Module 12: Money and Banking

Measuring money: currency, m1, and m2, learning objectives.

- Contrast and classify monies as either M1 money supply and M2 money supply

We defined money as anything that is generally accepted as a means of payment, is a store of value, can be used as a unit of account or a standard of deferred payment. What exactly is included?

Cash in your pocket certainly serves as money; however, what about checks or credit cards? Are they money, too? Rather than trying to state a single way of measuring money, economists offer broader definitions of money based on liquidity. Liquidity refers to how quickly you can use a financial asset to buy a good or service. For example, cash is very liquid. You can use your $10 bill easily to buy a hamburger at lunchtime. However, $10 that you have in your savings account is not so easy to use. You must go to the bank or ATM machine and withdraw that cash to buy your lunch. Thus, $10 in your savings account is less liquid.

The Federal Reserve Bank, which is the central bank of the United States, is a bank regulator and is responsible for monetary policy and defines money according to its liquidity. There are two definitions of money: M1 and M2 money supply.

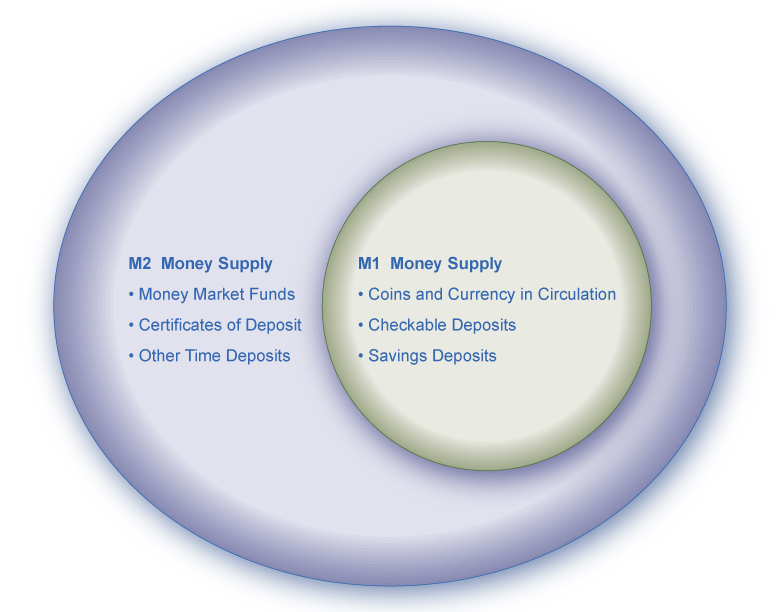

Historically, M1 money supply included those monies that are very liquid such as cash, checkable (demand) deposits, and traveler’s checks, while M2 money supply included those monies that are less liquid in nature; M2 included M1 plus savings and time deposits, certificates of deposits, and money market funds. Beginning in May 2020, the Federal Reserve changed the definition of both M1 and M2. The biggest change is that savings moved to be part of M1. M1 money supply now includes cash, checkable (demand) deposits, and savings. M2 money supply is now measured as M1 plus time deposits, certificates of deposits, and money market funds.

M1 money supply includes coins and currency in circulation—the coins and bills that circulate in an economy that the U.S. Treasury does not hold at the Federal Reserve Bank, or in bank vaults. Closely related to currency are checkable deposits, also known as demand deposits . These are the amounts held in checking accounts. They are called demand deposits or checkable deposits because the banking institution must give the deposit holder his money “on demand” when the customer writes a check or uses a debit card. These items together—currency, and checking accounts in banks—comprise the definition of money known as M1, which the Federal Reserve System measures daily.

As mentioned, M1 now includes savings deposits in banks, which are bank accounts on which you cannot write a check directly, but from which you can easily withdraw the money at an automatic teller machine or bank.

A broader definition of money, M2 includes everything in M1 but also adds other types of deposits. Many banks and other financial institutions also offer a chance to invest in money market funds, where they pool together the deposits of many individual investors and invest them in a safe way, such as short-term government bonds. Another ingredient of M2 are the relatively small (that is, less than about $100,000) certificates of deposit (CDs) or time deposits, which are accounts that the depositor has committed to leaving in the bank for a certain period of time, ranging from a few months to a few years, in exchange for a higher interest rate. In short, all these types of M2 are money that you can withdraw and spend, but which require a greater effort to do so than the items in M1. Figure 14.3 should help in visualizing the relationship between M1 and M2. Note that M1 is included in the M2 calculation.

Figure 1 . The Relationship between M1 and M2 Money. M1 and M2 money are the two mostly commonly used definitions of money. M1 = coins and currency in circulation + checkable (demand) deposit + traveler’s checks + saving deposits. M2 = M1 + money market funds + certificates of deposit + other time deposits.

The Federal Reserve System is responsible for tracking the amounts of M1 and M2 and prepares a weekly release of information about the money supply. To provide an idea of what these amounts sound like, according to the Federal Reserve Bank’s measure of the U.S. money stock, at the end of November 2021, M1 in the United States was $20.3 trillion, while M2 was $21.4 trillion. The table provides a breakdown of the portion of each type of money that comprised M1 and M2 in November 2021, as provided by the Federal Reserve Bank.

The lines separating M1 and M2 can become a little blurry. Sometimes businesses do not treat elements of M1 alike. For example, some businesses will not accept personal checks for large amounts, but will accept traveler’s checks or cash. Changes in banking practices and technology have made the savings accounts in M2 more similar to the checking accounts in M1. For example, some savings accounts will allow depositors to write checks, use automatic teller machines, and pay bills over the internet, which has made it easier to access savings accounts. As with many other economic terms and statistics, the important point is to know the strengths and limitations of the various definitions of money, not to believe that such definitions are as clear-cut to economists as, say, the definition of nitrogen is to chemists.

Where does “plastic money” like debit cards, credit cards, and smart money fit into this picture? A debit card , like a check, is an instruction to the user’s bank to transfer money directly and immediately from your bank account to the seller. It is important to note that in our definition of money, it is checkable deposits that are money, not the paper check or the debit card. Although you can make a purchase with a credit card , the financial institution does not consider it money but rather a short term loan from the credit card company to you. When you make a credit card purchase, the credit card company immediately transfers money from its checking account to the seller, and at the end of the month, the credit card company sends you a bill for what you have charged that month. Until you pay the credit card bill, you have effectively borrowed money from the credit card company. With a smart card , you can store a certain value of money on the card and then use the card to make purchases. Some “smart cards” used for specific purposes, like long-distance phone calls or making purchases at a campus bookstore and cafeteria, are not really all that smart, because you can only use them for certain purchases or in certain places.

In short, credit cards, debit cards, and smart cards are different ways to move money when you make a purchase. However, having more credit cards or debit cards does not change the quantity of money in the economy, any more than printing more checks increases the amount of money in your checking account.

One key message underlying this discussion of M1 and M2 is that money in a modern economy is not just paper bills and coins. Instead, money is closely linked to bank accounts. The banking system largely conducts macroeconomic policies concerning money.

These questions allow you to get as much practice as you need, as you can click the link at the top of the first question (“Try another version of these questions”) to get a new set of questions. Practice until you feel comfortable doing the questions.

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Measuring Money: Currency, M1, and M2. Authored by : OpenStax College. Provided by : Rice University. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:yseWZpUg/Measuring-Money-Currency-M1-an . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/donate/download/[email protected]/pdf

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

AP®︎/College Macroeconomics

Course: ap®︎/college macroeconomics > unit 4.

- Money supply: M0, M1, and M2

- Functions of money

- When the functions of money break down: Hyperinflation

- Commodity money vs. Fiat money

Lesson summary: definition, measurement, and functions of money

- Definition, measurement, and functions of money

Lesson summary

Key takeaway: the three functions of money.

- a medium of exchange

- a store of value

- a unit of account

A Medium of exchange.

A store of value., a unit of account., common misperceptions.

- Monetary aggregates might be easy to confuse with each other. An easy way to remember them is that the higher the number on the aggregate is, the less liquid that kind of money is. M2 is less liquid than M1.

- It might be confusing that checking accounts are considered narrow money, but savings accounts are considered near money. The reason for this is that savings accounts tend to have some limitations on them that checking accounts usually do not. Most checking accounts are demand deposit. Savings accounts frequently will have limitations such as being only able to make five withdrawals per month or having to wait ten days after you deposit money to get them.

- You might see a reference to an even broader monetary aggregate in your textbook or class and be confused why it isn't here. The monetary aggregate M3 is tracked in some countries, but not others (the U.S. stopped tracking this category in 2006). If you see M3 elsewhere, the most important thing to remember about it is that M3 is less liquid than M2. In fact, you might even see a broader category called L, which is even less liquid than M3.

- Are cryptocurrencies money? There is actually some debate about whether cryptocurrencies (such as bitcoin) are money or just a financial asset. In fact, central banks around the world are grappling with this question right now, and there isn’t any consensus on this issue. A main sticking point to argue that cryptocurrencies aren’t money is that they generally cannot be used as legal tender (in other words, to buy stuff). Not a lot of stores are equipped to take cryptocurrencies to buy goods and services, at least not yet. As of right now, cryptocurrencies aren’t included in either the narrow or broad definition of the money supply.

