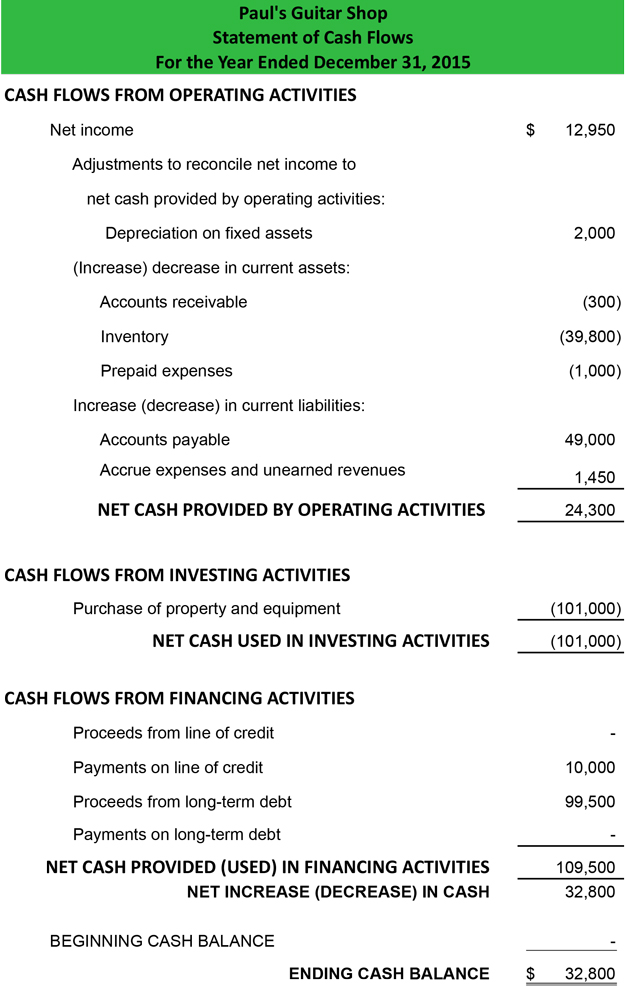

Statement of Cash Flows Indirect Method

Home › Accounting › Financial Statements › Statement of Cash Flows Indirect Method

- What is the Statement of Cash Flows Indirect Method?

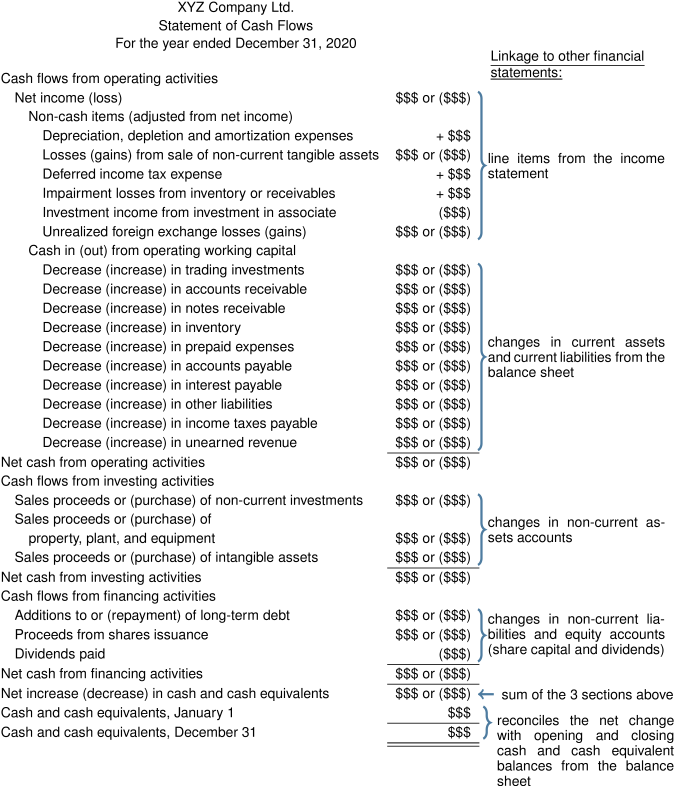

The statement of cash flows prepared using the indirect method adjusts net income for the changes in balance sheet accounts to calculate the cash from operating activities. In other words, changes in asset and liability accounts that affect cash balances throughout the year are added to or subtracted from net income at the end of the period to arrive at the operating cash flow.

The operating activities section is the only difference between the direct and indirect methods. The direct method lists all receipts and payments of cash from individual sources to compute operating cash flows. This is not only difficult to create; it also requires a completely separate reconciliation that looks very similar to the indirect method to prove the operating activities section is accurate.

Companies tend to prefer the indirect presentation to the direct method because the information needed to create this report is readily available in any accounting system. In fact, you don’t even need to go into the bookkeeping software to create this report. All you need is a comparative income statement . Let’s take a look at the format and how to prepare an indirect method cash flow statement.

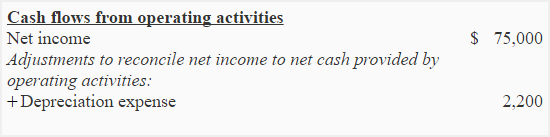

The indirect operating activities section always starts out with the net income for the period followed by non-cash expenses, gains, and losses that need to be added back to or subtracted from net income . These non-cash activities typically include:

- Depreciation expense

- Amortization expense

- Depletion expense

- Gains or Losses from sale of assets

- Losses from accounts receivable

The non-cash expenses and losses must be added back in and the gains must be subtracted.

The next section of the operating activities adjusts net income for the changes in asset accounts that affected cash. These accounts typically include:

- Accounts receivable

- Prepaid expenses

- Receivables from employees and owners

This is where preparing the indirect method can get a little confusing. You need to think about how changes in these accounts affect cash in order to identify what way income needs to be adjusted. When an asset increases during the year, cash must have been used to purchase the new asset. Thus, a net increase in an asset account actually decreased cash, so we need to subtract this increase from the net income. The opposite is true about decreases. If an asset account decreases, we will need to add this amount back into the income. Here’s a general rule of thumb when preparing an indirect cash flow statement:

Asset account increases : subtract amount from income Asset account decreases : add amount to income

The last section of the operating activities adjusts net income for changes in liability accounts affected by cash during the year. Here are some of the accounts that usually are used:

- Accounts payable

- Accrued expenses

Get ready. If you weren’t confused by the assets part, you might be for the liabilities section. Since liabilities have a credit balance instead of a debit balance like asset accounts, the liabilities section works the opposite of the assets section. In other words, an increase in a liability needs to be added back into income. This makes sense. Take accounts payable for example. If accounts payable increased during the year, it means we purchased something without using cash. Thus, this amount should be added back. Here’s a basic tip that you can use for all liability accounts:

Liability account increases : add amount from income Liability account decreases : subtract amount to income

All of these adjustments are totaled to adjust the net income for the period to match the cash provided by operating activities.

It might be helpful to look at an example of what the indirect method actually looks like.

As you can see, the operating section always lists net income first followed by the adjustments for expenses, gains, losses, asset accounts, and liability accounts respectively.

Although most standard setting bodies prefer the direct method, companies use the indirect method almost exclusively. It’s easier to prepare, less costly to report, and less time consuming to create than the direct method. Standard setting bodies prefer the direct because it provides more information for the external users, but companies don’t like it because it requires an additional reconciliation be included in the report. Since the indirect method acts as a reconciliation itself, it’s far less work for companies to simply prepare this report instead.

Accounting & CPA Exam Expert

Shaun Conrad is a Certified Public Accountant and CPA exam expert with a passion for teaching. After almost a decade of experience in public accounting, he created MyAccountingCourse.com to help people learn accounting & finance, pass the CPA exam, and start their career.

- Financial Accounting Basics

- Accounting Principles

- Accounting Cycle

- Financial Statements

- Income Statement

- Multi Step Income Statement

- Other Comprehensive Income

- Extraordinary Items

- Statement of Stockholders Equity

- Balance Sheet

- Classified Balance Sheet

- Statement of Financial Position

- Cash Flow Statement

- Cash Flows – Direct Method

- Cash Flows – Indirect Method

- Statement of Retained Earnings

- Pro Forma Financial Statements

- Financial Ratios

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Corporate Finance

How To Use the Indirect Method To Prepare a Cash Flow Statement

Investopedia / Eliana Rodgers

What Is the Indirect Method?

The indirect method is one of two accounting treatments used to generate a cash flow statement . The indirect method uses increases and decreases in balance sheet line items to modify the operating section of the cash flow statement from the accrual method to the cash method of accounting.

The other option for completing a cash flow statement is the direct method , which lists actual cash inflows and outflows made during the reporting period. The indirect method is more commonly used in practice, especially among larger firms.

Key Takeaways

- Under the indirect method, the cash flow statement begins with net income on an accrual basis and subsequently adds and subtracts non-cash items to reconcile to actual cash flows from operations.

