Advertisement

Understanding the value of inclusive education and its implementation: A review of the literature

- Published: 07 September 2020

- Volume 49 , pages 135–152, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Anthoula Kefallinou 1 ,

- Simoni Symeonidou 1 , 2 &

- Cor J. W. Meijer 1

9084 Accesses

43 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

European countries are increasingly committed to human rights and inclusive education. However, persistent educational and social inequalities indicate uneven implementation of inclusive education. This article reviews scholarly evidence on inclusion and its implementation, to show how inclusive education helps ensure both quality education and later social inclusion. Structurally, the article first establishes a conceptual framework for inclusive education, next evaluates previous research methodologies, and then reviews the academic and social benefits of inclusion. The fourth section identifies successful implementation strategies. The article concludes with suggestions on bridging the gap between inclusive education research, policy, and practice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Inclusion and equity in education: Making sense of global challenges

Montessori, Waldorf, and Reggio Emilia: A Comparative Analysis of Alternative Models of Early Childhood Education

Inclusive education: developments and challenges in south africa.

Ainscow, M. (1999). Understanding the development of inclusive schools . London: Falmer.

Google Scholar

Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6 (1), 7–16.

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2004). Understanding and developing inclusive practices in schools: A collaborative action research network. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 8 (2), 125–139.

Ainscow, M., Dyson, A., Goldrick, S., & West, M. (2012). Making schools effective for all: Rethinking the task. School Leadership & Management, 32 (3), 197–213.

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organisational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14 (4), 401–416.

Allan, J. (2014). Inclusive education and the arts. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44 (4), 511–523.

Baer, R. M., Daviso, A. W., Flexer, R. W., McMahan Queen, R., & Meindl, R. S. (2011). Students with intellectual disabilities: Predictors of transition outcomes. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 34 (3), 132–141.

Baker, E. T., Wang, M. C., & Walberg, H. J. (1994/95). The effects of inclusion on learning. Educational Leadership, 52 (4), 33–35.

Båtevik, F. O., & Myklebust, J. O. (2006). The road to work for former students with special educational needs: Different paths for young men and young women? Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 8 (1), 38–52.

Bele, I. V., & Kvalsund, R. (2015). On your own within a network? Vulnerable youths’ social networks in transition from school to adult life. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 17 (3), 195–220.

Bele, I. V., & Kvalsund, R. (2016). A longitudinal study of social relationships and networks in the transition to and within adulthood for vulnerable young adults at ages 24, 29 and 34 years: Compensation, reinforcement or cumulative disadvantages? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31 (3), 314–329.

Benz, M., Lindstrom, L., & Yovanoff, P. (2000). Improving graduation and employment outcomes of students with disabilities: Predictive factors and student perspectives. Exceptional Children, 66 (4), 509–529.

Blatchford, P., Russell, A., & Webster, R. (2012). Reassessing the impact of teaching assistants: How research challenges practice and policy . Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

Blatchford, P., Russell, A., & Webster, R. (2016). Maximising the impact of teaching assistants: Guidance for school leaders and teachers (2nd ed.). Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

Booth, T. (2009). Keeping the future alive: Maintaining inclusive values in education and society. In M. Alur & V. Timmons (Eds.), Inclusive education across cultures: Crossing boundaries, sharing ideas (pp. 121–134). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Campbell, C. (2011). How to involve hard-to-reach parents: Encouraging meaningful parental involvement with schools . Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

Carlberg, C., & Kavale, K. (1980). The efficacy of special versus regular class placement for exceptional children: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Special Education, 14 (3), 295–309.

Cimera, R. E. (2010). Can community-based high school transition programs improve the cost-efficiency of supported employment? Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 33 (1), 4–12.

Cimera, R. E. (2011). Does being in sheltered workshops improve the employment outcomes of supported employees with intellectual disabilities? Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 35, 21–27.

Cobb, R. B., Lipscomb, S., Wolgemuth, J., Schulte, T., Veliquette, A., Alwell, M., et al. (2013). Improving post-high school outcomes for transition-age students with disabilities: An evidence review (NCEE 201 3–4011) . Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences.

Cobigo, V., Ouelette-Kuntz, H., Lysaght, R., & Martin, L. (2012). Shifting our conceptualization of social inclusion. Stigma Research and Action, 2 (2), 74–84.

Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights (2017). Fighting school segregation in Europe through inclusive education: A position paper . rm.coe.int/fighting-school-segregationin-europe-throughinclusive-education-a-posi/168073fb65.

Council of the European Union (2018a). Council recommendation on promoting common values, inclusive education and the European dimension of teaching . https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0607(01)&from=EN .

Council of the European Union (2018b). Council conclusions on moving towards a vision of a European Education Area . https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018XG0607(01)&rid=5 .

CRPD [United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities] (2016). General comment no. 4 (2016), Article 24: Right to inclusive education . https://www.refworld.org/docid/57c977e34.html .

Day, C., Gu, Q., & Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52 (2), 221–258.

de Graaf, G., Van Hove, G., & Haveman, M. (2013). More academics in regular schools? The effect of regular versus special school placement on academic skills in Dutch primary school students with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57 (1), 21–38.

De Vroey, A., Struyf, E., & Petry, K. (2015). Secondary schools included: A literature review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20 (2), 109–135.

Dessemontet, R. S., Bless, G., & Morin, D. (2012). Effects of inclusion on the academic achievement and adaptive behaviour of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56 (6), 579–587.

Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. How we can learn to fulfil our potential . New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Dyson, A., Howes, A., & Roberts, B. (2002). A systematic review of the effectiveness of school-level actions for promoting participation by all students. In Research evidence in education library . London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=276 .

Dyson, D., Howes, A., Roberts, B., & Mitchell, D. (Eds.) (2005). What do we really know about inclusive schools? A systematic review of the research evidence. In Special educational needs and inclusive education: Major themes in education . London: Routledge.

Dyssegaard, C. B., & Larsen, M. S. (2013). Evidence on inclusion. Danish clearinghouse for educational research. Copenhagen: Department of Education, Aarhus University.

Erskine, H. E., Norman, R. E., Ferrari, A. J., Chan, G. C., Copeland, W. E., Whiteford, H. A., et al. (2016). Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55 (10), 841–850.

European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (2003). Inclusive education and classroom practice: Summary report . Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/inclusive-education-and-classroom-practices_iecp-en.pdf .

