12 SMART Goals Examples for Problem Solving

Everyone should aim to develop their problem-solving skills in life. It’s critical for career growth and personal development. That’s why establishing SMART goals is a valuable tool for achieving success and reaching desired outcomes.

This article will provide SMART goals examples for effective problem solving. Gaining inspiration to pursue these goals can help you become more organized and effective in problem-solving situations.

Table of Contents

What is a SMART Goal?

The SMART framework is an amazing way to establish practical goals . For those unaware, SMART stands for specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-based.

Still confused? SMART goals are:

- Specific: Accomplishing goals starts with defining them and how they will be achieved. The more detailed your goals for problem solving, the greater the likelihood you have of meeting them.

- Measurable: Having a quantifiable goal is a crucial SMART component. Tracking your progress makes modifying or adjusting the path forward easier if needed. You’ll also have a tangible way to determine whether or not your objectives have been met.

- Attainable: Try to decide on what is realistically possible before pursuing goals. If possible, break down your overarching goal into smaller objectives that fall within your current capabilities. Setting too high or unrealistic expectations cause you frustration and even giving up on your aspirations altogether.

- Relevant: You must align your actions with your core values . Hence, take some time to reflect on how you want your goals to reflect your interests and values.

- Time-based: Success doesn’t come without hard work and dedication, so you should have a specific timeline when working toward your dreams. You will stay organized and motivated throughout the journey when you set a deadline.

In today’s world, being able to identify and solve problems using analytical skills can’t be undervalued. Following the 5 SMART criteria above will allow you to achieve better results with fewer resources.

Here are 12 examples of SMART goals for better problem solving:

1. Define the Problem

“I’ll create a plan to define and describe the problem I’m trying to solve by the end of two weeks. This will allow me to identify the exact issue that needs to be addressed and develop an effective solution promptly.”

Specific: The goal outlines the task of defining and describing a problem.

Measurable: You can measure your progress by creating a plan after two weeks.

Attainable: The statement is within reach because it requires critical thinking and planning.

Relevant: Defining an issue is required for enhanced problem solving.

Time-based: There is a two-week timeline for accomplishing this goal.

2. Analyze Root Cause

“I will take the time to thoroughly analyze the root cause of a problem before I attempt to come up with a solution. Before jumping into a solution, I’ll consider the possible causes and try to figure out how they interact with each other.”

Specific: The SMART goal outlines what will be done to analyze the root cause of a problem.

Measurable: You could measure how often you take the time for analysis.

Attainable: This is realistic because taking the time to do a thorough analysis is possible.

Relevant: Gaining a better understanding of the root causes of a problem can lead to more effective solutions.

Time-based: You’ll follow this process every time you solve a problem, so this goal is ongoing.

3. Be Willing to Collaborate With Others

“For the duration of 10 months, my goal is to be willing to collaborate with others to find the best solution for any problem at hand. I want to be open to exchanging ideas and listening to the opinions of others so that we can solve our problems efficiently.”

Specific: The person must proactively strive to collaborate with others.

Measurable: You can keep track of how often you collaborate monthly.

Attainable: This is feasible because it requires only the willingness to collaborate and exchange ideas.

Relevant: Collaboration allows you to find better solutions and grow your network.

Time-based: You have 10 months to pursue this particular target.

4. Evaluate Alternatives

“I will review and evaluate at least three alternative solutions to the problem by the end of this month. I’ll evaluate the costs and benefits of each solution, prioritize them based on their potential effectiveness and make my recommendation.”

Specific: You will need to review and evaluate three alternative solutions.

Measurable: Count how many alternative solutions you listed.

Attainable: With enough time and effort, anybody can review and evaluate multiple solutions.

Relevant: This is related to problem solving, which can advance your professional career .

Time-based: You have one month for goal achievement.

5. Implement Action Plan

“To ensure that my action plans are implemented effectively, I will create a timeline with concrete steps and review it every two weeks for the 6 months ahead. I want all aspects of my plan to take place as scheduled and the process is running smoothly.”

Specific: The aim is to create a timeline and review it every two weeks for 6 months.

Measurable: The person can compare their timeline to the actual results and ensure that every aspect of the plan takes place as scheduled.

Attainable: This goal is achievable if the individual has the time, resources, and support.

Relevant: Realize that implementing an action plan applies to problem solving.

Time-based: Success will be reached after 6 whole months.

6. Ask the Right Questions

“I’ll learn to ask the right questions by reading two books on effective questioning strategies and attending a workshop on the same topic within the next quarter. This will allow me to get to the root of any problem more quickly.”

Specific: The goal states what to do (read two books and attend a workshop) to learn how to ask the right questions.

Measurable: You can check your progress by reading the books and attending the workshop.

Attainable: This is a reasonable goal and can be met within the given time frame.

Relevant: Asking the right questions is key to solving any problem quickly.

Time-based: Goal completion should be accomplished within a quarter.

7. Be More Flexible

“I will seek opportunities to be more flexible when problem solving for the following 8 months. This could include offering creative solutions to issues, brainstorming ideas with colleagues, and encouraging feedback from others.”

Specific: This SMART goal is explicit because the person wants to become more flexible when problem solving.

Measurable: Check how often and effectively you follow the three action items.

Attainable : This goal is achievable if you dedicate time to being more open-minded.

Relevant: Flexibility is integral to problem solving, so this goal is highly relevant.

Time-based: Eight months is the allotted time to reach the desired result.

8. Brainstorm Solutions

“I want to develop a list of 5 potential solutions by the end of this month for any problem that arises. I’ll brainstorm with my team and research to develop the options. We’ll use these options to evaluate the most feasible solution for a specific issue.”

Specific: You should come up with a list of 5 potential solutions with your team.

Measurable: Actively count how many potential solutions you come up with.

Attainable: This goal can be achieved with research and collaboration.

Relevant: Brainstorming solutions help you evaluate the best option for a certain issue.

Time-based: You should strive to meet this goal by the end of the month.

9. Keep a Cool Head

“When encountering a difficult problem, I will strive to remain calm and not rush into any decisions. For three months, I’ll take a few moments to pause, gather my thoughts and assess the situation with a clear head before taking action.”

Specific: The person identifies the goal of remaining calm when encountering complex problems.

Measurable: It is possible to measure success in terms of how long it takes to pause and assess the situation.

Attainable: Taking a few moments before taking action is realistic for most people.

Relevant: Keeping a cool head in difficult situations is beneficial for problem solving.

Time-based: This SMART statement has an end date of three months.

10. Don’t Make Rash Assumptions

“I will no longer make assumptions or jump to conclusions without gathering facts. I’ll strive to be more open-minded when finding solutions to problems and take the time to consider all perspectives before making a decision.”

Specific: The goal is explicit in that individuals aim to be open-minded.

Measurable: You can evaluate how often assumptions are made without gathering facts or considering all perspectives.

Attainable: Anyone can take the time to consider different perspectives before making a decision.

Relevant: This is suitable for those who want to be more mindful and make better decisions.

Time-based: Since the goal is ongoing, you will pursue it on a daily basis.

11. Take Responsibility

“I will take responsibility for all my mistakes and be open to constructive criticism to improve as a professional by the end of the next quarter. I’ll also learn from my mistakes and take steps to ensure they’re not repeated.”

Specific: The statement is evident in that you will take responsibility for all mistakes.

Measurable: Progress towards this goal can be measured by how well you respond to constructive criticism.

Attainable: This is possible since the person is willing to learn and improve with constructive criticism.

Relevant: Taking responsibility for your mistakes is an important skill, making this an appropriate goal.

Time-based: You have one quarter to complete the SMART goal.

12. Let Your Creativity Flow

“I want to explore the range of my creative problem-solving abilities and come up with solutions for difficult situations. To do this, I’ll take a course in creative problem solving and apply the principles I learn to practical scenarios within two months.”

Specific: You will take a course in creative problem solving and apply the principles learned to practical scenarios.

Measurable: By enrolling in the course, you can monitor your learning progress over time.

Attainable: The goal should be realistic concerning time and resources.

Relevant: Recognize that creativity is vital in many industries.

Time-based: You should ideally reach this goal after two months.

Final Thoughts

Setting SMART goals is a fantastic approach to solving any problem. They provide a clear structure for breaking down complex tasks into manageable chunks and encourage goal-oriented thinking.

