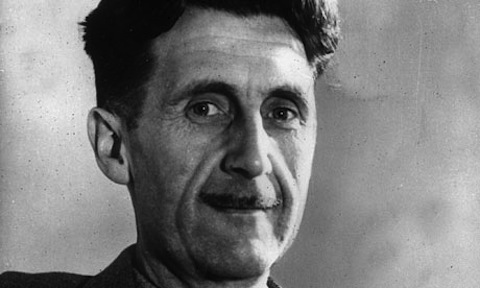

- About George Orwell

- Partners and Sponsors

- Accessibility

- Upcoming events

- The Orwell Festival

- The Orwell Memorial Lectures

- Books by Orwell

Essays and other works

- Encountering Orwell

- Orwell Live

- About the prizes

- Reporting Homelessness

- Enter the Prizes

- Previous winners

- Orwell Fellows

- Introduction

- Enter the Prize

- Terms and Conditions

- Volunteering

- About Feedback

- Responding to Feedback

- Start your journey

- Inspiration

- Find Your Form

- Start Writing

- Reading Recommendations

- Previous themes

- Our offer for teachers

- Lesson Plans

- Events and Workshops

- Orwell in the Classroom

- GCSE Practice Papers

- The Orwell Youth Fellows

- Paisley Workshops

The Orwell Foundation

- The Orwell Prizes

- The Orwell Youth Prize

- The Orwell Council

The Orwell Foundation is delighted to make available a selection of essays, articles, sketches, reviews and scripts written by Orwell.

This material remains under copyright in some jurisdictions, including the US, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Orwell Estate . All queries regarding rights should be addressed to the Estate’s representatives at A. M. Heath literary agency.

The Orwell Foundation is an independent charity – please consider making a donation to help us maintain these resources for readers everywhere.

Sketches For Burmese Days

- 1. John Flory – My Epitaph

- 2. Extract, Preliminary to Autobiography

- 3. Extract, the Autobiography of John Flory

- 4. An Incident in Rangoon

- 5. Extract, A Rebuke to the Author, John Flory

Essays and articles

- A Day in the Life of a Tramp ( Le Progrès Civique , 1929)

- A Hanging ( The Adelphi , 1931)

- A Nice Cup of Tea ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- Antisemitism in Britain ( Contemporary Jewish Record , 1945)

- Arthur Koestler (written 1944)

- British Cookery (unpublished, 1946)

- Can Socialists be Happy? (as John Freeman, Tribune , 1943)

- Common Lodging Houses ( New Statesman , 3 September 1932)

- Confessions of a Book Reviewer ( Tribune , 1946)

- “For what am I fighting?” ( New Statesman , 4 January 1941)

- Freedom and Happiness – Review of We by Yevgeny Zamyatin ( Tribune , 1946)

- Freedom of the Park ( Tribune , 1945)

- Future of a Ruined Germany ( The Observer , 1945)

- Good Bad Books ( Tribune , 1945)

- In Defence of English Cooking ( Evening Standard , 1945)

- In Front of Your Nose ( Tribune , 1946)

- Just Junk – But Who Could Resist It? ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- My Country Right or Left ( Folios of New Writing , 1940)

- Nonsense Poetry ( Tribune , 1945)

- Notes on Nationalism ( Polemic , October 1945)

- Pleasure Spots ( Tribune , January 1946)

- Poetry and the microphone ( The New Saxon Pamphlet , 1945)

- Politics and the English Language ( Horizon , 1946)

- Politics vs. Literature: An examination of Gulliver’s Travels ( Polemic , 1946)

- Reflections on Gandhi ( Partisan Review , 1949)

- Rudyard Kipling ( Horizon , 1942)

- Second Thoughts on James Burnham ( Polemic , 1946)

- Shooting an Elephant ( New Writing , 1936)

- Some Thoughts on the Common Toad ( Tribune , 1946)

- Spilling the Spanish Beans ( New English Weekly , 29 July and 2 September 1937)

- The Art of Donald McGill ( Horizon , 1941)

- The Moon Under Water ( Evening Standard , 1946)

- The Prevention of Literature ( Polemic , 1946)

- The Proletarian Writer (BBC Home Service and The Listener , 1940)

- The Spike ( Adelphi , 1931)

- The Sporting Spirit ( Tribune , 1945)

- Why I Write ( Gangrel , 1946)

- You and the Atom Bomb ( Tribune , 1945)

Reviews by Orwell

- Anonymous Review of Burmese Interlude by C. V. Warren ( The Listener , 1938)

- Anonymous Review of Trials in Burma by Maurice Collis ( The Listener , 1938)

- Review of The Pub and the People by Mass-Observation ( The Listener , 1943)

Letters and other material

- BBC Archive: George Orwell

- Free will (a one act drama, written 1920)

- George Orwell to Steven Runciman (August 1920)

- George Orwell to Victor Gollancz (9 May 1937)

- George Orwell to Frederic Warburg (22 October 1948, Letters of Note)

- ‘Three parties that mattered’: extract from Homage to Catalonia (1938)

- Voice – a magazine programme , episode 6 (BBC Indian Service, 1942)

- Your Questions Answered: Wigan Pier (BBC Overseas Service)

- The Freedom of the Press: proposed preface to Animal Farm (1945, first published 1972)

- Preface to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm (March 1947)

External links are being provided for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by The Orwell Foundation of any of the products, services or opinions of the corporation or organisation or individual. The Foundation bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.

We use cookies. By browsing our site you agree to our use of cookies. Accept

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

George Orwell’s Five Greatest Essays (as Selected by Pulitzer-Prize Winning Columnist Michael Hiltzik)

in English Language , Literature , Politics | November 12th, 2013 8 Comments

Every time I’ve taught George Orwell’s famous 1946 essay on misleading, smudgy writing, “ Politics and the English Language ,” to a group of undergraduates, we’ve delighted in pointing out the number of times Orwell violates his own rules—indulges some form of vague, “pretentious” diction, slips into unnecessary passive voice, etc. It’s a petty exercise, and Orwell himself provides an escape clause for his list of rules for writing clear English: “Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.” But it has made us all feel slightly better for having our writing crutches pushed out from under us.

Orwell’s essay, writes the L.A. Times ’ Pulitzer-Prize winning columnist Michael Hiltzik , “stands as the finest deconstruction of slovenly writing since Mark Twain’s “ Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses .” Where Twain’s essay takes on a pretentious academic establishment that unthinkingly elevates bad writing, “Orwell makes the connection between degraded language and political deceit (at both ends of the political spectrum).” With this concise description, Hiltzik begins his list of Orwell’s five greatest essays, each one a bulwark against some form of empty political language, and the often brutal effects of its “pure wind.”

