Nursing Care for Transgender Patients: Tips and Resources

NurseJournal.org is committed to delivering content that is objective and actionable. To that end, we have built a network of industry professionals across higher education to review our content and ensure we are providing the most helpful information to our readers.

Drawing on their firsthand industry expertise, our Integrity Network members serve as an additional step in our editing process, helping us confirm our content is accurate and up to date. These contributors:

- Suggest changes to inaccurate or misleading information.

- Provide specific, corrective feedback.

- Identify critical information that writers may have missed.

Integrity Network members typically work full time in their industry profession and review content for NurseJournal.org as a side project. All Integrity Network members are paid members of the Red Ventures Education Integrity Network.

Explore our full list of Integrity Network members.

Are you ready to earn your online nursing degree?

One responsibility of healthcare providers involves creating a welcoming and nonjudgmental environment for every patient. Still, transgender individuals — people whose gender is different than the one assigned at birth — and gender nonconforming (GNC) patients continue to face challenges and prejudice in healthcare settings.

Nurses have an especially important role in providing an affirming space for transgender people. Many patients confide in nurses, sometimes finding them more trustworthy than physicians. In fact, nursing has consistently ranked as the most honest and ethical profession for the past two decades, according to Gallup polls .

More and more nurses wish to provide a comfortable environment for all their patients, including those who are transgender or GNC. However, this can feel challenging for nurses without a great deal of experience caring for this community, especially because they have not had adequate or appropriate educational resources.

This guide aims to help nurses better understand the transgender and GNC community, the hurdles they might face in healthcare, and helpful steps on working with transgender and GNC patients.

Healthcare Barriers to Transgender Patients

For many transgender patients, healthcare can be an intimidating — and often inaccessible — environment.

Transgender people are more likely to be uninsured than cisgender patients, those who are gendered correctly at birth or those who are not transgender. This can restrict their access to healthcare with high costs. According to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Fund , 19% of transgender adults reported not possessing health insurance compared to 12% of the cisgender population. Another 19% reported encountering cost-related barriers to receiving care. Only 13% of cisgender adults encountered these barriers.

For instance, without the sensitivity and consideration needed to communicate concerns relating to transgender patients, some healthcare providers may accidentally out transgender patients to their families and friends, risking the patient’s health and safety.

In addition to emotional and financial barriers, transgender people also face outdated polices and processes modeled for heterosexual and cisgender patients.

According to Desiree Díaz, Ph.D., associate professor at University of Central Florida’s College of Nursing , these distressing experiences can lead to transgender people avoiding necessary appointments and procedures.

“Transgender patients often delay care due to past experiences when attempting to access care,” Díaz says.

Healthcare Biases and Discrimination

Often healthcare providers do not intentionally or maliciously misgender patients or make them feel alienated. The problem roots from broader systemic issues, meaning, among many things, that some nurses and other healthcare professionals have been socialized or taught to believe that being transgender or GNC is wrong so they might not want to treat or support trans and GNC patients.

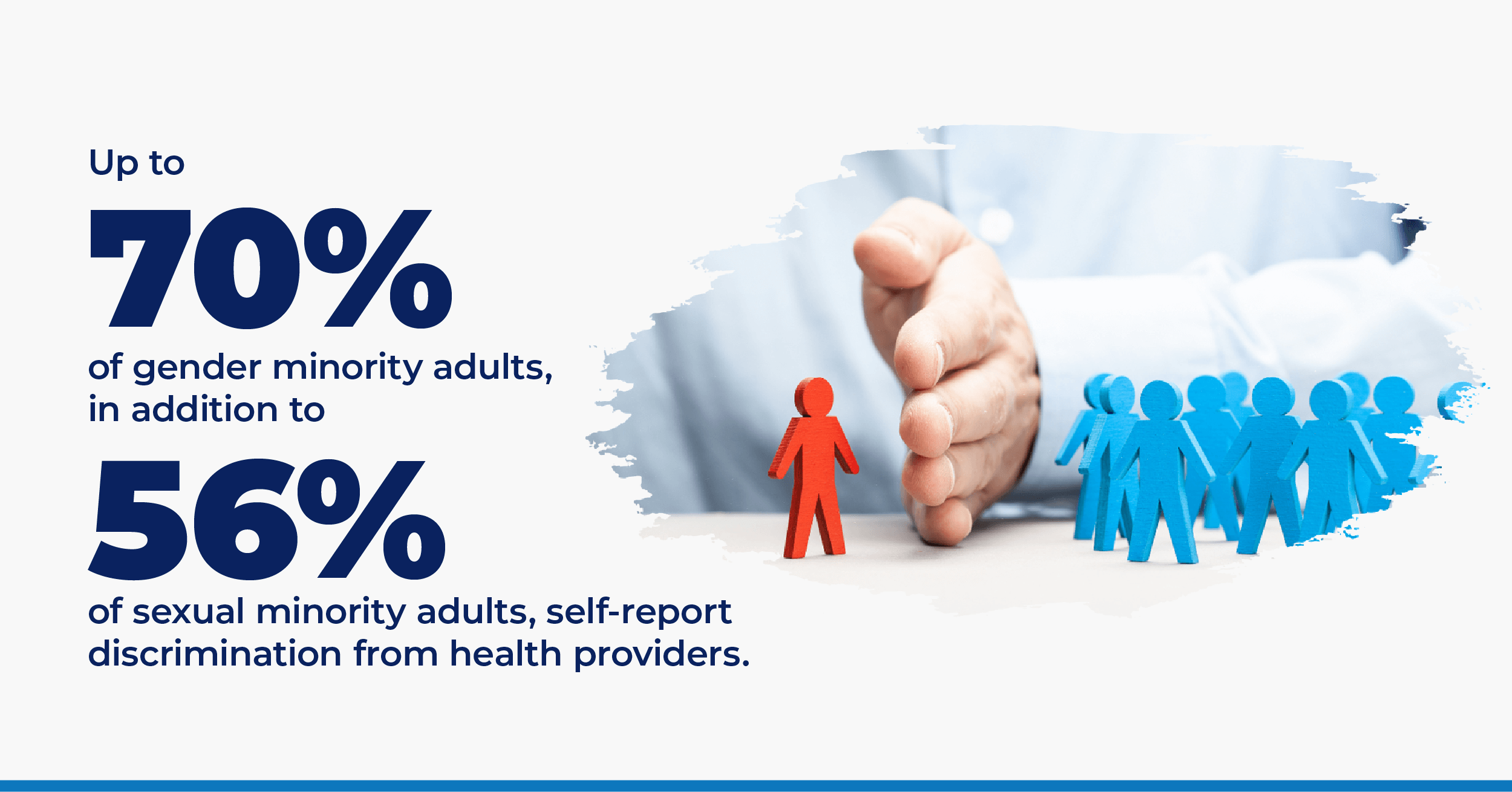

Another systemic issue is that the healthcare system can disproportionately harm trans and GNC patients due to biases, stigmatization, and outdated policies. Even those who do wish to provide competent care do not necessarily have the training to adequately care for transgender patients.

Additionally, broad-based hostility and discrimination can limit the number of transgender and GNC people who pursue a nursing career which would bring lived experience to the field. Systemic issues have also resulted in a lack of research on transgender patients in healthcare.

— “I believe that there are many nurses and providers who want to do the right thing and provide affirming care, but don’t have the support of their organization for training,” says Kristie Overstreet, Ph.D., who works as a clinical sexologist, psychotherapist, and LGBTQIA+ healthcare expert.

Greater education and training for working with transgender and GNC people is one solution to this problem. Another is acknowledging biases, then taking action to eliminate or lessen the potential harm those biases can cause.

For example, healthcare providers may make assumptions because of internal biases that can lead to mistakes about medical transitioning or taking sex and gender as the same. Some transgender people face more direct discrimination, such as providers refusing to treat them or calling them by a legal name they do not use because of the providers’ personal beliefs.

Considerations for Creating a More Supportive Environment

Once nurses understand their own biases and learn more about transgender and GNC individuals, they can take steps to provide affirming healthcare spaces for people in these communities. Remember: Each person and their individual situation is unique, so consider these considerations as general guidelines.

“In general, it is not acceptable to ask about people’s genitals or gender-affirming surgeries or hormone therapy or other details about medical or nonmedical transition, or lack of transition,” explains Dasuqi.

If these details are directly relevant to a patient’s care, ask in a careful and sensitive manner. Do not share this information with other healthcare staff unless it is medically necessary.

“Healthcare staff should assume this information is very personal and should inform patients ahead of time when it will be necessary to share information about their body to other healthcare providers for the purpose of medical treatment,” Dasqui says.

Ask open-ended questions, but make sure you do so in a direct but sensitive way. You can ask about a person’s gender, but be mindful how you ask about their sex.

“More direct questions that are relevant are often more appropriate,” Dasuqi advises, “such as ‘can you tell me more about what kind of genitalia you have and the symptoms you are experiencing there.'”

If you are unsure about something regarding a person’s gender, seek clarification instead of making assumptions.

Make note of your patient’s pronouns.

Use the terms your patient uses when referring to themselves and their partner(s). Your patient may use he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/them/theirs — even if they present more stereotypically feminine or masculine. Others may use less common pronouns like ze/hir/hirs or ze/zir/zirs, so always ask before addressing them.

