If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 4

- The election of 1800

- Jefferson's presidency and the turn of the nineteenth century

The Louisiana Purchase and its exploration

- Jefferson's election and presidency

- The War of 1812

- The Monroe Doctrine

- The presidency of John Quincy Adams

- Politics and regional interests

- The Market Revolution - textile mills and the cotton gin

- The Market Revolution - communication and transportation

- The Market Revolution - impact and significance

- Irish and German immigration

- The 1820s and the Market Revolution

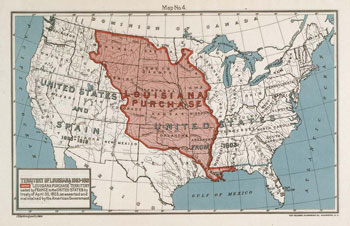

- The Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States, reshaping the environmental and economic makeup of the country.

- Jefferson confronted questions of presidential authority in deciding whether or not to acquire the territory, since the US Constitution does not explicitly give the president the power to purchase territory.

- Jefferson enlisted Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the new uncharted territory and secured Congressional funding for their expedition.

The Louisiana Purchase

Lewis and clark's expedition, environmental impacts, what do you think.

- Gaye Wilson. "Louisiana Purchase," The Jefferson Monticello . Last modified 2003, accessed June 21, 2017. https://www.monticello.org/site/jefferson/louisiana-purchase .

- National Geographic Staff. "Lewis and Clark Expedition Discoveries and Tribes Encountered." Accessed June 21, 2017. http://www.nationalgeographic.com/lewisandclark/resources_discoveries_plant.html

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

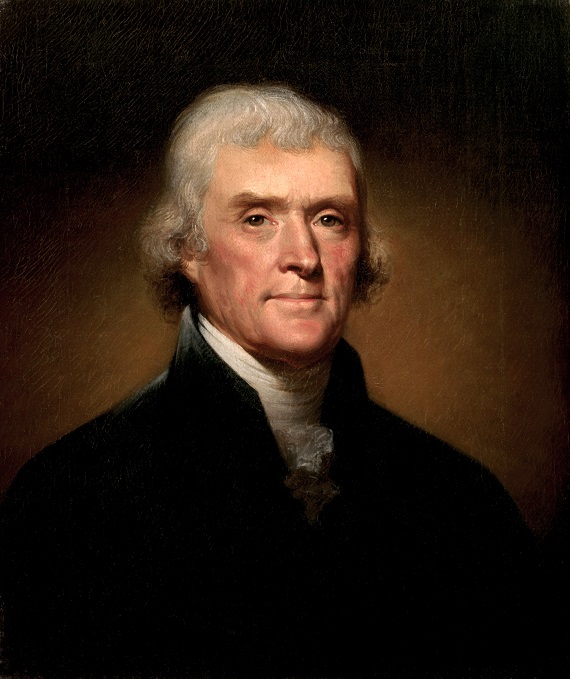

How the Louisiana Purchase Changed the World

When Thomas Jefferson purchased the Louisiana Territory from France, he altered the shape of a nation and the course of history

Joseph A. Harriss

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Louisiana-Purchase-Thomas-Jefferson-631.jpg)

UNDERSTANDABLY, Pierre Clément de Laussat was saddened by this unexpected turn of events. Having arrived in New Orleans from Paris with his wife and three daughters just nine months earlier, in March 1803, the cultivated, worldly French functionary had expected to reign for six or eight years as colonial prefect over the vast territory of Louisiana, which was to be France’s North American empire. The prospect had been all the more pleasing because the territory’s capital, New Orleans, he had noted with approval, was a city with “a great deal of social life, elegance and goodbreeding.” He also had liked the fact that the city had “all sorts of masters—dancing, music, art, and fencing,” and that even though there were “no book shops or libraries,” books could be ordered from France.

But almost before Laussat had learned to appreciate a good gumbo and the relaxed Creole pace of life, Napoléon Bonaparte had abruptly decided to sell the territory to the United States. This left Laussat with little to do but officiate when, on a sunny December 20, 1803, the French tricolor was slowly lowered in New Orleans’ main square, the Placed’Armes, and the American flag was raised. After William C.C. Claiborne and Gen. James Wilkinson, the new commissioners of the territory, officially took possession of it in the name of the United States, assuring all residents that their property, rights and religion would be respected, celebratory salvos boomed from the forts around the city. Americans cried “Huzzah!” and waved their hats, while French and Spanish residents sulked in glum silence. Laussat, standing on the balcony of the town hall, burst into tears.

The Louisiana Purchase, made 200 years ago this month, nearly doubled the size of the United States. By any measure, it was one of the most colossal land transactions in history, involving an area larger than today’s France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Holland, Switzerland and the British Isles combined. All or parts of 15 Western states would eventually be carved from its nearly 830,000 square miles, which stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, and from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. And the price, $15 million, or about four cents an acre, was a breathtaking bargain. “Let the Land rejoice,” Gen. Horatio Gates, a prominent New York state legislator, told President Thomas Jefferson when details of the deal reached Washington, D.C. “For you have bought Louisiana for a song.”

Rich in gold, silver and other ores, as well as huge forests and endless lands for grazing and farming, the new acquisition would make America immensely wealthy. Or, as Jefferson put it in his usual understated way, “The fertility of thecountry, its climate and extent, promise in due season importantaids to our treasury, an ample provision for our posterity, and a wide-spread field for the blessings of freedom.”

American historians today are more outspoken in their enthusiasm for the acquisition. “With the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, this is one of the threethings that created the modern United States,” says Douglas Brinkley, director of the Eisenhower Center for American Studies in New Orleans and coauthor with the late Stephen E. Ambrose of The Mississippi and the Making of a Nation . Charles A. Cerami, author of Jefferson’s Great Gamble, agrees. “If we had not made this purchase, it would have pinched off the possibility of our becoming a continental power,” he says. “That, in turn, would have meant our ideas on freedom and democracy would have carried less weight with the rest of the world. This was the key to our international influence.”

The bicentennial is being celebrated with yearlong activities in many of the states fashioned from the territory. But the focal point of the celebrations is Louisiana itself. The most ambitious event opens this month at the New Orleans Museum of Art. “Jefferson’s America & Napoléon’s France” (April 12-August 31), an unprecedented exhibition of paintings, sculptures, decorative arts, memorabilia and rare documents, presents a dazzling look at the arts and leading figures of the two countries at this pivotal time in history. “What we wanted to do was enrich people’s understanding of the significance of this moment,” says Gail Feigenbaum, lead curator of the show. “It’s about more than just a humdinger of a real estate deal. What kind of world were Jefferson and Napoléon living and working in? We also show that our political and cultural relationship with France was extraordinarily rich at the time, a spirited interchange that altered the shape of the modern world.”

The “Louisiana territory” was born on April 9, 1682, when the French explorer Robert Cavelier, Sieur (Lord) de La Salle, erected a cross and column near the mouth of the Mississippi and solemnly read a declaration to a group of bemused Indians. He took possession of the whole Mississippi River basin, he avowed, in the name of “the most high, mighty, invincible and victorious Prince, Louis the Great, by Grace of God king of France and Navarre, 14th of that name.” And it was in honor of Louis XIV that he named the land Louisiana.

In 1718, French explorer Jean-Baptiste le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, founded a settlement near the site of La Salle’s proclamation, and named it la Nouvelle Orléans for Philippe, Duke of Orléans and Regent of France. By the time of the Louisiana Purchase, its population of whites, slaves of African origin and “free persons of color” was about 8,000. A picturesque assemblage of French and Spanish colonial architecture and Creole cottages, New Orleans boasted a thriving economy based largely on agricultural exports.