- Describe what function money is fulfilling in each of these situations

- The nation of Jacksonia uses the Jacksonian Yen as its currency. Their currency is fiat money that is not commodity-backed. The table below describes all of the assets that exist with Jacksonia

- When there is hyperinflation, which function of money will fail first? Explain.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Money Basics - Assessing How You Manage Money

Money basics -, assessing how you manage money, money basics assessing how you manage money.

Money Basics: Assessing How You Manage Money

Lesson 3: assessing how you manage money.

/en/moneybasics/financial-problem-solving-strategies/content/

Assessing how you manage money

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Recognize how to manage money

- Judge if it's time to change the way you manage money

- Identify steps you can take to better manage money

- Set financial goals and objectives

How do you manage money?

Every day you make choices about how, where, and when you will spend your money . These choices can have a significant affect on your financial life . Do you spend a lot of money on credit card debt each month? Do you save money regularly? Do you treat yourself to things after a rough week at work?

To get an idea of how you relate to money, take our Money Basics quiz . Choose the answer that most applies to you.

Where does your money go?

If you don't keep track of your expenses , you don't know how you spend your money. When you know where your money goes, you feel more in control. Take time to think about your spending. Ask yourself:

- Do I have a good idea of how much I spend each week or month?

- Do I take care of the essentials first—such as food, utilities, rent, and medical insurance—before spending money on other things?

- Do I have a huge balance on my credit card(s)?

- Am I a savvy shopper?

- Do I save money regularly?

- Do I have three months of living expenses saved?

- Do I have specific goals I'm planning for financially?

Read on to find out how you might change the way you manage your money.

Changing the way you spend money

When assessing how you manage your money, you might want to change your spending and saving habits . Being able to better manage your money will help you prepare for the future.

Bad money management habits can sometimes be difficult to break. To tackle an undesirable habit, consider the following:

- What do I get out of it? If you spend a lot of money but save just a little, what do you get out of it? You get to enjoy stuff, whether it's one more pair of black shoes to add to the five pairs you already own or a new big-screen TV.

- What's the negative? If you go on a shopping spree and don't pay your electric bill, you gain temporary stuff but may lose an important service. If you don't save money, what could happen if an emergency arises? If you look at it this way, you may realize you're not making a good choice.

- Think before you spend. Each time you spend money, you are making a choice. Your choices should reflect your values and financial goals. Before spending, ask yourself, "Do I need it?", "Can I afford it?", and "What is this purchase really costing me?"

- Find a good habit. If you want to get rid of a bad habit related to money management, replace it with a good habit. For example, instead of overspending on designer clothes, start setting aside money for a down payment on a house or other goal. You must truly want to get rid of the bad habit, and you must practice and work at it in order to change.

Eight steps to better money management

As you work toward managing your money more effectively, keep these steps in mind:

1. Plan ahead . Write down your goals and objectives. It's important to be realistic. Will you more likely be able to afford a $200,000 house or one that costs $100,000 or less? Review your goals and objectives regularly to see if you are on track.

2. Create a budget . Make a plan for how you will spend and save money. Update it regularly, and evaluate your goals. Think about your financial situation, where you need to be, and determine how you're going to get there. (You'll learn more about creating a budget in the next lesson.)

3. Keep good records . It's difficult to get your finances under control if you don't understand the basics of good record-keeping. Keeping track of your bills, checks, and other financial transactions is important.

4. Stay insured . Purchase insurance to avoid being hit with a financial loss due to accident or illness. It's an important part of your financial plan.

5. Stay focused . You'll need patience and discipline to start your financial plan and follow through with it. Don't be tempted to overspend.

6. Save more . It's important to save money regularly so you can use it in the future. Begin by faithfully saving a small amount. If you are able to save enough money, you will be able to put some into investments, use it in emergencies, or use it to reach your goals.

7. Educate yourself . No one can protect you from your own bad judgment. Get the information you need to avoid financial trouble, and make thoughtful decisions that can improve your financial security.

8. Take time . Set aside time each month to work on your money management. Pick a time that works for you, such as early in the morning when everyone else is asleep or quiet time at night. You will find that it's time well spent.

Setting goals

Goal setting is an important part of success, whether you're aspiring to reach objectives at school, at work, or in your personal life. Aim too high, and you may get frustrated and give up. Aim too low, and you might not push yourself to reach your full potential.

Think about your financial goals and how you plan to reach them.

- What do you want your financial picture to look like in one year? In five years? In 10 years?

- Do you want to buy a car or house, start a business, or pay off debt?

- What do you need to change to reach your goals?

- How can you make the best use of your money?

Don't worry. You may not have all the answers now. The lessons in this course can help you clearly define your financial goals and help you take steps to achieve them.

To help you get started, use our Goals Worksheet .

/en/moneybasics/creating-a-budget/content/

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

24.2 The Banking System and Money Creation

Learning objectives.

- Explain what banks are, what their balance sheets look like, and what is meant by a fractional reserve banking system.

- Describe the process of money creation (destruction), using the concept of the deposit multiplier.

- Describe how and why banks are regulated and insured.

Where does money come from? How is its quantity increased or decreased? The answer to these questions suggests that money has an almost magical quality: money is created by banks when they issue loans . In effect, money is created by the stroke of a pen or the click of a computer key.

We will begin by examining the operation of banks and the banking system. We will find that, like money itself, the nature of banking is experiencing rapid change.

Banks and Other Financial Intermediaries

An institution that amasses funds from one group and makes them available to another is called a financial intermediary . A pension fund is an example of a financial intermediary. Workers and firms place earnings in the fund for their retirement; the fund earns income by lending money to firms or by purchasing their stock. The fund thus makes retirement saving available for other spending. Insurance companies are also financial intermediaries, because they lend some of the premiums paid by their customers to firms for investment. Mutual funds make money available to firms and other institutions by purchasing their initial offerings of stocks or bonds.

Banks play a particularly important role as financial intermediaries. Banks accept depositors’ money and lend it to borrowers. With the interest they earn on their loans, banks are able to pay interest to their depositors, cover their own operating costs, and earn a profit, all the while maintaining the ability of the original depositors to spend the funds when they desire to do so. One key characteristic of banks is that they offer their customers the opportunity to open checking accounts, thus creating checkable deposits. These functions define a bank , which is a financial intermediary that accepts deposits, makes loans, and offers checking accounts.

Over time, some nonbank financial intermediaries have become more and more like banks. For example, some brokerage firms offer customers interest-earning accounts and make loans. They now allow their customers to write checks on their accounts.

As nonbank financial intermediaries have grown, banks’ share of the nation’s credit market financial assets has diminished. In 1972, banks accounted for nearly 30% of U.S. credit market financial assets. In 2007, that share had dropped to about 15%.

The fact that banks account for a declining share of U.S. financial assets alarms some observers. We will see that banks are more tightly regulated than are other financial institutions; one reason for that regulation is to maintain control over the money supply. Other financial intermediaries do not face the same regulatory restrictions as banks. Indeed, their freedom from regulation is one reason they have grown so rapidly. As other financial intermediaries become more important, central authorities begin to lose control over the money supply.

The declining share of financial assets controlled by “banks” began to change in 2008. Many of the nation’s largest investment banks—financial institutions that provided services to firms but were not regulated as commercial banks—began having serious financial difficulties as a result of their investments tied to home mortgage loans. As home prices in the United States began falling, many of those mortgage loans went into default. Investment banks that had made substantial purchases of securities whose value was ultimately based on those mortgage loans themselves began failing. Bear Stearns, one of the largest investment banks in the United States, required federal funds to remain solvent. Another large investment bank, Lehman Brothers, failed. In an effort to avoid a similar fate, several other investment banks applied for status as ordinary commercial banks subject to the stringent regulation those institutions face. One result of the terrible financial crisis that crippled the U.S. and other economies in 2008 may be greater control of the money supply by the Fed.

Bank Finance and a Fractional Reserve System

Bank finance lies at the heart of the process through which money is created. To understand money creation, we need to understand some of the basics of bank finance.

Banks accept deposits and issue checks to the owners of those deposits. Banks use the money collected from depositors to make loans. The bank’s financial picture at a given time can be depicted using a simplified balance sheet , which is a financial statement showing assets, liabilities, and net worth. Assets are anything of value. Liabilities are obligations to other parties. Net worth equals assets less liabilities. All these are given dollar values in a firm’s balance sheet. The sum of liabilities plus net worth therefore must equal the sum of all assets. On a balance sheet, assets are listed on the left, liabilities and net worth on the right.

The main way that banks earn profits is through issuing loans. Because their depositors do not typically all ask for the entire amount of their deposits back at the same time, banks lend out most of the deposits they have collected—to companies seeking to expand their operations, to people buying cars or homes, and so on. Banks keep only a fraction of their deposits as cash in their vaults and in deposits with the Fed. These assets are called reserves . Banks lend out the rest of their deposits. A system in which banks hold reserves whose value is less than the sum of claims outstanding on those reserves is called a fractional reserve banking system .

Table 24.1 “The Consolidated Balance Sheet for U.S. Commercial Banks, October 2010” shows a consolidated balance sheet for commercial banks in the United States for October 2010. Banks hold reserves against the liabilities represented by their checkable deposits. Notice that these reserves were a small fraction of total deposit liabilities of that month. Most bank assets are in the form of loans.

