The Power of Words

How to build verbal agility

Posted August 23, 2022 | Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Words are enormously powerful tools that most people don’t fully appreciate. Although people recognize the importance of communication skills, they don’t necessarily grasp how to become more effective communicators.

When people develop true mental agility in working with language, they gain a range of skills that make them more highly effective communicators. Attuned to the nuances of words, they become expert at working in teams because they can communicate clearly and translate the real meaning of what one person says to another person. They are able to separate their emotional reaction to a report or news article from their cognitive reaction and as a result can glean what’s really significant. They can “read” other people by the words they use and the way they use them.

Language is a neurocognitive tool by which we can:

· Transmit and exchange information

· Influence and control the behavior of others

· Establish and demonstrate social cohesion, and

· Imagine and create new ways of experiencing life.

To appreciate the power and majesty of words, we have to recognize that they mean more than their dictionary definitions. Words require context to make them meaningful. We understand them in relation to other words. A single word such as light can evoke different images and emotions at different times: The Charge of the Light Brigade , a light snack, the light at the end of the tunnel, lighthearted, lightweight, lightbulb, light of my life, and more.

We understand others best when we can identify the purpose that frames the words. For example, reports are intended to help people crystallize a problem. A good report contains information that is verifiable. A good report writer carefully avoids inferences, judgments, and inflammatory language that might bias the reader and affect the quality of the work.

On the other hand, preachers, parents, teachers, propagandists, politicians, and employers use directives to influence and control the future behavior of their listeners or readers. Directives promise rewards and/or consequences. Those that have the strongest impact engage people’s emotions through the dramatic application of tone, rhyme, rhythm, and repetition, devices through which the message is embedded in our memory .

Words are so much a part of our human experience that we need to disengage ourselves from them. We disengage by turning words into objects—by playing word games. People who play with words are more conscious of the subtleties and innuendos that conversations contain and are less likely to be swayed by emotional appeals or fall victim to their own prejudices.

Difficult crossword puzzles, such as the New York Times crossword puzzle, force solvers to pursue increasingly subtle clues as the week progresses and the puzzles get harder. Think about all those people you know who brag that they do the New York Times crossword puzzle in ink. Doing the puzzle in ink intimates that their verbal agility is such that they won’t make mistakes and need to erase answers in order to try again.

Wordle erupted in popularity in 2021, making players guess a five-letter word by staring with a random guess. As the player guesses letters correctly, they appear in yellow or green—yellow means it’s in the day’s word and green means that it’s in the day’s word and you’ve put it in the correct place. Players are limited to six guesses. Guessing the day’s word with no other context but your vocabulary and understanding of spelling conventions forces players to think about words differently.

Turning One Word into Another

It takes a long time to learn to read and even longer to learn to read well. Once that threshold has been crossed, we become efficient readers. We read automatically—traffic signs, cereal boxes, billboards, t-shirts. In fact, we can’t stop ourselves from reading when we see what looks like a word.

In the verbal puzzle below, you will need to bring out your Wordle skills to understand how one word can follow a pattern to turn into a series of different words. The word on the far left on the first line is SEED and the word on the far right is PICK . In the example, you can see how changing one letter each time can get you from SEED to PICK. But you need to take into account what that last word is so that you can make the appropriate guesses.

SEED SEEK PEEK PECK PICK

HANK ____ ____ ____ PORT

HARE ____ ____ ____ COOK

MAUL ____ ____ ____ WILD

ROOD ____ ____ ____ LICK

HELP ____ ____ ____ ROAM

TEST ____ ____ ____ PORE

DILL ____ ____ ____ BOOT

TUBA ____ ____ ____ DONE

DIVE ____ ____ ____ HART

DUNK ____ ____ ____ BEET

MUST ____ ____ ____ DOCK

LIFE ____ ____ ____ DEBT

HAIR ____ ____ ____ DEAN

DELL ____ ____ ____ VOTE

MITT ____ ____ ____ PACE

What makes the puzzle hard is that you have to switch between thinking abstractly and thinking concretely. The puzzle would be easy if all you had to do was randomly replace letters. By having to come up with a legitimate word each time, as in Wordle , you have to think through the words you know. Puzzles like this one help breed verbal agility.

HANK HARK PARK PART PORT

HARE CARE CORE CORK COOK

MAUL MALL WALL WILL WILD

ROOD ROOK ROCK LOCK LICK

HELP HEAP REAP REAM ROAM

TEST PEST POST PORT PORE

DILL DOLL BOLL BOLT BOOT

TUBA TUBE TUNE TONE DONE

DIVE HIVE HAVE HATE HART

DUNK BUNK BUNT BENT BEET

MUST DUST DUSK DUCK DOCK

LIFE LIFT LEFT DEFT DEBT

HAIR HEIR HEAR DEAR DEAN

DELL DOLL DOLE DOTE VOTE

MITT MITE MICE MACE PACE

Donalee Markus, Ph.D., specializes in the clinical application of neuroscience to rehabilitate concussion, stroke, and traumatic brain injury, enhance academic performance, and maintain memory skills.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

The Irrefutable Power Of Words

You’ve experienced the power of words in a way you will never forget. Even now, the memory lingers.

How could a few small words have such a big impact on your life?

Words have power . And only when you experienced that power yourself — either as the giver or as the receiver — did you begin to understand it.

You can use the power of words to heal or comfort others. Or you can use it to tear them down. Your character shapes and is shaped by the way you use this power.

So, how can you make the most of it?

Examples of the Power of Spoken Words

Examples of the power of written words, why are words so powerful for humans, 1. speak the truth., 2. avoid exaggerations., 3. don’t use double standards., 4. don’t use your words to manipulate others., 5. be consistent in what you say., 6. speak mindfully., 7. use words to benefit others..

When was the last time you heard spoken words that changed your perspective on something or someone? Maybe the words felt like a sucker punch.

Or maybe they lit you up inside and inspired you to make a change.

Consider the following examples of spoken words:

- Speeches and Lectures

- Song Lyrics

- Conversations (spoken)

- Audiobooks or Podcasts

- Movies or TV shows

Now, see if you can recall any memories of negative words for each of these samples.

Are there songs you find difficult to listen to because of the negative lyrics? Or have you been avoiding someone because of a recent negative outburst?

Maybe you’re thinking of negative words you’ve never heard but that felt, in your mind, as though they’d been spoken aloud – and directly to you.

Guess what’s next.

Written words also have power — for the one who writes them and for those who read them.

You’ve felt this power. And maybe you’ve wielded it yourself.

Maybe you even consider it your superpower. You’re not wrong to call it that.

Consider the following examples:

- Journal entries

- Articles / Blog Posts

- Letters, Notes, and Emails

- Stories and Poems

- Awards / Commendations or Written Reprimands

- Books and Book Reviews

Never underestimate the power of a thoughtful note — or a love poem — or a compelling story.

The right words draw you in and build connections. The wrong words destroy relationships or prevent them from ever being built.

This is why marketers pay well for effective copywriting .

If your words can connect with your target audience and persuade them that paying for a particular product or service will change their life for the better, you most definitely have a superpower.

Use it for good.

Humans are the only species on this planet that has the power of speech and of the written word (as far as we know).

But in spite of the creative potential this power gives us, we spend more time exploring its destructive potential.

And we sabotage our own health and happiness when we do.