You can also make transgender and GNC patients feel more comfortable by introducing yourself with your own pronouns.

“Because most forms still require healthcare workers to fill out the sex of an individual, they should know that this question can be painful or triggering for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals to answer,” says Dasuqi, adding that nurses and healthcare workers should be ready to offer support and understanding in these situations.

Sometimes, a patient’s name and gender may not match what is listed on their insurance or medical records. Should you need to cross-check a patient’s identification information, never ask what their “real” or given name is. Instead, the LGBT National Health Education Center recommends asking the patient what the name on their insurance is and confirming their date of birth and address, then continuing to address them by the name they originally provided.

You can find a guide on how to do so here , and templates here from the National LGBT Health Education Center.

As Overstreet says, “A patient’s gender identity is one part of them, so be sure to care for them as a whole person and not inflate or narrow their identity.”

In other words, consider a patient’s transgender or GNC identity within their larger cultural, emotional, physical, and psychological being.

“Cultural congruence is important when caring for all people but specifically the LGBTQ+ population,” Díaz adds. “This means understanding how culture pertains to … respecting the intersection.”

If you hear your coworkers misgendering patients or making transphobic comments, do not be afraid to speak up. You can also be a patient advocate on issues like gender confirmation surgery and fertility treatments.

Key Terms and Concepts

Keep some key terms and concepts in mind when working with members of the LGBTQ+ community. The following list comes from Overstreet who has trained healthcare practitioners on best practices in LGBTQIA+ wellness and care. The list is not exhaustive, and terms may vary across communities and cultures. To learn about more terms, visit this resource from the Human Rights Campaign .

- Cisgender: Someone who is not transgender (‘cis’)

- Transgender: Someone who does not identify with their sex assigned at birth (‘trans’)

- Nonbinary: Someone who does not identify as exclusively a man or woman, identifies as a mix of genders, or has no gender at all; does not conform to gender expectations

- Crossdresser: Someone who wears clothing typical for a different gender

- Drag king or queen: Someone who performs for entertainment purposes (may or may not be transgender)

- Agender or genderless: No gender identity or expression (sometimes interchangeable with gender-neutral)

- Genderqueer: Someone who does not identify within the gender binary

- Bigender: Having two gender identities or expressions, either simultaneously, at different times, or in different situations

- Intersex: An “umbrella” term for someone who is born with general sex characteristics (genitals, gonads, and chromosome patterns) that do not fit typical binary male or female bodies; they have a wide range of bodily variations, which do not always show up at birth

- Lesbian: Female of any gender identity who is emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to other females

- Gay: A person who is emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to members of the same gender identity or expression (for example, a gay male or gay person)

- Bisexual: A person who is emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to more than one sex, gender, or gender identity; capacity for attraction for all genders (note: do not get confused with ‘bi’ which reinforces the binary)

- Queer: A multifaceted word that is used in different ways and has different definitions, including sexual and gender identities other than straight and cisgender

- Asexual: Lack of sexual attraction or desire for other people; may have romantic attraction

- Pansexual: Someone who has the potential for emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to people of any gender identity or expression; this is a more inclusive term (note: “bisexual” and “pansexual” are not interchangeable for all people)

- Gender Dysphoria: A distressed state arising from the conflict between a person’s gender identity and the sex the person has or was assigned at birth

For more information, see our guide to LGBTQIA2S+ Key Terms and Definitions for Nurses and Healthcare Providers .

Creating More Equitable and Gender-Affirming Care in Nursing

“Health equity is the most important concept. It is about providing safe care to all people regardless of sexual preference, orientation, or identity,” Díaz says.

Equity within the healthcare space requires buidling a safe, nonthreatening environment for all patients, including those who are transgender. The ultimate goal, according to Dasuqi, is creating a healthcare system in which transgender patients would not have to worry about being treated like special cases.

“It is about shifting the systems and social conditioning on wider levels to include the trans and GNC experience as part of what is normal, rather than always an exception,” Dasuqi concludes.

Helpful Resources for Nurses

National lgbtqia+ health education center, centers for disease control and prevention, national clinician consultation center, university of california, san francisco – transgender care, glma – health professionals advancing lgbtq equality, meet our contributors.

Kristie Overstreet, Ph.D.

Kristie Overstreet, Ph.D., is a clinical sexologist, psychotherapist, LGBTQIA+ healthcare expert, host of the “Fix Yourself First” podcast, and author of “Fix Yourself First: 25 Tips to Stop Ruining Your Relationships.” She is the creator of The Transgender Dignity Model , which provides LGBTQIA+ training for healthcare professionals.

She has been featured in Forbes, Huffington Post, Cosmopolitan, New York Magazine, Oprah Magazine, The Washington Post, on CNN, and various other media outlets.

Ash Dasuqi, CPM, RN

Ash Dasuqi, CPM, RN, is a trans genderqueer midwife, childbirth educator, critical care nurse, and parent. They created a trauma-informed, evidence-based childbirth preparation curriculum called the Embodied Birth Class that is open to all people while centering the experience of first-time pregnant and birthing queer/transgender individuals.

Desiree Díaz, Ph.D.

Desiree Díaz, Ph.D., is an associate professor of the University of Central Florida’s College of Nursing . One of the world’s first 22 certified advanced healthcare simulation educators, Díaz focuses her research on using the cutting-edge technology of simulation to improve the care for underserved patient populations in an effort to reduce healthcare disparities. Recognizing her contributions to nursing science and education, she has been inducted as a fellow of both the American Academy of Nursing and the Academy of Nursing Education.

Reviewed by:

Angelique Geehan

A queer Asian gender-binary nonconforming parent, Angelique Geehan founded Interchange , a consulting group that offers anti-oppression support through materials and process assessments, staff training, and community building. Geehan works to support and repair the connections people have to themselves and their families, communities, and cultural practices.

She organizes as a part of National Perinatal Association’s Health Equity Workgroup, the Health and Healing Justice Committee of the National Queer and Trans Asian and Pacific Islander Alliance, the Houston Community Accountability and Transformative Justice Collective, the Taking Care Study Group, QTPOC+ Family Circle, and Batalá Houston.

Geehan is a paid member of our Healthcare Review Partner Network. Learn more about our review partners .

Related LGBTQ+ Resources

LGBTQIA2S+ Key Terms & Definitions for Nurses & Healthcare Providers

Nurses can use this glossary of terms to help improve their ability to communicate with LGBTQIA2S+ patients and their families. Excellent nursing care requires practitioners to learn about their patients, so while knowing terms does not guarantee excellence, it can help build toward that.

LGBTQ+ Care: Training and Resources for Nurses

Expand your skill set and cultural competency working with LGBTQ+ patients with these free or low-cost continuing education and training courses.

Scholarships for LGBTQ+ College Students

Several public and private organizations offer scholarships for LGBTQ+ college students. Use this guide to help you research undergraduate and graduate funding opportunities for LGBTQ+ applicants.

Feature Image: FG Trade / E+ / Getty Images

Whether you’re looking to get your pre-licensure degree or taking the next step in your career, the education you need could be more affordable than you think. Find the right nursing program for you.

You might be interested in

HESI vs. TEAS Exam: The Differences Explained

Nursing schools use entrance exams to make admissions decisions. Learn about the differences between the HESI vs. TEAS exams.

10 Nursing Schools That Don’t Require TEAS or HESI Exam

For Chiefs’ RB Clyde Edwards-Helaire, Nursing Runs in the Family

Nursing Care For Transgender Patients

The transgender dilemma, create a supportive environment.

- Patient-Led Care

- Understand the Process

- Understand the Patient

- Community Support

Laverne Cox. Caitlyn Jenner. Amazon’s series Transparent .

Transgender issues are becoming more visible in pop culture, and in real life and healthcare, too.

The New York Times reported that the number of people who identify as transgender has doubled since 2011.

Those numbers are already showing up in healthcare facilities nationwide.

So don’t be surprised if a transgender male seeks an appointment for his annual pap smear.

As healthcare providers , a recent challenge is providing equal and unbiased care to transgender patients.

Historically, that hasn’t happened.

As a nurse, how will you handle your next patient’s mammogram if she was born a man?

Oncology Nurses are in high demand. Search open positions now.

Transgender patients often avoid care.

The fear of discrimination, lower quality of care, and lack of insurance access can be paralyzing.

Just entering your doors takes courage.

Ask yourself how you could reward that courage with an open and nonjudgmental attitude.

Act like you’ve been here before, even if you haven’t. Make the patient believe this is an everyday occurrence for you and nothing to be ashamed of.

We go into more depth in a recent article about caring for LGBTQ individuals. But first and foremost, remember that:

1. A transgender patient is a person with a health concern.

2. Our job as nursing professionals is to provide equitable care

Nurses who are firmly grounded in these two tenets are on their way to providing quality care for these patients.

Make the best career decision ever.

To a transgender patient, how they identify is more important than their sexual equipment.

Use the pronoun the person prefers. He or she knows which one s/he prefers before using one.

If all else fails, “you” and “your” work great.

On that subject, ask the patient the name s/he prefers. A patient’s legal name may be Michael, but she prefers Debra.

