Introduction to qualitative nursing research

This type of research can reveal important information that quantitative research can’t.

- Qualitative research is valuable because it approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, about which little is known by trying to understand its many facets.

- Most qualitative research is emergent, holistic, detailed, and uses many strategies to collect data.

- Qualitative research generates evidence and helps nurses determine patient preferences.

Research 101: Descriptive statistics

Differentiating research, evidence-based practice, and quality improvement

How to appraise quantitative research articles

All nurses are expected to understand and apply evidence to their professional practice. Some of the evidence should be in the form of research, which fills gaps in knowledge, developing and expanding on current understanding. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods inform nursing practice, but quantitative research tends to be more emphasized. In addition, many nurses don’t feel comfortable conducting or evaluating qualitative research. But once you understand qualitative research, you can more easily apply it to your nursing practice.

What is qualitative research?

Defining qualitative research can be challenging. In fact, some authors suggest that providing a simple definition is contrary to the method’s philosophy. Qualitative research approaches a phenomenon, such as a clinical problem, from a place of unknowing and attempts to understand its many facets. This makes qualitative research particularly useful when little is known about a phenomenon because the research helps identify key concepts and constructs. Qualitative research sets the foundation for future quantitative or qualitative research. Qualitative research also can stand alone without quantitative research.

Although qualitative research is diverse, certain characteristics—holism, subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and situated contexts—guide its methodology. This type of research stresses the importance of studying each individual as a holistic system (holism) influenced by surroundings (situated contexts); each person develops his or her own subjective world (subjectivity) that’s influenced by interactions with others (intersubjectivity) and surroundings (situated contexts). Think of it this way: Each person experiences and interprets the world differently based on many factors, including his or her history and interactions. The truth is a composite of realities.

Qualitative research designs

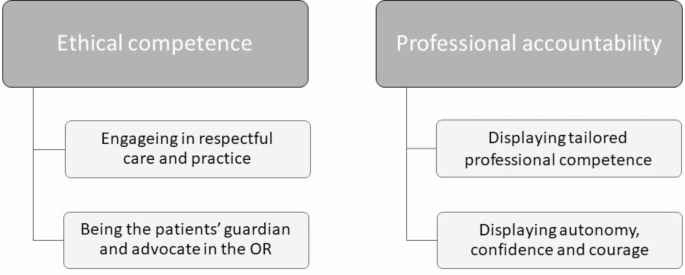

Because qualitative research explores diverse topics and examines phenomena where little is known, designs and methodologies vary. Despite this variation, most qualitative research designs are emergent and holistic. In addition, they require merging data collection strategies and an intensely involved researcher. (See Research design characteristics .)

Although qualitative research designs are emergent, advanced planning and careful consideration should include identifying a phenomenon of interest, selecting a research design, indicating broad data collection strategies and opportunities to enhance study quality, and considering and/or setting aside (bracketing) personal biases, views, and assumptions.

Many qualitative research designs are used in nursing. Most originated in other disciplines, while some claim no link to a particular disciplinary tradition. Designs that aren’t linked to a discipline, such as descriptive designs, may borrow techniques from other methodologies; some authors don’t consider them to be rigorous (high-quality and trustworthy). (See Common qualitative research designs .)

Sampling approaches

Sampling approaches depend on the qualitative research design selected. However, in general, qualitative samples are small, nonrandom, emergently selected, and intensely studied. Qualitative research sampling is concerned with accurately representing and discovering meaning in experience, rather than generalizability. For this reason, researchers tend to look for participants or informants who are considered “information rich” because they maximize understanding by representing varying demographics and/or ranges of experiences. As a study progresses, researchers look for participants who confirm, challenge, modify, or enrich understanding of the phenomenon of interest. Many authors argue that the concepts and constructs discovered in qualitative research transcend a particular study, however, and find applicability to others. For example, consider a qualitative study about the lived experience of minority nursing faculty and the incivility they endure. The concepts learned in this study may transcend nursing or minority faculty members and also apply to other populations, such as foreign-born students, nurses, or faculty.

Qualitative nursing research can take many forms. The design you choose will depend on the question you’re trying to answer.

| Action research | Education | Conducted by and for those taking action to improve or refine actions | What happens to the quality of nursing practice when we implement a peer-mentoring system? |

| Case study | Many | In-depth analysis of an entity or group of entities (case) | How is patient autonomy promoted by a unit? |

| Descriptive | N/A | Content analysis of data | |

| Discourse analysis | Many | In-depth analysis of written, vocal, or sign language | What discourses are used in nursing practice and how do they shape practice? |

| Ethnography | Anthropology | In-depth analysis of a culture | How does Filipino culture influence childbirth experiences? |

| Ethology | Psychology | Biology of human behavior and events | What are the immediate underlying psychological and environmental causes of incivility in nursing? |

| Grounded theory | Sociology | Social processes within a social setting | How does the basic social process of role transition happen within the context of advanced practice nursing transitions? |

| Historical research | History | Past behaviors, events, conditions | When did nurses become researchers? |

| Narrative inquiry | Many | Story as the object of inquiry | How does one live with a diagnosis of scleroderma? |

| Phenomenology | Philosophy Psychology | Lived experiences | What is the lived experience of nurses who were admitted as patients on their home practice unit? |

A sample size is estimated before a qualitative study begins, but the final sample size depends on the study scope, data quality, sensitivity of the research topic or phenomenon of interest, and researchers’ skills. For example, a study with a narrow scope, skilled researchers, and a nonsensitive topic likely will require a smaller sample. Data saturation frequently is a key consideration in final sample size. When no new insights or information are obtained, data saturation is attained and sampling stops, although researchers may analyze one or two more cases to be certain. (See Sampling types .)

Some controversy exists around the concept of saturation in qualitative nursing research. Thorne argues that saturation is a concept appropriate for grounded theory studies and not other study types. She suggests that “information power” is perhaps more appropriate terminology for qualitative nursing research sampling and sample size.

Data collection and analysis

Researchers are guided by their study design when choosing data collection and analysis methods. Common types of data collection include interviews (unstructured, semistructured, focus groups); observations of people, environments, or contexts; documents; records; artifacts; photographs; or journals. When collecting data, researchers must be mindful of gaining participant trust while also guarding against too much emotional involvement, ensuring comprehensive data collection and analysis, conducting appropriate data management, and engaging in reflexivity.