According to functional MRI scans (fMRI ), just looking at a list of negative words (including the word “NO”) worsens anxiety and depression.

And dwelling on those words can actually damage key structures in the brain — including those responsible for memory, feelings, and emotions.

Vocalizing that negativity releases more stress hormones, not only in you but in those who hear you.

Even silent worrying (about money, relationships, work, etc.) stimulates the release of neurochemicals that make you and those around you feel worse.

Empaths are particularly sensitive to this, but everyone around you is affected to some degree. And you as the ruminator suffer the most.

So, how can you turn things around?

7 Tips for Making Your Written and Spoken Words Powerful

“Words have the power to both destroy and heal. When words are both true and kind, they can change our world.” — Gautama Buddha

Trust is built on honesty; people want to know they can depend on you to tell them the truth, even when it hurts to hear it (and even if it makes you look bad).

There are times when lying can save a life. But in most cases, with relationships, a reputation for lying will rob you of your power to connect with them.

Without truth behind them, your words lose their meaning and become empty noise.

Saying “You never….” or “You always…” to berate others ensures that your negative message about them (which is personal) will eclipse whatever message you’re trying to send.

Very few people are consistent enough to “always” leave the toilet seat up or to “never” take out the garbage. And they know that.

So, if you accuse them of a perfect record of thoughtlessness, their own disagreement with your memory will make it difficult to pick up on the underlying request.

Double standards are when you have different rules or different expectations of two or more different people of equal ability in the same situation.

For example, if your employer, Biff, tells one employee, Jack, that all he needs to do is X and Y but then he tells Sally she’ll have to X, Y, and Z — and in less time — to receive the same reward (or 79% of it), he’s using the power of words (and money) to impose a double standard.

And once he does and word gets around, Biff’s own words will create an atmosphere of injustice.

No one wants to work for an employer who devalues and exploits others.

More Related Articles

9 Of The Best Writing Podcasts For Authors In 2019

12 Effective Tips On How To Write Faster

15 Common Grammar Mistakes That Kill Your Writing Credibility

Marketing isn’t about using words to pressure or manipulate people into spending their money on whatever you’re selling.

Neither is it about competing with other marketers to see who can use their words more effectively to make customers feel things.

If the only reason you’re trying to build a connection is to get something from the other person, they’ll pick up on that.

And even if you do persuade them to buy something, it’ll leave skid marks in their memory.

They’ll remember you as someone who used the power of words to line your own pockets at their expense. And their regret is your loss.

Consistency is saying or doing the same thing regardless of the circumstances, as long as those words or actions still apply.

It is possible to overdo consistency. And none of us is perfect.

But when it comes to the power of words, you don’t want to give anyone the impression that your words and actions will change whenever you feel the slightest pressure to change them — regardless of the consequences.

If someone’s words change too easily, they’re the verbal equivalent of shifting sands. You can’t build anything on them that won’t fall apart.

Fickle words have no power.

A daily mindfulness practice trains you to be aware of your thoughts and feelings, without judging them.

So, you can acknowledge that someone’s words or actions have made you feel devalued or manipulated.

But you don’t have to avenge your ego by using words as defense weapons.

You retain your power when you take a step back and use your words to restore balance instead.

When you use the power of beautiful words to express empathy rather than anger or condescension, you put the good of the souls involved ahead of your own impulses. You might also enjoy these mindfulness journal prompts .

Karma demands that we pay for every unkind word we speak or write. Every time we use the power of words against another soul, we guarantee that, sooner or later, we’ll experience the same pain we’ve inflicted.

Think of that the next time you look back at a conversation and wish you’d used the comeback that came to mind a half-hour later.

Or, better yet, think of that when you’re about to say (or write) a scathing response to someone who has verbally attacked you.

Even if you succeed in turning their own words against them, you’ll eventually realize that the victory wasn’t worth the alienation you caused.

Use your power to build them up instead.

Will you take advantage of the power of words?

Asking questions instead of resting on statements is another way to benefit from the power of words.

Questions open your mind, while statements (assumptions, snap judgments, and fixed beliefs) close it.

If you pride yourself on keeping an open mind — about people, ideas, and situations — you should be using words to ask more questions rather than to utter statements no one is allowed to question.

The words you speak can either promote growth and connection or undermine it.

Take a moment today to think of the words you want to be remembered for. Before you speak, think of the words you’d want to say if they were your last.

May the words you choose bless everyone who hears (or reads) them today.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Power of Words

- Lucy Swedberg

How language connects, differentiates, and enlightens us

Four new books investigate how language connects, differentiates, and enlightens us. Viorica Marian’s The Power of Language explores the benefits of multilingualism. People who are multilingual perform better on executive-functioning tasks, for instance, and draw more novel connections.

In A Myriad of Tongues, author Caleb Everett notes that more than 7,000 languages exist today. And while academics traditionally looked for commonalities among languages, recent research has focused on how languages diverge, and what those differences can teach us.

A third book, Magic Words, by Wharton professor Jonah Berger, examines how specific words can carry an oversize impact, making them more likely to change hearts and minds or drive change.

By contrast, Dan Lyons’s STFU reminds readers that sometimes saying nothing is the best approach. “All of us,” he writes, “stand to gain by speaking less, listening more, and communicating with intention.” His book offers advice on how to do that, whether online, at work, or at home.

About a year ago, a friend suggested that I enroll in an adult tap-dance class held at our town’s community center. The suggestion wasn’t as random as it might seem. For nearly two decades in my youth, I had loved tapping in classes and onstage. And when I laced up those black leather shoes after a nearly 20-year hiatus, I felt instantly at home.

- LS Lucy Swedberg is an executive editor at Harvard Business Publishing, focused on education.

Partner Center

- Watch WCCM+

- Book Reviews , News & Updates

The Power of Words, Simone Weil

- 15 October, 2021

Simone Weil wrote the essay, ‘The Power of Words’ , when she was twenty-five after she returned from the Spanish Civil War where she had joined the Republican faction. Weil had already visited Germany in 1932 where she was concerned about the rise of the fascists, her concerns validated after Hitler rose to power in 1933. It was during this social and political turmoil in Europe, on the brink of World War II, that Weil’s prophetic voice rang out in this searing essay. But her diagnosis of what besets contemporary society in her time can still speak to us today.

For Weil, the mis-use of words—the way they are used to obscure rather than grasp reality—was leading society into unending conflict. The greatest danger she saw unfolding was the use of ‘empty words’ given ‘capital letters’ that were used as a banner or hostile slogan, by means of which, “on the slightest pretext, men will begin shedding blood for them and piling up ruin in their name, without effectively grasping anything to which they refer…”. It is their very lack of meaning that makes it impossible to define clear objectives in a conflict or to measure whether the cost justifies the effort—and sacrifices—it demands. The result is that in such conflicts the only barometer of success is the extermination of the enemy.

For Weil, this gave contemporary conflict its unreal nature, based as it was on the use of words that do not refer to concrete reality but abstract entities. Words misused in her time, but also in ours, include those such as: nation, security, capitalism, communism, fascism, order, authority, property and democracy. “If we grasp one of these words,” Simone Weil writes, “all swollen with blood and tears, and squeeze it, we find it is empty. Words with content and meaning are not murderous.”