Table 24.1 The Consolidated Balance Sheet for U.S. Commercial Banks, October 2010

This balance sheet for all commercial banks in the United States shows their financial situation in billions of dollars, seasonally adjusted, on October 2010.

Source : Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.8, December 3, 2010.

In the next section, we will learn that money is created when banks issue loans.

Money Creation

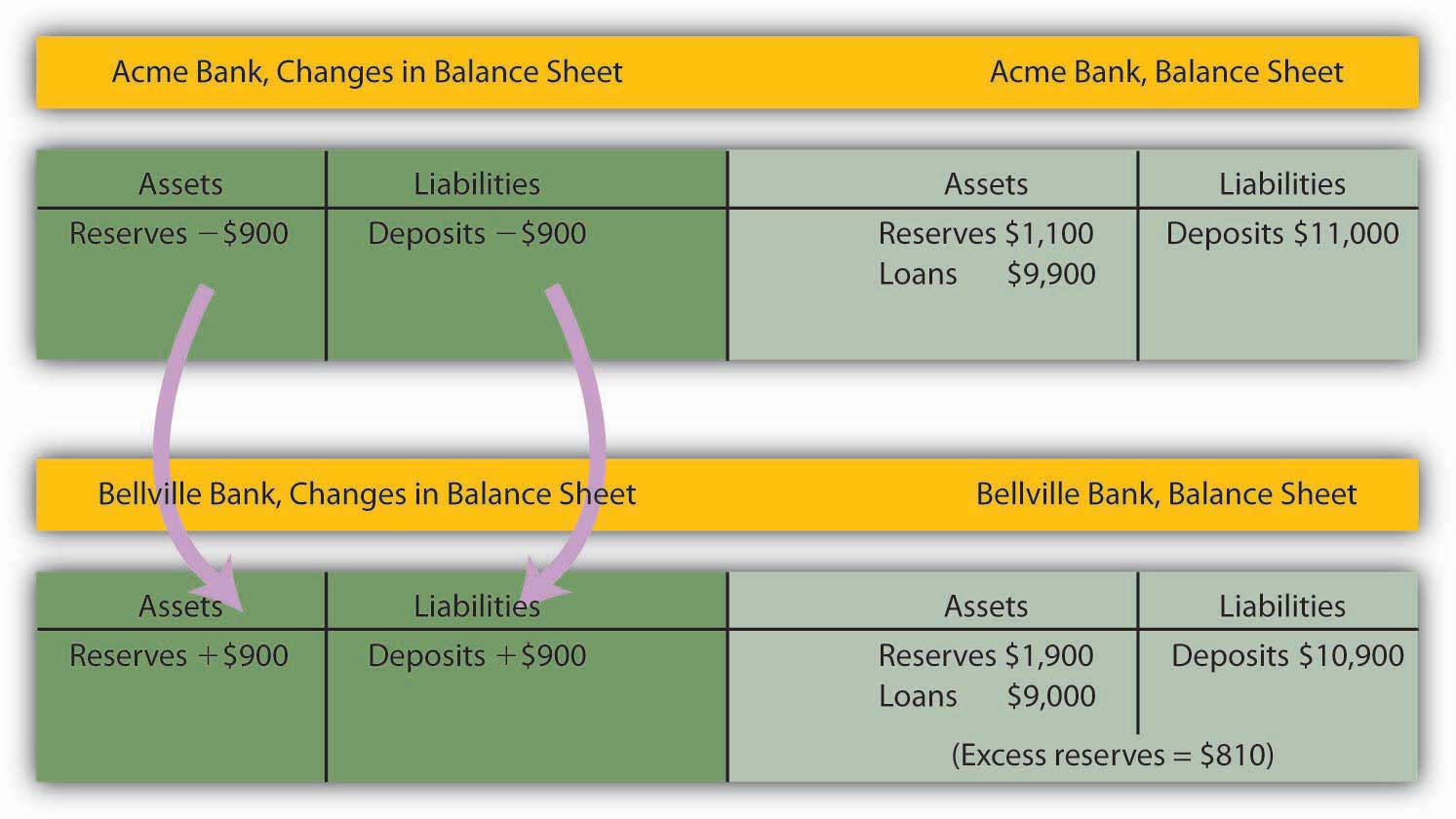

To understand the process of money creation today, let us create a hypothetical system of banks. We will focus on three banks in this system: Acme Bank, Bellville Bank, and Clarkston Bank. Assume that all banks are required to hold reserves equal to 10% of their checkable deposits. The quantity of reserves banks are required to hold is called required reserves . The reserve requirement is expressed as a required reserve ratio ; it specifies the ratio of reserves to checkable deposits a bank must maintain. Banks may hold reserves in excess of the required level; such reserves are called excess reserves . Excess reserves plus required reserves equal total reserves.

Because banks earn relatively little interest on their reserves held on deposit with the Federal Reserve, we shall assume that they seek to hold no excess reserves. When a bank’s excess reserves equal zero, it is loaned up . Finally, we shall ignore assets other than reserves and loans and deposits other than checkable deposits. To simplify the analysis further, we shall suppose that banks have no net worth; their assets are equal to their liabilities.

Let us suppose that every bank in our imaginary system begins with $1,000 in reserves, $9,000 in loans outstanding, and $10,000 in checkable deposit balances held by customers. The balance sheet for one of these banks, Acme Bank, is shown in Table 24.2 “A Balance Sheet for Acme Bank” . The required reserve ratio is 0.1: Each bank must have reserves equal to 10% of its checkable deposits. Because reserves equal required reserves, excess reserves equal zero. Each bank is loaned up.

Table 24.2 A Balance Sheet for Acme Bank

We assume that all banks in a hypothetical system of banks have $1,000 in reserves, $10,000 in checkable deposits, and $9,000 in loans. With a 10% reserve requirement, each bank is loaned up; it has zero excess reserves.

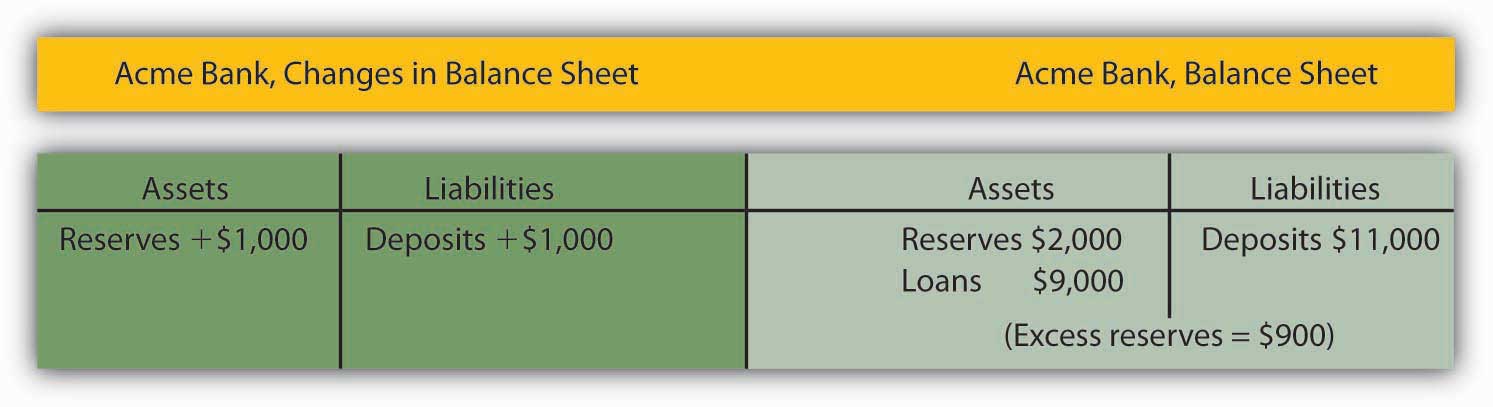

Acme Bank, like every other bank in our hypothetical system, initially holds reserves equal to the level of required reserves. Now suppose one of Acme Bank’s customers deposits $1,000 in cash in a checking account. The money goes into the bank’s vault and thus adds to reserves. The customer now has an additional $1,000 in his or her account. Two versions of Acme’s balance sheet are given here. The first shows the changes brought by the customer’s deposit: reserves and checkable deposits rise by $1,000. The second shows how these changes affect Acme’s balances. Reserves now equal $2,000 and checkable deposits equal $11,000. With checkable deposits of $11,000 and a 10% reserve requirement, Acme is required to hold reserves of $1,100. With reserves equaling $2,000, Acme has $900 in excess reserves.

At this stage, there has been no change in the money supply. When the customer brought in the $1,000 and Acme put the money in the vault, currency in circulation fell by $1,000. At the same time, the $1,000 was added to the customer’s checking account balance, so the money supply did not change.

