- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Problem-Solving Therapy?

Verywell / Madelyn Goodnight

Problem-Solving Therapy Techniques

How effective is problem-solving therapy, things to consider, how to get started.

Problem-solving therapy is a brief intervention that provides people with the tools they need to identify and solve problems that arise from big and small life stressors. It aims to improve your overall quality of life and reduce the negative impact of psychological and physical illness.

Problem-solving therapy can be used to treat depression , among other conditions. It can be administered by a doctor or mental health professional and may be combined with other treatment approaches.

At a Glance

Problem-solving therapy is a short-term treatment used to help people who are experiencing depression, stress, PTSD, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and other mental health problems develop the tools they need to deal with challenges. This approach teaches people to identify problems, generate solutions, and implement those solutions. Let's take a closer look at how problem-solving therapy can help people be more resilient and adaptive in the face of stress.

Problem-solving therapy is based on a model that takes into account the importance of real-life problem-solving. In other words, the key to managing the impact of stressful life events is to know how to address issues as they arise. Problem-solving therapy is very practical in its approach and is only concerned with the present, rather than delving into your past.

This form of therapy can take place one-on-one or in a group format and may be offered in person or online via telehealth . Sessions can be anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours long.

Key Components

There are two major components that make up the problem-solving therapy framework:

- Applying a positive problem-solving orientation to your life

- Using problem-solving skills

A positive problem-solving orientation means viewing things in an optimistic light, embracing self-efficacy , and accepting the idea that problems are a normal part of life. Problem-solving skills are behaviors that you can rely on to help you navigate conflict, even during times of stress. This includes skills like:

- Knowing how to identify a problem

- Defining the problem in a helpful way

- Trying to understand the problem more deeply

- Setting goals related to the problem

- Generating alternative, creative solutions to the problem

- Choosing the best course of action

- Implementing the choice you have made

- Evaluating the outcome to determine next steps

Problem-solving therapy is all about training you to become adaptive in your life so that you will start to see problems as challenges to be solved instead of insurmountable obstacles. It also means that you will recognize the action that is required to engage in effective problem-solving techniques.

Planful Problem-Solving

One problem-solving technique, called planful problem-solving, involves following a series of steps to fix issues in a healthy, constructive way:

- Problem definition and formulation : This step involves identifying the real-life problem that needs to be solved and formulating it in a way that allows you to generate potential solutions.

- Generation of alternative solutions : This stage involves coming up with various potential solutions to the problem at hand. The goal in this step is to brainstorm options to creatively address the life stressor in ways that you may not have previously considered.

- Decision-making strategies : This stage involves discussing different strategies for making decisions as well as identifying obstacles that may get in the way of solving the problem at hand.

- Solution implementation and verification : This stage involves implementing a chosen solution and then verifying whether it was effective in addressing the problem.

Other Techniques

Other techniques your therapist may go over include:

- Problem-solving multitasking , which helps you learn to think clearly and solve problems effectively even during times of stress

- Stop, slow down, think, and act (SSTA) , which is meant to encourage you to become more emotionally mindful when faced with conflict

- Healthy thinking and imagery , which teaches you how to embrace more positive self-talk while problem-solving

What Problem-Solving Therapy Can Help With

Problem-solving therapy addresses life stress issues and focuses on helping you find solutions to concrete issues. This approach can be applied to problems associated with various psychological and physiological symptoms.

Mental Health Issues

Problem-solving therapy may help address mental health issues, like:

- Chronic stress due to accumulating minor issues

- Complications associated with traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Emotional distress

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Problems associated with a chronic disease like cancer, heart disease, or diabetes

- Self-harm and feelings of hopelessness

- Substance use

- Suicidal ideation

Specific Life Challenges

This form of therapy is also helpful for dealing with specific life problems, such as:

- Death of a loved one

- Dissatisfaction at work

- Everyday life stressors

- Family problems

- Financial difficulties

- Relationship conflicts

Your doctor or mental healthcare professional will be able to advise whether problem-solving therapy could be helpful for your particular issue. In general, if you are struggling with specific, concrete problems that you are having trouble finding solutions for, problem-solving therapy could be helpful for you.

Benefits of Problem-Solving Therapy

The skills learned in problem-solving therapy can be helpful for managing all areas of your life. These can include:

- Being able to identify which stressors trigger your negative emotions (e.g., sadness, anger)

- Confidence that you can handle problems that you face

- Having a systematic approach on how to deal with life's problems

- Having a toolbox of strategies to solve the issues you face

- Increased confidence to find creative solutions

- Knowing how to identify which barriers will impede your progress

- Knowing how to manage emotions when they arise

- Reduced avoidance and increased action-taking

- The ability to accept life problems that can't be solved

- The ability to make effective decisions

- The development of patience (realizing that not all problems have a "quick fix")

Problem-solving therapy can help people feel more empowered to deal with the problems they face in their lives. Rather than feeling overwhelmed when stressors begin to take a toll, this therapy introduces new coping skills that can boost self-efficacy and resilience .

Other Types of Therapy

Other similar types of therapy include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) . While these therapies work to change thinking and behaviors, they work a bit differently. Both CBT and SFBT are less structured than problem-solving therapy and may focus on broader issues. CBT focuses on identifying and changing maladaptive thoughts, and SFBT works to help people look for solutions and build self-efficacy based on strengths.

This form of therapy was initially developed to help people combat stress through effective problem-solving, and it was later adapted to address clinical depression specifically. Today, much of the research on problem-solving therapy deals with its effectiveness in treating depression.

Problem-solving therapy has been shown to help depression in:

- Older adults

- People coping with serious illnesses like cancer

Problem-solving therapy also appears to be effective as a brief treatment for depression, offering benefits in as little as six to eight sessions with a therapist or another healthcare professional. This may make it a good option for someone unable to commit to a lengthier treatment for depression.

Problem-solving therapy is not a good fit for everyone. It may not be effective at addressing issues that don't have clear solutions, like seeking meaning or purpose in life. Problem-solving therapy is also intended to treat specific problems, not general habits or thought patterns .

In general, it's also important to remember that problem-solving therapy is not a primary treatment for mental disorders. If you are living with the symptoms of a serious mental illness such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia , you may need additional treatment with evidence-based approaches for your particular concern.

Problem-solving therapy is best aimed at someone who has a mental or physical issue that is being treated separately, but who also has life issues that go along with that problem that has yet to be addressed.

For example, it could help if you can't clean your house or pay your bills because of your depression, or if a cancer diagnosis is interfering with your quality of life.

Your doctor may be able to recommend therapists in your area who utilize this approach, or they may offer it themselves as part of their practice. You can also search for a problem-solving therapist with help from the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Society of Clinical Psychology .

If receiving problem-solving therapy from a doctor or mental healthcare professional is not an option for you, you could also consider implementing it as a self-help strategy using a workbook designed to help you learn problem-solving skills on your own.

During your first session, your therapist may spend some time explaining their process and approach. They may ask you to identify the problem you’re currently facing, and they’ll likely discuss your goals for therapy .