- The indirect method is often easier to use than the direct method since most larger businesses already use accrual accounting.

- The complexity and time required to list every cash disbursement—as required by the direct method—makes the indirect method preferred and more commonly used.

Understanding the Indirect Method

The cash flow statement primarily centers on the sources and uses of cash by a company, and it is closely monitored by investors, creditors, and other stakeholders. It offers information on cash generated from various activities and depicts the effects of changes in asset and liability accounts on a company's cash position.

The indirect method presents the statement of cash flows beginning with net income or loss, with subsequent additions to or deductions from that amount for non-cash revenue and expense items, resulting in cash flow from operating activities.

The indirect method is simpler than the direct method to prepare because most companies keep their records on an accrual basis.

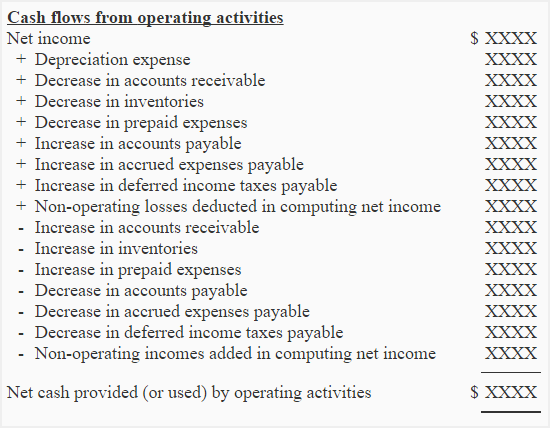

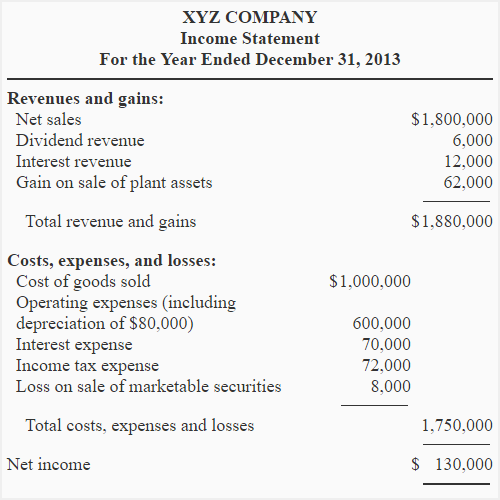

Example of the Indirect Method

Under the accrual method of accounting, revenue is recognized when earned, not necessarily when cash is received. If a customer buys a $500 widget on credit, the sale has been made but the cash has not yet been received. The revenue is still recognized in the month of the sale.

The indirect method of the cash flow statement attempts to revert the record to the cash method to depict actual cash inflows and outflows during the period. In this example, at the time of sale, a debit would have been made to accounts receivable and a credit to sales revenue in the amount of $500. The debit increases accounts receivable, which is then displayed on the balance sheet.

Under the indirect method, the cash flows statement will present net income on the first line. The following lines will show increases and decreases in asset and liability accounts, and these items will be added to or subtracted from net income based on the cash impact of the item.

In this example, no cash had been received but $500 in revenue had been recognized. Therefore, net income was overstated by this amount on a cash basis. The offset was sitting in the accounts receivable line item on the balance sheet. There would need to be a reduction from net income on the cash flow statement in the amount of the $500 increase to accounts receivable due to this sale. It would be displayed as "Increase in Accounts Receivable (500)."

Indirect Method vs. Direct Method

The cash flow statement is divided into three categories— cash flows from operating activities , cash flows from investing activities , and cash flows from financing activities . Although total cash generated from operating activities is the same under the direct and indirect methods, the information is presented in a different format.

Under the direct method, the cash flow from operating activities is presented as actual cash inflows and outflows on a cash basis, without starting from net income on an accrued basis. The investing and financing sections of the statement of cash flows are prepared in the same way for both the indirect and direct methods.

Many accountants prefer the indirect method because it is simple to prepare the cash flow statement using information from the other two common financial statements, the income statement and balance sheet . Most companies use the accrual method of accounting, so the income statement and balance sheet will have figures consistent with this method.

However, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) prefers companies use the direct method as it offers a clearer picture of cash flows in and out of a business. However, if the direct method is used, it is still recommended to do a reconciliation of the cash flow statement to the balance sheet.

The CPA Journal. " The Statement of Cash Flows Turns 30 ." Accessed Sept. 3, 2021.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Understanding-the-Cash-Flow-Statement-Color-fc25b41daf7d45e3a63fd5f916fbf9ee.png)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

17.3 Cash Flows from Operating Activities: The Indirect Method

Learning objectives.

At the end of this section, students should be able to meet the following objectives:

- Explain the difference in the start of the operating activities section of the statement of cash flows when the indirect method is used rather than the direct method.

- Demonstrate the removal of noncash items and nonoperating gains and losses in the application of the indirect method.

- Determine the effect caused by the change in the various connector accounts when the indirect method is used to present cash flows from operating activities.

- Identify the reporting classification for interest revenues, dividend revenues, and interest expense in creating a statement of cash flows and describe the controversy that resulted from this handling.

Question: As mentioned, most organizations do not choose to present their operating activity cash flows using the direct method despite preference by FASB. Instead, this information is shown within a statement of cash flows by means of the indirect method . How does the indirect method of reporting operating activity cash flows differ from the direct method?

Answer: The indirect method actually follows the same set of procedures as the direct method except that it begins with net income rather than the business’s entire income statement. After that, the three steps demonstrated previously are followed although the mechanical process here is different.

- Noncash items are removed.

- Nonoperational gains and losses are removed.

- Adjustments are made, based on the change registered in the various connector accounts, to switch remaining revenues and expenses from accrual accounting to cash accounting.

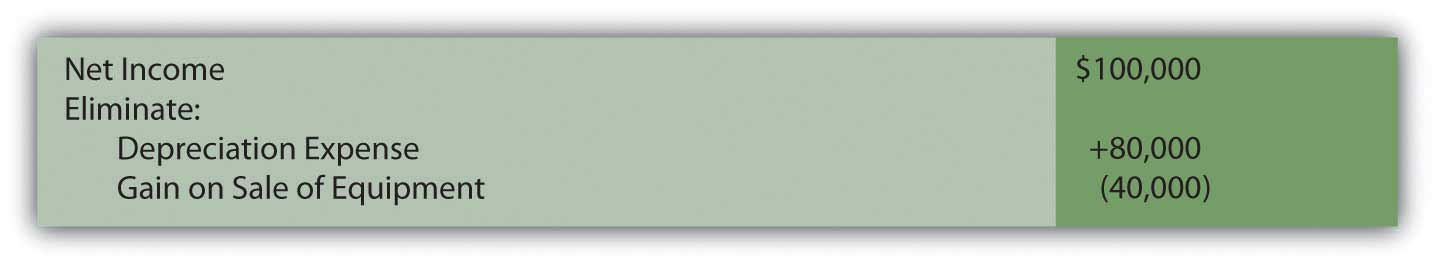

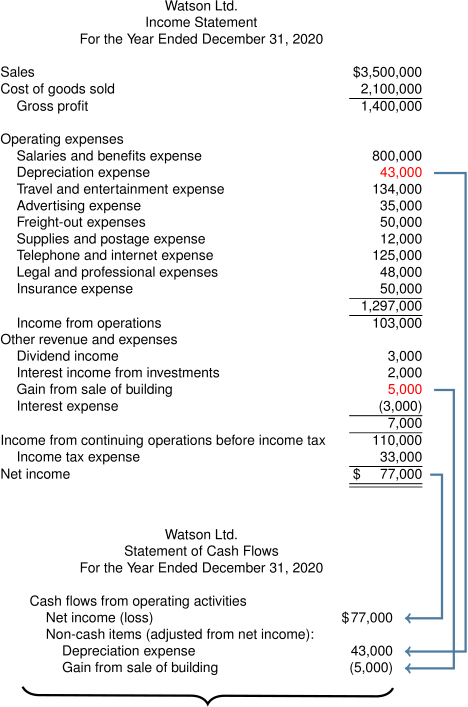

Question: In the income statement presented above for the Liberto Company, net income was reported as $100,000. That included depreciation expense (a noncash item) of $80,000 and a gain on the sale of equipment (an investing activity rather than an operating activity) of $40,000 . In applying the indirect method, how are noncash items and nonoperating gains and losses removed from net income?

Answer: Depreciation is an expense and, hence, a negative component of net income. To eliminate a negative, it is offset by a positive. Adding back depreciation serves to remove its impact from the reporting company’s net income.

The gain on sale of equipment also exists within reported income but as a positive figure. It helped increase profits this period. To eliminate this gain, the $40,000 amount must be subtracted. The cash flows resulting from this transaction came from an investing activity and not an operating activity.

In applying the indirect method, a negative is removed by addition; a positive is removed by subtraction.

