Scientometric overview of nursing research on pain management

Affiliations.

- 1 MSc, Researcher, Dokuz Eylul University, Faculty of Nursing, İzmir, Turkey.

- 2 PhD, Professor, Dokuz Eylul University, Faculty of Nursing, İzmir, Turkey.

- 3 PhD, Associate Professor, Dokuz Eylul University, Faculty of Business, Izmir, Turkey.

- 4 MSc, Researcher, Dokuz Eylul University, Faculty of Business, Izmir, Turkey.

- PMID: 30183876

- PMCID: PMC6136548

- DOI: 10.1590/1518-8345.2581.3051

Objective: to analyse research articles on pain and nursing issues using bibliometric and scientometric methodologies.

Method: articles in the Web of Science database containing pain and nurse and pain and nursing were analyzed using scientometric methods through data visualization techniques and advanced text analytics.

Result: among the 107,559 research articles found in the field of nursing, 3,976 of them were written based on the keywords pain and nursing, and were considered in conformity with the scope of this study. Preliminary analyses indicated that the publications have increased through the years with minor fluctuations. Titles, keywords, and abstracts were analyzed through text analytics to reveal keyword clusters and topic structures. Studies on oncology and pain in the field of nursing have a relatively higher frequency.

Conclusion: the results of the analyses revealed the characteristics of the current literature in a broad range of areas by considering the particular dimensions. Therefore, the findings may support present and future research in this field by shedding light on the networks, trends, and contents in the related literature.

- Bibliometrics

- Nursing Research*

- Pain Management*

- Publishing / statistics & numerical data

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

Deciphering the influence: academic stress and its role in shaping learning approaches among nursing students: a cross-sectional study

- Rawhia Salah Dogham 1 ,

- Heba Fakieh Mansy Ali 1 ,

- Asmaa Saber Ghaly 3 ,

- Nermine M. Elcokany 2 ,

- Mohamed Mahmoud Seweid 4 &

- Ayman Mohamed El-Ashry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7718-4942 5

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 249 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

316 Accesses

Metrics details

Nursing education presents unique challenges, including high levels of academic stress and varied learning approaches among students. Understanding the relationship between academic stress and learning approaches is crucial for enhancing nursing education effectiveness and student well-being.

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of academic stress and its correlation with learning approaches among nursing students.

Design and Method

A cross-sectional descriptive correlation research design was employed. A convenient sample of 1010 nursing students participated, completing socio-demographic data, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and the Revised Study Process Questionnaire (R-SPQ-2 F).

Most nursing students experienced moderate academic stress (56.3%) and exhibited moderate levels of deep learning approaches (55.0%). Stress from a lack of professional knowledge and skills negatively correlates with deep learning approaches (r = -0.392) and positively correlates with surface learning approaches (r = 0.365). Female students showed higher deep learning approach scores, while male students exhibited higher surface learning approach scores. Age, gender, educational level, and academic stress significantly influenced learning approaches.

Academic stress significantly impacts learning approaches among nursing students. Strategies addressing stressors and promoting healthy learning approaches are essential for enhancing nursing education and student well-being.

Nursing implication

Understanding academic stress’s impact on nursing students’ learning approaches enables tailored interventions. Recognizing stressors informs strategies for promoting adaptive coping, fostering deep learning, and creating supportive environments. Integrating stress management, mentorship, and counseling enhances student well-being and nursing education quality.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Nursing education is a demanding field that requires students to acquire extensive knowledge and skills to provide competent and compassionate care. Nursing education curriculum involves high-stress environments that can significantly impact students’ learning approaches and academic performance [ 1 , 2 ]. Numerous studies have investigated learning approaches in nursing education, highlighting the importance of identifying individual students’ preferred approaches. The most studied learning approaches include deep, surface, and strategic approaches. Deep learning approaches involve students actively seeking meaning, making connections, and critically analyzing information. Surface learning approaches focus on memorization and reproducing information without a more profound understanding. Strategic learning approaches aim to achieve high grades by adopting specific strategies, such as memorization techniques or time management skills [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Nursing education stands out due to its focus on practical training, where the blend of academic and clinical coursework becomes a significant stressor for students, despite academic stress being shared among all university students [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Consequently, nursing students are recognized as prone to high-stress levels. Stress is the physiological and psychological response that occurs when a biological control system identifies a deviation between the desired (target) state and the actual state of a fitness-critical variable, whether that discrepancy arises internally or externally to the human [ 9 ]. Stress levels can vary from objective threats to subjective appraisals, making it a highly personalized response to circumstances. Failure to manage these demands leads to stress imbalance [ 10 ].

Nursing students face three primary stressors during their education: academic, clinical, and personal/social stress. Academic stress is caused by the fear of failure in exams, assessments, and training, as well as workload concerns [ 11 ]. Clinical stress, on the other hand, arises from work-related difficulties such as coping with death, fear of failure, and interpersonal dynamics within the organization. Personal and social stressors are caused by an imbalance between home and school, financial hardships, and other factors. Throughout their education, nursing students have to deal with heavy workloads, time constraints, clinical placements, and high academic expectations. Multiple studies have shown that nursing students experience higher stress levels compared to students in other fields [ 12 , 13 , 14 ].

Research has examined the relationship between academic stress and coping strategies among nursing students, but no studies focus specifically on the learning approach and academic stress. However, existing literature suggests that students interested in nursing tend to experience lower levels of academic stress [ 7 ]. Therefore, interest in nursing can lead to deep learning approaches, which promote a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter, allowing students to feel more confident and less overwhelmed by coursework and exams. Conversely, students employing surface learning approaches may experience higher stress levels due to the reliance on memorization [ 3 ].

Understanding the interplay between academic stress and learning approaches among nursing students is essential for designing effective educational interventions. Nursing educators can foster deep learning approaches by incorporating active learning strategies, critical thinking exercises, and reflection activities into the curriculum [ 15 ]. Creating supportive learning environments encouraging collaboration, self-care, and stress management techniques can help alleviate academic stress. Additionally, providing mentorship and counselling services tailored to nursing students’ unique challenges can contribute to their overall well-being and academic success [ 16 , 17 , 18 ].

Despite the scarcity of research focusing on the link between academic stress and learning methods in nursing students, it’s crucial to identify the unique stressors they encounter. The intensity of these stressors can be connected to the learning strategies employed by these students. Academic stress and learning approach are intertwined aspects of the student experience. While academic stress can influence learning approaches, the choice of learning approach can also impact the level of academic stress experienced. By understanding this relationship and implementing strategies to promote healthy learning approaches and manage academic stress, educators and institutions can foster an environment conducive to deep learning and student well-being.

Hence, this study aims to investigate the correlation between academic stress and learning approaches experienced by nursing students.

Study objectives

Assess the levels of academic stress among nursing students.

Assess the learning approaches among nursing students.

Identify the relationship between academic stress and learning approach among nursing students.

Identify the effect of academic stress and related factors on learning approach and among nursing students.

Materials and methods

Research design.

A cross-sectional descriptive correlation research design adhering to the STROBE guidelines was used for this study.

