Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, wonder woman.

Ever since William Moulton Marston created her in 1941, Wonder Woman has always been at her best when her stories lean into the feminist ethos at her core. When artists treat her compassion as the key to understanding her—rather than her brutality in battle—audiences are privy to a superhero who offers what no other can: a power fantasy that privileges the interiority and desires of women. But film rarely has made room for the fantasies of women on such a grand scale. And in comic adaptations, women can be tough, funny, and self-assured. But rarely are they the architects of their own destiny.

As a longtime Wonder Woman fan, I worried her distinctive edges would be sanded off when it came time for her standalone film. It’s arguably easier to sell Wonder Woman as a vengeful heroine in the vein of countless others, but less distinctive. But early in the film I noticed the terrain that director Patty Jenkins turned to most often in order to create the emotional through-line. It wasn’t the glimmer of a blade or even the picturesque shores of Themyscira, the utopian paradise Wonder Woman calls home. Through moments of quiet verisimilitude and blistering action sequences, Jenkins’ gaze often wisely returns to the face of her lead heroine, Diana ( Gal Gadot ). At times, her face is inquisitive, morose, and marked by fury. But more often than not she wears a bright, open smile that carries the optimism and hope that is true to the character’s long history as well as a much-needed salve from what other blockbusters offer. In turn, “Wonder Woman” isn’t just a good superhero film. It is a sincerely good film in which no qualifiers are needed. It’s inspiring, evocative, and, unfortunately, a bit infuriating for the chances it doesn’t take.

Written by Allan Heinberg , with a story also by Zack Snyder and Jason Fuchs , the story uses a variety of inspiration culled from Wonder Woman’s 76-year history. As a young girl, Diana enjoys the loving protection of the Amazons of Themyscira, a secluded island paradise created by the gods of Olympus. No Amazon is fiercer or more protective than her mother, Queen Hippolyta ( Connie Nielsen ). But Diana longs to be trained in the art of war by her aunt, Antiope (a stellar Robin Wright ). She grows from a kind, young girl into an inquisitive, brave, young woman who never hesitates to helps those in need. Even a man like Captain Steve Trevor (an endlessly charming Chris Pine ), who brings news of World War I when he crash-lands on the island disrupting this all-female sanctuary, gets saved by her. Diana leaves behind the only life she’s ever known, heading to late 1910s London to stop the war she believes is influenced by the god Ares.

Cinematographer Matthew Jensen , production designer Aline Bonetto , and costume designer Lindy Hemming form Themyscira into a gorgeous utopia that utilizes a variety of cultural touchstones. It’s free of the Hellenic influence you’d expect from a story that takes such inspiration from Greek myth with the Amazons creating their home in a way that respects the lush nature around them rather than destroying it. It isn’t sterile either. The scenes set in Themyscira have a dazzling array of colors including the gold of armor, the cerulean blue of the sea that surrounds them, warm creams, and deep browns. Jenkins films many of these scenes in wide shot, reveling in the majestic nature of this culture. Similarly, the history of the Amazons, told in a dense but beautifully rendered backstory by Hippolyta, evokes a painterly quality reminiscent of Caravaggio. Having said that, while “Wonder Woman” has a lot to offer visually, what makes this film so captivating is Gal Gadot and Chris Pine.

Gadot wonderfully inhabits the mix of curiosity, sincerity, badassery, and compassion that has undergirded Wonder Woman since the beginning. Most importantly, she wears her suit, the suit doesn’t wear her. She evokes a classic heroism that is a breath of fresh air and nods to Christopher Reeve ’s approach to Superman from the 1970s. Likewise, Pine matches her hopefulness with a world weariness and sharp sense of humor. He’s more than capable at bringing an emotional complexity to a character most aptly described as a dude-in-distress. There are particularly great scenes at the beginning, as Diana talks about men being unnecessary for female pleasure. Steve seems undone by her presence, which makes the development of their story authentic. Their chemistry is electrifying, making “Wonder Woman” a successful romance and superhero origin story set during one of the most brutal wars.

At their best, blockbusters evoke awe that can be both humbling and thrilling. Think of the first time you saw the T-Rex in “ Jurassic Park ” or the suspense that suffuses all of " Aliens ." “Wonder Woman” excels at this particularly in the earliest chapter set in Themyscira. I felt my heart swell watching Antiope smirk during an intense fight and Hippolyta’s tender scenes with Diana. “Wonder Woman” is like nothing that has come before it in how it joyously displays the camaraderie among women, many of whom are women of color and over 40. It's electrifying watching the Amazons train and talk with each other. These women are fierce and kind, loyal and brave. If anything, I wished the film dwelt in Themyscira a bit longer, since their culture is so poignantly rendered. Also, it was just awesome to see Artemis (Ann J. Wolfe) and Antiope in battle.

Elsewhere, the supporting cast is uneven. The villains—an obsessive German General Ludendorff ( Danny Huston ) and the mad scientist Doctor Maru nicknamed Doctor Poison ( Elena Anaya )—are painted too broadly and given too few details to have a lasting impact. Diana’s comrades that Steve rounds up are similarly crafted with little detail. Charlie ( Ewen Bremner ) is a Scottish sharpshooter, ravaged by what he’s witnessed in the war. Chief ( Eugene Brave Rock ) is a Native American, capitalizing on the war for profit. Sameer ( Saïd Taghmaoui ) is a confidence artist of sorts. But the actors are able to give these characters enough sincerity and wit to make their appearances memorable.

While “Wonder Woman” is an overall light, humorous and hopeful movie, it isn’t afraid of touching on politics. The feminism of the film is sly. It’s seen in moments when characters of color comment on their station in life and Diana faces sexism from powerful men who doubt her intelligence. Of course, the feminism, charming performances, and delightful humor would be nothing without the direction by Patty Jenkins.

Superhero films inherently carry the thrill of seeing these characters come to life and brandish great abilities, but far too often the fight scenes are neither epic nor engaging. So often they’re flatly lit, unimaginatively framed extravaganzas of characters fighting in airplane hangers and other drab surroundings. But what makes “Wonder Woman” so blistering is Jenkins’ distinctive gaze particularly in the fight scenes. Yes, the CGI is at times half-baked, which occasionally would snap me out of the momentum, but, overall, her voice as a director is so distinctive and her handling of the action so deft I was in complete awe. She shows off the great physicality of the Amazons, Diana's included, giving the action full room to breathe without being burdened by excessive editing or an over-reliance on close-ups. She treats action as a dance of sorts, with important characters having their own distinctive styles so that nothing ever feels repetitive. The sequences depicting Themyscira and Diana’s first entry on the battlefield of World War I are particularly exemplary.

Unfortunately, there are several choices that prevent the film from fully inhabiting the unique, feminist aims presented at the beginning. Ares, when he’s finally introduced near the very end, at first seems to be a somewhat clever take on the God of War. He isn’t so much seeking to end the world as create a new one by influencing the darkest aspects of mankind. But then the story tips into being a far more traditional superhero film than it had been previously.

It’s in the third act that the constraints of being part of an extended cinematic universe become apparent. It’s as if the last 30 minutes were cut from another film altogether that sought to create the bombastic, confusing, fiery sort of finale that far too many superhero works hew toward. The third act's approach to Diana’s true origin creates a distinct schism between its sincere feminist aims and the desires of a company that often doesn’t understand why people are drawn to this character in the first place. But there are enough moving touches—like Diana’s last scene with Steve—that prevent the finale from weighing down the film entirely.

Despite its flaws, “Wonder Woman” is beautiful, kindhearted, and buoyant in ways that make me eager to see it again. Jenkins and her collaborators have done what I thought was previously impossible: created a Wonder Woman film that is inspiring, blistering, and compassionate, in ways that honor what has made this character an icon.

Now playing

Simon Abrams

Brian Tallerico

We Were the Lucky Ones

Robert daniels.

Kaiya Shunyata

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire

Matt zoller seitz.

Glitter & Doom

Sheila o'malley, film credits.

Wonder Woman (2017)

Rated PG-13 for sequences of violence and action, and some suggestive content.

