- Connelly Library

Qualitative and Quantitative Research

What is "empirical research".

- empirical research

- Locating Articles in Cinahl and PsycInfo

- Locating Articles in PubMed

- Getting the Articles

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Locating Articles in Cinahl and PsycInfo >>

© Copyright La Salle University. All rights reserved.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Empirical Research: Definition, Methods, Types and Examples

Content Index

Empirical research: Definition

Empirical research: origin, quantitative research methods, qualitative research methods, steps for conducting empirical research, empirical research methodology cycle, advantages of empirical research, disadvantages of empirical research, why is there a need for empirical research.

Empirical research is defined as any research where conclusions of the study is strictly drawn from concretely empirical evidence, and therefore “verifiable” evidence.

This empirical evidence can be gathered using quantitative market research and qualitative market research methods.

For example: A research is being conducted to find out if listening to happy music in the workplace while working may promote creativity? An experiment is conducted by using a music website survey on a set of audience who are exposed to happy music and another set who are not listening to music at all, and the subjects are then observed. The results derived from such a research will give empirical evidence if it does promote creativity or not.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

You must have heard the quote” I will not believe it unless I see it”. This came from the ancient empiricists, a fundamental understanding that powered the emergence of medieval science during the renaissance period and laid the foundation of modern science, as we know it today. The word itself has its roots in greek. It is derived from the greek word empeirikos which means “experienced”.

In today’s world, the word empirical refers to collection of data using evidence that is collected through observation or experience or by using calibrated scientific instruments. All of the above origins have one thing in common which is dependence of observation and experiments to collect data and test them to come up with conclusions.

LEARN ABOUT: Causal Research

Types and methodologies of empirical research

Empirical research can be conducted and analysed using qualitative or quantitative methods.

- Quantitative research : Quantitative research methods are used to gather information through numerical data. It is used to quantify opinions, behaviors or other defined variables . These are predetermined and are in a more structured format. Some of the commonly used methods are survey, longitudinal studies, polls, etc

- Qualitative research: Qualitative research methods are used to gather non numerical data. It is used to find meanings, opinions, or the underlying reasons from its subjects. These methods are unstructured or semi structured. The sample size for such a research is usually small and it is a conversational type of method to provide more insight or in-depth information about the problem Some of the most popular forms of methods are focus groups, experiments, interviews, etc.

Data collected from these will need to be analysed. Empirical evidence can also be analysed either quantitatively and qualitatively. Using this, the researcher can answer empirical questions which have to be clearly defined and answerable with the findings he has got. The type of research design used will vary depending on the field in which it is going to be used. Many of them might choose to do a collective research involving quantitative and qualitative method to better answer questions which cannot be studied in a laboratory setting.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

Quantitative research methods aid in analyzing the empirical evidence gathered. By using these a researcher can find out if his hypothesis is supported or not.

- Survey research: Survey research generally involves a large audience to collect a large amount of data. This is a quantitative method having a predetermined set of closed questions which are pretty easy to answer. Because of the simplicity of such a method, high responses are achieved. It is one of the most commonly used methods for all kinds of research in today’s world.

Previously, surveys were taken face to face only with maybe a recorder. However, with advancement in technology and for ease, new mediums such as emails , or social media have emerged.

For example: Depletion of energy resources is a growing concern and hence there is a need for awareness about renewable energy. According to recent studies, fossil fuels still account for around 80% of energy consumption in the United States. Even though there is a rise in the use of green energy every year, there are certain parameters because of which the general population is still not opting for green energy. In order to understand why, a survey can be conducted to gather opinions of the general population about green energy and the factors that influence their choice of switching to renewable energy. Such a survey can help institutions or governing bodies to promote appropriate awareness and incentive schemes to push the use of greener energy.

Learn more: Renewable Energy Survey Template Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

- Experimental research: In experimental research , an experiment is set up and a hypothesis is tested by creating a situation in which one of the variable is manipulated. This is also used to check cause and effect. It is tested to see what happens to the independent variable if the other one is removed or altered. The process for such a method is usually proposing a hypothesis, experimenting on it, analyzing the findings and reporting the findings to understand if it supports the theory or not.

For example: A particular product company is trying to find what is the reason for them to not be able to capture the market. So the organisation makes changes in each one of the processes like manufacturing, marketing, sales and operations. Through the experiment they understand that sales training directly impacts the market coverage for their product. If the person is trained well, then the product will have better coverage.

- Correlational research: Correlational research is used to find relation between two set of variables . Regression analysis is generally used to predict outcomes of such a method. It can be positive, negative or neutral correlation.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

For example: Higher educated individuals will get higher paying jobs. This means higher education enables the individual to high paying job and less education will lead to lower paying jobs.

- Longitudinal study: Longitudinal study is used to understand the traits or behavior of a subject under observation after repeatedly testing the subject over a period of time. Data collected from such a method can be qualitative or quantitative in nature.

For example: A research to find out benefits of exercise. The target is asked to exercise everyday for a particular period of time and the results show higher endurance, stamina, and muscle growth. This supports the fact that exercise benefits an individual body.

- Cross sectional: Cross sectional study is an observational type of method, in which a set of audience is observed at a given point in time. In this type, the set of people are chosen in a fashion which depicts similarity in all the variables except the one which is being researched. This type does not enable the researcher to establish a cause and effect relationship as it is not observed for a continuous time period. It is majorly used by healthcare sector or the retail industry.

For example: A medical study to find the prevalence of under-nutrition disorders in kids of a given population. This will involve looking at a wide range of parameters like age, ethnicity, location, incomes and social backgrounds. If a significant number of kids coming from poor families show under-nutrition disorders, the researcher can further investigate into it. Usually a cross sectional study is followed by a longitudinal study to find out the exact reason.

- Causal-Comparative research : This method is based on comparison. It is mainly used to find out cause-effect relationship between two variables or even multiple variables.

For example: A researcher measured the productivity of employees in a company which gave breaks to the employees during work and compared that to the employees of the company which did not give breaks at all.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Some research questions need to be analysed qualitatively, as quantitative methods are not applicable there. In many cases, in-depth information is needed or a researcher may need to observe a target audience behavior, hence the results needed are in a descriptive analysis form. Qualitative research results will be descriptive rather than predictive. It enables the researcher to build or support theories for future potential quantitative research. In such a situation qualitative research methods are used to derive a conclusion to support the theory or hypothesis being studied.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

- Case study: Case study method is used to find more information through carefully analyzing existing cases. It is very often used for business research or to gather empirical evidence for investigation purpose. It is a method to investigate a problem within its real life context through existing cases. The researcher has to carefully analyse making sure the parameter and variables in the existing case are the same as to the case that is being investigated. Using the findings from the case study, conclusions can be drawn regarding the topic that is being studied.

For example: A report mentioning the solution provided by a company to its client. The challenges they faced during initiation and deployment, the findings of the case and solutions they offered for the problems. Such case studies are used by most companies as it forms an empirical evidence for the company to promote in order to get more business.