One specific example of the latter comes next on Hiltzak’s list (actually a series he has published over the month) in Orwell’s 1949 essay on Gandhi. The piece clearly names the abuses of the imperial British occupiers of India, even as it struggles against the canonization of Gandhi the man, concluding equivocally that “his character was extraordinarily a mixed one, but there was almost nothing in it that you can put your finger on and call bad.” Orwell is less ambivalent in Hiltzak’s third choice , the spiky 1946 defense of English comic writer P.G. Wodehouse , whose behavior after his capture during the Second World War understandably baffled and incensed the British public. The last two essays on the list, “ You and the Atomic Bomb ” from 1945 and the early “ A Hanging ,” published in 1931, round out Orwell’s pre- and post-war writing as a polemicist and clear-sighted political writer of conviction. Find all five essays free online at the links below. And find some of Orwell’s greatest works in our collection of Free eBooks .

1. “ Politics and the English Language ”

2. “ Reflections on Gandhi ”

3. “ In Defense of P.G. Wodehouse ”

4. “ You and the Atomic Bomb ”

5. “ A Hanging ”

Related Content:

George Orwell’s 1984: Free eBook, Audio Book & Study Resources

The Only Known Footage of George Orwell (Circa 1921)

George Orwell and Douglas Adams Explain How to Make a Proper Cup of Tea

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (8) |

Related posts:

Comments (8), 8 comments so far.

You can’t go wrong with Orwell, so I feel bad about complaining. But how is “Shooting an Elephant” not on here?!?!

YES. Totally agree!

And “Down and Out in Paris and London” is one of the best comments on homelessness EVER!

Good article. In this selection of essays, he ranges from reflections on his boyhood schooling and the profession of writing to his views on the Spanish Civil War and British imperialism. The pieces collected here include the relatively unfamiliar and the more celebrated, making it an ideal compilation for both new and dedicated readers of Orwell’s work.nnhttp://essay-writing-company-reviews.essayboards.com/

Very thought provoking

i am crudbutt

i am crudbutt!

I think Orwell would have been irritated at your use of how instead of why.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Newsletter Sign-up

Free courses.

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

George Orwell; a collection of critical essays

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

109 Previews

7 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station22.cebu on January 12, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

A Summary and Analysis of George Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘Politics and the English Language’ (1946) is one of the best-known essays by George Orwell (1903-50). As its title suggests, Orwell identifies a link between the (degraded) English language of his time and the degraded political situation: Orwell sees modern discourse (especially political discourse) as being less a matter of words chosen for their clear meanings than a series of stock phrases slung together.

You can read ‘Politics and the English Language’ here before proceeding to our summary and analysis of Orwell’s essay below.

‘Politics and the English Language’: summary

Orwell begins by drawing attention to the strong link between the language writers use and the quality of political thought in the current age (i.e. the 1940s). He argues that if we use language that is slovenly and decadent, it makes it easier for us to fall into bad habits of thought, because language and thought are so closely linked.

Orwell then gives five examples of what he considers bad political writing. He draws attention to two faults which all five passages share: staleness of imagery and lack of precision . Either the writers of these passages had a clear meaning to convey but couldn’t express it clearly, or they didn’t care whether they communicated any particular meaning at all, and were simply saying things for the sake of it.

Orwell writes that this is a common problem in current political writing: ‘prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house.’

Next, Orwell elaborates on the key faults of modern English prose, namely:

Dying Metaphors : these are figures of speech which writers lazily reach for, even though such phrases are worn-out and can no longer convey a vivid image. Orwell cites a number of examples, including toe the line , no axe to grind , Achilles’ heel , and swansong . Orwell’s objection to such dying metaphors is that writers use them without even thinking about what the phrases actually mean, such as when people misuse toe the line by writing it as tow the line , or when they mix their metaphors, again, because they’re not interested in what those images evoke.

Operators or Verbal False Limbs : this is when a longer and rather vague phrase is used in place of a single-word (and more direct) verb, e.g. make contact with someone, which essentially means ‘contact’ someone. The passive voice is also common, and writing phrases like by examination of instead of the more direct by examining . Sentences are saved from fizzling out (because the thought or idea being conveyed is not particularly striking) by largely meaningless closing platitudes such as greatly to be desired or brought to a satisfactory conclusion .

Pretentious Diction : Orwell draws attention to several areas here. He states that words like objective , basis , and eliminate are used by writers to dress up simple statements, making subjective opinion sound like scientific fact. Adjectives like epic , historic , and inevitable are used about international politics, while writing that glorifies war is full of old-fashioned words like realm , throne , and sword .

Foreign words and phrases like deus ex machina and mutatis mutandis are used to convey an air of culture and elegance. Indeed, many modern English writers are guilty of using Latin or Greek words in the belief that they are ‘grander’ than home-grown Anglo-Saxon ones: Orwell mentions Latinate words like expedite and ameliorate here. All of these examples are further proof of the ‘slovenliness and vagueness’ which Orwell detects in modern political prose.

Meaningless Words : Orwell argues that much art criticism and literary criticism in particular is full of words which don’t really mean anything at all, e.g. human , living , or romantic . ‘Fascism’, too, has lost all meaning in current political writing, effectively meaning ‘something not desirable’ (one wonders what Orwell would make of the word’s misuse in our current time!).

To prove his point, Orwell ‘translates’ a well-known passage from the Biblical Book of Ecclesiastes into modern English, with all its vagueness of language. ‘The whole tendency of modern prose’, he argues, ‘is away from concreteness.’ He draws attention to the concrete and everyday images (e.g. references to bread and riches) in the Bible passage, and the lack of any such images in his own fabricated rewriting of this passage.

The problem, Orwell says, is that it is too easy (and too tempting) to reach for these off-the-peg phrases than to be more direct or more original and precise in one’s speech or writing.

Orwell advises every writer to ask themselves four questions (at least): 1) what am I trying to say? 2) what words will express it? 3) what image or idiom will make it clearer? and 4) is this image fresh enough to have an effect? He proposes two further optional questions: could I put it more shortly? and have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

Orthodoxy, Orwell goes on to observe, tends to encourage this ‘lifeless, imitative style’, whereas rebels who are not parroting the ‘party line’ will normally write in a more clear and direct style.

But Orwell also argues that such obfuscating language serves a purpose: much political writing is an attempt to defend the indefensible, such as the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan (just one year before Orwell wrote ‘Politics and the English Language’), in such a euphemistic way that the ordinary reader will find it more palatable.

When your aim is to make such atrocities excusable, language which doesn’t evoke any clear mental image (e.g. of burning bodies in Hiroshima) is actually desirable.

Orwell argues that just as thought corrupts language, language can corrupt thought, with these ready-made phrases preventing writers from expressing anything meaningful or original. He believes that we should get rid of any word which has outworn its usefulness and should aim to use ‘the fewest and shortest words that will cover one’s meaning’.

Writers should let the meaning choose the word, rather than vice versa. We should think carefully about what we want to say until we have the right mental pictures to convey that thought in the clearest language.

Orwell concludes ‘Politics and the English Language’ with six rules for the writer to follow:

i) Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

‘Politics and the English Language’: analysis

In some respects, ‘Politics and the English Language’ advances an argument about good prose language which is close to what the modernist poet and thinker T. E. Hulme (1883-1917) argued for poetry in his ‘ A Lecture on Modern Poetry ’ and ‘Notes on Language and Style’ almost forty years earlier.

Although Hulme and Orwell came from opposite ends of the political spectrum, their objections to lazy and worn-out language stem are in many ways the same.

