Abortion in the US: What you need to know

Subscribe to the center for economic security and opportunity newsletter, isabel v. sawhill and isabel v. sawhill senior fellow emeritus - economic studies , center for economic security and opportunity @isawhill kai smith kai smith research assistant - the brookings institution, economic studies.

May 29, 2024

Key takeaways:

One in every four women will have an abortion in their lifetime.

- The vast majority of abortions (about 95%) are the result of unintended pregnancies.

- Most abortion patients are in their twenties (61%), Black or Latino (59%), low-income (72%), unmarried (86%), between six and twelve weeks pregnant (73%), and already have given birth to one or more children (55%).

- Despite state bans, U.S. abortion totals increased in the first full year after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Introduction

Two years after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, abortion remains one of the most hotly contested issues in American politics. The abortion landscape has become highly fractured, with some states implementing abortion bans and restrictions and others increasing protections and access. The Supreme Court heard two more cases on abortion this term and will likely release those decisions in June. Beyond the Supreme Court, pro-choice and pro-life advocates are fiercely battling it out in the voting booths, state legislatures, and courts. If the 2022 midterm elections are any indication , abortion will be one of the most influential issues of the 2024 election. So what are the basic facts about abortion in America? This primer is designed to tell you most of what you need to know.

What are the different types of abortion?

There are two main types of abortion: procedural abortions and medication abortions. Procedural abortions (also called in-clinic or surgical abortions) are provided by health care professionals in a clinical setting. Medication abortions (also called medical abortions or the abortion pill) typically involve the oral ingestion of two drugs in succession, mifepristone and misoprostol.

Most women discover they are pregnant in the first five to six weeks of pregnancy, but about a third of women do not learn they are pregnant until they are beyond six weeks of gestation. 1 Women with unintended pregnancies detect their pregnancies later than women with intended pregnancies, between six and seven weeks of gestation on average. Even if a woman discovers she is pregnant relatively early, for many it takes time to decide what to do and how to arrange for an abortion if that is her preference.

Why do women have abortions?

The vast majority of abortions (about 95%) are the result of unintended pregnancies. That includes pregnancies that are mistimed as well as those that are unwanted.

Women’s reasons for not wanting a child—or not wanting one now—include finances, partner-related issues, the need to focus on other children, and interference with future education or work opportunities.

In short, if there were fewer unintended pregnancies, there would be fewer abortions.

How common are abortions?

About two in every five pregnancies are unintended (40% in 2015). Roughly the same share of these unintended pregnancies end in abortion (42% in 2011). About one in every five pregnancies are aborted (21% in 2020).

How have abortion totals changed over time?

The number of abortions occurring in the U.S. jumped up after the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973. After peaking in 1990, the number of abortions declined steadily for two and a half decades until reaching its lowest point since 1973 in 2017. 2 Possible contributing factors explaining this long-term decline include delays in sexual activity amongst young people, improvements in the use of effective contraception , and overall declines in pregnancy rates , including those that are unintended . In addition, state restrictions which became more prevalent beginning in 2011 prevented at least some individuals in certain states from having abortions.

In 2018 (four years before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade), the number of abortions in the U.S. began to increase. The causes of this uptick are not yet fully understood, but researchers have identified multiple potential contributing factors. These include greater coverage of abortions under Medicaid that made abortions more affordable in certain states, regulations issued by the Trump administration in 2019 which decreased the size of the Title X network and therefore reduced the availability of contraception to low-income individuals, and increased financial support from privately-financed abortion funds to help pay for the costs associated with getting an abortion.

Another contributing factor, whose importance bears emphasizing, is the surging popularity of medication abortions .

The use of medication abortions has increased steadily since becoming available in the U.S. in 2000. However, in 2016, the FDA increased the gestational limit for the use of mifepristone from seven to ten weeks and thereby doubled the share of abortion patients eligible for medication abortions from 37% to 75%.

Later, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the FDA revised its policy in 2021 so that clinicians are no longer required to dispense medication abortion pills in person. Patients can now have medication abortion pills mailed to their homes after conducting remote consultations with clinicians via telehealth. In January 2023, the FDA issued another change which allows retail pharmacies like CVS and Walgreens to dispense medication abortion pills to patients with a prescription. Previously only doctors, clinics, or some mail-order pharmacies could dispense abortion pills.

Although access varies widely by state , medication abortions are now the most commonly used abortion method in the U.S. and account for nearly two-thirds of all abortions (63% in 2023). 3

This is why the Supreme Court’s upcoming decision in the Mifepristone case (FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine) is so consequential. Among other issues, at stake is whether access to medication abortion will be sharply curtailed and whether regulations regarding medication abortions will revert to pre-2016 rules when abortion pills were not authorized for use after seven weeks of pregnancy and could not be prescribed via telemedicine, sent to abortion patients by mail, or dispensed by retail pharmacies.

Who has abortions?

Most abortion patients are in their twenties (61%), Black or Latino (59%), low-income (72%), unmarried (86%), and between six and twelve weeks pregnant (73%). 4

The majority of abortion patients have already given birth to one or more children (55%) and have not previously had an abortion (57%). 5 Among abortion patients twenty years old or older, most had attended at least some college (63%). The vast majority of abortions occur during the first trimester of pregnancy (91%). So-called “late-term abortions” performed at or after 21 weeks of pregnancy are very rare and represent less than 1% of all abortions in the U.S.

The abortion rate per 1,000 women of reproductive age is disproportionately high for certain population groups. Among women living in poverty, for example, the abortion rate was 36.6 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age in 2014, compared to 14.6 abortions per 1,000 women among all women of reproductive age.

How much does an abortion cost?

The cost of an abortion varies depending on what kind of abortion is administered, how far along the patient is in their pregnancy, where the patient lives, where the patient is seeking an abortion, and whether health insurance or financial assistance is available. In 2021, the median self-pay cost for abortion services was $625 for a procedural abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy and $568 for a medication abortion.

Since 1977, the Hyde Amendment has banned the use of federal funds to pay for abortions except in cases of rape, incest, or life endangerment. Today, among the 36 states that have not banned abortion, fewer than half (17 as of March 2024) allow the use of state Medicaid funds to pay for abortions. 6 Many insurance plans do not cover abortions, often due to state limitations. Most abortion patients pay for abortions out of pocket (53%). State Medicaid funding is the second-most-commonly used method of payment (30%), followed by financial assistance (15%) and private insurance (13%). 7

Whether state law allows state Medicaid funds to cover abortions has a very large impact on the difficulty of paying for abortions and the methods used by women to pay for them. In the year before the Dobbs Supreme Court decision, 50% of women residing in states where state Medicaid funds did not cover abortion reported it was very or somewhat difficult to pay for their abortions, compared to only 17% of women residing in states where abortions were covered.

How has the Supreme Court handled abortion?

