An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Educ Health Promot

Online classes versus traditional classes? Comparison during COVID-19

Sanjana kumari.

Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Hitender Gautam

Neha nityadarshini, bimal kumar das, rama chaudhry, background:.

Nowadays, the use of Internet with e-learning resources anytime and anywhere leads to interaction possibilities among teachers and students from different parts of the world. It is becoming increasingly pertinent that we exploit the Internet technologies to achieve the most benefits in the education.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This study compares the difference between traditional classroom and e-learning in the educational environment. Medical undergraduate students of our institution were enrolled to compare between the online versus traditional method of teaching through questionnaire.

Forty percent of students found the online lecture material difficult to understand. 42.6% of respondents found it difficult to clear the doubts in online teaching; 64.4% of the participants believed that they have learned more in a face-to-face learning.

CONCLUSION:

In this study, we concluded that online mode offers flexibility on timing and delivery. Students can even download the content, notes, and assignment. Despite all the advantages offered, there is a general consensus that no technology can replace face-to-face teaching in real because in this, there will be visual as well as verbal discussion. Looking at the uncertainty of the current scenario, it is difficult to predict how long online classes will have to continue. Hence, it is of paramount importance that we assess the effectiveness of online classes and consequently take measures to ensure proper delivery of content to students, especially in a skilled field like medicine, so we concluded that face-to-face learning is of utmost importance in medical institutions.

Introduction

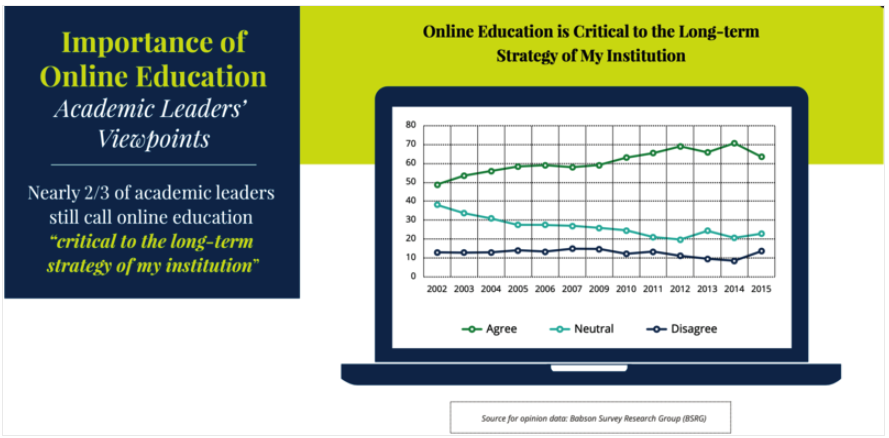

In these current times of information technology, students in higher education depend on a computer to do most of the work. Most higher educational institutions are also aware that using network technology can create, foster, deliver, and facilitate learning and enhance students’ experience and knowledge. Hence, the rapid developments and growth of information and communication technology have had a profound influence on higher education. E-learning means that teachers and students perform and complete the task through Internet, a method that is relatively different from traditional classroom.[ 1 ] According to a report published in 2011, over 6.1 million students were taking at least one or more online courses in 2010, with 31% of all students involved in higher education being taking at least one online course. In a more recent report, the number had increased by approximately 570,000 for a total of million students taking at least one or more online course. The report further shows and predicts that the number of students taking at least one online course is at its highest level, with the current growth rate of 9.3%, and shows no evidence of the trend slowing in the foreseeable future.[ 2 ] This trend has left many questions that need to be answered regarding what factors are driving this shift and how this shift will ultimately affect institutions across the country.

The history of online learning is particularly interesting because it not only shows the contributions of individuals but also institutions to the advancement of education and the sharing of that knowledge and skills on a global scale. As we briefly review the historical development of this subject, it is important to indicate that many authors use the terms “distance learning,” “distance education,” “online learning,” and “online education” interchangeably,[ 3 ] as is the case in this paper.

Online courses are courses where at least 80% of the content is delivered online without face-to-face meetings, whereas face-to-face instructions are a learning method where all content is delivered only in a traditional face-to-face setting.

Hybrid courses, on the other hand, combine the benefits of face-to-face learning with the technology often used in online courses. 30%–79% of the course is delivered online.

Web-facilitated courses are the ones where 1%–29% of the course is delivered online. Although this type of course is actually a face-to-face course, it uses a web-based technology to supplement the face-to-face instruction provided to students.

This study is to compare the effectiveness of a medical undergraduate, online microbiology course to a traditional in-class lecture course taught by the same instructor as measured by response to the pre-formed questionnaire.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting.

It was a prospective study. Study participants were provided with a questionnaire to do comparison between the online versus traditional method of education. Due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, traditional classroom teaching was shifted to online teaching. In traditional classroom setting, lecture duration ranged typically from 45 min to 1 h, with few minutes dedicated for doubt clearing or discussion at the end. Course content was delivered by the faculty verbally, assisted by projected PowerPoint presentations. In contrast to this, course content in online mode was delivered through streaming/video-conferencing software. Students could access it through their electronic devices: phones, tablets, and laptops via a link. The content for both educational modes—online and traditional classroom-based—was identical as it was taught by the same teaching faculty. Duration of lectures remained the same as well.

Study participants and sampling

Medical undergraduate students at the Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India, were the study participants. Students were the same for both modes of teaching. Out of a total strength of 101, 75 students participated.

Data collection tool and technique

A questionnaire was designed covering questions such as whether online classes provide better understanding of course content, is it easier to pay attention to lectures in online classes, whether online classes are convenient to attend, is it easier to clear doubts through online discussions, do the students face technical issues during online classes, are the students more likely to attend online classes than traditional classes, is it easier to get distracted during online classes than during traditional classes, are the students more likely to stick to the time table of traditional classes as compared to online classes, do the students miss social interaction with peers and teachers in case of online classes, and do lack of face to face communication makes online classes less engaging.

Printed copies of the questionnaire covering all the questions were provided to all students, and a filled questionnaire was collected from all participating students. All the participant students were requested to fill the questionnaire individually. Response to all the questions from all participant students was entered in Microsoft Excel and analyzed. Active intervention was not attempted in the study, before COVID-19 pandemic traditional classroom teaching was the method of teaching which was changed to online teaching due to restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethical considerations

Consent was taken from all students who participated in the study. Ethical consideration was not required as no active change in teaching modality was there due to the study.

Participants in this study were medical undergraduate students; the questionnaire was sent to a total of 101 students. A total of 75 students participated; female (26.6%) and male (73.3%) were in the age group of 18 and 30 years. We aimed to evaluate students about their perceptions regarding ease or difficulty of online lecture materials, assignments, and online navigation.

Questionnaires were made regarding the students’ concern about understanding of course content, attention scale, convenience, doubts in class, technical issue, distraction during the class, and clarification of the doubts.

Survey reported that 25.3% of students found that online lecture material was satisfactory and easy to understand, while over 40% of students found the lecture material difficult to understand. 42.6% of students found that online assignments were difficult to clear the doubts, while 45.3% found difficulty in attention span during the online classes. Similarly, 64% reported difficulty in the discussion in online classes with the teachers and understanding the course, as shown in Table 1 . The findings further indicate students’ perceptions about the material are viewed as being rigorous even despite the ease of navigation. No comparative analysis was done between the rigor for face-to-face classes and online offerings. However, students perceived a difference between the amounts learned in the two modes even though course content was equivalent.