European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education (2013). Organisation of provision to support inclusive education – Literature review . Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/organisation-provision-support-inclusive-education-literature-review .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2015). Agency position on inclusive education systems . https://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/PositionPaper-EN.pdf .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016a). Raising the achievement of all learners in inclusive education—Literature review (A. Kefallinou, Ed.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/raising-achievement-all-learners-inclusive-education-literature-review .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016b). Early school leaving and learners with disabilities and/or special educational needs: A review of the research evidence focusing on Europe (A. Dyson & G. Squires, Eds.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/early-school-leaving-and-learners-disabilities-andor-special-educational-0 .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2017a). Early school leaving and learners with disabilities and/or special educational needs: To what extent is research reflected in European Union policies? (G. Squires & A. Dyson, Eds.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/early-school-leaving-and-learners-disabilities-andor-special-educational .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2017b). Raising the achievement of all learners in inclusive education: Lessons from European policy and practice (A. Kefallinou & V. J. Donnelly, Eds.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/raising-achievement-all-learners-project-overview .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018a). Evidence of the link between inclusive education and social inclusion: A review of the literature (S. Symeonidou, Ed.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/evidence-literature-review .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018b). Key actions for raising achievement: Guidance for teachers and leaders (V. Donnelly & A. Kefallinou, Eds.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/key-actions-raising-achievement-guidance-teachers-and-leaders .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018c). Supporting inclusive school leadership: Literature review (E. Óskarsdóttir, V. J. Donnelly and M. Turner-Cmuchal, Eds.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/supporting-inclusive-school-leadership-literature-review .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2019a). Preventing school failure: A review of the literature (G. Squires & A. Kefallinou, Eds.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/preventing-school-failure-literature-review .

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2019b). Preventing school failure: Examining the potential of inclusive education policies at system and individual levels (A. Kefallinou, Ed.). Odense, Denmark. https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/preventing-school-failure-synthesis-report .

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2020). Fundamental rights report —2020. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2020-fundamental-rights-report-2020_en.pdf .

Farrell, P., Alborz, A., Howes, A., & Pearson, D. (2010). The impact of teaching assistants on improving pupils’ academic achievement in mainstream schools: A review of the literature. Educational Review, 62 (4), 435–448.

Farrell, P., Dyson, A., Polat, F., Hutcheson, G., & Gallannaugh, F. (2007). Inclusion and achievement in mainstream schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 22 (2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250701267808 .

Article Google Scholar

Faubert, B. (2012). A literature review of school practices to overcome school failure. OECD Education Working Paper no. 68. Paris: OECD. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k9flcwwv9tk-en .

Flecha, R. (2015). Successful educational actions for inclusion and social cohesion in Europe . Cham: Springer.

Flexer, R. W., Daviso, A. W., Baer, R. M., McMahan Queen, R., & Meindl, R. S. (2011). An epidemiological model of transition and postschool outcomes. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 34 (2), 83–94.

Florian, L., & Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. British Educational Research Journal, 37 (5), 813–828.

Francis, B., Archer, L., Hodgen, J., Pepper, D., Taylor, B., & Travers, M. C. (2017). Exploring the relative lack of impact of research on ‘ability grouping’ in England: A discourse analytic account. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47 (1), 1–17.

Fullan, M. (2002). The change. Educational Leadership, 59 (8), 16–20.

Gill, M. (2005). The myth of transition: Contractualizing disability in the sheltered workshop. Disability & Society, 20 (6), 613–623.

Göransson, K., & Nilholm, C. (2014). Conceptual diversities and empirical shortcomings—A critical analysis of research on inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29 (3), 265–280.

Gross, J. M. S., Haines, S. J., Hill, C., Francis, G. L., Blue-Banning, M., & Turnbull, A. P. (2015). Strong school–community partnerships in inclusive schools are “part of the fabric of the school… we count on them”. School Community Journal, 25 (2), 9–34.

Haines, S. J., Gross, J. M., Blue-Banning, M., Francis, G. L., & Turnbull, A. P. (2015). Fostering family–school and community–school partnerships in inclusive schools: Using practice as a guide. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40 (3), 227–239.

Harris, A. (2012). Leading system-wide improvement. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 15 (3), 395–401.

Hattie, J. A. C. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of 800+ meta-analyses on achievement . Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

Hehir, T., Grindal, T., Freeman, B., Lamoreau, R., Borquaye, Y., & Burke, S. (2016). A summary of the evidence on inclusive education . Cambridge: ABT Associates.

Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45 (3), 740–763.

Jeynes, W. H. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education, 40 (3), 237–269.

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Education, 42 (1), 82–110.

Kalambouka, A., Farrell, P., Dyson, A., & Kaplan, I. (2007). The impact of placing pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools on the achievement of their peers. Educational Research, 49 (4), 365–382.

Kinsella, W., & Senior, J. (2008). Developing inclusive schools: A systemic approach. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12 (5–6), 651–665.

Kools, M., & Stoll, L. (2016). What makes a school a learning organisation? OECD Education Working Paper no. 137. Paris: OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlwm62b3bvh-en .

Kvalsund, R., & Bele, I. V. (2010a). Students with special educational needs—Social inclusion or marginalisation? Factors of risk and resilience in the transition between school and early adult life. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54 (1), 15–35.

Kvalsund, R., & Bele, I. V. (2010b). Adaptive situations and social marginalization in early adult life: Students with special educational needs. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 12 (1), 59–76.

Lang, R., Kett, M., Groce, N., & Trani, J. F. (2011). Implementing the United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: Principles, implications, practice and limitations. ALTER-European Journal of Disability Research/Revue Européenne de Recherche sur le Handicap, 5 (3), 206–220.

Lin-Siegler, X., Dweck, C. S., & Cohen, G. L. (2016). Instructional interventions that motivate classroom learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108 (3), 295.

Looney, J. W. (2011). Integrating formative and summative assessment: Progress toward a seamless system? OECD Education Working Paper no. 58. Paris: OECD.

Loreman, T., Forlin, C., & Sharma, U. (2014). Measuring indicators of inclusive education: A systematic review of the literature. Measuring Inclusive Education, 3, 165–187.

Lunt, N., & Thornton, P. (1994). Disability and employment: Towards an understanding of discourse and policy. Disability & Society, 9 (2), 223–238.

Mitchell, D. (2014). What really works in special and inclusive education: Using evidence-based teaching strategies . London: Routledge.

Muskin, J. A. (2015). Student learning assessment and the curriculum: Issues and implications for policy, design and implementation. In-Progress Reflection no. 1. Geneva: UNESCO International Bureau of Education (IBE).

Myklebust, J. O. (2006). Class placement and competence attainment among students with special educational needs. British Journal of Special Education, 33 (2), 76–81.

Myklebust, J. O. (2007). Diverging paths in upper secondary education: Competence attainment among students with special educational needs. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11 (2), 215–231.

Myklebust, J. O., & Båtevik, F. O. (2005). Economic independence for adolescents with special educational needs. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 20 (3), 271–286.

Myklebust, J. O., & Båtevik, F. O. (2014). Economic independence among former students with special educational needs: Changes and continuities from their late twenties to their mid-thirties. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 29 (3), 387–401.

OECD (2012). Equity and quality in education: Supporting disadvantaged students and schools . Paris: OECD.

Oh-Young, C., & Filler, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the effects of placement on academic and social skill outcome measures of students with disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 47, 80–92.

Pagán, R. (2009). Self-employment among people with disabilities: Evidence for Europe. Disability & Society, 24 (2), 217–229.