For more than a century after La Salle took possession of it, the Louisiana Territory, with its scattered French, Spanish, Acadian and German settlements, along with those of Native Americans and American-born frontiersmen, was traded among European royalty at their whim. The French were fascinated by America—which they often symbolized in paintings and drawings as a befeathered Noble Savage standing beside an alligator—but they could not decide whether it was a new Eden or, as the naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon declared, a primitive place fit only for degenerate life-forms. But the official view was summed up by Antoine de La Mothe Cadillac, whom Louis XIV named governor of the territory in 1710: “The people are aheap of the dregs of Canada,” he sniffed in a 42-page report to the king written soon after he arrived. The soldiers there were untrained and undisciplined, he lamented, and the whole colony was “not worth a straw at the present time.” Concluding that the area was valueless, Louis XV gave the territory to his Bourbon cousin Charles III of Spain in 1763. But in 1800, the region again changed hands, when Napoléon negotiated the clandestine Treaty of San Ildefonso with Spain’s Charles IV. The treaty called for the return of the vast territory to France in exchange for the small kingdom of Etruria in northern Italy, which Charles wanted for his daughter Louisetta.

When Jefferson heard rumors of Napoléon’s secret deal, he immediately saw the threat to America’s Western settlements and its vital outlet to the Gulf of Mexico. If the deal was allowed to stand, he declared, “it would be impossible that France and the United States can continue long as friends.” Relations had been relaxed with Spain while it held New Orleans, but Jefferson suspected that Napoléon wanted to close the Mississippi to American use. This must have been a wrenching moment for Jefferson, who had long been a Francophile. Twelve years before, he had returned from a five-year stint as American minister to Paris, shipping home 86 cases of furnishings and books he had picked up there.

The crunch came for Jefferson in October 1802. Spain’s King Charles IV finally got around to signing the royal decree officially transferring the territory to France, and on October 16, the Spanish administrator in New Orleans, Juan Ventura Morales, who had agreed to administer the colony until his French replacement, Laussat, could arrive, arbitrarily ended the American right to deposit cargo in the city duty-free. He argued that the three-year term of the 1795 treaty that had granted America this right and free passage through Spanish territory on the Mississippi had expired. Morales’ proclamation meant that American merchandise could no longer be stored in New Orleans warehouses. As a result, trappers’ pelts, agricultural produce and finished goods risked exposure and theft on open wharfs while awaiting shipment to the East Coast and beyond. The entire economy of America’s Western territories was in jeopardy. “The difficulties and risks . . . are incalculable,” warned the U.S. vice-consul in New Orleans, Williams E. Hulings, in a dispatch to Secretary of State James Madison.

As Jefferson had written in April 1802 to the U.S. minister in Paris, Robert R. Livingston, it was crucial that the port of New Orleans remain open and free for American commerce, particularly the goods coming down the Mississippi River. “There is on the globe one single spot,” Jefferson wrote, “the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market.” Jefferson’s concern was more than commercial. “He had a vision of America as an empire of liberty,” says Douglas Brinkley. “And he saw the Mississippi River not as the western edge of the country, but as the great spine that would hold the continent together.”

As it was, frontiersmen, infuriated by the abrogation of the right of deposit of their goods, threatened to seize New Orleans by force. The idea was taken up by lawmakers such as Senator James Ross of Pennsylvania, who drafted a resolution calling on Jefferson to form a 50,000-man army to take the city. The press joined the fray. The United States had the right, thundered the New York Evening Post, “to regulate the future destiny of North America,” while the Charleston Courier advocated “taking possession of the port . . . by force of arms.” As Secretary of State James Madison explained, “The Mississippi is to them everything. It is the Hudson, the Delaware, the Potomac, and all the navigable rivers of the Atlantic States, formed into one stream.”

With Congress and a vociferous press calling for action, Jefferson faced the nation’s most serious crisis since the American Revolution. “Peace is our passion,” he declared, and expressed the concern that hotheaded members of the opposition Federalist Party might “force us into war.” He had already instructed Livingston in early 1802 to approach Napoléon’s foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, to try to prevent the cession of the territory to France, if this had not already occurred, or, if the deal was done, to try to purchase New Orleans. In his initial meeting with Napoléon after taking up his Paris post in 1801, Livingston had been warned about Old World ways. “You have come to a very corrupt world,” Napoléon told him frankly, adding roguishly that Talleyrand was the right man to explain what he meant by corruption.

A wily political survivor who held high offices under the French Revolution, and later under Napoléon’s empire and the restored Bourbon monarchy, Talleyrand had spent the years 1792 to 1794 in exile in America after being denounced by the revolutionary National Convention, and had conceived a virulent contempt for Americans. “Refinement,” he declared, “does not exist” in the United States. As Napoléon’s foreign minister, Talleyrand customarily demanded outrageous bribes for diplomatic results. Despite a clubfoot and what contemporaries called his “dead eyes,” he could be charming and witty when he wanted—which helped camouflage his basic negotiating tactic of delay. “The lack of instructions and the necessity of consulting one’s government are always legitimate excuses in order to obtain delays in political affairs,” he once wrote. When Livingston tried to discuss the territory, Talleyrand simply denied that there was any treaty between France and Spain. “There never was a government in which less could be done by negotiation than here,” a frustrated Livingston wrote to Madison on September 1, 1802. “There is no people, no legislature, no counselors. One man is everything.”

But Livingston, although an inexperienced diplomat, tried to keep himself informed about the country to which he was ambassador. In March 1802, he warned Madison that France intended to “have a leading interest in the politics of our western country” and was preparing to send 5,000 to 7,000 troops from its Caribbean colony of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) to occupy New Orleans. But Napoléon’s troops in Saint Domingue were being decimated by a revolution and an outbreak of yellow fever. In June, Napoléon ordered Gen. Claude Victor to set out for New Orleans from the French controlled Netherlands. But by the time Victor assembled enough men and ships in January 1803, ice blocked the Dutchport, making it impossible for him to set sail.

That same month Jefferson asked James Monroe, a former member of Congress and former governor of Virginia, to join Livingston in Paris as minister extraordinary with discretionary powers to spend $9,375,000 to secure New Orleans and parts of the Floridas (to consolidate the U.S. position in the southeastern part of the continent). In financial straits at the time, Monroe sold his china and furniture to raise travel funds, asked a neighbor to manage his properties, and sailed for France on March 8, 1803, with Jefferson’s parting admonition ringing in his ears: “The future destinies of this republic” depended on his success.

By the time Monroe arrived in Paris on April 12, the situation had, unknown to him, radically altered: Napoléon had suddenly decided to sell the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States. He had always seen Saint Domingue, with a population of more than 500,000, producing enough sugar, coffee, indigo, cotton and cocoa to fill some 700 ships a year, as France’s most important holding in the Western Hemisphere. The Louisiana Territory, in Napoléon’s view, was useful mainly as a granary for Saint Domingue. With the colony in danger of being lost, the territory was less useful. Then, too, Napoléon was gearing up for another campaign against Britain and needed funds for that.

Napoléon’s brothers Joseph and Lucien had gone to see him at the Tuileries Palace on April 7, determined to convince him not to sell the territory. For one thing, they considered it foolish to voluntarily give up an important French holding on the American continent. For another, Britain had unofficially offered Joseph a bribe of £100,000 to persuade Napoléon not to let the Americans have Louisiana. But Napoléon’s mind was already made up. The First Consul happened to be sitting in his bath when his brothers arrived. “Gentlemen,” he announced, “think what you please about it. I have decided to sell Louisiana to the Americans.” To make his point to his astonished brothers, Napoléon abruptly stood up, then dropped back into the tub, drenching Joseph. A manservant slumped to the floor in a faint.

