Free Cultural Studies Essay Examples & Topics

There is a field in academia that analyzes the interactions between anthropological, political, aesthetic, and socioeconomic institutions. It is referred to as cultural studies . This area is interdisciplinary, meaning that it combines and examines several departments. First brought up by British scientists in the 1950s, it is now studied all over the world.

The scope of cultural studies is vast. From history and politics to literature and art, this field looks at how culture is shaped and formed. It also examines the complex interactions of race and gender and how they shape a person’s identity.

In this article, our team has listed some tips and tricks on how to write a cultural studies essay. You will encounter many fascinating aspects in this field that will be exciting to study. That is the reason why we have prepared a list of cultural studies essay topics. You can choose one that catches your eye right here! Finally, you will also find free sample essays that you can use as a source of inspiration for your work.

15 Top Cultural Studies Essay Topics

The work process on an essay begins with a tough choice. After all, there are thousands of things that you can explore. In the list below, you will find cultural studies topics for your analytical paper.

- The role of human agency in cultural studies and how research techniques are chosen.

- Examining generational changes through evolution in music and musical taste in young adults.

- Does popular culture have the power to influence global intercultural and political relationships?

- Different approaches to self-analysis and self-reflection examined through the lens of philosophy.

- Who decides what constitutes a “cultural artifact”?

- The difference in religious and cultural practices between Japanese and Chinese Buddhists.

- Exploring the symbiotic relationship between culture and tradition in the UK.

- Do people understand culture nowadays the same way they understood it a century ago?

- Which factors do we have to take into account when conducting arts and culture research of ancient civilizations?

- Día de Los Muertos: a commentary on an entirely different perspective on death.

- American society as represented in popular graphic novels.

- An analysis of the different approaches to visual culture from the perspective of a corporate logo graphic designer.

- What can French cinema of the 20 th century tell us about the culture of the time?

- Narrative storytelling in different forms of media: novels, television, and video games.

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the direction of pop culture.

In case you haven’t found your perfect idea in the list, feel free to try our title generator . It will compose a new topic for your cultural studies essay from scratch.

How to Write a Cultural Studies Essay

With an ideal topic for your research, you start working on your cultural analysis essay. Below you will find all the necessary steps that will lead you to write a flawless paper.

- Pick a focus. You cannot write an entire essay on the prospect of culture alone. Thus, you need to narrow down your field and the scope of your research. Spend some time reading relevant materials to decide what you want your paper to say.

- Formulate your thesis. As the backbone of your assignment, it will carry you through the entire process. Writing a thesis statement brings you one step closer to nailing the whole essay down. Think “What is my paper about?” and come up with a single sentence answer – this will be your statement.

- Provide context for your intro. The introduction is the place for setting the scene for the rest of your paper. Take time to define the terminology. Plus, you should outline what you will talk about in the rest of the essay. Make sure to keep it brief – the introduction shouldn’t take up longer than a paragraph.

- Develop your ideas in the body. It is the place for you to explore the points you’re trying to make. Examine both sides of the argument and provide ample evidence to support your claims. Don’t forget to cite your sources!

- Conclude the paper effectively. The final part is usually the hardest, but you don’t need to make it too complicated. Summarize your findings and restate your thesis statement for the conclusion. Make sure you don’t bring in any new points or arguments at this stage.

- Add references. To show that you’re not pulling your ideas out of thin air, cite your sources. Add a bibliography at the end to prove you’ve done your research. You will need to put them in alphabetical order. So, ensure you do that correctly.

Thank you for reading! Now, you can proceed to read through the examples of essays about cultural studies that we provided below.

616 Best Essay Examples on Cultural Studies

Raymond williams’ “culture is ordinary”.

- Words: 1248

What Is Popular Culture? Definition and Analysis

- Words: 1399

Comparing the US and Italian Cultures

- Words: 2217

“Never Marry a Mexican”: Theme Analysis & Summary

- Words: 2244

Power and Culture: Relationship and Effects

- Words: 2783

Similarities of Asian Countries

- Words: 2356

Cultural Comparison: The United States of America and Japan

Philippines dressing culture and customs.

- Words: 1454

Nok Culture’s Main Characteristic Features

- Words: 1483

Chinese Traditional Festivals and Culture

- Words: 2763

The Influence of Ramayana on the Indian Culture

Pashtun culture: cultural presentation.

- Words: 1083

The United States of America’s Culture

- Words: 1367

Culture and Development in Nigeria

- Words: 2718

The Luo Culture of Kenya

- Words: 3544

Culture Identity: Asian Culture

- Words: 1101

UAE and Culture

- Words: 1210

Traditions and Their Impact on Personality Development

- Words: 1131

Art and Science: One Culture or Two, Difference and Similarity

Impact of globalization on the maasai peoples` culture.

- Words: 1736

Three Stages of Cultural Development

- Words: 1165

The Beautiful Country of Kazakhstan: Kazakh Culture

- Words: 1644

Culture, Subculture, and Their Differences

- Words: 1157

Saudi Arabian Culture

- Words: 1486

Kazakhstani Culture Through Hofstede’s Theory

- Words: 1480

Trobriand Society: Gender and Its Roles

- Words: 3118

Football Impact on England’s Culture

- Words: 1096

African Cultural Traditions and Communication

- Words: 1114

Polygamy in Islam

Saudi traditional clothing.

- Words: 1815

Indian Custom and Culture Community

- Words: 2207

Anthropological Approach to Culture

Culture of the dominican republic.

- Words: 2229

Gothic Lifestyle as a Subculture

Culture and health correlation, culturagram of african americans living in jackson, taiwan and the u.s. cultural elements.

- Words: 2265

The Nature of People and Culture

The jarawa people and their culture.

- Words: 1438

Differences in Culture between America and Sudan

Society, culture, and civilization, chinese manhua history development.

- Words: 5401

What Role Does Food Play in Cultural Identity?

- Words: 1199

American Culture Pros & Cons

The bushmen: culture and traditions, cultural prostitution: okinawa, japan, and hawaii.

- Words: 2370

Time in Mahfouz’s “Half a Day” and Dali’s “Persistence of Memory”

- Words: 1092

Cultural Diversity and Cultural Universals Relations: Anthropological Perspective

“signs of life in the usa” by maasik and solomon, discussion: cultural roots and routes.

- Words: 1469

Implications of Korean Culture on Health

- Words: 1439

Hells Angels as a Motorcycle Subculture

Anne allison: nightwork in japan.

- Words: 1548

Indigenous Australian Culture, History, Importance

- Words: 2102

Meaning of the Machine in the Garden

The history of the hippie cultural movement.

- Words: 1485

Late Shang Dynasty: Ritualistic Wine Vessel – Zun

- Words: 1108

Cultural Change: Mechanisms and Examples

Wheeler’s theory and examples of pilgrimage, perception of intelligence in different cultures.

- Words: 1137

The Essence of Cultural Ecology: The Main Tenets

Is cultural relativism a viable way to live, the māori culture of new zealand.

- Words: 1326

Singapore’s Culture and Social Institutions

- Words: 1288

Cosplay Subculture Definition

The role of chinese hats in chinese culture.

- Words: 2307

Dubai’s Food, Dress Code and Culture

- Words: 1124

Non-Material and Material Culture

Ballads and their social functions.

- Words: 3314

Analysis of Culture and Environmental Problems

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender subculture.

- Words: 2000

Comparison Between the Body Rituals in Nacirema and American Society

Hofstede’s study: cultural dimensions, african civilizations. the bantu culture, birthday celebrations in the china.

- Words: 1664

Indian and Greek Cultures Comparison

- Words: 2789

Greetings in Etiquette in Society by Emily Post

Punjabi: the culture, cultural effects on health care choices.

- Words: 3292

Meaning of Culture and Its Importance

The power of a symbol, art of the abbasid caliphate analysis.

- Words: 1482

Caribbean Culture and Cuisine: A Melting Pot of Culture

- Words: 1601

The Sub-Culture of the American Circuses of the Early 20th Century

- Words: 3909

Italian Heritage and Its Impact on Life in the US

- Words: 1111

Cultural Background: Personal Journey

Asian community’s cultural values and attitudes.

