Action Research

Welcome to Learning Episode 9

This output is in partial fulfilment of the requirements in educ 71-field study 2 (participation & assistantship for pre-service teacher) under ms. garin a. boiser our instructor in educ 71. i would love to showcase my output about this episode " making a doable action research proposal " for this course of which it truly help me to develop and honed my skills and abilities true progress throughout my journey as a pre-service teacher..

At the end of this Episode, you must be able to:

Define the focus of your study., clearly identify the variables to be measure., indicates the various steps to be involved., establish the limits of your study..

Here are the based answers on my Field Study 2 Manual

THE WHOLE COPY OF OUR ACTION RESEARCH PROPOSAL

Link of the paper here - https://drive.google.com/file/d/15e391TAm9OSL8Wtjnvgtk5eOIEoPLmyW/view?fbclid=IwAR2IzN75MSNgT3AJP2PUIHXf-iL0Ic9hX5x2wbNJ3nuEO0DLMJBdw-0gYQs

THANKS TO THE PANELIST AND TO OUR ADVISER

We made it to the top, 3rd best action research.

This wouldn't happen without the guidance of our Beautiful, Kind, Humble, and Sweet Maam Garin Boiser. If you read this part here Maam thank you to the moon and back.

To my co-researchers thank you for your dedication and self courage to fight with me in giving justice to our research paper. to our parents, friends, relative, and to those who help us in making to the top, thank you. lastly, to almighty god for all of this blessings.

( Click on Learning Evidences ) ( To proceed Click Next )

Learning Evidence

About the Author

Get in touch

Email me: [email protected], contact me: +6396-5812-5532.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What is the nature of action research?

- How does action research develop in the classroom?

- What models of action research work best for your classroom?

- What are the epistemological, ontological, theoretical underpinnings of action research?

Educational research provides a vast landscape of knowledge on topics related to teaching and learning, curriculum and assessment, students’ cognitive and affective needs, cultural and socio-economic factors of schools, and many other factors considered viable to improving schools. Educational stakeholders rely on research to make informed decisions that ultimately affect the quality of schooling for their students. Accordingly, the purpose of educational research is to engage in disciplined inquiry to generate knowledge on topics significant to the students, teachers, administrators, schools, and other educational stakeholders. Just as the topics of educational research vary, so do the approaches to conducting educational research in the classroom. Your approach to research will be shaped by your context, your professional identity, and paradigm (set of beliefs and assumptions that guide your inquiry). These will all be key factors in how you generate knowledge related to your work as an educator.

Action research is an approach to educational research that is commonly used by educational practitioners and professionals to examine, and ultimately improve, their pedagogy and practice. In this way, action research represents an extension of the reflection and critical self-reflection that an educator employs on a daily basis in their classroom. When students are actively engaged in learning, the classroom can be dynamic and uncertain, demanding the constant attention of the educator. Considering these demands, educators are often only able to engage in reflection that is fleeting, and for the purpose of accommodation, modification, or formative assessment. Action research offers one path to more deliberate, substantial, and critical reflection that can be documented and analyzed to improve an educator’s practice.

Purpose of Action Research

As one of many approaches to educational research, it is important to distinguish the potential purposes of action research in the classroom. This book focuses on action research as a method to enable and support educators in pursuing effective pedagogical practices by transforming the quality of teaching decisions and actions, to subsequently enhance student engagement and learning. Being mindful of this purpose, the following aspects of action research are important to consider as you contemplate and engage with action research methodology in your classroom:

- Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices.

- Action research is participative and collaborative. It is undertaken by individuals with a common purpose.

- Action research is situation and context-based.

- Action research develops reflection practices based on the interpretations made by participants.

- Knowledge is created through action and application.

- Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

- Action research is iterative; plans are created, implemented, revised, then implemented, lending itself to an ongoing process of reflection and revision.

- In action research, findings emerge as action develops and takes place; however, they are not conclusive or absolute, but ongoing (Koshy, 2010, pgs. 1-2).

In thinking about the purpose of action research, it is helpful to situate action research as a distinct paradigm of educational research. I like to think about action research as part of the larger concept of living knowledge. Living knowledge has been characterized as “a quest for life, to understand life and to create… knowledge which is valid for the people with whom I work and for myself” (Swantz, in Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 1). Why should educators care about living knowledge as part of educational research? As mentioned above, action research is meant “to produce practical knowledge that is useful to people in the everyday conduct of their lives and to see that action research is about working towards practical outcomes” (Koshy, 2010, pg. 2). However, it is also about:

creating new forms of understanding, since action without reflection and understanding is blind, just as theory without action is meaningless. The participatory nature of action research makes it only possible with, for and by persons and communities, ideally involving all stakeholders both in the questioning and sense making that informs the research, and in the action, which is its focus. (Reason & Bradbury, 2001, pg. 2)

In an effort to further situate action research as living knowledge, Jean McNiff reminds us that “there is no such ‘thing’ as ‘action research’” (2013, pg. 24). In other words, action research is not static or finished, it defines itself as it proceeds. McNiff’s reminder characterizes action research as action-oriented, and a process that individuals go through to make their learning public to explain how it informs their practice. Action research does not derive its meaning from an abstract idea, or a self-contained discovery – action research’s meaning stems from the way educators negotiate the problems and successes of living and working in the classroom, school, and community.

While we can debate the idea of action research, there are people who are action researchers, and they use the idea of action research to develop principles and theories to guide their practice. Action research, then, refers to an organization of principles that guide action researchers as they act on shared beliefs, commitments, and expectations in their inquiry.

Reflection and the Process of Action Research

When an individual engages in reflection on their actions or experiences, it is typically for the purpose of better understanding those experiences, or the consequences of those actions to improve related action and experiences in the future. Reflection in this way develops knowledge around these actions and experiences to help us better regulate those actions in the future. The reflective process generates new knowledge regularly for classroom teachers and informs their classroom actions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge generated by educators through the reflective process is not always prioritized among the other sources of knowledge educators are expected to utilize in the classroom. Educators are expected to draw upon formal types of knowledge, such as textbooks, content standards, teaching standards, district curriculum and behavioral programs, etc., to gain new knowledge and make decisions in the classroom. While these forms of knowledge are important, the reflective knowledge that educators generate through their pedagogy is the amalgamation of these types of knowledge enacted in the classroom. Therefore, reflective knowledge is uniquely developed based on the action and implementation of an educator’s pedagogy in the classroom. Action research offers a way to formalize the knowledge generated by educators so that it can be utilized and disseminated throughout the teaching profession.

Research is concerned with the generation of knowledge, and typically creating knowledge related to a concept, idea, phenomenon, or topic. Action research generates knowledge around inquiry in practical educational contexts. Action research allows educators to learn through their actions with the purpose of developing personally or professionally. Due to its participatory nature, the process of action research is also distinct in educational research. There are many models for how the action research process takes shape. I will share a few of those here. Each model utilizes the following processes to some extent:

- Plan a change;

- Take action to enact the change;

- Observe the process and consequences of the change;

- Reflect on the process and consequences;

- Act, observe, & reflect again and so on.