Take for example, the words ‘nation’ and ‘national interest.’ Weil contends that if we examine the way these terms have been used in modern history, the national interest of every State has been in retaining its capacity to make war, while at the same time depriving all other countries of it. Yet our leaders will call forth people to defend the ‘nation’ and the ‘national interest,’ as if there were a real opposition of interest between nations. If that were the case, she argues, nations would be able to negotiate and bargain for their interests. These calls amount to nothing other than defending the nation’s capacity to make war. “For the word national and the expressions of which it forms part are empty of all meaning; their only content is millions of corpses, and orphans, and disabled men, and tears and despair.”

Take for example, the words ‘nation’ and ‘national interest.’ Weil contends that if we examine the way these terms have been used in modern history, the national interest of every State has been in retaining its capacity to make war, while at the same time depriving all other countries of it.

Empty words then are illusory, meaning everything and nothing; but they are attached to real, material things. Although the word ‘nation’ and the way it is used in sloganeering is abstract and empty, the State and its affiliated apparatuses is very real. The supposed opposition between fascism and communism was an imaginary distinction for Weil, on closer analysis she believed they actually reflected “identical political and social conceptions.” But in her time, two very real oppositional political organisations existed whose aim was complete power and elimination of the other, with people on both sides willing to die and to kill for these words. “Corresponding to each empty abstraction there is an actual human group…”

Weil’s diagnosis was that words were no longer used as signs to help us grasp some aspect of concrete reality. But even more dire than that, she argued that we have also lost the capacity to use words with measure and proportion. Phrases such as ‘to the extent that’ and ideas such as degree, limit, comparison, contingency and interdependence, amongst others, are no longer used. For example, “There is democracy to the extent that … or: There is capitalism in so far as …” Instead, words are used as if reflecting an absolute, immutable reality, and “at the same time we make all these words mean, successively or simultaneously, anything whatsoever.”

Words lose their meaning when they become reified as things in themselves, rather than the means to judge and ascertain the state of social structures. We essentialise people and parties as belonging inherently to certain words like dictatorship or democracy, such that, “our political universe is peopled exclusively by myths and monsters; all it contains is absolutes and abstract entities.” We seek to crush those who belong to the ‘other’ side of that abstract word. We don’t seek to examine the variations, the changing causes of phenomena, the specific conditions that give rise to them, and the limits within which they occur, in order to come up with solutions that have some discernment; solutions that actually might work because they address specific issues and have concrete objectives, other than just defeating the other side. Instead, “we act and strive and sacrifice ourselves and others by reference to fixed and isolated abstractions…”

These words resonate across the more than eighty years since Weil wrote them. It could be argued that a lack of nuance, measure and proportion in how we use our words and in our thinking is a real mark of our times. In the age of social media, clickbait, and ‘content’ creation, much discussion is levelled out to bitesize pieces, to easy arguments where you’re either for or against, to a descent into facile comparisons. The poet Kaveh Akbar made this point about why he needed time off from Twitter:

“On social media, the same rhetorical language was being used about the casting of some Marvel movie as about the leveling of a village in Syria. The same exact rhetorical algorithms of outrage were used to talk about one as the other. Our brains haven’t evolved enough to differentiate between the two. Language is language. And so I was just not in command of my compassion, the distribution and focus of my rage, and it took a while to recalibrate.”

Short attention spans and a tendency towards simplification have perhaps always existed, but this seems to be turbo charged in our current era, where the ‘content’ that reaches us is often determined by algorithms that increasingly seal us off into echo chambers. In our pandemic times this is nowhere more illustrated than in the vaccination debate. Either you are unequivocally for vaccines and worship at the altar of medical science, or you are an anti-vaxxer and believer of vast and incredible conspiracies, mainly linked to the threat of our supposed freedom. Each side goes to ‘war’ with the other with no real measure of what the multiple issues are, no discernment about how what is true is dependent on certain conditions (instead vaccines are either always good, or always bad) and in relation to a host of factors.

It is true that social media has provided a powerful platform for marginalised groups in society. Giving a voice to groups of people who have been previously left out is to be lauded, as it is redistributing some of the power (if power is also about having a platform to be heard), and there have been many instances of social media being used to mobilise movements such as #MeToo and pro-democracy protests such as the Umbrella Movement (as well as its opposite).

Source image: Wikimedia

But the nature of the platform—word limits, algorithms, scrolling that has fractured our attention—has also meant that it has flattened a lot of debate. Debate is also a good word that characterizes much of the discourse on social media, focused as it is more on winning an argument rather than having a conversation or discussion, where there might be mutual listening and an attempt to understand the ‘other side.’

In discussions of the issues of the day, we can’t seem to hold differing ideas or understandings in tension for long enough to explore nuance, tease out implications, bring underlying assumptions or commitments to the surface. By contrast, the measured and proportionate words Weil advocates the use of can allow us to discern and grasp the fuller meaning and reality of something ; and if nothing is absolute, then it becomes possible to entertain the fact that a seemingly contradictory thing can also be true, to a certain extent.

We need to determine to what extent the nuances of conflicting things can be true if we are to apprehend reality properly rather than flattening it out—if we are to propose goals and solutions that actually address concrete issues rather than just merely be used for abstract sloganeering and banner waving. In that sense, for our times Weil’s call to revive the use of expressions like to the extent that, in so far as, on condition that, in relation to, is more necessary than ever.

Discernment, analysis, measured words —these are the tools which could be an antidote against what Weil termed “the swarm of vacuous entities or abstractions.” Perhaps even more than in her time, our contemporary culture cultivates this ‘swarm.’ The pandemic might have been a time for us to sit back and reflect on what we are doing and where we are headed, individually and as a society. As the world slowly opens up again, will we retreat to how things were before the pandemic, continuing to move at a breakneck pace, or will we have learnt from the past couple of years, where perhaps a space has opened up for questioning business as usual?

In Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future , Pope Francis touches on the need to rediscover the art of discernment . This is surely connected to Weil’s appeal to a greater discernment in how we use words, so that outcomes are based on apprehending the reality of a given situation and addressing concrete objectives, rather than the desire to compete and win against our supposed opponents.

This call for discernment is also surely linked to a contemplative approach not only to social and political issues, but also to the way in which we individually and institutionally engage in processes that are capable of this discernment, reflection and mutual listening. As Sarah Bachelard terms it, this way of being could form the basis of a ‘contemplative politics.’ She asks:

The words we use will be of significance in this process. As Weil understood, words have the power to illuminate, but also to obscure; to lead to unending conflict, but also to greater consciousness.

‘The Power of Words’ essay published in Simone Weil : An Anthology, edited and introduced by Sian Miles (Penguin Modern Classics)

Featured image source: Google Images

3 thoughts on “The Power of Words, Simone Weil”

This article seems to skirt the real issues we face with regard to words today – that being the suppression of free speech (called misinformation/disinformation) with the resultant cancellation of persons in the most cruel ways. Never have I seen such a world of lies. Words are being misused. Meanings of words are being altered (vaccine definition altered to accommodate the fact that the vax does not give immunity) New words are being created (e.g. the gender identity phenomena) Platforms for conversation have become a means of propagandizing rather than discussing – via algorithms. Twitter leadership , for instance, has an agenda, and it does not serve free speech. We are at a transformational point in history where things can go very badly.