Keep In Mind

Problem-solving therapy may be a short-term intervention that's focused on solving a specific issue in your life. If you need further help with something more pervasive, it can also become a longer-term treatment option.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Shang P, Cao X, You S, Feng X, Li N, Jia Y. Problem-solving therapy for major depressive disorders in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . Aging Clin Exp Res . 2021;33(6):1465-1475. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01672-3

Cuijpers P, Wit L de, Kleiboer A, Karyotaki E, Ebert DD. Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis . Eur Psychiatry . 2018;48(1):27-37. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.006

Nezu AM, Nezu CM, D'Zurilla TJ. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual . New York; 2013. doi:10.1891/9780826109415.0001

Owens D, Wright-Hughes A, Graham L, et al. Problem-solving therapy rather than treatment as usual for adults after self-harm: a pragmatic, feasibility, randomised controlled trial (the MIDSHIPS trial) . Pilot Feasibility Stud . 2020;6:119. doi:10.1186/s40814-020-00668-0

Sorsdahl K, Stein DJ, Corrigall J, et al. The efficacy of a blended motivational interviewing and problem solving therapy intervention to reduce substance use among patients presenting for emergency services in South Africa: A randomized controlled trial . Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy . 2015;10(1):46. doi:doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0042-1

Margolis SA, Osborne P, Gonzalez JS. Problem solving . In: Gellman MD, ed. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine . Springer International Publishing; 2020:1745-1747. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-39903-0_208

Kirkham JG, Choi N, Seitz DP. Meta-analysis of problem solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults . Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 2016;31(5):526-535. doi:10.1002/gps.4358

Garand L, Rinaldo DE, Alberth MM, et al. Effects of problem solving therapy on mental health outcomes in family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia: A randomized controlled trial . Am J Geriatr Psychiatry . 2014;22(8):771-781. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.07.007

Noyes K, Zapf AL, Depner RM, et al. Problem-solving skills training in adult cancer survivors: Bright IDEAS-AC pilot study . Cancer Treat Res Commun . 2022;31:100552. doi:10.1016/j.ctarc.2022.100552

Albert SM, King J, Anderson S, et al. Depression agency-based collaborative: effect of problem-solving therapy on risk of common mental disorders in older adults with home care needs . The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry . 2019;27(6):619-624. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.002

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

DIAGNOSIS: Depression TREATMENT: Problem-Solving Therapy for Depression

2015 est status : treatment pending re-evaluation very strong: high-quality evidence that treatment improves symptoms and functional outcomes at post-treatment and follow-up; little risk of harm; requires reasonable amount of resources; effective in non-research settings strong: moderate- to high-quality evidence that treatment improves symptoms or functional outcomes; not a high risk of harm; reasonable use of resources weak: low or very low-quality evidence that treatment produces clinically meaningful effects on symptoms or functional outcomes; gains from the treatment may not warrant resources involved insufficient evidence: no meta-analytic study could be identified insufficient evidence: existing meta-analyses are not of sufficient quality treatment pending re-evaluation, 1998 est status : strong research support strong: support from two well-designed studies conducted by independent investigators. modest: support from one well-designed study or several adequately designed studies. controversial: conflicting results, or claims regarding mechanisms are unsupported., strength of research support.

Find a Therapist specializing in Problem-Solving Therapy for Depression List your practice

Brief Summary

- Basic premise: the manner in which people historically and currently cope with extant stressful events via effective social problem solving may affect the degree to which they will experience psychological distress

- Essence of therapy: Contemporary Problem-Solving Therapy, or PST, is a transdiagnostic intervention, generally considered to be under a cognitive-behavioral umbrella, that increases adaptive adjustment to life problems and stress by training individuals in several affective, cognitive, and behavioral tools. The training is aimed at several barriers to effective problem solving. Through experiential practice, PST helps people to train their brains to overcome common barriers to the way they react to and attempt to solve real-life problems.

- Length : approx. 12 sessions; however, effective changes have been observed in PST programs with as few as 4 sessions and may extend to long-term intervention when individuals have long-term and inflexible problem-solving styles or a high degree of emotional dysregulation.

Treatment Resources

Editors: Alexandra Greenfield, MS

Note: The resources provided below are intended to supplement not replace foundational training in mental health treatment and evidence-based practice

Treatment Manuals / Outlines

Treatment manuals.

Treatment manuals available upon request for patients with depression and breast cancer, depression and heart failure, depression and hypertension, and veterans with housing instability (contact Dr. Arthur Nezu )

Books Available for Purchase Through External Sites

- Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual (Nezu, Nezu, & D’Zurilla)

Measures, Handouts and Worksheets

- Problem-Solving Therapy Instructional Materials and Patient Handouts (Nezu, Nezu, & D’Zurilla)

- Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R; D’Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares)

Self-help Books

- Solving Life’s Problems: A 5-Step Guide to Enhanced Well-Being (Nezu, Nezu, & D’Zurilla)

Smartphone Apps

- Moving Forward (US Dept of Veterans Affairs & US Dept of Defense)

Video Demonstrations

Videos available for purchase through external sites.

- Problem-Solving Therapy (APA/Nezu & Nezu)

Clinical Trials

- Efficacy of a social problem-solving therapy approach for unipolar depression (Nezu, 1986)

- Improving depression outcomes in older adults with comorbid medical illness (Harpole et al., 2005)

- Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial (Unützer et al., 2002)

- Behavioral activation and problem-solving therapy for depressed breast cancer patients: Preliminary support for decreased suicidal ideation (Hopko et al., 2013)

- Effects of problem solving therapy on mental health outcomes in family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia: A randomized controlled trial (Garand et al., 2013)

- Problem-solving training for family caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injuries: A randomized controlled trial (Rivera et al., 2008)

- Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction: Effect on disability (Alexopoulos et al., 2011)

- Six-month postintervention depression and disability outcomes of in-home telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income, homebound older adults (Choi et al., 2014)

- Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer (Ell et al., 2008)

- The Pathways Study: A randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression (Katon et al., 2004)

- Problem solving treatment and group psychoeducation for depression: Multicentre randomised controlled trial (Dowrick et al., 2000)

- Escitalopram and problem-solving therapy for prevention of poststroke depression: A randomized controlled trial (Robinson et al., 2000)

- Problem-solving therapy for relapse prevention in depression (Nezu & Nezu, 2010)

- Social problem-solving therapy for unipolar depression: An initial dismantling investigation (Nezu & Perri, 1989)

- Project Genesis: Assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients (Nezu et al., 2003)

Meta-analyses and Systematic Reviews

- The efficacy of problem solving therapy in reducing mental and physical health problems: A meta-analysis (Malouff, Thorsteinsson, & Schutte, 2007)

- Problem solving therapies for depression: A meta-analysis (Cuijpers, van Straten, & Warmerdam, 2007)

- Problem-solving therapy for depression: A meta-analysis (Bell & D’Zurilla, 2009)

- Brief psychological therapies for anxiety and depression in primary care: Meta-analysis and meta-regression (Cape et al., 2010)

- Brief psychotherapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Nieuwsma et al., 2012)

- Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: A network meta-analysis (Barth et al., 2013)

- Problem-solving therapy for depression in adults: A systematic review (Gellis & Kenaley, 2008)

Other Treatment Resources

- Moving Forward (free, interactive, 6-hour web program; US Dept of Veterans Affairs & US Dept of Defense)

- Social problem solving as a risk factor for depression (Nezu, Nezu, & Clark, 2008)

- Depression treatment for homebound medically ill older adults: Using evidence-based problem-solving therapy (Gellis & Nezu, 2011)

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

Join our Newsletter

Get helpful tips and the latest information

Problem-Solving Therapy: How It Works & What to Expect

Author: Lydia Antonatos, LMHC

Lydia Angelica Antonatos LMHC

Lydia has over 16 years of experience and specializes in mood disorders, anxiety, and more. She offers personalized, solution-focused therapy to empower clients on their journey to well-being.