- Observational method: Observational method is a process to observe and gather data from its target. Since it is a qualitative method it is time consuming and very personal. It can be said that observational research method is a part of ethnographic research which is also used to gather empirical evidence. This is usually a qualitative form of research, however in some cases it can be quantitative as well depending on what is being studied.

For example: setting up a research to observe a particular animal in the rain-forests of amazon. Such a research usually take a lot of time as observation has to be done for a set amount of time to study patterns or behavior of the subject. Another example used widely nowadays is to observe people shopping in a mall to figure out buying behavior of consumers.

- One-on-one interview: Such a method is purely qualitative and one of the most widely used. The reason being it enables a researcher get precise meaningful data if the right questions are asked. It is a conversational method where in-depth data can be gathered depending on where the conversation leads.

For example: A one-on-one interview with the finance minister to gather data on financial policies of the country and its implications on the public.

- Focus groups: Focus groups are used when a researcher wants to find answers to why, what and how questions. A small group is generally chosen for such a method and it is not necessary to interact with the group in person. A moderator is generally needed in case the group is being addressed in person. This is widely used by product companies to collect data about their brands and the product.

For example: A mobile phone manufacturer wanting to have a feedback on the dimensions of one of their models which is yet to be launched. Such studies help the company meet the demand of the customer and position their model appropriately in the market.

- Text analysis: Text analysis method is a little new compared to the other types. Such a method is used to analyse social life by going through images or words used by the individual. In today’s world, with social media playing a major part of everyone’s life, such a method enables the research to follow the pattern that relates to his study.

For example: A lot of companies ask for feedback from the customer in detail mentioning how satisfied are they with their customer support team. Such data enables the researcher to take appropriate decisions to make their support team better.

Sometimes a combination of the methods is also needed for some questions that cannot be answered using only one type of method especially when a researcher needs to gain a complete understanding of complex subject matter.

We recently published a blog that talks about examples of qualitative data in education ; why don’t you check it out for more ideas?

Since empirical research is based on observation and capturing experiences, it is important to plan the steps to conduct the experiment and how to analyse it. This will enable the researcher to resolve problems or obstacles which can occur during the experiment.

Step #1: Define the purpose of the research

This is the step where the researcher has to answer questions like what exactly do I want to find out? What is the problem statement? Are there any issues in terms of the availability of knowledge, data, time or resources. Will this research be more beneficial than what it will cost.

Before going ahead, a researcher has to clearly define his purpose for the research and set up a plan to carry out further tasks.

Step #2 : Supporting theories and relevant literature

The researcher needs to find out if there are theories which can be linked to his research problem . He has to figure out if any theory can help him support his findings. All kind of relevant literature will help the researcher to find if there are others who have researched this before, or what are the problems faced during this research. The researcher will also have to set up assumptions and also find out if there is any history regarding his research problem

Step #3: Creation of Hypothesis and measurement

Before beginning the actual research he needs to provide himself a working hypothesis or guess what will be the probable result. Researcher has to set up variables, decide the environment for the research and find out how can he relate between the variables.

Researcher will also need to define the units of measurements, tolerable degree for errors, and find out if the measurement chosen will be acceptable by others.

Step #4: Methodology, research design and data collection

In this step, the researcher has to define a strategy for conducting his research. He has to set up experiments to collect data which will enable him to propose the hypothesis. The researcher will decide whether he will need experimental or non experimental method for conducting the research. The type of research design will vary depending on the field in which the research is being conducted. Last but not the least, the researcher will have to find out parameters that will affect the validity of the research design. Data collection will need to be done by choosing appropriate samples depending on the research question. To carry out the research, he can use one of the many sampling techniques. Once data collection is complete, researcher will have empirical data which needs to be analysed.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Step #5: Data Analysis and result

Data analysis can be done in two ways, qualitatively and quantitatively. Researcher will need to find out what qualitative method or quantitative method will be needed or will he need a combination of both. Depending on the unit of analysis of his data, he will know if his hypothesis is supported or rejected. Analyzing this data is the most important part to support his hypothesis.

Step #6: Conclusion

A report will need to be made with the findings of the research. The researcher can give the theories and literature that support his research. He can make suggestions or recommendations for further research on his topic.

A.D. de Groot, a famous dutch psychologist and a chess expert conducted some of the most notable experiments using chess in the 1940’s. During his study, he came up with a cycle which is consistent and now widely used to conduct empirical research. It consists of 5 phases with each phase being as important as the next one. The empirical cycle captures the process of coming up with hypothesis about how certain subjects work or behave and then testing these hypothesis against empirical data in a systematic and rigorous approach. It can be said that it characterizes the deductive approach to science. Following is the empirical cycle.

- Observation: At this phase an idea is sparked for proposing a hypothesis. During this phase empirical data is gathered using observation. For example: a particular species of flower bloom in a different color only during a specific season.

- Induction: Inductive reasoning is then carried out to form a general conclusion from the data gathered through observation. For example: As stated above it is observed that the species of flower blooms in a different color during a specific season. A researcher may ask a question “does the temperature in the season cause the color change in the flower?” He can assume that is the case, however it is a mere conjecture and hence an experiment needs to be set up to support this hypothesis. So he tags a few set of flowers kept at a different temperature and observes if they still change the color?

- Deduction: This phase helps the researcher to deduce a conclusion out of his experiment. This has to be based on logic and rationality to come up with specific unbiased results.For example: In the experiment, if the tagged flowers in a different temperature environment do not change the color then it can be concluded that temperature plays a role in changing the color of the bloom.

- Testing: This phase involves the researcher to return to empirical methods to put his hypothesis to the test. The researcher now needs to make sense of his data and hence needs to use statistical analysis plans to determine the temperature and bloom color relationship. If the researcher finds out that most flowers bloom a different color when exposed to the certain temperature and the others do not when the temperature is different, he has found support to his hypothesis. Please note this not proof but just a support to his hypothesis.

- Evaluation: This phase is generally forgotten by most but is an important one to keep gaining knowledge. During this phase the researcher puts forth the data he has collected, the support argument and his conclusion. The researcher also states the limitations for the experiment and his hypothesis and suggests tips for others to pick it up and continue a more in-depth research for others in the future. LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

There is a reason why empirical research is one of the most widely used method. There are a few advantages associated with it. Following are a few of them.

- It is used to authenticate traditional research through various experiments and observations.

- This research methodology makes the research being conducted more competent and authentic.

- It enables a researcher understand the dynamic changes that can happen and change his strategy accordingly.

- The level of control in such a research is high so the researcher can control multiple variables.

- It plays a vital role in increasing internal validity .

Even though empirical research makes the research more competent and authentic, it does have a few disadvantages. Following are a few of them.

- Such a research needs patience as it can be very time consuming. The researcher has to collect data from multiple sources and the parameters involved are quite a few, which will lead to a time consuming research.

- Most of the time, a researcher will need to conduct research at different locations or in different environments, this can lead to an expensive affair.

