Exploring user experience of learning management system

International Journal of Information and Learning Technology

ISSN : 2056-4880

Article publication date: 15 July 2021

Issue publication date: 12 August 2021

This paper aims to explore the perspectives of university students on the learning management system (LMS) and determine factors that influence user experience and the outcomes of e-learning.

Design/methodology/approach

This paper employs a mixed-method approach. For qualitative data, 20 semi-structure interviews were conducted. Moreover, for quantitative data, a short survey was developed and distributed among the potential respondents.

The results showed that students, particularly in programs where courses are mainly offered online, are dependent on such learning platforms. Moreover, the use of modular object-oriented dynamic learning environment (Moodle) as an application of LMS was rated positively, and e-learning was considered as an effective sustainable learning solution in current conditions.

Originality/value

The authors have illustrated empirically how the notion of UX of the LMS provides a means of exploring both students' participation in e-learning and their intention towards using such learning platforms.

- Computer-assisted learning

- Learning management systems

- User experience

Maslov, I. , Nikou, S. and Hansen, P. (2021), "Exploring user experience of learning management system", International Journal of Information and Learning Technology , Vol. 38 No. 4, pp. 344-363. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-03-2021-0046

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Ilia Maslov, Shahrokh Nikou and Preben Hansen

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The development of the information and communication technologies (ICTs) and Internet have changed the way educational services are delivered in higher education ( Shaltoni et al. , 2015 ). In addition, the widespread use of learning management system (LMS) stands for a significant technological development in higher education and due to the challenging situation, many educational institutions have been forced to move to distant- and online-only education. In addition, the sudden and unexpected shift in teaching and learning modes has given rise to the use of information and communication technology to support learning. For example, modular object-oriented dynamic learning environment (Moodle) platform, an application of an LMS is being increasingly used to facilitate e-learning ( Dogoriti et al. , 2014 ; Lisnani and Putri, 2020 ). E-learning is an effective sustainable learning solution and offers tremendous opportunities for learning beyond the traditional boundaries. For example, increased reach to thousands of learners, facilitating the interaction between learners and educators, collaborative learning, and facilitating the teaching process planning ( Bansode and Kumbhar, 2012 , p. 415). However, despite the massive use of such learning platforms, there are multiple factors, which could potentially impact the outcomes and the results of e-learning. The two of which are (1) learner's perceptions about e-learning and (2) the information technology (including the quality, reliability, ease of use and usefulness) used to facilitate e-learning ( Benigno and Trentin, 2000 ; Sun et al. , 2008 ). While, the purpose of such systems is to provide quality education and training, students' intention to adopt and use LMSs is instrumental to the outcome of e-learning. In addition, the success of e-learning is highly dependent on the users' experience and perceptions towards such systems. The user experience (hereinafter UX) is a broad phenomenon describing how the LMS is perceived and used in e-learning processes. UX of both learners' and teachers' of LMS platforms, while considered to be crucial, influences the process of teaching and learning ( De Carvalho and Silva, 2008 ; Jeong, 2016 ; Nakamura et al. , 2017a ; Zaharias and Pappas, 2016 ; Zanjani, 2017 ).

Other interpretations of the UX add that UX explores how a person feels about using a product-e.g. the experiential, affective, meaningful and valuable aspects of product use ( Vermeeren et al. , 2010 ). Moreover, UX models are often regarded as objective part (e.g. functionality, reliability, usefulness and efficiency of the system) and subjective parts (e.g. attractiveness, appeal, pleasure, satisfaction of the system) ( Laguna Flores, 2019 , p. 23). Therefore, we use this distinction when interpreting the respondents' perceptions of UX. During the software development of learning systems, usability and user acceptance are considered highly significant as these systems are used by people with varied skill sets (administrators, students, teachers) ( Krishnamurthy and O'Connor, 2013 ). Simultaneously, in many software developments companies, usability and UX are either neglected or not properly considered. To resolve this, Ardito et al. (2014) suggested that public organisations should explicitly mention the usability and UX requirements in the calls for tenders for ICT products. In a recent study, Butt et al. (2020) argue that ICTs are the powerful and important tools for advancement, growth, reform, alteration, development and transformation in education (p. 350).

From a theoretical standpoint, current literature on e-learning and LMS are predominantly quantitative and focuses on technology adoption through the use of classical theoretical frameworks such as Technology Acceptance Model (TAM: Davis, 1989 ) and usability testing ( Nakamura et al. , 2017b , p. 1015). However, technology adoption and UX models are rarely compared with each other, despite that both allow for exploring the experiential component in human-computer interactions, providing rich insights about the factors that influence the adoption and the use of technology and how they are related ( Hornbæk and Hertzum, 2017 ). Studies (i.e. technology adoption and UX models) have significant overlaps in the phenomenon that they seek to explore: the experience of use and how it affects the actual and intended use ( Hornbæk and Hertzum, 2017 ). In the e-learning process, learners' feedback could be used at the evaluation stage for the consequent improvement of the process by the design team ( Khan, 2004 ). All organisations developing LMSs seek to improve their products, of which UX is a major part ( Cavus and Zabadi, 2014 , p. 525). The identification and evaluation of the UX elements addressed during the design of the product or service are crucial for innovation ( Krawczyk et al. , 2017 ). However, to date, none of the research in usability and UX of LMSs proposed solutions to the identified issues in usability and UX of studied LMS ( Nakamura et al. , 2017a ). As such, for a better evaluation of LMS in a given context, we argue that a qualitative-based research could be an alternative approach allowing users to express their perceptions and to make questions specific to the UX and the features of LMSs. With this approach, we respond to earlier Nakamura et al.’ s (2019) call who outlined the need for methods where it is possible to investigate UX of LMS, allowing users to supply a detailed overview of their experiences.

This paper aims to address this limitation by performing research in a pragmatic stance, which includes users' feedback on the UX of an LMS to propose potential solutions to identify issues of the UX and usability of an LMS. To do so, we use Moodle as an application of LMS and use university students as the potential users of LMS to perform our research. Moodle-based e-learning platform enables teachers to use multiple teaching tools like question banks, assignments, feedback, forums, and quizzes, enabling students to enrich their learning experience ( Bansode and Kumbhar, 2012 , p. 415). We explicitly use Moodle, as it is among the most widely used LMS platforms in the world, having up to 60% of the market share ( Kuran et al. , 2017 ; Machado and Tao, 2007 ; Teo et al. , 2019 ). While there are no significant differences in terms of features between different LMSs ( Al-Ajlan, 2012 ; Poulova et al. , 2015 ), differences might exist in terms of UX ( Sahid et al., 2016 ; Nichols, 2016 ) and different contexts of the LMS use, such as different cultures ( Wang et al. , 2013 , p. 76).

The research questions guiding this research are “ What factors impact the university students' perceptions of the UX of LMS?” and “what the potential solutions to the challenges of the UX identified by the university students”? To answer the research questions and to address the previously mentioned research gap, this qualitative research employs a holistic UX model developed by Topolewski et al. (2019) and conducted several semi-structured interviews with the informants.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. First, we offer the literature review of the core concepts such as UX, e-learning and LMS, followed by a discussion of the theoretical framework. Second, the methodology is described. Third, then results are provided, and finally, we present discussion and conclusions.

2. Literature review

2.1 user experience (ux) and usability.

UX is associated with a broad range of fuzzy and dynamic concepts, including emotional, affective, experiential, hedonic and aesthetic variables ( Hassenzahl and Tractinsky, 2006 ).

The unit of analysis for UX is too malleable, ranging from a single aspect of an individual user's interaction with a standalone application to all aspects of multiple users' interactions with the company and its merging of services from multiple disciplines ( Sward, 2006 ).

The landscape of UX research is fragmented and complicated by diverse theoretical models with different foci such as pragmatism, emotion, affect, experience, value, pleasure, beauty, hedonic quality, etc. ( Law et al. , 2008 ).