Data usually are recorded in detailed notes, memos, and audio or visual recordings, which frequently are transcribed verbatim and analyzed manually or using software programs, such as ATLAS.ti, HyperRESEARCH, MAXQDA, or NVivo. Analyzing qualitative data is complex work. Researchers act as reductionists, distilling enormous amounts of data into concise yet rich and valuable knowledge. They code or identify themes, translating abstract ideas into meaningful information. The good news is that qualitative research typically is easy to understand because it’s reported in stories told in everyday language.

Evaluating a qualitative study

Evaluating qualitative research studies can be challenging. Many terms—rigor, validity, integrity, and trustworthiness—can describe study quality, but in the end you want to know whether the study’s findings accurately and comprehensively represent the phenomenon of interest. Many researchers identify a quality framework when discussing quality-enhancement strategies. Example frameworks include:

- Trustworthiness criteria framework, which enhances credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity

- Validity in qualitative research framework, which enhances credibility, authenticity, criticality, integrity, explicitness, vividness, creativity, thoroughness, congruence, and sensitivity.

With all frameworks, many strategies can be used to help meet identified criteria and enhance quality. (See Research quality enhancement ). And considering the study as a whole is important to evaluating its quality and rigor. For example, when looking for evidence of rigor, look for a clear and concise report title that describes the research topic and design and an abstract that summarizes key points (background, purpose, methods, results, conclusions).

Application to nursing practice

Qualitative research not only generates evidence but also can help nurses determine patient preferences. Without qualitative research, we can’t truly understand others, including their interpretations, meanings, needs, and wants. Qualitative research isn’t generalizable in the traditional sense, but it helps nurses open their minds to others’ experiences. For example, nurses can protect patient autonomy by understanding them and not reducing them to universal protocols or plans. As Munhall states, “Each person we encounter help[s] us discover what is best for [him or her]. The other person, not us, is truly the expert knower of [him- or herself].” Qualitative nursing research helps us understand the complexity and many facets of a problem and gives us insights as we encourage others’ voices and searches for meaning.

When paired with clinical judgment and other evidence, qualitative research helps us implement evidence-based practice successfully. For example, a phenomenological inquiry into the lived experience of disaster workers might help expose strengths and weaknesses of individuals, populations, and systems, providing areas of focused intervention. Or a phenomenological study of the lived experience of critical-care patients might expose factors (such dark rooms or no visible clocks) that contribute to delirium.

Successful implementation

Qualitative nursing research guides understanding in practice and sets the foundation for future quantitative and qualitative research. Knowing how to conduct and evaluate qualitative research can help nurses implement evidence-based practice successfully.

When evaluating a qualitative study, you should consider it as a whole. The following questions to consider when examining study quality and evidence of rigor are adapted from the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.

| o What is the report title and composition of the abstract? o What is the problem and/or phenomenon of interest and study significance? o What is the purpose of the study and/or research question? | → Clear and concise report title describes the research topic and design (e.g., grounded theory) or data collection methods (e.g., interviews) → Abstract summarizes key points including background, purpose, methods, results, and conclusions → Problem and/or phenomenon of interest and significance is identified and well described, with a thorough review of relevant theories and/or other research → Study purpose and/or research question is identified and appropriate to the problem and/or phenomenon of interest and significance |

| o What design and/or research paradigm was used? o Is there evidence of researcher reflexivity? o What is the setting and context for the study? o What is the sampling approach? How and why were data selected? Why was sampling stopped? o Was institutional review board (IRB) approval obtained and were other issues relating to protection of human subjects outlined? | → Design (e.g., phenomenology, ethnography), research paradigm (e.g., constructivist), and guiding theory or model, as appropriate, are identified, along with well-described rationales → Design is appropriate to research problem and/or phenomenon of interest → Researcher characteristics that may influence the study are identified and well described, as well as methods to protect against these influences (e.g., journaling, bracketing) → Settings, sites, and contexts are identified and well described, along with well-described rationales |

| o What data collection and analysis instruments and/or technologies were used? o What is the method for data processing and analysis? o What is the composition of the data? o What strategies were used to enhance quality and trustworthiness? | → Sampling approach and how and why data were selected are identified and well described, along with well-described rationales; participant inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined and appropriate → Criteria for deciding when sampling stops is outlined (e.g., saturation) and rationale is provided and appropriate → Documentation of IRB approval or explanation of lack thereof provided; consent, confidentiality, data security, and other protection of human subject issues are well described and thorough → Description of instruments (e.g., interview scripts, observation logs) and technologies (e.g., audio-recorders) used is provided, including how instruments were developed; description of if and how these changed during the study is given, along with well-described rationales → Types of data collected, details of data collection, analysis, and other processing procedures are well described and thorough, along with well-described rationales → Number and characteristics of participants and/or other data are described and appropriate → Strategies to enhance quality and trustworthiness (e.g., member checking) are identified, comprehensive, and appropriate, along with well-described rationales; trustworthiness framework, if identified, is established from experts (e.g., Lincoln and Guba, Whittemore et al.) and strategies are appropriate to this framework |

| o Were main study results synthesized and interpreted? If applicable, were they developed into a theory or integrated with prior research? o Were results linked to empirical data? | → Main results (e.g., themes) are presented and well described and a theory or model is developed and described, if applicable; results are integrated with prior research → Adequate evidence (e.g., direct quotes from interviews, field notes) is provided to support main study results |

| o Are study results described in relation to prior work? o Are study implications, applicability, and contributions to nursing identified? o Are study limitations outlined? | → Concise summary of main results are provided and thorough, including relation to prior works (e.g., connection, support, elaboration, challenging prior conclusions) → Thorough discussion of study implications, applicability, and unique contributions to nursing is provided → Study limitations are described thoroughly and future improvements and/or research topics are suggested |

| o Are potential or perceived conflicts of interest identified and how were these managed? o If applicable, what sources of funding or other support did the study receive? | → All potential or perceived conflicts of interest are identified and well described; methods to manage potential or perceived conflicts of interest are identified and appear to protect study integrity → All sources of funding and other support are identified and well described, along with the roles the funders and support played in study efforts; they do not appear to interfere with study integrity |

Jennifer Chicca is a PhD candidate at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and a part-time faculty member at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

Amankwaa L. Creating protocols for trustworthiness in qualitative research. J Cult Divers. 2016;23(3):121-7.

