ING’s agile transformation

Established businesses around the world and across a range of sectors are striving to emulate the speed, dynamism, and customer centricity of digital players. In the summer of 2015, the Dutch banking group ING embarked on such a journey, shifting its traditional organization to an “agile” model inspired by companies such as Google, Netflix, and Spotify. Comprising about 350 nine-person “squads” in 13 so-called tribes, the new approach at ING has already improved time to market, boosted employee engagement, and increased productivity. In this interview with McKinsey’s Deepak Mahadevan, ING Netherlands chief information officer Peter Jacobs and Bart Schlatmann, who, until recently, was the chief operating officer of ING Netherlands, explain why the bank needed to change, how it manages without the old reporting lines, and how it measures the impact of its efforts.

The Quarterly : What prompted ING to introduce this new way of working?

Bart Schlatmann biography

Born October 18, 1969, in Bloemendaal, Netherlands

Holds a master’s degree in economic science from Erasmus University Rotterdam

(1995–2017)

ING Netherlands

Chief operating officer

Board member of Bruna, Dutch Payments Association, and WestlandUtrecht Bank

Member of the supervisory board of Interhyp Germany

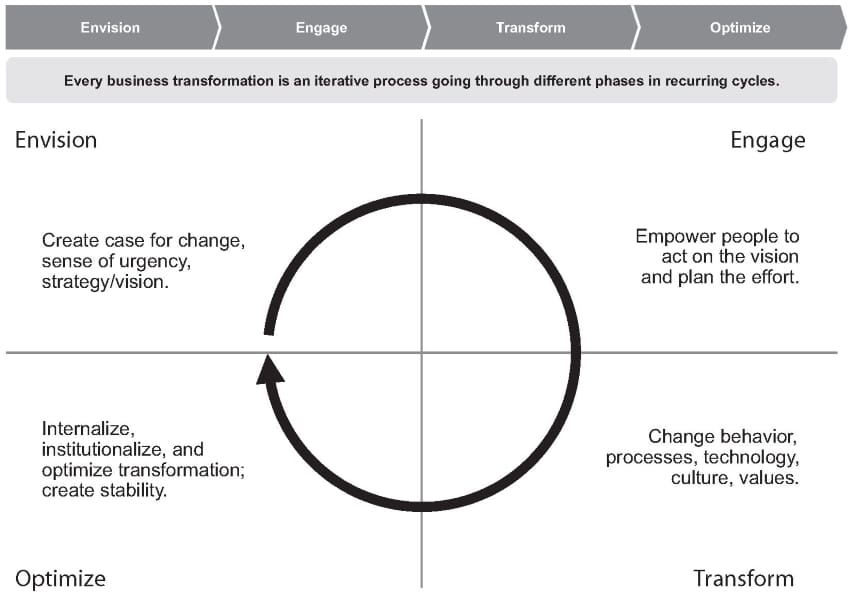

Bart Schlatmann: We have been on a transformation journey for around ten years now, but there can be no let up. Transformation is not just moving an organization from A to B, because once you hit B, you need to move to C, and when you arrive at C, you probably have to start thinking about D.

In our case, when we introduced an agile way of working in June 2015, there was no particular financial imperative, since the company was performing well, and interest rates were still at a decent level. Customer behavior, however, was rapidly changing in response to new digital distribution channels, and customer expectations were being shaped by digital leaders in other industries, not just banking. We needed to stop thinking traditionally about product marketing and start understanding customer journeys in this new omnichannel environment . It’s imperative for us to provide a seamless and consistently high-quality service so that customers can start their journey through one channel and continue it through another—for example, going to a branch in person for investment advice and then calling or going online to make an actual investment. An agile way of working was the necessary means to deliver that strategy.

The Quarterly : How do you define agility?

Bart Schlatmann: Agility is about flexibility and the ability of an organization to rapidly adapt and steer itself in a new direction. It’s about minimizing handovers and bureaucracy, and empowering people. The aim is to build stronger, more rounded professionals out of all our people. Being agile is not just about changing the IT department or any other function on its own. The key has been adhering to the “end-to-end principle” and working in multidisciplinary teams, or squads, that comprise a mix of marketing specialists, product and commercial specialists, user-experience designers, data analysts, and IT engineers—all focused on solving the client’s needs and united by a common definition of success. This model [see exhibit] was inspired by what we saw at various technology companies, which we then adapted to our own business.

The Quarterly : What were the most important elements of the transformation?

Peter Jacobs biography

Born May 8, 1975, in Heerlen, Netherlands

Holds a PhD in systems engineering from Delft University of Technology

(2013–present)

Chief information officer

Director application management

McKinsey & Company

Associate partner and consultant

(2015–present)

Member of the supervisory board of Equens, a European payment processor

(2015, 2014)

Appeared in the Goudhaantjes top 100, a list of Dutch management talent under 45

Peter Jacobs: Looking back, I think there were four big pillars. Number one was the agile way of working itself. Today, our IT and commercial colleagues sit together in the same buildings, divided into squads, constantly testing what they might offer our customers, in an environment where there are no managers controlling the handovers and slowing down collaboration.

Number two is having the appropriate organizational structure and clarity around the new roles and governance. As long as you continue to have different departments, steering committees, project managers, and project directors, you will continue to have silos—and that hinders agility.

The third big component is our approach to DevOps 1 1. The integration of product development with IT operations. and continuous delivery in IT. Our aspiration is to go live with new software releases on a much more frequent basis—every two weeks rather than having five to six “big launches” a year as we did in the past. The integration of product development and IT operations has enabled us to develop innovative new product features and position ourselves as the number-one mobile bank in the Netherlands.

Finally, there is our new people model. In the old organization, a manager’s status and salary were based on the size of the projects he or she was responsible for and on the number of employees on his or her team. In an agile performance-management model , there are no projects as such; what matters is how people deal with knowledge. A big part of the transformation has been about ensuring there is a good mix between different layers of knowledge and expertise.

The Quarterly : What was the scope of this transformation? Where did you start, and how long did it take?

Bart Schlatmann: Our initial focus was on the 3,500 staff members at group headquarters. We started with these teams—comprising previous departments such as marketing, product management, channel management, and IT development—because we believed we had to start at the core and that this would set a good example for the rest of the organization.

We originally left out the support functions—such as HR, finance, and risk—the branches, the call centers, operations, and IT infrastructure when shifting to tribes and squads. But it doesn’t mean they are not agile; they adopt agility in a different way. For example, we introduced self-steering teams in operations and call centers based on what we saw working at the shoe-retailer Zappos. These teams take more responsibility than they used to and have less oversight from management than previously. Meanwhile, we have been encouraging the sales force and branch network to embrace agility through daily team stand-ups and other tactics. Functions such as legal, finance, and operational risk are not part of a squad per se, as they need to be independent, but a squad can call on them to help out and give objective advice.

It took about eight or nine months from the moment we had written the strategy and vision, in late 2014, to the point where the new organization and way of working had been implemented across the entire headquarters. It started with painting the vision and getting inspiration from different tech leaders. We spent two months and five board off-sites developing the target organization with its new “nervous system.” In parallel, we set up five or six pilot squads and used the lessons to adapt the setup, working environment, and overall design. After that, we were able to concentrate on implementation—selecting and getting the right people on board and revamping the offices, for example.

The Quarterly : Was agility within IT a prerequisite for broader organizational change?

Peter Jacobs: Agility within IT is not a prerequisite for a broader transformation, but it certainly helps. At ING, we introduced a more agile way of working within IT a few years ago, but it was not organization-wide agility as we understand it today, because it did not involve the business. You can certainly start in IT and gradually move to the business side, the advantage of this being that the IT teams can test and develop the concept before the company rolls it out more widely. But I think you could equally start with one value stream, let’s say mortgages, and roll it out simultaneously in the business and in IT. Either model can work.