There are also two opposing views on how UX should be studied and evaluated (i.e. quantitative and qualitative)–an argument rooted in the classical philosophical debate on reductionism versus holism ( Law et al. , 2014 ), despite that UX itself may change over time ( Fenko et al. , 2010 , p. 34). While, both UX and usability play important roles in measuring the quality of the use of LMSs and the e-learning process, these two may be considered as somewhat overlapping concepts ( Nakamura et al. , 2017b ). Usability is generally regarded as ensuring that interactive products are easy to learn, effective to use and enjoyable from the user's perspective. Usability has also several goals for interactive products. For instance, they must be effective to use, efficient to use, safe to use, having good utility, easy to learn, and easy to remember how to use ( Rogers et al. , 2007 , p. 20). Then, we may indeed see certain overlaps with the UX definition provided above in terms of how users evaluate their use of the product (where the key element in usability definition is use, so as in UX). Bevan (2008) argued that the UX and usability might share the goals of being efficient, effective and satisfying to use, but usability is more quantitative-oriented and more objective in nature (e.g. website speed and efficiency of work, frequency of the appearance of specific errors when evaluating the use of the system). While, on the one hand, usability can be considered as a part of UX, or as a separate concept measuring the use of the product objectively and pragmatically, very often with the quantitative-based techniques. The UX is then entirely subjective and hedonic, hence it is harder to evaluate it with quantitative methods. Thus, there are two distinct goals regardless of terminology: optimising human performance and optimising user satisfaction with achieving both pragmatic and hedonic goals ( Bevan, 2009 ). In our research, through the perspective of the UX model that is employed, we are addressing the usability as a phenomenon that is encapsulated in the broader UX.

In addition to the above discussion on UX and usability, it is important to address the user-centred design (UCD) as an important element of the UX model. UCD is an approach to design processes whereby a trained researcher observes and/or interviews largely passive or reactive users, whose contribution is to perform instructed tasks and/or give their opinions about the product concepts that were not generated by the users ( Sanders and Stappers, 2008 , p. 5). Furthermore, UCD can be characterised as a broad term to describe a broad philosophy, a variety of methods and approaches to design processes, whereby there is a spectrum of ways how users are involved in UCD ( Abras et al. , 2004 , p. 445). Detweiler (2007) considered UCD to be an iterative process of three phases: (1) understanding users (observing and interviewing end-users and other stakeholders to gather requirements), (2) defining interaction (creating use cases based on the output from phase one) and (3) user interface (UI) design (iterative creations and evaluations of prototypes). UCD then helps to design the product in a way that users need, and organisational goals are considered simultaneously, bringing value to both sides.

To this end, UX is very often about the value of the product and how this value is experienced by the users, so that organisational goals are met. Simultaneously, usability is very often dealing with the UI of an interactive product and how it is designed so that the tasks can be executed. This can be measured using efficiency, effectiveness and satisfaction. Thus, while employing UCD, both UX and usability are considered. In this research, we employ UCD to focus on users' needs, how the value of the product (LMS) is experienced by users, identifying potential challenges and then proposing the solutions, so that the organisation (i.e. university in our research) could meet better its goals (i.e. better educational outcome) in a pragmatic research approach.

2.2 E-learning

E-learning as a paradigm of modern education is the use of telecommunication technology to deliver information for education and training ( Sun et al. , 2008 ). E-learning participation refers to the teaching and learning facilitated and supported by Internet technologies ( Garrison and Anderson, 2003 ). E-learning is an iterative process that goes from the planning stage through design, production and evaluation to delivery and maintenance stages ( Khan, 2004 ). In this research, e-learning refers to the overall technological system for delivering teaching and learning, whereas participation in e-learning is the act of use of telecommunication to deliver teaching and learning within such a system. Fleming et al. (2017) identified (1) low perceived complexity of the e-learning system, (2) perception of the taught knowledge as useful and (3) availability of technical support, as some of the potential predictors of future use and overall satisfaction of using e-learning. In addition, personal perceptions about e-learning could influence attitudes and impact whether a user would intend to participate in e-learning in the future ( Sun et al. , 2008 ). Service quality (supportiveness of the service), information quality (learning content and interactivity) and system quality (attractive and ease of use of the website interface) are also different aspects of e-learning quality ( Uppal et al. , 2018 ). These might affect the aspects and perceptions of the UX of LMS. Hence, in this research, while e-learning is about the use of IT for providing teaching and learning, UX is about studying the use of those IT systems, and hence we draw connections between these two phenomena. Other research in the area is in line with this assumption as it has been argued that UX of LMS platforms may influence the process of online teaching and learning ( De Carvalho and Silva, 2008 ; Jeong, 2016 ; Nakamura et al. , 2017a ; Zaharias and Pappas, 2016 ).

Moreover, there are both advantages and disadvantages to e-learning. On a more positive side, e-learning allows for a learner-centred, self-paced, cost-effective way of learning. However, there is a lack of social interactions, potentially uncomfortable for some people, and higher degrees of frustration and confusion, with higher preparation time for instructors ( Zhang et al. , 2004 ). It should be noted that this research focuses mainly of e-learning in the university settings and we do not intend to focus on the pedagogical elements of e-learning or discuss the different actors involved in e-learning. We also do not discuss the rise of additional costs and investments in developing a mixed (hybrid) teaching model.

2.3 Learning management system (LMS) moodle

Web-based information systems are systems based on web technology and provide new approaches to design and development compared to the traditional computer software. LMS is a powerful software system enhancing learning ( Brusilovsky, 2003 ). Onofrei and Ferry (2020 , p. 1568) argued that such tools can be used to supplement traditional classroom teaching, and to enhance students' learning in a more efficient manner than students taught in a face-to-face learning environment. The LMS, as a type of e-learning tools, provides an automated mechanism to deliver course content and track learning progress ( Dalsgaard, 2006 ). There are two types of LMS: open-source and closed-source. Open-source LMSs are generally free of charge and customisable based on the user preferences at a low cost ( Bansode and Kumbhar, 2012 , p. 415). Al-Ajlan (2012 , p. 193) outlined a list of features of an LMS, which may be considered as components of an LMS, as shown in Table 1 . We would expect different features (components) of an LMS which impacts students' perceptions when evaluating their UX of an LMS. We also expect students to focus more on learning tools, which are visible to them, rather than on supporting and technical tools (see Table 1 ).

Moodle (Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment) is an open-source LMS ( Poulova et al. , 2015 , p. 1303). Moodle-based e-learning programs can be used to enable teachers to enrich students' learning experiences ( Bansode and Kumbhar, 2012 ). Moodle’s first prototypes were created by Martin Dougimas in 1999 and Moodle 1.0 was released in August 2002. While there are many LMS solutions of e-learning in the global e-learning market ( Pappas, 2013 ), Moodle is one of the most widely used e-learning platform in higher education ( Machado and Tao, 2007 ; Teo et al. , 2019 ). Other popular LMSs are Blackboard Learn and Canvas, in addition to custom-made LMSs ( Kuran et al. , 2017 ). Sheshasaayee and Bee (2017) stated that Moodle helps to find optimal ways of learning and optimal learning results and plays a vital role in terms of measuring student's knowledge, skills, and disciplinary practices (p. 738). Moodle offers a relatively acceptable user-friendly interface and whiteboard feature allowing to present the learning content clearly. Moodle provides communication and collaboration features (including real-time chat, discussion and sharing of files) for students and teachers ( Cavus and Zabadi, 2014 ). Therefore, it deems appropriate to use Moodle to assess and evaluate students' perceptions of UX of LMS. However, while we acknowledge Moodle has communicative features facilitating distance learning, there are certain limitations in doing everything completely online, such as in teaching philosophy, which demands a more personal and dialogical communication and pedagogical issues ( Vrasidas, 2004 ).