French historians point out that Napoléon had several reasons for this decision. “He probably concluded that, following American independence, France couldn’t hope to maintain a colony on the American continent,” says Jean Tulard, one of France’s foremost Napoléon scholars. “French policy makers had felt for some time that France’s possessions in the Antilles would inevitably be ‘contaminated’ by America’s idea of freedom and would eventually take their own independence. By the sale, Napoléon hoped to create a huge country in the Western Hemisphere to serve as a counterweight to Britain and maybe make trouble for it.”

On April 11, when Livingston called on Talleyrand for what he thought was yet another futile attempt to deal, the foreign minister, after the de rigueur small talk, suddenly asked whether the United States would perchance wish to buy the whole of the Louisiana Territory. In fact, Talleyrand was intruding on a deal that Napoléon had assigned to the French finance minister, François de Barbé-Marbois. The latter knew America well, having spent some years in Philadelphia in the late 1700s as French ambassador to the United States, where he got to know Washington, Jefferson, Livingston and Monroe. Barbé-Marbois received his orders on April 11, 1803, when Napoléon summoned him. “I renounce Louisiana,” Napoléon told him. “It is not only New Orleans that I will cede, it is the whole colony without reservation. I renounce it with the greatest regret. . . . I require a great deal of money for this war [with Britain].”

Thierry Lentz, a Napoléon historian and director of the Fondation Napoléon in Paris, contends that, for Napoléon, “It was basically just a big real estate deal. He was in a hurry to get some money for the depleted French treasury, although the relatively modest price shows that he was had in that deal. But he did manage to sell something that he didn’t really have any control over—there were few French settlers and no French administration over the territory—except on paper.” As for Jefferson, notes historian Cerami, “he actually wasn’t out to make this big a purchase. The whole thing came as a total surprise to him and his negotiating team in Paris, because it was, after all, Napoléon’s idea, not his.”

Showing up unexpectedly at the dinner party Livingston gave on April 12 for Monroe’s arrival, Barbé-Marbois discreetly asked Livingston to meet him later that night at the treasury office. There he confirmed Napoléon’s desire to sell the territory for $22,500,000. Livingston replied that he“would be ready to purchase provided the sum was reduced to reasonable limits.” Then he rushed home and worked until 3 a.m. writing a memorandum to Secretary of State Madison, concluding: “We shall do all we can to cheapen the purchase; but my present sentiment is that we shall buy.”

On April 15, Monroe and Livingston proposed $8 million.

At this, Barbé-Marbois pretended Napoléon had lost interest. But by April 27, he was saying that $15 million was as low as Napoléon would go. Though the Americans then countered with $12.7 million, the deal was struck for $15 million on April 29. The treaty was signed by Barbé-Marbois, Livingston and Monroe on May 2 and backdated to April 30. Although the purchase was undeniably a bargain, the price was still more than the young U.S. treasury could afford. But the resourceful Barbé-Marbois had an answer for that too. He had contacts at Britain’s Baring & Co. Bank, which agreed, along with several other banks, to make the actual purchase and pay Napoléon cash. The bank then turned over ownership of the Louisiana Territory to the United States in return for bonds, which were repaid over 15 years at 6 percent interest, making the final purchase price around $27 million. Neither Livingston nor Monroe had been authorized to buy all of the territory, or to spend $15 million—transatlantic mail took weeks, sometimes months, each way, so they had no time to request and receive approval of the deal from Washington. But an elated Livingston was aware that nearly doubling the size of America would make it a major player on the world scene one day, and he permitted himself some verbal euphoria: “We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives,” he said. “From this day the United States take their place among the powers of the first rank.”

It wasn’t until July 3 that news of the purchase reached U.S. shores, just in time for Americans to celebrate it on Independence Day. A Washington newspaper, the National Intelligencer , reflecting how most citizens felt, referred to the “widespread joy of millions at an event which history will record among the most splendid in our annals.” Though we have no historical evidence of how Jefferson felt about the purchase, notes Cerami, reports from those in his circle like Monroe refer to the president’s “great pleasure,” despite his fear that the deal had gone beyond his constitutional powers. Not all Americans agreed, however. The Boston Columbian Centinel editorialized, “We are to give money of which we have too little for land of which we already have too much.” And Congressman Joseph Quincy of Massachusetts so opposed the deal that he favored secession by the Northeastern states, “amicably if they can; violently if they must.”

The favorable majority, however, easily prevailed and New England remained in the Union. As for the ever-succinct Thomas Jefferson, he wasted little time on rhetoric. “The enlightened government of France saw, with just discernment,” he told Congress, with typical tact, on October 17, 1803, “the importance to both nations of such liberal arrangements as might best and permanently promote the peace, friendship, and interests of both.” But, excited by the commercial opportunities in the West, Jefferson, even before official notice of the treaty reached him, had already dispatched Meriwether Lewis to lead an expedition to explore the territory and the lands beyond. All the way to the Pacific.

JEFFERSON’S AMERICA, NAPOLEON’S FRANCE

“We have tried to capture the suspense and fascination of a story whose outcome is known, yet was not foreordained,” says Gail Feigenbaum, curator of the Jefferson-Napoléon show on view in New Orleans April 12 to August 31, “and to tell it through a rich variety of objects.” The variety includes three important documents: a copy of the treaty, which bears Jefferson’s signature; a document covering payment of claims by American citizens against France, signed by Napoléon; and the official report of transfer of the Louisiana Territory signed by a bereaved prefect, Pierre de Laussat. The exhibition points up how intertwined the two nations were at the time. A seascape portrays the Marquis de Lafayette’s ship La Victoire setting sail to carry him across the Atlantic in 1777 to fight in the American Revolution. (There is also a portrait of the marquis himself and a 1784 painting by French artist Jean Suau, Allegory of France Liberating America.) A mahogany and gilded bronze swan bed that belonged to the famous French beauty Juliette Récamier is also on display. Fashion-conscious American ladies reportedly imitated Récamier’s attire, but not her custom of receiving visitors in her bedroom. And John Trumbull’s huge painting The Signing of the Declaration of Independence documents the historic American event that so greatly impressed and influenced French revolutionary thinkers. It hangs not far from a color engraving of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, which was composed in 1789 by Lafayette with the advice of his American friend Thomas Jefferson.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Joseph A. Harriss | READ MORE

The Actual Louisiana Purchase Price

The $15 million price tag of the Louisiana Territory has been described as one of the greatest real estate bargains ever. But what did that actually buy?

It’s one of the most famous financial figures in American history. In 1803, the United States paid France $15 million for the Louisiana Territory. Henry Adams, in his 1909 history of the Jefferson administration, described the amount as “almost nothing.” At the 150th anniversary in 1953, Bernard DeVoto termed it “fantastically small.” Today, website after website translates the amount into terms everyone can understand: “4 cents an acre.”

These numbers may be the last vestige of the tradition of erasing Native Americans from American history.

Historian Robert Lee, who quotes the historians above, writes that the $15 million “ has long signaled one of world history’s most spectacular real estate windfalls .” This triumphalist vision of American history obscures things, however, and quite a bit more money. Lee does the math.

The Louisiana Territory was, of course, already inhabited. Under the doctrine of discovery, what the US actually purchased from the French wasn’t title to land but the right of preemption. Preemption was the legal authority—or legal fiction, depending on how you look at it—to be the sole purchaser of land from Indigenous people in the territory. The Louisiana Purchase was therefore only the starting cost. For decades afterwards, the US purchased Native American land in the former territory, often at outrageously undervalued prices.

“A violence-backed power imbalance favored US negotiators but never eliminated Indian leverage completely, resulting in a piecemeal take over” writes Less. The result? What another historian, quoted by Lee, calls “conquest by contract.”

