary types of concept maps:

- Spider maps : Also known as spider diagrams, these concept maps resemble a spider web. The central concept is in the center, and the related topics branch out. This type is most effective when delving into different aspects of a central concept.

- Flowcharts : A flowchart is a visual depiction of a process or workflow. Its linear structure guides readers through the information step-by-step. (See also: how to make a flowchart ).

- System maps : Rather than connecting all ideas to a central concept, a system map concentrates on the relationships between ideas without a clearly defined hierarchical structure.

- Hierarchy maps : Hierarchy maps illustrate rank or position. The primary idea or the concept with the highest rank sits at the top while lower-ranking ideas flow underneath in a structured manner.

How to make a concept map

To create a concept map, follow these steps:

- Identify your primary topic. Ensure that your topic is broad enough to allow for subtopics. You should position this central concept at the top or center of your map, forming the basis of the hierarchical structure.

- Identify the essential concepts relating to the central topic. Place these concepts in the parking lot—a temporary space to store ideas—and arrange them from most broad to most specific.

- Move the key concepts from the parking lot to the concept map, prioritizing the broadest ideas that directly relate to the main topic. Establish the connections between concepts with linking words.

- Double-check the map for accuracy, ensuring the relationships are clear and linking words are coherent. Use cross-links to connect concepts across different sections of the map.

- Expand and revise the map as you generate more ideas.

How to use a concept map

Concept maps have practical applications and offer various benefits in different industries. They help visualize the relationships between various concepts, providing a deeper understanding of complex subjects. Concept maps help individuals retain and understand concepts and their relationships by organizing and illustrating connections between ideas. While concept maps are popular in academia, their adaptability makes them a valuable tool in many fields. Using a concept map:

- Enhances understanding of complex topics

- Organizes information

- Facilitates critical thinking

- Improves team collaboration and communication

- Provides flexibility for generating new ideas and evolving existing ones

Content map examples

Businesses can use concept maps in various ways to enhance communication, decision-making , and knowledge sharing . Here are some ways businesses can apply concept maps:

- Product development : Teams can use concept maps to organize and visualize ideas, features, and requirements in a brainstorming session .

- Project management : By organizing tasks, mapping dependencies, and displaying the project timeline , teams can better visualize the project life cycle .

- Sales funnel : Sales teams can use a concept map to visualize and optimize the sales funnel, mapping the customer journey from lead generation to conversion.

Use Confluence whiteboards for concept mapping

Concept maps are versatile and valuable tools that contribute to enhanced understanding, effective communication, and collaborative problem-solving.

For collaborative concept mapping, use Confluence whiteboards . Confluence whiteboards are an essential tool for any collaborative culture , enabling teams to create and work together freely on an infinite canvas. They bring flexibility to projects, supporting teams as they move from idea to execution.

Confluence whiteboards bridge the gap between where teams think and where teams do. Brainstorming with Confluence whiteboards helps teams organize their work visually and turn ideas into reality, all within a single source of truth.

Try Confluence whiteboards

Content mapping: Frequently asked questions

What is the difference between mind mapping and concept mapping.

While mind mapping and concept mapping are visual techniques for organizing and representing information, they have a few key differences. Mind maps organize thoughts for brainstorming and problem-solving, while concept maps organize thoughts to emphasize the connections between ideas. A mind map tends to be more free-flowing and lacks a hierarchy, while a concept map has a structured layout that represents relationships and hierarchy.

What is the best tool for concept mapping?

The best concept mapping tool depends on your collaboration requirements and ease of use. To bring your work together in a single source of truth, easily provide access to all contributors, and turn your ideas into reality, try Confluence whiteboards.

Can I collaborate on a concept map?

Yes, collaboration is possible on a concept map. A concept map is a productive tool for gathering insights from multiple contributors, especially when using a dedicated platform that supports collaborative editing such as Confluence whiteboards.

You may also like

Project poster template.

A collaborative one-pager that keeps your project team and stakeholders aligned.

Project Plan Template

Define, scope, and plan milestones for your next project.

Enable faster content collaboration for every team with Confluence

Copyright © 2024 Atlassian

How to Write a Narrative Essay

Essay writing comes in many forms, not all of which require extensive research. One such form is the narrative essay, which blends personal storytelling with academic discussion. Authors of these essays use their own experiences to convey broader insights about life.

This genre offers writers a unique chance to connect with readers on a personal level. By sharing experiences and reflections, authors engage their audience emotionally while conveying important messages or lessons. In the following sections, our custom term paper writing experts will explore various aspects of narrative writing, from choosing a topic to effectively structuring your essay!

What Is a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay is a piece of writing that tells a story, often based on personal experiences. Unlike academic or journalistic writing, which sticks to facts and a formal style, narrative essays use a more creative approach. They aim to make a point or impart a lesson through personal stories. These essays are commonly assigned in high school or for college admissions. An effective narrative essay typically follows a chronological order of events and has three main traits:

- Has one main idea.

- Uses specific facts to explain that idea.