REVIEW article

How to promote diversity and inclusion in educational settings: behavior change, climate surveys, and effective pro-diversity initiatives.

- Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

We review recent developments in the literature on diversity and inclusion in higher education settings. Diversity interventions increasingly focus on changing behaviors rather than mental constructs such as bias or attitudes. Additionally, there is now a greater emphasis on the evaluation of initiatives aimed at creating an inclusive climate. When trying to design an intervention to change behavior, it is advised to focus on a segment of the population (the “target audience”), to try to get people to adopt a small number of specific new behaviors (the “target behaviors”), and to address in the intervention the factors that affect the likelihood that members of the target audience will engage in the new target behaviors (the “barriers and benefits”). We report our recent work developing a climate survey that allows researchers and practitioners to identify these elements in a particular department or college. We then describe recent inclusion initiatives that have been shown to be effective in rigorous empirical studies. Taken together this paper shows that by implementing techniques based on research in the behavioral sciences it is possible to increase the sense of belonging, the success, and the graduation rate of minority students in STEM.

Introduction

Women, people of color, members of the LGBTQ + community, and members of other marginalized groups continue to be underrepresented in STEM fields ( National Science Foundation, 2020 ). Students from these groups are the target of both subtle and overt acts of discrimination, face negative stereotypes about their abilities, and experience disrespect and lack of inclusion by their instructors and peers ( Spencer and Castano, 2007 ; Wiggan, 2007 ; Cheryan et al., 2009 ). For example, students from marginalized groups are often assumed to be less intelligent and competent ( Moss-Racusin et al., 2014 ) and are often excluded when students form study groups or gather outside of class ( Slavin, 1990 ). Students from marginalized groups receive less challenging materials, worse feedback, and less time to respond to questions in class than their peers ( Beaman et al., 2006 ; Sadker et al., 2009 ). Additionally, the cultural mismatch between university norms and the cultural norms that students from marginalized groups were socialized in frequently leads to increased stress and negative emotions for these students ( Stephens et al., 2012 ).

Not surprisingly, students from marginalized groups are far more likely than high-status group members (e.g., White people, men) to report feeling as though they do not belong at universities ( Walton and Cohen, 2011 ). This is particularly problematic given that social belonging has been shown to be a key predictor of educational outcomes ( Dortch and Patel, 2017 ; Wolf et al., 2017 ; Murphy et al., 2020 ). Students who feel a greater sense of belonging are more likely to persist to graduation ( Strayhorn, 2012 ). Additionally, increased concerns about belonging can lead students to view common challenges—such as struggling to make friends or failing a test—as signs that they do not belong, promoting psychological disengagement and poorer educational outcomes ( Walton and Cohen, 2007 ). These challenges are exacerbated in STEM fields, which are typically dominated by members of high-status groups ( Rainey et al., 2018 ). Students from marginalized groups are particularly vulnerable to dropping out of STEM programs and the lack of a sense of community greatly contributes to this vulnerability ( O’Keefe, 2013 ).

It is clear then that the key to promoting academic success and retention of students from marginalized groups in STEM is creating an inclusive climate. In this article we will review recent developments within the diversity and inclusion literature about how to best promote inclusive behaviors and create an inclusive climate at colleges and universities. We will start out by describing recent shifts in the literature emphasizing the importance of changing behaviors rather than attitudes and the necessity to systematically evaluate diversity interventions. We will then review the key elements to designing effective interventions to promote diversity and inclusion. We will also talk about the use of focus groups and climate surveys to acquire the relevant background knowledge needed to design effective interventions. In the final section, we present recent initiatives that have successfully promoted diversity and inclusion in a variety of ways.

Recent Developments in Research on Diversity and Inclusion

A shift from reducing bias to promoting inclusive behavior.

Even though prejudice is communicated through behavior ( Carr et al., 2012 ), the traditional approach to prejudice reduction was to change explicit and implicit bias. The focus on bias was based on the assumption that changes in attitudes will subsequently lead to changes in behavior ( Dovidio et al., 2002 ). The universal acceptance of this assumption is surprising given the weak evidence for a link between attitudes and behavior. Explicit biases and attitudes more generally have been shown to predict behavior only weakly ( Wicker, 1969 ; Ajzen and Sheikh, 2013 ). Similarly, there is little to no connection between implicit bias and behavior ( Kurdi et al., 2019 ; Clayton et al., 2020 ). Implicit bias scores explain, at most, a very small proportion of the variability in intergroup behavior measured in lab settings, and this proportion is likely to be even smaller in more complex, real-world situations ( Oswald et al., 2013 ). Further, a change in implicit bias is not associated with a change in intergroup behavior. Lai et al. (2013) and Forscher et al. (2019) showed that while a variety of methods have been developed to change implicit bias, these methods produce trivial or nonexistent changes in intergroup behavior, and if they do, none of them last longer than 24 hours.

A growing body of research suggests that it is possible–and likely more effective–to focus on promoting inclusive behavior rather than improving individuals’ attitudes toward outgroup members. For example, Mousa (2020) randomly assigned Iraqi Christians displaced by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) either to an all-Christian soccer team or to a team mixed with Muslims. Christians with Muslim teammates were more likely to vote for a Muslim from another team to receive a sportsmanship award, register for a mixed faith team next season, and train with other Muslim soccer players six months after the intervention. However, attitudes toward Muslims more broadly did not change. Similarly, Scacco and Warren (2018) examined if sustained intergroup contact in an educational setting between Christian and Muslim men in Kaduna, Nigeria led to increased harmony and reduced discrimination between the two groups. After the intervention, there were no reported changes in prejudicial attitudes for either groups, but Christians and Muslims who had high levels of intergroup contact engaged in fewer discriminatory behaviors than peers who had low levels of intergroup contact. These findings demonstrate that while promoting both positive intergroup attitudes and inclusive behavior is ideal, it is necessary to target inclusive behaviors directly rather than trying to change people’s biased attitudes with the assumption that such change will translate into a subsequent behavior change.

Greater Emphasis on Evaluation

Since the Civil Rights Act of 1964, researchers and practitioners have developed a variety of initiatives to combat racial prejudice in the United States (for reviews see Murrar et al., 2017 ; Paluck and Green, 2009 ; Paluck et al., 2021 ). Although these initiatives have been tested in individual studies, primarily in the lab, many of them have not undergone the rigorous scientific testing that is required to be able to conclude that they are effective in real-world settings ( Paluck and Green, 2009 ). Further, the evaluation studies frequently examined only the effects on self-report attitudes and not behavioral outcomes, which is problematic for reasons outlined in the previous paragraphs. In light of this deficit, there has been a recent shift in this field of research which now emphasizes the need for systemic evaluation of the effectiveness of diversity initiatives in the field ( Moss-Racusin et al., 2014 ).

Recent work examining the effectiveness of diversity initiatives has found mixed evidence for the idea that existing strategies reduce discrimination, create more inclusive environments, or increase the representation of marginalized groups ( Noon, 2018 ; FitzGerald et al., 2019 ; Dover et al., 2020 ). Most diversity training or implicit bias training workshops have been shown to be ineffective ( Bezrukova et al., 2016 ; Chang et al., 2019 ). Some interventions meant to promote diversity and inclusion actually achieve the opposite effect ( Dobbin and Kalev, 2018 ). For example, Dobbin et al., (2007) found that diversity training workshops had little to no effect on improving workplace diversity and some actually led to a decline in the number of Black women in management positions at companies. Similarly, Kulik et al. (2007) found that employees often respond to mandatory diversity training with anger and resistance and some report increased animosity toward members of marginalized groups afterward.