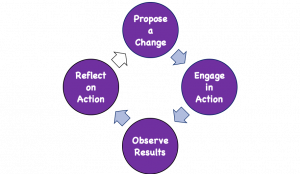

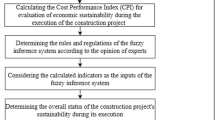

Figure 1.1 Basic action research cycle

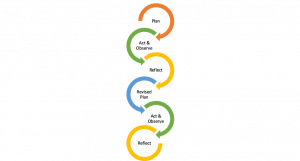

There are many other models that supplement the basic process of action research with other aspects of the research process to consider. For example, figure 1.2 illustrates a spiral model of action research proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (2004). The spiral model emphasizes the cyclical process that moves beyond the initial plan for change. The spiral model also emphasizes revisiting the initial plan and revising based on the initial cycle of research:

Figure 1.2 Interpretation of action research spiral, Kemmis and McTaggart (2004, p. 595)

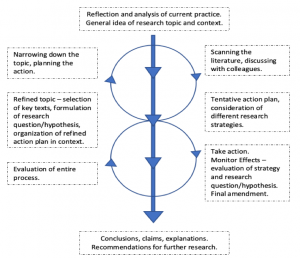

Other models of action research reorganize the process to emphasize the distinct ways knowledge takes shape in the reflection process. O’Leary’s (2004, p. 141) model, for example, recognizes that the research may take shape in the classroom as knowledge emerges from the teacher’s observations. O’Leary highlights the need for action research to be focused on situational understanding and implementation of action, initiated organically from real-time issues:

Figure 1.3 Interpretation of O’Leary’s cycles of research, O’Leary (2000, p. 141)

Lastly, Macintyre’s (2000, p. 1) model, offers a different characterization of the action research process. Macintyre emphasizes a messier process of research with the initial reflections and conclusions as the benchmarks for guiding the research process. Macintyre emphasizes the flexibility in planning, acting, and observing stages to allow the process to be naturalistic. Our interpretation of Macintyre process is below:

Figure 1.4 Interpretation of the action research cycle, Macintyre (2000, p. 1)

We believe it is important to prioritize the flexibility of the process, and encourage you to only use these models as basic guides for your process. Your process may look similar, or you may diverge from these models as you better understand your students, context, and data.

Definitions of Action Research and Examples

At this point, it may be helpful for readers to have a working definition of action research and some examples to illustrate the methodology in the classroom. Bassey (1998, p. 93) offers a very practical definition and describes “action research as an inquiry which is carried out in order to understand, to evaluate and then to change, in order to improve educational practice.” Cohen and Manion (1994, p. 192) situate action research differently, and describe action research as emergent, writing:

essentially an on-the-spot procedure designed to deal with a concrete problem located in an immediate situation. This means that ideally, the step-by-step process is constantly monitored over varying periods of time and by a variety of mechanisms (questionnaires, diaries, interviews and case studies, for example) so that the ensuing feedback may be translated into modifications, adjustment, directional changes, redefinitions, as necessary, so as to bring about lasting benefit to the ongoing process itself rather than to some future occasion.

Lastly, Koshy (2010, p. 9) describes action research as:

a constructive inquiry, during which the researcher constructs his or her knowledge of specific issues through planning, acting, evaluating, refining and learning from the experience. It is a continuous learning process in which the researcher learns and also shares the newly generated knowledge with those who may benefit from it.

These definitions highlight the distinct features of action research and emphasize the purposeful intent of action researchers to improve, refine, reform, and problem-solve issues in their educational context. To better understand the distinctness of action research, these are some examples of action research topics:

Examples of Action Research Topics

- Flexible seating in 4th grade classroom to increase effective collaborative learning.

- Structured homework protocols for increasing student achievement.

- Developing a system of formative feedback for 8th grade writing.

- Using music to stimulate creative writing.

- Weekly brown bag lunch sessions to improve responses to PD from staff.

- Using exercise balls as chairs for better classroom management.

Action Research in Theory

Action research-based inquiry in educational contexts and classrooms involves distinct participants – students, teachers, and other educational stakeholders within the system. All of these participants are engaged in activities to benefit the students, and subsequently society as a whole. Action research contributes to these activities and potentially enhances the participants’ roles in the education system. Participants’ roles are enhanced based on two underlying principles:

- communities, schools, and classrooms are sites of socially mediated actions, and action research provides a greater understanding of self and new knowledge of how to negotiate these socially mediated environments;

- communities, schools, and classrooms are part of social systems in which humans interact with many cultural tools, and action research provides a basis to construct and analyze these interactions.

In our quest for knowledge and understanding, we have consistently analyzed human experience over time and have distinguished between types of reality. Humans have constantly sought “facts” and “truth” about reality that can be empirically demonstrated or observed.

Social systems are based on beliefs, and generally, beliefs about what will benefit the greatest amount of people in that society. Beliefs, and more specifically the rationale or support for beliefs, are not always easy to demonstrate or observe as part of our reality. Take the example of an English Language Arts teacher who prioritizes argumentative writing in her class. She believes that argumentative writing demonstrates the mechanics of writing best among types of writing, while also providing students a skill they will need as citizens and professionals. While we can observe the students writing, and we can assess their ability to develop a written argument, it is difficult to observe the students’ understanding of argumentative writing and its purpose in their future. This relates to the teacher’s beliefs about argumentative writing; we cannot observe the real value of the teaching of argumentative writing. The teacher’s rationale and beliefs about teaching argumentative writing are bound to the social system and the skills their students will need to be active parts of that system. Therefore, our goal through action research is to demonstrate the best ways to teach argumentative writing to help all participants understand its value as part of a social system.

The knowledge that is conveyed in a classroom is bound to, and justified by, a social system. A postmodernist approach to understanding our world seeks knowledge within a social system, which is directly opposed to the empirical or positivist approach which demands evidence based on logic or science as rationale for beliefs. Action research does not rely on a positivist viewpoint to develop evidence and conclusions as part of the research process. Action research offers a postmodernist stance to epistemology (theory of knowledge) and supports developing questions and new inquiries during the research process. In this way action research is an emergent process that allows beliefs and decisions to be negotiated as reality and meaning are being constructed in the socially mediated space of the classroom.

Theorizing Action Research for the Classroom

All research, at its core, is for the purpose of generating new knowledge and contributing to the knowledge base of educational research. Action researchers in the classroom want to explore methods of improving their pedagogy and practice. The starting place of their inquiry stems from their pedagogy and practice, so by nature the knowledge created from their inquiry is often contextually specific to their classroom, school, or community. Therefore, we should examine the theoretical underpinnings of action research for the classroom. It is important to connect action research conceptually to experience; for example, Levin and Greenwood (2001, p. 105) make these connections:

- Action research is context bound and addresses real life problems.

- Action research is inquiry where participants and researchers cogenerate knowledge through collaborative communicative processes in which all participants’ contributions are taken seriously.

