Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper

Writing a research paper is both an art and a skill, and knowing how to write the methods section of a research paper is the first crucial step in mastering scientific writing. If, like the majority of early career researchers, you believe that the methods section is the simplest to write and needs little in the way of careful consideration or thought, this article will help you understand it is not 1 .

We have all probably asked our supervisors, coworkers, or search engines “ how to write a methods section of a research paper ” at some point in our scientific careers, so you are not alone if that’s how you ended up here. Even for seasoned researchers, selecting what to include in the methods section from a wealth of experimental information can occasionally be a source of distress and perplexity.

Additionally, journal specifications, in some cases, may make it more of a requirement rather than a choice to provide a selective yet descriptive account of the experimental procedure. Hence, knowing these nuances of how to write the methods section of a research paper is critical to its success. The methods section of the research paper is not supposed to be a detailed heavy, dull section that some researchers tend to write; rather, it should be the central component of the study that justifies the validity and reliability of the research.

Are you still unsure of how the methods section of a research paper forms the basis of every investigation? Consider the last article you read but ignore the methods section and concentrate on the other parts of the paper . Now think whether you could repeat the study and be sure of the credibility of the findings despite knowing the literature review and even having the data in front of you. You have the answer!

Having established the importance of the methods section , the next question is how to write the methods section of a research paper that unifies the overall study. The purpose of the methods section , which was earlier called as Materials and Methods , is to describe how the authors went about answering the “research question” at hand. Here, the objective is to tell a coherent story that gives a detailed account of how the study was conducted, the rationale behind specific experimental procedures, the experimental setup, objects (variables) involved, the research protocol employed, tools utilized to measure, calculations and measurements, and the analysis of the collected data 2 .

In this article, we will take a deep dive into this topic and provide a detailed overview of how to write the methods section of a research paper . For the sake of clarity, we have separated the subject into various sections with corresponding subheadings.

Table of Contents

What is the methods section of a research paper ?

The methods section is a fundamental section of any paper since it typically discusses the ‘ what ’, ‘ how ’, ‘ which ’, and ‘ why ’ of the study, which is necessary to arrive at the final conclusions. In a research article, the introduction, which serves to set the foundation for comprehending the background and results is usually followed by the methods section, which precedes the result and discussion sections. The methods section must explicitly state what was done, how it was done, which equipment, tools and techniques were utilized, how were the measurements/calculations taken, and why specific research protocols, software, and analytical methods were employed.

Why is the methods section important?

The primary goal of the methods section is to provide pertinent details about the experimental approach so that the reader may put the results in perspective and, if necessary, replicate the findings 3 . This section offers readers the chance to evaluate the reliability and validity of any study. In short, it also serves as the study’s blueprint, assisting researchers who might be unsure about any other portion in establishing the study’s context and validity. The methods plays a rather crucial role in determining the fate of the article; an incomplete and unreliable methods section can frequently result in early rejections and may lead to numerous rounds of modifications during the publication process. This means that the reviewers also often use methods section to assess the reliability and validity of the research protocol and the data analysis employed to address the research topic. In other words, the purpose of the methods section is to demonstrate the research acumen and subject-matter expertise of the author(s) in their field.

Structure of methods section of a research paper

Similar to the research paper, the methods section also follows a defined structure; this may be dictated by the guidelines of a specific journal or can be presented in a chronological or thematic manner based on the study type. When writing the methods section , authors should keep in mind that they are telling a story about how the research was conducted. They should only report relevant information to avoid confusing the reader and include details that would aid in connecting various aspects of the entire research activity together. It is generally advisable to present experiments in the order in which they were conducted. This facilitates the logical flow of the research and allows readers to follow the progression of the study design.

It is also essential to clearly state the rationale behind each experiment and how the findings of earlier experiments informed the design or interpretation of later experiments. This allows the readers to understand the overall purpose of the study design and the significance of each experiment within that context. However, depending on the particular research question and method, it may make sense to present information in a different order; therefore, authors must select the best structure and strategy for their individual studies.

In cases where there is a lot of information, divide the sections into subheadings to cover the pertinent details. If the journal guidelines pose restrictions on the word limit , additional important information can be supplied in the supplementary files. A simple rule of thumb for sectioning the method section is to begin by explaining the methodological approach ( what was done ), describing the data collection methods ( how it was done ), providing the analysis method ( how the data was analyzed ), and explaining the rationale for choosing the methodological strategy. This is described in detail in the upcoming sections.

How to write the methods section of a research paper

Contrary to widespread assumption, the methods section of a research paper should be prepared once the study is complete to prevent missing any key parameter. Hence, please make sure that all relevant experiments are done before you start writing a methods section . The next step for authors is to look up any applicable academic style manuals or journal-specific standards to ensure that the methods section is formatted correctly. The methods section of a research paper typically constitutes materials and methods; while writing this section, authors usually arrange the information under each category.