141 minutes

Gal Gadot as Diana / Wonder Woman

Chris Pine as Steve Trevor

Connie Nielsen as Hippolyta

Robin Wright as Antiope

Danny Huston as Ludendorff

David Thewlis as Sir Patrick

Said Taghmaoui as Sameer

- Patty Jenkins

Writer (based on the Characters from DC: Wonder Woman created by)

- William Moulton Marston

Writer (story by)

- Zack Snyder

- Allan Heinberg

- Jason Fuchs

Cinematographer

- Matthew Jensen

- Martin Walsh

- Rupert Gregson-Williams

Latest blog posts

Beyoncé and My Daughter Love Country Music

A Poet of an Actor: Louis Gossett, Jr. (1936-2024)

Why I Love Ebertfest: A Movie Lover's Dream

Adam Wingard Focuses on the Monsters

67 Wonder Woman (2017)

Wonder Woman as a Sign of Feminism

by Alanna Martines

The classic DC comic we all know and love is brought to life in Wonder Woman (2017) starring Gal Gadot as the iconic Diana Prince, better known as Wonder Woman. The film serves as an origin story of the beloved hero and follows her journey as she steps into the outside world. Diana is portrayed as a strong, compassionate, determined, and willing to challenge traditional gender roles to become a symbol of female empowerment. The film explores themes of war, sacrifice, and the complexities we face as human beings. With the compelling storytelling and the impactful message, Wonder Woman has become a groundbreaking film, celebrating the strength and quality of women. The film uses its narrative and characters to shed light on DPD issues such as gender inequality, abuse of power, and discrimination. We will be taking a deep dive into the gender equality and feminism seen in Wonder Woman .

Wonder Woman stands as a powerful testament to female empowerment and representation. By showcasing the strength, courage, and compassion of its protagonist, the movie shattered gender stereotypes and celebrated the ideals of women. In a world where women have historically been treated as less than men, feminism emerged as a movement for women’s rights and equality. At the time of the movie, in January of 2017 there was a worldwide protest called The Women’s March. The march aimed to advocate legislation and policies regarding human rights and other issues. Ghaisani writes that “Women have been treated as lower than men ever since in the biological level ”. Throughout history, feminism has led to significant achievements, such as the right to vote and work. However, societal ideals of women, shaped predominantly by men, have persisted. This is particularly evident when examining portrayals of women in comic books, where they are often depicted in skimpy clothing and possess invisible powers, reinforcing traditional gender roles. Wonder Woman challenges these ideas by defying traditional stereotypes and featuring a lead actress from Israel, thereby improving the representation of feminism and women’s empowerment. Ghaisani writes that “Wonder Woman was firstly created by a man, psychologist William Moulton Marston. Even Marston portrays Wonder Woman as how the future ideal woman should be.” Marston believed that women possessed inherent qualities that made them superior to men in many ways.

Wonder Woman subverts the ideals of women by setting Princess Diana on an island where such traditional notions do not exist. The women on the island rely solely on themselves and do not require assistance from men. Cinematography techniques that are used are when Diana is shown climbing the wall and there are close up shots that show her strength. This portrayal challenges the societal construct that positions men as dominant and powerful, and women as weak and submissive. Moreover, the film aligns with real-world efforts towards gender equality, as the United Nations appointed the fictional character Wonder Woman as an Honorary Ambassador for the Empowerment of Women and Girls. This recognition underscores the film’s emphasis on portraying Wonder Woman as powerful, resilient, and independent, going beyond her physical beauty.

In addition to defying traditional ideals of women, Wonder Woman contributes to feminism through its choice of lead actress. Gal Gadot, hailing from Israel, becomes an icon for girls to look up to. Her journey from winning the Miss Israel beauty pageant to serving in the Israel Defense Forces as a combat instructor challenges stereotypes and demonstrates that women can occupy leadership roles. Gadot herself has expressed her belief that everyone should be feminist, emphasizing that feminism is about freedom of choice for all genders. Her casting in the film helps bridge cultural gaps and promotes inclusivity in the realm of superhero representation.

However, it is essential to acknowledge alternative perspectives that critique the film for objectifying women through the male gaze. Some argue that the film employs visual techniques that cater to the male audience and perpetuate the objectification of women. The portrayal of Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman, characterized by her slim figure, fair skin, and revealing costumes, is seen as intentionally flaunting her body. This can seen by having a Wonder Woman dresses in a corset and shorts, emphasizing her body and figure. While the film celebrates feminism in many aspects, it is important to recognize and critique instances where it may inadvertently reinforce traditional gendered expectations.

Despite these criticisms, Wonder Woman remains a significant milestone in promoting female empowerment and representation. Its success at the box office and positive reception among audiences highlight the demand for strong, complex female characters. By featuring a female superhero who possesses agency, strength, and compassion, the film provides a much-needed alternative to the male-dominated superhero genre. It offers a new model of heroism and inspires girls and women to embrace their own power and potential. Moreover, Wonder Woman films contribute to the broader feminist movement by sparking discussions and raising awareness about gender equality. It serves as a catalyst for conversations about representation, female empowerment, and the need for diverse voices in the entertainment industry. The film’s impact extends beyond the screen, inspiring individuals to challenge gender norms and fight for equal rights in their own lives and communities.

Wonder Woman explores the theme of the abuse of power through its portrayal of Ares, the god of war, and the larger context of World War I. Ares represents the embodiment of power and its corrupting influence. He is depicted as a manipulative and malevolent force, fueling the war and manipulating individuals to carry out his destructive agenda. This can be seen by Ares acting as someone who is on the side to help end the war, when in reality, he was the one creating the war. The movie illustrates how power, when misused, can lead to devastating consequences. Ares takes advantage of human vulnerabilities and weaknesses, exploiting their desires for power and control. His actions perpetuate the cycle of violence and suffering, showcasing the destructive nature of unchecked power. By exploring the abuse of power through the character of Ares and the larger context of war, Princess Diana highlights the need for individuals to be mindful of their own power and its potential consequences. It prompts viewers to reflect on the moral implications of power and encourages them to strive for a more just and balanced world.

Additionally, the film touches upon themes of discrimination and prejudice. Diana, as an outsider to the world of men, faces discrimination based on her gender and her origins. She encounters skepticism and disbelief from those who underestimate her abilities and dismiss her contributions. This serves as a commentary on the discrimination faced by marginalized groups and highlights the need to challenge and overcome prejudice. This can be seen throughout the whole movie especially, but a scene that stands out most to me is when Diana is willing to run out to the battlefield in order to stop Ares and save the village of people. Diana’s friends deny the request and instead insist on camping out behind the front line. Diana is furious with this and charges out onto the battlefield, also known as No Man’s Land, by herself. The film puts Wonder Woman in slow motion as she goes onto the field. Additionally, the film emphasizes the power by adding music that is powerful. By doing this, she showed Steve and the rest of the group what she was capable of, while also giving the men a chance to take the front line of Germany.

Wonder Woman , despite some criticisms, serves as a groundbreaking representation of female empowerment and challenges long-standing gender stereotypes. Through the strong and capable character of Diana Prince, the film inspires and empowers audiences, especially women and girls, to believe in their own strength and potential. By defying traditional ideals of women and featuring a lead actress from Israel, the film expands the notion of feminism and offers a diverse and inclusive perspective. While no work is without its flaws, Wonder Woma n contributes significantly to the ongoing dialogue surrounding gender equality and the representation of women in media and popular culture.

Driscoll, Molly. “Why Female Comic Book Fans Are Cheering for ‘Wonder Woman’.(The Culture).” The Christian Science Monitor, 1 June 2017, p. NA. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edscpi&AN=edscpi.A493902825&site =eds-live&scope=site.

Ghaisani, Marinda P. D. “Wonder Woman (2017): An Ambiguous Symbol of Feminism.” Rubikon : Journal of Transnational American Studies , vol. 6, Nov. 2020, p. 12. EBSCOhost, https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db= edsair&AN=edsair.doi.dedup…..ec9d92e44c874885010193dd319d304c&site=eds-live&s cope=site.

Marcus, Jaclyn. “Wonder Woman’s Costume as a Site for Feminist Debate.” Imaginations Journal , vol. 9, no. 2, July 2018, pp. 55–65. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/10.17742/IMAGE.FCM.9.2.6.