Cuthbert CA, Moules N. The application of qualitative research findings to oncology nursing practice. Oncol Nurs Forum . 2014;41(6):683-5.

Guba E, Lincoln Y. Competing paradigms in qualitative research . In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.;1994: 105-17.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1985.

Munhall PL. Nursing Research: A Qualitative Perspective . 5th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2012.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 1: Philosophies. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(1):26-33.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 2: Methodology. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(2):71-7.

Nicholls D. Qualitative research. Part 3: Methods. Int J Ther Rehabil . 2017;24(3):114-21.

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med . 2014;89(9):1245-51.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice . 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

Thorne S. Saturation in qualitative nursing studies: Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Auth Ed. 2020;30(1):5. naepub.com/reporting-research/2020-30-1-5

Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res . 2001;11(4):522-37.

Williams B. Understanding qualitative research. Am Nurse Today . 2015;10(7):40-2.

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Increasing diversity in nursing with support from Nurses on Boards Coalition

Adventures in lifelong learning

The power of language

Making peace with imperfection

When laws and nursing ethics collide

Taking on health disparities

Medication safety and pediatric health

Confidence is in

Tailored falls prevention plans

Men in nursing

FAQs: AI and prompt engineering

Caring for adults with autism spectrum disorder

Known fallers

Florence Nightingale overcame the limits set on proper Victorian women – and brought modern science and statistics to nursing

Bird flu is bad for poultry and dairy cows. It’s not a dire threat for most of us — yet.

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Qualitative Research

The “what,” “why,” “who,” and “how”.

Cypress, Brigitte S. EdD, RN, CCRN

Brigitte S. Cypress, EdD, RN, CCRN, is assistant professor at Lehman College and The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

The author has disclosed that she has no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Brigitte S. Cypress, EdD, RN, CCRN, PO Box 2205, Pocono Summit, PA 18346 ( [email protected] ).

There has been a general view of qualitative research as a lower level form of inquiry and the diverse conceptualizations of what it is, its use or utility, its users, the process of how it is conducted, and its scientific merit. This fragmented understanding and varied ways in which qualitative research is conceived, synthesized, and presented have a myriad of implications in demonstrating and enhancing the utilization of its findings and the ways and skills required in transforming knowledge gained from it. The purpose of this article is to define qualitative research and discuss its significance in research, the questions it addresses, its characteristics, methods and criteria for rigor, and the type of results it can offer. A framework for understanding the “what,” “why,” “who,” and “how” of qualitative research; the different approaches; and the strategies to achieve trustworthiness are presented. Qualitative research provides insights into health-related phenomena and seeks to understand and interpret subjective experience and thus humanizes health care and can enrich further research inquiries and be made clearer and more rigorous as it is relevant to the perspective and goals of nursing.

Qualitative research methods began to appear in nursing in 1960s and 1970s amid cautious and reluctant acceptance. In the 1980s, qualitative health research emerged as a distinctive domain and mode of inquiry. 1 Qualitative research refers to any kind of research that produces findings not arrived at by means of statistical analysis or other means of quantification. 2,3 It uses a naturalistic approach that seeks to understand phenomena about persons’ lives, stories, and behavior including those related to health, organizational functioning, social movements, or interactional relationships. Qualitative research is underpinned by several theoretical perspectives, namely, constructivist-interpretive, critical, postpositivist, poststructural/postmodern, and feminism. 4 One conducts a qualitative study to uncover the nature of the person’s experiences with a phenomenon in context-specific conditions such as illness (acute and chronic), addiction, loss, disability, and end of life. Qualitative research is used to explore, uncover, describe, and understand what lies behind any phenomenon about which maybe little is known. This deeper understanding of the phenomenon in its specific context can be attained only through a qualitative inquiry than mere numbers and statistical models could provide using a quantitative approach. Qualitative inquiry represents a legitimate mode of social and human science exploration, without apology or comparisons to quantitative research. 5

This article describes what is qualitative research methodology, the “what,” “why,” “who,” and “how,” including its components. The aim is to simplify the terminology and process of qualitative inquiry to enable novice readers of research to better understand the concepts involved.

WHY DO QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

The tradition of using qualitative methods to study human phenomena is grounded in the social sciences. 6 This methodological revolution has made way for a more interpretative approach because aspects of human values, culture, and relationships are not described fully using quantitative research methods. Unlike quantitative researchers who seek causal determination, prediction, and generalization of findings, qualitative researchers allow for the phenomenon of interest to unfold naturally, 7 strive to explore, describe and understand it, and delve into a colorful, deep, contextual world of interpretations. 8 Thus, the practice of qualitative research has expanded to clinical settings because empirical approaches have proven to be inadequate in answering questions related to human subjectivity where interpretation is involved. 9 Consequently, qualitative health research is a research approach to exploring health and illness as they are perceived by the people themselves rather than from the researcher’s perspective. 10 Morse 10 further stated that “Researchers use qualitative research methods to illicit emotions and perspectives, beliefs and values, actions, and behaviors and to understand the participant’s responses to health and illness and the meanings they construct about the experience.” 10 (p21) It provides a rich inductive description that necessitates interpretations. Researchers in the health care arena, practitioners, and policy makers are increasingly pressed to translate these findings for practice, put them to use, and evaluate how useful they actually are in effecting desired change with goal of improving public health and reducing disparities in health care delivery. 1 Even though qualitative research has been used for many decades, and it is in fact flourishing, it is not free of criticisms from experts with impoverished view of the methodology.

Despite the current urgency of the utilization of qualitative methodologies in research studies, questions are raised for its lack of objectivity, generalizability, utility, and its tendency to be anecdotal. 1 Critics continue to make these charges related to their limited understanding of qualitative designs, approaches, and methods. Sandelowski 1 asserted that the current urgency about the utility of qualitative research findings is the result of several converging trends in health care research that include the elevation of practical over basic knowledge as the highest form of knowledge, the proliferation of qualitative health research studies, and the rise of evidence-based practice as a paradigm and methodology for health care. 1 Consequently, these events have, in turn, contributed to the growing interest of incorporating qualitative health research findings into evidence-based practice.