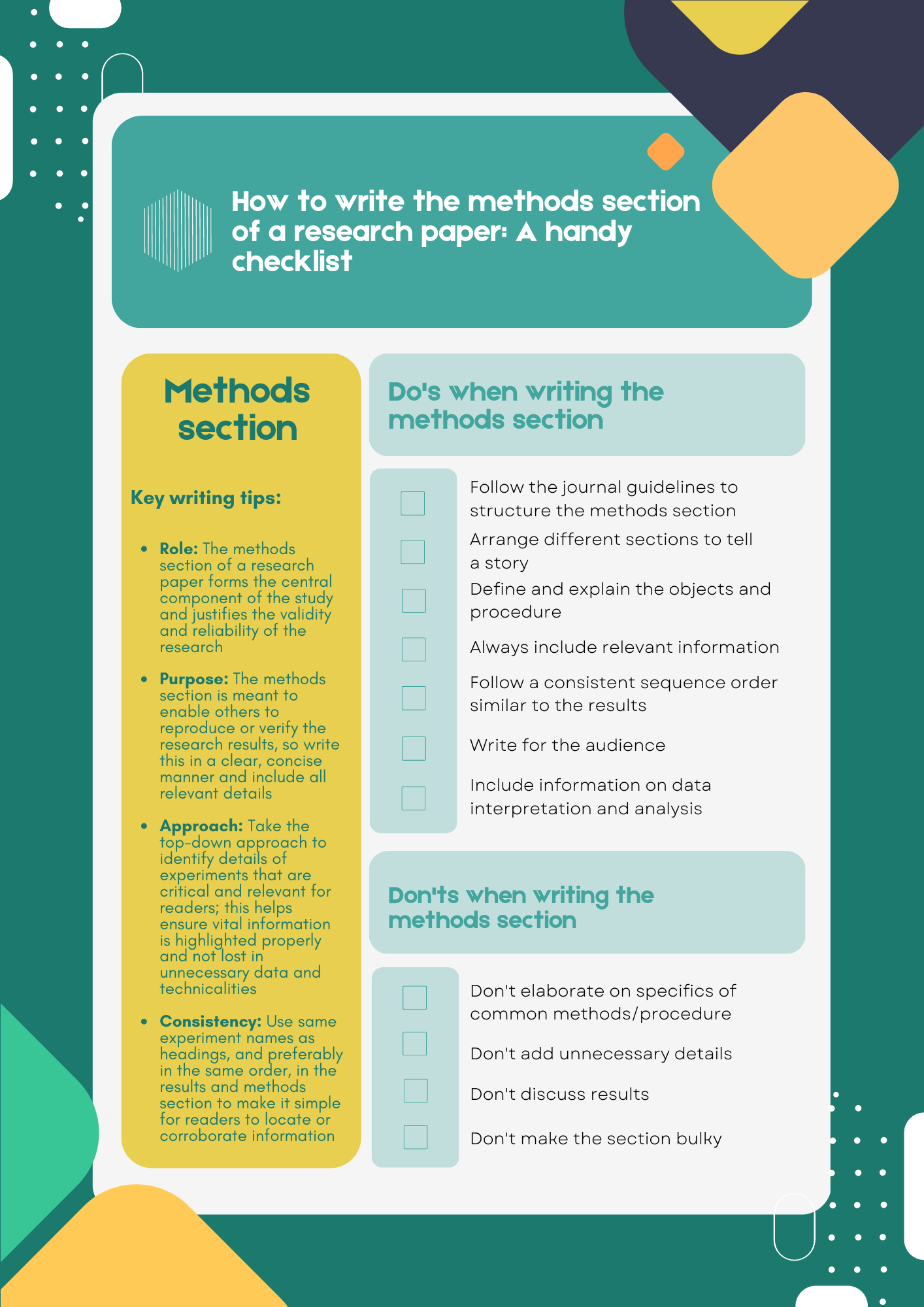

The materials category describes the samples, materials, treatments, and instruments, while experimental design, sample preparation, data collection, and data analysis are a part of the method category. According to the nature of the study, authors should include additional subsections within the methods section, such as ethical considerations like the declaration of Helsinki (for studies involving human subjects), demographic information of the participants, and any other crucial information that can affect the output of the study. Simply put, the methods section has two major components: content and format. Here is an easy checklist for you to consider if you are struggling with how to write the methods section of a research paper .

- Explain the research design, subjects, and sample details

- Include information on inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Mention ethical or any other permission required for the study

- Include information about materials, experimental setup, tools, and software

- Add details of data collection and analysis methods

- Incorporate how research biases were avoided or confounding variables were controlled

- Evaluate and justify the experimental procedure selected to address the research question

- Provide precise and clear details of each experiment

- Flowcharts, infographics, or tables can be used to present complex information

- Use past tense to show that the experiments have been done

- Follow academic style guides (such as APA or MLA ) to structure the content

- Citations should be included as per standard protocols in the field

Now that you know how to write the methods section of a research paper , let’s address another challenge researchers face while writing the methods section —what to include in the methods section . How much information is too much is not always obvious when it comes to trying to include data in the methods section of a paper. In the next section, we examine this issue and explore potential solutions.

What to include in the methods section of a research paper

The technical nature of the methods section occasionally makes it harder to present the information clearly and concisely while staying within the study context. Many young researchers tend to veer off subject significantly, and they frequently commit the sin of becoming bogged down in itty bitty details, making the text harder to read and impairing its overall flow. However, the best way to write the methods section is to start with crucial components of the experiments. If you have trouble deciding which elements are essential, think about leaving out those that would make it more challenging to comprehend the context or replicate the results. The top-down approach helps to ensure all relevant information is incorporated and vital information is not lost in technicalities. Next, remember to add details that are significant to assess the validity and reliability of the study. Here is a simple checklist for you to follow ( bonus tip: you can also make a checklist for your own study to avoid missing any critical information while writing the methods section ).

- Structuring the methods section : Authors should diligently follow journal guidelines and adhere to the specific author instructions provided when writing the methods section . Journals typically have specific guidelines for formatting the methods section ; for example, Frontiers in Plant Sciences advises arranging the materials and methods section by subheading and citing relevant literature. There are several standardized checklists available for different study types in the biomedical field, including CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) for randomized clinical trials, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis) for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, and STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) for cohort, case-control, cross-sectional studies. Before starting the methods section , check the checklist available in your field that can function as a guide.

- Organizing different sections to tell a story : Once you are sure of the format required for structuring the methods section , the next is to present the sections in a logical manner; as mentioned earlier, the sections can be organized according to the chronology or themes. In the chronological arrangement, you should discuss the methods in accordance with how the experiments were carried out. An example of the method section of a research paper of an animal study should first ideally include information about the species, weight, sex, strain, and age. Next, the number of animals, their initial conditions, and their living and housing conditions should also be mentioned. Second, how the groups are assigned and the intervention (drug treatment, stress, or other) given to each group, and finally, the details of tools and techniques used to measure, collect, and analyze the data. Experiments involving animal or human subjects should additionally state an ethics approval statement. It is best to arrange the section using the thematic approach when discussing distinct experiments not following a sequential order.

- Define and explain the objects and procedure: Experimental procedure should clearly be stated in the methods section . Samples, necessary preparations (samples, treatment, and drug), and methods for manipulation need to be included. All variables (control, dependent, independent, and confounding) must be clearly defined, particularly if the confounding variables can affect the outcome of the study.

- Match the order of the methods section with the order of results: Though not mandatory, organizing the manuscript in a logical and coherent manner can improve the readability and clarity of the paper. This can be done by following a consistent structure throughout the manuscript; readers can easily navigate through the different sections and understand the methods and results in relation to each other. Using experiment names as headings for both the methods and results sections can also make it simpler for readers to locate specific information and corroborate it if needed.

- Relevant information must always be included: The methods section should have information on all experiments conducted and their details clearly mentioned. Ask the journal whether there is a way to offer more information in the supplemental files or external repositories if your target journal has strict word limitations. For example, Nature communications encourages authors to deposit their step-by-step protocols in an open-resource depository, Protocol Exchange which allows the protocols to be linked with the manuscript upon publication. Providing access to detailed protocols also helps to increase the transparency and reproducibility of the research.

- It’s all in the details: The methods section should meticulously list all the materials, tools, instruments, and software used for different experiments. Specify the testing equipment on which data was obtained, together with its manufacturer’s information, location, city, and state or any other stimuli used to manipulate the variables. Provide specifics on the research process you employed; if it was a standard protocol, cite previous studies that also used the protocol. Include any protocol modifications that were made, as well as any other factors that were taken into account when planning the study or gathering data. Any new or modified techniques should be explained by the authors. Typically, readers evaluate the reliability and validity of the procedures using the cited literature, and a widely accepted checklist helps to support the credibility of the methodology. Note: Authors should include a statement on sample size estimation (if applicable), which is often missed. It enables the reader to determine how many subjects will be required to detect the expected change in the outcome variables within a given confidence interval.