Hulme argued that poetry should be a forge where fresh metaphors are made: images which make us see the world in a slightly new way. But poetic language decays into common prose language before dying a lingering death in journalists’ English. The first time a poet described a hill as being ‘clad [i.e. clothed] with trees’, the reader would probably have mentally pictured such an image, but in time it loses its power to make us see anything.

Hulme calls these worn-out expressions ‘counters’, because they are like discs being moved around on a chessboard: an image which is itself not unlike Orwell’s prefabricated hen-house in ‘Politics and the English Language’.

Of course, Orwell’s focus is English prose rather than poetry, and his objections to sloppy writing are not principally literary (although that is undoubtedly a factor) but, above all, political. And he is keen to emphasise that his criticism of bad language, and suggestions for how to improve political writing, are both, to an extent, hopelessly idealistic: as he observes towards the end of ‘Politics and the English Language’, ‘Look back through this essay, and for certain you will find that I have again and again committed the very faults I am protesting against.’

But what Orwell advises is that the writer be on their guard against such phrases, the better to avoid them where possible. This is why he encourages writers to be more self-questioning (‘What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?’) when writing political prose.

Nevertheless, the link between the standard of language and the kind of politics a particular country, regime, or historical era has is an important one. As Orwell writes: ‘I should expect to find – this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify – that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.’

Those writing under a dictatorship cannot write or speak freely, of course, but more importantly, those defending totalitarian rule must bend and abuse language in order to make ugly truths sound more attractive to the general populace, and perhaps to other nations.

In more recent times, the phrase ‘collateral damage’ is one of the more objectionable phrases used about war, hiding the often ugly reality (innocent civilians who are unfortunate victims of violence, but who are somehow viewed as a justifiable price to pay for the greater good).

Although Orwell’s essay has been criticised for being too idealistic, in many ways ‘Politics and the English Language’ remains as relevant now as it was in 1946 when it was first published.

Indeed, to return to Orwell’s opening point about decadence, it is unavoidable that the standard of political discourse has further declined since Orwell’s day. Perhaps it’s time a few more influential writers started heeding his argument?

9 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of George Orwell’s ‘Politics and the English Language’”

- Pingback: 10 of the Best Works by George Orwell – Interesting Literature

- Pingback: The Best George Orwell Essays Everyone Should Read – Interesting Literature

YES! Thank you!

A great and useful post. As a writer, I have been seriously offended by the politicization of the language in the past 50 years. Much of this is supposedly to sanitize, de-genderize, or diversity-fie language – exactly as it’s done in Orwell’s “1984.” How did a wonderfully useful word like gay – cheerful or lively – come to mean homosexual? And is optics not a branch of physics? Ironically, when the liberal but sensible JK Rowling criticized the replacement of “woman” with “person who menstruates” SHE was the one attacked. Now, God help us, we hope “crude” spaceships will get humans to Mars – which, if you research the poor quality control in Tesla cars, might in fact be a proper term.

And less anyone out there misread, this or me – I was a civil rights marcher, taught in a girls’ high school (where I got in minor trouble for suggesting to the students that they should aim higher than the traditional jobs of nurse or teacher), and – while somewhat of a mugwump – consider myself a liberal.

But I will fight to keep the language and the history from being 1984ed.

My desert island book would be the Everyman Essays of Orwell which is around 1200 pages. I’ve read it all the way through twice without fatigue and read individual essays endlessly. His warmth and affability help, Even better than Montaigne in this heretic’s view.

- Pingback: Q Marks the Spot 149 (March 2021 Treasure Map) – Quaerentia

I’ll go against the flow here and say Orwell was – at least in part – quite wrong here. If I recall correctly, he was wrong about a few things including, I think, the right way to make a cup of tea! In all seriousness, what he fails to acknowledge in this essay is that language is a living thing and belongs to the people, not the theorists, at all time. If a metaphor changes because of homophone mix up or whatever, then so be it. Many of our expressions we have little idea of now – I think of ‘baited breath’ which almost no one, even those who know how it should be spelt, realise should be ‘abated breath’.

Worse than this though, his ‘rules’ have indeed been taken up by many would-be writers to horrifying effect. I recall learning to make up new metaphors and similes rather than use clichés when I first began training ten years ago or more. I saw some ghastly new metaphors over time which swiftly made me realise that there’s a reason we use the same expressions a great deal and that is they are familiar and do the job well. To look at how to use them badly, just try reading Gregory David Roberts ‘Shantaram’. Similarly, the use of active voice has led to unpalatable writing which lacks character. The passive voice may well become longwinded when badly used, but it brings character when used well.

That said, Orwell is rarely completely wrong. Some of his points – essentially, use words you actually understand and don’t be pretentious – are valid. But the idea of the degradation of politics is really quite a bit of nonsense!

Always good to get some critique of Orwell, Ken! And I do wonder how tongue-in-cheek he was when proposing his guidelines – after all, even he admits he’s probably broken several of his own rules in the course of his essay! I think I’m more in the T. E. Hulme camp than the Orwell – poetry can afford to bend language in new ways (indeed, it often should do just this), and create daring new metaphors and ways of viewing the world. But prose, especially political non-fiction, is there to communicate an argument or position, and I agree that ghastly new metaphors would just get in the way. One of the things that is refreshing reading Orwell is how many of the problems he identified are still being discussed today, often as if they are new problems that didn’t exist a few decades ago. Orwell shows that at least one person was already discussing them over half a century ago!

Absolutely true! When you have someone of Orwell’s intelligence and clear thinking, even when you believe him wrong or misguided, he is still relevant and remains so decades later.

Comments are closed.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

George Orwell

Select a format:

About the author, more in this series.

Sign up to the Penguin Newsletter

By signing up, I confirm that I'm over 16. To find out what personal data we collect and how we use it, please visit our Privacy Policy

George Orwell: Essays Background

By george orwell.

These notes were contributed by members of the GradeSaver community. We are thankful for their contributions and encourage you to make your own.

Written by Polly Barbour

"Everything line of serious work I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democraticsocialism, as I understand it."

So spoke George Orwell , in one of his better known essays, Why I Write (1946) which describes his own particular road towards becoming a writer - one of the twentieth century’s most prolific, as it turned out. Although his novels Animal Farm and 1984 account for over half of his book sales worldwide, he nonetheless penned over four hundred essays, as well as articles, political editorials, and of course, fictional novellas and poems.

Orwell began his writing career by contributing to magazines, including fifteen London Letters for the Partisan Review, an American quarterly journal, during March and April 1941.

During Orwell's lifetime, two anthologies of his work were compiled, including a book of his essays. This changed after his death, when over a dozen anthologies appeared, including a very ambitious attempt to collate all of his essays and letters together in one weighty tome, and a twenty-volume collection of his entire body of work published in the late 1980s.

The best-known collection of his essays is called Inside The Whale, the most familiar of the essays also giving the collection its title. A second book of essays, Dickens Dali and Others was published in America in 1958. The majority of Orwell's essays were overtly political, without innuendo or metaphor, but explaining why he believed strongly in socialism, and was opposed vehemently to totalitarianism. His best known essays include Shooting An Elephant, England Your England, Such, Such Were The Joys, and Inside The Whale.

