ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Leading trauma-informed education practice as an instructional model for teaching and learning.

- Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Advances in trauma-informed practices have helped both researchers and educators understand how childhood trauma impacts the developmental capacities required for successful learning within school. However, more investigation is required to understand how leaders can implement trauma-informed practices in targeted areas of their schools. This paper is a case study of one school who intentionally implemented a trauma-informed instructional practice approach after undertaking trauma informed positive education professional learning over a period of two and a half years. The research was guided by three questions: how are students supported in their learning and wellbeing; how can teachers be supported to develop consistent trauma-informed practice in their classrooms; and what is the role of leadership in this process? To research the approach, quantitative measures of staff and student perceptions and qualitative strategies centering the voices and experiences of students, teachers, and school leaders, were employed. Implications for school leaders suggest that when implemented as a whole-school approach through multiple and simultaneous mechanisms, trauma-informed positive education instructional practices have the possibilities of yielding enhanced outcomes for wellbeing and enable students to be ready to learn.

Introduction

Trauma-informed practices for teaching and learning require further exploration to better understand the ways in which school leaders can effectively implement and sustain trauma-informed practice as a whole-school approach to enhance both wellbeing and learning. Building upon the longstanding evidence of lineages such as social emotional learning (SEL; see for example Durlak et al., 2011 ) and the growing evidence base for trauma-informed educational practices ( Berger, 2019 ), these advances have been shown to have positive impacts on social and emotional student capabilities. The aim is to expand the field to consider how trauma-informed practices can enhance instructional outcomes. Relevant literatures contributing to a school’s trauma-informed instructional approach are drawn together, including: trauma-informed education practices; positive education; leading instruction; and professional learning.

The research (funded by Berry Street and the Brotherhood of St Laurence) is drawn from a secondary school that was experiencing difficulty with their delivery of learning and wellbeing outcomes for students (evidenced by their standardized testing and teacher judgment results as well as student responses to the Attitudes to School Survey (AtoSS). Their journey was followed to implement a trauma informed instructional approach. This is the first two and a half years of that journey where the focus has been on student wellbeing and assisting students to be ready to learn. The contention is that through the intentional application of whole school strategies by school leadership, trauma-informed instructional models de silo traditional SEL approaches. Doing this enables the incorporation of knowledge of trauma’s negative impacts on child development and to enact proactive strategies to enhance student engagement with learning. This knowledge is then deliberately applied to multiple aspects of school’s instructional model. In short, trauma-informed instructional practices can help students and their teachers get ready to learn .

Trauma-Informed Education Practice

Trauma-informed education helps teachers understand the impacts of trauma and suggests proactive strategies to position the school itself as a predictable milieu for healing and growth. Broadly speaking, trauma is an adverse experience that compromises an individual’s sense of being safe in relationships and in the world around them; and can significantly inhibit both self-regulatory and relational capacities required for successful learning ( Brunzell et al., 2015 ). After a traumatic event or a series of events, it is normal for children to experience fear, stress and a heightened state of alertness ( Shonkoff et al., 2012 ). With simple trauma, these experiences tend to be brief, often occurring only once. However, complex relational trauma occurs over time and can be repeated often by someone known to the child. When children experience complex trauma, the effects are profound, multiple and not always well understood ( Van der Kolk, 2005 ; Bath, 2008 ). Throughout the pandemic incidences of complex trauma have increased with ongoing financial insecurity, lack of social connectedness and a rise in family violence ( Wilkins et al., 2021 ). This has manifested in young people’s mental health with record levels of mental health issues being recorded for both children and young people ( Brennan et al., 2021 ).

Complex trauma can present as a risk to children’s cognitive functioning in ways that are apparent from late infancy ( Cook et al., 2005 ). These effects include delays in developing receptive and expressive language, problem solving skills, attention span, memory and abstract reasoning ( Cook et al., 2005 ; Shonkoff et al., 2012 ). As would be expected, cognitive deficits such as these adversely affect children’s academic outcomes. Studies demonstrate that individuals who report adverse childhood experiences are 2.5 times more likely to experience difficulties at school ( Anda et al., 2006 ). Such difficulties are multiple and include low achievement, participation in special support programs, early drop out, suspension and expulsion ( Cook et al., 2005 ; Anda et al., 2006 ; Porche et al., 2016 ).

These neurological impacts of trauma have important implications for children’s relationships with teachers and other adults in school settings. In childhoods characterized by supportive, attentive parents, adults can act as a mediator, helping children to respond to dangers and the effects of trauma ( Van der Kolk, 2005 ). However, when a child presumes adults to be a threat and has difficulty forming attachments, it creates significant barriers for teachers and other professionals to assume a supportive role. The combination of these effects makes it more difficult for children impacted by trauma to independently form healthy relationships with peers and moderate their emotions in the classroom ( West et al., 2014 ).

Aside from home, school is the place where the majority of children spend most time, highlighting the importance of making it a safe space ( Downey, 2012 ; Costa, 2017 ). Feeling connected and having a sense of belonging to school are important protective factors for children ( Resnick et al., 1997 ). It cannot be assumed, however, that schools will provide a sense of safety for children contending with trauma’s impacts.

Due to the challenging behaviors that children sometimes present, schools and teachers may adopt a punitive approach in regard to their interactions with these children ( Hemphill et al., 2014 ; Howard, 2019 ) that ignore a child’s complex history ( Costa, 2017 ).

In order to support children to meet their needs for safety at school, teachers should be supportive, caring, and avoid acting in ways that might trigger the child and produce power-laden behavioral responses like bullying ( Bath, 2008 ; Shonkoff et al., 2012 ; Carello and Butler, 2015 ). To successfully support children, teachers require training about trauma and exposure to risk and how it is expressed by children ( Day et al., 2015 ; Berger, 2019 ; Stokes and Brunzell, 2019 ). This has implications for whole-school implementation, making it vital that teachers be supported through professional learning to understand how to identify risk and how to respond in proactive ways.

A Trauma-Informed Positive Education Approach to Teaching

From the paradigm of positive psychology and allied wellbeing sciences, positive education is the application of positive psychology interventions appropriate for use by a teacher in the classroom and is primarily concerned with improving an individual’s sense of social and emotional wellbeing. It aims to contribute to their hopefulness, optimism for the future and wellbeing ( Line Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000 ). Dodge et al. (2012) describe wellbeing as a fluid phenomenon that can be subject to change as children experience challenges and setbacks that unsettle their perceptions that all is okay with their world. In order to maintain a sense of equilibrium in their wellbeing, it is necessary for children to draw upon social and emotional capacities. This becomes more difficult for children who have experienced trauma ( Mashford-Scott et al., 2012 ).

Positive education, that includes a focus on strategies to increase student wellbeing, then ensures that educators remember that strengths reside in every one of their students ( Seligman et al., 2009 ). Put briefly, strength-based approaches aim to capitalize and build on children’s existing psychological strengths and positive dispositions ( Alvord and Grados, 2005 ).

Trauma informed positive education (TIPE) is one such approach using positive education strategies that was developed to meet dual concerns within the classroom for healing and growth ( Brunzell, 2017 , 2021 ). The development of the TIPE model was based upon a systematic literature review of trauma-aware practice models (see de Arellano et al., 2008 ; Perry, 2009 ; Wolpow et al., 2009 ) and of the student wellbeing literature (see Peterson and Seligman, 2004 ; Cornelius-White, 2007 ; Waters, 2011 ).

The TIPE model is based on developmental strategies focused on three trauma-informed positive education aims: (1) to build the self-regulatory capacities of the body and emotions, (2) to support students to build their relational capacity and experience a sense of relatedness and belonging at school, and (3) to integrate wellbeing principles that nurture growth, identify strengths and build students psychological resources ( Brunzell and Norrish, 2021 , p. 66). TIPE was developed as a pedagogical practice model for teachers to assist teachers in supporting trauma-affected students. The three developmental aims were developed to strengthen teacher practice through an understanding of the underlying causes of student resistance and other concerning classroom behaviors ( Brunzell et al., 2015 ) (see section “Materials and Methods” for an explanation of the TIPE professional learning model that has been delivered in schools). In an evaluation of the TIPE model when implemented in schools ( Stokes and Turnbull, 2016 ), it was found to have most impact on student learning and wellbeing when incorporated into everyday classroom routines rather than being confined to the delivery of pastoral care and home group sessions.

Leading Instructional Practices and the Role of Professional Learning

There has been ongoing interest in what educational leaders do to successfully lead their schools, both in learning and wellbeing as interconnected priorities. Whilst the impact of school leadership on student learning has been noted as difficult to measure ( Robinson and Gray, 2019 ), there is general acceptance by educators that leadership is important to student outcomes ( Leithwood et al., 2019 ). As noted by Dinham (2008) school leaders create the conditions for teachers to teach effectively and learning to take place. Equally, the impact of leadership on student wellbeing has also been difficult to measure, but the connection between learning and wellbeing is clear with the quality and design of student learning environments impacting on student wellbeing, engagement and retention ( Catalano et al., 2004 ; Bond et al., 2007 ). Many researchers have sought to propose a relationship between student attitudes, student wellbeing and academic achievement (see for example Seligman et al., 2009 ). This is aligned with the current Framework for Improving Student Outcomes (FISO 2; Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training [VIC DET], 2022b ) that places both learning and wellbeing at the center of school improvement.