While SMART goals may not work for every situation, they can offer a valuable framework for solving complex issues. Thus, it’s beneficial to experiment with this tool to develop problem-solving strategies tailored to individual needs.

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

10 Problem-solving strategies to turn challenges on their head

Jump to section

What is an example of problem-solving?

What are the 5 steps to problem-solving, 10 effective problem-solving strategies, what skills do efficient problem solvers have, how to improve your problem-solving skills.

Problems come in all shapes and sizes — from workplace conflict to budget cuts.

Creative problem-solving is one of the most in-demand skills in all roles and industries. It can boost an organization’s human capital and give it a competitive edge.

Problem-solving strategies are ways of approaching problems that can help you look beyond the obvious answers and find the best solution to your problem .

Let’s take a look at a five-step problem-solving process and how to combine it with proven problem-solving strategies. This will give you the tools and skills to solve even your most complex problems.

Good problem-solving is an essential part of the decision-making process . To see what a problem-solving process might look like in real life, let’s take a common problem for SaaS brands — decreasing customer churn rates.

To solve this problem, the company must first identify it. In this case, the problem is that the churn rate is too high.

Next, they need to identify the root causes of the problem. This could be anything from their customer service experience to their email marketing campaigns. If there are several problems, they will need a separate problem-solving process for each one.

Let’s say the problem is with email marketing — they’re not nurturing existing customers. Now that they’ve identified the problem, they can start using problem-solving strategies to look for solutions.

This might look like coming up with special offers, discounts, or bonuses for existing customers. They need to find ways to remind them to use their products and services while providing added value. This will encourage customers to keep paying their monthly subscriptions.

They might also want to add incentives, such as access to a premium service at no extra cost after 12 months of membership. They could publish blog posts that help their customers solve common problems and share them as an email newsletter.

The company should set targets and a time frame in which to achieve them. This will allow leaders to measure progress and identify which actions yield the best results.

Perhaps you’ve got a problem you need to tackle. Or maybe you want to be prepared the next time one arises. Either way, it’s a good idea to get familiar with the five steps of problem-solving.

Use this step-by-step problem-solving method with the strategies in the following section to find possible solutions to your problem.

1. Identify the problem

The first step is to know which problem you need to solve. Then, you need to find the root cause of the problem.

The best course of action is to gather as much data as possible, speak to the people involved, and separate facts from opinions.

Once this is done, formulate a statement that describes the problem. Use rational persuasion to make sure your team agrees .

2. Break the problem down

Identifying the problem allows you to see which steps need to be taken to solve it.

First, break the problem down into achievable blocks. Then, use strategic planning to set a time frame in which to solve the problem and establish a timeline for the completion of each stage.

3. Generate potential solutions

At this stage, the aim isn’t to evaluate possible solutions but to generate as many ideas as possible.

Encourage your team to use creative thinking and be patient — the best solution may not be the first or most obvious one.

Use one or more of the different strategies in the following section to help come up with solutions — the more creative, the better.

4. Evaluate the possible solutions

Once you’ve generated potential solutions, narrow them down to a shortlist. Then, evaluate the options on your shortlist.

There are usually many factors to consider. So when evaluating a solution, ask yourself the following questions:

- Will my team be on board with the proposition?

- Does the solution align with organizational goals ?

- Is the solution likely to achieve the desired outcomes?

- Is the solution realistic and possible with current resources and constraints?

- Will the solution solve the problem without causing additional unintended problems?

5. Implement and monitor the solutions

Once you’ve identified your solution and got buy-in from your team, it’s time to implement it.

But the work doesn’t stop there. You need to monitor your solution to see whether it actually solves your problem.

Request regular feedback from the team members involved and have a monitoring and evaluation plan in place to measure progress.

If the solution doesn’t achieve your desired results, start this step-by-step process again.

There are many different ways to approach problem-solving. Each is suitable for different types of problems.

The most appropriate problem-solving techniques will depend on your specific problem. You may need to experiment with several strategies before you find a workable solution.

Here are 10 effective problem-solving strategies for you to try:

- Use a solution that worked before

- Brainstorming

- Work backward

- Use the Kipling method

- Draw the problem

- Use trial and error

- Sleep on it

- Get advice from your peers

- Use the Pareto principle

- Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Let’s break each of these down.

1. Use a solution that worked before

It might seem obvious, but if you’ve faced similar problems in the past, look back to what worked then. See if any of the solutions could apply to your current situation and, if so, replicate them.

2. Brainstorming

The more people you enlist to help solve the problem, the more potential solutions you can come up with.

Use different brainstorming techniques to workshop potential solutions with your team. They’ll likely bring something you haven’t thought of to the table.

3. Work backward

Working backward is a way to reverse engineer your problem. Imagine your problem has been solved, and make that the starting point.

Then, retrace your steps back to where you are now. This can help you see which course of action may be most effective.

4. Use the Kipling method

This is a method that poses six questions based on Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “ I Keep Six Honest Serving Men .”

- What is the problem?

- Why is the problem important?

- When did the problem arise, and when does it need to be solved?

- How did the problem happen?

- Where is the problem occurring?

- Who does the problem affect?

Answering these questions can help you identify possible solutions.

5. Draw the problem

Sometimes it can be difficult to visualize all the components and moving parts of a problem and its solution. Drawing a diagram can help.

This technique is particularly helpful for solving process-related problems. For example, a product development team might want to decrease the time they take to fix bugs and create new iterations. Drawing the processes involved can help you see where improvements can be made.

6. Use trial-and-error

A trial-and-error approach can be useful when you have several possible solutions and want to test them to see which one works best.

7. Sleep on it

Finding the best solution to a problem is a process. Remember to take breaks and get enough rest . Sometimes, a walk around the block can bring inspiration, but you should sleep on it if possible.

A good night’s sleep helps us find creative solutions to problems. This is because when you sleep, your brain sorts through the day’s events and stores them as memories. This enables you to process your ideas at a subconscious level.

If possible, give yourself a few days to develop and analyze possible solutions. You may find you have greater clarity after sleeping on it. Your mind will also be fresh, so you’ll be able to make better decisions.

8. Get advice from your peers

Getting input from a group of people can help you find solutions you may not have thought of on your own.

For solo entrepreneurs or freelancers, this might look like hiring a coach or mentor or joining a mastermind group.

For leaders , it might be consulting other members of the leadership team or working with a business coach .

It’s important to recognize you might not have all the skills, experience, or knowledge necessary to find a solution alone.

9. Use the Pareto principle

The Pareto principle — also known as the 80/20 rule — can help you identify possible root causes and potential solutions for your problems.

Although it’s not a mathematical law, it’s a principle found throughout many aspects of business and life. For example, 20% of the sales reps in a company might close 80% of the sales.

You may be able to narrow down the causes of your problem by applying the Pareto principle. This can also help you identify the most appropriate solutions.

10. Add successful solutions to your toolkit

Every situation is different, and the same solutions might not always work. But by keeping a record of successful problem-solving strategies, you can build up a solutions toolkit.

These solutions may be applicable to future problems. Even if not, they may save you some of the time and work needed to come up with a new solution.

Improving problem-solving skills is essential for professional development — both yours and your team’s. Here are some of the key skills of effective problem solvers:

- Critical thinking and analytical skills

- Communication skills , including active listening

- Decision-making

- Planning and prioritization

- Emotional intelligence , including empathy and emotional regulation

- Time management

- Data analysis

- Research skills

- Project management

And they see problems as opportunities. Everyone is born with problem-solving skills. But accessing these abilities depends on how we view problems. Effective problem-solvers see problems as opportunities to learn and improve.

Ready to work on your problem-solving abilities? Get started with these seven tips.

1. Build your problem-solving skills

One of the best ways to improve your problem-solving skills is to learn from experts. Consider enrolling in organizational training , shadowing a mentor , or working with a coach .

2. Practice

Practice using your new problem-solving skills by applying them to smaller problems you might encounter in your daily life.

Alternatively, imagine problematic scenarios that might arise at work and use problem-solving strategies to find hypothetical solutions.

3. Don’t try to find a solution right away

Often, the first solution you think of to solve a problem isn’t the most appropriate or effective.

Instead of thinking on the spot, give yourself time and use one or more of the problem-solving strategies above to activate your creative thinking.

4. Ask for feedback

Receiving feedback is always important for learning and growth. Your perception of your problem-solving skills may be different from that of your colleagues. They can provide insights that help you improve.

