The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

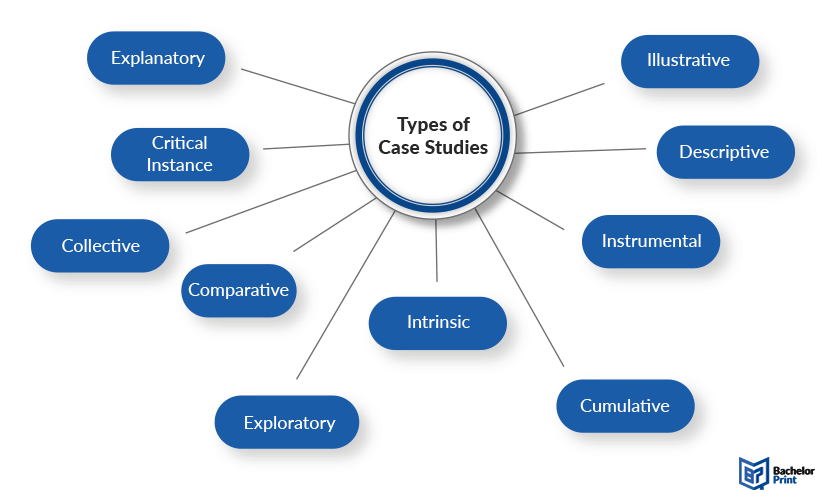

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

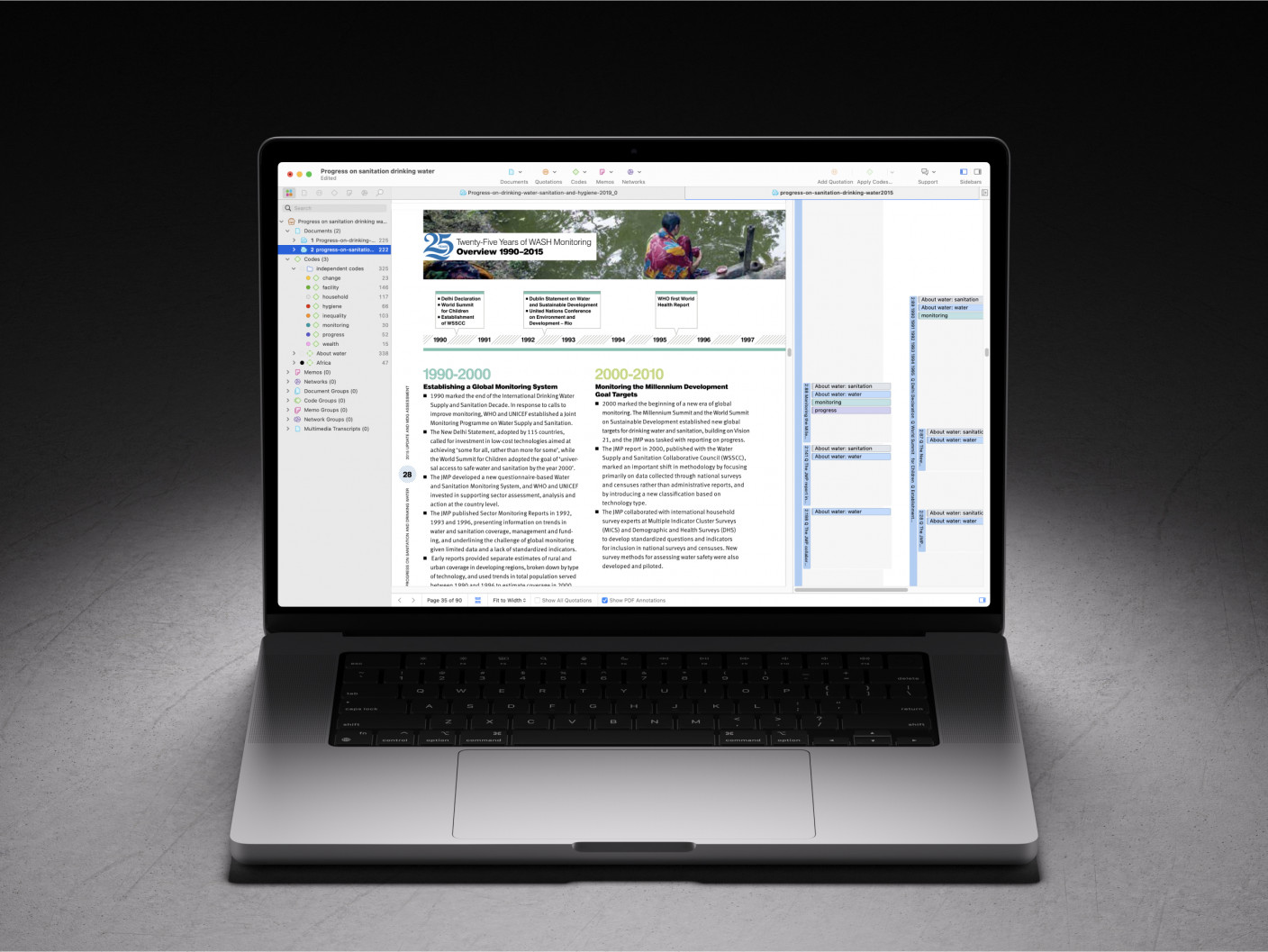

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

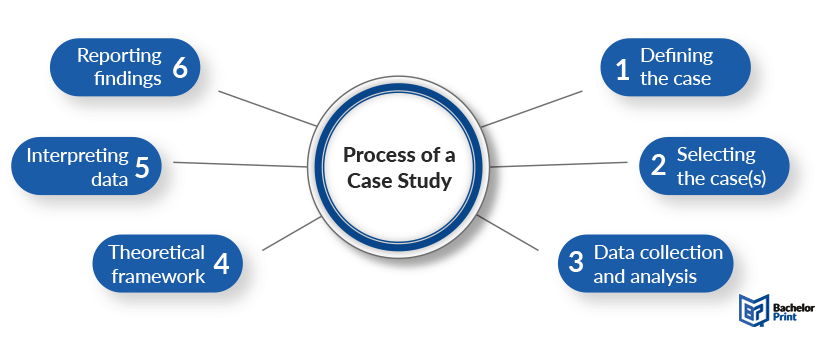

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved July 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Transformative Design – Methods, Types, Guide

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The case study creation process

Types of case studies, benefits and limitations.

- When did science begin?

- Where was science invented?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Academia - Case Study

- Verywell Mind - What is a Case Study?

- Simply Psychology - Case Study Research Method in Psychology

- CORE - Case study as a research method

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - The case study approach

- BMC Journals - Evidence-Based Nursing - What is a case study?

- Table Of Contents

case study , detailed description and assessment of a specific situation in the real world created for the purpose of deriving generalizations and other insights from it. A case study can be about an individual, a group of people, an organization, or an event, among other subjects.

By focusing on a specific subject in its natural setting, a case study can help improve understanding of the broader features and processes at work. Case studies are a research method used in multiple fields, including business, criminology , education , medicine and other forms of health care, anthropology , political science , psychology , and social work . Data in case studies can be both qualitative and quantitative. Unlike experiments, where researchers control and manipulate situations, case studies are considered to be “naturalistic” because subjects are studied in their natural context . ( See also natural experiment .)

The creation of a case study typically involves the following steps:

- The research question to be studied is defined, informed by existing literature and previous research. Researchers should clearly define the scope of the case, and they should compile a list of evidence to be collected as well as identify the nature of insights that they expect to gain from the case study.

- Once the case is identified, the research team is given access to the individual, organization, or situation being studied. Individuals are informed of risks associated with participation and must provide their consent , which may involve signing confidentiality or anonymity agreements.

- Researchers then collect evidence using multiple methods, which may include qualitative techniques, such as interviews, focus groups , and direct observations, as well as quantitative methods, such as surveys, questionnaires, and data audits. The collection procedures need to be well defined to ensure the relevance and accuracy of the evidence.

- The collected evidence is analyzed to come up with insights. Each data source must be reviewed carefully by itself and in the larger context of the case study so as to ensure continued relevance. At the same time, care must be taken not to force the analysis to fit (potentially preconceived) conclusions. While the eventual case study may serve as the basis for generalizations, these generalizations must be made cautiously to ensure that specific nuances are not lost in the averages.