What you can’t do—and that is what I see many people do in other companies—is start to cherry pick from the different building blocks. For example, some people formally embrace the agile way of working but do not let go of their existing organizational structure and governance. That defeats the whole purpose and only creates more frustration.

The Quarterly : How important was it to try to change the ING culture as part of this transformation?

Bart Schlatmann: Culture is perhaps the most important element of this sort of change effort. It is not something, though, that can be addressed in a program on its own. We have spent an enormous amount of energy and leadership time trying to role model the sort of behavior—ownership, empowerment, customer centricity—that is appropriate in an agile culture. Culture needs to be reflected and rooted in anything and everything that we undertake as an organization and as individuals.

For instance, one important initiative has been a new three-week onboarding program, also inspired by Zappos, that involves every employee spending at least one full week at the new Customer Loyalty Team operations call center taking customer calls. As they move around the key areas of the bank, new employees quickly establish their own informal networks and gain a deeper understanding of the business.

We have also adopted the peer-to-peer hiring approach used by Google. For example, my colleagues on the board selected the 14 people who report to me. All I have is a right of veto if they choose someone I really can’t cope with. After thousands of hires made by teams using this approach at every level in the organization, I have never heard of a single veto being exercised—a sure sign that the system is working well. It’s interesting to note, too, that teams are now better diversified by gender, character, and skill set than they were previously. We definitely have a more balanced organization.

A lot is also down to the new way we communicate and to the new office configuration: we invested in tearing down walls in buildings to create more open spaces and to allow more informal interaction between employees. We have a very small number of formal meetings; most are informal. The whole atmosphere of the organization is much more that of a tech campus than an old-style traditional bank where people were locked away behind closed doors.

The Quarterly : Was a traditional IT culture an impediment to the transformation?

Peter Jacobs: In IT, one of the big changes was to bring back an engineering culture, so there’s now the sense that it’s good to be an engineer and to make code. Somehow over the years, success in IT had become a question of being a good manager and orchestrating others to write code. When we visited a Google IO conference in California, we were utterly amazed by what we saw and heard: young people talking animatedly about technology and excitedly discussing the possibilities of Android, Google Maps, and the like. They were proud of their engineering skills and achievements. We asked ourselves, “Why don’t we have this kind of engineering culture at ING? Why is it that large enterprises in Holland and Western Europe typically just coordinate IT rather than being truly inspired by it?” We consciously encouraged people to go back to writing code—I did it myself—and have made it clear that engineering skills and IT craftsmanship are what drive a successful career at ING.

The Quarterly : Can you say more about the companies that inspired you?

Peter Jacobs: We came to the realization that, ultimately, we are a technology company operating in the financial-services business. So we asked ourselves where we could learn about being a best-in-class technology company. The answer was not other banks, but real tech firms.

If you ask talented young people to name their dream company from an employment perspective, they’ll almost always cite the likes of Facebook, Google, Netflix, Spotify, and Uber. The interesting thing is that none of these companies operate in the same industry or share a common purpose. One is a media company, another is search-engine based, and another one is in the transport business. What they all have in common is a particular way of working and a distinctive people culture. They work in small teams that are united in a common purpose, follow an agile “manifesto,” interact closely with customers, and are constantly able to reshape what they are working on.

Spotify, for example, was an inspiration on how to get people to collaborate and work across silos—silos still being a huge obstacle in most traditional companies. We went to visit them in Sweden a few times so as to better understand their model, and what started as a one-way exchange has now become a two-way exchange. They now come to us to discuss their growth challenges and, with it, topics like recruitment and remuneration.

The Quarterly : Without traditional reporting lines, what’s the glue that holds the organization together?

Bart Schlatmann: Our new way of working starts with the squad. One of the first things each squad has to do is write down the purpose of what it is working on. The second thing is to agree on a way of measuring the impact it has on clients. It also decides on how to manage its daily activities.

Squads are part of tribes, which have additional mechanisms such as scrums, portfolio wall planning, and daily stand-ups to ensure that product owners are aligned and that there is a real sense of belonging. Another important feature is the QBR [quarterly business review], an idea we borrowed from Google and Netflix. During this exercise, each tribe writes down what it achieved over the last quarter and its biggest learning, celebrating both successes and failures and articulating what it aims to achieve over the next quarter—and, in that context, which other tribe or squad it will need to link up with. The QBR documents are available openly for all tribes: we stimulate them to offer input and feedback, and this is shared transparently across the bank. So far, we have done four QBRs and, while we are improving, we still have to make them work better.

In the beginning, I think the regulators were at times worried that agile meant freedom and chaos; that’s absolutely not the case. Everything we do is managed on a daily basis and transparent on walls around our offices.

The Quarterly : Can traditional companies with legacy IT systems really embrace the sort of agile transformation ING has been through?

Peter Jacobs: I believe that any way of working is independent of what technology you apply. I see no reason why an agile way of working would be affected by the age of your technology or the size of your organization. Google and ING show that this has nothing to do with size, or even the state of your technology. Leadership and determination are the keys to making it happen.

The Quarterly : Are some people better suited to agile operating approaches than others?

Bart Schlatmann: Selecting the right people is crucial. I still remember January of 2015 when we announced that all employees at headquarters were put on “mobility,” effectively meaning they were without a job. We requested everyone to reapply for a position in the new organization. This selection process was intense, with a higher weighting for culture and mind-sets than knowledge or experience. We chose each of the 2,500 employees in our organization as it is today—and nearly 40 percent are in a different position to the job they were in previously. Of course, we lost a lot of people who had good knowledge but lacked the right mind-set; but knowledge can be easily regained if people have the intrinsic capability.

Peter Jacobs: We noticed that age was not such an important differentiator. In fact, many whom you may have expected to be the “old guards” adapted even more quickly and more readily than the younger generation. It’s important to keep an open mind.

The Quarterly : How would you quantify the impact of what has been done in the past 15 months?

Bart Schlatmann: Our objectives were to be quicker to market, increase employee engagement, reduce impediments and handovers, and, most important, improve client experience. We are progressing well on each of these. In addition, we are doing software releases on a two- to three-week basis rather than five to six times a year, and our customer-satisfaction and employee-engagement scores are up multiple points. We are also working with INSEAD, the international business school, to measure some of these metrics as a neutral outsider.

The Quarterly : Do you see any risks in this agile model?

Peter Jacobs: I see two main risks. First, agility in our case has been extremely focused on getting software to production and on making sure that people respond to the new version of what they get. If you are not careful, all innovations end up being incremental. You therefore have to organize yourself for a more disruptive type of innovation—and you can’t always expect it to come out of an individual team.

Second, our agile way of working gives product owners a lot of autonomy to collect feedback from end users and improve the product with each new release. There is a risk that people will go in different directions if you don’t align squads, say, every quarter or six months. You have to organize in such a way that teams are aligned and mindful of the company’s strategic priorities.

The Quarterly : What advice would you give leaders of other companies contemplating a similar approach?

Bart Schlatmann: Any organization can become agile, but agility is not a purpose in itself; it’s the means to a broader purpose . The first question you have to ask yourself is, “Why agile? What’s the broader purpose?” Make sure there is a clear and compelling reason that everyone recognizes, because you have to go all in—backed up by the entire leadership team—to make such a transformation a success. The second question is, “What are you willing to give up?” It requires sacrifices and a willingness to give up fundamental parts of your current way of working—starting with the leaders. We gave up traditional hierarchy, formal meetings, overengineering, detailed planning, and excessive “input steering” in exchange for empowered teams, informal networks, and “output steering.” You need to look beyond your own industry and allow yourself to make mistakes and learn. The prize will be an organization ready to face any challenge.

Peter Jacobs is the chief information officer of ING Netherlands; Bart Schlatmann , who left ING in January 2017 after 22 years with the group, is the former chief operating officer of ING Netherlands. This interview was conducted in October 2016 by Deepak Mahadevan, a partner in McKinsey’s Brussels office .

