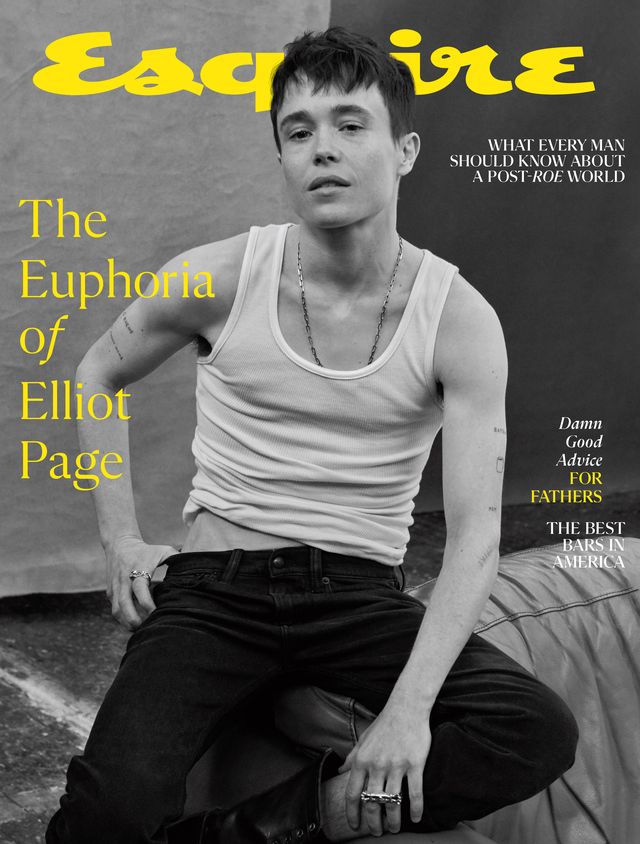

For Whom Does the American Flag Fly?

I’m in no hurry to wave it, but don’t tell me I don’t love my country.

You couldn’t not notice it: a multitude gathered one morning at an A gate of Phoenix’s Sky Harbor Airport, waving little American flags, recording on their cell phones, laying a soundtrack of exuberant cheers. Intrigued or just nosy, I stopped for a look-see, noticed that walls behind the gate desk were adorned with red-white-and-blue bunting, that other walls featured a slogan saluting all those who serve and their families, that the area was also bedecked with flags: an American flag along with those representing the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, Coast Guard, even the one for POW/MIA. Yonder, an agent stood at the mouth of the Jetway and called out the deplaning passengers as if announcing the Suns playoff starters: “From the U. S. Air Force staff . . . !” “From the U. S. Navy . . . !” “Electronics technician first class . . . !” First-class petty officer . . . !” “USS Mission Bay rank third class . . . !” Given their hoary hair, their wrinkled mugs, and the fact that some of them caned out of the jet bridge or were pushed in a wheelchair, I surmised that all who exited had earned the honorific of veteran.

It heartened me to see that kind of appreciation for our veterans, so much so that I dawdled past my first urge to leave, so much so that I joined in rounds of applause. Though my enthusiasm was sincere, truth be told, it was also tempered. Matter fact, had somebody tried to hand me a little mini flag, I might’ve refused it and for damn sure would’ve been reluctant to wave it.

Well, because while I believe it commendable and crucial to honor the people who’ve risked or made the ultimate sacrifice for their/our country, my relationship to the flag is at best complicated, at worst ruined.

The year after it declared independence, the Continental Congress passed the first Flag Act, solidifying the Stars and Stripes as the symbol of America, even boasting that the 13 stars on the Betsy Ross version represented “a new constellation.” The second Flag Act, in 1794, provided for 15 stars and 15 stripes (the famous Star-Spangled Banner that inspired Francis Scott Key) to rep the newest states. Of course, the good old U. S. of A. kept right on manifesting its destiny, a mission that also made for some awkward designs.

In 1818, Congress passed the third Flag Act, legislating that it would return to the original 13 stripes to represent the colonies but would add a star for each new state. That third act didn’t specify a design for the stars, and that vagueness led to the production of several versions, that is until 1912, when an executive order by President Taft prescribed not only the order of the stars but the proportions of the flag. Two more executive orders, both by President Eisenhower in 1959, further specified the arrangement of the stars, the later one establishing the design of our current flag.