- The meanings constructed in the inquiry process lead to social action or these reflections and action lead to the construction of new meanings.

- The credibility/validity of action research knowledge is measured according to whether the actions that arise from it solve problems (workability) and increase participants’ control over their own situation.

Educators who engage in action research will generate new knowledge and beliefs based on their experiences in the classroom. Let us emphasize that these are all important to you and your work, as both an educator and researcher. It is these experiences, beliefs, and theories that are often discounted when more official forms of knowledge (e.g., textbooks, curriculum standards, districts standards) are prioritized. These beliefs and theories based on experiences should be valued and explored further, and this is one of the primary purposes of action research in the classroom. These beliefs and theories should be valued because they were meaningful aspects of knowledge constructed from teachers’ experiences. Developing meaning and knowledge in this way forms the basis of constructivist ideology, just as teachers often try to get their students to construct their own meanings and understandings when experiencing new ideas.

Classroom Teachers Constructing their Own Knowledge

Most of you are probably at least minimally familiar with constructivism, or the process of constructing knowledge. However, what is constructivism precisely, for the purposes of action research? Many scholars have theorized constructivism and have identified two key attributes (Koshy, 2010; von Glasersfeld, 1987):

- Knowledge is not passively received, but actively developed through an individual’s cognition;

- Human cognition is adaptive and finds purpose in organizing the new experiences of the world, instead of settling for absolute or objective truth.

Considering these two attributes, constructivism is distinct from conventional knowledge formation because people can develop a theory of knowledge that orders and organizes the world based on their experiences, instead of an objective or neutral reality. When individuals construct knowledge, there are interactions between an individual and their environment where communication, negotiation and meaning-making are collectively developing knowledge. For most educators, constructivism may be a natural inclination of their pedagogy. Action researchers have a similar relationship to constructivism because they are actively engaged in a process of constructing knowledge. However, their constructions may be more formal and based on the data they collect in the research process. Action researchers also are engaged in the meaning making process, making interpretations from their data. These aspects of the action research process situate them in the constructivist ideology. Just like constructivist educators, action researchers’ constructions of knowledge will be affected by their individual and professional ideas and values, as well as the ecological context in which they work (Biesta & Tedder, 2006). The relations between constructivist inquiry and action research is important, as Lincoln (2001, p. 130) states:

much of the epistemological, ontological, and axiological belief systems are the same or similar, and methodologically, constructivists and action researchers work in similar ways, relying on qualitative methods in face-to-face work, while buttressing information, data and background with quantitative method work when necessary or useful.

While there are many links between action research and educators in the classroom, constructivism offers the most familiar and practical threads to bind the beliefs of educators and action researchers.

Epistemology, Ontology, and Action Research

It is also important for educators to consider the philosophical stances related to action research to better situate it with their beliefs and reality. When researchers make decisions about the methodology they intend to use, they will consider their ontological and epistemological stances. It is vital that researchers clearly distinguish their philosophical stances and understand the implications of their stance in the research process, especially when collecting and analyzing their data. In what follows, we will discuss ontological and epistemological stances in relation to action research methodology.

Ontology, or the theory of being, is concerned with the claims or assumptions we make about ourselves within our social reality – what do we think exists, what does it look like, what entities are involved and how do these entities interact with each other (Blaikie, 2007). In relation to the discussion of constructivism, generally action researchers would consider their educational reality as socially constructed. Social construction of reality happens when individuals interact in a social system. Meaningful construction of concepts and representations of reality develop through an individual’s interpretations of others’ actions. These interpretations become agreed upon by members of a social system and become part of social fabric, reproduced as knowledge and beliefs to develop assumptions about reality. Researchers develop meaningful constructions based on their experiences and through communication. Educators as action researchers will be examining the socially constructed reality of schools. In the United States, many of our concepts, knowledge, and beliefs about schooling have been socially constructed over the last hundred years. For example, a group of teachers may look at why fewer female students enroll in upper-level science courses at their school. This question deals directly with the social construction of gender and specifically what careers females have been conditioned to pursue. We know this is a social construction in some school social systems because in other parts of the world, or even the United States, there are schools that have more females enrolled in upper level science courses than male students. Therefore, the educators conducting the research have to recognize the socially constructed reality of their school and consider this reality throughout the research process. Action researchers will use methods of data collection that support their ontological stance and clarify their theoretical stance throughout the research process.

Koshy (2010, p. 23-24) offers another example of addressing the ontological challenges in the classroom:

A teacher who was concerned with increasing her pupils’ motivation and enthusiasm for learning decided to introduce learning diaries which the children could take home. They were invited to record their reactions to the day’s lessons and what they had learnt. The teacher reported in her field diary that the learning diaries stimulated the children’s interest in her lessons, increased their capacity to learn, and generally improved their level of participation in lessons. The challenge for the teacher here is in the analysis and interpretation of the multiplicity of factors accompanying the use of diaries. The diaries were taken home so the entries may have been influenced by discussions with parents. Another possibility is that children felt the need to please their teacher. Another possible influence was that their increased motivation was as a result of the difference in style of teaching which included more discussions in the classroom based on the entries in the dairies.

Here you can see the challenge for the action researcher is working in a social context with multiple factors, values, and experiences that were outside of the teacher’s control. The teacher was only responsible for introducing the diaries as a new style of learning. The students’ engagement and interactions with this new style of learning were all based upon their socially constructed notions of learning inside and outside of the classroom. A researcher with a positivist ontological stance would not consider these factors, and instead might simply conclude that the dairies increased motivation and interest in the topic, as a result of introducing the diaries as a learning strategy.

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, signifies a philosophical view of what counts as knowledge – it justifies what is possible to be known and what criteria distinguishes knowledge from beliefs (Blaikie, 1993). Positivist researchers, for example, consider knowledge to be certain and discovered through scientific processes. Action researchers collect data that is more subjective and examine personal experience, insights, and beliefs.

Action researchers utilize interpretation as a means for knowledge creation. Action researchers have many epistemologies to choose from as means of situating the types of knowledge they will generate by interpreting the data from their research. For example, Koro-Ljungberg et al., (2009) identified several common epistemologies in their article that examined epistemological awareness in qualitative educational research, such as: objectivism, subjectivism, constructionism, contextualism, social epistemology, feminist epistemology, idealism, naturalized epistemology, externalism, relativism, skepticism, and pluralism. All of these epistemological stances have implications for the research process, especially data collection and analysis. Please see the table on pages 689-90, linked below for a sketch of these potential implications:

Again, Koshy (2010, p. 24) provides an excellent example to illustrate the epistemological challenges within action research:

A teacher of 11-year-old children decided to carry out an action research project which involved a change in style in teaching mathematics. Instead of giving children mathematical tasks displaying the subject as abstract principles, she made links with other subjects which she believed would encourage children to see mathematics as a discipline that could improve their understanding of the environment and historic events. At the conclusion of the project, the teacher reported that applicable mathematics generated greater enthusiasm and understanding of the subject.