Potter, Amandas. “Feminist Heroines for Our Times: Screening the Amazon Warrior in Wonder Woman (1975 – 1979), Xena: Warrior Princess (1995 – 2001) and Wonder Woman (2017).” Thersites. Journal for Transcultural Presences & Diachronic Identities from Antiquity to Date , vol. 7, Nov. 2018. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/10.34679/thersites.vol7.85.

Difference, Power, and Discrimination in Film and Media: Student Essays Copyright © by Students at Linn-Benton Community College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Why Wonder Woman is a masterpiece of subversive feminism

Yes, the new movie sees its titular heroine sort of naked a lot of the time. But the film-makers have still worked to turn sexist Hollywood conventions on their head

T he chances are you will read a feminist takedown of Wonder Woman before you see the film. And you’ll probably agree with it. Wonder Woman is a half-god, half-mortal super-creature; she is without peer even in superhero leagues. And yet, when she arrives in London to put a stop to the war to end all wars, she instinctively obeys a handsome meathead who has no skills apart from moderate decisiveness and pretty eyes. This is a patriarchal figment. Then, naturally, you begin to wonder why does she have to fight in knickers that look like a fancy letterbox made of leather? Does her appearance and its effect on the men around her really have to play such a big part in all her fight scenes? Even my son lodged a feminist critique: if she were half god, he said, she would have recognised the god Ares immediately – unless he were a better god than her (being a male god).

I agree with all of that, but I still loved it. I didn’t love it as a guilty pleasure. I loved it with my whole heart. Wonder Woman, or Diana Prince, as her civilian associates would know her, first appeared as a character in DC Comics in 1941, her creator supposedly inspired by the feminism of the time, and specifically the contraception pioneer Margaret Sanger. Being able to stop people getting pregnant would be a cool superpower, but, in fact, her skills were: bullet-pinging with bracelets; lassoing; basic psychology; great strength and athleticism; and being half-god (the result of unholy congress between Zeus and Hyppolyta). The 1970s TV version lost a lot of the poetry of that, and was just all-American cheesecake. Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman made her cinematic debut last year in Batman v Superman , and this first live-action incarnation makes good on the character’s original premise, the classical-warrior element amped up and textured. Her might makes sense.

Yes, she is sort of naked a lot of the time, but this isn’t objectification so much as a cultural reset: having thighs, actual thighs you can kick things with, not thighs that look like arms, is a feminist act. The whole Diana myth, women safeguarding the world from male violence not with nurture but with better violence, is a feminist act. Casting Robin Wright as Wonder Woman’s aunt, re-imagining the battle-axe as a battler, with an axe, is a feminist act. A female German chemist trying to destroy humans (in the shape of Dr Poison, a proto-Mengele before Nazism existed) might be the most feminist act of all.

Women are repeatedly erased from the history of classical music, art and medicine. It takes a radical mind to pick up that being erased from the history of evil is not great either. Wonder Woman’s casual rebuttal of a sexual advance, her dress-up montage (“it’s itchy”, “I can’t fight in this”, “it’s choking me”) are also feminist acts. Wonder Woman is a bit like a BuzzFeed list: 23 Stupid Sexist Tropes in Cinema and How to Rectify Them. I mean that as a compliment.

Yet Wonder Woman is not a film about empowerment so much as a checklist of all the cliches by which women are disempowered. So it leaves you feeling a bit baffled and deflated – how can we possibly be so towering a threat that Hollywood would strive so energetically, so rigorously, for our belittlement? At the same time, you are conflicted about what the fightback should look like. Because, as every reviewer has pointed out, Wonder Woman is by no means perfect.

The woman who can fight is not new; from Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley in Alien, to Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor in The Terminator, this idea has a long pedigree. Connor was a far-fetched feminist figure because her power was concentrated in her ambivalent maternal love – like a hypothetical tiger mother, which doesn’t do a huge amount for female agency. She is still an accessory for male power, just on the other side of the mother/whore dichotomy. Ripley, being the same gender as her foe, recast action as a cat-fight, with all the sexist bullshit that entails (hot, sweaty woman saying “bitch” a lot – a classic pornography trope).

But the underlying problem is that the male fighter is conceived as an ego ideal for a male audience, who would imagine themselves in the shirt of Bruce Willis or mankini of Superman and get the referred thrill of their heroism. If you are still making the film for a male gaze, the female warrior becomes a sex object, and her fighting curiously random, like pole dancing – movement that only makes sense as display, and even then, only just. That was always the great imponderable of Lara Croft (as she appeared in the video-game, not the film): the listlessness of her combat, the slightly dreamlike quality of it. Even as it was happening, it was hard to remember why. When Angelina Jolie made her flesh, I thought she brought something subversive to the role; something deliberated, knowing and a bit scornful, as though looking into the teenage gamer’s soul and saying: “You don’t know whether that was a dragon, a dinosaur or a large dog. You are just hypnotised by my buttocks.”

The fighter as sex symbol stirs up a snakepit of questions: are you getting off on the woman or the violence? An unbreakable female lead can be liberating to the violent misogynist tendency since the violence against her can get a lot more ultra, and nobody has to feel bad about it, because she’ll win.

This is tackled head on in Wonder Woman. The tension, meanwhile, between the thrill of the action, which is what combat is all about, and the objectification, which is what women are all about, is referenced when Wonder Woman hurls someone across a room and an onlooker says: “I’m both frightened, and aroused.” A word on the fighting: there’s a lot of hurling, tons of lassoing, much less traditional fighting, where people harm one another with punches. This is becoming a sub-genre in films: “the kind of fighting that is ladylike”. It almost always involves bows and arrows, for which, as with so many things, we can thank Jennifer Lawrence in The Hunger Games. The way Lawrence fights is so outrageously adroit and natural that she makes it look as though women have been doing it all along, and men are only learning.

I find it impossible to imagine the feminist action-movie slam-dunk; the film in which every sexist Hollywood convention, every miniature slight, every outright slur, every incremental diss was slain by a lead who was omnipotent and vivid. That film would be long and would struggle for jokes. Just trying to picture it leaves you marvelling at the geological slowness of social progress in this industry, which finds it so hard to create female characters of real mettle, even when they abound in real life. Wonder Woman, with her 180 languages and her near-telepathic insights, would stand more chance of unpicking this baffler than Superman or Batman. But the answer, I suspect, lies in the intersection between the market and the culture; the more an art-form costs, the less it will risk, until the most expensive of them – blockbusters – can’t change at all. In an atmosphere of such in-built ossification, the courage of Wonder Woman is more stunning even than her lasso.

- Wonder Woman

- Superhero movies

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

The Strange, Complicated, Feminist History of Wonder Woman’s Origin Story

This article originally appeared in Vulture .

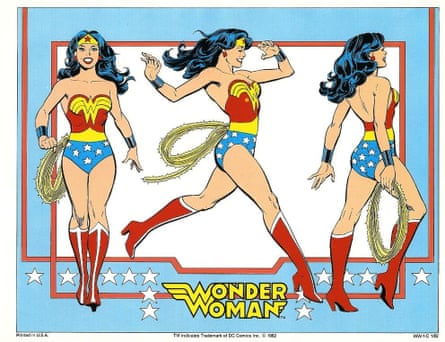

Circling the mug I drink from every day are versions of Wonder Woman’s iconic costumes from her 76-year history. There’s the character at the very beginning, created by William Moulton Marston and drawn by Harry G. Peter in 1941. She’s mid-step as the blue skirt dotted with white stars billows around her. The color scheme and main accoutrements mostly stay the same in each version—gold breastplate, tiara, bulletproof bracelets, the lasso of truth—but just about everything else is open to interpretation. Sometimes her face carries an open smile, other times she grimaces fiercely. Her hair lengthens, her muscles grow more prominent, the hemline rises. The mug is missing several costume changes, including the armored outfit that resembles what she wears in Patty Jenkins’s Wonder Woman , starring Gal Gadot as the Amazonian princess, which is currently dominating the box office. Jenkins’s film marks the first time this legendary character has been in a live-action feature film. It’s also the biggest pop-culture event surrounding the character since the kitschy 1970s series starring Lynda Carter, which for a certain generation remains the foremost image of her in the public imagination. Why has it taken decades to give the longest-running and most well-known female superhero her own film while her male peers have headlined features, animated series, and major comic-book events? It all goes back to her origin story.