Pallisera, M., Vilà, M., & Fullana, J. (2012). Beyond school inclusion: Secondary school and preparing for labour market inclusion for young people with disabilities in Spain. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16 (11), 1115–1129.

Priestley, M. (2000). Adults only: Disability, social policy and the life course. Journal of Social Policy, 29 (3), 421–439.

Rea, P., Mclaughlin, V., & Walther-Thomas, C. (2002). Outcomes for students with learning disabilities in inclusive and pullout programs. Exceptional Children, 68 (2), 203–223.

Rowe, N., Wilkin, A., & Wilson, R. (2012). Mapping of seminal reports on good teaching (NFER Research Programme: Developing the Education Workforce) . Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Ruijs, N. M., & Peetsma, T. T. D. (2009). Effects of inclusion on students with and without special educational needs reviewed. Educational Research Review, 4 (2), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.02.002 .

Salend, S. J., & Garrick Duhaney, L. M. (1999). The impact of inclusion on students with and without disabilities and their educators. Remedial and Special Education, 20 (2), 114–126.

Sebba, J., Brown, N., Steward, S., Galton, M., & James, M. (2007). An investigation of personalised learning approaches used by schools . Nottingham: Department for Education and Skills Publications.

Shandra, C. L., & Hogan, D. (2008). School-to-work program participation and the post-high school employment of young adults with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 29 (2), 117–130.

Sharma, U., & Salend, S. J. (2016). Teaching assistants in inclusive classrooms: A systematic analysis of the international research. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41 (8), 118–134.

Simplican, S. C., Leader, G., Kosciulek, J., & Leahy, M. (2015). Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 38 , 18–29.

Skjong, G., & Myklebust, J. O. (2016). Men in limbo: former students with special educational needs caught between economic independence and social security dependence. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 31 (3), 302–313.

Swann, M., Peacock, A., Hart, S., & Drummond, M. J. (2012). Creating learning without limits . Maidenhead: Open University Press.

SWIFT [Schoolwide Integrated Framework for Transformation] (2017). Equity as a basis for inclusive educational systems change, research to practice brief . Lawrence, KS: Sailor Wayne.

Symeonidou, S., & Mavrou, K. (2019). Problematising disabling discourses on the assessment and placement of learners with disabilities: Can interdependence inform an alternative narrative for inclusion? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35 (1), 70–84.

Szumski, G., Smogorzewska, J., & Karwowski, M. (2017). Academic achievement of students without special educational needs in inclusive classrooms: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 21, 33–54.

UNESCO (2009). Policy guidelines on inclusion in education . Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000177849 .

UNESCO (2017). A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education . Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248254 .

UNICEF (2017). Inclusive education: Including children with disabilities in quality learning: What needs to be done? https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/IE_summary_accessible_220917_brief.pdf .

United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities . www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html .

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world. The 2030 agenda for sustainable development . https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf .

Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24 (1), 80–91.

Waldron, N. L., & McLeskey, J. (2010a). Inclusive school placements and surplus/deficit in performance for students with intellectual disabilities: Is there a connection? Life Span and Disability, 13 (1), 29–42.

Waldron, N. L., & McLeskey, J. (2010b). Establishing a collaborative school culture through comprehensive school reform. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 20 (1), 58–74.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, Østre Stationsvej 33, 5000, Odense C, Denmark

Anthoula Kefallinou, Simoni Symeonidou & Cor J. W. Meijer

Department of Education, University of Cyprus, P.O. Box 20537, 1678, Nicosia, Cyprus

Simoni Symeonidou

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anthoula Kefallinou .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The development of the article was supported by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

About this article

Kefallinou, A., Symeonidou, S. & Meijer, C.J.W. Understanding the value of inclusive education and its implementation: A review of the literature. Prospects 49 , 135–152 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09500-2

Download citation

Published : 07 September 2020

Issue Date : November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09500-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Inclusive education

- Academic outcomes

- Social inclusion

- Inclusive practice

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Virtual Library

- Editorial Board Member

- Write For Us

- Terms & Conditions

- Refund Policy

- Privacy Policy

- April 26, 2021

- Posted by: rsispostadmin

- Category: IJRISS

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) | Volume V, Issue III, March 2021 | ISSN 2454–6186

Inclusive Education: A Literature Review on Definitions, Attitudes and Pedagogical Challenges

Tebatso Namanyane, Md Mirajur Rhaman Shaoan Faculty of Education Southwest University China

Abstract: This paper on inclusive education explores several diverse viewpoints from various scholars in different contexts on the concepts of inclusive education in an effort to reach the common understanding of the same this concept. The attitudes section is addressed from the perspectives of pupils, educators, and the society (parents), and it further explore the dilemmas that teachers and students with disabilities face in modern education systems. The instructional approaches focusing on how teachers plan and execute lessons with diverse students’ aptitudes from literature are also levelheadedly outlined. In conclusion, it included a broad overview focused on two models, social and medical models on which this paper is primarily based.

Key words: Inclusive Education, Attitudes, Pedagogical Challenges

I. INTRODUCTION There are several terms in the field of education that are interpreted differently depending on the reason for which they are meant. Others have been given meanings that are globally recognized, while others are interpreted differently based on the varying reasons and factors affecting them, including religion and regions, history, values, race, and resource limitations. The present paper is intended to discuss an interesting educational topic which has intrigued scholars across the globe due to its arguable definitions from different perspectives. It will also have a more comprehensive but remarkably different interpretation of these core tenets as proposed in the topic specified above, Inclusive Education: A Literature Review on Definitions, Attitudes and Pedagogical Challenges. Education is a full process of training a new generation who is ready to participate in civic life and is also a vital link in the process of human social production experience to be carried out, with special regard to the process of school education for school-age infants, young people and retired people. Generally, all things that will improve human intelligence and skills and affect people’s moral character as considered as part of education. In a narrow sense, it is primarily schooling, which is characterized as the practice of educators to impact the mind and body of the learner intentionally, purposefully and systematically according to the requirements of a specific community or class to develop them as persons they want to be. Aristotle defines education as the way to prepare a man to achieve his mission by exercising all the faculties to the fullest degree as a citizen of society.

- DOI: 10.20489/intjecse.722380

- Corpus ID: 218795647

The development of inclusive education practice: A review of literature

- N. Alzahrani

- Published in International Journal of… 30 June 2020

- Education, Philosophy

10 Citations

The implementation of inclusive education in indonesia: challenges and achievements, organizational and pedagogical conditions for the educational process implementation within the inclusive education in the republic of kazakhstan, does professional development effectively support the implementation of inclusive education a meta-analysis, special education and general education teacher perceptions of collaborative teaching responsibilities and attitudes towards an inclusive environment in jordan, implementation of inclusive education in indonesian regular school, reconnoitering teachers' perception about inclusive education at quetta city baluchistan, framing the inclusion of students with visual impairment in the regular schools of punjab: efforts and challenges, task-oriented training effect on promoting motor skills and daily physical activities in learners with musculoskeletal impairment, decision‐making modes regarding the inclusive dilemmas of students with educational challenges in mainstream classrooms, science mapping on education, an approach from scopus database in 2022, 92 references, making education for all inclusive: where next, developing inclusive education systems: what are the levers for change, the impact of research on developments in inclusive education.