A research project was conducted at Alexandria Nursing College, situated in Egypt. The college adheres to the national standards for nursing education and functions under the jurisdiction of the Egyptian Ministry of Higher Education. Alexandria Nursing College comprises nine specialized nursing departments that offer various nursing specializations. These departments include Nursing Administration, Community Health Nursing, Gerontological Nursing, Medical-Surgical Nursing, Critical Care Nursing, Pediatric Nursing, Obstetric and Gynecological Nursing, Nursing Education, and Psychiatric Nursing and Mental Health. The credit hour system is the fundamental basis of both undergraduate and graduate programs. This framework guarantees a thorough evaluation of academic outcomes by providing an organized structure for tracking academic progress and conducting analyses.

Participants and sample size calculation

The researchers used the Epi Info 7 program to calculate the sample size. The calculations were based on specific parameters such as a population size of 9886 students for the academic year 2022–2023, an expected frequency of 50%, a maximum margin of error of 5%, and a confidence coefficient of 99.9%. Based on these parameters, the program indicated that a minimum sample size of 976 students was required. As a result, the researchers recruited a convenient sample of 1010 nursing students from different academic levels during the 2022–2023 academic year [ 19 ]. This sample size was larger than the minimum required, which could help to increase the accuracy and reliability of the study results. Participation in the study required enrollment in a nursing program and voluntary agreement to take part. The exclusion criteria included individuals with mental illnesses based on their response and those who failed to complete the questionnaires.

socio-demographic data that include students’ age, sex, educational level, hours of sleep at night, hours spent studying, and GPA from the previous semester.

Tool two: the perceived stress scale (PSS)

It was initially created by Sheu et al. (1997) to gauge the level and nature of stress perceived by nursing students attending Taiwanese universities [ 20 ]. It comprises 29 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = reasonably often, and 4 = very often), with a total score ranging from 0 to 116. The cut-off points of levels of perceived stress scale according to score percentage were low < 33.33%, moderate 33.33–66.66%, and high more than 66.66%. Higher scores indicate higher stress levels. The items are categorized into six subscales reflecting different sources of stress. The first subscale assesses “stress stemming from lack of professional knowledge and skills” and includes 3 items. The second subscale evaluates “stress from caring for patients” with 8 items. The third subscale measures “stress from assignments and workload” with 5 items. The fourth subscale focuses on “stress from interactions with teachers and nursing staff” with 6 items. The fifth subscale gauges “stress from the clinical environment” with 3 items. The sixth subscale addresses “stress from peers and daily life” with 4 items. El-Ashry et al. (2022) reported an excellent internal consistency reliability of 0.83 [ 21 ]. Two bilingual translators translated the English version of the scale into Arabic and then back-translated it into English by two other independent translators to verify its accuracy. The suitability of the translated version was confirmed through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which yielded goodness-of-fit indices such as a comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.712, a Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) of 0.812, and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.100.

Tool three: revised study process questionnaire (R-SPQ-2 F)

It was developed by Biggs et al. (2001). It examines deep and surface learning approaches using only 20 questions; each subscale contains 10 questions [ 22 ]. On a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never or only rarely true of me) to 4 (always or almost always accurate of me). The total score ranged from 0 to 80, with a higher score reflecting more deep or surface learning approaches. The cut-off points of levels of revised study process questionnaire according to score percentage were low < 33%, moderate 33–66%, and high more than 66%. Biggs et al. (2001) found that Cronbach alpha value was 0.73 for deep learning approach and 0.64 for the surface learning approach, which was considered acceptable. Two translators fluent in English and Arabic initially translated a scale from English to Arabic. To ensure the accuracy of the translation, they translated it back into English. The translated version’s appropriateness was evaluated using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The CFA produced several goodness-of-fit indices, including a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.790, a Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of 0.912, and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.100. Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.790, a Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of 0.912, and a Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.100.

Ethical considerations

The Alexandria University College of Nursing’s Research Ethics Committee provided ethical permission before the study’s implementation. Furthermore, pertinent authorities acquired ethical approval at participating nursing institutions. The vice deans of the participating institutions provided written informed consent attesting to institutional support and authority. By giving written informed consent, participants confirmed they were taking part voluntarily. Strict protocols were followed to protect participants’ privacy during the whole investigation. The obtained personal data was kept private and available only to the study team. Ensuring participants’ privacy and anonymity was of utmost importance.

Tools validity

The researchers created tool one after reviewing pertinent literature. Two bilingual translators independently translated the English version into Arabic to evaluate the applicability of the academic stress and learning approach tools for Arabic-speaking populations. To assure accuracy, two additional impartial translators back-translated the translation into English. They were also assessed by a five-person jury of professionals from the education and psychiatric nursing departments. The scales were found to have sufficiently evaluated the intended structures by the jury.

Pilot study

A preliminary investigation involved 100 nursing student applicants, distinct from the final sample, to gauge the efficacy, clarity, and potential obstacles in utilizing the research instruments. The pilot findings indicated that the instruments were accurate, comprehensible, and suitable for the target demographic. Additionally, Cronbach’s Alpha was utilized to further assess the instruments’ reliability, demonstrating internal solid consistency for both the learning approaches and academic stress tools, with values of 0.91 and 0.85, respectively.

Data collection

The researchers convened with each qualified student in a relaxed, unoccupied classroom in their respective college settings. Following a briefing on the study’s objectives, the students filled out the datasheet. The interviews typically lasted 15 to 20 min.

Data analysis

The data collected were analyzed using IBM SPSS software version 26.0. Following data entry, a thorough examination and verification were undertaken to ensure accuracy. The normality of quantitative data distributions was assessed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Cronbach’s Alpha was employed to evaluate the reliability and internal consistency of the study instruments. Descriptive statistics, including means (M), standard deviations (SD), and frequencies/percentages, were computed to summarize academic stress and learning approaches for categorical data. Student’s t-tests compared scores between two groups for normally distributed variables, while One-way ANOVA compared scores across more than two categories of a categorical variable. Pearson’s correlation coefficient determined the strength and direction of associations between customarily distributed quantitative variables. Hierarchical regression analysis identified the primary independent factors influencing learning approaches. Statistical significance was determined at the 5% (p < 0.05).

Table 1 presents socio-demographic data for a group of 1010 nursing students. The age distribution shows that 38.8% of the students were between 18 and 21 years old, 32.9% were between 21 and 24 years old, and 28.3% were between 24 and 28 years old, with an average age of approximately 22.79. Regarding gender, most of the students were female (77%), while 23% were male. The students were distributed across different educational years, a majority of 34.4% in the second year, followed by 29.4% in the fourth year. The students’ hours spent studying were found to be approximately two-thirds (67%) of the students who studied between 3 and 6 h. Similarly, sleep patterns differ among the students; more than three-quarters (77.3%) of students sleep between 5- to more than 7 h, and only 2.4% sleep less than 2 h per night. Finally, the student’s Grade Point Average (GPA) from the previous semester was also provided. 21% of the students had a GPA between 2 and 2.5, 40.9% had a GPA between 2.5 and 3, and 38.1% had a GPA between 3 and 3.5.