Questionnaire-based response from students

| Questions | Strongly agree, (%) | Agree, (%) | Neutral, (%) | Disagree, (%) | Strongly disagree, (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding | 6 (8) | 13 (17) | 26 (34) | 25 (33) | 5 (6) |

| Attention | 11 (14) | 16 (21) | 14 (18) | 21 (28) | 13 (17) |

| Convenience | 34 (45) | 32 (42) | 3 (4) | 4 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Doubts | 5 (6) | 9 (12) | 24 (32) | 30 (40) | 7 (9) |

| Technical issues* | |||||

| Attendance* | |||||

| Distracted | 18 (24) | 23 (30) | 16 (21) | 12 (16) | 6 (8) |

| Regularity | 21 (28) | 28 (37) | 14 (17) | 6 (8) | 7 (9) |

| Interaction | 19 (25) | 34 (45) | 9 (12) | 7 (9) | 6 (8) |

| Engaging | 13 (17) | 35 (46) | 9 (12) | 11 (14) | 7 (9) |

*Subjective answer mentioned in results. Total number of participants n =75

In academic environments, course organization and presentation are key factors that can either attract or distract students. Students need clarity and relevance in the materials presented to them. 24% of the participants agreed that the online courses were well presented and organized. On the other hand, 64.4% of the participants believe they have learned more in a face-to-face learning environment than in an online setting. Online learning is not always a seamless experience for students. Users encounter many problems including Internet interruption, system upgrade downtime, and instruction and organization to unreliable Internet connection.

Within the last 20 years, the components of learning via computers have challenged the view that the traditional lecture is necessarily the most appropriate means of facilitating learning in a university environment. People found that e-learning has its own advantages on learning outcomes through researches on comparison research about differences between e-learning and traditional classroom.

Over the past decades, most institutions have expanded the list of courses being offered online, and a growing number of students favor online courses over traditional face-to-face courses. This is due in part to the flexibility that online courses provide, the convenience, and a host of other factors. Respondents in this study indicated that offering more online courses would not be that helpful. Some of the students perceived their online experience as being positive despite multiple problems in the online courses, including lack of understanding of the content of materials, limited access, and poor technological infrastructure. In addition, the majority of students found the lecture materials and assignments difficult to understand. These findings suggest that institutions need to address their students’ desire for more flexible, technology-oriented educational platforms and to exert greater efforts to eliminate obstacles that might hinder the smooth utilization of these technologies.

In our study, the responders faced many difficulties. There should be orientation session for teachers and students on how to adapt to online classes and make learning fun and effective through classes before beginning online sessions for students. To ensure discipline is maintained in class, many educational institutions have issued e-classroom etiquette. It includes being properly dressed, being seated at a desk, and no interruptions from parents during the class. Classroom can be split into multiple batches so that it is easier to keep track of students in a session.

A study by Alsaaty et al. [ 3 ] compared and found out online experience as being positive despite multiple problems in the online courses. Thomas et al. [ 4 ] conducted a similar study where he compared students and found out Internet-based course showed higher performance of students on class-based course. Chen et al. [ 5 ] conducted another study where student perceptions in a MBA accounting concluded that the traditional classrooms would continue to offer benefits that cannot fully be obtained in any other manner. However, gaps in process effectiveness will continue to be narrowed as technology becomes friendlier for both instructor and students.

Limitation and recommendation

Since this was a questionnaire-based study, possibility of the participants misinterpreting certain questions cannot be ignored. Response rate was about 75%. Although efforts were made to include open-ended questions, some questions were multiple-choice question based which could have limited the response of participants to few options. Future studies on this subject could use a face-to-face interview approach to get a better response rate and include more subjective and personalized responses of participants. In addition, there was only one time collection of data in this study. Further studies are needed to see if online classes can be an integral part of medical education, once the restrictions due to pandemic ease down.

One of the advantages the online mode offers is its flexibility in timing and delivery. They can even download the content, notes, and assignment. They can easily participate in discussion due to less anxiety and do group discussion and permanent record of feedback. Other advantages for students include not needing to commute. Despite all the advantages offered, there is a general consensus that no technology can replace traditional teaching in real because in this, there will be visual as well verbal discussion. Practical learning through in-hand training, demonstrations, and skill development, which of utmost importance in medical learning, is not possible through online teaching. Teachers might be less conversant and have apathy toward online teaching. It is difficult to keep track of student's attention. Doubt-clearing is hampered as well. Looking at the uncertainty of the current scenario, it is difficult to predict how long online classes will continue. Hence, it is of paramount importance that we assess the effectiveness of online classes and consequently take measures to ensure proper delivery of content to students, especially in a skilled field like medicine.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to the Academic Section of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India, for their support.

Conventional vs. Online Learning: Pros and Cons Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Education is crucial to growth as an individual, and choosing a learning approach that works for a person is important. Students often can choose between a traditional classroom setting and an online learning environment. The two approaches each have advantages and disadvantages in relation to student learning. In this article, the pros and cons of both conventional and online education will be examined from the perspectives of COVID-19, students’ mental health, and their professional and personal growth. Because of COVID-19, there has been a global trend toward providing education digitally. Students in a typical school setting get instruction from a teacher in a classroom setting. On the other hand, online learning is conducted, with students receiving and turning in their assignments in the same way. Schools and institutions have been shuttered due to the pandemic to contain the infection. However, nowadays, it is common practice for students to attend courses and take tests online.

Online distance education (ODE) has traditionally been provided favorably to students who reside in remote areas, allowing them to make the most efficient use of available educational resources. Universities in a growing number of nations have introduced ODE and made it available to their students in recent decades (He et al. 1). There are two types of ODE courses that may be provided: synchronous and asynchronous. Almost all online education tools, including Moodle, adhere to the asynchronous distance education model, which makes use of formats like recorded learning videos (He et al. 1). By synchronizing teaching and learning in real-time online settings like live web conferences and virtual classrooms, synchronous distance education attempts to mimic the communication patterns of conventional face-to-face classrooms (He et al. 1). These approaches to learning provide new experiences for students and develop self-paced comprehension.

The term traditional learning is used to describe the more common method of education in which students listen to a lecture given by an expert in the field. It has been around for centuries, and it is still extensively utilized as a kind of education in many places. In a classroom setting, a teacher would typically provide lessons to a class of pupils. Students are expected to learn from the instructor by paying attention, taking notes, and engaging in class discussions because of the teacher’s status as the subject matter expert. In most classroom settings, the instructor controls both the tempo and substance of the instruction.

The rise of online learning has significantly affected the psychological well-being of college students. Online learning has many advantages, but it may be difficult for students who need help maintaining self-discipline and drive (Al-Okaily et al. 846). The lack of face-to-face contact with professors and classmates might negatively impact students’ mental health. Traditional classrooms, on the other hand, encourage students to build relationships with their instructors and classmates, which may benefit their emotional well-being.

How students and teachers approach the online learning process is a major factor in the success of online education. As Halupa (cited in Akpınar) points out, there are many things that might divert students’ attention when they’re utilizing the internet as a learning resource. Student attitudes about online education have been generally unfavorable, despite the fact that it represents the most potential alternative to more conventional teaching methods (Akpınar). In this situation, the broad adoption of online learning has been linked to an increase in reports of psychological suffering, which may be attributable to these unfavorable preconceptions. Past research has revealed that the lack of a traditional classroom atmosphere has contributed to a negative attitude among tertiary students (Akpınar). Consequently, the benefits of online learning might not be as apparent as they might seem.

Education, in the conventional sense, offers many practical benefits. Employers tend to give more credence to degrees earned in a conventional setting than those earned online because of this reputation. In addition, students might benefit from networking with experts in their industry via conventional educational settings. Nevertheless, since it can be done in the student’s own time and pace, online learning makes it easier for students to juggle their academic and professional obligations. There are prospects for growth in both conventional and online learning environments. Regular schooling provides a regimented setting that fosters self-control, maturity, and accountability. It is the mode of education that is considered to be standardized for professional employees and highly valued on the market. On the other hand, online learning necessitates students to be self-directed and self-motivated, hence represents a valuable skillset. However, due to the novelty of such approach various companies tend to oversee online education certificates as a supplement rather than a separate qualification.