Robinson et al. (2008) conducted meta-analysis research on the impact of leadership on student outcomes (as a measure of success). They note that an instructional leader focuses on specific pedagogical work of teachers in the classroom. This enables the principal to have influence over what is happening with learning and wellbeing in the classroom while not actually being in the classroom ( Wahlstrom and Seashore-Louis, 2008 ). To be an instructional leader there are some key practices to enact. While these practices have been developed from a range of research in all schools, they are equally relevant for leaders in trauma affected schools. These practices include creating an orderly and supportive environment in the classroom ( Robinson et al., 2008 ); ensuring the quality of teaching through implementing a coherent instructional framework and the monitoring of student outcomes using evidence. Another important practice is to resource strategically and to understand both teacher and student time as a finite resource ( Robinson et al., 2008 ) with the enabling of on-task learning is a valuable way to effectively use this resource.

Another key leadership practice identified by Robinson and Gray (2019) to influence student outcomes is the leadership of teacher learning and development. Robinson and Gray (2019) relate this leadership practice to the learning needs of students. Trauma informed professional learning extends this leadership practice to both the learning and wellbeing needs of students ( Berger, 2019 ; Stokes and Brunzell, 2019 ). Stokes and Turnbull (2016) comment that professional learning in trauma-informed practice assists leaders and teachers to acknowledge the need for alternative instructional approaches to address the needs of students from trauma affected backgrounds. This responds to an issue faced in trauma affected schools, that of teachers experiencing professional burn out when unable to successfully teach vulnerable students ( Sullivan et al., 2014 ).

To ensure that both leaders and teachers engage in professional learning that can change their practice, professional learning must include more than just delivery of content. Underpinning the leadership of teacher learning and development are characteristics that Thompson et al. (2020) contend will lead to effective professional learning. These include: the building of trust; subject matter that is relevant; a sustained duration of programs; opportunities for teacher reflection and personalized support to individual learning needs.

Materials and Methods

This study draws on a larger 4-year longitudinal study of the implementation of trauma-informed education in three schools in Victoria, Australia, that is still being undertaken. The research is guided by three questions: how are students supported in their learning and wellbeing; how can teachers be supported to develop consistent trauma-informed practice in their classrooms; and what is the role of leadership in this process? All three schools received professional learning in the TIPE model (see the process outlined at the end of this section).

One school was selected and studied in depth because of the particular work they had done to intentionally implement a trauma-informed instructional approach based on their school context. A case study approach is used as the design for this study to focus upon depth rather than breadth ( Denscombe, 2003 ). As previously noted by their leaders, the school had longstanding difficulty delivering successful learning and wellbeing outcomes for their students. Therefore, the change in practice could be clearly followed once the initial professional learning had been delivered then sustained at the school. In addition to this, the school was able to share school data from the first 3 years (2019–2021) that enabled quantitative and qualitative perspectives to be gathered on the changes that had occurred over time.

Permission to conduct the research was granted through the University of Melbourne’s Human Ethics Advisory Committee (HEAC no. 1955892.1) and the State Government of Victoria’s Department of Education (DET). Because of COVID related lockdowns and remote learning in 2020 and 2021, all research in schools was suspended for periods of time. An exemption to the suspension was granted by DET for data collection in this study at different periods throughout 2020 and 2021, but this limited the original planned data collection (two sets of interviews were planned for each year) over 2020 and 2021.

It is a descriptive case study describing an intervention and the real-life context in which it has occurred ( Stake, 1995 ). The investigation of the implementation of trauma-informed instructional practices was from 2019 to 2021, using multiple sources of data from one secondary school and so binding the case by time and activity ( Baxter and Jack, 2008 ). As Baxter and Jack (2008) note, case study research can integrate both qualitative (interviews) and quantitative (surveys) data to enhance the understanding of what is being studied. Of importance is the convergence of these sources in the analysis ( Baxter and Jack, 2008 ) to add strength and credibility to the findings. The description of the implementation of trauma informed instructional practices, while a case of one school, provides findings that may be relevant to other school and educational settings ( Stake, 1995 ).

Student and Family Context

The school participating in this study is situated in a suburb approximately 50 km from the state’s metro center. It is a suburb that has high levels of financial disadvantage and low levels of educational achievement. In 2016, the unemployment level in the region was 13.2% compared the Victorian average of 6.6% and national average of 6.9% ( Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020 ). The area ranks in the five most disadvantaged postcodes within the state out of 667 state postcodes ( Vinson et al., 2015 ). Of students in this school, 68% were rated as being in the lowest 25% of the Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA), a measure of socio-economic status highlighting the socio-economic disadvantage experienced by many of their students ( Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2020 ). Approximately 75% of students have or have had Department of Human Services (DHS) involvement within their family.

Staffing Composition

Of the 34 teachers in the school, 56% are graduate and early career teachers with 14.5% less of this group with than 5 years of experience, 22% are graduates and 19.5% are pre graduates including Teach for Australia and those with permission to teach. Twelve percent of teachers have between 5 and 10 years of experience and 32% have greater than 10 years of experience.

Research Tools and Analytical Strategies

Both quantitative and qualitative data was gathered from the school. Because of Department of Education research restrictions in schools, related to COVID-19, interview data was only collected in 2021. Overall, 32 interviews were conducted (leadership N = 4, teachers N = 6, educational support staff N = 2, students N = 20; years 7–12). The principal provided the research team with 3 years of VIC DET surveys from 2019 to 2021. These surveys were:

The School Staff Survey (SSS) ( Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training, 2021 ) 1 . This was completed by the majority of staff (2019: N = 35, 2020: N = 30, 2021: N = 34).

The AtoSS Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training [VIC DET] (2022a) 2 . This was completed by the students [2019: N = 192 (59%), 2020: N = 256 (81%), 2021: N = 260 (83%)].

Relevant areas have been drawn on from both surveys that relate to the research study.

Data Analysis

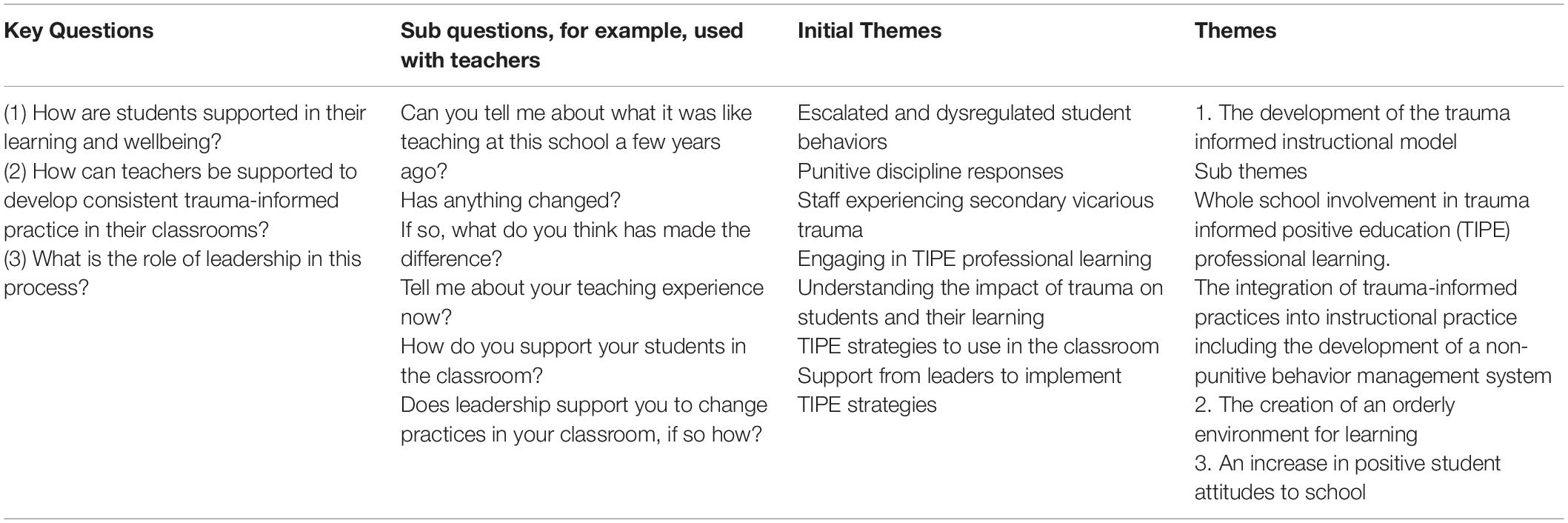

The framework from Miles and Huberman (1994) was used to analyze the data from the interviews with leaders, teachers, educational support staff, and students. This framework follows a four-step process: data reduction, data display, identifying themes, and verifying conclusions. In the data reduction stage, the interviews were coded from each group of participants using the research questions as an initial guide (see Table 1 for an example of the overall research questions, the sub questions for teachers and the initial coding of responses). The data display stage with the themes from all four groups was displayed to look for patterns and interrelationships. This allowed for higher order themes (such as the development of the trauma informed instructional model ) to emerge as the data from all four groups, contributed to the analysis. Finally, using step four of Miles and Huberman (1994) framework, verifying conclusions, the confirmability of the data was analyzed with reference to the literature ( Miles and Huberman, 1994 , p. 11).