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Fintechs can help incumbents, not just disrupt them

Agility: It rhymes with stability

Why agility pays

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Agile project management

- Project management

- Business management

- Process management

How Project Managers Can Stay Relevant in Agile Organizations

- Jeff Gothelf

- May 10, 2021

Agile at Scale

- Darrell K. Rigby

- Jeff Sutherland

- From the May–June 2018 Issue

Agility Hacks

- Amy C. Edmondson

- Ranjay Gulati

- From the November–December 2021 Issue

It’s Time to End the Battle Between Waterfall and Agile

- Antonio Nieto-Rodriguez

- October 10, 2023

To Build an Agile Team, Commit to Organizational Stability

- Elaine Pulakos

- Robert B. Kaiser

- April 07, 2020

Better Project Management

- Antonio Nieto Rodriguez

- Bent Flyvbjerg

- November 01, 2021

How HR Can Become Agile (and Why It Needs To)

- June 19, 2017

4 Ways Silicon Valley Changed How Companies Are Run

- Andrew McAfee

- November 14, 2023

The Agile Family Meeting

- Bruce Feiler

- June 26, 2020

For an Agile Transformation, Choose the Right People

- Heidi K. Gardner

- Alia Crocker

- From the March–April 2021 Issue

How Learning and Development Are Becoming More Agile

- Jon Younger

- October 11, 2016

Bring Agile to the Whole Organization

- November 14, 2014

Case Study: Should I Pitch a New Project-Management System?

- Denis Dennehy

- From the January–February 2024 Issue

Purposeful Business the Agile Way

- Darrell Rigby

- Steve Berez

- From the March–April 2022 Issue

Why Science-Driven Companies Should Use Agile

- Alessandro Di Fiore

- Kendra West

- Andrea Segnalini

- November 04, 2019

How We Finally Made Agile Development Work

- October 11, 2012

Your Agile Project Needs a Budget, Not an Estimate

- Debbie Madden

- December 29, 2014

Using Sprints to Boost Your Sales Team's Performance

- Prabhakant Sinha

- Arun Shastri

- Sally E. Lorimer

- Samir Bhatiani

- July 20, 2023

Embracing Agile

- Hirotaka Takeuchi

- From the May 2016 Issue

How Machine Learning Will Transform Supply Chain Management

- Narendra Agrawal

- Morris A. Cohen

- Rohan Deshpande

- Vinayak Deshpande

- From the March–April 2024 Issue

HP 3D Printing (C)

- Joan Jane Marcet

- December 19, 2019

Bus Uncle Chatbot - Creating a Successful Digital Business (D)

- Yuet Nan Wong

- Siu Loon Hoe

- May 26, 2021

HP 3D Printing (D)

Changing the landscape at arcane: squad structure.

- David Loree

- Fernando Olivera

- February 13, 2023

Meta: Digitally Transforming Workforce Management at Scale and with Agility

- Munir Mandviwalla

- Laurel Miller

- Larry Dignan

- August 07, 2023

The Year in Tech, 2023: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business Review

- Harvard Business Review

- Beena Ammanath

- Michael Luca

- Bhaskar Ghosh

- October 25, 2022

The Year in Tech, 2025: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business Review

- October 08, 2024

The Year in Tech, 2022: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business Review

- Larry Downes

- Jeanne C. Meister

- David B. Yoffie

- Maelle Gavet

- October 26, 2021

Bengaluru Airport: Crisis Leadership through a Pandemic

- Somnath Baishya

- February 08, 2022

Facilitating Digital Development with Agile User Stories

- June 01, 2023

Transport Solutions: TCS Helps its Transformation to an Agile Enterprise

- Abhoy K Ojha

- September 01, 2023

Product-Market Alignment

- Panos Markou

- Rebecca Goldberg

- A. Morgan Kelly

- April 18, 2022

What are Agile Teams?

- Tsedal Neeley

- February 15, 2021

HP 3D Printing (B)

Eric hawkins leading agile teams @ digitally-born appfolio (a).

- Paul Leonardi

- Michael Norris

- June 26, 2019

OneBlood and COVID-19: Building an Agile Supply Chain, Epilogue

- Raina Gandhi

- October 19, 2021

Harvard Business Review Sales Management Handbook: How to Lead High-Performing Sales Teams

- October 22, 2024

The Year in Tech, 2024: The Insights You Need from Harvard Business Review

- David De Cremer

- Richard Florida

- Ethan Mollick

- Nita A. Farahany

- October 24, 2023

ING Bank: Creating an Agile Organisation

- Julian Birkinshaw

- Scott Duncan

- August 31, 2016

Agile Transformation of Raiffeisenbank: Culture First

- Stanislav Shekshnia

- Anna Avital Basner

- March 20, 2022

A Look at Risk from Classical Project Management

- Brian Vanderjack

- August 10, 2015

Popular Topics

Partner center.

- Become an Expert

Guide To Agile Transformation: Plans, Challenges And Case Studies

Article Snapshot

This knowledge is brought to you by Olga Rudenko , just one of the thousands of top transformation consultants on Expert360. Sign up free to hire freelancers here, or apply to become an Expert360 consultant here.

Table of Contents

What Is Agile?

Why is agile transformation worth it, why not agile, the agile transformation plan.

- A Template For An Agile Roadmap?

- Agile philosophy is built on four principles/themes: people over process, product over process, customer input and embracing constant changeThe reason why many tech and non-tech companies go for transform to agile, is that it helps to build better products and better culture

- There is an argument that agile does not suit every situation. However, it is always useful to think whether philosophy still applies, though not all tools of agile.

- We have looked at how agile was introduced and developed in three contexts: digital businesses, large companies needing to drive tech innovation and a consumer goods company driving change through an agency relationship

- The key to a successful agile transformation is to test that all elements of the influence model are addressed: role modelling by executive team, compelling story of why do it, supporting staff through training and structural changes to process and incentives

Now when you hear agile, you think of the way of working more generally, though the origins of agile go to redefining a software development process. In 2001, seventeen leading US developers got together and verbalised for the first time what Agile meant in the Agile Manifesto .

An easy way to get your head around Agile is to start with its four values.

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools : this is not to be confused with no process at all. While there is definitely an agile process, it is very fluid and is driven by individuals who form the team delivering a product.

- Working software over documentation : getting to the working product first at the expense of documenting and explaining how you got there, or getting everyone on board with how the best way to get there. The idea of MVP (minimal viable product) or prototype is a similar concept in the product world: get a working version to a customer as soon as possible to learn and refine.

- Customer collaboration over contract : the concept of putting the customer first is not new. It has existed in marketing and traditional product development for decades. Agile, however, was the first theory to explicitly put the customer in the middle of the software development process. A combination of these two values - working product and continuous customer input means that a much better version of a product is created via multiple iterations.

- Responding to change over following a plan : in agile where you start with your product idea is not where you will finish. Given that customer feedback and continuous learning guides the process, the outcome is bound to change. The change is not only internal or customer driven. Sometimes market situations change or projects have more or less time or money available.

In the tech world of Silicon Valley, agile has graduated to dual track development process. It guides both software development and product development. In dual track an effective digital product team has two processes running alongside:

- Discovery : finding the best way to solve a customer problem through constant MVP validation

- Delivery: building and iterating on the validated MVP

The main goal of discovery is to validate as many feasible ideas as possible before they get to delivery. Delivery is a very expensive resource: good software development teams are expensive and good products do take time to build. Dual track embraces the four values of agile. It also helps to clarify roles between product leaders and engineers while maintaining co-creation and collaboration. Four values are one component of agile philosophy. Another big part of agile is its process and tools. Agile tools, such as Kanban boards, stand up meetings, retrospectives, are well documented and explained elsewhere. We will focus on why and when to go for agile, and go through a few cases

The best argument for using Agile is that it has a fairly proven track record. The largest global agile survey reports that 98% of companies said that their organisation has realised success from agile development practice. It is also no wonder that the largest and fastest growing companies in the world - Google, Apple, Uber, AirBnB - epitomise agile values at scale.