But verbal language is not the only kind of communication.

Does the healthcare space offer symbols of inclusivity? A rainbow flag or poster about World AIDS Day can go a long way.

Ensure that forms cater to transgender individuals. There should be a section for preferred name, sexual orientation, gender identity, and “partner” information.

Rework assessment questions with hetero-preferential word choices. Even LGBTQ members on your team can set the stage for open interaction.

Need more advice? Read 10 Tips For Caring for LGBTQ Patients.

Setting the Pace for Self-Disclosure: Let the Transgender Patient Lead

Transgender patients may be slow to reveal much about themselves. Negative experiences can do that to a person.

Cultivate patience. Over time, the individual will feel assured that the environment is safe for self-disclosure.

Gender Transitions Happen Slowly

Transgender identity is a process. Individuals may fall at different points along the transition spectrum.

A transgender man is a person assigned female at birth but who identifies as male. A transgender male patient may have taken hormones and/or had breast reduction surgery, but may or may not have female genitalia.

A transgender woman is a person assigned male at birth but who identifies as female. A transgender woman may have a female voice and breasts, and also the male genitalia that genetics gave her.

Don’t assume she will use a bedpan. Instead, ask “ Is there anything else you need for your physical comfort? ”

Put Yourself In His High Heels

Transgender individuals often avoid or postpone preventive screenings.

Many can’t endure the thought of a repeat of a past experience. And, some fear the looks when others assess that they are walking into the “wrong” type of clinic.

A transgender male may be stressed by having to sit in a mammography waiting room with women.

He has a right to be there, though. His residual female breast tissue warrants a mammogram.

Likewise, a transgender woman still has a prostate needing an annual check.

Nonetheless, quality care includes good information to help patients protect their health and life through early screening and detection.

Get familiar with recommended screenings for transgender men and women. Be ready with the correct information and protocol.

Don’t act surprised or flustered. This heightens tension and can shut down any chances you had at having an open discussion.

Employers are looking for qualified Registered Nurses like you.

See who’s hiring now. Get Started Today!

Tap Your Community For Help

Consult with your organization’s social work or patient navigation department. Familiarize yourself with local and national community resources.

But don’t just rely on organizations. Ask your nurse friends from other units or facilities about their most awkward situations and how they handled them.

Their triumphs and mistakes can make your next encounter with a transgender patient a smooth one.

Beyond that, stay abreast of health concerns and risks. Know the appropriate terminology, and any additions to the LGBTQ spectrum. People are not defined by acronyms.

Lastly, don’t be afraid to ask the tough, awkward questions in a non-judgmental fashion.

- Can you give information about your sexual preferences?

- With whom are a few of your supportive relationships?

- Are you engaged in high-risk behaviors?

- Anything else I should know that could impact your health?

Sensitivity is key when administering care to your transgender patient. But, don’t shy away from relevant information that can protect and prolong his or her health.

Your patient will thank you in the long run, and so will his or her loved ones.

Next Up: Guaranteed Moments of Happiness In Hospital Corridors

1. Judge rules doctors can refuse trans patients and women who have had abortions. Marie Solis, Mic.com. mic.com/articles/164234/judge-rules-doctors-can-refuse-trans-patients-and-women-who-have-had-abortions (accessed March 3, 2017).

2. Estimate of US Transgender Population Doubles to 1.4 Million Adults . Jan Hoffman, New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2016/07/01/health/transgender-population.html?_r=0 (accessed March 3, 2017).

3. About LGBT Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/about.htm (accessed February 11, 2017)

4. Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. Guidelines for Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients. www.outforhealth.org/files/all/glma_guidelines_providers.pdf (accessed February 11, 2017)

5. Gay and lesbian Medical Association. Ten Things Transgender Persons Should Discuss with Their Healthcare Care Provider. www.glma.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.viewPage&pageID=692 (accessed February 11, 2017).

6. Green J, et al. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Disparities, and President Obama’s Commitment for Change in Health Care . Race, Gender & Class: Vol. 17 No. 3-4, 2010 (272-287).

7. More Than Pink: LGBTQ Breast Health – LGBTQ Health Care Experiences in Western Washington . Susan G. Komen, Puget Sound: http://komenpugetsound.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/More-Than-Pink-LGBTQ-Breast-Health_web.pdf (accessed February 11, 2017)

8. The Joint Commission. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient-and Family-Centered Care for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community – A Field Guide. 2011. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/LGBTFieldGuide.pdf (accessed February 11, 2017)

9. Women’sHealth.gov: www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/lesbian-bisexual-health.html (accessed February 11, 2017).

Plus, get exclusive access to discounts for nurses, stay informed on the latest nurse news, and learn how to take the next steps in your career.

By clicking “Join Now”, you agree to receive email newsletters and special offers from Nurse.org. We will not sell or distribute your email address to any third party, and you may unsubscribe at any time by using the unsubscribe link, found at the bottom of every email.

Supporting the Transgender Community: Gender Affirming Care Resources

Home / Nursing Articles / Supporting the Transgender Community: Gender Affirming Care Resources