Figure 24.3

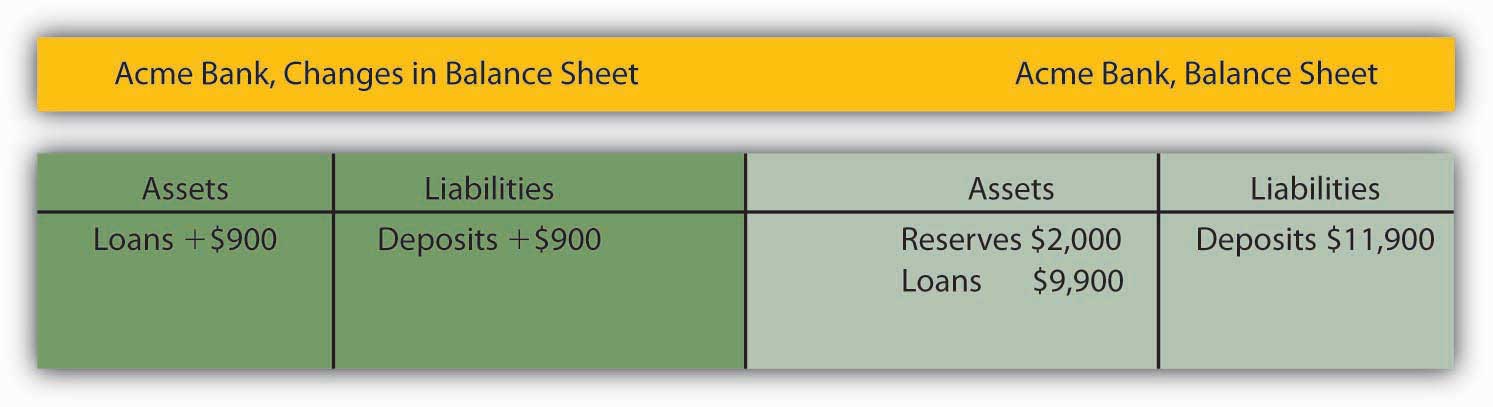

Because Acme earns only a low interest rate on its excess reserves, we assume it will try to loan them out. Suppose Acme lends the $900 to one of its customers. It will make the loan by crediting the customer’s checking account with $900. Acme’s outstanding loans and checkable deposits rise by $900. The $900 in checkable deposits is new money; Acme created it when it issued the $900 loan. Now you know where money comes from—it is created when a bank issues a loan.

Figure 24.4

Presumably, the customer who borrowed the $900 did so in order to spend it. That customer will write a check to someone else, who is likely to bank at some other bank. Suppose that Acme’s borrower writes a check to a firm with an account at Bellville Bank. In this set of transactions, Acme’s checkable deposits fall by $900. The firm that receives the check deposits it in its account at Bellville Bank, increasing that bank’s checkable deposits by $900. Bellville Bank now has a check written on an Acme account. Bellville will submit the check to the Fed, which will reduce Acme’s deposits with the Fed—its reserves—by $900 and increase Bellville’s reserves by $900.

Figure 24.5

Notice that Acme Bank emerges from this round of transactions with $11,000 in checkable deposits and $1,100 in reserves. It has eliminated its excess reserves by issuing the loan for $900; Acme is now loaned up. Notice also that from Acme’s point of view, it has not created any money! It merely took in a $1,000 deposit and emerged from the process with $1,000 in additional checkable deposits.

The $900 in new money Acme created when it issued a loan has not vanished—it is now in an account in Bellville Bank. Like the magician who shows the audience that the hat from which the rabbit appeared was empty, Acme can report that it has not created any money. There is a wonderful irony in the magic of money creation: banks create money when they issue loans, but no one bank ever seems to keep the money it creates. That is because money is created within the banking system, not by a single bank.

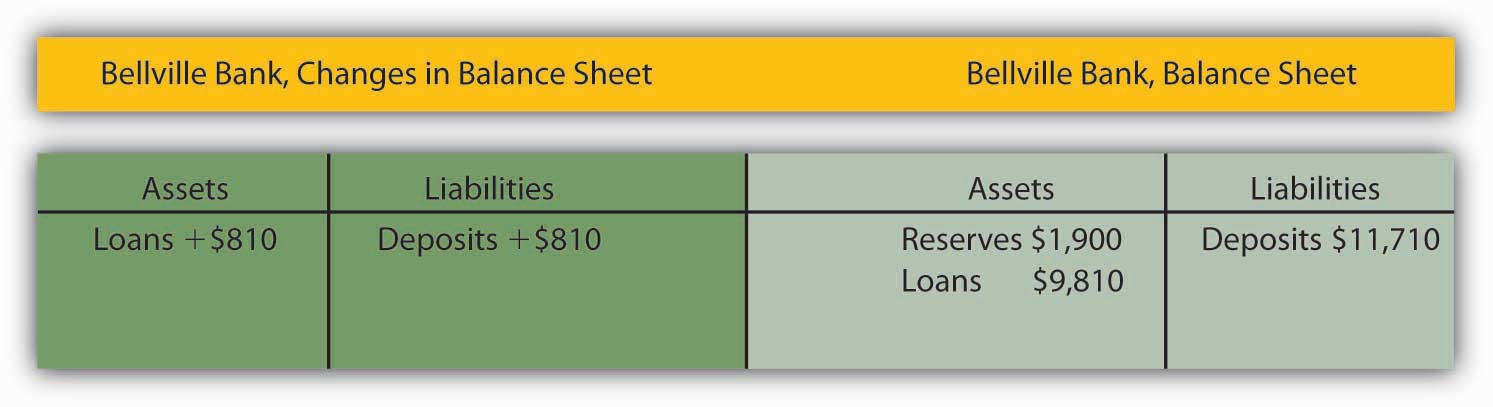

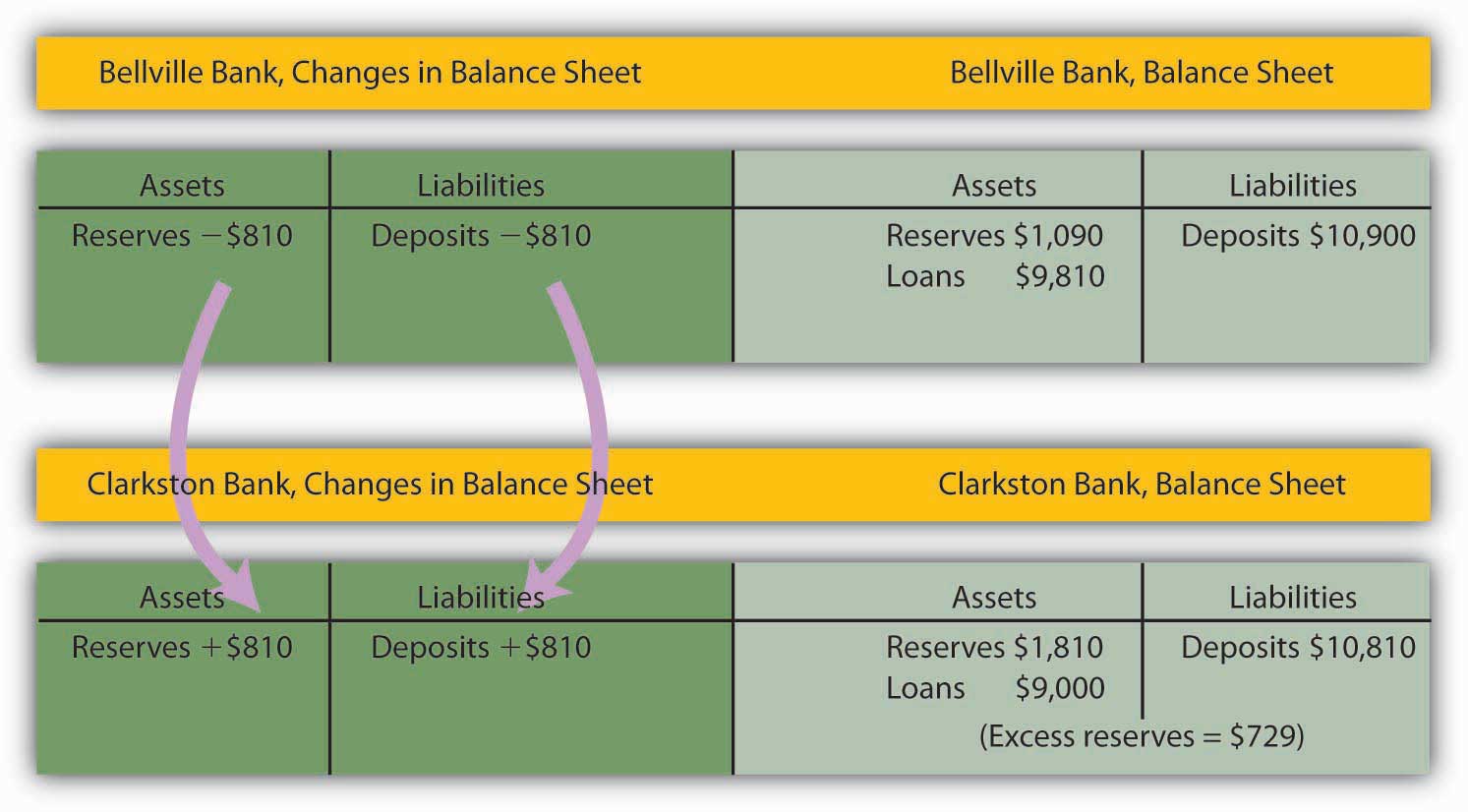

The process of money creation will not end there. Let us go back to Bellville Bank. Its deposits and reserves rose by $900 when the Acme check was deposited in a Bellville account. The $900 deposit required an increase in required reserves of $90. Because Bellville’s reserves rose by $900, it now has $810 in excess reserves. Just as Acme lent the amount of its excess reserves, we can expect Bellville to lend this $810. The next set of balance sheets shows this transaction. Bellville’s loans and checkable deposits rise by $810.