- Finally, the case study is packaged for larger groups and publication. At this stage some information may be withheld, as in business case studies, to allow readers to draw their own conclusions. In scientific fields, the completed case study needs to be a coherent whole, with all findings and statistical relationships clearly documented.

Case studies have been used as a research method across multiple fields. They are particularly popular in the fields of law, business, and employee training; they typically focus on a problem that an individual or organization is facing. The situation is presented in considerable detail, often with supporting data, to discussion participants, who are asked to make recommendations that will solve the stated problem. The business case study as a method of instruction was made popular in the 1920s by instructors at Harvard Business School who adapted an approach used at Harvard Law School in which real-world cases were used in classroom discussions. Other business and law schools started compiling case studies as teaching aids for students. In a business school case study, students are not provided with the complete list of facts pertaining to the topic and are thus forced to discuss and compare their perspectives with those of their peers to recommend solutions.

In criminology , case studies typically focus on the lives of an individual or a group of individuals. These studies can provide particularly valuable insight into the personalities and motives of individual criminals, but they may suffer from a lack of objectivity on the part of the researchers (typically because of the researchers’ biases when working with people with a criminal history), and their findings may be difficult to generalize.

In sociology , the case-study method was developed by Frédéric Le Play in France during the 19th century. This approach involves a field worker staying with a family for a period of time, gathering data on the family members’ attitudes and interactions and on their income, expenditures, and physical possessions. Similar approaches have been used in anthropology . Such studies can sometimes continue for many years.

Case studies provide insight into situations that involve a specific entity or set of circumstances. They can be beneficial in helping to explain the causal relationships between quantitative indicators in a field of study, such as what drives a company’s market share. By introducing real-world examples, they also plunge the reader into an actual, concrete situation and make the concepts real rather than theoretical. They also help people study rare situations that they might not otherwise experience.

Because case studies are in a “naturalistic” environment , they are limited in terms of research design: researchers lack control over what they are studying, which means that the results often cannot be reproduced. Also, care must be taken to stay within the bounds of the research question on which the case study is focusing. Other limitations to case studies revolve around the data collected. It may be difficult, for instance, for researchers to organize the large volume of data that can emerge from the study, and their analysis of the data must be carefully thought through to produce scientifically valid insights. The research methodology used to generate these insights is as important as the insights themselves, for the latter need to be seen in the proper context. Taken out of context, they may lead to erroneous conclusions. Like all scientific studies, case studies need to be approached objectively; personal bias or opinion may skew the research methods as well as the results. ( See also confirmation bias .)

Business case studies in particular have been criticized for approaching a problem or situation from a narrow perspective. Students are expected to come up with solutions for a problem based on the data provided. However, in real life, the situation is typically reversed: business managers face a problem and must then look for data to help them solve it.

Case Study Methods and Examples

By Janet Salmons, PhD Manager, Sage Research Methods Community

What is Case Study Methodology ?

Case studies in research are both unique and uniquely confusing. The term case study is confusing because the same term is used multiple ways. The term can refer to the methodology, that is, a system of frameworks used to design a study, or the methods used to conduct it. Or, case study can refer to a type of academic writing that typically delves into a problem, process, or situation.

Case study methodology can entail the study of one or more "cases," that could be described as instances, examples, or settings where the problem or phenomenon can be examined. The researcher is tasked with defining the parameters of the case, that is, what is included and excluded. This process is called bounding the case , or setting boundaries.

Case study can be combined with other methodologies, such as ethnography, grounded theory, or phenomenology. In such studies the research on the case uses another framework to further define the study and refine the approach.

Case study is also described as a method, given particular approaches used to collect and analyze data. Case study research is conducted by almost every social science discipline: business, education, sociology, psychology. Case study research, with its reliance on multiple sources, is also a natural choice for researchers interested in trans-, inter-, or cross-disciplinary studies.

The Encyclopedia of case study research provides an overview:

The purpose of case study research is twofold: (1) to provide descriptive information and (2) to suggest theoretical relevance. Rich description enables an in-depth or sharpened understanding of the case.