So how much did the US pay Native Americans for the actual land in the Louisiana Territory, not counting land taken by executive order and other non-compensated methods?

“The sheer scope of the exchange has discouraged active investigation,” writes Lee.

Hundreds of treaties, agreements, and land seizures carved chunks out of Indian country. Promises of future goods and services as consideration have prevented agreements from projecting costs reliably. Broken treaties, altered agreements, and fragmented compliance combine to make it far more difficult to assess the amount expended for Indian title.

As Lee notes, some payments were still being budgeted for in 2015: a “$30,000 appropriation for a Pawnee cession of 10 million acres made in 1857.”

To come up with a more realistic figure of the total paid to Native Americans for the Louisiana Territory, Lee dug into financial audits used in legal proceedings since 1881, when Congress passed a jurisdictional act that allowed the Choctaw sued the US in the Court of Claims . Since then, “tribes have doggedly pursued claims for economic damages caused by broken or inequitable treaties, compelling auditors to dredge up information otherwise obscured by the splintered complexity of payments.”

Indian claims cases “crested in the 1930s.” Hundreds more cases were heard after the 1946 establishment of the Indian Claims Commission . After 1978, these cases “subsided but never ceased.”

The Court of Claims rarely ruled in favor of Native Americans. When it did, “offsets” were typically deducted from the awards, reducing them as much as 90 percent, including for the cost of children “recruited”—we would say “kidnapped” or “stolen” today—into boarding schools . A seven-year study of Sioux claims over the taking of the Black Hills, for instance, listed more than $34 million (in 1931 dollars) in potential offsets to any claims awards.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Nevertheless, the records of these cases are troves of financial data. Tallied and mapped, the results of Lee’s forensic accounting investigation show that the “aggregate disbursements made from 1804 to 2012 for discrete Indian cessions within the Louisiana Territory” add up to $2.6 billion. This price tag “dwarfs the $15 million deal for preemption. Adjusted for inflation, the figure is comparable to roughly $418 million in 1803 dollars or more than $8.5 billion in 2012—far more than historians have thought.”

In short, it cost a lot more than what Napoleon received. Not that Napoleon made out badly: he is supposed to have thought the territory worth 50 million francs; the US paid him 60 million francs plus 20 million francs in debt relief, funding for his plans for European empire rather than a more phantasmagorical North American empire.

This, of course, is only an economic accounting, not a moral one.

Teaching Tips:

- The Louisiana Purchase Treaty (1803) , courtesy of the National Archives

- A digital collection of related primary documents , courtesy of the Library of Congress

- The Indian Claims Commission Decisions , a forty-three-volume set documenting the claims of American Indian groups against the United States from 1946 to 1978

- “ Louisiana Purchase Exercise ,” a 1904 lesson plan inspired by the upcoming Lewis and Clark Exposition (1905), includes a recitation of the accepted price(s) for the Purchase.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- What Convenience Stores Say About “Urban War Zones”

- When All the English Had Tails

Remembering Sun Yat Sen Abroad

Taking Slavery West in the 1850s

Recent posts.

- Alfalfa: A Crop that Feeds Our Food

- But Why a Penguin?

- Shakespeare and Fanfiction

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

- Thomas Jefferson

- Louisiana & Lewis & Clark

The Louisiana Purchase

What was the louisiana purchase.

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 was a land deal between the United States and France, in which the U.S. acquired approximately 827,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for $15 million.

[T]his little event, of France possessing herself of Louisiana, ... is the embryo of a tornado which will burst on the countries on both shores of the Atlantic and involve in it’s effects their highest destinies. 1

President Thomas Jefferson wrote this prediction in an April 1802 letter to Pierre Samuel du Pont amid reports that Spain would retrocede to France the vast territory of Louisiana. As the United States had expanded westward, navigation of the Mississippi River and access to the port of New Orleans had become critical to American commerce, so this transfer of authority was cause for concern. Within a week of his letter to du Pont, Jefferson wrote U.S. Minister to France Robert Livingston: "every eye in the US. is now fixed on this affair of Louisiana. perhaps nothing since the revolutionary war has produced more uneasy sensations through the body of the nation." 2

The Fry-Jefferson Map of Virginia

The presence of Spain was not so provocative. A conflict over navigation of the Mississippi had been resolved in 1795 with a treaty in which Spain recognized the United States' right to use the river and to deposit goods in New Orleans for transfer to oceangoing vessels. In his letter to Livingston, Jefferson wrote, "Spain might have retained [New Orleans] quietly for years. her pacific dispositions, her feeble state, would induce her to increase our facilities there, so that her possession of the place would be hardly felt by us." He went on to speculate that "it would not perhaps be very long before some circumstance might arise which might make the cession of it to us the price of something of more worth to her." 3

Jefferson's vision of obtaining territory from Spain was altered by the prospect of having the much more powerful France of Napoleon Bonaparte as a next-door neighbor.

France had surrendered its North American possessions at the end of the French and Indian War. New Orleans and Louisiana west of the Mississippi were transferred to Spain in 1762, and French territories east of the Mississippi, including Canada, were ceded to Britain the next year. But Napoleon, who took power in 1799, aimed to restore France's presence on the continent.

The Louisiana situation reached a crisis point in October 1802 when Spain's King Charles IV signed a decree transferring the territory to France and the Spanish agent in New Orleans, acting on orders from the Spanish court, revoked Americans' access to the port's warehouses. These moves prompted outrage in the United States.

While Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison worked to resolve the issue through diplomatic channels, some factions in the West and the opposition Federalist Party called for war and advocated secession by the western territories in order to seize control of the lower Mississippi and New Orleans.

Negotiations

Aware of the need for action more visible than diplomatic maneuvering and concerned with the threat of disunion, Jefferson in January 1803 recommended that James Monroe join Livingston in Paris as minister extraordinary. (Later that same month, Jefferson asked Congress to fund an expedition that would cross the Louisiana territory, regardless of who controlled it, and proceed on to the Pacific. This would become the Lewis and Clark Expedition .) Monroe was a close personal friend and political ally of Jefferson's, but he also owned land in Kentucky and had spoken openly for the rights of the western territories.

Jefferson urged Monroe to accept the posting, saying he possessed "the unlimited confidence of the administration & of the Western people." Jefferson added: "all eyes, all hopes, are now fixed on you, .... for on the event of this mission depends the future destinies of this republic." 4

Shortly thereafter, Jefferson wrote to Kentucky's governor, James Garrard, to inform him of Monroe's appointment and to assure him that Monroe was empowered to enter into "such arrangements as may effectually secure our rights and interest in the Mississipi, and in the country Eastward of that." 5

As Jefferson noted in that letter, Monroe's charge was to obtain land east of the Mississippi. Monroe's instructions, drawn up by Madison and approved by Jefferson, allocated up to $10 million for the purchase of New Orleans and all or part of the Floridas. If this bid failed, Monroe was instructed to try to purchase just New Orleans, or, at the very least, secure U.S. access to the Mississippi and the port.

But when Monroe reached Paris on April 12, 1803, he learned from Livingston that a very different offer was on the table.

Napoleon's plans to re-establish France in the New World were unraveling. The French army sent to suppress a rebellion by slaves and free blacks in the sugar-rich colony of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti) had been decimated by yellow fever, and a new war with Britain seemed inevitable. France's minister of finance, François de Barbé-Marbois, who had always doubted Louisiana's worth, counseled Napoleon that Louisiana would be less valuable without Saint Domingue and, in the event of war, the territory would likely be taken by the British from Canada. France could not afford to send forces to occupy the entire Mississippi Valley, so why not abandon the idea of empire in America and sell the territory to the United States?