Like much of Orwell's work, his essays form the core curriculum in the English education system which has led many to voice concern over the politicizing of children's education and the obvious bias in ideological teaching. However, many cite undeniably Conservative aspects of his ideology as well; his biographer, Christopher Hitchens, states that Orwell was inconsistent, but was never afraid to stop learning, and testing, his own intelligence.

Update this section!

You can help us out by revising, improving and updating this section.

After you claim a section you’ll have 24 hours to send in a draft. An editor will review the submission and either publish your submission or provide feedback.

George Orwell: Essays Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for George Orwell: Essays is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Shooting an Elephant

In the opening of the essay, Orwell states that he is opposed to the British empire and on the side of the Burman, but he also claims that at the time of the events of the story, he was too young to know how to confront his own dilemma. Over the...

Orwell maintains that people with brown skins are usually invisible to white Europeans.

I'm not sure the particular essay you are referring to but Orwell has stated that people with brown skins are next door to invisible.

Orwell maintains that because there are so many people buried in the small space allocated to graveyards, a visitor can easily find himself walking on bodies buried in the earth.

Which particular essay are you referring to?

Study Guide for George Orwell: Essays

George Orwell: Essays study guide contains a biography of George Orwell, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis of select short stories including Shooting an Elephant.

- About George Orwell: Essays

- George Orwell: Essays Summary

- Character List

Essays for George Orwell: Essays

George Orwell: Essays essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of select essays by George Orwell.

- Fighting Imperialism: Orwell's Essays as a Lens for Understanding His Novels

- A Hanging Prose Analysis

- Critiquing English Literature

- Decay of Moral Judgement in "A Hanging" by George Orwell

- Orwell’s Assessment of Yeats as an Occult Fascist

Wikipedia Entries for George Orwell: Essays

- Introduction

- Film adaptation

George Orwell Books: A Must-Read Collection for Fans of Dystopian Fiction

Posted on Published: November 13, 2023 - Last updated: November 22, 2023

Categories Fiction , Reading Lists

George Orwell was an influential British writer known for his works of fiction and non-fiction. He is best known for his novels “Animal Farm” and “1984,” which are still widely read and studied today. However, Orwell wrote many other books throughout his career that are worth exploring for those interested in his life and work.

One of the best ways to gain a deeper understanding of Orwell is to read books about him. There are many biographies and critical studies available that offer insights into his life, his writing process, and his political beliefs. Some of these books focus on specific works, while others offer a more comprehensive look at his entire body of work. Reading these books can help readers gain a deeper appreciation for Orwell’s impact on literature and politics.

In this article, we will explore some of the best books about George Orwell. Whether you are a longtime fan of his work or are just discovering him for the first time, these books offer valuable insights into one of the most important writers of the 20th century. From biographies to critical studies to collections of essays, there is something for everyone in this list.

The Life of George Orwell

George Orwell, whose real name was Eric Arthur Blair, was born in Motihari, India in 1903. He was educated at Eton and won scholarships to study at Wellington and the Indian Civil Service. However, he decided not to join the Indian Civil Service and instead chose to become a writer.

Orwell’s personal life was marked by tragedy. He married Eileen O’Shaughnessy in 1936, but she died during an operation in 1945. Orwell himself died of tuberculosis in 1950, at the age of 46.

Despite his relatively short life, Orwell left behind a legacy of important literary works. His most famous novels, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, have become classics of modern literature.

Orwell’s life has been the subject of numerous biographies, including Orwell: The Life by D.J. Taylor. This biography provides a detailed account of Orwell’s life, including his experiences in the Spanish Civil War and his time working as a journalist.

Overall, George Orwell’s life was marked by both triumphs and tragedies, but his contributions to literature continue to be celebrated today.

George Orwell: The Writer and Journalist

George Orwell, whose real name was Eric Blair, was a British writer, novelist, essayist, and literary critic. He is widely recognized as one of the most important writers of the 20th century. Orwell is known for his works that explore the themes of social injustice, totalitarianism, and the dangers of political oppression.

As a writer, Orwell was known for his clear and concise prose, which he used to convey his political and social ideas. He wrote several influential books, including “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” which are still widely read and studied today.

In addition to his work as a novelist, Orwell was also a prolific journalist. He wrote book reviews, essays, and articles for a variety of publications, including “The Observer” and “Tribune.” His journalism covered a wide range of topics, from politics and social issues to literature and culture.

Orwell’s journalism was characterized by his commitment to truth and his willingness to challenge the status quo. He was an outspoken critic of totalitarianism and imperialism, and his writing often reflected his socialist and anti-fascist beliefs.

Overall, George Orwell was a writer and journalist who used his work to explore important social and political issues. His clear and concise prose, commitment to truth, and willingness to challenge the status quo continue to make him a significant figure in the world of literature and journalism.

Orwell’s Early Works

George Orwell wrote several works during his early years as a writer, both fiction and non-fiction. One of his first published books was “Burmese Days,” a novel set in colonial Burma that explores themes of imperialism and racism.

Another notable early work of Orwell’s is “Down and Out in Paris and London,” a non-fiction book that details his experiences living in poverty in those cities. This work is considered a classic of social commentary and is often studied for its insights into poverty and homelessness.

Orwell also wrote “A Clergyman’s Daughter,” a novel about a young woman who loses her memory and must navigate the challenges of life without knowing her past. This work is notable for its exploration of themes of identity and loss.

“Keep the Aspidistra Flying” is another early novel by Orwell, which tells the story of a struggling writer who is determined to reject the commercialism of society and live a life of poverty and simplicity. This work is often studied for its critique of capitalism and consumer culture.

Finally, “Coming Up for Air” is a novel that explores the themes of memory and nostalgia, as well as the impact of industrialization on rural communities. This work is often considered one of Orwell’s most personal novels, as it draws heavily on his own experiences growing up in rural England.

Overall, Orwell’s early works demonstrate his skill as both a fiction and non-fiction writer, and offer valuable insights into the social and political issues of his time.

Masterpieces: Animal Farm and 1984

George Orwell’s novels Animal Farm and 1984 are considered two of the most influential works of the 20th century. Both novels are dystopian in nature and explore the dangers of totalitarianism and government overreach.

Animal Farm, published in 1945, is a political allegory that tells the story of a group of farm animals who overthrow their human owner and establish a society based on equality and cooperation. However, as time passes, the pigs who lead the revolution become corrupt and oppressive, and the society they create becomes more and more like the one they overthrew.

1984, published in 1949, is a novel set in a future dystopian society where the government, led by the mysterious figure of Big Brother, has complete control over every aspect of citizens’ lives. The protagonist, Winston Smith, works for the government but becomes disillusioned with the oppressive regime and begins to rebel against it. The novel explores themes of surveillance, propaganda, and the manipulation of language through the creation of Newspeak.

Both novels have become synonymous with the term “Orwellian,” which refers to a society that is oppressive and controlling. The term is often used to describe situations where government overreach and surveillance threaten individual freedoms.