It is unique given one characteristic: case studies draw from more than one data source. Case studies are inherently multimodal or mixed methods because this they use either more than one form of data within a research paradigm, or more than one form of data from different paradigms.

A case study inquiry could include multiple types of data:

multiple forms of quantitative data sources, such as Big Data + a survey

multiple forms of qualitative data sources, such as interviews + observations + documents

multiple forms of quantitative and qualitative data sources, such as surveys + interviews

Case study methodology can be used to achieve different research purposes.

Robert Yin , methodologist most associated with case study research, differentiates between descriptive , exploratory and explanatory case studies:

Descriptive : A case study whose purpose is to describe a phenomenon. Explanatory : A case study whose purpose is to explain how or why some condition came to be, or why some sequence of events occurred or did not occur. Exploratory: A case study whose purpose is to identify the research questions or procedures to be used in a subsequent study.

Robert Yin’s book is a comprehensive guide for case study researchers!

You can read the preface and Chapter 1 of Yin's book here . See the open-access articles below for some published examples of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods case study research.

Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (2010). Encyclopedia of case study research (Vols. 1-0). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412957397

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Open-Access Articles Using Case Study Methodology

As you can see from this collection, case study methods are used in qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods research.

Ang, C.-S., Lee, K.-F., & Dipolog-Ubanan, G. F. (2019). Determinants of First-Year Student Identity and Satisfaction in Higher Education: A Quantitative Case Study. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019846689

Abstract. First-year undergraduates’ expectations and experience of university and student engagement variables were investigated to determine how these perceptions influence their student identity and overall course satisfaction. Data collected from 554 first-year undergraduates at a large private university were analyzed. Participants were given the adapted version of the Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education Survey to self-report their learning experience and engagement in the university community. The results showed that, in general, the students’ reasons of pursuing tertiary education were to open the door to career opportunities and skill development. Moreover, students’ views on their learning and university engagement were at the moderate level. In relation to student identity and overall student satisfaction, it is encouraging to state that their perceptions of studentship and course satisfaction were rather positive. After controlling for demographics, student engagement appeared to explain more variance in student identity, whereas students’ expectations and experience explained greater variance in students’ overall course satisfaction. Implications for practice, limitations, and recommendation of this study are addressed.

Baker, A. J. (2017). Algorithms to Assess Music Cities: Case Study—Melbourne as a Music Capital. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017691801

Abstract. The global Mastering of a Music City report in 2015 notes that the concept of music cities has penetrated the global political vernacular because it delivers “significant economic, employment, cultural and social benefits.” This article highlights that no empirical study has combined all these values and offers a relevant and comprehensive definition of a music city. Drawing on industry research,1 the article assesses how mathematical flowcharts, such as Algorithm A (Economics), Algorithm B (Four T’s creative index), and Algorithm C (Heritage), have contributed to the definition of a music city. Taking Melbourne as a case study, it illustrates how Algorithms A and B are used as disputed evidence about whether the city is touted as Australia’s music capital. The article connects the three algorithms to an academic framework from musicology, urban studies, cultural economics, and sociology, and proposes a benchmark Algorithm D (Music Cities definition), which offers a more holistic assessment of music activity in any urban context. The article concludes by arguing that Algorithm D offers a much-needed definition of what comprises a music city because it builds on the popular political economy focus and includes the social importance of space and cultural practices.

Brown, K., & Mondon, A. (2020). Populism, the media, and the mainstreaming of the far right: The Guardian’s coverage of populism as a case study. Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395720955036

Abstract. Populism seems to define our current political age. The term is splashed across the headlines, brandished in political speeches and commentaries, and applied extensively in numerous academic publications and conferences. This pervasive usage, or populist hype, has serious implications for our understanding of the meaning of populism itself and for our interpretation of the phenomena to which it is applied. In particular, we argue that its common conflation with far-right politics, as well as its breadth of application to other phenomena, has contributed to the mainstreaming of the far right in three main ways: (1) agenda-setting power and deflection, (2) euphemisation and trivialisation, and (3) amplification. Through a mixed-methods approach to discourse analysis, this article uses The Guardian newspaper as a case study to explore the development of the populist hype and the detrimental effects of the logics that it has pushed in public discourse.