The educator/researcher engaged in action research-based inquiry to improve an aspect of her pedagogy. She generated knowledge that indicated she had improved her students’ understanding of mathematics by integrating it with other subjects – specifically in the social and ecological context of her classroom, school, and community. She valued constructivism and students generating their own understanding of mathematics based on related topics in other subjects. Action researchers working in a social context do not generate certain knowledge, but knowledge that emerges and can be observed and researched again, building upon their knowledge each time.

Researcher Positionality in Action Research

In this first chapter, we have discussed a lot about the role of experiences in sparking the research process in the classroom. Your experiences as an educator will shape how you approach action research in your classroom. Your experiences as a person in general will also shape how you create knowledge from your research process. In particular, your experiences will shape how you make meaning from your findings. It is important to be clear about your experiences when developing your methodology too. This is referred to as researcher positionality. Maher and Tetreault (1993, p. 118) define positionality as:

Gender, race, class, and other aspects of our identities are markers of relational positions rather than essential qualities. Knowledge is valid when it includes an acknowledgment of the knower’s specific position in any context, because changing contextual and relational factors are crucial for defining identities and our knowledge in any given situation.

By presenting your positionality in the research process, you are signifying the type of socially constructed, and other types of, knowledge you will be using to make sense of the data. As Maher and Tetreault explain, this increases the trustworthiness of your conclusions about the data. This would not be possible with a positivist ontology. We will discuss positionality more in chapter 6, but we wanted to connect it to the overall theoretical underpinnings of action research.

Advantages of Engaging in Action Research in the Classroom

In the following chapters, we will discuss how action research takes shape in your classroom, and we wanted to briefly summarize the key advantages to action research methodology over other types of research methodology. As Koshy (2010, p. 25) notes, action research provides useful methodology for school and classroom research because:

Advantages of Action Research for the Classroom

- research can be set within a specific context or situation;

- researchers can be participants – they don’t have to be distant and detached from the situation;

- it involves continuous evaluation and modifications can be made easily as the project progresses;

- there are opportunities for theory to emerge from the research rather than always follow a previously formulated theory;

- the study can lead to open-ended outcomes;

- through action research, a researcher can bring a story to life.

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Section 2: Home

- Developing the Quantitative Research Design

- Qualitative Descriptive Design

- Design and Development Research (DDR) For Instructional Design

- Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Action Research Resource

What is Action Research?

Considerations, creating a plan of action.

- Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate

- SAGE Research Methods

- Research Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- Dataset Examples (SAGE) This link opens in a new window

- IRB Resource Center This link opens in a new window

Action research is a qualitative method that focuses on solving problems in social systems, such as schools and other organizations. The emphasis is on solving the presenting problem by generating knowledge and taking action within the social system in which the problem is located. The goal is to generate shared knowledge of how to address the problem by bridging the theory-practice gap (Bourner & Brook, 2019). A general definition of action research is the following: “Action research brings together action and reflection, as well as theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern” (Bradbury, 2015, p. 1). Johnson (2019) defines action research in the field of education as “the process of studying a school, classroom, or teacher-learning situation with the purpose of understanding and improving the quality of actions or instruction” (p.255).

Origins of Action Research

Kurt Lewin is typically credited with being the primary developer of Action Research in the 1940s. Lewin stated that action research can “transform…unrelated individuals, frequently opposed in their outlook and their interests, into cooperative teams, not on the basis of sweetness but on the basis of readiness to face difficulties realistically, to apply honest fact-finding, and to work together to overcome them” (1946, p.211).

Sample Action Research Topics

Some sample action research topics might be the following:

- Examining how classroom teachers perceive and implement new strategies in the classroom--How is the strategy being used? How do students respond to the strategy? How does the strategy inform and change classroom practices? Does the new skill improve test scores? Do classroom teachers perceive the strategy as effective for student learning?

- Examining how students are learning a particular content or objectives--What seems to be effective in enhancing student learning? What skills need to be reinforced? How do students respond to the new content? What is the ability of students to understand the new content?

- Examining how education stakeholders (administrator, parents, teachers, students, etc.) make decisions as members of the school’s improvement team--How are different stakeholders encouraged to participate? How is power distributed? How is equity demonstrated? How is each voice valued? How are priorities and initiatives determined? How does the team evaluate its processes to determine effectiveness?

- Examining the actions that school staff take to create an inclusive and welcoming school climate--Who makes and implements the actions taken to create the school climate? Do members of the school community (teachers, staff, students) view the school climate as inclusive? Do members of the school community feel welcome in the school? How are members of the school community encouraged to become involved in school activities? What actions can school staff take to help others feel a part of the school community?

- Examining the perceptions of teachers with regard to the learning strategies that are more effective with special populations, such as special education students, English Language Learners, etc.—What strategies are perceived to be more effective? How do teachers plan instructionally for unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners? How do teachers deal with the challenges presented by unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners? What supports do teachers need (e.g., professional development, training, coaching) to more effectively deliver instruction to unique learners such as special education students or English Language Learners?

Remember—The goal of action research is to find out how individuals perceive and act in a situation so the researcher can develop a plan of action to improve the educational organization. While these topics listed here can be explored using other research designs, action research is the design to use if the outcome is to develop a plan of action for addressing and improving upon a situation in the educational organization.

Considerations for Determining Whether to Use Action Research in an Applied Dissertation

- When considering action research, first determine the problem and the change that needs to occur as a result of addressing the problem (i.e., research problem and research purpose). Remember, the goal of action research is to change how individuals address a particular problem or situation in a way that results in improved practices.

- If the study will be conducted at a school site or educational organization, you may need site permission. Determine whether site permission will be given to conduct the study.

- Consider the individuals who will be part of the data collection (e.g., teachers, administrators, parents, other school staff, etc.). Will there be a representative sample willing to participate in the research?

- If students will be part of the study, does parent consent and student assent need to be obtained?

- As you develop your data collection plan, also consider the timeline for data collection. Is it feasible? For example, if you will be collecting data in a school, consider winter and summer breaks, school events, testing schedules, etc.

- As you develop your data collection plan, consult with your dissertation chair, Subject Matter Expert, NU Academic Success Center, and the NU IRB for resources and guidance.

- Action research is not an experimental design, so you are not trying to accept or reject a hypothesis. There are no independent or dependent variables. It is not generalizable to a larger setting. The goal is to understand what is occurring in the educational setting so that a plan of action can be developed for improved practices.

Considerations for Action Research

Below are some things to consider when developing your applied dissertation proposal using Action Research (adapted from Johnson, 2019):

- Research Topic and Research Problem -- Decide the topic to be studied and then identify the problem by defining the issue in the learning environment. Use references from current peer-reviewed literature for support.

- Purpose of the Study —What need to be different or improved as a result of the study?

- Research Questions —The questions developed should focus on “how” or “what” and explore individuals’ experiences, beliefs, and perceptions.