- Write for the audience: While explaining the details in the methods section , authors should be mindful of their target audience, as some of the rationale or assumptions on which specific procedures are based might not always be obvious to the audience, particularly for a general audience. Therefore, when in doubt, the objective of a procedure should be specified either in relation to the research question or to the entire protocol.

- Data interpretation and analysis : Information on data processing, statistical testing, levels of significance, and analysis tools and software should be added. Mention if the recommendations and expertise of an experienced statistician were followed. Also, evaluate and justify the preferred statistical method used in the study and its significance.

What NOT to include in the methods section of a research paper

To address “ how to write the methods section of a research paper ”, authors should not only pay careful attention to what to include but also what not to include in the methods section of a research paper . Here is a list of do not’s when writing the methods section :

- Do not elaborate on specifics of standard methods/procedures: You should refrain from adding unnecessary details of experiments and practices that are well established and cited previously. Instead, simply cite relevant literature or mention if the manufacturer’s protocol was followed.

- Do not add unnecessary details : Do not include minute details of the experimental procedure and materials/instruments used that are not significant for the outcome of the experiment. For example, there is no need to mention the brand name of the water bath used for incubation.

- Do not discuss the results: The methods section is not to discuss the results or refer to the tables and figures; save it for the results and discussion section. Also, focus on the methods selected to conduct the study and avoid diverting to other methods or commenting on their pros or cons.

- Do not make the section bulky : For extensive methods and protocols, provide the essential details and share the rest of the information in the supplemental files. The writing should be clear yet concise to maintain the flow of the section.

We hope that by this point, you understand how crucial it is to write a thoughtful and precise methods section and the ins and outs of how to write the methods section of a research paper . To restate, the entire purpose of the methods section is to enable others to reproduce the results or verify the research. We sincerely hope that this post has cleared up any confusion and given you a fresh perspective on the methods section .

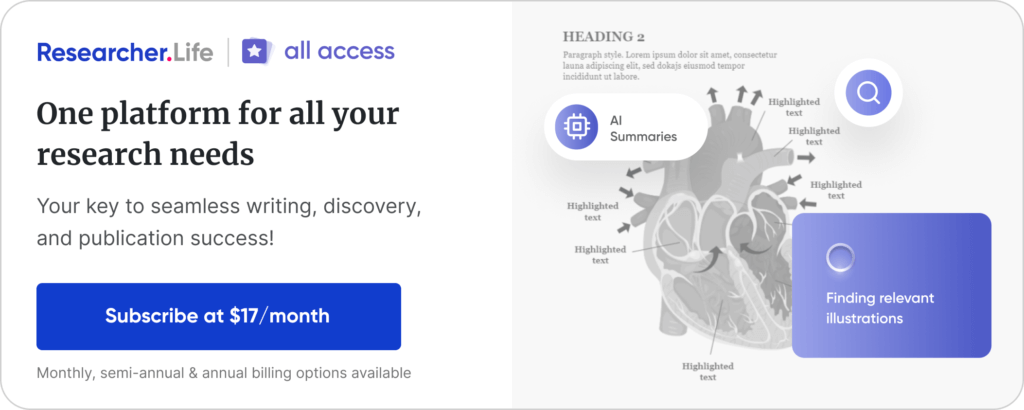

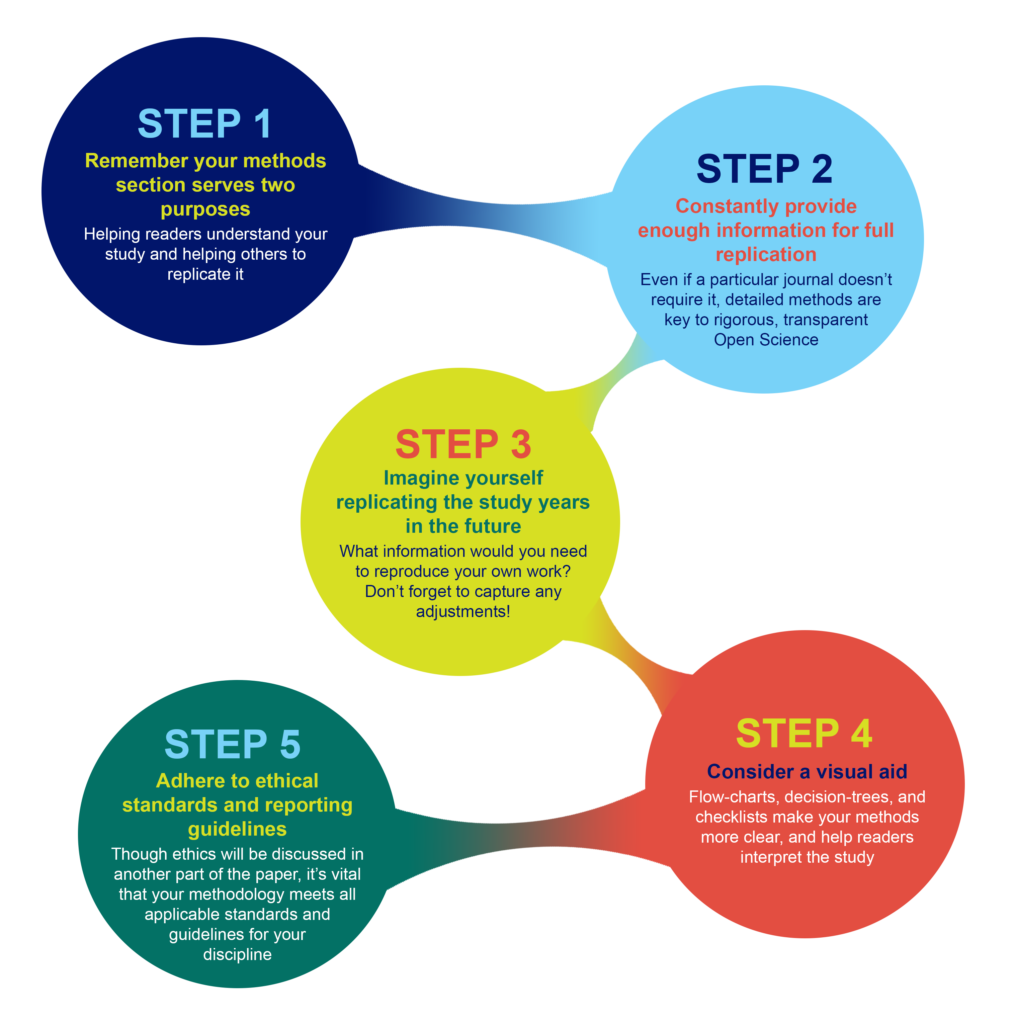

As a parting gift, we’re leaving you with a handy checklist that will help you understand how to write the methods section of a research paper . Feel free to download this checklist and use or share this with those who you think may benefit from it.