- Words: 4933

“Cargo Cult Science” by Richard Feynman

Traditional and nontraditional cultures of the usa, the counterculture of the 1960s, filial piety.

- Words: 1120

Positive Psychology and Chinese Culture

- Words: 2975

African American Culture: Psychological Processes

- Words: 3031

Angelou Maya’s Presentation on the African Culture

- Words: 1107

Popular Culture in the History of the USA

- Words: 1119

Cultural Artifacts and the Importance of Humanities

Africans in mexico: influence on the mexican culture, african-american cultural group and the provision of services to african americans, the importance of cultural values for a society, the mysteries of samothrace and its cultic practices.

- Words: 2846

Cultural Appropriation: Christina Aguilera in Braids

African american heritage and culture, the university of west indies, the caribbean identity, and the globalization agenda.

- Words: 1393

The History of Guqin in Chinese Culture

- Words: 1652

Expanding Chinese Cultural Knowledge in Health Beliefs

- Words: 2291

British Punk Zines as a Commentary on the Sociopolitical Climate of the 1970s

- Words: 2223

Exegeses-Ruling Class and Ruling Ideas by Karl Marx

Cultural competence: purnell model.

- Words: 7928

Cultural Studies: Ideology, Representation

- Words: 1704

World Society and Culture in Mexico

- Words: 2775

Theory of the Aryan Race: Historical Point of View

- Words: 2770

Theodor Adorno’s “Culture Industry” Analysis

- Words: 1489

Culture for Sale: The National Museum in Singapore

- Words: 1806

Body Piercing in Different Cultures

- Words: 1589

Korean Popular Culture: Attractiveness and Popularity

“high” and “low” culture in design.

- Words: 2560

Jamaican Culture and Philosophy

What is chinese culture.

- Words: 1493

The Phenomenon of Queer Customs

Role of food in cultural studies: globalization and exchange of food.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Cultural Studies: A Theoretical, Historical and Practical Overview

Cultural studies has become an unavoidable part of literary criticism and theory. Cultural studies is an advanced interdisciplinary arena of research and teaching that examines the means in which "culture" creates and transforms day to day life, individual experiences, power and social relations. As a developing field of study it is important to know the beginning and growth of cultural studies as a field of knowledge. This article is an attempt to present an introductory information regarding the beginning, definitions, schools important theoreticians and practical aspects of cultural studies. This study is analytical in nature and historical information are presented mostly. The objective of this article is to give a quick understanding about the beginners in the field of Cultural studies.

Related Papers

Introductory Notes on Cultural Studies

Introduction to Cultural Studies is a course of study for students pursuing a Masters in English Literature. As part of the course, it will be helpful for the students if they get a quick-tour kind of an introduction to the discipline called Cultural Studies. As a study of culture, the title presupposes a knowledge about what encompasses the word 'culture', we may attempt a definition of it first. Culture can be defined as an asymmetric combinations of abstract and actual aspects of elements like language, art, food, dress, systems like family, religion, education, and practices like mourning and 'merrying', all of which we refer to as cultural artifacts. It is assumed that values and identities are formed, interacted and represented in a society in association with these artifacts. Cultural Studies, therefore, is a constant engagement with contemporary culture by studying, analyzing and interacting with the institutions of culture and their functions in the society.

Chun Lean LIM

This course introduces students to the work and significance of representation and power in the understanding of culture as social practice. It helps students to understand the relationships among sign, culture and the making of meanings in society. From this base it approaches the question of ideology and subjectivity in the shaping of culture. With reference to various cultural texts and social contexts, we study examples of cultural production from history and politics to lived experiences of the everyday, from photography and art to cinema and museum, from popular culture to lifestyle etc. In appreciating divergent concerns in the critical analysis of culture and power, we focus on selected topics both mainstream and emergent, with an emphasis on contemporary developments in the Asian contexts. A brief account of the intellectual formations of Cultural Studies will be provided to allow students to appreciate the global, regional and local perspectives in the evolving field of study.

Joanna Dziadowiec-Greganić

Until recently, cultural studies was a part of knowledge that was treated by the academic world in an ambivalent way. On one hand, there was a belief that the humanities, including the social sciences, in some way belong to each other, with the understanding that they at least partly create a common field. On the other hand, there was a visible tendency to diversify the expanding specializations, by creating new disciplines of knowledge which were separated from the original core. Cultural studies were perceived as an eclectic type of knowledge embracing almost everything, starting with demography and archeology through sociology, psychology and history, also encompassing economics and cultural management. This situation was also expressed by the institutional structure of scientific disciplines. Nowadays it has become apparent that this postmodern fragmentization of culture is petering out. This has created the necessity of a new synthesis in the humanities. It has resulted in the institutionalization of ‘cultural studies’ for which the Polish equivalent can be expressed as ‘kulturoznawstwo.’ Moreover, in relation to postmodernism, (especially models of postmodern narration and phenomena such as over interpretation while analyzing an investigated object), which is a common feature of all the humanities, we may go beyond the postmodern canons. While postmodernism is becoming the subject of reflection in the history of knowledge, there are new methodological propositions coming to light. They are partly the continuation of but also the opposition to postmodern depictions. In that exact moment, cultural studies as a scientific discipline arises. These two reasons, one institutional and the other thematic, have become an invitation for discussion about the identity of cultural studies as a field of knowledge. The aim of the conference was to bring together researchers who are engaged in research on culture. The discussion was not limited to their differences, but also included common points in particular disciplines. The research subject has taken the first step towards formulating a general methodology of the science of culture. The variety of presented research perspectives and the problems which cultural studies will face points towards the necessity of further ventures which would organize and order both subjects and methods of cultural studies research. The opportunity to take more profound reflections and desired polemics in this field will surely be included in the publication of the post-conference materials.

Dr. MANJEET K R . KASHYAP

The crossing of disciplinary boundaries by the new humanities and the “humanities-tocome”is lumped as “cultural studies” in a very confused way.The term, cultural studies, wascoined by Richard Hoggart in 1964; and the movement was inaugurated by Raymond Williams’ Culture and Society (1958) and by The Uses of Literacy (1958), and it became institutionalized in the influential Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies [CCCS], founded by Hoggart in 1964. It is evident that much of what falls under cultural studies could easily be classified under various other labels such as marxism, structuralism, new historicism, feminism and postcolonialism. Since the term has become popularized, I would not focus on why it is named so. Instead, the concern of this paper is to provide a deep theoretical understanding of cultural studies. Cultural studies analyzes the social, religious, cultural, discourses and institutions, and their role in the society. It basically aims to study the functioning of the social, economic, and political forces and power-structure that produce all forms of cultural phenomena and give them social “meanings” and significance.

Dumitru Tucan

Jarosław Płuciennik

The main proposal of the article is to bring into focus humanism as a project which was always present in the Renaissance philology and is still into the main areas of reflection of the Enlightenment and Modernity. The large part of the article consists of a review of the philological tradition since the Renaissance, and it tries to describe an interdisciplinary nature of cultural studies, which always referred to politics and political science, and comparative multilingual approaches, which made them strictly international. Recent development in the area of digital humanities makes cultural studies similar to media studies. Humanism is the only component of the studies which is indispensable because it is not to be replaced by artificial intelligence.

JORGE GERMAN GARCIA HUGHES

Canadian Review of Comparative Literature 31, 460-467

Manfred Engel

Discusses differences between the concept of "Cultural Studies" in the English-speaking world and the German "Kulturwissenschaft". Also sketches the project of a cultural and literary history of the dream as an example for "cultural literary studies". All essays of the volume freely available under: https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/crcl/index.php/crcl/issue/view/681

Simon During

Parvati Raghuram

© Richard Johnson, Deborah Chambers, Parvati Raghuram and Estella Tincknell 2004 First published 2004 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this ...

