2 Minute Speech On Online Classes During Lockdown In English

Good morning to everyone in this room. I would like to thank the principal, the teachers, and my dear friends for allowing me to speak to you today about online classes during lockdown. Online lessons were substituted for teacher-led lectures when the school was under lockdown.

Students could access online study materials, participate in virtual lectures, ask lecturers questions, interact with other students, administer virtual tests, and do a lot more. Students would receive a high-quality education from home while simultaneously preventing the spread of viruses thanks to online classrooms.

Everything in online classes was prewritten. It was devoid of feelings like joy, enthusiasm, or rage. Thus, online education has both benefits and drawbacks, but in those days with curfews, it was incredibly beneficial in ensuring uninterrupted study. Thank you.

Related Posts:

Main navigation

English teaching and learning during the covid crisis, english teaching and learning during the covid crisis: online classes and upskilling teachers.

Graeme Harrison explores how English language teachers can help students learn in online classes by combining digital resources with existing skills.

Since many countries have imposed a lockdown on movement, and many schools have subsequently closed their doors, vast numbers of previously tech-shy teachers are having to learn very quickly how to teach using online resources. This might be through delivering lessons using virtual classrooms or providing online self-study material for students, both of which may be new modes of lesson delivery for many.

Since the rise of the internet in the 1990s, English language (EL) teachers have had what might be described as a difficult relationship with technology. Initial teacher education has been slow to embrace digital ways of teaching and learning, meaning that many EL teachers feel that they have been poorly prepared to use technology in their teaching (Clark, 2018). Consequently, many EL teachers have been resistant to the digital wave which has revolutionised other areas of our lives. Understandably, there are a number of worries which teachers have regarding introducing technology into teaching. Three of the most common are:

- Technology is isolating – learner interaction is limited, and dissimilar to the kind of ways that they will be required to use language in the real world.

- Teachers are being deskilled, and the essence of teaching is being lost.

- The rise of technology, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), will soon mean that teachers are made redundant.

To deal with these one at a time:

Is technology isolating for teachers?

In many situations, technology can actually facilitate interaction. We only need think of how many of us now use our phones and social media such as WhatsApp or Facebook to communicate. This can be equally true of interaction in a virtual learning environment – if managed correctly, opportunities for language use can be optimised and students will have plenty of interaction with each other. And, whether we like it or not, these forms of interaction, mediated through digital channels, now account for a high percentage of interactions in the ‘real world’.

Are EL teachers being deskilled?

EL teaching has long since stopped being a static discipline, in which teachers are primarily conveyors of declarative knowledge, i.e. facts or information. Nowadays, English teachers are better conceptualised as facilitators of learning who provide learning opportunities for their students, and give feedback to support improvement. The essence of teaching is not therefore something fixed but rather dynamic, adapting to the context and situation in which each teacher finds themselves. The facilitation of learning through technology is a highly skilled endeavour, and in many contexts can offer a really useful support to the classroom, providing students with the chance to learn in new and interesting ways.

The impact of artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence is a 21st century spectre which haunts many professions. However, a study into which jobs are likely to be replaced by AI in the future (Frey & Osborne, 2013) found that the chances of the profession of school teacher disappearing was around 0.007, i.e. very low indeed, especially when compared with jobs such as Library Assistants (0.95), Real Estate Brokers (0.97) and Telemarketers (0.99).

This is because teaching is a complex job, requiring a range of skills, such as subject knowledge, classroom management, motivational skills, delivering feedback, differentiating learning, problem solving, emotional intelligence, counselling, etc. – the list is almost endless.

This contrasts with the current state of AI, which can be described as ‘domain specific’, i.e. highly skilled but in one particular area, e.g. playing chess, driving a car, recognising human faces or speech. The ‘domain general’ skills which a teacher possesses, and the complex interaction between those, is not going to be matched by machines anytime soon.

How Cambridge English is helping

Part of the reason that EL teaching has been slow to adopt new ways of teaching through technology has been because in many contexts, schools lack motivation and/or resources to implement tech solutions in and around the classroom, and therefore, the demand for skilled digital teachers has been weak. That is clearly changing, fuelled by the need of our education systems to keep students learning through these challenging times.

There is therefore a clear and immediate necessity for professional development in teaching through technology for many teachers around the world, and Cambridge English is trying to support this need through a number of initiatives:

- Firstly, a free Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) - Teaching English Online - has been launched to help teachers acquire the skills needed to teach online. The first iteration of the course attracted over 50,000 participants.

- Next, a series of webinars has begun to help teachers who are working virtually. These include titles such as ‘Resilience: teaching in tough times’ and ‘Managing interaction and feedback in the virtual classroom’. See Webinars for teachers page for more details and to sign up.

- We have also produced a special web page called Supporting Every Teacher which brings together a series of useful teaching resources such as lesson plans, online activities, and our flagship Write & Improve resource, which allows students to get immediate feedback on their writing through our innovative AI algorithm.

- Finally, for those of you involved in preparing students for the A2 Key for Schools exam, Exam Lift is a new free app available from the Google Play and Apple Stores which provides engaging and motivating practice material for students to self-study.

We are also continuing to provide our services to ministries of education during this time. A collection of materials, including those mentioned above, from us and our sister organisation the Cambridge University Press are available.

We appreciate that these are difficult times, but hope that this training and these resources can help in a small way to support teachers who are delivering virtual classes or producing online resources, perhaps for the first time. It is said that every cloud has a silver lining, and perhaps when this is all over, we will see online learning, with the pedagogical advantages it offers, becoming a more integral part of teaching around the world.

Clark, T. (2018). Key Challenges and Pedagogical Implications: International Teacher Perspectives. Cambridge English internal report.

Frey, B. K. and Osborne, M. A. (2013). The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation?

Related Articles

Five ways a celta qualification will further your career.

Choosing the right English language teaching course for you can be a challenge. Here are five reasons why we recommend taking an official Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (CELTA) qualification from Cambridge.

Real life English language skills for business – how Linguaskill can help

Linguaskill is a quick and convenient online test to help organisations check the English levels of individuals and groups of candidates, powered by Artificial Intelligence technology. It tests all four language skills - speaking, writing, reading and listening - in modules.

Linguaskill: the flexible option for language testing

Linguaskill’s modular testing offers a flexible option to test takers. If they need to improve their score in a particular skill, then they can take that part of the test again. Their other scores are unaffected and they won’t have to retake the other three sections. Linguaskill’s flexibility benefits institutions and employers, too. Let’s take a look.

Mediation skills in the English language classroom

Taking information, summarising it, and passing it on is an example of what linguists call mediation, and it is a key skill for language learners at all levels. It’s the subject of the latest Cambridge Paper in ELT which looks at some of the best strategies teachers can use to teach and assess mediation skills.