What we have to recognize is the use of words that promote international authoritarianism. Even movements concerning the environment are being used by these authoritarians with “words” that appeal to good-hearted people but at their core will lead to power being concentrated in the hands of those who really seek control over others. Look at the ACTIONS, rather than the words of the “climate crisis” pied pipers. They live in luxury, travel on private planes to climate conferences, AND they refuse to use their words to challenge the world’s biggest polluters. Why? Fear of retaliation? What is your “social score”?

Where is TRUTH in all these words we hear in the media? Our words must serve freedom and truth. “By their fruits, you shall know them.” Not by their words.

My worst word is refugie crise. It is a word that puts the Rich countries in Europe in the center. But the real crises are the War, the narko produktion and the hunger, which make people flee their homelands. You could say the same about climatcrise. The climat is the climat and Can not be in crisis. But our society is in crisis because of our own behavour. The climate just react naturally on our inpact. By calling the two subjects crisis our responsability is blurred.

This article really makes me think about the words i use, and to really examine where i stand on some of the “issues” of our day. Simone Weil is an author i need to read and discuss with others.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Related Posts

From Anxiety to Peace a Hybrid Conference Retreat Canada

Meditation with Children – WCCM Indonesia

We’re all seekers

Join the mailing list.

Receive weekly mailings to support your meditation journey and your daily practice.

Get the App

A great companion for your meditation practice, the app includes a simple meditation timer as well as the latest news and resources from WCCM.

Support the WCCM

Any gift, no matter how small, will help us sustain this work and achieve our mission of nurturing Christian meditation inclusively around a world in greater need than ever of contemplative wisdom.

Watch & Listen

Get involved, start typing and press enter to search.

May 23, 2024

published by phi beta kappa

Print or web publication, king, kennedy, and the power of words.

How candor and poetry can change the course of history

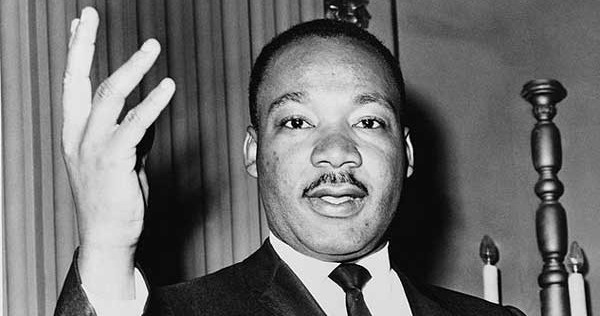

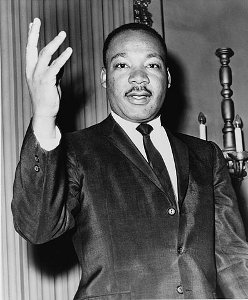

The night of April 4, 1968, presidential candidate Robert Kennedy received the news that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Kennedy was about to speak in Indianapolis and some in his campaign wondered if they should go ahead with the rally.

Moments before Kennedy climbed onto a flatbed truck to address the crowd, which had gathered in a light rain, press secretary Frank Mankiewicz gave the candidate a sheet a paper with ideas of what he might say. Kennedy slid it into his pocket without looking at it. Another aide approached with more notes and the candidate waved him away.

“Do they know about Martin Luther King?” Kennedy asked those gathered on the platform. No, came the reply.

After asking the crowd to lower its campaign signs, Kennedy told his audience that King had been shot and killed earlier in Memphis. Gasps went up from the crowd and for a moment everything seemed ready to come apart. Indianapolis might have joined other cities across America that burned on that awful night.

But then Kennedy, beginning in a trembling, halting voice, slowly brought the people back around and somehow held them together. Listening to the speech decades later is to be reminded of the real power of words. How they can heal, how they can still bring us together, but only if they are spoken with conviction and from the heart.

Compare what we often hear from politicians today to what Kennedy said on that tragic night in Indianapolis. He told the crowd how he “had a member of my family killed”—a reference to his brother John, who had been assassinated less than five years before.

Later on, Kennedy recited a poem by Aeschylus, which he had memorized long before that trying night in Indianapolis:

Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget Falls drop by drop upon the heart, Until, in our own despair, against our will, Comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.

Kennedy’s heartfelt speech came only hours after King’s last address. The night before, the civil rights leader had reluctantly taken to the dais at the Mason Temple in Memphis . The weather that evening had been miserable—thunderstorms and tornado warnings. As a result, King arrived late and was just going to say a few words and then tell everyone to please go home.

Visibly tired and with no notes in hand, King stumbled at first. The shutters hitting against the temple walls sounded like gun shots to him. So much so that King’s friend, the Rev. Billy Kyles, found a custodian to stop the noise. Only then, at the crowd’s urging, did the words begin to come together for King.

“We’ve got some difficult days ahead,” he said that night. “But it really doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop.”

King closed by telling the crowd, “… we as a people will get to the Promised Land. So I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. …”

Novelist Charles Baxter contends that the greatest influence on American writing and discourse in recent memory can be traced back to the phrase “Mistakes were made.” Of course, that’s from Watergate and the shadowy intrigue inside the Nixon White House. In his essay, “Burning Down the House,” Baxter compares that “quasi-confessional passive-voice-mode sentence” to what Robert E. Lee said after the battle of Gettysburg and the disastrous decision of Pickett’s Charge.

“All of this has been my fault,” the Confederate general said. “I asked more of the men than should have been asked of them.”

In Lee’s words, and those of King and Kennedy, we hear a refreshing candor and directness that we miss today. In 1968, people responded to what King and Kennedy told them. During that tumultuous 24-hour period in 1968, people cried aloud and chanted in Memphis. Words struck a chord in Indianapolis, too, and decades later former mayor (and now U.S. Senator) Richard Lugar told writer Thurston Clarke that Kennedy’s speech was “a turning point” for his city.

After King’s assassination, riots broke out in more than 100 U.S. cities—the worst destruction since the Civil War . But neither Memphis nor Indianapolis experienced that kind of damage. To this day, many believe that was due to the words spoken when so many were listening.

Tim Wendel is the author most recently of Summer of ’68: The Season That Changed Baseball, and America, Forever.

● NEWSLETTER

TED is supported by ads and partners 00:00

The Power of Words

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Language and power.

- Sik Hung Ng Sik Hung Ng Department of Psychology, Renmin University of China

- and Fei Deng Fei Deng School of Foreign Studies, South China Agricultural University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.436

- Published online: 22 August 2017

Five dynamic language–power relationships in communication have emerged from critical language studies, sociolinguistics, conversation analysis, and the social psychology of language and communication. Two of them stem from preexisting powers behind language that it reveals and reflects, thereby transferring the extralinguistic powers to the communication context. Such powers exist at both the micro and macro levels. At the micro level, the power behind language is a speaker’s possession of a weapon, money, high social status, or other attractive personal qualities—by revealing them in convincing language, the speaker influences the hearer. At the macro level, the power behind language is the collective power (ethnolinguistic vitality) of the communities that speak the language. The dominance of English as a global language and international lingua franca, for example, has less to do with its linguistic quality and more to do with the ethnolinguistic vitality of English-speakers worldwide that it reflects. The other three language–power relationships refer to the powers of language that are based on a language’s communicative versatility and its broad range of cognitive, communicative, social, and identity functions in meaning-making, social interaction, and language policies. Such language powers include, first, the power of language to maintain existing dominance in legal, sexist, racist, and ageist discourses that favor particular groups of language users over others. Another language power is its immense impact on national unity and discord. The third language power is its ability to create influence through single words (e.g., metaphors), oratories, conversations and narratives in political campaigns, emergence of leaders, terrorist narratives, and so forth.