Droy, L. T., Goodwin, J., & O’Connor, H. (2020). Methodological Uncertainty and Multi-Strategy Analysis: Case Study of the Long-Term Effects of Government Sponsored Youth Training on Occupational Mobility. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique, 147–148(1–2), 200–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0759106320939893

Abstract. Sociological practitioners often face considerable methodological uncertainty when undertaking a quantitative analysis. This methodological uncertainty encompasses both data construction (e.g. defining variables) and analysis (e.g. selecting and specifying a modelling procedure). Methodological uncertainty can lead to results that are fragile and arbitrary. Yet, many practitioners may be unaware of the potential scale of methodological uncertainty in quantitative analysis, and the recent emergence of techniques for addressing it. Recent proposals for ‘multi-strategy’ approaches seek to identify and manage methodological uncertainty in quantitative analysis. We present a case-study of a multi-strategy analysis, applied to the problem of estimating the long-term impact of 1980s UK government-sponsored youth training. We use this case study to further highlight the problem of cumulative methodological fragilities in applied quantitative sociology and to discuss and help develop multi-strategy analysis as a tool to address them.

Ebneyamini, S., & Sadeghi Moghadam, M. R. (2018). Toward Developing a Framework for Conducting Case Study Research . International Journal of Qualitative Methods . https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918817954

Abstract. This article reviews the use of case study research for both practical and theoretical issues especially in management field with the emphasis on management of technology and innovation. Many researchers commented on the methodological issues of the case study research from their point of view thus, presenting a comprehensive framework was missing. We try representing a general framework with methodological and analytical perspective to design, develop, and conduct case study research. To test the coverage of our framework, we have analyzed articles in three major journals related to the management of technology and innovation to approve our framework. This study represents a general structure to guide, design, and fulfill a case study research with levels and steps necessary for researchers to use in their research.

Lai, D., & Roccu, R. (2019). Case study research and critical IR: the case for the extended case methodology. International Relations , 33 (1), 67-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117818818243

Abstract. Discussions on case study methodology in International Relations (IR) have historically been dominated by positivist and neopositivist approaches. However, these are problematic for critical IR research, pointing to the need for a non-positivist case study methodology. To address this issue, this article introduces and adapts the extended case methodology as a critical, reflexivist approach to case study research, whereby the case is constructed through a dynamic interaction with theory, rather than selected, and knowledge is produced through extensions rather than generalisation. Insofar as it seeks to study the world in complex and non-linear terms, take context and positionality seriously, and generate explicitly political and emancipatory knowledge, the extended case methodology is consistent with the ontological and epistemological commitments of several critical IR approaches. Its potential is illustrated in the final part of the article with reference to researching the socioeconomic dimension of transitional justice in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Lynch, R., Young, J. C., Boakye-Achampong, S., Jowaisas, C., Sam, J., & Norlander, B. (2020). Benefits of crowdsourcing for libraries: A case study from Africa . IFLA Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035220944940

Abstract. Many libraries in the Global South do not collect comprehensive data about themselves, which creates challenges in terms of local and international visibility. Crowdsourcing is an effective tool that engages the public to collect missing data, and it has proven to be particularly valuable in countries where governments collect little public data. Whereas crowdsourcing is often used within fields that have high levels of development funding, such as health, the authors believe that this approach would have many benefits for the library field as well. They present qualitative and quantitative evidence from 23 African countries involved in a crowdsourcing project to map libraries. The authors find benefits in terms of increased connections between stakeholders, capacity-building, and increased local visibility. These findings demonstrate the potential of crowdsourced approaches for tasks such as mapping to benefit libraries and similarly positioned institutions in the Global South in multifaceted ways.