References

- Bhattacharya, D. How to write the Methods section of a research paper. Editage Insights, 2018. https://www.editage.com/insights/how-to-write-the-methods-section-of-a-research-paper (2018).

- Kallet, R. H. How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper. Respiratory Care 49, 1229–1232 (2004). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15447808/

- Grindstaff, T. L. & Saliba, S. A. AVOIDING MANUSCRIPT MISTAKES. Int J Sports Phys Ther 7, 518–524 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3474299/

Researcher.Life is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Researcher.Life All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 21+ years of experience in academia, Researcher.Life All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $17 a month !

Related Posts

What is a Case Study in Research? Definition, Methods, and Examples

Take Top AI Tools for Researchers for a Spin with the Editage All Access 7-Day Pass!

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Your Methods

Ensure understanding, reproducibility and replicability

What should you include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate?

Why Methods Matter

The methods section was once the most likely part of a paper to be unfairly abbreviated, overly summarized, or even relegated to hard-to-find sections of a publisher’s website. While some journals may responsibly include more detailed elements of methods in supplementary sections, the movement for increased reproducibility and rigor in science has reinstated the importance of the methods section. Methods are now viewed as a key element in establishing the credibility of the research being reported, alongside the open availability of data and results.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability.

For example, the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology project set out in 2013 to replicate experiments from 50 high profile cancer papers, but revised their target to 18 papers once they understood how much methodological detail was not contained in the original papers.

What to include in your methods section

What you include in your methods sections depends on what field you are in and what experiments you are performing. However, the general principle in place at the majority of journals is summarized well by the guidelines at PLOS ONE : “The Materials and Methods section should provide enough detail to allow suitably skilled investigators to fully replicate your study. ” The emphases here are deliberate: the methods should enable readers to understand your paper, and replicate your study. However, there is no need to go into the level of detail that a lay-person would require—the focus is on the reader who is also trained in your field, with the suitable skills and knowledge to attempt a replication.

A constant principle of rigorous science

A methods section that enables other researchers to understand and replicate your results is a constant principle of rigorous, transparent, and Open Science. Aim to be thorough, even if a particular journal doesn’t require the same level of detail . Reproducibility is all of our responsibility. You cannot create any problems by exceeding a minimum standard of information. If a journal still has word-limits—either for the overall article or specific sections—and requires some methodological details to be in a supplemental section, that is OK as long as the extra details are searchable and findable .

Imagine replicating your own work, years in the future

As part of PLOS’ presentation on Reproducibility and Open Publishing (part of UCSF’s Reproducibility Series ) we recommend planning the level of detail in your methods section by imagining you are writing for your future self, replicating your own work. When you consider that you might be at a different institution, with different account logins, applications, resources, and access levels—you can help yourself imagine the level of specificity that you yourself would require to redo the exact experiment. Consider:

- Which details would you need to be reminded of?

- Which cell line, or antibody, or software, or reagent did you use, and does it have a Research Resource ID (RRID) that you can cite?

- Which version of a questionnaire did you use in your survey?

- Exactly which visual stimulus did you show participants, and is it publicly available?

- What participants did you decide to exclude?

- What process did you adjust, during your work?

Tip: Be sure to capture any changes to your protocols

You yourself would want to know about any adjustments, if you ever replicate the work, so you can surmise that anyone else would want to as well. Even if a necessary adjustment you made was not ideal, transparency is the key to ensuring this is not regarded as an issue in the future. It is far better to transparently convey any non-optimal methods, or methodological constraints, than to conceal them, which could result in reproducibility or ethical issues downstream.

Visual aids for methods help when reading the whole paper

Consider whether a visual representation of your methods could be appropriate or aid understanding your process. A visual reference readers can easily return to, like a flow-diagram, decision-tree, or checklist, can help readers to better understand the complete article, not just the methods section.

Ethical Considerations

In addition to describing what you did, it is just as important to assure readers that you also followed all relevant ethical guidelines when conducting your research. While ethical standards and reporting guidelines are often presented in a separate section of a paper, ensure that your methods and protocols actually follow these guidelines. Read more about ethics .

Existing standards, checklists, guidelines, partners

While the level of detail contained in a methods section should be guided by the universal principles of rigorous science outlined above, various disciplines, fields, and projects have worked hard to design and develop consistent standards, guidelines, and tools to help with reporting all types of experiment. Below, you’ll find some of the key initiatives. Ensure you read the submission guidelines for the specific journal you are submitting to, in order to discover any further journal- or field-specific policies to follow, or initiatives/tools to utilize.

Tip: Keep your paper moving forward by providing the proper paperwork up front

Be sure to check the journal guidelines and provide the necessary documents with your manuscript submission. Collecting the necessary documentation can greatly slow the first round of peer review, or cause delays when you submit your revision.

Randomized Controlled Trials – CONSORT The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) project covers various initiatives intended to prevent the problems of inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials. The primary initiative is an evidence-based minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials known as the CONSORT Statement .

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – PRISMA The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses ( PRISMA ) is an evidence-based minimum set of items focusing on the reporting of reviews evaluating randomized trials and other types of research.

Research using Animals – ARRIVE The Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments ( ARRIVE ) guidelines encourage maximizing the information reported in research using animals thereby minimizing unnecessary studies. (Original study and proposal , and updated guidelines , in PLOS Biology .)

Laboratory Protocols Protocols.io has developed a platform specifically for the sharing and updating of laboratory protocols , which are assigned their own DOI and can be linked from methods sections of papers to enhance reproducibility. Contextualize your protocol and improve discovery with an accompanying Lab Protocol article in PLOS ONE .

Consistent reporting of Materials, Design, and Analysis – the MDAR checklist A cross-publisher group of editors and experts have developed, tested, and rolled out a checklist to help establish and harmonize reporting standards in the Life Sciences . The checklist , which is available for use by authors to compile their methods, and editors/reviewers to check methods, establishes a minimum set of requirements in transparent reporting and is adaptable to any discipline within the Life Sciences, by covering a breadth of potentially relevant methodological items and considerations. If you are in the Life Sciences and writing up your methods section, try working through the MDAR checklist and see whether it helps you include all relevant details into your methods, and whether it reminded you of anything you might have missed otherwise.

Summary Writing tips

The main challenge you may find when writing your methods is keeping it readable AND covering all the details needed for reproducibility and replicability. While this is difficult, do not compromise on rigorous standards for credibility!

- Keep in mind future replicability, alongside understanding and readability.

- Follow checklists, and field- and journal-specific guidelines.

- Consider a commitment to rigorous and transparent science a personal responsibility, and not just adhering to journal guidelines.