Table 1. Summary of key questions and themes.

From this process, three overarching themes and two sub themes emerged. See table below. These themes are used to structure the following sections where the data is presented and discussed.

The Trauma Informed Positive Education Professional Learning Model

The school undertook professional development in trauma-informed positive education ( Brunzell et al., 2015 ) from mid 2019 to 2021. This included four whole days of training for all staff including leadership and then further master classes (conducted face to face when possible and online) in 2021 as well. Also integrated within the third year (2021) was a coaching program for individual teachers with support from senior leaders.

Each of the four training days on the five domains of TIPE and subsequent staff implementation and reflection on the implementation were all facilitated and supported by the TIPE trainer.

The 4 days of training (underpinned by the three TIPE aims as outlined in the literature) focused on the domains of:

• Body, a suite of mindsets, strategies and interventions that help students to develop their self-regulatory capacities (Day 1);

• Relationship, supporting teachers to form strong and nurturing relationships to assist students to heal, grow and learn (Day 2);

• Stamina, supporting students to sustain effort in the classroom, and to demonstrate perseverance and resilience in learning (Day 3);

• Engagement, pathways to cultivate student interest, curiosity, flow and positive emotions in the classroom (Day 3); and

• Character, building psychological strengths through crafting conversations with children about what they value and do well (Day 4) ( Brunzell and Norrish, 2021 , pp. 67–71).

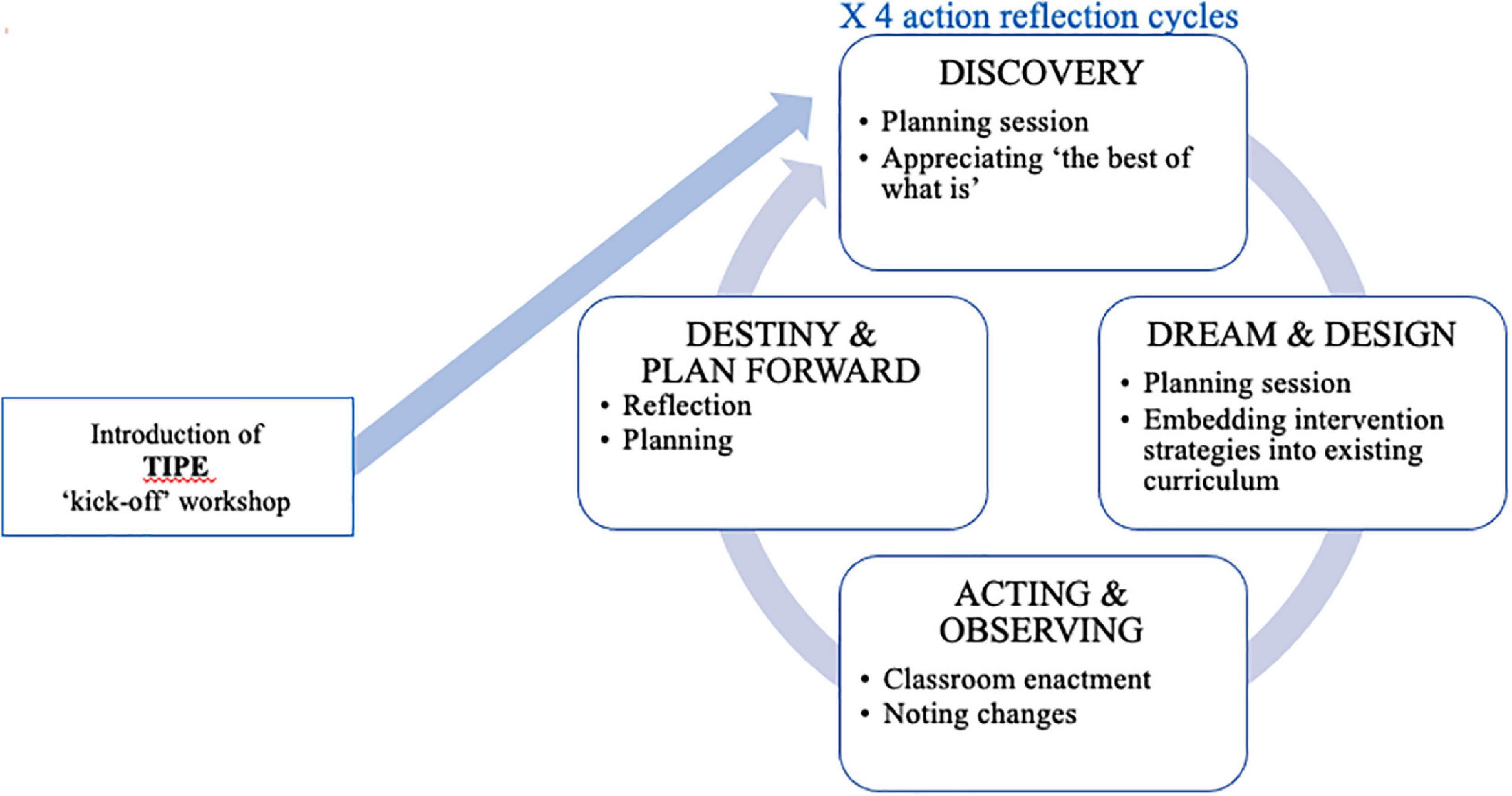

The 4 days followed an Appreciative Inquiry Participatory Action Research Cycle (AIPARC) ( Ludema and Fry, 2008 ; see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. TIPE appreciative inquiry participatory action research cycle (adapted from Brunzell, 2019 , p. 33).

Initially staff were guided through the Discovery phase as they developed a trauma-informed positive education lens through which to understand their students’ behaviors and needs.

In the Dream and Design phase staff generated and revised a question of their own to ensure that their future actions within leadership and in the classroom were meeting the current needs of their students. This involved reframing a deficit based question (i.e., How do I fix the aggressive behaviors in my classroom? ) to an “unconditional positive question” (i.e., What strategies can I use to increase a culture of relational density in my classroom?) . Using an “unconditional positive question” opens up new alternatives for transformation ( Ludema et al., 2006 , p. 155). Teachers at this school most commonly questioned: How can I support my classroom to stay on task? How can I get [student] to ignore distractions and complete his work?

As part of the Design phase , leaders, teachers and educational support staff co-created strategies (four different training days for the five domains) to enact in the classroom. These included: Domain 1 Body: providing effective alternatives to exclusion when students needed to self-regulate when escalated; Domain 2 Relationships: de-escalating students through proactive relational connection; Domain 3 Stamina: taking a strengths-based approach to restorative conversations to facilitate the student back to on-task, in-classroom learning; Domain 4 Engagement: Ways to cultivate student interest, curiosity, flow and positive emotions in the classroom; and Domain 5 Character: Building psychological strengths through crafting conversations with children about what they value and do well.

The Acting and observing phase involved the further refinement of whole school strategies by leadership in consultation with teachers. Teachers then implemented the strategies in the classroom with support from the leadership team.

On the next training day, the staff undertook reflection and future planning at the beginning of the training day in the Destiny and Plan Forward phase of the AIPAR cycle prior to moving to the next domain.

Findings and Discussion

As a unified effort, the school featured in this case study implemented trauma-informed education with it strategically positioned within its instructional practice. As Overstreet and Chafouleas (2016) note aligning trauma informed practices with ongoing educational practices can assist in the implementation of these practices into the school. This includes the incorporation of the knowledge of trauma’s negative impacts on child development and learning along with proactive trauma-informed strategies to be deliberately applied to multiple aspects of a school’s instructional model.

The research was undertaken at a school which had high levels of teacher absenteeism/turnover and low moral as well as low student outcomes (both academic and wellbeing). Leadership in the school acknowledged that teachers required a significant shift to their instructional practice and a wholesale change in the way they worked together to improve student outcomes. At the stage of this research, the school, while having undertaken all the TIPE professional learning, was working consistently within the first three domains of Body , Relationship , and Stamina . This is reflected in the responses from leaders, teachers and students. The following section provides evidence for the school moving from being trauma-affected to trauma-informed; and outlines the instructional elements that were implemented at the school along with discussion of the preliminary outcomes from those elements including the creation of an orderly learning environment and positive student outcomes.