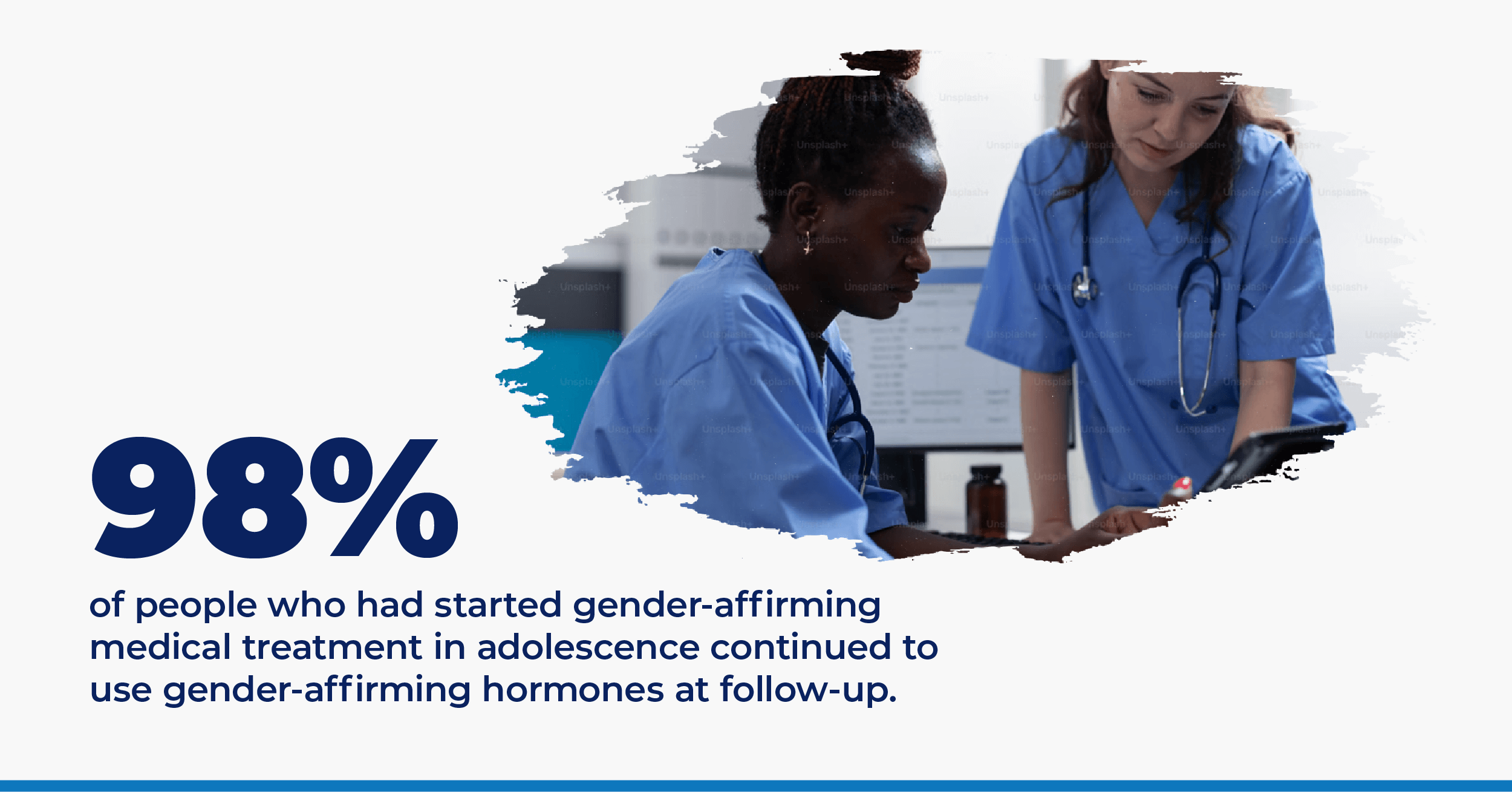

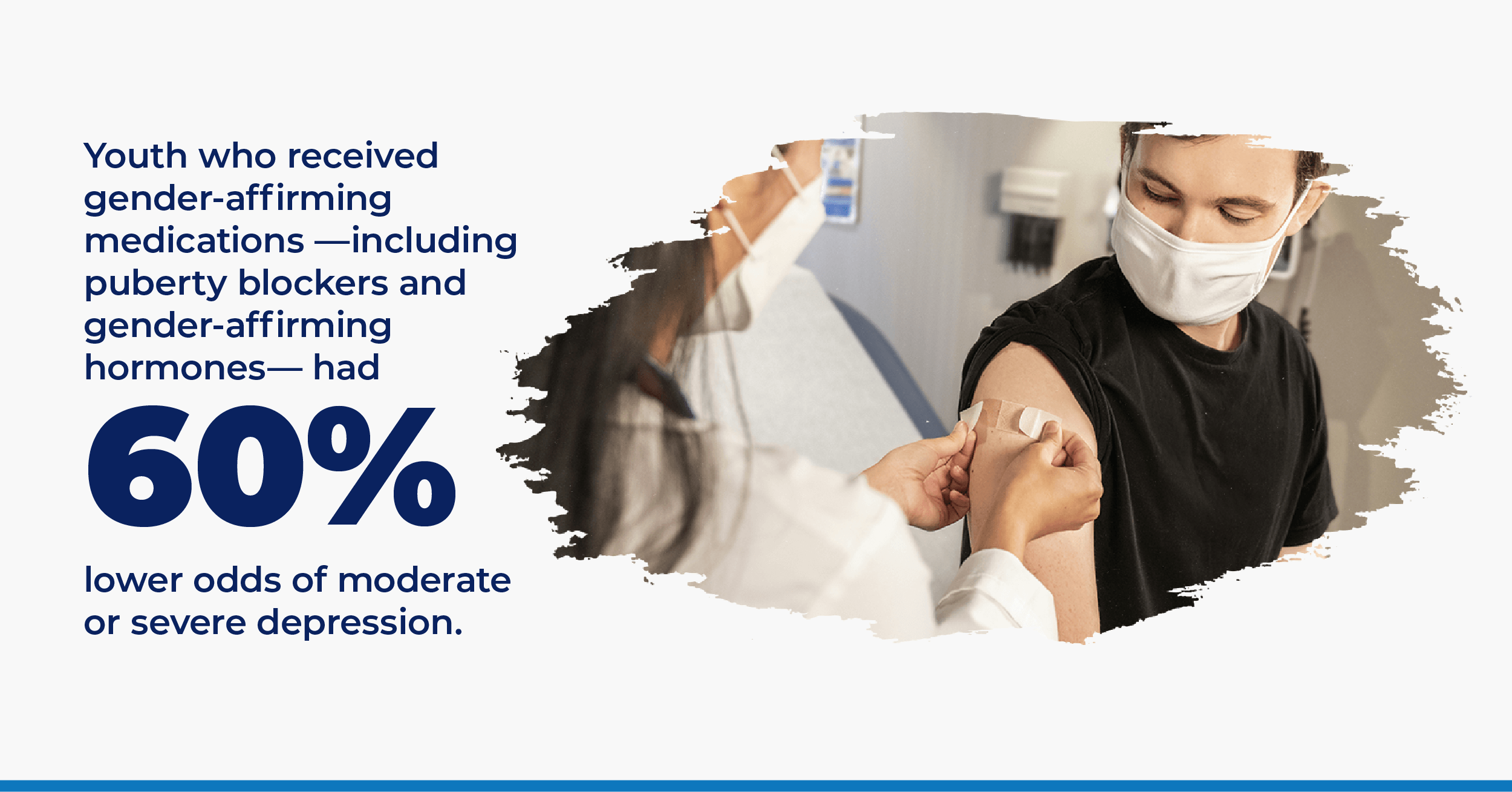

For transgender and nonbinary individuals, early and continued access to gender-affirming care is critical to improving confidence and allowing people to use their focus for transitioning socially while navigating the complex and sometimes unwelcoming healthcare system. Gender-affirming care can include social affirmation, puberty blockers, hormone therapy, and gender-affirming surgeries. This care can be life-saving , as it improves the mental health and overall well-being of gender-diverse children, adolescents, and adults.

Gender non-conforming students can find access to gender-affirming treatment at many colleges in the United States and abroad, and healthcare providers working in these schools receive training on gender-affirming, patient-centered care. For younger students, school nurses play an important role in supporting gender non-conforming students by directing them to resources and assuring them that their identities and feelings are valid and meaningful. For adults, healthcare provider education is crucial since many gender diverse individuals report discrimination within the healthcare system.

These resources are made available to anyone in the healthcare field, preparing as a student to work with diverse populations, including gender non-conforming youth, allies, educators, the transgender community, and more. You'll find research articles, helpful websites, links to organizations, and even legal and healthcare resources here. We hope you find these resources informative and helpful, no matter what part of your journey.

Gender-Affirming Care is Trauma-Informed Care

The National Child Trauma Stress Network released this article, which looks at how gender-affirming care in children can reduce future stress.

Supporting Safe and Healthy Schools for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Students

In this article, you’ll see the results of a major survey that talked with school professionals about the changes needed to support LGBTQ+ students .

Mental Health Outcomes in Transgender and Nonbinary Youths Receiving Gender-Affirming Care

Published in February 2022, this article looks at whether mental health support and gender-affirming care can reduce the suicide numbers among LGBTQ+ youths.

Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth: Current Concepts

Read this recent article to learn more about gender-affirming care, the field’s current concepts, and what needs to change.

Mental Health and Timing of Gender-Affirming Care

Available for free, this article focuses on whether the age at which an individual receives gender-affirming care relates to their mental health.

Factors Associated with Experiences of Gender-Affirming Health Care: A Systematic Review

This systematic review looks at youths’ experiences with gender-affirming care and what factors impacted them in getting it.

Barriers to Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Individuals

Discover the barriers that keep transgender and non-binary people from getting the care and treatment they need in this article from 2017.

Experiences of Transgender and Non-Binary Youth Accessing Gender-Affirming Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography

The authors reviewed current and past studies to examine the experiences associated with gender-affirming care among youth.

Understanding Community Member and Health Care Professional Perspectives on Gender-Affirming Care—A Qualitative Study

This article examines the barriers to seeking gender-affirming care and addresses some possible solutions.

"It's Kind of Hard to go to the Doctor's Office if You're Hated There." A Call for Gender-Affirming Care from Transgender and Gender Diverse Adolescents in the United States

This article examines barriers to health care and delves into how some patients feel their doctors hate them or dislike them.

Association Between Gender-Affirming Surgeries and Mental Health Outcomes

Released in 2021, this journal article focuses on the link between mental health and when patients received gender-affirming care.

Gender-Affirming Care for Transgender Patients

Learn more about the disparities between transgender patients and others in this study that came out in June 2022 and looked at modern treatments.

Psychosocial Characteristics of Transgender Youth Seeking Gender-Affirming Medical Treatment: Baseline Findings From the Trans Youth Care Study

This study looked at two groups of trans youths to see the impact of gender-affirming medical treatment on their development over time.

Helpful Websites

The Gender Unicorn

The Gender Unicorn takes a fun approach to gender and shows how it can fluctuate along with what each term means.

Learning Resources – Transgender Health

This is a great website to visit if you have questions about getting health care as a transgender person or you want to know about the available treatments.

National Center for Transgender Equality

This website offers a range of helpful resources for transgender youths and links to resources in different states.

The Trans Hub is a fantastic place for transgender students, and it offers social, legal, and medical help to you and your allies.

TransActual

Please read through the research studies done by this organization on its website, which also features stories and experiences of transgender people.

Trans Lifeline

This organization was launched to help people whom others look down on and provide them a lifeline in the modern world through free resources.

You can read through the stories on this website to learn from people who are trans or watch some of the videos that cover exciting and challenging topics.

Transgender Map

If you feel alone in the world, this website acts as your map with its resources for transgender youths who are in the closet or recently out.

TransFamilies

Designed for the loved ones of transgender youths, this site features a range of resources, such as frequently asked questions and local events.

National Black Trans Advocacy Coalition

Members of the black community who are also transgender will find lots of help on this site, such as resources for getting medical help and finding a job.

Trans Student Educational Resources

Also known as TSER, this organization has a website with press releases and offers services such as scholarships, policies, and workshops.

TransLatin Coalition

Designed for transgender and Latin people for people in the same community, this organization offers a training course for professionals and services in the LA area.

Transgender Aging Network

The Transgender Aging Network offers support for the loved ones of elderly people, including training programs and products to make their lives easier.

Movement Advancement Project

Known as MPA, this organization offers information about new and upcoming transgender equality projects and programs nationwide.

Global Action for Trans Equality

GATE is an organization that runs campaigns designed to improve equality for transgender youth as well as those who are intersex or non-binary.

TransAthlete

Turn to this website if you have questions about transgender athletes or if you want to learn about the policies used by schools and states.

Puberty and Transgender Youth

Amaze released this short video to discuss some of the changes that happen to their bodies during puberty among transgender youth.

El Camino College – TimelyCare Provides Gender-Affirming Care for Student

In this El Camino College video, you’ll see how TimelyCare supports students who need gender-affirming care when they go to college.

Best Practices for Supporting Transgender College Students | Building Bridges

Building Bridges spends nearly an hour reviewing what colleges can do to support transgender students and help them feel comfortable and confident.