In Animal Farm, Orwell uses the allegory of the farm animals to criticize the Soviet Union and the rise of Stalinism. In 1984, he warns of the dangers of totalitarianism and the importance of individual freedom and autonomy.

Overall, Animal Farm and 1984 are masterpieces of literature that continue to be relevant today, reminding readers of the importance of vigilance in the face of government overreach and the need to protect individual freedoms.

Orwell’s Essays and Criticisms

George Orwell is widely recognized as one of the most influential essayists and literary critics of the 20th century. His essays and criticisms cover a wide range of topics, including politics, literature, and social issues.

One of Orwell’s most famous essays is “Politics and the English Language,” in which he critiques the use of vague and meaningless language in political discourse. He argues that such language not only obscures the truth but also contributes to the degradation of language itself.

In “Books v. Cigarettes,” Orwell explores the idea that books are a better value than cigarettes, both in terms of cost and the value they provide. He argues that books offer a more lasting and enriching experience than cigarettes, which are quickly consumed and offer little benefit beyond a temporary fix.

Another notable essay is “Notes on Nationalism,” in which Orwell examines the concept of nationalism and its impact on society. He argues that nationalism can be a dangerous force, leading to conflict and division, and that it is important to recognize and resist its negative effects.

Orwell’s collection of essays, “Inside the Whale and Other Essays,” includes a variety of pieces on topics ranging from literature to politics. The title essay, “Inside the Whale,” is a critique of the literary establishment and its tendency to dismiss works that do not conform to established norms.

“All Art is Propaganda: Critical Essays” is another collection of Orwell’s essays, this time focusing on the role of art and literature in society. Orwell argues that all art is inherently political and that artists have a responsibility to use their work to promote positive social change.

In “Decline of the English Murder,” Orwell examines the phenomenon of murder in English society and its portrayal in literature. He argues that the murder mystery genre has lost its power to shock and that the public has become desensitized to violence.

Finally, in “Fascism and Democracy,” Orwell explores the rise of fascism in Europe and its threat to democracy. He argues that fascism is a fundamentally anti-democratic ideology that seeks to destroy individual freedom and replace it with a totalitarian state.

Overall, Orwell’s essays and criticisms offer a unique perspective on a wide range of issues and continue to be relevant today.

Orwell’s Views and Beliefs

George Orwell was a writer who was known for his strong political views and beliefs. He was a democratic socialist who believed in the power of the working class. He was also an anarchist sympathizer who believed in the abolition of the state. Orwell was a firm believer in truth and honesty, and he believed that these values were essential for a functioning democracy.

Orwell was deeply affected by his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, where he fought on the side of the anti-fascist forces. This experience led him to become a committed anti-fascist and anti-imperialist. He believed that imperialism was a form of oppression and that it was the duty of the working class to fight against it.

Orwell’s views on socialism were complex. He was critical of the Soviet Union and its brand of communism, which he believed was authoritarian and oppressive. However, he was also critical of the capitalist system, which he believed was exploitative and unjust. Orwell believed in a form of democratic socialism that would give power to the working class and promote equality and justice.

In his essay “The Lion and the Unicorn,” Orwell outlined his vision for a democratic socialist Britain. He believed that the country needed to break free from its imperialist past and embrace a new, more egalitarian future. He argued that the working class needed to take control of the means of production and that the state needed to be reformed to better serve the needs of the people.

Orwell was also a strong believer in the power of literature to effect change. He was influenced by the works of Charles Dickens, who he believed had a keen understanding of poverty and social injustice. Orwell believed that literature could be used to expose the truth and to promote social change.

Overall, Orwell’s views and beliefs were shaped by his experiences of war, poverty, and oppression. He was a committed anti-fascist and anti-imperialist who believed in the power of the working class. He was critical of both capitalism and communism and believed in a form of democratic socialism that would promote equality and justice.

Orwell’s Experiences in Spain

George Orwell’s personal account of his experiences during the Spanish Civil War is widely considered to be one of his most significant works. In “Homage to Catalonia,” Orwell provides a vivid and honest portrayal of his time in Spain, where he fought for the socialist POUM militia in Barcelona and Aragon.

Orwell arrived in Spain in December 1936 and was immediately struck by the revolutionary atmosphere in Barcelona. He was impressed by the working-class people who had taken control of the city and was drawn to the socialist ideals that were being espoused. Orwell joined the POUM militia and was sent to the front line in Aragon.

Orwell’s time in Spain was marked by both bravery and tragedy. He was wounded in action and witnessed the horrors of war firsthand. He also saw the betrayal of the socialist cause by the Soviet Union, which led to the suppression of the POUM and other left-wing groups.

Through his experiences in Spain, Orwell developed a deep understanding of the complexities of politics and the dangers of totalitarianism. His writing on the Spanish Civil War remains a powerful reminder of the importance of freedom and democracy.

Overall, Orwell’s time in Spain had a profound impact on his life and work. His experiences in the Spanish Civil War informed much of his later writing, including his famous novel “1984.”

Influence and Legacy of George Orwell

George Orwell’s works have had a profound impact on literature and political thought. His novels, essays, and other writings have inspired generations of readers and writers alike. Orwell’s most famous works, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four , have become cultural touchstones and are often used as shorthand for totalitarianism and dystopia.

Orwell’s writing style is known for its clarity, directness, and honesty. He was a master of the English language and had a talent for making complex ideas accessible to a wide audience. His books are still widely read today and continue to influence political discourse around the world.

Orwell’s ideas about politics, society, and the human condition are still relevant today. His warnings about the dangers of totalitarianism and the importance of individual freedom are as important now as they were when he first wrote them. Orwell’s work has been studied by scholars and political activists alike, and his ideas have been used to inspire political movements around the world.

Orwell’s legacy extends beyond his writing. He was an active participant in the political and social issues of his time, and his experiences shaped his worldview and his writing. He was a committed socialist and fought for social justice throughout his life. Orwell’s work is often seen as a critique of both the left and the right, and his ideas have been used to challenge conventional political wisdom.

In conclusion, George Orwell’s influence and legacy are undeniable. His books continue to be read and studied, and his ideas continue to inspire political movements and social change. Orwell’s writing style, clarity of thought, and commitment to social justice have made him one of the most important writers of the 20th century.

George Orwell’s Pen Name

George Orwell’s real name was Eric Arthur Blair. However, he is better known by his pen name, George Orwell. A pen name, also known as a pseudonym, is a fictitious name used by an author instead of their real name.

The use of a pen name allowed Orwell to separate his personal life from his writing career. It also gave him the freedom to express his views without fear of repercussion.

Orwell chose the name George Orwell as a tribute to the River Orwell in Suffolk, England. He also wanted a name that sounded “English” and “solid”. The name George is a common English name, while Orwell sounds similar to the name of a small river.

Orwell first used the name George Orwell in 1933, when he published his first book, “Down and Out in Paris and London”. He continued to use the name for all his subsequent works, including his most famous novels, “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four”.

In conclusion, George Orwell’s pen name was an important part of his identity as a writer. It allowed him to express his views freely and separate his personal life from his writing career.