- Establish whether there are persistent identifiers for any research resources you use that can be specifically cited in your methods section.

- Deposit your laboratory protocols in Protocols.io, establishing a permanent link to them. You can update your protocols later if you improve on them, as can future scientists who follow your protocols.

- Consider visual aids like flow-diagrams, lists, to help with reading other sections of the paper.

- Be specific about all decisions made during the experiments that someone reproducing your work would need to know.

Don’t

- Summarize or abbreviate methods without giving full details in a discoverable supplemental section.

- Presume you will always be able to remember how you performed the experiments, or have access to private or institutional notebooks and resources.

- Attempt to hide constraints or non-optimal decisions you had to make–transparency is the key to ensuring the credibility of your research.

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.

- Provide background and a rationale for methodologies that are unfamiliar for your readers . Very often in the social sciences, research problems and the methods for investigating them require more explanation/rationale than widely accepted rules governing the natural and physical sciences. Be clear and concise in your explanation.

- Provide a justification for subject selection and sampling procedure . For instance, if you propose to conduct interviews, how do you intend to select the sample population? If you are analyzing texts, which texts have you chosen, and why? If you are using statistics, why is this set of data being used? If other data sources exist, explain why the data you chose is most appropriate to addressing the research problem.

- Provide a justification for case study selection . A common method of analyzing research problems in the social sciences is to analyze specific cases. These can be a person, place, event, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis that are either examined as a singular topic of in-depth investigation or multiple topics of investigation studied for the purpose of comparing or contrasting findings. In either method, you should explain why a case or cases were chosen and how they specifically relate to the research problem.

- Describe potential limitations . Are there any practical limitations that could affect your data collection? How will you attempt to control for potential confounding variables and errors? If your methodology may lead to problems you can anticipate, state this openly and show why pursuing this methodology outweighs the risk of these problems cropping up.

NOTE: Once you have written all of the elements of the methods section, subsequent revisions should focus on how to present those elements as clearly and as logically as possibly. The description of how you prepared to study the research problem, how you gathered the data, and the protocol for analyzing the data should be organized chronologically. For clarity, when a large amount of detail must be presented, information should be presented in sub-sections according to topic. If necessary, consider using appendices for raw data.

ANOTHER NOTE: If you are conducting a qualitative analysis of a research problem , the methodology section generally requires a more elaborate description of the methods used as well as an explanation of the processes applied to gathering and analyzing of data than is generally required for studies using quantitative methods. Because you are the primary instrument for generating the data [e.g., through interviews or observations], the process for collecting that data has a significantly greater impact on producing the findings. Therefore, qualitative research requires a more detailed description of the methods used.

YET ANOTHER NOTE: If your study involves interviews, observations, or other qualitative techniques involving human subjects , you may be required to obtain approval from the university's Office for the Protection of Research Subjects before beginning your research. This is not a common procedure for most undergraduate level student research assignments. However, i f your professor states you need approval, you must include a statement in your methods section that you received official endorsement and adequate informed consent from the office and that there was a clear assessment and minimization of risks to participants and to the university. This statement informs the reader that your study was conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. In some cases, the approval notice is included as an appendix to your paper.

III. Problems to Avoid

Irrelevant Detail The methodology section of your paper should be thorough but concise. Do not provide any background information that does not directly help the reader understand why a particular method was chosen, how the data was gathered or obtained, and how the data was analyzed in relation to the research problem [note: analyzed, not interpreted! Save how you interpreted the findings for the discussion section]. With this in mind, the page length of your methods section will generally be less than any other section of your paper except the conclusion.

Unnecessary Explanation of Basic Procedures Remember that you are not writing a how-to guide about a particular method. You should make the assumption that readers possess a basic understanding of how to investigate the research problem on their own and, therefore, you do not have to go into great detail about specific methodological procedures. The focus should be on how you applied a method , not on the mechanics of doing a method. An exception to this rule is if you select an unconventional methodological approach; if this is the case, be sure to explain why this approach was chosen and how it enhances the overall process of discovery.

Problem Blindness It is almost a given that you will encounter problems when collecting or generating your data, or, gaps will exist in existing data or archival materials. Do not ignore these problems or pretend they did not occur. Often, documenting how you overcame obstacles can form an interesting part of the methodology. It demonstrates to the reader that you can provide a cogent rationale for the decisions you made to minimize the impact of any problems that arose.

Literature Review Just as the literature review section of your paper provides an overview of sources you have examined while researching a particular topic, the methodology section should cite any sources that informed your choice and application of a particular method [i.e., the choice of a survey should include any citations to the works you used to help construct the survey].

It’s More than Sources of Information! A description of a research study's method should not be confused with a description of the sources of information. Such a list of sources is useful in and of itself, especially if it is accompanied by an explanation about the selection and use of the sources. The description of the project's methodology complements a list of sources in that it sets forth the organization and interpretation of information emanating from those sources.

Azevedo, L.F. et al. "How to Write a Scientific Paper: Writing the Methods Section." Revista Portuguesa de Pneumologia 17 (2011): 232-238; Blair Lorrie. “Choosing a Methodology.” In Writing a Graduate Thesis or Dissertation , Teaching Writing Series. (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers 2016), pp. 49-72; Butin, Dan W. The Education Dissertation A Guide for Practitioner Scholars . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010; Carter, Susan. Structuring Your Research Thesis . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; Kallet, Richard H. “How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper.” Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004):1229-1232; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. Methods Section. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Rudestam, Kjell Erik and Rae R. Newton. “The Method Chapter: Describing Your Research Plan.” In Surviving Your Dissertation: A Comprehensive Guide to Content and Process . (Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015), pp. 87-115; What is Interpretive Research. Institute of Public and International Affairs, University of Utah; Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Methods and Materials. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Writing Tip

Statistical Designs and Tests? Do Not Fear Them!

Don't avoid using a quantitative approach to analyzing your research problem just because you fear the idea of applying statistical designs and tests. A qualitative approach, such as conducting interviews or content analysis of archival texts, can yield exciting new insights about a research problem, but it should not be undertaken simply because you have a disdain for running a simple regression. A well designed quantitative research study can often be accomplished in very clear and direct ways, whereas, a similar study of a qualitative nature usually requires considerable time to analyze large volumes of data and a tremendous burden to create new paths for analysis where previously no path associated with your research problem had existed.

To locate data and statistics, GO HERE .

Another Writing Tip

Knowing the Relationship Between Theories and Methods

There can be multiple meaning associated with the term "theories" and the term "methods" in social sciences research. A helpful way to delineate between them is to understand "theories" as representing different ways of characterizing the social world when you research it and "methods" as representing different ways of generating and analyzing data about that social world. Framed in this way, all empirical social sciences research involves theories and methods, whether they are stated explicitly or not. However, while theories and methods are often related, it is important that, as a researcher, you deliberately separate them in order to avoid your theories playing a disproportionate role in shaping what outcomes your chosen methods produce.