Napoleon agreed. On April 11, Foreign Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand told Livingston that France was willing to sell all of Louisiana. Livingston informed Monroe upon his arrival the next day.

Seizing on what Jefferson later called "a fugitive occurrence," Monroe and Livingston immediately entered into negotiations and on April 30 reached an agreement that exceeded their authority — the purchase of the Louisiana territory, including New Orleans, for $15 million. The acquisition of approximately 827,000 square miles would double the size of the United States.

Though rumors of the purchase preceded notification from Monroe and Livingston, their message reached Washington in time for an official announcement on July 4, 1803.

The purchase treaty had to be ratified by the end of October, which gave Jefferson and his Cabinet time to deliberate the issues of boundaries and constitutionality. Exact boundaries would have to be negotiated with Spain and England and so would not be set for several years, and Jefferson's Cabinet members argued that the constitutional amendment he proposed was not necessary. As time for ratification of the purchase treaty grew short, Jefferson accepted his Cabinet's counsel and rationalized: "it is the case of a guardian, investing the money of his ward in purchasing an important adjacent territory; & saying to him when of age, I did this for your good." 6

The Senate ratified the treaty on October 20 by a vote of 24 to 7. Spain, upset by the sale but without the military power to block it, formally returned Louisiana to France on November 30. France officially transferred the territory to the Americans on December 20, and the United States took formal possession on December 30.

Jefferson's prediction of a "tornado" that would burst upon the countries on both sides of the Atlantic had been averted, but his belief that the affair of Louisiana would impact upon "their highest destinies" proved prophetic indeed.

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, claims for France all territory drained by Mississippi River from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico and names it Louisiana.

New Orleans is founded.

France cedes New Orleans and Louisiana west of the Mississippi to Spain.

France cedes territories east of the Mississippi and north of New Orleans to Britain.

Treaty of Paris gives newly independent United States free access to the Mississippi.

Spain closes lower Mississippi and New Orleans to foreigners.

French Revolution begins.

Slaves revolt on Caribbean island of Saint Domingue, France's richest colony.

Spain reopens the Mississippi and New Orleans to Americans.

Napoleon Bonaparte seizes power in France.

Spain secretly agrees to return Louisiana to France in exchange for Etruria, a small kingdom in Italy.

President Jefferson names Robert Livingston minister to France.

Spain cedes Louisiana to France. New Orleans is closed to American shipping. French army sent to re-establish control in Saint Domingue is decimated.

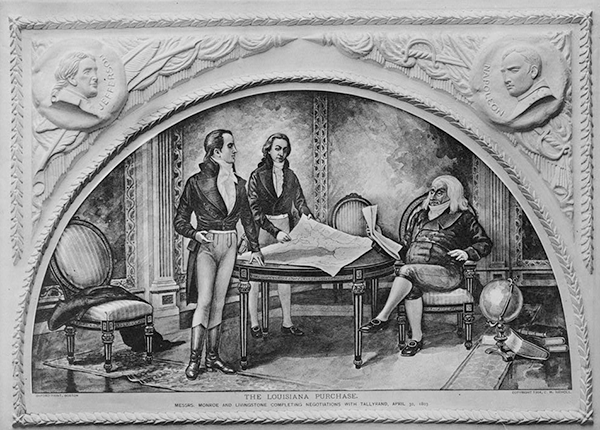

Jefferson sends James Monroe to join Livingston (pictured third from left) in France.

Napoleon decides against sending more troops to Saint Domingue and instead orders forces to sail to New Orleans.

Napoleon cancels military expedition to Louisiana.

Foreign Minister Talleyrand tells Livingston that France is willing to sell all of Louisiana.

Monroe arrives in Paris and joins Livingston in negotiations with Finance Minister Barbé-Marbois.

Monroe, Livingston, and Barbé-Marbois agree on terms of sale: $15 million for approximately 827,000 square miles of territory.

Britain declares war on France.

Purchase is officially announced in United States.

U.S. Senate ratifies purchase treaty.

Spain formally transfers Louisiana to France.

France formally transfers Louisiana to United States.

Further Sources

- Bond, Bradley G., ed. French Colonial Louisiana and the Atlantic World . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

- Cunningham, Noble, Jr. Jefferson and Monroe: Constant Friendship and Respect . Charlottesville: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2003.

- Fleming, Thomas J. The Louisiana Purchase . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- Lewis, James E., Jr. Louisiana Purchase: Jefferson's Noble Bargain . Charlottesville: Thomas Jefferson Foundation, 2003.

- Rodriquez, Junius P., ed. The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia . Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 2002.

- Look for further sources in the Thomas Jefferson Portal.

1. Jefferson to Du Pont, April 25, 1802, in PTJ , 37:332-34. Transcription available at Founders Online.

2. Jefferson to Livingston, April 18, 1802, in PTJ , 37:266. Transcription available online in Ford, 10:315.

3. Jefferson to Livingston, April 18, 1802, in PTJ , 37:264. Transcription available online in Ford, 10:312.

4. Jefferson to Monroe, January 13, 1803, in PTJ , 39:329. Transcription available online in Ford, 10:344.

5. Jefferson to Garrard, January 18, 1803, in PTJ , 39:348. Transcription available online in Ford, 8:203.

6. Jefferson to John C. Breckinridge, August 12, 1803, in PTJ , 41:186. Transcription available online in Ford, 8:244.

ADDRESS: 931 Thomas Jefferson Parkway Charlottesville, VA 22902 GENERAL INFORMATION: (434) 984-9800

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Louisiana Purchase

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2019 | Original: December 2, 2009

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 brought into the United States about 828,000 square miles of territory from France, thereby doubling the size of the young republic. What was known at the time as the Louisiana Territory stretched from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west and from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to the Canadian border in the north. Part or all of 15 states were eventually created from the land deal, which is considered one of the most important achievements of Thomas Jefferson’s presidency.

France in the New World

Beginning in the 17th century, France explored the Mississippi River valley and established scattered settlements in the region.

By the middle of the 18th century, France controlled more of the present-day United States than any other European power: from New Orleans northeast to the Great Lakes and northwest to modern-day Montana .

In 1762, during the French and Indian War , France ceded French Louisiana west of the Mississippi River to Spain and in 1763 transferred nearly all of its remaining North American holdings to Great Britain. Spain, no longer a dominant European power, did little to develop Louisiana during the next three decades.

Louisiana Territory Changes Hands

In 1796, Spain allied itself with France, leading Britain to use its powerful navy to cut off Spain from America. And in 1801, Spain signed a secret treaty with France to return the Louisiana Territory to France.

Reports of the retrocession caused considerable unease in the United States. Since the late 1780s, Americans had been moving westward into the Ohio River and Tennessee River valleys, and these settlers were highly dependent on free access to the Mississippi River and the strategic port of New Orleans.

U.S. officials feared that France, resurgent under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte , would soon seek to dominate the Mississippi River and access to the Gulf of Mexico . In a letter to U.S. minister to France Robert Livingston, President Thomas Jefferson stated, “The day that France takes possession of New Orleans…we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”

Livingston was ordered to negotiate with French Finance Minister Barbé-Marbois for the purchase of New Orleans.

Louisiana Purchase Negotiations

France was slow in taking control of Louisiana, but in 1802 Spanish authorities, apparently acting under French orders, revoked a U.S.-Spanish treaty that granted Americans the right to store goods in New Orleans.

In response, Jefferson sent future U.S. president James Monroe to Paris to aid Livingston in the New Orleans purchase talks. In mid-April 1803, shortly before Monroe’s arrival, the French asked a surprised Livingston if the United States was interested in purchasing all of Louisiana Territory.