Problem-solving therapy (PST) is an intervention with cognitive and behavioral influences used to assist individuals in managing life problems. Therapists help clients learn effective skills to address their issues directly and make positive changes. PST is used in various settings to address mental health concerns such as depression, anxiety, and more.

Find the perfect therapist for you, with BetterHelp.

If you don’t click with your first match, you can easily switch therapists. BetterHelp has over 20,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $65 per week. Take a Free Online Assessment and get matched with the right therapist for you.

What Is Problem-Solving Therapy?

Problem-solving therapy (PST) is based on a model that the body, mind, and environment all interact with each other and that life stress can interact with a person’s predisposition for developing a mental condition. 2 Within this context, PST contends that mental, emotional, and behavioral struggles stem from an ongoing inability to solve problems or deal with everyday stressors. Therefore, the key to preventing health consequences and improving quality of life is to become a better problem-solver. 3 , 4

The problem-solving model has undergone several revisions but upholds the value of teaching people to become better problem-solvers. Overall, the goal of PST is to provide individuals with a set of rational problem-solving tools to reduce the impact of stress on their well-being.

The two main components of problem-solving therapy include: 3 , 4

- Problem-solving orientation: This focuses on helping individuals adopt an optimistic outlook and see problems as opportunities to learn from, allowing them to believe they can solve problems.

- Problem-solving style: This component aims to provide people with constructive problem-solving tools to deal with different life stressors by identifying the problem, generating/brainstorming solution ideas, choosing a specific option, and implementing and reviewing it.

Techniques Used in Problem-Solving Therapy

PST emphasizes the client, and the techniques used are merely conduits that facilitate the problem-solving learning process. Generally, the individual, in collaboration and support from the clinician, leads the problem-solving work. Thus, a strong therapeutic alliance sets the foundation for encouraging clients to apply these skills outside therapy sessions. 4

Here are some of the most relevant guidelines and techniques used in problem-solving therapy:

Creating Collaboration

As with other psychotherapies, creating a collaborative environment and a healthy therapist-client relationship is essential in PST. The role of a therapist is to cultivate this bond by conveying a genuine sense of commitment to the client while displaying kindness, using active listening skills, and providing support. The purpose is to build a meaningful balance between being an active and directive clinician while delivering a feeling of optimism to encourage the client’s participation.

This tool is used in all psychotherapies and is just as essential in PST. Assessment seeks to gather facts and information about current problems and contributing stressors and evaluates a client’s appropriateness for PST. The problem-solving therapy assessment also examines a person’s immediate issues, problem-solving attitudes, and abilities, including their strengths and limitations. This sets the groundwork for developing an individualized problem-solving plan.

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation is an integral component of problem-solving therapy and is used throughout treatment. The purpose of psychoeducation is to provide a client with the rationale for problem-solving therapy, including an explanation for each step involved in the treatment plan. Moreover, the individual is educated about mental health symptoms and taught solution-oriented strategies and communication skills.

This technique involves verbal prompting, like asking leading questions, giving suggestions, and providing guidance. For example, the therapist may prompt a client to brainstorm or consider alternatives, or they may ask about times when a certain skill was used to solve a problem during a difficult situation. Coaching can be beneficial when clients struggle with eliciting solutions on their own.

Shaping intervention refers to teaching new skills and building on them as the person gradually improves the quality of each skill. Shaping works by reinforcing the desired problem-solving behavior and adding perspective as the individual gets closer to their intended goal.

In problem-solving therapy, modeling is a method in which a person learns by observing. It can include written/verbal problem-solving illustrations or demonstrations performed by the clinician in hypothetical or real-life situations. A client can learn effective problem-solving skills via role-play exercises, live demonstrations, or short-film presentations. This allows individuals to imitate observed problem-solving skills in their own lives and apply them to specific problems.

Rehearsal & Practice

These techniques provide opportunities to practice problem-solving exercises and engage in homework assignments. This may involve role-playing during therapy sessions, practicing with real-life issues, or imaginary rehearsal where individuals visualize themselves carrying out a solution. Furthermore, homework exercises are an important aspect when learning a new skill. Ongoing practice is strongly encouraged throughout treatment so a client can effectively use these techniques when faced with a problem.

Positive Reinforcement & Feedback

The therapist’s task in this intervention is to provide support and encouragement for efforts to apply various problem-solving skills. The goal is for the client to continue using more adaptive behaviors, even if they do not get it right the first time. Then, the therapist provides feedback so the client can explore barriers encountered and generate alternate solutions by weighing the pros and cons to continue working toward a specific goal.

Use of Analogies & Metaphors

When appropriate, analogies and metaphors can be useful in providing the client with a clearer vision or a better understanding of specific concepts. For example, the therapist may use diverse skills or points of reference (e.g., cooking, driving, sports) to explain the problem-solving process and find solutions to convey that time and practice are required before mastering a particular skill.

What Can Problem-Solving Therapy Help With?

Although problem-solving therapy was initially developed to treat depression among primary care patients, PST has expanded to address or rehabilitate other psychological problems, including anxiety , post-traumatic stress disorder , personality disorders , and more.

PST theory asserts that vulnerable populations can benefit from receiving constructive problem-solving tools in a therapeutic relationship to increase resiliency and prevent emotional setbacks or behaviors with destructive results like suicide. It is worth noting that in severe psychiatric cases, PST can be effectively used when integrated with other mental health interventions. 3 , 4

PST can help individuals challenged with specific issues who have difficulty finding solutions or ways to cope. These issues can involve a wide range of incidents, such as the death of a loved one, divorce, stress related to a chronic medical diagnosis, financial stress , marital difficulties, or tension at work.

Through the problem-solving approach, mental and emotional distress can be reduced by helping individuals break down problems into smaller pieces that are easier to manage and cope with. However, this can only occur as long the person being treated is open to learning and able to value the therapeutic process. 3 , 4

Lastly, a large body of evidence has indicated that PST can positively impact mental health, quality of life, and problem-solving skills in older adults. PST is an approach that can be implemented by different types of practitioners and settings (in-home care services, telemedicine, etc.), making mental health treatment accessible to the elderly population who often face age-related barriers and comorbid health issues. 1 , 5, 6

Top Rated Online Therapy Services

BetterHelp – Best Overall

“BetterHelp is an online therapy platform that quickly connects you with a licensed counselor or therapist and earned 4 out of 5 stars.” Take a Free Assessment

Talkspace - Best For Insurance

Talkspace accepts many insurance plans including Optum, Cigna, and Aetna. Typical co-pay is $30, but often less. Visit Talkspace

Problem-Solving Therapy Examples

Due to the versatility of problem-solving therapy, PST can be used in different forms, settings, and formats. Following are some examples where the problem-solving therapeutic approach can be used effectively. 4

People who suffer from depression often evade or even attempt to ignore their problems because of their state of mind and symptoms. PST incorporates techniques that encourage individuals to adopt a positive outlook on issues and motivate individuals to tap into their coping resources and apply healthy problem-solving skills. Through psychoeducation, individuals can learn to identify and understand their emotions influence problems. Employing rehearsal exercises, someone can practice adaptive responses to problematic situations. Once the depressed person begins to solve problems, symptoms are reduced, and mood is improved.