In conclusion, there are advantages and disadvantages to both conventional and online learning. With the COVID-19 epidemic, online courses have become the standard method of receiving an education. While deciding between conventional and online education, it is crucial to consider the effects on students’ mental health, career rewards, and personal growth. The choice should be made based on one’s unique requirements, learning style, and life circumstances.

Works Cited

Akpınar, Ezgin. “The Effect of Online Learning on Tertiary Level Students Mental Health during the Covid-19 Lockdown“2021: n. pag. Crossref. Web.

Al-Okaily, Manaf, et al. “ Impact of Covid-19 Pandemic on Acceptance of e-Learning System in Jordan: A Case of Transforming the Traditional Education Systems .” Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews , vol. 8, no. 4, 2020, pp. 840–851., Web.

He, Liyun, et al. “ Synchronous Distance Education vs Traditional Education for Health Science Students: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis .” Medical Education , vol. 55, no. 3, 2020, pp. 293–308., Web.

- The Democratic Learning Environment

- Self-Direction in Online Learning

- Synchronous and Just-In-Time Manufacturing and Planning

- The Woman Warrior, Ode of Mulan and The Mulan Film

- Network Based Learning Activity

- Social and Emotional Learning in Schools

- The Roles of Families in Virtual Learning

- Place-Based Learning vs. Traditional Learning

- Distance Learning: Advantages and Limitations

- The 5-3 Game Plan for Learning and Its Alternatives

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 1). Conventional vs. Online Learning: Pros and Cons. https://ivypanda.com/essays/conventional-vs-online-learning-pros-and-cons/

"Conventional vs. Online Learning: Pros and Cons." IvyPanda , 1 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/conventional-vs-online-learning-pros-and-cons/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Conventional vs. Online Learning: Pros and Cons'. 1 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Conventional vs. Online Learning: Pros and Cons." March 1, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/conventional-vs-online-learning-pros-and-cons/.

1. IvyPanda . "Conventional vs. Online Learning: Pros and Cons." March 1, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/conventional-vs-online-learning-pros-and-cons/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Conventional vs. Online Learning: Pros and Cons." March 1, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/conventional-vs-online-learning-pros-and-cons/.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Issues We Care About

- Digital Divide

- Affordability

- College Readiness

- Environmental Barriers

Measuring Impact

- WGU's Success Metrics

- Policy Priorities

- Annual Report

- WGU's Story

- Careers at WGU

- Impact Blog

Distance Learning vs. Traditional Learning: Pros and Cons

- Online University Experience

- See More Tags

Distance learning, often called “distance education,” is the process by which students use the internet to attend classes and complete courses to earn their degrees without having to physically attend school. Even prior to COVID-19, distance learning was experiencing steady growth, but those numbers grew exponentially during the global shutdown of schools. Many educational institutions had to design and improve online education plans while bringing teachers and students up-to-speed on distance learning technologies.

In addition to pandemic-related shifts to online education, there are many reasons students may want to pursue distance education as opposed to traditional schooling. As distance learning becomes more common, it’s important to research and decide which education model is the best fit for you.

What Is Long-Distance Learning?

Long-distance learning—also called “remote learning”—takes place in a digital classroom setting. Traditionally, academic instruction is administered on –a college or school campus. Distance learning is a distributed learning model that allows students to learn from anywhere, sometimes even on their own time.

Virtual lectures over video, emails, instant chat messages, file-sharing systems, mailed media, and prerecorded content are some of the most common means of delivery between teachers and their remote pupils.

Distance learning shouldn’t be mistaken for online learning, sometimes called e-learning. The latter will usually involve some element of in-person instruction, supplemented by the flexibility of a virtual classroom. Distance learning, meanwhile, is completely remote—special events like graduation or final exams may warrant an in-person gathering, but students and faculty will usually be separated physically for the entirety of the semester.

What Is Traditional Learning?

Since COVID-19 and the ensuing educational overhaul, there has been much debate regarding which type of learning environment is superior. Even in-person classrooms have unquestionably been changed by the pandemic; many believe these reforms are for the better, too.

New technology, new belief systems, and a brand-new attitude regarding what makes for a valuable learning experience have all had their influence over teachers and college professors nationwide, but the most devout among them still believe strongly in what a physical classroom has to offer students, especially at the college and post-grad level. Absence, as they say, may make the heart grow fonder, which is why many educators are proud to protect a traditional experience, at least for their own learners.

Traditional learning, in a general, pre-pandemic sense, describes the scenario of an instructor leading a classroom of students in person, moderating the discourse and regulating the flow of knowledge. While remote learners certainly existed before the recent digital revolution, a traditional experience was the norm before 2019.

Long-Distance Learning vs. Traditional Learning

To many, the most important factor to consider will be the fact that remote learners do not have immediate access to a real person teaching in front of them. Live lectures bridge this gap significantly, but, for some, this consideration alone is enough to tip the scale in a traditional classroom’s favor.

A few key differences between these education styles include:

- Where the lessons occur

- When the lessons occur

- The pace at which the lessons are administered

- The environment in which the student is immersed

- The independence and autonomy required on the part of the student

- The firsthand sources of information received by the student

- The level of candid interaction and attention the student receives

- Sometimes, even the cost of matriculation will vary here significantly

In-person interaction and socializing with other students is considered by many to be paramount to a comprehensive, truly enriching academic experience. For this reason, many schools have adopted a blended approach, combining the best of both worlds where and when each would be most appropriate.

There are, however, many scenarios in which an in-person classroom just isn’t ideal, safe, or even possible. The pandemic is one obvious example; the majority of parents and instructors appear to prefer this approach, as opposed to simply having every student withdraw in quarantine.

Nontraditional students are another demographic who have found a lot of success through a flexible, online education. Working mothers, those pursuing advanced degrees after hours, and even young people hoping to catch up after a period of personal turmoil or illness may all be able to benefit from the freedom of a virtual learning experience.

Ultimately, the efficacy of the program depends greatly upon the student in question. Either approach can result in an educated individual, ready to graduate and take on the world.

What Are the Pros and Cons of Distance Learning?

Technical elements.

Online or distance learning often has technology involved to help you do your coursework.

There are many pros to the technological elements of distance learning. Many students are able to quickly learn new tech and excel in it, even listing their skills with learning programs and platforms on their résumé. Another huge pro of distance learning technology is that you can pursue your education from anywhere with internet access. The rise of virtual tools like Zoom, Slack, Blackboard, and Google Classroom have made it even easier for students and teachers to share information and to connect.

Sometimes, students will encounter technical difficulties with online learning. There may be days when their internet doesn’t work, when programs and software fail, or they’re unable to access their courses. This can be frustrating, though often these bugs are fixed quickly, and students are able to continue with their work.

Credibility

Every student wants to know that their work will be valuable to a potential employer. Are online colleges credible? Is online learning effective? These may be questions students ask when considering distance learning.

More employers than ever before recognize that online learning is credible and legitimate. According to CNN, 83% of executives say that an online degree is as credible as one earned through a traditional program. The fact that more than half of all American adults believe that believe that an online education will often be just as good as an in-person experience has many long-standing institutions rethinking their stances. This number of is growing, too —those who assert that remote learning may be superior in some cases more than doubled between 2021 and 2022.