- Highly Influential

- 11 Excerpts

The influence of teaching experience and professional development on Greek teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion

The education for all and inclusive education debate: conflict, contradiction or opportunity, educational psychology and the effectiveness of inclusive education/mainstreaming., ideologies and utopias: education professionals' views of inclusion, inclusive education in the gulf cooperation council, an empirical study on teachers' perceptions towards inclusive education in malaysia., preparing teachers for inclusive education: some reflections from the netherlands, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Review of Literature: Inclusive Education

This brief review of relevant literature on inclusive education forms a component of the larger Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report delivered by the Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE) team to JFA Purple Orange in October, 2020.

Suggested citation for full evaluation report:

Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Bissaker, K., Carson, K. L., Davidson, J., & Walker, P. M. (2020). Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report. Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE), Flinders University.

https://sites.flinders.edu.au/rise

Introduction

Inclusive education has featured prominently in worldwide educational discourse and reform efforts over the past 30 years (Berlach & Chambers, 2011; Forlin, 2006). Inclusive schools are critical to providing a strong foundation for young people with disabilities to access, participate in and contribute to their communities and lead fulfilling lives (Hehir et al., 2016). Schools also represent a key condition for the development of thriving, inclusive communities for all citizens. Yet, as reflected in submissions to the current Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, and consistent with recent South Australian reports (Parliament of South Australia, 2017; Walker, 2017), many students living with disability (and their families) continue to report negative experiences of education. While progress has been made, traditional educational structures and practices often run counter to inclusive goals (Slee, 2013), and inconsistencies occur between theory and policy and the implementation of inclusive principles and practices in schools (Carrington & Elkins, 2002; Graham & Spandagou, 2011). In addition, both preservice and practicing teachers consistently report feeling underprepared to teach students with disabilities and special educational needs (Jarvis, 2019; OECD, 2019).

Despite legislation and policy imperatives related to inclusive education, there remains a lack of consensus in the field about the definition of inclusion and associated models of inclusive practice (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; Kinsella, 2020). Multiple conceptualisations of inclusion and theoretical approaches to fostering inclusion in schools may contribute to confusion and uncertainty for educators and policymakers. With schools facing growing accountability and teachers expected to educate an increasingly diverse student population (Anderson & Boyle, 2015), it is vital that the concept of inclusive education is demystified for practitioners. Against this backdrop, initiatives such as the Inclusive School Communities (ISC) project that aim to deepen understandings of inclusion and increase the capacity of school communities to provide an inclusive education, are particularly important.

Inclusive Education

Inclusive education is based on a philosophy that stems from principles of social justice, and is primarily concerned with mitigating educational inequalities, exclusion, and discrimination (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Waitoller & Artiles, 2013). Although inclusion was originally concerned with ‘disability’ and ‘special educational needs’ (Ainscow et al., 2006; Van Mieghem et al., 2020), the term has evolved to embody valuing diversity among all students, regardless of their circumstances (e.g., Carter & Abawi, 2018; Thomas, 2013). Among interpretations of inclusion, common themes include fairness, equality, respect, diversity, participation, community, leadership, commitment, shared vision, and collaboration (Booth, 2012; McMaster, 2015). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), to which Australia is a signatory, defines inclusive education as:

. . . a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences. (United Nations, 2016, para 11)

Consistent with this definition, inclusive education now generally refers to the process of addressing the learning needs of all students, through ensuring participation, achievement growth, and a sense of belonging, enabling all students to reach their full potential (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). Inclusion is concerned with identifying and removing potential barriers to presence (attendance, access), meaningful participation, growth from an individual starting point, and feelings of connectedness and belonging for all students and community members, with a focus on those at particular risk of marginalisation or exclusion (Ainscow et al., 2006; Forlin et al., 2013).

Critically, the view of inclusion described above moves beyond considerations of the physical placement of a student in a particular setting or grouping configuration. That is, while physical access to a mainstream school environment is essential to maintain the rights of students living with disabilities to access education “on the same basis” as their peers (consistent with legislation and human rights principles), it is not sufficient to ensure inclusion. Rather, inclusion can be considered a multi-faceted approach involving processes, practices, policies and cultures at all levels of a school and system (Booth & Ainscow, 2011). Inclusive education is responsive to each child and promotes flexibility, rather than expecting the child to change in order to ‘fit’ rigid schooling structures. The latter approach reflects integration, and inclusion is also inconsistent with segregation, in which children with disabilities are routinely educated separately from others.

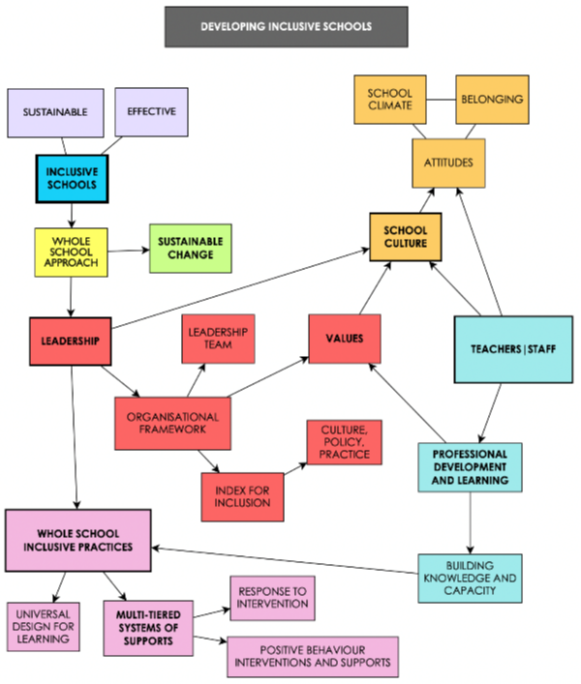

Considerable research has focused on the implementation of inclusive school processes, practices and cultures that are sustainable over time. Although a number of frameworks to achieve sustainable inclusive practice have been proposed, key elements are consistent across approaches and well supported by research (Booth & Ainscow 2011; Azorín & Ainscow, 2020). These interconnected elements are summarised in Figure 1 and considered fundamental to the process of achieving whole-school (and systemic) cultural change towards more inclusive ways of working. Of particular relevance to the Inclusive School Communities project are the concepts of a whole school approach, leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and multi-tiered models of inclusive practice.