Bibliography of George Orwell

George Orwell was a prolific writer who wrote many works of fiction and non-fiction. Some of his most well-known works include Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four , which are both dystopian novels that have become classics of English literature. However, Orwell’s bibliography also includes many other works that are worth exploring.

One of Orwell’s early works is The Road to Wigan Pier , which is a non-fiction book that explores the living conditions of working-class people in England during the Great Depression. Another non-fiction work is Shooting an Elephant , which is an essay that explores the morality of imperialism and the psychological effects of power.

Orwell also wrote several essays about his experiences in school, including Such, Such Were the Joys . This essay explores the harsh conditions of English boarding schools in the early 20th century, and it is often seen as a precursor to Orwell’s later works about totalitarianism.

In addition to his non-fiction works, Orwell also wrote several short stories , including A Hanging . This story explores the themes of power and death, and it is often seen as a commentary on capital punishment.

Orwell’s political views are also explored in his works, including The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius . This non-fiction work explores Orwell’s belief in democratic socialism and his vision for a better society.

Finally, it is worth noting that Orwell also wrote several poems throughout his career. While his poetry is not as well-known as his prose, it is still worth exploring for those who are interested in his work.

Overall, George Orwell’s bibliography is vast and varied, and it offers a fascinating insight into the mind of one of the 20th century’s most important writers.

Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

What Orwell Really Feared

In 1946, the author repaired to the remote Isle of Jura and wrote his masterpiece, 1984 . What was he looking for?

The Isle of Jura is a patchwork of bogs and moorland laid across a quartzite slab in Scotland’s Inner Hebrides. Nearly 400 miles from London, rain-lashed, more deer than people: All the reasons not to move there were the reasons George Orwell moved there. Directions to houseguests ran several paragraphs and could include a plane, trains, taxis, a ferry, another ferry, then miles and miles on foot down a decrepit, often impassable rural lane. It’s safe to say the man wanted to get away. From what?

Explore the May 2024 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Orwell himself could be sentimental about his longing to escape (“Thinking always of my island in the Hebrides,” he’d once written in his wartime diary) or wonderfully blunt. In the aftermath of Hiroshima, he wrote to a friend:

This stupid war is coming off in abt 10–20 years, & this country will be blown off the map whatever else happens. The only hope is to have a home with a few animals in some place not worth a bomb.

It helps also to remember Orwell’s immediate state of mind when he finally fully moved to Jura, in May 1946. Four months before Hiroshima, his wife, Eileen, had died; shortly after the atomic bomb was dropped, Animal Farm was published.

From the March 1947 issue: George Orwell’s ‘The Prevention of Literature’

Almost at once, in other words, Orwell became a widower, terrified by the coming postwar reality, and famous—the latter a condition he seems to have regarded as nothing but a bother. His newfound sense of dread was only adding to one he’d felt since 1943, when news of the Tehran Conference broke. The meeting had been ominous to Orwell: It placed in his head the idea of Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin divvying up the postwar world, leading to a global triopoly of super-states. The man can be forgiven for pouring every ounce of his grief, self-pity, paranoia (literary lore had it that he thought Stalin might have an ice pick with his name on it), and embittered egoism into the predicament of his latest protagonist, Winston Smith.

Unsurprisingly, given that it culminated in both his masterpiece and his death, Orwell’s time on the island has been picked over by biographers, but Orwell’s Island: George, Jura and 1984 , by Les Wilson, treats it as a subject worthy of stand-alone attention. The book is at odds with our sense of Orwell as an intrepid journalist. It is a portrait of a man jealously guarding his sense of himself as a creature elementally apart, even as he depicts the horrors of a world in which the human capacity for apartness is being hunted down and destroyed.

Wilson is a former political journalist, not a critic, who lives on neighboring Islay, famous for its whiskeys. He is at pains to show how Orwell, on Jura, overcame one of his laziest prejudices: The author went from taking every opportunity to laugh at the Scots for their “burns, braes, kilts, sporrans, claymores, bagpipes” (who is better at the derisive list than Orwell?) to complaining about the relative lack of Gaelic-language radio programming.

Scottish had come to mean something more to him than kailyard kitsch. These were a people holding out against a fully amalgamated identity, beginning with the Kingdom of Great Britain and extending to modernity itself. On Jura at least, crofters and fishermen still lived at a village scale. As to whether Jura represented, as has been suggested, suicide by other means—Orwell was chronically ill, and Barnhill, his cottage, was 25 miles from the island’s one doctor—Wilson brushes this aside. In fact, he argues that Jura was “kinder to Orwell’s ravaged lungs than smog-smothered London,” where inhabitants were burning scavenged wood to stay warm.

At Barnhill, Orwell set up almost a society in miniature, devoting his 16-acre homestead to his ideal of self-sufficiency. Soon after moving there, he was joined by his sister, his 2-year-old adopted son, and a nanny. Amid the general, often biting, austerity of postwar Europe, they enjoyed a private cornucopia, subsisting on, as Wilson says, a diet of “fish, lobster, rabbit, venison and fresh milk and eggs,” and were often warmed by peat that Orwell himself had cut. He intended to live there for the rest of his life, raising his son and relishing an existence as a non-cog in a noncapitalist machine.

From the July 2019 issue: Doublethink is stronger than Orwell imagined

He lived without electricity or phone; shot rabbits “for the pot,” as Wilson says; raised geese to be slaughtered and plucked; and fished the surrounding waters in a dinghy. He fashioned a tobacco pouch from animal skin and a mustard spoon out of deer bone, and served his aghast guests a seaweed blancmange. Over time, absconding to Jura and writing 1984 became aspects of a single premonition: a coming world of perpetual engulfment by the forces of bigness. As Orwell’s latest biographer, D. J. Taylor, has pointed out in Orwell: The New Life , Orwell’s novels before Animal Farm followed a common template of a sensitive young person going up against a heartless society, destined to lose. Eileen is the one who helped him—either by suggesting that Animal Farm be told as a fable or by lightening his touch, depending on whom you talk to—find a newly engaging, even playful (in its way), register.

The loss of Eileen and return of the self-pitying Orwell alter ego are certainly linked. And indeed, in 1984 he produces his most Orwellian novel, in both senses—only now both protagonist and situation are presented in the absolute extreme : The young man is the bearer (if we believe his tormentor, O’Brien) of the last shred of human autonomy, in a society both totally corrupt and laying total claim to his being.

What this absolutism produced, of course, was not another fusty neo-Edwardian novel à la Orwell’s earlier Keep the Aspidistra Flying , but a wild, aggrieved tour de force of dystopian erotica. Odd though it may sound, given the novel’s unremitting torments, 1984 quickly became a best seller, in no small part because its first readers, especially in America, found it comforting—a source of the release you might feel, in a darkened theater, when you remember that you yourself are not being chased by a man with a chain saw. The reader could glance up, notice no limitless police powers or kangaroo inquisitions, and say: We are not them .