Figure 17.7 Operating Activity Cash Flows, Indirect Method—Elimination of Noncash and Nonoperating Balances

In the direct method, these two amounts were simply omitted in arriving at the individual cash flows from operating activities. In the indirect method, they are both physically removed from income by reversing their effect. The impact is the same in the indirect method as in the direct method.

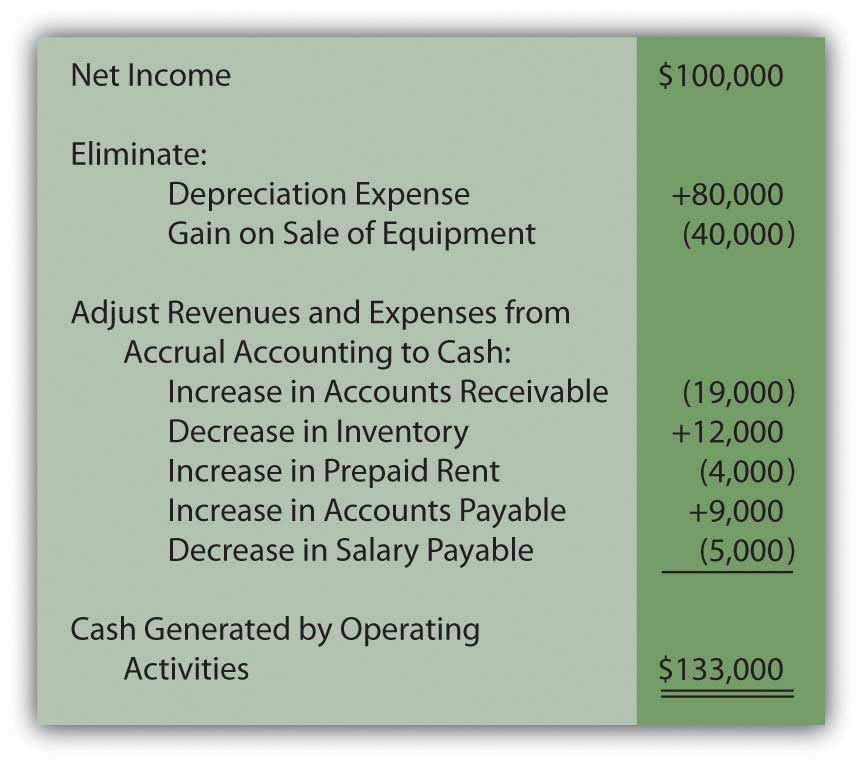

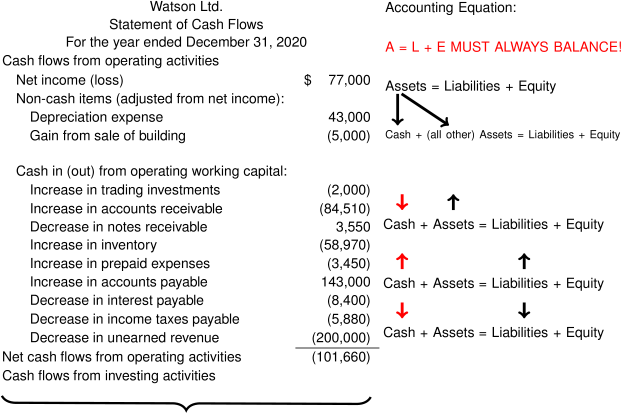

Question: After all noncash and nonoperating items are removed from net income, only the changes in the balance sheet connector accounts must be utilized to complete the conversion to cash. For Liberto, those balances were shown previously .

- Accounts receivable: up $19,000

- Inventory: down $12,000

- Prepaid rent: up $4,000

- Accounts payable: up $9,000

- Salary payable: down $5,000

Each of these increases and decreases was used in the direct method to turn accrual accounting figures into cash balances. That same process is followed in the indirect method . How are changes in an entity’s connector accounts reflected in the application of the indirect method?

Answer: Although the procedures appear to be different, the same logic is applied in the indirect method as in the direct method. The change in each of these connector accounts has an impact on the cash amount and it can be logically determined. However, note that the effect is measured on the net income as a whole rather than on individual revenue and expense accounts.

Accounts receivable increased by $19,000 . This rise in the receivable balance shows that less money was collected than the sales made during the period. Receivables go up because customers are slow to pay. This change results in a lower cash balance. Thus, the $19,000 should be subtracted in arriving at the cash flow amount generated by operating activities. The cash received was actually less than the figure reported for sales within net income. Subtract $19,000 .

Inventory decreased by $12,000 . A drop in the amount of inventory on hand indicates that less was purchased during the period. Buying less merchandise requires a smaller amount of cash to be paid. That leaves the balance higher. The $12,000 should be added. Add $12,000 .

Prepaid rent increased by $4,000 . An increase in any prepaid expense shows that more of the asset was acquired during the year than was consumed. This additional purchase requires the use of cash; thus, the balance is lowered. The increase in prepaid rent necessitates a $4,000 subtraction in the operating activity cash flow computation. Subtract $4,000 .

Accounts payable increased by $9,000 . Any jump in a liability means that Liberto paid less cash during the period than the debts that were incurred. Postponing liability payments is a common method for saving cash and keeping the reported balance high. The $9,000 should be added. Add $9,000 .

Salary payable decreased by $5,000 . Liability balances fall when additional payments are made. Those cash transactions are reflected in applying the indirect method by a $5,000 subtraction. Subtract $5,000 .

Therefore, if Liberto Company uses the indirect method to report its cash flows from operating activities, the information will take the following form.

Figure 17.8 Liberto Company Statement of Cash Flows for Year One, Operating Activities Reported by Indirect Method

As with the direct method, the final total is a net cash inflow of $133,000. In both cases, the starting spot was net income (either as a single number or the income statement as a whole). Then, any noncash items were removed as well as nonoperating gains and losses. Finally, the changes in the connector accounts that bridge the time period between U.S. GAAP recognition and the cash exchange are determined and included so that only cash from operating activities remains. The actual cash increase or decrease is not affected by the presentation of this information.

In reporting operating activity cash flows by means of the indirect method, the following pattern exists.

- A change in a connector account that is an asset is reflected on the statement in the opposite fashion. As shown above, increases in both accounts receivable and prepaid rent are subtracted; a decrease in inventory is added.

- A change in a connector account that is a liability is included on the statement as an identical change. An increase in accounts payable is added whereas a decrease in salary payable is subtracted.

A quick visual comparison of the direct method and the indirect method can make the two appear almost completely unrelated. However, when analyzed, the same steps are incorporated in each. They both begin with the income for the period. Noncash items and nonoperating gains and losses are removed. Changes in the connector accounts for the period are factored in so that only the cash from operations remains.

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2092976.html

Link to multiple-choice question for practice purposes: http://www.quia.com/quiz/2092977.html

Question: When reporting cash flows from operating activities for the year ended December 31, 2008, EMC Corporation listed an inflow of over $240 million labeled as “dividends and interest received” as well as an outflow of nearly $74 million shown as “interest paid. ”

Unless a company is a bank or financing institution, dividend and interest revenues do not appear to relate to its central operating function. For most businesses, these inflows are fundamentally different from the normal sale of goods and services. Monetary amounts collected as dividends and interest resemble investing activity cash inflows because they are usually generated from noncurrent assets. Similarly, interest expense is an expenditure normally associated with noncurrent liabilities rather than resulting from daily operations. It could be argued that it is a financing activity cash outflow .

Why is the cash collected as dividends and interest and the cash paid as interest reported within operating activities on a statement of cash flows rather than investing activities and financing activities?

Answer: Authoritative pronouncements that create U.S. GAAP are the subject of years of intense study, discussion, and debate. In this process, controversies often arise. When FASB Statement 95, Statement of Cash Flows , was issued in 1987, three of the seven board members voted against its passage. Their opposition, at least in part, came from the handling of interest and dividends. On page ten of that standard, they argue “that interest and dividends received are returns on investments in debt and equity securities that should be classified as cash inflows from investing activities. They believe that interest paid is a cost of obtaining financial resources that should be classified as a cash outflow for financing activities.”

The other board members were not convinced. Thus, inclusion of dividends collected, interest collected, and interest paid within an entity’s operating activities became a part of U.S. GAAP. Such disagreements arise frequently in the creation of official accounting rules.

The majority of the board apparently felt that—because these transactions occur on a regular ongoing basis—a better portrait of the organization’s cash flows is provided by including them within operating activities. At every juncture of financial accounting, multiple possibilities for reporting exist. Rarely is complete consensus ever achieved as to the most appropriate method of presenting financial information.

Talking with an Independent Auditor about International Financial Reporting Standards (Continued)

Following is the conclusion of our interview with Robert A. Vallejo, partner with the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Question : Any company that follows U.S. GAAP and issues an income statement must also present a statement of cash flows. Cash flows are classified as resulting from operating activities, investing activities, or financing activities. Are IFRS rules the same for the statement of cash flows as those found in U.S. GAAP?