The Veterans Health Administration presently employs problem-solving therapy as a preventive approach in numerous medical centers across the United States. These programs aim to help veterans adjust to civilian life by teaching them how to apply different problem-solving strategies to difficult situations. The ultimate objective is that such individuals are at a lower risk of experiencing mental health issues and consequently need less medical and/or psychiatric care.

Psychiatric Patients

PST is considered highly effective and strongly recommended for individuals with psychiatric conditions. These individuals often struggle with problems of daily living and stressors they feel unable to overcome. These unsolved problems are both the triggering and sustaining reasons for their mental health-related troubles. Therefore, a problem-solving approach can be vital for the treatment of people with psychological issues.

Adherence to Other Treatments

Problem-solving therapy can also be applied to clients undergoing another mental or physical health treatment. In such cases, PST strategies can be used to motivate individuals to stay committed to their treatment plan by discussing the benefits of doing so. PST interventions can also be utilized to assist patients in overcoming emotional distress and other barriers that can interfere with successful compliance and treatment participation.

Benefits of Problem-Solving Therapy

PST is versatile, treating a wide range of problems and conditions, and can be effectively delivered to various populations in different forms and settings—self-help manuals, individual or group therapy, online materials, home-based or primary care settings, as well as inpatient or outpatient treatment.

Here are some of the benefits you can gain from problem-solving therapy:

- Gain a sense of control over your life

- Move toward action-oriented behaviors instead of avoiding your problems

- Gain self-confidence as you improve the ability to make better decisions

- Develop patience by learning that successful problem-solving is a process that requires time and effort

- Feel a sense of empowerment as you solve your problems independently

- Increase your ability to recognize and manage stressful emotions and situations

- Learn to focus on the problems that have a solution and let go of the ones that don’t

- Identify barriers that may hinder your progress

How to Find a Therapist Who Practices Problem-Solving Therapy

Finding a therapist skilled in problem-solving therapy is not any different from finding any qualified mental health professional. This is because many clinicians often have knowledge in cognitive-behavioral interventions that hold similar concepts as PST.

As a general recommendation, check your health insurance provider lists, use an online therapist directory , or ask trusted friends and family if they can recommend a provider. Contact any of these providers and ask questions to determine who is more compatible with your needs. 3 , 4

Are There Special Certifications to Provide PST?

Therapists do not need special certifications to practice problem-solving therapy, but some organizations can provide special training. Problem-solving therapy can be delivered by various healthcare professionals such as psychologists, psychiatrists, physicians, mental health counselors, social workers, and nurses.

Most of these clinicians have naturally acquired valuable problem-solving abilities throughout their career and continuing education. Thus, all that may be required is fine-tuning their skills and familiarity with the current and relevant PST literature. A reasonable amount of understanding and planning will transmit competence and help clients gain insight into the causes that led them to their current situation. 3 , 4

Questions to Ask a Therapist When Considering Problem-Solving Therapy

Psychotherapy is most successful when you feel comfortable and have a collaborative relationship with your therapist. Asking specific questions can simplify choosing a clinician who is right for you. Consider making a list of questions to help you with this task.

Here are some key questions to ask before starting PST:

- Is problem-solving therapy suitable for the struggles I am dealing with?

- Can you tell me about your professional experience with providing problem-solving therapy?

- Have you dealt with other clients who present with similar issues as mine?

- Have you worked with individuals of similar cultural backgrounds as me?

- How do you structure your PST sessions and treatment timeline?

- How long do PST sessions last?

- How many sessions will I need?

- What expectations should I have in working with you from a problem-solving therapeutic stance?

- What expectations are required from me throughout treatment?

- Does my insurance cover PST? If not, what are your fees?

- What is your cancellation policy?

How Much Does Problem-Solving Therapy Cost?

The cost of problem-solving therapy can range from $25 to $150 depending on the number of sessions required, severity of symptoms, type of practice, geographic location, and provider’s experience level. However, if your insurance provider covers behavioral health, the out-of-pocket costs per session may be much lower. Medicare supports PST through professionally trained general health practitioners. 1

What to Expect at Your First PST Session

During the first session, the therapist will strive to build a connection and become familiar with you. You will be assessed through a clinical interview and/or questionnaires. During this process, the therapist will gather your background information, inquire about how you approach life problems, how you typically resolve them, and if problem-solving therapy is a suitable treatment for you. 3 , 4

Additionally, you will be provided psychoeducation relating to your symptoms, the problem-solving method and its effectiveness, and your treatment goals. The clinician will likely guide you through generating a list of the current problems you are experiencing, selecting one to focus on, and identifying concrete steps necessary for effective problem-solving. Lastly, you will be informed about the content, duration, costs, and number of therapy sessions the therapist suggests. 3 , 4

Would you like to try therapy?

Find a supportive and compassionate therapist ! BetterHelp has over 20,000 licensed therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. BetterHelp starts at $65 per week. Take a Free Online Assessment and get matched with the right therapist for you.

Is Problem-Solving Therapy Effective?

Extensive research and studies have shown the efficacy of problem-solving therapy. PST can yield significant improvements within a short amount of time. PST is also useful for addressing numerous problems and psychological issues. Lastly, PST has shown its efficacy with different populations and age groups.

One meta-analysis of PST for depression concluded that problem-solving therapy was as efficient for reducing symptoms of depression as other types of psychotherapies and antidepressant medication. Furthermore, PST was significantly more effective than not receiving any treatment. 7 However, more investigation may be necessary about PST’s long-term efficacy in comparison to other treatments. 5,6

How Is PST Different From CBT & SFT?

Problem-solving, cognitive-behavioral, and solution-focused therapy belong to the cognitive-behavioral framework, sharing a common goal to modify thoughts, aptitudes, and behaviors to improve mental health and quality of life.

Problem-Solving Therapy Vs. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a short-term psychosocial treatment developed under the premise that how we think affects how we feel and behave. CBT addresses problems arising from maladaptive thought patterns and seeks to challenge and modify these to improve behavioral responses and overall well-being. CBT is the most researched approach and preferred treatment in psychotherapy due to its effectiveness in addressing various problems like anxiety, sleep disorders, substance abuse, and more.

Like CBT, PST addresses mental, emotional, and behavioral issues. However, PST may provide a better balance of cognitive and behavioral elements.

Another difference between these two approaches is that PST mostly focuses on faulty thoughts about problem-solving orientation and modifying maladaptive behaviors that specifically interfere with effective problem-solving. Usually, PST is used as an integrated approach and applied as one of several other interventions in CBT psychotherapy sessions.

Problem-Solving Therapy Vs. Solution-Focused Therapy

Solution-focused therapy (SFT) , like PST, is a goal-directed, evidence-based brief therapeutic approach that encourages optimism, options, and self-efficacy. Similarly, it is also grounded on cognitive behavioral principles. However, it differs from problem-solving therapy because SFT is a semi-structured approach that does not follow a step-by-step sequential format. 8

SFT mainly focuses on solution-building rather than problem-solving, specifically looking at a person’s strengths and previous successes. SFT helps people recognize how their lives would differ without problems by exploring their current coping skills. Community mental health, inpatient settings, and educational environments are increasing the use of SFT due to its demonstrated efficacy. 8

Final Thoughts

Problem-solving therapy can be an effective treatment for various mental health concerns. If you are considering treatment, ask your doctor for recommendations or conduct your own research to learn more about this approach and other options available.