What’s important to employers is that your school is accredited. Universities work hard to achieve and maintain accreditation, which ensures that students earn degrees that are valuable to them and to employers. Additionally, employers may respect you more for having received an online education; they’ll recognize the time and discipline it takes to pursue distance learning and may be more impressed by it.

Some employers and companies may still rank online education as lower than a degree from a traditional college. When employers don’t understand the rigor and quality of an online education, they may be hesitant to hire someone with an online degree. Additionally, for-profit or non-accredited online schools are often a huge issue for credibility. When it comes to pursuing an online degree, make sure that the online program is accredited and offers marketable credentials. Communicating these factors typically validates a program to potential employers.

Flexibility

Flexibility is the main reason many people choose online education. But there are pros and cons involved with the flexibility of distance learning.

If you have a full-time job or family responsibilities, then the flexibility of online education would allow you a better work-life balance. With distance learning, you don’t have to worry about commuting to and from school, coordinating childcare, or leaving work to attend class. You can continue with your job and family needs, completing your schooling when the timing is right for you. And at institutions like WGU, you can complete coursework and take exams according to your schedule. With competency-based education, you can move more quickly through material you understand well, and spend more time on material you need help with. This flexibility means that you’re in charge of your schedule.

Some distance learning options don’t offer as much flexibility as you need, requiring you to log in to class at a set time or view discussions live. While it still may be more convenient than driving to a campus, this scheduled online learning may lack the flexibility you need. WGU, on the other hand, doesn’t require you to log in at a certain time to view lectures or have discussions. But the flexibility of online learning can be difficult for those who are not self-motivated. Since you’re not expected to show up at a certain time, you need the discipline to make time for your education.

Social Interactions

Some students are concerned that distance learning will mean that they’re entirely alone, but that is rarely the case.

Online learning often offers many opportunities for students to interact with others. For example, WGU students often work with their Program Mentor over the phone or email, giving them an important lifeline to someone invested in their success. Students can also interact with Course Instructors if they have questions or concerns. Additionally, student networking allows WGU students to socialize, compare thoughts on courses, and offer help. And a large alumni network means you can continue to make connections throughout your career.

For students who want to speak to others face-to-face or participate in in-person clubs or events, distance learning may not be the best option. While you can still be social with online education, most interactions occur over the phone or on online platforms.

Is Distance Learning Right for Me?

If you’re thinking about an online degree program , it’s important to ask yourself:

- Do I have the self-discipline and motivation to do distance learning?

- Do I have the time to commit to online education? Or can I find an online program that fits into my life?

- Do I feel comfortable asking for help?

While online learning may not be for everyone, many of the questions students have about pursuing distance education can be answered. Some students will find that for them, the pros greatly outweigh the cons. If you’re ready to pursue higher education in the way that works best for you, consider l ong-distance learning and online programs at WGU.

Ready to Start Your Journey?

HEALTH & NURSING

Recommended Articles

Take a look at other articles from WGU. Our articles feature information on a wide variety of subjects, written with the help of subject matter experts and researchers who are well-versed in their industries. This allows us to provide articles with interesting, relevant, and accurate information.

Business Management: Industry Outlook and Emerging Trends

Mastering Data-Driven Decision-Making Strategies

Decision Process Mapping: Streamline Your Decision-Making Process

Older Americans Month: Antonette Burroughs

How to Prepare for Nursing School: 2024 Guide

7 Jobs for Organized People

The university.

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

For Students

- Student Portal

- Alumni Services

Most Visited Links

- Business Programs

- Bachelor's Degrees

- Student Experience

- Online Degrees

- Scholarships

- Financial Aid

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Testimonials

- Student Communities

How Effective Is Online Learning? What the Research Does and Doesn’t Tell Us

- Share article

Editor’s Note: This is part of a series on the practical takeaways from research.

The times have dictated school closings and the rapid expansion of online education. Can online lessons replace in-school time?

Clearly online time cannot provide many of the informal social interactions students have at school, but how will online courses do in terms of moving student learning forward? Research to date gives us some clues and also points us to what we could be doing to support students who are most likely to struggle in the online setting.

The use of virtual courses among K-12 students has grown rapidly in recent years. Florida, for example, requires all high school students to take at least one online course. Online learning can take a number of different forms. Often people think of Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs, where thousands of students watch a video online and fill out questionnaires or take exams based on those lectures.

In the online setting, students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation.

Most online courses, however, particularly those serving K-12 students, have a format much more similar to in-person courses. The teacher helps to run virtual discussion among the students, assigns homework, and follows up with individual students. Sometimes these courses are synchronous (teachers and students all meet at the same time) and sometimes they are asynchronous (non-concurrent). In both cases, the teacher is supposed to provide opportunities for students to engage thoughtfully with subject matter, and students, in most cases, are required to interact with each other virtually.

Coronavirus and Schools

Online courses provide opportunities for students. Students in a school that doesn’t offer statistics classes may be able to learn statistics with virtual lessons. If students fail algebra, they may be able to catch up during evenings or summer using online classes, and not disrupt their math trajectory at school. So, almost certainly, online classes sometimes benefit students.

In comparisons of online and in-person classes, however, online classes aren’t as effective as in-person classes for most students. Only a little research has assessed the effects of online lessons for elementary and high school students, and even less has used the “gold standard” method of comparing the results for students assigned randomly to online or in-person courses. Jessica Heppen and colleagues at the American Institutes for Research and the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research randomly assigned students who had failed second semester Algebra I to either face-to-face or online credit recovery courses over the summer. Students’ credit-recovery success rates and algebra test scores were lower in the online setting. Students assigned to the online option also rated their class as more difficult than did their peers assigned to the face-to-face option.

Most of the research on online courses for K-12 students has used large-scale administrative data, looking at otherwise similar students in the two settings. One of these studies, by June Ahn of New York University and Andrew McEachin of the RAND Corp., examined Ohio charter schools; I did another with colleagues looking at Florida public school coursework. Both studies found evidence that online coursetaking was less effective.

About this series

This essay is the fifth in a series that aims to put the pieces of research together so that education decisionmakers can evaluate which policies and practices to implement.

The conveners of this project—Susanna Loeb, the director of Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform, and Harvard education professor Heather Hill—have received grant support from the Annenberg Institute for this series.

To suggest other topics for this series or join in the conversation, use #EdResearchtoPractice on Twitter.

Read the full series here .

It is not surprising that in-person courses are, on average, more effective. Being in person with teachers and other students creates social pressures and benefits that can help motivate students to engage. Some students do as well in online courses as in in-person courses, some may actually do better, but, on average, students do worse in the online setting, and this is particularly true for students with weaker academic backgrounds.

Students who struggle in in-person classes are likely to struggle even more online. While the research on virtual schools in K-12 education doesn’t address these differences directly, a study of college students that I worked on with Stanford colleagues found very little difference in learning for high-performing students in the online and in-person settings. On the other hand, lower performing students performed meaningfully worse in online courses than in in-person courses.

But just because students who struggle in in-person classes are even more likely to struggle online doesn’t mean that’s inevitable. Online teachers will need to consider the needs of less-engaged students and work to engage them. Online courses might be made to work for these students on average, even if they have not in the past.

Just like in brick-and-mortar classrooms, online courses need a strong curriculum and strong pedagogical practices. Teachers need to understand what students know and what they don’t know, as well as how to help them learn new material. What is different in the online setting is that students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation. The teacher will need to set norms for engagement—such as requiring students to regularly ask questions and respond to their peers—that are different than the norms in the in-person setting.