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Clinical Neuroscience

Sailesh Gaikwad

Polar Research

AHMED AL-MAFRACHI

Journal of Global Health

Leon Bijlmakers

Natalie Coull

Journal of Applied Physics

Rafael Espinlsa

PROIECT DEZVOLTARE PERSONALA

Elena Andreea

Samsul Arifin

INICIO LEGIS

Alief Assyamiri

Functional Imaging and Modelling of the Heart

Gemma Piella

Pedro Ferrer Perez

Indian journal of surgical oncology

samit purohit

Crop Breeding and Applied Biotechnology

Flavio Capettini

International Journal of Advanced Research

Ilias Zakariaa

BMC Hematology

nizuwan azman

Pavle Apostoloski

Mark Czerwinski

Hugo Raposo

Zenodo (CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research)

Sotiris Papadelis

Studia graeco-arabica

Daniel Regnier

Draft Essay

W. B. Allen

Maria Veralice Barroso

Thomas Ford

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Stuart Hall and the Rise of Cultural Studies

In the summer of 1983, the Jamaican scholar Stuart Hall, who lived and taught in England, travelled to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, to deliver a series of lectures on something called “Cultural Studies.” At the time, many academics still considered the serious study of popular culture beneath them; a much starker division existed, then, between what Hall termed the “authenticated, validated” tastes of the upper classes and the unrefined culture of the masses. But Hall did not regard this hierarchy as useful. Culture, he argued, does not consist of what the educated élites happen to fancy, such as classical music or the fine arts. It is, simply, “experience lived, experience interpreted, experience defined.” And it can tell us things about the world, he believed, that more traditional studies of politics or economics alone could not.

A masterful orator, Hall energized the audience in Illinois, a group of thinkers and writers from around the world who had gathered for a summer institute devoted to parsing Marxist approaches to cultural analysis. A young scholar named Jennifer Daryl Slack believed she was witnessing something special and decided to tape and transcribe the lectures. After more than a decade of coaxing, Hall finally agreed to edit these transcripts for publication, a process that took years. The result is “ Cultural Studies 1983: A Theoretical History ,” which was published, last fall, as part of an ongoing Duke University Press series called “Stuart Hall: Selected Writings,” chronicling the career and influence of Hall, who died in 2014.

Broadly speaking, cultural studies is not one arm of the humanities so much as an attempt to use all of those arms at once. It emerged in England, in the nineteen-fifties and sixties, when scholars from working-class backgrounds, such as Richard Hoggart and Raymond Williams, began thinking about the distance between canonical cultural touchstones—the music or books that were supposed to teach you how to be civil and well-mannered—and their own upbringings. These scholars believed that the rise of mass communications and popular forms were permanently changing our relationship to power and authority, and to one another. There was no longer consensus. Hall was interested in the experience of being alive during such disruptive times. What is culture, he proposed, but an attempt to grasp at these changes, to wrap one’s head around what is newly possible?

Hall retained faith that culture was a site of “negotiation,” as he put it, a space of give and take where intended meanings could be short-circuited. “Popular culture is one of the sites where this struggle for and against a culture of the powerful is engaged: it is also the stake to be won or lost in that struggle,” he argues. “It is the arena of consent and resistance.” In a free society, culture does not answer to central, governmental dictates, but it nonetheless embodies an unconscious sense of the values we share, of what it means to be right or wrong. Over his career, Hall became fascinated with theories of “reception”—how we decode the different messages that culture is telling us, how culture helps us choose our own identities. He wasn’t merely interested in interpreting new forms, such as film or television, using the tools that scholars had previously brought to bear on literature. He was interested in understanding the various political, economic, or social forces that converged in these media. It wasn’t merely the content or the language of the nightly news, or middlebrow magazines, that told us what to think; it was also how they were structured, packaged, and distributed.

According to Slack and Lawrence Grossberg, the editors of “Cultural Studies 1983,” Hall was reluctant to publish these lectures because he feared they would be read as an all-purpose critical toolkit rather than a series of carefully situated historical conversations. Hall himself was ambivalent about what he perceived to be the American fetish for theory, a belief that intellectual work was merely, in Slack and Grossberg’s words, a “search for the right theory which, once found, would unlock the secrets of any social reality.” It wasn’t this simple. (I have found myself wondering what Hall would make of how cultural criticism of a sort that can read like ideological pattern-recognition has proliferated in the age of social media.)

Over the course of his lectures, Hall carefully wrestles with forebears, including the British scholar F. R. Leavis and also Williams and Hoggart (the latter founded Birmingham University’s influential Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies, which Hall directed in the seventies). Gradually, the lectures cluster around questions of how we give our lives meaning, how we recognize and understand “the culture we never see, the culture we don’t think of as cultivated.” These lectures aren’t instructions for “doing” cultural studies—until the very end, they barely touch on emerging cultural forms that intrigued Hall, such as reggae and punk rock. Instead, they try to show how far back these questions reach.

For Hall, these questions emerged from his own life—a fact that his memoir, “ Familiar Stranger ,” published by Duke, in April, brings into sharp focus. Hall was born in 1932, in Kingston. His father, Herman, was the first nonwhite person to hold a senior position with the Jamaican office of United Fruit, an American farming and agricultural corporation; his mother, Jessie, was mixed-race. They considered themselves a class apart, Hall explains, indulging a “gross colonial simulacrum of upper-middle-class England.” From a young age, he felt alienated by their cozy embrace of the island’s racial hierarchy. As a child, his skin was darker than the rest of his family’s, prompting his sister to tease, “Where did you get this coolie baby from?” It became a family joke—one he would revisit often. And yet he felt no authentic connection to working-class Jamaica, either, “conscious of the chasm that separated me from the multitude.” The mild sense of guilt that he describes feels strikingly contemporary. And he had trouble articulating the terms of this discomfort: “I could not find a language in which to unravel the contradictions or to confront my family with what I really thought of their values, behaviors, and aspirations.” The desire to find that language would become the animating spark of his professional life.

In 1951, Hall won a Rhodes Scholarship to study at Oxford. He was part of the “Windrush” generation—a term used to describe the waves of West Indian migration to England in the postwar years. Although Hall came from a different class than most of these migrants, he felt a connection to his countrymen. “Suddenly everything looked different,” he would later remember of his arrival in England. He clipped a newspaper photo of three Jamaicans who arrived around the time he did. Two of them are carpenters and one is an aspiring boxer; they are all dressed to the nines. “This was style . They were on a mission, determined to be recognized as participants in the modern world and to make it theirs. I look at this photograph every morning as I myself head out for that world,” he writes.

Hall found ready disciples in American universities, though it might be argued that the spirit which animated cultural studies in England had existed in the U.S. since the fifties and sixties, in underground magazines and the alternative press. The American fantasy of its supposedly “classless” society has always given “culture” a slightly different meaning than it has in England, where social trajectories were more rigidly defined. What scholars like Hall were actually reckoning with was the “American phase” of British life. After the Second World War, England was no longer the “paradigm case” of Western industrial society. America, that grand experiment, where mass media and consumer culture proliferated freely, became the harbinger for what was to come. In a land where rags-to-riches mobility is—or so we tend to imagine—just one hit away, culture is about what you want to project into the world, whether you are fronting as a member of the élite or as an everyman, offering your interpretation of Shakespeare or of “The Matrix.” When culture is about self-fashioning, there’s even space to be a down-to-earth billionaire.

How did we get here, to this present, with our imaginations limited by a common sense of possibility that we did not choose? “ Selected Political Writings ,” the other book of Hall’s work that Duke has published as part of its series, focusses largely on the lengthy British phase of Hall’s life. The centerpiece essay is “The Great Moving Right Show,” his 1979 analysis of Margaret Thatcher’s “authoritarian populism.” Her rise was as much a cultural turning point as a political one, in Hall’s view—an enmity toward the struggling masses, obscured by her platform’s projected attitude of tough, Victorian moderation. Many of the pieces in this collection orbit the topic of “common sense,” how culture and politics together reinforce an idea of what is acceptable at any given time.

This was the simple question at the heart of Hall’s complex, occasionally dense work. He became one of the great public intellectuals of his time, an activist for social justice and against nuclear proliferation, a constant presence on British radio and television—though this work is given only a cursory mention in “Familiar Stranger.” Similarly, he doesn’t mention Marxism, his key intellectual framework, until the final chapters of that book. Instead, as in much of his more traditional scholarship, he focusses on his shifting sense of his own context. Culture, after all, is a matter of constructing a relationship between oneself and the world. “People have to have a language to speak about where they are and what other possible futures are available to them,” he observed, in his 1983 lectures. “These futures may not be real; if you try to concretize them immediately, you may find there is nothing there. But what is there, what is real, is the possibility of being someone else, of being in some other social space from the one in which you have already been placed.” He could have been describing his own self-awakening.