Figure 24.6

The $810 that Bellville lent will be spent. Let us suppose it ends up with a customer who banks at Clarkston Bank. Bellville’s checkable deposits fall by $810; Clarkston’s rise by the same amount. Clarkston submits the check to the Fed, which transfers the money from Bellville’s reserve account to Clarkston’s. Notice that Clarkston’s deposits rise by $810; Clarkston must increase its reserves by $81. But its reserves have risen by $810, so it has excess reserves of $729.

Figure 24.7

Notice that Bellville is now loaned up. And notice that it can report that it has not created any money either! It took in a $900 deposit, and its checkable deposits have risen by that same $900. The $810 it created when it issued a loan is now at Clarkston Bank.

The process will not end there. Clarkston will lend the $729 it now has in excess reserves, and the money that has been created will end up at some other bank, which will then have excess reserves—and create still more money. And that process will just keep going as long as there are excess reserves to pass through the banking system in the form of loans. How much will ultimately be created by the system as a whole? With a 10% reserve requirement, each dollar in reserves backs up $10 in checkable deposits. The $1,000 in cash that Acme’s customer brought in adds $1,000 in reserves to the banking system. It can therefore back up an additional $10,000! In just the three banks we have shown, checkable deposits have risen by $2,710 ($1,000 at Acme, $900 at Bellville, and $810 at Clarkston). Additional banks in the system will continue to create money, up to a maximum of $7,290 among them. Subtracting the original $1,000 that had been a part of currency in circulation, we see that the money supply could rise by as much as $9,000.

Notice that when the banks received new deposits, they could make new loans only up to the amount of their excess reserves, not up to the amount of their deposits and total reserve increases. For example, with the new deposit of $1,000, Acme Bank was able to make additional loans of $900. If instead it made new loans equal to its increase in total reserves, then after the customers who received new loans wrote checks to others, its reserves would be less than the required amount. In the case of Acme, had it lent out an additional $1,000, after checks were written against the new loans, it would have been left with only $1,000 in reserves against $11,000 in deposits, for a reserve ratio of only 0.09, which is less than the required reserve ratio of 0.1 in the example.

The Deposit Multiplier

We can relate the potential increase in the money supply to the change in reserves that created it using the deposit multiplier ( m d ), which equals the ratio of the maximum possible change in checkable deposits (∆ D ) to the change in reserves (∆ R ). In our example, the deposit multiplier was 10:

Equation 24.1

[latex]m_d = \frac{ \Delta D}{ \Delta R} = \frac{ \$ 10,000}{ \$ 1,000} = 10[/latex]

To see how the deposit multiplier m d is related to the required reserve ratio, we use the fact that if banks in the economy are loaned up, then reserves, R , equal the required reserve ratio ( rrr ) times checkable deposits, D :

Equation 24.2

[latex]R = rrrD[/latex]

A change in reserves produces a change in loans and a change in checkable deposits. Once banks are fully loaned up, the change in reserves, ∆ R , will equal the required reserve ratio times the change in deposits, ∆ D :

Equation 24.3

[latex]\Delta R = rrr \Delta D[/latex]

Solving for ∆ D , we have

Equation 24.4

[latex]\frac{1}{rrr} \Delta R = \Delta D[/latex]

Dividing both sides by ∆ R , we see that the deposit multiplier, m d , is 1/ rrr :

Equation 24.5

[latex]\frac{1}{rrr} = \frac{ \Delta D}{ \Delta R} = m_d[/latex]

The deposit multiplier is thus given by the reciprocal of the required reserve ratio . With a required reserve ratio of 0.1, the deposit multiplier is 10. A required reserve ratio of 0.2 would produce a deposit multiplier of 5. The higher the required reserve ratio, the lower the deposit multiplier.

Actual increases in checkable deposits will not be nearly as great as suggested by the deposit multiplier. That is because the artificial conditions of our example are not met in the real world. Some banks hold excess reserves, customers withdraw cash, and some loan proceeds are not spent. Each of these factors reduces the degree to which checkable deposits are affected by an increase in reserves. The basic mechanism, however, is the one described in our example, and it remains the case that checkable deposits increase by a multiple of an increase in reserves.

The entire process of money creation can work in reverse. When you withdraw cash from your bank, you reduce the bank’s reserves. Just as a deposit at Acme Bank increases the money supply by a multiple of the original deposit, your withdrawal reduces the money supply by a multiple of the amount you withdraw. And just as money is created when banks issue loans, it is destroyed as the loans are repaid. A loan payment reduces checkable deposits; it thus reduces the money supply.

Suppose, for example, that the Acme Bank customer who borrowed the $900 makes a $100 payment on the loan. Only part of the payment will reduce the loan balance; part will be interest. Suppose $30 of the payment is for interest, while the remaining $70 reduces the loan balance. The effect of the payment on Acme’s balance sheet is shown below. Checkable deposits fall by $100, loans fall by $70, and net worth rises by the amount of the interest payment, $30.

Similar to the process of money creation, the money reduction process decreases checkable deposits by, at most, the amount of the reduction in deposits times the deposit multiplier.

Figure 24.8

The Regulation of Banks

Banks are among the most heavily regulated of financial institutions. They are regulated in part to protect individual depositors against corrupt business practices. Banks are also susceptible to crises of confidence. Because their reserves equal only a fraction of their deposit liabilities, an effort by customers to get all their cash out of a bank could force it to fail. A few poorly managed banks could create such a crisis, leading people to try to withdraw their funds from well-managed banks. Another reason for the high degree of regulation is that variations in the quantity of money have important effects on the economy as a whole, and banks are the institutions through which money is created.

Deposit Insurance

From a customer’s point of view, the most important form of regulation comes in the form of deposit insurance. For commercial banks, this insurance is provided by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Insurance funds are maintained through a premium assessed on banks for every $100 of bank deposits.

If a commercial bank fails, the FDIC guarantees to reimburse depositors up to $250,000 (raised from $100,000 during the financial crisis of 2008) per insured bank, for each account ownership category. From a depositor’s point of view, therefore, it is not necessary to worry about a bank’s safety.

One difficulty this insurance creates, however, is that it may induce the officers of a bank to take more risks. With a federal agency on hand to bail them out if they fail, the costs of failure are reduced. Bank officers can thus be expected to take more risks than they would otherwise, which, in turn, makes failure more likely. In addition, depositors, knowing that their deposits are insured, may not scrutinize the banks’ lending activities as carefully as they would if they felt that unwise loans could result in the loss of their deposits.

Thus, banks present us with a fundamental dilemma. A fractional reserve system means that banks can operate only if their customers maintain their confidence in them. If bank customers lose confidence, they are likely to try to withdraw their funds. But with a fractional reserve system, a bank actually holds funds in reserve equal to only a small fraction of its deposit liabilities. If its customers think a bank will fail and try to withdraw their cash, the bank is likely to fail. Bank panics, in which frightened customers rush to withdraw their deposits, contributed to the failure of one-third of the nation’s banks between 1929 and 1933. Deposit insurance was introduced in large part to give people confidence in their banks and to prevent failure. But the deposit insurance that seeks to prevent bank failures may lead to less careful management—and thus encourage bank failure.

Regulation to Prevent Bank Failure

To reduce the number of bank failures, banks are severely limited in what they can do. They are barred from certain types of financial investments and from activities viewed as too risky. Banks are required to maintain a minimum level of net worth as a fraction of total assets. Regulators from the FDIC regularly perform audits and other checks of individual banks to ensure they are operating safely.

The FDIC has the power to close a bank whose net worth has fallen below the required level. In practice, it typically acts to close a bank when it becomes insolvent, that is, when its net worth becomes negative. Negative net worth implies that the bank’s liabilities exceed its assets.

When the FDIC closes a bank, it arranges for depositors to receive their funds. When the bank’s funds are insufficient to return customers’ deposits, the FDIC uses money from the insurance fund for this purpose. Alternatively, the FDIC may arrange for another bank to purchase the failed bank. The FDIC, however, continues to guarantee that depositors will not lose any money.

Key Takeaways

- Banks are financial intermediaries that accept deposits, make loans, and provide checking accounts for their customers.

- Money is created within the banking system when banks issue loans; it is destroyed when the loans are repaid.

- An increase (decrease) in reserves in the banking system can increase (decrease) the money supply. The maximum amount of the increase (decrease) is equal to the deposit multiplier times the change in reserves; the deposit multiplier equals the reciprocal of the required reserve ratio.

- Bank deposits are insured and banks are heavily regulated.