In Roe v. Wade (1973), the Supreme Court established that states could not ban abortions before fetal viability, the point at which a fetus can survive outside the womb. Under the three-trimester framework established by Roe, states were not allowed to ban abortions during the first two trimesters of pregnancy but were allowed to regulate or prohibit abortions in the third trimester, except in cases where abortions were necessary to protect the life or health of a pregnant person. The Court ruled that the fundamental right to have an abortion is included in the right to privacy implicit in the “liberty” guarantee of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Since it was decided, Roe v. Wade has faced legal criticism. Notwithstanding these critiques, the Court upheld Roe multiple times over the next half-century including in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). But after former President Trump appointed three new Justices to the Supreme Court, a new conservative supermajority overturned Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) and established that there is no Constitutional right to have an abortion.

In his Dobbs majority opinion , Justice Alito concluded “Roe was egregiously wrong from the start.” Writing for the majority, he underscored that “[t]he Constitution makes no reference to abortion,” and while he recognized there are constitutional rights not expressly enumerated in the Constitution, he concluded the right to have an abortion is not one of them. Justice Alito reasoned that the only legitimate rights not explicitly stated in the Constitution are those “deeply rooted in the nation’s history and traditions,” and he found no evidence of this for abortion.

Because the Court determined there is no Constitutional right to abortion, it allowed the Mississippi state law which banned abortion after 15 weeks of pregnancy with limited exceptions to go into effect. The Court ruled that states have the authority to restrict access to abortion or ban it completely and that the power to regulate or prohibit abortions would be “returned to the people and their elected representatives.”

The Court’s three liberal Justices criticized the majority’s decision in a withering joint dissent . The dissenting Justices argued the right to abortion established in Roe and upheld in Casey is necessary to respect the autonomy and equality of women and prevent the government from controlling “a woman’s body or the course of a woman’s life.” They lamented “one result of today’s decision is certain: the curtailment of women’s rights, and of their status as free and equal citizens.”

How did the states respond to the overturning of Roe v. Wade?

Since Roe v. Wade was overturned, many states have implemented abortion bans or restrictions, while others have added protections and expanded access. The abortion landscape in America is now fractured and highly variegated .

As of May 2024, abortion is banned completely in almost all circumstances in 14 states. In 7 states, abortion is banned at or before 18 weeks of gestation. Many states with abortion bans do not include exceptions in cases where the health of the pregnant person is at risk, the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, or there is a fatal fetal anomaly.

Access to abortion varies widely even among states without bans since many states have restrictions such as waiting periods, gestational limits, or parental consent laws making it more difficult to get an abortion.

Many state bans and restrictions are still being litigated in court. The interjurisdictional issues and legal questions arising from the post-Dobbs abortion landscape have not been fully resolved.

Despite the Supreme Court’s stated intention in Dobbs to leave the abortion issue to elected officials, the Court will likely hear more cases on abortion in the near future. This term, in addition to the case about Mifepristone, the Court will decide in Moyle v. United States whether a federal law called the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTLA) can require hospitals in states with abortion bans to perform abortions in emergency situations that demand “stabilizing treatment” for the health of pregnant patients.

What are the trends in abortion statistics post-Dobbs?

In 2023, the first full year since the Dobbs Supreme Court decision, states with abortion bans experienced sharp declines in the number of abortions occurring within their borders. But these declines were outweighed by increases in abortion totals in states where abortion remained legal. Nearly all states without bans witnessed increases in 2023. Taken together, abortions in non-ban states increased by 26% in 2023 compared to 2020 levels.

As a result, the nationwide abortion statistics from 2023 represent the highest total number (1,037,000 abortions) and abortion rate (15.9 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age) in the U.S. in over a decade. The 2023 U.S. total represents an 11% increase from 2020 levels.

It’s unclear why, despite Dobbs, abortions have continued to rise . It may be because of the increased use of medication abortions , especially after the FDA liberalized regulations related to telehealth and in-person visits. In addition, multiple states where abortion remains legal have implemented shield laws and other new protections for abortion patients and providers, increased insurance coverage, or otherwise expanded access . Abortion funds provided greater financial and practical assistance . Interstate travel for abortions doubled after the Dobbs decision.

In short, the impacts of Dobbs are being felt unevenly. Although most women who want abortions are still able to obtain them, a significant minority are instead carrying their pregnancies to term. In the first six months of 2023, state abortion bans led between one-fifth and one-fourth of women living in ban states who may have otherwise gotten an abortion not to have one.

Young, low-income, and minority women will be most affected by state bans and restrictions because they are disproportionately likely to have unintended pregnancies and less able to overcome economic and logistical barriers involved in travelling across state lines or receiving medication abortion pills through out-of-state networks.

What are the effects of expanding or restricting abortion access on women and their families?

Effects of abortion restrictions on women.

Abortion bans jeopardize the lives and health of women. The impacts on their health can be especially troublesome. Pregnancies can go wrong for many reasons—fetal abnormalities, complications of a miscarriage, ectopic pregnancies—and without access to emergency care, some women could face serious threats to their own health and future ability to bear children. Abortion restrictions can place doctors in difficult situations and undermine women’s health care.

Although medication abortions are safe and effective, abortion bans could also increase the number of women who use unsafe methods to induce self-managed abortions, thereby endangering their own health or even their lives. State abortion legalizations in the years before Roe reduced maternal mortality among non-white women by 30-40%.

Enforcement of state laws that restricted access to abortion in the years before Dobbs has even been associated with increases in intimate partner violence-related homicides of women and girls.

In addition, lack of access to abortion leads to worse economic outcomes for women. After a conservative group suggested that such effects have not been well documented, a group of economists filed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court in the Dobbs case, noting that in recent years methods for establishing the causal effects of abortion have shown that they do affect women’s life trajectories. Although there has been some difficulty in separating the effects of access to abortion from access to the Pill or other forms of birth control, an extensive literature shows that reducing unintended pregnancies increases educational attainment , labor force participation , earnings , and occupational prestige for women. These trends are especially pronounced for Black women .

One example that focuses solely on abortion is the Turnaway study, in which researchers compared the outcomes for women who were denied abortions on the basis of just being a little beyond the gestational cutoff for eligibility to the outcomes of otherwise similar women who were just under that cutoff. The study along with subsequent related research has shown that women who are denied abortions are nearly four times more likely to be living in poverty six months after being denied an abortion, a difference that persists through four years after denial. They are also more likely to be unemployed , rely on public assistance , and experience financial distress such as bankruptcies, evictions and court judgements.

Finally, increased access to abortion results in lower rates of single and teen parenthood. State abortion legalizations in the years before Roe reduced the number of teen mothers by 34%. The effects were especially large for Black teens.

Effects of abortion restrictions on children

Along with contraception, access to abortion reduces unplanned births. That means fewer children dying in infancy, growing up in poverty, needing welfare, and living with a single parent. One study suggests that if all currently mistimed births were aligned with the timing preferred by their mothers, children’s college graduation rates would increase by about 8 percentage points (a 36% increase), and their lifetime incomes would increase by roughly $52,000.