While agile was born in tech, non-tech companies are widely embracing these concepts and seeing measurable results as well. For instance, NPR used Agile to reduce programming costs by up to 66% . REI is using agile principles in its marketing to drive higher ROI on their marketing spend. The value of using Agile can be narrowed down to two things: better product and a better culture. Adobe had an interesting experiment in 2012 of splitting its 26 teams into agile/ scrum and non-agile driven. They measured results by asking teams how they felt in relation to building better products and culture. They found significant improvements for agile teams.

Case study: Adobe moving to Scrum

While the value of agile is widely accepted, there are still arguments that agile should in some cases be considered with caution. HBR and Bain have defined five conditions where agile is not going to be set up for success. Personally, I struggle to find many examples of valid situations where at least the four values of agile do not hold true. Are challenges that require no innovation, no customer input and are not worth the learning gained from mistakes really worth overcoming? However, there may be cases where elements ofthe agile process and its tools may not be the most effective way of managing the process. For instance, large projects with hundreds of people involved in them may need a bit more than just a scrum board to communicate the team's progress towards the goal for stakeholders funding the process.

To understand the recipe for a successful agile transformation and implementation, we will look into three different contexts:

- Agile values or process have been put in place early on: it is very often the case with digital business. We will look into Redbubble & Seek for insight

- Agile had to be introduced as a disruption to more traditional project management and culture. Both Telstra, and AusPost had to do it, though used quite different ways of getting there

- Agile was introduced through agent relationship and adopted gradually, in the example of Cadbury in Australia

We also need to note that the concept of agile is used loosely here to expand from purely a software development process to agile transformation strategy and product development, and leading innovation more generally.

1. Early adopters - Seek and Redbubble

It is always much easier if some of the agile values have been a part of the company philosophy to begin with. Seek, one of the leading jobs marketplace in the world, has always been a customer centric company. Therefore, agile philosophy was easy to adopt. In the early days of the company’s life, not all practices were agile. Kanbans, daily stand ups and retros really became an everyday life for Seek in the last 5-7 years. Redbubble, the world's largest marketplace of independent art printed on demand, was also started with agile values at its heart. Martin Hoskin, the founder, by that time, had already started two successful digital businesses. The other co-founders were also living and breathing human centric design and lean start-up values. As the company grew these values translated into more formalised and universally accepted agile processes. Now every tech team and most of the non-tech teams in Redbubble run Trello boards, do daily stand-ups and bi-weekly retrospectives. A few practices make both of these companies successful in running agile driven businesses.

Agile Values Are Company Values

For both Seek and Redbubble, customer first mentality is reflected in their values. Seek simply expresses it as Customer comes first. For Redbubble, the notion of a customer is slightly more complex. All three of its agents - artists, consumers and suppliers can be interpreted as customers. Redbubbles expresses the customer first mentality as only doing things that benefit the marketplace ecosystem - so all customers of the marketplaces are gaining value. Another agile value - individuals over processes - is also explicitly expressed in both companies. One of the three Seek principles guiding performance reviews is collaboration and quality of solving the problem, not just getting to a solution in an individual fashion. Lastly, both companies embrace change and making mistakes mentality. Andrew Bassett, Seek’s founder, lamented the gutlessness of modern CEOs: “It seems if CEOs make a mistake now, for the most part, they lose their job. It seems to be easier for them just to do nothing,"

Rolemodeling by Leadership

It is not enough to put agile values on a piece of paper and hope that people in the company will adopt them at some point. One of the most effective ways of encouraging and embedding agile values is for the top leaders in the company to be living and breathing these. For instance, Redbubble COO Barry Newstead would often be seen wearing variations of different shirts with “Always make mistakes”. Michael Ilczynski, Head of ANZ for Seek, is almost guaranteed to ask a question of “What customer problem are we solving here?”, if the proposed project does not clearly articulate it.

Best Practice Sharing & Coaching

One last thing to note is that both companies invest in spreading the learnings of how to use agile tools best. Seek does it in a more formal way by making sure that every team goes through Agile induction. Seek also has an agile coach that helps teams to set up those practices and facilitates best practice sharing. Redbubble has a more organic way of sharing what works best. Teams often invite ‘outsider’ team leaders to run their retrospectives. This helps team members see a new way of running the process but also get insight into how to solve specific challenges differently.

2. Self-disrupting giants - Telstra and AusPost

Not everyone has been set up with an agile philosophy at its core. In fact, the majority of Australian large companies acknowledge that their cultures have been formed by a very different set of values. However, the strategic importance of agile to innovation and market leadership makes the case for change. Telstra, one of the top 10 most valuable companies in Australia by market cap, has been on the journey to innovation for a while. Its ex-CEO David Thodey has been an active role model of the value of customer centricity and taking risks. In the last 5 years, Telstra has actively experimented with running its product innovation through a number of options - venture fund, JVs, incubators or self-disrupting start-ups. AusPost is one of the oldest companies in Australia, an employer of over 40,000 people and is owned by the government. You could not imagine a more challenging context for agile transformation. However, under the leadership of its ex-CEO Ahmed Fahour and the team he hired, AusPost has made an impressive leap and is currently leading a number of cutting edge innovations, including a competitor product to Amazon Prime. Not dissimilar to Telstra, AusPost is doing that structurally by introducing customer innovation focused business units. Telstra and AusPost set up their innovation units in quite different ways. Telstra has had more success with a start-up/venture funded model with a range of forms:

- Telstra Ventures was set up in 2011 and since then invested in 40 tech companies, a lot of which became closely integrated into Telstra. Telstra Ventrues is also a top 20 global corporate VC fund.

- Telstra JVs with other companies to create disruption. Proquo, a JV with NAB, is a marketplace for small businesses to trade services with each other.

- They have set up an accelerator programme - Muru-D, to which all Telstra employees have frequent access to observe how small businesses innovate.

- Telstra more directly instils the agile practices by forming a JV with a software development company Pivotal to bring up Telstra to start-up speeds of product development.

AusPost has driven innovation and the move to agile philosophy in a more integrated way. They have set up a Digital Identity and Delivery Center in 2012 to explicitly drive agile and innovation. It has taken four years but early results are starting to show. Most of us are now able to experience daily updates on parcel delivery vs none at all in the past. Three key success factors stand out despite the difference in the form: support from executives, instilling a start-up environment and bringing in new leadership.

Executive Support

The drive for agile and customer centric innovation comes from the very top. Both Telstra and Auspost CEOs have been personally behind each of the projects - whether it was Telstra Ventures or AusPost Digital Delivery Center. They have dedicated time, financial resources and focus of their leadership to have this topic as a priority on their top team agenda. In words of Amelia Crook, an experienced product leader with Seek, Martha Stewart, Redbubble and Flippa experiences behind her, “a successful agile transformation has to have executive support, it’s a whole business transformation, not just a delivery team. Trust becomes super important when old systems of reporting (which gave the illusion of certainty) are replaced with agile teams working around challenges rather than solutions”.

Run it as a Startup

All of the divisions have initiatives aiming to drive agile culture and innovation had to be established and run like start-ups. It is not enough to isolate them structurally. While they needed to have executive support to make them happen, they also needed to succeed or fail in their own right. In the case of AusPost, it was more a clear expectation that the Digital Delivery Center achieves measurable results - specifically speed of development. In the case of Telstra, the companies were literally shut down if they did not perform. Writing off a $330 million investment in a video platform Ooyala is just one of the examples.