Superheroes—particularly those as long-running as Wonder Woman—are inherently mutable. They shift and mold to the time they find themselves in and whichever artists are tasked with bringing them to life. Batman no longer carries a gun. Superman has grown immensely more powerful since his 1938 debut in Action Comics No. 1. But despite how much the characters have changed, they all feel true. Adam West’s goofy 1960s series and Scott Snyder’s more recent take on the character, despite being wildly different, both feel like Batman somehow. Perhaps it’s because images of Superman and Batman have proliferated the cultural consciousness so deeply. Ask laymen and comic diehards alike and you’ll get a neat summation of their origins as well as what they represent. Superman is the last son of Krypton who crash-lands in an idyllic version of the Midwest, inspiring hope when he takes on the mantle. And Batman? We’ve seen Bruce Wayne’s parents die so many times in that fateful alleyway, it goes without saying.

What separates Wonder Woman from her peers in DC’s trinity is that her origin has been adjusted so often, particularly in the last two decades, no one version has had the chance to take hold. In reality though, there are a few key aspects that have remained since Marston created her in 1941. Diana is a princess from a secluded, all-women island paradise now known as Themyscira, which was granted to the Amazons by the Greek gods. She’s the daughter of Queen Hippolyta, and she was molded from clay. The Amazons are a matriarchal society who were meant to have brought the message of peace to Man’s World, but they’ve secluded themselves away from that brutality, creating a society rich with culture, far more advanced than our own, steeped in magic and sisterhood. When Captain Steve Trevor crash-lands on Themyscira, a tournament is held to decide who will return him to Man’s World. Diana wins, and sets off to bring a message of peace to his world, becoming the hero we know as Wonder Woman. This origin is markedly different from her peers given its lack of tragedy (which for women usually comes down to sexualized violence). But it has romance, adventure, and it’s undergirded by a coming-of-age tale about a young woman leaving behind everything she’s ever known to help a world that very well may not accept her. Despite these alluring hooks, Wonder Woman’s origin is typically derided for being too weird, too complicated, too boring , and lacking a central narrative .

In 2013, DC Entertainment chief Diane Nelson was asked by The Hollywood Reporter why Wonder Woman hadn’t had a high-profile adaptation in decades. (Joss Whedon’s feature film attempt felt apart in 2007 due to creative differences; David E. Kelley’s tragic attempt never made it past the pilot stage.) Nelson referred to the character as “tricky,” saying , “She doesn’t have the single, clear, compelling story that everyone knows and recognizes.” The reason Wonder Woman doesn’t have an origin everyone recognizes is because her story hasn’t been told through multiple mediums the way Batman, Superman, and Spider-Man’s have. Nelson isn’t giving the character enough credit, either. Wonder Woman has still managed to reach icon status, which isn’t accidental—it’s indicative of the hunger for female-oriented stories, especially coming-of-age tales, that go against the usual depictions of female strength. In an interview with Entertainment Tonight, director Ava DuVernay said as much about Wonder Woman : “The numbers around the world that that film has done proves that people are thirsty, are hungry, are craving more nuanced [and] full-bodied images of women.” Wonder Woman has partially achieved this status because she’s the longest-running character to communicate such a narrative on a grand scale.

When Marston created Wonder Woman, he was very clear about his intentions . “Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world,” he said. As Jill Lepore mentions in her book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, Marston argued that “the only hope for civilization is the greater freedom, development and equality of women in all fields of human activity.” Wonder Woman isn’t a bloodthirsty warrior á la Xena, but someone who solves problems with compassion rather than a carefully timed roundhouse kick. This puts her in a precarious position in a genre defined by a very particular, at times noxious, power fantasy. In the wake of Marston’s death in 1947, DC Comics didn’t seem to have a handle on Wonder Woman. While the touchstones of her origin remained—being made from clay, the Amazons, Queen Hippolyta, Steve Trevor—the way it was framed changed drastically. Sometimes the Amazons and Themysciran culture were positioned as beacons of hope far more advanced than the rest of the world. Other times, they fell victim to troubling feminist stereotypes, lacking interiority as vengeful warriors, or closed off, emotionally distant fixtures. It was as if the men writing them couldn’t imagine what women would talk about among themselves or the allure of all-women environments. (Sound familiar? ) Over the years, Wonder Woman has been stripped of her powers, turned into a super-spy, and has given up heroics altogether to marry Steve Trevor. Most troublingly, writers have forced her to become a warrior since it’s an easier selling point (but much less distinctive). By far the most regrettable and dramatic shift in her history is rooted in her 2011 reboot, in which she eventually becomes a figure that’s antithetical to everything Wonder Woman stands for: the God of War. The problem has never been Marston’s original origin story or how more recent creators like George Pérez and Greg Rucka have slightly updated it while still leaning into the feminist ethos central to the character. It’s those who have fundamentally changed who her character is over the years.

Due to the fact that she’s so intrinsically tied to the feminist movement, Wonder Woman is also often burdened with having to represent all facets of womanhood in ways other female superheroes, like Black Widow, Storm, and Captain Marvel, have not, which has created a more muddled sense of who she is. Charting the tangled lineage of Wonder Woman’s origin is to chart the history of American feminism itself and how female power is negotiated in a world that abhors it. At the beginning of her history, Wonder Woman carried the echo of the suffragette movement and first-wave feminism. The way her mythos reflected ongoing debates about womanhood only continued from there.

When Ms. magazine first debuted in 1972, it was Wonder Woman who appeared on its cover . She did so again for it’s 40th anniversary , a reminder of just how much the feminist movement and the character itself had, and had not, evolved. Feminist icon Gloria Steinem has long discussed the importance of the character. In 1972, she neatly explained how Wonder Woman has become a locus for feminist discussion and argument more than any other comic character: “Wonder Woman symbolizes many of the values of the women’s culture that feminists are now trying to introduce into the mainstream: strength and self-reliance for women; sisterhood and mutual support among women; peacefulness and esteem for human life; a diminishment both of ‘masculine’ aggression and of the belief that violence is the only way of solving conflicts.”

One of the most fascinating aspects in the wake of Wonder Woman ’s release is the criticism, positive and negative, that demonstrates the unique burden the character faces in regards to feminist expectations. Her politics are so baked into her origin that she’s expected to be all things to all women. A recent Slate essay, “I Wish Wonder Woman Were As Feminist As It Thinks It Is,” demerits other critics for their emotional connection to the recent film. A Wired piece titled “Wonder Woman Overcame Her Origin to Become a Feminist Icon” misconstrues aspects of her story. Throughout her history, Wonder Woman has been either too feminist or not feminist enough. She’s either a wonderful step forward for intersectional portrayals of womanhood or a film that continues the obsession with exalting white womanhood. She’s either a BDSM-tinged pinup or a glorious example of female heroism. No one character and mythos could ever live up to such stringent expectations. These arguments have raged about the character and her origins long before Gal Gadot ever wielded her iconic golden lasso. That Wonder Woman has finally gotten to star in her own live-action film just as the conversations around female power and intersectionality have hit a fever pitch is not surprising to me. The character has always been a vehicle for such discussions, whether it be how she was depowered in the late 1960s, much to the chagrin of Steinem, or her 1987 revamp, which gave the Amazons a backstory that echoed ongoing conversations about sexual violence happening within the second-wave feminist movement.

Looking back at my childhood discovery of Wonder Woman, I realize the reasons I’m drawn to her are the same reasons her origin is heavily critiqued or treated as a problem that certain writers believe only they can ameliorate. Wonder Woman offers what no other superhero can: an essentially female-power fantasy. Close your eyes and imagine an island with achingly gorgeous vistas in which a diverse group of intelligent, strong women have created an immensely more advanced society. No men. No sexism. No capitalist burden to perform that leaves women, especially women of color, vulnerable. At its best, Wonder Woman’s origin is a bold, feminist-minded refutation of the masculine, hyperindividualistic nature of her superhero peers. That it has been heavily criticized, reframed, and rewritten so often isn’t a mark of its failure, but the failure of DC Comics, and perhaps American culture as a whole, to understand and respect female-power fantasies on a larger scale. Wonder Woman has often fallen victim to a company that doesn’t always recognize why readers are drawn to the character. But there are several runs that expand upon her origin and prove Wonder Woman is worthy of her icon status. None of which is better than the arguable gold standard, released in 1987 in the wake of DC Comics’ legendary continuity wide reboot, Crisis on Infinite Earths.

