An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review

Jiaqi xiong.

a Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

Orly Lipsitz

c Mood Disorders Psychopharmacology Unit, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario

Flora Nasri

Leanna m.w. lui, hartej gill, david chen-li, michelle iacobucci.

e Department of Psychological Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

f Institute for Health Innovation and Technology (iHealthtech), National University of Singapore, Singapore

Amna Majeed

Roger s. mcintyre.

b Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

d Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation, Toronto, ON

Associated Data

As a major virus outbreak in the 21st century, the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to unprecedented hazards to mental health globally. While psychological support is being provided to patients and healthcare workers, the general public's mental health requires significant attention as well. This systematic review aims to synthesize extant literature that reports on the effects of COVID-19 on psychological outcomes of the general population and its associated risk factors.

A systematic search was conducted on PubMed, Embase, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to 17 May 2020 following the PRISMA guidelines. A manual search on Google Scholar was performed to identify additional relevant studies. Articles were selected based on the predetermined eligibility criteria.

Results: Relatively high rates of symptoms of anxiety (6.33% to 50.9%), depression (14.6% to 48.3%), post-traumatic stress disorder (7% to 53.8%), psychological distress (34.43% to 38%), and stress (8.1% to 81.9%) are reported in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in China, Spain, Italy, Iran, the US, Turkey, Nepal, and Denmark. Risk factors associated with distress measures include female gender, younger age group (≤40 years), presence of chronic/psychiatric illnesses, unemployment, student status, and frequent exposure to social media/news concerning COVID-19.

Limitations

A significant degree of heterogeneity was noted across studies.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is associated with highly significant levels of psychological distress that, in many cases, would meet the threshold for clinical relevance. Mitigating the hazardous effects of COVID-19 on mental health is an international public health priority.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, a cluster of atypical cases of pneumonia was reported in Wuhan, China, which was later designated as Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 Feb 2020 ( Anand et al., 2020 ). The causative virus, SARS-CoV-2, was identified as a novel strain of coronaviruses that shares 79% genetic similarity with SARS-CoV from the 2003 SARS outbreak ( Anand et al., 2020 ). On 11 Mar 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak a global pandemic ( Anand et al., 2020 ).

The rapidly evolving situation has drastically altered people's lives, as well as multiple aspects of the global, public, and private economy. Declines in tourism, aviation, agriculture, and the finance industry owing to the COVID-19 outbreak are reported as massive reductions in both supply and demand aspects of the economy were mandated by governments internationally ( Nicola et al., 2020 ). The uncertainties and fears associated with the virus outbreak, along with mass lockdowns and economic recession are predicted to lead to increases in suicide as well as mental disorders associated with suicide. For example, McIntyre and Lee (2020b) have reported a projected increase in suicide from 418 to 2114 in Canadian suicide cases associated with joblessness. The foregoing result (i.e., rising trajectory of suicide) was also reported in the USA, Pakistan, India, France, Germany, and Italy ( Mamun and Ullah, 2020 ; Thakur and Jain, 2020 ). Separate lines of research have also reported an increase in psychological distress in the general population, persons with pre-existing mental disorders, as well as in healthcare workers ( Hao et al., 2020 ; Tan et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020b ). Taken together, there is an urgent call for more attention given to public mental health and policies to assist people through this challenging time.

The objective of this systematic review is to summarize extant literature that reported on the prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other forms of psychological distress in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. An additional objective was to identify factors that are associated with psychological distress.

Methods and results were formated based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines ( Moher et al., 2010 ).

2.1. Search strategy

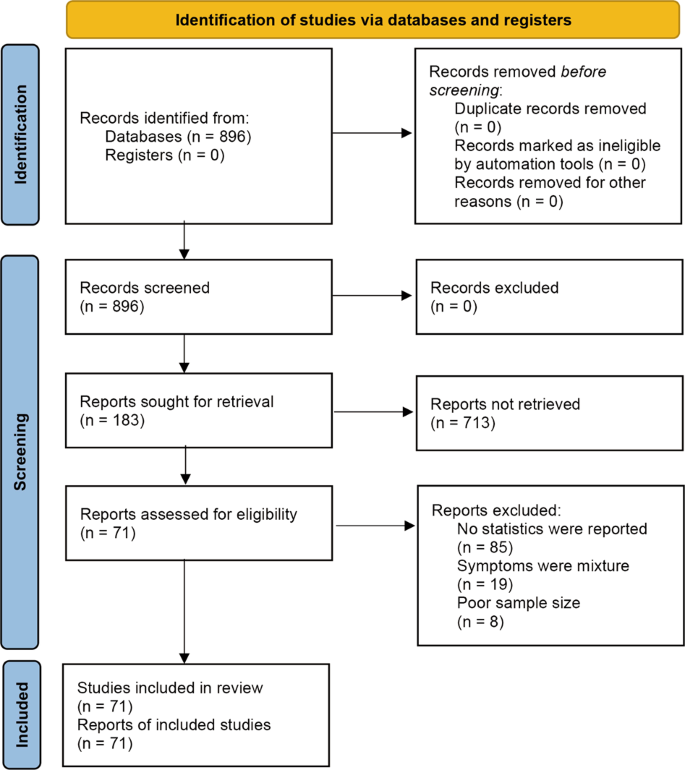

A systematic search following the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram ( Fig. 1 ) was conducted on PubMed, Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science from inception to 17 May 2020. A manual search on Google Scholar was performed to identify additional relevant studies. The search terms that were used were: (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 OR 2019nCoV OR HCoV-19) AND (Mental health OR Psychological health OR Depression OR Anxiety OR PTSD OR PTSS OR Post-traumatic stress disorder OR Post-traumatic stress symptoms) AND (General population OR general public OR Public OR community). An example of search procedure was included as a supplementary file.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study selection flow diagram. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2. Study selection and eligibility criteria

Titles and abstracts of each publication were screened for relevance. Full-text articles were accessed for eligibility after the initial screening. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: 1) followed cross-sectional study design; 2) assessed the mental health status of the general population/public during the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated risk factors; 3) utilized standardized and validated scales for measurement. Studies were excluded if they: 1) were not written in English or Chinese; 2) focused on particular subgroups of the population (e.g., healthcare workers, college students, or pregnant women); 3) were not peer-reviewed; 4) did not have full-text availability.

2.3. Data extraction

A data extraction form was used to include relevant data: (1) Lead author and year of publication, (2) Country/region of the population studied, (3) Study design, (4) Sample size, (5) Sample characteristics, (6) Assessment tools, (7) Prevalence of symptoms of depression/anxiety/ PTSD/psychological distress/stress, (8) Associated risk factors.