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Adam Iscoe

Sociology, Cultural Studies and the Cultural Turn

Cite this chapter.

- Gregor McLennan

878 Accesses

2 Citations

For 40 years, the relationship between sociology and cultural studies has posed central questions of self-definition and practice for both projects. By orchestrating a range of manifesto-style statements — the full literature can only be gestured towards — this chapter offers an analytical profile of the unfolding dealings between the two formations, starting with the prevailing discourse around sociology at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) in the 1970s (‘Birmingham’). The second sketch — ‘postmodern con-juncturalism’ — takes as background the worldwide growth of cultural studies as an undergraduate quasi-discipline, involving the active displacement of disciplinary sociology. In a third movement —‘sociological readjustment’ — the tables are ostensibly turned once again, but at this point the whole notion of the ‘cultural turn’, which rhetorically governs most of the debate, requires critical focus. In the years after 2000, a mood of ‘pragmatic reflexivity’ emerges in cultural studies and sociology alike, in which, despite latent tensions, various balances are struck between culture and economy, theory and method, political purpose and academic professionalism. With these developments, the prospect of a more principled partnership between the ‘warring twins’ (D. Inglis, 2007) could be glimpsed. However, several recent currents of thought and research are undermining the ‘culture and society’ problematic that has sustained most versions of the sociology-cultural studies encounter.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Bibliography

Abell, P. and Reyniers, D. (2000) ‘On the Failure of Social Theory’, British Journal of Sociology 51(4): 739–50.

Article Google Scholar

Abrams, P.; Deem, R.; Finch, J. and Rock, P. (1981) Practice and Progress: British Sociology1950–1980 . London: Allen & Unwin.

Google Scholar

Adkins, L. (2004a) ‘Introduction: Feminism, Bourdieu and After’, in L. Adkins and B. Skeggs (eds), Feminism After Bourdieu . Oxford: Blackwell.

Adkins, L. (2004b) ‘Gender and the Poststructural Social’, in B. Marshall and A. Witz (eds), Engendering the Social: Feminist Encounters with Sociological Theory . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Agger, B. (1992) Cultural Studies as Critical Theory . London: Falmer Press.

Alasuutari, P. (1995) Researching Culture: Qualitative Method and Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Alexander, J.C. (1988a) ‘The New Theoretical Movement’, in N. Smelser (ed.), Handbook of Sociology . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Alexander, J.C. (1988b) ‘Durkheimian Sociology and Cultural Studies Today’, in J.C. Alexander, Structure and Meaning: Relinking Classical Sociology . New York: Columbia University Press.

Alexander, J.C. (2003) The Meanings of Social Life: A Cultural Sociology . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Alexander, J.C. and Thompson, K. (2008) a Contemporary Introduction to Sociology: Culture and Society in Transition . Boulder, CO, and London: Paradigm.

Anderson, P. (1969) ‘Components of the National Culture’, in A. Cockburn (ed.), Student Power . Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Back, L.; Bennett, A.; Edles, L.D.; Gibson, M.; Inglis, D.; Jacobs, R. and Woodward, I. (2012) Cultural Sociology: An Introduction . Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Baetens, J. (2005) ‘Cultural Studies after the Cultural Studies Paradigm’, Cultural Studies 19(1): 1–13.

Baldwin, E.; Longhurst, B.; McCracken, S.; Ogburn, M. and Smith, G. (2004) Introducing Cultural Studies , 2nd edition. London: Prentice Hall.

Barker, C. (2003) Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice , 2nd edition. London: Sage.

Barrett, M.; Corrigan, P.; Kuhn, A. and Wolff, J. (1979) Ideology and Cultural Production , London: Croom Helm/BSA.

Barrett, M. (1980). Women’s Oppression Today: Problems in Marxist-Feminist Analysis . London: Verso.

Barrett, M. (1991) The Politics of Truth: From Marx to Foucault . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Barrett, M. (1992) ‘Words and Things: Materialism and Method in Contemporary Feminist Theory’, in M. Barrett and A. Phillips, Destabilising Theory: Contemporary Feminist Debates . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Barrett, M. (1999) Imagination in Theory: Essays on Writing and Culture . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Barrett, M. (2000) ‘Sociology and the Metaphorical Tiger’, in P. Gilroy, L. Grossberg and A. McRobbie (eds), Without Guarantees: In Honour of Stuart Hall. London: Verso.

Belghazi, T. (1995) ‘Cultural Studies, the University and the Question of Borders’, in B. Adam and S. Allan (eds), Theorizing Culture: An Interdisciplinary Critique After Postmodernism . London: UCL Press.

Bennett, T. (1998) Culture: a Reformer’s Science . London: Sage.

Bland, L.; Brunsdon, C.; Hobson, D. and Winship, J. (1978a) ‘Women “Inside and Outside” the Relations of Production’, in Women’s Studies Group CCCS, Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women’s Subordination . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Bland, L.; Harrison, R.; Mort, F. and Weedon, C. (1978b) ‘Relations of Reproduction: Approaches through Anthropology’, in Women’s Studies Group CCCS, Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women’s Subordination . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Bonnell, V.E. and Hunt, L. (eds) (1999) Beyond the Cultural Turn . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. (1999) ‘On the Cunning of Imperial Reason’, Theory, Culture & Society , 16(1): 41–58.

Bradley, H. and Fenton, S. (1999). ‘Reconciling Culture and Economy: Ways Forward in the Analysis of Ethnicity and Gender’, in L. Ray and A. Sayer (eds), Culture and Economy After the Cultural Turn . London: Sage.

Brantlinger, P. (1990) Crusoe’s Footprints: Cultural Studies in Britain and America . London: Routledge.

Brook, E. and Finn, D. (1978) ‘Working Class Images of Society and Community Studies’, in On Ideology . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Butters, S. (1976) ‘The Logic of Enquiry of Participant Observation: A Critical Review’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Candea, M. (ed.) (2010) The Social After Gabriel Tarde: Debates and Assessments . London: Routledge.

CCCS (1973) ‘Literature/Society: Mapping the Field’, in Culture Studies 4 Literature-Society . Birmingham: CCCS.

CCCS (1981) Unpopular Education: Schooling and Social Democracy in England since 1944 . London: Hutchinson.

Chaney, D. (1994) The Cultural Turn: Scene Setting Essays on Contemporary Cultural History . London: Routledge.

Clarke, J.; Hall, S.; Jefferson, T. and Roberts, B. (1976) ‘Subcultures, Cultures and Class’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Couldry, N. (2000) Inside Culture: Re-Imagining the Method of Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Crane, D. (1994) ‘Introduction: The Challenge of the Sociology of Culture to Sociology as a Discipline’, in D. Crane (ed.), The Sociology of Culture: Emerging Theoretical Perspectives . Oxford: Blackwell.

Critcher, C. (1979) ‘Sociology, Cultural Studies and the Post-War Working Class’, in J. Clarke, C. Critcher and R. Johnson (eds), Working Class Culture: Studies in History and Theory . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Crompton, R. and Scott, J. (2005) ‘Class Analysis: Beyond the Cultural Turn’, in F. Devine, M. Savage, J. Scott and R. Crompton (eds), Rethinking Class: Cultures, Identities and Lifestyles . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Denzin, N.K. (1992) Symbolic Interactionism and Cultural Studies: The Problem of Interpretation . Oxford: Blackwell.

Devine, F. and Savage, M. (2005) ‘The Cultural Turn, Sociology and Class Analysis’, in F. Devine, M. Savage, J. Scott and R. Crompton (eds), Rethinking Class: Cultures, Identities and Lifestyles . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

du Gay, P. (1997) ‘Introduction’, >in P. du Gay et al. (eds), Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman . London: Sage/Open University.

du Gay, P. and Pryke, M. (2002) ‘Cultural Economy: An Introduction’, in P. du Gay and M. Pryke (eds), Cultural Economy . London: Sage.

During, S. (1993) ‘Introduction’, The Cultural Studies Reader . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

During, S. (2005) Cultural Studies: A Critical Introduction . London: Routledge.