Morse 10 asserted that there are other reasons for conducting a qualitative inquiry. Others believe that the role of qualitative inquiry is to provide hypothesis and research questions that can be posed from the findings of qualitative research studies. Qualitative research can also serve as a foundation from which surveys and questionnaires could be developed, thus increasing its validity that would produce models for quantitative testing. But, what is really the most important function of qualitative inquiry? According to Morse, 10 this key function is the moral imperative of qualitative inquiry to humanize health care. She stated, “The social justice agenda of qualitative health research is one that humanizes health care.” 10 (p52) So, what is humanizing health care? Morse 10 stated, “Humanizing encompasses a perspective on attitudes, beliefs, expectations, practices, and behaviors that influence the quality of care, administration of that care, conditions judged to warrant (or not warrant) empathetic care, responses to care and therapeutics, and anticipated and actual outcomes of patient or community care.” 10 (pp54,55)

Conducting research should be sort of a social justice project. 10 Denzin 11 recognizes making social justice a public agenda within qualitative inquiry. He emphasized that qualitative inquiry can contribute to social justice through ( a ) identifying different definitions of a problem and/or situation that is being evaluated with some agreement that change is required; ( b ) the assumptions that are held by policy makers, clients, welfare workers, online professionals, and other interested parties can be located and shown to be correct or incorrect; ( c ) strategic points of interventions can be identified and thus evaluated and improved; ( d ) suggest alternative moral points of view from which the problem, the policy, and the program can be interpreted and assessed; and ( e ) the limits of statistics and statistical evaluations can be exposed with the more qualitative materials furnished by this approach. 11

WHO DOES QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

Qualitative research is done by researchers in the social sciences as well as by practitioners in fields that concern themselves with issues related to human behavior and functioning. 3 They are also health professionals who are able to identify a research question and able to recognize the particular context and situation that would achieve the best answers. 10 According to Morse, 10 the qualitative health researcher should be an expert methodologist who should have the understanding of illness, the patient’s condition, and the staff roles and relationships and able to balance the clinical situation from different perspectives. 10 (p23) A qualitative researcher also requires theoretical and social sensibility, interactional skills, and the ability to maintain analytical distance while drawing upon past experience and theoretical knowledge to interpret what is seen or observed. 3

WHAT ARE THE CHARACTERISTICS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

Creswell 12 discussed that qualitative research studies today involve closer attention to the interpretive nature of inquiry and situating the study within the political, social, and cultural context of the researchers, participants, and readers of the study. He presented several characteristics of qualitative research, which are ( a ) natural setting: data are collected face-to-face in the field at the site where participants experience the phenomenon under study; the inquiry should be conducted in a way that does not disturb the natural context of the phenomenon; ( b ) researcher as key instrument: the researchers collect the data themselves rather than relying on instruments developed by others; ( c ) multiple sources of data: researchers gather multiple forms of data including interviews, observations, and examining documents rather than rely on a single source; ( d ) inductive data analysis: data are organized into abstract units of information (“bottom-up” or moving from specific to general), working back and forth between the themes and the database until a comprehensive set of themes is established and ending up with general conclusions or theories; ( e ) participant’s meanings: the researchers keep a focus on learning the meaning that the participants hold about the phenomenon, not the meaning that the researchers bring to the study; ( f ) emergent design: the initial plan for the study cannot be tightly prescribed; rather, it is emergent, and all phases of the process may change or shift after the researchers enter the field and begin to collect the data; ( g ) theoretical lens: use of a “lens” to view the study such as the concept of culture, gender, race or class differences, and social, political, or historical context of the problem under study; ( h ) interpretive inquiry: a form of inquiry in which researchers make interpretation of what they see, hear, and understand that cannot be separated from their own background, history, context, and prior understanding; ( i ) holistic account: reporting multiple perspectives, identifying the many factors involved in a situation, and sketching the larger picture that emerges. 12

WHAT ARE THE METHODS FREQUENTLY USED IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

The research question dictates the method to be used for a qualitative study. Qualitative and quantitative questions are distinct and serve different purposes. 10 Some of the different types of qualitative research that will be discussed in this article are phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, case study, and narrative research. Researchers from different disciplines use these approaches depending on what the purpose of the study is.

Narrative research begins with the experiences as expressed in lived and told stories of individuals. Narrative is a spoken word or written text giving an account of an event/action chronologically connected. Some examples of this approach are biographical studies, autobiographies, and life stories. Kvangarsnes et al 13 explored the patient perceptions of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and their experiences of their relations with health personnel during care and treatment using narrative research design. Ten in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with patients who had been admitted to 2 intensive care units (ICUs) in Western Norway during the autumn of 2009 and the spring of 2010. Narrative analysis and theories on trust and power were used to analyze the interviews. The patients perceived that they were completely dependent on others during the acute phase. Some stated that they had experienced an altered perception of reality and had not understood how serious their situation was. Although the patients trusted the health personnel in helping them breathe, they also told stories about care deficiencies and situations in which they felt neglected. This study shows that patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease often feel wholly dependent on health personnel during the exacerbation and, as a result, experience extreme vulnerability.

Whereas a narrative approach explores the life of a single person, a phenomenological study describes the meaning for several individuals of their lived experiences of a phenomenon. 12 Phenomenology is the most inductive of all qualitative methods. 10 The philosophical assumptions of phenomenology rest on some common grounds: the study of the lived experiences of persons, the view that these experiences are conscious ones and the development of descriptions of the essences of these experiences, not explanations or analysis. 12 There are different types of phenomenological approaches, namely, descriptive-transcendental (Husserl, Giorgi), interpretive/hermeneutic (Heidegger, Gadamer, Jen-Luc Nancy), descriptive-hermeneutic (van Manen), empirical-transcendental (Moustakas), and existential (Sarte, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty). A phenomenological study conducted by Cypress 14 explored the lived experiences of nurses, patients, and family members during critical illness in the emergency department (ED). Data were collected over a 6-month period by means of in-depth interviews, and thematic analysis was done using van Manen’s 15 hermeneutic-phenomenological approach. The findings of this qualitative phenomenological study indicate that the patient’s and family member’s perception of the nurses in the ED relates to their critical thinking skills, communication, sensitivity, and caring abilities. Nurses of this study identified that response to the patient’s physiological deficit is paramount in the ED, and involving the patients and families in the human care processes will help attain this goal.