- There are a few rules in which experiments can be performed and hence permissions are needed. Many a times, it is very difficult to get certain permissions to carry out different methods of this research.

- Collection of data can be a problem sometimes, as it has to be collected from a variety of sources through different methods.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

Empirical research is important in today’s world because most people believe in something only that they can see, hear or experience. It is used to validate multiple hypothesis and increase human knowledge and continue doing it to keep advancing in various fields.

For example: Pharmaceutical companies use empirical research to try out a specific drug on controlled groups or random groups to study the effect and cause. This way, they prove certain theories they had proposed for the specific drug. Such research is very important as sometimes it can lead to finding a cure for a disease that has existed for many years. It is useful in science and many other fields like history, social sciences, business, etc.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

With the advancement in today’s world, empirical research has become critical and a norm in many fields to support their hypothesis and gain more knowledge. The methods mentioned above are very useful for carrying out such research. However, a number of new methods will keep coming up as the nature of new investigative questions keeps getting unique or changing.

Create a single source of real data with a built-for-insights platform. Store past data, add nuggets of insights, and import research data from various sources into a CRM for insights. Build on ever-growing research with a real-time dashboard in a unified research management platform to turn insights into knowledge.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Feedback Loop: What It Is, Types & How It Works?

Jun 21, 2024

QuestionPro Thrive: A Space to Visualize & Share the Future of Technology

Jun 18, 2024

Relationship NPS Fails to Understand Customer Experiences — Tuesday CX

CX Platform: Top 13 CX Platforms to Drive Customer Success

Jun 17, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Empirical evidence: A definition

Empirical evidence is information that is acquired by observation or experimentation.

The scientific method

Types of empirical research, identifying empirical evidence, empirical law vs. scientific law, empirical, anecdotal and logical evidence, additional resources and reading, bibliography.

Empirical evidence is information acquired by observation or experimentation. Scientists record and analyze this data. The process is a central part of the scientific method , leading to the proving or disproving of a hypothesis and our better understanding of the world as a result.

Empirical evidence might be obtained through experiments that seek to provide a measurable or observable reaction, trials that repeat an experiment to test its efficacy (such as a drug trial, for instance) or other forms of data gathering against which a hypothesis can be tested and reliably measured.

"If a statement is about something that is itself observable, then the empirical testing can be direct. We just have a look to see if it is true. For example, the statement, 'The litmus paper is pink', is subject to direct empirical testing," wrote Peter Kosso in " A Summary of Scientific Method " (Springer, 2011).

"Science is most interesting and most useful to us when it is describing the unobservable things like atoms , germs , black holes , gravity , the process of evolution as it happened in the past, and so on," wrote Kosso. Scientific theories , meaning theories about nature that are unobservable, cannot be proven by direct empirical testing, but they can be tested indirectly, according to Kosso. "The nature of this indirect evidence, and the logical relation between evidence and theory, are the crux of scientific method," wrote Kosso.

The scientific method begins with scientists forming questions, or hypotheses , and then acquiring the knowledge through observations and experiments to either support or disprove a specific theory. "Empirical" means "based on observation or experience," according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary . Empirical research is the process of finding empirical evidence. Empirical data is the information that comes from the research.

Before any pieces of empirical data are collected, scientists carefully design their research methods to ensure the accuracy, quality and integrity of the data. If there are flaws in the way that empirical data is collected, the research will not be considered valid.

The scientific method often involves lab experiments that are repeated over and over, and these experiments result in quantitative data in the form of numbers and statistics. However, that is not the only process used for gathering information to support or refute a theory.

This methodology mostly applies to the natural sciences. "The role of empirical experimentation and observation is negligible in mathematics compared to natural sciences such as psychology, biology or physics," wrote Mark Chang, an adjunct professor at Boston University, in " Principles of Scientific Methods " (Chapman and Hall, 2017).

"Empirical evidence includes measurements or data collected through direct observation or experimentation," said Jaime Tanner, a professor of biology at Marlboro College in Vermont. There are two research methods used to gather empirical measurements and data: qualitative and quantitative.

Qualitative research, often used in the social sciences, examines the reasons behind human behavior, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) . It involves data that can be found using the human senses . This type of research is often done in the beginning of an experiment. "When combined with quantitative measures, qualitative study can give a better understanding of health related issues," wrote Dr. Sanjay Kalra for NCBI.

Quantitative research involves methods that are used to collect numerical data and analyze it using statistical methods, ."Quantitative research methods emphasize objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques," according to the LeTourneau University . This type of research is often used at the end of an experiment to refine and test the previous research.

Identifying empirical evidence in another researcher's experiments can sometimes be difficult. According to the Pennsylvania State University Libraries , there are some things one can look for when determining if evidence is empirical:

- Can the experiment be recreated and tested?

- Does the experiment have a statement about the methodology, tools and controls used?

- Is there a definition of the group or phenomena being studied?

The objective of science is that all empirical data that has been gathered through observation, experience and experimentation is without bias. The strength of any scientific research depends on the ability to gather and analyze empirical data in the most unbiased and controlled fashion possible.

However, in the 1960s, scientific historian and philosopher Thomas Kuhn promoted the idea that scientists can be influenced by prior beliefs and experiences, according to the Center for the Study of Language and Information .

— Amazing Black scientists

— Marie Curie: Facts and biography

— What is multiverse theory?

"Missing observations or incomplete data can also cause bias in data analysis, especially when the missing mechanism is not random," wrote Chang.

Because scientists are human and prone to error, empirical data is often gathered by multiple scientists who independently replicate experiments. This also guards against scientists who unconsciously, or in rare cases consciously, veer from the prescribed research parameters, which could skew the results.

The recording of empirical data is also crucial to the scientific method, as science can only be advanced if data is shared and analyzed. Peer review of empirical data is essential to protect against bad science, according to the University of California .

Empirical laws and scientific laws are often the same thing. "Laws are descriptions — often mathematical descriptions — of natural phenomenon," Peter Coppinger, associate professor of biology and biomedical engineering at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, told Live Science.

Empirical laws are scientific laws that can be proven or disproved using observations or experiments, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary . So, as long as a scientific law can be tested using experiments or observations, it is considered an empirical law.

Empirical, anecdotal and logical evidence should not be confused. They are separate types of evidence that can be used to try to prove or disprove and idea or claim.

Logical evidence is used proven or disprove an idea using logic. Deductive reasoning may be used to come to a conclusion to provide logical evidence. For example, "All men are mortal. Harold is a man. Therefore, Harold is mortal."

Anecdotal evidence consists of stories that have been experienced by a person that are told to prove or disprove a point. For example, many people have told stories about their alien abductions to prove that aliens exist. Often, a person's anecdotal evidence cannot be proven or disproven.

There are some things in nature that science is still working to build evidence for, such as the hunt to explain consciousness .

Meanwhile, in other scientific fields, efforts are still being made to improve research methods, such as the plan by some psychologists to fix the science of psychology .