Additional Resources

To help our readers take the next step in their mental health journey, Choosing Therapy has partnered with leaders in mental health and wellness. Choosing Therapy is compensated for marketing by the companies included below.

Online Therapy

BetterHelp – Get support and guidance from a licensed therapist. BetterHelp has over 20,000 therapists who provide convenient and affordable online therapy. Take A Free Online Assessment and get matched with the right therapist for you. Free Assessment

Online Psychiatry

Hims / Hers If you’re living with anxiety or depression, finding the right medication match may make all the difference. Connect with a licensed healthcare provider in just 12 – 48 hours. Explore FDA-approved treatment options and get free shipping, if prescribed. No insurance required. Get Started

Medication + Therapy

Brightside Health – Together, medication and therapy can help you feel like yourself, faster. Brightside Health treatment plans start at $95 per month. United Healthcare, Anthem, Cigna, and Aetna accepted. Following a free online evaluation and receiving a prescription, you can get FDA approved medications delivered to your door. Free Assessment

Starting Therapy Newsletter

A free newsletter for those interested in learning about therapy and how to get the most benefits out of therapy. Get helpful tips and the latest information. Sign Up

Choosing Therapy Directory

You can search for therapists by specialty, experience, insurance, or price, and location. Find a therapist today .

For Further Reading

- 12 Strategies to Stop Using Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms

- Depression Therapy: 4 Effective Options to Consider

- CBT for Depression: How It Works, Examples, & Effectiveness

Best Online Therapy Services

There are a number of factors to consider when trying to determine which online therapy platform is going to be the best fit for you. It’s important to be mindful of what each platform costs, the services they provide you with, their providers’ training and level of expertise, and several other important criteria.

Best Online Psychiatry Services

Online psychiatry, sometimes called telepsychiatry, platforms offer medication management by phone, video, or secure messaging for a variety of mental health conditions. In some cases, online psychiatry may be more affordable than seeing an in-person provider. Mental health treatment has expanded to include many online psychiatry and therapy services. With so many choices, it can feel overwhelming to find the one that is right for you.

Problem-Solving Therapy Infographics

A free newsletter for those interested in starting therapy. Get helpful tips and the latest information.

Choosing Therapy strives to provide our readers with mental health content that is accurate and actionable. We have high standards for what can be cited within our articles. Acceptable sources include government agencies, universities and colleges, scholarly journals, industry and professional associations, and other high-integrity sources of mental health journalism. Learn more by reviewing our full editorial policy .

Beaudreau, S. A., Gould, C. E., Sakai, E., & Terri Huh, J. W. (2017). Problem-Solving Therapy. In N. A. Pachana (Ed.), Encyclopedia of geropsychology : with 148 figures and 100 tables . Singapore: Springer.

Broerman, R. (2018). Diathesis-Stress Model. In T. Shackleford & V. Zeigler-Hill (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (Living Edition, pp. 1–3). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_891-1

Mehmet Eskin. (2013). Problem solving therapy in the clinical practice . Elsevier.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2013). Problem-Solving Therapy A Treatment Manual . Springer Publishing Company.

Cuijpers, P., et al. (2018). Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis. European Psychiatry 48 , 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.006

Kirkham, J. G., Choi, N., & Seitz, D. P. (2015). Meta-analysis of problem-solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry , 31 (5), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4358

Bell, A. C., & D’Zurilla, T. J. (2009). Problem-solving therapy for depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review , 29 (4), 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.003

Proudlock, S. (2017). The Solution Focused Way Incorporating Solution Focused Therapy Tools and Techniques into Your Everyday Work . Routledge.

Nezu, A. M., Nezu, C. M., & Gerber, H. R. (2019). (Emotion‐centered) problem‐solving therapy: An update. Australian Psychologist , 54 (5), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12418

We regularly update the articles on ChoosingTherapy.com to ensure we continue to reflect scientific consensus on the topics we cover, to incorporate new research into our articles, and to better answer our audience’s questions. When our content undergoes a significant revision, we summarize the changes that were made and the date on which they occurred. We also record the authors and medical reviewers who contributed to previous versions of the article. Read more about our editorial policies here .

Your Voice Matters

Can't find what you're looking for.

Request an article! Tell ChoosingTherapy.com’s editorial team what questions you have about mental health, emotional wellness, relationships, and parenting. The therapists who write for us love answering your questions!

Leave your feedback for our editors.

Share your feedback on this article with our editors. If there’s something we missed or something we could improve on, we’d love to hear it.

Our writers and editors love compliments, too. :)

FOR IMMEDIATE HELP CALL:

Medical Emergency: 911

Suicide Hotline: 988

© 2024 Choosing Therapy, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Types of Therapy Are Helpful for Depression?

What is psychotherapy, psychotherapy for depression.

- Therapy Approaches

- How Long Does It Take to Work?

- Choosing a Therapist

Depression is more than feeling sad or unmotivated for a few days; it’s an ongoing and persistent feeling of extreme sadness or despair affecting every aspect of a person’s life. Data from 2020 shows 18.4% of U.S. adults have received a diagnosis of depression.

Fortunately, treatment options like psychotherapy can be effective. The key is finding out what type of psychotherapy is right for you, depending on the severity of your symptoms, personal preferences, and therapy goals.

This article covers the most effective evidence-based psychotherapy treatments for depression.

The Good Brigade / Getty Images

Psychotherapy is talk therapy . It takes place in outpatient settings (i.e., therapy offices) and inpatient settings (i.e., hospitals). Its purpose is to help relieve symptoms and prevent them from returning.

Each form of psychotherapy is unique, but typical sessions help a person identify the thought patterns, learned behaviors, or personal circumstances that may be contributing to their depression. The focus then shifts to building healthy coping strategies for managing negative thoughts, unwanted behaviors, and difficult emotions or experiences.

The following are the most common types of psychotherapy for depression.

Cognitive Therapy

Cognitive therapy (also called cognitive processing therapy) is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy shown to be effective in helping people challenge and change unhelpful or unwanted beliefs or attitudes that result from traumatic experiences such as sexual assault or natural disaster.

Cognitive therapy involves learning about symptoms like intrusive thoughts resulting from traumatic experiences and working on processing the experience and questioning and reframing negative self-thinking.

Behavioral Therapy

Behavioral therapy (also called behavioral activation) focuses on how certain behaviors influence or trigger symptoms of depression. It works by helping a person identify and understand specific behavioral triggers and then providing behavioral activation exercises that encourage behavioral modifications or changes where possible, resulting in more positive mood outcomes.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT is considered the best-researched technique and the "gold standard" of psychotherapy. It's been shown effective in reducing depression symptoms and helping patients build skills to change thought patterns and behaviors to break them out of depression. It also encourages greater adherence to medications and other treatments.

CBT when combined with medication for depression has been shown more effective in treating symptoms and preventing relapse than pharmacology alone.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

DBT is a skilled-focused technique centered on acceptance and change. It involves acceptance-oriented skills, such as mindfulness and increasing tolerance to distress. It also uses change-oriented skills, emotional regulation (keeping emotions in check), and interpersonal development (i.e., saying no, asking for what you want, and establishing interpersonal boundaries).

Research suggests DBT is particularly beneficial for people experiencing chronic suicidal thinking .

Suicide Prevention Hotline

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, dial 988 to contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline and connect with a trained counselor. For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database.