Rob Vallejo : Differences do exist between the two frameworks for the presentation of the statement of cash flows, but they are relatively minor. Probably the most obvious issue involves the reporting of interest and dividends that are received and paid. Under IFRS, interest and dividend collections may be classified as either operating or investing cash flows whereas, in U.S. GAAP, they are both required to be shown within operating activities. A similar difference exists for interest and dividends payments. These cash outflows can be classified as either operating or financing activities according to IFRS. For U.S. GAAP, interest payments are viewed as operating activities whereas dividend payments are considered financing activities. As is common in much of IFRS, more flexibility is available.

Key Takeaway

Most reporting entities use the indirect method to report cash flows from operating activities. This presentation begins with net income and then eliminates any noncash items (such as depreciation expense) as well as nonoperating gains and losses. Their impact on net income is reversed to create this removal. The changes in balance sheet connector accounts for the year (such as accounts receivables, inventory, accounts payable, and salary payable) must also be taken into consideration in converting from accrual accounting to cash. An analysis is made of the effect on both cash and net income in order to make the proper adjustments. Cash transactions that result from interest revenue, dividend revenue, and interest expense are all left within operating activities because they happen regularly. However, some argue that interest and dividend collections are really derived from investing activities and interest payments relate to financing activities.

Financial Accounting Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Learning Accounting

Indirect method cash flow from operations: concepts.

Teaching (and learning) accounting involves starting with simple transactions and gradually layering in complexity. The idea is to use simple transactions to:

- Introduce basic concepts, such as assets, liabilities and net income;

- Build a set of tools, such as debit/credit, closing and balancing practices, that are used in addressing more complicated situations; and,

- Alert the student to the restrictions of the tools, e.g. balance sheets must balance so equity is really determined by our valuations of assets and liabilities. I.e., equity is not an independently defined concept.

- Acquaint the student with the level of care required for good quantitative analysis.

Getting this job done is challenging enough, but even more so when we recognize that our trip through simple items should not invite students to make errors in thinking that will inhibit their ability to address the more complex problems they will encounter later. Almost anyone with experience teaching the indirect method for cash flow from operations has encountered this problem: many (most? almost all?) students believe at some point that the amounts relating to the changes in balance sheet accounts are simply the ending balances minus the beginning balances for all the working capital accounts.

After decades of teaching the indirect method to undergraduate, graduate, MBA, law and executive students, we have found a way to teach it that lets the student build up their knowledge in a systematic way without misleading them. Our methods rely on students being introduced to the basics of the balance sheet, the income statement, journal entries, ledgers (T-accounts), adjusting and closing entries. The primary tool we use is the cash flow worksheet.

Accrual accounting v cash flows – Total Toy

After introducing the income statement and balance sheet, we go through a simple example designed to illustrate the relationship between net income and cash flow from operations. The trick to this is to include just enough complexity to make things interesting. If students have had an introductory economics class, the example can be used to emphasize the usefulness of accrual accounting. If they have also had an introductory course in finance, the example can be used to introduce valuation of businesses using discounted cash flow techniques. And if you want to push really far, you can use it to address the relationship between the economists’ approach (value) and the finance approach (cash flows). So let’s get going.

Consider the operations of a hypothetical company – Total Toy. Total Toy is a retailer that can sell a total of 14,400 dolls for $30 each. [1] It buys dolls from its supplier for $24 each. [2] It is a magical enterprise that can do this without paying any landlords or workers – Cost of Goods Sold is the only expense.

Consider how this “value generating engine” would be portrayed in an economics class, where the focus would be on whether Total Toy creates value, and if so, how it can maximize the value created. The basic idea would be to define revenue and cost as functions of “volume” and see whether profits are positive for any volume and at what volume they are maximized.

Executing this strategy is extremely simple for Total Toy. Total revenues would be equal to $30 times the number of dolls sold. Total costs would be $24 times the number of dolls sold. Here’s a picture:

It is worth going into great detail about the construction of this graph. The idea of the graph is to depict the value-generating possibilities of Total Toy. (An immediate issue is the length of the time period over which these value-generating activities are taking place. More on this later.)

The y-axis is labeled $, but what exactly is meant? Economists would want the y-axis to reflect the dollar amount of the value produced. Whether this value is manifested in cash, or the right to collect cash (i.e., receivables), is of no concern.

The x-axis is labeled # of dolls. What exactly do we mean by this? In the case of Total Toy, there are three possibilities: the number of dolls purchased, the number sold or the number held in inventory. Of these three possibilities, the number of dolls sold is the most directly related to the process of value creation. Once we designate a time period, we choose the point along the x-axis corresponding to the number of dolls sold that period. We then look vertically up from there to the total revenue function, which gives us the value received by Total Toy for the number of dolls sold that period. In accounting language, we have just applied the process of revenue recognition .

Continuing to use accounting terminology, to complete the assessment of profit, we now need to match expenses to the revenue recognized. In terms of the graph, proper matching consists of choosing the point on the x-axis corresponding to the number of dolls sold, looking vertically up to the total cost function and then reading the costs off the y-axis.

The final step is to calculate the dollar amount of the net value generated. In the figure below, $ Profit is the dollar value of the net value created in the period and is the difference between the dollar amount of revenue recognized and the dollar value of costs matched against that revenue.

These figures provide a compelling picture of Total Toy’s opportunities to generate value in a period. Note that there is an implicit distinction between Total Toy and other entities in the society. Sales must be to entities other than Total Toy (i.e., a customer ), and the revenue recognized by a sale is the dollar amount agreed to by both Total Toy and each of its customers. Similarly, expenses match against these revenues are linked to the dollar value of transactions in which Total Toy was the customer and other entities were suppliers . Therefore, these figures provide a model of the interactions of Total Toy with two other sets of actors: customers and suppliers. Like any model, a great many details are suppressed. In particular, the mechanics of the transactions between Total Toy, its customers and its suppliers are left out. We will fill in some of these details later, but first, it is worth considering one more “big” question.

Value of Total Toy

Now let’s think about the value of the enterprise, Total Toy. The value of Total Toy is a rather abstract thing. It is the value of the opportunity to generate value by operating Total Toy over time. To assess that, we turn to the techniques of modern finance.

The first thing we should notice when we find the relevant chapters in our finance test is that the value of Total Toy is viewed as being determined by the properties of the stream of cash flows it generates for its owners. Three properties of this cash flow stream are important: their amounts , their timing , and their riskiness . For our current purposes, we can suppress issues of risk and focus on amounts and timing. In particular, let’s adopt the straightforward view that the value of Total Toy is the present value of the cash flows it could generate to its owners.

It is important to observe that the figures presented so far do not directly address Total Toy’s cash flows. They address value flows. To get at cash flows, we must fill in some details as to how Total Toy operates; i.e., how more precisely Total Toy’s value generation opportunities are exploited. A natural place to start is to flesh out the transactions between Total Toy, its customers and its suppliers.

Operating Total Toy – Transactions’ Details

To keep things as simple as possible, suppose operating Total Toy consists of a few simple steps. First, dolls are purchased from a supplier. This is a cash purchase, as the supplier never lets its customers buy on account.

Second, dolls are placed in Total Toy’s inventory, where they sit for one month before being sold. All sales to customers are on account, with payment received in cash one month after the sale.

Third, cash is collected from customers one month after their purchase.

Operating Total Toy – Retail Doll Market

Demand for Total Toy’s dolls lasts for one year and will evolve over three phases: growth, steady state, and decline. In the growth phase, demand starts at 0 and grows by 600 dolls per month until it reaches 1,800, where it remains for 6 months. This period of constant demand is the steady state. After 6 months of this steady state, demand declines by 600 per month until it reaches 0.

Operating Total Toy – Wholesale Market

Of course, Total Toy must acquire the dolls it sells to customers and must hold them in inventory for one month. There is no advantage to stocking excess inventory, therefore Total Toy’s purchases from its supplier would be:

Operating Total Toy – Results of its entire existence

Over its life, Total Toy will sell 14,400 dolls. That will generate revenues of $432,000 and involve costs of $345,600. So the total profit generated will be $86,400. In terms of our picture:

In this picture, a period is defined as one year, and that suppresses an important fact if you actually want to run Total Toy – the dynamics of its cash flows.

Operating Total Toy – Cash Flows

We need to delve further into how the sales and purchases transaction work if we are to understand how cash flows in and out of Total Toy, and here is where things get interesting. The supplier demands cash immediately for any dolls purchased. The customers, however, only buy on account. Further, customers pay their bills one month after they buy the dolls. The following table gives Total Toy’s cash receipts and disbursements for each month of its life:

Even a quick glance at this table is revealing. In January, Total Toy must lay out $14,400 in cash, but receives nothing. It’s worse in February: $28,800 out and nothing in. March is a little better: $43,200 out and $18,000 in, and April is better still: $43,200 out and $36,000 in. Finally, in May the cash inflow exceeds the outflow: $43,200 out, and $54,000 in. In all the remaining months, cash collected exceeds cash spent.