The vexillologists would have me believe the red of Old Glory symbolizes “hardiness and valor”; its white “purity and innocence”; its blue “vigilance, perseverance, and justice.”

While I accept those qualities as its symbolic ideals, I also believe that the quiddity of the flag is a question: Who belongs in America?

Which is a query evermore inextricable from who owns America.

Given the centuries that we were chattel, the long rule of Jim Crow, and the machinations fueling mass incarceration, I can say with certainty that it ain’t been my peoples. Nonetheless, given Native American pogroms and the Indian Removal and Relocation Acts; given Japanese internment; given the hundred-year-plus crusade for women’s suffrage and the leaked intent for SCOTUS to nullify Roe v. Wade; given the extant rampant schemes of voter suppression and the proliferation of ardent anti-LGBTQ legislation; given the border wall and the inhumanity of brown babies in cages; given the forging of the wealth gap and the cruel persistence of health disparities; given, given, the givens . . . the answer to that essential question is that it might not have been your people neither.

And furthermore, during the fascistic previous administration, the Americans most visible and vocal about their belonging and ownership were the ones hell-bent on using the flag as a cudgel against anybody deemed an other and/or as a scythe to cleave division.

And let me add that, often, they’re the same ones proclaiming themselves true patriots.

In George Orwell’s classic essay “Notes on Nationalism,” he defines patriotism as “devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people” and defines nationalism as “the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing no other duty than that of advancing its interests.” Orwell acknowledges that there’s often little distinction between the two and yet argues that “patriotism is of its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally” but “nationalism, on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power.”

In addition to being grounded in America’s complicated history, my resistance to revering the flag—and other symbols of American virtue—is fueled by the belief that Orwell’s distinctions may no longer exist, that the middle ground is now a chasm, that we’ve atrophied into (or maybe we’ve just been exposed as) an era in which nationalism, of a sort indistinguishable from jingoism, has by and large subsumed the patriot.

But I also concede that my perspective has been colored by what’s made the news—the vehemence over Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling; the tiki torchers threatening, “You will not replace us”; the MAGA insurgents, many clad in patriotic colors, rioting through the halls of the Capitol—and that there are also plenty of Americans who believe this country capable of achieving the ideals enshrined in its founding documents and symbols, whose hoisting of a flag outside their crib won’t make the headlines but who are just as important, if not more important, to defining and extending its virtues.

One such acolyte is a buddy of mine—he identifies as a white guy, which seems essential to mention—who says he’ll continue to raise a flag out of respect and duty, that he isn’t about to let the KKK/Proud Boys/Oath Keepers/Three Percenters of the world usurp its meaning. His arguments, I admit, make a helluva lot of sense.

But for me? Could the flag ever belong to me and mines? Would it ever be a fitting emblem of our experience? Can we—those who belong to groups coerced into a hyphenated lower class of Americanness—have any lasting impact on its significance?

My buddy asked if I intended to raise a flag outside my house this Fourth of July, and I said no—said it quick, too—and then the very next instant worried whether that decision would make me less American, less deserving of the mythic American dream of prosperity, somehow less worthy of experiencing the highest potential of this place where I was born and, in all likelihood, will die.

A week or so after I stumbled upon the celebrated arrival of a planeload of veterans, I returned from another trip and stopped by the very same gate. That day, there was no excited crowd, no gate agent broadcasting names, no veterans strolling or limping or wheeling off the jet bridge. However, still—the slogan honoring those who served. Still—the patriotic bunting. Still—the beaucoup flags along the walls. All of them inanimate, inert, waiting for someone to come along and imbue them with consequence.

Mitchell S Jackson is a contributing writer for Esquire. He is the winner of a Pulitzer Prize and a National Magazine Award as well as the acclaimed author of the memoir Survival Math , and the award-winning novel The Residue Years . He is the John O. Whiteman Dean's Distinguished Professor of English at Arizona State University.

@media(max-width: 73.75rem){.css-1ktbcds:before{margin-right:0.4375rem;color:#FF3A30;content:'_';display:inline-block;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1ktbcds:before{margin-right:0.5625rem;color:#FF3A30;content:'_';display:inline-block;}} News

The Grisly Reality of Abortion Care in Idaho

Trump on Trial: Day Two

The Play About a Mass Shooting You Need to See

Cotton and Hawley Want to Send In the Troops

If You Read Only One Thing About Earth Day

No Cannibal Jokes, Joe Biden

What It's Like Being an Oysterman

Mike Johnson Is No Winston Churchill, Folks

We Could Use a Little Wright Patman Right Now

A Man Set Himself on Fire Outside the Trump Trial

Mike Johnson’s Last Act as Speaker?