Editorial Group (1978) ‘Women’s Studies Group: Trying to do Feminist Intellectual Work’, in Women’s Studies Group CCCS, Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women’s Subordination . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Elliott, A. (ed.) (1999) The Blackwell Reader in Contemporary Social Theory . Oxford: Blackwell.

Elliott, A. (2009) Contemporary Social Theory: An Introduction . London: Routledge.

Evans, M. (2003) Gender and Social Theory . Buckingham, Open University Press.

Ferguson, M. and Golding, P. (eds) (1997) Cultural Studies in Question . London: Sage.

Fraser, N. (2000) ‘Rethinking Recognition’, New Left Review 3: 107–20.

Fulcher, J. and Scott, J. (2004) Sociology , 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gilroy, P. (1982) ‘Steppin’ Out of Babylon - Race, Class and Autonomy’, in CCCS, The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Gray, A. (2003) Research Practice for Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Goldthorpe, J.H. (2004) ‘Book Review Symposium: The Scientific Study of Society’, British Journal of Sociology 55(1): 123–6.

Grossberg, L. (1993) ‘The Formation of Cultural Studies: An American in Birmingham’, in V. Blundell, J. Shepherd and I. Taylor (eds), Relocating Cultural Studies: Developments in Theory and Research . London: Routledge.

Hall, S.; Critcher, C.; Clarke, J.; Jefferson, T. and Roberts, B. (1977) Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order . London: Macmillan.

Hall, S. (1978) ‘The Hinterland of Science: Ideology and the Sociology of Knowledge’, in CCCS, On Ideology . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Hall, S. (1980). ‘Cultural Studies and the Centre: Some Problematics and Problems’, in S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe and P. Willis (eds), Culture, Media, Language . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Hall, S. (1988) The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left . London: Verso.

Hall, S. (1992a) ‘Cultural Studies and its Theoretical Legacies’, in L. Grossberg, C. Nelson and P.A. Treichler (eds), Cultural Studies . New York: Routledge.

Hall, S. (1992b) ‘New Ethnicities’, in J. Donald and A. Rattansi (eds), Race, Culture and Difference . London: Sage.

Hall, S. (1992c) ‘The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power’, in S. Hall and B. Gieben (eds), Formations of Modernity . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hall, S. (1996a) ‘On Postmodernism and Articulation’, in D. Morley and K.H. Chen (eds), Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies . London: Routledge.

Hall, S. (1996b) ‘When was “the Post-colonial”? Thinking at the Limit’, in L. Curti, and I. Chambers (eds), The Post-Colonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons . London: Routledge.

Hall S. (1997a) ‘Introduction’, in S. Hall (ed.), Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices . London: Sage/Open University.

Hall, S. (1997b) ‘The Centrality of Culture: Notes on the Cultural Revolutions of Our Time’, in K. Thompson (ed.), Media and Cultural Regulation . London: Sage/Open University.

Hall, S. (2000) ‘Conclusion: The Multi-Cultural Question’, in B. Hesse (ed.), Un/settled Multiculturalisms . London: Zed Press.

Harris, D. (1992) From Class Struggle to the Politics of Pleasure . London: Routledge.

Hicks, D. (2010) ‘The Material-Cultural Turn: Event and Effect’, in D. Hicks and M.C. Beaudry (eds), Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hicks, D. and Beaudry, M.C. (2010) ‘Introduction’, in D. Hicks and M.C. Beaudry (eds), Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inglis, D. (2007) ‘The Warring Twins: Sociology, Cultural Studies, Alterity and Sameness’, History of the Human Sciences 20(2): 99–122.

Inglis, F. (2004) Culture . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Jessop, B. and Oosterlynck, S. (2008) ‘Cultural Political Economy: On Making the Cultural Turn without falling into soft economic sociology’, Geoforum 39(3): 1155–69.

Johnson, R. (1997) ‘Reinventing Cultural Studies: Remembering for the Best Version’, in E. Long (ed.), From Sociology to Cultural Studies . Oxford: Blackwell.

Johnson, R.; Chambers, D.; Raghuram, P. and Ticknell, E. (2004) The Practice of Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Joyce, P. (ed.) (2002) The Social in Question: New Bearings in History and the Social Sciences . London: Routledge.

Jutel, T. (2004) ‘Lord of the Rings: Landscape, Transformation, and the Geography of the Virtual’, in C. Bell and S. Mathewman (eds), Cultural Studies in Aotearoa New Zealand . Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Kellner, D. (1995) Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity, and Politics between the Modern and the Postmodern . London: Routledge.

Lash, S. (2010) Intensive Culture: Social Theory, Religion and Contemporary Capitalism . London: Sage.

Latour, B. (2002) ‘Gabriel Tarde and the End of the Social’, in P. Joyce (ed.), The Social in Question: New Bearings in History and the Social Sciences . London: Routledge.

Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to ANT . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Law, J. (1999) ‘After ANT: Complexity, Naming and Topology’, in J. Law and J. Hassard (eds), ANT and After . Oxford: Blackwell.

Law, J. (2002) ‘Economics as Interference’, in P. du Gay and M. Pryke (eds), Cultural Economy . London: Sage.

Lawrence, E. (1982) ‘In the Abundance of Water the Fool is Thirsty: Sociology and Black “Pathology”’, in CCCS, The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain. London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Lewis, J. (2003) Cultural Studies: The Basics . London: Sage.

Macionis, J.J. and Plummer, K. (2005) Sociology: A Global Introduction , 3rd edition. Harlow: Pearson Prentice Hall.

McGuigan, J. (1992) Cultural Populism . London: Routledge.

McGuigan, J. (2009) Cool Capitalism . London: Pluto Press.

McLennan, G. (2005) ‘The New American Cultural Sociology: An Appraisal’, Theory, Culture & Society 22(6): 1–18.

McLennan, G. (2006) Sociological Cultural Studies: Reflexivity and Positivity in the Human Sciences . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

McLennan, G. (2013) ‘Postcolonial Critique: The Necessity of Sociology’, Political Power and Social Theory 24: 119–44.

McNay, L. (2004a) ‘Agency and Experience: Gender as a Lived Relation’, in L. Adkins and B. Skeggs (eds), Feminism After Bourdieu . Oxford: Blackwell.

McNay, L. (2004b) ‘Situated Intersubjectivity’, in B. Marshall and A. Witz (eds), Engendering the Social: Feminist Encounters with Sociological Theory . Buckingham: Open University Press.

McRobbie, A. and Garber, J. (1976) ‘Girls and Subcultures: An Exploration’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

McRobbie, A. (1997) Back to Reality? Social Experience and Cultural Studies . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

McRobbie, A. (2005) The Uses of Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Morley, D. (1997). ‘Theoretical Orthodoxies: Textualism, Constructivism and the “New Ethnography” in Cultural Studies’, in M. Ferguson and P. Golding (eds), Cultural Studies in Question . London: Sage.

Morley, D. (2000) ‘Cultural Studies and Common Sense’, in P. Gilroy, L. Grossberg and A. McRobbie (eds), Without Guarantees: In Honour of Stuart Hall. London: Verso.

Morley, D., and Robins, K. (eds) (2001) British Cultural Studies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mulhern, F. (2000) Culture/Metaculture . London: Routledge.

Osborne, T. (2008) The Structure of Modem Cultural Theory . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Osborne, T.; Rose, N. and Savage, M. (2008) ‘Reinscribing British Sociology’, Sociological Review 56(4): 519–34.

Pearson, G. and Twohig, J. (1976) ‘Ethnography Through the Looking Glass: the Case of Howard Becker’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Pickering, A. (ed.) (1992) Science as Practice and Culture . Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Ray, L. (2003) ‘Foreword’, in B. Smart, Economy, Culture and Society: A Sociological Critique of Neo-liberalism . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Ray, L. and Sayer, A. (eds) (1999) Culture and Economy After the Cultural Turn . London: Sage.

Reed, I. and Alexander, J.C. (eds) (2009) Meaning and Method: the Cultural Approach to Sociology . Boulder, CO, and London: Paradigm.

Roberts, B. (1976) ‘Naturalistic Research into Subcultures and Deviance: An Account of a Sociological Tendency’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Rojek, C. (1985) Capitalism and Leisure Theory . London: Tavistock.