Introspectively engage in an ongoing dialectic between the application of theories and methods to help enable you to use the outcomes from your methods to interrogate and develop new theories, or ways of framing conceptually the research problem. This is how scholarship grows and branches out into new intellectual territory.

Reynolds, R. Larry. Ways of Knowing. Alternative Microeconomics . Part 1, Chapter 3. Boise State University; The Theory-Method Relationship. S-Cool Revision. United Kingdom.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Methods and the Methodology

Do not confuse the terms "methods" and "methodology." As Schneider notes, a method refers to the technical steps taken to do research . Descriptions of methods usually include defining and stating why you have chosen specific techniques to investigate a research problem, followed by an outline of the procedures you used to systematically select, gather, and process the data [remember to always save the interpretation of data for the discussion section of your paper].

The methodology refers to a discussion of the underlying reasoning why particular methods were used . This discussion includes describing the theoretical concepts that inform the choice of methods to be applied, placing the choice of methods within the more general nature of academic work, and reviewing its relevance to examining the research problem. The methodology section also includes a thorough review of the methods other scholars have used to study the topic.

Bryman, Alan. "Of Methods and Methodology." Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 3 (2008): 159-168; Schneider, Florian. “What's in a Methodology: The Difference between Method, Methodology, and Theory…and How to Get the Balance Right?” PoliticsEastAsia.com. Chinese Department, University of Leiden, Netherlands.

- << Previous: Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Next: Qualitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Here's What You Need to Understand About Research Methodology

Table of Contents

Research methodology involves a systematic and well-structured approach to conducting scholarly or scientific inquiries. Knowing the significance of research methodology and its different components is crucial as it serves as the basis for any study.

Typically, your research topic will start as a broad idea you want to investigate more thoroughly. Once you’ve identified a research problem and created research questions , you must choose the appropriate methodology and frameworks to address those questions effectively.

What is the definition of a research methodology?

Research methodology is the process or the way you intend to execute your study. The methodology section of a research paper outlines how you plan to conduct your study. It covers various steps such as collecting data, statistical analysis, observing participants, and other procedures involved in the research process

The methods section should give a description of the process that will convert your idea into a study. Additionally, the outcomes of your process must provide valid and reliable results resonant with the aims and objectives of your research. This thumb rule holds complete validity, no matter whether your paper has inclinations for qualitative or quantitative usage.

Studying research methods used in related studies can provide helpful insights and direction for your own research. Now easily discover papers related to your topic on SciSpace and utilize our AI research assistant, Copilot , to quickly review the methodologies applied in different papers.

The need for a good research methodology

While deciding on your approach towards your research, the reason or factors you weighed in choosing a particular problem and formulating a research topic need to be validated and explained. A research methodology helps you do exactly that. Moreover, a good research methodology lets you build your argument to validate your research work performed through various data collection methods, analytical methods, and other essential points.

Just imagine it as a strategy documented to provide an overview of what you intend to do.

While undertaking any research writing or performing the research itself, you may get drifted in not something of much importance. In such a case, a research methodology helps you to get back to your outlined work methodology.

A research methodology helps in keeping you accountable for your work. Additionally, it can help you evaluate whether your work is in sync with your original aims and objectives or not. Besides, a good research methodology enables you to navigate your research process smoothly and swiftly while providing effective planning to achieve your desired results.

What is the basic structure of a research methodology?

Usually, you must ensure to include the following stated aspects while deciding over the basic structure of your research methodology:

1. Your research procedure

Explain what research methods you’re going to use. Whether you intend to proceed with quantitative or qualitative, or a composite of both approaches, you need to state that explicitly. The option among the three depends on your research’s aim, objectives, and scope.

2. Provide the rationality behind your chosen approach

Based on logic and reason, let your readers know why you have chosen said research methodologies. Additionally, you have to build strong arguments supporting why your chosen research method is the best way to achieve the desired outcome.

3. Explain your mechanism

The mechanism encompasses the research methods or instruments you will use to develop your research methodology. It usually refers to your data collection methods. You can use interviews, surveys, physical questionnaires, etc., of the many available mechanisms as research methodology instruments. The data collection method is determined by the type of research and whether the data is quantitative data(includes numerical data) or qualitative data (perception, morale, etc.) Moreover, you need to put logical reasoning behind choosing a particular instrument.

4. Significance of outcomes

The results will be available once you have finished experimenting. However, you should also explain how you plan to use the data to interpret the findings. This section also aids in understanding the problem from within, breaking it down into pieces, and viewing the research problem from various perspectives.

5. Reader’s advice

Anything that you feel must be explained to spread more awareness among readers and focus groups must be included and described in detail. You should not just specify your research methodology on the assumption that a reader is aware of the topic.

All the relevant information that explains and simplifies your research paper must be included in the methodology section. If you are conducting your research in a non-traditional manner, give a logical justification and list its benefits.

6. Explain your sample space

Include information about the sample and sample space in the methodology section. The term "sample" refers to a smaller set of data that a researcher selects or chooses from a larger group of people or focus groups using a predetermined selection method. Let your readers know how you are going to distinguish between relevant and non-relevant samples. How you figured out those exact numbers to back your research methodology, i.e. the sample spacing of instruments, must be discussed thoroughly.

For example, if you are going to conduct a survey or interview, then by what procedure will you select the interviewees (or sample size in case of surveys), and how exactly will the interview or survey be conducted.

7. Challenges and limitations

This part, which is frequently assumed to be unnecessary, is actually very important. The challenges and limitations that your chosen strategy inherently possesses must be specified while you are conducting different types of research.

The importance of a good research methodology

You must have observed that all research papers, dissertations, or theses carry a chapter entirely dedicated to research methodology. This section helps maintain your credibility as a better interpreter of results rather than a manipulator.

A good research methodology always explains the procedure, data collection methods and techniques, aim, and scope of the research. In a research study, it leads to a well-organized, rationality-based approach, while the paper lacking it is often observed as messy or disorganized.

You should pay special attention to validating your chosen way towards the research methodology. This becomes extremely important in case you select an unconventional or a distinct method of execution.

Curating and developing a strong, effective research methodology can assist you in addressing a variety of situations, such as:

- When someone tries to duplicate or expand upon your research after few years.

- If a contradiction or conflict of facts occurs at a later time. This gives you the security you need to deal with these contradictions while still being able to defend your approach.

- Gaining a tactical approach in getting your research completed in time. Just ensure you are using the right approach while drafting your research methodology, and it can help you achieve your desired outcomes. Additionally, it provides a better explanation and understanding of the research question itself.

- Documenting the results so that the final outcome of the research stays as you intended it to be while starting.

Instruments you could use while writing a good research methodology

As a researcher, you must choose which tools or data collection methods that fit best in terms of the relevance of your research. This decision has to be wise.