It’s believed that the failure of France to put down a slave revolution in Haiti , the impending war with Great Britain and probable British naval blockade of France – combined with French economic difficulties – may have prompted Napoleon to offer Louisiana for sale to the United States.

Negotiations moved swiftly, and at the end of April the U.S. envoys agreed to pay $11,250,000 and assume claims of American citizens against France in the amount of $3,750,000. In exchange, the United States acquired the vast domain of Louisiana Territory, some 828,000 square miles of land.

The treaty was dated April 30 and signed on May 2. In October, the U.S. Senate ratified the purchase, and in December 1803 France transferred authority over the region to the United States.

Legacy of the Louisiana Purchase

The acquisition of the Louisiana Territory for the bargain price of less than three cents an acre was among Jefferson’s most notable achievements as president. American expansion westward into the new lands began immediately, and in 1804 a territorial government was established.

Jefferson soon commissioned the Lewis and Clark Expedition , led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, to explore the territory acquired in the Louisiana Purchase.

On April 30, 1812, exactly nine years after the Louisiana Purchase agreement was made, the first state to be carved from the territory – Louisiana – was admitted into the Union as the 18th U.S. state.

Access hundreds of hours of historical video, commercial free, with HISTORY Vault . Start your free trial today.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, the louisiana purchase, treaty between the united states of america and the french republic (1803).

Robert Livingston, James Monroe and Barbé Marbois | 1803

Negotiated by the administration of Thomas Jefferson and ratified by Congress on October 20, 1803, the Louisiana Purchase Treaty roughly doubled the size of the United States. An enormous area stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to what is now the Canadian border, the land would ultimately be carved into fifteenth separate states, including Kansas, Nebraska, and Missouri. The addition of new lands opened up conflicts over the disposition of Native people’s claims to land and sovereignty in the territory as well as the issue of slavery. Whether these new states permitted or prohibited slavery would affect the precarious balance of power between slave state and free state under the original Constitution. The 1820 debates over the admission of Missouri resulted in a “compromise” whereby Missouri would be admitted as a slave state; but all future states carved out of the territory above the 36-30 line would be free. For the next forty years, the nation became increasingly divided over slavery and congressional power to ban slavery in the territories. In Dred Scott v. Sanford , Chief Justice Taney declared that the Missouri Compromise unconstitutionally denied slave owners of their property rights under the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. The adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 ended the question of slavery in the territories. The Fourteenth Amendment transformed the treaty’s protection of the “rights, advantages and immunities of citizens of the United States” into the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States” which “no state shall” abridge.

Selected by

Laura F. Edwards

Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, and Professor of History at Princeton University

E. Claiborne Robins Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Richmond

His Catholic Majesty promises and engages on his part to cede to the French Republic six months after the full and entire execution of the conditions and Stipulations herein relative to his Royal Highness the Duke of Parma, the Colony or Province of Louisiana with the Same extent that it now has in the hand of Spain, & that it had when France possessed it; and Such as it Should be after the Treaties subsequently entered into between Spain and other States.

Article II

The inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States and admitted as soon as possible according to the principles of the federal Constitution to the enjoyment of all these rights, advantages and immunities of citizens of the United States, and in the mean time they shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty, property and the Religion which they profess.

Done at Paris the tenth day of Floreal in the eleventh year of the French Republic; and the 30th of April 1803.

Robt R Livingston [seal] Jas. Monroe [seal] Barbé Marbois [seal]

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

The Louisiana purchase

Journal title, journal issn, volume title.

Introduction: Excepting the Declaration of Independence there is no event in the history of America which has been more potent in shaping the course of the Republic than has the Louisiana Purchase. From this has arisen the great political and social problems which have agitated our country for the last hundred years.

Description

Collections.

Center for the Advancement of Digital Scholarship

K-State Libraries

1117 Mid-Campus Drive North, Manhattan, KS 66506

785-532-3514 | [email protected]

- Statements and Disclosures

- Accessibility

- © Kansas State University

Milestone Documents

Louisiana Purchase Treaty (1803)

Citation: Louisiana Purchase Treaty, April 30, 1803; Perfected Treaties, 1778 - 1945; General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View the French Exchange Copy in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

In this transaction with France, signed on April 30, 1803, the United States purchased 828,000 square miles of land west of the Mississippi River for $15 million. For roughly 4 cents an acre, the United States doubled its size, expanding the nation westward.

Originally, negotiators Robert Livingston and James Monroe were authorized to pay France up to $10 million solely for the port of New Orleans and the Floridas. However, when they were offered the entire territory of Louisiana – an area larger than Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal combined – the American negotiators swiftly agreed to a price of $15 million.

Although President Thomas Jefferson was generally a strict interpreter of the Constitution who wondered if the U.S. Government (and especially the President) was authorized to acquire new territory, the desire to expand the United States across the entire continent trumped his ideological beliefs. As Napoleon threatened to take back the offer, Jefferson squelched whatever doubts he had and prepared to occupy a land of unimaginable riches.

The Louisiana Purchase was the first major cession of land in a long series of expansions that span the 19th century. Within 50 years, the present-day borders of the contiguous United States would be solidified with the Gadsden Purchase.

Each expansion, though greatly increasing the size of the United States, also exposed the sectional weaknesses between the North and South, especially related to the issue of slavery. As new territories and states were created, the desire to maintain a balance between "free states" and "slave states" required a series of fragile compromises (notably the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 ). Eventually, as agreements became more difficult to achieve, civil war became inevitable.

In addition, the Louisiana Purchase ignored the potential impact on Native Americans. The land ceded in this agreement (and later expansions) was populated with thousands of American Indians across dozens of tribes. As territories and states were established, more and more Americans from the East traveled west, leading to conflict with Native Americans. Ultimately, Native people were forcibly moved on to reservations, losing vast acreage of their tribal lands, and the U.S. Government would force them to change their ways of life and try to erase their religions and cultural heritage.

The Louisiana Purchase Agreement is made up of the Treaty of Cession and the two conventions regarding the financial aspects of the transaction.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

Note: The three documents transcribed here are the treaty of cession and two conventions, one for the payment of 60 million francs ($11,250,000), the other for claims American citizens had made against France for 20 million francs ($3,750,000).

Treaty of Cession | First Convention | Second Convention

TREATY BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE FRENCH REPUBLIC

The President of the United States of America and the First Consul of the French Republic in the name of the French People desiring to remove all Source of misunderstanding relative to objects of discussion mentioned in the Second and fifth articles of the Convention of the 8th Vendémiaire an 9 (30 September 1800) relative to the rights claimed by the United States in virtue of the Treaty concluded at Madrid the 27 of October 1795, between His Catholic Majesty & the Said United States, & willing to Strengthen the union and friendship which at the time of the Said Convention was happily reestablished between the two nations have respectively named their Plenipotentiaries to wit The President of the United States, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate of the Said States; Robert R. Livingston Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States and James Monroe Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy extraordinary of the Said States near the Government of the French Republic; And the First Consul in the name of the French people, Citizen Francis Barbé Marbois Minister of the public treasury who after having respectively exchanged their full powers have agreed to the following Articles.

Whereas by the Article the third of the Treaty concluded at St Ildefonso the 9th Vendémiaire an 9 (1st October) 1800 between the First Consul of the French Republic and his Catholic Majesty it was agreed as follows.

"His Catholic Majesty promises and engages on his part to cede to the French Republic six months after the full and entire execution of the conditions and Stipulations herein relative to his Royal Highness the Duke of Parma, the Colony or Province of Louisiana with the Same extent that it now has in the hand of Spain, & that it had when France possessed it; and Such as it Should be after the Treaties subsequently entered into between Spain and other States."