Poulova et al. (2015) in a comparative analysis of Moodle with three other LMSs (Blackboard, Claroline, EKP) asserted that Moodle's features do not basically differ from Blackboard and EKP, other than being free of charge. However, there might be greater differences between LMSs in terms of their UX. Moodle's UX is significantly better than Schoology's UX in terms of attractiveness, dependability and novelty ( Sahid et al. , 2016 ). Moodle's UX is found significantly worse than UX of university's custom-made LMS iQualify in terms of usability, navigational features, content and overall, as iQualify was specifically designed to the needs of the institution where it was used ( Nichols, 2016 ). Teachers' perceived usefulness have affected the university students' usage frequency of Moodle ( Wang et al. , 2013 , p. 76). The authors also found a difference in the communication mechanism in teaching, potentially due to the differences in culture and students' background, affecting the frequency of the use of different features. We would consider Moodle's technological functionality not differing significantly from other popular LMSs. However, overall UX is very likely to differ across different LMSs and universities and/or cultures. We assume this effect is due to the inherently subjective nature of the UX, which is dependent not only on the more objective concepts of the technological functionality but also on the user's perceptions, cultural background and the context of usage. Literature has identified some other potential factors proven to impact the use of LMS, e-learning and the UX. Potential factors affecting e-learning are gender, age, the experience of use, culture, race, family income, religion, political activities and cognitive aspects ( Maldonado et al. , 2011 ). Moreover, e-learning acceptance may be influenced by the course major and study level ( Al-Gahtani, 2016 ). The language of the website interface could potentially affect the UX, according to how translatable the original text is into another language and preferred by the user ( Bowker, 2015 ). Exchange student status is related to the individuals' learning style preferences ( Holtbrügge and Mohr, 2010 ).

3. Theoretical framework

The holistic UX model is developed by Pallot et al. (2014) who view UX as a multidimensional and multi-faceted construct due to the many different types of use experiences, including social and emphatical. Each type of experience is then decomposed into elements and properties that allow evaluation of its perceived quality. In this research, we employed the UX model from Topolewski et al. (2019) , which is an adaptation of the Pallot et al. (2014) original UX model. Some researchers have quantitatively verified the reliability and validity of the model (e.g. Krawczyk et al. , 2017 ; Topolewski et al. , 2019 ). In the adapted model Topolewski et al. (2019) , the societal dimension is excluded from the model, hence UX properties were considered to stand for human, social and business dimensions. The human dimension presents emotional and cognitive factors, social dimension presents emphatical and interpersonal factors, and business dimension presents the economic and technological factors. The definitions of the UX properties used to develop the questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1 .

4. Methodology

4.1 research design.

The following decisions were made regarding the data collection. For qualitative data, several semi-structured interviews were planned and conducted. Nakamura et al. (2017a) stated that for usability and UX evaluation of LMSs, interviews are widely used research techniques. Moreover, for quantitative data, a short survey was developed and distributed among the potential respondents. Levin (2006) stated that cross-sectional studies are often used because they are relatively inexpensive, but still allow to estimate the prevalence of outcome of interest (pp. 24–25).

4.2 Data collection

As mentioned, we are interested in evaluating the university students' UX, given that this demographic group is highly relevant end-users of LMS to determine the process of e-learning in higher education institutions. Hence, we focus on attaining a sample of university students at any level. We employed a convenience sampling strategy as it allows to choose participants who are available and easily accessible. Al-Gahtani (2016) , in the study of e-learning acceptance and assimilation, considered the convenience sampling technique as appropriate for researching the topic. Hwang and Salvendy (2010) stated that for usability evaluation of software products, there should be 8 to 12 respondents at the minimum. In total, 28 students were invited to participate, and the final dataset comprises of 10 male and 10 female students, hence the response rate was 71.14%. The students ( N = 8) who rejected the invitation stated that they had busy schedule. However, the sample consisting of 20 participants is enough to perform qualitative analysis when testing users about the use of products ( Hwang and Salvendy, 2010 ).

We adopted the 24 questions developed by Topolewski et al. (2019) to collect both qualitative and quantitative data. The questions covered three main dimensions (business, human and social) of UX model with each dimension having two factors. The business dimension includes economic and technological factors, the human dimension includes emotional and cognitive factors, and the social dimension includes the emphatical and interpersonal factors. Of those 24 questions, 3 were used to evaluate students' intention to use LMS, particularly Moodle (see Appendix 1 ). In addition, we asked respondents to provide background information about their age, gender, length of using Moodle and/or other LMSs, and chosen Moodle's UI language. The data were collected between February and March 2020. The interview materials were then transcribed and imported to a Word document and were later analysed with qualitative analysis tool (NVivo). After data preparation, the researchers imported the data to the Nvivo, this allowed us to have a more nuanced data analysis (partially via the quantification of qualitative data). However, coding is not a substitute for deep and repeated immersion in the transcript data ( Campbell et al. , 2013 , p. 308), meaning researchers continually viewed original data transcripts. The recorded semi-structured interviews had an average length of 25 min; interviews lasted between 14 and 53 min.

For quantitative data, we asked the same respondents ( N = 20) to answer the same 24 questions using a Likert scale from 1 to 7, where 1 being “very unfulfilling with UX property” and 7 being “very fulfilling with UX property” (see Appendix 2 ). The data were transferred into Excel spreadsheet and were consequently descriptively analysed. We performed simple descriptive statistical analysis on the answers given by the respondents on the 24 questions. The descriptive analysis helped us to evaluate the variables that may affect the UX and to evaluate the reliability and validity of the study results.

5.1 Descriptive analysis

As shown in Table 2 , the average age of the participants was 23.4, ranging from 20 to 31 years old. One female student chose not to reveal her age. There were 17 students from Finland, 1 from Russia, 1 from Kazakhstan and 1 from Italy. Finnish students mentioned that they used Moodle also in Swedish (with the exception of one male). A Russian female stated she used Moodle in English or in Finnish, whereas Kazakh and Italian students stated they only used Moodle in English. With the exception of an Italian student, all the other 19 students were from one Finnish university. There were 11 bachelor's level students (six females and five males), and 9 master's level students (four females and five males). Academic majors of the students vary significantly. All students reported that they were somewhat experienced with the use of the LMS. The average use of Moodle was 3.5 years, ranging between three months and seven years. Some students ( N = 12) also had experience using other LMSs similar to Moodle with the average use of 1.35 years (six months to six years). In total, the combined average use of LMSs was 4.83 years. More descriptive information is provided in Appendix 2 .

Descriptive analysis of UX scores given by the respondents allowed us to find attributes that were considered as relatively important based on the means values. The most important attributes were (scores over 5): usefulness, pleasantness, productivity, reliability, efficiency, fulfilness, confidence, engagement, meaningfulness, respectfulness, as well as highly reported intentions to use. The highest value was given to question in relation to students' intention to use Moodle, “to which degree are you convinced of using Moodle in the near future” (Mean = 6.5). Some attributes of LMS (Moodle) such as user-friendliness, enjoyment, collaborativeness, comprehensiveness, communicativeness, attentiveness, helpfulness and responsiveness were evaluated as being good (scores between 4 and 5). The highest value was given to question in relation to the responsiveness of LMS (Moodle) system with the Mean = 4.91. At the same time, the descriptive results showed that there were some mildly low-rated elements (scores less than 4): entertaining, novelty, attractiveness. The highest value was given to question in relation to the attractiveness of LMS (Moodle) system with the Mean = 3.55. Standard deviation, a measure of how much variability there are in quantitative scores showed that standard deviation for most of the UX properties and intention to use was between 0.75 and 1.8–some elements having higher variability (e.g. Novelty) than others (e.g. Productivity).

5.2 Qualitative analysis

The qualitative data were analysed based on the holistic UX model developed by Topolewski et al. (2019) . Below, we provide detailed explanations of the interview data and elaborate on the findings according to the respondents' intention to use LMS (Moodle) system, and the three dimensions of UX model (the human dimension presenting [emotional and cognitive factors], social dimension presenting [emphatical and interpersonal factors] and business dimension presenting [economic and technological factors].

5.2.1 Economical

Regarding the effect of economic factors, the results showed that Moodle was perceived as useful and productive platform for learning, based on multiple perspectives. Moodle is useful because it provides an overview of the course together with all relevant course information provided by the teacher. Moodle helps with doing the assignments and with sending files to the teacher. Moodle is either informative or provides means for easy finding the information, the information was provided by ( N = 11) interviewees. One interviewee mentioned that “ Moodle could be slow, such as loading documents in a browser window, which could be improved.” Another interviewee mentioned that “ group work could be improved in Moodle by implementing some sort of a feature for group work.” As much as ten interviewees mentioned that Moodle is easy for navigating and using it, but for some, it is a hard platform to navigate and use, or that it gets easier to use over time of experience. For some, Moodle may be a pleasant platform ( N = 5), neutral ( N = 2), or unpleasant ( N = 1). One student cited very high productivity of Moodle “in the sense that it [Moodle] helps to monitor all tasks and assignments that I have to accomplish.” For many, Moodle is not entertaining. Moodle is perceived as a school app, and hence it does not have to be entertaining ( N = 8). This might be improved by implementing brighter and more entertaining colours in the user interface (UI), like the university's colours.