While phenomenology aims to illuminate themes and describe the meaning of lived experiences of a number of individuals, grounded theory has the intent to move beyond description and to generate or discover a theory, an abstract analytical schema of a process, or interaction shaped by the views of a large number of participants. 12 This qualitative method was developed by Glaser and Strauss 16 in 1967. Other grounded theorists followed, including Clarke, 17 who relies on postmodern perspectives, and Charmaz, 18 on constructivist approach. Gallagher et al 19 collected and analyzed qualitative data using grounded theory to understand nurses’ end-of-life (EOL) decision-making practices in 5 ICUs in different cultural contexts. Interviews were conducted with 51 experienced ICU nurses in university or hospital premises in 5 countries. The comparative analysis of the data within and across data generated by the different research teams enabled researchers to develop a deeper understanding of EOL decision-making practices in the ICU. The core category that emerged was “negotiated reorienting.” Gallagher et al 19 stated, “Whilst nurses do not make the ‘ultimate’ EOL decisions, they engage in 2 core practices: consensus seeking (involving coaxing, information cuing and voice enabling) and emotional holding (creating time-space and comfort giving).” 19 (p794)

Although a grounded theory approach examines a number of individuals to develop a theory, participants are not studied as 1 unit. Ethnography uses a larger number of individuals and focuses on an entire cultural group as 1 unit of analysis. This qualitative approach describes and interprets the shared and learned patters of values, behaviors, beliefs, and language of a cultural-sharing group. 12 There are many forms of ethnography, namely, confessional, life history, autoethnography, feminist, ethnographic novels, visual ethnography found in photography and video, and electronic media. Price 20 explored what aspects affect registered health care professionals’ ability to care for patients within the technological environment of a critical care unit. Ethnography was utilized to focus on the cultural elements within a situation. Data collection involved participant observation, document review, and semistructured interviews. Nineteen participants took part in the study. An overarching theme of the “crafting process” was developed with subthemes of “vigilance,” “focus of attention,” “being present,” and “expectations,” with the ultimate goal of achieving the best interests for the individual patient.

A culture-sharing group in ethnography can be considered a case, but its aim is to ascertain how the culture works rather than understanding 1 or more specific cases within a bounded system. Creswell 12 defines case study research as an approach in which the researcher explores a bounded system (a case) or multiple bounded systems (cases) over time through detailed in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information and reports a case description and case-based themes. 12 (p73) In terms of intent, there are 3 types of case study: single instrumental, collective or multiple, and the intrinsic case study. Hyde-Wyatt 21 studied spinally injured patients on sedation in the ICU. A reflection-on-action exercise was carried out when a spinally injured patient became physically active during a sedation hold. This was attributed to hyperactive delirium. Reflection on this incident led to a literature search for guidance on the likelihood of delirium causing secondary spinal injury in patients with unstable fractures. Through a case study approach, the research was reviewed in relation to a particular patient. This case study illustrated that there was a knowledge deficit when it came to managing the combination of the patient’s spinal injury and delirium. Sedation cessation episodes are an essential part of patient care on intensive care. For spinally injured patients, these may need to be modified to sedation reductions to prevent sudden wakening and uncontrolled movement should the patient be experiencing hyperactive delirium.

WHAT IS THE PROCESS OF CONCEPTUALIZING AND DESIGNING A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?

Designing a qualitative is not a fully structured, rigid process. Even books and experts vary in their understanding and guides in the “how to” perspective of a qualitative inquiry. Conducting a qualitative study is also extremely difficult. 10 Sometimes there is concern about access and the qualitative procedures involved in data collection including disclosure of participant’s identity and confidentiality of data. Nevertheless, qualitative research involves a rigorous and scientific process that serves as guide for researchers who are planning to embark on a journey and complete a naturalistic inquiry.

Unlike quantitative research that involves a fairly linear process, qualitative studies have a flexible approach and flow of activities, and the researchers do not know in advance exactly how the study will unfold. 22 The process of designing a qualitative study does not begin with the methods—which in fact is the easiest part of naturalistic research. 12 Qualitative researchers usually begin with a broad topic focusing on 1 aspect or a phenomenon of which little is known. The phenomenon may be one in the “real world,” a gap in the literature, or past findings of investigations, for example, in the area of social and human sciences. 12 A fairly broad question is then posed to be able to allow the focus to be delineated and sharpened once the study is underway.

Once the research question is posed, the researchers should conduct a brief literature review to inform the question asked and to help establish the significance of the problem. There is a continuous debate about the value of doing a literature review prior to collecting of data and how much of it should be done. Some believe that knowledge about findings of previous studies might influence the conceptualization of the phenomenon of interest, which ideally should be illuminated from the participants rather than on prior findings. 22 A grounded theory investigator, for example, may make a point of not conducting a review of literature before beginning the study to avoid “contamination” of the data with preconceived concepts and notions about what might be relevant. 2 After the review of literature, the researchers must identify an appropriate site for the study to be conducted.

Selecting and gaining entry to the site require knowledge of settings in which participants in their lifeworld are experiencing the phenomenon under study. For example, research in the area of health is a very broad topic. A researcher should determine definitions, concepts, scope, and theories about health that will be used for the proposed qualitative inquiry. Health can be perceived as absence or presence of illness, physical, psychosocial, psychological, and spiritual health of individuals, families, or groups. 10 Morse 10 further stated that “Research into the intimate, experiential and interpersonal aspects of illness, into caring for the ill, and into seeking and maintaining wellness introduces extraordinary methodological challenges.” 10 (p89) Thus, knowledge about the characteristics of participants who will be recruited for the study and the specific context of the settings (ie, hospital/institution, community/outpatient) where they are at the time when research will be conducted is important. To be able to gain entry to the site, the ethical aspect of the study should also be addressed. Approval from the institution’s institutional review board and informed consent from the participants must be obtained. Qualitative studies have special ethical concerns involved because of the more intimate nature of the relationship that typically develop between researchers and participants. 22 The researchers must develop specific plans addressing these issues. After addressing the ethical concerns and gaining entry to the site, an overall approach should be planned and developed.