So just looking at the cash flow figures, it is clear that, to actually run Total Toy, someone must provide some cash up front to get the business going until it reaches a stage where it can generate enough cash to cover the amount it has to spend. In the long run, Total Toy’s operations will generate $86,400 more in cash than consumes, but this analysis only holds in the long run. The problem is what you need to do in the short run in order to get there. This is where a bit of business planning is required.

Let’s start by seeing how big a cash deficit would be generated if we had no financing up front. Here’s the table:

Inspecting the column “Total Cash at Month End,” we see that the cash deficit hits its worst level in April, when Total Toy’ cumulative deficit hits $75,600.

Financing Total Toy

Just as Total Toy requires customers to buy its dolls and suppliers to provide them, to actually operate the company it needs to find a supplier of cash. When we think about customers, we think about the retail market. When we think about suppliers, we think about the wholesale market. Now we need to think about a financial market where there are suppliers of cash. And just like we had to get specific about how transactions with suppliers and customers work, we now need to get specific about how transactions with cash providers work.

For simplicity, we suppose that all cash must be raised at the beginning of January, and all distributions of cash will be occur at the end of December. Because Total Toy is a profitable company over its life, there will be $86,400 more cash at the end of December than is raised from financiers. That’s good because financiers that provide cash will want a return on their investment. As long as the total return required does not exceed $86,400, financing Total Toy is at least feasible.

Roughly speaking, we think about providers of cash as being one of two types: creditors and equity holders . Creditors provide cash up front in exchange for the right to receive specified payments of cash later. Equity holders provide cash up front in exchange for a share of the cash ultimately distributed.

Suppose the person that identifies the opportunity presented by Total Toy has the means and willingness to provide cash out of his own pocket. There is a bit of subtlety here – we have been thinking about Total Toy as an entity in and of itself. That is, we distinguish Total Toy from its owners, just as we do from its customers and suppliers. At any rate, suppose the owner puts $90,000 of his own cash into the business, Total Toy. Just like its customers and suppliers, Total Toy’s owner will expect some benefit from supplying Total Toy with this $90,000. The customer benefits through the enjoyment of the doll. The supplier benefits through the profits made by selling to Total Toy. What benefit would the owner require?

There are many joys and challenges of owning a business, but the financial return is often the primary benefit of ownership. We will focus, therefore, on the fact that the owner will be able to take $86,400 more out of Total Toy than the $90,000 he put into it. Here’s a table of the relevant numbers:

Before we leave the economics, let’s think about the owner’s return for his investment in Total Toy. An investment of $90,000 at the beginning of January gets the owner $176,400 at the end of December. The owner’s rate of return is:

(1+r)*$90,000 = $176,400 → r = 96%.

As long as the owner’s other investment opportunities would return less than 96% on a $90,000 investment, he will find investing this amount in Total Toy is an attractive opportunity.

Financial Statements

Having presented all the details of Total Toy’s one year life, we now show three sets of monthly financial statements: balance sheets, income statements and statements of cash flows.

The balance sheets are:

The income statements are:

We should think a little before we do a cash flow statement. We want that statement to reveal more than the change in cash because anyone can get that by subtracting the beginning cash balance from the ending cash balance. We want the cash flow statement to reveal something about the flow of cash, but what? Let’s begin to address that question by comparing the cash flows to the other flow we have, net income. Here’s the table:

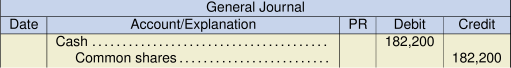

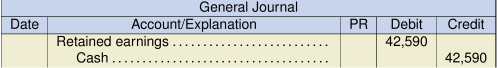

This comparison between net income and cash flows is not very revealing, in part because there are two cash transactions that are not related to the operating of Total Toy. That is, value creation, as reflected by net income, inherently involves using resources to create value, not merely acquiring or disposing of resources. Two of Total Toy’s transactions – the exchange of its equity for $90,000 at the beginning of January and the exchange of $176,400 to buy back its equity at the end of December – do no involving using Total Toy’s value-creation engine to create value. They are part of what is required for Total Toy to access its value-creation opportunity, but they are not directly involved in using that opportunity. Therefore, we think about the initial contribution of $90,000 and the dissolution payment of $176,400 as financing transactions , not operating transactions . The following table breaks up Total Toy’s cash flows into Operating and Financing pieces:

We could add more detail to the calculation of Operating Cash Flows:

This form of the statement of Operating Cash Flows just reproduces our analysis of Total Toy’s cash requirements in Table 3. It is intuitive, but it is also a “stand alone” type of presentation. That is, it tells us about cash flows, but not in a way that is woven in with the other financial statements. Can we do better?

A place to start is to compare operating cash flows to net income. Here is the table:

This is an interesting exercise, particularly when we recall that the net income numbers tell us about value flows and the cash flow numbers, obviously, tell us about cash flows. [3] For Total Toy, the flow of value is much smoother than the flow of cash. Value flows in a month relate simply to the sales in that month. Cash receipts and disbursements are related to value flows over the life of Total Toy, but are not so intuitive on a month-by-month basis. Cash disbursements to suppliers have to cover inventory purchases for next month’s sales. Cash collections are for last month’s sales. In a sense, there are timing mismatches in cash receipts and disbursements, at least from the standpoint of value-creation activities.

Further, we could go into some detail about these timing mismatches; i.e., about why there is a difference between cash flows and net income. One place those are reflected is in the balance sheet. For example, when Total Toy spends $14,400 for dolls from its supplier in January, it is purchasing an asset that will be useful in next month’s operations. This asset, Inventory , is reflected on Total Toy’s balance sheet as of the end of January. Similarly, when Total Toy sells 600 dolls in February, the right to collect $18,000 in cash in March is listed as an asset, Accounts Receivable , on Total Toy’s balance sheet at the end of February.

Revenues v. Receipts

Look at the following table showing the difference between cash receipts and revenues:

Over the course of Total Toy’s life, cash collected from customers is equal to revenue. But what about in February? Revenue of $18,000 was recognized, but no cash was collected. This generated Accounts Receivable of $18,000. Total Toy starts February with $0 in Accounts Receivable, and ends it with $18,000 because revenue recognized exceeds cash collected from customers. Now look at March. Total Toy does collect some cash in March: $18,000. But it recognizes $36,000 in revenue. Again, revenue recognized exceeds cash collected from customers by $18,000. Total Toy starts March with $18,000 in receivables and adds $36,000 though new sales, an increase of $36,000 - $18,000 = $18,000. So Accounts Receivable will increase by $18,000. The difference between cash collected from customers and revenue recognized is reflected in an increase in Accounts Receivable when revenues exceed collections. We will not take the space to present the details, but it is worth going through this table month by month. You will see that as collections catch up to sales, the balance in Accounts Receivable remains steady. As collections outpace sales, the balance in Accounts Receivables falls. Stating these in the different direction, the balance of Accounts Receivable grows with revenues exceed collections, remains constant when revenues equal collections, and decreases when revenues are less than collections. This is reflected in the following table:

Notice that, because we are dealing with revenues, an increase in Accounts Receivable means that less cash was collected than revenues recognized. [4]

Expenses v Disbursements

Now let’s do the same exercise with cash disbursements. Here is the table:

In January, cash paid to suppliers is $14,400, while cost of goods sold is $0. If Total Toy spent cash to purchase dolls but still has those dolls on hand at the end of the month, the asset account, Inventory, will reflect this. Inventory is $0 at the beginning of January, and increases to $14,400 by the end of January. Why? Total Toy bought $14,400 more dolls than it used in the value-creation process. [5] In the long run, the total value of dolls sold equals the total value of dolls purchased, but that does not necessarily occur month-to-month. In the growth phase, Total Toy buys more dolls than it sells, and inventory grows. In steady state, it will buy and sell the same number of dolls and inventory remains constant until the decline is anticipated. In decline, the number of dolls sold exceeds the number of dolls purchased, and inventory decreases. In a perfectly managed decline, the last doll sold will be the last doll remaining in inventory and, as it was at the start of Total Toy, inventory will be $0. Here’s the table:

Notice that, because we are dealing with expenses, an increase in Inventory means that more cash was spent than cost of goods sold recognized.

Putting It All Together

Only two steps are required to operate Total Toy: buying dolls and selling dolls. Therefore, if we put the revenue/receipts and expense/disbursements stories together, we should have an explanation of the difference between net income and operating cash flows. The following table verifies this intuition:

Even though Total Toy is a very simple example, we see from the table that keeping signs straight is not easy. The trouble is that we have both inflows and outflows of cash and revenues (increases) and expenses (decreases), so there are a lot of cases. In this simple case we can reason our way through, but we will want a tool to make our work easier in more complicated cases. Think about the month of January. Cash disbursements exceed cost of goods sold, so we should subtract the increase in inventory. Now think about December. Cash receipts exceed revenues recognized, so we should subtract the decrease in inventory.