5.2.2 Technological

Regarding the effect of technological factors, the results showed Moodle is generally not novel for multiple reasons, although partial novelty may remain. One is that Moodle is used for a long time. Moodle could be novel at first ( N = 5) and it may not be novel if other LMSs were used before. There are either no problems in terms of reliability ( N = 9), or only minor problems, mostly related to technical issues: service breaks, such as server downtime or website's inaccessibility, login issues. For some, reliability depends on the teacher. Moodle is intuitive, easy to use and generally efficient for studies with structured content. Efficiency depends on how the teacher uses Moodle. Moodle helped in several ways with the school tasks and assignments: helping to submit the files to the teacher, to manage the time, to access the information needed for completing the tasks, to manage the percentage of the course completion and the calendar. The interviewees mentioned some issues concerning the information in Moodle: there are occasional problems with the courses in Moodle, like having trouble locating how to add new courses or to categorise and to find course content ( N = 7). This finding is consistent with ( Khan et al. , 2017 ) who also indicated that the informativeness of the course content in LMS is important factor to students experience of LMSs. Moodle's user-friendliness was mentioned with respect to the UX or the length of using Moodle, with the use of Moodle has become easier over time ( N = 6). User-friendliness can be improved by categorising information in Moodle, making the enrolment to courses feature easier, providing a feature to filter or categorise the courses according to the user's criteria, making a tutorial “how to use Moodle,” and making more interactive links.

5.2.3 Emotional

Regarding the effect of emotional factors, the results showed the attractiveness of Moodle can be evaluated as mostly neutral, boring and dull, but it does not have to be attractive. Simultaneously, attractiveness can be judged as clear, simple, minimalistic. It is enjoyable or neutral to use Moodle, but it is a study tool; hence, enjoyment is not essential. Some interviewees found Moodle as easy and simple to use. Having everything in one place improved enjoyment. Enjoyment can be improved by implementing a chat function or adding mediums of communication in the courses (e.g. providing Q&A). Enjoyment depends on the course (e.g. interactive content in the course). One of the interviewees mentioned that it is joyful to use Moodle because of its design. Another interviewee indicated that using a mobile version of Moodle meant going to YouTube to view study content videos, thus having to view advertisements, which is unpleasant. Moodle is quite good in terms of its fulfilment, but for some, it may be neutral or bad. Moodle's fulfilment is affected by the teacher and/or by the student's efforts. As much as ten interviewees mentioned that Moodle can help to improve grades. The reasons provided include, (1) information provided regarding the criteria for how the assignments will be evaluated and (2) having an easy place to access useful information or reading extra material.

5.2.4 Cognitive

Regarding the effect of cognitive factors, the results showed that the opinions can be divided into comprehensiveness and helpfulness of the Moodle, as half of the interviewees evaluated as good, and the other half evaluated as neutral or bad. According to one interviewee, roughly, 30% of courses are badly structured, 50% are fine and 20% are good. Many commented communication methods are discussion forums, in-person communication, emails, personal messages, Wiki, Q&A section. Discussion forums are helpful and can have exciting discussions that help with an understanding of content. However, discussion forums can have a feeling of a “fake” or “unreal” discussion and difficulties of communicating. Personal communication or emails were frequently preferred to Moodle, especially with teachers. Comprehensiveness provided by Moodle differs for communication with students and with teachers. Teacher's encouragement can improve comprehensiveness. Moodle is meaningful and engaging, although depending on the teacher, the course content and how simply and it is structured. The content (e.g. articles) is the main factor affecting the meaningfulness of Moodle. Viewing different types of visual content (images, videos) to reading text material was preferred by some interviewees. The interactivity of the content and having everything in one place was engaging and helping to plan studies and can have a forced engagement: being told by the teacher, or because a student “has to.” Also, some mentioned that deadlines for assignments can increase the engagement. The following features in Moodle were also mentioned to be engaging quizzes, easiness of downloading documents, final course evaluation survey and percentage bar of completing tasks.

5.2.5 Emphatical

Regarding the effect of emphatical factors, the results showed that the attentiveness and responsiveness were mostly evaluated as good or relatively high, but with certain issues. Email notifications about new content posts were commented by one as: “Sometimes you get emails that are relevant, sometimes you do not, and sometimes you get emails every time, and that is very annoying.” Some responded to the notifications because they had to, some said that they always respond and some who mentioned that they never respond. Some preferred not to respond to others altogether. Responsiveness features included discussion forums, grades and Wikis. Some interviewees mentioned the direct messaging or chat functions were not presented to them, for others, while these functions were present, but did not work. A mobile app can improve responsiveness. Moodle is mostly helpful, which differed when communicating with students or teachers, and it depends on the course and/or teacher. Help can be received through forums, but some preferred other platforms, like email. Overall, communication is respectful but formal and official, with occasional issues when arguing, understanding each other's point of view and timing discussions to complete assignments.

5.2.6 Interpersonal

Regarding the effect of interpersonal factors, the results showed that the communicativeness is quite neutral, and collaboration is mostly unfulfilling. For some, it is possible to communicate or collaborate, often noting discussion forums, but prefer to use other mediums. Communication with students and with teachers is different: communicating with teachers is more widespread, but even then, many were found to prefer communicating with teachers by email. Personal communication is occasionally preferred, often at the premises of the university, especially for group work, unless there is a lack of time, and then other platforms are used. Discussion forums were evaluated as “old-school,” too formal, and not authentic enough; stating facts rather than communicating in mandatory discussions, which is a worse UX than instant messaging. Four interviewees mentioned that Moodle is used to find contact information to contact in other platforms: WhatsApp, Google Drive or email. Confidence in communication on Moodle is very high, because of formal communication with a free expression of opinions. Confidence was higher if a course required a password to enrol. Some lack of confidence was mentioned too, e.g. when students were unsure when others would reply, hence causing issues with last-minute mandatory discussions.

5.2.7 Intention to use

Regarding the students' intention to use LMS and in particular Moodle, the results showed that Moodle will be necessarily used without choice throughout the studies, and not afterwards unless it is a part of work, due to the lack of motivation and ability to log in after graduation. Willingness to use Moodle differed across interviewees widely. For example, some mentioned that Moodle is fine to use as a utilitarian tool, but not as an entertaining platform, like YouTube, as the former requires active, instead of the passive information consumption. Moodle is often recommended as an LMS, although opinions differ, depending on the experience of usage of other LMSs. Moodle can be recommended because it is easy to use, all relevant information is placed conveniently in the same place, easy to send tasks to the teacher for evaluation, easy to receive information from the teacher. Less frequently was mentioned that Moodle has a clear structure, offers basic functionality, it is efficient to use, easy for teachers to administer Moodle. Some mentioned that in Moodle it is possible to monitor the studying process, Moodle facilitates studying and that the design is liked. However, some mentioned that they would not recommend Moodle because of weak elements like communication, including group communication, user-friendliness of Moodle, navigation and use hardness, course enrolment, layout and/or UI, discussion forums, usability issues. Only one interviewee mentioned lack of customisability of the front page, lack of mobile app and navigation of Moodle. Moodle can be improved by making the course list clearer, optimising “technical stuff,” providing access for non-enrolled students to audit courses and improving relevance of content post notifications.

6. Discussions

In this research, a mixed-method approach was used to evaluate the university students' perception of UX of LMS particularly their perceptions towards Moodle as a learning platform. To do so, we interviewed 20 university students to find answers for our research questions “ what factors impact the university students' perceptions of the UX of LMS ”? and “ what are the potential solutions to the challenges of the UX identified by the university students ”? The results showed that students considered Moodle to be an easy and intuitive study-related tool that facilitates the learning. For several students, Moodle was found to be helpful in relation to the engagement of students in their studies through several features, such as deadlines and a completion percentage of the course. The results showed that many features of Moodle were rarely used, e.g. Wikis, whereas some were more frequently used, e.g. discussion forums. Moodle was also found to be generally quite reliable, with only minor technical issues that almost did not cause any problems. Many students stated they had to use Moodle, although having no problem with that, some even underlined that they are very dependent on Moodle in their learning. Most students stated that Moodle has an easy to use and navigating user interface (UI), although some did not. Regarding the challenges of the UX (RQ 2), the UI of Moodle was characterised as neutral, pastel, somewhat dull and not attractive, although did not concern students much.