5. Learn new approaches and methodologies

There are entire books written about problem-solving methodologies if you want to take a deep dive into the subject.

We recommend starting with “ Fixed — How to Perfect the Fine Art of Problem Solving ” by Amy E. Herman.

6. Experiment

Tried-and-tested problem-solving techniques can be useful. However, they don’t teach you how to innovate and develop your own problem-solving approaches.

Sometimes, an unconventional approach can lead to the development of a brilliant new idea or strategy. So don’t be afraid to suggest your most “out there” ideas.

7. Analyze the success of your competitors

Do you have competitors who have already solved the problem you’re facing? Look at what they did, and work backward to solve your own problem.

For example, Netflix started in the 1990s as a DVD mail-rental company. Its main competitor at the time was Blockbuster.

But when streaming became the norm in the early 2000s, both companies faced a crisis. Netflix innovated, unveiling its streaming service in 2007.

If Blockbuster had followed Netflix’s example, it might have survived. Instead, it declared bankruptcy in 2010.

Use problem-solving strategies to uplevel your business

When facing a problem, it’s worth taking the time to find the right solution.

Otherwise, we risk either running away from our problems or headlong into solutions. When we do this, we might miss out on other, better options.

Use the problem-solving strategies outlined above to find innovative solutions to your business’ most perplexing problems.

If you’re ready to take problem-solving to the next level, request a demo with BetterUp . Our expert coaches specialize in helping teams develop and implement strategies that work.

Boost your productivity

Maximize your time and productivity with strategies from our expert coaches.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

8 creative solutions to your most challenging problems

5 problem-solving questions to prepare you for your next interview, what are metacognitive skills examples in everyday life, 31 examples of problem solving performance review phrases, what is lateral thinking 7 techniques to encourage creative ideas, leadership activities that encourage employee engagement, learn what process mapping is and how to create one (+ examples), how much do distractions cost 8 effects of lack of focus, can dreams help you solve problems 6 ways to try, similar articles, the pareto principle: how the 80/20 rule can help you do more with less, thinking outside the box: 8 ways to become a creative problem solver, 3 problem statement examples and steps to write your own, contingency planning: 4 steps to prepare for the unexpected, adaptability in the workplace: defining and improving this key skill, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

The Lean Post / Articles / The Deeper Purpose of Problem-Solving

Problem Solving

The Deeper Purpose of Problem-Solving

By Régis Medina

October 27, 2020

Why problem-solving in a lean setting is a unique opportunity to think about how we think and develop expertise where it counts.

Let’s face it: we live in an illusion. That is to say, modern theories of cognition demonstrate that we do not really see what is around us. Instead, our eyes dart from one detail to the next to construct a convincing model of the world. Then we base our decisions on this model. Moreover, we are oblivious to the basic brain mechanisms that govern our actions, a phenomenon that you may have noticed when emerging from your thoughts and finding yourself in a place without remembering how you got there.

While this marvel of biology lets us accomplish great things, it also proves unreliable on many occasions. The mental structure of a mistake is “I thought that … but …,” and we make lots of them. For example, “I thought the department store was open on Sundays, but it was closed when I arrived,” or “I thought that batteries were included when I bought a clock, but they were not, and I was not able to use it when I got home.”

Mistakes are not restricted to our personal lives, of course. A typical workday is littered with errors, small and large. And this is why lean is so brilliant: It is a complete business strategy based on rooting out and fixing our misconceptions. But what does that mean in practice?

Most people interested in lean are familiar with the plan-do-check-act ( PDCA ) cycle. However, a common misconception about this method is that its main purpose is to improve processes. The logic goes like this: You find a problem, discover a missing standard, fix it, and then train everybody to use it. While this understanding is not wrong per se, it can lead to an environment where people are expected to follow too many processes without understanding why they are doing it — a dangerous situation if the company operates in a changing environment.

A better way to understand PDCA is to look at it as a means to root out misconceptions and fix the glitches in our thinking.

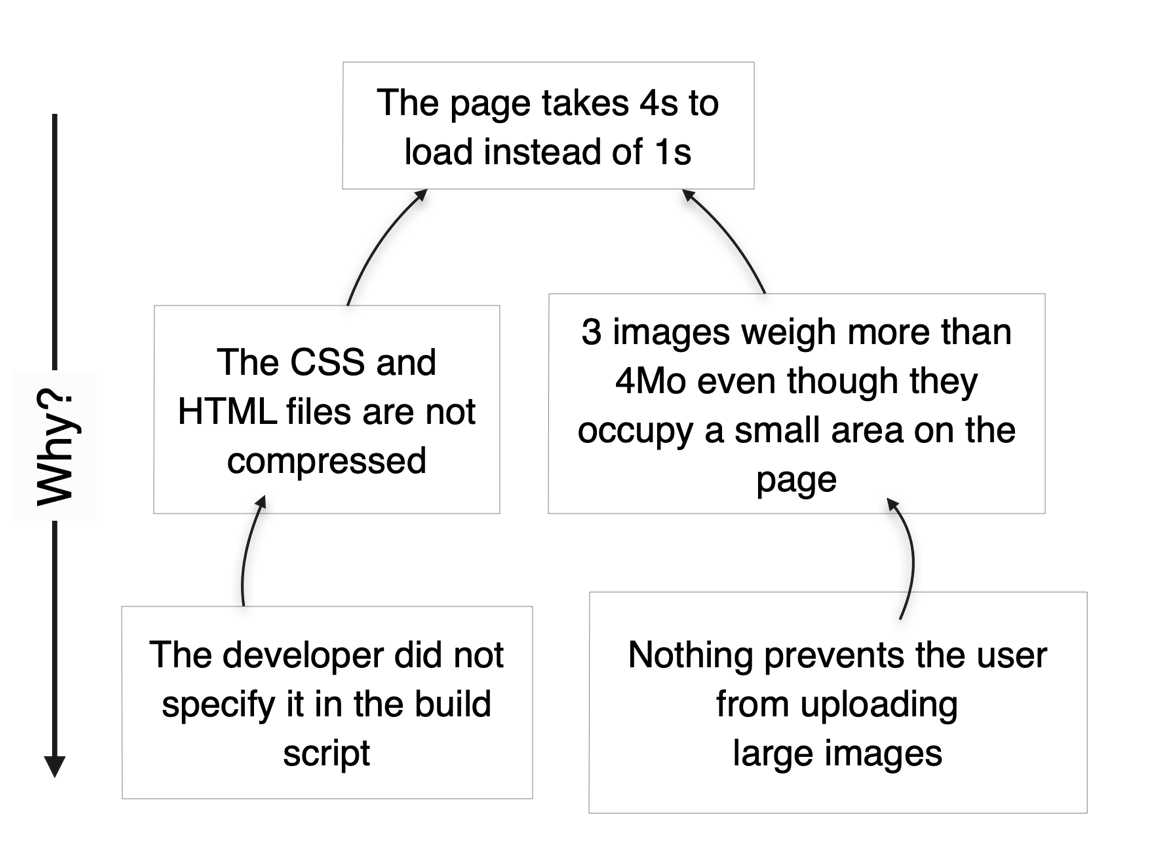

Let’s take an example. Users of a web application are complaining that pages are taking too long to load. By responding to a few “why’s,” one can easily get closer to the root of the technical problem:

While we should certainly delve deeper into the technical details to find the specific point of change to fix the issue, let’s remain at this level for the sake of argument — because we can already infer that we will end up with two kinds of countermeasures:

- Fix the build script so that CSS and HTML files are compressed and load faster.

- Add a check or warning to prevent users from uploading images larger than 1Mo, or better yet, transform the uploaded files automatically without burdening users with extra work .

The problem would probably be fixed either way, but we wouldn’t have actually learned much. We can expect the same people, and the same company, to repeat the same kind of mistakes in the future.