COVID-19: A Framework for Effective Delivering of Online Classes During Lockdown

- Arena of Pandemic

- Published: 30 January 2021

- Volume 5 , pages 322–336, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Digvijay Pandey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0353-174X 1 ,

- Gabriel A. Ogunmola 2 ,

- Wegayehu Enbeyle 3 ,

- Marzuk Abdullahi 4 ,

- Binay Kumar Pandey 5 &

- Sabyasachi Pramanik 6

19k Accesses

25 Citations

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 12 May 2021

This article has been updated

The world as we know it has changed over a short period of time, with the rise and spread of the deadly novel Corona virus known as COVID-19, the world will never be the same again. This study explores the devastating effects of the novel virus pandemic, the resulting lockdown, thus the need to transform the offline classroom into an online classroom. It explores and describes the numerous online teaching platforms, study materials, techniques, and technologies’ being used to ensure that educating the students does not stop. Furthermore, it identifies the platforms, technologies which can be used to conduct online examination in a safe environment devoid of cheating. Additionally, it explores the challenges facing the deployment of online teaching methods. On the basis of literature review, a framework was proposed to deliver superior online class room experience for the students, so that online classroom is as effective as or even better than offline classrooms. The identified variables were empirically tested with the aid of a structured questionnaire; there were 487(according to Craitier and Morgan)150 number of respondents who were purposefully sampled. The results indicate that students prefer the multimedia means of studies. As a result of binary logistic regression, poor internet connection, awareness on COVID-19, enough sources of materials, recommends massive open online course, favourite online methods, and satisfaction with online study are significant in the model or attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic at 5% level of significance. The study recommends online teaching methods, but finally, the study concludes that satisfaction with online study is significant in the model or attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic at 5% level of significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

COVID-19: Creating a Paradigm Shift in Indian Education System

Covid-19: Study of Online Teaching, Availability and Use of Technological Resources

Challenges Faced by the University Students During COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Corona virus pandemic is a strange viral infection that is highly transmittable especially from person to person. The COVID-19 infectivity that is caused by a completely unique mental strain of corona virus was first detected in Wuhan, China, in the last week of December 2019 and acknowledged a world health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization on January 30, 2020. The World Health Organization has confirmed the fast-moving coronavirus outbreak in China, a “world health emergency of worldwide concern” ( https://doi.org/10.1021/cen-09805-buscon4 ). Eventually, the disease continues to spread across the globe, killing many, and collapsing the various economic, educational, and social activities across the globe.

Death rate ranges between 2 and 3%. It is drastically less severe than 2003 SARS (MR 10%) or 2012 MERS (MR 35%) outbreaks. Threat of decease is merely high in older people (above an age of ~ 60 years) and other people with pre-active health conditions, and approximately 80% of individuals have gentle symptoms and get over the sickness in 2 weeks. The majority of the symptoms are often treated on time medication (John Hopkins Center for System Science and Engineering (Live dashboard), as reported on March 11, 2020).

In view of the forgoing, all institutions of learning across the globe are subjected to an imminent and unavoidable indefinite break. This is an attempt to stop the virus from affecting the students or the teachers. This however has brought about lackadaisical attitudes among the students at home because they are idle and thus thinking nothing but evil.

Most countries across in the world including my country, Nigeria, have developed a way of engaging this students at home, and in some developed countries like the USA, students have resume back to school facelessly (via online). In Nigeria; a platform was developed online for educational used by students and any other researcher (academia.nitda.gov.ng). This is a laudable initiative but hampered by resources like electricity, internet, and to some awareness.

Consequently, all hands are now on desk, reviewing academic online platforms and updating it to meet up with the peculiarities of our day-to-day challenges while making it easy for studies and evaluations of student’s academic performance. This is the quest for this research work. Research problem: the global method of teaching is physical dialogue, whereby students and teachers will meet on a scheduled venue and physically interact. With the advent of these pandemic, public gatherings are prohibited; this makes it impossible for teaching to continue, so long as there is going to be person-to-person contact.

Hence, the need for a platform that will substitute the obsolete means of teaching in an effective and efficient method with the capability of evaluating students academic performance is imminent. Research gap: there are no academic researches on this topic; researches are yet to study online classes platforms, etc.

Objectives: The study explores and describes the present state of online classes, opportunities, and challenges. It is a novel research on the techniques and method adopted by teachers to bring the offline classroom online. The key goal of the learning is to assess socio-demographic and related factors on the attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic in India.

Literature Review

The approach of online-learning as an aspect of the synergistic study worldwide incorporates Web 2.0 advances, which are in the main used by our understudies and are presently enhancing into the homeroom. Teachers state that these innovative advances extremely help increments to their DE homerooms as they will upgrade learning among our technically knowledgeable understudies, reflecting the usage of those advances in their day-by-day lives. Web 2.0 main advances incorporate wikis, sites, broadcasts, informal communities, and online video-sharing destinations like YouTube. Teachers and scientists can foresee that new advances will in any case be presented, which can require transformation by the two understudies and educators, upheld by examination by analysts on their viability. It is essential to appear for “hints on how e-learning advances can turn out to be ground-breaking impetuses for change additionally as devices for updating our education and instructional frameworks” (Shroff & Vogel, 2009 , p.60).

The developing of instructional stages, likewise referenced as Knowledge Management Systems (KMS), is another advancement in ongoing DE history. Saadé & Kira ( 2009 ) depict Learning Management Systems (LMS) as a structure that has educator instruments, learning measure apparatuses, and a store of information. Tests of KMS stages incorporate WebCT, Blackboard, and DesireToLearn, which have risen on the grounds that the best three LMS are unavoidable in the present DE condition. Last Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment (Moodle) has developed as a substitution to LMS open-source framework, a free option to the previously mentioned stages (Unal & Unal, 2011 ). It is fundamental that the devices executed help the course tasks, exercises, and substance (Singh et al. 2010 ; Smart & Cappel, 2006 ). “Unmistakably, innovation upheld learning conditions can possibly flexibly instruments and structure to modify training” (Shroff & Vogel, 2009 , p. 60). The researchers used in this investigation are presented to Blackboard LMS through which understudies partake in conversation gatherings, online diaries, Wikis, Web-based testing and practice tests, virtual groups, YouTube, and other intelligent devices.

The idea of online-learning and hence the plan to utilize Moodle in college option came after a progression of global temporary jobs we were included and after a progression of on-line classes and stage setup for improving instructing ventures. There are numerous advantages of utilizing online instruction together with correspondence, collaboration between understudies, bunch improvement, and a superior admittance to information. Regardless of those advantages, numerous Romanian colleges regularly consent to stay in customary instructing without extra help. Moodle might be a learning stage initially planned by Martin Dougiamas (first form of Moodle was delivered on August 20, 2002). Moodle, as a solid open-source e-learning stage, was utilized and created by worldwide cooperative exertion of global network. Moodle is implied and proceed with improved to flexibly instructors, directors, and students with one vigorous, secure, and incorporated framework to make customized learning conditions. Presently, on March 27, 2014, Moodle 2.6.2 was launched. We consider Moodle a Web-based versatile community-oriented learning condition that contains all parts portrayed by Wang et al. ( 2004 ): conversation gathering and one-on-one companion help client model, collective methodology model, and versatile segment. A few creators were likewise inquisitive about cooperation and human correspondence on a Web-based collaborative learning environment (Zhang et al. 2004 ), while different creators call these virtual learning situations (Knight & Halkett, 2010 ). Comparative encounters of utilizing intelligent e-learning instruments as Moodle were portrayed by different creators (Beatty & Ulasewicz, 2006 ). They all pointed in their papers (Shen et al., 2006 ) that utilizing Moodle can build up understudies’ psychological blueprint, help to develop their insight, advance understudies’ uplifting mentalities towards talking about and helping out companions, and increment understudies’ aptitudes to embrace deep-rooted learning by utilizing the information innovation. Options as far as Web-based collaborative learning are given by Pfahl et al. ( 2001 ). During this adaptable online network for learning, understudies collaborate with course assets and are prepared to grow new abilities and to structure their own learning direction. Applying this e-learning stage, we exploited understudy’s spare time and their accessibility to spend and structure their activities (Arbaugh et al. 2009 ) in order to submit schoolwork regarding a firm cutoff time.