- Theoretical Framework -- What are the existing theories (theoretical framework) or concepts (conceptual framework) that can be used to support the research. How does existing theory link to what is happening in the educational environment with regard to the topic? What theories have been used to support similar topics in previous research?

- Literature Review -- Examine the literature, focusing on peer-reviewed studies published in journal within the last five years, with the exception of seminal works. What about the topic has already been explored and examined? What were the findings, implications, and limitations of previous research? What is missing from the literature on the topic? How will your proposed research address the gap in the literature?

- Data Collection —Who will be part of the sample for data collection? What data will be collected from the individuals in the study (e.g., semi-structured interviews, surveys, etc.)? What are the educational artifacts and documents that need to be collected (e.g., teacher less plans, student portfolios, student grades, etc.)? How will they be collected and during what timeframe? (Note--A list of sample data collection methods appears under the heading of “Sample Instrumentation.”)

- Data Analysis —Determine how the data will be analyzed. Some types of analyses that are frequently used for action research include thematic analysis and content analysis.

- Implications —What conclusions can be drawn based upon the findings? How do the findings relate to the existing literature and inform theory in the field of education?

- Recommendations for Practice--Create a Plan of Action— This is a critical step in action research. A plan of action is created based upon the data analysis, findings, and implications. In the Applied Dissertation, this Plan of Action is included with the Recommendations for Practice. The includes specific steps that individuals should take to change practices; recommendations for how those changes will occur (e.g., professional development, training, school improvement planning, committees to develop guidelines and policies, curriculum review committee, etc.); and methods to evaluate the plan’s effectiveness.

- Recommendations for Research —What should future research focus on? What type of studies need to be conducted to build upon or further explore your findings.

- Professional Presentation or Defense —This is where the findings will be presented in a professional presentation or defense as the culmination of your research.

Adapted from Johnson (2019).

Considerations for Sampling and Data Collection

Below are some tips for sampling, sample size, data collection, and instrumentation for Action Research:

Sampling and Sample Size

Action research uses non-probability sampling. This is most commonly means a purposive sampling method that includes specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, convenience sampling can also be used (e.g., a teacher’s classroom).

Critical Concepts in Data Collection

Triangulation- - Dosemagen and Schwalbach (2019) discussed the importance of triangulation in Action Research which enhances the trustworthiness by providing multiple sources of data to analyze and confirm evidence for findings.

Trustworthiness —Trustworthiness assures that research findings are fulfill four critical elements—credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability. Reflect on the following: Are there multiple sources of data? How have you ensured credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability? Have the assumptions, limitations, and delimitations of the study been identified and explained? Was the sample a representative sample for the study? Did any individuals leave the study before it ended? How have you controlled researcher biases and beliefs? Are you drawing conclusions that are not supported by data? Have all possible themes been considered? Have you identified other studies with similar results?

Sample Instrumentation

Below are some of the possible methods for collecting action research data:

- Pre- and Post-Surveys for students and/or staff

- Staff Perception Surveys and Questionnaires

- Semi-Structured Interviews

- Focus Groups

- Observations

- Document analysis

- Student work samples

- Classroom artifacts, such as teacher lesson plans, rubrics, checklists, etc.

- Attendance records

- Discipline data

- Journals from students and/or staff

- Portfolios from students and/or staff

A benefit of Action Research is its potential to influence educational practice. Many educators are, by nature of the profession, reflective, inquisitive, and action-oriented. The ultimate outcome of Action Research is to create a plan of action using the research findings to inform future educational practice. A Plan of Action is not meant to be a one-size fits all plan. Instead, it is mean to include specific data-driven and research-based recommendations that result from a detailed analysis of the data, the study findings, and implications of the Action Research study. An effective Plan of Action includes an evaluation component and opportunities for professional educator reflection that allows for authentic discussion aimed at continuous improvement.

When developing a Plan of Action, the following should be considered:

- How can this situation be approached differently in the future?

- What should change in terms of practice?

- What are the specific steps that individuals should take to change practices?

- What is needed to implement the changes being recommended (professional development, training, materials, resources, planning committees, school improvement planning, etc.)?

- How will the effectiveness of the implemented changes be evaluated?

- How will opportunities for professional educator reflection be built into the Action Plan?

Sample Action Research Studies

Anderson, A. J. (2020). A qualitative systematic review of youth participatory action research implementation in U.S. high schools. A merican Journal of Community Psychology, 65 (1/2), 242–257. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy1.ncu.edu/doi/epdf/10.1002/ajcp.12389

Ayvaz, Ü., & Durmuş, S.(2021). Fostering mathematical creativity with problem posing activities: An action research with gifted students. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S1871187121000614&site=eds-live

Bellino, M. J. (2018). Closing information gaps in Kakuma Refugee Camp: A youth participatory action research study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62 (3/4), 492–507. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=133626988&site=eds-live

Beneyto, M., Castillo, J., Collet-Sabé, J., & Tort, A. (2019). Can schools become an inclusive space shared by all families? Learnings and debates from an action research project in Catalonia. Educational Action Research, 27 (2), 210–226. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135671904&site=eds-live

Bilican, K., Senler, B., & Karısan, D. (2021). Fostering teacher educators’ professional development through collaborative action research. International Journal of Progressive Education, 17 (2), 459–472. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=149828364&site=eds-live

Black, G. L. (2021). Implementing action research in a teacher preparation program: Opportunities and limitations. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 21 (2), 47–71. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=149682611&site=eds-live

Bozkuş, K., & Bayrak, C. (2019). The Application of the dynamic teacher professional development through experimental action research. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 11 (4), 335–352. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135580911&site=eds-live

Christ, T. W. (2018). Mixed methods action research in special education: An overview of a grant-funded model demonstration project. Research in the Schools, 25( 2), 77–88. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135047248&site=eds-live

Jakhelln, R., & Pörn, M. (2019). Challenges in supporting and assessing bachelor’s theses based on action research in initial teacher education. Educational Action Research, 27 (5), 726–741. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=140234116&site=eds-live

Klima Ronen, I. (2020). Action research as a methodology for professional development in leading an educational process. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 64 . https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edselp&AN=S0191491X19302159&site=eds-live

Messiou, K. (2019). Collaborative action research: facilitating inclusion in schools. Educational Action Research, 27 (2), 197–209. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=135671898&site=eds-live

Mitchell, D. E. (2018). Say it loud: An action research project examining the afrivisual and africology, Looking for alternative African American community college teaching strategies. Journal of Pan African Studies, 12 (4), 364–487. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=133155045&site=eds-live

Pentón Herrera, L. J. (2018). Action research as a tool for professional development in the K-12 ELT classroom. TESL Canada Journal, 35 (2), 128–139. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ofs&AN=135033158&site=eds-live

Rodriguez, R., Macias, R. L., Perez-Garcia, R., Landeros, G., & Martinez, A. (2018). Action research at the intersection of structural and family violence in an immigrant Latino community: a youth-led study. Journal of Family Violence, 33 (8), 587–596. https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&AN=132323375&site=eds-live