There exists many research equipments or tools that you can use to carry out your research process. These are classified as:

a. Interviews (One-on-One or a Group)

An interview aimed to get your desired research outcomes can be undertaken in many different ways. For example, you can design your interview as structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. What sets them apart is the degree of formality in the questions. On the other hand, in a group interview, your aim should be to collect more opinions and group perceptions from the focus groups on a certain topic rather than looking out for some formal answers.

In surveys, you are in better control if you specifically draft the questions you seek the response for. For example, you may choose to include free-style questions that can be answered descriptively, or you may provide a multiple-choice type response for questions. Besides, you can also opt to choose both ways, deciding what suits your research process and purpose better.

c. Sample Groups

Similar to the group interviews, here, you can select a group of individuals and assign them a topic to discuss or freely express their opinions over that. You can simultaneously note down the answers and later draft them appropriately, deciding on the relevance of every response.

d. Observations

If your research domain is humanities or sociology, observations are the best-proven method to draw your research methodology. Of course, you can always include studying the spontaneous response of the participants towards a situation or conducting the same but in a more structured manner. A structured observation means putting the participants in a situation at a previously decided time and then studying their responses.

Of all the tools described above, it is you who should wisely choose the instruments and decide what’s the best fit for your research. You must not restrict yourself from multiple methods or a combination of a few instruments if appropriate in drafting a good research methodology.

Types of research methodology

A research methodology exists in various forms. Depending upon their approach, whether centered around words, numbers, or both, methodologies are distinguished as qualitative, quantitative, or an amalgamation of both.

1. Qualitative research methodology

When a research methodology primarily focuses on words and textual data, then it is generally referred to as qualitative research methodology. This type is usually preferred among researchers when the aim and scope of the research are mainly theoretical and explanatory.

The instruments used are observations, interviews, and sample groups. You can use this methodology if you are trying to study human behavior or response in some situations. Generally, qualitative research methodology is widely used in sociology, psychology, and other related domains.

2. Quantitative research methodology

If your research is majorly centered on data, figures, and stats, then analyzing these numerical data is often referred to as quantitative research methodology. You can use quantitative research methodology if your research requires you to validate or justify the obtained results.

In quantitative methods, surveys, tests, experiments, and evaluations of current databases can be advantageously used as instruments If your research involves testing some hypothesis, then use this methodology.

3. Amalgam methodology

As the name suggests, the amalgam methodology uses both quantitative and qualitative approaches. This methodology is used when a part of the research requires you to verify the facts and figures, whereas the other part demands you to discover the theoretical and explanatory nature of the research question.

The instruments for the amalgam methodology require you to conduct interviews and surveys, including tests and experiments. The outcome of this methodology can be insightful and valuable as it provides precise test results in line with theoretical explanations and reasoning.

The amalgam method, makes your work both factual and rational at the same time.

Final words: How to decide which is the best research methodology?

If you have kept your sincerity and awareness intact with the aims and scope of research well enough, you must have got an idea of which research methodology suits your work best.

Before deciding which research methodology answers your research question, you must invest significant time in reading and doing your homework for that. Taking references that yield relevant results should be your first approach to establishing a research methodology.

Moreover, you should never refrain from exploring other options. Before setting your work in stone, you must try all the available options as it explains why the choice of research methodology that you finally make is more appropriate than the other available options.

You should always go for a quantitative research methodology if your research requires gathering large amounts of data, figures, and statistics. This research methodology will provide you with results if your research paper involves the validation of some hypothesis.

Whereas, if you are looking for more explanations, reasons, opinions, and public perceptions around a theory, you must use qualitative research methodology.The choice of an appropriate research methodology ultimately depends on what you want to achieve through your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Research Methodology

1. how to write a research methodology.

You can always provide a separate section for research methodology where you should specify details about the methods and instruments used during the research, discussions on result analysis, including insights into the background information, and conveying the research limitations.

2. What are the types of research methodology?

There generally exists four types of research methodology i.e.

- Observation

- Experimental

- Derivational

3. What is the true meaning of research methodology?

The set of techniques or procedures followed to discover and analyze the information gathered to validate or justify a research outcome is generally called Research Methodology.

4. Where lies the importance of research methodology?

Your research methodology directly reflects the validity of your research outcomes and how well-informed your research work is. Moreover, it can help future researchers cite or refer to your research if they plan to use a similar research methodology.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Using AI for research: A beginner’s guide

- How it works

Published by Nicolas at March 21st, 2024 , Revised On March 12, 2024

The Ultimate Guide To Research Methodology

Research methodology is a crucial aspect of any investigative process, serving as the blueprint for the entire research journey. If you are stuck in the methodology section of your research paper , then this blog will guide you on what is a research methodology, its types and how to successfully conduct one.

Table of Contents

What Is Research Methodology?

Research methodology can be defined as the systematic framework that guides researchers in designing, conducting, and analyzing their investigations. It encompasses a structured set of processes, techniques, and tools employed to gather and interpret data, ensuring the reliability and validity of the research findings.

Research methodology is not confined to a singular approach; rather, it encapsulates a diverse range of methods tailored to the specific requirements of the research objectives.

Here is why Research methodology is important in academic and professional settings.

Facilitating Rigorous Inquiry

Research methodology forms the backbone of rigorous inquiry. It provides a structured approach that aids researchers in formulating precise thesis statements , selecting appropriate methodologies, and executing systematic investigations. This, in turn, enhances the quality and credibility of the research outcomes.

Ensuring Reproducibility And Reliability

In both academic and professional contexts, the ability to reproduce research outcomes is paramount. A well-defined research methodology establishes clear procedures, making it possible for others to replicate the study. This not only validates the findings but also contributes to the cumulative nature of knowledge.

Guiding Decision-Making Processes

In professional settings, decisions often hinge on reliable data and insights. Research methodology equips professionals with the tools to gather pertinent information, analyze it rigorously, and derive meaningful conclusions.

This informed decision-making is instrumental in achieving organizational goals and staying ahead in competitive environments.

Contributing To Academic Excellence

For academic researchers, adherence to robust research methodology is a hallmark of excellence. Institutions value research that adheres to high standards of methodology, fostering a culture of academic rigour and intellectual integrity. Furthermore, it prepares students with critical skills applicable beyond academia.

Enhancing Problem-Solving Abilities

Research methodology instills a problem-solving mindset by encouraging researchers to approach challenges systematically. It equips individuals with the skills to dissect complex issues, formulate hypotheses , and devise effective strategies for investigation.

Understanding Research Methodology

In the pursuit of knowledge and discovery, understanding the fundamentals of research methodology is paramount.

Basics Of Research

Research, in its essence, is a systematic and organized process of inquiry aimed at expanding our understanding of a particular subject or phenomenon. It involves the exploration of existing knowledge, the formulation of hypotheses, and the collection and analysis of data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Research is a dynamic and iterative process that contributes to the continuous evolution of knowledge in various disciplines.