It has been previously addressed that even though the researchers plan for a specific approach to be used, the design can be emergent during the course of data collection. Modifications are made as the need arises. It is rare that a qualitative study has rigidly structured design that will prohibit changes while in the field, 22 but being aware that the purposes, questions, and methods of research are all interconnected and interrelated so that the study appears as a cohesive whole rather than fragmented isolated parts. 5 For example, patients in hospitals have limited abilities related to their medical condition and the contextual features of a hospital. A patient’s condition may demand a different method be used because of patient fatigue, the interruptions of data collection for treatments, or physician’s rounds and visitors. In this context, the study requires modifications of methods, and participation in a research study has the lowest priority at this specific moment and time. 10

In qualitative studies, sampling, data collection, and analysis including interpretation take place repetitively. The sampling method usually used is purposive. Qualitative researchers use rigorous data collection procedures by talking to participants face-to-face, interviewing, and observing them (individual, focus groups, or an entire culture) to be able to explore the phenomenon under study. The discussions and observations are loosely structured, allowing participants full range of beliefs, feelings, and behaviors. 22 Other types of information that can be collected are documents, photographs, audiovisual materials, sounds, e-mail massages, digital text messages, and computer software. The backbone of qualitative research is extensive collection of data from multiple sources of information. 12 After organizing and storing the data, the researcher will try to make sense of the data, working inductively from particulars to more general perspectives until categories, codes, and themes emerge and are illuminated, which are used to build a rich description of the phenomenon. 12,22 The researcher analyzes data using multiple levels of abstraction. Analysis and interpretation are ongoing concurrent activities that guide the researchers about the kinds of questions to ask or observations to make. The kinds of data gathered become increasingly meaningful as the theory emerges. When themes and categories become repetitive and redundant and no new information can be gleaned, the researcher has reached data saturation and thus stops collecting data and recruitment of participants. 22 Trustworthiness of the data and rigor have to be then established. Steps have to be taken to confirm that the findings accurately reflect the experiences and perceptions of participants rather than the researcher’s viewpoints. Some of the strategies that can be used are validation techniques that include confirming and triangulating data from several sources, going back to participants, sharing preliminary interpretations with them, asking them whether the researcher’s thematic analysis is consistent with their experiences, 22 (p55) and having other expert researchers review the procedures undertaken and interpretations made. 12

FINAL THOUGHTS

Qualitative research uses a naturalistic approach that seeks to understand phenomena in context-specific settings, attempting to make sense of it and interpreting in terms of meaning people bring to them. It contributes to the humanizing of health care as it addresses content about health and illness. Qualitative research does not have firm or rigid guidelines and takes time to conduct. Some of the methods for a qualitative inquiry are narrative research, phenomenology, grounded theory, case study, and ethnography. Although the study design emerges during the inquiry, it follows the pattern of scientific research. Researchers collect data rigorously in natural settings over a period and analyze them inductively to establish patterns or themes. Ethical decisions and considerations for rigor and trustworthiness are also continuously threaded throughout the study. The final report presents the active voices of participants and the description and interpretation of the meaning of the phenomenon including the reflexivity of the researcher.

Goals of nursing; Health care; Qualitative research

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Qualitative research: challenges and dilemmas, data analysis software in qualitative research: preconceptions, expectations,..., qualitative research methods: a phenomenological focus, generational diversity.

The purpose of qualitative research

Cite this chapter.

- Janice M. Morse 3 &

- Peggy Anne Field 4

717 Accesses

5 Citations

Research fills a vital and important role in society: it is the means by which discoveries are made, ideas are confirmed or refuted, events controlled or predicted and theory developed or refined. All of these functions contribute to the development of knowledge. However, no single research approach fulfills all of these functions, and the contribution of qualitative research is both vital and unique to the goals of research in general. Qualitative research enables us to make sense of reality, to describe and explain the social world and to develop explanatory models and theories. It is the primary means by which the theoretical foundations of social sciences may be constructed or re-examined.

Research is to see what everybody has seen and to think what nobody has thought. (Albert Szent-Gyorgy)

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Bohannan, L. (1956/1992) Shakespeare in the bush, in Qualitative Health Research , (ed. J.M. Morse), Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 20–30.

Google Scholar

Brace, C.L., Gamble, G.R. and Bond, J.T. (eds) (1971) Race and Intelligence: Anthropological Studies Number 8 , American Anthropological Association, Washington, DC.

Burton, A. (1974) The nature of personality theory, in Operational Theories of Personality , (ed. A. Burton), Brunner/Mazel, New York, pp. 1–19.

Chapman, C.R. (1976) Measurement of pain: problems and issues. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy , 1 , 345.

Corbin, J. (1986) Coding, writing memos, and diagramming, in From Practice to Grounded Theory , (eds W.C. Chenitz and J.M. Swanson), Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park, CA, pp. 91–101.

Duffy, M.E. (1985) Designing nursing research: the qualitative — quantitative debate. Journal of Advanced Nursing , 10 , 225–32.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Elliott, M.R. (1983) Maternal infant bonding. Canadian Nurse , 79 (8), 28–31.

PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Engelhardt, H.T. (1974/1992) The disease of masturbation: values and the concept of disease, in Qualitative Health Research , (ed. J.M. Morse), Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 5–19.

Feyerabend, P. (1978) Against Method , Varo, London.

Geertz, C. (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures , Basic Books, New York.

Glaser, B.G. (1978) Theoretical Sensitivity , The Sociology Press, Mill Valley, CA.

Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research , Aldine, Chicago.

Goodwin, L.D. and Goodwin, W.L. (1984) Qualitative vs. quantitative research or qualitative and quantitative research? Nursing Research , 33 (6), 378–80.

Hinds, P.S., Chaves, D.E. and Cypess, S.M. (1992) Context as a source of meaning and understanding, in Qualitative Health Research , (ed. J.M. Morse), Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 31–49.

Klaus, M.H. and Kennel, J.H. (1976) Parent Infant Bonding: The Impact of Early Separation or Loss on Family Development , Mosby, St Louis.