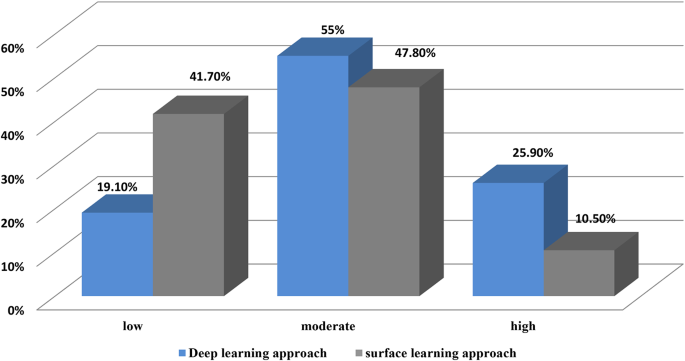

Figure 1 provides the learning approach level among nursing students. In terms of learning approach, most students (55.0%) exhibited a moderate level of deep learning approach, followed by 25.9% with a high level and 19.1% with a low level. The surface learning approach was more prevalent, with 47.8% of students showing a moderate level, 41.7% showing a low level, and only 10.5% exhibiting a high level.

Nursing students? levels of learning approach (N=1010)

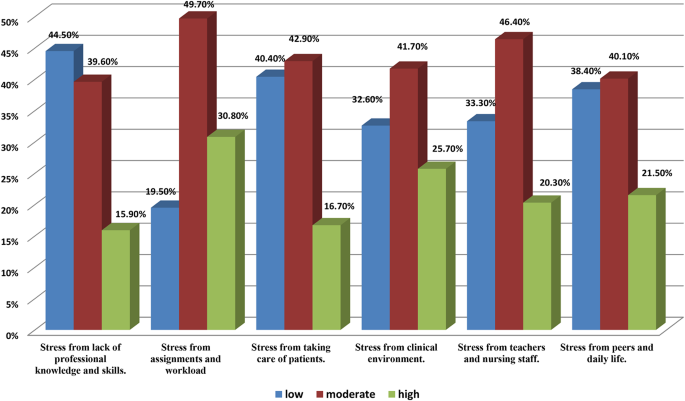

Figure 2 provides the types of academic stress levels among nursing students. Among nursing students, various stressors significantly impact their academic experiences. Foremost among these stressors are the pressure and demands associated with academic assignments and workload, with 30.8% of students attributing their high stress levels to these factors. Challenges within the clinical environment are closely behind, contributing significantly to high stress levels among 25.7% of nursing students. Interactions with peers and daily life stressors also weigh heavily on students, ranking third among sources of high stress, with 21.5% of students citing this as a significant factor. Similarly, interaction with teachers and nursing staff closely follow, contributing to high-stress levels for 20.3% of nursing students. While still significant, stress from taking care of patients ranks slightly lower, with 16.7% of students reporting it as a significant factor contributing to their academic stress. At the lowest end of the ranking, but still notable, is stress from a perceived lack of professional knowledge and skills, with 15.9% of students experiencing high stress in this area.

Nursing students? levels of academic stress subtypes (N=1010)

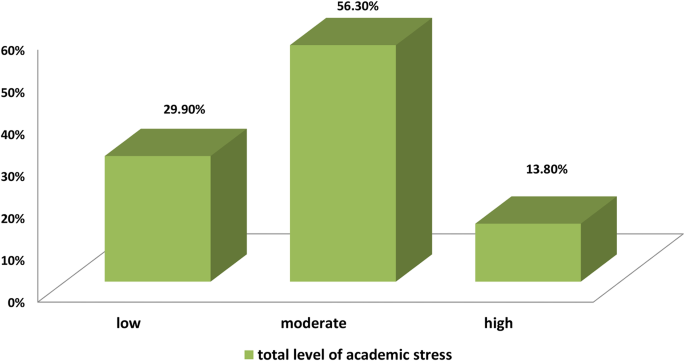

Figure 3 provides the total levels of academic stress among nursing students. The majority of students experienced moderate academic stress (56.3%), followed by those experiencing low academic stress (29.9%), and a minority experienced high academic stress (13.8%).

Nursing students? levels of total academic stress (N=1010)

Table 2 displays the correlation between academic stress subscales and deep and surface learning approaches among 1010 nursing students. All stress subscales exhibited a negative correlation regarding the deep learning approach, indicating that the inclination toward deep learning decreases with increasing stress levels. The most significant negative correlation was observed with stress stemming from the lack of professional knowledge and skills (r=-0.392, p < 0.001), followed by stress from the clinical environment (r=-0.109, p = 0.001), stress from assignments and workload (r=-0.103, p = 0.001), stress from peers and daily life (r=-0.095, p = 0.002), and stress from patient care responsibilities (r=-0.093, p = 0.003). The weakest negative correlation was found with stress from interactions with teachers and nursing staff (r=-0.083, p = 0.009). Conversely, concerning the surface learning approach, all stress subscales displayed a positive correlation, indicating that heightened stress levels corresponded with an increased tendency toward superficial learning. The most substantial positive correlation was observed with stress related to the lack of professional knowledge and skills (r = 0.365, p < 0.001), followed by stress from patient care responsibilities (r = 0.334, p < 0.001), overall stress (r = 0.355, p < 0.001), stress from interactions with teachers and nursing staff (r = 0.262, p < 0.001), stress from assignments and workload (r = 0.262, p < 0.001), and stress from the clinical environment (r = 0.254, p < 0.001). The weakest positive correlation was noted with stress stemming from peers and daily life (r = 0.186, p < 0.001).

Table 3 outlines the association between the socio-demographic characteristics of nursing students and their deep and surface learning approaches. Concerning age, statistically significant differences were observed in deep and surface learning approaches (F = 3.661, p = 0.003 and F = 7.983, p < 0.001, respectively). Gender also demonstrated significant differences in deep and surface learning approaches (t = 3.290, p = 0.001 and t = 8.638, p < 0.001, respectively). Female students exhibited higher scores in the deep learning approach (31.59 ± 8.28) compared to male students (29.59 ± 7.73), while male students had higher scores in the surface learning approach (29.97 ± 7.36) compared to female students (24.90 ± 7.97). Educational level exhibited statistically significant differences in deep and surface learning approaches (F = 5.599, p = 0.001 and F = 17.284, p < 0.001, respectively). Both deep and surface learning approach scores increased with higher educational levels. The duration of study hours demonstrated significant differences only in the surface learning approach (F = 3.550, p = 0.014), with scores increasing as study hours increased. However, no significant difference was observed in the deep learning approach (F = 0.861, p = 0.461). Hours of sleep per night and GPA from the previous semester did not exhibit statistically significant differences in deep or surface learning approaches.

Table 4 presents a multivariate linear regression analysis examining the factors influencing the learning approach among 1110 nursing students. The deep learning approach was positively influenced by age, gender (being female), educational year level, and stress from teachers and nursing staff, as indicated by their positive coefficients and significant p-values (p < 0.05). However, it was negatively influenced by stress from a lack of professional knowledge and skills. The other factors do not significantly influence the deep learning approach. On the other hand, the surface learning approach was positively influenced by gender (being female), educational year level, stress from lack of professional knowledge and skills, stress from assignments and workload, and stress from taking care of patients, as indicated by their positive coefficients and significant p-values (p < 0.05). However, it was negatively influenced by gender (being male). The other factors do not significantly influence the surface learning approach. The adjusted R-squared values indicated that the variables in the model explain 17.8% of the variance in the deep learning approach and 25.5% in the surface learning approach. Both models were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Nursing students’ academic stress and learning approaches are essential to planning for effective and efficient learning. Nursing education also aims to develop knowledgeable and competent students with problem-solving and critical-thinking skills.