Bring New Leadership

Even though the change was led by the existing CEOs and executives, the actual team to run these initiatives was very often brought in externally. AusPost has been a hiring powerhouse for ex-strategy consultants, digital leaders and start-up founders for the last 3-4 years. Telstra often acqui-hired start-up talent like in the case of Pivotal. In the case of Telstra, the relationship was set up with this new breed of leaders to give them an opportunity to be successful. While like a start-up founder they were left to succeed or fail, they were also given considerable protection from corporate politics or bureaucracy.

3. Agent of change - Cadbury

Sometimes the best introduction of agile is more gentle than setting up a new ‘agile’ division or JV. In the case of Cadbury in Australia, it was a relationship with its digital agencies that let its technology teams get a flavour of what agile practices were like and their benefits. Alick Hyde, currently heading Digital for Total Tools, a $350m franchise of tool stores across Australia, used to be a project lead for Cadbury. His first project with them was something not very core to the business - their fundraiser site. The agency team worked with Cadbury tech teams for 9 months. Icon Inc, the agency that Alick was part of, ran all of its client projects as agile and already had experience educating the clients on what to expect. At the end of the project, Cadbury has referred to the experience as extremely positive and rewarding.

“They loved the fact that we were able to change things around and adjust requirements that would benefit the end customer. They saw so much value in running things slightly differently”, Alick reflected.

The Template For A Successful Agile Transformation

Amazingly a lot of people still approach a move to agile in a ‘waterfall way’. Agile transformation roadmap is the most searched term on google on agile transformation. Despite the idea of a fixed roadmap in its classic sense is anti-agile. To get started on an agile transformation journey, it is important to understand what are the necessary elements to drive is. The influence model introduced by McKinsey in 2003 stands the test of time as a leading framework to manage any change.

McKinsey Influence model:

- Role modelling - through all the case examples discussed in this article, CEO and executive support were key to driving agile transformations. Support behind the scenes is not enough. Leaders have to be seen living and breathing the values daily. Any inconsistency or contradiction undermines the credibility of the entire effort.

- Fostering understanding - telling a compelling story of why that makes sense to everyone is important. For companies like Redbubble and Seek, it was about embedding agile values into their company values from the get go. For, Telstra and AusPost it was about the urgency of the case for change and showing what good could look like through acquisitions, JVs or new people brought in. Understanding of why agile works can come from external sources in a less intrusive way like it did in case of Cadbury.

- Developing skills and talent - making sure that the teams are set up for success is key. The solution could be more organic and light touch like in Redbubble, where teams were encouraged to share what already worked. It can be more guided with agile workshops and coaches like in Seek. It can be immersive: Telstra's Muru-D incubator was set up to help those completely new to agile see the way it works for small businesses.

- Reinforcing formal mechanisms - helping to institutionalise and encourage desired behaviours through either formal structures or incentives:

Such structures can be quite explicit - new entities set up as in case of Telstra Ventures and AusPost’s Digital Delivery.

- Agile values can be ingrained in performance reviews - Seek’s collaborative value as one of the key three.

- The way the company runs its core processes can also be supportive of agile transformation - for Redbubble replacing a classic top-down annual planning process with more collaborative bottom-up vision & key results-driven planning.

Whether the company is living and breathing agile values or is just starting the journey, the principles are the same. It is about finding which of the four elements and in what form will be most effective.

Get our insights into what’s happening in business and the world of work; interesting news, trends, and perspectives from our Expert community, and access to our data & trend analysis. Be first in line to read The 360˚ View by subscribing below.

Hire exceptional talent in under 48 hours with Expert360 - Australia & New Zealand's #1 Skilled Talent Network.

In-Depth: The Evidence-Based Business Case For Agile

- Twitter for Christiaan Verwijs

- LinkedIn for Christiaan Verwijs

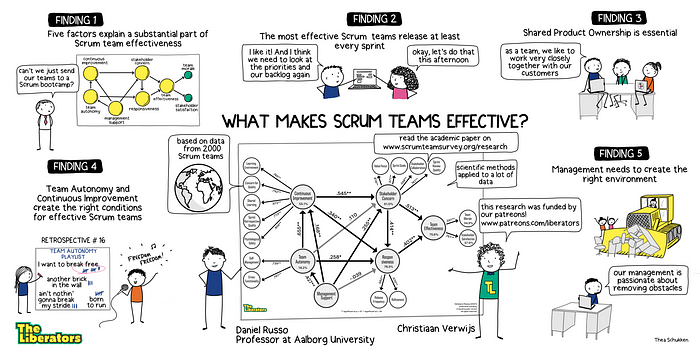

What is the business case for Agile teams? Is it really that important that they are autonomous, able to release frequently, interact closely with stakeholders and spend all that time on continuous improvement? Or is all that just hype? Or maybe even counterproductive?

Yes, we believe all these things are important. And so does probably everyone else in our community. But what is the evidence we have for this? What proof do we have that we aren’t just selling a modern equivalent of snake oil? We think we do well to base our beliefs about Agile more on evidence . This allows us to test our beliefs and also makes our case stronger in case they are supported.

This post is our attempt to bring an evidence-based perspective to the business case of Agile teams. We will share results from scientific studies that we located through Google Scholar . And we share results from our own analyses based on actual data from stakeholders and Scrum teams that we collected through the Scrum Team Survey .

This post is part of our “in-depth” series . Each post discusses scientific research that is relevant to our work with Scrum and Agile teams. We hope to contribute to more evidence-based conversations in our community and a stronger reliance on robust research over personal opinions.

A working definition of Agile and Stakeholders

Before we begin, we need to define some of the terms we will use throughout this post. The first term is Stakeholder . Throughout this post, we define them as “all users, customers, and other people or groups who have a clear stake in the outcomes of what this team produces, and invest money, time or both in making sure that happens”. So this excludes people who have an opinion about the product but don’t stand to lose anything when the team fails.

The second term I’d like to define is Agile or agility . What do we actually mean when we talk about an “Agile team”? In its broadest sense, we mean that these teams practice the principles of the Agile Manifesto . But this is still rather vague. We could say that these teams practice Agile methodologies, like Scrum or XP, and are therefore Agile. But adherence to a framework or prescribed process does not guarantee agility. In fact, we’ve written the Zombie Scrum Survival Guide specifically to shine a light onto all those teams who think they have checked all the boxes of the Scrum framework, and are still not moving.

“Adherence to a framework or prescribed process does not guarantee agility.”

I prefer a process-based definition of agility. This definition answers the question: “What kind of processes typically happen in Agile teams that distinguish them from non-Agile teams?”. We worked with Prof. Daniel Russo of the University of Aalborg to answer this question with data from almost 2.000 Scrum teams. In a scientific study , we identified five core processes — or factors— that happen in and around Agile teams at varying levels of quality:

- Teams work to be as responsive as possible through automation, refinement, and a high(er) release frequency.

- Teams show concern for the needs of their stakeholders by collaborating with them closely and making sure that what is valuable to them is represented in their work and goals.

- Teams engage in continuous improvement to improve where they can through frequent reflection, shared learning, and creating a psychologically safe environment.

- Teams expand and use their autonomy to manage their work and bring their skills together in the most effective ways.

- In the immediate environment of Scrum teams, management supports what teams do and helps them where possible.

Although we used Scrum teams for our investigation, these processes are generic enough to apply to Agile teams in general. We collected the data through our Scrum Team Survey . This tool uses a validated and scale-based questionnaire to allow teams to diagnose and improve their process in an evidence-based way. You can use the free version for individual teams.

For this post, we used a sample of 1.963 Scrum teams and 5.273 team members. The sample was cleaned of fake and careless responses and corrected for social desirability where relevant. Our sample includes teams from all sectors, sizes, and regions.