Writers Greg Potter, George Pérez, and Len Wein were handed the difficult task of updating Wonder Woman while staying true to the core of the character Marston created. The first volume, Gods and Mortals , lays the groundwork for her reworked origin. All the mainstays are there, but they’re deepened over the five years Pérez wrote and penciled the comic . What’s most important here is how female-oriented her origin is. Diana is formed out of clay by a woman, given life and power by women, and raised by women. She is able to thrive without the painful experience of sexism. This origin is so meaningful, it has crossed over into other mediums, used for the Justice League series and the animated film Wonder Woman, in which Keri Russell voiced the titular character. That Wonder Woman is considered a “tricky” character is because she contradicts the rather modern notion that heroism is born from tragedy and pain. The version we see during Crisis on Infinite Earths is a great example of how female power need not replicate the bloodthirsty vengeance of male counterparts to be worthwhile. Perhaps no version of Wonder Woman has understood this less than Brian Azzarello’s misguided, offensive take on the character in 2011, during the previous revamp of the DC brand known as New 52 .

While writer Azzarello and artist Cliff Chiang’s Wonder Woman run has been praised in certain corners, it seems to only be done so by people who want her to be something she’s not: a typical heroine defined by brutality more than anything else . Azzarello’s disinterest in the character isn’t a secret. He’s referred to Themyscira as something out of a “Corona commercial.” He derided her as being mere window dressing when it comes to DC’s Trinity . But the worst insults were in the pages of the comics itself. In issue No. 7 of the series, Diana learns that she wasn’t actually made from clay, but gets her power from a man: She is the demigoddess daughter of Zeus. The Amazons aren’t powerful immortals, but actually have sex with sailors to keep their ranks and sell the male children to Hephaestus for weapons. This obliterates the feminist nature of Wonder Woman’s origin and flattens the fascinating weirdness of the character, turning her into the kind of warrior goddess we’ve seen countless times before. It also makes her seem kind of idiotic. How did she not notice what the Amazons were doing before? It’s the sort of gritty upgrade that demonstrates a great misunderstanding and disrespect of the character. As Corrina Lawson wrote for Wired , “Here are the Amazons, who are supposed to represent the best of their gender, now changed into man-hating mass murderers. To say nothing of the fact that Wonder Woman is also viewed as a gay icon and now the biggest group of fictional lesbians are basically evil.” Azzarello’s run lasted for three years, with the character only regaining the respect she deserves thanks to the team of writer Greg Rucka and artists Nicola Scott and Liam Sharp, whose run on the character wrapped up this month. In DC’s latest revamp of their entire brand, Rebirth, Wonder Woman has blessedly been returned to the made-from-clay origin, and the Amazons are now the complex, peace-loving sisterhood that has charmed audiences for generations.

When Rucka was asked in a recent interview why Wonder Woman’s origin was hard to explain, he was insistent that wasn’t the case: “There’s been this really weird fascination with her birth. With Batman and Superman you never go, ‘How were they born?’ That’s been confusing. Her origin’s actually quite simple. She is from a mythological paradise only of women, that is this warrior culture. She leaves her home, never to return, when a stranger crashes on their shores, and heralds a great evil that they have to fight. She’s the one who goes. And she goes willingly, and she abandons everything she’s known to go into this strange new world, with this stranger, to save us all … [I] do think we forget—this moment is huge. If you think about what it means, and what it means in terms of heroism, that she leaves everything she’s ever known—and everything she’s ever known is paradise and immortality—and she does it [out of duty].”

The Wonder Woman film currently in theaters—written by comic writer Allan Heinberg with a story by Zack Snyder, Jason Fuchs, and Heinberg—seems to conflate multiple takes on her origin. In one trailer, she explains to Steve that her mother formed her out of clay and Zeus gave her life. But as the film continues, it becomes clear that Azzarello’s origin is more than just a passing inspiration. This creates a schism within the film itself between the feminist ethos it leans toward and Azzarello’s origin, which nullifies it. That this origin—the more simplistic demigoddess take that ran for only a few years in the comics—will be the first introduction many have to the character’s backstory does her a disservice. (Thankfully, the Amazons aren’t portrayed as the feminist stereotypes Azzarello crafted them as.)

Perhaps the greatest element of Wonder Woman’s origin missing from the film is in the first act, which takes place in Themyscira. For longtime fans of the character, it is immediately noticeable that the contest to choose which Amazon would go to Man’s World is not included, which would have been the perfect opportunity to flesh out the sisterhood among the Amazons. In the film, Hippolyta’s sisters—Antiope (Robin Wright, having the time of her life) and Menalippe (Lisa Loven Kongsli)—are the characters most crucial to Diana’s growth into the hero she becomes. Beginning with the 1987 reboot, it’s Philippus who has been the most important Amazon influence for Diana, aside from her mother. (Artemis, created a few years later in 1994 is also a pivotal presence and simply an amazing character in her own right.) Since her introduction into the comics, Philippus has always been portrayed as a black woman and has become increasingly important to the mythos. (Thanks to Pérez and Rucka, Wonder Woman has also increasingly been defined by her inclusivity, both racially and in regards to sexuality, as she’s finally bisexual in the comics .) In the film, both Artemis and Philippus are played by black women, but their presence, while encouraging, is ultimately fleeting. More broadly, it’s those small moments, with Diana among her fellow Amazons, that I yearned to see given more weight and attention. Their dynamic is what always drew me to Wonder Woman, more than other superheroines whose relationships with other women are rarely treated with such continued importance.

The paucity of female-driven superhero stories represents a larger lack of film and TV shows interested in exploring the nuances of women’s fantasies. This year at Cannes, actress Jessica Chastain spoke passionately about the “disturbing” state of women at the festival . “I do hope that when we include more female storytellers we will have more of the kinds of women that I recognize in my day-to-day life. Ones that are proactive, have their own agencies, don’t just react to the men around them, they have their own point of view,” Chastain said. No matter the canon you’re speaking of—film, television, comics—the same criticism applies. This is why Wonder Woman and her made-from-clay origin feels so radical. She’s a superheroine who isn’t tied to the legacy of a man the way characters like Supergirl are, for better or for worse. She stands on the strength of her own mythos. And her powers and skills were granted primarily by women, not men.

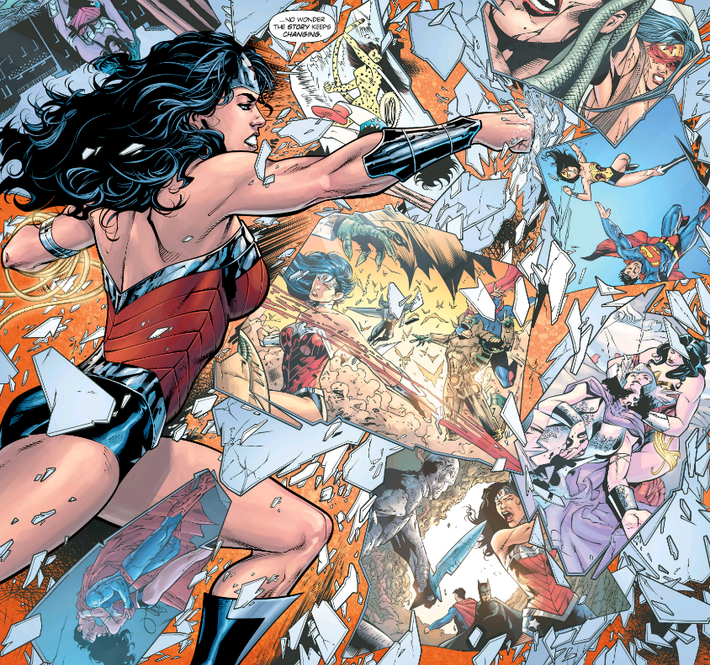

There’s a two-page spread that neatly encapsulates Wonder Woman’s relationship with her own origin in the first issue of Greg Rucka’s The Lies . In it, Wonder Woman wears the version of her outfit that appears in Azzarello’s run. After turning the lasso of truth on herself in hopes of making sense of her life, she learns she’s been deceived about the origin of her previous reboot. This choice comes across as meta-commentary on the fluctuating changes Wonder Woman has dealt with, particularly during Azzarello’s run. She smashes the mirror in front of her. The shards of glass glitter with images from throughout her history—beheading Medusa, fighting with Cheetah, kissing Superman—many of which are from when Azzarello was writing her.