2.4 Quality appraisal

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) adapted for cross-sectional studies was used for study quality appraisal, which was modified accordingly from the scale used in Epstein et al. (2018) . The scale consists of three dimensions: Selection, Comparability, and Outcome. There are seven categories in total, which assess the representativeness of the sample, sample size justification, comparability between respondents and non-respondents, ascertainments of exposure, comparability based on study design or analysis, assessment of the outcome, and appropriateness of statistical analysis. A list of specific questions was attached as a supplementary file. A total of nine stars can be awarded if the study meets certain criteria, with a maximum of four stars assigned for the selection dimension, a maximum of two stars assigned for the comparability dimension, and a maximum of three stars assigned for the outcome dimension.

3.1. Search results

In total, 648 publications were identified. Of those, 264 were removed after initial screening due to duplication. 343 articles were excluded based on the screening of titles and abstracts. 41 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. There were 12 articles excluded for studying specific subgroups of the population, five articles excluded for not having a standardized/ appropriate measure, three articles excluded for being review papers, and two articles excluded for being duplicates. Following the full-text screening, 19 studies met the inclusion criteria.

3.2. Study characteristics

Study characteristics and primary study findings are summarized in Table 1 . The sample size of the 19 studies ranged from 263 to 52,730 participants, with a total of 93,569 participants. A majority of study participants were over 18 years old. Female participants ( n = 60,006) made up 64.1% of the total sample. All studies followed a cross-sectional study design. The 19 studies were conducted in eight different countries, including China ( n = 10), Spain ( n = 2), Italy ( n = 2), Iran ( n = 1), the US ( n = 1), Turkey ( n = 1), Nepal ( n = 1), and Denmark ( n = 1). The primary outcomes chosen in the included studies varied across studies. Twelve studies included measures of depressive symptoms while eleven studies included measures of anxiety. Symptoms of PTSD/psychological impact of events were evaluated in four studies while three studies assessed psychological distress. It was additionally observed that four studies contained general measures of stress. Three studies did not explicitly report the overall prevalence rates of symptoms; notwithstanding the associated risk factors were identified and discussed.

Summary of study sample characteristics, study design, assessment tools used, prevalence rates and associated risk factors.

3.3. Quality appraisal

The result of the study quality appraisal is presented in Table 2 . The overall quality of the included studies is moderate, with total stars awarded varying from four to eight. There were two studies with four stars, two studies with five stars, seven studies with six stars, seven studies with seven stars, and one study with eight stars.

Results of study quality appraisal of the included studies.

3.4. Measurement tools

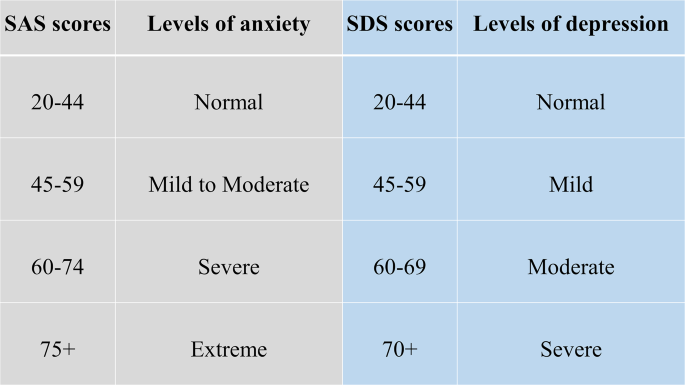

A variety of scales were used in the studies ( n = 19) for assessing different adverse psychological outcomes. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Patient Health Questionnaire-9/2 (PHQ-9/2), Self-rating Depression Scales (SDS), The World Health Organization-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) were used for measuring depressive symptoms. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7/2-item (GAD-7/2), and Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) were used to evaluate symptoms of anxiety. The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale- 21 items (DASS-21) was used for the evaluation of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used for assessing anxiety and depressive symptoms. Psychological distress was measured by The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (CPDI) and the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6/10). Symptoms of PTSD were assessed by The Impact of Event Scale-(Revised) (IES(-R)), PTSD Checklist (PCL-(C)-2/5). Chinese Perceived Stress Scale (CPSS-10) was used in one study to evaluate symptoms of stress.

3.5. Symptoms of depression and associated risk factors

Symptoms of depression were assessed in 12 out of the 19 studies ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and S.B. Özdin, 2020 ; Sønderskov et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ). The prevalence of depressive symptoms ranged from 14.6% to 48.3%. Although the reported rates are higher than previously estimated one-year prevalence (3.6% and 7.2%) of depression among the population prior to the pandemic ( Huang et al., 2019 ; Lim et al., 2018 ), it is important to note that presence of depressive symptoms does not reflect a clinical diagnosis of depression.

Many risk factors were identified to be associated with symptoms of depression amongst the COVID-19 pandemic. Females were reported as are generally more likely to develop depressive symptoms when compared to their male counterparts ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Sønderskov et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). Participants from the younger age group (≤40 years) presented with more depressive symptoms ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ;). Student status was also found to be a significant risk factor for developing more depressive symptoms as compared to other occupational statuses (i.e. employment or retirement) ( González et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ). Four studies also identified lower education levels as an associated factor with greater depressive symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). A single study by Wang et al., 2020b reported that people with higher education and professional jobs exhibited more depressive symptoms in comparison to less educated individuals and those in service or enterprise industries.

Other predictive factors for symptoms of depression included living in urban areas, poor self-rated health, high loneliness, being divorced/widowed, being single, lower household income, quarantine status, worry about being infected, property damage, unemployment, not having a child, a past history of mental stress or medical problems, having an acquaintance infected with COVID-19, perceived risks of unemployment, exposure to COVID-19 related news, higher perceived vulnerability, lower self-efficacy to protect themselves, the presence of chronic diseases, and the presence of specific physical symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ).

3.6. Symptoms of anxiety and associated risk factors

Anxiety symptoms were assessed in 11 out of the 19 studies, with a noticeable variation in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms ranging from 6.33% to 50.9% ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ).

Anxiety is often comorbid with depression ( Choi et al., 2020 ). Some predictive factors for depressive symptoms also apply to symptoms of anxiety, including a younger age group (≤40 years), lower education levels, poor self-rated health, high loneliness, female gender, divorced/widowed status, quarantine status, worry about being infected, property damage, history of mental health issue/medical problems, presence of chronic illness, living in urban areas, and the presence of specific physical symptoms ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ; Wang et al., 2020b ).

Additionally, social media exposure or frequent exposure to news/information concerning COVID-19 was positively associated with symptoms of anxiety ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ). With respect to marital status, one study reported that married participants had higher levels of anxiety when compared to unmarried participants ( Gao et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, Lei et al. (2020) found that divorced/widowed participants developed more anxiety symptoms than single or married individuals. A prolonged period of quarantine was also correlated with higher risks of anxiety symptoms. Intuitively, contact history with COVID-positive patients or objects may lead to more anxiety symptoms, which is noted in one study ( Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ).