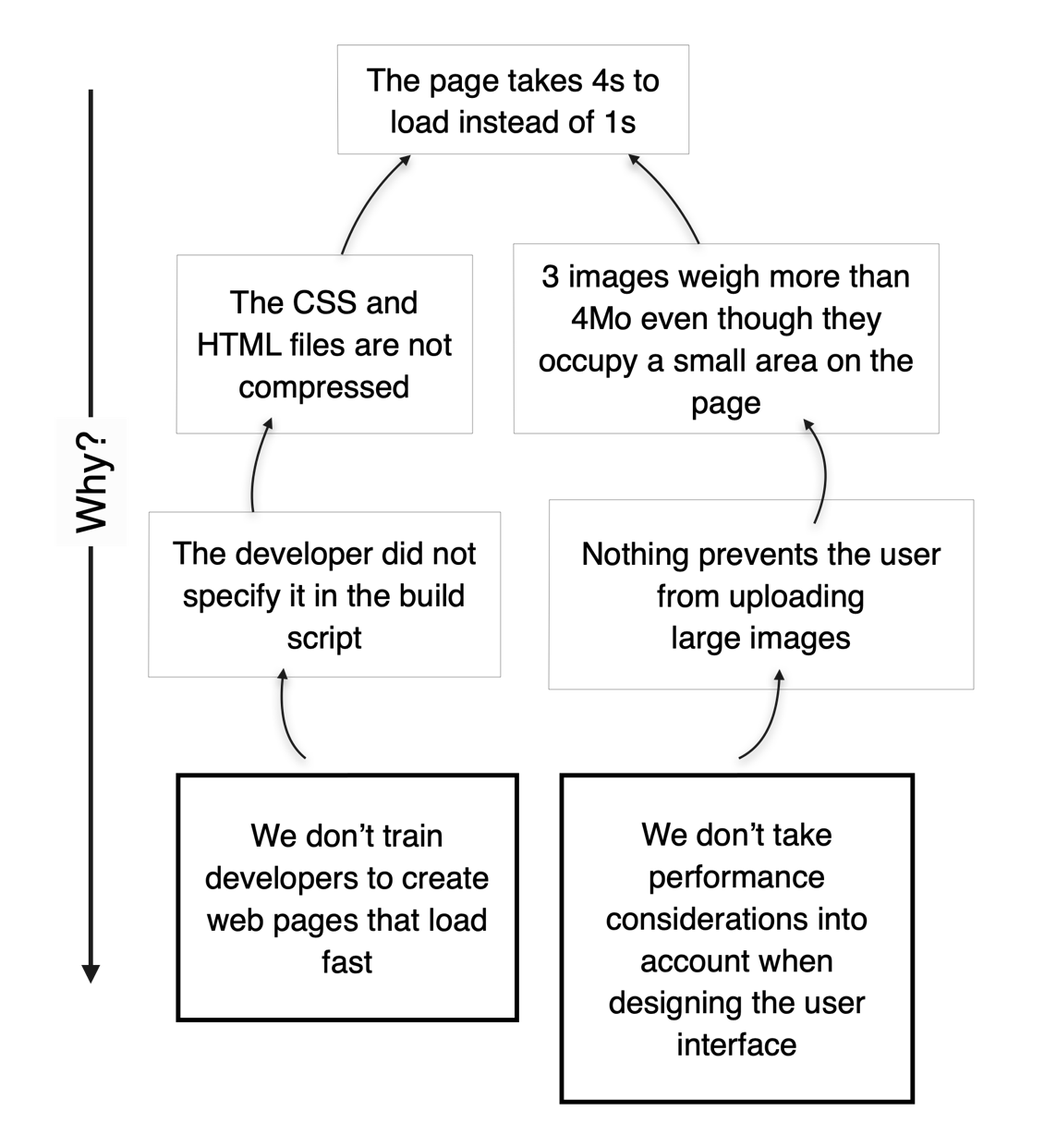

A better way to guide our search for root causes consists in trying to answer the question:

What is the mistake we keep repeating that creates this problem?

In our example, this could look like this:

By using this approach, learning can occur because it makes us aware of the shortcomings of our mental models. However, this is only the beginning.

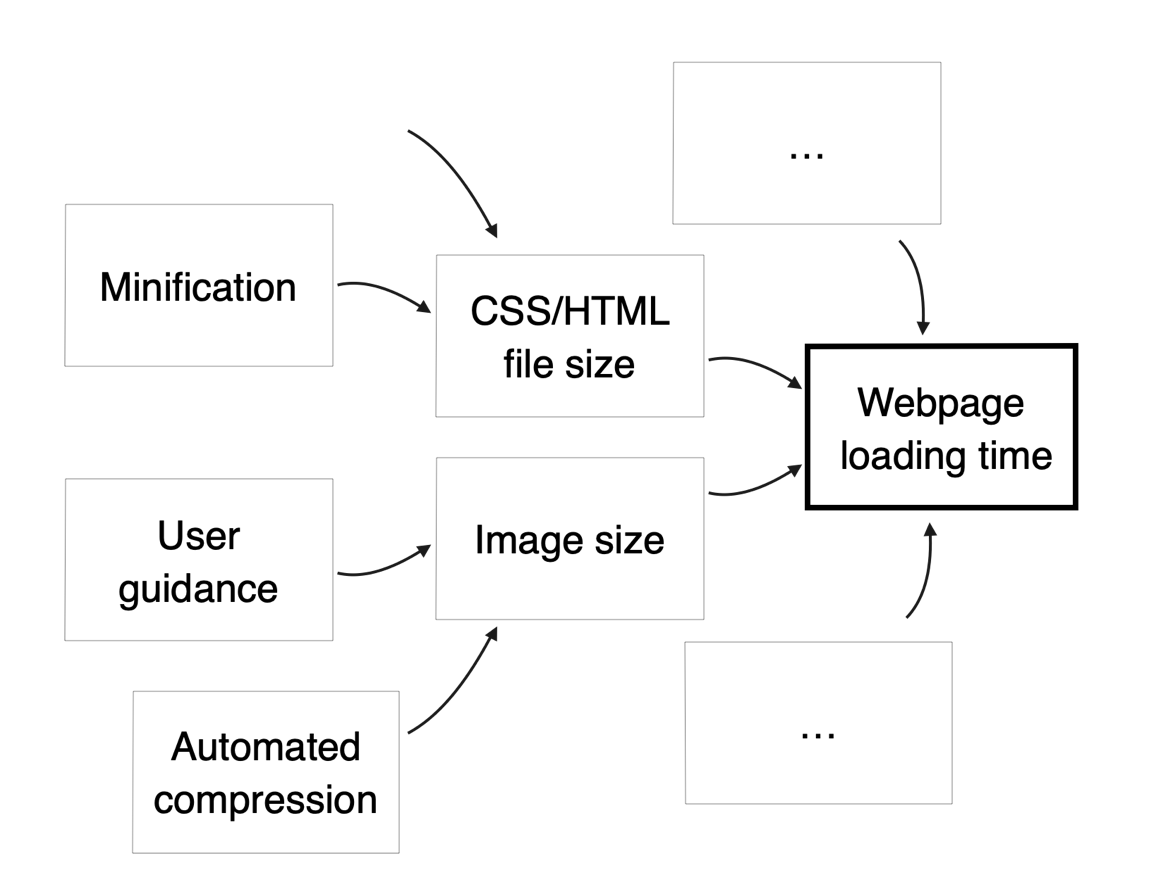

By solving problems repeatedly in a given area, we can explore the factors that influence performance and progressively build a model of these factors. In our example, this approach would look like this:

This model can then be taught, discussed, and extended because it’s a standard: a collection of knowledge points that serve as a basis for training and reflection.

Ultimately, the goal of problem-solving is not just to fix tools and processes.

By creating standards, a company can deliberately build expertise in any domain. When done on topics that directly relate to customer preferences, and when performed by everybody every day, this creates a dynamic in which people are always building knowledge and changing to adapt to customer needs, which is the essence of the lean strategy.

Ultimately, the goal of problem-solving is not just to fix tools and processes. Instead, it is a unique opportunity to think about how we think and develop expertise where it counts. In addition, it is a robust, hands-on formula to create a company that keeps adapting to changing market conditions and creates value for society over decades.

Problem Definition Practice

Improve your ability to break down problems into their specific, actionable parts.

Written by:

About Régis Medina

Régis Medina was one of the early pioneers of Agile software development methodologies in the late 90s. In 2009, he embarked on a journey to explore the practices of Toyota, eventually making several trips to Japan, while working with dozens of teams in a variety of IT activities. He now works with prominent entrepreneurs of the French Tech community to build fast and resilient scale-ups. He is the author of Learning to Scale: The Secret to Growing a Fast and Resilient Company .