Vaughan, M., Boerum, C., & Whitehead, L. (2019). Action research in doctoral coursework: Perceptions of independent research experiences. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 13 . https://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsdoj&AN=edsdoj.17aa0c2976c44a0991e69b2a7b4f321&site=eds-live

Sample Journals for Action Research

Educational Action Research

Canadian Journal of Action Research

Sample Resource Videos

Call-Cummings, M. (2017). Researching racism in schools using participatory action research [Video]. Sage Research Methods http://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?URL=https://methods.sagepub.com/video/researching-racism-in-schools-using-participatory-action-research

Fine, M. (2016). Michelle Fine discusses community based participatory action research [Video]. Sage Knowledge. http://proxy1.ncu.edu/login?URL=https://sk-sagepub-com.proxy1.ncu.edu/video/michelle-fine-discusses-community-based-participatory-action-research

Getz, C., Yamamura, E., & Tillapaugh. (2017). Action Research in Education. [Video]. You Tube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2tso4klYu8

Bradbury, H. (Ed.). (2015). The handbook of action research (3rd edition). Sage.

Bradbury, H., Lewis, R. & Embury, D.C. (2019). Education action research: With and for the next generation. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Bourner, T., & Brook, C. (2019). Comparing and contrasting action research and action learning. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Bradbury, H. (2015). The Sage handbook of action research . Sage. https://www-doi-org.proxy1.ncu.edu/10.4135/9781473921290

Dosemagen, D.M. & Schwalback, E.M. (2019). Legitimacy of and value in action research. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Johnson, A. (2019). Action research for teacher professional development. In C.A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (1st edition). John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/reader.action?docID=5683581&ppg=205

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. In G.W. Lewin (Ed.), Resolving social conflicts: Selected papers on group dynamics (compiled in 1948). Harper and Row.

Mertler, C. A. (Ed.). (2019). The Wiley handbook of action research in education. John Wiley and Sons. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nu/detail.action?docID=5683581

- << Previous: Qualitative Narrative Inquiry Research

- Next: Case Study Design in an Applied Doctorate >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2023 8:05 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/c.php?g=1013605

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

Field Study 2 (e-Portfolio)

MY FIELD STUDY LEARNING EXPERIENCE E-PORTFILIO Participation and teaching assistanship Mr. JEROME JEFF M. ZAMORA

09390509725 [email protected] Arnold Manalo

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

First and foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my Field Study Adviser Sir Jerome Jeff M. Zamora for the continuous support during my Field Study for the patience, motivation enthusiasm and immense knowledge. And also to my dearest friend thank you for supporting me to accomplish my field study. To all my teachers, classmates and friends to all the Filipino Major thank you for the love and guidance and also to encourage me to complete and finish me for this e-portfolio. Finally I would like to thank my family for their untiring support, financial, assistance for their love, care advice encouragement to make my field study.

AUTHORS BIOGRAPHY

My name is Arnold Manalo and I am currently a College student pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Education Major in Filipino. I have been able to find opportunities that have and will continue to help me gain knowledge and advance my career. As a student, I have received national Certificate for Tesda the Housekeeping NCII and also the Event Management NCIII. I received TERTIARY EDCATION SUBSIDY Scholarship and was recognized by Mindoro State University for outstanding academic achievement. As a College of Teacher Education student. Our name parents Jesus A. Manalo and Luciana A. Manalo among sibling I am the youngest brother 4 sister and 3 brothers. They currently residing at Ma. Concepcion Socorro Oriental Mindoro I love this job and I would be happy to work as a teacher .Ten years from now hopefully I will become a great teacher over the years someone the students will remember good means , like someone who had a good impact to them. I see myself as a good role model for many children ideally working at school .And I believe I know with confidence, that I will be a good educator even with human imperfection and yet I will try to do the best I can be. Future generation will truly be aggressive learners. It’s very hard to handle them especially that they are exposing much to the world through internet and even the wild society. Because my goal is to change them, a very challenging part, I should really have to start changing myself that leads me to totally be human. As the saying goes “You cannot give what you don’t have”. So, it is very impossible to impart learning to your students when even yourself you don’t have a very good learning. So, with that, I can be able to be an example to them. I would also want to stress out that in handling my students, I will not be the old school teacher who will just shout and spank their students who are doing inappropriate things. I will be calm in handling them. Be mindful about why such student is acting inappropriately or even check his/her background. After that, I will be pushing to what is the right procedure to change his/her way. I will not just be a teacher to them but also a friend. I believe that when you impart friendship to your students, they will build confidence .And also I must work very hard and I embrace these struggles and learn from them. I am driven by determination and I am passionate in almost everything I do. And now I might have them accomplished my goals today and I had created new dreams for the future. Education is the key to success and without education where would we be today tomorrow or next week or next year. School is where we get our education and me being a teacher I can keep new learning information everyday as well.

Table of contents 1.THE TEACHER WE REMEMBER 2.EMBEDDING ACTION RESEARCH FOR REFLECTIVE TEACHING 3.UNDERSTANDING AR CONCEPTS, PROCESS AND MODELS 4. PROBLEMATIC LEARNING SITUATION 5.PREPARING THE LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS AN OVERVIEW

FIELD STUDY 2

LEARNING EPISODE

The Teacher We Remember

Analyze 1. From the PPSTs, the Southeast Asia Teachers Competency Standards and the TEDx videos that you viewed; what competencies does a great teacher possess? From the video that I watched there are many competencies that a teacher should possess. Philippine Professional Standards for Teachers (PPSTs) great teachers never stop learning teacher always helps the student to learn and also to share the knowledge and learning is very important teacher are responsible for maintaining a positive learning environment in the classroom. Managing is not easy task. Teachers must implement structure, develop positive student’s interaction and take immediate action when problem arise. And also the primary role of the teacher is to deliver classroom instruction that helps student learn. To accomplish this teachers must prepare effective lesson grade student work and offer feedback, manage classroom materials productively. Student’s needs are deficit in specific skills that impede academic, physical, and behavioural and self-help activities. Students need are determined by teachers or others professionals sometimes through formal assessments. Student needs can be effectively addressed through appropriate teaching strategies. 2. Are these competencies limited only to professional competencies? Professional competencies are skills, knowledge and attributes that are specifically valued by the professional associations organizations bodies connected to your future career. 3. For a teacher to be great, is it enough to possess the professional competencies to plan a lesson, execute a lesson plan, manage a class, assess learning, compute, and report grades? Explain your answer. A great teacher can stop exploring new things teacher checks to see if his or her students are learning effectively. Possessing the knowledge isn't enough. Professional abilities to organize a lesson, carry it out, manage a class, and assess it. Calculate grades while learning. If pupils understand how to pursue what they are interested in, they will be successful. They learned as a result of their professors' impact. If the teachers are able to put the theory into practice, a great teacher checks to see if the kids are learning properly. Possessing the knowledge is not enough. Professional abilities to organize a lesson, carry it out, manage a class, and assess it

4. For a teacher to be great, which is more important - personal qualities or professional Competencies? For me I think both personal qualities and professional Competencies are required for teacher because personal qualities or professional have a great impact for the learning process of the students. 5. Who are the teachers that we remember most? For me the we remember the most is the teacher who has unique a style of a teaching and learning process and the teacher who is a good personality. For me all the teachers can be remember of the student or give a positive feedback every time to do a tasks. As a teacher if your students give comment suggestions if the student giving a feedback comment suggestion of the teachers the student can improve and also help motivate in our learning. Students often remember teachers who were kind or funny or brilliant or passionate. They remember teachers who cared about them. They remember teachers who were supportive or encouraging our saw something in them no one else did. They remember teacher who challenges them and made them think. A giving feedback is important to all for effective learning.