Development of a Trauma Informed Instructional Model

From 2019–2021, the school leadership has taken steps to develop a trauma informed instructional model. This involved two key elements:

• Whole school involvement in TIPE professional learning (see in “Materials and Methods” for the outline of this process)

• The integration of trauma-informed practices into instructional practice including the development of a non-punitive behavior management system

Whole School Involvement in Trauma Informed Positive Education Professional Learning

The whole school involvement in TIPE professional learning over a sustained period of time enabled the leadership and teachers to work together on issues that were facing the school. Robinson (2011) describes effective teacher learning as one that includes all staff who have responsibility for instruction in the school to facilitate a shared responsibility for creating an effective climate for learning. This includes the participation of school leaders in the professional learning which as a leadership practice, has one of the biggest impacts on improving student outcomes ( Robinson et al., 2008 ).

Initially teachers spoke about their understandings of students impacted by trauma. One of the teachers describes the lives of some of the students that she taught.

I think everything is a struggle. Then when you throw in home life and those past traumas, or current traumas, in with being behind in the education, it just explodes into its own little world of understanding why these students react the way they do at times.

A school leader described the difficulty for new teachers or teachers who had not had experience working with children who are impacted by trauma:

They can’t really see the, the bottom of the iceberg. They’re only seeing what they see at the surface level stuff, they don’t really see what’s actually going on.

The school’s youth worker described what it was like before teachers understood the impact of trauma:

I don’t think staff were as equipped to do certain things, both teachers and wellbeing. I just think their training in certain areas, for understanding trauma-informed stuff, their empathy for certain things just wasn’t as good, and it just gave more of this kind of, it was much more of a hectic, uncontrolled - like a hectic energy.

Robinson (2011) comments that having leadership involved in professional learning allows the leaders to understand the challenges the teachers are facing in their context. This understanding was witnessed when one leader commented on the importance of teachers understanding the impact of trauma and how the training assisted with this:

Understanding the background of trauma and how that can manifest itself in so many different ways for a child. The willingness of staff to work through this and not just go, that’s a naughty kid.

The school staff then went on to describe the TIPE professional learning. One teacher described the 4 days of training which sustained their professional engagement with this instructional approach from mid 2019 – mid 2021 (at time of data collection) and how they transferred this learning to the classroom. As Wiliam (2014) notes teachers must be supported to develop their practice which in this case is trauma informed practice.

Yeah, 4 days spread out and so we’ve had time to - we unpack one domain, talk about I guess the reasons behind it, what it looks like in a classroom, all that sort of thing. Then we have time to implement that before we go into day two.

Another teacher described the training in more detail:

My initial training was coming in and doing it as a whole school training, so where we met as a staff, we spent a whole day learning about what are the areas and practicing. So, we would practice strategies you could use in the classroom, so we’d go through a role play.

To have an impact professional learning must be sustained ( Knapp, 2003 ; Thompson et al., 2020 ). The implementation of all the strategies was an ongoing process of learning and trialing for teachers. One teacher commented that this would take some time to put in place:

I think it is a lot to learn straight away and because we’ve only really had the couple of sessions on teaching it to the staff and - it’s been a lot to take in. I think it will probably take us another little while to get everyone’s heads around it and everyone doing it consistently in the classes and everyone using brain breaks and things like that.

School leadership then developed processes to assist staff (in between the training days) to effectively implement the TIPE model of instructional practice in their classrooms. They developed a coaching process that incorporated feedback after brief observation in the classroom which as Bishop et al. (2012b) note encourages teachers to be more aware of their classroom practice and assists teachers to understand why they are making changes to their practice ( Bishop et al., 2012a ). Two of the leaders talked about the support they were giving staff through a coaching process focused on using trauma-informed positive education strategies. Leaders supported teachers to work together and create consistent “welcome to class slides” projected at the beginning of all classes in their year-level to ensure the same trauma-informed language was used consistently to begin the lesson:

So, we just go into the class, talk about the entry routine, the slides at the start [requesting their students to ‘find your center , breathe, and start independent reading’], or talking about those things at the start. Then, together we use those Ready to Learn Plans [defined in the sections below], find those micro-moments when a kid is escalating, being able to actually see that. Then we just give them quick feedback after we go into the class. Three positives that we saw and one thing to consider. So, it’s that, straightaway that feedback.

Another leader described what they do to encourage teachers to reflect and change their practice:

We’re just going in and observing for 10–15 min and then sending an email to the staff member that says three things that they did that were great and aligned with those practices, one thing that they can consider working on and then we repeat. So, the idea is to try and not make it too laborious so that we get in lots and we can give lots of feedback.

These ongoing sessions with individual teachers target the individual learning needs of the teachers and as Thompson et al. (2020) note, support the teachers through a personalized approach.

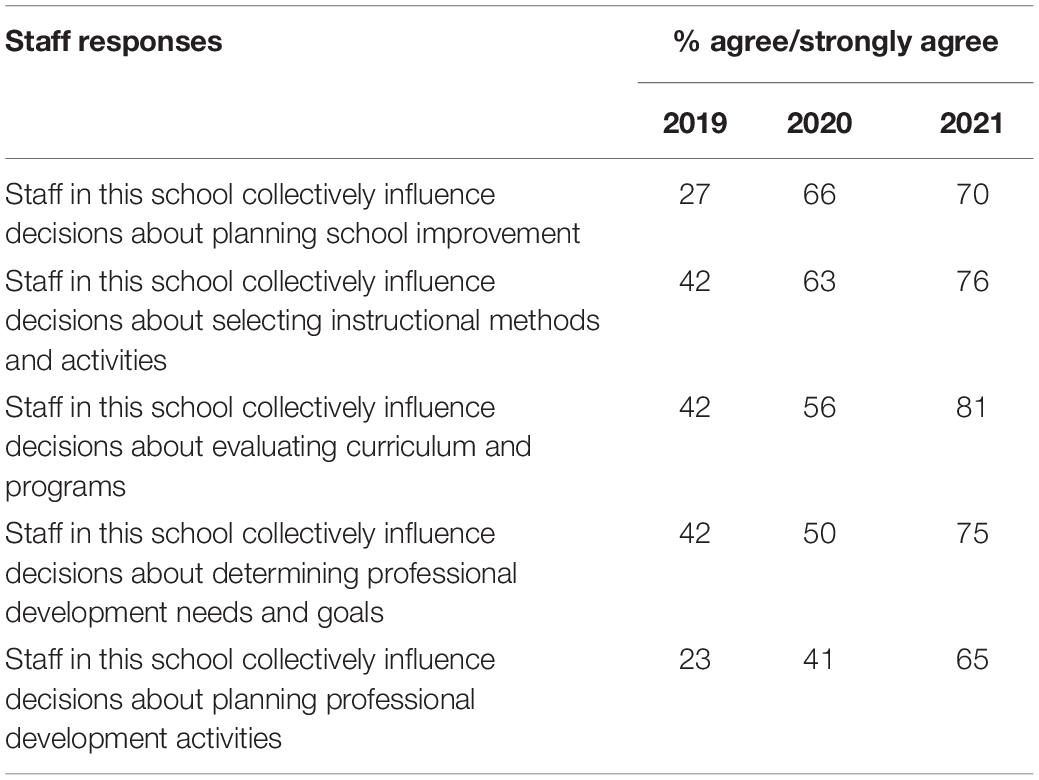

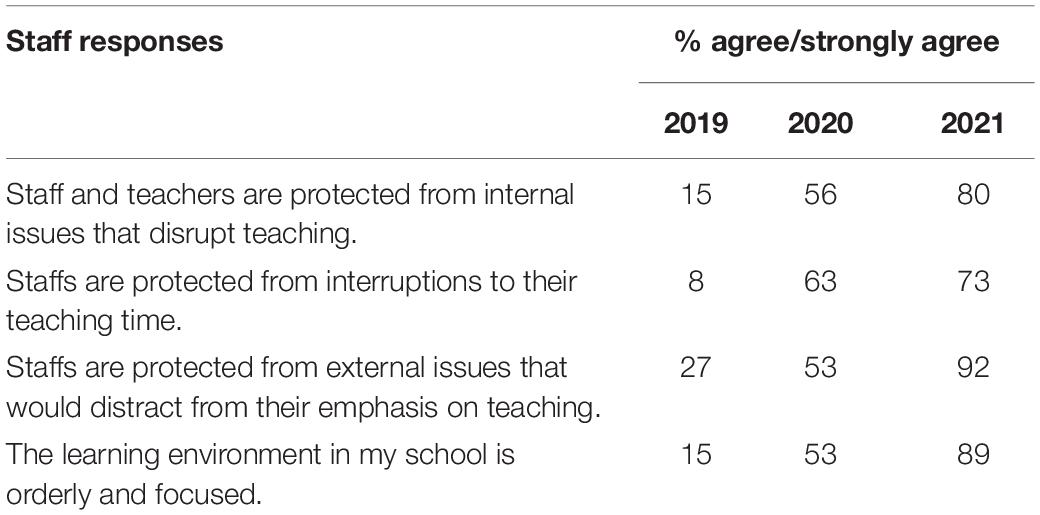

As shown in Table 2 , the changes in the School Staff Survey reflect the delivery of TIPE professional learning that encourage the co-creation of activities so that teachers could personalize the learning for their classrooms.