Designing Successful Behavioral Interventions

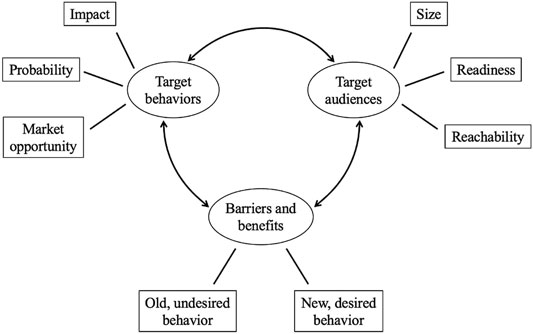

Behavior change interventions tend to be more effective if they involve a systematic, focused approach which consists of identifying and targeting specific behaviors, catering the intervention to a particular audience, and incorporating in the intervention relevant information about factors that affect how members of the target audience appraise the target behavior ( Campbell and Brauer, 2020 ). Below, we have outlined several methodological and theoretical considerations for practitioners whose goal is to develop a behavioral intervention to promote diversity and inclusion (see Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1 . Key elements to consider designing a behavior change intervention (adapted from Campbell and Brauer, 2020 ).

Selecting a Target Behavior

Once a broad issue has been identified (e.g., promoting diversity and inclusion at a university department), it must be distilled into a measurable, actionable goal ( Smith, 2006 ). For example, one might focus on an outcome such as reducing the racial achievement gap. It is critical that the desired outcome is quantifiable, as that will allow one to determine whether a behavioral intervention has been a success.

The next step is to identify and select a desired behavior to be adopted (i.e., the target behavior). The goal is to choose a target behavior that will lead to the desired outcome if people actually perform it ( Lee and Kotler, 2019 ). Continuing with the previous example, a behavioral intervention with the goal of reducing the racial achievement gap may target behaviors such as encouraging White students to include students of color in their study groups and social events or motivate instructors to highlight to a greater extent the contributions of female scientists. Sometimes it is possible to promote multiple similar target behaviors in the same intervention.

To identify potential target behaviors it is usually advised to conduct background research (see next section of this paper). This research may involve semi-structured interviews or focus groups with members of marginalized groups. Climate surveys with closed and open-ended questions can be equally informative. The goal of the background research is to determine the behaviors that affect members of marginalized groups the most. It is crucial to know what behaviors they find offensive and disrespectful and thereby decrease their sense of belonging, and what behaviors make them feel included, welcomed, and cared for. Examples of target behaviors to promote inclusion are attending diversity-outreach events or consciously forming diverse work groups.

Once a list of potential target behaviors has been established, it is advised to choose one of them for the intervention. The choice can be guided by evaluating each potential target behavior along a number of relevant dimensions ( McKenzie-Mohr, 2011 ). One may consider, for example, the extent to which the effect of changing from the old behavior to the new target behavior will have a large effect (“impact”), how likely people are to adopt the target behavior (“probability”), and how many people currently do not yet engage in the target behavior (“market opportunity”). For instance, an intervention seeking to reduce discriminatory behaviors toward members of the LGBTQ + community in STEM contexts might consider focusing on encouraging students to learn what terms hurt the feelings of queer people and then abstain from using them, get the students to avoid gendered language, or promote joining a queer-straight alliance at their university. While a large number students joining a queer-straight alliance would have a big effect on the sense of belonging of members of the LGBTQ + community (high impact), it is unlikely many students will adopt this behavior if they are not already predisposed to do so (low probability). Similarly, it may be easy to get students to switch to gender neutral language (high probability), but if most students are already using this language then promoting this behavior will lead to only minor improvements (low market opportunity).

Ultimately the goal is to choose a single behavior (or a small set of interrelated behaviors) that will make the biggest difference for members of marginalized groups and then design an intervention that specifically encourages the adoption of this behavior ( Wymer, 2011 ).

Selecting a Target Audience

One of the most vital considerations when designing a behavioral intervention is the selection of a specific target audience ( Kotler et al., 2001 ). Different segments of the population are receptive to different messages, possess different motivations, and have different reasons for engaging or not engaging in the desirable behavior ( Walsh et al., 2010 ). Although all individuals in a specific setting are usually exposed to a given pro-diversity initiative (e.g., everyone in a specific department or college), the initiative is more likely to be effective if it is designed with a specific subset of the population in mind ( French et al., 2010 ).

The first step in determining a target audience is to segment the population into various groups along either demographic criteria (e.g., Whites, men), occupation (e.g., students, teaching assistants, faculty, staff), or psychological dimensions (e.g., highly egalitarian individuals, individuals with racist attitudes, folks in the middle). The background research described in the next section will help practitioners identify the groups that have the most negative impact on the climate in a department or college. One can find out from members of marginalized groups, for example, which groups treat them in the most offensive way or which kind of people have the most negative impact on their sense of belonging.

Although multiple groups may emerge as potential target audiences, it is generally advised to choose only one as the focus of the intervention. Similar to the process of selecting a target behavior, the choice of the target audience can be guided by considering a number of relevant dimensions: How large is the segment, and what percentage of the members of this segment currently do not yet engage in the target behavior (“size”)? To what extent are members of this segment able, willing, and ready to change their behavior (“readiness”)? How easy it is to identify the members of this segment and are there known distribution channels for persuasive messages (“reachability”)? Teaching assistants may be a group that can easily be instructed to adopt certain behaviors (high reachability), individuals with hostile feelings toward certain social groups may not be willing to behave inclusively (low readiness), and academic advisors may be a group that is too small and that students from marginalized backgrounds interact with too infrequently to be chosen as the target audience (small size).

Most effective behavior change interventions are designed with a single target audience in mind. That is, the communications and campaign materials are designed so that they are appealing and persuasive for the members of the chosen target audience. The objective should thus be to choose a single target audience that can be persuaded to adopt the target behavior and has a big impact on how included members of marginalized groups feel in the department or college.

Barriers and Benefits

It is critical to consider the factors that influence the likelihood that members of the target audience will engage in the desired target behavior, the so-called “barriers” and “benefits” ( Lefebvre, 2011 ). Barriers refer to anything that prevents an individual from engaging in a given behavior. Benefits are the positive outcomes an individual anticipates receiving as a result of engaging in the behavior. The ultimate goal is to design an intervention that makes salient the target audience’s perceived benefits of the new, desired target behavior and the perceived barriers toward engaging in the current, undesired behavior ( McKenzie-Mohr and Schultz, 2014 ).

Practitioners likely want to conduct background research to learn about the target audience’s motivations to engage in various behaviors. This can again be done with interviews, focus groups, or climate surveys, but this time the responses of members of the target audience, rather than the responses of members of marginalized groups, are most relevant. One should find out why members of the target audience currently do not perform the target behavior. Are there any logistic barriers (e.g., lack of opportunity) or psychological barriers (i.e., discomfort experienced around certain groups)? Are there any incorrect beliefs that underly the current behavior? The background research should also identify the positive consequences members of the target audience value and expect to experience when performing the target behavior. These consequences can then be highlighted in the intervention.

Both barriers and benefits can be abstract or concrete, internal or external, and real or perceived. For example, if an intervention seeks to encourage students from different backgrounds to be friendly to one another in the classroom members of the target audience may be apprehensive when interacting with outgroup members due to fear of saying something offensive (a barrier) but would interact more frequently with outgroup members if they believed that it would provide them an opportunity to make new friends (benefits). A well-designed behavioral intervention would then use this information to craft persuasive messages that directly address the target audience’s barriers and benefits. In this specific example, the intervention might involve providing people with tools to avoid offensive language and emphasize the potential to make new friends.

Elements That Increase the Persistence of a Behavioral Change

Sometimes people adopt a new behavior but then switch back to the old, undesired behavior after a few days or weeks. What can be done to increase the persistence of behavior change? One strategy that has proven to be particularly effective is to change the assumptions that people make about themselves and their environments ( Frey and Rogers, 2014 ; Walton and Wilson, 2018 ). For example, believing that one is not culturally competent will lead to interpreting difficult interactions with outgroup members as proof of this assumption. The more entrenched these beliefs become, the more difficult behaviors are to change. However, the human tendency to “make meaning” of oneself and one’s social situations can be harnessed for positive behavioral change. By altering the assumptions that lead to undesirable behaviors, it is possible to set in motion recursive cycles where a person’s new behavior leads to positive reactions in the environment, which in turn reinforces the self-representation that they are “the kind of person” who cares about this issue (e.g., diversity) and engages in these behaviors (e.g., inclusive behaviors). Consider an example from a different domain: Fostering a growth mindset where students start to believe they can improve through practice will change how they interpret successes and failures, thereby disrupting the negative feedback cycle that leads to poorer performance in school (see Yeager et al., 2019 ).