Online courses are generally not as effective as in-person classes, but they are certainly better than no classes. A substantial research base developed by Karl Alexander at Johns Hopkins University and many others shows that students, especially students with fewer resources at home, learn less when they are not in school. Right now, virtual courses are allowing students to access lessons and exercises and interact with teachers in ways that would have been impossible if an epidemic had closed schools even a decade or two earlier. So we may be skeptical of online learning, but it is also time to embrace and improve it.

A version of this article appeared in the April 01, 2020 edition of Education Week as How Effective Is Online Learning?

Sign Up for EdWeek Tech Leader

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

A Comparison of Student Learning Outcomes: Online Education vs. Traditional Classroom Instruction

Despite the prevalence of online learning today, it is often viewed as a less favorable option when compared to the traditional, in-person educational experience. Criticisms of online learning come from various sectors, like employer groups, college faculty, and the general public, and generally includes a lack of perceived quality as well as rigor. Additionally, some students report feelings of social isolation in online learning (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019).

In my experience as an online student as well as an online educator, online learning has been just the opposite. I have been teaching in a fully online master’s degree program for the last three years and have found it to be a rich and rewarding experience for students and faculty alike. As an instructor, I have felt more connected to and engaged with my online students when compared to in-person students. I have also found that students are actively engaged with course content and demonstrate evidence of higher-order thinking through their work. Students report high levels of satisfaction with their experiences in online learning as well as the program overall as indicated in their Student Evaluations of Teaching (SET) at the end of every course. I believe that intelligent course design, in addition to my engagement in professional development related to teaching and learning online, has greatly influenced my experience.

In an article by Wiley Education Services, authors identified the top six challenges facing US institutions of higher education, and include:

- Declining student enrollment

- Financial difficulties

- Fewer high school graduates

- Decreased state funding

- Lower world rankings

- Declining international student enrollments

Of the strategies that institutions are exploring to remedy these issues, online learning is reported to be a key focus for many universities (“Top Challenges Facing US Higher Education”, n.d.).

Babson Survey Research Group, 2016, [PDF file].

Some of the questions I would like to explore in further research include:

- What factors influence engagement and connection in distance education?

- Are the learning outcomes in online education any different than the outcomes achieved in a traditional classroom setting?

- How do course design and instructor training influence these factors?

- In what ways might educational technology tools enhance the overall experience for students and instructors alike?

In this literature review, I have chosen to focus on a comparison of student learning outcomes in online education versus the traditional classroom setting. My hope is that this research will unlock the answers to some of the additional questions posed above and provide additional direction for future research.

Online Learning Defined

According to Mayadas, Miller, and Sener (2015), online courses are defined by all course activity taking place online with no required in-person sessions or on-campus activity. It is important to note, however, that the Babson Survey Research Group, a prominent organization known for their surveys and research in online learning, defines online learning as a course in which 80-100% occurs online. While this distinction was made in an effort to provide consistency in surveys year over year, most institutions continue to define online learning as learning that occurs 100% online.

Blended or hybrid learning is defined by courses that mix face to face meetings, sessions, or activities with online work. The ratio of online to classroom activity is often determined by the label in which the course is given. For example, a blended classroom course would likely include more time spent in the classroom, with the remaining work occurring outside of the classroom with the assistance of technology. On the other hand, a blended online course would contain a greater percentage of work done online, with some required in-person sessions or meetings (Mayadas, Miller, & Sener, 2015).

A classroom course (also referred to as a traditional course) refers to course activity that is anchored to a regular meeting time.

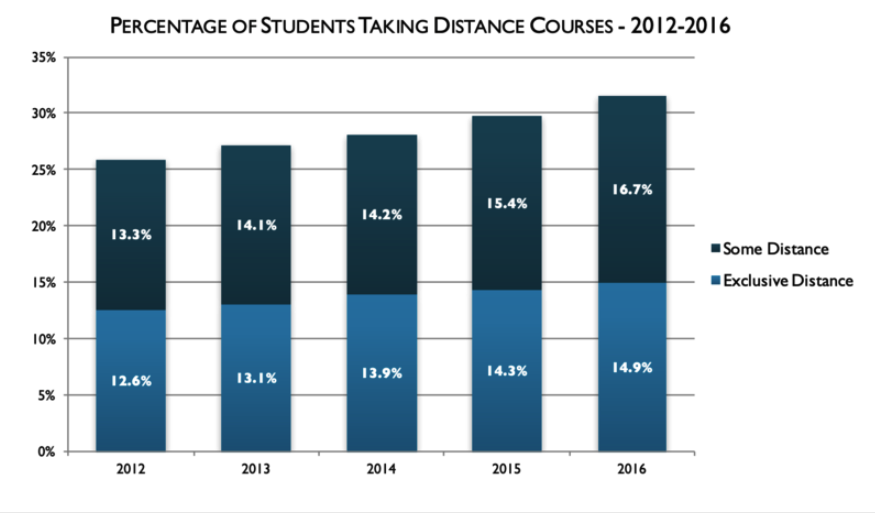

Enrollment Trends in Online Education

There has been an upward trend in the number of postsecondary students enrolled in online courses in the U.S. since 2002. A report by the Babson Survey Research Group showed that in 2016, more than six million students were enrolled in at least one online course. This number accounted for 31.6% of all college students (Seaman, Allen, & Seaman, 2018). Approximately one in three students are enrolled in online courses with no in-person component. Of these students, 47% take classes in a fully online program. The remaining 53% take some, but not all courses online (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019).

(Seaman et al., 2016, p. 11)

Perceptions of Online Education

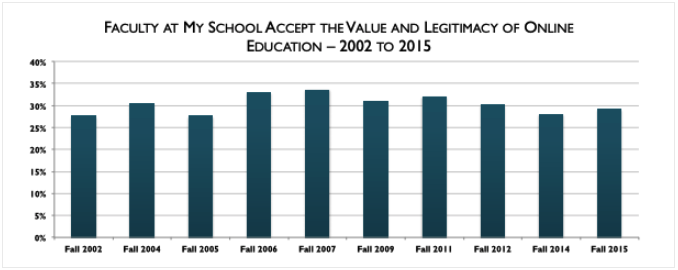

In a 2016 report by the Babson Survey Research Group, surveys of faculty between 2002-2015 showed approval ratings regarding the value and legitimacy of online education ranged from 28-34 percent. While numbers have increased and decreased over the thirteen-year time frame, faculty approval was at 29 percent in 2015, just 1 percent higher than the approval ratings noted in 2002 – indicating that perceptions have remained relatively unchanged over the years (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016).

(Allen, I.E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., Taylor Strout, T., 2016, p. 26)

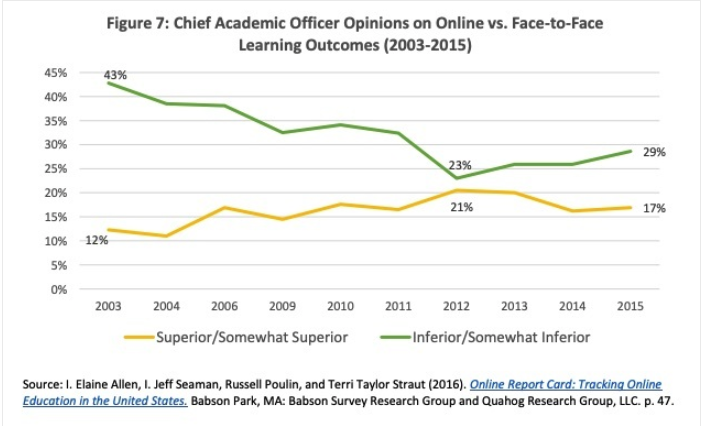

In a separate survey of chief academic officers, perceptions of online learning appeared to align with that of faculty. In this survey, leaders were asked to rate their perceived quality of learning outcomes in online learning when compared to traditional in-person settings. While the percentage of leaders rating online learning as “inferior” or “somewhat inferior” to traditional face-to-face courses dropped from 43 percent to 23 percent between 2003 to 2012, the number rose again to 29 percent in 2015 (Allen, Seaman, Poulin, & Straut, 2016).