Mason, W., Morris, K., Webb, C., Daniels, B., Featherstone, B., Bywaters, P., Mirza, N., Hooper, J., Brady, G., Bunting, L., & Scourfield, J. (2020). Toward Full Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Methods in Case Study Research: Insights From Investigating Child Welfare Inequalities. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14 (2), 164-183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689819857972

Abstract. Delineation of the full integration of quantitative and qualitative methods throughout all stages of multisite mixed methods case study projects remains a gap in the methodological literature. This article offers advances to the field of mixed methods by detailing the application and integration of mixed methods throughout all stages of one such project; a study of child welfare inequalities. By offering a critical discussion of site selection and the management of confirmatory, expansionary and discordant data, this article contributes to the limited body of mixed methods exemplars specific to this field. We propose that our mixed methods approach provided distinctive insights into a complex social problem, offering expanded understandings of the relationship between poverty, child abuse, and neglect.

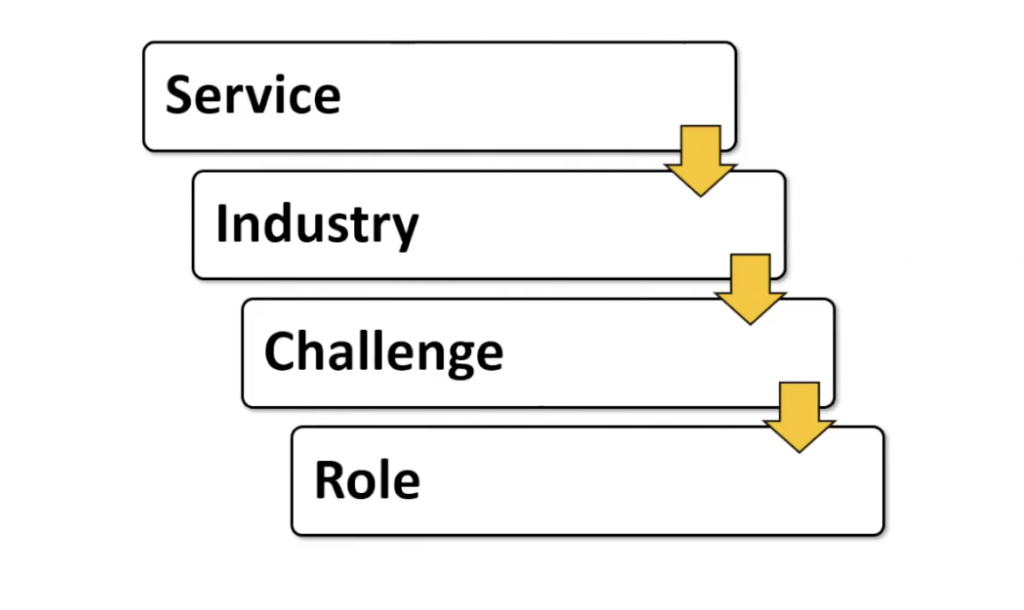

Rashid, Y., Rashid, A., Warraich, M. A., Sabir, S. S., & Waseem, A. (2019). Case Study Method: A Step-by-Step Guide for Business Researchers . International Journal of Qualitative Methods . https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919862424

Abstract. Qualitative case study methodology enables researchers to conduct an in-depth exploration of intricate phenomena within some specific context. By keeping in mind research students, this article presents a systematic step-by-step guide to conduct a case study in the business discipline. Research students belonging to said discipline face issues in terms of clarity, selection, and operationalization of qualitative case study while doing their final dissertation. These issues often lead to confusion, wastage of valuable time, and wrong decisions that affect the overall outcome of the research. This article presents a checklist comprised of four phases, that is, foundation phase, prefield phase, field phase, and reporting phase. The objective of this article is to provide novice researchers with practical application of this checklist by linking all its four phases with the authors’ experiences and learning from recently conducted in-depth multiple case studies in the organizations of New Zealand. Rather than discussing case study in general, a targeted step-by-step plan with real-time research examples to conduct a case study is given.

VanWynsberghe, R., & Khan, S. (2007). Redefining Case Study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690700600208

Abstract. In this paper the authors propose a more precise and encompassing definition of case study than is usually found. They support their definition by clarifying that case study is neither a method nor a methodology nor a research design as suggested by others. They use a case study prototype of their own design to propose common properties of case study and demonstrate how these properties support their definition. Next, they present several living myths about case study and refute them in relation to their definition. Finally, they discuss the interplay between the terms case study and unit of analysis to further delineate their definition of case study. The target audiences for this paper include case study researchers, research design and methods instructors, and graduate students interested in case study research.