3.7. Symptoms of PTSD/ psychological distress/stress and associated risk factors

With respect to PTSD symptoms, similar prevalence rates were reported by Zhang and Ma (2020) and N. Liu et al. (2020) at 7.6% and 7%, respectively. Despite using the same measurement scale as Zhang and Ma (2020) (i.e., IES), Wang et al. (2020a) noted a remarkably different result, with 53.8% of the participants reporting moderate-to-severe psychological impact. González et al. ( González-Sanguino et al., 2020 ) noted 15.8% of participants with PTSD symptoms. Three out of the four studies that measured the traumatic effects of COVID-19 reported that the female gender was more susceptible to develop symptoms of PTSD. In contrast, the research conducted by Zhang and Ma (2020) found no significant difference in IES scores between females and males. Other risk factors included loneliness, individuals currently residing in Wuhan or those who have been to Wuhan in the past several weeks (the hardest-hit city in China), individuals with higher susceptibility to the virus, poor sleep quality, student status, poor self-rated health, and the presence of specific physical symptoms. Besides sex, Zhang and Ma (2020) found that age, BMI, and education levels are also not correlated with IES-scores.

Non-specific psychological distress was also assessed in three studies. One study reported a prevalence rate of symptoms of psychological distress at 38% ( Moccia et al., 2020 ), while another study from Qiu et al. (2020) reported a prevalence of 34.43%. The study from Wang et al. (2020) did not explicitly state the prevalence rates, but the associated risk factors for higher psychological distress symptoms were reported (i.e., younger age groups and female gender are more likely to develop psychological distress) ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Other predictive factors included being migrant workers, profound regional severity of the outbreak, unmarried status, the history of visiting Wuhan in the past month, higher self-perceived impacts of the epidemic ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020 ). Interestingly, researchers have identified personality traits to be predictive of psychological distresses. For example, persons with negative coping styles, cyclothymic, depressive, and anxious temperaments exhibit greater susceptibility to psychological outcomes ( Wang et al., 2020 ; Moccia et al., 2020 ).

The intensity of overall stress was evaluated and reported in four studies. The prevalence of overall stress was variably reported between 8.1% to over 81.9% ( Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ). Females and the younger age group are often associated with higher stress levels as compared to males and the elderly. Other predictive factors of higher stress levels include student status, a higher number of lockdown days, unemployment, having to go out to work, having an acquaintance infected with the virus, presence of chronic illnesses, poor self-rated health, and presence of specific physical symptoms ( Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ).

3.8. A separate analysis of negative psychological outcomes

Out of the nineteen included studies, five studies appeared to be more representative of the general population based on the results of study quality appraisal ( Table 1 ). A separate analysis was conducted for a more generalizable conclusion. According to the results of these studies, the rates of negative psychological outcomes were moderate but higher than usual, with anxiety symptoms ranging from 6.33% to 18.7%, depressive symptoms ranging from 14.6% to 32.8%, stress symptoms being 27.2%, and symptoms of PTSD being approximately 7% ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Liu et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020b ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). In these studies, female gender, younger age group (≤40 years), and student population were repetitively reported to exhibit more adverse psychiatric symptoms.

3.9. Protective factors against symptoms of mental disorders

In addition to associated risk factors, a few studies also identified factors that protect individuals against symptoms of psychological illnesses during the pandemic. Timely dissemination of updated and accurate COVID-19 related health information from authorities was found to be associated with lower levels of anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms in the general public ( Wang et al., 2020a ). Additionally, actively carrying out precautionary measures that lower the risk of infection, such as frequent handwashing, mask-wearing, and less contact with people also predicted lower psychological distress levels during the pandemic ( Wang et al., 2020a ). Some personality traits were shown to correlate with positive psychological outcomes. Individuals with positive coping styles, secure and avoidant attachment styles usually presented fewer symptoms of anxiety and stress ( Wang et al., 2020 ; Moccia et al., 2020 ). ( Zhang et al. 2020 ) also found that participants with more social support and time to rest during the pandemic exhibited lower stress levels.

4. Discussion

Our review explored the mental health status of the general population and its predictive factors amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, there is a higher prevalence of symptoms of adverse psychiatric outcomes among the public when compared to the prevalence before the pandemic ( Huang et al., 2019 ; Lim et al., 2018 ). Variations in prevalence rates across studies were noticed, which could have resulted from various measurement scales, differential reporting patterns, and possibly international/cultural differences. For example, some studies reported any participants with scores above the cut-off point (mild-to-severe symptoms), while others only included participants with moderate-to-severe symptoms ( Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2020a ). Regional differences existed with respect to the general public's psychological health during a massive disease outbreak due to varying degrees of outbreak severity, national economy, government preparedness, availability of medical supplies/ facilities, and proper dissemination of COVID-related information. Additionally, the stage of the outbreak in each region also affected the psychological responses of the public. Symptoms of adverse psychological outcomes were more commonly seen at the beginning of the outbreak when individuals were challenged by mandatory quarantine, unexpected unemployment, and uncertainty associated with the outbreak ( Ho et al., 2020 ). When evaluating the psychological impacts incurred by the coronavirus outbreak, the duration of psychiatric symptoms should also be taken into consideration since acute psychological responses to stressful or traumatic events are sometimes protective and of evolutionary importance ( Yaribeygi et al., 2017 ; Brosschot et al., 2016 ; Gilbert, 2006 ). Being anxious and stressed about the outbreak mobilizes people and forces them to implement preventative measures to protect themselves. Follow-up studies after the pandemic may be needed to assess the long-term psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.1. Populations with greater susceptibility

Several predictive factors were identified from the studies. For example, females tended to be more vulnerable to develop the symptoms of various forms of mental disorders during the pandemic, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and stress, as reported in our included studies ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ). Greater psychological distress arose in women partially because they represent a higher percentage of the workforce that may be negatively affected by COVID-19, such as retail, service industry, and healthcare. In addition to the disproportionate effects that disruption in the employment sector has had on women, several lines of research also indicate that women exhibit differential neurobiological responses when exposed to stressors, perhaps providing the basis for the overall higher rate of select mental disorders in women ( Goel et al., 2014 ; Eid et al., 2019 ).

Individuals under 40 years old also exhibited more adverse psychological symptoms during the pandemic ( Ahmed et al., 2020 ; Gao et al., 2020 ; Huang and Zhao, 2020 ). This finding may in part be due to their caregiving role in families (i.e., especially women), who provide financial and emotional support to children or the elderly. Job loss and unpredictability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic among this age group could be particularly stressful. Also, a large proportion of individuals under 40 years old consists of students who may also experience more emotional distress due to school closures, cancelation of social events, lower study efficiency with remote online courses, and postponements of exams ( Cao et al., 2020 ). This is consistent with our findings that student status was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms and PTSD symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak ( Lei et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 , Wang et al., 2020a ; Samadarshi et al., 2020 ).