No country has changed its flag as frequently as the United States. In 1817 Congressman Peter Wendover wrote the current flag law. The number of stripes was permanently limited to 13; the stars were to correspond to the number of states, with new stars added to the flag the following Fourth of July. Star arrangement was not specified, however, and throughout the 19th century a variety of exuberant star designs—“great luminaries,” rings, ovals, and diamonds—were actually used. Finally, in 1912, President Taft set forth exact regulations for all flag details.

- HISTORY & CULTURE

Flag Day's long—and surprising—history explained

Decreed by each president, this June holiday honors the American flag, a key symbol of the republic.

Red, white, and backed by a narrative almost as long as the nation—the official tri-colored, star-spangled banner that tops government buildings and citizen homes across the United States first waved on June 14, 1777 (albeit in a different configuration). To celebrate the American flag, June 14 is thus known as Flag Day.

Although Flag Day is observed on a smaller scale than neighboring patriotic holidays like Memorial Day and Independence Day , the observance has its own rich history. Here's what to know about how Flag Day got started—and how the flag has changed through the years.

How Flag Day began

But it received national recognition, Flag Day was pioneered by a number of patriotic citizens.

Bernard Cigrand, a nineteenth century Wisconsin school teacher, dentist, and reporter, is sometimes considered the “ father of Flag Day .”

In 1885—when Cigrand was 19 years old and the flag contained 38 stars—the young teacher instructed his students in Ozaukee County to write essays entitled, “What the American flag means to me.” In the years that followed, Cigrand wrote several

Flags from around the world

newspaper articles and books advocating for the creation of the holiday, including a public proposal in the Chicago Argus newspaper in 1886.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Cigrand died 17 years before the Congressional statute was passed, but Ozaukee County’s National Flag Day Foundation honors his legacy each June. And, on June 14, 2004, Congress passed an additional resolution officially recognizing that Flag Day originated in Ozaukee County.

In response, National Flag Day Foundation Chairman Jack Janik said at the time, “The community is overwhelmed, they’re so proud.”

The foundation holds such Flag Day events as a parade, family festival, and fireworks and curates three public museums, including one specifically dedicated to Cigrand.

Others also credited for promoting Flag Day in the late 1800s include William T. Kerr , a Pittsburgh native and founder of the Flag Day Association of Western Pennsylvania, Elizabeth Duane Gillespie , a descendent of Benjamin Franklin who petitioned for all public buildings to display the American flag, and George Bolch , a principal in New York whose school celebrated Flag Day in 1889.

How Flag Day became a national observance

Flag Day’s national debut came in 1916 , almost two centuries—and more than 20 designs—after the flag’s adoption in the United States. On June 14 of that year, President Woodrow Wilson issued a proclamation acknowledging the holiday.

You May Also Like

Was Manhattan really sold to the Dutch for just $24?

This dish towel ended the Civil War

Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces

President Calvin Coolidge issued a similar Flag Day proclamation in 1927 . Congress recognized Flag Day with an official statute a few decades later, in 1949 , under the Truman administration. The statute requested presidents issue annual Flag Day proclamations but did not designate it an official national holiday . Even so, all presidents since 1949 have issued a Flag Day proclamation.

How the American flag has changed

Today’s flag has undergone numerous modifications— 26, to be exact —since the 1777 model.

The original, sometimes dubbed “The Betsy Ross”—though few researchers express confidence that Ross created the first flag—displayed 13 stars and 13 stripes, with the stars arranged in a circle.

The latest edition, consisting of 50 stars and 13 stripes, was created in the late 1950s. While Alaska and Hawaii were being considered for statehood, then-president Dwight Eisenhower asked for design proposals for a new flag. Among the hundreds of submissions received, there were reportedly at least three for the current flag. Most famously, one of those had been sent by then-high school junior Bob Heft of Ohio, who had designed the 50-star flag for a class assignment. Heft , who died in 2009, received a B- from an unimpressed teacher , who reportedly called the design unoriginal.

Over the next two years, Heft wrote letters and called the White House numerous times seeking his flag’s approval. He also mailed the design to his congressman, Walter Moeller , who took up the banner. Alaska and Hawaii joined the nation in 1959 and the new design became official on July 4, 1960. Heft’s design earned its rightful “A” from his teacher—and he earned himself a White House visit.