The analysis of the qualitative data (answers to RQ 1) showed that Moodle was mostly used by the students in order to retrieve the contact details or information about the course. However, many also outlined the usefulness of the feature to send tasks to the teachers. Some students stated that looking up information on Moodle was better than looking for the information in the libraries. There were a few students who have characterised their UX as very limited, using Moodle just to upload/send the tasks or download documents and lecture slides. Although Moodle was not considered novel, for most, it was not a problem, some even suggesting that novelty may have a negative correlation with the ease of use due to the lack of experience and skills of using Moodle. Moreover, Moodle was frequently discussed in the perspective of using it together with other people in the social context or group dynamics. The UX of Moodle depends on how teachers structure the course in many of the UX aspects. Furthermore, many found the communication over Moodle to be formal and goal-oriented, yet dry and hypocritical. Certain features helped with communicating over Moodle, although these were limited, and may have to be improved. Discussion forums feature was the most widely mentioned feature, which was characterised by many of the students as old-school, although with some potential use if it were improved to be more modern with the chat function and group communication. Furthermore, the use of communicating features of Moodle was found to be different if the communication was with teachers or with other students. To compensate for the lack of communicating and collaborative functionalities of Moodle, thus impacting the students' UX, many students referred to using other platforms: YouTube, email, Google Drive, WhatsApp and Facebook. Additionally, other platforms were mentioned as affecting the UX of Moodle; for example, notifications sent to emails help students to be more attentive. Some found the UX to be improved by other platforms, whereas some stated that the UX of Moodle to be negatively affected.

6.1 Theoretical contributions

The theory of a holistic UX is currently in the early stages of validation within different research contexts. So, it is important to underline that the definition and understanding of the holistic UX (that is, the UX is viewed with a full and comprehensive set of factors that affect UX) is still limited ( Tokkonen and Saariluoma, 2013 ; Van Schaik and Ling, 2008 ). By using a UX framework of Topolewski et al. (2019) , this paper theoretically contributes to the holistic UX of an LMS research by providing manifold insights about such learning platforms.

First, we theoretically contribute to holistic UX theory by evaluating the applicability of the holistic UX model. We found that the questions about the factors of the holistic UX model tend to elicit respondents' qualitative answers that are quite broad, which also encompass perceptions and experiences simultaneously about multiple features (or components) of an LMS as well as contextual factors. For example, emotional and cognitive factors tend to include students' comments that teacher's proficiency in organising course content may promote students' engagement in using LMS. Other web-systems (like YouTube or Outlook Email) were also frequently mentioned when evaluating UX. Furthermore, this calls for a question of trying to view the UX as not being strictly bounded to the UX product itself, but rather to the product, other products that are used in conjunction and the context simultaneously. The following factors were mentioned and seem to have affected the UX of an LMS: web-platforms (including UX of previously used LMSs), teachers' use of an LMS, contextual factors, organisational context and the use of an LMS by others.

Second, a holistic view of UX of the LMS in our study seems to go quite broad, encompassing not only the UX of the LMS (Moodle) itself, but also the whole context, hence UX of an LMS is reported to be dependent on a system consisting of other phenomena: Internet infrastructure, communal, cultural and organisational norms and boundaries, among other potential factors that may exist.

Third, this research by employing the holistic UX in the context of LMS found that the UX of Moodle as an LMS and its perception vary across students. Many students stated that their learning in the university is very dependent on the LMS, particularly in the programs where courses are predominantly online. However, the use of LMS was limited for some students, who claimed that they preferred traditional learning to e-learning over LMS. Generally, Moodle as an LMS is not viewed as an entertaining or joyful platform and should be considered different from a platform like YouTube. Social context and use by others are essential factors in the UX of LMS. However, communication features were found to be weakly satisfying. Our results show that UX of LMS was found to be clear and good enough as a studying tool, but not very attractive. Other platforms were found to impact the UX of LMS: YouTube, email, Google Drive, WhatsApp and Facebook. These platforms were either replacing, complimenting or compensating certain UX elements and features (components) of an LMS. Additionally, how teachers used LMS was considered to be among the most influential factors in the students' UX perceptions of LMS. Although we would expect these findings to be highly case- and context-dependent (due to the nature of studied phenomena), we also could make an argument that a similar study about students' holistic UX of LMS in other contexts may have similar findings. From a more theoretical standpoint, these findings could be used to guide further research into exploring specific parts of the UX of an LMS.

6.2 Practical implications

The second research question was, “ what are the potential solutions to the identified issues of the UX of the students? ” Many students were not aware of the existence of all Moodle's features. Sometimes even not aware of the features, which were proposed to be implemented in Moodle, like group chat function. While it can be argued that it is actually impossible to expect students to know all features, they could be informed by training programs or by popup windows in the UI, as proposed by one student. Several students suggested improving the content presented on Moodle by making it more interactive, engaging, and visually appealing. Some students outlined issues with navigation, mainly in the area of enrolling and navigating between courses. Students suggested improving the visual appeal of UI of Moodle by making UI more colourful while maintaining the already-present clearness and simplicity. However, UI was not found to be an essential priority, and thus it was suggested to spend resources to focus on improving other issues first. Many students suggested improving communication on Moodle by modernising discussion forum mechanisms, implementing private messages, chat function, group communication. Interestingly, many students stated that in principle, there are possibilities for proper communication over Moodle, but are not widely used. Therefore, it could be argued that the students' UX of LMS could potentially be enhanced, if the missing features and functionalities indicated are closely considered and added to the Moodle.

The students also pointed some interesting issues about the teachers' role, especially their role about communication over Moodle and the informativeness of the course content similar to Khan et al. (2017) findings. For example, it was suggested that teachers engage students in compelling, and engaging discussions. The students mentioned that teachers should provide alternatives to “state a fact” type of required discussion in course assignments, which were found to be boring and shallow. Some students stated that they liked using discussion forums if the discussion is personally relevant, for example, in their careers or personal interests. We also found that students appreciate the informativeness of content in LMS as this impact their experience with LMSs significantly. To overcome this issue, we advise teachers to facilitate a discussion over LMS that promotes students' career perspectives or answers to their interests. However, each situation is unique, and thus teachers are encouraged to look into methods to create more personally engaging discussions. It is strongly advised that universities consider issues over how to manage LMS in terms of published content, given that content is a significant element in the UX of LMS, and as such significantly impact students' e-learning.

Many students found that Moodle is just a “blank slate” tool from many of the UX properties' perspectives, with UX depending on how that tool is used. Additionally, many students stated that some teachers create course content that is more interesting than other teachers. Thus, it is highly proposed that special initiatives are taken to improve teachers' abilities to use LMS and to structure the content in an engaging way. In addition, Abusalim et al. (2020) argued that management and policymakers at the universities should focus on helping teachers shift to student-centred styles of pedagogies prior to making investments in IT infrastructure, indicating that investment in learning tools and IT alone does not necessarily improve the productivity. Based on the students' perception of LMS, it is advised to inform the teachers on their role as facilitators of the discussion over LMS, with many stating that teachers have the power to increase students' engagement in the discussions over the Moodle. An example of such an initiative could be organising training programs for the teachers, where they are taught how to structure the course content in a more engaging way. Another example could be to suggest the university administration to promote communities of practice of the teachers around using Moodle. Finally, we suggest universities to appoint dedicated personnel to maintain and improve the quality of content over Moodle through helping teachers structuring the content of their courses.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we took the perspective of the UX of LMSs, analysing the changes in students' perceptions towards e-learning solutions. We observe that many features of LMSs (in particular, Moodle) are important determinants and positively influence students' perceived learning outcome and the UX of LMSs.