Finding #1: Teams Vary Widely In Their Actual Agility

In our sample of 1.963 Scrum teams, we observed a wide range of scores on the five core processes of agility. We calculated an overall agility score for teams and categorized them into three buckets — low, moderate, and high — for easier interpretation. The histogram below shows the differences visually:

There are two caveats to this histogram. First, the cutoffs for low, moderate, and high agility are fairly arbitrary. In reality, agility is obviously a continuum that teams traverse. Second, there is some circularity because we calculate the overall agility of a team as an aggregate of the five core processes. So it is not surprising that the scores improve as teams become more Agile.

However, the histogram illustrates nicely the size of this increase, which is both significant for all differences (p<.001) and highly substantial. It also illustrates well how all processes improve, and not just one or two. They seem to be connected. The results also affirm that calling yourself a Scrum team — as the teams in this sample mostly did — is no guarantee of actual agility. At the same time, we can clearly see that many Scrum teams are Agile.

“It is clear from these results that identifying yourself as an Agile or Scrum team is no guarantee of actual agility.”

So we know now have a better sense of the differences between the quality of the core processes at different “levels” of agility. However, the key question is whether this actually makes a difference in important business outcomes. Are more Agile teams indeed better at producing important business outcomes than less Agile teams?

“Are more Agile teams indeed better at producing important business outcomes than fewer Agile teams?”

Finding #2: Agile Teams Have More Satisfied Stakeholders

Ultimately, we believe that a strong business case lies with how effectively Agile teams can serve the needs of stakeholders, like users, customers, and other people with a clear stake. There is clearly a strong economic incentive for organizations to keep stakeholders happy, as they are the people who pay for, or use, their products.

But do Agile teams have more satisfied stakeholders than less Agile teams? Fortunately, the Scrum Team Survey allows teams to ask their stakeholders to evaluate their outcomes. We ask stakeholders to evaluate this on four dimensions: quality, responsiveness, release frequency, and team value. For this analysis, we use the evaluations of 857 stakeholders for 241 teams. 49% of these represented users, 28% customers, and 22% internal stakeholders.

We can statistically test the hypothesis that teams are increasingly able to satisfy their stakeholders as their Agility increases. For this, we used a simple statistical technique called multiple regression analysis. We entered the overall stakeholder satisfaction as the predicted value, and the five core processes as predictors. The regression model was significant (p <.001) and explained 29.2% of the observed variance in stakeholder satisfaction. This may not seem that high, but values above 20% are considered “very strong” in the social sciences. The scatterplot shown below shows the distribution of teams based on stakeholder satisfaction (vertical) and Agility (horizontal). Each dot represents a team:

A scatterplot and the results from a regression analysis may not be intuitive for many readers, especially those not familiar with statistics. So we also created a histogram by plotting the least Agile teams against the most Agile teams. It is a bit simplistic, but it illustrates the differences more dramatically.

There is one caveat to these results. The scatterplot suggests that teams are more likely to invite stakeholders when they are already quite Agile. This makes sense; non-Agile teams may interact less with their stakeholders and thus see fewer opportunities to invite them to evaluate the outcomes. But this means we lack data from teams that score very low on agility. However, it is likely that the difference would be even stronger if such stakeholders were included.

The bottom line is clear though. Agile teams have more satisfied stakeholders than less Agile teams. This effect is also very strong. So high autonomy, high responsiveness, high continuous improvement, high stakeholder concern, and high management support clearly go hand-in-hand with higher stakeholder satisfaction. Simply put; if organizations want more satisfied stakeholders, investing in the five processes of agility is a very clear evidence-based recommendation.

“The bottom line of the results is clear though. Agile teams have more satisfied stakeholders than non-Agile teams.”

Finding #3: Agile Teams Have Higher Morale

The second part of our business case can be made by looking at how agility affects team members. Employees are the “human capital” of modern-day organizations. Happy employees allow companies to save money on absenteeism, sick leave, and the hiring and onboarding of new employees to replace others who leave the company.

So it is helpful to look at the morale of teams. Team morale, or ‘esprit de corps’, reflects how motivating and purposeful the work feels to a team ( Manning, 1991 ). Many meta-analyses — statistical aggregations of datasets from many other empirical studies — have shown strong benefits of high morale and its corollaries, like job satisfaction. It reduces turnover and absenteeism among employees ( Hacket & Guion, 1989 ). It also increases performance ( Judge et. al., 2001 ) and proactive behavior ( LePine, Erez & Johnson, 2002 ).

“So there is a clear economic incentive for companies to encourage high morale in teams.”

But is morale higher in Agile teams than in less-Agile teams? To answer this question, we analyzed data from 1.976 teams and 5.273 team members from the Scrum Team Survey .

So with this data, we ran another linear multiple regression analysis with team morale as the predicted value, and the five core factors as predictors. The resulting model was significant (p <.001) and explained 44.6% of the observed variance in team morale. This is a strong result when we consider that values above 20% are already considered “very strong” in the social sciences. The scatterplot is shown below. Each dot represents a team. The line reflects the optimal regression line. It is clearly visible that as the agility of a team increases (vertical), team morale also increases (horizontal).

We also created a histogram to plot the morale of the most Agile teams against that of the least Agile teams in our database, which is more visually clear:

So what do these numbers mean in practice? Generally speaking, morale will be much higher in Agile teams compared to less Agile teams. The morale in the highest-scoring teams (on agility) is almost twice as high as in the lowest-scoring teams. So high autonomy, high responsiveness, high continuous improvement, high stakeholder concern, and high management support clearly go hand-in-hand with high team morale.

“Generally speaking, morale will be much higher in Agile teams compared to non-Agile teams.”

Intermission: A Note On Causality

Careful readers may have wondered: “But wait! Correlation doesn’t imply causation”. The observable fact that team morale and stakeholder satisfaction are higher in Agile teams does not necessarily mean that agility is the cause. And this is true. It is possible that the effect is actually the reverse; high morale or high stakeholder satisfaction drives teams to become more Agile. Or both bias teams to evaluate their processes in a more positive light than when morale or stakeholder satisfaction is lower. It is also possible that other variables explain both results. For example, an organization with a very flat hierarchical structure may both enable high agility as well as high morale or high stakeholder satisfaction.

Unfortunately, causality is very hard to establish with certainty. This requires highly controlled experiments where only the level of agility is manipulated in a team. But how can one feasibly do that? Another approach is to track many organizations over time as they adopt Agile methodologies, while also measuring anything else that could influence their results other than agility itself. It would be wonderful to have such data! However, the sheer effort involved is so gargantuan that this is close to impossible. Fortunately, we don’t need to put the bar that high. While correlation doesn’t imply causation, it can certainly make a case for it. Especially when we have strong corroborating evidence from other sources. Our data clearly shows that agility is associated with team morale and stakeholder satisfaction. So if you measure that one is going up, the others will probably go up too. Thus, it is probably easier for organizations to create environments for teams that encourage their Agility (e.g. high autonomy, responsiveness, etc) than it is to directly change the morale of team members or even the satisfaction of stakeholders.

But let's take a look at potential corroborating evidence. What do scientific studies have to say?

Finding #4: Scientific Studies Corroborate That Agility Generates Better Business Outcomes

We defined agility in terms of five processes. Agile teams are responsive , know who their stakeholders are and what they need, have high autonomy , and improve continuously . They are also supported by management . What do scientific studies have to say about the business outcomes of Agile methodologies, as well as the factors we just mentioned? So we went to Google Scholar and searched for review articles .

Cardozo et. al. (2010) reviewed 28 scientific studies that investigated how Scrum is associated with overall business outcomes. A strength of such a review is that it allows for the identification of patterns across many studies. The authors identified five core outcomes of Scrum: 1) higher productivity in teams, 2) higher customer satisfaction, 3) higher quality, 4) increased motivation in teams and 5) a general reduction in costs. While this study covers even more business outcomes, the second and fourth points match our findings.

A critical part of Agile methods is that new iterations of a product are released more frequently than in more traditional approaches. Several empirical studies have indeed found that teams with a frequent delivery strategy are more likely to deliver successful project outcomes and satisfy stakeholders than teams that do not ( Chow & Cao, 2008 , Jørgensen, 2016 ). This also matches our findings for stakeholder satisfaction.