Morse, J.M. (1989/1992) ‘Euch, those are for your husband!’: examination of cultural values and assumptions associated with breastfeeding, in Qualitative Health Research , (ed. J.M. Morse), Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 50–60.

Morse, J.M. (1992) If you believe in theories.... Qualitative Health Research , 2 (3), 259–61.

Article Google Scholar

Morse, J.M., Harrison, M. and Prowse, M. (1986) Minimal breastfeeding. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing , 15 (4), 333–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Pelto, P.J. and Pelto, G.H. (1978) Anthropological Research: The Structure of Inquiry , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Book Google Scholar

Scheper-Hughes, N. (1992) Death Without Weeping , University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Smith, J.K. (1983) Quantitative versus qualitative research: an attempt to clarify the issue. Educational Researcher , 12 (3), 6–13.

Smith, J.K. and Heshusius, L. (1986) Closing down the conversation: the end of the quantitative — qualitative debate among educational inquirers. Educational Researcher , 15 , 4–12.

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques , Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Tesch, S. (1981) Disease causality and politics. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law , 6 (1), 369–89.

Vidich, A.J. and Lyman, S.M. (1994) Qualitative methods: their history in sociology and anthropology, in Handbook of Qualitative Research , (eds N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln), Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 23–59.

Wolcott, H.F. (1992) Posturing in qualitative research, in The Handbook of Qualitative Research in Education , (eds M.D. LeCompte, W.L. Millroy and J. Preissle), Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 3–52.

Further Reading

Atkinson, P. (1994) Some perils of paradigms. Qualitative Health Research , 5 (1).

Denzin, N.K. and Lincoln, Y.S. (eds) (1994) Part II: Major paradigms and perspectives, in Handbook of Qualitative Research , Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 99–198.

Filstead, W.J. (ed.) (1970) Qualitative Methodology: Firsthand Involvement with the Social World , Rand McNally, Chicago.

Gilbert, N. (ed.) (1993) Researching Social Life , Sage, London.

Glassner, B. and Moreno, J.D. (eds) (1989) The Qualitative-Quantitative Distinction in the Social Sciences , Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Hammersley, M. (ed) (1993) Social Research: Philosophy, Politics and Practice , Sage, London.

Morse, J.M. (ed.) (1992) Part I: The characteristics of qualitative research, in Qualitative Health Research , Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 69–90.

Morse, J.M., Bottorff, J.L., Neander, W. et al. (1991/1992) Comparative analysis of conceptualizations and theories of caring, in Qualitative Health Research , (ed. J.M. Morse), Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 69–90.

Noblit, G.W. and Engel, J.D. (1991/1992) The holistic injunction: an ideal and a moral imperative for qualitative research, in Qualitative Health Research , (ed. J.M. Morse), Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 43–63.

Rabinow, P. and Sullivan, W.M. (eds) (1979) Interpretive Social Science: A Reader , University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Smith, R.B. and Manning, P.K. (eds) (1982) A Handbook of Social Science Methods , Ballinger, Cambridge, MA.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing, Pennsylvania State University, USA

Janice M. Morse ( Professor of Nursing and Behavioural Science )

Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta, Canada

Peggy Anne Field ( Professor Emeritus )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1996 Janice M. Morse and Peggy Anne Field

About this chapter

Morse, J.M., Field, P.A. (1996). The purpose of qualitative research. In: Nursing Research. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-4471-9_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-4471-9_1

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-0-412-60510-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4899-4471-9

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Library Research Guides - University of Wisconsin Ebling Library

Uw-madison libraries research guides.

- Course Guides

- Subject Guides

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Nursing Resources

- Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

Nursing Resources : Types of Research within Qualitative and Quantitative

- Definitions of

- Professional Organizations

- Nursing Informatics

- Nursing Related Apps

- EBP Resources

- PICO-Clinical Question

- Types of PICO Question (D, T, P, E)

- Secondary & Guidelines

- Bedside--Point of Care

- Pre-processed Evidence

- Measurement Tools, Surveys, Scales

- Types of Studies

- Table of Evidence

- Qualitative vs Quantitative

- Cohort vs Case studies

- Independent Variable VS Dependent Variable

- Sampling Methods and Statistics

- Systematic Reviews

- Review vs Systematic Review vs ETC...

- Standard, Guideline, Protocol, Policy

- Additional Guidelines Sources

- Peer Reviewed Articles

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

- Writing a Research Paper or Poster

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Levels of Evidence (I-VII)

- Reliability

- Validity Threats

- Threats to Validity of Research Designs

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Models

- PRISMA, RevMan, & GRADEPro

- ORCiD & NIH Submission System

- Understanding Predatory Journals

- Nursing Scope & Standards of Practice, 4th Ed

- Distance Ed & Scholarships

- Assess A Quantitative Study?

- Assess A Qualitative Study?

- Find Health Statistics?

- Choose A Citation Manager?

- Find Instruments, Measurements, and Tools

- Write a CV for a DNP or PhD?

- Find information about graduate programs?

- Learn more about Predatory Journals

- Get writing help?

- Choose a Citation Manager?

- Other questions you may have

- Search the Databases?

- Get Grad School information?

Aspects of Quantative (Empirical) Research

♦ Statement of purpose—what was studied and why.

♦ Description of the methodology (experimental group, control group, variables, test conditions, test subjects, etc.).

♦ Results (usually numeric in form presented in tables or graphs, often with statistical analysis).

♦ Conclusions drawn from the results.

♦ Footnotes, a bibliography, author credentials.

Hint: the abstract (summary) of an article is the first place to check for most of the above features. The abstract appears both in the database you search and at the top of the actual article.