- power behind language

- power of language

- intergroup communication

- World Englishes

- oratorical power

- conversational power

- leader emergence

- al-Qaeda narrative

- social identity approach

Introduction

Language is for communication and power.

Language is a natural human system of conventionalized symbols that have understood meanings. Through it humans express and communicate their private thoughts and feelings as well as enact various social functions. The social functions include co-constructing social reality between and among individuals, performing and coordinating social actions such as conversing, arguing, cheating, and telling people what they should or should not do. Language is also a public marker of ethnolinguistic, national, or religious identity, so strong that people are willing to go to war for its defense, just as they would defend other markers of social identity, such as their national flag. These cognitive, communicative, social, and identity functions make language a fundamental medium of human communication. Language is also a versatile communication medium, often and widely used in tandem with music, pictures, and actions to amplify its power. Silence, too, adds to the force of speech when it is used strategically to speak louder than words. The wide range of language functions and its versatility combine to make language powerful. Even so, this is only one part of what is in fact a dynamic relationship between language and power. The other part is that there is preexisting power behind language which it reveals and reflects, thereby transferring extralinguistic power to the communication context. It is thus important to delineate the language–power relationships and their implications for human communication.

This chapter provides a systematic account of the dynamic interrelationships between language and power, not comprehensively for lack of space, but sufficiently focused so as to align with the intergroup communication theme of the present volume. The term “intergroup communication” will be used herein to refer to an intergroup perspective on communication, which stresses intergroup processes underlying communication and is not restricted to any particular form of intergroup communication such as interethnic or intergender communication, important though they are. It echoes the pioneering attempts to develop an intergroup perspective on the social psychology of language and communication behavior made by pioneers drawn from communication, social psychology, and cognate fields (see Harwood et al., 2005 ). This intergroup perspective has fostered the development of intergroup communication as a discipline distinct from and complementing the discipline of interpersonal communication. One of its insights is that apparently interpersonal communication is in fact dynamically intergroup (Dragojevic & Giles, 2014 ). For this and other reasons, an intergroup perspective on language and communication behavior has proved surprisingly useful in revealing intergroup processes in health communication (Jones & Watson, 2012 ), media communication (Harwood & Roy, 2005 ), and communication in a variety of organizational contexts (Giles, 2012 ).

The major theoretical foundation that has underpinned the intergroup perspective is social identity theory (Tajfel, 1982 ), which continues to service the field as a metatheory (Abrams & Hogg, 2004 ) alongside relatively more specialized theories such as ethnolinguistic identity theory (Harwood et al., 1994 ), communication accommodation theory (Palomares et al., 2016 ), and self-categorization theory applied to intergroup communication (Reid et al., 2005 ). Against this backdrop, this chapter will be less concerned with any particular social category of intergroup communication or variant of social identity theory, and more with developing a conceptual framework of looking at the language–power relationships and their implications for understanding intergroup communication. Readers interested in an intra- or interpersonal perspective may refer to the volume edited by Holtgraves ( 2014a ).

Conceptual Approaches to Power

Bertrand Russell, logician cum philosopher and social activist, published a relatively little-known book on power when World War II was looming large in Europe (Russell, 2004 ). In it he asserted the fundamental importance of the concept of power in the social sciences and likened its importance to the concept of energy in the physical sciences. But unlike physical energy, which can be defined in a formula (e.g., E=MC 2 ), social power has defied any such definition. This state of affairs is not unexpected because the very nature of (social) power is elusive. Foucault ( 1979 , p. 92) has put it this way: “Power is everywhere, not because it embraces everything, but because it comes from everywhere.” This view is not beyond criticism but it does highlight the elusiveness of power. Power is also a value-laden concept meaning different things to different people. To functional theorists and power-wielders, power is “power to,” a responsibility to unite people and do good for all. To conflict theorists and those who are dominated, power is “power over,” which corrupts and is a source of social conflict rather than integration (Lenski, 1966 ; Sassenberg et al., 2014 ). These entrenched views surface in management–labor negotiations and political debates between government and opposition. Management and government would try to frame the negotiation in terms of “power to,” whereas labor and opposition would try to frame the same in “power over” in a clash of power discourses. The two discourses also interchange when the same speakers reverse their power relations: While in opposition, politicians adhere to “power over” rhetorics, once in government, they talk “power to.” And vice versa.

The elusive and value-laden nature of power has led to a plurality of theoretical and conceptual approaches. Five approaches that are particularly pertinent to the language–power relationships will be discussed, and briefly so because of space limitation. One approach views power in terms of structural dominance in society by groups who own and/or control the economy, the government, and other social institutions. Another approach views power as the production of intended effects by overcoming resistance that arises from objective conflict of interests or from psychological reactance to being coerced, manipulated, or unfairly treated. A complementary approach, represented by Kurt Lewin’s field theory, takes the view that power is not the actual production of effects but the potential for doing this. It looks behind power to find out the sources or bases of this potential, which may stem from the power-wielders’ access to the means of punishment, reward, and information, as well as from their perceived expertise and legitimacy (Raven, 2008 ). A fourth approach views power in terms of the balance of control/dependence in the ongoing social exchange between two actors that takes place either in the absence or presence of third parties. It provides a structural account of power-balancing mechanisms in social networking (Emerson, 1962 ), and forms the basis for combining with symbolic interaction theory, which brings in subjective factors such as shared social cognition and affects for the analysis of power in interpersonal and intergroup negotiation (Stolte, 1987 ). The fifth, social identity approach digs behind the social exchange account, which has started from control/dependence as a given but has left it unexplained, to propose a three-process model of power emergence (Turner, 2005 ). According to this model, it is psychological group formation and associated group-based social identity that produce influence; influence then cumulates to form the basis of power, which in turn leads to the control of resources.

Common to the five approaches above is the recognition that power is dynamic in its usage and can transform from one form of power to another. Lukes ( 2005 ) has attempted to articulate three different forms or faces of power called “dimensions.” The first, behavioral dimension of power refers to decision-making power that is manifest in the open contest for dominance in situations of objective conflict of interests. Non-decision-making power, the second dimension, is power behind the scene. It involves the mobilization of organizational bias (e.g., agenda fixing) to keep conflict of interests from surfacing to become public issues and to deprive oppositions of a communication platform to raise their voices, thereby limiting the scope of decision-making to only “safe” issues that would not challenge the interests of the power-wielder. The third dimension is ideological and works by socializing people’s needs and values so that they want the wants and do the things wanted by the power-wielders, willingly as their own. Conflict of interests, opposition, and resistance would be absent from this form of power, not because they have been maneuvered out of the contest as in the case of non-decision-making power, but because the people who are subject to power are no longer aware of any conflict of interest in the power relationship, which may otherwise ferment opposition and resistance. Power in this form can be exercised without the application of coercion or reward, and without arousing perceived manipulation or conflict of interests.