" A Summary of Scientific Method " by Peter Kosso (Springer, 2011)

"Empirical" Merriam-Webster Dictionary

" Principles of Scientific Methods " by Mark Chang (Chapman and Hall, 2017)

"Qualitative research" by Dr. Sanjay Kalra National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

"Quantitative Research and Analysis: Quantitative Methods Overview" LeTourneau University

"Empirical Research in the Social Sciences and Education" Pennsylvania State University Libraries

"Thomas Kuhn" Center for the Study of Language and Information

"Misconceptions about science" University of California

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

30,000 years of history reveals that hard times boost human societies' resilience

'We're meeting people where they are': Graphic novels can help boost diversity in STEM, says MIT's Ritu Raman

Gates of Hell: Turkmenistan's methane-fueled fire pit that has been burning since 1971

Most Popular

- 2 Strawberry Moon 2024: See summer's first full moon rise a day after solstice

- 3 Y chromosome is evolving faster than the X, primate study reveals

- 4 Ming dynasty shipwrecks hide a treasure trove of artifacts in the South China Sea, excavation reveals

- 5 Astronomers discover the 1st-ever merging galaxy cores at cosmic dawn

- 2 '1st of its kind': NASA spots unusually light-colored boulder on Mars that may reveal clues of the planet's past

- 3 Long-lost Assyrian military camp devastated by 'the angel of the Lord' finally found, scientist claims

- 4 Giant river system that existed 40 million years ago discovered deep below Antarctic ice

- University of Memphis Libraries

- Research Guides

Empirical Research: Defining, Identifying, & Finding

Defining empirical research, what is empirical research, quantitative or qualitative.

- Introduction

- Database Tools

- Search Terms

- Image Descriptions

Calfee & Chambliss (2005) (UofM login required) describe empirical research as a "systematic approach for answering certain types of questions." Those questions are answered "[t]hrough the collection of evidence under carefully defined and replicable conditions" (p. 43).

The evidence collected during empirical research is often referred to as "data."

Characteristics of Empirical Research

Emerald Publishing's guide to conducting empirical research identifies a number of common elements to empirical research:

- A research question , which will determine research objectives.

- A particular and planned design for the research, which will depend on the question and which will find ways of answering it with appropriate use of resources.

- The gathering of primary data , which is then analysed.

- A particular methodology for collecting and analysing the data, such as an experiment or survey.

- The limitation of the data to a particular group, area or time scale, known as a sample [emphasis added]: for example, a specific number of employees of a particular company type, or all users of a library over a given time scale. The sample should be somehow representative of a wider population.

- The ability to recreate the study and test the results. This is known as reliability .

- The ability to generalize from the findings to a larger sample and to other situations.

If you see these elements in a research article, you can feel confident that you have found empirical research. Emerald's guide goes into more detail on each element.

Empirical research methodologies can be described as quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both (usually called mixed-methods).

Ruane (2016) (UofM login required) gets at the basic differences in approach between quantitative and qualitative research:

- Quantitative research -- an approach to documenting reality that relies heavily on numbers both for the measurement of variables and for data analysis (p. 33).

- Qualitative research -- an approach to documenting reality that relies on words and images as the primary data source (p. 33).

Both quantitative and qualitative methods are empirical . If you can recognize that a research study is quantitative or qualitative study, then you have also recognized that it is empirical study.

Below are information on the characteristics of quantitative and qualitative research. This video from Scribbr also offers a good overall introduction to the two approaches to research methodology:

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Researchers test hypotheses, or theories, based in assumptions about causality, i.e. we expect variable X to cause variable Y. Variables have to be controlled as much as possible to ensure validity. The results explain the relationship between the variables. Measures are based in pre-defined instruments.

Examples: experimental or quasi-experimental design, pretest & post-test, survey or questionnaire with closed-ended questions. Studies that identify factors that influence an outcomes, the utility of an intervention, or understanding predictors of outcomes.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Researchers explore “meaning individuals or groups ascribe to social or human problems (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p3).” Questions and procedures emerge rather than being prescribed. Complexity, nuance, and individual meaning are valued. Research is both inductive and deductive. Data sources are multiple and varied, i.e. interviews, observations, documents, photographs, etc. The researcher is a key instrument and must be reflective of their background, culture, and experiences as influential of the research.

Examples: open question interviews and surveys, focus groups, case studies, grounded theory, ethnography, discourse analysis, narrative, phenomenology, participatory action research.

Calfee, R. C. & Chambliss, M. (2005). The design of empirical research. In J. Flood, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, & J. Jensen (Eds.), Methods of research on teaching the English language arts: The methodology chapters from the handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (pp. 43-78). Routledge. http://ezproxy.memphis.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=125955&site=eds-live&scope=site .

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

How to... conduct empirical research . (n.d.). Emerald Publishing. https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/how-to/research-methods/conduct-empirical-research .

Scribbr. (2019). Quantitative vs. qualitative: The differences explained [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a-XtVF7Bofg .

Ruane, J. M. (2016). Introducing social research methods : Essentials for getting the edge . Wiley-Blackwell. http://ezproxy.memphis.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1107215&site=eds-live&scope=site .

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Identifying Empirical Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 11:25 AM

- URL: https://libguides.memphis.edu/empirical-research

Jump to navigation

Cochrane Training

Chapter 21: qualitative evidence.

Jane Noyes, Andrew Booth, Margaret Cargo, Kate Flemming, Angela Harden, Janet Harris, Ruth Garside, Karin Hannes, Tomás Pantoja, James Thomas

Key Points:

- A qualitative evidence synthesis (commonly referred to as QES) can add value by providing decision makers with additional evidence to improve understanding of intervention complexity, contextual variations, implementation, and stakeholder preferences and experiences.

- A qualitative evidence synthesis can be undertaken and integrated with a corresponding intervention review; or

- Undertaken using a mixed-method design that integrates a qualitative evidence synthesis with an intervention review in a single protocol.

- Methods for qualitative evidence synthesis are complex and continue to develop. Authors should always consult current methods guidance at methods.cochrane.org/qi .

This chapter should be cited as: Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, Flemming K, Harden A, Harris J, Garside R, Hannes K, Pantoja T, Thomas J. Chapter 21: Qualitative evidence. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane, 2023. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook .

21.1 Introduction

The potential contribution of qualitative evidence to decision making is well-established (Glenton et al 2016, Booth 2017, Carroll 2017). A synthesis of qualitative evidence can inform understanding of how interventions work by:

- increasing understanding of a phenomenon of interest (e.g. women’s conceptualization of what good antenatal care looks like);

- identifying associations between the broader environment within which people live and the interventions that are implemented;

- increasing understanding of the values and attitudes toward, and experiences of, health conditions and interventions by those who implement or receive them; and

- providing a detailed understanding of the complexity of interventions and implementation, and their impacts and effects on different subgroups of people and the influence of individual and contextual characteristics within different contexts.