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) and open education research (OER) MOOCs are online courses that by and large permit anybody to enrol and complete without any extra fee (at any rate for the fundamental course). Cormier and Siemens [8] contend that they are a possible result of “open educating and study.” The degree of receptiveness in MOOCs varies from course to course and if the course is realistic on a MOOC stage, relying on the stage. While numerous cMOOCs offered its substance utilizing open authorizing, other MOOC suppliers just give the substance to privately utilize it as it were. For example, Coursera, single among the main xMOOC stages (Kibaru, 2018 ), expresses that the texture is “just for your very own, non-business use. you'll not in any case duplicate, imitate, retransmit, disseminate, distribute, monetarily abuse or in any case move any material, nor may you alter or make subsidiaries mechanism of the material” ( Rabe-Hemp et al., 2009 ). In this manner, yet a “by item” of the open education development, MOOCs appear to be less open than OERs, uninhibitedly available instructive substance, which are for the most part delivered with open authorizing.

E-learning Tools for Distance Education

With the growing concerns over COVID-19, many school districts have moved classroom instruction online for the foreseeable future. We understand that this change can present challenges on many levels for educators, administrators, students, and families. The following recommended tools may be helpful in making the transition to digital learning during this difficult time. These resources include general e-learning tools for educators, subject-based tools for students, and extensions to assist students with learning differences. Almost all of these resources are free, with the exception of a few inexpensive tools/available free trials (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2020.)

Tool name | Description | Links | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

Age of Learning | Offering free access to ABCMouse, ReadingIQ, etc. to those affected by COVID-19 closures |

| Free |

Biteable | Simple video creation/editing tool |

| Free |

Canva | Tool to design graphics, infographics, etc |

| Free |

EdModo | Tool for communicating and sharing classroom content |

| free |

Factile | Tool to create review games, like Jeopardy |

| Free |

Khan Academy | Online lessons and resources for K-12 educators to use, as well as AP/SAT prep |

| Free |

Nearpod | Tool for creating simple, interactive presentations that can easily be shared | E-Learning: | Free |

Padlet | Tool for educators to create digital bulletin boards or webpages |

| Free |

TesTeach | Tool for educators to create interactive presentations, lessons, or projects |

| Free |

WIX | Simple, free website builder |

| Free |

Code.org | Activities and resources for K-12 students to learn basic computer science/coding |

| Free |

SOURCE: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2020

Descriptive Analysis of Tools of Online Class MOOC

Impartus : This is the main video proposal for OER and training. Around 130 higher institutions in India are currently using this platform ( http://www.impartus.com ).

Webex : Webex is an online tool that allows you to virtually hold meetings without leaving your homes or offices. It only requires a computer with an internet access and a separate phone line. This is a product of Cisco Company and is capable giving access to up to 100 clients at a time. It is free to sign up but requires $49/month subscription ( http://www.webex.com ).

Zoom : This is another online livestreaming tool but it is a mobile app. It is available on Android and iOS. While online, you can record sessions, collaborate on projects, and share or annotate one another’s screen. It cost $14.99/month, and it allows meetings recording on the cloud. It has unlimited number of participants, but the meetings can only last for 40 min ( https://zoom.us ).

Google Classroom : This is an open source Web service provided by Google for education and training with the sole aspire of online evaluation of test and assignment in a paperless way. However, organizations must register their corporate account on G-Suit before they can use this service. The students only need a valid email account to get connected to the class. This is linked to Google Drive, Google Docs, and Gmail for efficient sharing of resources ( https://classroom.google.com ).

Microsoft Teams : This is designed by Microsoft as an all-round collaborative platform offering: chats, voice, and calling features. It allows instant messaging with inbuilt office 365 for manipulating documents with live stream. All you need to do is to subscribe to the Microsoft 365 business essentials package; however, this package cost $5/month and per single user ( https://support.office.com ).

Descriptive Tools for Online Classes

Internet learning content is available through various types (text, pictures, sounds, and curios) (Moore & Kearsley, 2012 ) and kinds of media (versatile, intelligent, account, profitable) (Laurillard, 2002 ). The educated client can utilize different Web-based learning assets to make a learning domain that suits his own adapting needs (for example, learning styles, singular openness needs, inspiration); moreover, to the information on different kinds of ICT, it is critical to know somebody’s very own adapting needs (Grant et al., 2009 ).

There are many online tools that are already in use to achieve online classes. It depends on the resources available for the organization to subscribe to such online services. Each of these tools has its own advantages and disadvantages in terms of security, cost, and regional peculiarities. The below table can assist in analyzing some selected tools based on their cost and security.

Tool | Cost | Advantage | Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

Impartus | Free hosting and $49/module annually | The higher your number of students, the cheaper the subscriptions and have relative authentication system for security | This is feasible in developed countries where internet and power are not a challenge |

Webex | Free hosting, $49/month charged for subscriptions annually | It is capable of connecting up to 100 clients at a time, and it has in build cryptographic security model | This is most feasible to Cisco hardware but not limited to Cisco and requires stable power and internet |

Zoom | 7-days free trial then you can choose from three different platforms ranging from $14.99/per month | Real-time feedback, custom support, and job ready skills but limited to only 40 min per session and relatively secured | This is feasible on Android and iOS software. It is a mobile application but limited to only 40 min per session |

Google Classroom | Free | Dedicated to only subscribed clients, and features are customized according to clients’ wants. Secured with SSL encryption | This is feasible to low-level institutions with financial challenges. It is free and operates on both mobile and computer. It has an embedded examination evaluation software |

Microsoft Teams | Free hosting and subscription of $5/month to all connected clients | Very scalable and user friendly | This is feasible to developed organizations with no financial or manpower-related challenges. It requires a subscription and real-time manipulation of texts/documents using an inbuilt Office365 |

Descriptive Analysis of Tools of Online Examination

For a complete online classroom, there is a need for an equivalent system/platform in place for an online examination evaluation. Many of such platforms are readily available online. It is left for organizations to analyse the available systems and choose the best that suits their requirements considering the cost and security of the model. Below are some selected tools fitted for that purpose;

TCexam : This is an open source system for electronic exam. It is also known as computer-based assessment (CBA) and computer-based test (CBT). It is free and does not require additional hardware to run.

Virtualx : This is a free online exam management information system. It is cloud-based, and it is an open source. It is user friendly and scalable to user requirements.

Moodle : This is a learning platform or course management system that is aimed at online automation of examinations. It gives the opportunity for lecturers to create their own personal websites. It is free and open source.

FlexiQuiz : This is a main online test producer that will work without human intervention and mark and grade your quizzes. It is an open source and free. And it is secured with SSL encryption technology.

EdBase : This is a powerful and flexible tool for online examinations and grading. It is cloud-based and free. It has the feature of creating question bank and autograding. It is easier in generating portable reports in different formats and is secured with SSL encryption technology.