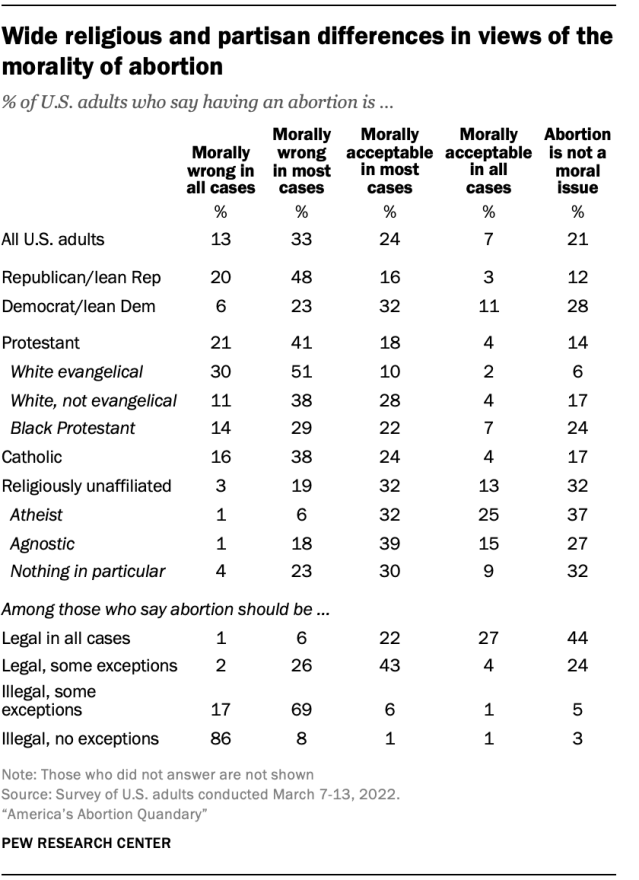

Despite this evidence that the denial of abortions to women who want them would be harmful to women and to children once born, those who are pro-life argue that these costs are well worth the price to save the lives of the unborn. As of April 2024, 36% of Americans believe abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases, while 63% of Americans believe abortion should be legal in all (25%) or most (28%) cases.

Looking ahead

The abortion landscape in America is continually evolving. Whereas pro-choice advocates will seek to expand access and add additional protections for abortion patients and providers, opponents of abortion will continue to criminalize abortions and further restrict availability.

Abortion will be one of the top issues of the 2024 elections in November. Democratic candidates in particular believe abortion is a winning issue for them and will broadcast their pro-choice stance on the campaign trail. Some evidence suggests the overturning of Roe has galvanized a new class of abortion-rights voters. Multiple states will have abortion referenda on the ballot .

The Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision will not prevent women and other citizens from affecting the legislative process by voting, organizing, influencing public opinion, or running for office. What they do with that power in November remains to be seen.

Related Content

Isabel V. Sawhill, Morgan Welch

June 30, 2022

Isabel V. Sawhill

November 3, 2020

Katherine Guyot, Isabel V. Sawhill

July 29, 2019

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here . The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

- We recognize people of all genders become pregnant and have abortions, including about 1% of abortion patients who do not identify as women or female. For concision, we use “women” and female pronouns in this piece when discussing individuals who become pregnant.

- The Guttmacher and CDC data produced in this primer only represent legal abortions that occur within the formal US healthcare system. They do not include self-managed which occur outside of the formal US healthcare system.

- As of March 2024, 29 states have laws that restrict access to medication abortion, for example by requiring ultrasound, counseling, or multiple in-person appointments.

- We define low-income as earnings below 200% of the federal poverty level.

- The CDC abortion data is less complete than the Guttmacher Institute data and omits abortion data from states which account for approximately one-fourth of all abortions in the U.S.

- Today, roughly 35% of women of reproductive age covered by Medicaid (5.5 million women) are living in states where abortion is legal but state funds are not allowed to cover abortions beyond the Hyde exceptions of rape, incest, or life endangerment.

- Respondents could indicate multiple payment methods.

Health Access & Equity Public Health Reproductive Health Care

Children & Families Human Rights & Civil Liberties

U.S. States and Territories

Economic Studies

North America U.S. States and Territories

Center for Economic Security and Opportunity

Election ’24: Issues at Stake

Stuart M. Butler

May 23, 2024

Gayle E. Smith

May 21, 2024

Tedros Adhanom-Ghebreyesus

May 9, 2024

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Key Facts on Abortion in the United States

Usha Ranji , Karen Diep , and Alina Salganicoff Published: Nov 21, 2023

Note: This brief was updated on January 4, 2024 to correct the description of the data collected by the federal CDC Abortion Surveillance System. On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court issued a ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that overturned the constitutional right to abortion as well as the federal standards of abortion access, established by prior decisions in the cases Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey . Prior to the Dobbs ruling, the federal standard was that abortions were permitted up to fetal viability. That federal standard has been eliminated, allowing states to set policies regarding the legality of abortions and establish limits. Access to and availability of abortions varies widely between states , with some states banning almost all abortions and some states protecting abortion access.

This issue brief answers some key questions about abortion in the United States and presents data collected before and new data that was published shortly after the overturn of Roe v. Wade .

What is abortion?

How safe are abortions, how often do abortions occur, who gets abortions, at what point in pregnancy do abortions occur, where do people get abortion care, how much do abortions cost, does private insurance or medicaid cover abortions, what are public opinions about abortion.

Abortion is the medical termination of a pregnancy. It is a common medical service that many women obtain at some point in their life. There are different types of abortion methods, which the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM ) places in four categories:

- Medication Abortion – Medication abortion, also known as medical abortion or abortion with pills, is a pregnancy termination protocol that involves taking oral medications. There are two widely accepted protocols for medication abortion. In the U.S., the most common protocol involves taking two different drugs, Mifepristone and Misoprostol. Typically, an individual using medication abortion takes Mifepristone first, followed by misoprostol 24-48 hours later. In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved this protocol of medication abortion for use up to the first 70 days (10 weeks) of pregnancy, and its use has been rising for years. Another medication abortion protocol uses misoprostol alone . Patients can take 800 µg (4 pills) of misoprostol sublingually or vaginally every three hours for a total of 12 pills. The regimen is also recommended for up to 70 days (10 weeks) of pregnancy, but it is not currently approved by the FDA and is more commonly used in other countries.

Guttmacher Institute estimates that in 2020, medication was used for more than half (53%) of all abortions. While medication abortion has been available in the U.S. for more than 20 years, studies have found that many adults and women of reproductive age have not heard of medication abortion. Many have confused emergency contraception ( EC ) pills with medication abortion pills, but EC does not terminate a pregnancy. EC works by delaying or inhibiting ovulation and will not affect an established pregnancy.

- Aspiration , a minimally invasive and commonly used gynecological procedure, is the most common form of procedural abortion. It can be used to conduct abortions up to 14-16 weeks of gestation. Aspiration is also commonly used in cases of early pregnancy loss (miscarriage).

- Dilation and evacuation abortions (D&E) are usually performed after the 14th week of pregnancy. The cervix is dilated, and the pregnancy tissue is evacuated using forceps or suction.

- Induction abortions are rare and conducted later in pregnancy. They involve the use of medications to induce labor and delivery of the fetus.

( Back to top )

Decades of research have shown that abortion is a very safe medical service.