We contribute to the literature by providing insights on how the UX of the LMS can be improved. The areas for improvement concern advanced feature of Moodle, UI of Moodle, communication over Moodle and the use of Moodle by the teachers. The latter two are considered to be more critical issues than the other. Designers of LMSs may pay more attention to the UI, communication features and compatibility of Moodle with other web-platforms and the learnability of Moodle by students. Teachers and administration of universities, in general, may be advised to take active, somewhat more centralised roles to manage the UX of LMS, given that this may have a detrimental impact on the e-learning of students. Even though many students commented that Moodle is user-friendly for the most part, navigating in the content between different courses were found challenging by some. Furthermore, the mobile version was found to be not very comfortable and compatible to work with, in addition to complaints regarding the mobile app of Moodle.

Moreover, we found that Moodle is not suitable for teaching philosophy completely online due to the lack of personal communication. Similar to Cavus and Zabadi (2014) who raised the importance of real-time synchronous discussion and chat function of Moodle, our findings also show that these features are very important determinants for the students. The findings show that the UX depends on how universities design and maintain Moodle. If Moodle is designed by experts and professionals, then the UX might be evaluated positively. If Moodle is designed by amateurs and maintained improperly (e.g. hosted on bad servers), then UX would suffer. Finally, this research contributes to the literature by proposing potential solutions to the problems identified in the UX of LMS (Moodle).

7.1 Limitations and future research

There are some limitations in this research. First, we have done our best to collect, document and analyse the data as carefully as possible. However, it is possible that not all issues of UX of LMSs were found. Second, the research context should be considered as a potential source of bias for the collected data and the findings. The data findings may not be directly extrapolated to other Moodle versions, LMSs or universities. Finally, the sampling technique could be an issue too. There are some recommendations and suggestions for future research. Future research may want to utilise a different methodology to explore the same issue. Future studies may attempt at refining the methodology that aims to elicit improvement of the UX of an LMS. A research dedicated to analysing the potential gender difference in evaluating the UX may be proposed. Some UX properties were more important (like helpfulness) than others (attractiveness), suggesting a need to evaluate in future studies, the priority of UX elements to focus on in future LMS development.

Features (components) of LMS

Descriptive statistics of the quantitative responses

Entertaining - Degree to which Moodle entertains users.

Pleasantness - Degree to which Moodle is pleasant to use.

Productivity - Degree to which Moodle helps users to be more productive.

Usefulness - Degree to which Moodle allows users to carry out tasks.

Novelty - Degree to which Moodle is new to the user.

Efficiency - Degree to which Moodle allows users to be efficient.

Reliability - Degree to which Moodle is reliable.

User - Friendliness - Degree to which Moodle is easy-to-use and intuitive enough.

Attractiveness - Degree to which Moodle is visually attractive.

Enjoyment - Degree to which Moodle is enjoyable.

Fulfilment - Degree to which Moodle allows users to achieve properly a task.

Comprehensiveness - Degree to which Moodle allows users to understand others.

Engagement - Degree to which Moodle allows users to engage in their tasks.

Meaningfulness - Degree to which Moodle allows users to provide meaningful results.

Attentiveness - Degree to which Moodle allows users to be attentive to others.

Helpfulness , - Degree to which Moodle allows users to help others.

Respectful - Degree to which Moodle allows users to be respectful of others.

Responsiveness - Degree to which Moodle allows users to be responsive to others.

Collaborativeness - Degree to which Moodle allows users to collaborate with others.

Communicative - Degree to which Moodle allows users to communicate to others.

Confidence - Degree to which Moodle allows users to trust others.

Convincingness - Degree to which users are convinced of using Moodle in the near future.

Willingness - Degree to which users are willing to re-use Moodle.

Recommend - Degree to which users are willing to recommend using Moodle in other universities.

Abras , C. , Maloney-Krichmar , D. and Preece , J. ( 2004 ), User-centred Design. Bainbridge, W. Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction , Sage Publications , Thousand Oaks .

Abusalim , N. , Rayyan , M. , Jarrah , M. and Sharab , M. ( 2020 ), “ Institutional adoption of blended learning on a budget ”, International Journal of Educational Management , Vol. 34 No. 7 , pp. 1203 - 1220 , doi: 10.1108/IJEM-08-2019-0326 .

Al-Ajlan , A.S. ( 2012 ), “ A comparative study between e-learning features ”, Methodologies, Tools and New Developments for E-Learning , InTech Open Access , New York , pp. 191 - 214 , available at: http://cdn.intechweb.org/pdfs/27926.pdf .

Al-Gahtani , S.S. ( 2016 ), “ Empirical investigation of e-learning acceptance and assimilation: a structural equation model ”, Applied Computing and Informatics , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 27 - 50 .

Ardito , C. , Buono , P. , Caivano , D. , Costabile , M.F. and Lanzilotti , R. ( 2014 ), “ Investigating and promoting UX practice in industry: an experimental study ”, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies , Vol. 72 No. 6 , pp. 542 - 551 .

Bansode , S.Y. and Kumbhar , R. ( 2012 ), “ E-learning experience using open-source software: Moodle ”, DESIDOC Journal of Library and Information Technology , Vol. 32 No. 5 , pp. 409 - 416 .

Benigno , V. and Trentin , G. ( 2000 ), “ The evaluation of online courses ”, Journal of Computer Assisted Learning , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 259 - 270 .

Bevan , N. ( 2008 ), “ Classifying and selecting UX and usability measures ”, International Workshop on Meaningful Measures: Valid Useful UX Measurement , Vol. 11 , pp. 13 - 18 .

Bevan , N. ( 2009 ), “ What is the difference between the purpose of usability and UX evaluation methods? ”, Proceedings of the Workshop UXEM , Vol. 9 , pp. 1 - 4 .

Bowker , L. ( 2015 ), “ Translatability and UX: compatible or in conflict? Localisation focus ”, The International Journal of Localisation , Vol. 14 No. 2 , pp. 15 - 27 .

Brusilovsky , P. ( 2003 ), “ A distributed architecture for adaptive and intelligent LMSs ”, Workshop ‘Towards Intelligent LMSs,’ 11th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education .

Butt , R. , Siddiqui , H. , Soomro , R.A. and Asad , M.M. ( 2020 ), “ Integration of industrial revolution 4.0 and IOTs in academia: a state-of-the-art review on the concept of Education 4.0 in Pakistan ”, Interactive Technology and Smart Education , Vol. 17 No. 4 , pp. 337 - 354 .

Campbell , J.L. , Quincy , C. , Osserman , J. and Pedersen , O.K. ( 2013 ), “ Coding in-depth semi-structured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement ”, Sociological Methods and Research , Vol. 42 No. 3 , pp. 294 - 320 .

Cavus , N. and Zabadi , T. ( 2014 ), “ A comparison of open-source LMSs ”, Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences , Vol. 143 , pp. 521 - 526 .

Dalsgaard , C. ( 2006 ), “ Social software: E-learning beyond LMSs ”, European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning , Vol. 9 No. 2 , pp. 1 - 7 .

Davis , F.D. ( 1989 ), “ Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology ”, MIS Quarterly , Vol. 13 No. 3 , pp. 319 - 340 .

De Carvalho , A.F.P. and Silva , J.C.A. ( 2008 ), “ The importance of usability criteria on LMSs: lessons learned ”, ICEIS No. 5 , pp. 154 - 159 .

Detweiler , M. ( 2007 ), “ Managing UCD within agile projects ”, Interactions , Vol. 14 No. 3 , pp. 40 - 42 .

Dogoriti , E. , Pange , J. , Anderson , S. and G. ( 2014 ), “ The use of social networking and LMSs in English language teaching in higher education ”, Campus-Wide Information Systems , Vol. 31 No. 4 , pp. 254 - 263 , doi: 10.1108/CWIS-11-2013-0062 .

Fenko , A. , Schifferstein , H.N. and Hekkert , P. ( 2010 ), “ Shifts in sensory dominance between various stages of user–product interactions ”, Applied Ergonomics , Vol. 41 No. 1 , pp. 34 - 40 .

Fleming , J. , Becker , K. and Newton , C. ( 2017 ), “ Factors for successful e-learning: does age matter? ”, Education+ Training , Vol. 59 No. 1 , pp. 76 - 89 .

Garrison , D.R. and Anderson , T. ( 2003 ), E-learning in the 21st Century: A Framework for Research and Practice , Routledge Falmer , London .