But a high delivery strategy is of little value if what goes out to stakeholders doesn’t match their needs, or doesn’t reach the right people. So teams need to develop a good understanding of who their stakeholders are and what they need. Van Kelle et. al. (2015) collected data from 141 team members, Scrum Masters, and Product Owners from 40 projects. They found that the ability of teams to develop a shared sense of value contributed significantly and strongly to project success. They also found that the overall agility of teams increased the chance of project success. Hoda, Stuart & Marshall (2011) interviewed 30 Agile practitioners over a period of 3 years. They found that teams that collaborate closely with customers are more successful. However, they also observed that customers are rarely as involved as would be expected from Agile methodologies. This supports our finding that stakeholder satisfaction goes up as teams become more involved with their stakeholders (stakeholder concern).

“The ability of teams to develop a shared sense of value contributed significantly and strongly to project success.”

While high responsiveness and high concern for the needs of stakeholders are arguably the two pillars that distinguish Agile teams from non-Agile teams, these pillars need a good foundation. This is where team autonomy and continuous improvement come into play. Both are important characteristics of Agile teams because it allows them to remain effective in the face of complex, unpredictable work. Many studies have identified high autonomy as an important prerequisite for Agile teams ( Moe, Dingsøyr & Dybå, 2010 ; Donmez & Gudela, 2013 ; Tripp & Armstrong, 2018 ; Melo et. al. 2013 ). Lee & Xia (2010) surveyed 505 Agile projects and found that high autonomy allowed teams to respond more quickly to challenges. They also note that this is particularly relevant to complex challenges, which is typically the case for the product innovation that happens in Agile teams. As for continuous improvement, this is generally more a climate in teams than a process. It is marked by high safety, shared learning, high-quality Sprint Retrospectives, and ambitious quality standards. Hoda & Noble (2017) identified learning processes as essential for teams to become Agile. So while autonomy and continuous improvement may not directly result in business outcomes, they need to be present in order for Agile teams to generate outcomes that satisfy stakeholders, and through a process that is also satisfying to team members.

“While autonomy and continuous improvement may not directly result in business outcomes, they need to be present in order for Agile teams to generate outcomes that satisfy stakeholders, and through a process that is also satisfying to team members.”

Finally, this brings us to the role that management plays. Because their support is consistently identified by scientists as the most critical success factor to make all the above possible ( Van Waardenburg & Van Vliet, 2013 ; de Souza Bemerjo et. al., 2014 ; Young & Jordan, 2008 ; Russo, 2021 ). The shift that management has to go through is described by Manz et. al. (1987) as “leading others to lead (themselves)”. The authority to make work-related decisions shifts from external managers to the teams themselves. So rather than taking the lead, managers have to take a more supporting role and ask teams where they need their help. Second, management has to understand the point of Agile methodologies like Scrum and support teams by removing any obstacles they experience.

Click to enlarge

There are many other factors that can be considered. But the five processes we identified as characteristics of Agile teams provide a good, evidence-based starting point to make Agile teams more effective, and generate better business outcomes. Together with Prof. Daniel Russo We investigated a sample of 4.940 team members, aggregated into 1.978 Scrum teams, and found that these processes — or factors — together explain a very large amount of how effective Scrum teams (75.6%) are, and 34.9% of team morale and 57.9% of stakeholder satisfaction ( Verwijs & Russo, 2022 ).

What About Other Business Outcomes?

Obviously, team morale and stakeholder satisfaction are just two business outcomes for which economic arguments can be made. But more outcomes can be considered, like business longevity, the ability to deliver value within budget, and so on. We may cover these in future posts, as this one has already become way too long. And if happier team members and happier stakeholders aren’t already convincing enough, good results on those other outcomes aren’t probably going to change minds either :).

Implications For Practitioners

So what does all this mean in practice?

- An important lesson we’ve had to learn is that you can’t sell Agile or Scrum based on frameworks or ideals. Ultimately, the role of (top) management is to keep their business healthy and economically sustainable. Thus, the best way to convince them is to show how Scrum or Agile helps in that regard. This business case should provide some good talking points.

- Generally speaking, it is a good idea to track important business outcomes as metrics. For example; the number of sales, the number of unhappy customers, absenteeism, etc. This provides you with an opportunity to take an evidence-based approach to improvements. You can also measure such metrics alongside an ongoing Agile adoption, and see how Agile is improving certain metrics (or not).

- You can use the Scrum Team Survey to diagnose your Scrum or Agile team for free. We also give you tons of evidence-based feedback. The DIY Workshop: Diagnose Your Scrum Teams With The Scrum Team Survey is a great starting point.

- Our Do-It-Yourself Workshops are a great way to start improving without the need for external facilitators. The DIY Workshop: Discover The Needs Of Your Stakeholders With UX Fishbowl or Experiment: Deepen Your Understanding Of Scrum With Real-Life Cases are great starting points. The DIY Workshop: Build Understanding Between Scrum Teams And Management is also very useful if management support is the biggest issue. Find many more here .

- We offer a number of physical kits that are designed to start conversations with and between teams and the larger organization. We have the Scrum Team Starter Kit , the Unleash Scrum In Your Organization Kit , and the Zombie Scrum First Aid Kit . Each comes with creative exercises that we developed in our work with Scrum and Agile teams.

Our goal with this post was to make a stronger, evidence-based business case for Agile and Scrum. Taken together, we have strong evidence to support the belief that Agile teams deliver more value to their stakeholders than less Agile teams. They also have much higher team morale. Any company worth its salt would see the economic value in both of these outcomes. Happy stakeholders generate more revenue, spread positive word-of-mouth, and are more likely to stay. Similarly, happy team members are more productive and more likely to stay for the long term. If companies seriously invest in Agile, and in particular in the five factors we covered in this post, they are very likely to see better results.

Is this an indisputable fact? No. But the evidence to support it is very strong indeed, and growing every day.

This post took over 46 hours to research and write . Find more evidence-based posts here . We thank all the authors of the referenced papers and studies for their work.

Cardozo, E. S., Araújo Neto, J. B. F., Barza, A., França, A. C. C., & da Silva, F. Q. (2010, April). SCRUM and productivity in software projects: a systematic literature review. In 14th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering (EASE) (pp. 1–4).

Chow, T., & Cao, D. B. (2008). A survey study of critical success factors in agile software projects. Journal of systems and software , 81 (6), 961–971.

Dönmez, D., & Grote, G. (2013, June). The practice of not knowing for sure: How agile teams manage uncertainties. In International Conference on Agile Software Development (pp. 61–75). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Jørgensen, M. (2016). A survey on the characteristics of projects with success in delivering client benefits. Information and Software Technology , 78 , 83–94.

LePine, J. A., Erez, A., & Johnson, D. E. (2002). The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: a critical review and meta-analysis. Journal of applied psychology , 87 (1), 52.

Lee, G., & Xia, W. (2010). Toward agile: an integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitative field data on software development agility. MIS quarterly , 34 (1), 87–114.

Melo, C. D. O., Cruzes, D. S., Kon, F., & Conradi, R. (2013). Interpretative case studies on agile team productivity and management. Information and Software Technology , 55 (2), 412–427.

Moe, N. B., Dingsøyr, T., & Dybå, T. (2010). A teamwork model for understanding an agile team: A case study of a Scrum project. Information and software technology , 52 (5), 480–491.

Hacket, R. D. (1989). Work attitudes and employee absenteeism: A synthesis of the literature. Journal of occupational psychology , 62 (3), 235–248.

Hoda, R., & Noble, J. (2017, May). Becoming agile: a grounded theory of agile transitions in practice. In 2017 IEEE/ACM 39th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE) (pp. 141–151). IEEE.