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Revolutionizing Logistics: DHL eCommerce’s Journey Applying Lean Thinking to Automation

Podcast by Matthew Savas

Transforming Corporate Culture: Bestbath’s Approach to Scaling Problem-Solving Capability

Teaching Lean Thinking to Kids: A Conversation with Alan Goodman

Podcast by Alan Goodman and Matthew Savas

Related books

A3 Getting Started Guide

by Lean Enterprise Institute

The Power of Process – A Story of Innovative Lean Process Development

by Eric Ethington and Matt Zayko

Related events

August 05, 2024 | Coach-Led Online Course and Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan

Managing to Learn

September 26, 2024 | Remond, WA & Morgantown, PA

Building a Lean Operating and Management System

Explore topics.

Subscribe to get the very best of lean thinking delivered right to your inbox

Privacy overview.

Problem Solving Skills and Objectives

Regardless of what they do for a living or where they live, most people spend most of their waking hours, at work or at home, solving problems. Most problems we face are small, some are large and complex, but they all need to be solved in a satisfactory way. (Robert Harris, 1998)

Having the support of others in solving problems is important. Diversity of thought and of problem solving style can result in better solutions.

The objectives for this module are:

- Identify different problem solving styles

- Identify methods appropriate for solving problems

- Apply methods to specific problems

- Apply problem solving skills when working with children.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 License

Brought to you by CReducation.org .

404 Not found

Problem Solving: 15 Examples for Setting Performance Goals

Problem Solving: Use these examples for setting employee performance goals. Help your employees master this skill with 5 fresh ideas that drive change.

Problem Solving is the skill of defining a problem to determine its cause, identify it, prioritize and select alternative solutions to implement in solving the problems and reviving relationships.

Problem Solving: Set Goals for your Employees. Here are some examples:

- To be accommodative of other people's ideas and views and to be willing to take them on board.

- Research well enough to gather factual information before setting out to solve a problem.

- Look at things in different perspectives and angles and to develop alternative options.

- Be willing enough to collaborate with other when it comes to problem-solving issues.

- Learn to articulate or communicate in a proper manner that can be well understood by people.

- Get first to understand what the problem really is before starting to solve it.

- Show great confidence and poise when making decisions and not afraid to make mistakes and learn from them.

- Keep a cool head when dealing with more pressing and exhausting issues.

- Try to ask the right questions that will act as a guide to coming up with proper solutions.

- Be more flexible to change and adapt to new tact and ways of finding new solutions.

Problem Solving: Improve and master this core skill with these ideas

- Identify the problem. determine the nature of the problem, break it down and come up with a useful set of actions to address the challenges that are related to it.

- Concentrate on the solution, not the problem. Looking for solutions will not happen if you focus on the problem all the time. Concentrating on finding the answer is a move that brings about new opportunities and ideas that can be lucrative.

- Write down as many solutions as possible. Listing down various solutions is important to help you keep an open mind and boost creative thinking that can trigger potential solutions. This list will also act as your reminder.

- Think laterally. Thinking laterally means changing the approach and looking at things differently as well as making different choices.

- Use positive language that creates possibilities. Using words that are active to speak to others, and yourself build a mind that thinks creatively encouraging new ideas and solutions to be set.

These articles may interest you

Recent articles.

- Skills needed to be a traffic engineer

- Skills needed to be a senior project estimator

- Outstanding Employee Performance Feedback: Inventory & Operations Auditor

- New Hire Offer Letter

- Presentation Skills: 15 Examples for Setting Performance Goals

- Poor Employee Performance Feedback: Comptroller/Controller

- 7 Steps For Developing A Performance Appraisal System

- Employee Performance Goals Sample: Chief Executive Officer

- Skills needed to be a benefits analyst

- Skills needed to be an it audit senior manager

- Employee Separation Definition, Formula And Examples

- Good Employee Performance Feedback: Invoice Control Clerk

- Good Employee Performance Feedback: Senior Cost Analyst

- Top 28 Employee Appreciation Day Activities

- Poor Employee Performance Feedback: Facilities Technician

How to improve your problem solving skills and build effective problem solving strategies

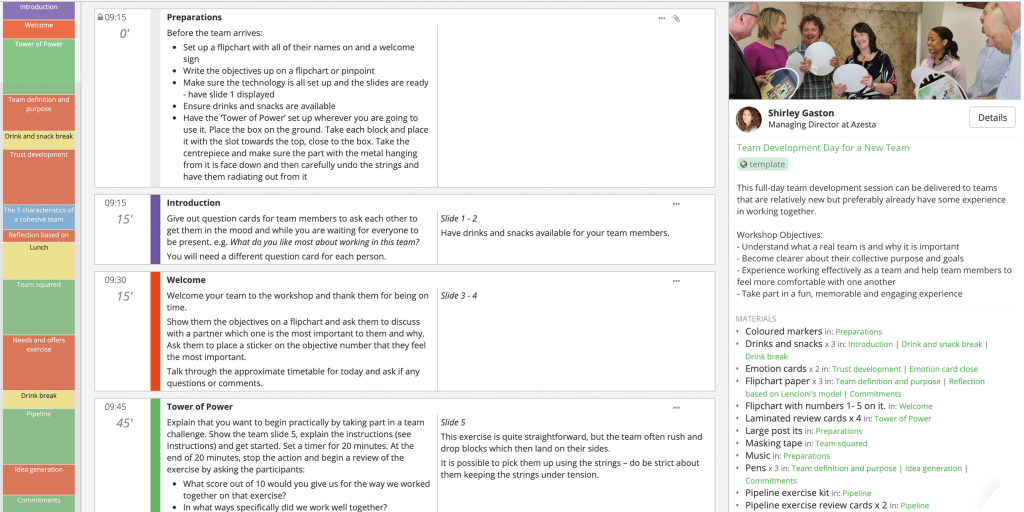

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 18 free facilitation resources we think you’ll love.

- 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation

Effective problem solving is all about using the right process and following a plan tailored to the issue at hand. Recognizing your team or organization has an issue isn’t enough to come up with effective problem solving strategies.

To truly understand a problem and develop appropriate solutions, you will want to follow a solid process, follow the necessary problem solving steps, and bring all of your problem solving skills to the table.

We’ll first guide you through the seven step problem solving process you and your team can use to effectively solve complex business challenges. We’ll also look at what problem solving strategies you can employ with your team when looking for a way to approach the process. We’ll then discuss the problem solving skills you need to be more effective at solving problems, complete with an activity from the SessionLab library you can use to develop that skill in your team.

Let’s get to it!

What is a problem solving process?

- What are the problem solving steps I need to follow?

Problem solving strategies

What skills do i need to be an effective problem solver, how can i improve my problem solving skills.

Solving problems is like baking a cake. You can go straight into the kitchen without a recipe or the right ingredients and do your best, but the end result is unlikely to be very tasty!

Using a process to bake a cake allows you to use the best ingredients without waste, collect the right tools, account for allergies, decide whether it is a birthday or wedding cake, and then bake efficiently and on time. The result is a better cake that is fit for purpose, tastes better and has created less mess in the kitchen. Also, it should have chocolate sprinkles. Having a step by step process to solve organizational problems allows you to go through each stage methodically and ensure you are trying to solve the right problems and select the most appropriate, effective solutions.

What are the problem solving steps I need to follow?

All problem solving processes go through a number of steps in order to move from identifying a problem to resolving it.

Depending on your problem solving model and who you ask, there can be anything between four and nine problem solving steps you should follow in order to find the right solution. Whatever framework you and your group use, there are some key items that should be addressed in order to have an effective process.

We’ve looked at problem solving processes from sources such as the American Society for Quality and their four step approach , and Mediate ‘s six step process. By reflecting on those and our own problem solving processes, we’ve come up with a sequence of seven problem solving steps we feel best covers everything you need in order to effectively solve problems.

1. Problem identification

The first stage of any problem solving process is to identify the problem or problems you might want to solve. Effective problem solving strategies always begin by allowing a group scope to articulate what they believe the problem to be and then coming to some consensus over which problem they approach first. Problem solving activities used at this stage often have a focus on creating frank, open discussion so that potential problems can be brought to the surface.

2. Problem analysis

Though this step is not a million miles from problem identification, problem analysis deserves to be considered separately. It can often be an overlooked part of the process and is instrumental when it comes to developing effective solutions.

The process of problem analysis means ensuring that the problem you are seeking to solve is the right problem . As part of this stage, you may look deeper and try to find the root cause of a specific problem at a team or organizational level.

Remember that problem solving strategies should not only be focused on putting out fires in the short term but developing long term solutions that deal with the root cause of organizational challenges.