In addition, interventions that foster habit formation are more likely to increase the persistence of new behaviors ( Wood and Rünger, 2016 ). Interventions can promote habit formation by increasing the perceived difficulty of performing an undesirable behavior or by decreasing the perceived difficulty of doing the new target behavior. People will most often engage in behaviors that they perceive as being easy to do, regardless of whether or not the difference in difficulty is minimal. Additionally, providing easy to understand, recurring cues that encourage desirable behaviors and disrupt old, undesirable behaviors can help facilitate habit formation.

How to Conduct Relevant Background Research

There are a variety of ways how members of higher education institutions can identify the diversity-related issues that should be addressed in their department or college. The most frequently used methods are focus groups and climate surveys. We will discuss each of these methods below.

Focus groups are effective because a group member’s comment may cause other members to remember issues that they would not have thought of otherwise. It is easy to recruit students from marginalized groups by appealing to their departmental citizenship or by promising attractive prizes (e.g., two $100 gift certificates that will be given out to two randomly selected members of the focus group). It is generally advised to form groups of individuals sharing some social identity (i.e., African Americans, Latinxs, women in technical fields). Most individuals feel more comfortable voicing their concerns if the focus group facilitator also shares their social identity. Many universities have skilled focus group facilitators, but if necessary, it is possible to train research assistants by directing them to appropriate resources ( Krueger, 1994 ; https://fyi.extension.wisc.edu/programdevelopment/files/2016/04/Tipsheet5.pdf ).

Focus group members should be encouraged to talk about the situations in which they felt excluded, disrespected, or discriminated against. For example, focus group members might be asked questions such as “What exactly did the other person do or say? Where did the situation occur (in the classroom, during office hours)? Who was the other person (peer, instructor, staff)?” Focus group members should then be asked about the situations in which they felt included, respected, and cared for. Again, the goal should be to obtain precise information about the exact nature of the behaviors, the place in which they occurred, and person who engaged in the behaviors. It is useful to ask about the relative impact of these negative and positive behaviors. For example, one might ask “If you could eliminate one behavior here in this department which one would it be?” and “Among all the inclusive and respectful behaviors you just mentioned which one would increase your sense of belonging the most?”.

To assess the barriers and benefits of the potential target behaviors it can be useful to conduct focus groups with individuals who a priori do not come from any of the marginalized groups mentioned above. The facilitator can describe the negative behaviors (without labeling them as discriminatory) and ask whether the focus group members sometimes engage in them and if they do, why. One might ask about potential pathways to eliminate these undesired behaviors, e.g., “What would have to be different for you–or your peers–to no longer behave like that?”. The next step is to have a similar discussion about the positive target behavior: What prevents focus group members currently from engaging in this behavior? What could someone say or show to them so that they would engage in this behavior? If some members of the focus groups have recently started to do the positive behavior, what got them to change in the first place?

Focus groups are also useful to determine how able, willing, and ready to change their behavior members of different potential target audiences are. Several factors contribute to individuals’ “readiness” to change their behavior. These factors include openness to acting more inclusively ( Brauer et al., in press ), internal motivation to respond without prejudice ( Plant and Devine, 1998 ), lack of discomfort interacting with members of different social groups ( Stephan, 2014 ), and general enthusiasm for diversity ( Pittinsky et al., 2011 ). Facilitators can get at these factors by asking the members of the focus group about their motivation and perceived ability to engage in the target behavior.

Climate surveys are effective because they usually provide data from a larger and thus more representative sample in a given department or college. Various techniques exist to increase the response rate of respondents (e.g., Dykema et al., 2013 ). The exact content and length of a climate survey depend on the participant population and the frequency with which the survey is administered. The online supplemental material contains two examples developed by the Wisconsin Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation (WiscAMP), one for graduate students of a university department and one for all undergraduate students on a campus. Other climate surveys used in higher education and numerous relevant references can be downloaded from this web address: http://psych.wisc.edu/Brauer/BrauerLab/index.php/campaign-materials/information-resources/

All climate surveys should measure demographic information, but in smaller units, anonymity may be an issue. Once gender identity is crossed with racial/ethnic identity and occupation (e.g., postdoc vs. assistant professor vs. full professor) it may no longer be possible to protect all respondents’ anonymity. The solution is to form a small number of relatively large categories such that it is unlikely that there will be fewer than five respondents when all these categories are crossed with each other. If the analyses reveal that certain groups of respondents are too small, then the presentation of the results should be adjusted. For example, the means can be broken down once by gender identity and once by race/ethnicity, but not by gender identity and race/ethnicity.

To address the anonymity issue, we recently conducted a climate survey in which we only asked two demographic questions: “Do you identify as a man, yes or no?” and “Do you identify as a member of a marginalized group (unrelated to gender identity), yes or no?” We justified the use of these questions in the survey by explaining that the gender identity question was asked in this way because research shows that individuals who identify as men are less often the target of sexual assault than those who do not identify as men. We also provided a brief definition of “marginalized groups.”

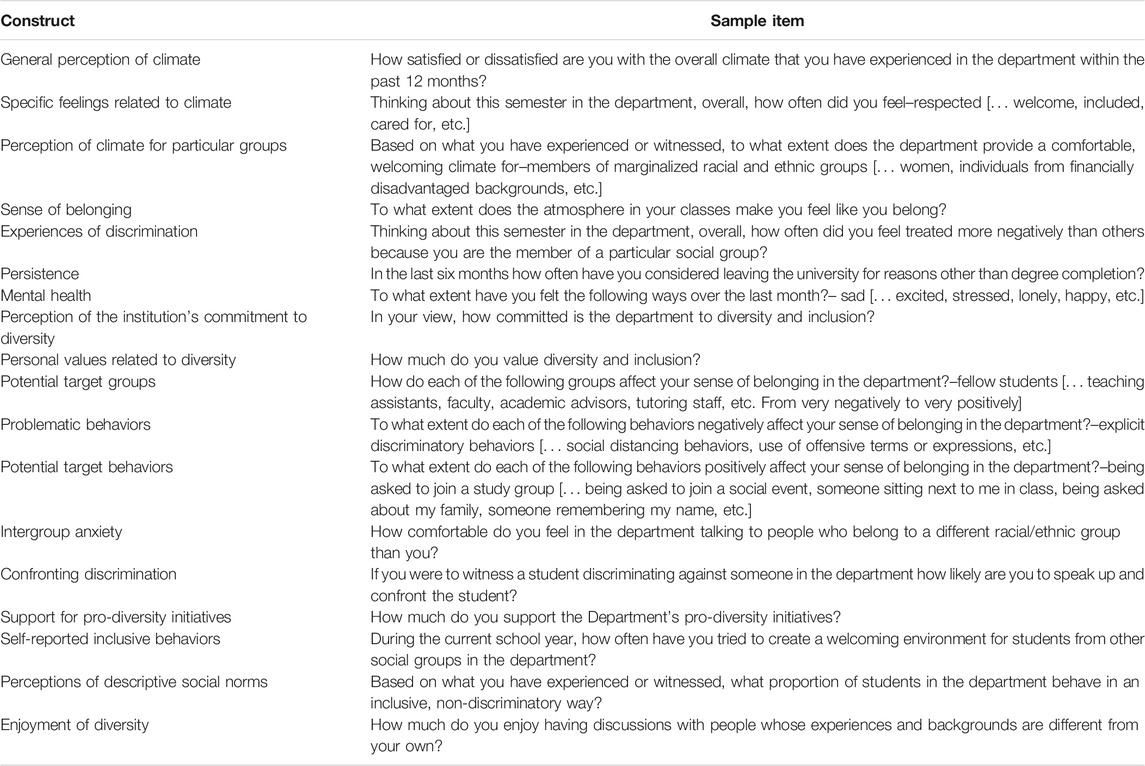

Climate surveys have two goals. They should provide an accurate reading of respondents’ perception of the social climate and they should suggest concrete action steps about initiatives to be implemented (see Table 1 for a list of constructs that are frequently measured in climate surveys). To achieve the first goal the climate survey should contain at least one question about the overall climate and several questions about specific feelings related to the social climate. In addition, the survey should assess sense of belonging, as well as mental and physical health. Most climate surveys also include items about respondents’ experiences of discrimination and their intention to remain in the institution (sometimes referred to as “persistence”). Finally, the climate survey may assess a variety of other constructs such as respondents’ perception of the institution’s commitment to diversity, their personal values related to diversity, their level of discomfort being around people from other social groups (sometimes referred to as “intergroup anxiety”) and self-reported inclusive behaviors.