Types of Quantitative Research

There are four (4) main types of quantitative designs: descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental.

samples.jbpub.com/9780763780586/80586_CH03_Keele.pdf

Types of Qualitative Research

|

http://wilderdom.com/OEcourses/PROFLIT/Class6Qualitative1.htm

Log in using your username and password

You are here

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102939 Statistics from Altmetric.comRequest permissions. If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways. Qualitative research methods allow us to better understand the experiences of patients and carers; they allow us to explore how decisions are made and provide us with a detailed insight into how interventions may alter care. To develop such insights, qualitative research requires data which are holistic, rich and nuanced, allowing themes and findings to emerge through careful analysis. This article provides an overview of the core approaches to data collection in qualitative research, exploring their strengths, weaknesses and challenges. Collecting data through interviews with participants is a characteristic of many qualitative studies. Interviews give the most direct and straightforward approach to gathering detailed and rich data regarding a particular phenomenon. The type of interview used to collect data can be tailored to the research question, the characteristics of participants and the preferred approach of the researcher. Interviews are most often carried out face-to-face, though the use of telephone interviews to overcome geographical barriers to participant recruitment is becoming more prevalent. 1 A common approach in qualitative research is the semistructured interview, where core elements of the phenomenon being studied are explicitly asked about by the interviewer. A well-designed semistructured interview should ensure data are captured in key areas while still allowing flexibility for participants to bring their own personality and perspective to the discussion. Finally, interviews can be much more rigidly structured to provide greater control for the researcher, essentially becoming questionnaires where responses are verbal rather than written. Deciding where to place an interview design on this ‘structural spectrum’ will depend on the question to be answered and the skills of the researcher. A very structured approach is easy to administer and analyse but may not allow the participant to express themselves fully. At the other end of the spectrum, an open approach allows for freedom and flexibility, but requires the researcher to walk an investigative tightrope that maintains the focus of an interview without forcing participants into particular areas of discussion. Example of an interview schedule 3What do you think is the most effective way of assessing a child’s pain? Have you come across any issues that make it difficult to assess a child’s pain? What pain-relieving interventions do you find most useful and why? When managing pain in children what is your overall aim? Whose responsibility is pain management? What involvement do you think parents should have in their child’s pain management? What involvement do children have in their pain management? Is there anything that currently stops you managing pain as well as you would like? What would help you manage pain better? Interviews present several challenges to researchers. Most interviews are recorded and will need transcribing before analysing. This can be extremely time-consuming, with 1 hour of interview requiring 5–6 hours to transcribe. 4 The analysis itself is also time-consuming, requiring transcriptions to be pored over word-for-word and line-by-line. Interviews also present the problem of bias the researcher needs to take care to avoid leading questions or providing non-verbal signals that might influence the responses of participants. Focus groupsThe focus group is a method of data collection in which a moderator/facilitator (usually a coresearcher) speaks with a group of 6–12 participants about issues related to the research question. As an approach, the focus group offers qualitative researchers an efficient method of gathering the views of many participants at one time. Also, the fact that many people are discussing the same issue together can result in an enhanced level of debate, with the moderator often able to step back and let the focus group enter into a free-flowing discussion. 5 This provides an opportunity to gather rich data from a specific population about a particular area of interest, such as barriers perceived by student nurses when trying to communicate with patients with cancer. 6 From a participant perspective, the focus group may provide a more relaxing environment than a one-to-one interview; they will not need to be involved with every part of the discussion and may feel more comfortable expressing views when they are shared by others in the group. Focus groups also allow participants to ‘bounce’ ideas off each other which sometimes results in different perspectives emerging from the discussion. However, focus groups are not without their difficulties. As with interviews, focus groups provide a vast amount of data to be transcribed and analysed, with discussions often lasting 1–2 hours. Moderators also need to be highly skilled to ensure that the discussion can flow while remaining focused and that all participants are encouraged to speak, while ensuring that no individuals dominate the discussion. 7 ObservationParticipant and non-participant observation are powerful tools for collecting qualitative data, as they give nurse researchers an opportunity to capture a wide array of information—such as verbal and non-verbal communication, actions (eg, techniques of providing care) and environmental factors—within a care setting. Another advantage of observation is that the researcher gains a first-hand picture of what actually happens in clinical practice. 8 If the researcher is adopting a qualitative approach to observation they will normally record field notes . Field notes can take many forms, such as a chronological log of what is happening in the setting, a description of what has been observed, a record of conversations with participants or an expanded account of impressions from the fieldwork. 9 10 As with other qualitative data collection techniques, observation provides an enormous amount of data to be captured and analysed—one approach to helping with collection and analysis is to digitally record observations to allow for repeated viewing. 11 Observation also provides the researcher with some unique methodological and ethical challenges. Methodologically, the act of being observed may change the behaviour of the participant (often referred to as the ‘Hawthorne effect’), impacting on the value of findings. However, most researchers report a process of habitation taking place where, after a relatively short period of time, those being observed revert to their normal behaviour. Ethically, the researcher will need to consider when and how they should intervene if they view poor practice that could put patients at risk. The three core approaches to data collection in qualitative research—interviews, focus groups and observation—provide researchers with rich and deep insights. All methods require skill on the part of the researcher, and all produce a large amount of raw data. However, with careful and systematic analysis 12 the data yielded with these methods will allow researchers to develop a detailed understanding of patient experiences and the work of nurses.

Competing interests None declared. Patient consent Not required. Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed. Read the full text or download the PDF:An official website of the United States government The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site. The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Save citation to fileEmail citation, add to collections.

Add to My BibliographyYour saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

Maintaining reflexivity in qualitative nursing researchAffiliation.

Aims: Reflexivity is central to the construction of knowledge in qualitative research. This purpose of this paper was to outline one approach when using reflexivity as a strategy to ensure quality of the research process. Design: In this exploratory research, reflexivity was established and maintained by using repeated questionnaires, completed online. Using the approach presented by Bradbury-Jones (2007) and Peshkin's I's, the aim of the research was to identify the researcher's values, beliefs, perspectives and perceptions prevalent in the research. Methods: Qualitative data were collected in online reflexive questionnaires, completed monthly by the researcher from January 2017 to December 2018. Data analysis used interpretive and reflective reading and inductive processes. Results: Seventeen questionnaires were analysed. Data indicated use of questionnaires enabled and detailed development of specific strategies to ensure trustworthiness. Importantly, reflexivity, supported by questionnaires, brought about transformation through self-awareness and enlightenment. Keywords: nursing research; qualitative research; reflexivity; trustworthiness. © 2021 The Authors. Nursing Open published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. PubMed Disclaimer Conflict of interest statementNo conflict of interest has been declared by the author. Similar articles

LinkOut - more resourcesFull text sources.

NCBI Literature Resources MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

The needs and experiences of critically ill patients and family members in intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital in Malaysia: a qualitative study