Psychodynamic Therapy

Psychodynamic therapy is based on the theory that moods and behaviors are directly but unconsciously related to childhood and past experiences. It involves building self-awareness of these experiences and their influence on a person while empowering them to change unwanted patterns.

Treatment with psychodynamic therapy has been shown to be as effective as other treatments in reducing depressive symptoms in depressive disorders.

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT)

IPT focuses on how relationships impact mental health. It helps people manage and strengthen current relationships, as well as looking at how different environments influence thinking and behavior. Numerous studies support the effectiveness of ITP for depression treatment and symptom relapse prevention.

Problem-Solving Therapy (PST)

PST is about strengthening a person’s ability to cope with stressful events by enhancing problem-solving skills. Several studies support the effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for people with depression, depressive disorders, and other mental health conditions.

Approaches to Therapy for Depression

Therapy is not one-size-fits-all. The best approach will depend on severity of symptoms and overall therapy goals, and may include a combination of individual therapy, group therapy , family therapy , or couples therapy . Someone experiencing ongoing depression may benefit from the one-on-one support of individual therapy, but also from a family-based approach and peer support groups .

How Long Does Therapy for Depression Take?

The length of time therapy takes to experience results will vary depending on factors such as:

- Depression type: Acute depression (i.e. depression that does not persist over a long period of time) will typically take fewer sessions to show results than chronic depression.

- Symptom severity: More severe symptoms like suicidal thinking may require longer or more intensive treatment.

- Therapy goals: Focused goals are reached more quickly than broader-based goals.

- Session frequency: People are typically advised to attend as often as they feel comfortable, but more frequent sessions typically result in quicker results.

- Technique: Some types of therapy like cognitive behavioral therapy are more goal-focused and generally quicker than other types.

- Trust: Higher levels of trust between client and therapist often yield quicker results.

- Personal circumstances: A new or ongoing traumatic life experience or other health condition like substance use disorder may prolong how long treatment takes.

General Timeline

Psychotherapy can be short-term and last a few weeks to months (for situational acute depression) or long-term and last a few months to years (for persistent or chronic depression).

How to Choose a Technique and Therapist

Consider which types of therapy best align with your goals and seek a therapist who offers that type of therapy. Bear in mind that therapists may offer more than one technique and can help you determine which techniques may be most suitable.

When choosing a therapist, you may consider their credentials, such as if they have a medical degree and can prescribe medication for depression , as a psychiatrist can. It's crucial to choose a therapist whom you feel comfortable working with. It’s OK to attend a few sessions before deciding if they're the right therapist for you.

A Word From Verywell

Making sure you feel comfortable and have rapport with your therapist is one of the most important determinants for effective therapy. Set up short introductions or consultations with a few therapists so you can pick one you feel you can build the most rapport with.

There are many types of evidence-based therapy that are suitable for treating depression. Some involve working one-on-one with a therapist, and others may include family members, spouses, or peer groups experiencing depression. Making the correct choice includes determining your therapy goals and finding a therapist you feel comfortable working with.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National, state-level, and county-level prevalence estimates of adults aged ≥18 years self-reporting a lifetime diagnosis of depression — United States, 2020 .

Informed Health. Depression: How effective is psychological treatment?

American Psychological Association. Cognitive processing therapy (CPT) .

University of Michigan. Behavioral activation for depression .

Gautam M, Tripathi A, Deshmukh D, Gaur M. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression . Indian J Psychiatry . 2020;62( 2):S223-S229. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_772_19

Wersen AD, Meiser-Stedman R, Laidlaw K. A meta-analysis of CBT efficacy for depression comparing adults and older adults . Journal of Affective Disorders . 2022;319:189-20. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.020

University of Washington. Dialectical behavioral therapy .

American Psychiatric Association. What is psychotherapy?

Steinert C, Munder T, Rabung S, Hoyer J, Leichsenring F. Psychodynamic therapy: as efficacious as other empirically supported treatments? A meta-analysis testing equivalence of outcomes . AJP . 2017;174(10):943-953. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17010057

American Psychological Association. APA dictionary of psychology: interpersonal psychotherapy (ITP) .

Cuijpers P, Donker T, Weissman MM, Ravitz P, Cristea IA. Interpersonal psychotherapy for mental health problems: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry . 2016;173(7):680-687. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15091141

Zhang A, Park S, Sullivan JE, Jing S. The effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for primary care patients' depressive and/or anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis . J Am Board Fam Med . 2018;31(1):139-150. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170270

American Psychological Association. How long will it take for treatment to work?

By Michelle Pugle Michelle Pugle, MA is a freelance writer and reporter focusing on mental health and chronic conditions. As seen in Verywell, Healthline, Psych Central, Everyday Health, and Health.com, among others.

- CLASSIFIEDS

- Advanced search

American Board of Family Medicine

Advanced Search

The Effectiveness of Problem-Solving Therapy for Primary Care Patients' Depressive and/or Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- Figures & Data

- Info & Metrics

Background: There is increasing demand for managing depressive and/or anxiety disorders among primary care patients. Problem-solving therapy (PST) is a brief evidence- and strength-based psychotherapy that has received increasing support for its effectiveness in managing depression and anxiety among primary care patients.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials examining PST for patients with depression and/or anxiety in primary care as identified by searches for published literature across 6 databases and manual searching. A weighted average of treatment effect size estimates per study was used for meta-analysis and moderator analysis.

Results: From an initial pool of 153 primary studies, 11 studies (with 2072 participants) met inclusion criteria for synthesis. PST reported an overall significant treatment effect for primary care depression and/or anxiety ( d = 0.673; P < .001). Participants' age and sex moderated treatment effects. Physician-involved PST in primary care, despite a significantly smaller treatment effect size than mental health provider only PST, reported an overall statistically significant effect ( d = 0.35; P = .029).

Conclusions: Results from the study supported PST's effectiveness for primary care depression and/or anxiety. Our preliminary results also indicated that physician-involved PST offers meaningful improvements for primary care patients' depression and/or anxiety.

- Anxiety Disorders

- Depressive Disorder

- Mental Health

- Primary Health Care

- Problem Solving

- Psychotherapy

Depressive and anxiety disorders are the 2 leading global causes of all nonfatal burden of disease 1 and the most prevalent mental disorders in the US primary care system. 2 ⇓ – 4 The proportion of primary care patients with a probable depressive and/or anxiety disorder ranges from 33% to 80% 2 , 5 , 6 ; primary care patients also have alarmingly high levels of co-/multi-morbidity of depressive, anxiety, and physical disorders. 7 Depression and anxiety among primary care patients contribute to: poor compliance with medical advice and treatment 8 ; deficits in patient–provider communication 9 ; reduced patient engagement in healthy behaviors 10 ; and decreased physical wellbeing. 11 , 12 Given the high prevalence of primary care depression and anxiety, and their detrimental effects on the qualities of primary care treatments and patients' wellbeing, it is important to identify effective interventions suitable to address primary care depression and anxiety.

Primary care patients with depression and/or anxiety are often referred out to specialty mental health care. 13 , 14 However, outcomes from these referrals are usually poor due to patients' poor adherence and their resistance to mental health treatment 15 , 16 . Therefore, it is critical to identify effective mental health interventions that can be delivered in primary care for patients' depression and/or anxiety. 17 , 18 During the past decade, a plethora of clinical trials have investigated different mental health interventions for depression and anxiety delivered in primary care. One of the most promising interventions that has received increasing support for managing depression and anxiety in primary care is Problem-Solving Therapy (PST).