Trans Health: What is Gender-Affirming Care?

York University uses this video to review the fundamentals of gender-affirming care, such as what it means and how to get it.

HRC Explains Gender-Affirming Care

In this video, the Human Rights Campaign details gender-affirming care to help viewers find answers to their questions.

Population Healthy S5 Ep02: Gender Affirming Care

From Michigan Public Health, this video offers a good explanation of gender-affirming care and the benefits it has for transgender youth today.

How Gender-Affirming Care Improves Mental Health

In just over a minute, an expert speaks about the positive impacts that gender-affirming care has on both transgender youth and their loved ones.

Education and Training for Gender-Affirming Health Care

Created by a medical organization, this video examines why education and training are essential for healthcare professionals and their patients.

What to Expect on Hormones

Planned Parenthood offers videos in both English and Spanish to ensure transgender youth understand what hormones will do to their bodies and the overall benefits.

Basics of Gender-Affirming Care for Health Professionals

Designed for medical professionals, this video helps medical professionals understand how to treat transgender patients and provide gender-affirming care.

Podcast: An Introduction to Transgender Health

This podcast serves as an introduction to transgender health issues and is suitable for members of the community as well as healthcare providers.

Exclusively Inclusive

Tune in every week to listen as professional and everyday people discuss what it means to be inclusive in today’s world.

Gender Affirming Care

The School of Public Health at the University of Michigan designed this podcast to inform listeners about the importance of gender-affirming care.

Podcast: Medical Care and Emotional Support for Transgender Youth

This episode from Kids Health Cast focuses on why transgender kids need both emotional support and medical care from their doctors and others.

The Gender GP Podcast

Two women use The Gender GP Podcast to discuss identity and other issues in the trans community with others.

Listen Now: Transgender Health Care Today

Listen Now is one of the best podcasts if you are interested in transgender health care and want to know more about its challenges.

The Trans Narrative

The Trans Narrative offers a safe space for transgender youths and others to talk and hear about some of the most significant issues in the community.

A Health Podyssey

Though not entirely about transgender issues, this podcast uses each episode to discuss the common problems affecting the healthcare industry.

Gender Stories

The author of a book about gender identity hosts this podcast, which gives listeners a safe space to share their gender experiences and stories.

PFLAG: Our Trans Loved Ones

Download a copy of this guide from PFLAG organizers to find some ways you can support a trans loved one after they come out.

PFLAG: Find Resources

PFLAG offers many resources for those in need that you’ll find here, including how to become or be a better ally and what you can do to help others.

Straight for Equality: Trans & Non-Binary

Straight for Equality, which was launched in 2007, now offers helpful online guides and resources on creating an inclusive workplace and other topics.

Be an Ally – Support Trans Equality

Join the Human Rights Campaign to watch online videos and discover tips on being a better ally to those in the trans community.

Guide to Being an Ally to Transgender and Nonbinary Young People

This resource is free and introduces how to treat and act around young people who identify as non-binary or transgender.

Tips for Allies of Transgender People

This guide offers many useful tips, such as when to use pronouns, what coming out means, and how to discuss gender topics.

Supporting the Transgender People in Your Life: A Guide to Being a Good Ally

This guide explains what it means to be an excellent transgender ally, including when to step up and how to change the world.

This PDF explains what transgender and non-binary mean, how to avoid common mistakes, and what to do when you make a mistake.

Straight for Equality: Becoming a Trans Ally

PFLAG offers this toolkit that includes information on what pronouns mean and when to use them, worksheets, and tips on becoming an ally.

Legal Resources

Clinicians in Court: A Guide to Subpoenas, Depositions, Testifying, and Everything Else You Need to Know

Students and professionals worldwide use this guide to learn the basics of case law and how they should act in the courtroom.

Supporting the Rights of Transgender Students and Their Families

In this piece, Heather Godsey addresses some issues facing transgender students today and discusses what they and their families can do.

Freedom for All Americans

Please read this letter from the organization of the same name to see some of the changes it helped fund and its plans for the future.

Transgender Rights

The ACLU looks at the rights of transgender people here and includes links to articles about big policy changes and legal challenges.

Your Rights

Work with GLAD to learn more about your legal rights and to get help finding a lawyer willing to fight for you and defend your rights.

Healthcare is Caring

Please read through the open letter to learn about the positive impacts of gender-affirming care and then sign it at the bottom to show your support.

Transgender Law Center

This organization offers a range of resources to help transgender individuals learn about their rights and find legal help.

Trans Agenda

The Trans Agenda believes that everyone deserves the right to legal help, which is why it funds cases and provides resources to those in need.

Transgender Resources

This website, available from the American Bar Association (ABA), offers information about the Legal Resistance Network and highlights resistance groups.

SRLP Legal Intake

See how you can get help from the SRLP on its official website and learn how to get involved and help others in need.

Transgender Legal Services Network

If you or someone you know is transgender and needs legal help, turn to this organization to find lawyers working across the country.

Transgender Legal Defense & Education Fund

This fund offers financial support for transgender people who need help paying for school or mounting a legal defense.

Lambda Legal

Lambda Legal defends non-binary and transgender people worldwide through financial support and free legal resources.

Health Education for Healthcare Providers and Educators

Transgender & Gender Diverse Inclusive Resources for Your Practice

If you work in the healthcare field, this page is perfect because it offers resources, such as how to examine and help transgender patients.

Pubertal Suppression for Youth with Gender Dysphoria/Gender Incongruence

This article is available as a PDF and looks at how hormone blockers and other treatments that prevent puberty can help transgender patients.

Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8

Version 8 is an updated version of this guide that helps doctors and other medical providers understand the standards of transgender care.

Transgender and Gender Diverse Services

Outside, In is a weekday clinic that helps transgender and non-binary patients receive health care they can’t get anywhere else.

Provider Directory

WPATH offers a free directory to search for gender-affirming care doctors based on your location or their name.

Creating Safer Spaces for LGBTQ Youth

Though this PDF toolkit is just a few pages, it covers many helpful topics for community organizations like creating a safe space.

Transgender Health in Medical Education

Created by the Bull World Health Organization, this piece goes over the changes it hopes to see by 2030 and what those changes will mean for the community.

National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center

Discover free resources, educational programs, and much more on this website of an organization dedicated to helping LGBTQIA+ people with their health care needs.

The Power to Help or Harm: Student Perceptions of Transgender Health Education Using a Qualitative Approach

The authors of this piece look at how students think and feel about gender-affirming care based on whether they can access it.

Transgender Health Care: Improving Medical Students’ and Residents’ Training and Awareness

This article, released in 2018, examines the best practices and methods for raising residents’ and students’ awareness of transgender topics.

Patient-Centered Care for Transgender People: Recommended Practices for Health Care Settings

The CDC addresses how to put transgender patients first and how to understand their unique needs and the challenges in helping them.

Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People

Recently revised, this guide from UCSF looks at what doctors and other medical professionals should do when caring for non-binary and transgender patients.

Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People

Get a free version of this book in a PDF form that helps you learn about and understand the standards of care for today’s patients.

Compulsory Transgender Health Education: The Time Has Come

Family Medicine published this article by a medical doctor to explain that complete care for transgender is necessary in the modern world.

Fair Use Statement: Please share our content for editorial or discussion purposes. Please link back to this page and give proper credit to RegisteredNursing.org.

Latest Articles & Guides

One of the keys to success as a registered nurse is embracing lifelong learning. Our articles and guides address hot topics and current events in nursing, from education to career mobility and beyond. No matter where you are on your nursing journey, there’s an article to help you build your knowledge base.

Browse our latest articles, curated specifically for modern nurses.

See All Articles

DAVID A. KLEIN, MD, MPH, SCOTT L. PARADISE, MD, AND EMILY T. GOODWIN, MD

Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(11):645-653

Related editorial: The Responsibility of Family Physicians to Our Transgender Patients

See related article from Annals of Family Medicine : Primary Care Clinicians' Willingness to Care for Transgender Patients

Patient information: A handout on this topic is available at https://familydoctor.org/lgbtq-mental-health-issues/