The aim of this chapter is to provide authors (who already have experience of undertaking qualitative research and qualitative evidence synthesis) with additional guidance on undertaking a qualitative evidence synthesis that is subsequently integrated with an intervention review. This chapter draws upon guidance presented in a series of six papers published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology (Cargo et al 2018, Flemming et al 2018, Harden et al 2018, Harris et al 2018, Noyes et al 2018a, Noyes et al 2018b) and from a further World Health Organization series of papers published in BMJ Global Health, which extend guidance to qualitative evidence syntheses conducted within a complex intervention and health systems and decision making context (Booth et al 2019a, Booth et al 2019b, Flemming et al 2019, Noyes et al 2019, Petticrew et al 2019).The qualitative evidence synthesis and integration methods described in this chapter supplement Chapter 17 on methods for addressing intervention complexity. Authors undertaking qualitative evidence syntheses should consult these papers and chapters for more detailed guidance.

21.2 Designs for synthesizing and integrating qualitative evidence with intervention reviews

There are two main designs for synthesizing qualitative evidence with evidence of the effects of interventions:

- Sequential reviews: where one or more existing intervention review(s) has been published on a similar topic, it is possible to do a sequential qualitative evidence synthesis and then integrate its findings with those of the intervention review to create a mixed-method review. For example, Lewin and colleagues (Lewin et al (2010) and Glenton and colleagues (Glenton et al (2013) undertook sequential reviews of lay health worker programmes using separate protocols and then integrated the findings.

- Convergent mixed-methods review: where no pre-existing intervention review exists, it is possible to do a full convergent ‘mixed-methods’ review where the trials and qualitative evidence are synthesized separately, creating opportunities for them to ‘speak’ to each other during development, and then integrated within a third synthesis. For example, Hurley and colleagues (Hurley et al (2018) undertook an intervention review and a qualitative evidence synthesis following a single protocol.

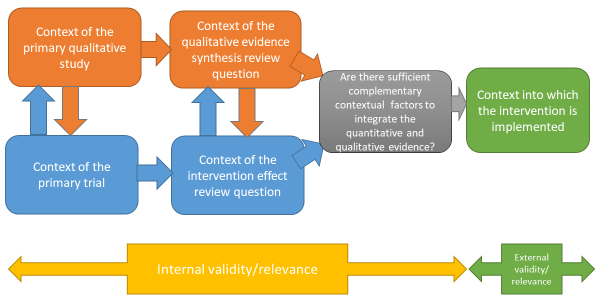

It is increasingly common for sequential and convergent reviews to be conducted by some or all of the same authors; if not, it is critical that authors working on the qualitative evidence synthesis and intervention review work closely together to identify and create sufficient points of integration to enable a third synthesis that integrates the two reviews, or the conduct of a mixed-method review (Noyes et al 2018a) (see Figure 21.2.a ). This consideration also applies where an intervention review has already been published and there is no prior relationship with the qualitative evidence synthesis authors. We recommend that at least one joint author works across both reviews to facilitate development of the qualitative evidence synthesis protocol, conduct of the synthesis, and subsequent integration of the qualitative evidence synthesis with the intervention review within a mixed-methods review.

Figure 21.2.a Considering context and points of contextual integration with the intervention review or within a mixed-method review

21.3 Defining qualitative evidence and studies

We use the term ‘qualitative evidence synthesis’ to acknowledge that other types of qualitative evidence (or data) can potentially enrich a synthesis, such as narrative data derived from qualitative components of mixed-method studies or free text from questionnaire surveys. We would not, however, consider a questionnaire survey to be a qualitative study and qualitative data from questionnaires should not usually be privileged over relevant evidence from qualitative studies. When thinking about qualitative evidence, specific terminology is used to describe the level of conceptual and contextual detail. Qualitative evidence that includes higher or lower levels of conceptual detail is described as ‘rich’ or ‘poor’. Associated terms ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ are best used to refer to higher or lower levels of contextual detail. Review authors can potentially develop a stronger synthesis using rich and thick qualitative evidence but, in reality, they will identify diverse conceptually rich and poor and contextually thick and thin studies. Developing a clear picture of the type and conceptual richness of available qualitative evidence strongly influences the choice of methodology and subsequent methods. We recommend that authors undertake scoping searches to determining the type and richness of available qualitative evidence before selecting their methodology and methods.

A qualitative study is a research study that uses a qualitative method of data collection and analysis. Review authors should include the studies that enable them to answer their review question. When selecting qualitative studies in a review about intervention effects, two types of qualitative study are available: those that collect data from the same participants as the included trials, known as ‘trial siblings’; and those that address relevant issues about the intervention, but as separate items of research – not connected to any included trials. Both can provide useful information, with trial sibling studies obviously closer in terms of their precise contexts to the included trials (Moore et al 2015), and non-sibling studies possibly contributing perspectives not present in the trials (Noyes et al 2016b).

21.4 Planning a qualitative evidence synthesis linked to an intervention review

The Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group (QIMG) website provides links to practical guidance and key steps for authors who are considering a qualitative evidence synthesis ( methods.cochrane.org/qi ). The RETREAT framework outlines seven key considerations that review authors should systematically work through when planning a review (Booth et al 2016, Booth et al 2018) ( Box 21.4.a ). Flemming and colleagues (Flemming et al (2019) further explain how to factor in such considerations when undertaking a qualitative evidence synthesis within a complex intervention and decision making context when complexity is an important consideration.

Box 21.4.a RETREAT considerations when selecting an appropriate method for qualitative synthesis

| first, consider the complexity of the review question. Which elements contribute most to complexity (e.g. the condition, the intervention or the context)? Which elements should be prioritized as the focal point for attention? (Squires et al 2013, Kelly et al 2017). consider the philosophical foundations of the primary studies. Would it be appropriate to favour a method such as thematic synthesis that it is less reliant on epistemological considerations? (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009). – consider what type of qualitative evidence synthesis will be feasible and manageable within the time frame available (Booth et al 2016). – consider whether the ambition of the review matches the available resources. Will the extent of the scope and the sampling approach of the review need to be limited? (Benoot et al 2016, Booth et al 2016). consider access to expertise, both within the review team and among a wider group of advisors. Does the available expertise match the qualitative evidence synthesis approach chosen? (Booth et al 2016). consider the intended audience and purpose of the review. Does the approach to question formulation, the scope of the review and the intended outputs meet their needs? (Booth et al 2016). consider the type of data present in typical studies for inclusion. To what extent are candidate studies conceptually rich and contextually thick in their detail? |

21.5 Question development

The review question is critical to development of the qualitative evidence synthesis (Harris et al 2018). Question development affords a key point for integration with the intervention review. Complementary guidance supports novel thinking about question development, application of question development frameworks and the types of questions to be addressed by a synthesis of qualitative evidence (Cargo et al 2018, Harris et al 2018, Noyes et al 2018a, Booth et al 2019b, Flemming et al 2019).