Such complacency is hard to come by in 2024. Thinking of Orwell, famous though he is for his windowpane prose and the prescience of his essays, as the ultimate sane human being is not so easy either. Rereading 1984 in light of the Jura episode suggests that Orwell was an altogether weirder person, and his last novel an altogether weirder book, than we’ve appreciated.

Conventionally speaking, 1984 is not a good novel; it couldn’t be. Novels are about the conflict between an individual’s inner-generated aims and a prevailing social reality that denies or thwarts them. 1984 is the depiction of the collapse of this paradigm—the collapse of inner and outer in all possible iterations. Of course its protagonist is thinly drawn: Winston’s self lacks a social landscape to give it dimensionality.

In place of anything like a novel proper, we get a would-be bildungsroman breaking through to the surface in disparate fragments. These scraps are Winston’s yearnings, memories, sensual instincts, which have, as yet, somehow gone unmurdered by the regime. The entire state-sponsored enterprise of Pavlovian sadism in Oceania is devoted to snuffing out this remnant interiority.

The facsimile of a life that Winston does enact comes courtesy of a series of private spaces—a derelict church, a clearing in the woods, a room above a junk shop—the last of which is revealed to have been a regime-staged contrivance. The inexorable momentum of the novel is toward the final such private space, Winston’s last line of defense, and the last line of defense in any totalitarian society: the hidden compartment of his mind.

When all else fails, there is the inaccessibility of human mentality to others, a black box in every respect. Uncoincidentally, Winston’s final defense—hiding out in his head—had been Orwell’s first. While he struggled on Jura to finish 1984 , Orwell apparently returned to “Such, Such Were the Joys,” his long and excoriating essay about his miserable years at St. Cyprian’s boarding school. He’d been sent there at the age of 8, one of the shabby-genteel boys with brains in what was otherwise a class snob’s paradise. He was a bed wetter to boot, for which, Orwell writes, he was brutally punished. No wonder he found dignity in apartness. Taylor’s biography is brilliant about the connection between Orwell’s childhood reminiscence and 1984 .

In the essay, Orwell portrays his alma mater as an environment that invaded every cranny of its pupils’ lives. Against this, he formed his sense of bearing “at the middle of one’s heart,” as he writes, “an incorruptible inner self” holding out against an autocratic headmistress. As a cop in Burma, a scullion in Paris, an amateur ethnographer in northern England, he was a man who kept his own company, even when in company, and whom others, as a consequence, found by and large inscrutable.

What was this man’s genius, if not taking the petty anxieties of Eric Blair, his given name, and converting them into the moral clarity of George Orwell? Fearful that his own cherished apartness was being co-opted into nonexistence, he projected his fear for himself onto something he called the “autonomous individual,” who, as he said in his 1940 essay “Inside the Whale,” “is going to be stamped out of existence.” To this he added:

The literature of liberalism is coming to an end and the literature of totalitarianism has not yet appeared and is barely imaginable. As for the writer, he is sitting on a melting iceberg; he is merely an anachronism, a hangover from the bourgeois age, as surely doomed as the hippopotamus.

The fate of the autonomous individual, “the writer,” the literature of liberalism—he carried all of it to Jura, where he dumped it onto the head of poor Winston Smith.

Orwell typed for hours upstairs, sitting on his iron bedstead in a tatty dressing gown, chain-smoking shag tobacco. In May 1947, he felt he had a third of a draft, and in November, a completed one. In December, he was in a hospital outside Glasgow, diagnosed with “chronic” tuberculosis—not a death sentence, maybe, but his landlord on Jura suspected that Orwell now knew he was dying.

The following July, after grueling treatments and a stint in a sanatorium, he returned to Jura fitter but by no means cured, and under strict orders to take it easy. His rough draft, however, was a riot of scrawled-over pages. To produce a clean manuscript for the publisher, he would need to hire and closely supervise a typist, but no candidate was willing to trek to Jura, and Orwell was unwilling to leave it. He typed 1984 on his own, having all but spent himself writing it.

“He should have been in bed,” Wilson says, and instead sat “propped up on a sofa” banging out 5,000 words a day. Among all of its gruesome set pieces, culminating in Room 101 in the Ministry of Love, the novel’s most decisive act of torment is a simple glance in the mirror. Winston is sure—it is one of his last consolations, before breaking completely—that some inherent principle exists in the universe to prevent a system based on nothing but cruelty and self-perpetuation from triumphing forever. O’Brien calmly assures Winston that he’s wrong, that he is “the last man,” and to prove it, and the obvious nonexistence of “the human spirit,” he forces Winston to look at himself:

A bowed, greycoloured, skeleton-like thing was coming towards him. Its actual appearance was frightening, and not merely the fact that he knew it to be himself. He moved closer to the glass. The creature’s face seemed to be protruded, because of its bent carriage. A forlorn, jailbird’s face with a nobby forehead running back into a bald scalp, a crooked nose, and battered-looking cheekbones above which his eyes were fierce and watchful. The cheeks were seamed, the mouth had a drawn-in look. Certainly it was his own face, but it seemed to him that it had changed more than he had changed inside. The emotions it registered would be different from the ones he felt.

The final membrane between inner and outer is dissolving. 1984 can read like Orwell’s reverse autobiography, in which, rather than a life being built up, it gets disassembled down to its foundational unit. The body is now wasting; the voice is losing expressive competence. Worse, the face will soon enough have nothing left to express, as the last of his adaptive neurocircuitry becomes property of Oceania.

1984 is Orwell saying goodbye to himself, and an improbably convincing portrait of the erasure of the autonomous individual. He finished typing the novel by early December 1948. His final diary entry on Jura—dated that Christmas Eve—gave the weight of the Christmas goose “before drawing & plucking,” then concluded: “Snowdrops up all over the place. A few tulips showing. Some wall-flowers still trying to flower.” The next month, he was back in a sanatorium; the next year, he was dead. He was 46 years old.

1 984 was published 75 years ago. Surprisingly, it immediately surpassed Animal Farm as a critical and commercial success. One by one, Orwell’s contemporaries—V. S. Pritchett, Rebecca West, Bertrand Russell—acknowledged its triumph. A rare dissenter was Evelyn Waugh, who wrote to Orwell to say that he’d found the book morally inert. “You deny the soul’s existence (at least Winston does) and can only contrast matter with reason & will.” The trials of its protagonist consequently failed to make Waugh’s “flesh creep.” What, he implied, was at stake here?

Talk about missing the point. Nowhere in Orwell’s work can one find evidence of anything essential, much less eternal, that makes us human. That’s why Winston, our meager proxy, is available for a thoroughgoing reboot. As the book implies, we’re creatures of contingency all the way down. Even a memory of a memory of freedom, autonomy, self-making, consciousness, and agency—in a word, of ourselves—can disappear, until no loss is felt whatsoever. Hence the terror of being “the last man”: You’re the living terminus, the lone bearer of what will be, soon enough, a dead language.

A precious language, indicating a way of being in the world worth keeping—if you’re George Orwell. From the evidence of Jura and 1984 , persisting as his own catawampus self—askew to the world—was a habit he needed to prove he couldn’t possibly kick. He could be the far-off yet rooted man who loved being a father; performing what he deemed “sane” tasks, such as building a henhouse; indulging his grim compulsions (smoking tobacco and writing books). The soul, eternal fabric of God, had no place in that equation.