People with chronic diseases and a history of medical/ psychiatric illnesses showed more symptoms of anxiety and stress ( Mazza et al., 2020 ; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 ; Özdin and Özdin, 2020 ). The anxiety and distress of chronic disease sufferers towards the coronavirus infection partly stem from their compromised immunity caused by pre-existing conditions, which renders them susceptible to the infection and a higher risk of mortality, such as those with systemic lupus erythematosus ( Sawalha et al., 2020 ). Several reports also suggested that a substantially higher death rate was noted in patients with diabetes, hypertension and other coronary heart diseases, yet the exact causes remain unknown ( Guo et al., 2020 ; Emami et al., 2020 ), leaving those with these common chronic conditions in fear and uncertainty. Additionally, another practical aspect of concern for patients with pre-existing conditions would be postponement and inaccessibility to medical services and treatment as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, as a rapidly growing number of COVID-19 patients were utilizing hospital and medical resources, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of other diseases may have unintentionally been affected. Individuals with a history of mental disorders or current diagnoses of psychiatric illnesses are also generally more sensitive to external stressors, such as social isolation associated with the pandemic ( Ho et al., 2020 ).

4.2. COVID-19 related psychological stressors

Several studies identified frequent exposure to social media/news relating to COVID-19 as a cause of anxiety and stress symptoms ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, 2020 ). Frequent social media use exposes oneself to potential fake news/reports/disinformation and the possibility for amplified anxiety. With the unpredictable situation and a lot of unknowns about the novel coronavirus, misinformation and fake news are being easily spread via social media platforms ( Erku et al., 2020 ), creating unnecessary fears and anxiety. Sadness and anxious feelings could also arise when constantly seeing members of the community suffering from the pandemic via social media platforms or news reports ( Li et al., 2020 ).

Reports also suggested that poor economic status, lower education level, and unemployment are significant risk factors for developing symptoms of mental disorders, especially depressive symptoms during the pandemic period ( Gao et al., 2020 ; Lei et al., 2020 ; Mazza et al., 2020 ; Olagoke et al., 2020 ;). The coronavirus outbreak has led to strictly imposed stay-home-order and a decrease in demands for services and goods ( Nicola et al., 2020 ), which has adversely influenced local businesses and industries worldwide. Surges in unemployment rates were noted in many countries ( Statistics Canada, 2020 ; Statista, 2020 ). A decrease in quality of life and uncertainty as a result of financial hardship can put individuals into greater risks for developing adverse psychological symptoms ( Ng et al., 2013 ).

4.3. Efforts to reduce symptoms of mental disorders

4.3.1. policymaking.

The associated risk and protective factors shed light on policy enactment in an attempt to relieve the psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the general public. Firstly, more attention and assistance should be prioritized to the aforementioned vulnerable groups of the population, such as the female gender, people from age group ≤40, college students, and those suffering from chronic/psychiatric illnesses. Secondly, governments must ensure the proper and timely dissemination of COVID-19 related information. For example, validation of news/reports concerning the pandemic is essential to prevent panic from rumours and false information. Information about preventative measures should also be continuously updated by health authorities to reassure those who are afraid of being infected ( Tran, et al., 2020a ). Thirdly, easily accessible mental health services are critical during the period of prolonged quarantine, especially for those who are in urgent need of psychological support and individuals who reside in rural areas ( Tran et al., 2020b ). Since in-person health services are limited and delayed as a result of COVID-19 pandemic, remote mental health services can be delivered in the form of online consultation and hotlines ( Liu et al., 2020 ; Pisciotta et al., 2019 ). Last but not least, monetary support (e.g. beneficial funds, wage subsidy) and new employment opportunities could be provided to people who are experiencing financial hardship or loss of jobs owing to the pandemic. Government intervention in the form of financial provisions, housing support, access to psychiatric first aid, and encouragement at the individual level of healthy lifestyle behavior has been shown effective in alleviating suicide cases associated with economic recession ( McIntyre and Lee, 2020a ). For instance, declines in suicide incidence were observed to be associated with government expenses in Japan during the 2008 economic depression ( McIntyre and Lee, 2020a ).

4.3.2. Individual efforts

Individuals can also take initiatives to relieve their symptoms of psychological distress. For instance, exercising regularly and maintaining a healthy diet pattern have been demonstrated to effectively ease and prevent symptoms of depression or stress ( Carek et al., 2011 ; Molendijk et al., 2018 ; Lassale et al., 2019 ). With respect to pandemic-induced symptoms of anxiety, it is also recommended to distract oneself from checking COVID-19 related news to avoid potential false reports and contagious negativity. It is also essential to obtain COVID-19 related information from authorized news agencies and organizations and to seek medical advice only from properly trained healthcare professionals. Keeping in touch with friends and family by phone calls or video calls during quarantine can ease the distress from social isolation ( Hwang et al., 2020 ).

4.4. Strengths

Our paper is the first systematic review that examines and summarizes existing literature with relevance to the psychological health of the general population during the COVID-19 outbreak and highlights important associated risk factors to provide suggestions for addressing the mental health crisis amid the global pandemic.

4.5. Limitations

Certain limitations apply to this review. Firstly, the description of the study findings was qualitative and narrative. A more objective systematic review could not be conducted to examine the prevalence of each psychological outcome due to a high heterogeneity across studies in the assessment tools used and primary outcomes measured. Secondly, all included studies followed a cross-sectional study design and, as such, causal inferences could not be made. Additionally, all studies were conducted via online questionnaires independently by the study participants, which raises two concerns: 1] Individual responses in self-assessment vary in objectivity when supervision from a professional psychiatrist/ interviewer is absent, 2] People with poor internet accessibility were likely not included in the study, creating a selection bias in the population studied. Another concern is the over-representation of females in most studies. Selection bias and over-representation of particular groups indicate that most studies may not be representative of the true population. Importantly, studies in inclusion were conducted in a limited number of countries. Thus generalizations of mental health among the general population at a global level should be made cautiously.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review examined the psychological status of the general public during the COVID-19 pandemic and stressed the associated risk factors. A high prevalence of adverse psychiatric symptoms was reported in most studies. The COVID-19 pandemic represents an unprecedented threat to mental health in high, middle, and low-income countries. In addition to flattening the curve of viral transmission, priority needs to be given to the prevention of mental disorders (e.g. major depressive disorder, PTSD, as well as suicide). A combination of government policy that integrates viral risk mitigation with provisions to alleviate hazards to mental health is urgently needed.

Authorship contribution statement

JX contributed to the overall design, article selection , review, and manuscript preparation. LL and JX contributed to study quality appraisal. All other authors contributed to review, editing, and submission.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgements.

RSM has received research grant support from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research/Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases/National Natural Science Foundation of China and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Shire, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, and Minerva.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001 .