Table 2. School staff survey – teacher collaboration in school planning.

The Integration of Trauma-Informed Practices Into Instructional Practice

Social and emotional learning programs have primarily focused on improving wellbeing outcomes ( Durlak et al., 2011 ) while instructional practices have focused on improving learning outcomes ( Dinham, 2016 ). Providing trauma-informed positive education as an instructional approach in both the classroom and across the whole school enables both wellbeing and academic outcomes for students ( Stokes and Turnbull, 2016 ). Aligning trauma-informed practices with ongoing instructional practices can bolster teacher implementation of trauma-informed practices into the school ( Overstreet and Chafouleas, 2016 ).

In many of the interviews, staff members commented that in the past they were losing instructional time due to multiple critical incidents occurring both inside and outside of the classroom each day. These incidences were often in the form of violent outbursts or escalations that would derail the delivery of instruction—and wasted precious instructional time. As a result of the TIPE professional learning and the clear direction of leaders (following consultation with teachers and educational support staff) decisions were made to implement a range of TIPE strategies adapted to their own school context. The instructional model changed over time and contained classroom strategies and practices that assisted students to learn skills to build networks of support, feel confident as learners and manage difficult and challenging emotions when learning.

At a whole school level, the leaders made decisions to implement a non-punitive response to behavior management. This was based on the TIPE professional learning to first understand what had been in place at the school where the punitive discipline approach ignored the complex histories of the children with whom they were working ( Costa, 2017 ). Instead, both leaders and teachers learnt the importance of support and avoiding actions that might trigger escalated power-laden responses in children ( Bath, 2008 ; Shonkoff et al., 2012 ; Carello and Butler, 2015 ).

A year 7 leader described the school’s prior response to behavioral issues which would impede a focus on instruction:

It’s gone from a punitive to a restorative kind of practice…we used to have detentions and all that type of stuff and that never worked, ever. Because it just, it wasn’t a timely reaction to what was going on and it wasn’t a meaningful reaction to what was going on. I used to be on the detention duty a lot and there’d be kids from all different year levels and they’re like, “Why am I here?”

I’d check the learning management system and have to say, “You’re here because you were being disrespectful,” and, their response was often, “I wasn’t doing that, and when was it?” Last week. They’re like, “Last week, why am I here now?” Because the detentions would carry over.

A student in year 12 described the behavior she used to see and the punitive responses that teachers used which completely distracted from her learning:

Just really, really bad behavior. Kids always getting sent out, learn nothing. They’d never come back or they’d get – we used to do like red slips, and you’d get sent out of class with that but then they’d just walk away…Something that just never worked with students.

This change in discipline policy required a wholesale shift toward a proactive mindset for leaders and teachers in this school. A teacher described the changes she has seen:

I’ve seen a change in this staff as well, the way they interact with students and the way that they communicate with them. I think they probably de-escalate them more than they heighten them, which is a big – from when I started. I think that some of the things that teachers said before were heightening students, and I don’t think they realized it. I did at the start too. I didn’t realize how to communicate with them.

I wasn’t enquiring with students, it was more that I would say to them, “Can you sit down?” Rather than, “Hey, what’s going on? Why are you standing up today?” Instead of, I would always – when I first started, I’d sort of jump to the – just telling them what to do rather than asking them what’s going on with them. A lot of the time they have a reason.

At the whole school level, school leaders developed a process that assisted them to support teachers and students in the process of being ready to learn. If a student is not ready to learn they may enact one of their Ready to Learn strategies (for example, walking outside the classroom for 5 min). Teachers webbex school leadership to notify if a student is leaving the classroom. All leaders are rostered on at different times to be in the corridors checking in (with non-confrontational approaches) with the students who are using their Ready to Learn Plans to take time out of the classroom. All leaders, teachers and school staff have been trained in TIPE approaches to be non-confrontational and walk side by side with students and at all times be focused on assisting students to understand their emotions and then move when ready back to learning in the classroom.

The youth worker described how he perceives the changes in the student management at the school:

I think the biggest contributors to changes in the school so far, what I’ve seen, is the trauma-informed positive education stuff. The structures that are in place for support when things happen, make a huge difference. They can just rely on that. The follow-up, the immediate follow-up, the follow-up afterward, if something would happen, Previous to that we didn’t have any of that. It was probably more punitive, rather than understanding as well.

The non-punitive response to behavior management was then enacted in the classroom by teachers, with the support of leaders, using TIPE strategies. The trauma-informed instructional strategies included all-staff agreements to enact: consistent transition and entry routines; Ready to Learn Plans in which students self-selected de-escalation and self-regulation strategies agreed upon with the teacher for use inside and just outside the classroom; brain breaks and mindfulness to renew focus on learning; deliberately building stamina for learning by visually charting and celebrating increasing minutes on task each day; and identification of micro moments of off task behavior as an early point of behavioral intervention (instead of waiting for a “bigger escalation” to occur which the teachers were doing before their trauma-informed professional learning).

The school leaders commented that in the past, escalated and disorganized student transitions between classes and activities were having a negative impact on instructional time in the classroom. Leaders commented that teachers were taking up to 20 min of instructional time getting their students settled after recess and other teachers were feeling let down by inconsistent transition routines between the prior teacher to the next teacher.

As discussed with the school leaders, teachers and staff at the TIPE professional learning, crisp, clear and consistent transitions that co-regulate students quickly and maximize learning were critical to both trauma-informed practice and learning more generally ( Robinson and Gray, 2019 ). At the core is the premise that leaders must see student and teacher time as a valuable resource to strategically manage to maximize learning ( Robinson and Gray, 2019 ). Leaders then supported a change to transition routines across the school. As one teacher commented:

The entry routines have been really good this year. A lot of the staff are doing them every single time. They’re waiting at the door, waiting for everyone to line up and then they’re greeting each student as they come in. I think that’s really good because you walk down the hallway and the kids are calm going into class.

As students entered the class, teachers did a quick emotional check in to see how the students were feeling about school. Two students explained how this worked in their classes. One explained the strategy.

Our maths and English teacher asks between ‘one-to-five’ how do we feel and how has the day gone so far? One is not even good, you don’t want to be at school but you’re at school, five is being you’re great, you’re at school, you want to learn and everything and they ask us what number are we? So if we say 2.5 they go, okay, you’re still at school but you’re in between. Then we prompt the students to use a strategy from their plan to boost to the next number if that will help for learning.

The other student explained why the teachers were doing the strategy.

It’s so the teachers can see who is stressed, who doesn’t want to be at school but they’re still at school. So, there’s something wrong in between somewhere so they can help that student out. We have to focus on strategies that build self-regulation.

Another strategy that teachers used to maximize instructional time for all students was the Ready to Learn Plan. These are a pre-agreed upon plan between student and teacher which empowered the student to enact a de-escalation or self-regulation strategy before returning to the learning task. A student explained what happens:

They’re just like, show us on your hands how you’re feeling today, from one to five. If people are one or two, the teachers go up to them and ask them what’s wrong and if they want to use their Ready to Learn Plan.

A school leader described the importance of Ready to Learn Plans to their classroom management strategy:

It’s really important at this school that kids are not in the classroom if they’re not able and ready to be doing what’s happening in there. We can’t expect them to self-regulate by themselves in the classroom without support.

A student described how Ready to Learn Plans empowered him manage his own behavior proactively:

If I’m feeling like aggravated or just really unsettled, I’ll use my Ready to Learn Plan and go get a drink. Just have a little walk outside.

This was reinforced by another student who commented:

Students that suffer from bad behavior, they’re just not having a good day, the Ready to Learn Plan is so good because it gives that student a second chance, which I think is really good.

One of the teachers described some of the benefits of the Ready to Learn Plan :

It’s a more settled environment and the students also have a feeling that they’re being listened to. It gives them an opportunity to have a voice, but also to reflect on their own thinking and behaviors and are they focused and ready to come into class.

Once the class was in progress there were strategies that teachers used throughout the lesson to maintain focus on effective instructional delivery. The instructional strategies that teachers and students consistently reported were: mindfulness; “brain breaks” (giving the whole class an opportunity to pause, breathe, anchor themselves with a prompt and return to learning); strategies to build stamina for learning and identification of early micro moments of off task behavior.