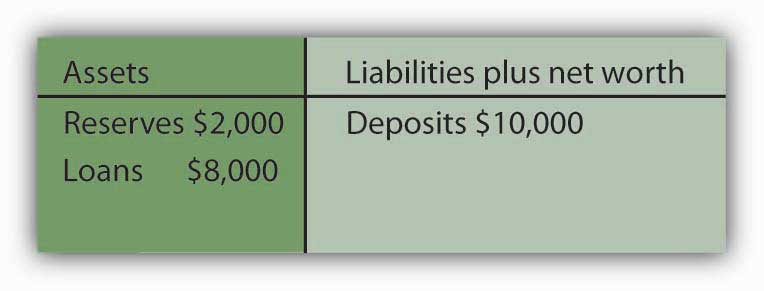

- Suppose Acme Bank initially has $10,000 in deposits, reserves of $2,000, and loans of $8,000. At a required reserve ratio of 0.2, is Acme loaned up? Show the balance sheet of Acme Bank at present.

- Now suppose that an Acme Bank customer, planning to take cash on an extended college graduation trip to India, withdraws $1,000 from her account. Show the changes to Acme Bank’s balance sheet and Acme’s balance sheet after the withdrawal. By how much are its reserves now deficient?

- Acme would probably replenish its reserves by reducing loans. This action would cause a multiplied contraction of checkable deposits as other banks lose deposits because their customers would be paying off loans to Acme. How large would the contraction be?

Case in Point: A Big Bank Goes Under

Figure 24.9

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

It was the darling of Wall Street—it showed rapid growth and made big profits. Washington Mutual, a savings and loan based in the state of Washington, was a relatively small institution whose CEO, Kerry K. Killinger, had big plans. He wanted to transform his little Seattle S&L into the Wal-Mart of banks.

Mr. Killinger began pursuing a relatively straightforward strategy. He acquired banks in large cities such as Chicago and Los Angeles. He acquired banks up and down the east and west coasts. He aggressively extended credit to low-income individuals and families—credit cards, car loans, and mortgages. In making mortgage loans to low-income families, WaMu, as the bank was known, quickly became very profitable. But it was exposing itself to greater and greater risk, according to the New York Times .

Housing prices in the United States more than doubled between 1997 and 2007. During that time, loans to even low-income households were profitable. But, as housing prices began falling in 2007, banks such as WaMu began to experience losses as homeowners began to walk away from houses whose values suddenly fell below their outstanding mortgages. WaMu began losing money in 2007 as housing prices began falling. The company had earned $3.6 billion in 2006, and swung to a loss of $67 million in 2007, according to the Puget Sound Business Journal . Mr. Killinger was ousted by the board early in September of 2008. The bank failed later that month. It was the biggest bank failure in the history of the United States.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had just rescued another bank, IndyMac, which was only a tenth the size of WaMu, and would have done the same for WaMu if it had not been able to find a company to purchase it. But in this case, JPMorgan Chase agreed to take it over—its deposits, bank branches, and its troubled asset portfolio. The government and the Fed even negotiated the deal behind WaMu’s back! The then chief executive officer of the company, Alan H. Fishman, was reportedly flying from New York to Seattle when the deal was finalized.

The government was anxious to broker a deal that did not require use of the FDIC’s depleted funds following IndyMac’s collapse. But it would have done so if a buyer had not been found. As the FDIC reports on its Web site: “Since the FDIC’s creation in 1933, no depositor has ever lost even one penny of FDIC-insured funds.”

Sources : Eric Dash and Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Government Seizes WaMu and Sells Some Assets,” The New York Times , September 25, 2008, p. A1; Kirsten Grind, “Insiders Detail Reasons for WaMu’s Failure,” Puget Sound Business Journal , January 23, 2009; and FDIC Web site at https://www.fdic.gov/edie/fdic_info.html .

Answer to Try It! Problem

Acme Bank is loaned up, since $2,000/$10,000 = 0.2, which is the required reserve ratio. Acme’s balance sheet is:

Figure 24.10

Acme Bank’s balance sheet after losing $1,000 in deposits:

Figure 24.11

Required reserves are deficient by $800. Acme must hold 20% of its deposits, in this case $1,800 (0.2 × $9,000=$1,800), as reserves, but it has only $1,000 in reserves at the moment.

The contraction in checkable deposits would be

∆D = (1/0.2) × (−$1,000) = −$5,000

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is M1?

Understanding m1.

- Money Supply and M1 in the U.S.

How to Calculate M1

Money supply and the u.s. economy, m1 vs. m2 vs. m3, how the m1 money supply changes.

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The Bottom Line

- Monetary Policy

- Federal Reserve

M1 Money Supply: How It Works and How to Calculate It

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Group1805-3b9f749674f0434184ef75020339bd35.jpg)

Investopedia / Jake Shi

M1 is the money supply that is composed of currency, demand deposits, other liquid deposits—which includes savings deposits. M1 includes the most liquid portions of the money supply because it contains currency and assets that either are or can be quickly converted to cash. However, "near money" and "near, near money," which fall under M2 and M3, cannot be converted to currency as quickly.

Key Takeaways

- M1 is a narrow measure of the money supply that includes currency, demand deposits, and other liquid deposits, including savings deposits.

- M1 does not include financial assets, such as bonds.

- The M1 is no longer used as a guide for monetary policy in the U.S. due to the lack of correlation between it and other economic variables.

- The M1 money supply was a much more constrictive measurement of the money supply compared to the M2 or M3 calculation.

- The M1 money supply is reported on a monthly basis by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

M1 money is a country’s basic money supply that's used as a medium of exchange. M1 includes demand deposits and checking accounts, which are the most commonly used exchange mediums through the use of debit cards and ATMs. Of all the components of the money supply, M1 is defined the most narrowly. M1 does not include financial assets, such as bonds. M1 money is the money supply metric most frequently utilized by economists to reference how much money is in circulation in a country.

Note that in May 2020, the definition of M1 changed to include savings accounts given the increased liquidity of such accounts.

Money Supply and M1 in the United States

Up until March 2006, the Federal Reserve published reports on three money aggregates: M1, M2 , and M3 . Since 2006, the Fed no longer publishes M3 data. M1 covers types of money commonly used for payment, which includes the most basic payment form, currency. The amount of currency in circulation or held in deposits at the Federal Reserve is called M0, or the monetary base.

M1 is defined as the sum of all currency in circulation, plus the value of most liquid deposits at commercial banks, except those held by the government, foreign banks, or other depository institutions. Because M1 is so narrowly defined, very few components are classified as M1. The broader classification, M2, also includes savings account deposits, small-time deposits, and retail money market accounts.

Closely related to M1 and M2 is Money Zero Maturity (MZM). MZM consists of M1 plus all money market accounts, including institutional money market funds. MZM represents all assets that are redeemable at par on demand and is designed to estimate the supply of readily circulating liquid money in the economy.

The money supply within the United States is graphically depicted by the Federal Reserve. The graphical depiction lists the money supply in billions of dollars on the y-axis and the date on the x-axis. The information is periodically updated on the Federal Reserve of St. Louis' site.

The M1 money supply is composed of Federal Reserve notes—otherwise known as bills or paper money—and coins that are in circulation outside of the Federal Reserve Banks and the vaults of depository institutions. Paper money is the most significant component of a nation’s money supply.

M1 also includes traveler’s checks (of non-bank issuers), demand deposits, and other checkable deposits (OCDs), including NOW accounts at depository institutions and credit union share draft accounts.

For most central banks, M1 almost always includes money in circulation and readily cashable instruments. But there are slight variations on the definition across the world. For example, M1 in the eurozone also includes overnight deposits. In Australia, it includes current deposits from the private non-bank sector. The United Kingdom, however, does not use M0 or M1 class of money supply any longer; its primary measure is M4, or broad money, also known as the money supply.

M2 and M3 include all of the components of M1 plus additional forms of money, including money market accounts, savings accounts, and institutional funds with significant balances.

For periods of time, measurement of the money supply indicated a close relationship between money supply and some economic variables such as the gross domestic product (GDP), inflation, and price levels. Economists such as Milton Friedman argued in support of the theory that the money supply is intertwined with all of these variables.

However, in the past several decades, the relationship between some measurements of the money supply and other primary economic variables has been uncertain at best. Thus, the significance of the money supply acting as a guide for the conduct of monetary policy in the United States has substantially lessened.

The M1 money supply includes all physical currency, traveler's checks, demand deposits, and other checkable deposits (e.g. checking accounts). While the M1 is a measure of all the most liquid forms of money in an economy, other forms of money supply are slightly different.

The M2 money supply is a broader measure of money supply that includes all components of M1 as well as "near money". M2 includes savings deposits, money market securities, and other time deposits which are less liquid and not as suitable as exchange mediums. Although many elements of the M2 money supply can can still be quickly converted into cash or checking deposits, they are not as instant as the components of the M1 money supply.

On the other hand, the M3 money supply is an even broader measure of the money supply that includes all components of M1 and M2. In addition, it includes all forms of savings deposits, money market deposits, time deposits in amounts of less than $100,000, and institutional money market funds. M3 is arguably the most comprehensive measure of the money supply compared to the other calculated amounts of money supply as it includes a wider range of savings and investments that can be readily converted into cash.

Governments intentionally change the money supply to have residual impacts on the broader economy. For example, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments increased the M1 money supply, making it easier to come about capital to help stimulate the economy, keep workers employed, and encourage business activity.

Central banks can increase the M1 money supply by increasing the amount of physical currency in circulation, lending money to banks, or purchasing securities on the open market. On the other hand, as seen in the aftermath of COVID-19, central banks reverse these policies to cool the economy to fight inflation.