Appendix. Supplementary materials

- Ahmed M.Z., Ahmed O., Zhou A., Sang H., Liu S., Ahmad A. Epidemic of COVID-19 in China and associated psychological problems. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020; 51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102092. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anand K.B., Karade S., Sen S., Gupta R.M. SARS-CoV-2: camazotz's curse. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 2020; 76 :136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.04.008. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brosschot J.F., Verkuil B., Thayer J.F. The default response to uncertainty and the importance of perceived safety in anxiety and stress: an evolution-theoretical perspective. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016; 41 :22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.04.012. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cao W., Fang Z., Hou G., Han M., Xu X., Dong J., Zheng J. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 287 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carek P.J., Laibstain S.E., Carek S.M. Exercise for the treatment of depression and anxiety. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2011; 41 (1):15–28. doi: 10.2190/PM.41.1.c. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi K.W., Kim Y., Jeon H.J. Comorbid Anxiety and Depression: clinical and Conceptual Consideration and Transdiagnostic Treatment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020; 1191 :219–235. doi: 10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_14. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eid R.S., Gobinath A.R., Galea L.A.M. Sex differences in depression: insights from clinical and preclinical studies. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019; 176 :86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.01.006. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Emami A., Javanmardi F., Pirbonyeh N., Akbari A. Prevalence of Underlying Diseases in Hospitalized Patients. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020; 8 (1):e35. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v8i1.600.g748. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Epstein S., Roberts E., Sedgwick R., Finning K., Ford T., Dutta R., Downs J. Poor school attendance and exclusion: a systematic review protocol on educational risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviours. BMJ Open. 2018; 8 (12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023953. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Erku D.A., Belachew S.W., Abrha S., Sinnollareddy M., Thoma J., Steadman K.J., Tesfaye W.H. When fear and misinformation go viral: pharmacists' role in deterring medication misinformation during the 'infodemic' surrounding COVID-19. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.032. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gao J., Zheng P., Jia Y., Chen H., Mao Y., Chen S., Wang Y., Fu H., Dai J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15 (4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert P. Evolution and depression: issues and implications. Psycho. Med. 2006; 36 (3):287–297. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006112. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goel N., Workman J.L., Lee T.F., Innala L., Viau V. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr. Physiol. 2014; 4 (3):1121‐1155. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130054. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- González-Sanguino C., Ausín B., Castellanos M.A., Saiz J., López-Gómez A., Ugidos C., Muñoz M. Mental Health Consequences during the Initial Stage of the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo W., Li M., Dong Y., Zhou H., Zhang Z., Tian C., Qin R., Wang H., Shen Y., Du K., Zhao L., Fan H., Luo S., Hu D. Diabetes is a risk factor for the progression and prognosis of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3319. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hao F., Tan W., Jiang L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Jiang X., McIntyre R.S., Tran B., Sun J., Zhang Z., Ho R., Ho C., Tam W. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ho C.S.H., Chee C.Y., Ho R.C.M. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann. Acad. Med. Singapore. 2020; 49 (3):155–160. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang Y., et al. . Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiat. 2019; 6 (3):211–224. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang Y., Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hwang T., Rabheru K., Peisah C., Reichman W., Ikeda M. Loneliness and social isolation during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220000988. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lassale C., Batty G.D., Baghdadli A., Jacka F., Sánchez-Villegas A., Kivimäki M., Akbaraly T. Healthy dietary indices and risk of depressive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019; 24 :965–986. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0237-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lei L., Huang X., Zhang S., Yang J., Yang L., Xu M. Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the covid-19 epidemic in southwestern China. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020; 26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.924609. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li Z., et al. . Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav. Immum. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lim G.Y., Tam W.W., Lu Y., Ho C.S., Zhang M.W., Ho R.C. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 2018; 8 (1):2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu N., Zhang F., Wei C., Jia Y., Shang Z., Sun L., Wu L., Sun Z., Zhou Y., Wang Y., Liu W. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 287 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S., Yang L., Zhang C., Xiang Y., Liu Z., Hu S., Zhang B. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiat. 2020; 7 (4):e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mamun M.A., Ullah I. COVID-19 suicides in Pakistan, dying off not COVID-19 fear but poverty?—The forthcoming economic challenges for a developing country. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.028. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mazza C., Ricci E., Biondi S., Colasanti M., Ferracuti S., Napoli C., Roma P. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 :3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McIntyre R.S., Lee Y. Preventing suicide in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020; 19 (2):250–251. doi: 10.1002/wps.20767. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McIntyre R.S., Lee Y. Projected increases in suicide in Canada as a consequence of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113104. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moccia L., Janiri D., Pepe M., Dattoli L., Molinaro M., Martin V.D., Chieffo D., Janiri L., Fiorillo A., Sani G., Nicola M.D. Affective temperament, attachment style, and the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak: an early report on the Italian general population. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.048. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moghanibashi-Mansourieh A. Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020; 51 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010; 8 (5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Molendijk M., Molero P., Sánchez-Pandreño F.O., Van der Dose W., Martínez-González M.A. Diet quality and depression risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2018; 226 :346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.022. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng K.H., Agius M., Zaman R. The global economic crisis: effects on mental health and what can be done. J. R. Soc. Med. 2013; 106 :211–214. doi: 10.1177/0141076813481770. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicola M., Alsafi Z., Sohrabi C., Kerwan A., Al-Jabir A., Iosifidis C., Agha M., Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int. J. Surg. 2020; 78 :185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Olagoke A.A., Olagoke O.O., Hughes A.M. Exposure to coronavirus news on mainstream media: the role of risk perceptions and depression. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12427. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria N., Dosil-Santamaria M., Picaza-Gorrochategui M., Idoiaga-Mondragon N. Stress, anxiety and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain. Cad. Saude. Publica. 2020; 36 (4) doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00054020. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Özdin S., Özdin S.B. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pisciotta M., Denneson L.M., Williams H.B., Woods S., Tuepker A., Dobscha S.K. Providing mental health care in the context of online mental health notes: advice from patients and mental health clinicians. J. Ment. Health. 2019; 28 (1):64–70. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1521924. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatr. 2020; 33 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Samadarshi S.C.A., Sharma S., Bhatta J. An online survey of factors associated with self-perceived stress during the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in Nepal. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2020; 34 (2):1–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sawalha A.H., Zhao M., Coit P., Lu Q. Epigenetic dysregulation of ACE2 and interferon-regulated genes might suggest increased COVID-19 susceptibility and severity in lupus patients. J. Clin. Immunol. 2020; 215 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108410. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sønderskov K.M., Dinesen P.T., Santini Z.I., Østergaard S.D. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.15. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Statista, 2020. Monthly unemployment rate in the United States from May 2019 to May 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/273909/seasonally-adjusted-monthly-unemployment-rate-in-the-us/ (Accessed June 12 2020,).

- Statistic Canada, 2020. Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted and trend-cycle, last 5 months. https://doi.org/10.25318/1410028701-eng(Accessed June 12 2020,).