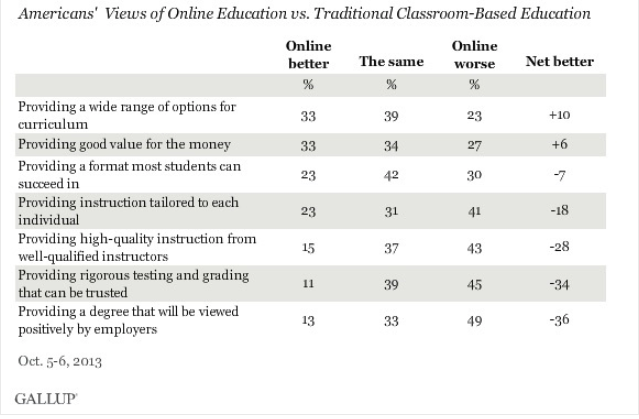

Faculty and academic leaders in higher education are not alone when it comes to perceptions of inferiority when compared to traditional classroom instruction. A 2013 Gallop poll assessing public perceptions showed that respondents rated online education as “worse” in five of the seven categories seen in the table below.

(Saad, L., Busteed, B., and Ogisi, M., 2013, October 15)

In general, Americans believed that online education provides both lower quality and less individualized instruction and less rigorous testing and grading when compared to the traditional classroom setting. In addition, respondents also thought that employers would perceive a degree from an online program less positively when compared to a degree obtained through traditional classroom instruction (Saad, Busteed, & Ogisi, 2013).

Student Perceptions of Online Learning

So what do students have to say about online learning? In Online College Students 2015: Comprehensive Data on Demands and Preferences, 1500 college students who were either enrolled or planning to enroll in a fully online undergraduate, graduate, or certificate program were surveyed. 78 percent of students believed the academic quality of their online learning experience to be better than or equal to their experiences with traditional classroom learning. Furthermore, 30 percent of online students polled said that they would likely not attend classes face to face if their program were not available online (Clienfelter & Aslanian, 2015). The following video describes some of the common reasons why students choose to attend college online.

How Online Learning Affects the Lives of Students ( Pearson North America, 2018, June 25)

In a 2015 study comparing student perceptions of online learning with face to face learning, researchers found that the majority of students surveyed expressed a preference for traditional face to face classes. A content analysis of the findings, however, brought attention to two key ideas: 1) student opinions of online learning may be based on “old typology of distance education” (Tichavsky, et al, 2015, p.6) as opposed to actual experience, and 2) a student’s inclination to choose one form over another is connected to issues of teaching presence and self-regulated learning (Tichavsky et al, 2015).

Student Learning Outcomes

Given the upward trend in student enrollment in online courses in postsecondary schools and the steady ratings of the low perceived value of online learning by stakeholder groups, it should be no surprise that there is a large body of literature comparing student learning outcomes in online classes to the traditional classroom environment.

While a majority of the studies reviewed found no significant difference in learning outcomes when comparing online to traditional courses (Cavanaugh & Jacquemin, 2015; Kemp & Grieve, 2014; Lyke & Frank 2012; Nichols, Shaffer, & Shockey, 2003; Stack, 2015; Summers, Waigandt, & Whittaker, 2005), there were a few outliers. In a 2019 report by Protopsaltis & Baum, authors confirmed that while learning is often found to be similar between the two mediums, students “with weak academic preparation and those from low-income and underrepresented backgrounds consistently underperform in fully-online environments” (Protopsaltis & Baum, 2019, n.p.). An important consideration, however, is that these findings are primarily based on students enrolled in online courses at the community college level – a demographic with a historically high rate of attrition compared to students attending four-year institutions (Ashby, Sadera, & McNary, 2011). Furthermore, students enrolled in online courses have been shown to have a 10 – 20 percent increase in attrition over their peers who are enrolled in traditional classroom instruction (Angelino, Williams, & Natvig, 2007). Therefore, attrition may be a key contributor to the lack of achievement seen in this subgroup of students enrolled in online education.

In contrast, there were a small number of studies that showed that online students tend to outperform those enrolled in traditional classroom instruction. One study, in particular, found a significant difference in test scores for students enrolled in an online, undergraduate business course. The confounding variable, in this case, was age. Researchers found a significant difference in performance in nontraditional age students over their traditional age counterparts. Authors concluded that older students may elect to take online classes for practical reasons related to outside work schedules, and this may, in turn, contribute to the learning that occurs overall (Slover & Mandernach, 2018).

In a meta-analysis and review of online learning spanning the years 1996 to 2008, authors from the US Department of Education found that students who took all or part of their classes online showed better learning outcomes than those students who took the same courses face-to-face. In these cases, it is important to note that there were many differences noted in the online and face-to-face versions, including the amount of time students spent engaged with course content. The authors concluded that the differences in learning outcomes may be attributed to learning design as opposed to the specific mode of delivery (Means, Toyoma, Murphy, Bakia, Jones, 2009).

Limitations and Opportunities

After examining the research comparing student learning outcomes in online education with the traditional classroom setting, there are many limitations that came to light, creating areas of opportunity for additional research. In many of the studies referenced, it is difficult to determine the pedagogical practices used in course design and delivery. Research shows the importance of student-student and student-teacher interaction in online learning, and the positive impact of these variables on student learning (Bernard, Borokhovski, Schmid, Tamim, & Abrami, 2014). Some researchers note that while many studies comparing online and traditional classroom learning exist, the methodologies and design issues make it challenging to explain the results conclusively (Mollenkopf, Vu, Crow, & Black, 2017). For example, some online courses may be structured in a variety of ways, i.e. self-paced, instructor-led and may be classified as synchronous or asynchronous (Moore, Dickson-Deane, Galyan, 2011)

Another gap in the literature is the failure to use a common language across studies to define the learning environment. This issue is explored extensively in a 2011 study by Moore, Dickson-Deane, and Galyan. Here, the authors examine the differences between e-learning, online learning, and distance learning in the literature, and how the terminology is often used interchangeably despite the variances in characteristics that define each. The authors also discuss the variability in the terms “course” versus “program”. This variability in the literature presents a challenge when attempting to compare one study of online learning to another (Moore, Dickson-Deane, & Galyan, 2011).

Finally, much of the literature in higher education focuses on undergraduate-level classes within the United States. Little research is available on outcomes in graduate-level classes as well as general information on student learning outcomes and perceptions of online learning outside of the U.S.

As we look to the future, there are additional questions to explore in the area of online learning. Overall, this research led to questions related to learning design when comparing the two modalities in higher education. Further research is needed to investigate the instructional strategies used to enhance student learning, especially in students with weaker academic preparation or from underrepresented backgrounds. Given the integral role that online learning is expected to play in the future of higher education in the United States, it may be even more critical to move beyond comparisons of online versus face to face. Instead, choosing to focus on sound pedagogical quality with consideration for the mode of delivery as a means for promoting positive learning outcomes.

Allen, I.E., Seaman, J., Poulin, R., & Straut, T. (2016). Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States [PDF file]. Babson Survey Research Group. http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/onlinereportcard.pdf

Angelino, L. M., Williams, F. K., & Natvig, D. (2007). Strategies to engage online students and reduce attrition rates. The Journal of Educators Online , 4(2).

Ashby, J., Sadera, W.A., & McNary, S.W. (2011). Comparing student success between developmental math courses offered online, blended, and face-to-face. Journal of Interactive Online Learning , 10(3), 128-140.