Despite its strong safety profile, abortion is the most highly regulated medical service in the country and is now banned in several states. In addition to bans on abortion altogether and telehealth, many states impose other limitations on abortion that are not medically indicated, including waiting periods, ultrasound requirements, gestational age limits, and parental notification and consent requirements. These restrictions typically delay receipt of services.

- NASEM completed an exhaustive review on the safety and effectiveness of abortion care and concluded that complications from abortion are rare and occur far less frequently than during childbirth.

- NASEM also concluded that safety is enhanced when the abortion is performed earlier in the pregnancy. State level restrictions such as waiting periods, ultrasound requirements, and gestational limits that impede access and delay abortion provision likely make abortions less safe.

- When medication abortion pills, which account for the majority of abortions, are administered at 9 weeks’ gestation or less, the pregnancy is terminated successfully 99.6% of the time, with a 0.4% risk of major complications, and an associated mortality rate of less than 0.001 percent (0.00064%).

- Medication abortion pills can be provided in a clinical setting or via telehealth (without an in-person visit). Research has found that the provision of medication abortion via telehealth is as safe and effective as the provision of the pills at an in person visit.

- Studies on procedural abortions, which include aspiration and D&E, have also found that they are very safe. Research on aspiration abortions, the most common procedural method, have found the rate of major complications of less than 1%.

There are three major data sources on abortion incidence and the characteristics of people who obtain abortions in the U.S: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Guttmacher Institute, and most recently, the Society of Family Planning’s (SFP) #WeCount project.

The federal CDC Abortion Surveillance System requests data from the central health agencies of the 50 states, DC, and New York City to document the number and characteristics of women obtaining abortions. Most states collect data from facilities where abortions are provided on the demographic characteristics of patients, gestational age, and type of abortion procedure. Reporting these data to the CDC is voluntary and not all states participate in the surveillance system. Notably, California, Maryland, and New Hampshire have not reported data on abortions to the CDC system for years. CDC publishes available data from the surveillance system annually.

Guttmacher Institute , an independent research and advocacy organization, is another major source of data on abortions in the U.S. Prior to the Dobbs ruling, Guttmacher conducted the Abortion Provider Census (APC) periodically which has provided data on abortion incidence, abortion facilities, and characteristics of abortion patients. Data from this Census are based primarily on questionnaires collected from all known facilities that provide abortion in the country, information obtained from state health departments, and Guttmacher estimates for a small portion of facilities. The most recent APC reports data from 2020.

The CDC and Guttmacher data differ in terms of methods, timeframe, and completeness, but both have shown similar trends in abortion rates over the past decade. One notable difference is that Guttmacher’s study includes continuous reporting from California, D.C., Maryland, and New Hampshire, which explains at least in part the higher number of abortions in their data.

Since the Dobbs ruling, the Guttmacher Institute has established the Monthly Abortion Provision Study to track abortion volume within the formal United States health care system. This ongoing effort collects data on and provides national and state-level estimates on procedural and medication abortions while also tracking the changes in abortion volume since 2020. The Monthly Abortion Provision Study was designed to complement Guttmacher’s APC along with other data collection efforts to allow for quick snapshots of the changing abortion landscape in the United States.

Society of Family Planning’s (SFP) #WeCount is another national reporting effort that measures changes in abortion access following the Dobbs ruling. The project reports on the number of abortions per month by state and includes data on abortions provided through clinics, private practices, hospitals, and virtual-only providers. The report does not include data on self-managed abortions that are performed without clinical supervision. The most recent #WeCount report analyzes data from April 2022 to data from June 2023, marking one full year of abortion data since Dobbs. The effort represents 83% of all providers known to #WeCount who agreed to participate in their research.

This KFF issue brief uses data from the CDC, Guttmacher, and SFP as well as other research organizations.

How has the abortion rate changed over time?

For most of the decade prior to the Dobbs ruling, there was a steady decline in abortion rates nationally, but there was a slight increase in the years just before the ruling.

In their most recent national data, Guttmacher Institute reported 930,160 abortions in 2020 and a rate of 14.4 per 1,000 women. CDC reported 622,108 abortions in 2021 and a rate of 11.6 abortions per 1,000 women (excludes CA, DC, MD, NH). Guttmacher’s study showed an upward trend in abortion from 2017 to 2020 whereas CDC’s report showed an increase in abortions from 2017 to 2021 except for a slight decrease in 2020.

While most attribute the long-term decline in abortion rates to increased use of more effective methods of contraception , several states had reduced access to low- or no-cost contraceptive care as a result of reductions in the Title X network under the Trump Administration, which may have contributed to the slight rise in abortions prior to the Dobbs ruling. Other factors that may have contributed to the increase could include greater coverage under Medicaid that subsequently made abortions more affordable in some states and broader financial support from abortion funds to help individuals pay for the costs of abortion care.

Even prior to the Dobbs ruling, abortion rates varied widely between states.

National averages can mask local and more granular differences. Lower state-level abortion rates do not reflect less need. Some of the variation has been due to the wide differences in state policies, with some states historically placing restrictions on abortion that make access and availability to nearly out of reach and, on the other side, some states enshrining protections in state Constitutions and legislation.

- In 2020, the abortion rate (per 1,000 women ages 15-44) ranged from 0.1 in Missouri to 48.9 in the District of Columbia (DC). Trends also varied between states. While the national rate of abortion increased between 2017 and 2019, some states saw declines, with particularly sharp drops in states where heavy restrictions were put into place.

While the number of abortions in the U.S. dropped immediately following the Dobbs decision, new data show that the number of abortions increased overall one year following the ruling. However, the upswing obscures the declines in abortion care in states with bans.

SFP’s #WeCount estimates there were 2,200 cumulative more abortions in the year following Dobbs (July 2022 to June 2023) compared to the pre- Dobbs period (April 2022 and May 2022). Nationally, the number of abortions varied month-by-month, with the largest decrease observed in November 2022 (73,930 abortions; 8,185 fewer abortions than pre- Dobbs period ) and the largest increase in March 2023 (92,680 abortions; 10,565 more abortions than pre- Dobbs period). The states with the largest cumulative increases in the total number of abortions provided by a clinician during the 12-month period include Illinois, Florida, North Carolina, California, and New Mexico. States with abortion bans experienced the largest cumulative decreases in the number of abortions, including Texas, Georgia, Tennessee, and Louisiana (data varies by month in each state; data not shown).

States without abortion bans experienced an increase of abortions following the Dobbs ruling likely due to a combination of reasons: increased interstate travel for abortion access, expanded in-person and virtual/telehealth capacity to see patients, increased measures to protect and cover abortion care for residents and out-of-state patients, and potentially reduced abortion-related stigma as a result of community mobilization around abortion care.

However, the overall national increase in the number of abortions masks the absence and/or scarcity of abortion care in states with total abortion bans or severe restrictions. States with total bans experienced observed 94,930 fewer clinician-provided abortions a year following the ruling (data not shown). Note, this figure is an underestimate due several state policies that restricted abortion access during the pre- Dobbs period. These estimates do not include abortions that may have been performed through self-managed means.