Inclusion as a Whole School Approach

Adopting a whole of school approach to inclusive education is fundamental to ensure efficacy and sustainability (Read et al., 2015). The process of developing inclusive schools is complex and multi-faceted, requiring time, commitment, ongoing reflection, and sustained effort. For inclusion to truly take root in schools, changes must be made from the inside out; a strong foundation must be built from inclusive school values, committed leadership, and shared vision amongst staff to support whole school structural reforms to policy, pedagogy, and practice (Ekins & Grimes, 2009). Whilst challenging, “it is necessary to unsettle default modes of operation” in schools (Johnston & Hayes, 2007, p.376), as inclusive education requires new, more efficient and effective ways of supporting student participation and achievement. This is made possible by implementing flexible, planned whole school support structures, such as multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), where teachers work collaboratively with specialist staff to identify, monitor, and support students requiring varying levels and types of intervention at different times, and for different purposes (Sailor, 2017; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). This contrasts to the more traditional, ‘categorical’ and segregated approach of general educators referring identified students with additional needs to special educators, to devise and administer further education in isolation from the regular classroom (Sailor, 2017).

Figure 1. Interconnected elements in sustainable inclusive education, derived from research.

Even at the classroom level, inclusive planning and teaching practices must be supported by school policies, practices, and culture in order to be sustainable (Sailor, 2017). Barriers to inclusive classroom practice can include lack of effective professional learning and support for teachers; teachers’ lack of willingness to include students with particular needs; attitudes that are inconsistent with inclusive practices; teacher education that fails to address concerns about inclusion; and, a lack of accountability for the implementation of inclusive teaching practices (Forlin & Chambers, 2011; Forlin et al., 2008; van Kraayenoord et al., 2014). Addressing each of these relies on targeted, coordinated support. The complexity of embedding inclusive practices such as differentiated instruction or Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into classroom work is often underestimated, and these practices have the greatest chance of becoming embedded when they are reinforced by a shared vision and collaborative effort (McMaster, 2013; Sailor, 2015; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2017).

Sustainable, whole school change cannot be achieved via focus on a single element of inclusion in isolation, as components do not function in isolation. Rather, the core elements of inclusion including leadership, school culture, building staff capacity, and inclusive practices are parts of an interdependent system. Hence, key elements of inclusion must be considered collectively and accounted for in advanced planning to ensure they function harmoniously and are integrated into the developing inclusive fabric of the school (Alborno & Gaad, 2014).

Leadership for Inclusion

The importance of leadership for determining the success of school reforms or changes to practice is well established in the literature (McMaster & Elliot, 2014; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). Becoming a more inclusive school often requires significant shifts in school values, culture, practices, and organisational systems; thus, leadership is critical to ensuring sustainable inclusive change in schools (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). School leaders are highly influential figures whose values, beliefs, and actions directly affect the culture of the school, expectations of staff, and school operations (Slater, 2012; Wong & Cheung, 2009). It is critical that school leaders are committed to embodying inclusive principles, establishing and modelling a standard of behaviour that promotes the development of inclusion within the school community.

Organisational change on the scale often required for inclusion requires leadership across multiple levels (Jarvis et al., 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2008). It is likely to be most effective when facilitated through models of distributed leadership across roles and levels within a school, and when the case for change is underpinned by a broader, shared vision specifically related to student outcomes (Harris, 2013). Research has established the relationship between distributed leadership practices and the implementation of effective, inclusive school practices (Miškolci et al., 2016; Mullick et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2008; Sharp et al., 2020). Leaders should consider utilising inclusive styles of management, replacing hierarchical structures with leadership teams (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015). Effective school leadership enables shared responsibility, vision, and consistency within the school community, which is vital for the successful implementation of inclusion (Poon- McBrayer & Wong, 2013).

Fostering Inclusive School Cultures

Developing an inclusive school culture is a fundamental component of developing sustainable inclusion in schools (Dyson et al., 2004; McMaster, 2013). The culture of a school is made up of the shared values, attitudes, and beliefs of the school community (Booth, 2012). Transitioning to a truly inclusive culture requires close attention to attitudes and general support of the inclusive values being adopted, particularly by staff, but also by students and the broader school community (Dyson et al., 2004; Forlin & Chambers, 2011).

A whole school approach to inclusion prompts a school to reflect on and embrace values based on inclusive principles, such as equality, diversity, and respect. This process cannot be imposed, but should be a collaborative exercise with school leaders and staff, to ensure any pedagogical philosophies or practices based on outdated ideas or past assumptions are not operating by default (Johnston & Hayes, 2007; Schein, 2004). Evaluating and redefining existing school values also requires professional learning, to facilitate a collective reconceptualisation of inclusion specific to the unique context of the school; the meaning, aims, and expectations of inclusion must be clarified for the school community, to encourage a shared understanding, vision, and responsibility for supporting the inclusive changes unfolding within the school (Horrocks et al., 2008; Symes & Humphrey, 2011). Finally, it is vital that school policies and practices are regularly revised, to ensure that they reinforce the inclusive values and culture of the school; otherwise, they can act as a potential barrier to the development of sustainable whole school inclusion (Dybvik, 2004; McMaster, 2013).

Building Teachers’ Capacity for Inclusive Practice

Building the knowledge and capacity of teachers and other school staff is crucial to developing sustainable inclusion in schools. The evolution of an inclusive school culture depends on aligning the attitudes and behaviour of staff (McMaster, 2015). Teachers must be knowledgeable about how inclusive education has progressed over time, particularly how the meaning of inclusion has changed and what it means in their school context. Understanding the concepts and values behind inclusion can help teachers appreciate its significance, prompting reflection of their own practice and how they see their students (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Skidmore, 2004). This can allow any unhelpful assumptions or beliefs that may have been unconsciously informing their teaching practice, particularly in relation to students living with disability, to be challenged and revised (Ashby, 2012; Ashton & Arlington, 2019).

While attention to attitudes, values, and broad understandings is fundamental, the goals of inclusion will only be achieved when principles are consistently enacted in daily classroom practice. At the classroom level, inclusion relies on teachers’ willingness and capacity to apply evidence-informed inclusive practices, such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Differentiated Instruction (Van Mieghem et al., 2020). UDL is a planning framework for learning activities designed to maximise curriculum accessibility for all students by offering multiple opportunities for engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2018; Sailor, 2015). Differentiated Instruction (DI) is a holistic framework of interdependent principles and practices that enables teachers to design learning experiences to address variation in students’ readiness, interests and learning preferences (Tomlinson, 2014). UDL is primarily focused on inclusive task design, although the model has been expanded in recent years to include greater attention to pedagogy. Differentiation encompasses elements of planning (clear, concept-based learning objectives; formative assessment to inform proactive decision-making for diverse students), teaching (strategies to differentiate by readiness, interest and learning preference; ensuring respectful tasks and ‘teaching up’), and learning environment (flexible grouping, classroom management, establishing an inclusive culture) (Jarvis, 2015; Tomlinson, 2014).