More Sage Research Methods Community Posts about Case Study Research

Use research cases as the basis for individual or team activities that build skills.

Find an 10-step process for using research cases to teach methods with learning activities for individual students, teams, or small groups. (Or use the approach yourself!)

How do you decide which methodology fits your study? In this dialogue Linda Bloomberg and Janet Boberg explain the importance of a strategic approach to qualitative research design that stresses alignment with the purpose of the study.

Case study methods are used by researchers in many disciplines. Here are some open-access articles about multimodal qualitative or mixed methods designs that include both qualitative and quantitative elements.

Case study methodology is both unique, and uniquely confusing. It is unique given one characteristic: case studies draw from more than one data source.

What is case study methodology? It is unique given one characteristic: case studies draw from more than one data source. In this post find definitions and a collection of multidisciplinary examples.

Find discussion of case studies and published examples.

Istanbul as a regional computational social science hub

Experiments and quantitative research.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

What is a Case Study? Definition & Examples

By Jim Frost Leave a Comment

Case Study Definition

A case study is an in-depth investigation of a single person, group, event, or community. This research method involves intensively analyzing a subject to understand its complexity and context. The richness of a case study comes from its ability to capture detailed, qualitative data that can offer insights into a process or subject matter that other research methods might miss.

A case study strives for a holistic understanding of events or situations by examining all relevant variables. They are ideal for exploring ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions in contexts where the researcher has limited control over events in real-life settings. Unlike narrowly focused experiments, these projects seek a comprehensive understanding of events or situations.

In a case study, researchers gather data through various methods such as participant observation, interviews, tests, record examinations, and writing samples. Unlike statistically-based studies that seek only quantifiable data, a case study attempts to uncover new variables and pose questions for subsequent research.

A case study is particularly beneficial when your research:

- Requires a deep, contextual understanding of a specific case.

- Needs to explore or generate hypotheses rather than test them.

- Focuses on a contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context.

Learn more about Other Types of Experimental Design .

Case Study Examples

Various fields utilize case studies, including the following:

- Social sciences : For understanding complex social phenomena.

- Business : For analyzing corporate strategies and business decisions.

- Healthcare : For detailed patient studies and medical research.

- Education : For understanding educational methods and policies.

- Law : For in-depth analysis of legal cases.

For example, consider a case study in a business setting where a startup struggles to scale. Researchers might examine the startup’s strategies, market conditions, management decisions, and competition. Interviews with the CEO, employees, and customers, alongside an analysis of financial data, could offer insights into the challenges and potential solutions for the startup. This research could serve as a valuable lesson for other emerging businesses.

See below for other examples.

| What impact does urban green space have on mental health in high-density cities? | Assess a green space development in Tokyo and its effects on resident mental health. |

| How do small businesses adapt to rapid technological changes? | Examine a small business in Silicon Valley adapting to new tech trends. |

| What strategies are effective in reducing plastic waste in coastal cities? | Study plastic waste management initiatives in Barcelona. |

| How do educational approaches differ in addressing diverse learning needs? | Investigate a specialized school’s approach to inclusive education in Sweden. |

| How does community involvement influence the success of public health initiatives? | Evaluate a community-led health program in rural India. |

| What are the challenges and successes of renewable energy adoption in developing countries? | Assess solar power implementation in a Kenyan village. |

Types of Case Studies

Several standard types of case studies exist that vary based on the objectives and specific research needs.

Illustrative Case Study : Descriptive in nature, these studies use one or two instances to depict a situation, helping to familiarize the unfamiliar and establish a common understanding of the topic.

Exploratory Case Study : Conducted as precursors to large-scale investigations, they assist in raising relevant questions, choosing measurement types, and identifying hypotheses to test.

Cumulative Case Study : These studies compile information from various sources over time to enhance generalization without the need for costly, repetitive new studies.

Critical Instance Case Study : Focused on specific sites, they either explore unique situations with limited generalizability or challenge broad assertions, to identify potential cause-and-effect issues.