Whatever your approach, analyzing a problem is crucial in being able to select an appropriate solution and the problem solving skills deployed in this stage are beneficial for the rest of the process and ensuring the solutions you create are fit for purpose.

3. Solution generation

Once your group has nailed down the particulars of the problem you wish to solve, you want to encourage a free flow of ideas connecting to solving that problem. This can take the form of problem solving games that encourage creative thinking or problem solving activities designed to produce working prototypes of possible solutions.

The key to ensuring the success of this stage of the problem solving process is to encourage quick, creative thinking and create an open space where all ideas are considered. The best solutions can come from unlikely places and by using problem solving techniques that celebrate invention, you might come up with solution gold.

4. Solution development

No solution is likely to be perfect right out of the gate. It’s important to discuss and develop the solutions your group has come up with over the course of following the previous problem solving steps in order to arrive at the best possible solution. Problem solving games used in this stage involve lots of critical thinking, measuring potential effort and impact, and looking at possible solutions analytically.

During this stage, you will often ask your team to iterate and improve upon your frontrunning solutions and develop them further. Remember that problem solving strategies always benefit from a multitude of voices and opinions, and not to let ego get involved when it comes to choosing which solutions to develop and take further.

Finding the best solution is the goal of all problem solving workshops and here is the place to ensure that your solution is well thought out, sufficiently robust and fit for purpose.

5. Decision making

Nearly there! Once your group has reached consensus and selected a solution that applies to the problem at hand you have some decisions to make. You will want to work on allocating ownership of the project, figure out who will do what, how the success of the solution will be measured and decide the next course of action.

The decision making stage is a part of the problem solving process that can get missed or taken as for granted. Fail to properly allocate roles and plan out how a solution will actually be implemented and it less likely to be successful in solving the problem.

Have clear accountabilities, actions, timeframes, and follow-ups. Make these decisions and set clear next-steps in the problem solving workshop so that everyone is aligned and you can move forward effectively as a group.

Ensuring that you plan for the roll-out of a solution is one of the most important problem solving steps. Without adequate planning or oversight, it can prove impossible to measure success or iterate further if the problem was not solved.

6. Solution implementation

This is what we were waiting for! All problem solving strategies have the end goal of implementing a solution and solving a problem in mind.

Remember that in order for any solution to be successful, you need to help your group through all of the previous problem solving steps thoughtfully. Only then can you ensure that you are solving the right problem but also that you have developed the correct solution and can then successfully implement and measure the impact of that solution.

Project management and communication skills are key here – your solution may need to adjust when out in the wild or you might discover new challenges along the way.

7. Solution evaluation

So you and your team developed a great solution to a problem and have a gut feeling its been solved. Work done, right? Wrong. All problem solving strategies benefit from evaluation, consideration, and feedback. You might find that the solution does not work for everyone, might create new problems, or is potentially so successful that you will want to roll it out to larger teams or as part of other initiatives.

None of that is possible without taking the time to evaluate the success of the solution you developed in your problem solving model and adjust if necessary.

Remember that the problem solving process is often iterative and it can be common to not solve complex issues on the first try. Even when this is the case, you and your team will have generated learning that will be important for future problem solving workshops or in other parts of the organization.

It’s worth underlining how important record keeping is throughout the problem solving process. If a solution didn’t work, you need to have the data and records to see why that was the case. If you go back to the drawing board, notes from the previous workshop can help save time. Data and insight is invaluable at every stage of the problem solving process and this one is no different.

Problem solving workshops made easy

Problem solving strategies are methods of approaching and facilitating the process of problem-solving with a set of techniques , actions, and processes. Different strategies are more effective if you are trying to solve broad problems such as achieving higher growth versus more focused problems like, how do we improve our customer onboarding process?

Broadly, the problem solving steps outlined above should be included in any problem solving strategy though choosing where to focus your time and what approaches should be taken is where they begin to differ. You might find that some strategies ask for the problem identification to be done prior to the session or that everything happens in the course of a one day workshop.

The key similarity is that all good problem solving strategies are structured and designed. Four hours of open discussion is never going to be as productive as a four-hour workshop designed to lead a group through a problem solving process.

Good problem solving strategies are tailored to the team, organization and problem you will be attempting to solve. Here are some example problem solving strategies you can learn from or use to get started.

Use a workshop to lead a team through a group process

Often, the first step to solving problems or organizational challenges is bringing a group together effectively. Most teams have the tools, knowledge, and expertise necessary to solve their challenges – they just need some guidance in how to use leverage those skills and a structure and format that allows people to focus their energies.

Facilitated workshops are one of the most effective ways of solving problems of any scale. By designing and planning your workshop carefully, you can tailor the approach and scope to best fit the needs of your team and organization.

Problem solving workshop

- Creating a bespoke, tailored process

- Tackling problems of any size

- Building in-house workshop ability and encouraging their use

Workshops are an effective strategy for solving problems. By using tried and test facilitation techniques and methods, you can design and deliver a workshop that is perfectly suited to the unique variables of your organization. You may only have the capacity for a half-day workshop and so need a problem solving process to match.

By using our session planner tool and importing methods from our library of 700+ facilitation techniques, you can create the right problem solving workshop for your team. It might be that you want to encourage creative thinking or look at things from a new angle to unblock your groups approach to problem solving. By tailoring your workshop design to the purpose, you can help ensure great results.

One of the main benefits of a workshop is the structured approach to problem solving. Not only does this mean that the workshop itself will be successful, but many of the methods and techniques will help your team improve their working processes outside of the workshop.

We believe that workshops are one of the best tools you can use to improve the way your team works together. Start with a problem solving workshop and then see what team building, culture or design workshops can do for your organization!

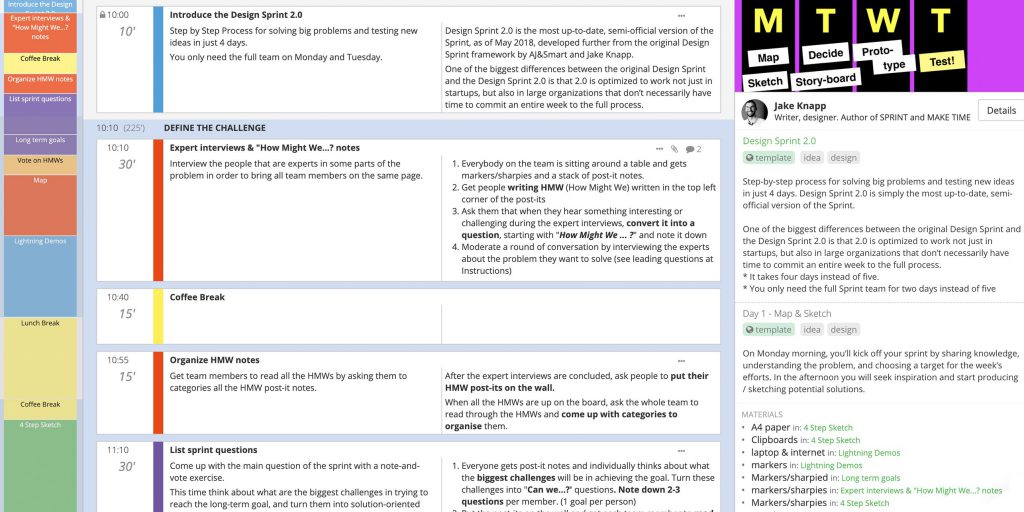

Run a design sprint

Great for:

- aligning large, multi-discipline teams

- quickly designing and testing solutions

- tackling large, complex organizational challenges and breaking them down into smaller tasks

By using design thinking principles and methods, a design sprint is a great way of identifying, prioritizing and prototyping solutions to long term challenges that can help solve major organizational problems with quick action and measurable results.

Some familiarity with design thinking is useful, though not integral, and this strategy can really help a team align if there is some discussion around which problems should be approached first.

The stage-based structure of the design sprint is also very useful for teams new to design thinking. The inspiration phase, where you look to competitors that have solved your problem, and the rapid prototyping and testing phases are great for introducing new concepts that will benefit a team in all their future work.

It can be common for teams to look inward for solutions and so looking to the market for solutions you can iterate on can be very productive. Instilling an agile prototyping and testing mindset can also be great when helping teams move forwards – generating and testing solutions quickly can help save time in the long run and is also pretty exciting!