Research questions for quantitative reviews are often mapped using structures such as PICO. Some qualitative reviews adopt this structure, or use an adapted variation of such a structure (e.g. SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention or Phenomenon of Interest, Comparison, Evaluation) or SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type); (Cooke et al 2012). Booth and colleagues (Booth et al (2019b) propose an extended question framework (PerSPecTIF) to describe both wider context and immediate setting that is particularly suited to qualitative evidence synthesis and complex intervention reviews (see Table 21.5.a ).

Detailed attention to the question and specification of context at an early stage is critical to many aspects of qualitative synthesis (see Petticrew et al (2019) and Booth et al (2019a) for a more detailed discussion). By specifying the context a review team is able to identify opportunities for integration with the intervention review, or opportunities for maximizing use and interpretation of evidence as a mixed-method review progresses (see Figure 21.2.a ), and informs both the interpretation of the observed effects and assessment of the strength of the evidence available in addressing the review question (Noyes et al 2019). Subsequent application of GRADE CERQual (Lewin et al 2015, Lewin et al 2018), an approach to assess the confidence in synthesized qualitative findings, requires further specification of context in the review question.

Table 21.5.a PerSPecTIF Question formulation framework for qualitative evidence syntheses (Booth et al (2019b). Reproduced with permission of BMJ Publishing Group

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Perspective | Setting | Phenomenon of interest/ Problem | Environment | Comparison (optional) | Time/ Timing | Findings |

| From the perspective of a pregnant woman | In the setting of rural communities | How does facility-based care | Within an environment of poor transport infrastructure and distantly located facilities | Compare with traditional birth attendants at home | Up to and including delivery | In relation to the woman’s perceptions and experiences? |

21.6 Questions exploring intervention implementation

Additional guidance is available on formulation of questions to understand and assess intervention implementation (Cargo et al 2018). A strong understanding of how an intervention is thought to work, and how it should be implemented in practice, will enable a critical consideration of whether any observed lack of effect might be due to a poorly conceptualized intervention (i.e. theory failure) or a poor intervention implementation (i.e. implementation failure). Heterogeneity needs to be considered for both the underlying theory and the ways in which the intervention was implemented. An a priori scoping review (Levac et al 2010), concept analysis (Walker and Avant 2005), critical review (Grant and Booth 2009) or textual narrative synthesis (Barnett-Page and Thomas 2009) can be undertaken to classify interventions and/or to identify the programme theory, logic model or implementation measures and processes. The intervention Complexity Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews iCAT_SR (Lewin et al 2017) may be helpful in classifying complexity in interventions and developing associated questions.

An existing intervention model or framework may be used within a new topic or context. The ‘best-fit framework’ approach to synthesis (Carroll et al 2013) can be used to establish the degree to which the source context (from where the framework was derived) resembles the new target context (see Figure 21.2.a ). In the absence of an explicit programme theory and detail of how implementation relates to outcomes, an a priori realist review, meta-ethnography or meta-interpretive review can be undertaken (Booth et al 2016). For example, Downe and colleagues (Downe et al (2016) undertook an initial meta-ethnography review to develop an understanding of the outcomes of importance to women receiving antenatal care.

However, these additional activities are very resource-intensive and are only recommended when the review team has sufficient resources to supplement the planned qualitative evidence syntheses with an additional explanatory review. Where resources are less plentiful a review team could engage with key stakeholders to articulate and develop programme theory (Kelly et al 2017, De Buck et al 2018).

21.6.1 Using logic models and theories to support question development

Review authors can develop a more comprehensive representation of question features through use of logic models, programme theories, theories of change, templates and pathways (Anderson et al 2011, Kneale et al 2015, Noyes et al 2016a) (see also Chapter 17, Section 17.2.1 and Chapter 2, Section 2.5.1 ). These different forms of social theory can be used to visualize and map the research question, its context, components, influential factors and possible outcomes (Noyes et al 2016a, Rehfuess et al 2018).

21.6.2 Stakeholder engagement

Finally, review authors need to engage stakeholders, including consumers affected by the health issue and interventions, or likely users of the review from clinical or policy contexts. From the preparatory stage, this consultation can ensure that the review scope and question is appropriate and resulting products address implementation concerns of decision makers (Kelly et al 2017, Harris et al 2018).

21.7 Searching for qualitative evidence

In comparison with identification of quantitative studies (see also Chapter 4 ), procedures for retrieval of qualitative research remain relatively under-developed. Particular challenges in retrieval are associated with non-informative titles and abstracts, diffuse terminology, poor indexing and the overwhelming prevalence of quantitative studies within data sources (Booth et al 2016).

Principal considerations when planning a search for qualitative studies, and the evidence that underpins them, have been characterized using a 7S framework from Sampling and Sources through Structured questions, Search procedures, Strategies and filters and Supplementary strategies to Standards for Reporting (Booth et al 2016).

A key decision, aligned to the purpose of the qualitative evidence synthesis is whether to use the comprehensive, exhaustive approaches that characterize quantitative searches or whether to use purposive sampling that is more sensitive to the qualitative paradigm (Suri 2011). The latter, which is used when the intent is to generate an interpretative understanding, for example, when generating theory, draws upon a versatile toolkit that includes theoretical sampling, maximum variation sampling and intensity sampling. Sources of qualitative evidence are more likely to include book chapters, theses and grey literature reports than standard quantitative study reports, and so a search strategy should place extra emphasis on these sources. Local databases may be particularly valuable given the criticality of context (Stansfield et al 2012).

Another key decision is whether to use study filters or simply to conduct a topic-based search where qualitative studies are identified at the study selection stage. Search filters for qualitative studies lack the specificity of their quantitative counterparts. Nevertheless, filters may facilitate efficient retrieval by study type (e.g. qualitative (Rogers et al 2018) or mixed methods (El Sherif et al 2016) or by perspective (e.g. patient preferences (Selva et al 2017)) particularly where the quantitative literature is overwhelmingly large and thus increases the number needed to retrieve. Poor indexing of qualitative studies makes citation searching (forward and backward) and the Related Articles features of electronic databases particularly useful (Cooper et al 2017). Further guidance on searching for qualitative evidence is available (Booth et al 2016, Noyes et al 2018a). The CLUSTER method has been proposed as a specific named method for tracking down associated or sibling reports (Booth et al 2013). The BeHEMoTh approach has been developed for identifying explicit use of theory (Booth and Carroll 2015).

21.7.1 Searching for process evaluations and implementation evidence

Four potential approaches are available to identify process evaluations.

- Identify studies at the point of study selection rather than through tailored search strategies. This involves conducting a sensitive topic search without any study design filter (Harden et al 1999), and identifying all study designs of interest during the screening process. This approach can be feasible when a review question involves multiple publication types (e.g. randomized trial, qualitative research and economic evaluations), which then do not require separate searches.