Hassenzahl , M. and Tractinsky , N. ( 2006 ), “ UX-a research agenda ”, Behaviour and Information Technology , Vol. 25 No. 2 , pp. 91 - 97 .

Holtbrügge , D. and Mohr , A.T. ( 2010 ), “ Cultural determinants of learning style preferences ”, Academy of Management Learning and Education , Vol. 9 No. 4 , pp. 622 - 637 .

Hornbæk , K. and Hertzum , M. ( 2017 ), “ Technology acceptance and UX: a review of the experiential component in HCI ”, ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) , Vol. 24 No. 5 , pp. 1 - 30 .

Hwang , W. and Salvendy , G. ( 2010 ), “ Number of people required for usability evaluation: the 10±2 rule ”, Communications of the ACM , Vol. 53 No. 3 , pp. 130 - 133 .

Jeong , H.Y. ( 2016 ), “ UX based adaptive e-learning hypermedia system (U-AEHS): an integrative user model approach ”, Multimedia Tools and Applications , Vol. 75 No. 21 , pp. 13193 - 13209 .

Khan , B.H. ( 2004 ), “ The people—process—product continuum in E-learning: the E-learning P3 model ”, Educational Technology , Vol. 44 No. 5 , pp. 33 - 40 .

Khan , I.U. , Hameed , Z. , Yu , Y. and Khan , S.U. ( 2017 ), “ Assessing the determinants of flow experience in the adoption of LMSs: the moderating role of perceived institutional support ”, Behaviour and Information Technology , Vol. 36 No. 11 , pp. 1162 - 1176 .

Krawczyk , P. , Topolewski , M. and Pallot , M. ( 2017 ), “ Towards a reliable and valid mixed methods instrument in UX studies ”, 2017 International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC) , IEEE , pp. 1455 - 1464 .

Krishnamurthy , A. and O'Connor , R.V. ( 2013 ), “ An analysis of the software development processes of open-source e-learning systems ”, European Conference on Software Process Improvement , Springer , Berlin, Heidelberg , pp. 60 - 71 .

Kuran , M.Ş. , Pedersen , J.M. and Elsner , R. ( 2017 ), “ LMSs on blended learning courses: an experience-based observation ”, International Conference on Image Processing and Communications , Springer , Cham , pp. 141 - 148 .

Laguna Flores , J. ( 2019 ), Determining the UX Level of Operating Computer Systems in the Central Bank of Mexico , Doctoral Dissertation , Massachusetts Institute of Technology , Cambridge, MA .

Law , E. , Hvannberg , E. and Cockton , G. ( 2008 ), “ Maturing usability: quality in software, interaction and value ”, Human-Computer Interaction Series , Springer-Verlag , Berlin .

Law , E.L.C. , Roto , V. , Hassenzahl , M. , Vermeeren , A.P. and Kort , J. ( 2009 ), “ Understanding, scoping and defining UX: a survey approach ”, Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems , ACM , pp. 719 - 728 .

Law , E.L.C. , Van Schaik , P. and Roto , V. ( 2014 ), “ Attitudes towards UX (UX) measurement ”, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies , Vol. 72 No. 2 , pp. 526 - 541 .

Levin , K.A. ( 2006 ), “ Study design III: cross-sectional studies ”, Evidence-Based Dentistry , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 24 - 25 .

Lisnani , L. and Putri , R.I.I. ( 2020 ), “ Designing Moodle features as e-learning for learning mathematics in COVID-19 pandemic ”, Journal of Physics: Conference Series , IOP Publishing , Vol. 1657 No 1 , p. 012024 .

Machado , M. and Tao , E. ( 2007 ), “ Blackboard vs Moodle: comparing UX of LMSs ”, 37th Annual Frontiers in Education Conference-Global Engineering: Knowledge Without Borders, Opportunities Without Passports , IEEE , pp. S4J - 7 .

Maldonado , U.P.T. , Khan , G.F. , Moon , J. and Rho , J.J. ( 2011 ), “ “E‐learning motivation and educational portal acceptance in developing countries” ”, Online Information Review , Vol. 35 No. 1 , pp. 66 - 85 .

Nakamura , W.T. , de Oliveira , E.H.T. and Conte , T. ( 2017a ), “ Usability and UX evaluation of LMSs ”, Proceeding of the 19th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems , Vol. 3 , pp. 97 - 108 .

Nakamura , W. , Marques , L. , Rivero , L. , Oliveira , E. and Conte , T. ( 2017b ), “ Are generic UX evaluation techniques enough? A study on the UX evaluation of the edmodo LMS ”, Brazilian Symposium on Computers in Education (Simpósio Brasileiro de Informática na Educação-SBIE) , Vol. 28 No. 1 , p. 1007 .

Nakamura , W.T. , Marques , L.C. , Rivero , L. , de Oliveira , E.H. and Conte , T. ( 2019 ), “ Are scale-based techniques enough for learners to convey their UX when using a LMS? ”, Revista Brasileira de Informática na Educação , Vol. 27 No. 01 , pp. 104 - 131 .

Nichols , M. ( 2016 ), “ A comparison of two online learning systems ”, Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 19 - 32 .

Norman , D. ( 1999 ), Invisible Computer: Why Good Products Can Fail, the Personal Computer Is So Complex and Information Appliances Are the Solution , MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Onofrei , G. and Ferry , P. ( 2020 ), “ Reusable learning objects: a blended learning tool in teaching computer-aided design to engineering undergraduates ”, International Journal of Educational Management , Vol. 34 No. 10 , pp. 1559 - 1575 , doi: 10.1108/IJEM-12-2019-0418 .

Pallot , M. , Kalverkamp , M. , Vicini , S. , Trousse , B. , Vilmos , A. , Furdik , K. and Nikolov , R. ( 2014 ), “ An experiential design process and holistic model of UX for supporting user Co-creation ”, Open Innovation Yearbook .

Pappas , C.H. ( 2013 ), “ What are the most important features in a LMS? eLearning Industry ”, available at: http://elearningindustry.com/learning-management-systems-comparison-checklist-of-features .

Poulova , P. , Simonova , I. and Manenova , M. ( 2015 ), “ Which one, or another? Comparative analysis of selected LMS ”, Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences , Vol. 186 , pp. 302 - 1308 .

Rogers , Y. , Sharp , H. , Preece , J. and Tepper , M. ( 2007 ), “ Interaction design: beyond human-computer interaction”, netWorker: craft Netw ”, Computer , Vol. 11 No. 4 , p. 34 .

Sahid , D.S.S. , Santosa , P.I. , Ferdiana , R. and Lukito , E.N. ( 2016 ), “ Evaluation and measurement of LMS based on UX ”, 2016 6th International Annual Engineering Seminar (InAES) , IEEE , pp. 72 - 77 .

Sanders , E.B.N. and Stappers , P.J. ( 2008 ), “ Co-creation and the new landscapes of design ”, Co-design , Vol. 41 No. 1 , pp. 5 - 18 .

Shaltoni , A.M. , Khraim , H. , Abuhamad , A. and Amer , M. ( 2015 ), “ Exploring students' satisfaction with universities' portals in developing countries: a cultural perspective ”, International Journal of Information and Learning Technology , Vol. 32 No. 2 , pp. 82 - 93 , doi: 10.1108/IJILT-12-2012-0042 .

Sheshasaayee , A. and Bee , M.N. ( 2017 ), “ Evaluating UX in Moodle LMSs ”, 2017 International Conference on Innovative Mechanisms for Industry Applications (ICIMIA) , IEEE , pp. 735 - 738 .

Sun , P.C. , Tsai , R.J. , Finger , G. , Chen , Y.Y. and Yeh , D. ( 2008 ), “ What drives a successful e-Learning? An empirical investigation of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction ”, Computers and Education , Vol. 50 No. 4 , pp. 1183 - 1202 .

Sward , D. ( 2006 ), “ Gaining a competitive advantage through UX design ”, available at: http://www.intel.com/it/pdf/comp-adv-user-exp.pdf .

Teo , T. , Zhou , M. , Fan , A.C.W. and Huang , F. ( 2019 ), “ Factors that influence university students' intention to use Moodle: a study in Macau ”, Educational Technology Research and Development , Vol. 67 No. 3 , pp. 749 - 766 .