Tabular comparison of online examination tools

Tool | Cost | Cost | Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|

TCexam | Free | Does not require additional hardware to run | Feasible to organizations with well-trained system analyst that can be able to use the software in accordance to their requirement |

Virtualx | Free | Already on cloud, hosting is not required | This is cloud-based and makes it more portable and flexible but required a professional system analyst for the security of the information on the cloud |

Moodle | Free | Very integrated and it operates according to the class size | This is very okay for a class less population; it operates according to class size |

FlexiQuiz | FREE | Autograding and secured with SSL encryption | This is an automated software that is flexible according to user requirement, and it is secured with SSL encryption |

EdBase | Free | Creates question bank and cloud-based | This is a special package for computer-based examinations, and it has an autograding software, and it is free |

Challenges of Online Classes

Nowadays, smart KMS (Knowledge Management Systems) and LMS (Learning Management Systems) with technology inbuilt are in demand for increasing the need of self directness. Evidence have shown that students tend to understand better if multimedia (Adnan, 2018 ) tools are integrated into their teaching. Despite efforts by institutions to adapt the use of internet and ICT in teaching, most especially in the present condition of lockdowns, certain challenges are curtailing these efforts. Viz;

Lack of internet in most developing countries, like Africa: this proposed framework is purely online, and as such, reliable internet network is the backbone of its emergence. Most developing countries like Africa do not have sufficient internet network for their citizens, and this is a major setback for e-learning.

Security: The major challenge of anything online is security. This is because of the fair of cyber-attacks by hackers. Such a proposed framework will be handling students’ records and examination results. Any possible breach of access can result to serious information mismanagement. Hence, the need to put a serious security in place.

Lack of infrastructures like computers and ICT gadgets due to the level of poverty in some regions like Africa: for a successful online classroom, there must be resources to be sufficiently made available. These resources include network hardware, system hardware/software, and human resources, but due to economic factors of some countries, such provisions are relatively impossible and thus, a big challenge for e-learning.

Lack of power supply in many regions, like Africa: there cannot be technology without electricity and the issue of electricity is a regional challenge to Africans. Most universities in Nigeria were operating strictly on generators because there is no sufficient power supply. This makes it impossible for the students to gain access online as expected because they may not have the means of power supply while out of campus.

Lack of political will due to corruption in Africa: democracy is now a global rule of law. Though, every region or Country has its way of politics; in Africa corruption has pose major challenge in the development of the region and this makes it unfavourable for developmental trends like; ICT, Power etc.

Lack of scalable policies by government: In some countries, there are strict policies on the use of ICT; this might be due to the prevailing cybercrimes over the cyberspace and the process of adhering to such policies; it poses a great challenge in the development of educational technologies and other ICT-related platforms.

Lack of ICT knowledge/awareness among students and lecturers: In some countries and institutions, the knowledge of ICT is very scarce. In fact, some are resisting to accept technology as a modern science. They view the concept of ICT as an attempt to scam and hence, posing a very big challenge in the implementation of any ICT framework to such categories of Institutions/people.

Advantages of Online Classes

Easily accessible: you can log in anywhere you are, so long as you are online and you are registered on the platform. Unlike the traditional classroom where you to be at a scheduled venue, to receive lectures physically.

Unlimited access to resources: Most online-learning platforms are connected to an unlimited number of e-libraries from various academic institutions. Once you have access, you will gain access to unlimited e-books, journals, etc.

Flexibility in learning: Online-learning platforms simplify the methods of teaching, in the sense that lecturers can leave offline materials and assignments and each student can log in at his/her free time to download and act accordingly.

Sharing of resources is easier: Resources are easily shared via emails or direct download from the platform. Students do not need to go for photocopies or any physical stress.

Academic collaborations are enhanced: With the use of online teaching platforms, students collaborate far more than physically been in class. Such collaborations will assist them in group research and efficient time management for academic attainments.

Very portable and comfortable: Students can log in at their comfort zones. You can be in bed and still connect to the class and situation where you have travelled or lost your computer; all you need to do is to fine another one, connect to the internet, and log in to your classroom to continue your classes.

Possible Solutions to the Challenges of Online Classes

Nowadays, smart KMS (Knowledge Management Systems) and LMS (Learning Management Systems) with technology inbuilt is in demand for increasing the need of self directness (Gibson et al., 2008 ). Below are some proposed solutions to the aforementioned challenges;

Reliable internet network: The government should provide internet networks across the country at a subsidize rate. It is recommended that students been given free access to the internet while other citizens should pay either monthly or annually as proposed.

Sufficient power supply: Government should make available electricity to its citizens at a subsidise rate. This will bring about Industrialisations and thus, providing job opportunities among graduates.

Fighting corruption: The government should establish strong institutions for fighting corruption. These institutions should be independent and should have members from European, African Union (EAU), United Nations (UN), and any other intentional agency that is capable of checkmating the international affairs of a country.

Flexible government policies: Government should make their policies very favourable to their citizens. Government should be reviewing their policies routinely to curtail the shortcomings in their policies.

Strong ICT awareness: Students and the teachers should be train on ICT trends. The immediate societies should also be given awareness on the positive impacts of ICT in their environments.

Methodology

The study area will conduct in India and other country. The study populations are all populations who are delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19. A total of 150 respondents were included.

Study Design

A cross-sectional study design would be carried out. Cross-sectional survey design is mainly used for the collection of information on and related socio-demographic factors at a given point in time to attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown. The learning design for this learning was a traverse sectional survey conducted using population based representative sample. Variables are collected for several sample units at the same points in time (one time shoot), just the data collected from the respondents directly in a particular time. Cross-sectional surveys are used to gather information (Brecht & Ogilby, 2008 ) on a population at a single point in time. An example of a cross-sectional survey would be a questionnaire that collects data on peoples’ experiences of a particular initiative or event.

Source of Data

Primary data were collected from a community-based, cross-sectional survey. Primary data collection is the process of gathering data through surveys, interviews, or experiments. A typical aims for this study for data collection was primary data is online surveys by conducting well-done questions in India for 150 respondents. Online surveys were effective and therefore require computational logic and branching technologies for exponentially more accurate survey data collection versus any other traditional means of surveying. They are straightforward in their implementation and take a minimum time of the respondents (150). The investment required for survey data collection using online surveys is also negligible in comparison to the other methods. The results are collected in real-time for researchers to analyse and decide corrective measures.

Sampling Techniques

It is an inspecting method during which the choice of individuals for an example relies upon the possibility of comfort, individual decision or intrigue. For this examination we utilized judgment sampling. During this case, the individual taking the example has immediate or backhanded power over which things are chosen for the example.

Study Variables

The variables measured in this learning are taken based on previous studies at the global and national level. Those factors considered during this examination are delegated as: reliant and logical factors. The outcome variable is for the study attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19, which is dichotomous. The response variable for each respondent is given by:

The independent variables are measured from structural questionnaires. In this learning, the possible determinant factors estimated to be a significant effect on are included as variables. Poor internet connection, source of info about COVID-19, awareness on COVID-19, recommends MOOC, satisfaction with online study, materials and information sent, enough sources of materials, presently enrolled course, and favourite online methods were included for this study.

Methods of Data Analysis

In this study, frequency distribution, cross-tabulation, and percentage were applied to see the prevalence of the dependent variable. Binary logistic regression was applied to identify the factors for the outcome variable.