Reflect Which personal traits do I possess? Not possess? Where do I need improvement in? As a future teacher I need to improve for being a more flexible .Why? Because as a future teacher someday I can teach my students properly and be given comprehensive information.

Which professional competencies am I strongly capable of demonstrating? -Critical thinking and creative problem solving. Exercise sound reasoning to analyse issues making decisions and solve problem. In which competencies do I need to develop more? -Competence development is the practice of developing one or several competencies in a specific way and in particular direction. Development refers to improving existing competencies ways to accomplishing this include targeted exercise gaining additional knowledge and changing your attitude. Who are the teachers that we remember most? -For me all the teachers can be remember of the student or give a positive feedback every time to do a tasks. As a teacher if your students give comment suggestions if the student giving a feedback comment suggestion of the teachers the student can improve and also help motivate in our learning. Students often remember teachers who were kind or funny or brilliant or passionate. They remember teachers who cared about them. They remember teachers who were supportive or encouraging our saw something in them no

one else did. They remember teacher who challenges them and made them think. A giving feedback is important to all for effective learning.

FIELD STUDY 2 FS 2

LEARNING EPISODE 2

Embedding Action Research for Reflective Teaching

Participate and Assists Making a List Completed Action Research Titles by Teachers in the Field 1. Make a library or on-line search of the different Completed Action Research Titles Conducted by Teachers. 2. Enter the list in the matrix similar to the one below. 3. Submit your list of five (5) Titles of Completed Action Research Studies to your mentor as reference. Inventory of Sample Action Research Conducted by Teachers List of Completed Action Research Titles Ex. Differentiated Instruction in Teaching English for Grade Four Classes 1. The effects of goal setting on the student work completion in a lower elementary Montessori Classroom.

Author/Authors Mary Joy Olicia Amy Pommereau

2.Effects of mindfulness on Teacher stress and Self Efficacy

April Netz Lauren Rom

3. The Effects of Teacher Centered Of Coaching On Whole class Transition.

Siobhan Sullivan

4. Behavioral Effects of Outdoor Learning Primary Students.

Makena Cameron and Samantha McGUE

5. The Effects of Song on Social Emotional Literacy in an early Childhood Classroom.

Notice Based on your activity on making a List of Completed Action Research Titles, let’s find out what you have noticed by answering the following questions Questions

1. What have you noticed about the action research titles? Do the action research (AR) titles imply problems to be solved? Yes. ___ No. ___

Identified problem to be solved in title no. 1

If YES, identify the problems from the little you have given. Answer in the space provided.

Identified problem to be solved in title no. 2

Effects of goal setting on the student work completion in a lower elementary Montessori Classroom.

Mindfulness on Teacher stress and Self Efficacy . Identified problem to be solved in title no. 3 Effects of Teacher Centered Of Coaching On Whole class Transition. Identified problem to be solved in title no. 4 Effects of Outdoor Learning Primary Students.

Identified problem to be solved in title no. 5 Effects of Song on Social Emotional Literacy in an early Childhood Classroom. ` 2. What interpretation about action research can you make out of your answer in Question No. 1?

Title of the Action Research: The effects of goal setting on the student work completion in a lower

elementary Montessori Classroom.

3. Write the title and your interpretation of the study from the title.

4. What do you think did the author’s do with the identified problem as presented in their titles?

From the tittle I think the study is all about the goal setting on the student work completion in Elementary And also the social expectations of the children. Some epectations include moving through a learning space without learning And also students decide which activity to engage on based on the interests. Because students are working on a different activities in different areas on the curriculum in different places in the classroom the classroom comes is a busy place. I think the author/s Amy Pommereau are must presented the tittle Through the observation of the teacher and also the goal setting of the student work. In a good way the teacher can analyze the different issues of the student to help the student and to improve the performance and ability.

Analyze Action research seems easy and familiar. Since teaching seems to be full of problematic situations and that the teacher has a responsibility of finding solution for everyday problems in school, hence teachers should do action research. This is an exciting part of being a teacher, a problem solver! Let us continue to examine and analyze what you have noticed and interpreted in the previous activity. 1. From what source do you think, did the authors identify the problems of their action research?

Choices: ____ Copied from research books ____ From daily observation of their teaching practice. __/_ From difficulties they observed of their learners. __/__ From their own personal experience. ____ From the told experiences of their coteachers.

2. What do you think is the teacher’s intention in conducting the action research?

3. What benefit do you get as a student in FS 2 in understanding and doing action research?

4. In what ways, can you assist your mentor in his/her Action Research Activity?

Choices: __/__ To find a solution to the problematic situation ____ To comply with the requirement of the principal __/__ To improve teaching practice ____ To try out something, if it works ____ To prove oneself as better than the others Choices: __/__ Prepare me for my future job ____ Get good grades in the course __/__ Learn and practice being an action researcher __/__ Improve my teaching practice ____ Exposure to the realities in the teaching profession __/__ Become a better teacher everyday Choices __/__ By co-researching with my mentor __/__ By assisting in the design of the intervention __/__ By assisting in the implementation of the AR ____By just watching what is being done

Reflect Based on the readings you made and the previous activities that you have done,

1. What significant ideas or concepts have you learned about action research? I learned that the action research is a helpful resource why? Because most of the teacher can analyze and identify the problem of the student inside the classroom or the classroom management. As I observe the teacher can identify the different problems inside the classroom. Action research present a good ideas. We have found that setting up small collaborative and effective. And apply the different strategies.

2. Have you realized that there is need to be an action researcher as future teacher? Yes_ No_. If yes, complete the sentence below. Yes I realized action research are needs as a future teacher because in this action research it helps me to improve my teaching skills. In that way as a future teacher someday I can share my knowledge to my student.

Write Action Research Prompts OBSERVE I have observe and notice that Action Research begins with the problems. From what teaching principles of theories can this problem be anchored? I have observed and noticed that Action Research begins with a problem or a problematic situation. Write an example of a problematic situation that you have observed and noticed.

REFLECT What I have realized? What do I hope to achieve? I realize that for every teaching learning problem, this is a solution. Write a probable solution to the problematic situation above

PLAN What strategies, activities, and innovations can I employ to improve the situations or solve the problem?

As a future action researcher I can plan for an appropriate intervention I can show the different strategies for teaching so that the student will be more motivated and interested during the discussion.