Waugh wasn’t the only muddled reader of the book. In the aftermath of the Berlin blockade and the creation of NATO , followed by the Soviets’ detonation of their first atomic weapon , readers—Americans, especially—might have been eager for an anti-Stalinist bedtime story. But Orwell had already written an anti-Stalinist bedtime story. If his time on Jura tells us anything, it’s that in 1984 , he was exhorting us to beware of concentrated power and pay attention to public language, yes, but above all, guard your solitude against interlopers, Stalinist or otherwise.

In addition to the book’s top-down anxieties about the coming managerial overclass, a bottom-up anxiety about how fragile solitude is—irreducible to an abstract right or a material good—permeates 1984 . Paradoxically, Winston’s efforts to hold fast to the bliss of separateness are what give the book its unexpected turns of beauty and humanity. (“The sweet summer air played against his cheek. From somewhere far away there floated the faint shouts of children: in the room itself there was no sound except the insect voice of the clock.”) For all of Orwell’s intrepidness, his physical courage, his clarity of expression, his most resolutely anti-fascist instinct lay here: in his terror at the thought of never being alone.

This article appears in the May 2024 print edition with the headline “Orwell’s Escape.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What Orwell Really Feared

The Isle of Jura is a patchwork of bogs and moorland laid across a quartzite slab in Scotland’s Inner Hebrides. Nearly 400 miles from London, rain-lashed, more deer than people: All the reasons not to move there were the reasons George Orwell moved there. Directions to houseguests ran several paragraphs and could include a plane, trains, taxis, a ferry, another ferry, then miles and miles on foot down a decrepit, often impassable rural lane. It’s safe to say the man wanted to get away. From what?

Orwell himself could be sentimental about his longing to escape (“Thinking always of my island in the Hebrides,” he’d once written in his wartime diary) or wonderfully blunt. In the aftermath of Hiroshima, he wrote to a friend:

This stupid war is coming off in abt 10–20 years, & this country will be blown off the map whatever else happens. The only hope is to have a home with a few animals in some place not worth a bomb.

It helps also to remember Orwell’s immediate state of mind when he finally fully moved to Jura, in May 1946. Four months before Hiroshima, his wife, Eileen, had died; shortly after the atomic bomb was dropped, Animal Farm was published.

[ From the March 1947 issue: George Orwell’s ‘The Prevention of Literature’ ]

Almost at once, in other words, Orwell became a widower, terrified by the coming postwar reality, and famous—the latter a condition he seems to have regarded as nothing but a bother. His newfound sense of dread was only adding to one he’d felt since 1943, when news of the Tehran Conference broke. The meeting had been ominous to Orwell: It placed in his head the idea of Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin divvying up the postwar world, leading to a global triopoly of super-states. The man can be forgiven for pouring every ounce of his grief, self-pity, paranoia (literary lore had it that he thought Stalin might have an ice pick with his name on it), and embittered egoism into the predicament of his latest protagonist, Winston Smith.

Unsurprisingly, given that it culminated in both his masterpiece and his death, Orwell’s time on the island has been picked over by biographers, but Orwell’s Island: George, Jura and 1984 , by Les Wilson, treats it as a subject worthy of stand-alone attention. The book is at odds with our sense of Orwell as an intrepid journalist. It is a portrait of a man jealously guarding his sense of himself as a creature elementally apart, even as he depicts the horrors of a world in which the human capacity for apartness is being hunted down and destroyed.

Wilson is a former political journalist, not a critic, who lives on neighboring Islay, famous for its whiskeys. He is at pains to show how Orwell, on Jura, overcame one of his laziest prejudices: The author went from taking every opportunity to laugh at the Scots for their “burns, braes, kilts, sporrans, claymores, bagpipes” (who is better at the derisive list than Orwell?) to complaining about the relative lack of Gaelic-language radio programming.

Scottish had come to mean something more to him than kailyard kitsch. These were a people holding out against a fully amalgamated identity, beginning with the Kingdom of Great Britain and extending to modernity itself. On Jura at least, crofters and fishermen still lived at a village scale. As to whether Jura represented, as has been suggested, suicide by other means—Orwell was chronically ill, and Barnhill, his cottage, was 25 miles from the island’s one doctor—Wilson brushes this aside. In fact, he argues that Jura was “kinder to Orwell’s ravaged lungs than smog-smothered London,” where inhabitants were burning scavenged wood to stay warm.

At Barnhill, Orwell set up almost a society in miniature, devoting his 16-acre homestead to his ideal of self-sufficiency. Soon after moving there, he was joined by his sister, his 2-year-old adopted son, and a nanny. Amid the general, often biting, austerity of postwar Europe, they enjoyed a private cornucopia, subsisting on, as Wilson says, a diet of “fish, lobster, rabbit, venison and fresh milk and eggs,” and were often warmed by peat that Orwell himself had cut. He intended to live there for the rest of his life, raising his son and relishing an existence as a non-cog in a noncapitalist machine.

[ From the July 2019 issue: Doublethink is stronger than Orwell imagined ]

He lived without electricity or phone; shot rabbits “for the pot,” as Wilson says; raised geese to be slaughtered and plucked; and fished the surrounding waters in a dinghy. He fashioned a tobacco pouch from animal skin and a mustard spoon out of deer bone, and served his aghast guests a seaweed blancmange. Over time, absconding to Jura and writing 1984 became aspects of a single premonition: a coming world of perpetual engulfment by the forces of bigness. As Orwell’s latest biographer, D. J. Taylor, has pointed out in Orwell: The New Life , Orwell’s novels before Animal Farm followed a common template of a sensitive young person going up against a heartless society, destined to lose. Eileen is the one who helped him—either by suggesting that Animal Farm be told as a fable or by lightening his touch, depending on whom you talk to—find a newly engaging, even playful (in its way), register.

The loss of Eileen and return of the self-pitying Orwell alter ego are certainly linked. And indeed, in 1984 he produces his most Orwellian novel, in both senses—only now both protagonist and situation are presented in the absolute extreme : The young man is the bearer (if we believe his tormentor, O’Brien) of the last shred of human autonomy, in a society both totally corrupt and laying total claim to his being.

What this absolutism produced, of course, was not another fusty neo-Edwardian novel à la Orwell’s earlier Keep the Aspidistra Flying , but a wild, aggrieved tour de force of dystopian erotica. Odd though it may sound, given the novel’s unremitting torments, 1984 quickly became a best seller, in no small part because its first readers, especially in America, found it comforting—a source of the release you might feel, in a darkened theater, when you remember that you yourself are not being chased by a man with a chain saw. The reader could glance up, notice no limitless police powers or kangaroo inquisitions, and say: We are not them .

Such complacency is hard to come by in 2024. Thinking of Orwell, famous though he is for his windowpane prose and the prescience of his essays, as the ultimate sane human being is not so easy either. Rereading 1984 in light of the Jura episode suggests that Orwell was an altogether weirder person, and his last novel an altogether weirder book, than we’ve appreciated.