Binary Logistic Regression

Binary logistic regression is a prognostic model that is fitted where there is a dichotomous-/binary-dependent variable like in this instance where the researcher is interested in whether there was positive or negative. Usually, the categories are coded as “0” and “1” as it results is a straightforward interpretation. Binary logistic regression is the sort of regression used in our study (attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19). The model is given by

\(ln\left(\frac{{\pi }_{i}}{1-{\pi }_{i}}\right)={\beta }_{0} + {\beta }_{1}{X}_{1i}+{{\beta }_{2}X}_{2i}+ \dots \dots ..{\beta }_{k}{X}_{ki}\dots \dots \dots \dots \dots \dots \dots \dots ..\) (1 \()\) .

\(\frac{{\pi }_{i}}{1-{\pi }_{i}}= exp\left({\beta }_{0} + {\beta }_{1}{X}_{1i}+{{\beta }_{2}X}_{2i}+ \dots \dots ..{\beta }_{k}{X}_{ki}\right)\) ……… (2).

where: \({\pi }_{i}\) is the probability of success, \(1-{\pi }_{i}\) is the probability of failure \(,{\beta }_{0}\) is the constant term, \(\beta\) the regression coefficients, and \({X}_{i}\) are the independent variables. Logistic regression quantifies the relationship between the dichotomous dependent variable and the predictors using odds ratios. Odds ratio is the probability that an event will occur divided by the probability that the event will not happen. In this study, the odds ratio is the probability that attitudes towards delivering of online classes being negative divided by the probability that the attitudes towards delivering of online classes being positive. Method of maximum likelihood estimation yields to estimate values for the unknown parameters which maximize the probability of obtaining the observed set of knowledge. For logistic regression, the model coefficients are estimated by the utmost likelihood method and therefore the likelihood equations are non-linear explicit function of unknown parameters. For statistical analysis SAS version 9.4 software will be used at 5% level of significance.

Results and Discussion

Socio-economic variables are categorical. For our study the dependent variable might be “positive” or “negative.” In this case we would carry out a binary logistic regression analysis.

Table 1 depicted that poor internet connection, awareness on COVID-19, enough sources of materials; recommends MOOC, favourite online methods, and satisfaction with online study are significant in the model. The positive parameter estimates indicated that there is a positive relationship between the dependent variable and associated independent variables whereas the negative coefficients parameters indicated that there is a negative relationship between a dependent variable and independent variables. Where, X 1 is poor internet connection (No), X 2 is favourite online methods(E-books), X 3 is favourite online methods(Videos), X 4 is enough sources of materials(Yes), X 5 is satisfaction with online study (Very satisfied), X 6 is satisfaction with online study(Satisfied), X 7 is recommends MOOC (No), and X 8 is awareness on COVID-19 (No). Fitted model is given by

The poor internet connection (lack of internet access) had statistically significant effect to the attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic. The odds ratio of the poor internet connection (no) equals exp (0.178) = 1.081(95% CI 1.320, 0.476) (adjusted for the other variables are constant); the results show that those students who had not good connection in the study area are 0.081 times more likely to be negative attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic compared with that of students who had good connection. Sufficient internet network for their students is a major problem setback for e-learning or online class. Without good way of connection with respect to internet, academic collaborations were not enhanced; without the use of online teaching platforms, students cannot collaborate far more than physically been in class. Such collaborations will not assist them in group research and efficient time management for academic attainments.

Awareness on COVID-19 had also statistically significant effect on delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic. This implies that will help to locate out the data and information gaps among the students regarding the COVID-19 and the misconceptions and credulous beliefs popular in the society about it. It will also provide expressive data which may be useful for the concerned authority and planning institutions that prepare plans of programs to tackle the COVID-19 disease. Students who had awareness about COVID-19 pandemic odds ratio = exp (− 0.303) = 0.739 (95% CI 0.634, 0.861) times less likely to be negative attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic compared students who had not awareness about COVID-19 pandemic.

Many of such platforms are readily available online; it is left for organizations to analyse the available systems and choose the best that suits their requirements considering the online methods of learning and teaching. Even though, favourite online methods had an important factor for attitudes towards delivering. The odds ratio of the favourite online methods exp (0.830) = 2.293 and exp (0.585) = 1.795 for e-books and videos respectively (adjusted other variables). This implies students whose favourite online methods e-books = 2.293 (95% CI 1.421, 3.701) times more likely to be negative attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic compared all. Although students whose favourite videos, online methods of learning = 1.795 times more likely to be negative attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic compared all. Overall, e-books and videos significantly affect than all on attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown.

The key objective of the study is to assess the socio-demographic and related factors on the attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic in India. Primary data were collected from a community-based, cross-sectional survey. Just the data collected from the respondents directly in a particular time. For this examination we utilized judgment sampling. We have used a sample of 150 participants. Accordingly, descriptive analysis (frequency distribution, cross-tabulation, and percentage) and binary logistic regression were used. Binary logistic regression was found to be the model that could be applied for the study to such a variable as the dependent could meet the assumptions that should be satisfied for methods to be fitted. The backward stepwise logistic regression started with a model with all the variables and excluded the variables with insignificant coefficients until the model was at its best predictive power. As a result of binary logistic regression, poor internet connection, awareness on COVID-19, enough sources of materials, recommends MOOC, favourite online methods, and satisfaction with online study are significant in the model or attitudes towards delivering of online classes during lockdown COVID-19 pandemic at 5% level of significance. The analysis of the significance of the logistic coefficients was done using likelihood ratio and Wald test. The model was considered to be valid since both the model fitting and the validation sample produced almost the same classification accuracy.

Change history

12 may 2021.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-021-00196-0

Adnan, M. (2018). Professional development in the transition to online teaching: the voice of entrant online instructors. ReCALL, 30 (1), 88–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344017000106 .

Article Google Scholar

Arbaugh, J. B., Godfrey, M. R., Johnson, M., Pollack, B. L., Niendorf, B., & Wresch, W. (2009). Research in online and blended learning in the business disciplines: key findings and possible future directions. Internet and Higher Education, 12, 71–87

Beatty, B., & Ulasewicz, C. (2006). Faculty perception on movingfrom blackboard to the Moodle learning management system, TechTrends: Linking Research and Practice to Improve Learning, 50 (4), 36-45

Brecht, H., & Ogilby, S. M. (2008). Enabling a comprehensive teaching strategy: video lectures. Journal of Information Technology Education, 7 , IIP71-IIP86. Retrieved from https://www.jite.org/documents/Vol7/JITEV7IIP071-086Brecht371.pdf .

Gibson, S., Harris, M., & Colaric, S. (2008). Technology acceptance in an academic context: faculty acceptance of online education. Journal of Education for Business, 83 (6), 355–359

Grant, D. M., Malloy, A. D., & Murphy, M. C. (2009). A comparison of student perceptions of their computer skills and their actual abilities. Journal of Information Technology Education: 8 , 141–160. Retrieved from https://www.jite.org/documents/Vol8/JITEv8p141-160Grant428.pdf .

Kibaru, F. (2018).Supporting faculty to face challenges in design and delivery of quality courses in virtual learning environments. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 19 (4), 176–197. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.471915 .

Knight, S. A. & Halkett, G. K. B. (2010). Living systems, complexity & information systems science. Paper presented at the Australasian Conference in Information Systems (ACIS-2010), Brisbane, Australia

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking University Teaching . London: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315012940 .