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

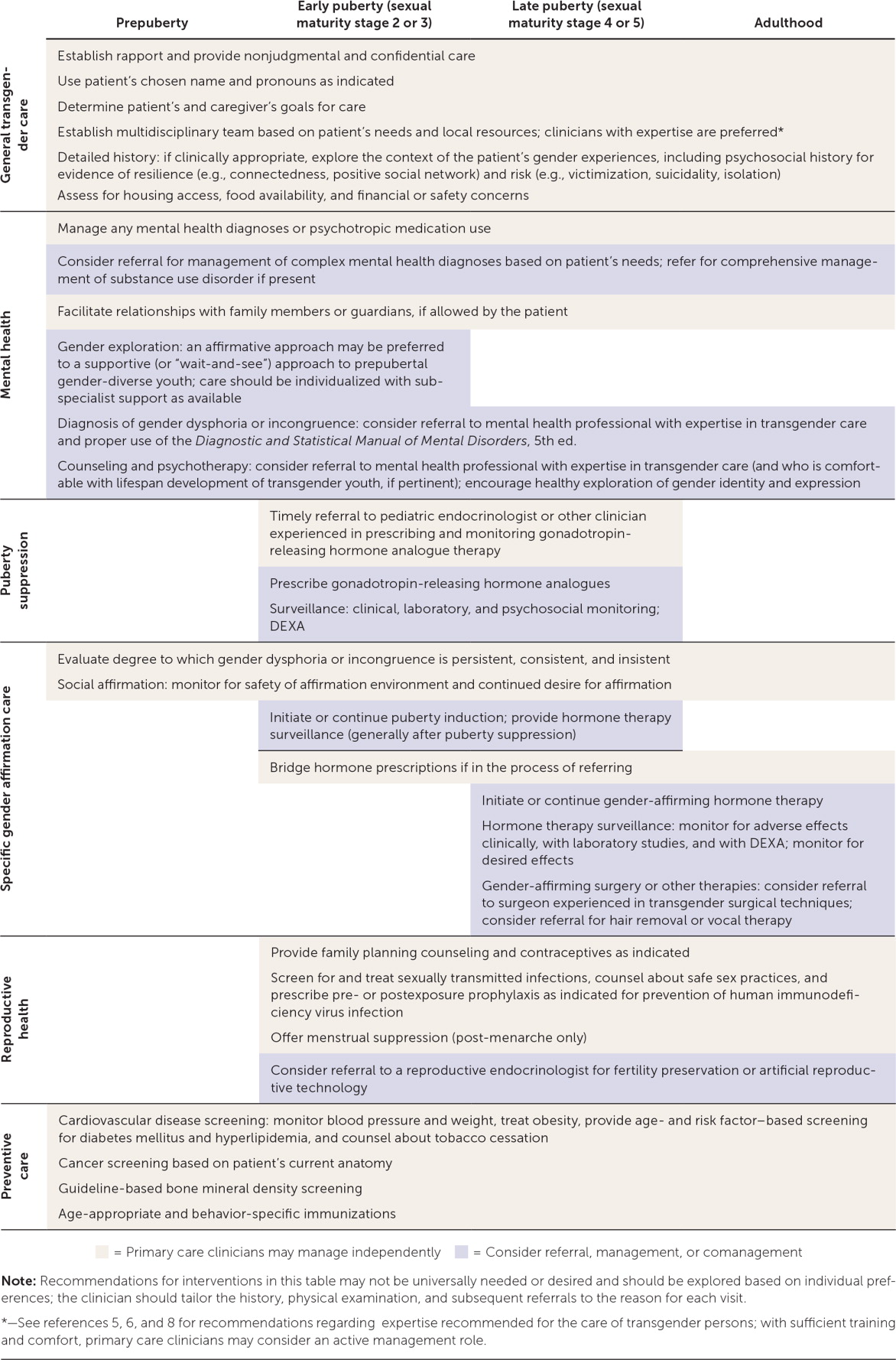

Persons whose experienced or expressed gender differs from their sex assigned at birth may identify as transgender. Transgender and gender-diverse persons may have gender dysphoria (i.e., distress related to this incongruence) and often face substantial health care disparities and barriers to care. Gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation, sex development, and external gender expression. Each construct is culturally variable and exists along continuums rather than as dichotomous entities. Training staff in culturally sensitive terminology and transgender topics (e.g., use of chosen name and pronouns), creating welcoming and affirming clinical environments, and assessing personal biases may facilitate improved patient interactions. Depending on their comfort level and the availability of local subspecialty support, primary care clinicians may evaluate gender dysphoria and manage applicable hormone therapy, or monitor well-being and provide primary care and referrals. The history and physical examination should be sensitive and tailored to the reason for each visit. Clinicians should identify and treat mental health conditions but avoid the assumption that such conditions are related to gender identity. Preventive services should be based on the patient's current anatomy, medication use, and behaviors. Gender-affirming hormone therapy, which involves the use of an estrogen and antiandrogen, or of testosterone, is generally safe but partially irreversible. Specialized referral-based surgical services may improve outcomes in select patients. Adolescents experiencing puberty should be evaluated for reversible puberty suppression, which may make future affirmation easier and safer. Aspects of affirming care should not be delayed until gender stability is ensured. Multidisciplinary care may be optimal but is not universally available.

A = consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence; B = inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence; C = consensus, disease-oriented evidence, usual practice, expert opinion, or case series. For information about the SORT evidence rating system, go to https://www.aafp.org/afpsort .

eTable A provides definitions of terms used in this article. Transgender describes persons whose experienced or expressed gender differs from their sex assigned at birth. 5 , 6 Gender dysphoria describes distress or problems functioning that may be experienced by transgender and gender-diverse persons; this term should be used to describe distressing symptoms rather than to pathologize. 7 , 8 Gender incongruence, a diagnosis in the International Classification of Diseases , 11th revision (ICD-11), 9 describes the discrepancy between a person's experienced gender and assigned sex but does not imply dysphoria or a preference for treatment. 10 The terms transgender and gender incongruence generally are not used to describe sexual orientation, sex development, or external gender expression, which are related but distinct phenomena. 5 , 7 , 8 , 11 It may be helpful to consider the above constructs as culturally variable, nonbinary, and existing along continuums rather than as dichotomous entities. 5 , 8 , 12 , 13 For clarity, the term transgender will be used as an umbrella term in this article to indicate gender incongruence, dysphoria, or diversity.

Optimal Clinical Environment

It is important for clinicians to establish a safe and welcoming environment for transgender patients, with an emphasis on establishing and maintaining rapport ( Table 1 ) . 5 , 6 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 14 – 21 Clinicians can tell patients, “Although I have limited experience caring for gender-diverse persons, it is important to me that you feel safe in my practice, and I will work hard to give you the best care possible.” 22 Waiting areas may be more welcoming if transgender-friendly materials and displayed graphics show diversity. 5 , 12 , 14 , 15 Intake forms can be updated to include gender-neutral language and to use the two-step method (two questions to identify chosen gender identity and sex assigned at birth) to help identify transgender patients. 5 , 16 , 23 Training clinicians and staff in culturally sensitive terminology and transgender topics, as well as cultural humility and assessment of personal internal biases, may facilitate improved patient interactions. 5 , 21 , 24 Clinicians may also consider advocating for transgender patients in their community. 12 , 14 , 15 , 21

MEDICAL HISTORY

When assessing transgender patients for gender-affirming care, the clinician should evaluate the magnitude, duration, and stability of any gender dysphoria or incongruence. 8 , 12 Treatment should be optimized for conditions that may confound the clinical picture (e.g., psychosis) or make gender-affirming care more difficult (e.g., uncontrolled depression, significant substance use). 6 , 11 , 17 The support and safety of the patient's social environment also warrants evaluation as it pertains to gender affirmation. 6 , 8 , 11 This is ideally accomplished with multidisciplinary care and may require several visits to fully evaluate. 5 , 6 , 8 , 17 Depending on their comfort level and the availability of local subspecialty support, primary care clinicians may elect to take an active role in the patient's gender-related care by evaluating gender dysphoria and managing hormone therapy, or an adjunctive role by monitoring well-being and providing primary care and referrals ( Figure 1 ) . 5 , 6 , 8 , 11 – 15 , 17 , 19 , 21 , 22

Clinicians should not consider themselves gatekeepers of hormone therapy; rather, they should assist patients in making reasonable and educated decisions about their health care using an informed consent model with parental consent as indicated. 5 , 17 Based on expert opinion, the Endocrine Society recommends that clinicians who diagnose gender dysphoria or incongruence and who manage gender-affirming hormone therapy receive training in the proper use of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed., and the ICD; have the ability to determine capacity for consent and to resolve psychosocial barriers to gender affirmation; be comfortable and knowledgeable in prescribing and monitoring hormone therapies; attend relevant professional meetings; and, if applicable, be familiar with lifespan development of transgender youth. 6

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Transgender patients may experience discomfort during the physical examination because of ongoing dysphoria or negative past experiences. 4 , 5 , 8 Examinations should be based on the patient's current anatomy and specific needs for the visit, and should be explained, chaperoned, and stopped as indicated by the patient's comfort level. 5 Differences of sex development are typically diagnosed much earlier than gender dysphoria or gender incongruence. However, in the absence of gender-affirming hormone therapy, an initial examination may be warranted to assess for sex characteristics that are incongruent with sex assigned at birth. Such findings may warrant referral to an endocrinologist or other subspecialist. 6 , 25

Mental Health

Transgender patients typically have high rates of mental health diagnoses. 11 , 18 However, it is important not to assume that a patient's mental health concerns are secondary to being transgender. 5 , 12 , 15 Primary care clinicians should consider routine screening for depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, substance use, intimate partner violence, self-injury, bullying, truancy, homelessness, high-risk sexual behaviors, and suicidality. 5 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 19 , 26 – 29 Clinicians should be equipped to handle the basic mental health needs of transgender persons (e.g., first-line treatments for depression or anxiety) and refer patients to subspecialists when warranted. 5 , 8 , 15

Because of the higher prevalence of traumatic life experiences in transgender persons, care should be trauma-informed (i.e., focused on safety, empowerment, and trustworthiness) and guided by the patient's life experiences as they relate to their care and resilience. 5 , 15 , 30 Efforts to convert a person's gender identity to align with their sex assigned at birth—so-called gender conversion therapy—are unethical and incompatible with current guidelines and evidence, including policy from the American Academy of Family Physicians. 6 , 8 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 31