Businesses and consumer spending also have an impact on the M1 money supply. As consumers and businesses spend more money, they create greater demand for that local currency. Therefore, as consumers write checks, use debit cards, or use credit cards, the M1 money supply increases.

Why Is M1 Money Supply So High?

In May 2020, the Federal Reserve changed the official formula for calculating the M1 money supply. Prior to May 2020, M1 included currency in circulation, demand deposits at commercial banks, and other checkable deposits. After May 2020, the definition was expanded to include other liquid deposits, including savings accounts. This change was accompanied by a sharp spike in the reported value of the M1 money supply.

Why Is M2 More Stable Than M1?

The M2 money supply is more stable than the M1 money supply because the M1 money supply only contains the most liquid of assets. Whereas it may take a little longer for components of the M2 money supply to convert or be liquidated, the M1 money supply more often changes due to the ease of being able to transact.

Who Controls the M1 Money Supply?

The total supply of money is managed by the Federal Reserve banks. The Federal Reserve banks establish monetary and fiscal policies to influence the economy, create jobs, or combat inflation.

How Does the M1 Money Supply Affect Inflation?

As the Federal Reserve increases the money supply, money is easier to come by. Debt usually costs less, or tax breaks approved by the Federal government may reduce tax liabilities. As a result, consumers have more capital available to spend. An unfortunate downside of increasing the money supply is that the demand for goods broadly increases as consumers have greater purchasing power. As a result, prices for good broadly tend to increase. For example, when the cost of debt is low and the money supply increases, the cost of taking a home mortgage (i.e. mortgage rates) are low, thus applying upward pressure on housing prices.

The M1 money supply consists of the sum of currency, demand deposits, and other liquid deposits. Each component is often seasonally adjusted, and this measurement contains only the most liquid vehicles compared to other money supply measurements. The money supply often directly relates to inflation, and the Federal Reserve often manages the money supply via fiscal and monetary policy to influence the economy.

Correction — May 14, 2023: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the M0 money supply is equal to the amount of currency in circulation. In fact, M0 also includes the reserve balances held by banks at the Federal Reserve.

Federal Reserve. " Monetary Aggregates and Monetary Policy at the Federal Reserve: A Historical Perspective ."

Federal Reserve. " Discontinuance of M3 ."

Federal Reserve Economic Data. " M1 (Discontinued) ."

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " M1 ."

European Central Bank. " Monetary Aggregates ."

Reserve Bank of Australia. " Money in the Australian Economy ."

UK National Archives. " UK Monetary Aggregates: Main Definitional Changes ," Page 6.

Bank of England. " Further Details About M0 Data ."

Bank of England. " Further Details About M4 Data ."

MInternet Archive. " A Monetary History of the United States: 1867–1960 ," Pages 676–700.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1194842257-07d7308488234bfcbb4ce240136ca679.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 1. Planning and Writing an Annual Budget

Chapter 43 Sections

- Section 2. Managing Your Money

- Section 3. Handling Accounting

- Section 4. Understanding Nonprofit Status and Tax Exemption

- Section 5. Creating a Financial and Audit Committee

- Main Section

What are the elements of an annual budget?

Why should you prepare an annual budget, some practical considerations, planning and gathering information to create a budget, putting it all together: creating and working with a budget document.

Download the Program Based Budget Template mentioned in this video here .

It can be daunting to start the process of creating a budget, especially if you're not familiar with some of the common accounting and budget terminology you will encounter, so we have provided a glossary of terms covered here, located toward the bottom of the page under the In Summary section of the page.

It is important for organizations to create accurate and up-to-date annual budgets in order to maintain control over their finances, and to show funders exactly how their money is being used. How specific and complex the actual budget document needs to be depends on how large the budget is, how many funders you have and what their requirements are, how many different programs or activities you're using the money for, etc. At some level, however, your budget will need to include the following:

- Projected expenses . The amount of money you expect to spend in the coming fiscal year , broken down into the categories you expect to spend it in - salaries, office expenses, etc.

Fiscal year simply means "financial year ," and is the calendar you use to figure your yearly budget, and which determines when you file tax forms, get audited, and close your books. There are many different fiscal years you can use. Businesses often use the calendar year -- January 1 to December 31. The federal government's fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30. State governments -- and therefore state agencies and many community-based and non-profit organizations that receive state funding - usually use July 1 to June 30. Most organizations adopt a fiscal year that fits with that of their major funders. You'll want to prepare your budget specifically to cover your fiscal year, and to have it ready before the fiscal year begins. In many organizations, the Board of Directors needs to approve a budget before the beginning of the fiscal year in order for the organization to operate.

- Projected income . The amount of money you expect to take in for the coming fiscal year, broken down by sources -- i.e. the amount you expect from each funding source, including not only grants and contracts, but also your own fundraising efforts, memberships, and sales of goods or services.

- The interaction of expenses and income . What gets funded from which sources? In many cases, this is a condition of the funding: a funder agrees to provide money for a specific position, for instance, or for particular activities or items. If funding comes with restrictions, it's important to build those restrictions into your budget, so that you can make sure to spend the money as you've told the funder you would.

- Adjustments to reflect reality as the year goes on . Your budget will likely begin with estimates, and as the year progresses, those estimates need to be adjusted to be as accurate as possible to keep track of what's really happening.

- It sharpens your understanding of your goals

- It gives you the real picture - by accurately showing you what you can afford and where the gaps in funding are, your budget allows you to plan beforehand to meet needs, and to decide what you're actually able to do in a given year

- It encourages effective ways of dealing with money issues - by showing you what you can't afford with known income, a budget can motivate you to be creative - and successful - in seeking out other sources of funding

- It fills the need for required information - the completed budget is a necessary element of funding proposals and reports to funders and the community

- It facilitates discussion of the financial realities of the organization

- It helps you avoid surprises and maintain fiscal control

It's important to note that not everyone has the skills or desire to create and manage a budget single handed. Fortunately, there's help available, both within the organization (by hiring a bookkeeper, accountant, or CFO) and elsewhere. There are organizations like SCORE (Service Corps of Retired Executives) that exist to assist with things like budgeting. Local universities or government agencies may maintain offices that help small businesses and non-profits with financial planning. The possibility of an accounting or similar position shared with or loaned by another organization may also exist.

The preliminaries: What will you need to spend money on next fiscal year?

It is important to know what the priorities are and what makes the most sense for the organization at its particular stage of development. Actually figuring out what you should be spending your money on involves an organization-wide planning process .

Consider these questions:

- What are the activities or programs that will do the most to advance your cause and mission, and that you think you can carry out with the income and resources you know you have or can foresee?

- How many staff positions will it take to run those activities or programs well?

- How much, how (hourly wages, salary, consultant fees, benefits), and from what sources will those staff members be compensated?

- What else will be needed to run the organization and its activities -- space, supplies, equipment, phone and utilities, insurance, transportation, etc.?

Estimating expenses: What will it all cost?

Step 1: Develop ways of estimating your expenses

Estimate your expenses for the coming fiscal year. In some cases -- yearly rent, or salaries, for instance -- you'll probably have real figures for what these expenses will be. In other cases -- telephone and utilities, etc. -- you'll have to estimate of an average monthly cost.

Be sure to add in some money in a "miscellaneous" category, in order to be prepared for the unexpected. There are always expenses you don't anticipate, and it is part of conservative estimation to make allowances for them.

Conservative estimation : When preparing a budget, try to be as accurate as possible. Always use actual figures if you have them, and when you don't, estimate conservatively for both expenses and income. When you estimate expenses, guess high -- take your highest monthly phone bill and multiply by 12, for instance, rather than taking an average. By the same token, when you're estimating income, guess low -- the smallest number realistically possible. Estimating conservatively when you plan your budget will make it more likely that you stay within it over the course of the year.

Step 2: List the estimated yearly expense totals of the absolute necessities of the organization

For most organizations, they include, but aren't necessarily limited to:

- Salaries or wages for all employees, listed separately by position

- Fringe benefits for all employees, also broken out by position. Remember that even if you have no formal fringe benefits, you still have to pay part of the Social Security and Medicare taxes, as well as Workers' Compensation and Unemployment Insurance, for any regular employees (people who work a fixed schedule). These costs can be considerable, amounting to 12 to 15% added on to your total payroll.

- Rent and/or mortgage payments for the organization's space

- Utilities (heat, electricity, gas, water)

- Phone service

- Internet provider or server costs, depending on your organization's needs

- Insurance (liability, fire and theft, etc.)

Step 3: List the estimated expenses for things you'll need to actually conduct the activities of the organization

- Program and office supplies: pencils, paper, software, educational material, post-it-notes, etc.

- Program and office equipment. Wherever you classify computers and peripherals, copiers, faxes, etc., be sure to figure in the annual estimated costs of repairs or service contracts in addition to purchase or lease costs.

For budgeting purposes , it may be useful to separate program supplies and equipment from office supplies and equipment. In the case of state and federal funding, at least some office expenses are often considered "administrative", and funding for administrative expenses may be limited, sometimes to as little as 5% of your budget.

Step 4: List estimated expenses for anything else the organization is obligated to pay or can't do without

- Loan payments

- Consultant services - these may include an annual audit, accounting or bookkeeping services, payments to other organizations for specific services, etc.