The study’s findings highlight the significant presence of stress among nursing students, with a majority experiencing moderate to severe levels of academic stress. This aligns with previous research indicating that academic stress is prevalent among nursing students. For instance, Zheng et al. (2022) observed moderated stress levels in nursing students during clinical placements [ 23 ], while El-Ashry et al. (2022) found that nearly all first-year nursing students in Egypt experienced severe academic stress [ 21 ]. Conversely, Ali and El-Sherbini (2018) reported that over three-quarters of nursing students faced high academic stress. The complexity of the nursing program likely contributes to these stress levels [ 24 ].

The current study revealed that nursing students identified the highest sources of academic stress as workload from assignments and the stress of caring for patients. This aligns with Banu et al.‘s (2015) findings, where academic demands, assignments, examinations, high workload, and combining clinical work with patient interaction were cited as everyday stressors [ 25 ]. Additionally, Anaman-Torgbor et al. (2021) identified lectures, assignments, and examinations as predictors of academic stress through logistic regression analysis. These stressors may stem from nursing programs emphasizing the development of highly qualified graduates who acquire knowledge, values, and skills through classroom and clinical experiences [ 26 ].

The results regarding learning approaches indicate that most nursing students predominantly employed the deep learning approach. Despite acknowledging a surface learning approach among the participants in the present study, the prevalence of deep learning was higher. This inclination toward the deep learning approach is anticipated in nursing students due to their engagement with advanced courses, requiring retention, integration, and transfer of information at elevated levels. The deep learning approach correlates with a gratifying learning experience and contributes to higher academic achievements [ 3 ]. Moreover, the nursing program’s emphasis on active learning strategies fosters critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making skills. These findings align with Mahmoud et al.‘s (2019) study, reporting a significant presence (83.31%) of the deep learning approach among undergraduate nursing students at King Khalid University’s Faculty of Nursing [ 27 ]. Additionally, Mohamed &Morsi (2019) found that most nursing students at Benha University’s Faculty of Nursing embraced the deep learning approach (65.4%) compared to the surface learning approach [ 28 ].

The study observed a negative correlation between the deep learning approach and the overall mean stress score, contrasting with a positive correlation between surface learning approaches and overall stress levels. Elevated academic stress levels may diminish motivation and engagement in the learning process, potentially leading students to feel overwhelmed, disinterested, or burned out, prompting a shift toward a surface learning approach. This finding resonates with previous research indicating that nursing students who actively seek positive academic support strategies during academic stress have better prospects for success than those who do not [ 29 ]. Nebhinani et al. (2020) identified interface concerns and academic workload as significant stress-related factors. Notably, only an interest in nursing demonstrated a significant association with stress levels, with participants interested in nursing primarily employing adaptive coping strategies compared to non-interested students.

The current research reveals a statistically significant inverse relationship between different dimensions of academic stress and adopting the deep learning approach. The most substantial negative correlation was observed with stress arising from a lack of professional knowledge and skills, succeeded by stress associated with the clinical environment, assignments, and workload. Nursing students encounter diverse stressors, including delivering patient care, handling assignments and workloads, navigating challenging interactions with staff and faculty, perceived inadequacies in clinical proficiency, and facing examinations [ 30 ].

In the current study, the multivariate linear regression analysis reveals that various factors positively influence the deep learning approach, including age, female gender, educational year level, and stress from teachers and nursing staff. In contrast, stress from a lack of professional knowledge and skills exert a negative influence. Conversely, the surface learning approach is positively influenced by female gender, educational year level, stress from lack of professional knowledge and skills, stress from assignments and workload, and stress from taking care of patients, but negatively affected by male gender. The models explain 17.8% and 25.5% of the variance in the deep and surface learning approaches, respectively, and both are statistically significant. These findings underscore the intricate interplay of demographic and stress-related factors in shaping nursing students’ learning approaches. High workloads and patient care responsibilities may compel students to prioritize completing tasks over deep comprehension. This pressure could lead to a surface learning approach as students focus on meeting immediate demands rather than engaging deeply with course material. This observation aligns with the findings of Alsayed et al. (2021), who identified age, gender, and study year as significant factors influencing students’ learning approaches.

Deep learners often demonstrate better self-regulation skills, such as effective time management, goal setting, and seeking support when needed. These skills can help manage academic stress and maintain a balanced learning approach. These are supported by studies that studied the effect of coping strategies on stress levels [ 6 , 31 , 32 ]. On the contrary, Pacheco-Castillo et al. study (2021) found a strong significant relationship between academic stressors and students’ level of performance. That study also proved that the more academic stress a student faces, the lower their academic achievement.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has lots of advantages. It provides insightful information about the educational experiences of Egyptian nursing students, a demographic that has yet to receive much research. The study’s limited generalizability to other people or nations stems from its concentration on this particular group. This might be addressed in future studies by using a more varied sample. Another drawback is the dependence on self-reported metrics, which may contain biases and mistakes. Although the cross-sectional design offers a moment-in-time view of the problem, it cannot determine causation or evaluate changes over time. To address this, longitudinal research may be carried out.

Notwithstanding these drawbacks, the study substantially contributes to the expanding knowledge of academic stress and nursing students’ learning styles. Additional research is needed to determine teaching strategies that improve deep-learning approaches among nursing students. A qualitative study is required to analyze learning approaches and factors that may influence nursing students’ selection of learning approaches.

According to the present study’s findings, nursing students encounter considerable academic stress, primarily stemming from heavy assignments and workload, as well as interactions with teachers and nursing staff. Additionally, it was observed that students who experience lower levels of academic stress typically adopt a deep learning approach, whereas those facing higher stress levels tend to resort to a surface learning approach. Demographic factors such as age, gender, and educational level influence nursing students’ choice of learning approach. Specifically, female students are more inclined towards deep learning, whereas male students prefer surface learning. Moreover, deep and surface learning approach scores show an upward trend with increasing educational levels and study hours. Academic stress emerges as a significant determinant shaping the adoption of learning approaches among nursing students.

Implications in nursing practice

Nursing programs should consider integrating stress management techniques into their curriculum. Providing students with resources and skills to cope with academic stress can improve their well-being and academic performance. Educators can incorporate teaching strategies that promote deep learning approaches, such as problem-based learning, critical thinking exercises, and active learning methods. These approaches help students engage more deeply with course material and reduce reliance on surface learning techniques. Recognizing the gender differences in learning approaches, nursing programs can offer gender-specific support services and resources. For example, providing targeted workshops or counseling services that address male and female nursing students’ unique stressors and learning needs. Implementing mentorship programs and peer support groups can create a supportive environment where students can share experiences, seek advice, and receive encouragement from their peers and faculty members. Encouraging students to reflect on their learning processes and identify effective study strategies can help them develop metacognitive skills and become more self-directed learners. Faculty members can facilitate this process by incorporating reflective exercises into the curriculum. Nursing faculty and staff should receive training on recognizing signs of academic stress among students and providing appropriate support and resources. Additionally, professional development opportunities can help educators stay updated on evidence-based teaching strategies and practical interventions for addressing student stress.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the institutional review board to protect participant confidentiality, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Liu J, Yang Y, Chen J, Zhang Y, Zeng Y, Li J. Stress and coping styles among nursing students during the initial period of the clinical practicum: A cross-section study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2022a;9(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2022.02.004 .