Those familiar with cash flow statements will recognize that we have just presented cash flow from operations using the indirect method . The indirect method starts with net income and shows the steps required to get to cash flow from operations. Some things to note:

- When Total Toy is in the midst of steady state, there is nothing to explain because cash flow from operations and net income are equal. All the action takes place when Total Toy is either growing or declining (or transitioning between one of those phases and steady state).

- The indirect method of stating cash flows from operations relies on the links between the asset accounts, Accounts Receivable and Inventory, and the income statement accounts, Sales and Cost of Goods Sold, respectively. In general, liability accounts will also be involved. For example, if the supplier is willing to extend credit on Total Toy’s doll purchases, the liability account, Accounts Payable – Inventory, would be tied to Cost of Goods Sold. The indirect method would then involve tracking changes in Accounts Payable related to doll purchases.

- The growth, steady state, and decline phases of Total Toy are hypothetical ideals. Any business that survives for very long likely went through a growth phase fairly early in its life, but real organizations may go through various phases several times.

- The information in these cash flow from operations calculations is completely redundant given the income statement and balance sheets. That is, while intuitively appealing, anyone with access to the income statements and balance sheets could reproduce the information in the indirect method cash flow from operations statements.

- Given the simple transactions in which Total Toy engaged, the links between the balance sheet accounts and the income statement are particularly simple. In fact, they are deceptively simple. For example, the only reason Accounts Receivable changed over a period is that Sales were not equal Cash Collected from Customers over that period. This is not true for almost every company in almost every period. It is true that the difference between Sales and Cash Collected from Customers is one reason Accounts Receivable can change, but it is not the only reason. There are usually other transactions that affect Accounts Receivable that must be sorted out before we can find the part of the change in Accounts Receivable reflects the difference between Sales and Cash Collected with Customers.

Adding an Investment Decision

After the initial financing, Total Toy has only operating activities. For completeness, we now add an investing decision. This will have two effects: there is an additional cash outflow and the net income calculations will include depreciation expense.

Suppose Total Toy has to purchase a display case for its dolls. The case costs $12,000 and must be purchased before business commences. At the end of 12 months, it will be hauled away for free by a scrap dealer. Everything else proceeds as before.

Table 17 updates the cash flows given in Table 9 by adding an Investing Cash Flow column.

The income statement now includes depreciation expense, as shown in Table 18.

Here is the comparison of Net Income and Cash Flow from Operations:

[1] In terms of a traditional demand curve, our assumptions are pretty extreme. In any period, 0 dolls are demanded at any price over $30. Further, cutting the price to, say, $29, is assumed to result in no additional demand.

[2] The implicit assumptions about the supply curve are also extreme. At any price below $24, zero dolls will be supplied, and any number of dolls will be supplied at $24.

[3] As we have discussed, cash flows are connected to value when we consider the value of the enterprise, Total Toy.

[4] More generally, we will have to work with revenues and expenses and related asset and liability account increases and decreases. Keeping track of signs gets tricky. (For a striking example of the mistakes this can lead to in practice, see Antle and Garstka, Financial Accounting: Questions, Exercises, Problems and Cases, Masters Edition (2 nd Edition: 2004) Case 16-5 on page 402. That is one important function of the worksheet we introduce later.

[5] Total Toy uses dolls in the value-creation process by selling them.

The IFRS Foundation is a not-for-profit, public interest organisation established to develop high-quality, understandable, enforceable and globally accepted accounting and sustainability disclosure standards.

Our Standards are developed by our two standard-setting boards, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB).

About the IFRS Foundation

Ifrs foundation governance, stay updated.

IFRS Accounting Standards are developed by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). The IASB is an independent standard-setting body within the IFRS Foundation.

IFRS Accounting Standards are, in effect, a global accounting language—companies in more than 140 jurisdictions are required to use them when reporting on their financial health. The IASB is supported by technical staff and a range of advisory bodies.

IFRS Accounting

Standards and frameworks, using the standards, project work, products and services.

IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards are developed by the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). The ISSB is an independent standard-setting body within the IFRS Foundation.

IFRS Sustainability Standards are developed to enhance investor-company dialogue so that investors receive decision-useful, globally comparable sustainability-related disclosures that meet their information needs. The ISSB is supported by technical staff and a range of advisory bodies.

IFRS Sustainability

Education, membership and licensing.

IAS 7 Statement of Cash Flows

You need to Sign in to use this feature

IAS 7 prescribes how to present information in a statement of cash flows about how an entity’s cash and cash equivalents changed during the period. Cash comprises cash on hand and demand deposits. Cash equivalents are short-term, highly liquid investments that are readily convertible to known amounts of cash and that are subject to an insignificant risk of changes in value.

The statement classifies cash flows during a period into cash flows from operating, investing and financing activities:

- the direct method, whereby major classes of gross cash receipts and gross cash payments are disclosed; or

- the indirect method, whereby profit or loss is adjusted for the effects of transactions of a non-cash nature, any deferrals or accruals of past or future operating cash receipts or payments and items of income or expense associated with investing or financing cash flows.

- investing activities are the acquisition and disposal of long-term assets and other investments not included in cash equivalents. The aggregate cash flows arising from obtaining and losing control of subsidiaries or other businesses are presented as investing activities.

- financing activities are activities that result in changes in the size and composition of the contributed equity and borrowings of the entity.

Standard history

In April 2001 the International Accounting Standards Board (Board) adopted IAS 7 Cash Flow Statements , which had originally been issued by the International Accounting Standards Committee in December 1992. IAS 7 Cash Flow Statements replaced IAS 7 Statement of Changes in Financial Position (issued in October 1977).

As a result of the changes in terminology used throughout the IFRS Standards arising from requirements in IAS 1 Presentation of Financial Statements (issued in 2007), the title of IAS 7 was changed to Statement of Cash Flows .

In January 2016 IAS 7 was amended by Disclosure Initiative (Amendments to IAS 7). These amendments require entities to provide disclosures about changes in liabilities arising from financing activities.

In May 2023 the Board issued Supplier Finance Arrangements (Amendments to IAS 7 and IFRS 7) to require an entity to provide additional disclosures about its supplier finance arrangements.

Other Standards have made minor consequential amendments to IAS 7. They include IFRS 10 Consolidated Financial Statements (issued May 2011), IFRS 11 Joint Arrangements (issued May 2011), Investment Entities (Amendments to IFRS 10, IFRS 12 and IAS 27) (issued October 2012), IFRS 16 Leases (issued January 2016) and IFRS 17 Insurance Contracts (issued May 2017).

Related active projects

Annual Improvements to IFRS Accounting Standards—Cost Method (Amendments to IAS 7)

Related completed projects

Classification of short-term loans and credit facilities (IAS 7)

Demand Deposits with Restrictions on Use arising from a Contract with a Third Party (IAS 7)

Disclosure Initiative (Amendments to IAS 7)

Disclosure Initiative—Principles of Disclosure

Disclosure of Changes in Liabilities Arising from Financing Activities (IAS 7 Statement of Cash Flows)

IFRS Accounting Taxonomy Update—Amendments to IAS 12, IAS 21, IAS 7 and IFRS 7

Joint Financial Statement Presentation (Replacement of IAS 1)

Supplier Finance Arrangements

Supply Chain Financing Arrangements—Reverse Factoring

Video: IASB Member Ann Tarca explains proposed changes to IFRS Accounting Taxonomy 2023

Related IFRS Standards

Related ifric interpretations, unconsolidated amendments, implementation support, your privacy.

IFRS Foundation cookies

We use cookies on ifrs.org to ensure the best user experience possible. For example, cookies allow us to manage registrations, meaning you can watch meetings and submit comment letters. Cookies that tell us how often certain content is accessed help us create better, more informative content for users.

We do not use cookies for advertising, and do not pass any individual data to third parties.

Some cookies are essential to the functioning of the site. Other cookies are optional. If you accept all cookies now you can always revisit your choice on our privacy policy page.

Cookie preferences

Essential cookies, always active.

Essential cookies are required for the website to function, and therefore cannot be switched off. They include managing registrations.

Analytics cookies

We use analytics cookies to generate aggregated information about the usage of our website. This helps guide our content strategy to provide better, more informative content for our users. It also helps us ensure that the website is functioning correctly and that it is available as widely as possible. None of this information can be tracked to individual users.

Preference cookies

Preference cookies allow us to offer additional functionality to improve the user experience on the site. Examples include choosing to stay logged in for longer than one session, or following specific content.