- Restrict included process evaluations to those conducted within randomized trials, which can be identified using standard search filters (see Chapter 4, Section 4.4.7 ). This method relies on reports of process evaluations also describing the surrounding randomized trial in enough detail to be identified by the search filter.

- Use unevaluated filter terms (such as ‘process evaluation’, ‘program(me) evaluation’, ‘feasibility study’, ‘implementation’ or ‘proof of concept’ etc) to retrieve process evaluations or implementation data. Approaches using strings of terms associated with the study type or purpose are considered experimental. There is a need to develop and test such filters. It is likely that such filters may be derived from the study type (process evaluation), the data type (process data) or the application (implementation) (Robbins et al 2011).

- Minimize reliance on topic-based searching and rely on citations-based approaches to identify linked reports, published or unpublished, of a particular study (Booth et al 2013) which may provide implementation or process data (Bonell et al 2013).

More detailed guidance is provided by Cargo and colleagues (Cargo et al (2018).

21.8 Assessing methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative studies

Assessment of the methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative research remains contested within the primary qualitative research community (Garside 2014). However, within systematic reviews and evidence syntheses it is considered essential, even when studies are not to be excluded on the basis of quality (Carroll et al 2013). One review found almost 100 appraisal tools for assessing primary qualitative studies (Munthe-Kaas et al 2019). Limitations included a focus on reporting rather than conduct and the presence of items that are separate from, or tangential to, consideration of study quality (e.g. ethical approval).

Authors should distinguish between assessment of study quality and assessment of risk of bias by focusing on assessment of methodological strengths and limitations as a marker of study rigour (what we term a ‘risk to rigour’ approach (Noyes et al 2019)). In the absence of a definitive risk to rigour tool, we recommend that review authors select from published, commonly used and validated tools that focus on the assessment of the methodological strengths and limitations of qualitative studies (see Box 21.8.a ). Pragmatically, we consider a ‘validated’ tool as one that has been subjected to evaluation. Issues such as inter-rater reliability are afforded less importance given that identification of complementary or conflicting perspectives on risk to rigour is considered more useful than achievement of consensus per se (Noyes et al 2019).

The CASP tool for qualitative research (as one example) maps onto the domains in Box 21.8.a (CASP 2013). Tools not meeting the criterion of focusing on assessment of methodological strengths and limitations include those that integrate assessment of the quality of reporting (such as scoring of the title and abstract, etc) into an overall assessment of methodological strengths and limitations. As with other risk of bias assessment tools, we strongly recommend against the application of scores to domains or calculation of total quality scores. We encourage review authors to discuss the studies and their assessments of ‘risk to rigour’ for each paper and how the study’s methodological limitations may affect review findings (Noyes et al 2019). We further advise that qualitative ‘sensitivity analysis’, exploring the robustness of the synthesis and its vulnerability to methodologically limited studies, be routinely applied regardless of the review authors’ overall confidence in synthesized findings (Carroll et al 2013). Evidence suggests that qualitative sensitivity analysis is equally advisable for mixed methods studies from which the qualitative component is extracted (Verhage and Boels 2017).

Box 21.8.a Example domains that provide an assessment of methodological strengths and limitations to determine study rigour

| Clear aims and research question Congruence between the research aims/question and research design/method(s) Rigour of case and or participant identification, sampling and data collection to address the question Appropriate application of the method Richness/conceptual depth of findings Exploration of deviant cases and alternative explanations Reflexivity of the researchers* *Reflexivity encourages qualitative researchers and reviewers to consider the actual and potential impacts of the researcher on the context, research participants and the interpretation and reporting of data and findings (Newton et al 2012). Being reflexive entails making conflicts of interest transparent, discussing the impact of the reviewers and their decisions on the review process and findings and making transparent any issues discussed and subsequent decisions. |

Adapted from Noyes et al (2019) and Alvesson and Sköldberg (2009)

21.8.1 Additional assessment of methodological strengths and limitations of process evaluation and intervention implementation evidence

Few assessment tools explicitly address rigour in process evaluation or implementation evidence. For qualitative primary studies, the 8-item process evaluation tool developed by the EPPI-Centre (Rees et al 2009, Shepherd et al 2010) can be used to supplement tools selected to assess methodological strengths and limitations and risks to rigour in primary qualitative studies. One of these items, a question on usefulness (framed as ‘how well the intervention processes were described and whether or not the process data could illuminate why or how the interventions worked or did not work’ ) offers a mechanism for exploring process mechanisms (Cargo et al 2018).

21.9 Selecting studies to synthesize

Decisions about inclusion or exclusion of studies can be more complex in qualitative evidence syntheses compared to reviews of trials that aim to include all relevant studies. Decisions on whether to include all studies or to select a sample of studies depend on a range of general and review specific criteria that Noyes and colleagues (Noyes et al (2019) outline in detail. The number of qualitative studies selected needs to be consistent with a manageable synthesis, and the contexts of the included studies should enable integration with the trials in the effectiveness analysis (see Figure 21.2.a ). The guiding principle is transparency in the reporting of all decisions and their rationale.

21.10 Selecting a qualitative evidence synthesis and data extraction method

Authors will typically find that they cannot select an appropriate synthesis method until the pool of available qualitative evidence has been thoroughly scoped. Flexible options concerning choice of method may need to be articulated in the protocol.

The INTEGRATE-HTA guidance on selecting methodology and methods for qualitative evidence synthesis and health technology assessment offers a useful starting point when selecting a method of synthesis (Booth et al 2016, Booth et al 2018). Some methods are designed primarily to develop findings at a descriptive level and thus directly feed into lines of action for policy and practice. Others hold the capacity to develop new theory (e.g. meta-ethnography and theory building approaches to thematic synthesis). Noyes and colleagues (Noyes et al (2019) and Flemming and colleagues (Flemming et al (2019) elaborate on key issues for consideration when selecting a method that is particularly suited to a Cochrane Review and decision making context (see Table 21.10.a ). Three qualitative evidence synthesis methods (thematic synthesis, framework synthesis and meta-ethnography) are recommended to produce syntheses that can subsequently be integrated with an intervention review or analysis.