- Tan W., Hao F., McIntyre R.S., Jiang L., Jiang X., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., Hu Y., Luo X., Zhang Z., Lai A., Ho R., Tran B., Ho C., Tam W. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.055. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thakur V., Jain A. COVID 2019-Suicides: a global psychological pandemic. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.062. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ] Retracted

- Tran B.X., et al. Coverage of Health Information by Different Sources in Communities: implication for COVID-19 Epidemic Response. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 (10):3577. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103577. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tran B.X., Phan H.T., Nguyen T.P.T., Hoang M.T., Vu G.T., Lei H.T., Latkin C.A., Ho C.S.H., Ho R.C.M. Reaching further by Village Health Collaborators: the informal health taskforce of Vietnam for COVID-19 responses. J. Glob. Health. 2020; 10 (1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010354. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C.S., Ho R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 (5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., McIntyre R.S., Choo F.N., Tran B., Ho R., Sharma V.K., Ho C. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang H., Xia Q., Xiong Z., Li Z., Xiang W., Yuan Y., Liu Y., Li Z. The psychological distress and coping styles in the early stages of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic in the general mainland Chinese population: a web-based survey. PLoS ONE. 2020; 15 (5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233410. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y., Di Y., Ye J., Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol. Health Med. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yaribeygi H., Panahi Y., Sahraei H., Johnston T.P., Sahebkar A. The impact of stress on body function: a review. EXCLI J. 2017; 16 :1057–1072. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-480. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Y., Ma Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17 (7):2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072381. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Downloadable Content

A Study on Students' Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic Through the Perspective of Mental Health Professionals

- Masters Thesis

- Hightower, Shelby

- Navarro, Richard

- Olson, Peter

- Lim, Andrew

- Education & Integrative Studies

- California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

- pandemic lockdown 2020

- mental health

- http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12680/9306t488f

Relationships

- CPP Education

Items in ScholarWorks are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 10, Issue 12

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and well-being of communities: an exploratory qualitative study protocol

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0180-0213 Anam Shahil Feroz 1 , 2 ,

- Naureen Akber Ali 3 ,

- Noshaba Akber Ali 1 ,

- Ridah Feroz 4 ,

- Salima Nazim Meghani 1 ,

- Sarah Saleem 1

- 1 Community Health Sciences , Aga Khan University , Karachi , Pakistan

- 2 Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation , University of Toronto , Toronto , Ontario , Canada

- 3 School of Nursing and Midwifery , Aga Khan University , Karachi , Pakistan

- 4 Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development , Karachi , Pakistan

- Correspondence to Ms Anam Shahil Feroz; anam.sahyl{at}gmail.com

Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly resulted in an increased level of anxiety and fear in communities in terms of disease management and infection spread. Due to fear and social stigma linked with COVID-19, many individuals in the community hide their disease and do not access healthcare facilities in a timely manner. In addition, with the widespread use of social media, rumours, myths and inaccurate information about the virus are spreading rapidly, leading to intensified irritability, fearfulness, insomnia, oppositional behaviours and somatic complaints. Considering the relevance of all these factors, we aim to explore the perceptions and attitudes of community members towards COVID-19 and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

Methods and analysis This formative research will employ an exploratory qualitative research design using semistructured interviews and a purposive sampling approach. The data collection methods for this formative research will include indepth interviews with community members. The study will be conducted in the Karimabad Federal B Area and in the Garden (East and West) community settings in Karachi, Pakistan. The community members of these areas have been selected purposively for the interview. Study data will be analysed thematically using NVivo V.12 Plus software.

Ethics and dissemination Ethical approval for this study has been obtained from the Aga Khan University Ethical Review Committee (2020-4825-10599). The results of the study will be disseminated to the scientific community and to the research subjects participating in the study. The findings will help us explore the perceptions and attitudes of different community members towards the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

- mental health

- public health

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041641

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to last much longer than the physical health impact, and this study is positioned well to explore the perceptions and attitudes of community members towards the pandemic and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

This study will guide the development of context-specific innovative mental health programmes to support communities in the future.

One limitation is that to minimise the risk of infection all study respondents will be interviewed online over Zoom and hence the authors will not have the opportunity to build rapport with the respondents or obtain non-verbal cues during interviews.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected almost 180 countries since it was first detected in Wuhan, China in December 2019. 1 2 The COVID-19 outbreak has been declared a public health emergency of international concern by the WHO. 3 The WHO estimates the global mortality to be about 3.4% 4 ; however, death rates vary between countries and across age groups. 5 In Pakistan, a total of 10 880 cases and 228 deaths due to COVID-19 infection have been reported to date. 6

The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has not only incurred massive challenges to the global supply chains and healthcare systems but also has a detrimental effect on the overall health of individuals. 7 The pandemic has led to lockdowns and has created destructive impact on the societies at large. Most company employees, including daily wage workers, have been prohibited from going to their workplaces or have been asked to work from home, which has caused job-related insecurities and financial crises in the communities. 8 Educational institutions and training centres have also been closed, which resulted in children losing their routine of going to schools, studying and socialising with their peers. Delay in examinations is likewise a huge stressor for students. 8 Alongside this, parents have been struggling with creating a structured milieu for their children. 9 COVID-19 has hindered the normal routine life of every individual, be it children, teenagers, adults or the elderly. The crisis is engendering burden throughout populations and communities, particularly in developing countries such as Pakistan which face major challenges due to fragile healthcare systems and poor economic structures. 10

The COVID-19 pandemic has certainly resulted in an increased level of anxiety and fear in communities in terms of disease management and infection spread. 8 Further, the highly contagious nature of COVID-19 has also escalated confusion, fear and panic among community residents. Moreover, social distancing is often an unpleasant experience for community members and for patients as it adds to mental suffering, particularly in the local setting where get-togethers with friends and families are a major source of entertainment. 9 Recent studies also showed that individuals who are following social distancing rules experience loneliness, causing a substantial level of distress in the form of anxiety, stress, anger, misperception and post-traumatic stress symptoms. 8 11 Separation from family members, loss of autonomy, insecurity over disease status, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, frustration, stigma and boredom are all major stressors that can create drastic impact on an individual’s life. 11 Due to fear and social stigma linked with COVID-19, many individuals in the community hide their disease and do not access healthcare facilities in a timely manner. 12 With the widespread use of social media, 13 rumours, myths and inaccurate information about COVID-19 are also spreading rapidly, not only among adults but are also carried on to children, leading to intensified irritability, fearfulness, insomnia, oppositional behaviours and somatic complaints. 9 The psychological symptoms associated with COVID-19 at the community level are also manifested as anxiety-driven panic buying, resulting in exhaustion of resources from the market. 14 Some level of panic also dwells in the community due to the unavailability of essential protective equipment, particularly masks and sanitisers. 15 Similarly, mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, panic attacks, psychotic symptoms and even suicide, were reported during the early severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. 16 17 COVID-19 is likely posing a similar risk throughout the world. 12

The fear of transmitting the disease or a family member falling ill is a probable mental function of human nature, but at some point the psychological fear of the disease generates more anxiety than the disease itself. Therefore, mental health problems are likely to increase among community residents during an epidemic situation. Considering the relevance of all these factors, we aim to explore the perceptions and attitudes towards COVID-19 among community residents and the impact of these perceptions and attitude on their daily lives and mental well-being.

Methods and analysis

Study design.