Most non-profit organizations are required , either by funders or by the IRS, to undergo an audit every year. This means that a CPA (Certified Public Accountant) must check the organization's financial records to make sure they are accurate, and work with the organization to correct any errors or solve problems. If there is nothing illegal or seriously wrong, the CPA then prepares financial statements using the organization's books, and certifies that the organization follows acceptable accounting practices and that its financial records are in order. The larger an organization's budget, the more complicated an audit is likely to be, the more time it is likely to take, and the more it is likely to cost. An audit of a $100,000 budget might cost $2,000 to $4,000, for instance; that of a $1 million budget might cost $15,000.

- Printing and copying, if not done within the organization

- Transportation: travel expense for staff, participants, and/or volunteers; and vehicle upkeep and expenses for any organization-owned vehicles

- Postage and other mailing expenses

Now that you've gathered your necessary expenses, you can take a look at your wish list.

Step 5: List estimated expenses for things which you aren't sure you can afford, but would like to do

These might include staff positions, new programs (including staff, supplies, space), equipment, etc.

Step 6: Add up all the expense items you have listed

This total is what you would like to spend to run your organization. In other words, it's your projected expense for the coming fiscal year.

Estimating Income: Where are we going to get all that money?

Use last year's figures, if you have them, as a baseline and estimate conservatively, rather than being overly optimistic, and laying yourself open to disappointment and worse.

Step 1: List all actual figures or estimates for what you can expect from your known funding sources

This includes sources that have already promised you money for the coming year, or that have regularly funded you in the past. These may include federal, state or local government agencies; private and community foundations; United Way; religious organizations; corporations or other private entities.

Step 2: If your organization fundraising, estimate the amount you'll raise in the next fiscal year

Fundraising efforts might include community events (a raffle, a bowl-a-thon), more ambitious events (a benefit concert by a world-class performer), media advertising, or phone or mail solicitation.

Step 3: If you charge fees or sell services, estimate the amount you'll take in from these activities

This could be consulting services your organization offers, training materials that you created that can be sold to others interested in the same work, etc.

Step 4: If you solicit members who pay yearly dues or fees, estimate the amount that membership will yield

Step 5: If you sell items, estimate what these sales will bring in

This could include pins, T-shirts, books, blood pressure cuffs, etc.

Step 6: If you sublet or rent space to others, record the estimate of what this will bring in

Step 7: If you have any income from investments, estimate what you'll realize from these

This could include investments, endowment income, annuities, or interest income (e.g., from a certificate of deposit, or from a Money Market or checking account)

Step 8: List and estimate the amounts from any other sources that are expected to bring in some income in the coming fiscal year

Step 9: Add up all the income items you have listed

This total is the money you have to work with, your projected income for the next fiscal year.

Analyzing and adjusting the budget

Step 1: Lay out your figures in a useful format

If your budget is going to be useful, it has to be organized in such a way that it can tell you exactly how much you have available to spend in each expense category.

The easiest way to do this is by using a grid, usually called a spreadsheet. In its simplest terms, a spreadsheet will have a list of funding sources along its top edge and a list of expense categories running down its left-hand edge, so that each vertical column represents a funding source, and each horizontal row represents an expense category. Where each column and row meet (this meeting place is called a cell), there should be a number representing the amount of money from that particular funding source (the column) that goes to that particular expense category (the row). A simple spreadsheet for a small organization might look like this:

Spreadsheet: United Consolidated Metropolitan Health Agency (UCMHA)

A spreadsheet format allows you to assign restricted funds to the proper categories, so that you can see how much money is actually available to you for any given expense category. In the above example, if the Department of Public Health says that no more than $18,000 of its grant can be spent on salaries and fringe, for instance, then you know that you have to find the rest of the $49,200 total in those categories from other sources.

Step 2: Compare your total expenses to your total income

- If your projected expenses and income are approximately equal then your budget is balanced .

- If your projected expenses are significantly less than your projected income, you have a budget surplus . This circumstance leaves you with the possibility of expanding or improving the organization, or of putting money away for when you need it.

- If your projected expenses are significantly greater than your projected income, you have a budget deficit . In this case, you'll either have to find more money or cut expenses in order to run your organization in the coming year.

Step 3: (For balanced budgets) Make sure you are able to use your money as planned

If you've filled in the numbers in accordance with your funding restrictions, your spreadsheet should immediately let you know whether you have enough in each of your expense categories. If there is a problem, there are several ways of addressing it.

- It may be possible to come to an arrangement with the funder that allows you to use the money in the ways that you'd like to, or that allows you more freedom

- You may be able to reassign some expenses from one category to another. If you don't have enough money to pay an Assistant Director, for example, it may make sense to make her the coordinator of a particular program, and to pay part of her salary out of the funds allotted to that program.

- In some cases, it might be necessary to rethink your priorities a bit, so that the money can be spent in accordance with funding restrictions

It's important to remember, however, that the mission, philosophy, and goals of your organization should drive its funding, and not the other way around. Creating a program simply to make use of available funding is usually a bad idea, unless the program is one you've already planned for, and will clearly fit in with and advance the mission of your organization.

Step 4: (For budget surpluses) Be aware that it may not show up as cash until the end of the coming fiscal year

- The most conservative course is to try to stick to your budget, and invest the excess money at the end of the year. This will give you something to draw on in emergencies, or money you can use in the future for something that the organization really wants or needs to do.

- "Invest" here doesn't necessarily mean putting money in the stock market, which usually doesn't make sense unless you have a lot of money, and you're willing to stay with it for a long period of time - ten years or more. Certificates of Deposit, which give high interest rates in return for keeping money in the bank for a set period (generally, you can choose a period of from six months to five years), or Money Market accounts, which give a high interest rate in return for keeping a large balance, are easy ways for an organization to earn interest on its money, while still keeping it available for emergencies.

- You can use your surplus to improve working conditions within the organization: raise salaries, add a benefit package, etc. It is important to remember that once you've instituted this type of change, you're obligated to maintain it.

- You can buy items that you haven't been able to afford previously

- You can consider adding positions or starting a whole new program or initiative, perhaps one you've been planning for a long time. If you're starting a new program, you're also implicitly making a commitment to maintaining it for a period of years, so that it will have enough time to be successful.

- You can think about a long-term capital investment, like buying a building. You could lock in your rent for the duration of the mortgage (probably 20 years), and you might be able to provide the organization with income as well, by renting part of the building to other organizations.

- Your surplus may not be large enough to enable your organization to make significant changes on its own, but it may provide the means for you to enter into a collaboration with other organizations to achieve a goal that none could have accomplished alone.

Step 5: (For budget deficits) Consider combining several or all of the following possibilities to make your budget work

- If you have enough money in the bank or in investments from prior years, you can use it to make up the gap in your budget

- You can try to raise the additional money you need through grantwriting, fundraising efforts and events, increasing your fees for service, etc. If you have a plan for raising money - such as a raffle to finance a new copier - it should be listed with your estimated income. But be aware that such a projection isn't "real" money until the financial goal it represents is actually reached.

- You can explore saving some money by collaborating with another organization to share the costs of services, personnel, or materials and equipment

- You can try to cut expenses by reducing some of your costs: use less electricity, use recycled paper, try to get donations of some items you planned to buy, etc.

- You can cut expenses by eliminating some things from your budget

A Guide for Budget Cutting If you're going to cut your budget, it's a good idea to have a rational system for doing so. Here is a suggested step-by-step process which allows you to look at what is more and less necessary, and to make considered decisions about what you can do without and what you can't. Look first at those items that aren't essential to the running of the organization. Can you cut or cut down the amount of physical, tangible items you need to run the program, or cut the cost of services in some way? Finally, if nothing else will serve to balance the budget, you may have to consider cutting back on whatever it is the organization does, which usually translates to dealing with the positions of paid staff. Reduce the hours of one or more staff, if people are on hourly wages - for instance, consider reducing the work week from 40 to 37.5 hours, or even further Reduce one or more positions from full to half time - keep in mind that in many organizations, this reduction would eliminate benefits for those affected Ask staff to pay a larger share of their fringe benefits (if there are fringe benefits) Lay off one or more staff members

You can borrow the money you need, being sure to add the loan payments to your projected expenses and figure them into your revised budget

Creating an actual budget document

While the spreadsheet is probably what you'll use to keep track of your finances, you might also want to put the budget in a form everyone in the organization can understand.

Probably the simplest budget document is one which lists projected expenses by category and projected income by source, with totals for each. Thus, anyone can see how much you intend to spend, how much you intend to take in, and what the difference is, if any. Referring back to the spreadsheet example above, a simple budget would look like this:

UCMHA Annual Budget for Fiscal 2001 (July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2001)

Another possible form would be similar, but would include a budget narrative, explaining how various items were arrived at.

The salary item, for instance, might look like this:

Other categories would be handled in the same way, with explanations of what they included and how the money would be spent.

A final possibility would be to use the spreadsheet itself as a budget document, for those who wanted to see exactly how the money was to be allocated. Many organizations provide their Boards with both a simple budget and a spreadsheet, so that those Board members who are eager to understand the organization's finances can get a clear picture, while others can simply see whether the budget is in balance.

Working with your budget