And whereas in pursuance of the Treaty and particularly of the third article the French Republic has an incontestible title to the domain and to the possession of the said Territory--The First Consul of the French Republic desiring to give to the United States a strong proof of his friendship doth hereby cede to the United States in the name of the French Republic for ever and in full Sovereignty the said territory with all its rights and appurtenances as fully and in the Same manner as they have been acquired by the French Republic in virtue of the above mentioned Treaty concluded with his Catholic Majesty.

In the cession made by the preceeding article are included the adjacent Islands belonging to Louisiana all public lots and Squares, vacant lands and all public buildings, fortifications, barracks and other edifices which are not private property.--The Archives, papers & documents relative to the domain and Sovereignty of Louisiana and its dependances will be left in the possession of the Commissaries of the United States, and copies will be afterwards given in due form to the Magistrates and Municipal officers of such of the said papers and documents as may be necessary to them.

The inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States and admitted as soon as possible according to the principles of the federal Constitution to the enjoyment of all these rights, advantages and immunities of citizens of the United States, and in the mean time they shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty, property and the Religion which they profess.

There Shall be Sent by the Government of France a Commissary to Louisiana to the end that he do every act necessary as well to receive from the Officers of his Catholic Majesty the Said country and its dependances in the name of the French Republic if it has not been already done as to transmit it in the name of the French Republic to the Commissary or agent of the United States.

Immediately after the ratification of the present Treaty by the President of the United States and in case that of the first Consul's shall have been previously obtained, the commissary of the French Republic shall remit all military posts of New Orleans and other parts of the ceded territory to the Commissary or Commissaries named by the President to take possession--the troops whether of France or Spain who may be there shall cease to occupy any military post from the time of taking possession and shall be embarked as soon as possible in the course of three months after the ratification of this treaty.

The United States promise to execute Such treaties and articles as may have been agreed between Spain and the tribes and nations of Indians until by mutual consent of the United States and the said tribes or nations other Suitable articles Shall have been agreed upon.

As it is reciprocally advantageous to the commerce of France and the United States to encourage the communication of both nations for a limited time in the country ceded by the present treaty until general arrangements relative to commerce of both nations may be agreed on; it has been agreed between the contracting parties that the French Ships coming directly from France or any of her colonies loaded only with the produce and manufactures of France or her Said Colonies; and the Ships of Spain coming directly from Spain or any of her colonies loaded only with the produce or manufactures of Spain or her Colonies shall be admitted during the Space of twelve years in the Port of New-Orleans and in all other legal ports-of-entry within the ceded territory in the Same manner as the Ships of the United States coming directly from France or Spain or any of their Colonies without being Subject to any other or greater duty on merchandize or other or greater tonnage than that paid by the citizens of the United States.

During that Space of time above mentioned no other nation Shall have a right to the Same privileges in the Ports of the ceded territory--the twelve years Shall commence three months after the exchange of ratifications if it Shall take place in France or three months after it Shall have been notified at Paris to the French Government if it Shall take place in the United States; It is however well understood that the object of the above article is to favour the manufactures, Commerce, freight and navigation of France and of Spain So far as relates to the importations that the French and Spanish Shall make into the Said Ports of the United States without in any Sort affecting the regulations that the United States may make concerning the exportation of the produce and merchandize of the United States, or any right they may have to make Such regulations.

In future and for ever after the expiration of the twelve years, the Ships of France shall be treated upon the footing of the most favoured nations in the ports above mentioned.

The particular Convention Signed this day by the respective Ministers, having for its object to provide for the payment of debts due to the Citizens of the United States by the French Republic prior to the 30th Sept. 1800 (8th Vendémiaire an 9) is approved and to have its execution in the Same manner as if it had been inserted in this present treaty, and it Shall be ratified in the same form and in the Same time So that the one Shall not be ratified distinct from the other.

Another particular Convention Signed at the Same date as the present treaty relative to a definitive rule between the contracting parties is in the like manner approved and will be ratified in the Same form, and in the Same time and jointly.

The present treaty Shall be ratified in good and due form and the ratifications Shall be exchanged in the Space of Six months after the date of the Signature by the Ministers Plenipotentiary or Sooner if possible.

In faith whereof the respective Plenipotentiaries have Signed these articles in the French and English languages; declaring nevertheless that the present Treaty was originally agreed to in the French language; and have thereunto affixed their Seals.

Done at Paris the tenth day of Floreal in the eleventh year of the French Republic; and the 30th of April 1803.

Robt R Livingston [seal] Jas. Monroe [seal] Barbé Marbois [seal]

A CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE FRENCH REPUBLIC

The President of the United States of America and the First Consul of the French Republic in the name of the French people, in consequence of the treaty of cession of Louisiana which has been Signed this day; wishing to regulate definitively every thing which has relation to the Said cession have authorized to this effect the Plenipotentiaries, that is to say the President of the United States has, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate of the Said States, nominated for their Plenipoten tiaries, Robert R. Livingston, Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States, and James Monroe, Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy-Extraordinary of the Said United States, near the Government of the French Republic; and the First Consul of the French Republic, in the name of the French people, has named as Pleniopotentiary of the Said Republic the citizen Francis Barbé Marbois: who, in virtue of their full powers, which have been exchanged this day, have agreed to the followings articles:

The Government of the United States engages to pay to the French government in the manner Specified in the following article the sum of Sixty millions of francs independant of the Sum which Shall be fixed by another Convention for the payment of the debts due by France to citizens of the United States.

For the payment of the Sum of Sixty millions of francs mentioned in the preceeding article the United States shall create a Stock of eleven millions, two hundred and fifty thousand Dollars bearing an interest of Six percent per annum payable half yearly in London Amsterdam or Paris amounting by the half year to three hundred and thirty Seven thousand five hundred Dollars, according to the proportions which Shall be determined by the french Govenment to be paid at either place: The principal of the Said Stock to be reimbursed at the treasury of the United States in annual payments of not less than three millions of Dollars each; of which the first payment Shall commence fifteen years after the date of the exchange of ratifications:--this Stock Shall be transferred to the government of France or to Such person or persons as Shall be authorized to receive it in three months at most after the exchange of ratifications of this treaty and after Louisiana Shall be taken possession of the name of the Government of the United States.

It is further agreed that if the french Government Should be desirous of disposing of the Said Stock to receive the capital in Europe at Shorter terms that its measures for that purpose Shall be taken So as to favour in the greatest degree possible the credit of the United States, and to raise to the highest price the Said Stock.

It is agreed that the Dollar of the United States Specified in the present Convention shall be fixed at five francs 3333/100000 or five livres eight Sous tournois.

The present Convention Shall be ratified in good and due form, and the ratifications Shall be exchanged the Space of Six months to date from this day or Sooner it possible.

In faith of which the respective Plenipotentiaries have Signed the above articles both in the french and english languages, declaring nevertheless that the present treaty has been originally agreed on and written in the french language; to which they have hereunto affixed their Seals.

Done at Paris the tenth of Floreal eleventh year of the french Republic 30th April 1803 .

CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE FRENCH REPUBLIC

The President of the United States of America and the First Consul of the French Republic in the name of the French People having by a Treaty of this date terminated all difficulties relative to Louisiana, and established on a Solid foundation the friendship which unites the two nations and being desirous in complyance with the Second and fifth Articles of the Convention of the 8th Vendémiaire ninth year of the French Republic (30th September 1800) to Secure the payment of the Sums due by France to the citizens of the United States have respectively nominated as Plenipotentiaries that is to Say The President of the United States of America by and with the advise and consent of their Senate Robert R. Livingston Minister Plenipotentiary and James Monroe Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary of the Said States near the Government of the French Republic: and the First Consul in the name of the French People the Citizen Francis Barbé Marbois Minister of the public treasury; who after having exchanged their full powers have agreed to the following articles.