Currently, Congress stipulates that when a new state joins the nation, a new star will be added to the flag in a proportional design the following Independence Day. The stripes remain capped at 13 to represent the 13 original colonies. Non-state U.S. jurisdictions like Puerto Rico remain unrepresented in the flag.

The flag's symbolic meaning

The flag’s symbolic meaning was not publicized until 1782, with the creation of the United States’ seal. At the seal’s unveiling, Charles Thompson , the secretary to the Continental Congress and primary designer of the seal, said the white signified purity and innocence, the red signified hardiness and valor, and the blue signified vigilance, perseverance, and justice.

Others have offered their own interpretations, with common ones being that red symbolizes the blood of the fallen, or stripes mimic rays of sunlight. Whatever the interpretation, the symbolic nature of the American flag’s design may echo the country’s individualist foundations.

In contrast to the United Kingdom’s flag, often called the “ Union Jack, ” which consists of the overlapping crosses of St. George, St. Andrew, and St. Patrick, the American flag pays tribute to no one person or religion.

As has been the case with their country, Americans have changed their flag throughout the years. Flag Day honors this evolving emblem.

Related Topics

- COLONIAL AMERICA

These 5 cities vanished without a trace. We're finally learning their stories.

What is colonialism?

He was the last king of America. Here’s how he lost the colonies.

These 5 secret societies changed the world—from behind closed doors

These enigmatic documents have kept their secrets for centuries

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

- History & Culture

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Essay Sample on Why I Honor The American Flag

The American flag is a representation of liberty, justice, and loyalty. It represents the best aspects of our country and its people. The flag serves as a symbol of what makes us special, including our ability to overcome hardship, our dedication to justice and fairness, and our dedication to upholding the rights of all people. Respecting the flag is a way to honor those who have sacrificed their lives for our nation. In this essay, written with the help of the professional custom essay writing service Edusson, I’ll share why I honor the American flag.

What the American Flag Essay Means to Me

The American flag represents our shared history as a nation. It is a symbol of the struggles and triumphs of our founding fathers as they fought for independence from England. The thirteen stripes represent the original thirteen colonies, and the stars on the blue field represent the states that make up our nation. Each time I see the flag, it serves as a reminder of the hard work, dedication, and sacrifice that have gone into building this country.

According to history, the flag of the USA has been an essential symbol since its adoption by Congress on June 14, 1777. The flag represented America’s break from Britain’s King George III and his oppressive rule over our country. After winning its independence from Britain in 1783 with help from France, America adopted its first official national flag: the Grand Union Flag (a British Union Flag with 13 stripes). This design was never officially adopted as an official national ensign because it was too similar to another flag used by privateers at sea during the American Revolution known as “The Pirate Jack” (a red cross on a white field).

On June 14th, 1777 Congress passed an act establishing an official United States Flag consisting of 13 alternating red and white stripes representing the 13 original colonies; and a blue canton bearing 13 white stars representing a new constellation.

The Symbolism Behind the Flag

To me, the American flag isn’t just a piece of cloth — it’s a symbol that represents all that is good about our country. It stands for freedom from tyranny, justice for all people regardless of race or creed, and a commitment to defend those who cannot defend themselves. When I look at the flag, I am reminded of how far we have come as a nation — from fighting for independence from Great Britain to become a beacon of hope for people around the world.

The Colors and Symbols of the Flag

The colors and symbols on the American flag represent our nation’s history, values, and principles. Red stands for valor and bravery, white represents purity and innocence, while blue signifies perseverance and justice. The 50 stars on the blue field are a reminder that we are united as one nation with 50 states working in harmony towards a common goal — liberty for all.

Respect for Our Veterans

One way that I honor the American flag is by respecting those who have served in our military. Our veterans put their lives on the line so that we can continue to live in freedom and security. We owe them an immense debt of gratitude that can never be repaid; however, we can show our appreciation by displaying flags on Veteran’s Day (and other holidays) or by volunteering with veteran-focused organizations.

Giving Back to Our Country

Another way that I honor the American flag is by giving back to my community and country whenever possible. This could take many forms— from volunteering with local charities or political campaigns to donating money or goods to those in need. No matter how you choose to give back, it’s important to remember that every act helps make America better than it was before you got involved.