Most of the information about people who receive abortions comes from data prior to the Dobbs ruling. In 2021, women across a range of age groups, socioeconomic status, and racial and ethnic backgrounds obtained abortions, but the majority were obtained by women who were in their twenties, low-income, and women of color.

- Women in their twenties accounted for more than half (57%) of abortions. Nearly one-third (31%) were among women in their thirties and a small share were among women in their 40s (4%) and teens (8%).

- Seven in ten abortion patients were of women of color. Black women comprised 42% of abortion recipients, White women 30% , Hispanic women 22%, and 7% women of other races/ethnicities.

- Many women who sought abortions have children. More than six in 10 (61%) abortion patients in 2021 had at least one previous birth.

The vast majority (94%) of abortions occur during the first trimester of pregnancy according to data available from before the Dobbs decision.

Before the 2022 ruling in Dobbs, there was a federal constitutional right to abortion before the pregnancy is considered to be viable, that is, can survive outside of a pregnant person’s uterus. Viability is generally considered around 24 weeks of pregnancy. Most abortions, though, occur well before the point of fetal viability.

- Data from 2021 found that more than four in ten (45%) abortions occurred by six weeks of gestation, a third (36%) occurred between seven and nine weeks, and 13% at 10-13 weeks. Just 7% of abortions occurred after the first trimester.

- Prior to the decision in the Dobbs case, almost half of states (22) had enacted laws that ban abortion at a certain gestational age. Most of these limits are in the second trimester, but some are in the first trimester, well before fetal viability. Many of these laws were blocked because they violated the federal standard established by Roe v Wade. Some states have enacted laws banning abortions after fetal cardiac activity can be detected, or around 6 weeks of pregnancy, which is often before a person knows they are pregnant. In addition to banning abortion, states can now establish pre-viability gestational restrictions because the federal standard has been overturned.

Just over half of abortions were provided at clinics that specialize in abortion care in 2020. Others were provided at clinics that offer abortion care in addition to other family planning services.

Guttmacher Institute estimated that 96% of abortions were provided at clinics and just 4% were provided in doctors’ offices or hospitals in 2020. Most clinic-based abortions were provided at clinics that specialize in providing abortion care, but many were provided at clinics that offer a wide range of other sexual and reproductive health services like contraception and STI care. Most abortions are provided by physicians. However, in 19 states and D.C., Advanced Practice Clinicians (APCs) such as Nurse Practitioners and midwives may provide medication abortions. Conversely, 31 states prohibit clinicians other than physicians from providing abortion care.

Even prior to the ruling in Dobbs , access to abortion services was very uneven across the country though. The proliferation of restrictions in many states, particularly in the South, had greatly shrunk the availability of services in some areas. In the wake of overturning Roe v. Wade , these geographic disparities are likely to widen as more states ban abortion services altogether.

Telehealth has grown as a delivery mechanism for abortion services.

While procedural abortions must be provided in a clinical setting, medication abortion can be provided in a clinical setting or via telehealth. Access to medication abortion via telehealth had been limited for many years by a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) restriction that had permitted only certified clinicians to dispense mifepristone in a health care setting. The drug could not be mailed or picked up at a retail pharmacy. However, in December 2021, the FDA permanently revised its policy and no longer requires clinicians to dispense the drug in person. Additionally, in January 2023, the FDA finalized a change that allows retail pharmacies to dispense medication abortion pills to patients with a prescription.

While some states are regulating the use of mifepristone as an abortion method, the Biden Administration has asserted that the FDA has regulatory power over all drugs, including mifepristone. This could result in future legal action as the authority of the state to regulate health care will be pitted against the authority of the federal government to regulate drugs through the FDA will be contested.

- In a telehealth abortion, the patient typically completes an online questionnaire to assess (1) confirmation of pregnancy, (2) gestational age and (3) blood type. If determined eligible by a remote clinician, the patient is mailed the medications. This model does not require an ultrasound for pregnancy dating if the patient has regular periods and is sure of the date of their last menstrual period (in line with ACOG ’s guidelines for pregnancy dating). If the patient has irregular periods or is unsure how long they have been pregnant, they must obtain an ultrasound to confirm gestational age and rule out an ectopic pregnancy 3 and send in the images for review before receiving their medications. If the patient does not know their blood type or has Rh negative blood, the provider may prompt the patient to visit a nearby clinic for an injection to prevent adverse reactions between maternal and fetal blood ( RhoGAM ), The follow-up visit with a clinician can also happen via a telehealth visit.

- However, even in some of the states that have not banned abortion altogether, telehealth may not be available. Many states had established restrictions prior to the Dobbs ruling that limit the use of telehealth abortions by either requiring abortion patients to take the pills at a physical clinic, require ultrasounds for all abortions, set their own policies regarding the dispensing of the medications used for abortion care, or directly ban the use of telehealth for abortion care. As of November 2022, of the 33 states that have not banned abortion, eight had at least one of these restrictions, effectively prohibiting telehealth for medication abortion.

- Medication abortion has emerged as a major legal front in the battle over abortion access across the nation. Multiple cases have been filed in federal courts regarding aspects of the FDA’s regulation of medication abortion as well as the mailing of medications. One notable ongoing case is Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA , where the plaintiffs are challenging the FDA’s authority and approval process for mifepristone. The plaintiffs also contend that an 1873 anti-obscenity law, the Comstock Act, prohibits the mailing of any medication used for abortion. In April 2023, a US Supreme Court ruling allowed current FDA rules to remain in effect as the case proceeds through the courts. This means that mifepristone remains available for medication abortion either in a clinic or via telehealth where state law permits.

Data from SFP’s October 2023 #WeCount report show that abortions provided by virtual-only clinics represent approximately 5% of all abortions post- Roe . The number of telehealth abortions increased 72% from a monthly average of 4,045 abortions in April and May 2022 to 6,950 abortions per month in the 12 months post- Dobbs . Nearly all of these abortions occurred in states that permit abortions.

Self-managed abortions are provided without a clinician visit.

Self-managed abortions typically involve obtaining medication abortion pills from an online pharmacy that will send the pills by mail or by purchasing the pills from a pharmacy in another country. This does not typically involve a direct consultation with a clinician either in person or via telehealth.

Research has found that prior to Dobbs , more than one in ten patients who obtained abortions at clinics had considered self-managing their abortions. This is likely to increase going forward since abortion care is not available in many states, and there have already been reports of people ordering pills from online markets outside the U.S. medical system. Tracking information on these online orders can help fill in gaps in abortion count estimates but can also be difficult. Some companies may not share data on purchases, and it would also be unclear whether patients take the abortion medication after receiving it in the mail.

The median costs of abortion services exceed $500.

Obtaining an abortion can be costly. On average, the costs are higher for abortions in the second trimester than in the first trimester. State restrictions can also raise the costs, as people may have to travel if abortions are prohibited or not available in their area. Many people pay for abortion services out of pocket, but some people can obtain assistance from local abortion funds.