TABLE 1 . List of constructs that are frequently measured in climate surveys.

To achieve the second goal–identification of concrete action steps about initiatives to be implemented–the climate survey needs to contain questions that help identify potential target behaviors, potential target audiences, and the barriers and benefits. It is helpful to ask respondents about the groups of individuals that have the most negative impact on their experience in the Department. It is further important to get information about the behaviors that should be discouraged (behaviors that negatively affect the well-being of individuals belonging to marginalized groups) and behaviors that should be promoted in the future (behaviors that make members of marginalized groups feel welcome and included). Once these behaviors have been identified, which will likely be the case after the climate survey has been implemented once or twice in a given Department, it is even possible to include items that measure the barriers and benefits for these behaviors.

As will be described in the next section, one of the most effective ways to promote an inclusive climate is to make salient that inclusion is a social norm. People’s perceptions of social norms are determined in part by what their peers think and do, and it is thus important for a climate survey to assess how common inclusive beliefs and behaviors are (the so-called “descriptive norms”). The above-mentioned items measuring personal values related to diversity partially achieve this purpose. In addition, consider including in the climate survey items that measure respondents’ support for their department’s pro-diversity initiatives, their enjoyment of diversity, their self-reported inclusive behaviors, and their perceptions of the proportion of peers who behave in an inclusive, non-discriminatory way. The survey shown in the online Supplemental Material contains additional items that assess respondent’s perceptions of the extent to which it is “descriptively normative” to be inclusive. It can be highly effective to create persuasive messages in which the average response to these items is reported. For example, if respondents from marginalized groups answered that a numerical majority of their peers engage in inclusive behaviors and abstain from engaging in discriminatory behaviors, then obviously inclusion is a social norm. As will be explained in more detail in the next section, such “social norms messages” have been shown to promote the occurrence of inclusive behaviors and to promote a welcoming social climate, as long as is it acknowledged that acts of bigotry and exclusion still occur and it is communicated that the department or college will continue its diversity efforts until members of marginalized groups feel just as welcome and included as members of nonmarginalized groups.

Overview of Recently Developed Initiatives to Promote Inclusion

A few new approaches to promoting inclusion stand out among the rest. Rather than taking a traditional approach of reducing biased attitudes or raising awareness about persistent prejudice, many of these new initiatives focus on changing behavior. We will discuss in detail two types of interventions, one involving social norms messaging and the other promoting intergroup contact. We will also briefly describe the “pride and prejudice” approach to inclusion in academia. While only some of these initiatives have been specifically tested as ways to improve inclusion in STEM settings, all of them can easily be applied in these settings as they show promise for increasing inclusion in academic contexts.

Social Norms Messaging

Social norms influence behavior in a way that is consistent with desirable normative behavior ( McDonald and Crandall, 2015 ). Social norms messaging–persuasive messages about social norms–has recently emerged as a promising method for promoting inclusion ( Murrar et al., 2020 ). There are two main types of social norms, descriptive (i.e., what behaviors are common among a group of people) and injunctive (i.e., what is approved of among a group of people; Cialdini et al., 1990 ). Interventions that utilize messages about descriptive social norms have been used for many years and have been proven successful in a variety of areas (e.g., energy conservation, binge drinking among college students; Frey and Rogers, 2014 ; Lewis and Neighbors, 2006 ; Miller and Prentice, 2016 ). Such interventions influence behavior by changing or correcting individuals’ perceptions of their peers’ behavior, which is particularly powerful because people rely on each other and their environment for guidance on how to behave ( Rhodes et al., 2020 ).

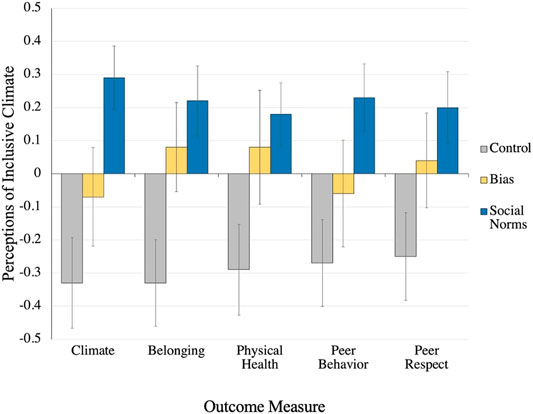

Prejudice is often blamed on conformity to social norms ( Crandall et al., 2002 ). However, researchers have started to employ social norms messaging as a way to improve intergroup outcomes. For example, Murrar and colleagues (2020) developed two interventions that targeted peoples’ perceptions of their peers’ pro-diversity attitudes and inclusive behaviors (i.e., descriptive norms) and tested them within college classrooms. One intervention involved placing posters inside classrooms that communicated that most students at the university embrace diversity and welcome people from all backgrounds into the campus community. The other intervention consisted of a short video that portrayed interviews with students who expressed pro-diversity attitudes and intentions to behave inclusively. The video also showed interviews with diversity and inclusion experts who reported that the blatant acts of discrimination, which undoubtedly occur on campus and affect the well-being of students from marginalized groups, are perpetrated by a numerical minority of students. The interventions led to an increase in inclusive behaviors in all students, an enhanced sense of belonging among students from marginalized groups, and a reduction in the achievement gap (see Figure 2 ). Note that Murrar and colleagues’ Experiment 6 specifically examined the effectiveness of the intervention in STEM courses.

FIGURE 2 . Effect of condition on outcomes of interest for students from marginalized groups in experiment 5 of Murrar et al., 2020 . Note: The authors compared their social norms intervention to a no-exposure control group and an intervention highlighting bias.

Another intervention strategy that successfully utilized social norms messaging and improved the well-being of college students from marginalized groups was developed and tested by Brauer et al. (in press) . Using the steps to designing successful behavior interventions described earlier, these authors identified the target behavior (inclusive classroom behavior), target audience (White university students), barriers (perceptions of peer inclusive behaviors and lack of motivation to behave inclusively) and benefits (importance of working and communicating well with a diverse group of people for others and oneself) to design a theoretically informed intervention strategy: a one-page document to be included in course syllabi. The document included not only social norms messaging about students’ inclusive behaviors (descriptive norms), but also statements by the university leadership endorsing diversity (highlighting injunctive norms, Rhodes et al., 2020 ), a short text about the benefits of learning to behave inclusively (inspired by utility value interventions; Harackiewicz et al., 2016 ) and concrete behavioral recommendations (inspired by SMART goals; Wade, 2009 ). This approach of applying multiple theories in an intervention creates “theoretical synergy,” which refers to the situation where the elements of a multifaceted intervention mutually reinforce each other and thus become particularly effective ( Paluck et al., 2021 ).

Posters, videos, and syllabi documents are just a few ways through which social norms messaging can be implemented in classrooms to promote inclusive behaviors and improve the classroom climate for students belonging to marginalized groups. Social norms messaging can also be considered a cheap, easy, and flexible way for instructors to shape students’ norm perceptions of a classroom early on and establish expectations for inclusive behavior. When inclusive norms are established early, students are more likely to abide by them.

Intergroup Contact

The intergroup contact hypothesis, first proposed by Allport (1954) , has been the basis for many prejudice reduction strategies. The theory suggests that contact between members of different groups can cause prejudice reduction if there is equal status between the groups and they are in pursuit of common goals. Intergroup contact has rarely been tested as a means to promote inclusion in STEM settings, but some recent experiments involving interventions that utilize intergroup contact have shown promise in their ability to promote inclusion and reduce the occurrence of discriminatory behavior.