Saifan A, Devadas B, Daradkeh F, Abdel-Fattah H, Aljabery M, Michael LM. Solutions to bridge the theory-practice gap in nursing education in the UAE: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02919-x .

Alsayed S, Alshammari F, Pasay-an E, Dator WL. Investigating the learning approaches of students in nursing education. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2021;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtumed.2020.10.008 .

Salah Dogham R, Elcokany NM, Saber Ghaly A, Dawood TMA, Aldakheel FM, Llaguno MBB, Mohsen DM. Self-directed learning readiness and online learning self-efficacy among undergraduate nursing students. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2022;17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100490 .

Zhao Y, Kuan HK, Chung JOK, Chan CKY, Li WHC. Students’ approaches to learning in a clinical practicum: a psychometric evaluation based on item response theory. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.04.015 .

Huang HM, Fang YW. Stress and coping strategies of online nursing practicum courses for Taiwanese nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Healthcare. 2023;11(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11142053 .

Nebhinani M, Kumar A, Parihar A, Rani R. Stress and coping strategies among undergraduate nursing students: a descriptive assessment from Western Rajasthan. Indian J Community Med. 2020;45(2). https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_231_19 .

Olvera Alvarez HA, Provencio-Vasquez E, Slavich GM, Laurent JGC, Browning M, McKee-Lopez G, Robbins L, Spengler JD. Stress and health in nursing students: the Nurse Engagement and Wellness Study. Nurs Res. 2019;68(6). https://doi.org/10.1097/NNR.0000000000000383 .

Del Giudice M, Buck CL, Chaby LE, Gormally BM, Taff CC, Thawley CJ, Vitousek MN, Wada H. What is stress? A systems perspective. Integr Comp Biol. 2018;58(6):1019–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icy114 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bhui K, Dinos S, Galant-Miecznikowska M, de Jongh B, Stansfeld S. Perceptions of work stress causes and effective interventions in employees working in public, private and non-governmental organisations: a qualitative study. BJPsych Bull. 2016;40(6). https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.115.050823 .

Lavoie-Tremblay M, Sanzone L, Aubé T, Paquet M. Sources of stress and coping strategies among undergraduate nursing students across all years. Can J Nurs Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/08445621211028076 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ahmed WAM, Abdulla YHA, Alkhadher MA, Alshameri FA. Perceived stress and coping strategies among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Saudi J Health Syst Res. 2022;2(3). https://doi.org/10.1159/000526061 .

Pacheco-Castillo J, Casuso-Holgado MJ, Labajos-Manzanares MT, Moreno-Morales N. Academic stress among nursing students in a Private University at Puerto Rico, and its Association with their academic performance. Open J Nurs. 2021;11(09). https://doi.org/10.4236/ojn.2021.119063 .

Tran TTT, Nguyen NB, Luong MA, Bui THA, Phan TD, Tran VO, Ngo TH, Minas H, Nguyen TQ. Stress, anxiety and depression in clinical nurses in Vietnam: a cross-sectional survey and cluster analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0257-4 .

Magnavita N, Chiorri C. Academic stress and active learning of nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.06.003 .

Folkvord SE, Risa CF. Factors that enhance midwifery students’ learning and development of self-efficacy in clinical placement: a systematic qualitative review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103510 .

Myers SB, Sweeney AC, Popick V, Wesley K, Bordfeld A, Fingerhut R. Self-care practices and perceived stress levels among psychology graduate students. Train Educ Prof Psychol. 2012;6(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026534 .

Zeb H, Arif I, Younas A. Nurse educators’ experiences of fostering undergraduate students’ ability to manage stress and demanding situations: a phenomenological inquiry. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103501 .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. User Guide| Support| Epi Info™ [Internet]. Atlanta: CDC; [cited 2024 Jan 31]. Available from: CDC website.

Sheu S, Lin HS, Hwang SL, Yu PJ, Hu WY, Lou MF. The development and testing of a perceived stress scale for nursing students in clinical practice. J Nurs Res. 1997;5:41–52. Available from: http://ntur.lib.ntu.edu.tw/handle/246246/165917 .

El-Ashry AM, Harby SS, Ali AAG. Clinical stressors as perceived by first-year nursing students of their experience at Alexandria main university hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2022;41:214–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2022.08.007 .

Biggs J, Kember D, Leung DYP. The revised two-factor study process questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br J Educ Psychol. 2001;71(1):133–49. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158433 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Zheng YX, Jiao JR, Hao WN. Stress levels of nursing students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med (United States). 2022;101(36). https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000030547 .

Ali AM, El-Sherbini HH. Academic stress and its contributing factors among faculty nursing students in Alexandria. Alexandria Scientific Nursing Journal. 2018; 20(1):163–181. Available from: https://asalexu.journals.ekb.eg/article_207756_b62caf4d7e1e7a3b292bbb3c6632a0ab.pdf .

Banu P, Deb S, Vardhan V, Rao T. Perceived academic stress of university students across gender, academic streams, semesters, and academic performance. Indian J Health Wellbeing. 2015;6(3):231–235. Available from: http://www.iahrw.com/index.php/home/journal_detail/19#list .

Anaman-Torgbor JA, Tarkang E, Adedia D, Attah OM, Evans A, Sabina N. Academic-related stress among Ghanaian nursing students. Florence Nightingale J Nurs. 2021;29(3):263. https://doi.org/10.5152/FNJN.2021.21030 .

Mahmoud HG, Ahmed KE, Ibrahim EA. Learning Styles and Learning Approaches of Bachelor Nursing Students and its Relation to Their Achievement. Int J Nurs Didact. 2019;9(03):11–20. Available from: http://www.nursingdidactics.com/index.php/ijnd/article/view/2465 .

Mohamed NAAA, Morsi MES, Learning Styles L, Approaches. Academic achievement factors, and self efficacy among nursing students. Int J Novel Res Healthc Nurs. 2019;6(1):818–30. Available from: www.noveltyjournals.com.

Google Scholar

Onieva-Zafra MD, Fernández-Muñoz JJ, Fernández-Martínez E, García-Sánchez FJ, Abreu-Sánchez A, Parra-Fernández ML. Anxiety, perceived stress and coping strategies in nursing students: a cross-sectional, correlational, descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02294-z .

Article Google Scholar

Aljohani W, Banakhar M, Sharif L, Alsaggaf F, Felemban O, Wright R. Sources of stress among Saudi Arabian nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211958 .

Liu Y, Wang L, Shao H, Han P, Jiang J, Duan X. Nursing students’ experience during their practicum in an intensive care unit: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Front Public Health. 2022;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.974244 .

Majrashi A, Khalil A, Nagshabandi E, Al MA. Stressors and coping strategies among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: scoping review. Nurs Rep. 2021;11(2):444–59. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11020042 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks go to all the nursing students in the study. We also want to thank Dr/ Rasha Badry for their statistical analysis help and contribution to this study.

The research was not funded by public, commercial, or non-profit organizations.