Break problems down into smaller issues

Organizational challenges and problems are often complicated and large scale in nature. Sometimes, trying to resolve such an issue in one swoop is simply unachievable or overwhelming. Try breaking down such problems into smaller issues that you can work on step by step. You may not be able to solve the problem of churning customers off the bat, but you can work with your team to identify smaller effort but high impact elements and work on those first.

This problem solving strategy can help a team generate momentum, prioritize and get some easy wins. It’s also a great strategy to employ with teams who are just beginning to learn how to approach the problem solving process. If you want some insight into a way to employ this strategy, we recommend looking at our design sprint template below!

Use guiding frameworks or try new methodologies

Some problems are best solved by introducing a major shift in perspective or by using new methodologies that encourage your team to think differently.

Props and tools such as Methodkit , which uses a card-based toolkit for facilitation, or Lego Serious Play can be great ways to engage your team and find an inclusive, democratic problem solving strategy. Remember that play and creativity are great tools for achieving change and whatever the challenge, engaging your participants can be very effective where other strategies may have failed.

LEGO Serious Play

- Improving core problem solving skills

- Thinking outside of the box

- Encouraging creative solutions

LEGO Serious Play is a problem solving methodology designed to get participants thinking differently by using 3D models and kinesthetic learning styles. By physically building LEGO models based on questions and exercises, participants are encouraged to think outside of the box and create their own responses.

Collaborate LEGO Serious Play exercises are also used to encourage communication and build problem solving skills in a group. By using this problem solving process, you can often help different kinds of learners and personality types contribute and unblock organizational problems with creative thinking.

Problem solving strategies like LEGO Serious Play are super effective at helping a team solve more skills-based problems such as communication between teams or a lack of creative thinking. Some problems are not suited to LEGO Serious Play and require a different problem solving strategy.

Card Decks and Method Kits

- New facilitators or non-facilitators

- Approaching difficult subjects with a simple, creative framework

- Engaging those with varied learning styles

Card decks and method kids are great tools for those new to facilitation or for whom facilitation is not the primary role. Card decks such as the emotional culture deck can be used for complete workshops and in many cases, can be used right out of the box. Methodkit has a variety of kits designed for scenarios ranging from personal development through to personas and global challenges so you can find the right deck for your particular needs.

Having an easy to use framework that encourages creativity or a new approach can take some of the friction or planning difficulties out of the workshop process and energize a team in any setting. Simplicity is the key with these methods. By ensuring everyone on your team can get involved and engage with the process as quickly as possible can really contribute to the success of your problem solving strategy.

Source external advice

Looking to peers, experts and external facilitators can be a great way of approaching the problem solving process. Your team may not have the necessary expertise, insights of experience to tackle some issues, or you might simply benefit from a fresh perspective. Some problems may require bringing together an entire team, and coaching managers or team members individually might be the right approach. Remember that not all problems are best resolved in the same manner.

If you’re a solo entrepreneur, peer groups, coaches and mentors can also be invaluable at not only solving specific business problems, but in providing a support network for resolving future challenges. One great approach is to join a Mastermind Group and link up with like-minded individuals and all grow together. Remember that however you approach the sourcing of external advice, do so thoughtfully, respectfully and honestly. Reciprocate where you can and prepare to be surprised by just how kind and helpful your peers can be!

Mastermind Group

- Solo entrepreneurs or small teams with low capacity

- Peer learning and gaining outside expertise

- Getting multiple external points of view quickly

Problem solving in large organizations with lots of skilled team members is one thing, but how about if you work for yourself or in a very small team without the capacity to get the most from a design sprint or LEGO Serious Play session?

A mastermind group – sometimes known as a peer advisory board – is where a group of people come together to support one another in their own goals, challenges, and businesses. Each participant comes to the group with their own purpose and the other members of the group will help them create solutions, brainstorm ideas, and support one another.

Mastermind groups are very effective in creating an energized, supportive atmosphere that can deliver meaningful results. Learning from peers from outside of your organization or industry can really help unlock new ways of thinking and drive growth. Access to the experience and skills of your peers can be invaluable in helping fill the gaps in your own ability, particularly in young companies.

A mastermind group is a great solution for solo entrepreneurs, small teams, or for organizations that feel that external expertise or fresh perspectives will be beneficial for them. It is worth noting that Mastermind groups are often only as good as the participants and what they can bring to the group. Participants need to be committed, engaged and understand how to work in this context.

Coaching and mentoring

- Focused learning and development

- Filling skills gaps

- Working on a range of challenges over time

Receiving advice from a business coach or building a mentor/mentee relationship can be an effective way of resolving certain challenges. The one-to-one format of most coaching and mentor relationships can really help solve the challenges those individuals are having and benefit the organization as a result.

A great mentor can be invaluable when it comes to spotting potential problems before they arise and coming to understand a mentee very well has a host of other business benefits. You might run an internal mentorship program to help develop your team’s problem solving skills and strategies or as part of a large learning and development program. External coaches can also be an important part of your problem solving strategy, filling skills gaps for your management team or helping with specific business issues.

Now we’ve explored the problem solving process and the steps you will want to go through in order to have an effective session, let’s look at the skills you and your team need to be more effective problem solvers.

Problem solving skills are highly sought after, whatever industry or team you work in. Organizations are keen to employ people who are able to approach problems thoughtfully and find strong, realistic solutions. Whether you are a facilitator , a team leader or a developer, being an effective problem solver is a skill you’ll want to develop.

Problem solving skills form a whole suite of techniques and approaches that an individual uses to not only identify problems but to discuss them productively before then developing appropriate solutions.

Here are some of the most important problem solving skills everyone from executives to junior staff members should learn. We’ve also included an activity or exercise from the SessionLab library that can help you and your team develop that skill.

If you’re running a workshop or training session to try and improve problem solving skills in your team, try using these methods to supercharge your process!

Active listening

Active listening is one of the most important skills anyone who works with people can possess. In short, active listening is a technique used to not only better understand what is being said by an individual, but also to be more aware of the underlying message the speaker is trying to convey. When it comes to problem solving, active listening is integral for understanding the position of every participant and to clarify the challenges, ideas and solutions they bring to the table.

Some active listening skills include:

- Paying complete attention to the speaker.

- Removing distractions.

- Avoid interruption.

- Taking the time to fully understand before preparing a rebuttal.

- Responding respectfully and appropriately.

- Demonstrate attentiveness and positivity with an open posture, making eye contact with the speaker, smiling and nodding if appropriate. Show that you are listening and encourage them to continue.

- Be aware of and respectful of feelings. Judge the situation and respond appropriately. You can disagree without being disrespectful.

- Observe body language.

- Paraphrase what was said in your own words, either mentally or verbally.

- Remain neutral.

- Reflect and take a moment before responding.

- Ask deeper questions based on what is said and clarify points where necessary.

Active Listening #hyperisland #skills #active listening #remote-friendly This activity supports participants to reflect on a question and generate their own solutions using simple principles of active listening and peer coaching. It’s an excellent introduction to active listening but can also be used with groups that are already familiar with it. Participants work in groups of three and take turns being: “the subject”, the listener, and the observer.

Analytical skills

All problem solving models require strong analytical skills, particularly during the beginning of the process and when it comes to analyzing how solutions have performed.

Analytical skills are primarily focused on performing an effective analysis by collecting, studying and parsing data related to a problem or opportunity.

It often involves spotting patterns, being able to see things from different perspectives and using observable facts and data to make suggestions or produce insight.

Analytical skills are also important at every stage of the problem solving process and by having these skills, you can ensure that any ideas or solutions you create or backed up analytically and have been sufficiently thought out.

Nine Whys #innovation #issue analysis #liberating structures With breathtaking simplicity, you can rapidly clarify for individuals and a group what is essentially important in their work. You can quickly reveal when a compelling purpose is missing in a gathering and avoid moving forward without clarity. When a group discovers an unambiguous shared purpose, more freedom and more responsibility are unleashed. You have laid the foundation for spreading and scaling innovations with fidelity.

Collaboration

Trying to solve problems on your own is difficult. Being able to collaborate effectively, with a free exchange of ideas, to delegate and be a productive member of a team is hugely important to all problem solving strategies.

Remember that whatever your role, collaboration is integral, and in a problem solving process, you are all working together to find the best solution for everyone.