- In 2021, the median costs for people paying out of pocket in the first trimester were $568 for a medication abortion and $625 for a procedural abortion. The Federal Reserve estimates that nationally about one-third of people do not have $400 on hand for unexpected expenses. For low-income people, who are more likely to need abortion care, these costs are often unaffordable.

- The costs of abortion are higher in the second trimester compared to the first, with median self-pay of $775. In the second trimester, more intensive procedures may be needed, more are likely to be conducted in a hospital setting (although still a minority), and local options are more limited in many communities that have fewer facilities. This results in additional nonmedical costs for transportation, childcare, lodging, and lost wages. nonmedical costs for transportation, childcare, lodging, and lost wages.

- Abortion funds are independent organizations that help some people pay for the costs of abortion services. Most abortion funds are regional and have connections to clinics in their area. Funds vary, but they typically provide assistance with the costs of medical care, travel, and accommodations if needed. However, they do not reach all people seeking services, and many people are not able to afford the costs of obtaining an abortion because they cannot pay for the abortion itself or cover the costs of travel, lodging or missed work.

Insurance coverage for abortion services is heavily restricted in certain private insurance plans and public programs like Medicaid and Medicare.

Private insurance covers most women of reproductive age, and states have the responsibility to regulate fully insured private plans in their state, whereas the federal government regulates self-funded plans under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). States can choose whether abortion coverage is included or excluded in private plans that are not self-insured.

- Prior to the Dobbs ruling, several states had enacted private plan restrictions and banned abortion coverage from ACA Marketplace plans. Currently, there are 11 states that have policies restricting abortion coverage in private plans and 26 that ban coverage in any Marketplace plans. Since the Dobbs ruling, some of these states have also banned the provision of abortion services altogether.

- A handful of states ( 9 ), however, have enacted laws that require private plans to cover abortion.

- The Medicaid program covers approximately one in five women of reproductive age and four in ten who are low-income. For decades, the Hyde Amendment has banned the use of federal funds for abortion in Medicaid and other public programs unless the pregnancy is a result of rape, incest, or it endangers the woman’s life.

- States have the option to use state-only funds to cover abortions under other circumstances for women on Medicaid, which 16 states do currently. However, more than half (56% ) of women covered by Medicaid live in Hyde states.

- According to a Guttmacher Institute survey of patients in the year prior to the Dobbs ruling, a quarter (26%) of abortion patients in the study used Medicaid to pay for abortion services, 11% used private insurance, and 60% paid out of pocket. People in states with more restrictive abortion policies were less likely to use Medicaid or private insurance and more likely to pay out of pocket compared to people living in less restrictive states.

- Federal law also restricts abortion funding under the Indian Health Service, Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Over the years, language similar to that in the Hyde Amendment has been incorporated into a range of other federal programs that provide or pay for health services to women including: the military’s TRICARE program, federal prisons, the Peace Corps, and the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program.

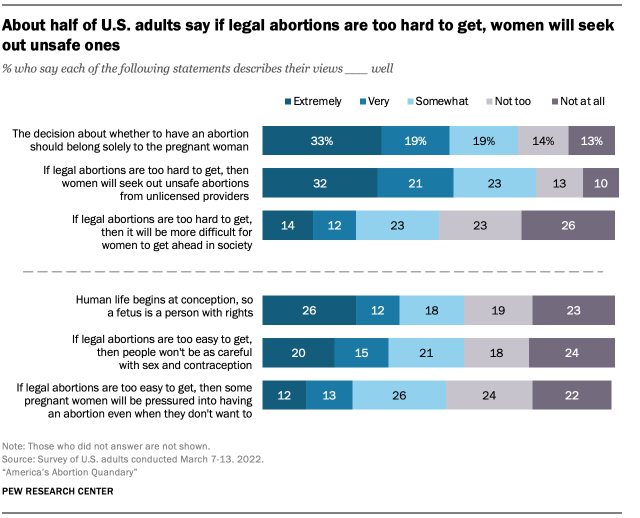

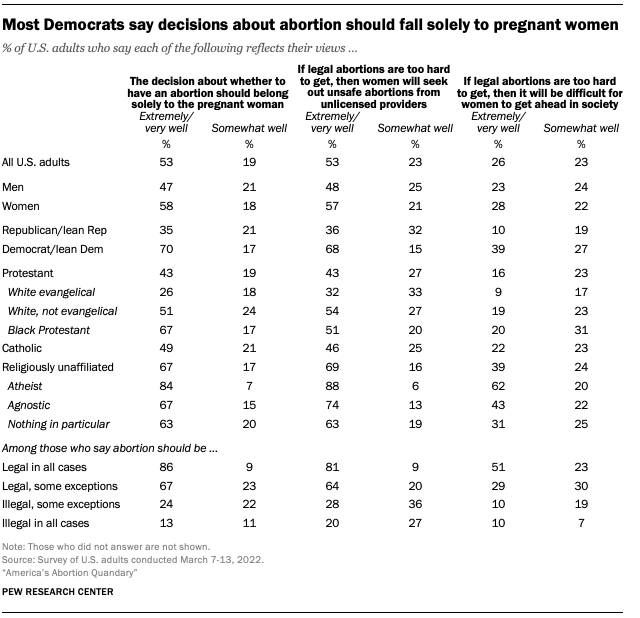

National polls have consistently found that a majority of the public did not want to see Roe v . Wade overturned and that most people feel that abortion is a personal medical decision. The public also strongly opposes the criminalization of abortion both among people who get abortion and the clinicians who provide abortion services. Nearly three quarters of adults (74%) and 79% of reproductive age women say that obtaining an abortion should be a personal choice rather than regulated by law (data not shown). For example, two-thirds of the public are concerned that bans on abortion may lead to unnecessary health problems for people experiencing pregnancy complications.

Additional KFF resources:

Abortion in the US Dashboard

Access and Coverage of Abortion Services

Issue Brief: Abortion at SCOTUS: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health

Issue Brief: State Actions to Protect and Expand Access to Abortion Services

Policy Watch: A Year After Dobbs: Policies Restricting Access to Abortion in States Even Where It’s Not Banned

Policy Watch: Employer Coverage of Travel Costs for Out-of-State Abortion

Issue Brief: Exclusion of Abortion Coverage from Employer-Sponsored Health Plans

Interactive: How State Policies Shape Access to Abortion Coverage

Medication Abortion

Issue Brief: Legal Challenges to the FDA Approval of Medication Abortion Pills

Infographic: The Availability and Use of Medication Abortion Care

Fact Sheet: The Availability and Use of Medication Abortion

Issue Brief: The Intersection of State and Federal Policies on Access to Medication Abortion Via Telehealth

Public Opinion on Abortion

Web Event: Americans’ Knowledge and Attitudes About Abortion Access and The Pending Supreme Court Ruling

KFF Health Tracking Poll: Early 2023 Update On Public Awareness On Abortion and Emergency Contraception

KFF Health Tracking Poll: Views on and Knowledge about Abortion in Wake of Leaked Supreme Court Opinion

Other Resources on Women’s Health

Interactive: State Profiles for Women’s Health

Interactive: State Health Facts on Women’s Health Indicators

Homepage: Women’s Health Policy

- Women's Health Policy

- Access to Care

Also of Interest

- The Availability and Use of Medication Abortion

- State Actions to Protect and Expand Access to Abortion Services

- Legal Challenges to State Abortion Bans Since the Dobbs Decision

- Legal Challenges to the FDA Approval of Medication Abortion Pills

- Employer Coverage of Travel Costs for Out-of-State Abortion

- Abortion in the United States Dashboard

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

By Katha Pollitt

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Jia Tolentino

By Isaac Chotiner

By Margaret Talbot

A Brief History of Abortion in the U.S.