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Nursing Education, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

Rawhia Salah Dogham & Heba Fakieh Mansy Ali

Critical Care & Emergency Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

Nermine M. Elcokany

Obstetrics and Gynecology Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

Asmaa Saber Ghaly

Faculty of Nursing, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef, Egypt

Mohamed Mahmoud Seweid

Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Alexandria, Egypt

Ayman Mohamed El-Ashry

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Ayman M. El-Ashry & Rawhia S. Dogham: conceptualization, preparation, and data collection; methodology; investigation; formal analysis; data analysis; writing-original draft; writing-manuscript; and editing. Heba F. Mansy Ali & Asmaa S. Ghaly: conceptualization, preparation, methodology, investigation, writing-original draft, writing-review, and editing. Nermine M. Elcokany & Mohamed M. Seweid: Methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data collection, writing-manuscript & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript and accept for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ayman Mohamed El-Ashry .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The research adhered to the guidelines and regulations outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (DoH-Oct2008). The Faculty of Nursing’s Research Ethical Committee (REC) at Alexandria University approved data collection in this study (IRB00013620/95/9/2022). Participants were required to sign an informed written consent form, which included an explanation of the research and an assessment of their understanding.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dogham, R.S., Ali, H.F.M., Ghaly, A.S. et al. Deciphering the influence: academic stress and its role in shaping learning approaches among nursing students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs 23 , 249 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01885-1

Download citation

Received : 31 January 2024

Accepted : 21 March 2024

Published : 17 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01885-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Academic stress

- Learning approaches

- Nursing students

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Saudi J Anaesth

- v.12(2); Apr-Jun 2018

Knowledge and attitudes of nurses toward pain management

Osama abdulhaleem samarkandi.

Department of Basic Science, Sultan College for Emergency Medical Services, King Saud University, Riyadh, KSA

Background:

Pain control is a vitally important goal because untreated pain has detrimental impacts on the patients as hopelessness, impede their response to treatment, and negatively affect their quality of life. Limited knowledge and negative attitudes toward pain management were reported as one of the major obstacles to implement an effective pain management among nurses. The main purpose for this study was to explore Saudi nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward pain management.

Cross-sectional survey was used. Three hundred knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain were submitted to nurses who participated in this study. Data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS; version 17).

Two hundred and forty-seven questionnaires were returned response rate 82%. Half of the nurses reported no previous pain education in the last 5 years. The mean of the total correct answers was 18.5 standard deviation (SD 4.7) out of 40 (total score if all items answered correctly) with range of 3–37. A significant difference in the mean was observed in regard to gender ( t = 2.55, P = 0.011) females had higher mean score (18.7, SD 5.4) than males (15.8, SD 4.4), but, no significant differences were identified for the exposure to previous pain education ( P > 0.05).

Conclusions:

Saudi nurses showed a lower level of pain knowledge compared with nurses from other regional and worldwide nurses. It is recommended to considered pain management in continuous education and nursing undergraduate curricula.

Introduction

Pain is a major stressor facing hospitalized patients.[ 1 ] There is a growing awareness on the etiology of pain, together with the advancement of pharmacological management of pain. Despite this awareness and pharmacological advancement, patients still experience intolerable pain which hampers the physical, emotional, and spiritual dimension of the health.[ 2 , 3 ] Pain control is important in the management of patients because untreated pain has a detrimental impact on the patient's quality of life.[ 4 ] Nurses spend a significant portion of their time with patients. Thus, they have a vital role in the decision-making process regarding pain management. Nurses have to be well prepared and knowledgeable on pain assessment and management techniques and should not hold false beliefs about pain management, which can lead to inappropriate and inadequate pain management practices.[ 5 , 6 ]

Several studies have described the barriers to delivery of an effective pain management.[ 4 , 5 ] Limited knowledge and negative attitude of nurses toward pain management were reported as major obstacles in the implementation of an effective pain management.[ 7 , 8 ] Nurses may have a negative perception, attitude, and misconception toward pain management.[ 6 , 9 , 10 ] Misconceptions include the belief that patients tend to seek attention rather report real pain, that the administration of opioids results in quick addiction, and that vital signs are the only way to reflect the presence of pain.[ 11 ] Several interventions have been attempted to address these provider-related barriers. Addressing these barriers resulted in a significant improvement in the health-care team attitudes and practice toward pain management.[ 5 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]

There is inconsistency, however, between practice and attitude, which suggests that nurses may have positive attitude toward pain management but does not have adequate knowledge to manage pain correctly and completely.[ 16 , 17 ] Furthermore, nurses who have low salaries and have role confusion in pain management are usually the ones who have poor knowledge of pain management.[ 18 ]

Knowledge deficit about pain management is not uncommon among health-care professionals. It is estimated that around 50% of health-care providers reported lack of knowledge in relation to pain assessment and management.[ 19 , 20 ] One study assessed Sri Lankan nurses’ attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge about cancer pain management and showed that poor behavior toward pain management was related to knowledge deficit and lack of authority.[ 21 ] A study on Chinese nurses showed that poor knowledge about pain management is linked with negative attitudes regarding pain management.[ 10 ] It was emphasized that an education program is effective on the nurses’ increased knowledge level and better attitudes toward pain management.[ 22 ] The practice setting influences nurses’ knowledge level of pain management. Nurses who worked in a hospice setting have relatively higher knowledge level compared with their counterparts’ who worked in district hospitals.[ 23 ]

There is a paucity of literature about nurses’ knowledge regarding pain management in the Arab world including Saudi Arabia. This study was conducted to identify nurses’ knowledge about pain management, assess nurses’ strengths and weakness in managing patients’ pain, and help nursing scholars to modify courses to improve nurses’ output regarding pain management.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in three selected hospitals that represent the health-care sector in Saudi Arabia from north, middle, and south regions in Riyadh city. All selected hospitals were referral hospitals. Nurses who work in the oncology, medical ward, surgical ward, burn units, emergency room, operation room, and Intensive Care Units in each hospital were invited to participate in this study. The researcher recruited 300 convenient nurses from the settings this number has been calculated using sample size calculator which is public service of Creative Research Systems website (Creative Research Systems, 2009).[ 24 ] Nurses who hold a degree in nursing at least agreed to participate in the study and have been working in hospitals for at least 6 months were included in this study.

A data collection sheet (DDS) was used to gather data from nurses. The DDS included questions designed to elicit information about participants’ (nurses) demographic characteristics such as sex, age, place of work, education level, previous postregistration pain education, area, and duration of clinical experience.

A knowledge and attitudes survey (KAS) section of the data collection was used to gather data about pain management. It is a 38-item questionnaire was used to assess nurses’ knowledge and attitudes toward pain management.[ 25 ] It consists of 22 “True” or “False” questions and 16 multiple-choice questions. The last two multiple choice questions were case studies. It covers areas of pain management, pain assessment, and the use of analgesics. The KAS is the only available instrument to measure nurse knowledge attitudes about pain management.[ 26 ] The KAS has an established content validity by a panel of pain experts, which was based on the American Pain Society, the World Health Organization, and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research pain management guidelines. No permission was required to use this KAS survey tool since the authors allowed its use for research. It will be used in the English language since that nurses can understand and answer questions in English.

The recruitment of participants started with the researchers obtaining the ethical approval of the study from the Deanship of Scientific Research, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The researchers visited the hospitals and explained the study aims, procedure, and participant's role. Nurses who showed interest for the study were recruited and were asked to sign the consent form. The study questionnaire was introduced to each participant, and each participant was asked to answer the questions. Completed questionnaires were collected personally by the researchers once the participants have completed them. Then questionnaires were checked for missed items.