Rojek, C. (1992) ‘The Field of Play in Sport and Leisure Studies’, in E. Dunning and C. Rojek (eds), Sport and Leisure in the Civilizing Process: Critique and Counter-Critique . Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Rojek, C. and Turner, B. (2000) ‘Decorative Sociology: Towards a Critique of the Cultural Turn’, Sociological Review 48(4): 629–48.

Rojek, C. (2003) Stuart Hall . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Roseneil, S. and Frosh, S. (eds) (2012) Social Research After the Cultural Turn . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Savage, M. (2012) ‘The Politics of Method and the Challenge of Digital Data’, in S. Roseneil and S. Frosh (eds), Social Research After the Cultural Turn . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sayer, A. (2005) The Moral Significance of Class . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schwarz, B. (2005) Review of Rojek, ‘Stuart Hall’, Cultural Studies 19(2): 176–202.

Skeggs, B. (2004) Class, Self, Culture . London: Routledge.

Skeggs, B. (2005) ‘The Re-branding of Class: Propertizing Culture’, in F. Devine, M. Savage, J. Scott and R. Crompton (eds), Rethinking Class: Cultures, Identities and Lifestyles . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Silva, E. and Warde, A. (eds) (2010). Cultural Analysis and Bourdieu’s Legacy: Settling Accounts and Developing Alternatives . London: Routledge.

Smart, B. (2003) Economy, Culture and Society: A Sociological Critique of Neo-Liberalism . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Smelser, N. (1992) ‘Culture: Coherent or Incoherent?’, in R. Munch and N.J. Smelser (eds), Theory of Culture . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Smith, Paul (2000) ‘Looking Backwards and Forwards at Cultural Studies’, in T. Bewes and J. Gilbert (eds), Cultural Capitalism: Politics After New Labour . London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Storey, J. (2001) Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: An Introduction . Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Stratton, J. and Ang, I. (1996). ‘On the Impossibility of a Global Cultural Studies’, in D. Morley and K.H. Chen (eds), Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies . London: Routledge.

Tester, K. (1994) Media, Culture and Morality . London: Routledge.

Thrift, N. (2005) Knowing Capitalism . London: Sage.

Thrift, N. (2008) Non-representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect . London: Routledge.

Tomlinson, J. (2012) ‘Cultural Analysis’, G. in Ritzer (ed.), Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Sociology . London: John Wiley.

Turner, B.S. and Rojek, C. (2001) Society and Culture: Principles of Scarcity and Solidarity . London: Sage.

Turner, G. (1990) British Cultural Studies . Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman.

White, M. and Schwoch, J. (2006) ‘Introduction’, in M. White and J. Schwoch (eds), Questions of Method in Cultural Studies . Oxford: Blackwell.

Willis, P. (1977) Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids get Working Class Jobs . Farnborough: Saxon House.

Willis, P. (1980) ‘Notes on Method’, in S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe and P. Willis (eds), Culture, Media, Language . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Willis, P. (2003) ‘Introduction’, in C. Barker, Cultural Studies: Theoty and Practice , 2nd edition. London: Sage.

Witz, A. and Marshall, B.L. (2004) ‘The Masculinity of the Social: Towards a Politics of Interrogation’, in B.L. Marshall and A. Witz (eds), Engendering the Social . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Wolff, J. (1999) ‘Cultural Studies and the Sociology of Culture’, Contemporary Sociology 28(5): 499–507.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Nottingham, UK

John Holmwood

University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Copyright information

© 2014 Gregor McLennan

About this chapter

McLennan, G. (2014). Sociology, Cultural Studies and the Cultural Turn. In: Holmwood, J., Scott, J. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Sociology in Britain. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137318862_23

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137318862_23

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-33548-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-31886-2

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social Sciences Collection Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Cultural Studies

Cultural Studies

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on November 23, 2016 • ( 5 )

Arising from the social turmoil of the 1960-s, Cultural Studies is an academic discipline which combines political economy, communication, sociology, social theory, literary theory, media theory, film studies, cultural anthropology, philosophy, art history/ criticism etc. to study cultural phenomena in various societies. Cultural Studies researches often focus on how a particular phenomenon relates matters of ideology, nationality, ethnicity, social class and gender.

Discussion on Cultural Studies have gained currency with the publication of Richard Hoggart’s Use of Literacy (1957) and Raymond Williams’ Culture and Society (1958), and with the establishment of Birmingham Centre for is Contemporary Cultural Studies in England in 1968.

Since culture is now considered as the source of art and literature, cultural criticism has gained ground, and therefore, Raymond Williams’ term “cultural materialism”, Stephen Greenblatt’s “cultural poetics” and Bakhtin’s term “cultural prosaic”, have become significant in the field of Cultural Studies and cultural criticism.

The works of Stuart Hall and Richard Hoggart with the Birmingham Centre, later expanded through the writings of David Morley, Tony Bennett and others. Cultural Studies is interested in the process by which power relations organize cultural artefacts (food habits, music, cinema, sport events etc.). It looks at popular culture and everyday life, which had hitherto been dismissed as “inferior” and unworthy of academic study. Cultural Studies’ approaches 1) transcend the confines of a particular discipline such as literary criticism or history 2) are politically engaged 3) reject the distinction between “high” and “low” art or “elite” and “popular” culture 4) analyse not only the cultural works but also the means of production.

In order to understand the changing political circumstances of class, politics and culture in the UK, scholars at the CCCS turned to the work of Antonio Gramsci who modified classical Marxism in seeing culture as a key instrument of political and social control. In his view, capitalists are not only brute force (police, prison, military) to maintain control, but also penetrate the everyday culture of working people. Thus the key rubric for Gramsci and for cultural studies is that of cultural hegemony. Edgar and Sedgwick point out that the theory of hegemony was pivotal to the development of British Cultural Studies. It facilitated analysis of the ways in which subaltern groups actively resist and respond to political and economic domination.

The approach of Raymond Williams and CCCS was clearly marxIst and poststructuralist, and held subject identities and relationships as textual, constructed out of discourse. Cultural Studies believes that we cannot “read” cultural artefacts only within the aesthetic realm, rather they must be studied within the social and material perspectives; i.e., a novel must be read not only within the generic conventions and history of the novel, but also in terms of the publishing industry and its profit, its reviewers, its academic field of criticism, the politics of awards and the hype of publicity machinery that sells the book. Cultural Studies regards the cultural artefact like the tricolour or Gandhi Jayanti as a political sign, that is part of the “discourse” of India, as reinforcing certain ideological values, and concealing oppressive conditions of patriarchal ideas of the nation, nationalism and national identity.

In Cultural Studies, representation is a key concept and denotes a language in which all objects and relationships get defined, a language related to issues of class, power and ideology, and situated within the context of “discourse”. The cultural practice of giving dolls to girls can be read within the patriarchal discourse of femininity that girls are weaker and delicate and need to be given soft things, and that grooming, care etc. are feminine duties which dolls will help them learn. This discourse of femininity is itself related to the discourse of masculinity and the larger context of power relations in culture. Identity, for Culture Studies, is constituted through experience, which involves representation – the consumption of signs, the making of meaning from signs and the knowledge of meaning.

Cultural Studies views everyday life as fragmented, multiple, where meanings are hybridized and contested; i.e., identities that were more or less homogeneous in terms of ethnicities and patterns of consumption, are now completely hybrid, especially in the metropolis. With the globalization of urban spaces, local cultures are linked to global economies, markets and needs, and hence any study of contemporary culture has to examine the role of a non-local market/ money which requires a postcolonial awareness of the exploitative relationship between the First World and the Third World even today.

Cultural Studies is interested in lifestyle because lifestyle 1) is about everyday life 2) defines identity 3) influences social relations 4) bestows meaning and value to artefacts in a culture. In India, after economic liberalization, consumption has been seen as a marker of identity. Commodities are signs of identity and lifestyle and consumption begins before the actual act of shopping; it begins with the consumption of the signs of the commodity.