Abortion wasn’t always a moral, political, and legal tinderbox. What changed?

A bortion laws have never been more contentious in the U.S. Yet for the first century of the country’s existence—and most of human history before that—abortion was a relatively uncontroversial fact of life.

“Abortion has existed for pretty much as long as human beings have existed,” says Joanne Rosen, JD, MA , a senior lecturer in Health Policy and Management who studies the impact of law and policy on access to abortion.

Until the mid-19th century, the U.S. attitude toward abortion was much the same as it had often been elsewhere throughout history: It was a quiet reality, legal until “quickening” (when fetal motion could be felt by the mother). In the eyes of the law, the fetus wasn’t a “separate distinct entity until then,” but rather an extension of the mother, Rosen explains.

What changed?

America’s first anti-abortion movement wasn’t driven primarily by moral or religious concerns like it is today. Instead, abortion’s first major foe in the U.S. was physicians on a mission to regulate medicine.

Until this point, abortion services had been “women’s work.” Most providers were midwives, many of whom made a good living selling abortifacient plants. They relied on methods passed down through generations, from herbal abortifacients and pessaries—a tampon-like device soaked in a solution to induce abortion—to catheter abortions that irritate the womb and force a miscarriage, to a minor surgical procedure called dilation and curettage (D&C), which remains one of the most common methods of terminating an early pregnancy.

The cottage abortion industry caught the attention of the fledgling American Medical Association, which was established in 1847 and, at the time, excluded women and Black people from membership. The AMA was keen to be taken seriously as a gatekeeper of the medical profession, and abortion services made midwives and other irregular practitioners—so-called quacks—an easy target. Their rhetoric was strategic, says Mary Fissell, PhD , the J. Mario Molina professor in the Department of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. “You have to link those midwives to providing abortion as a way of kind of getting them out of business,” Fissell says. “So organized medicine very much takes the anti-abortion position and stays with that for some time.”

Early 19th century and before

Abortion is legal in the U.S. until “quickening”

AMA campaigns to end abortion

At least 40 anti-abortion statutes are enacted in the U.S.

Comstock Act makes it illegal to sell or mail contraceptives or abortifacients

Late 19th century

OB-GYN emerges as a specialty

Griswold v. Connecticut decision finds that the Constitution guarantees a right to privacy, specifically in prescribing contraceptives, paving the way for Roe v. Wade

Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade enshrines abortion as a constitutional right

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey protects a woman's right to have an abortion prior to fetal viability

Four states pass trigger laws making it a felony to perform, procure, or prescribe an abortion if Roe is ever overturned

Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey overturned; 13 states ban abortion by October 2022

In 1857, the AMA took aim at unregulated abortion providers with a letter-writing campaign pushing state lawmakers to ban the practice. To make their case, they asserted that there was a medical consensus that life begins at conception, rather than at quickening.

The campaign succeeded. At least 40 anti-abortion laws went on the books between 1860 and 1880.

And yet some doctors continued to perform abortions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By then, abortion was illegal in almost all states and territories, but during the Depression era, “doctors could see why women wouldn’t want a child,” and many would perform them anyway, Fissell says. In the 1920s and through the 1930s, many cities had physicians who specialized in abortions, and other doctors would refer patients to them “off book.”

That leniency faded with the end of World War II. “All across America, it’s very much about gender roles, and women are supposed to be in the home, having babies,” Fissell says. This shift in the 1940s and ’50s meant that more doctors were prosecuted for performing abortions, which drove the practice underground and into less skilled hands. In the 1950s and 1960s, up to 1.2 million illegal abortions were performed each year in the U.S., according to the Guttmacher Institute . In 1965, 17% of reported deaths attributed to pregnancy and childbirth were associated with illegal abortion.

A rubella outbreak from 1963–1965 moved the dial again, back toward more liberal abortion laws. Catching rubella during pregnancy could cause severe birth defects, leading medical authorities to endorse therapeutic abortions . But these safe, legal abortions remained largely the preserve of the privileged. “Women who are well-to-do have always managed to get abortions, almost always without a penalty,” says Fissell. “But God help her if she was a single, Black, working-class woman.”

Women who could afford it brought their cases to court to fight for access to hospital abortions. Other women gained approval for abortions with proof from a physician that carrying the pregnancy would endanger her life or her physical or mental health. These cases set off a wave of abortion reform bills in state legislatures that helped set the stage for Roe v. Wade . By the time Roe was decided in 1973, legal abortions were already available in 17 states—and not just to save a woman’s life.

But raising the issue to the level of the Supreme Court and enshrining abortion rights for all Americans also galvanized opposition to it and mobilized anti-abortion groups. “ Roe was under attack virtually from the moment it was decided,” says Rosen.

In 1992 another Supreme Court case, Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey posed the most significant existential threat to Roe . Rosen calls it “the case that launched a thousand abortion regulations,” upholding Roe but giving states far greater scope to regulate abortion prior to fetal viability. However, defining that nebulous milestone a became a flashpoint for debate as medical advancements saw babies survive earlier and earlier outside the womb. Sonograms became routine around the same time, making fetal life easier to grasp and “putting wind in the sails of the ‘pro-life’ movement,” Rosen says. Then in June, the Supreme Court overturned both Roe and Casey .

For many Americans, that meant the return to the conundrum that led Norma McCorvey—a.k.a. Jane Roe—to the Supreme Court in 1971: being poor and pregnant, and seeking an abortion in a state that had banned them in all but the narrowest of circumstances.

The history of abortion in the U.S. suggests the tides will turn again. “We often see periods of toleration followed by periods of repression,” says Fissell. The current moment is unequivocally marked by the latter. What remains to be seen is how long it will last.

From Public Health On Call Podcast

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Womens Health

Understanding why women seek abortions in the US

M antonia biggs.

1 Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health, Bixby Center for Global Reproductive Health, University of California, San Francisco, Oakland, California, USA

Heather Gould

Diana greene foster.

The current political climate with regards to abortion in the US, along with the economic recession may be affecting women’s reasons for seeking abortion, warranting a new investigation into the reasons why women seek abortion.

Data for this study were drawn from baseline quantitative and qualitative data from the Turnaway Study , an ongoing, five-year, longitudinal study evaluating the health and socioeconomic consequences of receiving or being denied an abortion in the US. While the study has followed women for over two full years, it relies on the baseline data which were collected from 2008 through the end of 2010. The sample included 954 women from 30 abortion facilities across the US who responded to two open ended questions regarding the reasons why they wanted to terminate their pregnancy approximately one week after seeking an abortion.