Types of Research

Research takes on various forms, each tailored to the nature of the inquiry. Broadly classified, research can be categorized into two main types:

- Quantitative Research: This type involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to identify patterns, relationships, and statistical significance. It is particularly useful for testing hypotheses and making predictions.

- Qualitative Research: Qualitative research focuses on understanding the depth and details of a phenomenon through non-numerical data. It often involves methods such as interviews, focus groups, and content analysis, providing rich insights into complex issues.

Components Of Research Methodology

To conduct effective research, one must go through the different components of research methodology. These components form the scaffolding that supports the entire research process, ensuring its coherence and validity.

Research Design

Research design serves as the blueprint for the entire research project. It outlines the overall structure and strategy for conducting the study. The three primary types of research design are:

- Exploratory Research: Aimed at gaining insights and familiarity with the topic, often used in the early stages of research.

- Descriptive Research: Involves portraying an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon, answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Explanatory Research: Seeks to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how.’

Data Collection Methods

Choosing the right data collection methods is crucial for obtaining reliable and relevant information. Common methods include:

- Surveys and Questionnaires: Employed to gather information from a large number of respondents through standardized questions.

- Interviews: In-depth conversations with participants, offering qualitative insights.

- Observation: Systematic watching and recording of behaviour, events, or processes in their natural setting.

Data Analysis Techniques

Once data is collected, analysis becomes imperative to derive meaningful conclusions. Different methodologies exist for quantitative and qualitative data:

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Involves statistical techniques such as descriptive statistics, inferential statistics, and regression analysis to interpret numerical data.

- Qualitative Data Analysis: Methods like content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory are employed to extract patterns, themes, and meanings from non-numerical data.

The research paper we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Choosing a Research Method

Selecting an appropriate research method is a critical decision in the research process. It determines the approach, tools, and techniques that will be used to answer the research questions.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data, providing a structured and objective approach to understanding and explaining phenomena.

Experimental Research

Experimental research involves manipulating variables to observe the effect on another variable under controlled conditions. It aims to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Key Characteristics:

- Controlled Environment: Experiments are conducted in a controlled setting to minimize external influences.

- Random Assignment: Participants are randomly assigned to different experimental conditions.

- Quantitative Data: Data collected is numerical, allowing for statistical analysis.

Applications: Commonly used in scientific studies and psychology to test hypotheses and identify causal relationships.

Survey Research

Survey research gathers information from a sample of individuals through standardized questionnaires or interviews. It aims to collect data on opinions, attitudes, and behaviours.

- Structured Instruments: Surveys use structured instruments, such as questionnaires, to collect data.

- Large Sample Size: Surveys often target a large and diverse group of participants.

- Quantitative Data Analysis: Responses are quantified for statistical analysis.

Applications: Widely employed in social sciences, marketing, and public opinion research to understand trends and preferences.

Descriptive Research

Descriptive research seeks to portray an accurate profile of a situation or phenomenon. It focuses on answering the ‘what,’ ‘who,’ ‘where,’ and ‘when’ questions.

- Observation and Data Collection: This involves observing and documenting without manipulating variables.

- Objective Description: Aim to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: T his can include both types of data, depending on the research focus.

Applications: Useful in situations where researchers want to understand and describe a phenomenon without altering it, common in social sciences and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research emphasizes exploring and understanding the depth and complexity of phenomena through non-numerical data.

A case study is an in-depth exploration of a particular person, group, event, or situation. It involves detailed, context-rich analysis.

- Rich Data Collection: Uses various data sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents.

- Contextual Understanding: Aims to understand the context and unique characteristics of the case.

- Holistic Approach: Examines the case in its entirety.

Applications: Common in social sciences, psychology, and business to investigate complex and specific instances.

Ethnography

Ethnography involves immersing the researcher in the culture or community being studied to gain a deep understanding of their behaviours, beliefs, and practices.

- Participant Observation: Researchers actively participate in the community or setting.

- Holistic Perspective: Focuses on the interconnectedness of cultural elements.

- Qualitative Data: In-depth narratives and descriptions are central to ethnographic studies.

Applications: Widely used in anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies to explore and document cultural practices.

Grounded Theory

Grounded theory aims to develop theories grounded in the data itself. It involves systematic data collection and analysis to construct theories from the ground up.

- Constant Comparison: Data is continually compared and analyzed during the research process.

- Inductive Reasoning: Theories emerge from the data rather than being imposed on it.

- Iterative Process: The research design evolves as the study progresses.

Applications: Commonly applied in sociology, nursing, and management studies to generate theories from empirical data.

Research design is the structural framework that outlines the systematic process and plan for conducting a study. It serves as the blueprint, guiding researchers on how to collect, analyze, and interpret data.

Exploratory, Descriptive, And Explanatory Designs

Exploratory design.

Exploratory research design is employed when a researcher aims to explore a relatively unknown subject or gain insights into a complex phenomenon.

- Flexibility: Allows for flexibility in data collection and analysis.

- Open-Ended Questions: Uses open-ended questions to gather a broad range of information.

- Preliminary Nature: Often used in the initial stages of research to formulate hypotheses.

Applications: Valuable in the early stages of investigation, especially when the researcher seeks a deeper understanding of a subject before formalizing research questions.

Descriptive Design

Descriptive research design focuses on portraying an accurate profile of a situation, group, or phenomenon.

- Structured Data Collection: Involves systematic and structured data collection methods.

- Objective Presentation: Aims to provide an unbiased and factual account of the subject.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data: Can incorporate both types of data, depending on the research objectives.

Applications: Widely used in social sciences, marketing, and educational research to provide detailed and objective descriptions.

Explanatory Design

Explanatory research design aims to identify the causes and effects of a phenomenon, explaining the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind observed relationships.

- Causal Relationships: Seeks to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Controlled Variables : Often involves controlling certain variables to isolate causal factors.

- Quantitative Analysis: Primarily relies on quantitative data analysis techniques.

Applications: Commonly employed in scientific studies and social sciences to delve into the underlying reasons behind observed patterns.

Cross-Sectional Vs. Longitudinal Designs

Cross-sectional design.

Cross-sectional designs collect data from participants at a single point in time.

- Snapshot View: Provides a snapshot of a population at a specific moment.

- Efficiency: More efficient in terms of time and resources.

- Limited Temporal Insights: Offers limited insights into changes over time.

Applications: Suitable for studying characteristics or behaviours that are stable or not expected to change rapidly.

Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal designs involve the collection of data from the same participants over an extended period.

- Temporal Sequence: Allows for the examination of changes over time.

- Causality Assessment: Facilitates the assessment of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Resource-Intensive: Requires more time and resources compared to cross-sectional designs.