Moore, M., & Kearsley, G. (2012). Distance education: A systems view of online learning . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Google Scholar

Pfahl, D., Angkasaputra, N., Differding, C., & Ruhe, G. (2001): CORONET-Train: A methodology for web-based collaborative learning in software Organizations. In: Althoff, K.-D., Feldmann, R.L., & Müller, W. (eds.) LSO 2001. LNCS, vol. 2176, p. 37. Springer, Heidelberg

Rabe-Hemp, C., Woollen, S., & Humiston, G. (2009).A comparative analysis of student engagement, learning, and satisfaction in lecture hall and online learning settings. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 10 (2), 207–218

Saadé, G. R., & Kira, D. (2009). The e-motional factor of e-learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 13 (4), 57-72

Shen, D., Laffey, J., Lin, Y. & Huang, X. (2006). Social influence for perceived usefulness and ease-of-use of course delivery systems. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, vol. 5, No. 3 , Winter. Retrieved [May 12, 2010] from https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/PDF/5.3.4.pdf . In press

Shroff, R., & Vogel, D. (2009). Assessing the factors deemed to support individual student Intrinsic motivation in technology supported onlineand face-to-face discussions. Retrieved 7 December 2020, from https://doi.org/10.28945/160 .

Singh, A., Mangalaraj, G., & Taneja, A. (2010). "Bolstering teaching through online tools," Journal of Information Systems Education: Vol. 21 : Iss. 3 , 299-312. Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/jise/vol21/iss3/4

Smart, K.L. & Cappel, J.J. (2006). Students’ perceptions of online learning: A comparative study. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 5 (1), 201-219. Informing Science Institute. Retrieved December 7, 2020 from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/111541/ .

Unal, Z., & Unal, A. (2011). Evaluating and comparing the usability of web-based course management systems. Journal Of Information Technology Education: Research, 10, 019-038. https://doi.org/10.28945/1358 .

Wang, Y., Li, X. & Gu, R. (2004). Web-Based Adaptive Collaborative Learning Environment Designing, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, LNCS 3143, 163168

Zhang, X., Luo, N., Jiang, D. X., Liu, H., & Zhang, W. (2004). Web-based collaborative learning focused on the Study of Interaction and Human Communication. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, LNCS, 3143, 113–119

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Technical Education, IET, Dr A.P.J Abdul Kalam Technical University, Lucknow, India

Digvijay Pandey

Faculty of Management, Sharda University, Andijan, Uzbekistan

Gabriel A. Ogunmola

Department of Statistics, Mizan-Tepi University, Tepi, Ethiopia

Wegayehu Enbeyle

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Sule Lamido University, Jigawa State, Kafin Hausa, Nigeria

Marzuk Abdullahi

Department of IT, COT, Govind Ballabh Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Uttarakhand, Pantnagar, India

Binay Kumar Pandey

Haldia Institute of Technology, Haldia, India

Sabyasachi Pramanik

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Digvijay Pandey .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article unfortunately contained mistake. The affiliation address of Wegayehu Enbeyle should be changed to Department of Statistics, Mizan-Tepi University, Tepi, Ethiopia

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Pandey, D., Ogunmola, G.A., Enbeyle, W. et al. COVID-19: A Framework for Effective Delivering of Online Classes During Lockdown. Hu Arenas 5 , 322–336 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00175-x

Download citation

Received : 28 September 2020

Revised : 25 November 2020

Accepted : 01 December 2020

Published : 30 January 2021

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-020-00175-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- E-learning tools

- Online learning

- Binary logistic regression

Advertisement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 27 September 2021

Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap

- Sébastien Goudeau ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7293-0977 1 ,

- Camille Sanrey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3158-1306 1 ,

- Arnaud Stanczak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2596-1516 2 ,

- Antony Manstead ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7540-2096 3 &

- Céline Darnon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2613-689X 2

Nature Human Behaviour volume 5 , pages 1273–1281 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

117k Accesses

162 Citations

128 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced teachers and parents to quickly adapt to a new educational context: distance learning. Teachers developed online academic material while parents taught the exercises and lessons provided by teachers to their children at home. Considering that the use of digital tools in education has dramatically increased during this crisis, and it is set to continue, there is a pressing need to understand the impact of distance learning. Taking a multidisciplinary view, we argue that by making the learning process rely more than ever on families, rather than on teachers, and by getting students to work predominantly via digital resources, school closures exacerbate social class academic disparities. To address this burning issue, we propose an agenda for future research and outline recommendations to help parents, teachers and policymakers to limit the impact of the lockdown on social-class-based academic inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Uncovering Covid-19, distance learning, and educational inequality in rural areas of Pakistan and China: a situational analysis method

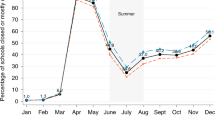

The widespread effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that emerged in 2019–2020 have drastically increased health, social and economic inequalities 1 , 2 . For more than 900 million learners around the world, the pandemic led to the closure of schools and universities 3 . This exceptional situation forced teachers, parents and students to quickly adapt to a new educational context: distance learning. Teachers had to develop online academic materials that could be used at home to ensure educational continuity while ensuring the necessary physical distancing. Primary and secondary school students suddenly had to work with various kinds of support, which were usually provided online by their teachers. For college students, lockdown often entailed returning to their hometowns while staying connected with their teachers and classmates via video conferences, email and other digital tools. Despite the best efforts of educational institutions, parents and teachers to keep all children and students engaged in learning activities, ensuring educational continuity during school closure—something that is difficult for everyone—may pose unique material and psychological challenges for working-class families and students.

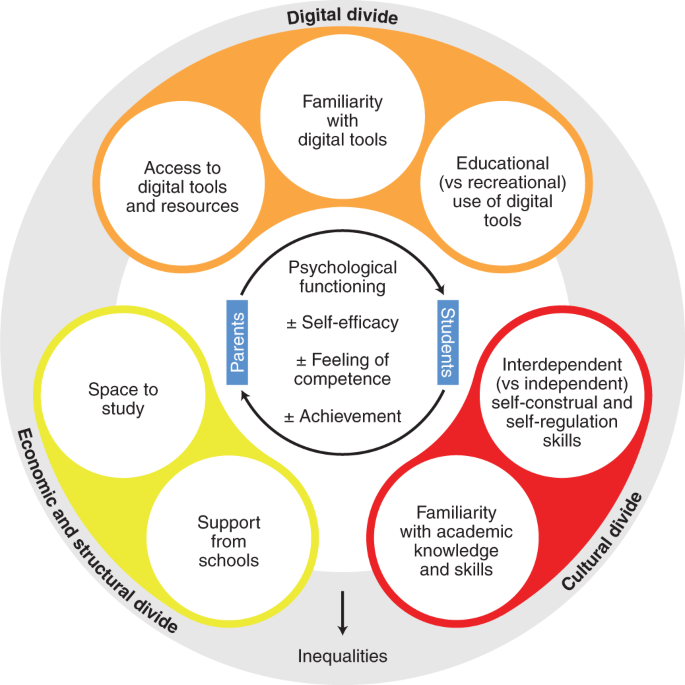

Not only did the pandemic lead to the closure of schools in many countries, often for several weeks, it also accelerated the digitalization of education and amplified the role of parental involvement in supporting the schoolwork of their children. Thus, beyond the specific circumstances of the COVID-19 lockdown, we believe that studying the effects of the pandemic on academic inequalities provides a way to more broadly examine the consequences of school closure and related effects (for example, digitalization of education) on social class inequalities. Indeed, bearing in mind that (1) the risk of further pandemics is higher than ever (that is, we are in a ‘pandemic era’ 4 , 5 ) and (2) beyond pandemics, the use of digital tools in education (and therefore the influence of parental involvement) has dramatically increased during this crisis, and is set to continue, there is a pressing need for an integrative and comprehensive model that examines the consequences of distance learning. Here, we propose such an integrative model that helps us to understand the extent to which the school closures associated with the pandemic amplify economic, digital and cultural divides that in turn affect the psychological functioning of parents, students and teachers in a way that amplifies academic inequalities. Bringing together research in social sciences, ranging from economics and sociology to social, cultural, cognitive and educational psychology, we argue that by getting students to work predominantly via digital resources rather than direct interactions with their teachers, and by making the learning process rely more than ever on families rather than teachers, school closures exacerbate social class academic disparities.