Bernard, R.M., Borokhovski, E., Schmid, R.F., Tamim, R.M., & Abrami, P.C. (2014). A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. Journal of Computing in Higher Education , 26(1), 87-122.

Cavanaugh, J.K. & Jacquemin, S.J. (2015). A large sample comparison of grade based student learning outcomes in online vs. face-fo-face courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 19(2).

Clinefelter, D. L., & Aslanian, C. B. (2015). Online college students 2015: Comprehensive data on demands and preferences. https://www.learninghouse.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/OnlineCollegeStudents2015.pdf

Golubovskaya, E.A., Tikhonova, E.V., & Mekeko, N.M. (2019). Measuring learning outcome and students’ satisfaction in ELT (e-learning against conventional learning). Paper presented the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 34-38. Doi: 10.1145/3337682.3337704

Kemp, N. & Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates’ opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Frontiers in Psychology , 5. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01278

Lyke, J., & Frank, M. (2012). Comparison of student learning outcomes in online and traditional classroom environments in a psychology course. (Cover story). Journal of Instructional Psychology , 39(3/4), 245-250.

Mayadas, F., Miller, G. & Senner, J. Definitions of E-Learning Courses and Programs Version 2.0. Online Learning Consortium. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/updated-e-learning-definitions-2/

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. US Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/tech/evidence-based-practices/finalreport.pdf

Mollenkopf, D., Vu, P., Crow, S, & Black, C. (2017). Does online learning deliver? A comparison of student teacher outcomes from candidates in face to face and online program pathways. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration. 20(1).

Moore, J.L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyan, K. (2011). E-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education . 14(2), 129-135.

Nichols, J., Shaffer, B., & Shockey, K. (2003). Changing the face of instruction: Is online or in-class more effective? College & Research Libraries , 64(5), 378–388. https://doi-org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.5860/crl.64.5.378

Parsons-Pollard, N., Lacks, T.R., & Grant, P.H. (2008). A comparative assessment of student learning outcomes in large online and traditional campus based introduction to criminal justice courses. Criminal Justice Studies , 2, 225-239.

Pearson North America. (2018, June 25). How Online Learning Affects the Lives of Students . YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPDMagf_oAE

Protopsaltis, S., & Baum, S. (2019). Does online education live up to its promise? A look at the evidence and implications for federal policy [PDF file]. http://mason.gmu.edu/~sprotops/OnlineEd.pdf

Saad, L., Busteed, B., & Ogisi, M. (October 15, 2013). In U.S., Online Education Rated Best for Value and Options. https://news.gallup.com/poll/165425/online-education-rated-best-value-options.aspx

Stack, S. (2015). Learning Outcomes in an Online vs Traditional Course. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 9(1).

Seaman, J.E., Allen, I.E., & Seaman, J. (2018). Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States [PDF file]. Babson Survey Research Group. http://onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradeincrease.pdf

Slover, E. & Mandernach, J. (2018). Beyond Online versus Face-to-Face Comparisons: The Interaction of Student Age and Mode of Instruction on Academic Achievement. Journal of Educators Online, 15(1) . https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1168945.pdf

Summers, J., Waigandt, A., & Whittaker, T. (2005). A Comparison of Student Achievement and Satisfaction in an Online Versus a Traditional Face-to-Face Statistics Class. Innovative Higher Education , 29(3), 233–250. https://doi-org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.1007/s10755-005-1938-x

Tichavsky, L.P., Hunt, A., Driscoll, A., & Jicha, K. (2015). “It’s just nice having a real teacher”: Student perceptions of online versus face-to-face instruction. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 9(2).

Wiley Education Services. (n.d.). Top challenges facing U.S. higher education. https://edservices.wiley.com/top-higher-education-challenges/

July 17, 2020

Online Learning

college , distance education , distance learning , face to face , higher education , online learning , postsecondary , traditional learning , university , virtual learning

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

© 2024 — Powered by WordPress

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑

Home > Blog > Tips for Online Students > Higher Education News > Online vs Traditional School: A Thorough Analysis

Higher Education News , Tips for Online Students

Online vs Traditional School: A Thorough Analysis

Updated: June 19, 2024

Published: January 23, 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In the United States alone, data from the National Center for Education Statistics reported that 43% of students were enrolled in remote instruction (online school) in early 2021. The rise of online education can be witnessed around the world as technology continues to advance. The increased attendance and desire for online colleges during COVID were also to be expected. In this article, we will assess the differences between online school vs. traditional school.

By the end of the article, you will be able to answer, “is online college better?” than traditional colleges.

What is Online School and Is it Respected?

Online school is instruction and education that takes place digitally via the Internet. Online degrees vs traditional degrees are those earned online rather than in-person and on campus.

Online school may also be called distance learning, virtual schooling, or e-learning.

The big question when considering attending an online school that often arises is whether or not your future employer (or future educational institution) will respect or accept your online degree .

Since online school is becoming more popular, the social sentiments around online schooling are too. In fact, 83% of surveyed business leaders expressed that an online degree from a “well-known” institute holds the same value as one earned on campus.

One of the main things to look for when attending an online school is its accreditation status. Accreditation is the process of having an independent third-party evaluate an institution to ensure its credibility. The third-party will confirm whether or not the institution is equipped to deliver its promises and mission. For some graduate programs, they will only accept an undergraduate degree from an accredited program. This is another reason why it’s so important to check for accreditation when enrolling at an online school.

Advantages of Online School

When you consider the various benefits of online school, it’s clear to see why the option is becoming so popular. Here’s a look at some of the advantages:

Affordability

Since online schools don’t necessarily have to operate a campus and cover those exorbitant costs, they tend to be more cost-effective and affordable than their traditional counterparts. In fact, you can even find online colleges that are tuition-free. For example, the University of the People is just that – a 100% online and tuition-free institution. There are some fees associated with attendance, but they add up to much less than that of the tuition at other schools.

Flexibility

Online school also tends to be more flexible in terms of scheduling than a traditional college. The reason is when it comes to earning an online degree vs on-campus, you can do so at your own pace. If classes are pre-recorded, then it’s up to the student to decide when to learn. In a traditional college setting, there’s a set schedule as to when the professor teaches a specific subject. There’s also a cap on how many students can attend each lecture. This means that some students may end up having to wait another semester or quarter (or in the worst case a whole year) to get into a class they might need to graduate.

Location independent

Geographic barriers can hinder one’s ability to attend a certain institution. Whether that is because of cost, visas, or responsibilities at home, or an existing job, learning online removes the element of the location as a concern. With online college, you can learn virtually from anywhere you choose.

Fewer distractions

Depending on how you set up your learning environment to attend the online school, it can be designed to be less distracting than that of an on-campus setting. Peers may distract you in class. Students who get up or chat during tests or lectures can hinder their ability to learn. With an online school, your environment ends up being more within your control.

Online schools also offer the option to learn at your own pace. You can enroll part-time or full-time, log on morning or night, and choose to work through coursework quickly or slowly.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”48358″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” img_link_target=”_blank” css_animation=”flipInX” link=”https://go.uopeople.edu/admission-application.html” el_id=”cta-blog-picture”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Disadvantages of Online School

With so many benefits of online school, you may wonder, “What’s the downside?” Well, that really depends on you!

Requires self-motivation

With online school being self-paced and offering so much flexibility, it’s up to you to remain self-motivated and engaged. You won’t be surrounded by students or expected to show up to a lecture. Instead, it’s up to you to log on, maintain a schedule , and stay focused.

Technical considerations

With online school, there’s a requirement for sound technology to support your learning endeavors. The good news is that schools like the University of the People require nothing more than a strong internet connection and a compatible device. Once you have your tech stack sorted, you can log on and learn from anywhere in the world!