Holding that difficulties with problem solving make people more susceptible to depression, PST is a nonpharmacological, competence-based intervention that involves a step-by-step approach to constructive problem solving. 19 , 20 Developed from cognitive-behavioral-therapy, PST is a short-term psychotherapy approach delivered individually or in group settings. The generic PST manual 19 contains 14 training modules that guides PST providers working with patients from establishing a therapeutic relationship to identifying and understanding patient-prioritized problems; from building problem-solving skills to eventually solving the problems. Focused on patient problems in the here-and-now, a typical PST treatment course ranges from 7 to 14 sessions and can be delivered by various health care professionals such as physicians, clinical social workers or nurse practitioners. Because the generic PST manual outlines the treatment formula in detail, providers may deliver PST after receiving 1 month of training. For example, 1 feasibility study on training residents in PST found that residents can provide fidelious PST after 7 weeks' training and reach moderate to high competence after 3 years of practicing PST. 21 PST also has a self-help manual available to clients when needed.

PST is a well-established, evidence-based intervention for depression in specialty mental health care and is receiving greater recognition for its effectiveness in treating depression and anxiety in primary care. Systematic and meta-analytic reviews of PST for depression consistently reported moderate to large treatment effects, ranging from d = 0.4 to d = 1.15. 22 ⇓ – 24 Several clinical trials indicated PST's clinical effectiveness in alleviating anxiety as well. 25 , 26 Most importantly, PST has been adapted for primary care settings (PST-PC) and can be delivered by a variety of health care providers with fewer number of sessions and shorter session length. These unique features make PST(-PC) an ideal psychotherapy for depressive and/or anxiety disorders in primary care.

Previous reviews of PST focused on its effectiveness for depression care, but with little attention to PST's effect on anxiety or comorbid depression anxiety. In addition, to our knowledge, no previous reviews of PST have focused on managing depressive and/or anxiety disorders in primary care. Although research demonstrates that PST has a strong evidence base for treating depression and/or anxiety in specialty mental health care settings, more research is needed to determine whether PST remains effective for treating depressive and/or anxiety disorders when delivered in primary care. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of PST for treating depressive and/or anxiety disorders with primary care patients.

Search Strategies

This review included searches in 6 electronic databases (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, Medline, PsychINFO, PUBMED, and the Cochrane Library/Database) and 3 professional Web sites (Academy of Cognitive Therapy, IMPACT, Anxiety and Depression Association of America) for primary care depression and anxiety studies published between January 1900 and September 2016. We also E-mailed major authors of PST studies for feedback and input. Search terms of title and/or abstract searches included: [“PST” or “Problem-Solving Therapy” or “Problem Solving Therapy” or “Problem Solving”] AND [“Depression” or “Depressive” or “Anxiety” or “Panic” or “Phobia”] AND [“primarycare” or “primary care” or “PCP” or “Family Medicine” or “Family Doctor”]. We supplemented the procedure described above with a manual search of study references.

Eligibility Criteria

For inclusion in analyses, a study needed to be 1) a randomized-controlled-trial of 2) PST for 3) primary care patients' 4) depressive and/or anxiety disorders. For studies that examined face-to-face, in-person PST, the intervention must be delivered in primary care for inclusion. If studies examined tele-PST (eg, telephone delivery, video conferencing, computer-based), the intervention must be connected to patients' primary care services for a study to be included. For example, when a primary care physician prescribed computer-based PST at home for their patients, the study met inclusion criteria (as it was still considered managing depression “in primary care” in the present review). However, studies would be excluded if a primary care physician referred patients to an external mental health intervention. Finally, studies must document and report sufficient statistical information for calculating effect size for inclusion in the final analysis.

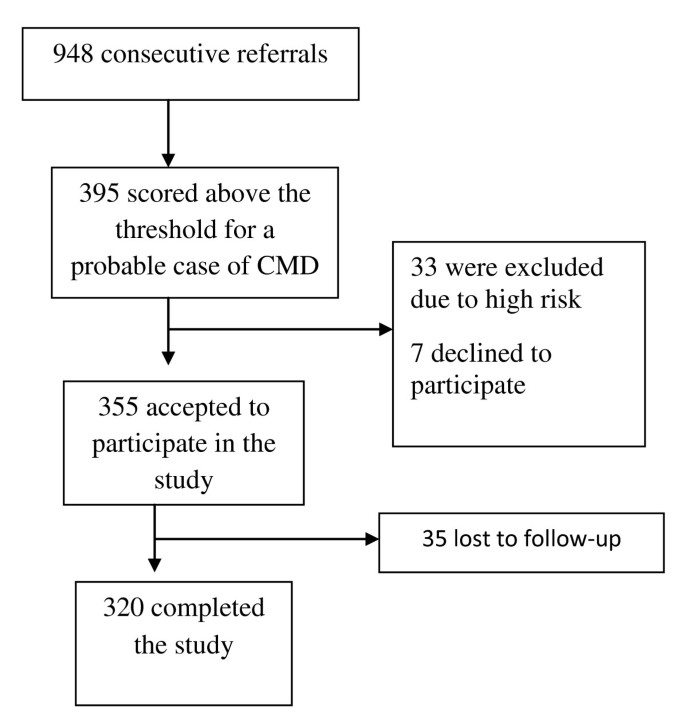

Data Abstraction and Coding

Two authors (AZ and JES) reviewed an initial pool of 153 studies and agreed to remove 65 studies based on title and 68 studies based on abstract, resulting in 20 studies for full-text review. To develop the final list, we excluded 6 studies after closer review of full-text and consultation with a third reviewer who is an established PST researcher. Lastly, we excluded 2 studies due to 1) a study with a design that blurred the effect of PST with other treatments and 2) unsuccessful contact with a study author to request data needed for calculating effect size. We used a final sample of 11 studies for meta-analysis. The PRISMA chart is presented in Figure 1 .

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) chart of literature search for Problem-solving therapy (PST) studies for treating primary care patients' depression and/or anxiety.

Statistical Analysis

This study conducted meta-analysis with the following procedures: 1) calculated a weighted average of effect size estimates per study for depression and anxiety separately (to ensure independence) 27 ; 2) synthesized an overall treatment effect estimate using fixed- or random-effects model based on a heterogeneity statistic (Q-statistic) 28 ; and 3) performed univariate meta-regression with a mixed-effects model for moderator analysis. 29 Although other more advanced statistical approaches allow inclusion of multiple treatment effect size estimates per study for data synthesis, like the Generalized Least Squares method 30 or the Robust Variance Estimation method 31 , this study employed a typical approach because of the relatively small sample and absence of study information required to conduct more advanced methods. Following procedures outlined by Cooper and colleagues 32 , we conducted all analyses with R software. 33 We chose to conduct analyses in R, rather than software specific to meta-analysis (eg, RevMan), because R allowed for more flexibility in statistical modeling (eg, small sample size correction). 34 Sensitivity analysis using Robust Variance Estimation did not significantly alter results estimated with the typical approach. And so this study presents results from only the typical approach for purposes of parsimony and clarity.