Health Maintenance

Preventive services are similar for transgender and cisgender (i.e., not transgender) persons. Nuanced recommendations are based on the patient's current anatomy, medication use, and behaviors. 5 , 6 , 32 Screening recommendations for hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, hypertension, and obesity are available from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). 33 Clinicians should be vigilant for signs and symptoms of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and metabolic disease because hormone therapy may increase the risk of these conditions. 5 , 6 , 34 Screening for osteoporosis is based on hormone use. 6 , 35

Cancer screening recommendations are determined by the patient's current anatomy. Transgender females with breast tissue and transgender males who have not undergone complete mastectomy should receive screening mammography based on guidelines for cisgender persons. 6 , 36 Screening for cervical and prostate cancers should be based on current guidelines and the presence of relevant anatomy. 5 , 6

Recommendations for immunizations (e.g., human papillomavirus) and screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (including human immunodeficiency virus) are provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and USPSTF based on sexual practices. 32 , 33 , 37 , 38 Pre- and postexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus infection should be considered for patients who meet treatment criteria. 32 , 38

Hormone Therapy

Feminizing and masculinizing hormone therapies are partially irreversible treatments to facilitate development of secondary sex characteristics of the experienced gender. 6 Not all gender-diverse persons require or seek hormone treatment; however, those who receive treatment generally report improved quality of life, self-esteem, and anxiety. 5 , 6 , 39 – 44 Patients must consent to therapy after being informed of the potentially irreversible changes in physical appearance, fertility potential, and social circumstances, as well as other potential benefits and risks.

Feminizing hormone therapy includes estrogen and antiandrogens to decrease the serum testosterone level below 50 ng per dL (1.7 nmol per L) while maintaining the serum estradiol level below 200 pg per mL (734 pmol per L). 6 Therapy may reduce muscle mass, libido, and terminal hair growth, and increase breast development and fat redistribution; voice change is not expected. 5 , 6 The risk of VTE can be mitigated by avoiding formulations containing ethinyl estradiol, supraphysiologic doses, and tobacco use. 34 , 45 – 47 Additional risks include breast cancer, prolactinoma, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, cholelithiasis, and hypertriglyceridemia; however, these risks are rare (yet clinically significant), indolent, or incompletely studied. 5 , 6 , 36 , 48 Spironolactone use requires monitoring for hypotension, hyperkalemia, and changes in renal function. 5 , 6

Masculinizing hormone therapy includes testosterone to increase serum levels to 320 to 1,000 ng per dL (11.1 to 34.7 nmol per L). 6 Anticipated changes include acne, scalp hair loss, voice deepening, vaginal atrophy, clitoromegaly, weight gain, facial and body hair growth, and increased muscle mass. Patients receiving masculinizing hormone therapy are at risk of erythrocytosis, as determined by male-range reference values (e.g., hematocrit greater than 50%). 5 , 6 , 45 , 49 Data on patient-oriented outcomes (e.g., death, thromboembolic disease, stroke, osteoporosis, liver toxicity, myocardial infarction) are sparse. Despite possible metabolic effects, few serious events have been identified in meta-analyses. 6 , 34 , 35 , 45 , 46 , 49

Active hormone-sensitive malignancy is an absolute contraindication to gender-affirming hormone treatment. 5 Patients who are older, use tobacco, or have severe chronic disease, current or previous VTE, or a history of hormone-sensitive malignancy may benefit from individualized dosing regimens and subspecialty consultation. 5 The benefits and risks of treatment should be weighed against the risks of inaction, such as suicidality. 5 The use of low-dose transdermal estradiol-17 β (Climara) may reduce the risk of VTE. 5

Some patients without coexisting conditions may prefer a lower dose or individualized regimen. 5 All patients should be offered referral to discuss fertility preservation or artificial reproductive technology. 5 , 20 Table 2 5 , 6 , 17 , 22 , 50 and eTable B present surveillance guidelines and dosing recommendations for patients receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Surgery and Other Treatments

Gender-affirming surgical treatments may not be required to minimize gender dysphoria, and care should be individualized. 6 Mastectomy (i.e., chest reconstruction surgery) may be performed for transmasculine persons before 18 years of age, depending on consent, duration of applicable hormone treatment, and health status. 6 Breast augmentation for transfeminine persons may be timed to maximal breast development from hormone therapy. 5 , 6 Mastectomy or breast augmentation generally costs less than $10,000, and insurance coverage varies. 51 Patients may also request referral for facial and laryngeal surgery, voice therapy, or hair removal. 5 , 6 , 8

The Endocrine Society recommends that persons who seek fertility-limiting surgeries reach the legal age of majority, optimize treatment for coexisting conditions, and undergo social affirmation and hormone treatment (if applicable) continuously for 12 months. 6 Adherence to hormone therapy after gonadectomy is paramount for maintaining bone mineral density. 6 Despite associated costs, varying insurance coverage, potential complications, and the potential for prolonged recovery, 6 , 8 , 51 gender-affirming surgeries generally have high satisfaction rates. 6 , 42

Transgender Youth

Most, but not all, transgender adults report stability of their gender identity since childhood. 17 , 52 However, some gender-diverse prepubertal children subsequently identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual adolescents, or have other identities instead of transgender, 8 , 11 , 17 , 53 – 55 as opposed to those in early adolescence, when gender identity may become clearer. 5 , 8 , 11 , 17 , 43 , 44 , 53 , 55 There is no universally accepted treatment protocol for prepubertal gender-diverse children. 6 , 12 , 17 Clinicians may preferentially focus on assisting the child and family members in an affirmative care strategy that individualizes healthy exploration of gender identity (as opposed to a supportive, “wait-and-see” approach); this may warrant referral to a mental health clinician comfortable with the lifespan development of transgender youth. 6 , 12 , 13 , 21

Transgender adolescents should have access to psychological therapy for support and a safe means to explore their gender identity, adjust to socioemotional aspects of gender incongruence, and discuss realistic expectations for potential therapy. 6 , 8 , 12 , 17 The clinician should advocate for supportive family and social environments, which have been shown to confer resilience. 14 , 18 , 21 , 40 , 56 , 57 Unsupportive environments in which patients are bullied or victimized can have adverse effects on psychosocial functioning and well-being. 21 , 58 , 59

Transgender adolescents may experience distress at the onset of secondary sex characteristics. Clinicians should consider initiation of or timely referral for a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) to suppress puberty when the patient has reached stage 2 or 3 of sexual maturity. 5 , 6 , 8 , 17 , 21 , 40 , 44 This treatment is fully reversible, may make future affirmation easier and safer, and allows time to ensure stability of gender identity. 6 , 17 No hormonal intervention is warranted before the onset of puberty. 6 , 8 , 17

Consent for treatment with GnRH analogues should include information about benefits and risks 5 , 6 , 8 , 15 , 50 ( eTable B ) . Before therapy is initiated, patients should be offered referral to discuss fertility preservation, which may require progression through endogenous puberty. 5 , 6

Some persons prefer to align their appearance (e.g., clothing, hairstyle) or behaviors with their gender identity. The risks and benefits of social affirmation should be weighed. 5 , 6 , 8 , 13 , 17 , 56 Transmasculine postmenarcheal youth may undergo menstrual suppression, which typically provides an additional contraceptive benefit (testosterone alone is insufficient). 5 Breast binding may be used to conceal breast tissue but may cause pain, skin irritation, or skin infections. 5

Multiple studies report improved psychosocial outcomes after puberty suppression and subsequent gender-affirming hormone therapy. 39 – 42 , 44 , 60 Delayed treatment may potentiate psychiatric stress and gender-related abuse; therefore, withholding gender-affirming treatment in a wait-and-see approach is not without risk. 8 Additional resources for transgender persons, family members, and clinicians are presented in eTable C .

Data Sources: PubMed searches were completed using the MeSH function with the key phrases transgender, gender dysphoria, and gender incongruence. The reference lists of six cited manuscripts were searched for additional studies of interest, including three relevant reviews and guidelines by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health; the Center of Excellence for Transgender Health at the University of California, San Francisco; and the Endocrine Society. Other queries included Essential Evidence Plus and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Search dates: November 1, 2017, to September 18, 2018.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force; the Department of Defense; or the U.S. government.

Conron KJ, Scott G, Stowell GS, Landers SJ. Transgender health in Massachusetts: results from a household probability sample of adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):118-122.

Herman JL, Flores AR, Brown TN, Wilson BD, Conron KJ. Age of individuals who identify as transgender in the United States. January 2017. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/TransAgeReport.pdf . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM. Transgender population size in the United States: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):e1-e8.

Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. http://www.thetaskforce.org/static_html/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. 2nd ed. June 17, 2016. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/protocols . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Endocrinol Metab . 2018;103(2):699]. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgenderism. 2012;13(4):165-232.

World Health Organization. ICD-11: classifying disease to map the way we live and die. Coding disease and death. June 18, 2018. http://www.who.int/health-topics/international-classification-of-diseases . Accessed August 25, 2018.