Language–Power Relationships

As indicated in the chapter title, discussion will focus on the language–power relationships, and not on language alone or power alone, in intergroup communication. It draws from all the five approaches to power and can be grouped for discussion under the power behind language and the power of language. In the former, language is viewed as having no power of its own and yet can produce influence and control by revealing the power behind the speaker. Language also reflects the collective/historical power of the language community that uses it. In the case of modern English, its preeminent status as a global language and international lingua franca has shaped the communication between native and nonnative English speakers because of the power of the English-speaking world that it reflects, rather than because of its linguistic superiority. In both cases, language provides a widely used conventional means to transfer extralinguistic power to the communication context. Research on the power of language takes the view that language has power of its own. This power allows a language to maintain the power behind it, unite or divide a nation, and create influence.

In Figure 1 we have grouped the five language–power relationships into five boxes. Note that the boundary between any two boxes is not meant to be rigid but permeable. For example, by revealing the power behind a message (box 1), a message can create influence (box 5). As another example, language does not passively reflect the power of the language community that uses it (box 2), but also, through its spread to other language communities, generates power to maintain its preeminence among languages (box 3). This expansive process of language power can be seen in the rise of English to global language status. A similar expansive process also applies to a particular language style that first reflects the power of the language subcommunity who uses the style, and then, through its common acceptance and usage by other subcommunities in the country, maintains the power of the subcommunity concerned. A prime example of this type of expansive process is linguistic sexism, which reflects preexisting male dominance in society and then, through its common usage by both sexes, contributes to the maintenance of male dominance. Other examples are linguistic racism and the language style of the legal profession, each of which, like linguistic sexism and the preeminence of the English language worldwide, has considerable impact on individuals and society at large.

Space precludes a full discussion of all five language–power relationships. Instead, some of them will warrant only a brief mention, whereas others will be presented in greater detail. The complexity of the language–power relations and their cross-disciplinary ramifications will be evident in the multiple sets of interrelated literatures that we cite from. These include the social psychology of language and communication, critical language studies (Fairclough, 1989 ), sociolinguistics (Kachru, 1992 ), and conversation analysis (Sacks et al., 1974 ).

Figure 1. Power behind language and power of language.

Power Behind Language

Language reveals power.

When negotiating with police, a gang may issue the threatening message, “Meet our demands, or we will shoot the hostages!” The threatening message may succeed in coercing the police to submit; its power, however, is more apparent than real because it is based on the guns gangsters posses. The message merely reveals the power of a weapon in their possession. Apart from revealing power, the gangsters may also cheat. As long as the message comes across as credible and convincing enough to arouse overwhelming fear, it would allow them to get away with their demands without actually possessing any weapon. In this case, language is used to produce an intended effect despite resistance by deceptively revealing a nonexisting power base and planting it in the mind of the message recipient. The literature on linguistic deception illustrates the widespread deceptive use of language-reveals-power to produce intended effects despite resistance (Robinson, 1996 ).

Language Reflects Power

Ethnolinguistic vitality.

The language that a person uses reflects the language community’s power. A useful way to think about a language community’s linguistic power is through the ethnolinguistic vitality model (Bourhis et al., 1981 ; Harwood et al., 1994 ). Language communities in a country vary in absolute size overall and, just as important, a relative numeric concentration in particular regions. Francophone Canadians, though fewer than Anglophone Canadians overall, are concentrated in Quebec to give them the power of numbers there. Similarly, ethnic minorities in mainland China have considerable power of numbers in those autonomous regions where they are concentrated, such as Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Collectively, these factors form the demographic base of the language community’s ethnolinguistic vitality, an index of the community’s relative linguistic dominance. Another base of ethnolinguistic vitality is institutional representations of the language community in government, legislatures, education, religion, the media, and so forth, which afford its members institutional leadership, influence, and control. Such institutional representation is often reinforced by a language policy that installs the language as the nation’s sole official language. The third base of ethnolinguistic vitality comprises sociohistorical and cultural status of the language community inside the nation and internationally. In short, the dominant language of a nation is one that comes from and reflects the high ethnolinguistic vitality of its language community.

An important finding of ethnolinguistic vitality research is that it is perceived vitality, and not so much its objective demographic-institutional-cultural strengths, that influences language behavior in interpersonal and intergroup contexts. Interestingly, the visibility and salience of languages shown on public and commercial signs, referred to as the “linguistic landscape,” serve important informational and symbolic functions as a marker of their relative vitality, which in turn affects the use of in-group language in institutional settings (Cenoz & Gorter, 2006 ; Landry & Bourhis, 1997 ).

World Englishes and Lingua Franca English

Another field of research on the power behind and reflected in language is “World Englishes.” At the height of the British Empire English spread on the back of the Industrial Revolution and through large-scale migrations of Britons to the “New World,” which has since become the core of an “inner circle” of traditional native English-speaking nations now led by the United States (Kachru, 1992 ). The emergent wealth and power of these nations has maintained English despite the decline of the British Empire after World War II. In the post-War era, English has become internationalized with the support of an “outer circle” nations and, later, through its spread to “expanding circle” nations. Outer circle nations are made up mostly of former British colonies such as India, Pakistan, and Nigeria. In compliance with colonial language policies that institutionalized English as the new colonial national language, a sizeable proportion of the colonial populations has learned and continued using English over generations, thereby vastly increasing the number of English speakers over and above those in the inner circle nations. The expanding circle encompasses nations where English has played no historical government roles, but which are keen to appropriate English as the preeminent foreign language for local purposes such as national development, internationalization of higher education, and participation in globalization (e.g., China, Indonesia, South Korea, Japan, Egypt, Israel, and continental Europe).

English is becoming a global language with official or special status in at least 75 countries (British Council, n.d. ). It is also the language choice in international organizations and companies, as well as academia, and is commonly used in trade, international mass media, and entertainment, and over the Internet as the main source of information. English native speakers can now follow the worldwide English language track to find jobs overseas without having to learn the local language and may instead enjoy a competitive language advantage where the job requires English proficiency. This situation is a far cry from the colonial era when similar advantages had to come under political patronage. Alongside English native speakers who work overseas benefitting from the preeminence of English over other languages, a new phenomenon of outsourcing international call centers away from the United Kingdom and the United States has emerged (Friginal, 2007 ). Callers can find the information or help they need from people stationed in remote places such as India or the Philippines where English has penetrated.

As English spreads worldwide, it has also become the major international lingua franca, serving some 800 million multilinguals in Asia alone, and numerous others elsewhere (Bolton, 2008 ). The practical importance of this phenomenon and its impact on English vocabulary, grammar, and accent have led to the emergence of a new field of research called “English as a lingua franca” (Brosch, 2015 ). The twin developments of World Englishes and lingua franca English raise interesting and important research questions. A vast area of research lies in waiting.

Several lines of research suggest themselves from an intergroup communication perspective. How communicatively effective are English native speakers who are international civil servants in organizations such as the UN and WTO, where they habitually speak as if they were addressing their fellow natives without accommodating to the international audience? Another line of research is lingua franca English communication between two English nonnative speakers. Their common use of English signals a joint willingness of linguistic accommodation, motivated more by communication efficiency of getting messages across and less by concerns of their respective ethnolinguistic identities. An intergroup communication perspective, however, would sensitize researchers to social identity processes and nonaccommodation behaviors underneath lingua franca communication. For example, two nationals from two different countries, X and Y, communicating with each other in English are accommodating on the language level; at the same time they may, according to communication accommodation theory, use their respective X English and Y English for asserting their ethnolinguistic distinctiveness whilst maintaining a surface appearance of accommodation. There are other possibilities. According to a survey of attitudes toward English accents, attachment to “standard” native speaker models remains strong among nonnative English speakers in many countries (Jenkins, 2009 ). This suggests that our hypothetical X and Y may, in addition to asserting their respective Englishes, try to outperform one another in speaking with overcorrect standard English accents, not so much because they want to assert their respective ethnolinguistic identities, but because they want to project a common in-group identity for positive social comparison—“We are all English-speakers but I am a better one than you!”