Described earlier in this paper, Mousa (2020) , Scacco and Warren (2018) are examples for how intergroup contact can promote inclusion in academic and non-academic settings. Similarly, Lowe (2021) randomly assigned men from different castes in India to be cricket teammates and compete against other teams. Lowe examined one to three weeks after the end of the cricket league whether intergroup contact experienced through being on a mixed-caste sports team and having opponents from different castes would affect willingness to interact with people from other castes, ingroup favoritism, and efficiency and trust in trading goods that had monetary value. Whereas collaborative contact improved the three outcomes, adversarial contact (i.e., contact through being opponents to different caste members) resulted in the opposite effects.

Lowe (2021) , Mousa (2020) , Scacco and Warren (2018) intergroup contact interventions show the importance of providing long-term intergroup interactions when trying to reduce discriminatory behavior and promote inclusive behavior. In particular, if the interactions involve being on the same teams and sharing common goals, engagement in inclusive behaviors and decision-making will be a likely outcome. Note that none of these interventions altered people’s attitudes. Attitude change is not a precondition for behavior change to occur. Classroom instructors in STEM can leverage insights from the research on intergroup contact by incorporating numerous opportunities for intergroup interaction in the classroom as well as in assignments and projects throughout the course. One easy way to achieve this goal is to form project groups randomly rather than allowing students to form groups themselves.

Pride and Prejudice

A new strategy for promoting inclusion in academia is the “Pride and Prejudice” approach, which has been created to address the complexity of marginalized identities ( Brannon and Lin, 2020 ). “Pride” refers to the acknowledgment of the history and culture of students from marginalized groups (e.g., classes, groups, and spaces dedicated to marginalized groups), whereas “prejudice” refers to initiatives that address the discrimination experienced by students from these groups. The key idea of this approach is that identity is a source for both pride and prejudice for those belonging to marginalized groups. Both supporting marginalized groups and addressing instances of prejudice are pathways to inclusion in academic settings.

Support for the “Pride and Prejudice” approach comes from Brannon and Lin (2020) analysis of demands made by students from 80 United States colleges and universities compiled in 2016 (see thedemands.org ) following a series of racial discrimination protests regarding what changes they wanted to see on their campuses ( Hartocollis and Bidgood, 2015 ). Their analysis revealed that most demands referenced pride experiences and prejudice experiences. Brannon and Lin also analyzed longitudinal data to assess for pride and prejudice experiences among college students in 27 colleges and universities and the relationships of these experiences with several intergroup outcomes. The results showed that pride and prejudice experiences impact students’ sense of belonging via ingroup and outgroup closeness. The findings suggest that to promote inclusion in academia, it may be best to create settings that support and celebrate the cultures of marginalized groups in addition to having practices in place to mitigate prejudice and discrimination toward marginalized groups.

A variety of strategies have been developed to reduce the achievement gap (e.g., self-affirmation interventions, promoting growth-mindsets, etc…). However, many of these strategies are meant to help students from marginalized students succeed in an environment that is not inclusive. Instead of placing the burden on students from marginalized groups (i.e., teaching them how to deal with the exclusion and discrimination), researchers and practitioners should shift their focus to creating inclusive academic environments. The research discussed in this article provides a framework for developing successful interventions to promote diversity and inclusion. Such an approach may hold the key to improving the experiences of individuals from marginalized groups by targeting the behaviors that can make them feel more recognized, respected, welcomed, and valued. In the long run this will be the most effective way to raise the success and graduation of students from marginalized groups in STEM.

Author Contributions

GM, NI, and MB participated in the writing and revision of the paper. MB approved the paper for submission.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.668250/full#supplementary-material

Ajzen, I., and Sheikh, S. (2013). Action versus Inaction: Anticipated Affect in the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 43 (1), 155–162. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00989.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Allport, G. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice . Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Beaman, R., Wheldall, K., and Kemp, C. (2006). Differential Teacher Attention to Boys and Girls in the Classroom. Educ. Rev. 58, 339–366. doi:10.1080/00131910600748406

Bezrukova, K., Spell, C. S., Perry, J. L., and Jehn, K. A. (2016). A Meta-Analytical Integration of over 40 Years of Research on Diversity Training Evaluation. Psychol. Bull. 142 (11), 1227–1274. doi:10.1037/bul0000067

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brannon, T. N., and Lin, A. (2020). “Pride and Prejudice” Pathways to Belonging: Implications for Inclusive Diversity Practices within Mainstream Institutions. Am. Psychol. 76, 488–501. doi:10.1037/amp0000643

Brauer, M., Dumesnil, A., and Campbell, M. R. (in press). Using a Social Marketing Approach to Develop a Pro-diversity Intervention. J. Soc. Marketing.

Google Scholar

Campbell, M. R., and Brauer, M. (2020). Incorporating Social-Marketing Insights into Prejudice Research: Advancing Theory and Demonstrating Real-World Applications. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 608–629. doi:10.1177/1745691619896622

Carr, P. B., Dweck, C. S., and Pauker, K. (2012). “Prejudiced” Behavior without Prejudice? Beliefs about the Malleability of Prejudice Affect Interracial Interactions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 103 (3), 452–471. doi:10.1037/a0028849

Chang, E. H., Milkman, K. L., Gromet, D. M., Rebele, R. W., Massey, C., Duckworth, A. L., et al. (2019). The Mixed Effects of Online Diversity Training. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 116 (16), 7778–7783. doi:10.1073/pnas.1816076116

Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Davies, P. G., and Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient Belonging: How Stereotypical Cues Impact Gender Participation in Computer Science. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 97 (6), 1045–1060. doi:10.1037/a0016239

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., and Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: Recycling the Concept of Norms to Reduce Littering in Public Places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 58, 1015–1026. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

Clayton, K., Horrillo, J., and Sniderman, P. M. (2020). The Validity of the IAT and the AMP as Measures of Racial Prejudice. Available at SSRN . doi:10.2139/ssrn.3744338

Crandall, C. S., Eshleman, A., and O'Brien, L. (2002). Social Norms and the Expression and Suppression of Prejudice: The Struggle for Internalization. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 82, 359–378. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.359

Dobbin, F., Kalev, A., and Kelly, E. (2007). Diversity Management in Corporate America. Contexts . 6 (4), 21–27. doi:10.1525/ctx.2007.6.4.21

Dobbin, F., and Kalev, A. (2018). Why Doesn't Diversity Training Work? the Challenge for Industry and Academia. Anthropol. Now . 10 (2), 48–55. doi:10.1080/19428200.2018.1493182

Dortch, D., and Patel, C. (2017). Black Undergraduate Women and Their Sense of Belonging in STEM at Predominantly White Institutions. NASPA J. About Women Higher Education . 10 (2), 202–215. doi:10.1080/19407882.2017.1331854

Dover, T. L., Kaiser, C. R., and Major, B. (2020). Mixed Signals: The Unintended Effects of Diversity Initiatives. Soc. Issues Pol. Rev. 14 (1), 152–181. doi:10.1111/sipr.12059

Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K., and Gaertner, S. L. (2002). Implicit and Explicit Prejudice and Interracial Interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 82 (1), 62–68. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.62

Dykema, J., Stevenson, J., Klein, L., Kim, Y., and Day, B. (2013). Effects of E-Mailed versus Mailed Invitations and Incentives on Response Rates, Data Quality, and Costs in a Web Survey of university Faculty. Soc. Sci. Computer Rev. 31 (3), 359–370. doi:10.1177/0894439312465254

FitzGerald, C., Martin, A., Berner, D., and Hurst, S. (2019). Interventions Designed to Reduce Implicit Prejudices and Implicit Stereotypes in Real World Contexts: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychol. 7 (1), 1–12. doi:10.1186/s40359-019-0299-7

Forscher, P. S., Lai, C. K., Axt, J. R., Ebersole, C. R., Herman, M., Devine, P. G., et al. (2019). A Meta-Analysis of Procedures to Change Implicit Measures. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 117 (3), 522–559. doi:10.1037/pspa0000160

French, J., Blair-Stevens, C., McVey, D., and Merritt, R. (2010). Social Marketing and Public Health: Theory and Practice . Oxford University Press

Frey, E., and Rogers, T. (2014). Persistence. Pol. Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 1 (1), 172–179. doi:10.1177/2372732214550405

Harackiewicz, J. M., Canning, E. A., Tibbetts, Y., Priniski, S. J., and Hyde, J. S. (2016). Closing Achievement Gaps with a Utility-Value Intervention: Disentangling Race and Social Class. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 111 (5), 745–765. doi:10.1037/pspp0000075

Hartocollis, A., and Bidgood, J. (2015). Racial Discrimination Demonstrations Spread at Universities across the U.S. The New York Times . Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/12/us/racial-discrimination-protests-ignite-at-colleges-across-the-us.html .