Data were entered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Results are reported as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and as means and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Independent t test was used to compare the mean total scores between gender and previous exposure to pain education. Analysis of variation (ANOVA) was used to determine the significant difference in the mean total knowledge score and educational level. Spearman correlation was used to determine the correlation between variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 247 nurses completed and returned the study questionnaire. As shown in Table 1 , 83.3% of participants were females with a mean age of 32.9 (SD 7.9) and range from 23 to 60 years. Most of the nurses had a diploma in nursing (71.9%), Indian (27.9%), and working in medical and surgical wards (23.9%). Further, 50.6% of nurses reported no previous pain education in the last 5 years.

Nurses demographics and professional characteristics ( n =247)

Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management

The percentages of the correctly answered items in the questionnaire are shown in Table 2 . The mean of the total correct answers was 18.5 (SD 4.7) out of 40 (total score if all items answered correctly) with range of 3–37. The results show that many items were incorrectly answered and were mainly related to (a) the recommended rout of opioid administration; (b) the recommended opioid doses and the use of adjuvant medications; (c) ability to assess and reassess pain and decided on the appropriate opioids dose, (d) ability to identify signs and symptoms of addiction, tolerance, and physical dependency. Around 15.4% of the nurses failed to recognize the presence of pain because the vital signs were normal and that patients showed relaxed facial expressions. Around 15.4% of the nurses were not able to decide on which morphine dose to be used (item 38, 8.9%). Only 20% of nurses agreed that patients can sleep in spite the presence of pain. Around 78.9% of the nurses agreed that the patient is the only reliable source in reporting pain. Overall, it was found that nurses were weak in the pharmacological interventions with regard to appropriate selection, dosing, and converting between different types of opioids.

Correctly answered items in the questionnaire

The comparison of some questions revealed discrepancy between the nurses’ beliefs and practices. For example, 78.9% of the nurses agreed that the patient is the most reliable source for reporting pain, but 55.9% of the nurses would encourage their patient to tolerate the pain before giving them any pain medications. Furthermore, nurses were found to have negative attitude toward pain and its management. For example, only 33.6% of nurses thought that using a placebo is not useful in treating pain and 44.5% correctly knew that patients can be distracted from pain despite the presence of severe pain.

Significant differences in the mean were observed with regard to gender ( t = 2.55, P = 0.011). Females had a higher mean score (18.7, SD 5.4) than males (15.8, SD 4.4). There were no significant differences in between gender with regard to the exposure to previous pain education ( P > 0.05). One-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in the mean total knowledge score with regard to educational levels. Spearman's correlation test showed a positive significant relationship with years of experience ( r = 0.163, P = 0.022) to the mean total knowledge and attitude score, but not for the age ( r = 0.057, P = 0.487).

The results of the current study demonstrated that the surveyed nurses had limited knowledge of pain management, and it was associated with poor attitude toward pain management. This is mainly related to their information on pharmacological pain therapy such as the use of opioids in Saudi Arabia. The average KAS score in the present study was 18.5, which was low compared to studies reported elsewhere.[ 27 , 28 ] The results of this study are consistent with prior studies on pain management knowledge performed in other Middle Eastern countries that nurses have limited information on the management of pain,[ 12 , 25 , 29 ] and asserted a previous assumption that nurses have poor knowledge of pain management in the KSA.[ 30 ] On the contrary, this study reported a lower percentage of correct answers in contrast to Eaton et al ., who reported a higher percentage of correct answer at 73.8%.[ 2 ] A Turkish study showed nurses knowledge and attitudes using the knowledge and attitudes survey regarding pain (KASRP) correct rate of 35.4%, which was lower than the current study.[ 31 ] This may be due to the nursing curriculum which covers pain management in education and training. Furthermore, few participants (11.9%) attended pain management courses at their workplace. This explains the shortage of the continuing medical education courses on topics such as pain management skills and updates. Altogether, the results of this study emphasize the need for further training and education on pain management.[ 7 ]

The participating nurses in this study are typical of the workforce make up in Saudi Arabia. The participants were from diverse cultures, ethnic, religious groups, and backgrounds. There were previous studies that used KAS which focused mainly on culturally homogeneous nurse populations. Interestingly, there was a significant difference in the mean KASRP scores between the nurses from South Africa, the KSA, Middle East, Philippines, and India.[ 4 , 12 , 32 ] This variation was attributed to the cultural factors which reflected a possible variation in the level of covering pain management topics in the undergraduate education in different countries. This study, however, was not able to assess the effect of culture, ethnicity, religious background, and nationality of the participants on their knowledge of pain management.

In the current study, participants assumed that changes in vital signs represented the intensity of the experienced pain level. This faulty belief is linked with the pain assessment process, but it is not limited to the present sample of nurses. Almost one-third (32%) of the participants in a study believed that pain intensity and changes in vital signs were positively correlated.[ 33 ] Studies emphasized the importance of assessing nonverbal cues and behavioral manifestations as a pain indicator, as physiological changes in vital signs. In this sense, nurses may have thought that pain interferes with desire to sleep. The limited knowledge concerning this element was evident when (45.6%) of the participants incorrectly believed that patients can be distracted easily from pain usually do not have pain of any considerable severity.

A further area of concern in which the participants achieved low scores is in the questions on pharmacology– again. The shortfall in their knowledge seems to once again be traced to mistaken beliefs. Their misunderstanding of the pharmacology of analgesics specifically the opioids is much in line with the previous studies that identified items related to the pharmacology as vital in pain management and has therefore been given substantial significance in the KASRP survey result reporting.[ 4 , 34 ] This suggests that basic knowledge about pharmacological approaches is mandatory for managing pain. This study further demonstrated the lack of knowledge and the inappropriate approaches to addiction and respiratory depression originating from opioid use. The study highlighted several misconceptions about the effects of opioid analgesics. Majority of the participants (74.1%) correctly identified the definition of addiction, but they were unable to distinguish between terms such as addiction, tolerance, and physical dependence. This can be due to the variation between different patient populations and treatment regimens. It is least likely to happen when opioids are used for acute pain management specifically, and addiction to opioids is not considered to be an issue emanating from pain management of acute surgical procedures.[ 35 ] A previous study reported that only 38.1% of nurses were able to classify morphine addiction as a possibility with PRN Pro re nata (as-needed) treatment.[ 30 ] Being exposed to education sessions about pain management did not influence participants’ knowledge toward pain management, which is inconsistent with other studies which indicated the benefits of pain education courses on the nurses’ knowledge.[ 28 , 29 , 32 ]

It is clear that there is an urgent need to develop the practice knowledge of nurses with respect to pain management in Saudi Arabia. If not addressed then this could have detrimental effects on patients who are inappropriately treated. Patients’ anxiety levels may increase, and it is likely to lead patients feeling disappointed with the nursing care received. The recent trends at international level focus on integrating pain and its management to improve nurses’ knowledge and attitudes in relation to pain management. Modern programs have been implemented in Australia, the USA, and Sweden, suggesting that there is considerable room for local improvement.[ 36 , 37 ]

The strengths of this study include the verification of the knowledge deficit in pain management among Saudi nurses which necessitate the need for further studies. However, the study was limited by the small sample size and selection bias which resulted from the convenience sampling technique. Moreover, the design of this study was cross-sectional and the fact that some participants might not have responded to the survey.