Share this page

16.3 Prepare the Statement of Cash Flows Using the Indirect Method

The statement of cash flows is prepared by following these steps:

Step 1: Determine Net Cash Flows from Operating Activities

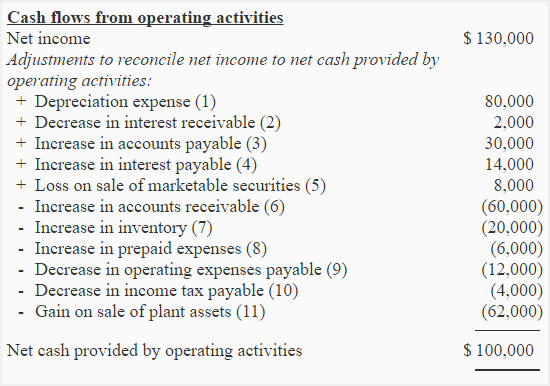

Using the indirect method , operating net cash flow is calculated as follows:

- Begin with net income from the income statement.

- Add back noncash expenses, such as depreciation, amortization, and depletion.

- Remove the effect of gains and/or losses from disposal of long-term assets, as cash from the disposal of long-term assets is shown under investing cash flows.

- Adjust for changes in current assets and liabilities to remove accruals from operating activities.

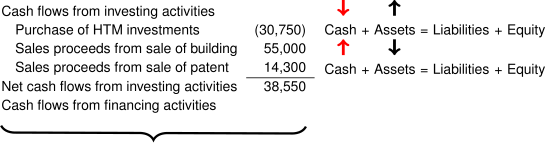

Step 2: Determine Net Cash Flows from Investing Activities

Investing net cash flow includes cash received and cash paid relating to long-term assets.

Step 3: Present Net Cash Flows from Financing Activities

Financing net cash flow includes cash received and cash paid relating to long-term liabilities and equity.

Step 4: Reconcile Total Net Cash Flows to Change in Cash Balance during the Period

To reconcile beginning and ending cash balances:

- The net cash flows from the first three steps are combined to be total net cash flow.

- The beginning cash balance is presented from the prior year balance sheet.

- Total net cash flow added to the beginning cash balance equals the ending cash balance.

Step 5: Present Noncash Investing and Financing Transactions

Transactions that do not affect cash but do affect long-term assets, long-term debt, and/or equity are disclosed, either as a notation at the bottom of the statement of cash flow, or in the notes to the financial statements.

The remainder of this section demonstrates preparation of the statement of cash flows of the company whose financial statements are shown in Figure 16.2 , Figure 16.3 , and Figure 16.4 .

Additional Information:

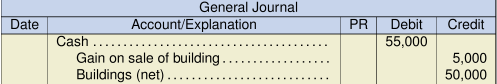

- Propensity Company sold land with an original cost of $10,000, for $14,800 cash.

- A new parcel of land was purchased for $20,000, in exchange for a note payable.

- Plant assets were purchased for $50,000 cash.

- Propensity declared and paid a $440 cash dividend to shareholders.

- Propensity issued common stock in exchange for $45,000 cash.

- Propensity issued $20,000 in common stock to employees as a bonus.

Prepare the Operating Activities Section of the Statement of Cash Flows Using the Indirect Method

In the following sections, specific entries are explained to demonstrate the items that support the preparation of the operating activities section of the Statement of Cash Flows (Indirect Method) for the Propensity Company example financial statements.

- Reverse the effect of gains and/or losses from investing activities.

- Adjust for changes in current assets and liabilities, to reflect how those changes impact cash in a way that is different than is reported in net income.0

Start with Net Income

The operating activities cash flow is based on the company’s net income, with adjustments for items that affect cash differently than they affect net income. The net income on the Propensity Company income statement for December 31, 2018, is $4,340. On Propensity’s statement of cash flows, this amount is shown in the Cash Flows from Operating Activities section as Net Income.

Add Back Noncash Expenses

Net income includes deductions for noncash expenses. To reconcile net income to cash flow from operating activities, these noncash items must be added back, because no cash was expended relating to that expense. The sole noncash expense on Propensity Company’s income statement, which must be added back , is the depreciation expense of $14,400. On Propensity’s statement of cash flows, this amount is shown in the Cash Flows from Operating Activities section as an adjustment to reconcile net income to net cash flow from operating activities.

Reverse the Effect of Gains and/or Losses

Gains and/or losses on the disposal of long-term assets are included in the calculation of net income, but cash obtained from disposing of long-term assets is a cash flow from an investing activity. Because the disposition gain or loss is not related to normal operations, the adjustment needed to arrive at cash flow from operating activities is a reversal of any gains or losses that are included in the net income total. A gain is subtracted from net income and a loss is added to net income to reconcile to cash from operating activities. Propensity’s income statement for the year 2018 includes a gain on sale of land, in the amount of $4,800, so a reversal is accomplished by subtracting the gain from net income. On Propensity’s statement of cash flows, this amount is shown in the Cash Flows from Operating Activities section as Gain on Sale of Plant Assets.

Adjust for Changes in Current Assets and Liabilities

Because the Balance Sheet and Income Statement reflect the accrual basis of accounting, whereas the statement of cash flows considers the incoming and outgoing cash transactions, there are continual differences between (1) cash collected and paid and (2) reported revenue and expense on these statements. Changes in the various current assets and liabilities can be determined from analysis of the company’s comparative balance sheet, which lists the current period and previous period balances for all assets and liabilities. The following four possibilities offer explanations of the type of difference that might arise, and demonstrate examples from Propensity Company’s statement of cash flows, which represent typical differences that arise relating to these current assets and liabilities.

Increase in Noncash Current Assets

Increases in current assets indicate a decrease in cash, because either (1) cash was paid to generate another current asset, such as inventory, or (2) revenue was accrued, but not yet collected, such as accounts receivable. In the first scenario, the use of cash to increase the current assets is not reflected in the net income reported on the income statement. In the second scenario, revenue is included in the net income on the income statement, but the cash has not been received by the end of the period. In both cases, current assets increased and net income was reported on the income statement greater than the actual net cash impact from the related operating activities. To reconcile net income to cash flow from operating activities, subtract increases in current assets.

Propensity Company had two instances of increases in current assets. One was an increase of $700 in prepaid insurance, and the other was an increase of $2,500 in inventory. In both cases, the increases can be explained as additional cash that was spent, but which was not reflected in the expenses reported on the income statement.

Decrease in Noncash Current Assets

Decreases in current assets indicate lower net income compared to cash flows from (1) prepaid assets and (2) accrued revenues. For decreases in prepaid assets, using up these assets shifts these costs that were recorded as assets over to current period expenses that then reduce net income for the period. Cash was paid to obtain the prepaid asset in a prior period. Thus, cash from operating activities must be increased to reflect the fact that these expenses reduced net income on the income statement, but cash was not paid this period. Secondarily, decreases in accrued revenue accounts indicates that cash was collected in the current period but was recorded as revenue on a previous period’s income statement. In both scenarios, the net income reported on the income statement was lower than the actual net cash effect of the transactions. To reconcile net income to cash flow from operating activities, add decreases in current assets.

Propensity Company had a decrease of $4,500 in accounts receivable during the period, which normally results only when customers pay the balance, they owe the company at a faster rate than they charge new account balances. Thus, the decrease in receivable identifies that more cash was collected than was reported as revenue on the income statement. Thus, an addback is necessary to calculate the cash flow from operating activities.

Current Operating Liability Increase

Increases in current liabilities indicate an increase in cash, since these liabilities generally represent (1) expenses that have been accrued, but not yet paid, or (2) deferred revenues that have been collected, but not yet recorded as revenue. In the case of accrued expenses, costs have been reported as expenses on the income statement, whereas the deferred revenues would arise when cash was collected in advance, but the revenue was not yet earned, so the payment would not be reflected on the income statement. In both cases, these increases in current liabilities signify cash collections that exceed net income from related activities. To reconcile net income to cash flow from operating activities, add increases in current liabilities.

Propensity Company had an increase in the current operating liability for salaries payable, in the amount of $400. The payable arises, or increases, when an expense is recorded but the balance due is not paid at that time. An increase in salaries payable therefore reflects the fact that salaries expenses on the income statement are greater than the cash outgo relating to that expense. This means that net cash flow from operating is greater than the reported net income, regarding this cost.

Current Operating Liability Decrease

Decreases in current liabilities indicate a decrease in cash relating to (1) accrued expenses, or (2) deferred revenues. In the first instance, cash would have been expended to accomplish a decrease in liabilities arising from accrued expenses, yet these cash payments would not be reflected in the net income on the income statement. In the second instance, a decrease in deferred revenue means that some revenue would have been reported on the income statement that was collected in a previous period. As a result, cash flows from operating activities must be decreased by any reduction in current liabilities, to account for (1) cash payments to creditors that are higher than the expense amounts on the income statement, or (2) amounts collected that are lower than the amounts reflected as income on the income statement. To reconcile net income to cash flow from operating activities, subtract decreases in current liabilities.