Many countries in the expanding circle nations are keen to appropriate English for local purposes, encouraging their students and especially their educational elites to learn English as a foreign language. A prime example is the Learn-English Movement in China. It has affected generations of students and teachers over the past 30 years and consumed a vast amount of resources. The results are mixed. Even more disturbing, discontents and backlashes have emerged from anti-English Chinese motivated to protect the vitality and cultural values of the Chinese language (Sun et al., 2016 ). The power behind and reflected in modern English has widespread and far-reaching consequences in need of more systematic research.

Power of Language

Language maintains existing dominance.

Language maintains and reproduces existing dominance in three different ways represented respectively by the ascent of English, linguistic sexism, and legal language style. For reasons already noted, English has become a global language, an international lingua franca, and an indispensable medium for nonnative English speaking countries to participate in the globalized world. Phillipson ( 2009 ) referred to this phenomenon as “linguistic imperialism.” It is ironic that as the spread of English has increased the extent of multilingualism of non-English-speaking nations, English native speakers in the inner circle of nations have largely remained English-only. This puts pressure on the rest of the world to accommodate them in English, the widespread use of which maintains its preeminence among languages.

A language evolves and changes to adapt to socially accepted word meanings, grammatical rules, accents, and other manners of speaking. What is acceptable or unacceptable reflects common usage and hence the numerical influence of users, but also the elites’ particular language preferences and communication styles. Research on linguistic sexism has shown, for example, a man-made language such as English (there are many others) is imbued with sexist words and grammatical rules that reflect historical male dominance in society. Its uncritical usage routinely by both sexes in daily life has in turn naturalized male dominance and associated sexist inequalities (Spender, 1998 ). Similar other examples are racist (Reisigl & Wodak, 2005 ) and ageist (Ryan et al., 1995 ) language styles.

Professional languages are made by and for particular professions such as the legal profession (Danet, 1980 ; Mertz et al., 2016 ; O’Barr, 1982 ). The legal language is used not only among members of the profession, but also with the general public, who may know each and every word in a legal document but are still unable to decipher its meaning. Through its language, the legal profession maintains its professional dominance with the complicity of the general public, who submits to the use of the language and accedes to the profession’s authority in interpreting its meanings in matters relating to their legal rights and obligations. Communication between lawyers and their “clients” is not only problematic, but the public’s continual dependence on the legal language contributes to the maintenance of the dominance of the profession.

Language Unites and Divides a Nation

A nation of many peoples who, despite their diverse cultural and ethnic background, all speak in the same tongue and write in the same script would reap the benefit of the unifying power of a common language. The power of the language to unite peoples would be stronger if it has become part of their common national identity and contributed to its vitality and psychological distinctiveness. Such power has often been seized upon by national leaders and intellectuals to unify their countries and serve other nationalistic purposes (Patten, 2006 ). In China, for example, Emperor Qin Shi Huang standardized the Chinese script ( hanzi ) as an important part of the reforms to unify the country after he had defeated the other states and brought the Warring States Period ( 475–221 bc ) to an end. A similar reform of language standardization was set in motion soon after the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty ( ad 1644–1911 ), by simplifying some of the hanzi and promoting Putonghua as the national standard oral language. In the postcolonial part of the world, language is often used to service nationalism by restoring the official status of their indigenous language as the national language whilst retaining the colonial language or, in more radical cases of decolonization, relegating the latter to nonofficial status. Yet language is a two-edged sword: It can also divide a nation. The tension can be seen in competing claims to official-language status made by minority language communities, protest over maintenance of minority languages, language rights at schools and in courts of law, bilingual education, and outright language wars (Calvet, 1998 ; DeVotta, 2004 ).

Language Creates Influence

In this section we discuss the power of language to create influence through single words and more complex linguistic structures ranging from oratories and conversations to narratives/stories.

Power of Single Words

Learning a language empowers humans to master an elaborate system of conventions and the associations between words and their sounds on the one hand, and on the other hand, categories of objects and relations to which they refer. After mastering the referential meanings of words, a person can mentally access the objects and relations simply by hearing or reading the words. Apart from their referential meanings, words also have connotative meanings with their own social-cognitive consequences. Together, these social-cognitive functions underpin the power of single words that has been extensively studied in metaphors, which is a huge research area that crosses disciplinary boundaries and probes into the inner workings of the brain (Benedek et al., 2014 ; Landau et al., 2014 ; Marshal et al., 2007 ). The power of single words extends beyond metaphors. It can be seen in misleading words in leading questions (Loftus, 1975 ), concessive connectives that reverse expectations from real-world knowledge (Xiang & Kuperberg, 2014 ), verbs that attribute implicit causality to either verb subject or object (Hartshorne & Snedeker, 2013 ), “uncertainty terms” that hedge potentially face-threatening messages (Holtgraves, 2014b ), and abstract words that signal power (Wakslak et al., 2014 ).

The literature on the power of single words has rarely been applied to intergroup communication, with the exception of research arising from the linguistic category model (e.g., Semin & Fiedler, 1991 ). The model distinguishes among descriptive action verbs (e.g., “hits”), interpretative action verbs (e.g., “hurts”) and state verbs (e.g., “hates”), which increase in abstraction in that order. Sentences made up of abstract verbs convey more information about the protagonist, imply greater temporal and cross-situational stability, and are more difficult to disconfirm. The use of abstract language to represent a particular behavior will attribute the behavior to the protagonist rather than the situation and the resulting image of the protagonist will persist despite disconfirming information, whereas the use of concrete language will attribute the same behavior more to the situation and the resulting image of the protagonist will be easier to change. According to the linguistic intergroup bias model (Maass, 1999 ), abstract language will be used to represent positive in-group and negative out-group behaviors, whereas concrete language will be used to represent negative in-group and positive out-group behaviors. The combined effects of the differential use of abstract and concrete language would, first, lead to biased attribution (explanation) of behavior privileging the in-group over the out-group, and second, perpetuate the prejudiced intergroup stereotypes. More recent research has shown that linguistic intergroup bias varies with the power differential between groups—it is stronger in high and low power groups than in equal power groups (Rubini et al., 2007 ).

Oratorical Power

A charismatic speaker may, by the sheer force of oratory, buoy up people’s hopes, convert their hearts from hatred to forgiveness, or embolden them to take up arms for a cause. One may recall moving speeches (in English) such as Susan B. Anthony’s “On Women’s Right to Vote,” Winston Churchill’s “We Shall Fight on the Beaches,” Mahatma Gandhi’s “Quit India,” or Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream.” The speech may be delivered face-to-face to an audience, or broadcast over the media. The discussion below focuses on face-to-face oratories in political meetings.