Kotler, P., and Armstrong, G. (2001). Principles of Marketing . 9th edition. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Krueger, R. (1994). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kulik, C. T., Pepper, M. B., Roberson, L., and Parker, S. K. (2007). The Rich Get Richer: Predicting Participation in Voluntary Diversity Training. J. Organiz. Behav. 28 (6), 753–769. doi:10.1002/job.444

Kurdi, B., Seitchik, A. E., Axt, J. R., Carroll, T. J., Karapetyan, A., Kaushik, N., et al. (2019). Relationship between the Implicit Association Test and Intergroup Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Am. Psychol. 74 (5), 569–586. doi:10.1037/amp0000364

Lai, C. K., Hoffman, K. M., and Nosek, B. A. (2013). Reducing Implicit Prejudice. Social Personal. Psychol. Compass . 7 (5), 315–330. doi:10.1111/spc3.12023

Lee, N. R., and Kotler, P. (2019). Social Marketing: Changing Behaviors for Good . Sage Publications .

Lefebvre, R. C. (2011). An Integrative Model for Social Marketing. J. Soc. Marketing . 1 (1), 54–72. doi:10.1108/20426761111104437

Lewis, M. A., and Neighbors, C. (2006). Social Norms Approaches Using Descriptive Drinking Norms Education: A Review of the Research on Personalized Normative Feedback. J. Am. Coll. Health . 54, 213–218. doi:10.3200/jach.54.4.213-218

Lowe, M. (2021). Types of Contact: A Field experiment on Collaborative and Adversarial Caste Integration. Am. Econ. Rev. 111 (6), 1807–1844. doi:10.1287/e8861e18-1b80-4134-918b-824c477abe4f

McDonald, R. I., and Crandall, C. S. (2015). Social Norms and Social Influence. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 3, 147–151. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.04.006

McKenzie-Mohr, D. (2011). Fostering Sustainable Behavior: An Introduction to Community-Based Social Marketing . New society publishers .

McKenzie-Mohr, D., and Schultz, P. W. (2014). Choosing Effective Behavior Change Tools. Soc. Marketing Q. 20 (1), 35–46. doi:10.1177/1524500413519257

Miller, D. T., and Prentice, D. A. (2016). Changing Norms to Change Behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 339–361. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015013

Moss-Racusin, C. A., van der Toorn, J., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., and Handelsman, J. (2014). Scientific Diversity Interventions. Science . 343 (6171), 615–616. doi:10.1126/science.1245936

Mousa, S. (2020). Building Social Cohesion between Christians and Muslims through Soccer in post-ISIS Iraq. Science . 369 (6505), 866–870. doi:10.1126/science.abb3153

Murphy, M. C., Gopalan, M., Carter, E. R., Emerson, K. T., Bottoms, B. L., and Walton, G. M. (2020). A Customized Belonging Intervention Improves Retention of Socially Disadvantaged Students at a Broad-Access university. Sci. Adv. 6 (29), eaba4677. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba4677

Murrar, S., Campbell, M. R., and Brauer, M. (2020). Exposure to Peers' Pro-diversity Attitudes Increases Inclusion and Reduces the Achievement gap. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4 (9), 889–897. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-0899-5

Murrar, S., Gavac, S., and Brauer, M. (2017). Reducing Prejudice. Social Psychol. How other People influence our thoughts actions , 361–384.

National Science Foundation (2020). The State of U.S. Science and Engineering 2020. Retreived from https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20201 .

Noon, M. (2018). Pointless Diversity Training: Unconscious Bias, New Racism and agency. Work, Employment Soc. 32 (1), 198–209. doi:10.1177/0950017017719841

O'Keeffe, P. (2013). A Sense of Belonging: Improving Student Retention. Coll. Student J. 47 (4), 605–613.

Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J., and Tetlock, P. E. (2013). Predicting Ethnic and Racial Discrimination: a Meta-Analysis of IAT Criterion Studies. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 105 (2), 171–192. doi:10.1037/a0032734

Paluck, E. L., and Green, D. P. (2009). Prejudice Reduction: What Works? A Review and Assessment of Research and Practice. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 339–367. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607

Paluck, E. L., Porat, R., Clark, C. S., and Green, D. P. (2021). Prejudice Reduction: Progress and Challenges. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 72. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-071620-030619

Pittinsky, T. L., Rosenthal, S. A., and Montoya, R. M. (2011). “Measuring Positive Attitudes toward Outgroups: Development and Validation of the Allophilia Scale,” in Moving beyond prejudice reduction: Pathways to positive intergroup relations. . Editors L. R. Tropp, and R. K. Mallett American Psychological Association , 41–60. doi:10.1037/12319-002

Plant, E. A., and Devine, P. G. (1998). Internal and External Motivation to Respond without Prejudice. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 75 (3), 811–832. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.811

Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., and Moller, S. (2018). Race and Gender Differences in How Sense of Belonging Influences Decisions to Major in STEM. Int. J. STEM Education . 5 (1), 10. doi:10.1186/s40594-018-0115-6

Rhodes, N., Shulman, H. C., and McClaran, N. (2020). Changing Norms: A Meta-Analytic Integration of Research on Social Norms Appeals. Hum. Commun. Res. 46, 161–191. doi:10.1093/hcr/hqz023

Sadker, D., Sadker, M., and Zittleman, K. R. (2009). Still Failing at Fairness: How Gender Bias Cheats Girls and Boys and what We Can Do about it . Revised edition. New York: Charles Scribner.

Scacco, A., and Warren, S. S. (2018). Can Social Contact Reduce Prejudice and Discrimination? Evidence from a Field experiment in Nigeria. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112 (3), 654–677. doi:10.1017/s0003055418000151

Slavin, R. E. (1990). Research on Cooperative Learning: Consensus and Controversy. Educ. Leadersh. 47 (4), 52–54.

Smith, W. A. (2006). Social Marketing: an Overview of Approach and Effects. Inj. Prev. 12 (Suppl. 1), i38–i43. doi:10.1136/ip.2006.012864

Spencer, B., and Castano, E. (2007). Social Class Is Dead. Long Live Social Class! Stereotype Threat Among Low Socioeconomic Status Individuals. Soc. Just Res. 20 (4), 418–432. doi:10.1007/s11211-007-0047-7

Stephan, W. G. (2014). Intergroup Anxiety. Pers Soc. Psychol. Rev. 18 (3), 239–255. doi:10.1177/1088868314530518

Stephens, N. M., Townsend, S. S. M., Markus, H. R., and Phillips, L. T. (2012). A Cultural Mismatch: Independent Cultural Norms Produce Greater Increases in Cortisol and More Negative Emotions Among First-Generation College Students. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 48 (6), 1389–1393. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.008

Strayhorn, T. L. (2012). College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational success for All Students . Routledge . doi:10.4324/9780203118924

CrossRef Full Text

Wade, D. T. (2009). Goal Setting in Rehabilitation: An Overview of what, Why and How. Clin. Rehabil. 23, 291–295. doi:10.1177/0269215509103551

Walsh, G., Hassan, L. M., Shiu, E., Andrews, J. C., and Hastings, G. (2010). Segmentation in Social Marketing. Eur. J. Marketing 44 (7), 1140–1164. doi:10.1108/03090561011047562

Walton, G. M., and Cohen, G. L. (2011). A Brief Social-Belonging Intervention Improves Academic and Health Outcomes of Minority Students. Science . 331 (6023), 1447–1451. doi:10.1126/science.1198364