Marshmallow challenge with debriefing #teamwork #team #leadership #collaboration In eighteen minutes, teams must build the tallest free-standing structure out of 20 sticks of spaghetti, one yard of tape, one yard of string, and one marshmallow. The marshmallow needs to be on top. The Marshmallow Challenge was developed by Tom Wujec, who has done the activity with hundreds of groups around the world. Visit the Marshmallow Challenge website for more information. This version has an extra debriefing question added with sample questions focusing on roles within the team.

Communication

Being an effective communicator means being empathetic, clear and succinct, asking the right questions, and demonstrating active listening skills throughout any discussion or meeting.

In a problem solving setting, you need to communicate well in order to progress through each stage of the process effectively. As a team leader, it may also fall to you to facilitate communication between parties who may not see eye to eye. Effective communication also means helping others to express themselves and be heard in a group.

Bus Trip #feedback #communication #appreciation #closing #thiagi #team This is one of my favourite feedback games. I use Bus Trip at the end of a training session or a meeting, and I use it all the time. The game creates a massive amount of energy with lots of smiles, laughs, and sometimes even a teardrop or two.

Creative problem solving skills can be some of the best tools in your arsenal. Thinking creatively, being able to generate lots of ideas and come up with out of the box solutions is useful at every step of the process.

The kinds of problems you will likely discuss in a problem solving workshop are often difficult to solve, and by approaching things in a fresh, creative manner, you can often create more innovative solutions.

Having practical creative skills is also a boon when it comes to problem solving. If you can help create quality design sketches and prototypes in record time, it can help bring a team to alignment more quickly or provide a base for further iteration.

The paper clip method #sharing #creativity #warm up #idea generation #brainstorming The power of brainstorming. A training for project leaders, creativity training, and to catalyse getting new solutions.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking is one of the fundamental problem solving skills you’ll want to develop when working on developing solutions. Critical thinking is the ability to analyze, rationalize and evaluate while being aware of personal bias, outlying factors and remaining open-minded.

Defining and analyzing problems without deploying critical thinking skills can mean you and your team go down the wrong path. Developing solutions to complex issues requires critical thinking too – ensuring your team considers all possibilities and rationally evaluating them.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix #issue analysis #liberating structures #problem solving You can help individuals or groups avoid the frequent mistake of trying to solve a problem with methods that are not adapted to the nature of their challenge. The combination of two questions makes it possible to easily sort challenges into four categories: simple, complicated, complex , and chaotic . A problem is simple when it can be solved reliably with practices that are easy to duplicate. It is complicated when experts are required to devise a sophisticated solution that will yield the desired results predictably. A problem is complex when there are several valid ways to proceed but outcomes are not predictable in detail. Chaotic is when the context is too turbulent to identify a path forward. A loose analogy may be used to describe these differences: simple is like following a recipe, complicated like sending a rocket to the moon, complex like raising a child, and chaotic is like the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.” The Liberating Structures Matching Matrix in Chapter 5 can be used as the first step to clarify the nature of a challenge and avoid the mismatches between problems and solutions that are frequently at the root of chronic, recurring problems.

Data analysis

Though it shares lots of space with general analytical skills, data analysis skills are something you want to cultivate in their own right in order to be an effective problem solver.

Being good at data analysis doesn’t just mean being able to find insights from data, but also selecting the appropriate data for a given issue, interpreting it effectively and knowing how to model and present that data. Depending on the problem at hand, it might also include a working knowledge of specific data analysis tools and procedures.

Having a solid grasp of data analysis techniques is useful if you’re leading a problem solving workshop but if you’re not an expert, don’t worry. Bring people into the group who has this skill set and help your team be more effective as a result.

Decision making

All problems need a solution and all solutions require that someone make the decision to implement them. Without strong decision making skills, teams can become bogged down in discussion and less effective as a result.

Making decisions is a key part of the problem solving process. It’s important to remember that decision making is not restricted to the leadership team. Every staff member makes decisions every day and developing these skills ensures that your team is able to solve problems at any scale. Remember that making decisions does not mean leaping to the first solution but weighing up the options and coming to an informed, well thought out solution to any given problem that works for the whole team.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly The problem with anything that requires creative thinking is that it’s easy to get lost—lose focus and fall into the trap of having useless, open-ended, unstructured discussions. Here’s the most effective solution I’ve found: Replace all open, unstructured discussion with a clear process. What to use this exercise for: Anything which requires a group of people to make decisions, solve problems or discuss challenges. It’s always good to frame an LDJ session with a broad topic, here are some examples: The conversion flow of our checkout Our internal design process How we organise events Keeping up with our competition Improving sales flow

Dependability

Most complex organizational problems require multiple people to be involved in delivering the solution. Ensuring that the team and organization can depend on you to take the necessary actions and communicate where necessary is key to ensuring problems are solved effectively.

Being dependable also means working to deadlines and to brief. It is often a matter of creating trust in a team so that everyone can depend on one another to complete the agreed actions in the agreed time frame so that the team can move forward together. Being undependable can create problems of friction and can limit the effectiveness of your solutions so be sure to bear this in mind throughout a project.

Team Purpose & Culture #team #hyperisland #culture #remote-friendly This is an essential process designed to help teams define their purpose (why they exist) and their culture (how they work together to achieve that purpose). Defining these two things will help any team to be more focused and aligned. With support of tangible examples from other companies, the team members work as individuals and a group to codify the way they work together. The goal is a visual manifestation of both the purpose and culture that can be put up in the team’s work space.

Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence is an important skill for any successful team member, whether communicating internally or with clients or users. In the problem solving process, emotional intelligence means being attuned to how people are feeling and thinking, communicating effectively and being self-aware of what you bring to a room.

There are often differences of opinion when working through problem solving processes, and it can be easy to let things become impassioned or combative. Developing your emotional intelligence means being empathetic to your colleagues and managing your own emotions throughout the problem and solution process. Be kind, be thoughtful and put your points across care and attention.

Being emotionally intelligent is a skill for life and by deploying it at work, you can not only work efficiently but empathetically. Check out the emotional culture workshop template for more!

Facilitation

As we’ve clarified in our facilitation skills post, facilitation is the art of leading people through processes towards agreed-upon objectives in a manner that encourages participation, ownership, and creativity by all those involved. While facilitation is a set of interrelated skills in itself, the broad definition of facilitation can be invaluable when it comes to problem solving. Leading a team through a problem solving process is made more effective if you improve and utilize facilitation skills – whether you’re a manager, team leader or external stakeholder.

The Six Thinking Hats #creative thinking #meeting facilitation #problem solving #issue resolution #idea generation #conflict resolution The Six Thinking Hats are used by individuals and groups to separate out conflicting styles of thinking. They enable and encourage a group of people to think constructively together in exploring and implementing change, rather than using argument to fight over who is right and who is wrong.

Flexibility

Being flexible is a vital skill when it comes to problem solving. This does not mean immediately bowing to pressure or changing your opinion quickly: instead, being flexible is all about seeing things from new perspectives, receiving new information and factoring it into your thought process.

Flexibility is also important when it comes to rolling out solutions. It might be that other organizational projects have greater priority or require the same resources as your chosen solution. Being flexible means understanding needs and challenges across the team and being open to shifting or arranging your own schedule as necessary. Again, this does not mean immediately making way for other projects. It’s about articulating your own needs, understanding the needs of others and being able to come to a meaningful compromise.

The Creativity Dice #creativity #problem solving #thiagi #issue analysis Too much linear thinking is hazardous to creative problem solving. To be creative, you should approach the problem (or the opportunity) from different points of view. You should leave a thought hanging in mid-air and move to another. This skipping around prevents premature closure and lets your brain incubate one line of thought while you consciously pursue another.

Working in any group can lead to unconscious elements of groupthink or situations in which you may not wish to be entirely honest. Disagreeing with the opinions of the executive team or wishing to save the feelings of a coworker can be tricky to navigate, but being honest is absolutely vital when to comes to developing effective solutions and ensuring your voice is heard.

Remember that being honest does not mean being brutally candid. You can deliver your honest feedback and opinions thoughtfully and without creating friction by using other skills such as emotional intelligence.

Explore your Values #hyperisland #skills #values #remote-friendly Your Values is an exercise for participants to explore what their most important values are. It’s done in an intuitive and rapid way to encourage participants to follow their intuitive feeling rather than over-thinking and finding the “correct” values. It is a good exercise to use to initiate reflection and dialogue around personal values.

Initiative