Oratorical power may be measured in terms of money donated or pledged to the speaker’s cause, or, in a religious sermon, the number of converts made. Not much research has been reported on these topics. Another measurement approach is to count the frequency of online audience responses that a speech has generated, usually but not exclusively in the form of applause. Audience applause can be measured fairly objectively in terms of frequency, length, or loudness, and collected nonobtrusively from a public recording of the meeting. Audience applause affords researchers the opportunity to explore communicative and social psychological processes that underpin some aspects of the power of rhetorical formats. Note, however, that not all incidences of audience applause are valid measures of the power of rhetoric. A valid incidence should be one that is invited by the speaker and synchronized with the flow of the speech, occurring at the appropriate time and place as indicated by the rhetorical format. Thus, an uninvited incidence of applause would not count, nor is one that is invited but has occurred “out of place” (too soon or too late). Furthermore, not all valid incidences are theoretically informative to the same degree. An isolated applause from just a handful of the audience, though valid and in the right place, has relatively little theoretical import for understanding the power of rhetoric compared to one that is made by many acting in unison as a group. When the latter occurs, it would be a clear indication of the power of rhetorically formulated speech. Such positive audience response constitutes the most direct and immediate means by which an audience can display its collective support for the speaker, something which they would not otherwise show to a speech of less power. To influence and orchestrate hundreds and thousands of people in the audience to precisely coordinate their response to applaud (and cheer) together as a group at the right time and place is no mean feat. Such a feat also influences the wider society through broadcast on television and other news and social media. The combined effect could be enormous there and then, and its downstream influence far-reaching, crossing country boarders and inspiring generations to come.

To accomplish the feat, an orator has to excite the audience to applaud, build up the excitement to a crescendo, and simultaneously cue the audience to synchronize their outburst of stored-up applause with the ongoing speech. Rhetorical formats that aid the orator to accomplish the dual functions include contrast, list, puzzle solution, headline-punchline, position-taking, and pursuit (Heritage & Greatbatch, 1986 ). To illustrate, we cite the contrast and list formats.

A contrast, or antithesis, is made up of binary schemata such as “too much” and “too little.” Heritage and Greatbatch ( 1986 , p. 123) reported the following example:

Governments will argue that resources are not available to help disabled people. The fact is that too much is spent on the munitions of war, and too little is spent on the munitions of peace [italics added]. As the audience is familiar with the binary schema of “too much” and “too little” they can habitually match the second half of the contrast against the first half. This decoding process reinforces message comprehension and helps them to correctly anticipate and applaud at the completion point of the contrast. In the example quoted above, the speaker micropaused for 0.2 seconds after the second word “spent,” at which point the audience began to applaud in anticipation of the completion point of the contrast, and applauded more excitedly upon hearing “. . . on the munitions of peace.” The applause continued and lasted for 9.2 long seconds.

A list is usually made up of a series of three parallel words, phrases or clauses. “Government of the people, by the people, for the people” is a fine example, as is Obama’s “It’s been a long time coming, but tonight, because of what we did on this day , in this election , at this defining moment , change has come to America!” (italics added) The three parts in the list echo one another, step up the argument and its corresponding excitement in the audience as they move from one part to the next. The third part projects a completion point to cue the audience to get themselves ready to display their support via applause, cheers, and so forth. In a real conversation this juncture is called a “transition-relevance place,” at which point a conversational partner (hearer) may take up a turn to speak. A skilful orator will micropause at that juncture to create a conversational space for the audience to take up their turn in applauding and cheering as a group.

As illustrated by the two examples above, speaker and audience collaborate to transform an otherwise monological speech into a quasiconversation, turning a passive audience into an active supportive “conversational” partner who, by their synchronized responses, reduces the psychological separation from the speaker and emboldens the latter’s self-confidence. Through such enjoyable and emotional participation collectively, an audience made up of formerly unconnected individuals with no strong common group identity may henceforth begin to feel “we are all one.” According to social identity theory and related theories (van Zomeren et al., 2008 ), the emergent group identity, politicized in the process, will in turn provide a social psychological base for collective social action. This process of identity making in the audience is further strengthened by the speaker’s frequent use of “we” as a first person, plural personal pronoun.

Conversational Power

A conversation is a speech exchange system in which the length and order of speaking turns have not been preassigned but require coordination on an utterance-by-utterance basis between two or more individuals. It differs from other speech exchange systems in which speaking turns have been preassigned and/or monitored by a third party, for example, job interviews and debate contests. Turn-taking, because of its centrality to conversations and the important theoretical issues that it raises for social coordination and implicit conversational conventions, has been the subject of extensive research and theorizing (Goodwin & Heritage, 1990 ; Grice, 1975 ; Sacks et al., 1974 ). Success at turn-taking is a key part of the conversational process leading to influence. A person who cannot do this is in no position to influence others in and through conversations, which are probably the most common and ubiquitous form of human social interaction. Below we discuss studies of conversational power based on conversational turns and applied to leader emergence in group and intergroup settings. These studies, as they unfold, link conversation analysis with social identity theory and expectation states theory (Berger et al., 1974 ).

A conversational turn in hand allows the speaker to influence others in two important ways. First, through current-speaker-selects-next the speaker can influence who will speak next and, indirectly, increases the probability that he or she will regain the turn after the next. A common method for selecting the next speaker is through tag questions. The current speaker (A) may direct a tag question such as “Ya know?” or “Don’t you agree?” to a particular hearer (B), which carries the illocutionary force of selecting the addressee to be the next speaker and, simultaneously, restraining others from self-selecting. The A 1 B 1 sequence of exchange has been found to have a high probability of extending into A 1 B 1 A 2 in the next round of exchange, followed by its continuation in the form of A 1 B 1 A 2 B 2 . For example, in a six-member group, the A 1 B 1 →A 1 B 1 A 2 sequence of exchange has more than 50% chance of extending to the A 1 B 1 A 2 B 2 sequence, which is well above chance level, considering that there are four other hearers who could intrude at either the A 2 or B 2 slot of turn (Stasser & Taylor, 1991 ). Thus speakership not only offers the current speaker the power to select the next speaker twice, but also to indirectly regain a turn.

Second, a turn in hand provides the speaker with an opportunity to exercise topic control. He or she can exercise non-decision-making power by changing an unfavorable or embarrassing topic to a safer one, thereby silencing or preventing it from reaching the “floor.” Conversely, he or she can exercise decision-making power by continuing or raising a topic that is favorable to self. Or the speaker can move on to talk about an innocuous topic to ease tension in the group.

Bales ( 1950 ) has studied leader emergence in groups made up of unacquainted individuals in situations where they have to bid or compete for speaking turns. Results show that individuals who talk the most have a much better chance of becoming leaders. Depending on the social orientations of their talk, they would be recognized as a task or relational leader. Subsequent research on leader emergence has shown that an even better behavioral predictor than volume of talk is the number of speaking turns. An obvious reason for this is that the volume of talk depends on the number of turns—it usually accumulates across turns, rather than being the result of a single extraordinary long turn of talk. Another reason is that more turns afford the speaker more opportunities to realize the powers of turns that have been explicated above. Group members who become leaders are the ones who can penetrate the complex, on-line conversational system to obtain a disproportionately large number of speaking turns by perfect timing at “transition-relevance places” to self-select as the next speaker or, paradoxical as it may seem, constructive interruptions (Ng et al., 1995 ).