The application of UDL and DI principles and practices by skilled teachers enables diverse students to access curriculum content in multiple ways (Kozik et al., 2009; McMaster, 2013), at appropriate levels of challenge and support to ensure learning growth, and in ways that support motivation, engagement, and feelings of connection and belonging (Beecher & Sweeney, 2008; Callahan et al., 2015; van Kraayenoord, 2007; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). These complementary frameworks apply to all students and define general, flexible classroom practices that also reduce the need for individualised adjustments for students with identified disabilities and specialised learning needs. However, in inclusive classrooms, teachers must also develop the knowledge and skills to make and implement reasonable adjustments and accommodations that enable students with identified disabilities and more complex needs to engage with curriculum and assessment ‘on the same basis’ as their peers, as defined within the Disability Standards for Education (Davies et al., 2016).

While inclusive teaching and classroom practices are non-negotiable, the challenge for some teachers to master the necessary skills and achieve the significant shift away from traditional teaching practices is often underestimated (Dixon et al., 2014; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). It is well-documented that teachers often find it difficult to apprehend both the conceptual and practical tools of DI and to embed differentiated practices into their daily work (Dack, 2019), particularly when they are not adequately resourced or supported to do so (Black-Hawkins & Florian, 2012; Brigandi et al., 2019; Fuchs et al., 2010; Mills et al, 2014). Perhaps related to teachers’ perceived lack of competence and confidence, the past 5-10 years have seen an enormous increase in the employment of teacher aides to work alongside students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms, despite limited evidence for its effectiveness and often in the context of inadequate planning and oversight (e.g., Sharma & Salend, 2016).

Engagement in targeted professional learning (PL) is fundamental to supporting the shift towards inclusive teaching. Yet, traditional approaches to PL have been criticised for a lack of systematic evaluation and inadequate adherence to principles of effectiveness (Avalos, 2011; Merchie et al., 2018). Research on effective professional learning for teachers has established common principles and practices that are associated with changes in practice, and these also align with teachers’ stated preferences (Walker et al., 2018). These include:

- professional learning is embedded in teachers’ own work contexts, and requires teachers to engage with content that is highly relevant to their daily practice, and closely linked to student learning (Desimone, 2009; Easton, 2008; Spencer, 2016; Van den Bergh et al., 2014);

- professional learning enables teachers to learn together with colleagues, such as in communities of practice (Gore et al., 2017; Voelkel & Chrispeels, 2017);

- professional learning activities are supported by robust school leadership and linked to broader school values and goals (Carpenter, 2015; Frankling et al., 2017; Sharp et al., 2020; Tomlinson et al., 2008; Whitworth & Chiu, 2015);

- professional learning is provided over extended periods, is led by facilitators with expert knowledge, and includes timely follow up activities such as mentoring and coaching to embed changes in practice (Desimone & Pak, 2017; Grierson & Woloshyn, 2013; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015).

Multi-tiered Approaches to Whole School Inclusive Practice

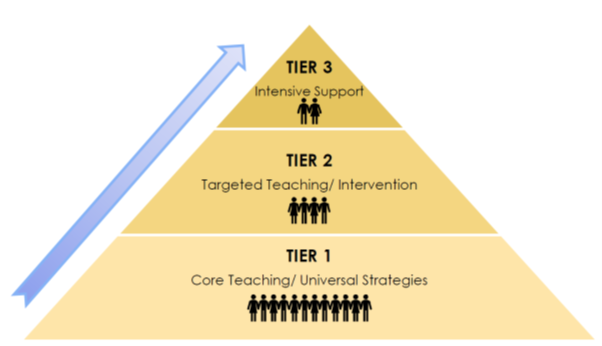

Multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) is an overarching term for a whole school inclusive framework that can be used to structure the flexible, timely distribution of resources to support students depending on their level of need (Sailor, 2017). As reflected in the generic depiction of MTSS in Figure 2, models generally utilise three tiers of intervention and teaching, where the intensity of the support is increased with each level or tier (McLeskey et al, 2014; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). Tier 1 includes core differentiated instruction and universal, evidence-based strategies for support that all students in the class receive. Tier 2 provides additional, targeted support to certain students for a specified purpose and period of time, usually in a small group format, while Tier 3 represents the most intensive and individualised support (Webster, 2016). The MTSS approach requires assessing all students regularly to assist in the early identification of needs requiring additional support, to enable prompt delivery of targeted interventions (McLeskey et al., 2014). MTSS is concerned with supporting the holistic development of students, by targeting their academic progress, behaviour, and socio-emotional well- being (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017).

When implemented with fidelity, MTSS is an effective whole school inclusive framework as teachers, therapists, and other support staff work collaboratively to assess, monitor, and plan interventions to support students (Sailor, 2017). Student progress is frequently monitored and data are evaluated by the support team to determine whether alternative interventions are required. MTSS additionally encourages the use of evidence-based practices to be implemented across the tiers of support. Some common examples of MTSS include Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behaviour Interventions and Supports (PBIS) (Webster, 2016). RTI is focused on supporting students academically, while PBIS is concerned with emphasising behavioural expectations in a positive manner, naturally supporting the social and emotional development of students. MTSS models have also been applied in whole-school mental health promotion, prevention and intervention (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017) and inclusive approaches to academic talent development for more advanced students (Jarvis, 2017).

MTSS approaches to contemporary inclusive practice stand in contrast to traditional, categorical models whereby students were either ‘in’ or ‘out’ of special education services. The focus is on determining and responding to what students need when they need it, as opposed to focusing on a specific diagnosis or inflexible program options. In the MTSS framework, the tiers do not represent students or their placement, but the flexible suite of supports and interventions that may be provided. The implementation of MTSS approaches fundamentally reconceptualises the role of the classroom teacher, who must work collaboratively with specialist staff and other professionals to define and address individual student needs in ongoing ways, rather than relying on a specialist teacher or even a teacher aide to take responsibility for the education of students with identified special needs. While MTSS requires substantial changes to school operations (and must therefore be supported by leadership and culture in deliberate, coordinated ways), the general framework provides an organisation and structure to support the development of sustainable, contemporary inclusive schools (McLeskey et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework.

Conclusion

Ultimately, developing sustainable and effective inclusion in schools is a challenging but worthwhile undertaking, requiring shared vision, commitment, ongoing reflection, and patience. Changes in practice, particularly in teachers’ daily planning and pedagogy, take time and will be supported by ongoing, well designed and embedded professional learning in the context of strong leadership and an inclusive school culture. By utilising a whole school approach, key areas including leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and coordinated frameworks for inclusive practice, can be considered collectively and planned for in advance.

References

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organizational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14 (4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. Routledge.

Alborno, N., & Gaad, E. (2014). Index for Inclusion: A framework for school review in the United Arab Emirates. British Journal of Special Education, 41 (3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12073

Anderson, J., & Boyle, C. (2015). Inclusive education in Australia: Rhetoric, reality and the road ahead. Support for Learning, 30 (1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12074

Ashby, C. (2012). Disability studies and inclusive teacher preparation: A socially just path for teacher education. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37 (2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F154079691203700204

Ashton, J. R., & Arlington, H. (2019). My fears were irrational: Transforming conceptions of disability in teacher education through service learning. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 15 (1), 50–81.