Propensity Company had a decrease of $1,800 in the current operating liability for accounts payable. The fact that the payable decreased indicates that Propensity paid enough payments during the period to keep up with new charges, and also to pay down on amounts payable from previous periods. Therefore, the company had to have paid more in cash payments than the amounts shown as expense on the Income Statements, which means net cash flow from operating activities is lower than the related net income.

Analysis of Change in Cash

Although the net income reported on the income statement is an important tool for evaluating the success of the company’s efforts for the current period and their viability for future periods, the practical effectiveness of management is not adequately revealed by the net income alone. The net cash flows from operating activities adds this essential facet of information to the analysis, by illuminating whether the company’s operating cash sources were adequate to cover their operating cash uses. When combined with the cash flows produced by investing and financing activities, the operating activity cash flow indicates the feasibility of continuance and advancement of company plans.

Determining Net Cash Flow from Operating Activities (Indirect Method)

Net cash flow from operating activities is the net income of the company, adjusted to reflect the cash impact of operating activities. Positive net cash flow generally indicates adequate cash flow margins exist to provide continuity or ensure survival of the company. The magnitude of the net cash flow, if large, suggests a comfortable cash flow cushion, while a smaller net cash flow would signify an uneasy comfort cash flow zone. When a company’s net cash flow from operations reflects a substantial negative value, this indicates that the company’s operations are not supporting themselves and could be a warning sign of possible impending doom for the company. Alternatively, a small negative cash flow from operating might serve as an early warning that allows management to make needed corrections, to ensure that cash sources are increased to amounts in excess of cash uses, for future periods.

For Propensity Company, beginning with net income of $4,340, and reflecting adjustments of $9,500, delivers a net cash flow from operating activities of $13,840.

Cash Flow from Operating Activities

Assume you own a specialty bakery that makes gourmet cupcakes. Excerpts from your company’s financial statements are shown.

How much cash flow from operating activities did your company generate?

Think It Through

Explaining changes in cash balance.

Assume that you are the chief financial officer of a company that provides accounting services to small businesses. You are called upon by the board of directors to explain why your cash balance did not increase much from the beginning of 2018 until the end of 2018, since the company produced a reasonably strong profit for the year, with a net income of $88,000. Further assume that there were no investing or financing transactions, and no depreciation expense for 2018. What is your response? Provide the calculations to back up your answer.

Prepare the Investing and Financing Activities Sections of the Statement of Cash Flows

Preparation of the investing and financing sections of the statement of cash flows is an identical process for both the direct and indirect methods, since only the technique used to arrive at net cash flow from operating activities is affected by the choice of the direct or indirect approach. The following sections discuss specifics regarding preparation of these two nonoperating sections, as well as notations about disclosure of long-term noncash investing and/or financing activities. Changes in the various long-term assets, long-term liabilities, and equity can be determined from analysis of the company’s comparative balance sheet, which lists the current period and previous period balances for all assets and liabilities.

Investing Activities

Cash flows from investing activities always relate to long-term asset transactions and may involve increases or decreases in cash relating to these transactions. The most common of these activities involve purchase or sale of property, plant, and equipment, but other activities, such as those involving investment assets and notes receivable, also represent cash flows from investing. Changes in long-term assets for the period can be identified in the Noncurrent Assets section of the company’s comparative balance sheet, combined with any related gain or loss that is included on the income statement.

In the Propensity Company example, the investing section included two transactions involving long-term assets, one of which increased cash, while the other one decreased cash, for a total net cash flow from investing of ($25,200). Analysis of Propensity Company’s comparative balance sheet revealed changes in land and plant assets. Further investigation identified that the change in long-term assets arose from three transactions:

- Investing activity: A tract of land that had an original cost of $10,000 was sold for $14,800.

- Investing activity: Plant assets were purchased, for $60,000 cash.

- Noncash investing and financing activity: A new parcel of land was acquired, in exchange for a $20,000 note payable.

Details relating to the treatment of each of these transactions are provided in the following sections.

Investing Activities Leading to an Increase in Cash

Increases in net cash flow from investing usually arise from the sale of long-term assets. The cash impact is the cash proceeds received from the transaction, which is not the same amount as the gain or loss that is reported on the income statement. Gain or loss is computed by subtracting the asset’s net book value from the cash proceeds. Net book value is the asset’s original cost, less any related accumulated depreciation. Propensity Company sold land, which was carried on the balance sheet at a net book value of $10,000, representing the original purchase price of the land, in exchange for a cash payment of $14,800. The data set explained these net book value and cash proceeds facts for Propensity Company. However, had these facts not been stipulated in the data set, the cash proceeds could have been determined by adding the reported $4,800 gain on the sale to the $10,000 net book value of the asset given up, to arrive at cash proceeds from the sale.

Investing Activities Leading to a Decrease in Cash

Decreases in net cash flow from investing normally occur when long-term assets are purchased using cash. For example, in the Propensity Company example, there was a decrease in cash for the period relating to a simple purchase of new plant assets, in the amount of $60,000.

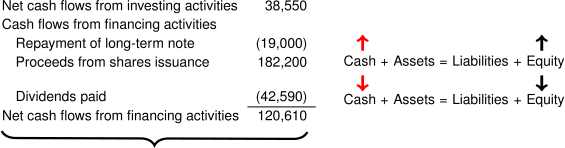

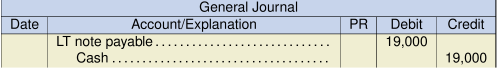

Financing Activities

Cash flows from financing activities always relate to either long-term debt or equity transactions and may involve increases or decreases in cash relating to these transactions. Stockholders’ equity transactions, like stock issuance, dividend payments, and treasury stock buybacks are very common financing activities. Debt transactions, such as issuance of bonds payable or notes payable, and the related principal payback of them, are also frequent financing events. Changes in long-term liabilities and equity for the period can be identified in the Noncurrent Liabilities section and the Stockholders’ Equity section of the company’s Comparative Balance Sheet, and in the retained earnings statement.

In the Propensity Company example, the financing section included three transactions. One long-term debt transaction decreased cash. Two transactions related to equity, one of which increased cash, while the other one decreased cash, for a total net cash flow from financing of $34,560. Analysis of Propensity Company’s Comparative Balance Sheet revealed changes in notes payable and common stock, while the retained earnings statement indicated that dividends were distributed to stockholders. Further investigation identified that the change in long-term liabilities and equity arose from three transactions:

- Financing activity: Borrowed an additional $10,000 on notes payable.

- Financing activity: New shares of common stock were issued, in the amount of $45,000. (Note the $20,000 in common stock issued for employee bonuses is not a cash flow transaction.)

- Financing activity: Dividends of $440 were paid to shareholders.

Specifics about each of these three transactions are provided in the following sections.

Financing Activities Leading to an Increase in Cash

Increases in net cash flow from financing usually arise when the company issues share of stock, bonds, or notes payable to raise capital for cash flow. Propensity Company had two examples of an increase in cash flows, one from the issuance of common stock, and one from increased borrowing through notes payable.

Financing Activities Leading to a Decrease in Cash

Decreases in net cash flow from financing normally occur when (1) long-term liabilities, such as notes payable or bonds payable are repaid, (2) when the company reacquires some of its own stock (treasury stock), or (3) when the company pays dividends to shareholders. In the case of Propensity Company, the decreases in cash resulted from notes payable principal repayments and cash dividend payments.

Noncash Investing and Financing Activities

Sometimes transactions can be very important to the company, yet not involve any initial change to cash. Disclosure of these noncash investing and financing transactions can be included in the notes to the financial statements, or as a notation at the bottom of the statement of cash flows, after the entire statement has been completed. These noncash activities usually involve one of the following scenarios:

- exchanges of long-term assets for long-term liabilities or equity, or

- exchanges of long-term liabilities for equity.

Propensity Company had a noncash investing and financing activity, involving the purchase of land (investing activity) in exchange for a $20,000 note payable (financing activity).

Summary of Investing and Financing Transactions on the Cash Flow Statement

Investing and financing transactions are critical activities of business, and they often represent significant amounts of company equity, either as sources or uses of cash. Common activities that must be reported as investing activities are purchases of land, equipment, stocks, and bonds, while financing activities normally relate to the company’s funding sources, namely, creditors and investors. These financing activities could include transactions such as borrowing or repaying notes payable, issuing or retiring bonds payable, or issuing stock or reacquiring treasury stock, to name a few instances.

Cash Flow from Investing Activities

Assume your specialty bakery makes gourmet cupcakes and has been operating out of rented facilities in the past. You owned a piece of land that you had planned to someday use to build a sales storefront. This year your company decided to sell the land and instead buy a building, resulting in the following transactions.

What are the cash flows from investing activities relating to these transactions?

Note: Interest earned on investments is an operating activity.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-financial-accounting/pages/1-why-it-matters

- Authors: Mitchell Franklin, Patty Graybeal, Dixon Cooper

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Accounting, Volume 1: Financial Accounting

- Publication date: Apr 11, 2019