Hoda, R., Noble, J., & Marshall, S. (2011). The impact of inadequate customer collaboration on self-organizing Agile teams. Information and software technology , 53 (5), 521–534.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological bulletin , 127 (3), 376.

Tripp, J., & Armstrong, D. J. (2018). Agile methodologies: organizational adoption motives, tailoring, and performance. Journal of Computer Information Systems , 58 (2), 170–179.

What did you think about this post?

Share with your network.

- Share this page via email

- Share this page on Facebook

- Share this page on Twitter

- Share this page on LinkedIn

View the discussion thread.

- Agile Education Program

- The Agile Navigator

Agile Unleashed at Scale

How john deere’s global it group implemented a holistic transformation powered by scrum@scale, scrum, devops, and a modernized technology stack, agile unleashed at scale: results at a glance, executive summary.

In 2019 John Deere’s Global IT group launched an Agile transformation with the simple but ambitious goal of improving speed to outcomes.

As with most Fortune 100 companies, Agile methodologies and practices were not new to John Deere’s Global IT group, but senior leadership wasn’t seeing the results they desired. “We had used other scaled frameworks in the past—which are perfectly strong Agile processes,” explains Josh Edgin, Transformation Lead at John Deere, “But with PSI planning and two-month release cycles, I think you can get comfortable transforming into a mini-waterfall.” Edgin adds, “We needed to evolve.”

Senior leadership decided to launch a holistic transformation that would touch every aspect of the group’s work – from application development to core infrastructure; from customer and dealer-facing products to operations-oriented design, manufacturing and supply chain, and internal/back-end finance and human resource products.

Picking the right Agile framework is one of the most important decisions an organization can make. This is especially true when effective scaling is a core component of the overall strategy. “Leadership found the Scrum@Scale methodology to be the right fit to scale across IT and the rest of the business,” states Ganesh Jayaram, John Deere’s Vice President of Global IT. Therefore, the Scrum and Scrum@Scale frameworks, entwined with DevOps and technical upskilling became the core components of the group’s new Agile Operating Model (AOM).

Picking the right Agile consulting, training, and coaching support can be just as important as the choice of framework. Scrum Inc. is known for its expertise, deep experience, and long track record of success in both training and large and complex transformations. Additionally, Scrum Inc. offered industry-leading on-demand courses to accelerate the implementation, and a proven path to create self-sustaining Agile organizations able to successfully run their own Agile journey.

“I remember standing in front of our CEO and the Board of Directors to make this pitch,” says Jayaram, “because it was the single largest investment Global IT has made in terms of capital and expense.” But the payoff, he adds, would be significant. “We bet the farm so to speak. We promised we would do more, do it faster, and do it cheaper.”

John Deere’s CEO gave the transformation a green light.

Just two years into the effort it is a bet that has paid off.

Metrics and Results

Enterprise-level results include:

- Return on Investment: John Deere estimates its ROI from the Global IT group’s transformation to be greater than 100 percent .

- Output: Has increased by 165 percent , exceeding the initial goal of 125 percent.

- Time to Market: Has been reduced by 63 percent — leadership initially sought a 40 percent reduction.

- Engineering Ratio: When looking at the complete organizational structure of Scrum Masters, Product Owners, Agile Coaches, Engineering Managers, UX Professionals, and team members, leadership set a target of 75% with “fingers on keyboards” delivering value through engineering. This ratio now stands at 77.7 percent .

- Cost Efficiency: Leadership wanted to reduce the labor costs of the group by 20 percent . They have achieved this goal through insourcing and strategic hiring–even with the addition of Scrum and Agile roles.

- Employee NPS (eNPS): Employee Net Promoter Score, or eNPS, is a reflection of team health. The Global IT group began with a 42-point baseline. A score above 50 is considered excellent. The group now has a score of 65 , greater than the 20-point improvement targeted by leadership.

John Deere’s Global IT group has seen function/team level improvements that far exceed these results. Order Management, the pilot project for this implementation has seen team results which include:

- The number of Functions/Features Delivered per Sprint has increased by more than 10X

- The number of Deploys has improved by more than 15X

As Jayaram notes, “When you look at some of the metrics and you see a 1,000 percent improvement you can’t help but think they got the baseline wrong.”

But the baselines are right. The improvement is real.

John Deere’s Global IT group has also seen exponential results thanks to the implementation of the AOM. “We’ve delivered an order of magnitude more value and bottom-line impact to John Deere in the ERP space than in any previous year,” states Edgin. These results include:

- Time to Market: Reduced by 87 percent

- Deploys: Increased by 400 percent

- Features/Functions Delivered per Sprint: Has nearly tripled

Edgin adds that “every quality measure has improved measurably. We’re delivering things at speeds previously not thought possible. And we’re doing it with fewer people.”

Training at Scale and Creating a Self-Sufficient Agile Organization

The Wave/Phase approach has ensured both effective and efficient training across John Deere’s Global IT group. As of December 2021, roughly 24-months after its inception:

- 295 teams have successfully completed a full wave of training

- Approximately 2,500 individuals have successfully completed their training

- 50 teams were actively in wave training

- Approximately 150 teams were actively preparing to enter a wave

John Deere’s Global IT group is well on its way to becoming a self-sustaining Agile organization thanks to its work with Scrum Inc.

- Internal training capacity increased by 64 percent over a two-year span

- The number of classes led by internal trainers doubled (from 25 to 50) between 2020 and 2021

Click on the Section Titles Below to Read this I n-Depth Case Study

1. introduction: the complex challenge to overcome.

This need can be unlocking innovation, overcoming a complex challenge, more efficient and effective prioritization, removing roadblocks, or the desire to delight customers through innovation and value delivery.

Ganesh Jayaram is John Deere’s Vice President of Global IT. He summarizes the overarching need behind this Agile transformation down to a simple but powerful four-word vision; improve speed to outcomes.

Note this is not going fast just for the sake of going fast – that can be a recipe for unhappy customers and decreased quality. Very much the opposite of Agile.

Dissect Jayaram’s vision, and you’ll find elements at the heart of Agile itself; rapid iteration, innovation, quality, value delivery, and most importantly, delighted customers. Had John Deere lost sight of these elements? Absolutely not.

As Jayaram explains, “we intended to significantly improve on delivering these outcomes.” To do this, Jayaram and his leadership team decomposed their vision of ‘improve speed to outcomes’ into three enterprise-level goals:

- Speed to Understanding: How would they know they are truly sensitive to what their customers – both internal and external – care about, want, and need?

- Speed to Decision Making: Decrease decision latency to improve the ability to capitalize on opportunities, respond to market changes, or pivot based on rapid feedback.

- Speed to Execution: Decrease time to market while maintaining or improving quality and value delivery.

Deere’s Global IT leadership knew achieving their vision and these goals would take more than incremental adjustments. Beneficial change at this level requires a holistic transformation that spans the IT group as well as the business partners.

They needed the right Agile transformation support, the ability to efficiently and effectively scale both training and operations and to build the in-house expertise to make the group’s Agile journey a self-sustaining one. As Josh Edgin, Global IT Transformation Lead at John Deere states, “We needed to evolve.”

2. Background: The Transformation's Ambitious Goals

Before this transformation, John Deere’s Global IT function operated like that of many large organizations. In broad terms, this meant that:

- The department had isolated pockets of Agile teams that implemented several different Agile frameworks in an ad hoc way

- Teams were often assigned to projects which were funded for a fixed period of time

- The exact work to be done on projects was dictated by extensive business analysis and similar plans

- Outsourcing of projects or components to third-party suppliers was commonplace

- The manager role was largely comprised of primarily directing and prioritizing work for their teams

At John Deere, process maturity was very high. Practices such as these were created in the Second Industrial Revolution and they can deliver value, especially if you have a defined, repeatable process. However, if you have a product or service that needs to evolve to meet changing market demands, these legacy leadership practices can quickly become liabilities.