Tokkonen , H. and Saariluoma , P. ( 2013 ), “ How UX is understood? ”, 2013 Science and Information Conference , IEEE , pp. 791 - 795 .

Topolewski , M. , Lehtosaari , H. , Krawczyk , P. , Pallot , M. , Maslov , I. and Huotari , J. ( 2019 ), “ Validating a UX model through a formative approach: an empirical study ”, 2019 IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC) , IEEE , pp. 1 - 7 .

Uppal , M.A. , Ali , S. and Gulliver , S.R. ( 2018 ), “ Factors determining e‐learning service quality ”, British Journal of Educational Technology , Vol. 49 No. 3 , pp. 412 - 426 .

Van Schaik , P. and Ling , J. ( 2008 ), “ Modelling UX with web sites: usability, hedonic value, beauty and goodness ”, Interacting with Computers , Vol. 20 No. 3 , pp. 419 - 432 .

Vermeeren , A.P. , Law , E.L.C. , Roto , V. , Obrist , M. , Hoonhout , J. and Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila , K. ( 2010 ), “ UX evaluation methods: current state and development needs ”, Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Extending Boundaries , pp. 521 - 530 .

Vrasidas , C. ( 2004 ), “ Issues of pedagogy and design in e-learning systems ”, Proceedings of the 2004 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing , pp. 911 - 915 .

Wang , Y.H. , Tseng , Y.H. and Chang , C.C. ( 2013 ), “ Comparison of students' perception of Moodle in a Taiwan university against students in a Portuguese university ”, International Conference on Web-Based Learning , Springer , Berlin, Heidelberg , pp. 71 - 78 .

Zaharias , P. and Pappas , C. ( 2016 ), “ Quality management of LMSs: a UX perspective ”, Current Issues in Emerging eLearning , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 58 - 64 .

Zanjani , N. ( 2017 ), “ The important elements of LMS design that affect user engagement with e-learning tools within LMSs in the higher education sector ”, Australasian Journal of Educational Technology , Vol. 33 No. 1 , pp. 19 - 31 .

Zhang , D. , Zhao , J.L. , Zhou , L. and Nunamaker , J.F. Jr ( 2004 ), “ Can e-learning replace classroom learning? ”, Communications of the ACM , Vol. 47 No. 5 , pp. 75 - 79 .

Corresponding author

Related articles, all feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

An Overview of the Common Elements of Learning Management System Policies in Higher Education Institutions

Darren turnbull, ritesh chugh.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2022 Jun 14; Issue date 2022.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

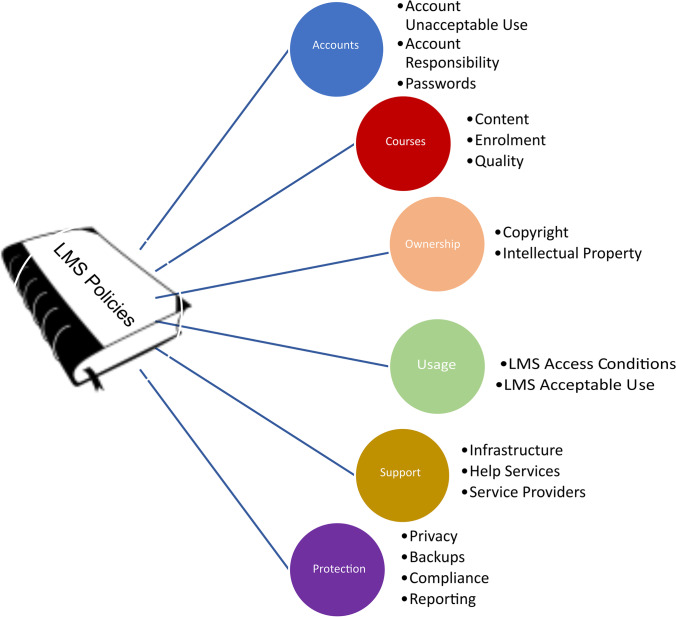

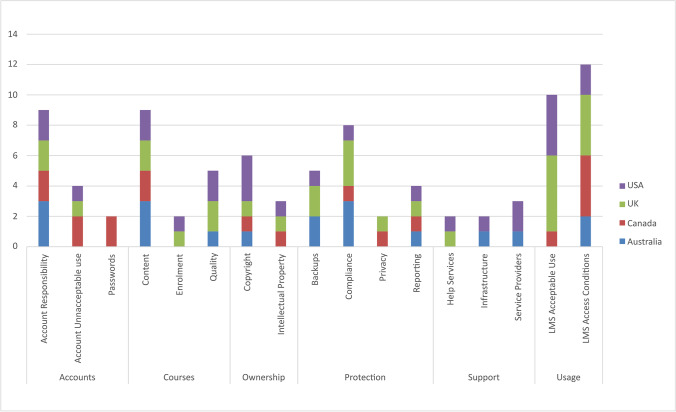

Learning management systems form an integral part of the learning environments of most universities and support a wide range of diverse activities and operations. However, learning management systems are often regulated by institutional policies that address the general use of Information Technology and Communication services rather than specific learning management system policies. Hence, we propose that learning management system environments are complex techno-social systems that require dedicated standalone policies to regulate their operation. This preliminary study examined a selection of learning management system policies from twenty universities in four countries to identify some of the elements that are considered necessary for inclusion in policy documents. Seventeen individual elements of learning management system policy documents were identified from a synthesis of the policies. These were classified into six policy categories: Accounts, Courses, Ownership, Support, Usage, and Protection. The study also identified three additional qualities of learning management system policy documents: standalone comprehensibility, platform-neutral statements, and contemporary relevance. The findings of this study will serve as a useful template for developing dedicated standalone policies for the governance of university learning management systems.

Keywords: Learning management system, LMS policy, Virtual learning environment, Online learning policy, University digital policy

Introduction

Learning management systems (LMS) are online software systems used to support various instructional, learning and assessment activities, and are central elements of many university course delivery systems (Turnbull et al., 2021 ; Weaver et al., 2008 ; Yueh & Hsu, 2008 ). The management and administration of LMSs is usually a centralized function in universities and other higher education institutions. Like other critical aspects of university operations, the effective administration of institutional LMSs depends on creating and communicating effective policies governing their use (Naveh et al., 2010 ). However, many universities do not have explicit policies dedicated to defining the parameters of LMS operations, such as acceptable codes of conduct for users engaging with these systems (Mohammadi et al., 2021 ). Instead, many institutions rely on generic policies covering Information Technology and Communication infrastructure. These policies do not necessarily cater to the LMS environment's unique characteristics as a complex, interrelated social system that technology-focused, infrastructure-heavy regulations cannot efficiently govern. Hence, there is a need for the development of dedicated LMS policies that not only address the technological environment of LMS platforms but also consider the human factors associated with people-to-people exchanges within this environment. This paper examines a cross-section of twenty LMS policies in universities from four countries with the aim of discovering some of the contemporary elements of policy development that emphasize the unique nature of LMS environments. In essence, this preliminary study is a snapshot of a cross-section of LMS policies in some of the world’s prominent higher education institutions.

The function of policy in an organization is to formally promulgate standard approaches to managing essential issues for its diverse stakeholders. A policy document is the tangible manifestation of rules and protocols that convey specific messages to various parties (von Solms & von Solms, 2004 ). A policy can best be understood in the context of the institutions and social relationships that give them purpose (Mosse, 2004 ). However, policy formation processes in organizations are often criticized because they lack consultative approaches that adequately consider the interests of the intended recipients of policy documents. Moreover, effective policies should recognize the changing and uncertain characteristics of the phenomena they address and be sufficiently malleable to accommodate substantial change. For universities that often exist and thrive in a perpetual state of flux, particular care must be taken to ensure that policy documents can survive technological and pedagogical upheavals that may impact their communities. The advent of COVID-19 has laid bare the necessity for universities to develop contingency plans to deal with major operational disrupters such as global pandemics (Rodrigues et al., 2020 ). LMS technology, associated pedagogical practices, and instructional design are proving to be critical elements in adapting to the post-COVID learning and teaching landscape. A key question that merits attention is whether the policies that drive the administration and operation of LMSs are up to this challenge?