Walton, G. M., and Cohen, G. L. (2007). A Question of Belonging: Race, Social Fit, and Achievement. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 92 (1), 82–96. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Walton, G. M., and Wilson, T. D. (2018). Wise Interventions: Psychological Remedies for Social and Personal Problems. Psychol. Rev. 125 (5), 617–655. doi:10.1037/rev0000115

Wicker, A. W. (1969). Attitudes versus Actions: The Relationship of Verbal and Overt Behavioral Responses to Attitude Objects. J. Soc. Issues 25 (4), 41–78. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1969.tb00619.x

Wiggan, G. (2007). Race, School Achievement, and Educational Inequality: Toward a Student-Based Inquiry Perspective. Rev. Educ. Res. 77 (3), 310–333. doi:10.3102/003465430303947

Wolf, D. A. P. S., Perkins, J., Butler-Barnes, S. T., and Walker, T. A. (2017). Social Belonging and College Retention: Results from a Quasi-Experimental Pilot Study. J. Coll. Student Development . 58 (5), 777–782. doi:10.1353/csd.2017.0060

Wood, W., and Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of Habit. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 289–314. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Wymer, W. (2011). Developing More Effective Social Marketing Strategies. J. Soc. Marketing . 1 (1), 17–31. doi:10.1108/20426761111104400

Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Murray, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., et al. (2019). A National experiment Reveals where a Growth Mindset Improves Achievement. Nature . 573 (7774), 364–369. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

Keywords: higher educaction, STEM–science technology engineering mathematics, diversity, inclusion, behavior change, intervention

Citation: Moreu G, Isenberg N and Brauer M (2021) How to Promote Diversity and Inclusion in Educational Settings: Behavior Change, Climate Surveys, and Effective Pro-Diversity Initiatives. Front. Educ. 6:668250. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.668250

Received: 15 February 2021; Accepted: 23 June 2021; Published: 08 July 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Moreu, Isenberg and Brauer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Markus Brauer, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Understanding the Influence of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Class on Inequalities in Academic and Non-Academic Outcomes among Eighth-Grade Students: Findings from an Intersectionality Approach

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity, Department of Social Statistics, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

Affiliation Australian National University, Acton, Australia

- Laia Bécares,

- Naomi Priest

- Published: October 27, 2015

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363

- Reader Comments

Socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and gender inequalities in academic achievement have been widely reported in the US, but how these three axes of inequality intersect to determine academic and non-academic outcomes among school-aged children is not well understood. Using data from the US Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten (ECLS-K; N = 10,115), we apply an intersectionality approach to examine inequalities across eighth-grade outcomes at the intersection of six racial/ethnic and gender groups (Latino girls and boys, Black girls and boys, and White girls and boys) and four classes of socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage. Results of mixture models show large inequalities in socioemotional outcomes (internalizing behavior, locus of control, and self-concept) across classes of advantage/disadvantage. Within classes of advantage/disadvantage, racial/ethnic and gender inequalities are predominantly found in the most advantaged class, where Black boys and girls, and Latina girls, underperform White boys in academic assessments, but not in socioemotional outcomes. In these latter outcomes, Black boys and girls perform better than White boys. Latino boys show small differences as compared to White boys, mainly in science assessments. The contrasting outcomes between racial/ethnic and gender minorities in self-assessment and socioemotional outcomes, as compared to standardized assessments, highlight the detrimental effect that intersecting racial/ethnic and gender discrimination have in patterning academic outcomes that predict success in adult life. Interventions to eliminate achievement gaps cannot fully succeed as long as social stratification caused by gender and racial discrimination is not addressed.

Citation: Bécares L, Priest N (2015) Understanding the Influence of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Class on Inequalities in Academic and Non-Academic Outcomes among Eighth-Grade Students: Findings from an Intersectionality Approach. PLoS ONE 10(10): e0141363. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141363

Editor: Emmanuel Manalo, Kyoto University, JAPAN

Received: June 10, 2015; Accepted: October 6, 2015; Published: October 27, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Bécares, Priest. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Data Availability: All ECLS-K Kindergarten-Eighth Grade Public-use File are available from the National Center for Education Statistics website ( https://nces.ed.gov/ecls/dataproducts.asp#K-8 ).

Funding: This work was funded by an ESRC grant (ES/K001582/1) and a Hallsworth Research Fellowship to LB.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The US racial/ethnic academic achievement gap is a well-documented social inequality [ 1 ]. National assessments for science, mathematics, and reading show that White students score higher on average than all other racial/ethnic groups, particularly when compared to Black and Hispanic students [ 2 , 3 ]. Explanations for these gaps tend to focus on the influence of socioeconomic resources, neighborhood and school characteristics, and family composition in patterning socioeconomic inequalities, and on the racialized nature of socioeconomic inequalities as key drivers of racial/ethnic academic achievement gaps [ 4 – 10 ]. Substantial evidence documents that indicators of socioeconomic status, such as free or reduced-price school lunch, are highly predictive of academic outcomes [ 2 , 3 ]. However, the relative contribution of family, neighborhood and school level socioeconomic inequalities to racial/ethnic academic inequalities continues to be debated, with evidence suggesting none of these factors fully explain racial/ethnic academic achievement gaps, particularly as students move through elementary school [ 11 ]. Attitudinal outcomes have been proposed by some as one explanatory factor for racial/ethnic inequalities in academic achievement [ 12 ], but differences in educational attitudes and aspirations across groups do not fully reflect inequalities in academic assessment. For example, while students of poorer socioeconomic status have lower educational aspirations than more advantaged students [ 13 ], racial/ethnic minority students report higher educational aspirations than White students, particularly after accounting for socioeconomic characteristics [ 14 – 16 ]. Similarly, while socio-emotional development is considered highly predictive of academic achievement in school students, some racial/ethnic minority children report better socio-emotional outcomes than their White peers on some indicators, although findings are inconsistent [ 17 – 22 ].

In addition to inequalities in academic achievement, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities also exist across measures of socio-emotional development [ 23 – 26 ]. And as with academic achievement, although socioeconomic factors are highly predictive of socio-emotional outcomes, they do not completely explain racial/ethnic inequalities in school-related outcomes not focused on standardized assessments [ 11 ].

Further complexity in understanding how academic and non-academic outcomes are patterned by socioeconomic factors, and how this contributes to racial/ethnic inequalities, is added by the multi-dimensional nature of socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status is widely recognized as comprising diverse factors that operate across different levels (e.g. individual, household, neighborhood), and influence outcomes through different causal pathways [ 27 ]. The lack of interchangeability between measures of socioeconomic status within and between levels (e.g. income, education, occupation, wealth, neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics, or past socioeconomic circumstances) is also well established, as is the non-equivalence of measures between racial/ethnic groups [ 27 ]. For example, large inequalities have been reported across racial/ethnic groups within the same educational level, and inequalities in wealth have been shown across racial/ethnic that have similar income. It is therefore imperative that studies consider these multiple dimensions of socioeconomic status so that critical social gradients across the entire socioeconomic spectrum are not missed [ 27 ], and racial/ethnic inequalities within levels of socioeconomic status are adequately documented. It is also important that differences in school outcomes are considered across levels of socioeconomic status within and between racial/ethnic groups, so that the influence of specific socioeconomic factors on outcomes within specific racial/ethnic groups can be studied [ 28 ]. However, while these analytic approaches have been identified as research priorities in order to enhance our understanding of the complex ways in which socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity intersect to influence school outcomes, research that operationalizes these recommendations across academic and non-academic outcomes of school children is scant.

In addition to the complexity that arises from race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and intersections between them, different patterns in academic and non-academic outcomes by gender have also received longstanding attention. Comparisons across gender show that, on average, boys have higher scores in mathematics and science, whereas girls have higher scores in reading [ 2 , 3 , 29 ]. In contrast to explanations for socioeconomic inequalities, gender differences have been mainly attributed to social conditioning and stereotyping within families, schools, communities, and the wider society [ 30 – 35 ]. These socialization and stereotyping processes are also highly relevant determining factors in explaining racial/ethnic academic and non-academic inequalities [ 35 , 36 ], as are processes of racial discrimination and stigmatization [ 37 , 38 ]. Gender differences in academic outcomes have been documented as differently patterned across racial/ethnic groups and across levels of socioeconomic status. For example, gender inequalities in math and science are largest among White and Latino students, and smallest among Asian American and African American students [ 39 – 43 ], while gender gaps in test scores are more pronounced among socioeconomically disadvantaged children [ 44 , 45 ]. In terms of attitudes towards math and sciences, gender differences in attitudes towards math are largest among Latino students, but gender differences in attitudes towards science are largest among White students [ 39 , 40 ]. Gender differences in socio-developmental outcomes and in non-cognitive academic outcomes, across race/ethnicity and socio-economic status, have received far less attention; studies that consider multiple academic and non-academic outcomes among school aged children across race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status and gender are limited in the US and internationally.