Mall Culture

Mall is a space of display where goods are displayed for maximum visual display in such a fashion that they are attractive enough to instill desire. Spectacle, attention- holding and desire are central elements of shopping experience in the mall. Hence mall emerges primarily as a site of gazing and secondarily as a site of shopping. The mall presents a spectacle of a fantasy world created by the presence of models and posters, compounded by the experience of being surrounded by attractive men and women, cosy families and vibrant youth — which altogether entice us to unleash the possibilities of donning a better identity, by trying out / consuming global brands and cosmopolitan fashion.

The mall invites for participating in the fantasy of future possibilities. Thus, the spectacle turns into a performance that the customer/ consumer imitates and participates in. It is also a theatrical performance that is interactive, in which the spectacle comes alive with the potential consumer. The encircling vistas, long-spread balconies and viewing points at every floor add to the spectacle, by providing a “prospect” of shopping.

Eclecticism is yet another feature of the mall, where, “the world is under one roof”- where a “Kalanjali” or “Mann Mantra” share space with “Shoppers Stop” or “Life Style” and “Madras Mail” shares space with “McDonald’s” and multiplexes, imparting a cosmopolitan experience. Thus eclecticism and a mixing of products, styles and traditions are a central feature of the mall and consumer experience.

Further, “the mall is a hyperreal, ahistorical, secure, postmodern-secular, uniform space of escape that takes the streets of the city into itself in a tightly controlled environment where time, weather, season do not matter where the “natural” is made through artificial lighting and horticulture, and ensuring that this public space resembles the city but offers more security and choice”

Media Culture

Media studies and its role in the construction of cultural values, circulation of symbolic values, and its production of desire are central to Cultural Studies today. Cultural Studies of the media begins with the assumption that media culture is political and ideological, and it reproduces existing social values, oppression and inequalities. Media culture clearly reflects the multiple sides of contemporary debates and problems. Media culture helps to reinforce the hegemony and power of specific economic, cultural and political groups by suggesting ideologies that the audience, if not alert, imbibes. Media culture is also provocative because it sometimes asks us to rethink what we know or believe in. In Cultural Studies, media culture is studied through an analysis of popular media culture like films, TV serials, advertisements etc.- as Cultural Studies believes in the power of the popular cultural forms as tools of ideological and political power.

Cultural Studies of popular media culture involves an analysis of the forms of representation, such as film; the political ideology of these representations; an examination of the financial sources/sponsors of these representations (propaganda advertisements by Coke after the report on pesticides in Coca Cola); an examination of the roles played by other objects / people in the propagating ideology (Amir Khan in the Coca Cola ad, after patriotic films like Lagaan, Mangal Pandey and Rang de Basanti). Cultural Studies also analyses whether the medium (say, film), presents an oppressive/unequal nature of institutions, like family, education etc. or glorify them; the possible resistance to such oppressive ideologies; the audience’s response to such representation and the economic benefits and the beneficiaries of such representations.

Contemporary Culture Studies of media culture explores what is called “media ecologies”, the environment of human culture created by the intersection of information and communications technologies, organizational behaviour and human interaction.

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: Antonio Gramsci , cultural hegemony , Cultural Studies , Cultural Studies Essay , Cultural Studies key terms , Cultural Studies key theorists , Cultural Studies main ideas , Culture and Society , David Morley , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Mall Culture , media ecologies , Popular Culture , Raymond Williams , Richard Hoggart , Stephen Greenblatt , Stuart Hall , Tony Bennett

Related Articles

Hi! Please can you provide me with citations for the quotes you include in the section on Mall Culture? thank you!

https://www.ijelr.in/3.3.16/17-19%20JUBINAROSA.S.S.pdf

- Key Theories of Raymond Williams – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Anthropological Criticism: An Essay – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- High Culture and Popular Music – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Cultural Culture in Peru

This essay about the culture of Peru explores the rich diversity of the nation’s history, highlighting its indigenous roots, Spanish colonial influence, and modern global interactions. It discusses the significant impact of ancient civilizations like the Incas and their contributions to the current linguistic, agricultural, and artistic practices. The essay emphasizes the syncretism in religious celebrations, showcasing a blend of indigenous and Spanish traditions, particularly visible in festivals and culinary practices. Peruvian cuisine, a fusion of native and global influences, and the arts, including weaving and literature, are also explored as vital expressions of Peru’s cultural identity. The summary underscores how these elements combine to create a dynamic, diverse cultural landscape in Peru, reflecting both the preservation of tradition and the embrace of modernity.

How it works

The culture of Peru stands as a profound tapestry woven with the threads of its ancient civilizations and Spanish colonial history, infused with modern influences. This blend has created a unique cultural identity that is both diverse and richly complex, reflecting the various ethnic groups and their histories within Peru’s borders.

Peruvian culture is perhaps best known through its most iconic symbols, such as the ancient Inca city of Machu Picchu, which is just one part of the country’s vast archaeological heritage.

The Incas, famous for their stone architecture and road systems, were just the culmination of a long line of sophisticated societies such as the Moche, the Nazca, and the Chimu, which inhabited Peru’s territory long before the Spanish conquest. The legacies of these cultures are not just preserved in their monumental ruins but in the continuation of their artistic techniques, agricultural practices, and even in the Quechua and Aymara languages spoken by descendants today.

Spanish colonial rule, which began in the 16th century, introduced new architectural forms, art styles, and the Spanish language, which became the dominant language of the country. However, indigenous influences persisted, and today, Peru is a bilingual nation with Quechua also recognized as an official language. This blend of native and Spanish elements is most vividly reflected in the celebration of religious festivals. Festivities such as “Inti Raymi,” an Inca festival celebrating the sun god, and the Christian “Semana Santa” (Holy Week), showcase this syncretism with elaborate costumes, traditional music, and public processions.

Peruvian cuisine is another area where cultural diversity is celebrated. Ingredients used by ancient Peruvians, such as potatoes, maize, and chili peppers, have been integrated with Spanish, African, Asian, and Italian influences to create a unique culinary tradition. Dishes like ceviche (marinated seafood), lomo saltado (stir-fried beef), and aji de gallina (creamy chicken) highlight these diverse influences. Additionally, the traditional Andean practice of terrace farming continues to be vital, both as a cultural heritage and for cultivating indigenous crops like quinoa and various potato varieties.

The arts in Peru are as varied as its festivals and foods. Weaving and pottery carry on indigenous traditions, often incorporating symbols and techniques that date back thousands of years. Meanwhile, literature has been a powerful vehicle for expressing and reflecting on Peru’s complex identity, with authors such as Mario Vargas Llosa, a Nobel laureate, using the nation’s history and social issues as backdrops for his narratives.

In contemporary times, Peru has embraced globalization, yet it continues to hold on to its traditions, making it a compelling study of cultural retention and transformation. Migration has also influenced urban culture, particularly in Lima, where influences from around the world have melded with indigenous and colonial traditions to create a vibrant, dynamic urban culture. This phenomenon is seen in the proliferation of art galleries, festivals, and the urban music scene, which blends traditional Peruvian styles with modern genres like rock and hip hop.

In conclusion, the culture of Peru is characterized by a depth of history and a richness of ongoing cultural practice. From its ancient civilizations to its current global interactions, Peru’s culture is a vibrant mosaic of the old and new, offering a unique glimpse into the past and present of its people. This cultural wealth not only attracts tourists from around the globe but also instills a sense of pride and identity among Peruvians.

Remember, this essay is a starting point for inspiration and further research. For more personalized assistance and to ensure your essay meets all academic standards, consider reaching out to professionals at [EduBirdie](https://edubirdie.com/?utm_source=chatgpt&utm_medium=answer&utm_campaign=essayhelper).

Cite this page

Cultural Culture In Peru. (2024, Apr 22). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/cultural-culture-in-peru/

"Cultural Culture In Peru." PapersOwl.com , 22 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/cultural-culture-in-peru/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Cultural Culture In Peru . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/cultural-culture-in-peru/ [Accessed: 28 Apr. 2024]

"Cultural Culture In Peru." PapersOwl.com, Apr 22, 2024. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/cultural-culture-in-peru/

"Cultural Culture In Peru," PapersOwl.com , 22-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/cultural-culture-in-peru/. [Accessed: 28-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Cultural Culture In Peru . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/cultural-culture-in-peru/ [Accessed: 28-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What It Means To Be Asian in America

The lived experiences and perspectives of asian americans in their own words.