Askell-Williams, H., & Koh, G. (2020). Enhancing the sustainability of school improvement initiatives. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1767657

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

Beecher, M., & Sweeney, S. M. (2008). Closing the achievement gap with curriculum enrichment and differentiation: One school’s story. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19 (3), 502–530. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-815

Berlach, R. G., & Chambers, D. J. (2011). Interpreting inclusivity: An endeavour of great proportions. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15, 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903159300

Black-Hawkins, K. & Florian, L. (2012). Classroom teachers’ craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8 (5), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709732

Booth, T. (2012). Creating welcoming cultures: The index for inclusion. Race Equality Teaching, 30 (2), 19–21. http://doi.org/10.18546/RET.30.2.07

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2011). Index for Inclusion: developing learning and participation in schools (3rd ed.). Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. http://www.csie.org.uk/resources/inclusion-index-explained.shtml

Brigandi, C., Gibson, C. M., & Miller, M. (2019). Professional development and differentiated instruction in an elementary school pull-out program: A gifted education case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42 (4), 362–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219874418

Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Oh, S., Azano, A. P., & Hailey, E. P. (2015). What works in gifted education: Documenting the effects of an integrated curricular/instructional model for gifted students. American Education Research Journal, 52, 137–167. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214549448

Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International Journal of Educational Management, 29 (5), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2014-0046

Carrington, S., & Elkins, J. (2002). Bridging the gap between inclusive policy and inclusive culture in secondary schools. Support for Learning, 17 (2), 51–57.

Carter, S., & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.5

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Davies, M., Elliott, S., & Cumming, J. (2016). Documenting support needs and adjustment gaps for students with disabilities: Teacher practices in Australian classrooms and on national tests. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20 (12), 1252–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1159256

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38 (3),181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Practice, 56 (1), 312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1241947

Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. A., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated instruction, professional development and teacher efficacy. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37 (2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353214529042

Dybvik, A. C. (2004). Autism and the inclusion mandate: What happens when children with severe disabilities like autism are taught in regular classrooms? Daniel knows. Education Next, 4 (1), 42–49.

Dyson, A., Farrell, P., Polat, F., Hutcheson, G., & Gallanaugh, F. (2004). Inclusion and pupil achievement. Department for Education and Skills.

Easton, L. B. (2008). From professional development to professional learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 89, 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170808901014

Ekins, A., & Grimes, P. (2009). Inclusion: Developing an Effective Whole School Approach. McGraw Hill Open University Press.

Forlin, C. (2006). Inclusive education in Australia ten years after Salamanca. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21 (3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173415

Forlin, C., & Chambers, D. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: Increasing knowledge but raising concerns. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39 (1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850

Forlin, C., Chambers, D. J., Loreman, T., Deppler, J., & Sharma, U. (2013). Inclusive education for students with disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice. The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. https://www.aracy.org.au/publicationsresources/command/download_file/id/246/filename/Inclusive_education_for_students_with_disability_-_A_review_of_the_best_evidence_in_relation_to_theory_and_practice.pdf73

Forlin, C., Keen, M., & Barrett. E. (2008). The concerns of mainstream teachers: Coping with inclusivity in an Australian context. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55 (3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120802268396

Frankling, T. W., Jarvis, J. M. & Bell. M. R. (2017). Leading secondary teachers’ understandings and practices of differentiation through professional learning. Leading and Managing, 23 (2), 72–86.

Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Stecker, P. M. (2010). The ‘blurring’ of special education in a new continuum of general education placements and services. Exceptional Children, 76 (3), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600304

Gore, J., Lloyd, A., Smith, M., Bowe, J., Ellis, H., & Lubans, D. (2017). Effects of professional development on the quality of teaching: Results from a randomised controlled trial of Quality Teaching Rounds. Teaching and Teacher Education, 68, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.007

Graham, L., & Spandagou, I. (2011). From vision to reality: Views of primary school principals on inclusive education in New South Wales, Australia. Disability & Society, 26 (2), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.544062

Grierson, A. L., & Woloshyn, V. E. (2013). Walking the talk: Supporting teachers’ growth with differentiated professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 39 (3), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.763143

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin Press

Harris, A. (2013). Distributed leadership: Friend or foe? Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 4 (5), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213497635

Hehir, T., Pascucci, S., & Pascucci, C. (2016). A summary of the evidence on inclusive education, Instituto Alana, 2. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596134.pdf

Horrocks, J. L., White, G., & Roberts, L. (2008). Principals' attitudes regarding inclusion of children with autism in Pennsylvania public schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1462–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0522-x

Jarvis, J. M. (2015). Inclusive Classrooms and Differentiation. In N. Weatherby-Fell (Ed.), Learning to Teach in the Secondary School (pp. 154–171). Cambridge University Press.

Jarvis, J. M. (2019). Most Australian teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/most-australian-teachers-feel-unpreparedto-teach-students-with-special-needs-119227

Jarvis, J. M., (2017). Supporting diverse gifted students. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, Inclusion and Engagement (3rd ed., pp. 308–329). Oxford University Press.

Johnston, K., & Hayes, D. (2007). Supporting students’ success at school through teacher professional learning: The pedagogy of disrupting the default modes of schooling. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11 (3), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110701240666

Kinsella, W. (2020). Organising inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (12), 1340–1356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1516820

Kozik, P., Cooney, B., Vinciguerra, S., Gradel, K., & Black, J. (2009). Promoting inclusion in secondary schools through appreciative inquiry. American Secondary Education, 38 (1), 77–91.

McLeskey, J., Waldron, N. L., Spooner, F., & Algozzine, B. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of effective inclusive schools: Research and practice. Taylor & Francis.

McMaster, C. (2013). Building inclusion from the ground up: A review of whole school re-culturing programmes for sustaining inclusive change. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 9 (2), 1–24.

McMaster, C. (2015). Inclusion in New Zealand: The potential and possibilities of sustainable inclusive change through utilising a framework for whole school development. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50 (2), 239–253.

McMaster, C., & Elliot, W. (2014). Leading inclusive change with the Index for Inclusion: Using a framework to manage sustainable professional development. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 29 (1), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0010-3

McMillan, J., & Jarvis, J. M. (2017). Supporting mental health and well-being: Promotion, prevention and intervention. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, inclusion and engagement (3rd ed., pp. 65–392). Oxford University Press.

Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2018). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33 (2), 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271003

Mills, M., Monk, S., Keddie, A., Renshaw, P., Christie, P., Geelan, D. & C. Gowlett, C. (2014). Differentiated learning: From policy to classroom. Oxford Review of Education, 40 (3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.911725

Miškolci, J., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2016). Teachers' perceptions of the relationship between inclusive education and distributed leadership in two primary schools in Slovakia and New South Wales (Australia). Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18 (2), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2016-001

Mullick, J., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. (2013). School teachers' perception about distributed leadership practices for inclusive education in primary schools in Bangladesh. School Leadership & Management, 33 (2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2012.723615

OECD (2019). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en.