First, we review research showing that social class is associated with unequal access to digital tools, unequal familiarity with digital skills and unequal uses of such tools for learning purposes 6 , 7 . We then review research documenting how unequal familiarity with school culture, knowledge and skills can also contribute to the accentuation of academic inequalities 8 , 9 . Next, we present the results of surveys conducted during the 2020 lockdown showing that the quality and quantity of pedagogical support received from schools varied according to the social class of families (for examples, see refs. 10 , 11 , 12 ). We then argue that these digital, cultural and structural divides represent barriers to the ability of parents to provide appropriate support for children during distance learning (Fig. 1 ). These divides also alter the levels of self-efficacy of parents and children, thereby affecting their engagement in learning activities 13 , 14 . In the final section, we review preliminary evidence for the hypothesis that distance learning widens the social class achievement gap and we propose an agenda for future research. In addition, we outline recommendations that should help parents, teachers and policymakers to use social science research to limit the impact of school closure and distance learning on the social class achievement gap.

Economic, structural, digital and cultural divides influence the psychological functioning of parents and students in a way that amplify inequalities.

The digital divide

Unequal access to digital resources.

Although the use of digital technologies is almost ubiquitous in developed nations, there is a digital divide such that some people are more likely than others to be numerically excluded 15 (Fig. 1 ). Social class is a strong predictor of digital disparities, including the quality of hardware, software and Internet access 16 , 17 , 18 . For example, in 2019, in France, around 1 in 5 working-class families did not have personal access to the Internet compared with less than 1 in 20 of the most privileged families 19 . Similarly, in 2020, in the United Kingdom, 20% of children who were eligible for free school meals did not have access to a computer at home compared with 7% of other children 20 . In 2021, in the United States, 41% of working-class families do not own a laptop or desktop computer and 43% do not have broadband compared with 8% and 7%, respectively, of upper/middle-class Americans 21 . A similar digital gap is also evident between lower-income and higher-income countries 22 .

Second, simply having access to a computer and an Internet connection does not ensure effective distance learning. For example, many of the educational resources sent by teachers need to be printed, thereby requiring access to printers. Moreover, distance learning is more difficult in households with only one shared computer compared with those where each family member has their own 23 . Furthermore, upper/middle-class families are more likely to be able to guarantee a suitable workspace for each child than their working-class counterparts 24 .

In the context of school closures, such disparities are likely to have important consequences for educational continuity. In line with this idea, a survey of approximately 4,000 parents in the United Kingdom confirmed that during lockdown, more than half of primary school children from the poorest families did not have access to their own study space and were less well equipped for distance learning than higher-income families 10 . Similarly, a survey of around 1,300 parents in the Netherlands found that during lockdown, children from working-class families had fewer computers at home and less room to study than upper/middle-class children 11 .

Data from non-Western countries highlight a more general digital divide, showing that developing countries have poorer access to digital equipment. For example, in India in 2018, only 10.7% of households possessed a digital device 25 , while in Pakistan in 2020, 31% of higher-education teachers did not have Internet access and 68.4% did not have a laptop 26 . In general, developing countries lack access to digital technologies 27 , 28 , and these difficulties of access are even greater in rural areas (for example, see ref. 29 ). Consequently, school closures have huge repercussions for the continuity of learning in these countries. For example, in India in 2018, only 11% of the rural and 40% of the urban population above 14 years old could use a computer and access the Internet 25 . Time spent on education during school closure decreased by 80% in Bangladesh 30 . A similar trend was observed in other countries 31 , with only 22% of children engaging in remote learning in Kenya 32 and 50% in Burkina Faso 33 . In Ghana, 26–32% of children spent no time at all on learning during the pandemic 34 . Beyond the overall digital divide, social class disparities are also evident in developing countries, with lower access to digital resources among households in which parental educational levels were low (versus households in which parental educational levels were high; for example, see ref. 35 for Nigeria and ref. 31 for Ecuador).

Unequal digital skills

In addition to unequal access to digital tools, there are also systematic variations in digital skills 36 , 37 (Fig. 1 ). Upper/middle-class families are more familiar with digital tools and resources and are therefore more likely to have the digital skills needed for distance learning 38 , 39 , 40 . These digital skills are particularly useful during school closures, both for students and for parents, for organizing, retrieving and correctly using the resources provided by the teachers (for example, sending or receiving documents by email, printing documents or using word processors).

Social class disparities in digital skills can be explained in part by the fact that children from upper/middle-class families have the opportunity to develop digital skills earlier than working-class families 41 . In member countries of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), only 23% of working-class children had started using a computer at the age of 6 years or earlier compared with 43% of upper/middle-class children 42 . Moreover, because working-class people tend to persist less than upper/middle-class people when confronted with digital difficulties 23 , the use of digital tools and resources for distance learning may interfere with the ability of parents to help children with their schoolwork.

Unequal use of digital tools

A third level of digital divide concerns variations in digital tool use 18 , 43 (Fig. 1 ). Upper/middle-class families are more likely to use digital resources for work and education 6 , 41 , 44 , whereas working-class families are more likely to use these resources for entertainment, such as electronic games or social media 6 , 45 . This divide is also observed among students, whereby working-class students tend to use digital technologies for leisure activities, whereas their upper/middle-class peers are more likely to use them for academic activities 46 and to consider that computers and the Internet provide an opportunity for education and training 23 . Furthermore, working-class families appear to regulate the digital practices of their children less 47 and are more likely to allow screens in the bedrooms of children and teenagers without setting limits on times or practices 48 .

In sum, inequalities in terms of digital resources, skills and use have strong implications for distance learning. This is because they make working-class students and parents particularly vulnerable when learning relies on extensive use of digital devices rather than on face-to-face interaction with teachers.

The cultural divide

Even if all three levels of digital divide were closed, upper/middle-class families would still be better prepared than working-class families to ensure educational continuity for their children. Upper/middle-class families are more familiar with the academic knowledge and skills that are expected and valued in educational settings, as well as with the independent, autonomous way of learning that is valued in the school culture and becomes even more important during school closure (Fig. 1 ).