Rucka’s entire run on both The Lies and Year One is about reestablishing Wonder Woman as the hero she is at her best—compassionate, a seeker of truth, and inherently tied to the women who gave her life and raised her. That this version of Wonder Woman is somewhat obscured in the movie makes me worry about the character’s future within the cultural consciousness going forward. In many ways, the film’s inability to be overtly queer and more radically female-centered (it’s Steve whom Diana thinks about in her climactic battle, not her family) represents the conflicts that have always plagued the character’s origin, between her feminist underpinnings, the expectations of fans, and the requirements of a company often uncomfortable within leaning too far into these aspects of this character.

Despite my issues with how the writers tackle the particulars of Diana’s origin, I’d be remiss if I didn’t also acknowledge that Wonder Woman is a vibrant and powerful film. Jenkins’s Wonder Woman does understand the core of the character and what she represents. Her feminism is sly yet apparent, her relationships with the other Amazons are treated with loving care. With the praise the film is receiving and the success of Rucka’s recent comics, my hope is that a new age for Wonder Woman is dawning. Perhaps she is finally entering a point in her history in which what makes her so radical—her unabashed feminism, the female-oriented nature of her origin, her unerring compassion—is built upon rather than derided.

See also: Revisiting the Comics Story That Redefined Wonder Woman

- Contributors

- Valuing Black Lives

- Black Issues in Philosophy

- Blog Announcements

- Climate Matters

- Genealogies of Philosophy

- Graduate Student Council (GSC)

- Graduate Student Reflection

- Into Philosophy

- Member Interviews

- On Congeniality

- Philosophy as a Way of Life

- Philosophy in the Contemporary World

- Precarity and Philosophy

- Recently Published Book Spotlight

- Starting Out in Philosophy

- Syllabus Showcase

- Teaching and Learning Video Series

- Undergraduate Philosophy Club

- Women in Philosophy

- Diversity and Inclusiveness

- Issues in Philosophy

- Public Philosophy

- Work/Life Balance

- Submissions

- Journal Surveys

- APA Connect

Philosophy and Wonder Woman

When I saw the Wonder Woman (2017) film , I felt ambivalent. I have had the opportunity to apply different philosophical lenses to analyze superheroes as a contributor to the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture series , so I wondered if I could dodge the topic of Wonder Woman and feminism in this post. But every discussion online is about this topic, and I also couldn’t stop thinking about it. It was unavoidable. But how could I write from a feminist perspective about this sexy, white, cisgender woman in body armor, wrist cuffs, and high heel boots who carries a lasso that looks like a golden whip? Does Wonder Woman’s physical presentation disqualify her out-of-hand as feminist? And why can’t I get Gal Godot’s dewy eyes out of my head long enough to form a thought? So, I went back to the theater to give it a second chance, and I had four realizations that helped me to begin to think that Wonder Woman is worthy of philosophical reflection with regard to feminism, and that a sequel might make it more interesting.

One : Wonder Woman is not representative of feminism in its diversity. But the absence of that diversity is prompting conversation. This is worth reflecting on. Feminism is for real women and men, inclusive of cisgender and genderqueer identities, who are of different races, ethnicities, sexual orientations, classes, and abilities. Feminism as equality is characterized by dialogue, negotiation, disagreement, listening, and generosity amongst people who are different from each other. Real women and men are talking about Wonder Woman —a lot.

And what they are talking about encourages philosophical reflection about how feminism is not monolithic, and how pop culture can interact with it. I started listening to writers who say that Wonder Woman’s whiteness doesn’t feel representative of all feminists, and that this goes to a deeper lack of representation of people of color in Hollywood (see Noah Berlatsky , Evelyn Diaz , Cameron Glover , Kadeen Griffiths , Monique Jones , and Maya Rupert ). I listened to writers talking about the missed opportunities to really explore LGBTQ issues (see Christina Cauterucci and Kadeen Griffiths ). I listened to those who thought Wonder Woman was a feminist movie (see Kelly Lawler , Melissa Leon , Carmen Rios , Alyssa Rosenburg, Dana Stevens , and Zoe Williams ), and to those who disagreed (see Lewis Beale , Christina Cauterucci, Theresa Harold , and Steve Rose ). I listened not because I want to figure out the final word on the feminist essence of Wonder Woman (as if any such essence is possible), but because people are actually talking about how popular culture is and is not reflecting diversity.

Two: Blockbuster superhero movies belong to a genre that is embedded in larger cultural stereotypes about masculinity and femininity in which the binary itself is a part of the stereotype. I wonder, can Wonder Woman , in the blockbuster superhero genre, do something new or different when gender hierarchies and stereotypes are so powerful and pervasive in that genre? Would we notice or take it seriously if it was trying to? I offer an illustrative example to explore these questions.

Before Wonder Woman began, I watched the trailer for Thor: Ragnarok . Thor is Wonder Woman’s counterpart in every way: a sexy, white, cisgender man whose muscles are bulging and he carries a big hammer. I have seen similar male archetypes in Batman Begins , Man of Steel and many other blockbusters. And I know why it bothers me less when I am watching Thor flex his muscles in slow motion rather than Wonder Woman.

A white, cisgender man cannot be objectified within American culture in the same way as a woman of any race, or men of color. White men are not socially positioned in the same way as women and people of color (and we could also nuance this to recognize other layers of privilege such as white women experiencing white privilege in comparison to women of color). Thor’s subjectivity has never been doubted so it is playful for him to be objectified. Wonder Woman’s subjectivity is always under attack because she is a woman. Objectification threatens Wonder Woman’s subjectivity in a way that it does not threaten Thor’s.

But objectification is not the only issue when we think about the differences between Thor and Wonder Woman. The act of physical fighting itself has deep cultural implications. Wendy Williams argues in “The Equality Crisis…” that mainstream American culture stereotypes men as aggressors—especially in war—and women as mothers and guardians of humanity. What does it mean for Wonder Woman to be a warrior? Is she merely assuming a masculine social role? Can she fight in slow motion without being objectified or vilified for abandoning her feminine duty to defend all life? What will it take for a female superhero to fight in a way that subverts the norms? How will we know when we are seeing it? (I discuss similar themes using Williams’s article in my chapter in Wonder Woman and Philosophy .)

Three: I almost forgot that Wonder Woman is pushing eighty (for a survey of Wonder Woman’s history in graphic novels, see chapters by J. Lenore Wright and Andrea Zanin in Wonder Woman and Philosophy ). It is hard to remember this when watching the 2017 blockbuster iteration of her story. But Wonder Woman is a mature character whose identity has been developed by multiple authors with competing and conflicting narratives that reflect social norms and criticisms of those norms. The 2017 Wonder Woman movie has a heavy burden. In my assessment, it needs to speak across generations, varying levels of familiarity with the superhero, differently positioned viewers, deeply embedded gender stereotypes, and fit into the blockbuster superhero genre. It is also directed by a woman in a genre dominated by men. I am not positive how to think about all of this, but I think it deserves more than just a passing glance. I also hope that it is just the beginning of a conversation that has been decades in the making.

Four: This is the first blockbuster movie dedicated to Wonder Woman, to a female superhero in general, and it is the beginning of Wonder Woman’s story arc. Remembering these important facts, makes the gender dynamics seem less sexist. When I first saw the film, I was bothered when Steve kept telling Diana to follow his lead, that Diana seemed so stereotypically naïve, and that Diana needed to understand that Steve loved her before she actualized her power.

But when I saw the film the second time, I tempered my position with regard to these particular dynamics. In the beginning of Wonder Woman’s story arc, most of the characters, including Wonder Woman herself, do not know she is a superhero goddess. Steve thinks Diana is wrong because she sounds wrong to someone who doesn’t know superheroes are real. Diana was naïve because this was her first interaction with humans outside of Paradise Island (but she learns quickly). Steve’s love did help Diana understand something about herself, but it is worth looking at how this story was told. Steve Trevor is always Wonder Woman’s love interest in the arc of her story. In this iteration, he really did seem to love her and respect her apart from her physical beauty (although he obviously liked that too as he often described her as “distracting”). But notice that his death precludes him playing a role in the sequel and that Wonder Woman mourns him but doesn’t fall apart. This movie is Wonder Woman’s beginning. I am holding back any definitive judgment about Wonder Woman because I don’t know yet what she will become.