This study will employ an exploratory qualitative research design using semistructured interviews and a purposive sampling approach. The data collection methods for this formative research will include indepth interviews (IDIs) with community members. The IDIs aim to explore perceptions of community members towards COVID-19 and its impact on their mental well-being.

Study setting and study participants

The study will be conducted in two communities in Karachi City: Karimabad Federal B Area Block 3 Gulberg Town, and Garden East and Garden West. Karimabad is a neighbourhood in the Karachi Central District of Karachi, Pakistan, situated in the south of Gulberg Town bordering Liaquatabad, Gharibabad and Federal B Area. The population of this neighbourhood is predominantly Ismailis. People living here belong mostly to the middle class to the lower middle class. It is also known for its wholesale market of sports goods and stationery. Garden is an upmarket neighbourhood in the Karachi South District of Karachi, Pakistan, subdivided into two neighbourhoods: Garden East and Garden West. It is the residential area around the Karachi Zoological Gardens; hence, it is popularly known as the ‘Garden’ area. The population of Garden used to be primarily Ismailis and Goan Catholics but has seen an increasing number of Memons, Pashtuns and Baloch. These areas have been selected purposively because the few members of these communities are already known to one of the coinvestigators. The coinvestigator will serve as a gatekeeper for providing entrance to the community for the purpose of this study. Adult community members of different ages and both genders will be interviewed from both sites, as mentioned in table 1 . Interview participants will be selected following the eligibility criteria.

- View inline

Study participants for indepth interviews

IDIs with community members

We will conduct IDIs with community members to explore the perceptions and attitudes of community members towards COVID-19 and its effects on their daily lives and mental well-being. IDI participants will be identified via the community WhatsApp group, and will be invited for an interview via a WhatsApp message or email. Consent will be taken over email or WhatsApp before the interview begins, where they will agree that the interview can be audio-recorded and that written notes can be taken. The interviews will be conducted either in Urdu or in English language, and each interview will last around 40–50 min. Study participants will be assured that their information will remain confidential and that no identifying features will be mentioned on the transcript. The major themes will include a general discussion about participants’ knowledge and perceptions about the COVID-19 pandemic, perceptions on safety measures, and perceived challenges in the current situation and its impact on their mental well-being. We anticipate that 24–30 interviews will be conducted, but we will cease interviews once data saturation has been achieved. Data saturation is the point when no new themes emerge from the additional interviews. Data collection will occur concurrently with data analysis to determine data saturation point. The audio recordings will be transcribed by a transcriptionist within 24 hours of the interviews.

An interview guide for IDIs is shown in online supplemental annex 1 .

Supplemental material

Eligibility criteria.

The following are the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of study participants:

Inclusion criteria

Residents of Garden (East and West) and Karimabad Federal B Area of Karachi who have not contracted the disease.

Exclusion criteria

Those who refuse to participate in the study.

Those who have experienced COVID-19 and are undergoing treatment.

Those who are suspected for COVID-19 and have been isolated/quarantined.

Family members of COVID-19-positive cases.

Data collection procedure

A semistructured interview guide has been developed for community members. The initial questions on the guide will help to explore participants’ perceptions and attitudes towards COVID-19. Additional questions on the guide will assess the impact of these perceptions and attitude on the daily lives and mental health and well-being of community residents. All semistructured interviews will be conducted online via Zoom or WhatsApp. Interviews will be scheduled at the participant’s convenient day and time. Interviews are anticipated to begin on 1 December 2020.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved.

Data analysis

We will transcribe and translate collected data into English language by listening to the audio recordings in order to conduct a thematic analysis. NVivo V.12 Plus software will be used to import, organise and explore data for analysis. Two independent researchers will read the transcripts at various times to develop familiarity and clarification with the data. We will employ an iterative process which will help us to label data and generate new categories to identify emergent themes. The recorded text will be divided into shortened units and labelled as a ‘code’ without losing the main essence of the research study. Subsequently, codes will be analysed and merged into comparable categories. Lastly, the same categories will be grouped into subthemes and final themes. To ensure inter-rater reliability, two independent investigators will perform the coding, category creation and thematic analyses. Discrepancies between the two investigators will be resolved through consensus meetings to reduce researcher bias.

Ethics and dissemination

Study participants will be asked to provide informed, written consent prior to participation in the study. The informed consent form can be submitted by the participant via WhatsApp or email. Participants who are unable to write their names will be asked to provide a thumbprint to symbolise their consent to participate. Ethical approval for this study has been obtained from the Aga Khan University Ethical Review Committee (2020-4825-10599). The study results will be disseminated to the scientific community and to the research subjects participating in the study. The findings will help us explore the perceptions and attitudes of different community members towards the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on their daily lives and mental well-being.

The findings of this study will help us to explore the perceptions and attitudes towards the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the daily lives and mental well-being of individuals in the community. Besides, an indepth understanding of the needs of the community will be identified, which will help us develop context-specific innovative mental health programmes to support communities in the future. The study will provide insights into how communities are managing their lives under such a difficult situation.

- World Health Organization

- Nielsen-Saines K , et al

- Worldometer

- Ebrahim SH ,

- Gozzer E , et al

- Snoswell CL ,

- Harding LE , et al

- Nargis Asad

- van Weel C ,

- Qidwai W , et al

- Brooks SK ,

- Webster RK ,

- Smith LE , et al

- Tripathy S ,

- Kar SK , et al

- Schwartz J ,

- Maunder R ,

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

ASF and NAA are joint first authors.

Contributors ASF and NAA conceived the study. ASF, NAA, RF, NA, SNM and SS contributed to the development of the study design and final protocols for sample selection and interviews. ASF and NAA contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 July 2021

Public mental health problems during COVID-19 pandemic: a large-scale meta-analysis of the evidence

- Xuerong Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9236-5773 1 ,

- Mengyin Zhu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5561-9570 1 ,

- Rong Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4516-4116 2 ,

- Jingxuan Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8979-5107 1 ,

- Chenyan Zhang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2945-6584 3 ,

- Peiwei Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2660-1106 4 ,

- Zhengzhi Feng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6144-5044 1 &

- Zhiyi Chen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1744-4647 1 , 2

Translational Psychiatry volume 11 , Article number: 384 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