Conclusions

This study has shown that Saudi nurses had low level of pain management knowledge and attitudes particularly in the issues related to myths of pain medication. It is recommended to considered pain management in continuous education and nursing undergraduate curricula. Moreover, further studies are needed to identify and overcome barriers of pain management among Saudi nurses and to evaluate the effectiveness of conducted pain management courses.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the Research Group Project No. RG-1438-050. We are also grateful to the Vice-Deanship of Postgraduate Studies and Research at the King Saud University and the KSU Prince Sultan College of Emergency Medical Services, for the support provided to the authors of this study.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A team of health professionals and experts in pain management, comprising representatives from epidemiology, geriatric medicine, pain medicine, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, psychology, pharmacology and service users, was formed to initiate a systematic review and provide an update on the 2013 publication. 1 The team included ...

Nurses continue to need mentorship and support after graduation to maintain the process of critical thinking and questioning that initiate and propel research and EBP projects (. Ryan, 2016. ). The American Society of Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN) Research Committee promotes pain management nurses' engagement in research and EBP.

Methods. Medical records were examined for 37 adults hospitalized during April and May of 2013. Nursing pain documentations (N = 230) were reviewed using an evaluation tool modified from the Cancer Pain Practice Index to consist of 13 evidence-based pain management indicators, including pain assessment, care plan, pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, monitoring and treatment of ...

This peer-reviewed journal offers a unique focus on the realm of pain management as it applies to nursing. Original and review articles from experts in the field offer key insights in the areas of clinical practice, advocacy, education, administration, and research. Additional features include practice guidelines and pharmacology updates.

INTRODUCTION. Pain is a common condition encountered by healthcare professionals, especially those providing care for older patients. 1) Pain is associated with significant disability, reduced mobility, falls, anxiety, depression, and social isolation. 1, 2) In addition, pain is a frequent complication of patients admitted to hospitals and negatively impacts multiple aspects of health ...

The American Society for Pain Management Nursing recommends relying on pain-related behaviors to evaluate and treat pain among intubated patients or patients with communication deficits. 4 Several nonverbal scales have been approved as valid tools for pain assessment among adult critically ill patients, such as the Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS ...

Engaging Pain Management Nurses in Research and Evidence-Based Practice. Engaging Pain Management Nurses in Research and Evidence-Based Practice Pain Manag Nurs. ... 4 University of North Carolina Greensboro School of Nursing, Greensboro, North Carolina. PMID: 33895089 DOI: 10.1016/j.pmn.2021.03.005 No abstract available.

The web-based questionnaire contained 11 demo-graphic questions and an open-ended, qualitative question regarding nurses' perceived challenges treat-ing patients with pain management needs. Data were collected, stored, and analyzed on Qualtrics. Only members of the research team had access to the data.

The American Society of Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN) Research Committee promotes pain management nurses' engage- ment in research and EBP. As members of the Research Com- ... Editorial / Pain Management Nursing 22 (2021) 247-249 249 Timothy Joseph Sowicz, Ph.D., NP-C University of North Carolina Greensboro School of Nursing,

Official Journal of the American Society for Pain Management Nursing. This peer-reviewed journal offers a unique focus on the realm of pain management as it applies to nursing. Original and review articles from experts in the field offer key insights in the areas of clinical practice, advocacy, education, administration, and research.

Nonnarcotic Methods of Pain Management. Author: Nanna B. Finnerup, M.D. Author Info & Affiliations. Published June 19, 2019. N Engl J Med 2019;380: 2440 - 2448. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1807061. VOL ...

Ineffective pain management can lead to a marked decrease in desirable clinical and psychological outcomes and patients' overall quality of life. Effective management of acute pain results in improved patient outcomes and increased patient satisfaction. Although research and advanced treatments in improved practice protocols have documented ...

About 4 out of 10 hospitalized adult patients suffer from pain. Pain management is a nursing activity comprising basic components of the nursing process; assessment, diagnosis, planning, intervention, and evaluation for patients in pain. ... Pain Research and Management, 2020. 10.1155/2020/6036575 [PMC free article] [Google Scholar] Marie B. S ...

The American Society for Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN) has reviewed and updated its position statement on the use of authorized agent controlled analgesia (AACA) for patients who are unable to independently utilize a self-dosing analgesic infusion pump, commonly known as patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). ASPMN continues to support the use of AACA to provide timely and effective pain ...

In addition, this study aims to elucidate these nurses' attitudes about sharing their pain knowledge with their colleagues. Design, participants and methods: This study includes semi-structured interviews of 17 registered staff nurses at the University Hospital, Linköping Sweden. The interviews were analyzed using a qualitative content analysis.

Latest articles 'Latest articles' are articles accepted for publication in this journal but not yet published in a volume/issue. Articles are removed from the 'Latest articles' list when they are published in a volume/issue. Latest articles are citable using the author(s), year of online publication, article title, journal and article DOI.

An early Clinical Practice Guideline on Acute Pain Management released by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research addressed assessment and management of acute pain. 22 This guideline outlines a comprehensive pain evaluation that would be most useful when obtained prior to the surgical procedure. In the pain history, the nurse identifies ...

the research literature: pain or opioid use, health care professional perspectives, nonopioid management of pain, and guidelines affecting research (Table 2). The majority of research publications addressed thetopicofpainoropioid misuse(57%,31of54). Among the research articles, the most frequently used measures to assess

UC Davis medical students undergo more than 100 hours of required and dedicated total pain medicine educational content during their four years of training. The School of Medicine is now among the leading medical schools in the world for pain management education. Need for increased training in pain management

Objective: to analyse research articles on pain and nursing issues using bibliometric and scientometric methodologies. Method: articles in the Web of Science database containing pain and nurse and pain and nursing were analyzed using scientometric methods through data visualization techniques and advanced text analytics. Result: among the 107,559 research articles found in the field of nursing ...

Here, we review the state-of-the-art in human pain research, summarizing emerging practices and cutting-edge techniques across multiple methods and technologies. For each, we outline foreseeable technosocial considerations, reflecting on implications for standards of care, pain management, research, and societal impact.

Pain Management Nursing: Official Journal of the American Society of Pain Management Nurses. 2019; 20: 503-511. Abstract; Full Text; ... and increasing evidence-based recommendations for pain management, research still shows suboptimal pain assessment and treatment in the NICU (Anand et al., 2017. Anand K.J.S. Eriksson M. Boyle E.M. Avila ...

Background Nursing education presents unique challenges, including high levels of academic stress and varied learning approaches among students. Understanding the relationship between academic stress and learning approaches is crucial for enhancing nursing education effectiveness and student well-being. Aim This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of academic stress and its correlation ...

A knowledge and attitudes survey (KAS) section of the data collection was used to gather data about pain management. It is a 38-item questionnaire was used to assess nurses' knowledge and attitudes toward pain management. [ 25] It consists of 22 "True" or "False" questions and 16 multiple-choice questions.

S. Grommi, A. Vaajoki, A. Voutilainen et al. / Pain Management Nursing 24 (2023) 456-468 457 Thus, knowledge of pain, pain management, and assessment alone are not sufficient. Theoretical knowledge must be applied in prac- ... the articles that did not answer the research questions, whose language of reporting was other than Finnish or ...

The total family functioning scores were not correlated with pain intensity scores, and further analyses revealed that the positive communication dimension of family functioning was positively correlated with the average pain (r = 0.16, p < .05), the egotism dimension was positively correlated with the worst pain (r = 0.14, p < .05) and the ...