Honoring the Flag

It can be easy to take these symbols for granted, but honoring them should be our priority as citizens of this great nation. We should always respect our flag by saluting it when it passes by during parades or ceremonies; we should never let it touch the ground; we should also ensure that we display it properly at home or work with care. We must remember to treat our national symbol with dignity so that future generations can continue to appreciate its importance in our culture.

Conclusion

The American Flag has been an integral part of America since its inception more than 200 years ago. It stands for everything we stand for as Americans — freedom from oppression, justice for all people regardless of race or creed, and dedication to protecting those who cannot protect themselves. As an individual citizen and member of this great nation, honoring this symbol is one way I can show my appreciation for what makes America unique and special — something worth celebrating each day!

Tips on Writing Why I Honor the American Flag Essay

It is true that a personal statement essay can be the most important piece of writing you submit to a university. The statement is what can make or break your application, so it’s important to make sure you get it right. Writing this American flag essay, first I’ve looked through personal statement essay examples . Writing an essay on Why you honor the American flag can be a personal and emotional experience, and it can be challenging to put those feelings into words. Here are some tips to help you write an effective essay

Brainstorm

Start by jotting down your thoughts and feelings about the American flag. What does it represent to you? What memories or experiences do you associate with it? These brainstorming ideas can be useful when you start to write your essay.

Use strong language

Use strong and persuasive language to express your ideas. Avoid generalities or clichés, and instead use language that is specific, vivid, and engaging.

Show your patriotism

Finally, use your essay as an opportunity to show your patriotism and love for your country. Your essay can serve as a testament to your pride in being an American and your commitment to the values that the American flag represents.

In this table, we will explore the reasons why people honor the American flag and what it means to them.

Related posts:

- Persuasive essay examples that work for college in 2022

- Racism: A Cause and Effect Essay Sample

- Earthquake Cause and Effect Essay Sample

- Essay Sample on Why i Want to Be a Veterinarian

Improve your writing with our guides

Youth Culture Essay Prompt and Discussion

Why Should College Athletes Be Paid, Essay Sample

Reasons Why Minimum Wage Should Be Raised Essay: Benefits for Workers, Society, and The Economy

Get 15% off your first order with edusson.

Connect with a professional writer within minutes by placing your first order. No matter the subject, difficulty, academic level or document type, our writers have the skills to complete it.

100% privacy. No spam ever.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

The American Flag Belongs to Me, Too, and This Year I’m Taking It Back

By Margaret Renkl

Ms. Renkl is a contributing Opinion writer who covers flora, fauna, politics and culture in the American South.

NASHVILLE — We bought our house from a military veteran who hauled his flag out on every officially patriotic occasion. It hung from a flag mount embedded in the bark of a maple tree, and during our first years in the house we followed suit, at least on the Fourth of July.

Back then our neighborhood always threw a block party on the Fourth. Children decorated their bicycles and their dogs and careened down the street in what was generously referred to as a parade. Parents vaguely supervised the obligatory games — a three-legged race, an egg toss — but mostly we sat in the shade to chat until it was time for the potluck.

There was never any mention of politics. If I knew a neighbor’s party affiliation, it meant we were friends , and friends in those days granted one another the grace to assume that good will prevailed on both sides. We were all proud to be Americans, even if we didn’t agree about which aspects of our sprawling, messy democracy merited pride.

Traditionally, white Southerners aren’t big on the flag. The Fall of Vicksburg took place on July 4, 1863. A Civil War battle lost by the Confederacy on the anniversary of the founding of the Union meant that many Southerners considered the Fourth of July a Yankee holiday. For decades .

Today the American flag has been co-opted by the very cohort who rejected it so roundly during my childhood. Driving through rural Tennessee last week, I saw an American flag hanging from the bucket of a cherry picker parked on the side of the road. The flag waved above a tent offering fireworks for sale. The flag was even bigger than the tent.

Take a drive through any red state, and you will see American flags flying above truck stops, dangling from construction cranes, stretched across the back windshields of cars, emblazoned on clothing and, of course, waving from front porches — and not just on the Fourth of July. “The sheer volume of American flag paraphernalia that white people seem to own boggles my mind,” tweeted the Times columnist Tressie McMillan Cottom last month. “I assume it just sort of flows to them & they aren’t buying all of it? I’m not sure.”

I’m pretty sure white people are buying this stuff.