My four realizations do not culminate in any grand pronouncements about feminism in Wonder Woman . So I end with a simple observation. A sequel is an opportunity for the director and screen writers to listen to their audiences and to reflect on what they want to do. In the making of Mad Max , the director consulted with feminist/activist/performer Eve Ensler . It only made the movie better. What about reaching out to a woman of color feminist/activist/performer like Anna Deveare Smith (she is obviously not the only option—I am just a huge fan) and asking her how to address the questions about, for example, challenging whiteness in Wonder Woman ? Listening and asking questions can only deepen Wonder Woman’s impact in a sequel. And, by the way, it is what Wonder Woman would do.

Image: Wonder Woman theatrical release poster via Warner Bros. Pictures.

Sarah Donovan

Sarah K. Donovan is an associate professor of philosophy and the interim dean of integrated learning at Wagner College . Her teaching and research interests include community-based, feminist, social, and moral philosophy. She has contributed multiple book chapters to the Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture series .

- Editor: Skye Cleary

- Sarah K Donovan

- Wagner College

- Wonder Woman

RELATED ARTICLES

Treading water, or self-care and success as a graduate student, i don’t read enough, the ancient practice of rest days, finding meaning in moving: my experiences as an aussie grad student, philosophers at the cia an insider’s account, teaching with sci-fi stories: empathic imagination and meta-reflection.

It’s thrilling that Wonder Woman is enjoying the critical and commercial success that it is. But, in some ways it’s also unfair. There is more weight than one film by one director about one woman should bear.

Very good read, but I am curious on your thoughts about how wonder woman was actually created in the beginning by Professor Marston, his wife, and Olive Burne. A very interesting twist to who we look at as Wonder Woman.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

WordPress Anti-Spam by WP-SpamShield

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Advanced search

Posts You May Enjoy

Undrip’s limits on corrective reforms to the basic structure, women in philosophy behaving badly or madly, metaphysics, colin c. smith, coded displacement, what it is like to be a philosopher: simon critchley, on facebook bubbles: greg salmieri’s night of philosophy, has physics made philosophy obsolete (video).

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Wonder Woman: Feminist Origin, Post-Feminist Representation

In this essay, how the character of Wonder Woman shaped the depiction of women in American superhero culture in the past 76 years will be argued. Moreover, there will be an attempt to point out, how formerly feminism and subsequently post-feminism have cultivated the character of Wonder Woman, such that she could become immensely substantive in the masculine world of superheroes.

Related Papers

EuGeStA 19: 176-223.

Walter Penrose Jr

The ancient Amazons, the equals of men, were among the fiercest opponents faced by the ancient Greek heroes Achilles, Heracles, and Theseus. But were they heroes themselves? As the objects of Greek male anxiety, the Amazons were understood to be a threat to Greek civilization, in part due to their refusal to be subjected to the chief institution of patriarchy: marriage. In the Progressive era of the early 20th century, authors repurposed the myths in order to unlock their feminist potential. William Moulton Marston, the inventor of Wonder Woman, used the Amazons in his comics to illustrate his theories of female superiority. Women were more loving than men, Marston argued, and would ultimately therefore make better rulers. While Marston’s feminism was sometimes questioned due to his portrayal of themes of bondage and domination in the Wonder Woman comics, it must be viewed within his larger platform. Marston brought a feminist message to the masses through his deployment of the Amazons to illustrate the potential of women ruling the world through loving dominance. Marston’s star Amazon, Wonder Woman, became the symbol that motivated the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, a vehicle for later authors such as Perez to bring forward third wave feminist messaging to the masses, and, ultimately, became the heroic protagonist of the 2017 film, Wonder Woman. While her revealing costume has been controversial over the years, and Wonder Woman has been subjected to the male gaze, the film, like the comics before them, utilized a female perspective to question the stranglehold that patriarchy has held over the population.

Carrie Morrison

‘Do post-2015 films with feminist protagonists, in genres with patriarchal heritage, represent the current ideals of fourth-wave feminism?’

Ítaca. Quaderns Catalans de Cultura Clàssica

Morena Deriu

The aim of this article is to investigate how the ancient Amazonian myth has been recently remythologised in Patty Jenkins’s Wonder Woman. The analysis of the similarities and differences between the antique and modern myths can indeed shed further light on the gender identity which is promoted in the film and based on the 20th century homonymous comics. Finally, the staging of Themyscira as an all-female society further problematises the theme of the identification and ‘normativitisation’ of the so-called ‘Otherness’.

Susuana Amoah

Since the emergence of feminist film criticism in the 1970s, feminist film scholars, including Jane Gaines (1975), Ella Shohat (1991), bell hooks (1992) and Jackie Stacey (1994), have criticised the ways in which dominant feminist film theory prioritises gendered difference, within its analysis of women’s representation and spectatorship, and marginalises the experiences of women who face intersectional oppression. By positioning gender as its main analytical focus, critics argued that feminist film theory also worked to universalize white, western-centric, colonial perceptions of womanhood.

Nikola Radosevic

This thesis seeks to provide insight into how superheroes are based upon the old heroes of mythology. Superheroes we are most familiar with are typically American, i.e. Western invention. We shall delve into the way the classical heroes are used as a matrix for the creation of superheroes via comparative analysis of mythical heroes such as Hercules and Odysseus and their superhero counterparts: Superman and Batman. Wonder Woman is to illustrate how the concept of a mythical character is adapted to the modern era, creating the superhero of modern times. We shall try to determine how and why it came to re—mythologization in the modern-day America and how its history is mirrored in the superhero narratives. The aforementioned context raises the issue as to what extent their stories criticize, that is to say uphold societal status quo.

Miranda Richardson

This thesis discusses current visual and narrative representation of Western female superheroes. As the concepts of protection and heroism are considered to be inherently masculine, female heroes are often portrayed as contradictory in nature as the author grapples with her status as both woman and hero. This piece ultimately aims to suggest ways of bypassing cultural assumptions and linking signifiers of femininity with heroism.

Neal Curtis

A draft of a paper analysing changes to Wonder Woman's character over her 70 years as a superhero with a view to challenging the latest change that has made her the daughter of Zeus. Currently submitted to the Journal of Popular Culture.

Neal Curtis , Valentina Cardo

Recent developments in superhero comics have seen positive changes to the representation of characters and storylines. In this article, we use examples of the increase in female characters and female-led titles, the swapping of gender from a male character to a female one and the increase in female writers and artists to investigate how the representation of female characters has evolved. We argue that these changes mark an intervention on behalf of female creators in keeping with the theory and practice of third wave feminism. We also argue that this evolution provides a good example of how third wave feminism remains indebted to and continues the important work of second wave feminism. The article explores the important role of intersectionality alongside themes relating to the body and sexuality, violence, solidarity and equality, and girlhood in comics such as Birds of Prey, Harley Quinn, Ms Marvel, Captain Marvel and A-Force.

Queer(ing) Popular Culture, ed. Sebastian Zilles. Special Issue of Navigationen 18.1: (2018): 15-38

Daniel Stein

This essay analyzes the comic book superhero as a popular figure whose queer-ness follows as much from the logic of the comics medium and the aesthetic principles of the genre as it does from a dialectic tension between historically evolving heteronormative and queer readings. Focusing specifically on the superbody as an overdetermined site of gendered significances, the essay traces a shift from the ostensibly straight iterations in the early years of the genre to the more recent appearance of openly queer characters. It further suggests that the struggle over the superbody's sexual orientation and gender identity has been an essential force in the development of the genre from its inception until the present day.

RELATED PAPERS

Transformative Works and Cultures

Matt Yockey

Goutam Majhi

ImageText: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies

Chamara Moore

Marco Favaro

Panic at the Discourse

E. Scherzinger

Sarah Zaidan

Marcos Rafael Cañas Pelayo

Rachel Allison

York University

Anna F Peppard

SFRA Review

Ramzi Fawaz , Justin Hall

Feminist Review

Helen M Kinsella

Journal of Popular Culture 40.2

Aaron Taylor

Kelly F Marcus

The Kennesaw Journal of Undergraduate Research

Angelica E Phelps

Tatiana L . Botero Barthel

Beth Taylor-Thomas

João Pedro Fernandes Gomes

Journal of Popular Culture

Wonder Woman

Ages of Heroes, Eras of Men: Superheroes and the American Experience.