Women’s reasons for seeking an abortion fell into 11 broad themes. The predominant themes identified as reasons for seeking abortion included financial reasons (40%), timing (36%), partner related reasons (31%), and the need to focus on other children (29%). Most women reported multiple reasons for seeking an abortion crossing over several themes (64%). Using mixed effects multivariate logistic regression analyses, we identified the social and demographic predictors of the predominant themes women gave for seeking an abortion.

Conclusions

Study findings demonstrate that the reasons women seek abortion are complex and interrelated, similar to those found in previous studies. While some women stated only one factor that contributed to their desire to terminate their pregnancies, others pointed to a myriad of factors that, cumulatively, resulted in their seeking abortion. As indicated by the differences we observed among women’s reasons by individual characteristics, women seek abortion for reasons related to their circumstances, including their socioeconomic status, age, health, parity and marital status. It is important that policy makers consider women’s motivations for choosing abortion, as decisions to support or oppose such legislation could have profound effects on the health, socioeconomic outcomes and life trajectories of women facing unwanted pregnancies.

While the topic of abortion has long been the subject of fierce public and policy debate in the United States, an understanding of why women seek abortion has been largely missing from the discussion [ 1 ]. In an effort to maintain privacy, adhere to perceived social norms, and shield themselves from stigma, the majority of American women who have had abortions— approximately 1.21 million women per year [ 2 ]– do not publicly disclose their abortion experiences or engage in policy discussions as a represented group [ 3 - 5 ].

A review of several international and a handful of US qualitative and quantitative articles considered reasons for abortion among women in 26 “high-income” countries [ 6 ]. Of these, four studies (two primarily quantitative, one primarily qualitative and one that used mixed methods) were conducted in the US [ 7 - 10 ]. This review found that, despite methodological differences among the studies, a consistent picture of women’s reasons for abortion emerged, that could be encapsulated in three categories: 1) “Women-focused” reasons, such as those related to timing, the woman’s physical or mental health, or completed family size; 2) “Other-focused” reasons, such as those related to the intimate partner, the potential child, existing children, or the influences of other people, and 3) “Material” reasons, such as financial and housing limitations. These categories were not mutually exclusive; women in nearly all of the studies reported multiple reasons for their abortion.

The largest of the US studies included in the review, by Finer and colleagues [ 9 ], utilized data from a structured survey conducted in 2004 with 1,209 abortion patients across the US, as well as open-ended, in-depth interviews conducted with 38 patients from four facilities, nearly half of whom were in their second trimester of pregnancy. Quantitative data from this study were compared to survey data collected from nationally representative samples in 1987 [ 11 , 12 ] and 2000 [ 13 ]. The most commonly reported reasons for abortion in 2004 (selected from a researcher-generated list of possible reasons with write-in options for other reasons) were largely similar to those found in the 1987 study [ 11 ]. The top three reason categories cited in both studies were: 1) “Having a baby would dramatically change my life” (i.e., interfere with education, employment and ability to take care of existing children and other dependents) (74% in 2004 and 78% in 1987), 2) “I can’t afford a baby now” (e.g., unmarried, student, can’t afford childcare or basic needs) (73% in 2004 and 69% in 1987), and 3) “I don’t want to be a single mother or am having relationship problems” (48% in 2004 and 52% in 1987). A sizeable proportion of women in 2004 and 1987 also reported having completed their childbearing (38% and 28%), not being ready for a/another child (32% and 36%), and not wanting people to know they had sex or became pregnant (25% and 33%). Considering all of the reasons women reported, the authors observed that the reasons described by the majority of women (74%) signaled a sense of emotional and financial responsibility to individuals other than themselves, including existing or future children, and were multi-dimensional. Greater weeks of gestation were found to be related with citing concerns about fetal health as reasons for abortion. The authors did not examine associations between weeks of gestation with some of the other more frequently mentioned reasons for abortion.

While the US abortion rate appears to have stabilized after a national decline, this decline has been slower among low-income women and in certain states, suggesting possible disparities in access to effective contraceptive methods and/or economic challenges preventing women from feeling they are able to care for a child [ 2 , 13 ]. According to national estimates for 2005 and 2008, changes in the abortion rate varied by region, with the South and West seeing small declines, and the Northwest and Midwest seeing no change over that period [ 2 ].

Furthermore, the changing political climate and increasing restrictive legislation with regards to abortion in this country [ 14 ], in conjunction with the economic recession, may be affecting women’s reasons for seeking abortion, warranting a fresh investigation into these issues. This study builds upon and extends the small body of literature that documents US women’s reasons for abortion [ 6 ]. While two other papers using data from the Turnaway Study (see below) describe how women who indicate partner related reasons or reasons related to their own alcohol, tobacco and/or drug use, differ from those who do not mention these reasons [ 15 , 16 ] this study presents all of the reasons women from the Turnaway Study gave for seeking abortion, as described in their own words.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research. Written and oral consent was obtained from all participants.

Study design

Data for this study were drawn from baseline quantitative and qualitative data from the Turnaway Study, an ongoing, five-year, longitudinal study evaluating the health and socioeconomic consequences of receiving or being denied an abortion in the US. While the study has followed women for two full years, this analysis relies on the baseline data which were collected from 2008 through the end of 2011. The study design, recruitment and research methods and some findings from this study have been published elsewhere [ 15 , 17 - 19 ]. This study overcomes several limitations of previous studies on this topic. Most importantly, we interviewed a large sample of both adult and adolescent women, including many women who sought abortions at later gestations of pregnancy. We asked women about their reasons for abortion using an open-ended question, rather than relying on a checklist of researcher-generated reasons.

This paper draws on baseline data from interviews conducted one week after receiving or being denied an abortion at the recruitment facility.

Recruitment

Women seeking abortion care at 30 US facilities (abortion clinics, other clinics and hospitals) between January 2008 and December 2010 were recruited to participate in the study. Facilities were identified using the National Abortion Federation membership directory, as well as through professional contacts in the abortion research community. While the gestational limits of the recruitment facilities varied (from 10 weeks to the end of the second trimester), they each had the latest gestational limit for providing abortion of any facility within 150 miles. These sites were selected because we thought that women denied an abortion would be unlikely to get one elsewhere. The facilities performed an average of 2,400 abortions annually (range 440–8,000) and were located in 21 states throughout the US representing every US region [ 17 ].

Abortion patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were English- or Spanish-speaking, aged 15 years or older, had no fetal diagnoses or demise, and were within the gestational age range of one of three study groups. At each facility, a designated point person was trained by Turnaway study researchers to oversee and conduct site recruitment activities. After assessing potential participants’ eligibility based on their age, language and gestational age, the facility point person or facility staff briefly informed potential participants about the study. Participants were usually approached in a private exam room after receiving an ultrasound and were told that the purpose of the study was to learn more about how unintended pregnancy affects women’s lives. Participants who expressed willingness to learn more about the study were led to a private location within the clinic, where they were given additional study information, the informed consent documents, and human subjects’ Bill of Rights a .