Understanding how different academic and non-academic outcomes are differently patterned by race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and gender, including within and between group differences, is an important research area that may assist in understanding the potential causal pathways and explanations for observed inequalities, and in identifying key population groups and points at which interventions should be targeted to address inequalities in particular outcomes [ 28 , 46 ]. Not only is such knowledge critical for population level policy and/or local level action within affected communities, but failing to detect potential factors for interventions and potential solutions is argued as reinforcing perceptions of the unmodifiable nature of inequality and injustice [ 46 ].

Notwithstanding the importance of documenting patterns of inequality in relation to a particular social identity (e.g. race/ethnicity, gender, class), there is increasing acknowledgement within both theoretical and empirical research of the need to move beyond analyzing single categories to consider simultaneous interactions between different aspects of social identity, and the impact of systems and processes of oppression and domination (e.g., racism, classism, sexism) that operate at the micro and macro level [ 47 , 48 ]. Such intersectional approaches challenge practices that isolate and prioritize a single social position, and emphasize the potential of varied inter-relationships of social identities and interacting social processes in the production of inequities [ 49 – 51 ]. To date, exploration of how social identities interact in an intersectional way to influence outcomes has largely been theoretical and qualitative in nature. Explanations offered for interactions between privileged and marginalized identities, and associated outcomes, include family and teacher socialization of gender performance (e.g. math and science as male domains, verbal and emotional skills as female), as well as racialized stereotypes and expectations from teachers and wider society regarding racial/ethnic minorities that are also gendered (e.g. Black males as violent prone and aggressive, Asian females as submissive) [ 52 – 57 ]. That is, social processes that socialize and pattern opportunities and outcomes are both racialized and gendered, with racism and sexism operating in intersecting ways to influence the development and achievements of children and youth [ 58 – 60 ]. Socioeconomic status adds a third important dimension to these processes, with individuals of the same race/ethnicity and gender having access to vastly different resources and opportunities across levels of socioeconomic status. Moreover, access to resources as well as socialization experiences and expectations differ considerably by race and gender within the same level of socio-economic status. Thus, neither gender nor race nor socio-economic status alone can fully explain the interacting social processes influencing outcomes for youth [ 27 , 28 ]. Disentangling such interactions is therefore an important research priority in order to inform intervention to address inequalities at a population level and within local communities.

In the realm of quantitative approaches to the study of inequality, studies often examine separate social identities independently to assess which of these axes of stratification is most prominent, and for the most part do not consider claims that the varied dimensions of social stratification are often juxtaposed [ 56 , 61 ]. A pressing need remains for quantitative research to consider how multiple forms of social stratification are interrelated, and how they combine interactively, not just additively, to influence outcomes [ 46 ]. Doing so enables analyses that consider in greater detail the representation of the embodied positions of individuals, particularly issues of multiple marginalization as well as the co-occurrence of some form of privilege with marginalization [ 46 ]. It is important to note that the languages of statistical interaction and of intersectionality need to be carefully distinguished (e.g. intersectional additivity or additive assumptions, versus additive scale and cross-product interaction terms) to avoid misinterpretation of findings, and to ensure appropriate application of statistical interaction to enable the description of outcome measures for groups of individuals at each cross-stratified intersection [ 46 ]. Ultimately this will provide more nuanced and realistic understandings of the determinants of inequality in order to inform intervention strategies.

This study fills these gaps in the literature by examining inequalities across several eighth grade academic and non-academic outcomes at the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. It aims to do this by: identifying classes of socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage from kindergarten to eighth grade; then ascertaining whether membership into classes of socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage differ for racial/ethnic and gender groups; and finally, by contrasting academic and non-academic outcomes at the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender and socioeconomic advantage/disadvantage. Intersecting identities of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic characteristics are compared to the reference group of White boys in the most advantaged socioeconomic category, as these are the three identities (male, White, socioeconomically privileged) that experience the least marginalization when compared to racial/ethnic and gender minority groups in disadvantaged socioeconomic positions.

This study used data on singleton children from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten (ECLS-K). The ECLS-K employed a multistage probability sample design to select a nationally representative sample of children attending kindergarten in 1998–99. In the base year the primary sampling units (PSUs) were geographic areas consisting of counties or groups of counties. The second-stage units were schools within sampled PSUs. The third- and final-stage units were children within schools [ 62 ]. Analyses were conducted on data collected from direct child assessments, as well as information provided by parents and school administrators.

Ethics Statement

This article is based on the secondary analysis of anonymized and de-identified Public-Use Data Files available to researchers via the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). Human participants were not directly involved in the research reported in this article; therefore, no institutional review board approval was sought.

Outcome Variables.

Eight outcome variables, all assessed in eighth grade, were selected to examine the study aims: two measures relating to non-cognitive academic skills (perceived interest/competence in reading, and in math); three measures capturing socioemotional development (internalizing behavior, locus of control, self-concept); and three measures of cognitive skills (math, reading and science assessment scores).

For the eighth-grade data collection, children completed the 16-item Self Description Questionnaire (SDQ) II [ 63 ], where they provided self-assessments of their academic skills by rating their perceived competence and interest in English and mathematics. The SDQ also asked children to report on problem behaviors with which they might struggle. Three subscales were produced from the SDQ items: The SDQ Perceived Interest/Competence in Reading, including four items on grades in English and the child’s interest in and enjoyment of reading. The SDQ Perceived Interest/Competence in Math, including four items on mathematics grades and the child’s interest in and enjoyment of mathematics. And the SDQ Internalizing Behavior subscale, which includes eight items on internalizing problem behaviors such as feeling sad, lonely, ashamed of mistakes, frustrated, and worrying about school and friendships [ 62 ].

The Self-Concept and Locus of Control scales ask children about their self-perceptions and the amount of control they have over their own lives. These scales, adopted from the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988, asked children to indicate the degree to which they agreed with 13 statements (seven items in the Self-Concept scale, and six items in the Locus of Control Scale) about themselves, including “I feel good about myself,” “I don’t have enough control over the direction my life is taking,” and “At times I think I am no good at all.” Responses ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Some items were reversed coded so that higher scores indicate more positive self-concept and a greater perception of control over one’s own life. The seven items in the Self-Concept scale, and the six items in the Locus of Control were standardized separately to a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1. The scores of each scale are an average of the standardized scores [ 62 ].

Academic achievement in reading, mathematics and science was measured with the eighth-grade direct cognitive assessment battery [ 62 ].

Children were given separate routing assessment forms to determine the level (high/low) of their reading, mathematics, and science assessments. The two-stage cognitive assessment approach was used to maximize the accuracy of measurement and reduce administration time by using the child’s responses from a brief first-stage routing form to select the appropriate second-stage level form. First, children read items in a booklet and recorded their responses on an answer form. These answer forms were then scored by the test administrator. Based on the score of the respective routing forms, the test administrator then assigned a high or low second-stage level form of the reading and mathematics assessments. For the second-stage level tests, children read items in the assessment booklet and recorded their responses in the same assessment booklet. The routing tests and the second-stage tests were timed for 80 minutes [ 62 ]. The present analyses use the standardized scores (T-scores), allowing relative comparisons of children against their peers.

Individual and Contextual Disadvantage Variables.

Latent Class Analysis, described in greater detail below, was used to classify students into classes of individual and contextual advantage or disadvantage. Nine constructs, measuring characteristics at the individual-, school-, and neighborhood-level, were captured using 42 dichotomous variables measured across the different waves of the ECLS-K.