Amanda Murphyao

Courtney Weida

Michael D Kennedy

Cory Albertson

Grace Gipson

Houman Sadri

Fantastika Journal

Meriem R Lamara (PhD)

Ramzi Fawaz

Matthew Freeman

John Sharples

DIOTIMA'S A JOURNAL OF NEW READINGS

Sanil M Neelakandan

Fantastika Journal: Performing Fantastika

Adele Hannon

Jade Dillon

Sebastian Bartosch

Mervi Miettinen

Journal of Graphic Novels & Comics

Andrew Spieldenner

Andrea Gilroy

Laura Mattoon D'Amore

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Things you buy through our links may earn Vox Media a commission.

The Strange, Complicated, Feminist History of Wonder Woman’s Origin Story

Circling the mug I drink from every day are versions of Wonder Woman’s iconic costumes from her 76-year history. There’s the character at the very beginning, created by William Moulton Marston and drawn by Harry G. Peter in 1941. She’s mid-step as the blue skirt dotted with white stars billows around her. The color scheme and main accoutrements mostly stay the same in each version — gold breastplate, tiara, bulletproof bracelets, the lasso of truth — but just about everything else is open to interpretation. Sometimes her face carries an open smile, other times she grimaces fiercely. Her hair lengthens, her muscles grow more prominent, the hemline rises. The mug is missing several costume changes, including the armored outfit that resembles what she wears in Patty Jenkins’s Wonder Woman , starring Gal Gadot as the Amazonian princess, which is currently dominating the box office. Jenkins’s film marks the first time this legendary character has been in a live-action feature film. It’s also the biggest pop-culture event surrounding the character since the kitschy 1970s series starring Lynda Carter, which for a certain generation remains the foremost image of her in the public imagination. Why has it taken decades to give the longest-running and most well-known female superhero her own film while her male peers have headlined features, animated series, and major comic-book events? It all goes back to her origin story.

Superheroes — particularly those as long-running as Wonder Woman — are inherently mutable. They shift and mold to the time they find themselves in and whichever artists are tasked with bringing them to life. Batman no longer carries a gun. Superman has grown immensely more powerful since his 1938 debut in Action Comics No. 1. But despite how much the characters have changed, they all feel true. Adam West’s goofy 1960s series and Scott Snyder’s more recent take on the character, despite being wildly different, both feel like Batman somehow. Perhaps it’s because images of Superman and Batman have proliferated the cultural consciousness so deeply. Ask laymen and comic diehards alike and you’ll get a neat summation of their origins as well as what they represent. Superman is the last son of Krypton who crash-lands in an idyllic version of the Midwest, inspiring hope when he takes on the mantle. And Batman? We’ve seen Bruce Wayne’s parents die so many times in that fateful alleyway, it goes without saying.

What separates Wonder Woman from her peers in DC’s trinity is that her origin has been adjusted so often, particularly in the last two decades, no one version has had the chance to take hold. In reality though, there are a few key aspects that have remained since Marston created her in 1941. Diana is a princess from a secluded, all-women island paradise now known as Themyscira, which was granted to the Amazons by the Greek gods. She’s the daughter of Queen Hippolyta, and she was molded from clay. The Amazons are a matriarchal society who were meant to have brought the message of peace to Man’s World, but they’ve secluded themselves away from that brutality, creating a society rich with culture, far more advanced than our own, steeped in magic and sisterhood. When Captain Steve Trevor crash-lands on Themyscira, a tournament is held to decide who will return him to Man’s World. Diana wins, and sets off to bring a message of peace to his world, becoming the hero we know as Wonder Woman. This origin is markedly different from her peers given its lack of tragedy (which for women usually comes down to sexualized violence). But it has romance, adventure, and it’s undergirded by a coming-of-age tale about a young woman leaving behind everything she’s ever known to help a world that very well may not accept her. Despite these alluring hooks, Wonder Woman’s origin is typically derided for being too weird, too complicated, too boring , and lacking a central narrative .

In 2013, DC Entertainment chief Diane Nelson was asked by The Hollywood Reporter why Wonder Woman hadn’t had a high-profile adaptation in decades. (Joss Whedon’s feature film attempt felt apart in 2007 due to creative differences; David E. Kelley’s tragic attempt never made it past the pilot stage.) Nelson referred to the character as “tricky,” saying , “She doesn’t have the single, clear, compelling story that everyone knows and recognizes.” The reason Wonder Woman doesn’t have an origin everyone recognizes is because her story hasn’t been told through multiple mediums the way Batman, Superman, and Spider-Man’s have. Nelson isn’t giving the character enough credit, either. Wonder Woman has still managed to reach icon status, which isn’t accidental — it’s indicative of the hunger for female-oriented stories, especially coming-of-age tales, that go against the usual depictions of female strength. In an interview with Entertainment Tonight, director Ava DuVernay said as much about Wonder Woman : “The numbers around the world that that film has done proves that people are thirsty, are hungry, are craving more nuanced [and] full-bodied images of women.” Wonder Woman has partially achieved this status because she’s the longest-running character to communicate such a narrative on a grand scale.

When Marston created Wonder Woman, he was very clear about his intentions . “Wonder Woman is psychological propaganda for the new type of woman who should, I believe, rule the world,” he said. As Jill Lepore mentions in her book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, Marston argued that “the only hope for civilization is the greater freedom, development and equality of women in all fields of human activity.” Wonder Woman isn’t a bloodthirsty warrior á la Xena, but someone who solves problems with compassion rather than a carefully timed roundhouse kick. This puts her in a precarious position in a genre defined by a very particular, at times noxious, power fantasy. In the wake of Marston’s death in 1947, DC Comics didn’t seem to have a handle on Wonder Woman. While the touchstones of her origin remained — being made from clay, the Amazons, Queen Hippolyta, Steve Trevor — the way it was framed changed drastically. Sometimes the Amazons and Themysciran culture were positioned as beacons of hope far more advanced than the rest of the world. Other times, they fell victim to troubling feminist stereotypes, lacking interiority as vengeful warriors, or closed off, emotionally distant fixtures. It was as if the men writing them couldn’t imagine what women would talk about among themselves or the allure of all-women environments. (Sound familiar? ) Over the years, Wonder Woman has been stripped of her powers, turned into a super-spy, and has given up heroics altogether to marry Steve Trevor. Most troublingly, writers have forced her to become a warrior since it’s an easier selling point (but much less distinctive). By far the most regrettable and dramatic shift in her history is rooted in her 2011 reboot, in which she eventually becomes a figure that’s antithetical to everything Wonder Woman stands for: the God of War. The problem has never been Marston’s original origin story or how more recent creators like George Pérez and Greg Rucka have slightly updated it while still leaning into the feminist ethos central to the character. It’s those who have fundamentally changed who her character is over the years.

Due to the fact that she’s so intrinsically tied to the feminist movement, Wonder Woman is also often burdened with having to represent all facets of womanhood in ways other female superheroes, like Black Widow, Storm, and Captain Marvel, have not, which has created a more muddled sense of who she is. Charting the tangled lineage of Wonder Woman’s origin is to chart the history of American feminism itself and how female power is negotiated in a world that abhors it. At the beginning of her history, Wonder Woman carried the echo of the suffragette movement and first-wave feminism. The way her mythos reflected ongoing debates about womanhood only continued from there.

When Ms. magazine first debuted in 1972, it was Wonder Woman who appeared on its cover . She did so again for it’s 40th anniversary , a reminder of just how much the feminist movement and the character itself had, and had not, evolved. Feminist icon Gloria Steinem has long discussed the importance of the character. In 1972, she neatly explained how Wonder Woman has become a locus for feminist discussion and argument more than any other comic character: “Wonder Woman symbolizes many of the values of the women’s culture that feminists are now trying to introduce into the mainstream: strength and self-reliance for women; sisterhood and mutual support among women; peacefulness and esteem for human life; a diminishment both of ‘masculine’ aggression and of the belief that violence is the only way of solving conflicts.”