Unequal familiarity with academic knowledge and skills

According to classical social reproduction theory 8 , 49 , school is not a neutral place in which all forms of language and knowledge are equally valued. Academic contexts expect and value culture-specific and taken-for-granted forms of knowledge, skills and ways of being, thinking and speaking that are more in tune with those developed through upper/middle-class socialization (that is, ‘cultural capital’ 8 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ). For instance, academic contexts value interest in the arts, museums and literature 54 , 55 , a type of interest that is more likely to develop through socialization in upper/middle-class families than in working-class socialization 54 , 56 . Indeed, upper/middle-class parents are more likely than working-class parents to engage in activities that develop this cultural capital. For example, they possess more books and cultural objects at home, read more stories to their children and visit museums and libraries more often (for examples, see refs. 51 , 54 , 55 ). Upper/middle-class children are also more involved in extra-curricular activities (for example, playing a musical instrument) than working-class children 55 , 56 , 57 .

Beyond this implicit familiarization with the school curriculum, upper/middle-class parents more often organize educational activities that are explicitly designed to develop academic skills of their children 57 , 58 , 59 . For example, they are more likely to monitor and re-explain lessons or use games and textbooks to develop and reinforce academic skills (for example, labelling numbers, letters or colours 57 , 60 ). Upper/middle-class parents also provide higher levels of support and spend more time helping children with homework than working-class parents (for examples, see refs. 61 , 62 ). Thus, even if all parents are committed to the academic success of their children, working-class parents have fewer chances to provide the help that children need to complete homework 63 , and homework is more beneficial for children from upper-middle class families than for children from working-class families 64 , 65 .

School closures amplify the impact of cultural inequalities

The trends described above have been observed in ‘normal’ times when schools are open. School closures, by making learning rely more strongly on practices implemented at home (rather than at school), are likely to amplify the impact of these disparities. Consistent with this idea, research has shown that the social class achievement gap usually greatly widens during school breaks—a phenomenon described as ‘summer learning loss’ or ‘summer setback’ 66 , 67 , 68 . During holidays, the learning by children tends to decline, and this is particularly pronounced in children from working-class families. Consequently, the social class achievement gap grows more rapidly during the summer months than it does in the rest of the year. This phenomenon is partly explained by the fact that during the break from school, social class disparities in investment in activities that are beneficial for academic achievement (for example, reading, travelling to a foreign country or museum visits) are more pronounced.

Therefore, when they are out of school, children from upper/middle-class backgrounds may continue to develop academic skills unlike their working-class counterparts, who may stagnate or even regress. Research also indicates that learning loss during school breaks tends to be cumulative 66 . Thus, repeated episodes of school closure are likely to have profound consequences for the social class achievement gap. Consistent with the idea that school closures could lead to similar processes as those identified during summer breaks, a recent survey indicated that during the COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom, children from upper/middle-class families spent more time on educational activities (5.8 h per day) than those from working-class families (4.5 h per day) 7 , 69 .

Unequal dispositions for autonomy and self-regulation

School closures have encouraged autonomous work among students. This ‘independent’ way of studying is compatible with the family socialization of upper/middle-class students, but does not match the interdependent norms more commonly associated with working-class contexts 9 . Upper/middle-class contexts tend to promote cultural norms of independence whereby individuals perceive themselves as autonomous actors, independent of other individuals and of the social context, able to pursue their own goals 70 . For example, upper/middle-class parents tend to invite children to express their interests, preferences and opinions during the various activities of everyday life 54 , 55 . Conversely, in working-class contexts characterized by low economic resources and where life is more uncertain, individuals tend to perceive themselves as interdependent, connected to others and members of social groups 53 , 70 , 71 . This interdependent self-construal fits less well with the independent culture of academic contexts. This cultural mismatch between interdependent self-construal common in working-class students and the independent norms of the educational institution has negative consequences for academic performance 9 .

Once again, the impact of these differences is likely to be amplified during school closures, when being able to work alone and autonomously is especially useful. The requirement to work alone is more likely to match the independent self-construal of upper/middle-class students than the interdependent self-construal of working-class students. In the case of working-class students, this mismatch is likely to increase their difficulties in working alone at home. Supporting our argument, recent research has shown that working-class students tend to underachieve in contexts where students work individually compared with contexts where students work with others 72 . Similarly, during school closures, high self-regulation skills (for example, setting goals, selecting appropriate learning strategies and maintaining motivation 73 ) are required to maintain study activities and are likely to be especially useful for using digital resources efficiently. Research has shown that students from working-class backgrounds typically develop their self-regulation skills to a lesser extent than those from upper/middle-class backgrounds 74 , 75 , 76 .

Interestingly, some authors have suggested that independent (versus interdependent) self-construal may also affect communication with teachers 77 . Indeed, in the context of distance learning, working-class families are less likely to respond to the communication of teachers because their ‘interdependent’ self leads them to respect hierarchies, and thus perceive teachers as an expert who ‘can be trusted to make the right decisions for learning’. Upper/middle class families, relying on ‘independent’ self-construal, are more inclined to seek individualized feedback, and therefore tend to participate to a greater extent in exchanges with teachers. Such cultural differences are important because they can also contribute to the difficulties encountered by working-class families.

The structural divide: unequal support from schools

The issues reviewed thus far all increase the vulnerability of children and students from underprivileged backgrounds when schools are closed. To offset these disadvantages, it might be expected that the school should increase its support by providing additional resources for working-class students. However, recent data suggest that differences in the material and human resources invested in providing educational support for children during periods of school closure were—paradoxically—in favour of upper/middle-class students (Fig. 1 ). In England, for example, upper/middle-class parents reported benefiting from online classes and video-conferencing with teachers more often than working-class parents 10 . Furthermore, active help from school (for example, online teaching, private tutoring or chats with teachers) occurred more frequently in the richest households (64% of the richest households declared having received help from school) than in the poorest households (47%). Another survey found that in the United Kingdom, upper/middle-class children were more likely to take online lessons every day (30%) than working-class students (16%) 12 . This substantial difference might be due, at least in part, to the fact that private schools are better equipped in terms of online platforms (60% of schools have at least one online platform) than state schools (37%, and 23% in the most deprived schools) and were more likely to organize daily online lessons. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, in schools with a high proportion of students eligible for free school meals, teachers were less inclined to broadcast an online lesson for their pupils 78 . Interestingly, 58% of teachers in the wealthiest areas reported having messaged their students or their students’ parents during lockdown compared with 47% in the most deprived schools. In addition, the probability of children receiving technical support from the school (for example, by providing pupils with laptops or other devices) is, surprisingly, higher in the most advantaged schools than in the most deprived 78 .

In addition to social class disparities, there has been less support from schools for African-American and Latinx students. During school closures in the United States, 40% of African-American students and 30% of Latinx students received no online teaching compared with 10% of white students 79 . Another source of inequality is that the probability of school closure was correlated with social class and race. In the United States, for example, school closures from September to December 2020 were more common in schools with a high proportion of racial/ethnic minority students, who experience homelessness and are eligible for free/discounted school meals 80 .

Similarly, access to educational resources and support was lower in poorer (compared with richer) countries 81 . In sub-Saharan Africa, during lockdown, 45% of children had no exposure at all to any type of remote learning. Of those who did, the medium was mostly radio, television or paper rather than digital. In African countries, at most 10% of children received some material through the Internet. In Latin America, 90% of children received some remote learning, but less than half of that was through the internet—the remainder being via radio and television 81 . In Ecuador, high-school students from the lowest wealth quartile had fewer remote-learning opportunities, such as Google class/Zoom, than students from the highest wealth quartile 31 .