Asians are the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the United States. More than 24 million Americans in the U.S. trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

The majority of Asian Americans are immigrants, coming to understand what they left behind and building their lives in the United States. At the same time, there is a fast growing, U.S.-born generation of Asian Americans who are navigating their own connections to familial heritage and their own experiences growing up in the U.S.

In a new Pew Research Center analysis based on dozens of focus groups, Asian American participants described the challenges of navigating their own identity in a nation where the label “Asian” brings expectations about their origins, behavior and physical self. Read on to see, in their own words, what it means to be Asian in America.

- Introduction

Table of Contents

This is how i view my identity, this is how others see and treat me, this is what it means to be home in america, about this project, methodological note, acknowledgments.

No single experience defines what it means to be Asian in the United States today. Instead, Asian Americans’ lived experiences are in part shaped by where they were born, how connected they are to their family’s ethnic origins, and how others – both Asians and non-Asians – see and engage with them in their daily lives. Yet despite diverse experiences, backgrounds and origins, shared experiences and common themes emerged when we asked: “What does it mean to be Asian in America?”

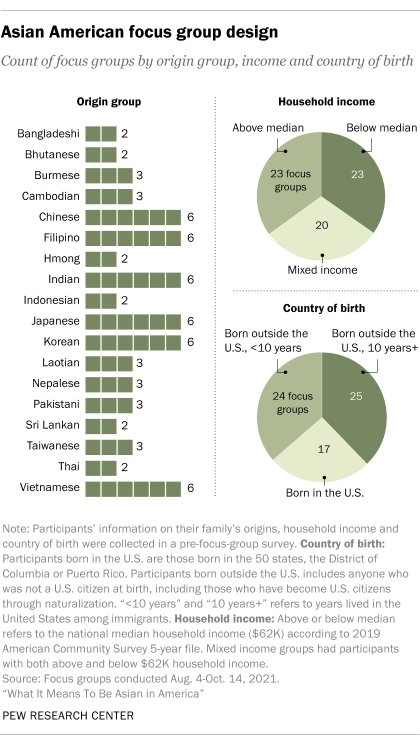

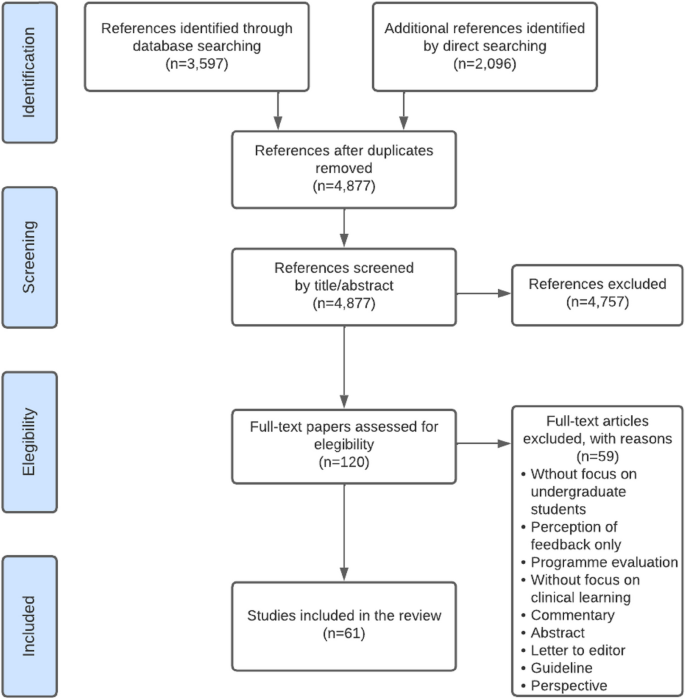

In the fall of 2021, Pew Research Center undertook the largest focus group study it had ever conducted – 66 focus groups with 264 total participants – to hear Asian Americans talk about their lived experiences in America. The focus groups were organized into 18 distinct Asian ethnic origin groups, fielded in 18 languages and moderated by members of their own ethnic groups. Because of the pandemic, the focus groups were conducted virtually, allowing us to recruit participants from all parts of the United States. This approach allowed us to hear a diverse set of voices – especially from less populous Asian ethnic groups whose views, attitudes and opinions are seldom presented in traditional polling. The approach also allowed us to explore the reasons behind people’s opinions and choices about what it means to belong in America, beyond the preset response options of a traditional survey.

The terms “Asian,” “Asians living in the United States” and “Asian American” are used interchangeably throughout this essay to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

“The United States” and “the U.S.” are used interchangeably with “America” for variations in the writing.

Multiracial participants are those who indicate they are of two or more racial backgrounds (one of which is Asian). Multiethnic participants are those who indicate they are of two or more ethnicities, including those identified as Asian with Hispanic background.

U.S. born refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, or other U.S. territories.

Immigrant refers to people who were not U.S. citizens at birth – in other words, those born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who were not U.S. citizens. The terms “immigrant,” “first generation” and “foreign born” are used interchangeably in this report.

Second generation refers to people born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia with at least one first-generation, or immigrant, parent.

The pan-ethnic term “Asian American” describes the population of about 22 million people living in the United States who trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The term was popularized by U.S. student activists in the 1960s and was eventually adopted by the U.S. Census Bureau. However, the “Asian” label masks the diverse demographics and wide economic disparities across the largest national origin groups (such as Chinese, Indian, Filipino) and the less populous ones (such as Bhutanese, Hmong and Nepalese) living in America. It also hides the varied circumstances of groups immigrated to the U.S. and how they started their lives there. The population’s diversity often presents challenges . Conventional survey methods typically reflect the voices of larger groups without fully capturing the broad range of views, attitudes, life starting points and perspectives experienced by Asian Americans. They can also limit understanding of the shared experiences across this diverse population.

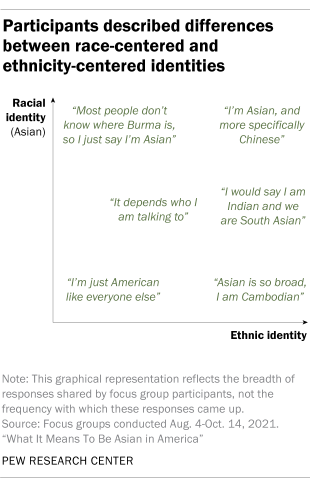

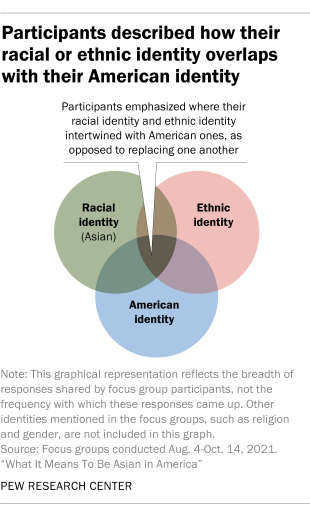

Across all focus groups, some common findings emerged. Participants highlighted how the pan-ethnic “Asian” label used in the U.S. represented only one part of how they think of themselves. For example, recently arrived Asian immigrant participants told us they are drawn more to their ethnic identity than to the more general, U.S.-created pan-ethnic Asian American identity. Meanwhile, U.S.-born Asian participants shared how they identified, at times, as Asian but also, at other times, by their ethnic origin and as Americans.

Another common finding among focus group participants is the disconnect they noted between how they see themselves and how others view them. Sometimes this led to maltreatment of them or their families, especially at heightened moments in American history such as during Japanese incarceration during World War II, the aftermath of 9/11 and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond these specific moments, many in the focus groups offered their own experiences that had revealed other people’s assumptions or misconceptions about their identity.

Another shared finding is the multiple ways in which participants take and express pride in their cultural and ethnic backgrounds while also feeling at home in America, celebrating and blending their unique cultural traditions and practices with those of other Americans.

This focus group project is part of a broader research agenda about Asians living in the United States. The findings presented here offer a small glimpse of what participants told us, in their own words, about how they identify themselves, how others see and treat them, and more generally, what it means to be Asian in America.

Illustrations by Jing Li

Publications from the Being Asian in America project

- Read the data essay: What It Means to Be Asian in America

- Watch the documentary: Being Asian in America