Parliament of South Australia. (2017). Report of the select committee on access to the South Australian Education System for students with a disability. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-05/apo-nid94396.pdf

Poon-McBrayer, K., & Wong, P. (2013). Inclusive education services for children and youth with disabilities: Values, roles and challenges of school leaders. Children and Youth Services Review, 35 (9), 1520–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.06.009

Read, K., Aldridge, J., Ala’i, K., Fraser, B., & Fozdar, F. (2015). Creating a climate in which students can flourish: A whole school intercultural approach. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 11 (2), 29–44. https://doi.org/1710-2146

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44 (5), 635–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. (2019). Issues Paper: Education and Learning. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-07/Issues-paper-Education-Learning.pdf

Sailor, W. (2015). Advances in schoolwide inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 36, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514555021

Sailor, W. (2017). Equity as a basis for inclusive educational systems change. The Australasian Journal of Special Education, 41 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.12

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Sharma, U., & Salend, S. (2016). Teaching assistants in inclusive classrooms: A systematic analysis of the international research. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41 (8), 118–134.

Sharp, K., Jarvis, J. M., & McMillan, J. M. (2020). Leadership for differentiated instruction: Teachers' engagement with on-site professional learning at an Australian secondary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (8), 901–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1492639

Skidmore, D. (2004). Inclusion: The dynamic of school development. McGraw-Hill Education.

Slater, C. L. (2012). Understanding principal leadership: An international perspective and a narrative approach. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39 (2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210390061

Slee, R. (2013). How do we make inclusive education happen when exclusion is a political predisposition? International Journal of Inclusive Education: Making Inclusive Education Happen: Ideas for Sustainable Change, 17 (8), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.602534

Spencer, E. J. (2016). Professional learning communities: Keeping the focus on instructional practice. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 52 (2), 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2016.1156544

Stegemann, K., & Jaciw, A. (2018). Making it logical: Implementation of inclusive education using a logic model framework. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 16 (1), 3–18.

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2011). School factors that facilitate or hinder the ability of teaching assistants to effectively support pupils with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11 (3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01196.x

Thomas, G. (2013). A review of thinking and research about inclusive education policy, with suggestions for a new kind of inclusive thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 39 (3), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.652070

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Murphy, M. (2015). Leading for differentiation: Growing teachers who grow kids. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C.A., Brimijoin, K., & Narvaez, L. (2008). The differentiated school: Making revolutionary changes in teaching and learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Van Den Bergh, L., Ros, A., & Beijaard, D. (2014). Improving teacher feedback during active learning: Effects of a professional development program. American Educational Research Journal, 51 (4), 772–809. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531322

van Kraayenoord, C. E. (2007). School and classroom practices in inclusive education in Australia. Childhood Education, 83 (6), 390–394, https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2007.10522957

van Kraayenoord, C. E., Waterworth, D., & Brady. T. (2014). Responding to individual differences in inclusive classrooms in Australia. Journal of International Special Needs Education, 17 (2), 48–59.

Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26 (6), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

Voelkel, R. H., Jr., & Chrispeels, J. H. (2017). Understanding the link between professional learning communities and teacher collective efficacy. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28, 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1299015

Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83 (3), 319–356. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483905

Walker, P. M., Carson, K. L., Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Noble, A. G., Armstrong, D., . . . Palmer, C. (2018). How do educators of students with disabilities in specialist settings understand and apply the Australian Curriculum framework? Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.13

Webster, A. (2016). Utilising a leadership blueprint to build the capacity of schools to achieve outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. In G. Johnson & N. Dempster (Eds.), Leadership in diverse learning contexts (pp. 109–127). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28302-9_6

Whitworth, B. A., & Chiu, J. L. (2015). Professional development and teacher change: The missing leadership link. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26 (2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9411-2

Inclusive School Communities Project Phone: (08) 8373 8333 Email: [email protected] Address: 104 Greenhill Road, Unley SA 5061

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Inclusive Education: Literature Review

The education of disabled children never received such amount of consideration and special efforts by government and non-government agencies in past as in present days. The attitude of the community in general and the attitude of parents in particular towards the education of the disabled have undergone change with the development of society and civilization.

Related Papers

vatika sibal

Executive Summary In India, inclusive education for children with disability has only recently been accepted in policy and in principle. In light of supportive policy and legislation, the present paper argues for individual initiative on part of an institution and colleges to implement programmes of inclusive education for children with disabilities in their classrooms. The paper provides guidelines in a generalized mode that institutions can follow to initiate such programmes. In this context, this paper argues for individual initiative on part of institutions to extend facilities for children with disabilities within their regular school settings. The paper further provides guidelines that institutions can adopt to set up inclusive education practices. The guidelines were derived from an empirical study which entailed examining prevalent practices and introducing inclusion in a regular institution setting. It is suggested that institutions can implement inclusive education programmes if they are adequately prepared, are able to garner support of all stakeholders involved in the process and have basic resources to run the programmes. The guidelines also suggest ways in which curriculum adaptations, teaching methodology and evaluation procedures can be adapted to suit needs of students with special needs. Issues of role allocation and seeking support of parents and peers are also dealt with. The recommendations that intuitions can adopt to implement inclusive education programmes for students with special needs within their regular set ups. The recommendations have been presented in a generalized mode to permit institute to interpret, modify and adapt the guidelines based on their individual needs and characteristics. It is pertinent those institutes that initiate such programmes assess their strengths and weaknesses at the outset and ensure adequate cooperation from the school management as well as the administrative and teaching staff. It is important to state here that an inclusive education programme does not require resource overload or elaborate preparations. With policy support, opportunities for training of teachers and cooperation from parents and the peer group, inclusive practices can be effectively adopted by any school. Clarity of vision, commitment to the goal of inclusion, and a perceptible understanding of the nuances involved in such an initiative are central to the success of the programme. Emotional commitment to inclusion emerges when the intellectual understanding of the concept goes through a democratic visioning process involving all the stakeholders expressing their opinions and feelings.

ankur madan

Research Anthology on Inclusive Practices for Educators and Administrators in Special Education

Shekh Farid

BRAC, a leading international development organization, has been working to ensure the rights of persons with disabilities to education through its inclusive education program. This article discusses the BRAC approach in Bangladesh and aims to identify its strategies that are effective in facilitating inclusion. It employed a qualitative research approach where data were collected from students with disabilities, their parents, and BRAC's teachers and staffs using qualitative data collection techniques. The results show that the disability-inclusive policy and all other activities are strongly monitored by a separate unit under BRAC Education Program (BEP). It mainly focuses on sensitizing its teachers and staff to the issue through training, discussing the issue in all meetings and ensuring effective use of a working manual developed by the unit. Group-based learning and involving them in income generating activities were also effective. The findings of the study would be usefu...

Shonazar Botirov

This article describes the introduction of inclusive education, what it is, about children with disabilities, as well as the positive and negative aspects of inclusive education.

Rajendra KR

Inclusive Education on Children with Learning Disabilities

Arien Arien