99 Citations

46 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Psychiatric disorders

- Scientific community

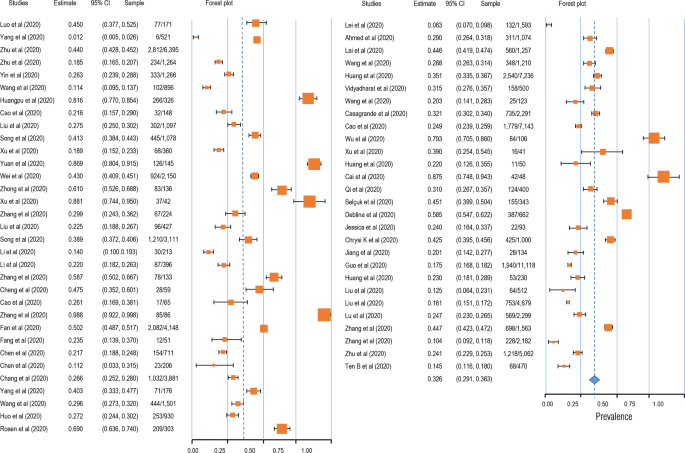

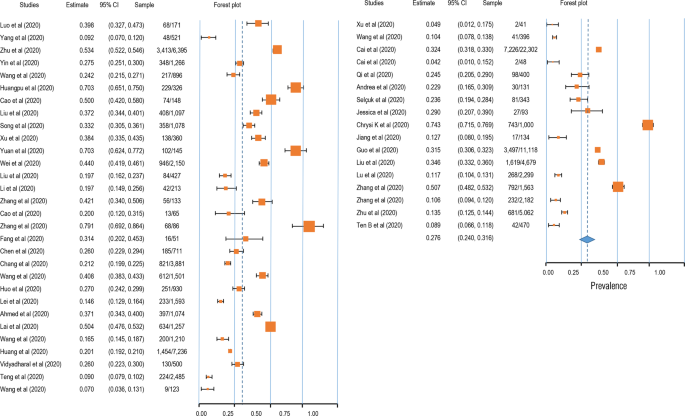

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exposed humans to the highest physical and mental risks. Thus, it is becoming a priority to probe the mental health problems experienced during the pandemic in different populations. We performed a meta-analysis to clarify the prevalence of postpandemic mental health problems. Seventy-one published papers ( n = 146,139) from China, the United States, Japan, India, and Turkey were eligible to be included in the data pool. These papers reported results for Chinese, Japanese, Italian, American, Turkish, Indian, Spanish, Greek, and Singaporean populations. The results demonstrated a total prevalence of anxiety symptoms of 32.60% (95% confidence interval (CI): 29.10–36.30) during the COVID-19 pandemic. For depression, a prevalence of 27.60% (95% CI: 24.00–31.60) was found. Further, insomnia was found to have a prevalence of 30.30% (95% CI: 24.60–36.60). Of the total study population, 16.70% (95% CI: 8.90–29.20) experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Subgroup analysis revealed the highest prevalence of anxiety (63.90%) and depression (55.40%) in confirmed and suspected patients compared with other cohorts. Notably, the prevalence of each symptom in other countries was higher than that in China. Finally, the prevalence of each mental problem differed depending on the measurement tools used. In conclusion, this study revealed the prevalence of mental problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by using a fairly large-scale sample and further clarified that the heterogeneous results for these mental health problems may be due to the nonstandardized use of psychometric tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: a meta-analysis and systematic review

Mental disorders following COVID-19 and other epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction.

Since the end of 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has continued to spread worldwide. Researchers rapidly identified the cause of COVID-19 to be the transmission of serious acute respiratory syndrome by a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [ 1 ]. Unfortunately, due to the lack of effective cures and vaccines, the ability of public medical systems to guard against COVID-19 is deteriorating rapidly. Although approved vaccines are now available, their safety is still a concern [ 2 , 3 ]. Further, because of reports regarding the potential to be reinfected with COVID-19, public panic is still spreading even though COVID-19 transmission has been contained substantially [ 4 ]. To date, projections regarding the end of the COVID-19 pandemic around the world are still far from optimistic. There were more than 158.95 million confirmed cases and 3.30 million deaths by May 11, 2021 (supported by Johns Hopkins University), a situation that has led to unprecedented losses and stress.

COVID-19 not only threatens physical health but has also led to mental health sequelae (i.e., loss of family, job loss, social constraints and uncertainty, and fear about the future) [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. In general, mental health problems, including depression and anxiety, have had major negative impacts on the public during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 8 , 9 ]. Previous studies showed that mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suddenly increased after the COVID-19 outbreak: 53.8% of respondents rated the psychological impact of the outbreak as moderate or severe; 16.5% of participants reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms; 28.8% of participants reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms; and 24.5% of participants showed psychological stress [ 10 ]. Moreover, such mental health problems were worse in confirmed patients and healthcare workers. As a typical example, one early study revealed acute anxiety symptoms in 98.84% of confirmed patients and depression symptoms in 79.07% of confirmed cases [ 11 ]. In addition, an early investigation concerning the mental health status of 400 public health workers found that 31% of public health workers had anxiety symptoms, and 24.5% of them had depressive symptoms [ 12 ]. In this vein, it seems that the mental health sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic warrant more attention. In addition, with the development of the epidemic situation, long-term isolation due to the increasing number of confirmed and suspected patients has caused losses to life and property, which has not only caused considerable psychological stress in the population but has also had physiological effects, such as insomnia and PTSD.

In brief, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed public health to dramatic risks and resulted in unacceptable mental and physiological stresses. Despite considerable research, two critical concerns regarding mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic remain. One concern in previous studies is that the conclusions regarding the prevalence of these mental health problems are highly heterogeneous, irrespective of whether they are derived from original investigations or meta-analyses [ 13 , 14 ]. Another is that early investigations were almost all done during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and thus may overestimate the scale of mental health problems. Thus, the main purpose of this study is to provide comprehensive statistical results regarding the impact of COVID-19 on individual mental health through a large-scale meta-analysis of the existing research in this field and to provide an evidence-based reference for the prevention and control of psychological crises during this pandemic. It is noteworthy that this study employs a larger data pool than any of the existing meta-analyses to date. Further, much effort has been made to perform an in-depth investigation of the patterns of mental health problems triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, including population-, region-, and measurement-specific patterns.

Materials and methods

To improve reproducibility and standardization, all the pipelines and protocols were in line with the Cochrane Handbook and were double-checked by using the PRISMA checklist [ 15 ]. This meta-analysis has been preregistered on OSF for open access ( https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/A5VMK ).

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic search was conducted for studies published from January 1, 2020 to July 1, 2020 (the period from the commencement of the outbreak to its initial control in China) in PubMed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, EBSCO, Web of Science, CNKI (Chinese database), WANGFANG DATA, the Chinese Biomedical Literature Service System, and public information release platforms (WeChat Subscription or microblogs). According to the indices of the various databases, keywords, including “2019 novel coronavirus,” “COVID-19,” “novel coronavirus pneumonia,” “NPC,” “2019-nCoV,” “mental health,” “anxiety,” “depression,” “psychological health,” “sleep,” “insomnia,” “Posttraumatic stress disorder,” and “PTSD,” were adopted to retrieve published surveys of psychological status during the COVID-19 epidemic from January 1, 2020 to July 1, 2020. In addition to identifying any target studies that may have been missed, we checked the reference list of each selected paper. The population was divided into three categories according to the probable psychological stress intensity experienced: public health workers, confirmed patients, and the general population (see Fig. 1 , Supplemental information, and Table S1 ).

This flowchart is coincide with the broad-certified 2020 PRISMAstatement. Small sample size was predefined as < 30 participants.

Data extraction and quality assessment