Advantages of Traditional School

Now that we’ve touched on the good and the bad of online school, it’s only fair to consider the advantages of traditional school.

Take a look:

Social experience

For some, the social experience of college or learning alongside peers is something that cannot be replaced. Students have a chance to develop in-person social skills while attending school.

Public speaking skills

In school, you may be tasked with assignments and projects that require you to get up in front of large amounts of students to present. These kinds of activities will help you build public speaking skills. While it is possible you’d do this in an online school via video, the atmosphere feels different when you can sense the energy of your audience in person.

Hands-on lab sessions

There are some subjects that are completely different in person. For example, think about the need for hands-on labs when it comes to learning hard sciences.

Disadvantages of Traditional School

It’s pretty safe to say that when comparing online school vs traditional school, online school’s advantages tend to be traditional school’s disadvantages. You can bank on paying a higher cost to attend a traditional school and you won’t have flexible scheduling. Additionally, you may have to deal with:

Commute time

If you have classes on campus, you’ll have to find your way to campus, which adds commute time to your schedule.

Loss of individualization

It may be the case that you find yourself in a lecture hall with 300 students and the professor will never know your name. Traditional education tends to operate under a one-size-fits-all model. On the other hand, online school is more malleable and you can access online learning materials that are better suited to your learning style.

Online Learning at the University of the People

After reading this, you may be more interested in attending online school than ever before. It makes sense why you’d feel that way!

University of the People, a tuition-free university , offers a variety of degree-granting and certificate programs. For example, you can earn your degree (at various levels such as associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s) in Health Science, Education, Computer Science, or Business Administration. Take a look. And, we also are accredited .

Closing Thoughts

Comparing the pros and cons of online school vs traditional school will look different for everyone. It’s a personal choice as to what you think will work better for you, your career and educational goals, and your own personal situation. While we promised to answer is online school better than traditional, the only answer can come from you and how you feel about it.

We hope we’ve helped you to better understand the differences and benefits of each style of instruction!

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”50504″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” style=”vc_box_circle_2″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=” “I couldn’t apply for any loans so I decided not to go to college…then I was told about UoPeople“ ” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left|color:%234b345d” use_theme_fonts=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1653909754521{margin-top: 10px !important;}”][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1653909787168{margin-top: 10px !important;margin-bottom: 10px !important;}”]

Nathaly Ordonez

Business Administration Student, US

[/vc_column_text][vc_btn title=” BECOME A STUDENT ” style=”custom” custom_background=”#e90172″ custom_text=”#ffffff” shape=”square” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fgo.uopeople.edu%2Fadmission-application.html” el_class=”become_btn”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

In this article

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone. Read More

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 January 2024

Online vs in-person learning in higher education: effects on student achievement and recommendations for leadership

- Bandar N. Alarifi 1 &

- Steve Song 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 86 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

3 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

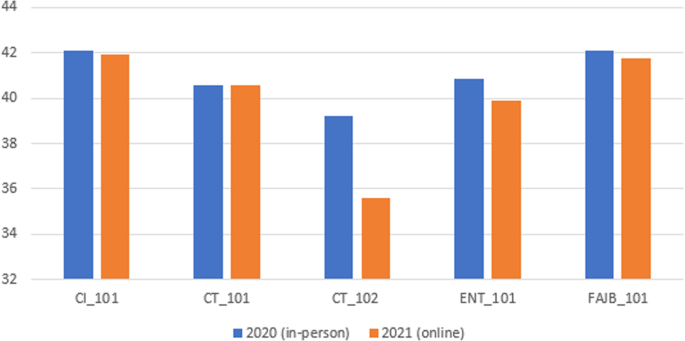

- Science, technology and society

This study is a comparative analysis of online distance learning and traditional in-person education at King Saud University in Saudi Arabia, with a focus on understanding how different educational modalities affect student achievement. The justification for this study lies in the rapid shift towards online learning, especially highlighted by the educational changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. By analyzing the final test scores of freshman students in five core courses over the 2020 (in-person) and 2021 (online) academic years, the research provides empirical insights into the efficacy of online versus traditional education. Initial observations suggested that students in online settings scored lower in most courses. However, after adjusting for variables like gender, class size, and admission scores using multiple linear regression, a more nuanced picture emerged. Three courses showed better performance in the 2021 online cohort, one favored the 2020 in-person group, and one was unaffected by the teaching format. The study emphasizes the crucial need for a nuanced, data-driven strategy in integrating online learning within higher education systems. It brings to light the fact that the success of educational methodologies is highly contingent on specific contextual factors. This finding advocates for educational administrators and policymakers to exercise careful and informed judgment when adopting online learning modalities. It encourages them to thoroughly evaluate how different subjects and instructional approaches might interact with online formats, considering the variable effects these might have on learning outcomes. This approach ensures that decisions about implementing online education are made with a comprehensive understanding of its diverse and context-specific impacts, aiming to optimize educational effectiveness and student success.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Quality of a master’s degree in education in Ecuador

Co-designing inclusive excellence in higher education: Students’ and teachers’ perspectives on the ideal online learning environment using the I-TPACK model

Introduction.

The year 2020 marked an extraordinary period, characterized by the global disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments and institutions worldwide had to adapt to unforeseen challenges across various domains, including health, economy, and education. In response, many educational institutions quickly transitioned to distance teaching (also known as e-learning, online learning, or virtual classrooms) to ensure continued access to education for their students. However, despite this rapid and widespread shift to online learning, a comprehensive examination of its effects on student achievement in comparison to traditional in-person instruction remains largely unexplored.

In research examining student outcomes in the context of online learning, the prevailing trend is the consistent observation that online learners often achieve less favorable results when compared to their peers in traditional classroom settings (e.g., Fischer et al., 2020 ; Bettinger et al., 2017 ; Edvardsson and Oskarsson, 2008 ). However, it is important to note that a significant portion of research on online learning has primarily focused on its potential impact (Kuhfeld et al., 2020 ; Azevedo et al., 2020 ; Di Pietro et al., 2020 ) or explored various perspectives (Aucejo et al., 2020 ; Radha et al., 2020 ) concerning distance education. These studies have often omitted a comprehensive and nuanced examination of its concrete academic consequences, particularly in terms of test scores and grades.

Given the dearth of research on the academic impact of online learning, especially in light of Covid-19 in the educational arena, the present study aims to address that gap by assessing the effectiveness of distance learning compared to in-person teaching in five required freshmen-level courses at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia. To accomplish this objective, the current study compared the final exam results of 8297 freshman students who were enrolled in the five courses in person in 2020 to their 8425 first-year counterparts who has taken the same courses at the same institution in 2021 but in an online format.

The final test results of the five courses (i.e., University Skills 101, Entrepreneurship 101, Computer Skills 101, Computer Skills 101, and Fitness and Health Culture 101) were examined, accounting for potential confounding factors such as gender, class size and admission scores, which have been cited in past research to be correlated with student achievement (e.g., Meinck and Brese, 2019 ; Jepsen, 2015 ) Additionally, as the preparatory year at King Saud University is divided into five tracks—health, nursing, science, business, and humanity, the study classified students based on their respective disciplines.

Motivation for the study

The rapid expansion of distance learning in higher education, particularly highlighted during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (Volk et al., 2020 ; Bettinger et al., 2017 ), underscores the need for alternative educational approaches during crises. Such disruptions can catalyze innovation and the adoption of distance learning as a contingency plan (Christensen et al., 2015 ). King Saud University, like many institutions worldwide, faced the challenge of transitioning abruptly to online learning in response to the pandemic.