Publication Bias, Risk of Bias and Quality of Studies

To detect publication bias, we used a funnel plot of effect size estimates graphed against their standard errors for visual investigation. To evaluate risk of bias, we used the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials 35 and the Quality Assessment of Controlled Intervention Studies to evaluate study quality. 36

Primary Studies

Eleven PST studies for primary care depression and/or anxiety reported a total sample size of 2072 participants. Participants' age averaged 50.1 and ranged from 24.5 to 71.8 years old. Ten studies reported participants' sex with an average of 35.6% male participants across all studies. Seven studies (63.6%) reported participants' racial background with most identified as non-Hispanic white (83.6%). Other racial/ethnic groups were poorly reported for meaningful summary. Five studies used active medication as a comparison, including 3 studies that used both active medication and placebo medication. The rest compared PST with treatment-as-usual while 2 studies used active control group (eg, video education material). Four studies involved physicians in some component of intervention delivery. PCPs provided PST in 2 studies; supervised and collaborated with depression care manager in 1 study, and collaborated with a primary care nurse in another. Ten studies reported an average of 6 PST sessions ( M = 6.1) ranging from 3 to 12 sessions. All but 1 study (n = 10) used individual PST and 2 studies used tele-health modalities to provide PST. All studies used standardized measures of depression and anxiety. Examples of the most common measures included: PHQ-9, CES-D, HAM-D, and BDI-II. Table 1 presents a detailed description of study characteristics.

- View inline

Study Characteristics for Problem-Solving Therapy as Intervention for Treating Depression and/or Anxiety Among Primary Care Patients ( n = 11)

Publication Bias, Risk of Bias, and Quality of Studies

The funnel plot ( Figure 2 ) did not indicate any clear sign of publication bias. Risk of bias ( Table 4 ) indicated an overall acceptable risk across studies included for review with blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data most vulnerable to risk of bias. Quality of study assessment ( Table 5 ) indicated an overall satisfactory study quality with over half of studies (n = 6) achieving ratings of “Good” study quality.

Funnel Plot for Publication Bias in Problem-solving therapy (PST) Studies for Treating Primary Care Patients' Depression an/or Anxiety.

Meta-analysis and moderator analysis

Figure 3 presents a forest plot of treatment effects per study, including depression and anxiety measures. Table 3 presents subgroup analysis of overall treatment effect by moderator and Table 2 presents the results of meta-analysis and moderator analysis. Meta-analysis revealed an overall significant treatment effect of PST for primary care depression and/or anxiety ( d = 0.67; P < .001). Further investigation revealed no significant difference between the mean treatment effect of PST for depression versus anxiety in primary care ( d ( diff .) = −0.25; P = .317) while subgroup analysis revealed the overall treatment effect for anxiety was not significant ( d = 0.35; P = .226). Age was found to be a significant moderator (β 1 = 0.02; P = .012) for treatment outcomes, indicating that for each unit increase in participants' age, the overall treatment effect for primary are depression and/or anxiety are expected to increase by 0.02 (standard deviations). Neither participants' ethnic or racial backgrounds nor marital status significantly moderated the overall treatment outcome.

Forest Plot of PST Treatment Effect Size Estimates for Treating Primary Care Patients' Depression and/or Anxiety per Study.

PST for Treating Primary Care Patients' Depression and/or Anxiety; Results of Univariate Meta-regression

Results of Subgroup Analysis of Overall Treatment Effect (by Moderator) of PST for Treating Primary Care Patients' Depression and/or Anxiety

PST for Treating Primary Care Patients' Depression and/or Anxiety; Results of the Cochrane Collaboration's Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias *

Quality Assessment of Controlled PST Intervention Studies for Primary Care Patients' Depression and/or Anxiety ( n =11)

The overall treatment effect was not moderated by any treatment characteristics including: treatment modality (individual vs group PST), delivery methods (face-to-face vs tele-health PST), number of PST sessions and length of individual PST sessions. Subgroup analysis indicated an overall significant treatment effect of in-person PST ( d = 0.72; P < .001) but not of tele-PST ( d = 0.53; P = .097). However, the difference between the 2 was not statistically significant.

PST providers background and primary care physician's involvement significantly moderated the overall treatment effect size. Master's-level providers reported an overall treatment effect ( d = 1.57; P < .001) significantly higher than doctoral-level providers ( d = −1.33; P = .007). Both physician-involved and nonphysician involved PST reported significant overall treatment effect of PST for depression and/or anxiety in primary care ( d = 1.06; P < .001 and d = 0.35; P = .029, respectively). Moderator analysis further revealed that PST without physician involvement reported significantly greater treatment effects compared with physician-involved PST in primary care ( d = −0.71; P = .005). Results of subgroup and moderator analyses indicated that while the difference (in treatment effect) between physician and nonphysician involved PST in primary care were statistically significant, physician-involved PST was also statistically significant, thus practically meaningful.

Results of the study demonstrated a statistically significant overall treatment effect in outcomes of depression and/or anxiety for primary care patients receiving PST compared with patients in control groups. The outcome type—depression versus anxiety—failed to moderate treatment effect; only PST for depression reported a significant overall effect size. This could indicate that many studies primarily targeted depression and included anxiety measures as secondary outcomes. For this reason, we expect to find a greater treatment effect for primary care depression. It was unsurprising that treatment characteristics failed to moderate treatment effect size because most primary studies used PST-PC or its modified version; there was insufficient variation between studies (and moderators), yielding insignificant moderating coefficients.

Although delivery method did not moderate treatment effect reported in studies included in this review, significant effect was only reported by studies using face-to-face in-person PST but not by those with tele-PST modalities (n = 2). Although evidence for the effectiveness of tele-PST is established or increasing in a variety of settings 37 ⇓ – 39 most PST studies for primary care patients have used face-to-face, in-person PST. Our study further supported the use of face-to-face in-person PST for treating depression and anxiety among primary care patients. We recognize, however, that current and projected shortages in specialty mental health care provision, felt acutely in subspecialties such as geriatric mental health, necessitate more trials with PST tele-health modalities. 40

It is salient to note that, while nonphysician-involved PST studies reported significantly greater treatment effect than those involving physicians, PCP-involved studies also reported an overall significant effect size. Closer examination indicated that studies with physician-involved PST were either delivered by physicians or other nonmental health professionals (eg, registered nurses or depression care managers). Lack of sufficient PST training might explain the difference in treatment effect sizes being statistically significant. Yet, the fact that physician-involved PST studies reported an overall statistically significant effect size for primary care depression and/or anxiety suggested a meaningful treatment effect for clinical practice. When faced with a shortage of mental health professionals (eg, psychologists, clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors), our findings suggest physician-led or -supervised PST interventions could still improve primary care patients' depression and/or anxiety. Researchers are encouraged to further examine the treatment effect of PST delivered by mental health professionals in collaboration with primary care physicians.

This study has several weaknesses that are inherent to meta-analyses. There is no way to assure we included all studies despite adopting a comprehensive search and coding strategy (ie, file drawer problem). Second, while all studies in this meta-analysis seemed to have satisfactory methodological rigor, it is possible that internal biases within some studies may influence results. This study takes a quantitative meta-analysis approach which inherently neglects other study designs and methodologies that also provide valuable information about the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of PST for treating primary care patients with depression. To ensure independence of data, this study used a weighted average of effect size estimates per study in synthesizing an overall treatment effect and conducting moderator analysis. While sensitivity analysis did not reveal significant differences from the reported results, we will not know for sure how our choice of statistical method might affect the results.

- Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Namkee Choi, Professor and the Louis and Ann Wolens Centennial Chair in Gerontology at the University of Texas at Austin Steve Hicks School of Social Work, for her mentorship and insightful comments during preparation of the manuscript.

This article was externally peer reviewed.