ACT If I conduct or implement my plan, what can be its title?

If I will implement my double plan in the future, my title would be Effectiveness of Speaking Proficiency Of grade 9 students. Speaking skills, especially effective public speaking skill are important as listening skills and they form an integral part of interpersonal communication. Overall, these skills help you boost your confidence, win people’s heart and communicate effectively. One does not simply become speaker someday.

Your artifact will be an Abstract of a completed action research.

Abstract This investigation explored if and how direct instruction on goal-setting and working toward a goal over a four-week period impacted the number of activities students independently completed in class. The amount of math and language work completed and the way the participants felt about their ability to manage their time and goals were measured and evaluated. The study took place at a diverse elementary school in the Midwest. The classroom involved is the only Montessori lower elementary classroom in the district. The 26 students were ages 6-9 at the time of the study. Students were taught how to set a goal and work toward that goal. They also planned for challenges and how to overcome those challenges. Students checked in with their teacher and peers daily to reflect and report how focused they were in regards to achieving the goal they set. Students were observed, data was collected about the type and amount of work completed, students were rated by a peer accountability partner daily, and students completed a pre and post-self-assessment about setting goals and how competent they felt in doing so. The results of the study showed that while the amount of work did not increase, students reported feeling more confident in their ability to set goals and use strategies to stay on task and on-task behavior increased. Direct instruction in goal setting enabled students to feel more confident in selecting a goal and working toward it. They gained tools for staying focused during work times. They were able to use these tools to be on task more frequently than before the intervention. Teachers may want to choose to include direct goal setting in their practice. Further studies may want to track data for a longer period of time to see if work output also would increase. Recommended Citation Pommereau, Amy. (2020). The Effects of Goal Setting on Student Work Completion in a Lower Elementary Montessori Classroom. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/maed/359

Understanding AR Concepts, Processes and Models

Choose the AR sample Abstract that you submitted in Episode 2. Analyze the components vis-s-vis only one model out of the 3 presented.

If you choose to compare with Model B-Nelson, O. 2014, here are the components. Title and Author of the Action Research: The effects of goal setting on the student work completion in a lower elementary Montessori Classroom. Key Components

Entry you Sample AR The Problem Prior to my intervention I had observed that students lacked direction when it came to setting goals and working toward those goals in the classroom. Students often had unproductive work time because they were socializing with others in ways unrelated to work, wandering around the classroom, or were not using their time efficiently. This led to instead taking longer than necessary to complete work. I wondered if teaching goal-setting skills to students would enable them to have more focused, structured, and productive work time. Would they become more productive? Would they feel more capable and confident about their work choices? Students were taught how to set a goal, what may distract them from meeting their goals, and what to do if they faced challenges in meeting their goals. Students then created their own goals

for the next four weeks. Each morning I met with individual students and we reviewed their goal. They met with an accountability partner each afternoon. Partners rated each other on work completion and staying on task after engaging in dialogue with each other. Students were encouraged to self-reflect on the scores they received each day. The data illustrated that students either demonstrated or reported positive or no changes during the course of the intervention. One conclusion that can be made from this research is that direct instruction of goal setting increases on-task behavior over time. Periodically throughout our morning work time, I woud observe the activity of the children and record if behaviors were on task (engaging in work or receiving help) or off task (disrupting, wandering, interrupting others). The average number of children demonstrating on-task behavior over the course of this 4-week study increased by 19.7%. The number of off-task behavior decreased by 55% from week 1 to week 4. This may be due to increased motivation; something that supported goal setting can lead to (Forester & Souvignier, 2014).

Reflection The researcher addressed in improving students lacked direction when it came to setting goals and working toward those goals in the classroom. Students often had unproductive work time because they were socializing with others in ways unrelated to work, wandering around the classroom, or were not using their time efficiently.

Plan of Action The study gave evidence to suggest that teaching children goal setting through direct instruction, teacher guidance, and peer accountability positively impacts students’ self-perception about their ability to set goals and successfully obtain those goals in the classroom. While teachers are charged with improving their students’ academic abilities, they are also responsible for supporting students’ positive perception on themselves as learners and supporting the emotional growth of the child. This study suggested that the interventions given positively impacted students’ perception of their ability to set and meet goals. It was an empowering experience for my students. I believe such an impact will lead to positive academic changes long term. Giving children these lessons may positively influence them to become life-long, competent seekers-of-knowledge.

Implementation My students became more fluent in their ability to set a goal. They are demonstrating more focus in working toward their goals. They have also gained an understanding of goal obstacles and how to thwart them through an increase of self-awareness. I noticed changes in their behavior that led to more on-task behavior. Students were more careful about who they sat next to and when. Some chose to sit at one-person spots. Some chose to wear noise-canceling headphones, while others requested silent work time. While students are gaining self-awareness and strategies to protect their concentration independently, I feel the next step would be to provide more direct instruction with how to maintain that level of focus during group work. I have questions about where this research could lead. Expanding the study to include a greater sample size and age range would be beneficial. Based on the development of executive functioning skills during specific periods of a child’s growth (Anderson, 2002), I wonder if the impact would be great on upper elementary students (9-12-year-olds). I suggest the study be repeated with lower and upper elementary classrooms. There could be more interesting comparisons made between the two age groups as far as the effectiveness of the study. Twentysix is a small sample size, so including more children could lead to more accurate data. I feel the amount of time I had to collect data was not long enough, especially factoring in that there was a weeklong school break between weeks 3 and 4. Once the children had returned to school for week four, 2 backto-back snow days further interrupted the study and data collection process. Expanding the period for data collection may show changes in the amount of work completed over time. I would have also liked to return to the WOOP work that the children had done at the beginning of the intervention. I feel that revisiting their plans of what they would do to overcome obstacles would have benefited my students by giving them a concrete touch point.

What have you understood about the concept of Action Research and how will these is utilized in your practices? Action research is a process for improving educational practice. Its methods involve action, evaluation, and reflection. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices. ... Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice.

As an action researcher, or teacher-researcher, you will generate research. Enquiring into your practice will inevitably lead you to question the assumptions and values that are often overlooked during the course of normal school life. Assuming the habit of inquiry can become an ongoing commitment to learning and developing as a practitioner. As a teacher-researcher you assume the responsibility for being the agent and source of change.

Reflect As a future teacher, is conducting an Action Research worth doing? For me yes because as a future teacher action research worth doing. Why? Because inside the classroom they have many problem inside the classroom and they find the solution on the different problem. So that the teacher can be conduct the action research. And also help them to improving their teaching skill and ability. How can AR useful for every classroom teacher? Action research can be useful for every classroom because they have a problem in every classroom but they can find a solution. It is a process to gather evidence to implement change in practices. ... Action research can be based in problem-solving, if the solution to the problem results in the improvement of practice. As an action researcher, or teacher-researcher, you will generate research. Enquiring into your practice will inevitably lead you to question the assumptions and values that are often overlooked during the course of normal school life