The strategies place a priority focus on increasing opportunities for students to focus on the academic work. While they appear to be strategies for student wellbeing, they are also strategies to improve learning with an alignment of both wellbeing and instructional strategies to assist implementation ( Overstreet and Chafouleas, 2016 ). Students have an opportunity to practice mindfulness, in addition to brain breaks which provide opportunities to move their bodies, take a breath, and build stamina for learning. Brain breaks were mentioned by teachers as something they could easily add to their classroom routines:

The brain breaks I feel, like in the teams that I was in last year and I’m in this year, I think that they came in quickly and it’s one of those things that it’s an easy implementation and the kids were responding well. I can’t imagine teaching without break breaks anymore. How on earth do you make them concentrate that long? No wonder we had so much trouble.

Students were consistently prompted by their teachers to consider what strategies were working well for them. A student commented on how they preferred brain breaks to mindfulness:

I like the brain breaks because it’s like for 5 min then we’re back doing work. So, I can sit still or do other things in brain break.

Mindfulness goes a bit too long. Some of the kids didn’t want to do it because they couldn’t sit still. I have to be doing something more physical.

Concurring with the findings of Robinson and Gray (2019) , leaders commented that teachers having proactive strategies to build on-task abilities “1-min at a time” for students who are quick to give up and avoid the task, is a critical component for improving student learning capabilities.

One leader described the work on stamina particularly in reading.

There were strategies where we had visually tracked their on-task learning with ‘stamina charts’ in classrooms where kids were doing independent reading for just 2 min because that’s all they could handle, now they’re doing it for 20 min which is all we need in the hour lesson to give them opportunity to increase reading success.

Finally, the TIPE strategy that teachers regularly mentioned was identification of “micro moments of off task behavior.” This strategy staff to move toward an early-intervention mindset with a focus on instructional time. Prior to their TIPE professional learning, teachers were not attuned to these micro moments of student escalation or off-task disengagement (hoping the adverse behavior would go away if ignored). The shift in early identification across the school sharpened the teachers’ collective ability to quickly identify the point of successful intervention and support with students struggling to de-escalate. One of the teachers described the importance of understanding micro moments but also the mental work that that level of awareness takes:

Seeing body language and how that’s going to impact when they come into the classroom and how you might spend a little extra time with them just at the door to give them a bit extra direction or a little bit extra conversation. A little bit extra that you’re keeping a watchful eye but knowing that there’s trigger points for that student that you can go over and quietly talk to them as opposed to remind them out loud of something.

So, you’re watching for those moments and changing what you do for that student. That, I think that’s a huge impact. I’m not going to lie to you, it’s tough though, because you’re constantly looking for these moments and every single student needs to be in your mind and how they’re reacting and behaving to each other, to you, to the work, to the classroom setting.

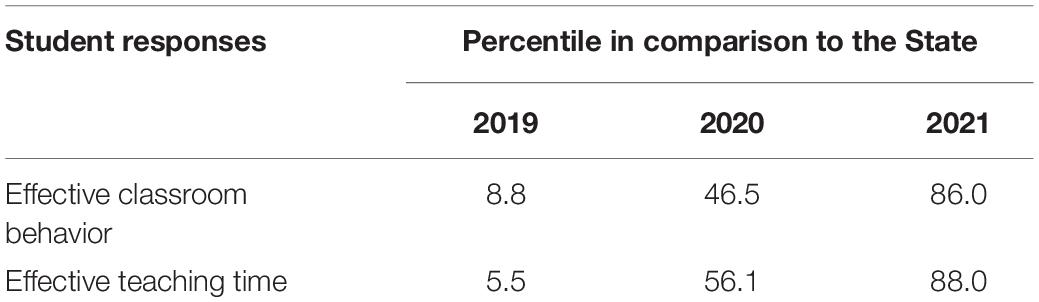

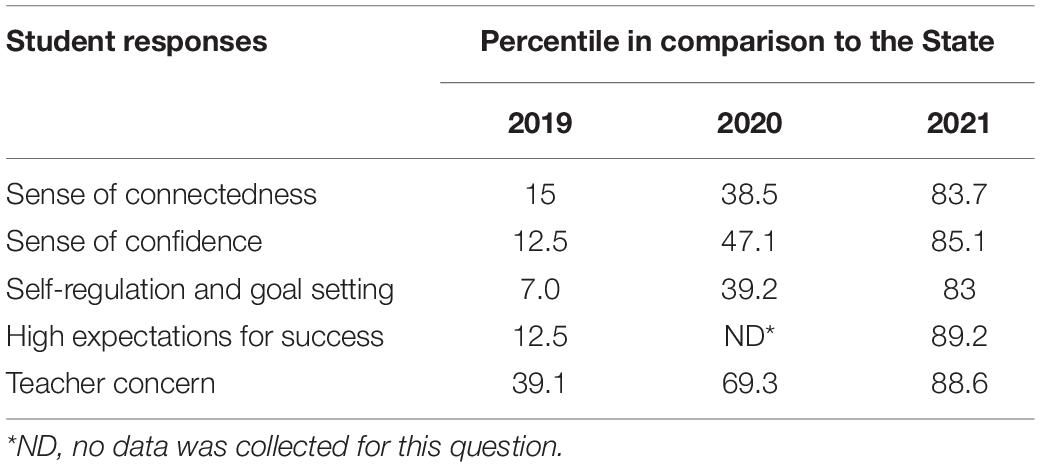

These strategies are similar to what other schools have put in place when implementing trauma-informed positive education (see Stokes and Turnbull, 2016 ; Stokes et al., 2019 ; Stokes and Aaltonen, 2021 for further examples of this work in schools). Developing the whole of school non-punitive behavior management response has taken the implementation of TIPE to a whole school level that is relevant for this school context. These changes to the school and classroom environment were reflected in the student responses in the AtoSS to their understanding of the effective use of class time (see Table 3 ).

Table 3. Attitudes to school survey – effective teaching practices for learning.

Following the implementation of the TIPE strategies, there have been positive outcomes for students at the school. These have included: the creation of an orderly environment for learning and an increase in positive student attitudes to school.

The Creation of an Orderly Environment for Learning

The creation of an orderly and safe environment for learning, underpins the opportunity for educational improvement in a school and must be included in a teacher’s instructional approach ( Robinson, 2011 ; Sebastian and Allensworth, 2012 ). Leadership in this area is important so that students can experience increased academic and wellbeing outcomes ( Marzano et al., 2005 ). Practices include clear and consistent discipline codes, high expectations for social behavior and a caring environment ( Robinson, 2011 ).

One of the leaders described what the school had been like and the impact of that on both staff and students:

The staff not turning up to work was massive in the past. Oh, he’s away again today, or she’s away. It was pretty rough before I got here. Some kids had had three teachers, different teachers in the same class in one term, so there was a great lack of relationships, so last year was the start of building good relationships with kids across the school.

While a teacher commented on the behavior she found when she came to the school a couple of years ago:

It was chaotic. Kids would come and go. They would be happy to verbally abuse anyone that came within 30 cm of them, even if you just looked at them…I think a lot of teachers struggling to make it through the day. Now it’s quite calm in comparison.

The students described what school had been like for them and how it had changed.

It used to be very ‘you do the work and you listen to me.’ Now it’s – “the teachers work with us.”

The teachers are more like listening to students, sort of working with them and stuff like that. More cooperative.

The students described more positive relationships with teachers as TIPE has been implemented in their school. This support for students who may be trauma affected concurs with research conducted by Berger (2019) on the impact of trauma informed professional practice.

This change in the learning environment, including shifting teacher practice that is caring and supportive with clear and consistent non-punitive discipline responses has been reflected in the change in the last 3 years of data from both staff climate surveys and student attitude to school surveys (AtoSS). Table 4 reflects the impact that the training, implementation and leadership support of trauma-informed positive education has had for teachers in the classroom. In 2019, only 15% of teachers responded that the learning environment in the school was orderly and focused. This changed to 53% in 2020 as trauma-informed positive education was being implemented and 89% as it was consolidated in the school.

Table 4. School staff surveys – the learning environment.

These findings are further supported by the Student AtoSS of the classroom environment. As can be seen from the Table 3 student responses on effective use of class time moved from the bottom quartile to the top quartile in the state from 2019 to 2021. This was the same period of time that the trauma-informed positive education training was undertaken by all school personnel and staff began implementing the strategies. In 2019 only 5.5% of students felt there was effective teaching time in comparison to all students in the rest of the State. This changed to 56.1% in 2020 and 88% in 2021.

An Increase in Positive Student Attitudes to School

Within the current case study, there were noticeable shifts in the ways students positively viewed their school, their teachers, and their peer-community. It is asserted that these changes were due to proactive changes to teachers’ instructional practice yielding changes in student perceptions of the school itself and thus, this cohort of students developed the ability to apply these wellbeing resources for readiness to learn. The change in student perceptions of the school was reflected in both the interview responses and from the AtoSS survey data over the past 3 years.

Comments from students included:

Yeah, it’s a lot better place to be. Like it used to be very – quite violent in a way. Like, mentally straining here because yeah, the teachers just wouldn’t listen to you.