The debts due by France to citizens of the United States contracted before the 8th Vendémiaire ninth year of the French Republic (30th September 1800) Shall be paid according to the following regulations with interest at Six per Cent; to commence from the period when the accounts and vouchers were presented to the French Government.

The debts provided for by the preceeding Article are those whose result is comprised in the conjectural note annexed to the present Convention and which, with the interest cannot exceed the Sum of twenty millions of Francs. The claims comprised in the Said note which fall within the exceptions of the following articles, Shall not be admitted to the benefit of this provision.

The principal and interests of the Said debts Shall be discharged by the United States, by orders drawn by their Minister Plenipotentiary on their treasury, these orders Shall be payable Sixty days after the exchange of ratifications of the Treaty and the Conventions Signed this day, and after possession Shall be given of Louisiana by the Commissaries of France to those of the United States.

It is expressly agreed that the preceding articles Shall comprehend no debts but Such as are due to citizens of the United States who have been and are yet creditors of France for Supplies for embargoes and prizes made at Sea, in which the appeal has been properly lodged within the time mentioned in the Said Convention 8th Vendémiaire ninth year, (30th Sept 1800)

The preceding Articles Shall apply only, First: to captures of which the council of prizes Shall have ordered restitution, it being well understood that the claimant cannot have recourse to the United States otherwise than he might have had to the Government of the French republic, and only in case of insufficiency of the captors--2d the debts mentioned in the Said fifth Article of the Convention contracted before the 8th Vendémiaire an 9 (30th September 1800) the payment of which has been heretofore claimed of the actual Government of France and for which the creditors have a right to the protection of the United States;-- the Said 5th Article does not comprehend prizes whose condemnation has been or Shall be confirmed: it is the express intention of the contracting parties not to extend the benefit of the present Convention to reclamations of American citizens who Shall have established houses of Commerce in France, England or other countries than the United States in partnership with foreigners, and who by that reason and the nature of their commerce ought to be regarded as domiciliated in the places where Such house exist.--All agreements and bargains concerning merchandize, which Shall not be the property of American citizens, are equally excepted from the benefit of the said Conventions, Saving however to Such persons their claims in like manner as if this Treaty had not been made.

And that the different questions which may arise under the preceding article may be fairly investigated, the Ministers Plenipotentiary of the United States Shall name three persons, who Shall act from the present and provisionally, and who shall have full power to examine, without removing the documents, all the accounts of the different claims already liquidated by the Bureaus established for this purpose by the French Republic, and to ascertain whether they belong to the classes designated by the present Convention and the principles established in it or if they are not in one of its exceptions and on their Certificate, declaring that the debt is due to an American Citizen or his representative and that it existed before the 8th Vendémiaire 9th year (30 September 1800) the debtor shall be entitled to an order on the Treasury of the United States in the manner prescribed by the 3d Article.

The Same agents Shall likewise have power, without removing the documents, to examine the claims which are prepared for verification, and to certify those which ought to be admitted by uniting the necessary qualifications, and not being comprised in the exceptions contained in the present Convention.

The Same agents Shall likewise examine the claims which are not prepared for liquidation, and certify in writing those which in their judgement ought to be admitted to liquidation.

In proportion as the debts mentioned in these articles Shall be admitted they Shall be discharged with interest at Six per Cent: by the Treasury of the United States.

And that no debt shall not have the qualifications above mentioned and that no unjust or exorbitant demand may be admitted, the Commercial agent of the United States at Paris or such other agent as the Minister Plenipotentiary or the United States Shall think proper to nominate shall assist at the operations of the Bureaus and cooperate in the examinations of the claims; and if this agent Shall be of the opinion that any debt is not completely proved, or if he shall judge that it is not comprised in the principles of the fifth article above mentioned, and if notwithstanding his opinion the Bureaus established by the french Government should think that it ought to be liquidated, he shall transmit his observations to the board established by the United States, who, without removing documents, shall make a complete examination of the debt and vouchers which Support it, and report the result to the Minister of the United States.--The Minister of the United States Shall transmit his observations in all Such cases to the Minister of the treasury of the French Republic, on whose report the French Government Shall decide definitively in every case.

The rejection of any claim Shall have no other effect than to exempt the United States from the payment of it, the French Government reserving to itself, the right to decide definitively on Such claim So far as it concerns itself.

Every necessary decision Shall be made in the course of a year to commence from the exchange of ratifications, and no reclamation Shall be admitted afterwards.

In case of claims for debts contracted by the Government of France with citizens of the United States Since the 8th Vendé miaire 9th year/30 September 1800 not being comprised in this Convention may be pursued, and the payment demanded in the Same manner as if it had not been made.

The present convention Shall be ratified in good and due form and the ratifications Shall be exchanged in Six months from the date of the Signature of the Ministers Plenipotentiary, or Sooner if possible.

In faith of which, the respective Ministers Plenipotentiary have signed the above Articles both in the french and english languages, declaring nevertheless that the present treaty has been originally agreed on and written in the french language, to which they have hereunto affixed their Seals.

Done at Paris, the tenth of Floreal, eleventh year of the French Republic. 30th April 1803.

Louisiana Purchase Essay

The beginning of the 19 th century was a tumultuous time for the United States. There was ongoing strife within the country and around the country’s borders. The Reigning president at the time was Thomas Jefferson. One of Jefferson’s most significant acts as president was overseeing the Louisiana Purchase. The “Louisiana Purchase is still the largest land deal in the US history as it involved a $15 million price tag in 1803” (Sloane, 2004).

The transacted land amounted to over eight hundred thousand square miles. Jefferson brokered this deal through two of his ambassadors James Monroe and Robert Livingston. The idea to acquire Louisiana was conceived after the New Orleans port fell under Napoleon Bonaparte’s French territory. The port was of great importance to the US trade and its closure necessitated sending ambassadors to France. It was in this mission that Napoleon agreed to sell not only the New Orleans port but also the entire Louisiana territory.

Before the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson prided himself in being a strict constitutionalist. However, this enormous transaction put a blemish on Jefferson’s record of strict adherence to the constitution. Some people feel that the Louisiana Purchase was conducted within the confines of the United States constitution. This paper will explore the arguments forwarded by both sides of the debate and offer a personal interpretation of the matter.

The argument against Jefferson’s actions is always supported from various angles. Before the transaction was completed, Jefferson expressed fears that it would be deemed unconstitutional. Therefore, he forwarded a constitutional amendment that would eliminate doubts against the constitutionality of the transaction to senate representatives. However, Jefferson received advice against this process because it would take too long and Napoleon could change his mind within this period.

Eventually, Jefferson opted to draw up a constitutional amendment that would give the federal government power to acquire new land on behalf of the people (Les Benedict, 2007). This amendment was ratified by the senate a few months after the Louisiana Purchase was completed. One of the reasons why Jefferson’s actions did not raise a storm in 1803 is because the citizens were pleased with this purchase.

The argument against the constitutionality of the Louisiana Purchase is founded on the fact that the responsibility of acquiring new territory was not defined in the US constitution. The Louisiana Purchase had a huge impact on the US territory because it doubled its size at the time. The people who claim that Jefferson’s actions were unconstitutional argue that the constitution did not give him the right to acquire new territory (Levin & Chen, 2012).

This means that Jefferson’s actions were not defined by any part of the constitution and this makes them unlawful. The issue under contention is the unconstitutional expansion of territory. This is in spite of the fact that Thomas Jefferson did not assume presidency with any territory-expansion agendas. The Louisiana Purchase was just a series of events that ended with territory expansion.