But not all of us. Old Glory has become such a strong feature of Trump rallies that many liberals have all but rejected it, unwilling to embrace the symbol of a worldview that we find anathema. “Today, flying the flag from the back of a pickup truck or over a lawn is increasingly seen as a clue, albeit an imperfect one, to a person’s political affiliation in a deeply divided nation,” Sarah Maslin Nir wrote last year in The Times.

My husband and I stopped hanging up our own flag years ago, long before it got usurped by the MAGA crowd. Our old maple tree had simply grown around the flag mount over the years, eventually enfolding it entirely, and we never got around to putting up another.

I’ve had plenty of reason to doubt the viability of the American experiment. I was born during the Vietnam War in the segregated South. I watched the Watergate hearings on television as a child. I saw my government launch an unprovoked ground invasion into another country and conduct covert drone warfare in another. I wept when it locked babies in cages at the border.

But no other time in my life has caused me to doubt American democracy so profoundly as I doubt it now. The Supreme Court has issued opinions tying the hands of liberal state legislators trying to protect their citizens from gun violence while simultaneously handing to conservative state legislators total control over their citizens’ reproductive rights . The final ruling of this session hamstrings the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to fight climate change.

The majority of Americans did not want the Court to overturn Roe . They don’t want to be surrounded by guns . They are deeply worried about climate change . With these Supreme Court rulings, the law of the land no longer reflects the will of the people who live here.

I am struggling terribly with this reality. I have staked my entire worldview on the belief that people are mostly good, even when we don’t agree with one another, but I find myself now fighting a raging internal battle not to hate everyone whose decisions, large and small, have led to this political moment.

I try to remind myself that Americans have always had reason to despair, to suspect that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was overly hopeful when he told us that the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice. And then I remember all the times when this wild, unstoppable, unwarranted hope — hope that motivated millions of people to log numberless hours of painstaking work — managed somehow to yield previously unthinkable triumphs.

In 2015, my family and I were among the crowd of marriage-equality advocates waiting outside the Supreme Court for a ruling in the Obergefell v. Hodges case. (I have written about this experience at greater length here .) The best-case scenario, everyone around us agreed, was a ruling that required states that had banned same-sex marriage to recognize marriages performed in states where it was legal. I will never forget the untrammeled joy that exploded when the ruling went even further, identifying marriage as a constitutional right.

I will also never forget what happened next: The jubilant crowd began to sing the national anthem.

I find myself coming back again and again to that heart-lifting experience, the way it happened only because marriage-equality advocates kept pressing for change despite decades of setbacks, against the constant threat — and often the reality — of violence. I think about the singing, about how in that first flush of profound, unexpected joy, what came to mind was the promise this country still holds.

It should not be so unbearably hard for justice to prevail, and justice finally gained should never again be at risk. But this is the country we live in. The fight for freedom will never be over. And, God help me, I will not be one who gives up. This is my country, too, and I will not surrender it to a vocal minority of undemocratic tyrants.

So this Fourth of July weekend, my husband and I have hung up an American flag again for the first time in years. It’s right next to the front door, and it does not symbolize MAGA lies or MAGA tyranny. We are flying it proudly in honor of our fellow Americans who are fighting for justice of every kind.

But to be very clear about which America we believe in, we have hung a different flag on the other side of the front door, too. When the wind blows the American flag at our house, a rainbow flag will be billowing beside it.

Margaret Renkl, a contributing Opinion writer, is the author of the books “ Graceland, at Last: Notes on Hope and Heartache From the American South ” and “ Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss .”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

Home / Essay Samples / Government / American Flag / What the American Flag Means to Me: A Personal Reflection

What the American Flag Means to Me: A Personal Reflection

- Category: Government

- Topic: American Flag

Pages: 1 (454 words)

- Downloads: -->

--> ⚠️ Remember: This essay was written and uploaded by an--> click here.

Found a great essay sample but want a unique one?

are ready to help you with your essay

You won’t be charged yet!

Police Brutality Essays

Social Security Essays

Public Transport Essays

War on Drugs Essays

Transportation Essays

Related Essays

We are glad that you like it, but you cannot copy from our website. Just insert your email and this sample will be sent to you.

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Your essay sample has been sent.

In fact, there is a way to get an original essay! Turn to our writers and order a plagiarism-free paper.

samplius.com uses cookies to offer you the best service possible.By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .--> -->