The teachers that we have now are just all-round nicer people. Genuine. They’re not just doing it because it’s their job. They genuinely want to see us succeed.

These comments reflect the change in the way students and teachers interact and the corresponding change in student behavior and care shown by teachers toward the students.

The AtoSS survey data in Table 5 show the change of the last 3 years as TIPE has been implemented in the school. Student connectedness to school has moved from the bottom quartile compared to other students in the state to the top quartile, as has self-confidence, self-regulation (a particular focus of trauma-informed positive education), and high expectations for success. Students perceiving teacher were concerned about them was higher in 2019 at 39% than many other measures but this as well has moved to the top quartile (88.6%) in 2021. As Bryk (2010) notes students feeling that most teachers care about them is a measure of their engagement with school.

Table 5. Attitudes to school survey – social engagement and expectations.

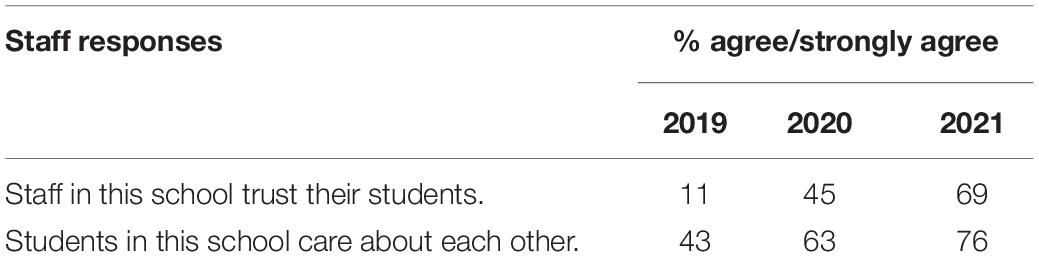

The School Staff survey in Table 6 further supports these changes in positive student attitudes to school with 69% of staff trusting their students in 2021 compared to 11% in 2019. In 2019, 43% of staff felt that students cared about each other, and this has risen to 76% in 2021.

Table 6. School staff surveys – staff trust in students.

Fredrickson and Joiner (2002) have shown that when primed with positive emotion and the opportunity to increase positive outlook, young people increase the likelihood of developing psychological resources for improved coping with daily adversities. Reciprocally, they also showed that increased capabilities in coping skills predicted both increases in experiencing positive emotions over time and the ability to employ social resources (e.g., connecting with one’s peers in healthy ways). When students are given opportunities to nurture psychological resources for their own wellbeing such as healthy coping skills, management of their own resilient self-talk strategies, and identifying their own strengths, they increase capacity to achieve their own goals for learning ( Seligman et al., 2009 ).

A case study approach has been used to explore a school that has implemented trauma-informed practices as an instructional approach over the last two and a half years. The aim of this approach has been to show the ways in which trauma-informed education can be fully integrated for learning and wellbeing.

For leaders at this school, the explicit development and implementation of a TIPE approach, designed for the context of the school, brought about change. Underpinning this was the TIPE professional learning using an AIPAR cycle that provided opportunities for leaders working with teachers and educational support staff to understand issues and needs and then co-create responses to those needs. With the support of TIPE professional learning, the school leadership team were able to harness multiple levers (such as the development of a non-punitive discipline response) toward shifting staff mindsets from reactive to proactive. In addition, the consistent whole school use of TIPE strategies assisted them to proactively support the creation of classroom environments to enable students to be ready to learn.

The school has undertaken a process to implement strengths-based, positive education strategies. At this stage of the research, many of the strategies were located in the Body, Relationship and Stamina domains. Further work in the school will focus on the Engagement and Character domains as it is critical that teachers and all school staff remember that students made vulnerable due to trauma and adverse childhood experiences have inherent character strengths within them. These students require daily reminders of the inherent value they contribute to the school and what is right with them on their journey of both healing and growth.

This study’s mixed-method case study design drew together relevant data on the school’s trauma-informed instructional approach including trauma-informed education practices, students’ attitudes to school, leading instruction and the impact of the TIPE professional learning. The results offer promise to future researchers and education leaders seeking a holistic way to support school transformation journeys with underpinning evidence; and furthers the call to focus on the implementation and sustainability of trauma-informed education strategies.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Melbourne, Human Ethics Committee HASS 1. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants or their legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

HS constructed the research framework, conducted the research in the schools then developed the literature, collected and analyzed the data through coding, developed the themes and then wrote the findings and discussion according to the themes.

Berry Street (No. 300781) and Brotherhood of St. Lawrence (No. 302406) commissioned the research from the University of Melbourne in the three schools on the programs they were running in the three schools.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- ^ https://www.education.vic.gov.au/PAL/data-collection-school-staff-survey-framework.pdf

- ^ https://www.education.vic.gov.au/PAL/attitudes-to-school-survey-framework.pdf

Alvord, M. K., and Grados, J. J. (2005). Enhancing resilience in children: a proactive approach. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 36, 238–245. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.36.3.238

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci . 256, 174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020). 2016 Census QuickStats. Available online at: quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC20942 (accessed May 15, 2020).

Google Scholar

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA] (2020). My School. Available online at: https://www.myschool.edu.au (accessed March 25, 2022).

Bath, H. (2008). The three pillars of trauma-informed care. Reclaim. Child. Youth 17, 17–21

Baxter, P., and Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 13, 544–559:

Berger, E. (2019). Multi-tiered approaches to trauma-informed care in schools: a systematic review. Sch. Ment. Health 11, 650–664. doi: 10.1007/s12310-019-09326-0

Bishop, A., Berryman, M., Wearmouth, J., and Peter, M. (2012b). Developing an effective education reform model for indigenous and other minoritized students. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 23, 49–70. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2011.647921

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Wearmouth, J., Peter, M., and Clapham, S. (2012a). Professional development, changes in teacher practice and improvements in Indigenous students’ educational performance: a case study from New Zealand. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.02.002

Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., et al. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. J. Adolesc. Health 40, 357.e9–357.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013

Brennan, N., Beames, J., Kos, A., Reily, N., Connell, C., Hall, S., et al. (2021). Psychological Distress in Young People in Australia, Fifth Biennial Youth Mental Health Report: 2012-2020. Sydney: Mission Australia

Brunzell, T. (2017). “Healing and growth in the classroom: a positive education for trauma-affected and disengaging students,” in Future Directions in Well-being: Education, Organizational and Policy eds M. A. White, G. R. Slemp and A. S. Murray (Cham: Springer), 21–25. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-56889-8_4

Brunzell, T. (2019). Meaningful Work for Teachers Within a Trauma- Informed Positive Education Model. Unpublished thesis. Parkville VIC: University of Melbourne.

Brunzell, T. (2021). “Trauma-aware practice and positive education,” in The Palgrave Handbook on Positive Education , eds M. L. Kern and M. Wehmeyer (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 205–223. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_8

Brunzell, T., and Norrish, J. (2021). Creating Trauma- Informed Strengths-Based Classrooms. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Brunzell, T., Norrish, J., Ralston, S., Abbott, L., Witter, M., Joyce, T., and Larkin, J. (2015). Berry Street Education Model: Curriculum and Classroom Strategies . Melbourne, VIC: Berry Street Victoria.

Bryk, A. (2010). Organizing Schools for Improvement. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.1177/003172171009100705

Carello, J., and Butler, L. D. (2015). Practicing what we teach: trauma-informed educational practice. J. Teach. Soc. Work 35, 262–278. doi: 10.1080/08841233.2015.1030059

Catalano, R. F., Haggerty, K. P., Oesterle, S., Fleming, C. B., and Hawkins, J. D. (2004). The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: findings from the social development research group. J. Sch. Health 74, 252–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x

Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., and Liautaud, J. (2005). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatr. Ann. 35, 390–398. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: a meta- analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 113–143. doi: 10.3102/003465430298563

Costa, D. A. (2017). Transforming Traumatised Children within NSW Department of Education Schools: one School Counsellor’s Model for Practise – REWIRE. Child. Aust . 42, 113–126. doi: 10.1017/cha.2017.14

Day, A. G., Somers, C. L., Baroni, B. A., West, S. D., Sanders, L., and Peterson, C. D. (2015). Evaluation of a trauma-informed school intervention with girls in a residential facility school: student perceptions of school environment. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 24, 1086–1105. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.1079279

de Arellano, M. A., Ko, S. J., Danielson, C. K., and Sprague, C. M. (2008). Trauma-Informed Interventions: Clinical and Research Evidence And Culture-Specific Information Project . Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Denscombe, M. (2003). The Good Research Guide , England. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Dinham, S. (2008). How to Get Your School Moving and Improving: An Evidence-Based Approach . Melbourne. VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research Press.

Dinham, S. (2016). Leading Learning and Teaching. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research Press.

Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J., and Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2, 222–235. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4

Downey, L. (2012). Calmer Classrooms: A Guide to Working with Traumatised Children. Melbourne, VIC: Child Safety Commissioner.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev . 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Fredrickson, B. L., and Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychol. Sci. 13, 172–175. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00431

Hemphill, S. A., Plenty, S. M., Herrenkohl, T. I., Toumbourou, J. W., and Catalano, R. F. (2014). Student and school factors associated with school suspension: a multilevel analysis of students in Victoria, Australia and Washington State, United States. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 36, 187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.11.022

Howard, J. A. (2019). A systemic framework for trauma-informed schooling: complex but necessary! J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 28, 545–565. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1479323

Knapp, M. S. (2003). Chapter 4: professional development as a policy pathway. Rev. Res. Educ. 27, 109–157. doi: 10.3102/0091732X027001109

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2019). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Leadersh. Manage 40, 5–22. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

Line Seligman, M. E. P., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Ludema, J. D., and Fry, R. E. (2008). “The practice of appreciative inquiry,” in Handbook of Action Research , 2nd Edn, eds P. Reason and H. Bradbury (London: Sage), 280–296. doi: 10.4135/9781848607934.n27

Ludema, J. D., Cooperrider, D. L., and Barrett, F. J. (2006). “Appreciative inquiry: the power of the unconditional positive question,” in Handbook of Action Research , eds P. Reason and H. Bradbury (London: Sage), 155–165.

Marzano, R., Waters, T., and McNulty, B. (2005). Some Theories and Theorists on Leadership.School Leadership that Works: From Research to Results , ASCD. Available online at: https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=UfNQBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=school+leadership+that+works+marzano&ots=qhs1Mzi6r5&sig=7AUgdwHwJmj_PhlUVePVd3MctmI#v=onepage&q=school%20leadership%20that%20works%20marzano&f=false (accessed March 25, 2022).

Mashford-Scott, A., Church, A., and Tayler, C. (2012). Seeking children’s perspectives on their wellbeing in early childhood settings. Int. J. Early Child . 44, 231–247. doi: 10.1007/s13158-012-0069-7

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994 11). Qualitative Data Analysis , 2nd Edn. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Overstreet, S., and Chafouleas, S. M (2016). Trauma-informed schools: introduction to the special issue. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9184-1

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. J. Loss Trauma 14, 240–255. doi: 10.1080/15325020903004350

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification . Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Porche, M. V., Costello, D. M., and Rosen-Reynoso, M. (2016). Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 44–60. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9174-3

Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., et al. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 278, 823–832.: doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823

Robinson, V., and Gray, E. (2019). What difference does school leadership make to student outcomes? J. R. Soc. N. Z . 49, 171–187. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2019.1582075

Robinson, V. (2011). Student-Centered Leadership , Vol. 15. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Robinson, V. M., Lloyd, C. A., and Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: an analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educ. Adm. Q . 44, 635–674. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08321509

Sebastian, J., and Allensworth, E. (2012). The influence of principal leadership on classroom instruction and student learning: a study of mediated pathways to learning. Educ. Adm. Q . 48, 626–663. doi: 10.1177/0013161X11436273

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., and Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Rev. Educ. 35, 293–311. doi: 10.1080/03054980902934563

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., et al. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 129, e232–e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Stake, R. E. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research . London : Sage

Stokes, H., and Brunzell, T. (2019). Professional learning in trauma informed positive education: moving school communities from trauma affected to trauma aware. Sch. Leadersh. Rev . 14:6.:

Stokes, H., and Turnbull, M. (2016). Evaluation of the Berry Street Education Model: Trauma Informed Positive Education Enacted in Mainstream Schools. Melbourne, VIC: University of Melbourne.

Stokes, H., Turnbull, M., Forster, R., and Farrelly, A. (2019). Young people’s voices, young people’s lives: A Berry Street Edcuational Model (BSEM) project. Melbourne, VIC: University of Melbourne.

Stokes, H, and Aaltonen, S (2021). Time–space paths and the experiences of vulnerable young people in alternative educational settings, Int. J. Inclusive Educ. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1994663

Sullivan, A. M., Johnson, B., Owens, L., and Conway, R. (2014). Punish them or engage them? Teachers’ views of unproductive student behaviours in the classroom. Austral. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 43–56. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2014v39n6.6

Thompson, P., Kriewaldt, J., and Redman, C. (2020). Elaborating a model for teacher professional learning to sustain improvement in teaching practice. Austral. J. Teach. Educ 45, 81–103. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2020v45n2.5

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Developmental trauma disorder: toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatr. Ann . 35, 401–408. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-06

Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training (2021). School Staff Survey. Melbourne, VIC: Victorian Department of Education and Training.

Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training [VIC DET] (2022b). Framework for Improving Student Outcomes (FISO 2.0). Melbourne, VIC: Victorian Department of Education and Training.

Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training [VIC DET] (2022a). Attitudes to School Survey Framework. Melbourne, VIC: Victorian Department of Education and Training.

Vinson, T., Rawsthorne, M., Beavis, A., and Ericson, M. (2015). Dropping off the Edge 2015. Persistent Communal Disadvantage in Australia. Jesuit Social Services/Catholic Social Services Australia. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299389688_Dropping_off_the_edge_Persistent_communal_disadvantage_in_Australia/link/56f34ea308ae38d7109a5818/download (accessed March 25, 2022).

Wahlstrom, K., and Seashore-Louis, K. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: the roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educ. Adm. Q. 44, 458–495. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08321502

Waters, L. (2011). A review of school-based positive psychology interventions. Austral. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 28, 75–90. doi: 10.1375/aedp.28.2.75

West, S. D., Day, A. G., Somers, C. L., and Baroni, B. A. (2014). Student perspectives on how trauma experiences manifest in the classroom: engaging court-involved youth in the development of a trauma-informed teaching curriculum. Child. Youth Serv. Rev . 38, 58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.01.013

Wiliam, D. (2014). The Formative Evaluation of Teaching Performance. Melbourne, VIC: Centre for Strategic Education.

Wilkins, R., Vera-Toscano, E., Botha, F., and Dahmann, S. (2021). The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 19 . (Parkville VIC: University of Melbourne), 110–117.

Wolpow, R., Johnson, M. M., Hertel, R., and Kincaid, S. O. (2009). The Heart of Learning and Teaching: Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success. Olympia, WA: Washington State office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Compassionate Schools.

Keywords : school leadership, instructional practice, wellbeing, professional learning (PL), trauma affected

Citation: Stokes H (2022) Leading Trauma-Informed Education Practice as an Instructional Model for Teaching and Learning. Front. Educ. 7:911328. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.911328

Received: 02 April 2022; Accepted: 08 June 2022; Published: 24 June 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Stokes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helen Stokes, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Submit your manuscript

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Effectiveness of trauma-informed, school-based interventions for children with a history of trauma or adverse experiences: an umbrella review protocol

McGraw, Sarah 1,2 ; Palokas, Michelle 1,2 ; Christian, Robin 1,2

1 School of Nursing, The University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA

2 Mississippi Centre for Evidence Based Practice: A JBI Centre of Excellence, The University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA

Correspondence: Sarah McGraw, [email protected]

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Objective:

The objective of this review is to synthesize evidence regarding the effectiveness of trauma-informed, school-based interventions for children with a history of trauma or adverse experiences as they pertain to academic performance and health outcomes, including behavior, mental health, and socio-emotional functioning.

Introduction:

Children and adolescents who face prolonged adverse experiences or trauma have a predisposition toward emotional, behavioral, mental, and physical health problems. Few children or adolescents who endure the repercussions of constant stress and hardships, or survivors of one or more types of trauma, receive the appropriate screening and diagnosis; therefore, they do not receive tailored care or interventions.

Inclusion criteria:

This review will include research syntheses pertaining to school-based, trauma-informed interventions for children and adolescents between the ages of 4 and 18 years with a history of adverse experiences or trauma. Comparisons will be made across all known school-based, trauma-informed interventions. This review will consider systematic reviews that include the following outcomes: mental health, behavior, academic performance, and/or socio-emotional functioning.

Methods:

The search strategy will aim to locate both published and unpublished systematic reviews. An initial limited search of MEDLINE (PubMed) and CINAHL (EBSCO) will identify articles on the topic. The search strategy will be adapted for each included information source. Articles published in English will be considered for inclusion and no date limits will apply. Two independent reviewers will critically appraise eligible studies. Extracted data will be tabulated and presented along with a narrative summary.

Introduction

The Center for Youth Wellness defines adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as “stressful or traumatic events that children experience before the age of 18, such as violence at home, neglect, abuse, or having a parent with mental illness or substance dependence.” 1 (para.2) Generally well-understood and accepted throughout research literature, ACEs have detrimental effects on the overall well-being of an individual, both as a child and later in life as an adult. 1-9 Nearly half of all children in the United States are affected by ACEs, 1 and roughly one in four or five children and adolescents report mental health issues following ACEs. 2