Reed GM, Drescher J, Krueger RB, et al. Disorders related to sexuality and gender identity in the ICD-11: revising the ICD-10 classification based on current scientific evidence, best clinical practices, and human rights considerations [published correction appears in World Psychiatry . 2017;16(2):220]. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):205-221.

Adelson SL American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice parameter on gay, lesbian, or bisexual sexual orientation, gender nonconformity, and gender discordance in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(9):957-974.

American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol. 2015;70(9):832-864.

de Vries AL, Klink D, Cohen-Kettenis PT. What the primary care pediatrician needs to know about gender incongruence and gender dysphoria in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):1121-1135.

Levine DA Committee on Adolescence. Office-based care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e297-e313.

Klein DA, Malcolm NM, Berry-Bibee EN, et al. Quality primary care and family planning services for LGBT clients: a comprehensive review of clinical guidelines. LGBT Health. 2018;5(3):153-170.

Deutsch MB, Buchholz D. Electronic health records and transgender patients—practical recommendations for the collection of gender identity data. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):843-847.

Olson J, Forbes C, Belzer M. Management of the transgender adolescent. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):171-176.

Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):943-951.

Marcell AV, Burstein GR Committee on Adolescence. Sexual and reproductive health care services in the pediatric setting. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5):e20172858.

Klein DA, Berry-Bibee EN, Keglovitz Baker K, Malcolm NM, Rollison JM, Frederiksen BN. Providing quality family planning services to LGBTQIA individuals: a systematic review. Contraception. 2018;97(5):378-391.

Rafferty J Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Adolescence; Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162.

Klein DA, Ellzy JA, Olson J. Care of a transgender adolescent. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(2):142-148.

Tate CC, Ledbetter JN, Youssef CP. A two-question method for assessing gender categories in the social and medical sciences. J Sex Res. 2013;50(8):767-776.

Keuroghlian AS, Ard KL, Makadon HJ. Advancing health equity for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people through sexual health education and LGBT-affirming health care environments. Sex Health. 2017;14(1):119-122.

Lee PA, Nordenström A, Houk CP, et al. Global DSD Update Consortium. Global disorders of sex development update since 2006: perceptions, approach and care [published correction appears in Horm Res Paediatr 2016;85(3):180]. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;85(3):158-180.

de Vries AL, Doreleijers TA, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender dysphoric adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(11):1195-1202.

Olson J, Schrager SM, Belzer M, Simons LK, Clark LF. Baseline physiologic and psychosocial characteristics of transgender youth seeking care for gender dysphoria. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(4):374-380.

Becerra-Culqui TA, Liu Y, Nash R, et al. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173845.

Downing JM, Przedworski JM. Health of transgender adults in the U.S., 2014–2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(3):336-344.

Richmond KA, Burnes T, Carroll K. Lost in translation: interpreting systems of trauma for transgender clients. Traumatology. 2012;18(1):45-57.

American Academy of Family Physicians. Reparative therapy. 2016. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/reparative-therapy.html . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Edmiston EK, Donald CA, Sattler AR, Peebles JK, Ehrenfeld JM, Eckstrand KL. Opportunities and gaps in primary care preventative health services for transgender patients: a systemic review. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):216-230.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. USPSTF A and B recommendations. June 2018. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/uspstf-a-and-b-recommendations . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Maraka S, Singh Ospina N, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Sex steroids and cardiovascular outcomes in transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3914-3923.

Singh-Ospina N, Maraka S, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Effect of sex steroids on the bone health of transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3904-3913.

Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):191-198.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization schedules. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/index.html . Accessed July 5, 2018.

Workowski KA, Bolan GA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015 [published correction appears in MMWR Recomm Rep . 2015;64(33):924]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

Costa R, Colizzi M. The effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on gender dysphoria individuals' mental health: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1953-1966.

de Vries AL, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, Wagenaar EC, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):696-704.

Gómez-Gil E, Zubiaurre-Elorza L, Esteva I, et al. Hormone-treated transsexuals report less social distress, anxiety and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(5):662-670.

Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, et al. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(2):214-231.

Steensma TD, Biemond R, de Boer F, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Desisting and persisting gender dysphoria after childhood: a qualitative follow-up study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;16(4):499-516.

de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J Sex Med. 2011;8(8):2276-2283.

Meriggiola MC, Gava G. Endocrine care of transpeople part I. A review of cross-sex hormonal treatments, outcomes and adverse effects in transmen. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;83(5):597-606.

Weinand JD, Safer JD. Hormone therapy in transgender adults is safe with provider supervision; A review of hormone therapy sequelae for transgender individuals. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(2):55-60.

Asscheman H, T'Sjoen G, Lemaire A, et al. Venous thrombo-embolism as a complication of cross-sex hormone treatment of male-to-female transsexual subjects: a review. Andrologia. 2014;46(7):791-795.

Joint R, Chen ZE, Cameron S. Breast and reproductive cancers in the transgender population: a systematic review [published online ahead of print April 28, 2018]. BJOG . https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1471-0528.15258 . Accessed August 25, 2018.

Jacobeit JW, Gooren LJ, Schulte HM. Safety aspects of 36 months of administration of long-acting intramuscular testosterone undecanoate for treatment of female-to-male transgender individuals. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161(5):795-798.

Carel JC, Eugster EA, Rogol A, et al. ; ESPE-LWPES GnRH Analogs Consensus Conference Group. Consensus statement on the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e752-e762.

Kailas M, Lu HM, Rothman EF, Safer JD. Prevalence and types of gender-affirming surgery among a sample of transgender endocrinology patients prior to state expansion of insurance coverage. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(7):780-786.

Landén M, Wålinder J, Lundström B. Clinical characteristics of a total cohort of female and male applicants for sex reassignment: a descriptive study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97(3):189-194.

Steensma TD, McGuire JK, Kreukels BP, Beekman AJ, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Factors associated with desistence and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: a quantitative follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(6):582-590.

Drummond KD, Bradley SJ, Peterson-Badali M, Zucker KJ. A follow-up study of girls with gender identity disorder. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):34-45.

Wallien MS, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Psychosexual outcome of gender-dysphoric children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(12):1413-1423.

Olson KR, Durwood L, DeMeules M, McLaughlin KA. Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities [published correction appears in Pediatrics . 2016;137(3):e20153223]. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20153223.

Johns MM, Beltran O, Armstrong HL, Jayne PE, Barrios LC. Protective factors among transgender and gender variant youth: a systematic review by socioecological level. J Prim Prev. 2018;39(3):263-301.

Toomey RB, Ryan C, Diaz RM, Card NA, Russell ST. Gender-nonconforming lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: school victimization and young adult psychosocial adjustment. Dev Psychol. 2010;46(6):1580-1589.

de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Cohen-Kettenis PT, VanderLaan DP, Zucker KJ. Poor peer relations predict parent- and self-reported behavioral and emotional problems of adolescents with gender dysphoria: a cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;25(6):579-588.

Chew D, Anderson J, Williams K, May T, Pang K. Hormonal treatment in young people with gender dysphoria: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173742.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2018 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Masks Strongly Recommended but Not Required in Maryland, Starting Immediately

Due to the downward trend in respiratory viruses in Maryland, masking is no longer required but remains strongly recommended in Johns Hopkins Medicine clinical locations in Maryland. Read more .

- Vaccines

- Masking Guidelines

- Visitor Guidelines

Preparing for Gender Affirmation Surgery: Ask the Experts

Featured Expert:

Romy Smith, LMSW

Preparing for your gender affirmation surgery can be daunting. To help provide some guidance for those considering gender affirmation procedures, our team from the Johns Hopkins Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health (JHCTGEH) answered some questions about what to expect before and after your surgery.

What kind of care should I expect as a transgender individual?

What kind of care should I expect as a transgender individual? Before beginning the process, we recommend reading the World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards Of Care (SOC). The standards were created by international agreement among health care clinicians and in collaboration with the transgender community. These SOC integrate the latest scientific research on transgender health, as well as the lived experience of the transgender community members. This collaboration is crucial so that doctors can best meet the unique health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse people. It is usually a favorable sign if the hospital you choose for your gender affirmation surgery follows or references these standards in their transgender care practices.

Can I still have children after gender affirmation surgery?

Many transgender individuals choose to undergo fertility preservation before their gender affirmation surgery if having biological children is part of their long-term goals. Discuss all your options, such as sperm banking and egg freezing, with your doctor so that you can create the best plan for future family building. JHCTGEH has fertility specialists on staff to meet with you and develop a plan that meets your goals.

Are there other ways I need to prepare?

It is very important to prepare mentally for your surgery. If you haven’t already done so, talk to people who have undergone gender affirmation surgeries or read first-hand accounts. These conversations and articles may be helpful; however, keep in mind that not everything you read will apply to your situation. If you have questions about whether something applies to your individual care, it is always best to talk to your doctor.

You will also want to think about your recovery plan post-surgery. Do you have friends or family who can help care for you in the days after your surgery? Having a support system is vital to your continued health both right after surgery and long term. Most centers have specific discharge instructions that you will receive after surgery. Ask if you can receive a copy of these instructions in advance so you can familiarize yourself with the information.

An initial intake interview via phone with a clinical specialist.