Table 21.10.a Recommended methods for undertaking a qualitative evidence synthesis for subsequent integration with an intervention review, or as part of a mixed-method review (adapted from an original source developed by convenors (Flemming et al 2019, Noyes et al 2019))

|

|

|

|

| |

| Thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden 2008) | Most accessible form of synthesis. Clear approach, can be used with ‘thin’ data to produce descriptive themes and with ‘thicker’ data to develop descriptive themes in to more in-depth analytic themes. Themes are then integrated within the quantitative synthesis. May be limited in interpretive ‘power’ and risks over-simplistic use and thus not truly informing decision making such as guidelines. Complex synthesis process that requires an experienced team. Theoretical findings may combine empirical evidence, expert opinion and conjecture to form hypotheses. More work is needed on how GRADE CERQual to assess confidence in synthesized qualitative findings (see Section ) can be applied to theoretical findings. May lack clarity on how higher-level findings translate into actionable points. |

|

| |

| Framework synthesis (Oliver et al 2008, Dixon-Woods 2011) Best-fit framework synthesis (Carroll et al 2011) | Works well within reviews of complex interventions by accommodating complexity within the framework, including representation of theory. The framework allows a clear mechanism for integration of qualitative and quantitative evidence in an aggregative way – see Noyes et al (2018a). Works well where there is broad agreement about the nature of interventions and their desired impacts. Requires identification, selection and justification of framework. A framework may be revealed as inappropriate only once extraction/synthesis is underway. Risk of simplistically forcing data into a framework for expedience. |

|

| |

| Meta-ethnography (Noblit and Hare 1988) | Primarily interpretive synthesis method leading to creation of descriptive as well as new high order constructs. Descriptive and theoretical findings can help inform decision making such as guidelines. Explicit reporting standards have been developed. Complex methodology and synthesis process that requires highly experienced team. Can take more time and resources than other methodologies. Theoretical findings may combine empirical evidence, expert opinion and conjecture to form hypotheses. May not satisfy requirements for an audit trail (although new reporting guidelines will help overcome this (France et al 2019). More work is needed to determine how CERQual can be applied to theoretical findings. May be unclear how higher-level findings translate into actionable points. |

21.11 Data extraction

Qualitative findings may take the form of quotations from participants, subthemes and themes identified by the study’s authors, explanations, hypotheses or new theory, or observational excerpts and author interpretations of these data (Sandelowski and Barroso 2002). Findings may be presented as a narrative, or summarized and displayed as tables, infographics or logic models and potentially located in any part of the paper (Noyes et al 2019).

Methods for qualitative data extraction vary according to the synthesis method selected. Data extraction is not sequential and linear; often, it involves moving backwards and forwards between review stages. Review teams will need regular meetings to discuss and further interrogate the evidence and thereby achieve a shared understanding. It may be helpful to draw on a key stakeholder group to help in interpreting the evidence and in formulating key findings. Additional approaches (such as subgroup analysis) can be used to explore evidence from specific contexts further.

Irrespective of the review type and choice of synthesis method, we consider it best practice to extract detailed contextual and methodological information on each study and to report this information in a table of ‘Characteristics of included studies’ (see Table 21.11.a ). The template for intervention description and replication TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al 2014) and ICAT_SR tool may help with specifying key information for extraction (Lewin et al 2017). Review authors must ensure that they preserve the context of the primary study data during the extraction and synthesis process to prevent misinterpretation of primary studies (Noyes et al 2019).

Table 21.11.a Contextual and methodological information for inclusion within a table of ‘Characteristics of included studies’. From Noyes et al (2019). Reproduced with permission of BMJ Publishing Group

|

|

|

| Context and participants | Important elements of study context, relevant to addressing the review question and locating the context of the primary study; for example, the study setting, population characteristics, participants and participant characteristics, the intervention delivered (if appropriate), etc. |

| Study design and methods used | Methodological design and approach taken by the study; methods for identifying the sample recruitment; the specific data collection and analysis methods utilized; and any theoretical models used to interpret or contextualize the findings. |

Noyes and colleagues (Noyes et al (2019) provide additional guidance and examples of the various methods of data extraction. It is usual for review authors to select one method. In summary, extraction methods can be grouped as follows.

- Using a bespoke universal, standardized or adapted data extraction template Review authors can develop their own review-specific data extraction template, or select a generic data extraction template by study type (e.g. templates developed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (National Institute for Health Care Excellence 2012).

- Using an a priori theory or predetermined framework to extract data Framework synthesis, and its subvariant ‘Best Fit’ Framework approach, involve extracting data from primary studies against an a priori framework in order to better understand a phenomenon of interest (Carroll et al 2011, Carroll et al 2013). For example, Glenton and colleagues (Glenton et al (2013) extracted data against a modified SURE Framework (2011) to synthesize factors affecting the implementation of lay health worker interventions. The SURE framework enumerates possible factors that may influence the implementation of health system interventions (SURE (Supporting the Use of Research Evidence) Collaboration 2011, Glenton et al 2013). Use of the ‘PROGRESS’ (place of residence, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status, and social capital) framework also helps to ensure that data extraction maintains an explicit equity focus (O'Neill et al 2014). A logic model can also be used as a framework for data extraction.

- Using a software program to code original studies inductively A wide range of software products have been developed by systematic review organizations (such as EPPI-Reviewer (Thomas et al 2010)). Most software for the analysis of primary qualitative data – such as NVivo ( www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/home ) and others – can be used to code studies in a systematic review (Houghton et al 2017). For example, one method of data extraction and thematic synthesis involves coding the original studies using a software program to build inductive descriptive themes and a theoretical explanation of phenomena of interest (Thomas and Harden 2008). Thomas and Harden (2008) provide a worked example to demonstrate coding and developing a new understanding of children’s choices and motivations to eating fruit and vegetables from included primary studies.

21.12 Assessing the confidence in qualitative synthesized findings

The GRADE system has long featured in assessing the certainty of quantitative findings and application of its qualitative counterpart, GRADE-CERQual, is recommended for Cochrane qualitative evidence syntheses (Lewin et al 2015). CERQual has four components (relevance, methodological limitations, adequacy and coherence) which are used to formulate an overall assessment of confidence in the synthesized qualitative finding. Guidance on its components and reporting requirements have been published in a series in Implementation Science (Lewin et al 2018).

21.13 Methods for integrating the qualitative evidence synthesis with an intervention review

A range of methods and tools is available for data integration or mixed-method synthesis (Harden et al 2018, Noyes et al 2019). As noted at the beginning of this chapter, review authors can integrate a qualitative evidence synthesis with an existing intervention review published on a similar topic (sequential approach), or conduct a new intervention review and qualitative evidence syntheses in parallel before integration (convergent approach). Irrespective of whether the qualitative synthesis is sequential or convergent to the intervention review, we recommend that qualitative and quantitative evidence be synthesized separately using appropriate methods before integration (Harden et al 2018). The scope for integration can be more limited with a pre-existing intervention review unless review authors have access to the data underlying the intervention review report.

Harden and colleagues and Noyes and colleagues outline the following methods and tools for integration with an intervention review (Harden et al 2018, Noyes et al 2019):

- Juxtaposing findings in a matrix Juxtaposition is driven by the findings from the qualitative evidence synthesis (e.g. intervention components related to the acceptability or feasibility of the interventions) and these findings form one side of the matrix. Findings on intervention effects (e.g. improves outcome, no difference in outcome, uncertain effects) form the other side of the matrix. Quantitative studies are grouped according to findings on intervention effects and the presence or absence of features specified by the hypotheses generated from the qualitative synthesis (Candy et al 2011). Observed patterns in the matrix are used to explain differences in the findings of the quantitative studies and to identify gaps in research (van Grootel et al 2017). (See, for example, (Ames et al 2017, Munabi-Babigumira et al 2017, Hurley et al 2018)